Abstract

A reliable estimate of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) mobilization response to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) may identify donors at risk for poor mobilization and help optimize transplantation approaches. We studied 639 allogeneic PBSC collections performed in 412 white, 75 black, 116 Hispanic, and 36 Asian/Pacific adult donors who were prescribed G-CSF dosed at either 10 or 16 μg/kg per day for 5 days followed by large-volume leukapheresis (LVL). Additional LVL (mean, 11 L) to collect lymphocytes for donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) and other therapies was performed before G-CSF administration in 299 of these donors. Day 5 preapheresis blood CD34+ cell counts after mobilization were significantly lower in whites compared with blacks, Hispanics, and Asian/Pacific donors (79 vs 104, 94, and 101 cells/μL, P < .001). In addition, donors who underwent lymphapheresis before mobilization had higher CD34+ cell counts than donors who did not (94 vs 79 cells/μL, P < .001). In multivariate analysis, higher post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts were most strongly associated with the total amount of G-CSF received, followed by the pre–G-CSF platelet count, pre–G-CSF mononuclear count, and performance of prior LVL for DLI collection. Age, white ethnicity, and female gender were associated with significantly lower post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts.

Introduction

Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) are increasingly used in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation because of their relative ease of collection and rapid hematopoietic reconstitution.1–3 In this setting, the donor's mobilization response to granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and subsequent CD34+ apheresis yields may exert a significant effect on transplant outcomes and donation experiences.4 A small percentage of healthy donors have a poor mobilization response to G-CSF, resulting in the need for additional apheresis collections or repeat mobilization cycles to collect an adequate PBSC dose for engraftment and immune reconstitution.5 Furthermore, higher CD34+ cell doses may be associated with improved transplant outcomes in some settings,6,7 and transplant approaches involving selective depletion or manipulation of the graft may require additional or larger volume apheresis procedures to compensate for losses incurred during cell processing. Conversely, apheresis procedures in donors with very high CD34+ mobilization responses,8 and those producing very large PBSC yields may be associated with adverse recipient outcomes, such as acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).9 Therefore, a reliable estimate of a donor's CD34+ cell mobilization response to G-CSF and subsequent PBSC yield could be of value in planning transplantation approaches.

Prior studies have yielded conflicting data regarding the effect of various donor demographic, laboratory, and other factors on peak donor CD34+ mobilization responses and apheresis cell yields.10–13 In addition, the effect of donor race or ethnicity on PBSC mobilization has not been previously analyzed, and no data are available regarding the impact of peri-mobilization donor procedures such as the performance of unstimulated apheresis for collection of cells for donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs), and other cellular therapies. To evaluate these potential effects, we analyzed factors associated with PBSC mobilization and yield in a large, ethnically diverse population of healthy allogeneic adult donors.

Methods

Donors

Study subjects comprised 639 consecutive allogeneic donors who underwent PBSC collection by large-volume leukapheresis (LVL) after G-CSF mobilization between January 1999 and March 2006. All subjects were healthy sibling donors at least 18 years of age, who were undergoing their first PBSC mobilization and gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board–approved transplantation protocols. According to individual protocol design, 299 of these donors also underwent an unstimulated (non–G-CSF mobilized) lymphapheresis collection by LVL before initiation of G-CSF to collect cells for use in posttransplantation strategies designed to enhance transplant outcomes, including donor lymphocyte infusions,14 scheduled T-cell “add-backs,”6,15 Th2/Tc2 cell generation,16,17 and other ex vivo graft manipulation therapies. At each visit, donor demographic information, including age, sex, height, and weight, was collected. Ethnicity was self-categorized as white, black, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific and is reported throughout this study as ethnicity rather than race for consistency.

Mobilization and collection of PBSC

All donors received 5 days of G-CSF (filgrastim; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) with leukapheresis initiated on the morning of day 5, at least 2 hours after the last G-CSF dose.4 All data in this report for PBSC CD34+ apheresis yields were obtained from a single apheresis procedure per donor, performed on day 5. The G-CSF dose was prescribed as either 10 μg/kg per day given as a single subcutaneous injection or 8 μg/kg given twice daily (16 μg/kg per day); the actual dose administered was obtained in all cases from review of pharmacy and nursing records. LVL procedures were performed with use of a model CS-3000 Plus continuous-flow apheresis device (Fenwal Division, Baxter, Deerfield, IL) using prophylactic intravenous calcium and magnesium as previously described.18 Volume processed per procedure ranged from 15 to 25 L for PBSC collections (mean ± SD, 19 ± 4 L), depending on the preapheresis CD34+ cell count, and from 7 to 15 L (11 ± 2 L) for LVL conducted to collect lymphocytes for DLI. Apheresis procedures were well tolerated, with no serious adverse events reported.

Laboratory analyses

Complete blood counts were measured at baseline before G-CSF administration (pre–G-CSF), before and after PBSC collection after G-CSF mobilization (post–G-CSF and postapheresis, respectively), and before and after lymphapheresis for donors who underwent LVL for collection of cells for DLI (pre-DLI and post-DLI, respectively). The complete blood count was assayed using an electronic cell counter, and quantification of CD34+ cells before and after PBSC collection was performed by flow cytometry as previously described.19

Statistical analysis

Graphics and standard data analysis were performed with a spreadsheet application (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as BMI = (weight in kilograms)/(height (in meters)2). The percentage body fat was calculated as [(body weight − lean body weight)/body weight] × 100, where lean body weight = [(1.07 × body weight (kg)) − 148 × (body weight (kg)2/(100 × height (m)2)] for women and [(1.10 × body weight (kg)) − 128 × (body weight (kg)2/(100 × height (m)2)]. The total mononuclear cell count was calculated as the sum of total lymphocyte and total monocyte count reported on the white blood cell differential from the complete blood cell count. Actual administered values, which were within 10% of the prescribed dose, were used for comparisons of G-CSF dosed at 10 versus 16 μg/kg per day. Significance tests for comparisons between 2 groups were conducted with 2-tailed, nonpaired t tests. Values between more than 2 groups were compared using analysis of variance. Multivariate analyses were performed using stepwise forward logistic regression, based on parameters having significance in univariate analysis, using a commercial statistics program (StatView; Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). Proportions between 2 groups were compared using a 2-tailed Fisher exact test, and comparisons of proportions between multiple groups were made using χ2 analysis. Results are provided as the mean plus or minus SD, unless otherwise stated.

Results

Donor demographics, apheresis parameters, and CD34+ cell counts

Donor demographics, peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts after G-CSF mobilization (post–G-CSF), and CD34+ apheresis yields per liter processed are shown according to donor ethnicity in Table 1. Of the 639 subjects, 66% (n = 412) were white, 11% (n = 75) were black, 18% (n = 116) were Hispanic, and 5% (n = 36) were Asian/Pacific Islander. Compared with other groups, whites were older, whereas Asian/Pacific donors had lower body weight and lower BMI. The mean weight for the entire study population was 79 kg (± 18 kg). Asians had the lowest mean weight at 68 kg (± 16 kg), followed by Hispanics, 75 kg (± 17 kg), whites, 80 kg (± 19 kg) and blacks, 82 kg (± 16 kg). There was no difference in sex distribution; 51% of study subjects overall were male. As illustrated in Table 1, peripheral blood post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts and CD34+ apheresis yields were significantly lower in white donors than in the other ethnic groups.

Table 1.

Donor demographics, post–G-CSF peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts and CD34+ apheresis yields

| Characteristic | All | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 639 | 412 | 75 | 116 | 36 | |

| Male, % | 51 | 51 | 52 | 50 | 52 | NS |

| Age, y | 40 ± 13 | 43 ± 13 | 38 ± 10 | 35 ± 12 | 36 ± 12 | <.001 |

| Weight, kg | 79 ± 18 | 80 ± 19 | 82 ± 16 | 75 ± 17 | 68 ± 16 | <.001 |

| Height, cm | 170 ± 10 | 172 ± 10 | 172 ± 10 | 166 ± 10 | 166 ± 11 | <.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 28 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 25 ± 5 | <.001 |

| Peripheral blood CD34+ cell count, per μL | 86 ± 52 | 79 ± 49 | 104 ± 58 | 94 ± 49 | 101 ± 74 | <.001 |

| CD34+ yield, × 106 cells/L processed | 32 ± 20 | 31 ± 21 | 40 ± 27 | 33 ± 20 | 36 ± 25 | <.001 |

NS, not significant.

For ANOVA comparison among all groups.

Association of CD34+ cell counts with G-CSF dose, and demographic and laboratory variables

In the study group of 639 donors, 561 received an administered G-CSF dose that was within 10% of 10 μg/kg per day (10.1 ± 0.4; range, 9.0-11.0 μg/kg per day) and 27 received an administered G-CSF dose that was within 10% of 16 μg/kg per day (16.0 ± 0.4; range, 15.0-16.7 μg/kg per day), as listed in Table 2. The remaining 51 donors received a mean administered G-CSF dose outside of these ranges (mean 9.5 ± 1.7; range, 6.4-13.9 μg/kg per day).

Table 2.

Post–G-CSF peripheral blood CD 34+ cell counts and CD 34+ apheresis yields according to G-CSF dose (μg/kg) and ethnicity

| Administered G-CSF dose, μg/kg* | All donors | White | Black | Hispanic | Asian/Pacific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μg/kg | |||||

| N | 561 | 350 | 67 | 108 | 36 |

| Male, % | 51% | 51% | 50% | 50% | 52% |

| Weight, kg | 78 ± 17 | 79 ± 17 | 81 ± 16 | 76 ± 17 | 68 ± 16 |

| Total G-CSF received, μg/d | 788 ± 169 | 801 ± 169 | 815 ± 152 | 766 ± 169 | 688 ± 160 |

| CD34+ response | |||||

| Peripheral blood, per μL | 84 ± 51† | 77 ± 45 | 102 ± 59 | 93 ± 49 | 101 ± 74 |

| Yield, 106/L processed | 32 ± 20‡ | 30 ± 19 | 40 ± 26 | 33 ± 20 | 36 ± 24 |

| 16 μg/kg | |||||

| N | 27 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Male, % | 37% | 38% | 0% | 50% | — |

| Weight, kg | 78 ± 15 | 78 ± 16 | 82 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | — |

| Total G-CSF received, μg/d | 1247 ± 236 | 1253 ± 255 | 1335 ± 191 | 1170 ± 159 | — |

| CD34+ response | — | ||||

| Peripheral blood, per μL | 119 ± 49† | 114 ± 52 | 144 ± 26 | 130 ± 40 | — |

| Yield, 106/L processed | 39 ± 17‡ | 38 ± 18 | 46 ± 15 | 41 ± 17 | — |

—, not applicable.

Includes donors with actual G-CSF received within 10% of prescribed dose of 10 or 16 μg/kg per day.

P < .001, 16 versus 10 μg/kg per day G-CSF for peripheral blood CD34+ cell count.

P = .02, 16 versus 10 μg/kg per day G-CSF for CD34+ apheresis yields per L processed.

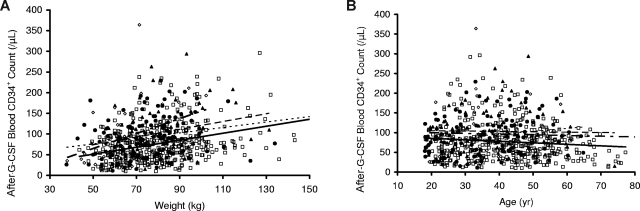

As shown in Figure 1, donors with greater weight had significantly higher post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts (Figure 1A), whereas donors who were older had lower CD34+ cell counts (Figure 1B). In both instances, CD34+ responses were lowest in white donors (Figure 1A,B). As shown in Figure 2A and Table 2, donors who received G-CSF at 16 μg/kg per day (8 μg/kg twice a day) had significantly higher CD34+ mobilization responses than those who received G-CSF at 10 μg/kg per day (P < .001). However, responses were similar when post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts were plotted against the total amount of G-CSF received per day rather than the dose per kilogram (Figure 2B), suggesting that the total amount of G-CSF received, rather than the dose per kilogram, exerted a larger effect on CD34+ mobilization in this study population.

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood CD34+ cell count after G-CSF administration (10 μg/kg per day) versus weight and age according to donor self-described ethnicity. Peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts after G-CSF administration were strongly associated with weight in all ethnic groups. When plotted against donor weight (A), CD34+ cell counts were highest in donors who were Asian/Pacific (◇, short alternating with long dashed line), followed by blacks (▲, dashed line), Hispanic (●, dotted line), and then whites (□, solid line). There was a modest, negative association of CD34+ cell counts when plotted vs donor age (B); the lowest values were observed in white donors and higher values in those who were black, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific.

Figure 2.

Associations of peripheral blood CD34+ cell count after G-CSF administration and weight according to G-CSF dose per kg donor weight and total amount of G-CSF received. Peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts plotted against donor weight (A) were significantly higher in donors who received G-CSF at 16 μg/kg per day given as 8 μg/kg per day twice a day (○, dashed line) than in donors who received 10 μg/kg per day (♦, solid line). In contrast, peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts after G-CSF administration plotted against the total dose of G-CSF received (B) were similar in donors who received G-CSF at either 16 μg/kg per day given as 8 μg/kg per day twice a day (○, dashed line) or 10 μg/kg per day (♦, solid line), suggesting that the total amount of G-CSF received exerts a larger impact on CD34+ mobilization than the dose of G-CSF administered per kilogram of donor weight.

Donors with higher platelet and total mononuclear cell count before administration of G-CSF (pre–G-CSF) also had significantly higher peripheral blood post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts, as shown in Figure 3A,B. The strongest response was observed in Asian/Pacific donors. The lowest values for CD34+ mobilization response were observed in whites, with intermediate responses in blacks and Hispanics.

Figure 3.

Associations of peripheral blood CD34+ cell count after G-CSF administration (10 μg/kg per day) according to baseline pre–G-CSF blood platelet count and total mononuclear cell count. Peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts after G-CSF were higher in donors with higher pre–G-CSF blood platelet counts (A) and total mononuclear cell counts (B). In panels A and B, the response was steepest in Asian/Pacific donors (◇, short alternating with long dashed trend line). Lower responses were observed in white donors (□, solid trend lines) with intermediate levels in blacks (▲, dashed trend line) and Hispanic (●, dotted trend line) donors.

Effect of prior lymphapheresis on CD34+ mobilization

In accord with individual protocol designs, 299 of the 639 donors in this study underwent an unstimulated lymphapheresis for collection of cells for subsequent DLI, before receiving G-CSF stimulation and PBSC collection. Comparison of prelymphapheresis and postlymphapheresis complete blood counts in these donors demonstrated that the procedure significantly lowered blood hemoglobin concentration, platelet and total white blood cell count, and lymphocyte counts (Table 3). As shown in Table 4, peripheral blood hemoglobin and platelet levels, but not absolute lymphocyte levels, remained low after subsequent G-CSF administration, both before and after PBSC collection (post–G-CSF and postapheresis), and were significantly lower in these 299 donors than in the other donors who did not undergo lymphapheresis. Interestingly, the donors who underwent a prior lymphocyte collection had significantly higher post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts than those who did not (mean 94 vs 79/μL, P < .001), an effect that was most marked in the 164 of 299 donors who underwent lymphapheresis within 2 days of beginning G-CSF mobilization (mean post–G-CSF CD34+ count, 98/μL, P = .005, Figure 4). Donors who underwent a prior lymphapheresis procedure also had higher CD34+ apheresis yields per liter processed (34 vs 30 × 106 CD34+ cells/L processed, P = .003; 36 × 106 CD34+ cells/L processed when lymphapheresis was performed within 2 days of beginning G-CSF, P = .02) than donors who did not undergo this procedure.

Table 3.

Hematologic parameters before and after donor lymphocyte collection by apheresis before PBSC mobilization in 299 allogeneic donors

| Platelets, ×109/L | Hemoglobin, g/L | White blood cells, ×109/L | Lymphocytes, ×109/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-DLI | 259 ± 55 | 137 ± 15.3 | 6.36 ± 1.6 | 1.93 ± 0.6 |

| Post-DLI | 178 ± 50 | 129 ± 17 | 5.72 ± 1.7 | 1.51 ± 0.4 |

| P | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 |

Table 4.

Parameters at the time of PBSC collection after G-CSF mobilization in donors who did, compared with those who did not, undergo a prior lymphapheresis procedure

| Prior donor lymphocyte collection | Post–G-CSF peripheral blood CD34+, per μL | CD34+ yield, 106/L processed | Hemoglobin, g/L | Platelets, ×109/L | Lymphocytes, ×109/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before PBSC collection | |||||

| No | 79 ± 46 | — | 135 ± 13 | 235 ± 53 | 3.91 |

| Yes | 94 ± 59 | — | 132 ± 16 | 214 ± 52 | 3.78 |

| P | <.001 | — | .02 | <.001 | .4 |

| After PBSC collection | |||||

| No | — | 30 ± 21 | 127 ± 14 | 160 ± 42 | 2.21 ± 0.6 |

| Yes | — | 34 ± 25 | 122 ± 16 | 141 ± 47 | 2.11 ± 0.6 |

| P | — | .003 | .002 | .002 | .09 |

— indicates not applicable.

Figure 4.

Peripheral blood CD34+ cell count after administration of G-CSF versus body weight. Peripheral blood CD34+ cell counts after G-CSF administration at 10 μg/kg per day were higher in donors who underwent (▲, solid trend line) collection of donor lymphocytes by large-volume leukapheresis before G-CSF administration compared with those who did not (◇, dashed trend line) undergo lymphocyte collection before the initiation of G-CSF administration. Data above are for those donors who underwent lymphocyte collection within 2 days of starting G-CSF.

Univariate and multivariate stepwise regression analysis of factors affecting CD34+ mobilization

In univariate logistic regression analysis, the strongest association with higher post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts was observed with total G-CSF dose administered (P < .001), followed by weight (P < .001), pre–G-CSF donor platelet count (P < .001), pre–G-CSF donor mononuclear cell count (P < .001), prior lymphapheresis for DLI collection (P = .008), and G-CSF dose per kg (P = .006). In contrast, white ethnicity (P < .001) and female sex (P = .006) were associated with lower CD34+ cell counts in univariate analysis, whereas age (P = .06) exhibited a trend toward association with lower CD34+ cell counts. In stepwise regression after adjustment for total G-CSF dose received, higher post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts remained significantly associated with the pre–G-CSF platelet count (P < .001), pre–G-CSF mononuclear cell count (P < .001), and prior lymphapheresis for DLI collection (P = .02), and were negatively associated with white ethnicity (P < .001) and age (P < .004); after this adjustment (total amount of G-CSF received), the associations of CD34+ cell counts with sex (P = .45), weight (P = .598), and G-CSF dose per kilogram (P = .85) no longer retained significance. Interestingly, donor height, which was not significantly associated with CD34+ cell counts in univariate analysis (P = .54), exhibited a strong negative association with this parameter (P = .001) after adjustment for the total amount of G-CSF received.

In the final multivariate stepwise regression, higher post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts were positively associated with total G-CSF dose (P < .001), pre–G-CSF platelet count (P < .001), pre–G-CSF absolute mononuclear cell count (P = .005), and prior lymphapheresis for DLI collection (P = .007), and were negatively associated with height (P < .001), female gender (P < .001), white ethnicity (P = .004), and age (P = .003); no significant association was present with weight (P = .3) or G-CSF dose per kilogram (P = .6).

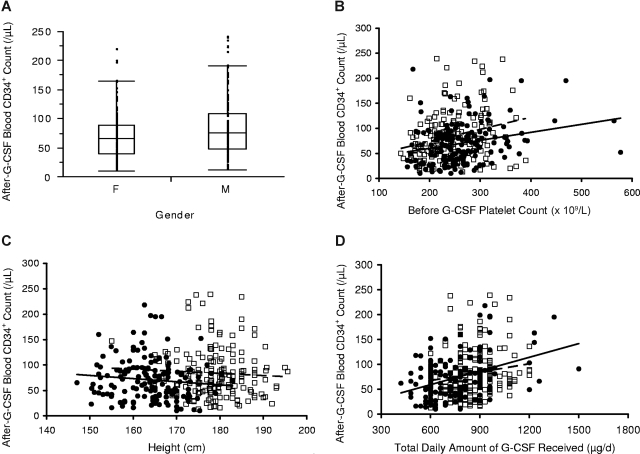

In this study, female donors overall had lower post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts than men (79 vs 93 cells/μL, P < .001), and female sex was significantly associated with lower post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts in univariate analysis. The overall impact of sex on post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts was complicated by the fact that female donors weighed less than male donors (71 vs 86 kg, respectively, P < .001), received lower total amounts of G-CSF (740 vs 877 μg, respectively, P < .001), were shorter (163 vs 177 cm, respectively, P < .001), and had higher baseline pre–G-CSF platelet counts (266 vs 246 × 103/μL, respectively). Thus, when post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts were adjusted for the total amount of G-CSF received, responses in women were overall similar to men, as illustrated in Figure 5 for white donors.

Figure 5.

Peripheral blood peak CD34+ cell count in male (□, dashed trend line) and female (●, solid trend line) white donors after 10 μg/kg per day G-CSF according to pre G-CSF platelet count, height, and total amount of G-CSF received. As shown in panel A, white females (F) had lower mean post–G-CSF CD34+ cell counts than males (M; mean, 69 vs 83/μL, P = .007; median, 66 vs 76/μL). The horizontal line represents the median, the box the 25th percentile, and the whiskers the 75th percentile. Female donors also had lower CD34+ responses than male donors when plotted against the pre–G-CSF platelet count (B) and height (C); these associations were mitigated by the fact that, on average, women had higher pre–G-CSF platelet counts and lower height than men. When plotted against total G-CSF received, CD34+ responses were similar in men and women (D).

Demographic and laboratory parameters in donors with a poor mobilization response

Table 5 lists clinical and laboratory data for donors who experienced a poor mobilization response to G-CSF, defined as either a post–G-CSF CD34+ cell count less than 20 (n = 29) or less than 30 (n = 73) cells per microliter. In both groups, donors were significantly more likely to be female or white, have lower weight, lower BMI, lower estimated percentage body fat, lower pre–G-CSF platelet, and total mononuclear cell counts, and to have received lower total amounts of G-CSF compared with donors who did not have a poor mobilization. Furthermore, in each instance, the proportion of donors who were female or white was higher, and mean values for weight, BMI, estimated percentage body fat, pre–G-CSF platelet and mononuclear cell counts, and total G-CSF dose received tended to be lower in donors with a post–G-CSF CD34+ cell count of 20 cells/μL versus 30 cells/μL. There was no significant association with mean age or height, nor with the fraction of donors who received G-CSF at 16 versus 10 μg/kg per day. However, donors with poor mobilization responses tended to be older than those who did not mobilize poorly, and none of the donors who received G-CSF dosed at 16 μg/kg per day exhibited a poor mobilization. Finally, there was no significant difference in the proportion of donors who underwent a prior lymphapheresis for DLI collection in those with versus those without a poor mobilization response, reflecting the fact that the impact of this procedure was less evident on donors with low body weight, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 5.

Clinical and laboratory data in donors with a poor mobilization response to G-CSF

| Post–G-CSF CD34+ cell count/μL | N | Sex, female/male, % | Ethnicity W/B/H/AP, % | G-CSF dose, μg/kg per day 10/16, % | Weight, kg | Height, cm | BMI, kg/m2 | Estimated body fat, % | Age, y | Pre–G-CSF platelet count, ×109/L | Pre–G-CSF MNC, ×109/L | Total G-CSF, μg/d | Prior lymphapheresis, yes/no (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All donors | 639 | 49/51 | 64/12/18/6 | 96/4 | 79 | 170 | 27.1 | 28.7 | 40.4 | 256 | 2.43 | 808 | 26/74 |

| Less than 30 | 73 | 70/30 | 78/3/14/5 | 100/0 | 68 | 169 | 23.4 | 25.8 | 41.7 | 236 | 2.21 | 688 | 22/78 |

| More than or equal to 30 | 566 | 48/52 | 64/13/19/6 | 95/5 | 80 | 171 | 27.5 | 29.1 | 40.3 | 259 | 2.46 | 822 | 26/74 |

| P | <.001 | .01 | .1 | <.001 | .12 | <.001 | <.001 | .3 | .002 | .002 | <.001 | .4 | |

| Less than 20 | 29 | 74/26 | 81/4/15/0 | 100/0 | 67 | 170 | 22.9 | 24.6 | 41.9 | 226 | 1.96 | 663 | 15/85 |

| More than or equal to 20 | 610 | 49/51 | 64/12/18/6 | 95/5 | 79 | 170 | 27.1 | 28.9 | 40.4 | 260 | 2.45 | 812 | 26/74 |

| P | .02 | .08 | .6 | <.001 | .4 | <.001 | <.001 | .4 | .006 | <.001 | <.001 | .3 |

Discussion

This study represents the largest published analysis of PBSC yields in allogeneic donors. It is also the only series to examine the effect of donor ethnicity on CD34+ mobilization responses. We found that the single strongest factor affecting CD34+ apheresis yields was the total amount of G-CSF administered to the donor and that donor age, gender, and weight had reduced impact after accounting for this parameter. Furthermore, donor ethnicity significantly affected CD34+ mobilization response, a novel finding that remained strongly significant in multivariate analysis. White donors had the lowest CD34+ cell counts and black donors had the highest CD34+ cell counts after mobilization, whereas Asian/Pacific donors had the highest CD34+ cell counts when adjusted for BMI and body weight. Although a wide variation in individual responses to G-CSF has been reported,20 the reason for a blunted CD34+ response to G-CSF in white donors is unknown. Our data indicate that donor ethnicity may play a significant role in the mobilization response to G-CSF and should be taken into account in designing mobilization regimens.

Our findings for mobilized PBSC counts in black donors are in contrast with those reported in cord blood collections,21 wherein blacks have been noted to have lower CD34+ cell counts. Similarly, reference values for unstimulated total white cell and neutrophil counts are also known to be lower in blacks than other races.22 Several small reports have also shown that blacks did not increase their total leukocyte counts as much as whites after one dose of hydrocortisone23 or after participating in athletic activity.24,25 A trend toward more robust CD34+ mobilization in black subjects with sickle cell trait versus those without trait was noted in a small number of healthy donors undergoing PBSC collection26; however, we did not evaluate the presence of sickle cell trait among our donors.

The significant variation in PBSC mobilization response between ethnic groups suggests that there may be genetic regulation of mobilization response. Quantitative variations in PBSC mobilization response to G-CSF have been noted in inbred strains of mice. Genetic analysis of high-responder (DBA/2) and poor-responder (C57BL/6) mice revealed that progenitor cell release in response to G-CSF was linked to loci on chromosomes 2 and 11.27,28 Similar laboratory studies in humans are necessary to determine genetic loci that control progenitor mobilization response. Genetic variations could exist in putative stem cell pool size, intrinsic migration properties of hematopoietic stem cells, or interaction of stem cells with stromal and endothelial cell types in the bone marrow niche.29

We found that increasing donor age was associated with a modest negative effect on CD34+ mobilization response. A smaller study by Anderlini et al11 similarly reported that older age is associated with poor mobilization, a finding extended to female donors by Ings et al,30 who concluded that, given a choice, larger, male donors younger than 55 years would be preferable. In contrast, other groups have reported that age is not a significant predictive factor.12,31 In murine studies designed to determine whether aging is associated with changes in stem cell pool size or altered progenitor cell response to cytokines, Xing et al found that aged mice exhibit better mobilization responses to G-CSF and that their hematopoietic progenitor cells were characterized by reduced adhesion to marrow stroma.32

The effect of higher G-CSF doses on enhancement of CD34+ mobilization responses in this analysis is consistent with prior studies. One study compared G-CSF 12 μg/kg twice daily to a single 10 μg/kg per day dose and found that the higher dose was associated with higher CD34+ cell yields by apheresis.33 Other studies reported that a given dose split into twice daily subcutaneous injections may be preferable to a single daily dose.31,34

We also studied the effect of a prior lymphapheresis on subsequent PBSC yield, an association that might have practical implications given the frequent use of this modality in current transplant approaches. Our data indicate that lymphapheresis before PBSC mobilization is safe and acceptable in terms of associated changes in hemoglobin levels and platelet counts. Interestingly, donors who underwent prior lymphapheresis had significantly higher CD34+ apheresis yields than donors who did not undergo this procedure. This is consistent with a study performed by Korbling et al,35 before cytokine use for mobilization, in which successive, frequent leukapheresis procedures were associated with significantly increased granulocyte/macrophage progenitor cell (CFUc) yields. In another study, even a single unstimulated leukapheresis was shown to increase subsequent levels of circulating progenitor cells in peripheral blood.36 It is notable that circulating donor platelet levels in the present study as well as in these prior reports were significantly reduced after apheresis secondary to platelet loss in the apheresis device and product. This apheresis-related thrombocytopenia might have resulted in increased thrombopoietin levels because thrombopoietin is constitutively produced and blood levels are inversely proportional to circulating platelet levels.37 Indeed, prior studies have shown that serum thrombopoietin levels are increased after plateletpheresis procedures for platelet donation.38,39 In turn, increased thrombopoietin levels might lead to enhanced CD34+ responses because of expansion of the marrow progenitor pool.40 It is also possible that the relative lymphopenia produced after lymphapheresis might have resulted in a positive effect on mobilization through a process similar to homeostatic recycling and peripheral expansion, which has been reported to occur for T cells in lymphopenic states.41

In addition to these effects, the actions of intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) in mediating stem cell homing to the marrow microenvironment may also play a role during apheresis.42 Parathyroid hormone increases the expression of the PTH/PTHrP receptor (PTH1R) on osteoblasts and increases the number and activity of osteoblasts in stromal cell cultures. Activation of osteoblasts alters the hematopoietic stem cell niche, resulting in stem cell expansion in vitro and in vivo and dramatically improving the survival of mice receiving bone marrow transplants. Osteoblastic cells appear to be a regulatory component of the stem cell niche in vivo.43 Interestingly, the citrate administered during leukapheresis has been shown to induce 100% to 300% increases in iPTH immediately after apheresis, with persistent 10% to 20% increases in iPTH observed for up to 4 days after lymphapheresis procedures in healthy donors.44 In the current study, donors who began PBSC mobilization within 2 days after undergoing lymphapheresis were likely to have had elevated circulating iPTH levels, which in turn may have contributed to hematopoietic stem cell growth and resulted in higher CD34+ yields. Parathyroid hormone effects might also partly explain the higher CD34+ mobilization responses seen in black males, as this population is known to have increased bone mass45 and bone mineral content,46 and at least one study has shown significant increases in serum iPTH in black males.47 Further studies are indicated to confirm these observations, as iPTH levels were not measured in this study.

In this study, baseline pre–G-CSF platelet counts were strongly associated with CD34+ cell counts after mobilization in both univariate and multivariate analyses. Similar findings have been reported in an Asian population by Suzuya et al,10 who found that higher baseline platelet counts and platelet counts during mobilization were associated with higher CD34+ apheresis yields in a population of 119 donors. We also found that the total mononuclear cell count before G-CSF administration was significantly associated with subsequent CD34+ cell counts, an effect that was independent of the association with platelet counts. Interestingly, the CD34+ cell count associations with baseline levels of both platelets and mononuclear cells in this study were strongest in donors of Asian/Pacific ethnicity. Our data thus confirm and extend the findings of Suzuya et al,10 in a larger study of donors of diverse backgrounds.

The association of higher baseline platelet counts with improved CD34+ mobilization may be related to common pathways of thrombopoiesis and progenitor cell mobility. Increased plasma levels of SDF-1 have been shown to enhance human thrombopoiesis and mobilize human colony forming cells in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency mice.48 In addition, CD34+ cells may exhibit changes similar to platelet-derived microparticles during G-CSF mobilization.49 Chemokine-mediated interactions of hematopoietic progenitors with the bone marrow vascular niche may also allow progenitors to relocate to a microenvironment that is permissive for megakaryocyte maturation and thrombopoiesis.40

Our study indicates that donors with a poor mobilization response to G-CSF are more likely to have received a low total amount of G-CSF and to be white, female, and older, and to have lower BMI and lower baseline platelet and mononuclear cell counts. The data allow an educated assessment of risk for either a poor or an excessively robust mobilization response and allow a priori intervention with a higher or lower total G-CSF dose to mitigate the effect of otherwise fixed demographic factors. Such strategies could be used in cases where lighter-weight donors are matched with heavier-weight recipients or in situations where additional CD34+ cells are required for ex vivo graft manipulation. In unrelated donor programs where a fixed dose of G-CSF is prescribed, selection of younger, male donors might be considered to optimize responses when higher cell doses are desired. Furthermore, with the development of newer mobilizing agents, such as CXCR4 antagonists, knowledge of predictive factors for mobilization to G-CSF may potentially be used to determine the best mobilizing agent for a donor. Use of this information in clinical mobilization protocols could also result in overall benefit to donors, avoidance of multiple apheresis procedures, maximization of cell yields by apheresis, and improved transplantation outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gail Birmingham, Karen Diggs, De Gladden, and the outstanding staff of the Dowling Apheresis Clinic for the care of the donors during the performance of the apheresis procedures, Dr Harvey Klein for his support for the conduct of the study and preparation of the manuscript, and the research nurses, clinical fellows, and staff of the clinical teams of National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for their evaluation, management, and recruitment of donors.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not to be construed as the official position of the United States Department of Health and Human Services or the United States Public Health Service.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.V. wrote the paper and interpreted data; S.F.L. designed research and analyzed data; J.F.T., M.M.H., R.W.C., A.J.B., D.H.F., M.R.B., E.M.K., H.L.M., H.M.K., and C.E.D. performed research and provided clinical data; Y.Y.Y. designed research, performed research, collected data, and analyzed data; R.W. provided statistical expertise; and C.D.B. designed research and analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Charles D. Bolan, Hematology Branch, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Building 10, CRC Room 4-5140, MSC 1202, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: cbolan@nhlbi.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Bensinger WI, Martin PJ, Storer B, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow as compared with peripheral-blood cells from HLA-identical relatives in patients with hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:175–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korbling M, Przepiorka D, Huh YO, et al. Allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation for refractory leukemia and lymphoma: potential advantage of blood over marrow allografts. Blood. 1995;85:1659–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Schmid O, et al. Change in stem cell source for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in Europe: a report of the EBMT activity survey 2003. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:575–590. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolan CD, Carter CS, Wesley RA, et al. Prospective evaluation of cell kinetics, yields and donor experiences during a single large-volume apheresis vs two smaller volume consecutive day collections of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cells. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:801–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeyama K, Ohto H. PBSC mobilization. Transfus Apher Sci. 2004;31:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savani BN, Rezvani K, Mielke S, et al. Factors associated with early molecular remission after T cell-depleted allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:1688–1695. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ringden O, Barrett AJ, Zhang MJ, et al. Decreased treatment failure in recipients of HLA-identical bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplants with high CD34 cell doses. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:874–885. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhedin N, Chamakhi I, Perreault C, et al. Evidence that donor intrinsic response to G-CSF is the best predictor of acute graft-vs-host disease following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Przepiorka D, Smith TL, Folloder J, et al. Risk factors for acute graft-vs-host disease after allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:1465–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuya H, Watanabe T, Nakagawa R, et al. Factors associated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-induced peripheral blood stem cell yield in healthy donors. Vox Sang. 2005;89:229–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderlini P, Przepiorka D, Seong C, et al. Factors affecting mobilization of CD34+ cells in normal donors treated with filgrastim. Transfusion. 1997;37:507–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37597293882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miflin G, Charley C, Stainer C, et al. Stem cell mobilization in normal donors for allogeneic transplantation: analysis of safety and factors affecting efficacy. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:345–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grigg AP, Roberts AW, Raunow H, et al. Optimizing dose and scheduling of filgrastim (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) for mobilization and collection of peripheral blood progenitor cells in normal volunteers. Blood. 1995;86:4437–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Childs R, Chernoff A, Contentin N, et al. Regression of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma after nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral-blood stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:750–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009143431101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horwitz ME, Barrett AJ, Brown MR, et al. Treatment of chronic granulomatous disease with nonmyeloablative conditioning and a T-cell-depleted hematopoietic allograft. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:881–888. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler DH, Odom J, Steinberg SM, et al. Phase I clinical trial of costimulated, IL-4 polarized donor CD4+ T cells as augmentation of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy NM, Fowler DH, Bishop MR. Immunotherapy of metastatic breast cancer: phase I trail of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with Th2/Tc2 T-cell exchange. Clin Breast Cancer. 2006;7:87–89. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2006.n.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolan CD, Cecco SA, Wesley RA, et al. Controlled study of citrate effects and response to i.v. calcium administration during allogeneic peripheral blood progenitor cell donation. Transfusion. 2002;42:935–946. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moncada V, Bolan C, Yau YY, Leitman SF. Analysis of PBPC cell yields during large-volume leukapheresis of subjects with a poor mobilization response to filgrastim. Transfusion. 2003;43:495–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts AW, DeLuca E, Begley CG, et al. Broad inter-individual variations in circulating progenitor cell numbers induced by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor therapy. Stem Cells. 1995;13:512–516. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530130508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballen KK, Kurtzberg J, Lane TA, et al. Racial diversity with high nucleated cell counts and CD34 counts achieved in a national network of cord blood banks. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh MM, Everhart JE, Byrd-Holt DD, Tisdale JF, Rodgers GP. Prevalence of neutropenia in the U.S. population: age, sex, smoking status, and ethnic differences. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:486–492. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason BA, Lessin L, Schechter GP. Marrow granulocyte reserves in black Americans: hydrocortisone-induced granulocytosis in the “benign” neutropenia of the black. Am J Med. 1979;67:201–205. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bain BJ, Phillips D, Thomson K, Richardson D, Gabriel I. Investigation of the effect of marathon running on leucocyte counts of subjects of different ethnic origins: relevance to the aetiology of ethnic neutropenia. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:483–487. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson HG, Meiklejohn DJ. Leucopenia in professional football players. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:826–827. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02616-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang EM, Areman EM, David-Ocampo V, et al. Mobilization, collection, and processing of peripheral blood stem cells in individuals with sickle cell trait. Blood. 2002;99:850–855. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa M, Baldwin TM, Metcalf D, Foote SJ. Progenitor cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor controlled by loci on chromosomes 2 and 11. Blood. 2000;95:1872–1874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geiger H, Szilvassy SJ, Ragland P, Van ZG. Genetic analysis of progenitor cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: verification and mechanisms for loci on murine chromosomes 2 and 11. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henckaerts E, Geiger H, Langer JC, et al. Genetically determined variation in the number of phenotypically defined hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells and in their response to early-acting cytokines. Blood. 2002;99:3947–3954. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ings SJ, Balsa C, Leverett D, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell yield in 400 normal donors mobilised with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): impact of age, sex, donor weight and type of G-CSF used. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:517–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arbona C, Prosper F, Benet I, et al. Comparison between once a day vs twice a day G-CSF for mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) in normal donors for allogeneic PBPC transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:39–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing Z, Ryan MA, Daria D, et al. Increased hematopoietic stem cell mobilization in aged mice. Blood. 2006;108:2190–2197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-010272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelhardt M, Bertz H, Afting M, Waller CF, Finke J. High-vs standard-dose filgrastim (rhG-CSF) for mobilization of peripheral-blood progenitor cells from allogeneic donors and CD34(+) immuno-selection. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2160–2172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroger N, Renges H, Kruger W, et al. A randomized comparison of once vs twice daily recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) for stem cell mobilization in healthy donors for allogeneic transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:761–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korbling M, Fliedner TM, Pflieger H. Collection of large quantities of granulocyte/macrophage progenitor cells (CFUc) in man by means of continuous-flow leukapheresis. Scand J Haematol. 1980;24:22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1980.tb01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillyer CD, Tiegerman KO, Berkman EM. Increase in circulating colony-forming units-granulocyte-macrophage during large-volume leukapheresis: evaluation of a new cell separator. Transfusion. 1991;31:327–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31491213297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuter DJ. The physiology of platelet production. Stem Cells. 1996;14(Suppl 1):88–101. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530140711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dettke M, Hlousek M, Kurz M, et al. Increase in endogenous thrombopoietin in healthy donors after automated plateletpheresis. Transfusion. 1998;38:449–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38598297213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisbach V, Friedlein H, Glaser A, et al. The influence of automated plateletpheresis on systemic levels of hematopoietic growth factors. Transfusion. 1999;39:889–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39080889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avecilla ST, Hattori K, Heissig B, et al. Chemokine-mediated interaction of hematopoietic progenitors with the bone marrow vascular niche is required for thrombopoiesis. Nat Med. 2004;10:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guimond M, Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Cytokine signals in T-cell homeostasis. J Immunother. 2005;28:289–294. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000165356.03924.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calvi LM. Osteoblastic activation in the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1068:477–488. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolan CD, Ronquillo JJ, Yau YY, Leitman SF. Citrate effects and bone mineral density in serial long-term apheresis donors [abstract]. Blood. 2006;108:284a. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Araujo AB, Travison TG, Harris SS, et al. Race/ethnic differences in bone mineral density in men. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:943–953. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell NH, Gordon L, Stevens J, Shary JR. Demonstration that bone mineral density of the lumbar spine, trochanter, and femoral neck is higher in black than in white young men. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;56:11–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00298737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell NH, Greene A, Epstein S, et al. Evidence for alteration of the vitamin D-endocrine system in blacks. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:470–473. doi: 10.1172/JCI111995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perez LE, Alpdogan O, Shieh JH, et al. Increased plasma levels of stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) enhance human thrombopoiesis and mobilize human colony-forming cells (CFC) in NOD/SCID mice. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nomura S, Inami N, Kanazawa S, Iwasaka T, Fukuhara S. Elevation of platelet activation markers and chemokines during peripheral blood stem cell harvest with G-CSF. Stem Cells. 2004;22:696–703. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-5-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]