Summary

Acupuncture has been used therapeutically in China for thousands of years and is growing in prominence in Europe and the United States. In a recent review of complementary and alternative medicine use in the US population, an estimated 2.1 million people or 1.1% of the population sought acupuncture care during the past 12 months. Four percent of the US population used acupuncture at any time in their lives. We reviewed 31 different published journal articles, including 23 randomized controlled clinical trials and 8 meta-analysis/systematic reviews. We found evidence of some efficacy and low risk associated with acupuncture in pediatrics. From all the conditions we reviewed, the most extensive research has looked into acupuncture’s role in managing postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting. Postoperatively, there is far more evidence of acupuncture’s efficacy for pediatrics than for children treated with chemotherapy. Acupuncture seems to be most effective in preventing postoperative induced nausea in children. For adults, research shows that acupuncture can inhibit chemotherapy-related acute vomiting, but conclusions about its effects in pediatrics cannot be made on the basis of the available published clinical trials data to date. Besides nausea and vomiting, research conducted in pain has yielded the most convincing results on acupuncture efficacy. Musculoskeletal and cancer-related pain commonly affectss children and adults, but unfortunately, mostly adult studies have been conducted thus far. Because the manifestations of pain can be different in children than in adults, data cannot be extrapolated from adult research. Systematic reviews have shown that existing data often lack adequate control groups and sample sizes. Vas et al, Alimi et al, and Mehling et al demonstrated some relief for adults treated with acupuncture but we could not find any well-conducted randomized controlled studies that looked at pediatrics and acupuncture exclusively. Pain is often unresolved from drug therapy, thus there is a need for more studies in this setting. For seasonal allergic rhinitis, we reviewed studies conducted by Ng et al and Xue et al in children and adults, respectively. Both populations showed some relief of symptoms through acupuncture, but questions remain about treatment logistics. Additionally, there are limited indications that acupuncture may help cure children afflicted with nocturnal enuresis. Systematic reviews show that current published trials have suffered from low trial quality, including small sample sizes. Other areas of pediatric afflictions we reviewed that suffer from lack of research include asthma, other neurologic conditions, gastrointestinal disorders, and addiction. Acupuncture has become a dominant complementary and alternative modality in clinical practice today, but its associated risk has been questioned. The National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement states “one of the advantages of acupuncture is that the incidence of adverse effects is substantially lower than that of many drugs or other accepted procedures for the same conditions.” A review of serious adverse events by White et al found the risk of a major complication occurring to have an incidence between 1:10,000 and 1:100,000, which is considered “very low.” Another study found that the risk of a serious adverse event occurring from acupuncture therapy is the same as taking penicillin. The safety of acupuncture is a serious concern, particularly in pediatrics. Because acupuncture’s mechanism is not known, the use of needles in children becomes questionable. For example, acupoints on the vertex of infants should not be needled when the fontanel is not closed. It is also advisable to apply few needles or delay treatment to the children who have overeaten, are overfatigued, or are very weak. Through our review of pediatric adverse events, we found a 1.55 risk of adverse events occurring in 100 treatments of acupuncture that coincides with the low risk detailed in the studies mentioned previously. The actual risk to an individual patient is hard to determine because certain patients, such as an immunosuppressed patient, can be predisposed to an increased risk, acupuncturist’s qualifications differ, and practices vary in certain parts of the world. Nevertheless, it seems acupuncture is a safe complementary/alternative medicine modality for pediatric patients on the basis of the data we reviewed.

Keywords: acupuncture, pediatrics, review, side effects

Acupuncture has been used therapeutically in China for thousands of years and is growing in prominence in Europe and the United States.1 In a recent review of complementary and alternative medicine use in the US population, an estimated 2.1 million people or 1.1% of the population sought acupuncture care during the past 12 months. Four percent of the US population used acupuncture at any time in their lives.2 The National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement of 1997 concluded that acupuncture is efficacious in treating adult postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and dental pain.3 Acupuncture may be useful in treating conditions such as addiction, headache, myofascial pain, and asthma. In addition to adult healthcare, acupuncture is increasingly being integrated into pediatric care. Traditional Chinese medicine believes that children are not developed physiologically, anatomically, or energetically, but they tend to respond positively to acupuncture because they have accessible acupoints through their extremities, abdomen, and face.4 One-third of pediatric pain centers in the U S now offer acupuncture as a part of their services.5 Pediatricians are beginning to recognize the value of acupuncture as a helpful and valid treatment option.

The precise mechanisms explaining acupuncture’s effects have been debated. The dominant explanation in published clinical trials is that acupuncture results in stimulation and release of neurochemicals, such as β endorphins, enkephalins, and serotonin.6 In research in animals, acupuncture changed in opioidergic and/or monoaminergic neurotransmission activity in the brainstem, thalamus, hypothalamus, and/or pituitary.7 Another leading theory suggests that acupuncture’s effects are mediated through regulation of the autonomic nervous system. Specific to the site of stimulation, acupuncture can alter sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity.8 Electroacupuncture can result in reduced sympathetic activity.9 Acupuncture may also increase local blood flow and nitric oxide production. Because sham acupuncture does not produce similar results, these outcomes are related to specific acupoints and meridians and could be attributable to pain relief.10

The practice of acupuncture in children is more complex than in adult healthcare. A difficulty in treating the pediatric population is children’s fear of needles.11 Practitioners stress the importance of reducing anxiety and establishing a friendly and trusting environment before the administration of acupuncture. Toys, like hand puppets, or pictures can be used to relax children and reduce their anxiety. Some children have increased acceptance of acupuncture when testing acupressure first.12 For those under the age of 6 years, longer needles are often replaced with shorter needles for ease of insertion and control.13 As retention time of needle insertions is not tolerated in children as it is in adults, treatment periods are reduced compared with the treatment of adults and closely monitored.13 Once a child displays signs of overstimulation, such as irritability, flushing, lethargy, or restlessness, treatment must be stopped. The length of a child’s tolerance tends to increase with age.13 Noninvasive modalities, such as electrical stimulation or laser, on acupoints and acupressure seem to be well accepted by younger children.

Despite the lack of complete physiologic understanding, acupuncture is a significant modality in eastern medicine and is gaining credibility in the western world. Although a great deal of research is being conducted on the safety and efficacy of acupuncture in adults and several comprehensive reviews of clinical research results have been published recently, acupuncture in the pediatric population has received less attention and scientific reviews. This paper reviews the evidence base for the safety and efficacy of acupuncture in pediatrics and discusses research opportunities to advance the knowledge on the use of acupuncture in children.

METHODS

We searched Medline, EMBASE, AMED, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and CINAHL all from time of inception to June 2007. The search terms used were “acupuncture, acupuncture therapy, pediatrics, infant, neonate, newborn, child, and adolescent.” Only randomized controlled clinical trials, meta-analysis reviews, and systematic reviews were included. We did not include nonrandomized trials, case series, or case reports. We sorted published material on the basis of their indications and included the most significant, pertinent, and recent data for review. In addition, the randomized controlled clinical trials that included adverse events data were cataloged.

EFFICACY

Nausea and Vomiting

Perhaps the most significant research has been conducted on acupuncture’s effects on nausea and vomiting (Table 1 for article summaries). In traditional Chinese medicine, the acupoint P6 (Neiguan) of the Pericardium Meridian is commonly known to control symptoms of nausea and vomiting.18 P6 is located 2 cun above the transverse crease of the wrist, between the tendons of palmaris longus and flexor radialis. One cun is a Chinese inch equivalent to the width of the inter-phalangeal joint of the patient’s thumb.20 P6 can be stimulated by needle insertion and manipulation (acupuncture), electrically stimulating the inserted needle (electroacupuncture), electrically stimulating the skin without a needle (noninvasive electroacupuncture), applying pressure (acupressure), or directing a laser beam to the acupoint (laser stimulation).20

TABLE 1.

Efficacy Chart Detailing the 32 Articles That Describe Acupuncture’s Effectiveness for Specific Indications

| Indication | Reference | Study Type | n | Experimental Group | Controls | Strongest Benefit Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting | Dundee et al14 | Randomized controlled trial | 11 | Electroacupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Electroacupuncture reduced chemotherapy induced sickness for at least 8 h, sham acupuncture showed no benefit |

| Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting | Reindl et al15 | Prospective Randomized multicenter controlled trial | 11 | Acupuncture | No acupuncture | No differences in episodes of vomiting (P = 0.374); need for additional antiemetic medication was decreased in courses with acupuncture (0.024) |

| Chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting | Molassiotis et al16 | Randomized controlled trial | 36 | Acupressure with wrist Bands | Antiemetics only | Nausea and retching experience were lower in experimental group vs. control group (P < 0.05) |

| Chemotherapy induced vomiting | Shen et al17 | Randomized controlled trial | 104 | Electroacupuncture | (1) Minimal needling with mock electrostimulation (2) antiemetic drugs alone | Electroacupuncture was more effective in controlling emesis than minimal needling or pharmacotherapy alone (P<0.001) |

| Chemotherapy induced vomiting | Ezzo et al18 | Cochrane review | 1247 | Acupuncture/electroacupuncture/noninvasive electrostimulation | Sham acupuncture/electroacupuncture/noninvasive electrostimulation | Acupuncture methods combined reduces the incidence of vomiting (P = 0.004) |

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Lee and Lenti13 | Cochrane review | 3347 | Acupuncture | Antiemetics | Reduction in the risk of nausea with P6 stimulation compared with sham treatment groups, without prophylaxis medication (RR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.59–0.89) |

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Dune and Shiao4 | Meta-analysis | 1037 | Acupuncture | Antiemetics | All acupuncture modalities showed reduction in vomiting (P < 0.0001) and nausea (P < 0.0001) when compared with control groups |

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Streitberger et al19 | Randomized double- blinded controlled | 220 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Acupuncture patients showed a 24.8% incidence of vomiting compared with 39.6% in the placebo group (P = 0.03) |

| Post-operative induced nausea and vomiting | Butkovic et al20 | Randomized prospective study | 120 | Laser Acupuncture at P6 w/saline IV | (1) Metoclopramide IV with sham laser (2) sham laser and saline IV | Laser acupuncture is just as effective as the antiemetic metoclopramide in children undergoing general anesthesia |

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Wang and Kain21 | Randomized double blinded controlled | 187 | Acupuncture w/saline IV | (1) Droperidol with sham acupuncture (2) saline IV with sham acupuncture (3) saline IV with sham point injections | Acupuncture group no. 1 and group no. 2 produced similar incidents of nausea and vomiting |

| Post-operative induced nausea and vomiting | Rusy et al22 | Randomized controlled trial | 120 | Electroacupuncture | (1) Sham electroacupuncture (2) no acupuncture | Acupuncture groups showed a significant reduction in nausea (P = 0.0007) vs. sham acupuncture and controls. No significant differences in the incidence of vomiting |

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Somri et al23 | Randomized controlled trial | 90 | Acupuncture | (1) Ondansetron IV (2) IV saline | The acupuncture and ondansetron groups showed a significant reduction in the number of vomiting episodes on the day of surgery (P < 0.0001) compared with placebo |

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Shenkman et al24 | Randomized controlled trial | 100 | Acupressure/acupuncture | Sham acupressure/acupuncture | There were no significant differences between the study and control groups for retching (26% vs. 28%, respectively) or vomiting (60% vs. 59%, respectively) |

| Postoperative induced vomiting | Schlager et al25 | Prospective randomized double- blinded controlled trial | 40 | Laser acupuncture | Sham laser acupuncture | Those receiving laser acupuncture had an incidence of vomiting of 25% in the first 24 h after surgery compared with 85% in the placebo group |

| Chronic asthma | McCarney et al26 | Cochrane review | 324 | Needle or laser acupuncture | Sham needle or sham laser acupuncture | Inconclusive |

| SAR | Ng et al27 | Randomized double blinded controlled | 63 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Experimental group had higher percentages of symptom free days (P−0.0001) and better scores for immediate improvement after acupuncture (P = 0.011) |

| SAR | Xue et al28 | Randomized double- blinded controlled trial | 52 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Experimental group had lower post-treatment SAR symptoms vs. sham acupuncture (P = 0.012) |

| Epilepsy | Cheuk and Wong29 | Cochrane review | 3 | Acupuncture alone or with Chinese Herbs | Sham acupuncture or chinese herbs alone | Inconclusive |

| Migraine | Diener et al30 | Prospective randomized double- blinded parallel- group controlled | 960 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture or standard drug therapy | All 3 groups showed a significant mean reduction of migraines compared with baseline (P < 0.0001) |

| Migraine | Allais et al31 | Randomized controlled trial | 150 | Acupuncture | Standard drug therapy (Flunarizine) | Pain intensity was only significantly lower in only those treated with acupuncture (P = 0.001) |

| Cancer pain | Alimi et al32 | Randomized controlled trial | 90 | Auricular acupuncture | (1) Auricular acupuncture at placebo points (2) Auricular seeds at placebo points | True auricular acupuncture caused a 36% decrease in pain intensity (P<0.001) 2 mo into treatment and control groups showed little if any reduction |

| Cancer pain | Mehling et al33 | Randomized controlled trial | 134 | Acupuncture/massage with usual care | Usual care | Patients in the acupuncture/massage group had a decrease of 1.4 points on a pain scale of 0–10 vs. only 0.6 reduction in the usual care group (P = 0.038) |

| Nocturnal enuresis | Glazener et al34 | Cochrane review | 1389 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Inconclusive |

| Nocturnal enuresis | Bower et al35 | Systematic review | 1274 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Inconclusive |

| Nocturnal enuresis | Radmayr et al36 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | 40 | Acupuncture | Desmopressin | Both groups showed complete success rates of >50%; no significant difference between groups |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Lim et al37 | Cochrane review | 6 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Inconclusive |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Forbes et al38 | Prospective randomized double- blinded controlled trial | 59 | Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | Patients in acupuncture and sham groups had significant equal study mean improvement scores (P<0.05) |

| Neck pain | Vas et al39 | Randomized controlled trial | 123 | Acupuncture | Transcutaneous nerve stimulation-placebo (TENS-placebo) | After 5 courses of treatment over 3 weeks, pain was lower among the acupuncture group (95% CI 21.4–34.7) |

| Low back pain | Thomas et al40 | Randomized controlled trial | 217 | Acupuncture | Usual care | Modest benefits were seen at 24 mo compared with usual care |

| Cocaine addiction | Margolin et al41 | Randomized controlled trial | 620 | Auricular acupuncture | (1) Sham acupuncture (2) Relaxation control | No difference was found among the 3 groups in reducing cocaine use |

| Alcohol withdrawal | Kunz et al42 | Randomized controlled trial | 74 | Auricular acupuncture | Aromatherapy | No distinction in withdrawal symptoms nor the extent of craving |

CI indicates confidence interval; IV, intravenous; RR, relative risk; SAR, seasonal allergic rhinitis.

Regardless of advances in antiemetics, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting continue to plague children. These symptoms can particularly influence quality of life, increase emotional distress, and intensify cancer-related cachexia, lethargy, and weakness. A recent meta-analysis conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration reviewed 11 different randomized trials and deduced that overall, acupuncture point P6 stimulation decreased the incidence of acute vomiting in adults.18 The most promising results are seen with electroacupuncture and the prevention of acute vomiting (occurring within 24-h postchemotherapy). In the meta-analysis, control groups had a 31% (154/500) incidence of vomiting compared with 22% (155/714) in the acupuncture groups [relative risk (RR) = 0.82, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.69–0.99, P = 0.04].18 Similar results were not found with acute or delayed nausea. One of the earliest multifacet studies conducted in 1989 by Dundee et al,14 revealed that although electroacupuncture reduced chemotherapy-induced sickness for at least 8 hours, sham acupuncture showed no benefit implying that placebo cannot account for their 97% success rate in 105 treated patients.

Some evidence shows acupressure may be effective in controlling chemotherapy-induced nausea. A randomized, controlled trail examining the effects of acupres-sure application through wrist bands in breast cancer patients found nausea to be lower in the experimental group compared with the control group (P < 0.05) across a 5-day assessment period postchemotherapy.16 Interestingly, acupressure wrist bands did not significantly effect vomiting (P = 0.06). Electroacupuncture with breast cancer patients does show support for a reduction in emetic episodes during a similar 5-day assessment period after chemotherapy, supporting the Cochrane review.17

A multicenter crossover study targeting patients between the ages of 6 and 18 years conducted throughout pediatric oncology centers in Germany gave manual acupuncture during day 1 of chemotherapy and on subsequent days at the patient’s request. On further courses of chemotherapy, acupuncture is given alternately for 3 courses and then continued after at the patient’s request. Throughout all study courses, programmed and additional antiemetic medications were given to patients as needed. Published interim results comparing 22 courses with and without acupuncture showed no differences in episodes of vomiting (P = 0.374). Baseline medication requests were not statistically significant between courses (P = 0.074), although the need for additional antiemetic medication was decreased in courses with acupuncture (P = 0.024). Study investigators noted that acceptance of acupuncture among this young population was high, and acupuncture aided in higher levels of alertness during chemotherapy.15

Nausea and vomiting are also a significant side effect after postoperative procedures with local or systemic anesthesia. Within 24 hours of surgery, pediatric patients experience postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in 30% to 80% of cases.4 Concerns about side effects and cost effectiveness of pharmacologic agents have led to a focus on control through alternative approaches. Children under the age of 3 years often have trouble describing symptoms related to nausea and vomiting, making it difficult to anticipate medication needs.4 A Cochrane Database systematic review of 26 trials showed significant reduction in the risk of nausea with P6 stimulation compared with sham treatment groups, without prophylaxis medication (RR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.59–0.89). In children subgroup analysis, risk of nausea was also lower in experimental groups (RR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.51–0.80). Furthermore, a test of interaction indicated no difference in treatment effects in children verses adults (z statistic = −1.03, P = 0.30). When acupoint stimulation groups were examined against individual antiemetic groups, collectively acupuncture groups showed a significant decrease in the risk of nausea (RR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.50–0.98). Results were not emulated in symptoms of vomiting. The review recommends the use of P6 acupoint stimulation for nausea reduction without prophylaxis medication in postoperative situations.43

A meta-analysis focusing on children published after the previously referenced Cochrane review suggests additional findings. Twelve trials were reviewed with ages of participants ranging from 4 to 18 years, with a mean age of 6.38 years. The 12 trials examined vomiting and 2 of them looked at nausea for 24-hour outcomes. All acupuncture modalities showed reduction in vomiting (RR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.59–0.80, P < 0.0001) and nausea (RR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.46–0.76, P < 0.0001) when compared with control groups. There was no difference between antiemetic and experimental groups in the incidence of vomiting, suggesting equivalent effectiveness between medication and acupuncture.4

Equivalency trials have studied acupuncture’s effect against antiemetic medications including ondansetron, droperidol, and metoclopramide. Somri et al23 randomly assigned 90 children undergoing dental surgery, ages 4 to 12 years, to receive either acupuncture through needle insertion group or intravenous (IV) ondansetron or IV saline as controls. The acupuncture and ondansetron groups showed a significant reduction in the number of vomiting episodes on the day of surgery (P < 0.0001) compared with placebo, and also showed a smaller proportion of patients having emetic incidents (P = 0.0004, P = 0.001). Somri et al23 concluded that acupuncture can be used in lieu of antiemetics for prophylactic dental surgery treatment. Another study, conducted by Wang and Kain,21 looked at acupuncture’s effects versus droperidol in children aged 7 to 16 years. All 187 study participants had outpatient surgical procedures under general anesthesia and were randomized to 1 of 4 groups: (1) acupuncture at P6 in addition to IV saline, (2) droperidol IV with sham P6 acupuncture, (3) IV saline with sham P6 acupuncture, and (4) IV saline with sham point injections. Acupuncture group no. 1 had a significantly lower incidence of nausea and vomiting when compared with P6 sham group no. 3 (n = 32% vs. 64%, P = 0.002; v = 12% vs. 31%, P = 0.029) and sham point group no. 4 (n = 32% vs. 56%, P = 0.029; v = 12% vs. 33%, P = 0.026). But acupuncture group no. 1 and droperidol group no. 2 produced similar incidents of nausea and vomiting [n = 32% vs. 46%, P = not significant (ns); v = 12% vs. 18%, P = ns]. Butkovic et al20 found laser acupuncture to be just as effective as the antiemetic metoclopramide in children undergoing general anesthesia. The 120 children included in the study underwent hernia repair, circumcision, or orchidopexy, with ages varying from 5 to 14 years. They were randomized into 3 groups receiving either (1) laser acupuncture at P6 and saline infusion, (2) metoclopramide IV and sham laser, or (3) sham laser and saline infusion. There was no significant difference between acupuncture and metoclopramide groups in timing and occurrence of vomiting (P < 0.0001). Those receiving sham laser and infusion showed a greater frequency of vomiting during the first 2 hours postoperatively (P < 0.001). These results support the conclusion of P6 acupuncture being equivalently effective to standard antiemetic treatments for PONV.

Rusy et al22 examined electroacupuncture prophylaxis’s effects on PONV in awake patients. One hundred and twenty patients (4 to 18 y old) were randomized to receive either P6 acupuncture, sham acupuncture, or no acupuncture after undergoing tonsillectomy (with or without adenoidectomy). All patients received oral midazolam before anesthesia with halothane or sevoflurane with 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen administered via mask. Acupuncture groups showed a significant reduction in those who experienced nausea (24 of 40 patients, 60%; P = 0.0007) versus sham acupuncture (34 of 40 patients, 85%; P = ns) and controls (31 of 40 patients, 78%). There were no significant differences in the incidence of vomiting in all the 3 groups. P6 acupuncture did have lower composite PONV incidence (63%, P = 0.0007) than controls (93%) and sham acupuncture (88%, P = ns). Rusy et al22 actually showed sham acupuncture to have 4.2 higher odds of PONV than P6 acupuncture. These results indicate considerable consequences of improperly administered acupuncture. Another study performed by Shenkman et al24 in children undergoing tonsillectomy presents comparable results with regards to emesis reduction. Hundred patients, ages 2 to 12 years, were assigned to an acupressure and acupuncture at P6 group or acupressure and acupuncture at a sham point control group. There were no significant differences between the study and control groups for retching (26% vs. 28%, respectively) or vomiting (60% vs. 59%, respectively).

Reduction of vomiting through acupuncture has been seen in adult patients. Streitberger et al19 gave either acupuncture at P6 or placebo acupuncture to 222 adult female patients going through gynecologic or breast surgery. Within 24 hours postsurgery, acupuncture patients showed a 24.8% incidence of vomiting compared with 39.6% in the placebo group (P = 0.03, 95% CI = −27.5%– −1.6%). Although needle acupuncture does not present promising results for pediatric postoperative vomiting reduction, laser acupuncture does. In a double-blinded prospective study, Schlager et al25 randomly assigned 40 children to either receive laser acupuncture at P6 stimulated by a low-level laser diode with continuous beam, or sham laser stimulation in which the same laser was held at P6 but not activated. Patients ranged in age from 3 to 12 years and all underwent strabismus surgery and received laser or sham laser acupuncture before and after surgery. Those receiving laser acupuncture had an incidence of vomiting of 25% in the first 24 hours after surgery (95% CI = 8.56%–49.10%) compared with 85% in the placebo group.

Asthma

In adults and children, asthma is the predominant form of chronic pulmonary disease. Eighty percent of those affectsed with asthma report disease onset before the age of 6 years.44 For most patients, symptoms can be controlled through medications, but the use of complementary therapies is being increasingly sought for their natural and often low-risk solutions.26 Furthermore, parents are often reluctant to give children steroids because of the many known adverse effects. Although Asian communities have traditionally used acupuncture to manage asthma for many years, clinical research trials results have been less than compelling. A Cochrane review of 11 studies comprised of 324 participants found trial quality and reporting to be weak.26 A meta-analysis could not be performed because monitoring and assessment methods varied fundamentally. Differences existed in the type of experimental and sham acupunctures used, durations of evaluation, and outcomes measured. No statistically significant differences were discovered between acupuncture versus sham acupuncture. Additionally, no clinically pertinent results were found. Overall, the review made no recommendations for clinical practice. The authors see an urgent need for increased rigor in future conducted research trials and a need for improved standardized control groups and comprehensive sham acupuncture information.26

Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis

Very few double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trials have been conducted on seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR), also known as hay fever, despite being a common condition. In the United States, a reported 20% of the population is affectsed, as high as 44% in Hong Kong27 and between 10% and 15% in the United Kingdom.28 Drugs currently used for management of SAR include antihistamines, corticosteroids, and mast cell stabilizers.28 Some SAR patients have found these medications ineffective or are unwilling to cope with side effects, consequently seeking alternative therapies for relief. Ng et al27 recruited 72 children over the age of 6 years and randomized them to receive either acupuncture or sham acupuncture for 8 weeks. During the 12-week follow-up period, the acupuncture group reported significantly better daily rhinitis scores (5.43 vs. 7.19 in the sham group, P = 0.03) and symptom free days (12.7 vs. 2.4 in the sham group, P = 0.0001). Symptom free days were also greater during the actual treatment period, with the acupuncture group reporting an average of 11.2 days and the sham group averaging only 3.7 symptom free days. (P = 0.0001). However, no significant differences were found in relief medication use, nasal or blood eosinophil counts, and serum immunoglobulin E levels. Furthermore, the benefits seen from acupuncture wore o3 after 10 weeks. Xue et al28 found similar results in a study of 30 adults who were first randomly treated with acupuncture or sham acupuncture for 4 weeks, and then received the alternate treatment for the following 4 weeks. When treated with acupuncture, the overall assessment of severity of symptoms showed a significant decrease post-treatment (t = −2.593, P = 0.012). These studies imply that acupuncture could be effective in relieving SAR symptoms, but treatment duration and frequency need to be further examined.

Neurologic Disorders

Nocturnal enuresis is the involuntary loss of urine at a developmental age of 5 years.34 Consensus agrees that by this age a child is expected to be dry at night (without the existence of disease).34 The causes are unclear, but standard therapy attempts to chemically alter neuromuscular structures and manipulate behaviors of children to influence arousal and bladder storage.35 Acupuncture attempts to induce homeostatic changes by strengthening the qi of the kidney and spleen and also regulating the brain. When Radmayr et al36 randomized 20 children aged between 5 and 16 years to receive either acupuncture or desmopressin alone and evaluated after 6 months, 75% and 65% of patients, respectively were completely dry. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups indicating acupuncture can be a valid alternative. A Cochrane review by Glazener et al34 found that acupuncture seems to offer some benefits over sham acupuncture and a combination of drug therapies, but too few study participants render conclusions on efficacy difficult to make. A systematic review by Bower et al35 also found tentative evidence for therapeutic benefits. Both reviews suggest further research be conducted with larger scale trials and greater methodologic quality.

Approximately 30% of patients with epilepsy continue to have seizures despite being treated with antiepileptic drugs.29 Some seek treatment through surgery and vagal nerve stimulation, but these procedures are still subject to complications. Unfortunately, there is no firm evidence whether acupuncture is effective for treating epilepsy. The Cochrane review cites 3 studies published to date that examine the effects of acupuncture with placebo or sham treatment. Two were plagued with control and randomization issues and the third found no evidence of symptom improvement.29

With many neurologic disorders, insuffcient information is available for adult populations and very little, if any, data relevant to pediatrics. Acupuncture shows some promise for depression, anxiety, cerebral palsy, neuropathy, and visual impairment, but limited information is available to date.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Acupuncture is thought to be applicable in treating gastrointestinal (GI) disorders because it conceivably alters GI motility, acid secretion, and visceral pain.45 Unfortunately, the investigations into acupuncture’s effectiveness in this area have not been extensive. Some work has been carried out using acupuncture to treat infantile diarrhea, infant colic, childhood constipation, and ulcerative colitis.46,47 Trials involved a small number of study participants and further research is needed to explore acupuncture’s role in these diseases. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one area where several studies have been performed. Therapies for IBS are aimed at treating GI motor/sensory dysfunction and central nervous system processing.37 In drug and acupuncture trials, many patients randomized to placebo groups report relief of IBS symptoms making short-term effects of therapeutic trials difficult to interpret.48 Forbes et al38 conducted a double-blinded prospective study in which 59 patients with IBS were randomized to receive acupuncture or sham acupuncture 10 times over 10 weeks. Those treated with acupuncture had a symptom score that dropped from 13.5 ± 4.51 to 11.6 ± 5.13 and those treated with sham acupuncture from 13.1 ± 4.30 to 11.2 ± 4.17. Both groups had a 1.9 point score improvement (P < 0.05). The Cochrane review by Lim et al37 also found similar results when patients were treated with true or sham acupuncture. The proportion of those who responded to treatment did not significantly vary between treatments, and there was no considerable difference in effectiveness for general well being or individual symptoms.

Pain

A recent survey found musculoskeletal pain to be the principal complaint of those who sought relief through acupuncture.49 The most common causes of chronic pain in children are headache, abdominal pain, back pain, chest pain, and cancer pain.50 Most systematic reviews have found current research for the acupuncture’s efficacy for pain relief insuffcient because of inadequate methodologic quality, sample size, and controls.39,51,52 Newer trials conducted with increased rigor show acupuncture may have some effectiveness. Vas et al39 conducted a randomized trial comparing acupuncture’s effects with transcutaneous nerve stimulation placebo in 123 participants with chronic neck pain. After 5 courses of treatment over 3 weeks, pain on a visual analog 0 to 100 point scale showed a greater decrease among the acupuncture group (28.1 mean point difference, 95% CI = 21.4–34.7). In a study of 241 adults with persistent nonspecific back pain, Thomas et al40 found weak evidence for the effectiveness of a 3-month course of acupuncture over 12 months, but modest benefits were seen at 24 months compared with usual care (drugs, back exercises, physiotherapy, and/or manipulation).

Preliminary information shows acupuncture may be effective in relieving chronic headaches and migraines. In a randomized controlled trial by Allais et al,31 150 women received no treatment for 2 months (run-in period) and were then treated with acupuncture or with an oral course of flunarizine (a common drug used for migraine therapy) for 6 months. Both groups showed a decrease in frequency of migraine attacks but pain intensity, however, was only significantly reduced in those treated with acupuncture (P = 0.001). Additionally, total number of patients experiencing side effects was significantly lower in the acupuncture group than in the drug therapy group (10/77 vs. 29/77, P = 0.007). At least one study by Diener et al30 shows that acupuncture may not provide additional benefits for patients. Nine hundred and sixty patients who suffered between 2 and 6 migraines/mo were randomized with acupuncture, sham acupuncture, or standard drug therapy for 6 weeks. Treatment outcomes were similar whether patients were treated with acupuncture, sham acupuncture, or drug therapy (β blockers, flunarizine, or valproic acid in a 1:1:1 ratio). Current studies primarily focus on adults; consequently, acupuncture’s efficacy in pediatric headaches remains to be determined.

For cancer patients, pain becomes a dominant physical and psychologic symptom.32 This type of chronic pain largely involves a neuropathic component even if connected with nociceptive pain.53 For cancer patients, neuropathic pain is very difficult to treat and generally does not benefit from drug therapy.53 Alimi et al32 researched the effects of cancer patients treated with true auricular acupuncture (n = 29) rather than sham acupuncture at placebo points (n = 28) or auricular seeds at placebo points (n = 30). True auricular acupuncture caused a 36% decrease in pain intensity (P < 0.001) 2 months into treatment and control groups showed little, if any, reduction. Acupuncture is also being researched in combination with other complementary therapies, such as massage and hypnosis, to treat pain. Mehling et al33 randomly assigned 138 cancer postoperative patients to receive usual care along with acupuncture and massage during the first 3 days after cancer-related surgery. Patients in the acupuncture/massage group had a decrease of 1.4 points on a pain scale of 0 to 10 versus only 0.6 reduction in the usual care group (P = 0.038). Acupuncture does seem to have some efficacy in pain, but investigations specifically targeting the pediatric population need to be carried out.

Addiction

Issues with addiction have plagued older children, although typically an adult condition. The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association codifies auricular acupuncture as one of the predominately used treatments used for cocaine addiction.41 A suggestion into the mechanism of auricular acupuncture’s efficacy is the production of a calming effect, decreased cravings, and/or retention promotion.41 When Margolin et al41 randomized 620 cocaine dependent adult patients to receive either auricular acupuncture, sham acupuncture, or a relaxation control condition (videos depicting relaxation strategies and visual imagery), no difference was found among the 3 groups in reducing cocaine use. In an alcohol withdrawal investigation, Kunz et al42 compared a group of 36 patients receiving auricular acupuncture with 38 patients who were treated with aromatherapy and discovered no distinction in withdrawal symptoms nor the extent of craving. Research in smoking cessation also suggests that acupuncture is not superior to any other antismoking interventions.54 Although often used for treatment in adults, the efficacy of auricular acupuncture needs to be further examined.

SAFETY

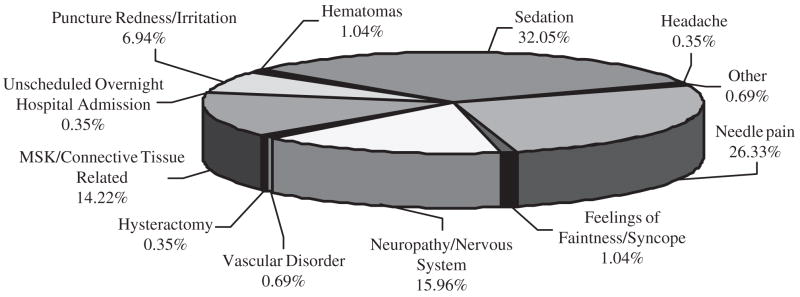

Our review included 22 randomized controlled clinical trials, which detailed the occurrence of adverse events, if any. Of those reported, the most frequent occurring reactions included sedation (30.98%), needle pain (25.44%), and neuropathy/nervous system-related issues (15.42%). Please see Figure 1 for a complete catalog of this data. In the 9 trials we reviewed that specifically targeted the pediatric population, a total of 29 acupuncture/sham acupuncture-related adverse reactions were reported. These trials included 782 patients ranging from ages 2 to 18 years (Table 2). The incidence rate of side effects is estimated to be 1.55/100 treatments of acupuncture or sham acupuncture. Among these pediatric adverse events, puncture redness was the most commonly reported side effect. A “serious” adverse event is defined as an event that “results in death, requires hospital admission or prolongation of existing hospital stay, results in persistent significant disability or incapacity, or is life-threatening.”55 Among 1865 total treatments given in the pediatric trials we reviewed, only 1 serious adverse event occurred. The risk of serious adverse events occurring is then estimated to be 5.36/10,000 treatments in pediatrics. Table 3 summarizes this data. One review estimated the risk of serious adverse events in the overall population to be as low as 0.05/10,000 treatments. The difference in values could be attributed to the nature of the study the 1 serious advent occurred in. The trial treated patients with acupuncture in an effort to prevent postoperative induced nausea and vomiting.23 As a result, 1 patient was admitted to the hospital and received IV ondansetron for emesis control; however, the identical adverse event occurred in control groups indicating acupuncture may not have directly caused the incident.

FIGURE 1.

Catalog of adverse events from the 22 randomized controlled clinical trials that reported such data. Sedation (32.05%), needle pain (26.33%), and neuropathy/nervous system-related issues (15.96%) occurred most frequently.

TABLE 2.

Detailed Adverse Events Data From the 9 Randomized Clinical Controlled Trials That Targeted the Pediatric Population Specifically

| Indication | Reference | n | Age Range | Total Treatments | Therapy | No. Adverse Events | Description of Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting | Reindl et al15 | 11 | 6–18 | 11 | Acupuncture | 1 | Needle pain |

| 11 | NA | No acupuncture | 0 | ||||

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Butkovic et al20 | 40 | 5–14 | 40 | Laser acupuncture at P6 with saline IV | 0 | None reported |

| 40 | 40 | Metaclopramide IV and sham laser | 0 | None reported | |||

| 40 | 40 | Sham laser and saline infusion | 0 | None reported | |||

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Wang and Kain21 | 50 | 7–16 | 50 | Acupuncture at P6 with saline IV | 0 | None reported |

| 49 | 49 | Droperidol IV with sham acupuncture | 0 | None reported | |||

| 45 | 45 | Saline IV with sham acupuncture | 0 | None reported | |||

| 43 | 43 | Saline IV with sham point injections | 0 | None reported | |||

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Rusy et al22 | 40 | 4–18 | 40 | Electroacupuncture | 0 | None reported |

| 40 | 40 | Sham electroacupuncture | 0 | None reported | |||

| 40 | NA | No acupuncture | 0 | None reported | |||

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Somri et al23 | 30 | 4–12 | 30 | Acupuncture | 1 | Unscheduled overnight hospital admission |

| 30 | NA | IV ondansetron | NA | 1 patient required Unscheduled overnight hospital admission | |||

| 30 | NA | IV saline | NA | 2 patients stayed in the hospital over night and 1 readmitted to the hospital | |||

| Postoperative induced nausea and vomiting | Shenkman et al24 | 47 | 2–12 | 47 | Acupressure/acupuncture | 10 | Puncture redness/irritation |

| 53 | 53 | Sham acupressure/acupuncture | 8 | 8 puncture Redness | |||

| Postoperative induced vomiting | Schlager et al25 | 20 | 3–12 | 40 | Laser acupuncture | 0 | None reported |

| 20 | 40 | Sham laser acupuncture | 0 | None reported | |||

| Seasonal allergic rhinitis | Ng et al27 | 32 | 6≤ | 512 | Acupuncture | 3 | Numbness at acupuncture site |

| 1 | Headache | ||||||

| 1 | Light headedness | ||||||

| 31 | 496 | Sham acupuncture | 2 | Numbness at acupuncture site | |||

| 2 | Light headedness | ||||||

| Nocturnal enuresis | Radmayr et al36 | 20 | 5–16 | 249 | Laser acupuncture | 0 | No side effects |

| 20 | 0 | Desmopressin alone | 0 | No side effects | |||

| Total acupuncture/Sham Acupuncture Related | 1865.00 | 29.00 |

A total of 782 patients were treated with ages ranging from 2–18 years. IV indicates intravenous; NA, not available.

TABLE 3.

Estimates Calculated From Reviewed Pediatric Adverse Events Data in Table 2

| Pediatric Adverse Events Estimates | |

|---|---|

| Total pediatric adverse events | 29 |

| Total treatments | 1865 |

| Adverse event incident rate | 1.55/100 treatments |

| Acupuncture related adverse events | 0 |

| Total pediatric serious adverse events reviewed | 1 |

| Total serious adverse event incident rate | 5.36/10,000 treatments* |

Previously reviewed data estimates a serious adverse event rate as low as 0.05 per 10,000 treatments. The difference in values could be attributed to the nature of the study the one serious advent occurred in. The trial treated patients with acupuncture in an effort to prevent postoperative induced nausea and vomiting.18 As a result, 1 patient was admitted to the hospital and received intravenous ondaestron for emesis control; however, the identical adverse event occurred in control groups indicating acupuncture may not have directly been caused by the acupuncture regimen.

SUMMARY

Overall, we reviewed 31 different published journal articles including 23 randomized controlled clinical trials and 8 meta-analysis/systematic reviews. We found evidence of some efficacy and low risk associated with acupuncture in pediatrics. From all the conditions we reviewed, the most extensive research has looked into acupuncture’s role in managing postoperative and chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting. Postoperatively, there is far more evidence of acupuncture’s efficacy for pediatrics than for children treated with chemotherapy. Acupuncture seems to be most effective in preventing postoperative induced nausea in children. For adults, research shows that acupuncture can inhibit chemotherapy-related acute vomiting, but conclusions about its effects in pediatrics cannot be made on the basis of the available published clinical trials data to date.

Besides nausea and vomiting, research conducted in pain has yielded the most convincing results on acupuncture efficacy. Musculoskeletal and cancer-related pain commonly affects children and adults, but unfortunately mostly adult studies have been conducted thus far. Because the manifestations of pain can be different in children than in adults, data cannot be extrapolated from adult research.50 Systematic reviews have shown that existing data often lack adequate control groups and sample sizes. Vas et al,39 Alimi et al,32 and Mehling et al33 demonstrated some relief for adults treated with acupuncture, but we could not find any well-conducted randomized controlled studies that looked at pediatrics and acupuncture exclusively. Pain is often unresolved from drug therapy, thus there is a need for more studies in this setting.

For SAR, we reviewed studies conducted by Ng et al27 and Xue et al28 in children and adults, respectively. Both populations showed some relief of symptoms through acupuncture but the questions remain about treatment logistics. Additionally, there are limited indications that acupuncture may help cure children afflicted with nocturnal enuresis. Systematic reviews show that current published trials have suffered from low trial quality, including small sample sizes.34 Other areas of pediatric afflictions we reviewed that suffer from lack of research include asthma, other neurologic conditions, GI disorders, and addiction.

Acupuncture has become a dominant complementary and alternative modality in clinical practice today but its associated risk has been questioned. The National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement states “one of the advantages of acupuncture is that the incidence of adverse effects is substantially lower than that of many drugs or other accepted procedures for the same conditions.”3 A review of serious adverse events by White et al54 found the risk of a major complication occurring to have an incidence between 1:10,000 and 1:100,000 which is considered “very low.”55,56 Another study found that the risk of a serious adverse event occurring from acupuncture therapy is the same as taking penicillin.11 The safety of acupuncture is a serious concern, particularly in pediatrics. Because acupuncture’s mechanism is not known, the use of needles in children becomes questionable. For example, acupoints on the vertex of infants should not be needled when the fontanel is not closed. It is also advisable to apply few needles or delay treatment to the children who have overeaten, are overfatigued, or are very weak. Through our review of pediatric adverse events, we found a 1.55 risk of adverse events occurring in 100 treatments of acupuncture that coincides with the low risk detailed in the studies mentioned previously. The actual risk to an individual patient is hard to determine because certain patients, such as an immunosuppressed patient, can be predisposed to an increased risk, acupuncturist’s qualifications differ, and practices vary in certain parts of the world.55 Nevertheless, it seems that acupuncture is a safe complementary/alternative medicine modality for pediatric patients on the basis of the data we reviewed.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, acupuncture is applicable to the pediatric population. There is evidence for its efficacy in postoperative symptoms management and strong potential for chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting and pain. Acupuncture also seems to be fairly well tolerated in children in that the incidence of side effects is low and mostly inconsequential. Nevertheless, parents should be cautioned to seek properly licensed practitioners who have experience in treating children.

One of the biggest hindrances of past investigations has been small sample sizes. To enlarge study populations, we suggest that increased multicenter studies should be conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of acupuncture’s use in pediatric oncology. A multicenter approach will allow for access to a broader spectrum of the pediatric population, allow parallel recruitment, and minimize site-specific biases as well. One precaution to consider when conducting multicenter trials is to ensure that protocols are standardized so method variations between sites are prevented.

Evident upon our review, there is a substantial need for further acupuncture research targeted at children. Investigations performed in adults cannot be transitively applied to children. Just as when treated with drug therapy, children respond differently to treatment. There must be investigations into the role of acupuncture that specifically focuses on pediatrics so that appropriate conclusions can be drawn.

There are conditions in which acupuncture has been proven to be effective when treating adults, but there is a clear need for further information about pediatrics. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting is one such area where promise for efficacy in children is seen. At the National Center for Complementary Alternative Medicine in collaboration with the Children’s Oncology Group, we are conducting the first ever multicenter study exploring acupuncture’s role in pediatric oncology patients. The Cochrane Collaboration review suggests that electroacupuncture is effective for reducing the incidence of acute vomiting induced by chemotherapy in adults, but questions whether these effects are similar for delayed nausea and vomiting.18 To examine whether electroacupuncture could be effective for delayed vomiting in children, we have begun recruiting pediatric patients with newly diagnosed solid tumor cancers across the United States. In a randomized, blinded design with control sham needling, a total of 52 chemotherapy-naive patients with pediatric solid tumors aged 5 to 35 years will be enrolled for 1 electroacupuncture treatment period of 7 days during the first chemotherapy cycle, followed by 1 chemotherapy cycle without acupuncture as a control. This study hypothesizes that electroacupuncture may be effective in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced delayed nausea in patients with pediatric solid tumors, resulting in improved management of delayed nausea and emesis and improvement of quality of life. It also aims at identifying potential underlying mechanisms of action, such as reduction of a state of stress, with its negative effects on the neuroendocrine immune system and quality of life. We hope that this and other studies will expand our knowledge about the role and efficacy of acupuncture in pediatrics and stimulate additional investigations in the field.

References

- 1.Aung SKH, Chen WP-D. Clinical Introduction to Medical Acupuncture. New York: Thieme; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;343:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement Online 1997 Nov 3–5; 15:1–34.

- 4.Dune LS, Shiao SY. Metaanalysis of acustimulation effects on postoperative nausea and vomiting in children. Explore (NY) 2006;2:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin YC, Lee AC, Kemper KJ, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatric pain management service: a survey. Pain Med. 2005;6:452–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moffet HH. How might acupuncture work? A systematic review of physiologic rationales from clinical trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6:25. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhond RP, Kettner N, Napadow V. Do the neural correlates of acupuncture and placebo effects differ? Pain. 2007;128:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haker E, Egekvist H, Bjerring P. Effect of sensory stimulation (acupuncture) on sympathetic and parasympathetic activities in healthy subjects. J Auton Nerv Sys. 2000;79:52–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao XD, SF XS, Lu WX. Inhibition of sympathetic nervous system by acupuncture. Acupunct Electrother Res. 1983;18:220–224. doi: 10.3727/036012983816715028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuchiya M, Sato EF, Inoue M, et al. Acupuncture enhances generation of nitric oxide and increases local circulation. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:301–307. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000230622.16367.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemper KJ, Sarah R, Silver-Highfield E, et al. On pins and needles?Pediatric pain patients’ experience with acupuncture. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 Pt 2):941–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooney D, Le TK, Hughes D, et al. A retrospective review investigating the feasibility of acupuncture as a supportive care agent in a pediatric oncology service. Annual Meeting of the Society of Integrative Oncology; Boston, MA. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee AA, Lenti R. Treatment of children in an acupuncture setting: a survey of clinical observations. J Chin Med. 2006;82:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dundee JW, Ghaly RG, Fitzpatrick KT, et al. Acupuncture prophylaxis of cancer chemotherapy-induced sickness. J R Soc Med. 1989;82:268–271. doi: 10.1177/014107688908200508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reindl T, Geilen W, Hartmann R, et al. Acupuncture against chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric oncology. Interim results of a multicenter crossover study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:172–176. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0846-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molassiotis A, Helin AM, Dabbour R, et al. The effects of P6 acupressure in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting in breast cancer patients. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen J, Wenger N, Glaspy J, et al. Electroacupuncture for control of myeloablative chemotherapy-induced emesis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:2755–2761. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A, et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD002285. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streitberger K, Diefenbacher M, Bauer A, et al. Acupuncture compared to placebo-acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis: a randomised placebo-controlled patient and observer blind trial. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butkovic D, Toljan S, Matolic M, et al. Comparison of laser acupuncture and metoclopramide in PONV prevention in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:37–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SM, Kain ZN. P6 acupoint injections are as effective as droperidol in controlling early postoperative nausea and vomiting in children. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:359–366. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200208000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rusy LM, Hoffman GM, Weisman SJ. Electroacupuncture prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting following pediatric tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:300–305. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somri M, Vaida SJ, Sabo E, et al. Acupuncture versus ondansetron in the prevention of postoperative vomiting. A study of children undergoing dental surgery. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:927–932. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenkman Z, Holzman RS, Kim C, et al. Acupressure-acupuncture antiemetic prophylaxis in children undergoing tonsillectomy. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1311–1316. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlager A, Offer T, Baldissera I. Laser stimulation of acupuncture point P6 reduces postoperative vomiting in children undergoing strabismus surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:529–532. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarney RW, Brinkhaus B, Lasserson TJ, et al. Acupuncture for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD000008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000008.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng DK, Chow P, Ming S, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acupuncture for the treatment of childhood persistent allergic rhinitis. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5 Part 1):1242–1247. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue CC, English R, Zhang JJ, et al. Effect of acupuncture in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Chin Med. 2002;30:1–11. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0200020X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheuk DK, Wong V. Acupuncture for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD005062. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005062.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diener HC, Kronfeld K, Boewing G, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:310–316. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache. 2002;42:855–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alimi D, Rubino C, Pichard-Leandri E, et al. Analgesic effect of auricular acupuncture for cancer pain: a randomized, blinded, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4120–4126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehling WE, Jacobs B, Acree M, et al. Symptom management with massage and acupuncture in postoperative cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glazener CM, Evans JH, Cheuk DK. Complementary and miscellaneous interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online: Update Software) 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bower WF, Diao M, Tang JL, et al. Acupuncture for nocturnal enuresis in children: a systematic review and exploration of rationale. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:267–272. doi: 10.1002/nau.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Radmayr C, Schlager A, Studen M, et al. Prospective randomized trial using laser acupuncture versus desmopressin in the treatment of nocturnal enuresis. Eur Urol. 2001;40:201–205. doi: 10.1159/000049773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim B, Manheimer E, Lao L, et al. Acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD005111. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005111.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forbes A, Jackson S, Walter C, et al. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4040–4044. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i26.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Mendez C, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for chronic uncomplicated neck pain: a randomised controlled study. Pain. 2006;126:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Thorpe L, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a short course of traditional acupuncture compared with usual care for persistent non-specific low back pain. BMJ. 2006;333:623. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38878.907361.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Margolin A, Kleber HD, Avants SK, et al. Acupuncture for the treatment of cocaine addiction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:55–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kunz S, Schulz M, Lewitzky M, et al. Ear acupuncture for alcohol withdrawal in comparison with aromatherapy: a randomized-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:436–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee A, Done ML. Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD003281. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kemper KJ, McLellan MC, Highfield ES. Massage therapy and acupuncture for children with chronic pulmonary disease. Clin Pulm Med. 2004;11:242–250. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi T. Acupuncture for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:408–417. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broide E, Pintov S, Portnoy S, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for treatment of childhood constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1270–1275. doi: 10.1023/a:1010619530548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joos S, Wildau N, Kohnen R, et al. Acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1056–1063. doi: 10.1080/00365520600580688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mertz HR. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2136–2146. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C, et al. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12:639–648. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suresh S. Chronic and cancer pain management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2004;17:253–259. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith LA, Oldman AD, McQuay HJ, et al. Teasing apart quality and validity in systematic reviews: an example from acupuncture trials in chronic neck and back pain. Pain. 2000;86:119–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furlan AD, van Tulder M, Cherkin D, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2005;30:944–963. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158941.21571.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;82:263–274. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White AR, Rampes H, Campbell JL. Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD000009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000009.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White A. A cumulative review of the range and incidence of significant adverse events associated with acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2004;22:122–133. doi: 10.1136/aim.22.3.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacPherson H. Fatal and adverse events from acupuncture: allegation, evidence, and the implications. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5:47–56. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]