Abstract

To study T cell responses to tumors in an autochthonous model, we expressed a CD8 T cell epitope SIYRYYGL (SIY) in the prostate of transgenic adenocarcinoma (TRAMP) mice (referred to as TRP-SIY), which spontaneously develop prostate cancer. Naïve SIY-specific CD8 T cells adoptively transferred into TRP-SIY mice became tolerized in the prostate draining lymph nodes. Vaccination of TRP-SIY mice intranasally with influenza virus that expresses the SIY epitope resulted in generation of SIY-specific effector T cells in the lung-draining lymph nodes. These effector T cells expressed TNFα and IFNγ, eliminated SIY peptide-loaded target cells in vivo, and infiltrated prostate tumors, where they rapidly lost the ability to produce effector cytokines. A population of these T cells persisted in prostate tumors but not in lymphoid organs and could be induced to re-express effector functions following cytokine treatment in vitro. These findings suggest that T cells of a given clone can be activated and tolerized simultaneously in different microenvironments of the same host and that effector T cells are rapidly tolerized in the tumors. Our model provides a system to study T cell-tumor interactions in detail and to test the efficacy of cancer immunotherapeutic strategies.

Keywords: immunotherapy, influenza virus, T cell tolerance

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are the principal immune cells that mediate antigen-specific lysis of target cells. Directing CTLs toward malignant cells to achieve immune eradication of tumors is a major aim of cancer immunotherapy (1, 2). The antigens recognized on target cells by CTLs are “pepMHC” complexes, i.e., short peptides bound to protein products of class I major histocompatibility (MHC) genes. Many tumor cells display pepMHC that are either unique or highly tissue-restricted (3, 4), and CTL responses against them could potentially yield therapeutic benefit without causing collateral damage to normal host tissues.

Although tumor-specific T cells have been detected in cancer patients (5), tumor regression as a result of spontaneous anti-tumor immune responses is rare. The lack of effective response is often due to T cells not recognizing tumor-specific antigens (ignorance) or not responding to them (tolerance) (6, 7). Like most tissue pepMHC antigens, tumor antigens are cross-presented by specialized antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells. But, presentation of tumor antigen does not generally trigger productive responses of naïve T cells, due to a lack of co-stimulatory signals (8–10).

Current immunotherapeutic strategies focus mainly on enhancing in vivo T cell priming or adoptive transfer of in vitro activated T cells. Promising results have been obtained in many animal models using these approaches, but they have rarely led to objective and durable anti-tumor effects in cancer patients (11–14). Most studies in animals use transplantable tumors, which differ in many ways from spontaneously developed (autochthonous) tumors in patients (13–15). In recent years, however, increasing numbers of spontaneous tumor models have been developed through genetic modification of the mouse germline (16–18). Unlike transplantable tumors, spontaneous tumors in these mouse models, like those in humans, are mostly refractory to immune rejection with current strategies (19). This is often because the interactions of antigenic tumors and T cells lead to T cell tolerance.

To better understand tumor-T cell interactions and thereby identify key intervention points to improve CTL-mediated immunotherapy, we modeled CTL recognition of prostate cancer in a spontaneous tumor setting. Prostate cancer is an attractive target for immunotherapy due to the expression of many tissue-restricted proteins by the cancer cells and the expendable nature of nonmalignant tissues that share these antigens (20). By introducing a nominal CD8 T cell epitope into a spontaneous mouse prostate cancer model, we investigated CTL responses to tumor antigens at different T cell functional stages. Our results show that naïve antigen-specific T cells can be either activated or tolerized simultaneously in the same host, depending on the microenvironment in which the epitope is presented. Effector T cells generated in lymph nodes are tolerized rapidly when they infiltrate antigen-expressing tumor tissues. Interestingly, tolerant T cells persist only in the tumors and resemble tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) seen in cancer patients (21).

Results

Naïve CD8 T Cells Are Tolerized by Cross-Presented Prostate Antigen.

To investigate CD8 T cell responses to prostate cancer, we developed transgenic mice that express in the prostate a nominal antigen that can be recognized by CD8 T cells expressing the 2C T cell receptor (TCR) (22). The transgene, which encodes the SIYRYYGL (SIY) peptide fused to β-galactosidase, was placed under a composite minimum probasin (PB) promoter that drives prostate-specific gene expression [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A] (23). In one of the transgenic lines, termed PB-SIY, the transgene transcript was detected by RT-PCR in all prostate lobes, testis, and seminal vesicles, but not in other tissues (Fig. S1B). Transgene expression at the protein level was detected by X-gal staining of the prostate lobes (Fig. S1 C and D). In the testis, the transgene's transcript was abundant but its protein product was not detected by X-gal staining.

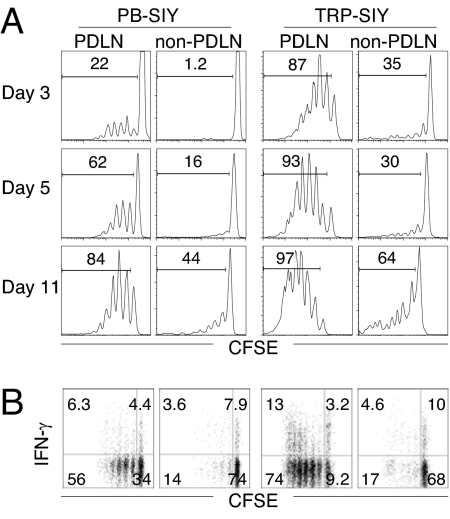

PB-SIY mice were crossed with transgenic adenocarcinoma (TRAMP) mice (17) to generate double transgenic mice, termed TRP-SIY. CD8 T cell responses to the SIY epitope in the prostate were examined by adoptive transfer of carboxyfluoroscein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled naïve 2C T cells into PB-SIY and TRP-SIY mice. Significant 2C T cell proliferation occurred in the prostate draining lymph nodes (PDLNs) of both recipients but not in non-draining lymph nodes (Fig. 1A), consistent with prostate-specific SIY expression. 2C cell proliferation was significantly faster and more extensive in TRP-SIY mice than in PB-SIY mice, most likely due to more abundant SIY epitope in the former as a result of prostate neoplasia. Despite the apparent robust proliferative response, the majority of the proliferating 2C cells failed to acquire the ability to express IFNγ (Fig. 1B). Four weeks after transfer, 2C cells were detected by flow cytometry in the PDLNs but not in other lymph nodes (data not shown). These results suggest that upon encountering cross-presented SIY in the PDLNs, 2C T cells are partially activated and then tolerized.

Fig. 1.

Response of naïve CD8 T cells to cross-presented prostate antigen. CFSE-labeled naïve 2C cells were transferred into PB-SIY or TRP-SIY mice (3 × 106/mouse). (A) Lymph node cells were harvested at the indicated days after transfer and analyzed for 2C TCR, CD8, and CFSE. CFSE intensities of 2C TCR+CD8+ cells are shown. (B) Lymph node cells (5 dpi) were stimulated with 1 μM SIY peptide for 4 h and analyzed for 2C TCR, CD8, and intracellular IFNγ. CFSE versus IFNγ profiles are shown for 2C TCR+CD8+ cells. Non-PDLN contains pooled cells from inguinal, maxillary, cervical, and mesenteric lymph nodes. The numbers indicate percentages of cells in the gated areas. Representative data from 1 of 3 experiments are shown.

Virus Infection Activates Naïve CD8 T Cells in TRP-SIY Mice.

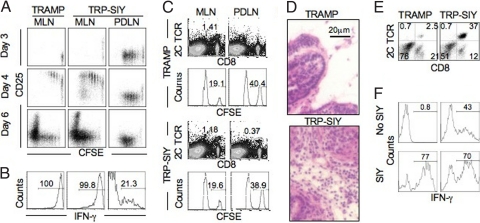

Because strong CD8 T cell responses are generally elicited by virus infection, we challenged TRP-SIY mice at the time of 2C cell transfer with an influenza strain that had been engineered to express the SIY epitope (WSN-SIY) (24). In mediastinal lymph nodes (MLNs) that drained the infected lung, 2C cells upregulated CD25 (Fig. 2A) and downregulated CD62L (Fig. S2); these cells also proliferated vigorously starting 4 days postinfection (dpi), and by 6 dpi had proliferated so extensively that CSFE stain was almost completely lost. In contrast, the 2C cells in PDLNs of the same virus-infected mice proliferated significantly 3 days after cell transfer but their proliferation was limited, and they did not upregulate CD25 or downregulate CD62L. The difference in IFNγ response was striking: in response to the virus infection, all 2C cells from the MLNs of both TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice expressed high levels of IFNγ, whereas only approximately 20% of 2C cells from PDLNs of the TRP-SIY mice expressed IFNγ and at low levels (Fig. 2B). Consistently, 2C cells lysed SIY-pulsed CFSEhi target cells in the MLNs of both TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice, whereas 2C cells in PDLNs of TRP-SIY mice did not (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that 2C cells in MLNs are strongly activated by influenza infection, whereas in the same mice the 2C cells that encounter the prostate antigen in PDLNs are tolerized.

Fig. 2.

Functional activation of 2C T cells in TRP-SIY mice by influenza vaccination. TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice were intranasally infected with WSN-SIY at the time of adoptive transfer of naïve 2C cells or CFSE labeled naïve 2C cells (1–1.5 × 106/mouse). (A) On the indicated days after infection, cells from MLNs and PDLNs were analyzed for 2C TCR, CD8, and CD25. CFSE versus CD25 profiles are shown for 2C TCR+CD8+ cells. (B) 5 dpi, cells from MLNs and PDLNs were stimulated with SIY peptide for 4 h and analyzed for 2C TCR, CD8, and IFNγ. Histograms show IFNγ expression by 2C TCR+CD8+ cells. (C) 4.5 days after 2C cell transfer and virus infection, mice were injected with target cells (a mixture of SIY peptide pulsed CFSEhi and unpulsed CFSElo B6 splenocytes, 5 × 106/mouse). 12 h later, the frequency of 2C cells, CFSEhi, and CFSElo cells were measured by flow cytometry in MLNs and PDLNs. Dot plots show 2C TCR versus CD8 staining profiles and histograms show CFSE intensities of transferred target cells. (D–F), 10 dpi, the prostate lobes were harvested. (D) hematoxylin and eosin stain of prostate sections. (E) 2C TCR versus CD8 staining profiles of total live cells in prostates. (F) IFNγ expression of Thy1.1+ CD8+ 2C cells from prostate after 4 h culture in the presence or absence of SIY peptide (1 μM). The numbers indicate the percentages of cells in the gated areas. Shown are representative data from 1 of 2 to 5 independent experiments.

Virus-Activated CD8 T Cells Infiltrate Prostate.

Without influenza challenge, 2C cells were below detection by flow cytometry in the prostate of TRAMP or TRP-SIY mice, but became detectable 7 dpi (data not shown). By day 10, large numbers of lymphocytes were present (Fig. 2D) and most of them were 2C cells (Fig. 2E). There were approximately 80 times more infiltrating 2C cells in prostates of TRP-SIY mice (4.3 × 105 ±2.6 × 105/prostate) than TRAMP mice (5.3 × 103 ±4.2 × 103/prostate), although TRAMP prostates were similarly neoplastic. Moreover, effector 2C T cells activated in the MLNs by intranasal influenza infection maintained their effector functions for at least 3 days after infiltrating SIY-expressing prostate tumors. Thus, after a brief SIY stimulation, approximately 70% of 2C cells from the prostates of both TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice produced IFNγ (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, approximately 40% of 2C cells from TRP-SIY prostates produced IFNγ during the 4 h incubation without addition of exogenous peptide, likely due to expression of the SIY epitope in the TRP-SIY prostate. 2C cells from TRAMP and TRP-SIY prostates stained similarly for intracellular granzyme B and perforin, but a significant fraction of the 2C cells from the TRP-SIY prostates expressed CD107 (evidence of degranulation) even without stimulation by exogenous peptide (data not shown).

Virus-Activated T Cells Are Tolerized in TRP-SIY Mice.

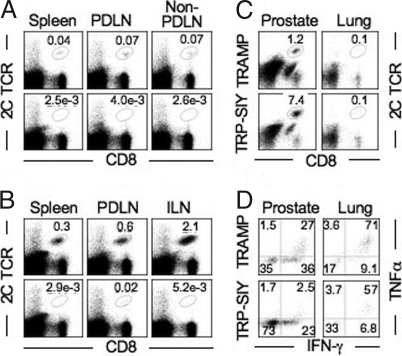

Despite extensive infiltration of effector 2C cells into the prostate, vaccinated TRP-SIY mice succumbed to prostate cancer at the same rate as non-vaccinated TRAMP or TRP-SIY mice (data not shown). Because β-gal expression was detected in tumor cells (Fig. S1D), and significantly increased 2C cell infiltration was observed in TRP-SIY prostates, immune evasion through antigen loss seemed unable to account for the lack of any observable long-term antitumor effect. More likely, the effector 2C T cells were rendered tolerant by persistent SIY expression in the tumor. In support of this notion, 4 months after influenza infection, a distinct memory 2C cell population was readily detected in the spleen and lymph nodes of TRAMP mice, whereas virtually no 2C cells were detected in the lymphoid organs of TRP-SIY mice (Fig. 3A). To exclude the possibility that TRP-SIY mice only developed a quantitatively smaller yet functionally normal population of memory T cells that fell below the detection limit of flow cytometry, vaccinated TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice were rechallenged with SIY peptide emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant (CFA). Five days later, memory 2C T cells expanded dramatically in TRAMP mice, with the largest expansion (approximately 30-fold) in the inguinal lymph nodes that drain the injection site (Fig. 3B). In contrast, 2C cells remained barely detectable in most lymphoid organs of rechallenged TRP-SIY mice, except PDLNs, where very small numbers of 2C cells were detected in some mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Induction of tolerance in TRP-SIY mice after influenza vaccination. TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice were transferred with 2C cells, challenged with WSN-SIY as in Fig. 2 and analyzed 4 month later. (A) 2C TCR versus CD8 staining profiles of live cells from various lymphoid tissues. Non-PDLN contains pooled cells as in Fig. 1. (B) mice were injected s.c. with 50 μg of SIY peptide emulsified in CFA and analyzed 5 days later. 2C TCR and CD8 staining profiles are shown for all live cells. (C) 2C TCR versus CD8 staining profiles of live cells from prostate and lung. (D) TNFα versus IFNγ staining profiles of the 2C TCR+CD8+ cells from prostate and lung after stimulation with SIY for 4 h. The numbers indicate the percentages of cells in the gated areas. Representative data from 1 of 3 experiments are shown.

In contrast to their absence in lymphoid organs, significant numbers of 2C cells were detected within the prostate tumors of vaccinated TRP-SIY mice throughout the rest of their lives (Fig. 3C). Four months after initial 2C cell transfer and virus infection, 2C cells were ≈10 times more abundant in TRP-SIY prostates than TRAMP prostates [(2.4 ±1.3) x104 versus (2.9 ±1.5) x103, P < 0.05]. A small number of 2C T cells were also found in the lungs. Upon SIY stimulation in vitro, approximately 60% of 2C cells from the lung but only approximately 3% of the 2C cells from the prostate of TRP-SIY mice expressed both TNFα and IFNγ, whereas approximately 70% of persisting 2C cells from the lungs and approximately 25% from the prostate of TRAMP mice expressed both cytokines (Fig. 3D). Although approximately 25% of prostate 2C cells from TRP-SIY mice produced IFNγ alone, the level was significant lower than that produced by 2C cells from the lung. 2C cells in prostates of TRP-SIY mice expressed an elevated level of PD-1 (Fig. S3) and did not significantly increase in number when the mice were injected with SIY peptide plus CFA (data not shown). Notably, there was a gradual loss in cytokine production by 2C cells from the prostate of TRAMP mice, probably due to tumor-mediated immune suppression. Together, these results suggest that following influenza vaccination of TRP-SIY mice 2C cells do not persist in lymphoid organs and the 2C cells that persist in the prostate are functionally tolerant.

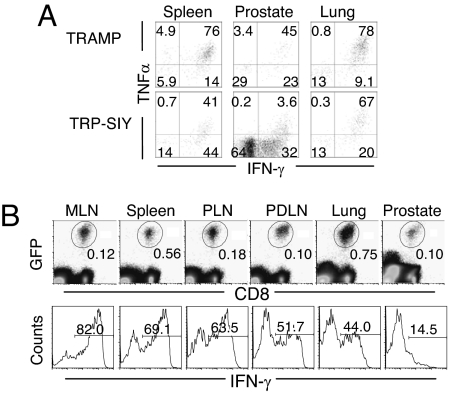

How rapidly are effector T cells tolerized in TRP-SIY prostate? To answer the question, we assayed cytokine expression by 2C cells from different organs at 14 dpi. In TRAMP mice, approximately 75% of 2C cells from the lung and spleen and 45% of 2C cells from the prostate expressed both TNFα and IFNγ (Fig. 4A). In TRP-SIY mice, although approximately 70% of the 2C cells in the lung expressed both TNFα and IFNγ, the percentages were decreased to approximately 40% in the spleen and to only approximately 4% in the prostate. The ability of 2C cells from the TRP-SIY prostate to express TNFα and IFNγ was lost by 14 dpi and between 7–28 dpi, respectively (Fig. S4). Because activated 2C cells do not start to infiltrate the prostate until 7 dpi and maintain their effector function for the first 3 days after infiltration (Fig. 2F), these results suggest that the tolerization of effector 2C T cells in the prostate is a rapid process.

Fig. 4.

Rapid tolerization of effector 2C cells in the prostate of TRP-SIY mice. (A) TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice were injected with naïve 2C cells and infected with WSN-SIY as in Fig. 2. Fourteen days later, cells from various tissues were incubated with SIY peptide and analyzed for cytokine expression. TNFα versus IFNγ staining profiles are shown for Thy1.1+CD8+ 2C cells. (B) 1.5 × 106 naïve GFP+ 2C cells were transferred into B6 mice and immediately infected with WSN-SIY. Five days later, 20 × 106 MLN cells were transferred into TRP-SIY mice that had been infected with WSN-SIY 5 days earlier. Five days after effector cell transfer, lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues were harvested, and recovered cells were analyzed for IFNγ expression after a brief SIY stimulation. Dot plots show GFP versus CD8 profiles to identify 2C cells. Histograms show IFNγ expression of the 2C cells pooled from 3 TRP-SIY mice. The numbers indicate percentages of 2C cells in the gated areas. Data shown are representative of 1 of 3 similar experiments.

Naïve 2C cells are tolerized in the PDLNs during the course of virus-induced activation of the 2C cells in MLNs of TRP-SIY mice. Although the tolerized 2C cells in PDLNs do not infiltrate the prostate, they complicate our interpretations of tolerance of effector 2C cells in the tumors. To address this issue, we examined directly the fate of effector 2C cells transferred into TRP-SIY mice. For this purpose, the effector cells were generated by injecting naïve 2C cells into C57BL/6 (B6) mice and infecting them with WSN-SIY; then, 5 dpi, 20 × 106 MLN cells (containing approximately 1 × 106 2C cells) were transferred into TRP-SIY mice which have been infected with WSN-SIY intranasally 5 days earlier (but without transfer of naive 2C cells). Five days post effector cell transfer, 2C cells from various organs were assayed for IFNγ expression after SIY stimulation. While approximately 45–80% of the 2C cells from the spleen, lung and various lymph nodes expressed IFNγ, only approximately 15% of 2C cells from the prostate were weakly positive for IFNγ (Fig. 4B), further supporting the rapid tolerization of effector 2C cells in the prostate of TRP-SIY mice.

Tumor-Tolerized T Cells Can Regain the Ability to Produce Cytokines in Vitro.

To determine whether tolerized 2C cells can recover function, the persisting tolerant 2C cells from prostates of TRP-SIY mice were purified by cell sorting, labeled with CFSE and transferred into naïve B6 recipients. As controls, 2C cells from the liver of TRAMP mice were similarly purified and transferred. The prostate-derived tolerant 2C cells survived and underwent as much homeostatic proliferation in the liver of naïve B6 recipients as did the control liver-derived 2C cells (Fig. 5A). When recipient mice were challenged with WSN-SIY i.p. 7 days after transfer, 30–50-fold more 2C cells were recovered from the spleens and the livers of recipient mice that had initially received 2C cells from TRAMP livers (Fig. 5B). However, only approximately 10 and 2-fold more 2C cells were recovered, respectively, from the spleens and the livers of recipient mice that had received tolerant 2C cells from TRP-SIY prostates.

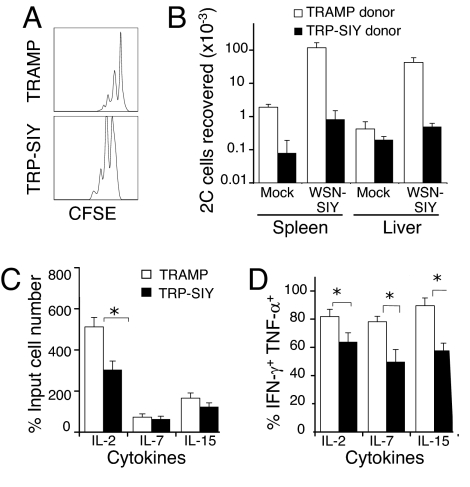

Fig. 5.

Responses of tolerant 2C cells in vivo and in vitro. TRAMP and TRP-SIY mice (Thy1.2+) were injected with naïve 2C cells (Thy1.1+) and infected with WSN-SIY. 28 dpi, Thy1.1+CD8+ 2C cells from the prostate of TRP-SIY mice or the liver of TRAMP mice were purified by cell sorting and labeled with CFSE. (A and B), Purified and labeled 2C cells were transferred into naïve B6 mice (Thy1.2+, 1 × 105/mouse) and 7 days later half of the recipients mice were infected with WSN-SIY i.p. or mock injected with PBS. Six days after infection (or 13 days after 2C cell transfer to the secondary hosts) spleen and liver from all mice were analyzed for cell number, Thy1.1, CD8, and CFSE. (A) CFSE profiles of Thy1.1+CD8+ 2C cells from liver of non-infected recipient B6 mice. (B) The total number of Thy1.1+CD8+ 2C cells in both spleen and liver of recipient B6 mice with or without WSN-SIY infection. (C and D) Purified and CFSE-labeled 2C cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2, IL-7 or IL-15 for 4 days and cells were enumerated. Some cells were stimulated with SIY peptide for 4 h and assayed for IFNγ and TNFα. (C) Cell numbers after culture normalized to the initial input cell numbers. (D) Percentages of IFNγ and TNFα-expressing 2C cells in various cultures. *, P < 0.05. Representative data from one of two independent experiments are shown.

Purified, CFSE-labeled 2C cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2, IL-7, or IL-15. During a 4-day culture, the 2C cells from TRAMP liver expanded 5-fold in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 5C). Although they also proliferated in the IL-15 culture, as indicated by CFSE dilution (data not shown), the total cell number increased only slightly. In the IL-7 culture, the cells survived but did not proliferate. The tolerant T cells from TRP-SIY prostate also proliferated in the IL-2 culture but did not undergo significant expansion in the presence of either IL-15 or IL-7. However, tolerant 2C cells cultured with each of the three cytokines significantly regained the ability to produce both IFNγ and TNFα (compare Fig. 5D with Fig. 3D and Fig. 4A), although the percentages were not as high as with 2C cells from TRAMP liver. These results suggest that under certain conditions, tolerant T cells can be induced to proliferate and secrete effector cytokines.

Discussion

Given the limited clinical responses to current immunotherapies, there is a widely recognized need for improved models to study T cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Here we developed a transgenic mouse line which, when combined with the TRAMP model, allows for detailed characterization of the functional status of tumor-specific CTLs. In our model, expression of the nominal CD8 T cell epitope (SIY) is restricted to the prostate. Consistent with previous transgenic studies, the transgenic antigen (SIY-Kb) in the prostate behaves like a self antigen and induces a non-productive response by the adoptively transferred cognate naïve 2C T cells (25–27). Although cross presentation of the tumor-derived antigen in TRP-SIY mice induced more extensive T cell proliferation than the non-tumor tissue antigen in PB-SIY mice, probably due to the greater abundance of the epitope as a result of prostate neoplasia, the proliferating 2C cells did not upregulate activation markers, acquire the ability to produce IFNγ or infiltrate the prostate (Fig. 1). Eventually, most 2C cells disappeared from recipient mice, except for small numbers in the PDLNs, suggesting systemic tolerance. Importantly, in our model the adoptively transferred naïve T cells could be activated to differentiate into effector CTLs in MLNs following influenza infection. The effector T cells infiltrated the prostate tumors, where they rapidly became tolerized, but then persisted for long periods. This is consistent with a previous report that tolerized T antigen-specific T cells persist in TRAMP prostates (28). Thus, in combining transgenic antigen expression in the prostate with a ready source of naïve or effector T cells that recognize that antigen and influenza virus-mediated antigen-specific vaccination, the model described here provides a promising system for studying T cell response, tolerance, and reactivation to prostate tumor, and for testing novel approaches for adoptive T cell therapy of cancer.

Current adoptive immunotherapies of cancer often use effector T cells that have been generated in vitro. The effectiveness of this approach is limited by the poor persistence and rapid tolerization of transferred T cells in the recipients (29). It is possible that T cells activated in vitro are not programmed to adapt to an in vivo environment that differs in cytokines and helper cell support. In contrast, T cells activated in vivo, especially in the context of virus infection, generate highly potent effector cells, some of which can persist as robust memory T cell populations. Our findings firmly establish that in the TRP-SIY model, naïve 2C cells become effectively primed and fully activated in the MLNs, while independently becoming tolerized in the PDLNs. The early activation phenotype of 2C cells in MLNs of influenza infected TRP-SIY mice is indistinguishable from that in hosts that do not carry the SIY transgene. The virus-activated 2C cells acquire a full range of effector functions, such as IFNγ production and cytolytic activity. In addition, they are able to infiltrate extensively into the antigen-expressing prostate tumor tissue and express IFNγ in the tumor tissue for at least 3 days (Fig. 2).

Despite the induction of robust effector functions in tumor-specific T cells by virus infection, a profound tolerant state eventually prevails in the vaccinated TRP-SIY mice. Our analysis reveals systemic tolerance by deletion of tumor-specific T cells in the peripheral lymphoid organs and functional tolerization of persisting T cells in the antigen expressing tumors (Fig. 3). Adoptively transferred effector T cells (generated by virus infection of donor mice) are also rapidly tolerized in the prostate tumors of TRP-SIY recipients (Fig. 4). While tolerization of naïve T cells has been extensively studied, the mechanisms by which effector T cells are tolerized are not well understood. Our study shows that the tolerized effector T cells have a profound defect in TNFα production; but some of these cells retained low levels of IFNγ production, reminiscent of functionally exhausted CTLs in chronic virus infection (30). Like exhausted CD8 T cells, the tolerant 2C cells express an elevated level of PD-1 (31). When PD-1 ligand, PD-L1, was deleted in the TRP-SIY mice, however, tolerization of influenza activated 2C cells was not attenuated (data not shown). The direct demonstration that productively-activated antigen-specific effector T cells are tolerized in the tumor highlights one of the major challenges that has to be overcome for long-term immunotherapeutic responses.

TILs are found in many solid tumors in cancer patients (1, 21) and studies have suggested that their presence is associated with a favorable prognosis in some individuals (32). However, freshly isolated TILs are typically defective in their effector functions (21). In some cases, suppressor cell populations, such as regulatory T cells and certain myeloid cells as well as suppressive soluble factors such as TGF-β, are implicated in the T cell dysfunction. In other cases, the T cells appear to be inherently defective (33, 34). The molecular mechanisms underlying TIL tolerance and their persistence in the antigenic tumor microenvironment have not been well characterized. The heterogeneity of TILs in patients, as well as the lack of knowledge of the cognate tumor antigens, makes it difficult to analyze these cells in detail. In our TRP-SIY model, effector CTLs rapidly become tolerant in antigen-expressing prostate tumors without being physically deleted. Kiniwa et al. recently demonstrated the importance of CD8+Foxp3+ suppressor cells in human prostate tumors (35). However, both intracellular staining and transcriptional profiling show that tolerized 2C cells in the TRP-SIY mice are not converted into Foxp3+ suppressor cells (data not shown). Preliminary studies suggests that tolerized 2C cells do not express elevated IL-7R and IL-15R (data not shown), suggesting that increased survival cytokine signaling cannot account for their persistence either.

A long-standing interest in TILs stems from their potential therapeutic value. Numerous studies have shown that in vitro culture of TILs with cytokines can both induce potent effector function and extensive cell expansion (21). Our secondary transfer study shows that simply removing tolerant cells from the antigen-persisting environment is insufficient to fully reverse tolerance, suggesting that functional inactivation is not mediated by a dominant extrinsic suppressor. However, all three γc cytokines, regardless of their mitogenic potentials, were effective in reversing the decreased TNFα and IFNγ expression (Fig. 5). An understanding of the mechanisms of cytokine-mediated tolerance reversion and the ability to isolate TILs and restore their function in vitro may lead to new approaches to adoptive T cell cancer therapy or to reactivating tumor-specific T cells in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Virus.

The transgenic construct was assembled by ligating a composite rat probasin promoter fragment ARR2PB (a gift from Dr. R. J. Matusik of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) (23), a β-galactosidase-SIY fusion gene, and the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation sequence. The founder mice were generated on B6 background in the Rippel Transgenic Facility at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. TRAMP mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred to homozygosity. Littermates from the cross of heterozygous PB-SIY and homozygous TRAMP mice were used in all of the experiments. The RAG1−/− 2C TCR transgenic mice (2C/RAG) were maintained on B6, B6.Thy1.1, or B6.GFP+ background. All of the mice were housed in a specific pathogen free facility. Animal studies were carried out in accordance of the institutional guidelines on animal care.

Recombinant influenza A/WSN-SIY virus was constructed by inserting the SIY epitope into the stem of neuraminidase using plasmid-based reverse genetics (24). 100 and 1 × 105 pfu were used for intranasal and i.p. infection, respectively.

Adoptive Transfer and Influenza Infection.

Naïve 2C cells were isolated from the lymph nodes and spleen of 2C/RAG mice. Red blood cells (RBC) were lysed from the splenocytes. Pooled lymph node and spleen cells were resuspended in PBS or HBSS and 1–1.5 × 106 cells in 100 μl were injected retroorbitally into B6, PB-SIY, TRAMP or TRP-SIY mice. Where indicated, mice were also infected with 100 pfu WSN-SIY intranasally in 50 μl PBS immediately following adoptive transfer. For adoptive transfer of effector T cells, naïve 2C cells were transferred into B6 recipients and infected with WSN-SIY as above; 5 days after infection MLNs were harvested and 20 × 106 cells in 100 μl (containing ≈1 × 106 effector 2C cells) were injected retroorbitally into TRP-SIY mice that had been infected intranasally with 100 pfu WSN-SIY 5 days earlier. Five days after the effector cell transfer, lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues were harvested for analysis.

Cells, Antibodies, and Flow Cytometry.

Single cell suspensions from lymphoid tissues were prepared. Prostate tissues were microdissected and digested with 2 μg/ml collagenase A (Roche) in RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS for 1 h at 37 °C. Samples were then minced between frosted glass slides and filtered with a 70 μm nylon mesh. For the lungs and liver, perfusion was performed with cold PBS. Lung samples were ground through a metal cell strainer, RBCs were lysed, and cells were filtered with a nylon mesh. Ground liver samples were digested with collagenase A and DNase I (0.2 mg/ml, Sigma), and separated on 35% and 65% discontinuous percoll gradients before lysis of RBC and nylon mesh filtration.

Antibodies to CD8, Thy1.1, CD25, CD62L, IFNγ, and TNFα (BD Bioscences) were conjugates to FITC, PE, APC, or PerCP-Cy5.5. 2C TCR was detected using clonotypic antibody 1B2 conjugated with biotin. 2C cells were identified with an anti-CD8 antibody plus 1B2, anti-Thy1.1, or GFP. Stained cell samples were evaluated using a FACSCaliburTM (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed using FlowJoTM software (Tree Star).

For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were restimulated with 1 μM SIY for 4 h in the presence of 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma). Surface staining was followed by cell fixation with cytofix/cytoperm buffer (BD Biosciences) and staining with antibodies specific for IFNγ (XMG1.2) and TNFα (MP6-XT22). IFNγ recapture assay was carried out using the mouse IFNγ secretion assay detection kit (Miltenyi Biotech). Cells from lymphoid organs were stimulated directly with 1 μg/ml SIY for 4 h at 37 °C in RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS. Cells from non-lymphoid organs were mixed at a 1:1 ratio with syngeneic splenocytes and then stimulated. Following stimulation, cells were incubated with the IFNγ“catch” reagent at 37 °C for 45 min. Cells were then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry.

In Vivo Cytotoxicity Assay.

Syngeneic B6 splenocytes were labeled for 10 min at room temperature with either 5 μM CFSE (CFSEhi) or 0.5 μM CFSE (CFSElo) in PBS with 0.1% BSA. After washing, CFSEhi cells were pulsed with 1 μg/ml SIY peptide for 1 h at 37 °C, while the CFSElo cells were left unpulsed. CFSEhi and CFSElo cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and injected retroorbitally into mice (5 × 106/mouse). 12 h later, the ratio of CFSEhi to CFSElo cells in lymphoid organs was evaluated by flow cytometry .

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. R. J. Matusik (Vanderbilt University) for providing the composite probasin promoter, and members of the Chen lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by NIH grants CA100875 and AI50631 and Koch Research Fund (to J.C.), CA96504 (to D.W.). A.B. was partly supported by a Margaret A. Cunningham Immune Mechanisms in Cancer Research Fellowship and postdoctoral fellowships from the Sorono Foundation and National Institutes of Health. E.H. was partly supported by a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See Commentary on page 12643.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0805599105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive-cell-transfer therapy for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:666–675. doi: 10.1038/nrc1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattman JN, Greenberg PD. Cancer immunotherapy: A treatment for the masses. Science. 2004;305:200–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevanovic S. Identification of tumour-associated T-cell epitopes for vaccine development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:514–520. doi: 10.1038/nrc841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, Chen YT, Old LJ. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:615–625. doi: 10.1038/nrc1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee PP, et al. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat Med. 1999;5:677–685. doi: 10.1038/9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ochsenbein AF, et al. Immune surveillance against a solid tumor fails because of immunological ignorance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2233–2238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiotto MT, Fu YX, Schreiber H. Tumor immunity meets autoimmunity: Antigen levels and dendritic cell maturation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:725–730. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochsenbein AF, et al. Roles of tumour localization, second signals and cross priming in cytotoxic T-cell induction. Nature. 2001;411:1058–1064. doi: 10.1038/35082583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heath WR, Carbone FR. Cross-presentation, dendritic cells, tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:47–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyman MA, Aung S, Biggs JA, Sherman LA. A spontaneously arising pancreatic tumor does not promote the differentiation of naive CD8+ T lymphocytes into effector CTL. J Immunol. 2004;172:6558–6567. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison JP, Hurwitz AA, Leach DR. Manipulation of costimulatory signals to enhance antitumor T-cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:682–686. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: Moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiotto MT, et al. Increasing tumor antigen expression overcomes “ignorance” to solid tumors via crosspresentation by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Immunity. 2002;17:737–747. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai XF, et al. Local costimulation reinvigorates tumor-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes for experimental therapy in mice with large tumor burdens. J Immunol. 2001;167:3936–3943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Animal models of tumor immunity, immunotherapy and cancer vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dyke T, Jacks T. Cancer modeling in the modern era: Progress and challenges. Cell. 2002;108:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg NM, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3439–3443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willimsky G, Blankenstein T. Sporadic immunogenic tumours avoid destruction by inducing T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2005;437:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature03954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blankenstein T. Do autochthonous tumors interfere with effector T cell responses? Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karnes RJ, Whelan CM, Kwon ED. Immunotherapy for prostate cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:807–817. doi: 10.2174/138161206776056001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteside TL, Parmiani G. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: Their phenotype, functions and clinical use. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;39:15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01517175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Eisen HN, Kranz DM. A model T-cell receptor system for studying memory T-cell development. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Thomas TZ, Kasper S, Matusik RJ. A small composite probasin promoter confers high levels of prostate-specific gene expression through regulation by androgens and glucocorticoids in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4698–4710. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen CH, et al. Loss of IL-7R and IL-15R expression is associated with disappearance of memory T cells in respiratory tract following influenza infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:171–178. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drake CG, et al. Androgen ablation mitigates tolerance to a prostate/prostate cancer-restricted antigen. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lees JR, et al. Deletion is neither sufficient nor necessary for the induction of peripheral tolerance in mature CD8+ T cells. Immunology. 2006;117:248–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng X, Yin L, Liu Y, Zheng P. Expression of tissue-specific autoantigens in the hematopoietic cells leads to activation-induced cell death of autoreactive T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3126–3134. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson MJ, Shafer-Weaver K, Greenberg NM, Hurwitz AA. Tolerization of tumor-specific T cells despite efficient initial priming in a primary murine model of prostate cancer. J Immunol. 2007;178:1268–1276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leen AM, Rooney CM, Foster AE. Improving T cell therapy for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. 2003;77:4911–4927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber DL, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clemente CG, et al. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang HY, Wang RF. Regulatory T cells and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen ML, et al. Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-beta signals in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiniwa Y, et al. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells mediate immunosuppression in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6947–6958. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.