Abstract

Although previous studies report a reduction in myocardial volume during systole, myocardial volume changes during the cardiac cycle have not been quantitatively analyzed with high spatiotemporal resolution. We studied the time course of myocardial volume in the anterior mid-left ventricular (LV) wall of normal canine heart in vivo (n = 14) during atrial or LV pacing using transmurally implanted markers and biplane cineradiography (8 ms/frame). During atrial pacing, there was a significant transmural gradient in maximum volume decrease (4.1, 6.8, and 10.3% at subepi, midwall, and subendo layer, respectively, P = 0.002). The rate of myocardial volume increase during diastole was 4.7 ± 5.8, 6.8 ± 6.1, and 10.8 ± 7.7 ml·min−1·g−1, respectively, which is substantially larger than the average myocardial blood flow in the literature measured by the microsphere method (0.7–1.3 ml·min−1·g−1). In the early activated region during LV pacing, myocardial volume began to decrease before the LV pressure upstroke. We conclude that the volume change is greater than would be estimated from the known average transmural blood flow. This implies the existence of blood-filled spaces within the myocardium, which could communicate with the ventricular lumen. Our data in the early activated region also suggest that myocardial volume change is caused not by the intramyocardial tissue pressure but by direct impingement of the contracting myocytes on the microvasculature.

Keywords: myocardial structure, ventricular pacing, mechanical dyssynchrony

previous studies report systolic reduction in myocardial volume (13, 15, 25, 28, 29, 35, 43), which has been explained as a result of blood that is squeezed out of the coronary vasculature within the myocardium. The changes in myocardial volume during the cardiac cycle have not attracted much attention, primarily because the myocardial blood flow measured by microsphere techniques (0.7–1.3 ml·min−1·g−1) (16) would predict systolic myocardial volume reduction on the order of only 1% (35).

However, direct measurement of myocardial volume change during the cardiac cycle using implanted marker arrays shows a maximum systolic volume reduction of as much as 15% (43). Myocardial volume changes >1% cannot be accounted for by the change in coronary blood volume during the cardiac cycle and thus may have important implications for the structure of the myocardial wall. However, myocardial volume changes during the cardiac cycle have not been quantitatively analyzed with high spatiotemporal resolution.

In this study, we examined the time course of myocardial volume change during the cardiac cycle in the LV anterior wall of normal canine heart in vivo using transmurally implanted markers and biplane cineradiography (8 ms/frame). The measured changes in myocardial volume suggest existence of additional mechanisms besides coronary blood volume movement that regulates myocardial volume.

METHODS

All protocols were approved by the Animal Subjects Committee of the University of California, San Diego, which is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. A subset of data included in this study has been presented previously in our reports (3–5, 14) that described local ventricular deformation. The present study represents a new analysis of the original data to obtain the time course of the myocardial volume change.

Experimental protocol.

Fifteen adult mongrel dogs (20–30 kg) were anesthetized with intravenous thiopental sodium (8–10 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated with isoflurane (0.5–2.5%), nitrous oxide (3 l/min), and medical oxygen (3 l/min) to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia. To measure three-dimensional (3-D) myocardial deformation, three transmural columns of four to six 0.8-mm-diameter gold beads were placed within the LV anterior wall between the first and second diagonal branches of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery via median sternotomy (Fig. 1A). The bead placement technique using a bead insertion trocar was originally developed by Fenton et al. (17, 18) and modified by Waldman et al. (43) in this laboratory. It was further modified so that individual beads could be inserted in the myocardium at specific depths, with a typical transmural spacing of 1–2 mm (4). An 8-mm-thick Plexiglas template, with three holes drilled at the corners of a 10-mm equilateral triangle to act as guides for the bead insertion trocar, was sutured to the epicardium over the measurement region. The bead placement device was inserted individually through each of the three holes, ensuring that the columns of four to six 1-mm-diameter gold beads were implanted along an axis that was approximately perpendicular to the epicardial tangent plane. It should be noted that subsequent 3-D deformation analysis does not depend on accurate bead placement; such placement is important only to ensure that the implantation region is local, i.e., that markers are distributed across the wall and that there is no overlap of beads during contraction in either view of the biplane cineradiography. After the bead insertion was complete, the platform was removed, and a 1.7-mm-diameter surface gold bead was sewn on the epicardium above each column. Gold beads (2-mm diameter) were sutured to the apical dimple (apex bead) and on the epicardium at the bifurcation of the LAD and left circumflex coronary artery (base bead) to provide end points for a left ventricular (LV) long axis (3–5, 14). Three pairs of pacing wires were sutured to the left atrium (LA), the LV epicardial surface in the midanterior wall across the triangle of the surface gold beads, and in the midposterior wall. In all animals (n = 15), atrial pacing was performed by stimulating the LA. In 12 animals within the group, anterior LV pacing was performed by stimulating both LA and the epicardial surface of the bead set in the anterior LV to measure LV myocardial deformation in the early activated region. In seven animals within the group, posterior LV pacing was performed by stimulating both LA and posterior LV to measure LV myocardial deformation in the late-activated region. The LA-LV delay was 20–60 ms in both anterior and posterior LV pacing. All pacing protocols were conducted via a square-wave, constant-voltage electronic stimulator at a frequency 10–20% above baseline heart rate to suppress native sinus rhythm, and stimulation parameters (voltage 10% above threshold, duration 8 ms, and frequency) were kept constant in each animal.

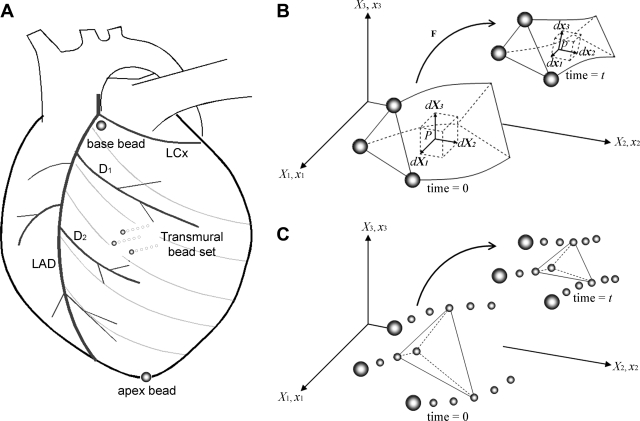

Fig. 1.

A: Experimental setup. The transmural bead set (∼10 mm) was implanted between the first (D1) and the second (D2) diagonal branch of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery to measure three-dimensional (3-D) displacement of the myocardial tissue across the wall. To provide end points for a left ventricular (LV) long axis, 2-mm-diameter gold beads were sutured to the apical dimple (apex bead) and on the epicardium at the bifurcation of the LAD and left circumflex (LCx) coronary arteries (base bead). B: calculation of myocardial volume change within the bead set using finite deformation. Myocardial volume change can be calculated in an infinitesimal volume element at an arbitrary wall depth in the deformed configuration (dx1, dx2, dx3, time = t) relative to the reference configuration (dX1, dX2, dX3, time = 0). See text for details. Modified from Bonet and Wood (9). C: calculation of myocardial volume change using individual tetrahedra created by intramyocardial beads. To validate myocardial volume calculation using finite deformation, we also calculated myocardial volume change within individual tetrahedra created by intramyocardial beads. Geometrical change of one representative tetrahedron from time = 0 to time = t is schematically shown.

Each animal was positioned in a biplane radiography system, and synchronous biplane cineradiographic images (temporal resolution = 8 ms) of the bead markers were digitally acquired with mechanical ventilation suspended at end expiration. Left ventricular pressure, central aortic pressure, LA pressure, and surface electrocardiograms (ECG) were recorded simultaneously with the cineradiographic images. Image acquisition for each pacing mode (atrial pacing, anterior and posterior LV pacing) was performed consecutively at the same heart rate to minimize variation in hemodynamic conditions. At the end of the study, the animal was killed with pentobarbital sodium, and the heart was perfusion-fixed with 2.5% buffered glutaraldehyde at the end-diastolic pressure measured in the study (4, 47). Because the heart was fixed at end-diastolic pressure, fiber orientations in the fixed hearts were assumed to represent the fiber structure in the end-diastolic reference configuration in vivo (4).

Histology.

To avoid the distortional effects of dehydration and shrinkage associated with embedding, histologic measurements were obtained using freshly fixed heart tissue. In the transmural block of tissue within the implanted bead set, the mean myofiber angle was measured with reference to the positive circumferential direction and was determined from epicardium to endocardium at every 1-mm-thick section sliced parallel to the epicardial tangent plane (4).

Data analysis.

The digital images from biplane X-ray were corrected for magnification and spherical distortion (4) to reconstruct the 3-D coordinates (30) of the bead markers. End diastole was defined as the time of the peak of the ECG R-wave for atrial pacing and the ventricular pacing artifact (V-spike) for LV epicardial pacing. We chose the V-spike rather than the peak of R-wave as the reference state for LV epicardial pacing because the former reflects the timing of the activation of the pacing site, as opposed to the latter, which represents the timing of activation of the whole ventricle (5). The timing of aortic valve opening (AVO) and closure (AVC) and mitral valve opening (MVO) was estimated from LV, LA and central aortic pressures, so that each cardiac phase (isovolumic contraction, ejection, isovolumic relaxation, and diastolic filling) can be determined.

The time course of myocardial volume V was calculated from continuous, nonhomogeneous transmural distributions of 3-D finite deformation within the bead set for each frame as a deformed configuration with end diastole as the reference state (15). Briefly, a continuous polynomial position field that mapped the beads in the undeformed reference configuration to those in the deformed configuration was determined. In essence, the deformed position of a bead was approximated by a polynomial function of its reference position. The degrees of freedom in the polynomial position field were optimized to give the best fit of the measured bead positions relative to the approximated or fit bead positions. The order of the polynomial is at most linear in circumferential and apex-base, and the maximum order in the radial axis is typically quadratic. To eliminate oscillations in the fitting polynomial, the number of degrees of freedom was kept much smaller than the number of measurements, typically 10-fold fewer. With this continuous polynomial mapping from reference position to current position, differentiation with respect to reference position gives the 3-D deformation gradient tensor F (= a 3 × 3 matrix), which depends on position.

In an infinitesimal volume element in the reference configuration with edges parallel to the Cartesian axes given by

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

where e1, e2, and e3 are the orthogonal unit vectors (9) (Fig. 1B), the elemental material volume dU defined by these three vectors at time = 0 is given as

|

(4) |

The spatial vectors in the deformed configuration are given by

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

The triple product of these elemental vectors gives the deformed volume du as

|

(8) |

where detF is the determinant of F. Therefore, the myocardial volume V relative to the unit myocardial volume (=1.00) at the reference configuration (=end diastole) is given by

|

(9) |

To validate myocardial volume calculation using finite deformation, we also calculated myocardial volume change within individual tetrahedra created by intramyocardial beads (Fig. 1C). The data over time were linearly interpolated over time to yield the same number of data points in each cardiac phase in each animal. The number of data points was the average number of data points in each cardiac phase among all the animals (n = 15). The time course was determined at three transmural layers as follows: 20% (subepi), 50% (midwall), and 80% wall depth (subendo).

The rate of myocardial volume change V̇ is expressed as

|

(10) |

When the specific mass of the myocardium is 1.05 (g/ml) (34), the volume increase ΔVin (ml/g) from end systole (ES) to end diastole (ED) is expressed as

|

(11) |

The rate of myocardial volume increase V̇in (ml·min−1·g−1) is thus expressed as

|

(12) |

If the myocardial volume increase is caused solely by myocardial blood flow, the value of V̇in should be similar to myocardial blood flow (ml·min−1·g−1).

As a surrogate for the regional mechanical work, regional work index WLV was defined as the area of the LV pressure-fiber stretch ratio (λf) loop. The fiber stretch ratio represents the myofiber length normalized to its length at end diastole, and is defined as

|

(13) |

where Eff is the strain with respect to the local fiber coordinate, calculated from the Lagrangian Green's strain tensor E

|

(14) |

and histologically measured fiber angles at each depth (4). FT is the transpose of F, and I is the identity matrix. WLV was compared between different pacing modes at the same depth. The value of WLV is normalized to atrial pacing at each layer.

Statistical analysis.

Values are means ± SD. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess the transmural gradient of the mean values and any difference between different pacing modes. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat 3.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Of 15 animals studied, one animal data were excluded because a total of 5 beads in this animal appeared overlapped in both biplane cineradiographic views, and calculated radial velocity of these beads far exceeded the maximum wall thickening rate. As a result, 14 animals with atrial pacing, 11 animals with anterior LV pacing, and 7 animals with posterior LV pacing were included in the final analysis. The site of myocardial deformation measurement was located at 68 ± 9% of the distance from base to apex along the LV long axis in a region of the anterior LV free wall 1 to 2 cm septal of the anterolateral papillary muscle. The average end-diastolic myocardial volume within the bead set was 0.42 ± 0.12 ml.

Validation of myocardial volume calculation using finite deformation.

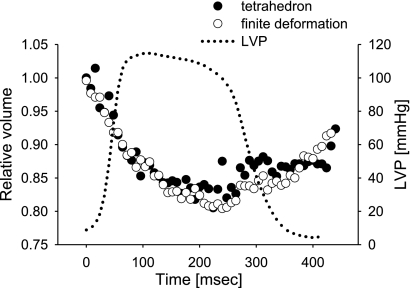

Figure 2 shows excellent agreement of myocardial volume change using finite deformation and tetrahedral volumes in a representative animal. In all animals studied, there was no significant difference in end-systolic relative myocardial volumes between finite deformation and tetrahedral methods at any layers [P = not significant (NS)].

Fig. 2.

Validation of myocardial volume calculation using finite deformation. Myocardial volume change using finite deformation (open circle) and tetrahedral volumes (closed circle) in a representative animal are compared (the temporal resolution is 8 ms/frame). The values are expressed as volume relative to 1.00 at end diastole. LVP, left ventricular pressure.

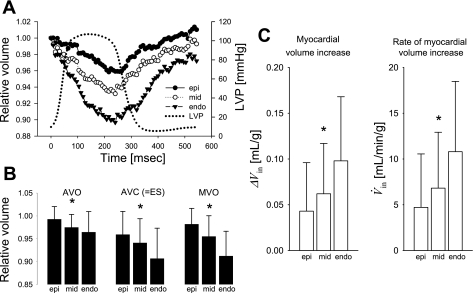

Myocardial volume change during atrial pacing.

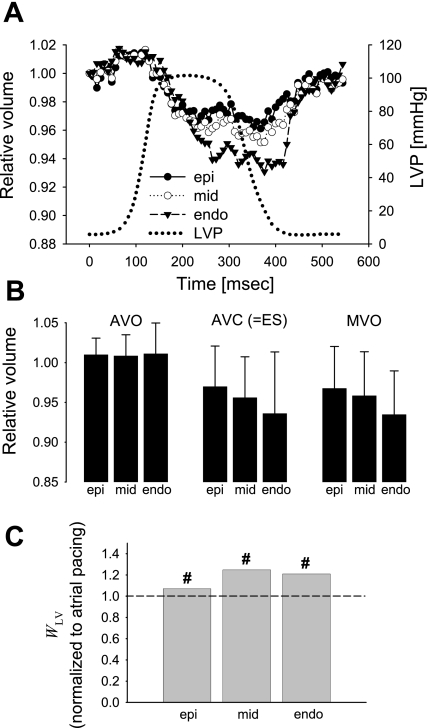

Myocardial volume decreased consistently during systole (Fig. 3A), reaching the minimum values of 0.959 ± 0.050, 0.932 ± 0.040, and 0.897 ± 0.070 at AVC, indicating a volume decrease of 4.1, 6.8, and 10.3% at subepi, midwall, and subendo layers, respectively (Table 1). Following ES, the myocardial volume increased, returning to the baseline volume (∼1.00, Fig. 3A). There was a significant transmural gradient of relative myocardial volumes at AVO, AVC, and MVO (P < 0.02, Fig. 3B). The myocardial volume increase ΔVin was 0.043 ± 0.053, 0.062 ± 0.055, and 0.098 ± 0.070 (ml/g) (subepi, midwall, and subendo layer, respectively), and there was a significant transmural gradient (P = 0.01, Fig. 3C). Rate of myocardial volume increase V̇in was 4.7 ± 5.8, 6.8 ± 6.1, and 10.8 ± 7.7 [ml·min−1·g−1], respectively, and there was a significant transmural gradient (P = 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Myocardial volume change during atrial pacing (n = 14). A: time course. Values are means and are expressed as volume relative to 1.00 at end diastole. Epi (closed circle), mid (open circle), and endo (closed triangle) represent 20, 50, and 80% wall depth from the epicardial surface, respectively. B: relative myocardial volume at aortic valve opening (AVO), aortic valve closure (AVC) or end systole (ES), and mitral valve opening (MVO). Values are means, and error bars are SD. *Transmural gradient (P < 0.02). C: myocardial volume increase during diastole. Values are means, and error bars are SD. *Transmural gradient (P = 0.01).

Table 1.

Maximum myocardial volume change during the cardiac cycle

| Pacing Mode | Subepi | Midwall | Subendo | Timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial pacing | 0.959±0.050 | 0.932±0.040 | 0.897±0.070 | AVC |

| −4.1% | −6.8% | −10.3% | ||

| LV pacing—early activated region | 0.962±0.026 | 0.955±0.041 | 0.922±0.054 | Ejection |

| −3.8% | −4.5% | −7.8% | ||

| LV pacing—late activated region | 0.961±0.039 | 0.951±0.039 | 0.931±0.057 | MVO |

| −3.9% | −4.9% | −6.9% |

Values are means ± SE. The values on the top row during each pacing mode are expressed as volume relative to 1.00 at end diastole and those on the bottom row are expressed as percent change relative to end diastole. LV, left ventricular; AVC, atrial valve closure; MVO, mitral valve opening.

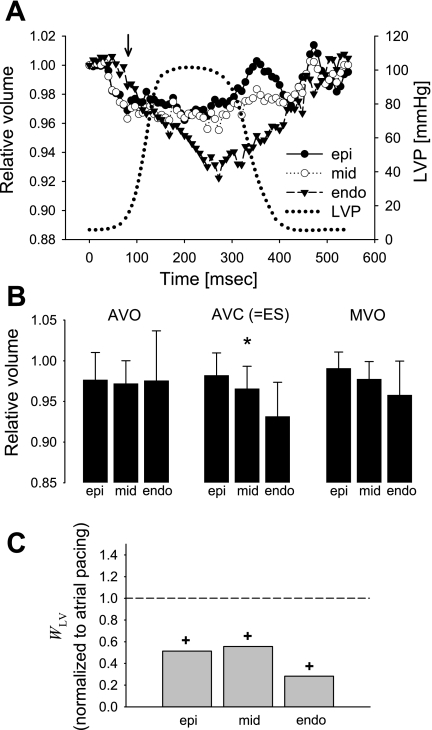

Myocardial volume change during LV pacing.

At the early activated site, LV pacing reduced a systolic decrease in myocardial volume, reaching minimum values of 0.962 ± 0.026, 0.955 ± 0.041, and 0.922 ± 0.054 during ejection, indicating a volume decrease of 3.8, 4.5, and 7.8%, at subepi, midwall, and subendo layers, respectively (Fig. 4A). The transmural gradient was abolished at AVO (P = NS) and MVO (P = NS), but still maintained at AVC (P = 0.012, Fig. 4B). Of note, myocardial volume clearly began to decrease before the LV pressure upstroke (Fig. 4A). WLV normalized to atrial pacing was 0.51, 0.56, and 0.28 at subepi, midwall, and subendo layers, respectively, resulting in the transmural average of 0.45 (Fig. 4C). WLV was significantly reduced from those of atrial pacing at all layers (P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Myocardial volume change at the early activated region during LV pacing (n = 11). A: time course. Values as in Fig. 3. A solid arrow in the early activated region shows that the myocardial volume clearly began to decrease before the LV pressure upstroke, supporting the concept that thickening and impingement of individual myofibers have significant effects on the intramyocardial vessel size and flow. B: relative myocardial volume at AVO, AVC or ES, and MVO. Values as in Fig. 3. *Transmural gradient (P < 0.02). C: regional work index WLV. Values are means of WLV normalized to atrial pacing at each layer. +P < 0.02 vs. atrial pacing.

In contrast, at the late activated site, the myocardial volume increased during early systole then decreased following AVO, reaching minimum values of 0.961 ± 0.039, 0.951 ± 0.039, and 0.931 ± 0.057 at MVO, indicating a volume decrease of 3.9, 4.9, and 6.9% at subepi, midwall, and subendo layers, respectively (Fig. 5A). The transmural gradient was abolished at AVO, MVO, or AVC (P = NS, Fig. 5B). WLV normalized to atrial pacing was 1.07, 1.25, and 1.21, respectively, resulting in the transmural average of 1.18 (Fig. 5C). WLV was not significantly different compared with atrial pacing but was significantly increased compared with those of the early activated region at all layers (P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

Myocardial volume change at the late activated region during LV pacing (n = 7). A: time course. Values as in Fig. 3. B: relative myocardial volume at AVO, AVC or ES, and MVO. Values as in Fig. 3. There was no significant transmural gradient at any time point [P = not significant (NS)]. C: regional work index WLV. Values are means of WLV normalized to atrial pacing at each layer. #P < 0.01 vs. early activated region.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the regional volume change was derived from 3-D myocardial displacements within the intramyocardial bead set using finite deformation, which provided high spatiotemporal resolution data on myocardial volume change in mechanically synchronous and dyssynchronous hearts. The myocardial volume data from finite deformation agreed well with actual volume measurements using tetrahedra created by intramyocardial beads, which provides confidence in our techniques used in the study (Fig. 2).

Myocardial volume change during the cardiac cycle.

Our results clearly show that the myocardial volume undergoes a dynamic change during the cardiac cycle (Fig. 3A). The myocardial volume at all layers decreased during systole and reached the minimum near AVC (=ES), and there was a significant transmural gradient throughout the cardiac cycle. Maximum volume change of the subendocardial layer was 10.3%, almost threefold larger than the subepicardial volume change (4.1%, Table 1). Myocardial volume change in the published literature can be calculated from myocardial deformation. Techniques using the implanted markers showed that a systolic decrease in myocardial volume in dogs ranges from 5% (15) to 20% (43) in the midanterior wall, whereas the systolic decrease is 1% in the midseptum (28). The same technique showed a systolic decrease of up to 7.3% in the midanterior wall of the pig (29) and 0.7% in the anterolateral wall of the sheep (13). A study using a computed tomography-based technique without material markers in the myocardium reported a 12% systolic increase in the myocardial volume in dogs (25); however, this result likely involves measurement errors due to relatively low image quality and manual segmentation of the myocardial border. Another study using a motion-encoding magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique showed up to a 1.5% systolic decrease in the equatorial one-third section in beagles (35). Although these studies did not have the temporal or spatial resolution of the present study, the results from these studies suggest that the measured differences in the myocardial volume change are due to regional and species heterogeneity.

Myocardial volume change and blood flow: implications for cardiac structure and blood flow.

A phasic change in the myocardial volume during the cardiac cycle and its direct correlation with coronary blood flow has been investigated. Gaasch and Bernard (20) found a 10% decrease in the end-diastolic LV wall thickness during acute coronary artery ligation and a 13% increase during reperfusion-induced reactive hyperemia. Although some of the decrease in the LV wall thickness may be accounted for by ventricular expansion due to ischemia, the larger systolic decrease in the subendocardium in our data agrees with the findings of earlier reports that showed systolic changes in vascular volume (38). Hess and Bache (22) found an endocardial/epicardial flow ratio of 0.53 during systole, which indicates a greater systolic volume change and flow impediment in the subendocardium (16). Toyota et al. (38) compared the microvascular volumes in systolic and diastolic fixed hearts and found a 37% decrease in the subendocardial layers. Goto et al. (21) in a similar approach found a 43% systolic reduction in arteriolar diameters of the subendocardial layer. The greater reduction in blood volume in the subendocardium is likely a cause of systolic arterial flow reversal, or the “coronary slosh” phenomenon (23, 26, 39), where a fraction of blood volume is transferred or pushed away from the subendocardium during systole.

However, ΔVin appears too large to be caused only by the myocardial blood flow. We found up to a 10.3% volume increase per cardiac cycle (Table 1), and the rate of myocardial volume increase V̇in at subepi, midwall and subendo layers was 4.7 ± 5.8, 6.8 ± 6.1 and 10.8 ± 7.7 ml·min−1·g−1, respectively (Table 2). These values are substantially larger than the myocardial blood inflow measured by the microsphere method (0.7–1.3 ml·min−1·g−1)(16). In theory, the microsphere method measures the average blood inflow in ml·min−1·g−1. The measured microsphere blood flow would cause a myocardial volume increase of only 1% per contraction (35), and cannot explain the level of volume increase observed in the present study. Based on these results, an additional source of the myocardial volume should be present that is not accounted for by coronary blood supply. Because there are systolic decreases in volume in all layers of the ventricular myocardium, the source would not be the capacitance reservoirs within the ventricular myocardium but should be outside the site of measurement. This suggests that the source of volume would either be the epicardial coronary vessels or the ventricular lumen. Without quantitative inflow and outflow information, it is not possible to separate these two possibilities. However, because previous studies have not shown a large negative venous blood flow (11), which would contribute the volume increase during diastole, we speculate that the ventricular lumen is the most logical possibility.

Table 2.

Myocardial volume increase

| Pacing Mode | Variable | Subepi | Midwall | Subendo | ANOVA (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial pacing | ΔVin | 0.043±0.053 | 0.062±0.055 | 0.098±0.070 | 0.01 |

| V̇in | 4.7±5.8 | 6.8±6.1 | 10.8±7.7 | 0.01 | |

| LV pacing—early activated region | ΔVin | 0.019±0.029 | 0.036±0.029 | 0.072±0.044 | 0.012 |

| V̇in | 2.1±3.2 | 4.0±3.2 | 7.9±4.9 | 0.012 | |

| LV pacing—late activated region | ΔVin | 0.032±0.053 | 0.046±0.054 | 0.067±0.081 | NS |

| V̇in | 3.5±5.9 | 5.1±5.9 | 7.4±9.0 | NS |

Values are means ± SE. ΔVin, myocardial volume increase (ml/g); V̇in, rate of myocardial volume increase (ml·min−1·g−1) . ANOVA used for assessment of significant transmural gradient (P < 0.05). NS, not significant.

It is possible to estimate from our data the volume of such blood-filled spaces within the ventricular myocardium that could communicate with the ventricular lumen. Assuming that the transmural blood flow is 1.0 ml·min−1·g−1 for simplicity, the rate of volume increase beyond blood flow is 3.7 ± 5.8, 5.8 ± 6.1 and 9.8 ± 7.7 ml·min−1·g−1 at subepi, midwall, and subendo layers, respectively (Table 2). Using the average cycle length of all animals (= 544 ms), the volume increase beyond blood flow is 0.034 ± 0.053, 0.053 ± 0.055, and 0.089 ± 0.070 ml/g (e.g., 9.8 × 0.544/60 = 0.089 for subendo). When the specific mass of the myocardium is 1.05 g/ml, these volume increases would be accommodated by 3.5, 5.5, and 9.3% of the myocardial volume, respectively (e.g., 0.089 × 1.05 = 0.093 for subendo).

We speculate that three anatomical structures would potentially constitute the blood-filled spaces within the myocardium, which contribute to the myocardial volume change during the cardiac cycle and explain the larger volume changes than expected from the myocardial blood flow measured by the microsphere method.

The first potential structure is anatomical communication between coronary vessels and ventricular lumens, which have been described in the normal human heart for centuries (37, 44), as recently reviewed by Angelini (1). Arterio-luminal communications connect a precapillary arteriolar vessel to sinusoidal, ventricular intertrabecular spaces that are found in 86% of LV and 50% of right ventricles (7). They are short with luminal areas of 50–200 μm, lack functional medial layers (2, 7), and are not revealed by clinical angiography. Coronary-venous communications, or Thebesian veins, are especially frequent in the normal right atrium and ventricle. Their diameter is up to 2 mm; thus, these communications are angiographically visible, especially at the right ventricular outflow tract, where they provide the predominant coronary drainage.

The second potential structure is ventricular trabecular tissue. Novel observations of the ventricular trabecular tissue have recently been made by advanced cardiac imaging systems in vivo, which could not have been conducted in fixed histological tissues. Traditionally, an exaggerated form of trabeculation was considered to be present only in a congenital condition called noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium, or hypertrabeculation, where cardiac development somehow halts before compaction of the ventricular trabecular tissue (8). However, recent studies demonstrated that the trabecular tissue composes as much as 50% from the endocardial border in the LV wall in human (31), and the condition similar to the noncompaction but to a lesser degree is observed in 91% of normal subjects (32). The trabecular tissue is most often prominent in the apical areas near the papillary muscles, which do not directly attach to the solid heart wall but to the trabecular tissue (6) and is lined with the endothelium and no direct connection to the ventricular lumen (19). However, if rich trabecular tissue played a major role in myocardial volume change in our setting, we would have observed some of the endocardial beads lost in the LV cavity, which was not the case. In addition, although trabecular tissue may contribute to the volume change, it is unlikely to play a major role in the subepicardial and midmyocardial layers.

The third potential structure that would provide volume change within the ventricular myocardium is cleavage spaces between myolaminar sheets. Given the dynamic mobility of the sheet structure, it is possible that the cleavage spaces between the sheets would also undergo dynamic change during the cardiac cycle, contributing to the volume change observed in our study.

Effects of LV pacing on myocardial volume change.

LV pacing diminished the systolic decrease and altered the timing of maximum volume change (Figs. 4 and 5 and Table 1), resulting in a loss of transmural gradient. Therefore, mechanical dyssynchrony disrupts the physiological transmural gradient in myocardial volume change. Furthermore, in the early activated region, myocardial volume clearly began to decrease before the LV pressure upstroke (Fig. 4A). This finding is not surprising because the fiber contraction in early activated regions precedes global pressure development in mechanically dyssynchronous hearts (5, 27, 46). However, this observation contradicts the notion that the increase in the LV chamber pressure is the principal source of systolic intramyocardial vascular volume change and instead serves as evidence in support of the concept that thickening and impingement of individual myofibers have significant effects on the intramyocardial vessel size and flow (45).

Implications for structural remodeling in mechanical dyssynchrony.

Chronic mechanical dyssynchrony induces ventricular thinning in the early activated region and ventricular hypertrophy in the late activated region (27). Our results showed that WLV was significantly reduced in the early activated region and increased in the late activated region compared with atrial pacing (Fig. 4B), which is consistent with earlier studies (34). We and others have speculated that this finding would explain the ventricular thickening and hypertrophy occurring in the late activated region (40, 41). In contrast, the early activated region is associated with significantly reduced blood flow (40, 42) and reduced work. Relative underperfusion and atrophy from the decreased work load have already been proposed as potential mechanisms for the wall thinning in early activated sites (33). In addition to these changes, the loss of the normal systolic transmural gradient in volume change in early activated areas in our data (Fig. 4B) indicates that flow in capacitance vessels, including small veins and venous plexi, may be altered. Changes in venous flow patterns are known to activate inflammatory changes with an increased expression of adhesion molecules (10, 12) and higher levels of inflammatory cell binding (24), which could lead to cell loss and fibrosis.

Limitations.

There are errors associated with the digitization of the two-dimensional images and reconstruction of 3-D marker locations. The 3-D spatial resolution of the system is ∼0.07 mm. Assessment of the propagation of this error revealed that the variability in strain values was <0.02. The diameter of the intramyocardial beads was 0.8 mm; thus, the volume of each bead was 2.7 × 10−4 ml, which is only 0.06% of the volume enclosed by the beads (0.42 ml). Therefore, we do not believe that the size of the intramyocardial beads was too large for the measurement volume. However, the volume of myocardium bounded by the bead set was small, and local inhomogeneities may have influenced the results. It is possible that the linear interpolation process to obtain the same number of data points in each cardiac phase in each sample increased the uncertainty of the data in this study. However, the level of temporal resolution of our biplane cineradiography is 8 ms (=125 frames/s), which is significantly higher than that of other 3-D motion-measurement techniques, such as MRI and echocardiography. The number of data points was the average number of data points in each cardiac phase among all the animals, meaning that the number of data points was roughly the same before and after linear interpolation in each sample. Therefore, the effect of overinterpolation (more data points than the raw data points) or underinterpolation (fewer data points than the raw data points) would be minimal. Given the high temporal resolution in the raw data (8 ms), it is unlikely that the linear interpolation process created a significant level of uncertainty of the data. Because the experiment was performed on the same day as the bead insertion, the “holes” of inserting the beads may have created artificial spaces in the myocardium. This artificial space may partially account for the large transmural gradient in the volume change observed, because deformation is larger at the endocardium. However, examination of an additional data of nine closed-chest animals in our laboratory revealed that the average end-systolic myocardial volume decrease at midwall was 4.1% at 7–10 days postbead implantation. Although this value is slightly smaller than 5.9% in the present study (Fig. 3B, AVC), there was no significant difference between these two groups (P = NS). This indicates that the effect of bead insertion holes on myocardial volume calculation is minimal, even when the experiment is performed on the same day as the bead insertion in an open-chest setup. The perfusion fixation in this study was conducted to measure fiber orientation at end-diastolic pressure. However, because fiber orientation does not significantly change during the cardiac cycle (36), contraction during the fixation process, either regional or global, would probably not have influenced fiber orientation. In fact, we did not observe abrupt transitions in fiber orientation. Our measurements were restricted to the midanterior LV. Therefore, our findings may not be applicable to other LV regions. The 3-D finite deformation that we measured in open-chest, anesthetized dogs may not accurately reflect the transmural deformation in closed-chest, conscious animals. In addition, measurements in the early and late activated regions were not conducted simultaneously. This might have affected the measured and calculated parameter values. It should also be emphasized that there seems to be substantial regional and species variations in the systolic volume change. In pigs, the myocardial volume decreases substantially at the subendocardium but increases slightly at the subepicardium, which implies the presence of vascular volume reservoirs within the myocardium and a possible blood transfer from subepicardium to subendocardium during diastole (29). In sheep (13) and beagles (35), the systolic decrease in volume is much smaller, which indicates that these spaces within the myocardium may not be present.

Conclusions

The myocardial volume undergoes a dynamic change during the cardiac cycle. The volume change is much greater than would be estimated from the known average transmural blood flow. This implies the existence of blood-filled spaces within the myocardium, which could communicate with the ventricular lumen or large epicardial vascular reservoirs. Our data also suggest that myocardial volume change is caused not by the intramyocardial tissue pressure but by direct impingement of the contracting myocytes on the microvasculature.

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 0225001Y (to H. Ashikaga, Western States Affiliate) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-43617 (to F. J. Villarreal and J. W. Covell) and R01-HL32583 (to J. H. Omens).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ghassan S. Kassab for valuable discussions on coronary anatomy and on the potential role of venous plexi. We also thank Rish Pavelec and Rachel Alexander for superb managerial and surgical assistance.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelini P Questions on coronary fistulae and microfistulae. Tex Heart Inst J 32: 53–55, 2005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelini P, Villason S, Chan AVJ, Diez JG. Normal and anomalous coronary arteries in humans. In: Coronary Artery Anomalies: A Comprehensive Approach, edited by Angelini P. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999, p. 27?150.

- 3.Ashikaga H, Coppola BA, Hopenfeld B, Leifer ES, McVeigh ER, Omens JH. Transmural dispersion of myofiber mechanics: implications for electrical heterogeneity in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 909–916, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashikaga H, Criscione JC, Omens JH, Covell JW, Ingels NB Jr. Transmural left ventricular mechanics underlying torsional recoil during relaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H640–H647, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashikaga H, Omens JH, Ingels NB Jr, Covell JW. Transmural mechanics at left ventricular epicardial pacing site. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H2401–H2407, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Axel L Papillary muscles do not attach directly to the solid heart wall. Circulation 109: 3145–3148, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baroldi G, Scomazzoni G. Coronary Circulation in the Normal Heart and the Pathologic Heart. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt Printing Office, 1967.

- 8.Baumhakel M, Janzen I, Kindermann M, Schneider G, Hennen B, Bohm M. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Cardiac imaging in isolated noncompaction of ventricular myocardium. Circulation 106: e16–e17, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonet J, Wood RD. Kinematics. In: Nonlinear Continuum Mechanics for Finite Element Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press, 1997, p. 110–112.

- 10.Brooks AR, Lelkes PI, Rubanyi GM. Gene expression profiling of human aortic endothelial cells exposed to disturbed flow and steady laminar flow. Physiol Genomics 9: 27–41, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chadwick RS, Tedgui A, Michel JB, Ohayon J, Levy BI. Phasic regional myocardial inflow and outflow: comparison of theory and experiments. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 258: H1687–H1698, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chappell DC, Varner SE, Nerem RM, Medford RM, Alexander RW. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates adhesion molecule expression in cultured human endothelium. Circ Res 82: 532–539, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng A, Langer F, Rodriguez F, Criscione JC, Daughters GT, Miller DC, Ingels NB Jr. Transmural cardiac strains in the lateral wall of the ovine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1546–H1556, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coppola BA, Covell JW, McCulloch AD, Omens JH. Asynchrony of ventricular activation affects magnitude and timing of fiber stretch in late-activated regions of the canine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H754–H761, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa KD, Takayama Y, McCulloch AD, Covell JW. Laminar fiber architecture and three-dimensional systolic mechanics in canine ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H595–H607, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feigl EO Coronary physiology. Physiol Rev 63: 1–205, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenton TR, Cherry JM, Klassen GA. Transmural myocardial deformation in the canine left ventricular wall. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 235: H523–H530, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenton TR, Klassen GA, Outerbridge JS. Radiographic measurement of transmural myocardial deformation. Intern Conf Med Biol Eng 11th, Ottawa, Canada, 1976, p. 714–715.

- 19.Freedom RM, Yoo SJ, Perrin D, Taylor G, Petersen S, Anderson RH. The morphological spectrum of ventricular noncompaction. Cardiol Young 15: 345–364, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaasch WH, Bernard SA. The effect of acute changes in coronary blood flow on left ventricular end-diastolic wall thickness. An echocardiographic study. Circulation 56: 593–598, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goto M, Flynn AE, Doucette JW, Jansen CM, Stork MM, Coggins DL, Muehrcke DD, Husseini WK, Hoffman JI. Cardiac contraction affects deep myocardial vessels predominantly. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1417–H1429, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess DS, Bache RJ. Transmural distribution of myocardial blood flow during systole in the awake dog. Circ Res 38: 5–15, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiramatsu O, Goto M, Yada T, Kimura A, Chiba Y, Tachibana H, Ogasawara Y, Tsujioka K, Kajiya F. In vivo observations of the intramural arterioles and venules in beating canine hearts. J Physiol 509: 619–628, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda HM, Hsiai T, Wortham CM, Chen M, Lin H, Navab M, Demer LL. A complex flow pattern of low shear stress and flow reversal promotes monocyte binding to endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 158: 385–390, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwasaki T, Sinak LJ, Hoffman EA, Robb RA, Harris LD, Bahn RC, Ritman EL. Mass of left ventricular myocardium estimated with dynamic spatial reconstructor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 246: H138–H142, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kajiya F, Yada T, Matsumoto T, Goto M, Ogasawara Y. Intramyocardial influences on blood flow distributions in the myocardial wall. Ann Biomed Eng 28: 897–902, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kass DA Ventricular resynchronization: pathophysiology and identification of responders. Rev Cardiovasc Med 4, Suppl 2: S3–S13, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeGrice IJ, Takayama Y, Covell JW. Transverse shear along myocardial cleavage planes provides a mechanism for normal systolic wall thickening. Circ Res 77: 182–193, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeGrice IJ, Takayama Y, Holmes JW, Covell JW. Impaired subendocardial function in tachycardia-induced cardiac failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H1788–H1794, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKay SA, Potel MJ, Rubin JM. Graphics methods for tracking three-dimensional heart wall motion. Comput Biomed Res 15: 455–473, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters DC, Ennis DB, McVeigh ER. High-resolution MRI of cardiac function with projection reconstruction and steady-state free precession. Magn Reson Med 48: 82–88, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen SE, Selvanayagam JB, Wiesmann F, Robson MD, Francis JM, Anderson RH, Watkins H, Neubauer S. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 101–105, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prinzen FW, Augustijn CH, Arts T, Allessie MA, Reneman RS. Redistribution of myocardial fiber strain and blood flow by asynchronous activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H300–H308, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prinzen FW, Hunter WC, Wyman BT, McVeigh ER. Mapping of regional myocardial strain and work during ventricular pacing: experimental study using magnetic resonance imaging tagging. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1735–1742, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez I, Ennis DB, Wen H. Noninvasive measurement of myocardial tissue volume change during systolic contraction and diastolic relaxation in the canine left ventricle. Magn Reson Med 55: 484–490, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streeter DD, Spotnitz HM, Patel DP, Ross J Jr, Sonnenblick EH. Fiber orientation in the canine left ventricle during diastole and systole. Circ Res 24: 339–347, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thebesius AC Disputatio medica de circulo sanguinis in corde. Lugduni Batavorum, 1708.

- 38.Toyota E, Fujimoto K, Ogasawara Y, Kajita T, Shigeto F, Matsumoto T, Goto M, Kajiya F. Dynamic changes in three-dimensional architecture and vascular volume of transmural coronary microvasculature between diastolic- and systolic-arrested rat hearts. Circulation 105: 621–626, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toyota E, Ogasawara Y, Hiramatsu O, Tachibana H, Kajiya F, Yamamori S, Chilian WM. Dynamics of flow velocities in endocardial and epicardial coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1598–H1603, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Oosterhout MF, Arts T, Bassingthwaighte JB, Reneman RS, Prinzen FW. Relation between local myocardial growth and blood flow during chronic ventricular pacing. Cardiovasc Res 53: 831–840, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Oosterhout MF, Prinzen FW, Arts T, Schreuder JJ, Vanagt WY, Cleutjens JP, Reneman RS. Asynchronous electrical activation induces asymmetrical hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall. Circulation 98: 588–595, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vernooy K, Verbeek XA, Peschar M, Crijns HJ, Arts T, Cornelussen RN, Prinzen FW. Left bundle branch block induces ventricular remodelling and functional septal hypoperfusion. Eur Heart J 26: 91–98, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waldman LK, Fung YC, Covell JW. Transmural myocardial deformation in the canine left ventricle. Normal in vivo three-dimensional finite strains. Circ Res 57: 152–163, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wearn JT, Mettier SR, Klumpp TG, Zschiesche L. The nature of the vascular communications between the coronary arteries and the chambers of the heart. Am Heart J 9: 143–164, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westerhof N, Boer C, Lamberts RR, Sipkema P. Cross-talk between cardiac muscle and coronary vasculature. Physiol Rev 86: 1263–1308, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyman BT, Hunter WC, Prinzen FW, McVeigh ER. Mapping propagation of mechanical activation in the paced heart with MRI tagging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H881–H891, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoran C, Covell JW, Ross J Jr. Rapid fixation of the left ventricle: continuous angiographic and dynamic recordings. J Appl Physiol 35: 155–157, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]