Abstract

Cardiomyocyte N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-1 (NMDA-R1) activation induces mitochondrial dysfunction. Matrix metalloproteinase protease (MMP) induction is a negative regulator of mitochondrial function. Elevated levels of homocysteine [hyperhomocysteinemia (HHCY)] activate latent MMPs and causes myocardial contractile abnormalities. HHCY is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. We tested the hypothesis that HHCY activates myocyte mitochondrial MMP (mtMMP), induces mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), and causes contractile dysfunction by agonizing NMDA-R1. The C57BL/6J mice were administered homocystinemia (1.8 g/l) in drinking water to induce HHCY. NMDA-R1 expression was detected by Western blot and confocal microscopy. Localization of MMP-9 in the mitochondria was determined using confocal microscopy. Ultrastructural analysis of the isolated myocyte was determined by electron microscopy. Mitochondrial permeability was measured by a decrease in light absorbance at 540 nm using the spectrophotometer. The effect of MK-801 (NMDA-R1 inhibitor), GM-6001 (MMP inhibitor), and cyclosporine A (MPT inhibitor) on myocyte contractility and calcium transients was evaluated using the IonOptix video edge track detection system and fura 2-AM. Our results demonstrate that HHCY activated the mtMMP-9 and caused MPT by agonizing NMDA-R1. A significant decrease in percent cell shortening, maximal rate of contraction (−dL/dt), and maximal rate of relaxation (+dL/dt) was observed in HHCY. The decay of calcium transient amplitude was faster in the wild type compared with HHCY. Furthermore, the HHCY-induced decrease in percent cell shortening, −dL/dt, and +dL/dt was attenuated in the mice treated with MK-801, GM-6001, and cyclosporin A. We conclude that HHCY activates mtMMP-9 and induces MPT, leading to myocyte mechanical dysfunction by agonizing NMDA-R1.

Keywords: myocyte, calcium, mitochondrial permeability, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-1, arrhythmogenesis

the pathophysiology of chronic heart failure (CHF) involves abnormalities in systolic and/or diastolic function and increases the propensity for reentry arrhythmias (30, 6). Continued elevation of cardiac sympathetic drive contributes to myocardial toxicity, leading to the decline in cardiac contractility (29). Recent observations suggest an increase in glutamatergic activity on sympathetic regulation, due to the upregulation of hypothalamic N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-1 subunits (NMDA-R1) during CHF (16). Ischemia- and reperfusion-induced arrhythmias are sensitive to NMDA-R1 blockade (8).

Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHCY) is a graded risk factor for CHF (12, 7) and for sudden cardiac death (SCD) resulting from coronary fibrous plaques (4, 1, 5). Homocysteinemia (HCY) induces interstitial cardiac fibrosis leading to systolic/diastolic dysfunction (13). The antagonist to the NMDA-R protects against HCY-induced oxidative damage in neurons (10) and protects against the increase in heart rate by NMDA analog (9), suggesting that HCY is an agonist to NMDA-R. The cardiomyocyte expresses NMDA-R. Furthermore, the activation of NMDA-R increases oxidative stress and calcium load in the mitochondria, leading to cell death in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (11). However, the functional consequences of myocyte NMDA-R activation in HHCY are not well understood. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) are the Zn-containing endopeptidases involved in extracellular matrix turnover and induces structural remodeling leading to arrhythmogenesis (14, 32, 24). MMP activation in HHCY decreases the collagen-to-elastin ratio, increases the deposition of interstitial collagen (fibrosis) between endothelium and myocytes, and is arrhythmogenic (27, 32, 30). NMDA-R antagonist inhibits MMP activation (21) and attenuates SCD (19).

Recently, the concept that “MMPs are not just for the matrix anymore” has been emerged (20). Intracellular localization of MMP has been suggested. MMP-2 is synthesized by both cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts and is colocalized with contractile proteins such as troponin I within myofilaments (34) and sarcomeres (28). Acute activation of MMP-2 leads to a reduction of contractile performance following ischemia-reperfusion injury (29).

We and others have shown the presence of MMP in the cardiac mitochondria (mtMMP) (23, 17, 18). However, the physiological consequences of MMP activation in the mitochondria are not well understood. Although there is little information regarding the mechanisms by which MMP-2 disrupts mitochondria, it is well-recognized that reactive oxygen species generated by mitochondria can drive both MMP-2 expression and activation (25). Such activation could result in a negative feedback mechanism that degrades mitochondrial membrane potential and impairs mitochondrial function (36). We have shown that HCY-induced calpain protease activation induces mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), and the treatment with NMDA-R1 blocker MK-801 attenuates HCY-induced MPT in HL-1 cardiomyocytes (23).

Therefore, in present study, we question the possible mechanism by which the NMDA-R-mediated activation of mtMMP causes decline in myocyte contractility in HHCY and whether the MPT regulates the myocyte mechanical function in HHCY.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and experimental protocol.

C57BL/6J mice procured from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were housed in a controlled environment on 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Mice were divided into four groups. WT mice were fed with normal mouse chow; HHCY was induced by administering the mice with 1.8 g DL-HCY/l in drinking water for 10 wk (water was changed every alternate day). Mice were injected with MK-801 (NMDA-R1 blocker, 0.1 mg/kg body wt), GM-6001 (MMP inhibitor, 100 mg/kg body wt), and cyclosporin A (CsA, MPT inhibitor, 20 mg/kg body wt) intrapertonially after the induction of HHCY. Animal experimentation was performed according to the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Louisville. All animal care and use programs were carried out according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub. no. 86–23, revised 1985) and the regulations of the Animal Welfare Act.

Adult ventricular myocyte isolation.

Single ventricular myocytes from the adult mouse heart were isolated according to the protocol from The Alliance for Cellular Signaling (http://www.signaling-gateway.org; protocol ID, PP00000125) with slight modifications. Briefly, hearts from 8- to 10-wk-old mice were removed rapidly and perfused with calcium-free perfusion buffer (in mmol/l: 120 NaCl, 14.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4xH2O, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, 10 Na-HEPES, 4.6 NaHCO3, 30 taurine, 10 glucose, and 10 butanedione monoxime, pH 7.4) and then with the same buffer with added Liberase Bledzyme 4 (0.9 mg/ml) (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) for 15–20 min until the heart become swollen and turned slightly pale. After perfusion, the ventricles were removed and minced under sterile conditions. The cell suspension was transferred to a conical tube, and perfusion buffer with 10% serum and 1.25 μmol/l calcium was added to stop the digestion. The heart tissue was further dissociated, and the myocytes were allowed to sediment. After removal of supernatant, the pellet was resuspended in the same buffer. Calcium was reintroduced in cells to the final concentration of 1.25 μmol/l. Isolated ventricular myocytes were maintained at room temperature in Hanks' buffer containing 5.6 mmol/l d-glucose and 1.25 μmol/l calcium.

Cell shortening/relengthening.

Mechanical properties of the ventricular myocytes were determined using a video-based edge-detection system (IonOptix, Milton, MA), as described elsewhere (35). The myocytes were field stimulated at a frequency of 1.0 Hz using a pair of platinum wires placed on the opposite sides of the dish chamber and connected to a MyoPacer Field Stimulator (IonOptix). The polarity of the stimulating electrodes was reversed frequently to avoid the buildup of electrolyte by-products. The myocytes were displayed on the monitor using an IonOptix MyoCam camera, and the image area was scanned every 8.3 ms such that the amplitude and velocity of shortening/relengthening was recorded. Soft-edge software (IonOptix) was used to capture changes in cell length during shortening and relengthening. The following parameters were recorded: percent cell shortening, maximal velocities of contraction (−dL/dt) and relaxation (+dL/dt).

Intracellular fluorescence measurement of calcium.

Intracellular calcium was determined using a dual-excitation fluorescence photomultiplier system (IonOptix), as described elsewhere (35). A separate cohort of myocytes was loaded with calcium-specific ratiometric fura 2-AM dye (1 μmol/l) for 30 min in the dark, and the fluorescence was recorded. Myocytes were placed in a dish chamber on the stage on an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope and imaged through a Fluor ×100 objective. Cells were exposed to light emitted by a 75-Watt lamp and were passed through either a 360- or 380-nm filter (bandwidths will be placed at ± 15 nm) while being stimulated to contract at 1.0 Hz. Fluorescence emission was detected between 480 and 520 nm by a photomultiplier tube after exciting the cells at 360 nm for 0.5 s and then at 380 nm for the duration of the recording protocol. A 360-nm scan was repeated at end of the experiments, and the qualitative changes in intracellular calcium concentration were interpreted from the ratio. The calcium transients were measured as changes in fura fluorescence intensity (FFI). ΔFFI was determined as the difference between the levels of calcium in systolic and diastolic settings (ΔFFI = peak FFI − baseline FFI). The time course of calcium fluorescence signal decay (τ, the duration at which calcium transient decays 67% from the peak level) was calculated to determine intracellular calcium clearing rate.

The myocytes included in the cell shortening/relengthening and calcium measurement studies met the following criterion: 1) rod shaped with clear striation pattern; 2) quiescent in the absence of electrical stimulation; 3) stable mechanical behavior at 0.25 or 2 Hz and 37°C for 15 min; and 4) absence of sarcolemmal blebs.

Transmission electron microscopy.

The ultrastructural analysis of isolated ventricular myocytes was performed using transmission electron microscopy, as described elsewhere (2) with slight modifications. The myocytes were fixed in 4.0% glutaraldehyde-0.1 M sodium cacodylate, postfixed in 1.0% osmium tetroxide-0.1 M sodium cacodylate, and stained en bloc by using 0.5% aqueous uranyl acetate. This was followed by dehydration in a graded alcohol series, with infiltration and embedment using Polybed 812 plastics (Polysciences). Thin sections were obtained using a Reichert Ultracut Ultramicrotome equipped with a diamond knife, collected on uncoated 200-mesh copper grids, poststained with lead citrate, and examined in a JEOL 1210 transmission electron microscope at 60 kV.

Assay of MPT.

Isolated cardiac mitochondria was resuspended in a medium containing (in mmol/l): 180 KCl, 10 EDTA, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, with 0.5% BSA. To remove EDTA and BSA, the mitochondrial pellet was washed two times with the buffer (in mmol/l: 180 KCl and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4). Mitochondrial swelling was determined by a decrease in light absorption at 540 nm with 250 μg of mitochondrial protein in swelling buffer containing (in mmol/l) 250 sucrose, 10 Tris-morpholinosulfonic acid, 0.05 EGTA, pH 7.4, 5 pyruvate, 5 malate, and 1 phosphate by the method described elsewhere (26). The MPT was measured before and after the addition of CaCl2 (250 μmol/l).

Confocal microscopy.

Isolated cardiomyocytes were washed two times with the incubation buffer (in mmol/l): 120.4 NaCl, 14.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4·H2O, 0.6 Na2HPO4, 0.6 KH2PO4, and 10 Na-HEPES, pH 7.4. The cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min. After being washed, the myocytes were incubated with primary anti-MMP-9 antibody (Sigma) (1:500 dilution, prepared in 0.02% Tween 20/PBS) overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed, and goat anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) (1:600 dilution, prepared in PBS) was applied for 3 h at room temperature. Cells were washed and incubated with 50 ng/ml Mitotracker Red in the dark for 25 min. After additional washes with PBS to remove unbound Mitotracker, the cells were mounted on the glass slides. The images were acquired using a laser confocal microscope (FluoView 1000). To enable the comparison of changes in fluorescence intensity and punctate staining pattern, the images were acquired under the identical set of conditions. FITC fluorescence was imaged using a bandpass filter set at 488 nm excitation and 510–540 nm emission. Mitotracker Red was imaged using a He-Ne laser (excitation 579 nm and emission 599 nm).

Immunoblotting.

Western blots were carried out using a standard protocol. Briefly, cells were harvested, washed two times in PBS, and incubated in the protein extraction buffer (in mmol/l: Tris, 50 mm, pH 7.4, 5 EDTA, 150 NaCl, and 1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1% Triton X-100), and supplemented with protease inhibitors for 1 h on ice. The cells were sonicated and centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 g in the cold. Protein concentration was assayed using the Bradford method. To determine the levels of calcium-handling proteins, an equal amount of protein (50 μg) was separated on 12% SDS-PAGE and blotted with the antibodies specific to sarcoplasmic endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA 2a; Abcam) and sodium/calcium exchanger (NCX; Abcam). The blots were immunodetected using appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies with an enhanced chemiluminescence plus detection kit. Image analysis was performed using UMAX PowrLock II to get the respective band intensities. The intensity of protein of interest is normalized with β-actin and plotted as a bar graph in terms of the degree of change over WT.

Statistics.

The number of physiological and contractility measurements are performed on 12–15 myocytes from 6–8 hearts in each group. Values are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance is carried out by Student's t-test. One- or two-way ANOVA is applied to compare between multiple groups. P < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

The plasma levels of HCY were 1.45 ± 0.5 μmol/l in control (n = 6), as measured by spectrophotometer. The levels of HCY were increased to 18 ± 0.5 μmol/l (n = 10) following 10 wk of HCY administration.

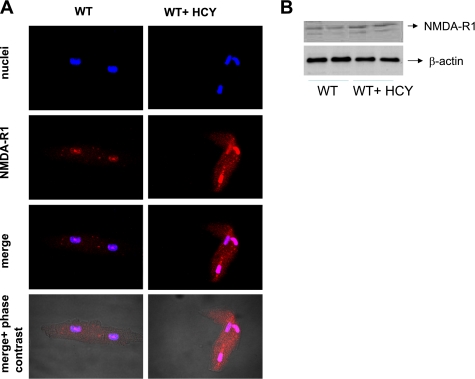

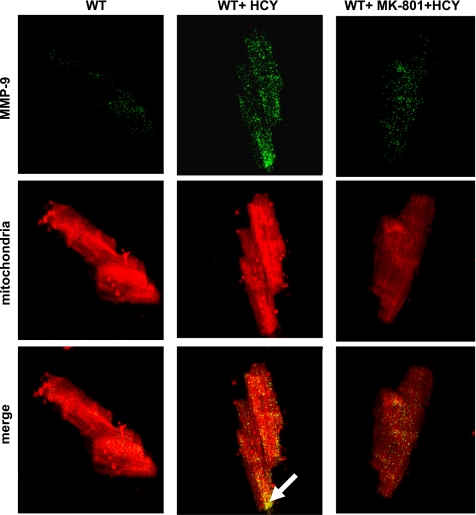

HCY induces systolic/diastolic dysfunction (13). Cardiomyocytes express NMDA-R1. We performed immunoconfocal imaging and Western blot to detect the NMDA-R1 expression levels in HHCY. We observed an increase in myocyte NMDA-R1 expression in HHCY (Fig. 1), suggesting that HCY acts as an NMDA-R1 agonist. NMDA-R antagonist inhibits MMP activation. The intracellular MMP activation causes contractile dysfunction (27). We determined whether HCY activates intracellular MMP via agonizing NMDA-R1. It was observed that HCY caused the activation of MMP in the myocyte mitochondria by activating NMDA-R1 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Homocysteinemia (HCY) induces cardiomyocyte N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-1 (NMDA-R1) expression. A: ventricular myocytes were isolated, permeabilized, and processed for confocal microscopy. A representative confocal image of myocyte NMDA-R1 expression is presented. The images were acquired by laser confocal microscope (FluoView 1000). B: total ventricular myocyte protein was isolated and processed for immunoblot analysis for NMDA-R1 expression. Data are representative of at least 2 different experiments (n = 4/group for each experiment).

Fig. 2.

HCY increases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression in the myocyte mitochondria by activating NMDA-R1. Isolated cardiomyocytes were fixed, permeabilized, and processed for confocal microscopy. A representative confocal image shows localization of MMP-9 in mitochondria (merged image with yellow pixels; magnification for objective lens, ×60). White arrows in merge panel indicated the expression of MMP-9 in myocyte mitochondria. To enable the comparison of changes in fluorescence intensity and punctate staining pattern, the images were taken under an identical set of conditions for all treatment groups. Data are representative of at least two different experiments (n = 3/group).

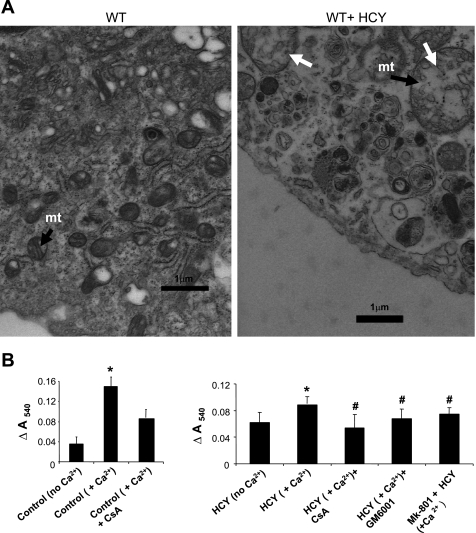

We and others have shown the presence of MMP in mtMMP; however, the physiological consequences of MMP activation in the mitochondria are not well understood. We determined whether HCY-induced activation of mtMMP causes mitochondrial damage. Our data on ultrastructural analysis of the isolated cardiomyocytes and mitochondrial swelling assay revealed that HCY induced the mitochondrial enlargement with the fragmentation of cristae (Fig. 3A). HCY caused the MPT by activating NMDA-R1 and involved MMP activation (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A: HCY instigates mitochondrial damage. Electron micrograph of the isolated cardiomyocyte from wild-type (WT; A) and HCY-treated (B) mice. mt, Mitochondria; white arrows, enlarged mitochondria with fragmented cristae. Magnification ×10,000. Scale represents 1 μm. B: HCY activates MMP and induces mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) by agonizing NMDA-R1. To the 20 mg/ml of the mitochondrial suspension in 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) swelling buffer (pH 7.4), 200 μmol/l CaCl2 were added to initiate swelling. The change (Δ) in absorbance at 540 nm (A540) was calculated and plotted (ΔA540 = A540max − A540min). Mice were injected with MK-801, GM-6001, and cyclosporin A (CsA), and 1 h later myocyte mitochondria were isolated and processed for swelling assay. P < 0.05 compared with experimental control (*) and compared with the treatment groups (#). Data represent two different experiments (n = 4/group).

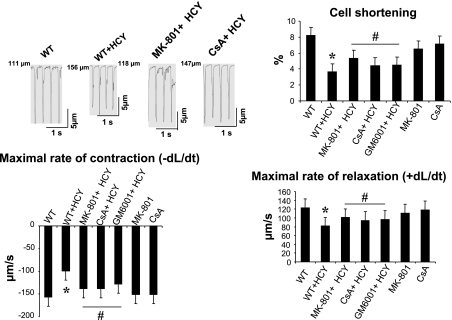

Activation of myocyte NMDA-R1 activation induces the mitochondrial dysfunction. Intracellular MMP activation causes contractile dysfunction (33). MMP activation degrades mitochondrial membrane potential and impairs mitochondrial function. We determined the effect of HCY on myocyte mechanical functions, including the percent cell shortening, maximal rate of contraction (−dL/dt), and maximal rate of relaxation (+dL/dt) and whether the HCY-induced alteration in myocyte contractile function involves mitochondria. We observed a significant decrease in the percent cell shortening in HHCY. HCY decreased the maximal rate of contraction (−dL/dt) and maximal rate of relaxation (+dL/dt) in isolated ventricular myocytes. Furthermore, the HCY-induced decrease in percent cell shortening (−dL/dt and +dL/dt) was attenuated in mice treated with MK-801, CsA, and GM-6001. This suggested that HCY decreased the myocyte contractility by activating the NMDA-R1 (Fig. 4). The MMP activation and induction of MPT was involved in the HCY-induced decrease in myocyte contractility.

Fig. 4.

HCY decreases myocyte mechanical function by activating NMDA-R1. Ventricular myocytes were field stimulated at 1-Hz pacing rate, and their mechanical properties were measured. %Cell shortening, maximal rate of contraction (−dL/dt), and maximal rate of relaxation (+dL/dt) were determined. Top left: cell shortening; top right: graphical presentation of %cell shortening; bottom, maximal rate of contraction (−dL/dt) and maximal rate of relaxation (+dL/dt). Values are means ± SE; n = 57–58 myocytes from 4–5 mice/group (n = 17–18 cells/group). P < 0.05 vs. WT mice (*) and vs. treatment groups (#).

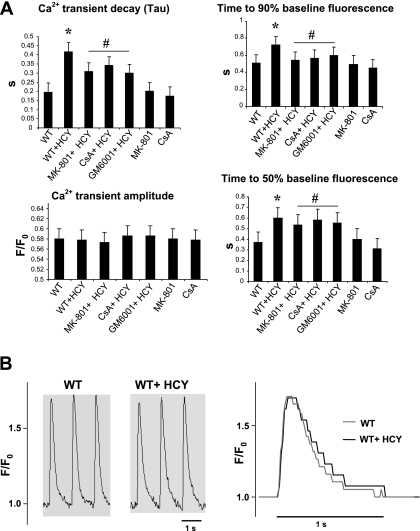

To determine whether HCY modifies myocyte calcium handling, we measured the calcium transient amplitude, calcium transient decay (Tau), and time to 50% and time to 90% baseline fluorescence using the IonOptix system in fura 2-AM-loaded myocytes. We observed a significant increase in time required to reach 50 and 90% baseline fluorescence in HHCY (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the treatment with MK-801, GM-6001, and CsA attenuated the HCY-induced increase in time required to reach 50 and 90% baseline fluorescence. Calcium transient amplitude was comparable in WT and HHCY myocytes; however, the calcium decay was faster in WT mice compared with HHCY myocytes (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, the HCY-induced slow rate of decay of calcium was attenuated by the treatment with MK-801, GM-6001, and CsA. This suggested that HCY altered the calcium transients by NMDA-R1 activation. This process involved MMP activation and induction of MPT.

Fig. 5.

HCY alters calcium transients in myocytes by agonizing NMDA-R1. A: calcium transient properties for WT (n = 6), hyperhomocysteinemia (HHCY; n = 5), MK-801 + HHCY (n = 8) CsA + HHCY (n = 8), and GM-6001 + HHCY (n = 6) were determined. Data are means ± SE. P < 0.05 vs. WT (*) and vs. treatment groups (#). B: sample traces of calcium transient were recorded in WT and HHCY mice myocytes. A superimposed calcium transient trace is presented. Data were analyzed offline with IonWizard software from IonOptix.

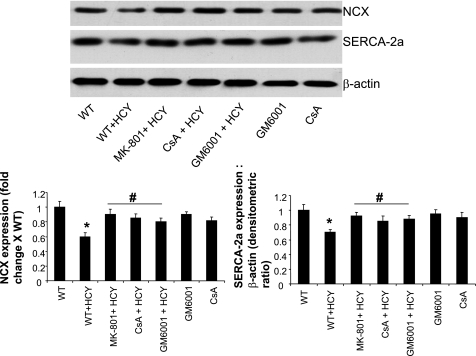

The disturbances in calcium transient by HCY suggest the alteration in calcium-handling proteins, including the possible role of SERCA-2a, phospholamban, and NCX. In the present study, the expression of SERCA-2a and NCX was determined. It was observed that HCY caused downregulation of SERCA- 2a and NCX expression (Fig. 6). Moreover, the HCY-induced downregulation of SERCA-2a and NCX was attenuated by the treatment with MK-801, GM-6001, and CsA, suggesting the role of MMP and MPT in the regulation of calcium-handling proteins in HHCY.

Fig. 6.

HCY alters the expression of calcium-handling proteins. A representative Western blot for myocyte sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase-2a pump (SERCA-2a) and sodium calcium exchanger (NCX) is shown. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Bar graphs are representative of 3 different experiments. P < 0.05 compared with experimental control (*) and compared with the treatment groups (#).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have documented the pathological role of HHCY on the vasculature and suggested a strong correlation between HHCY and heart failure (22, 15). HCY induces fibrosis and causes systolic/diastolic dysfunction. However, the direct impact of HHCY on the cardiomyocytes and its physiological consequences remains to be elucidated.

In the present study, we demonstrate that HHCY increases NMDA-R1 expression in the ventricular myocytes. HHCY causes the activation of MMP in the myocyte mitochondria and induces MPT. HHCY decreases myocyte contractility and alters calcium transients, in part by, decreasing the expression of calcium-handling proteins SERCA-2a and NCX. These observations unequivocally support the notion that HHCY activates MMP in the myocyte mitochondria and induces MPT, leading to the decline in myocyte contractility, in part, by agonizing NMDA-R1.

Recently it is shown that the activation of NMDA-R increases oxidative stress and calcium load in the mitochondria, leading to the death of cardiomyocyte (11). However, the role of HHCY on the myocyte NMDA receptor and the physiological consequences is to be elucidated. This prompted us to speculate that HCY acts as a ligand for NMDA-R1; furthermore, the activation of NMDA-R1 instigates mitochondrial damage, leading to cardiomyocyte dysfunction. In the present study, we demonstrate that HCY increases myocyte NMDA-R1 expression.

It is known that MMP activation in HHCY increases the deposition of interstitial collagen between endothelium and myocytes and is arrhythmogenic (27, 32, 30). Furthermore, NMDA-R antagonist inhibits MMP activation (21). We and others have reported the presence of MMP in mtMMP; however, the functional consequences of the intracellular MMP activation remain obscure (23, 17, 18). Myocyte MMP is shown to be colocalized with troponin I within the myofilaments (33). In the present study, we for the first time have reported that HHCY increases MMP-9 expression by agonizing NMDA-R1 in the myocyte mitochondria, which may be attributed to the increase in oxidative stress and calcium load in the mitochondria.

A recent study suggested that the overexpression of MMP-2 causes mitochondrial dysfunction by degrading the mitochondrial membrane potential (36). HHCY is well associated with the mitochondrial abnormalities. We presented the evidence that HHCY causes MPT by agonizing NMDA-R1 and is attributed to the induction of MMP in the myocyte mitochondria. This is consistent with our earlier finding that HCY-induced calpain (calcium-dependent cysteine protease) activation induces MPT by agonizing NMDA-R1 in HL-1 cardiomyocytes (23). Furthermore, how the induction of MMP in the mitochondria leads to an increase in MPT is to be elucidated. It is known that intact mitochondrial connexin 43 preserves mitochondrial permeability transition pore MPT in the closed state and hence is cardioprotective. Based on our unpublished findings, it can be suggested that MMP activation in the mitochondria disrupts mitochondrial connexin 43 protein leading to MPT. However, the functional consequences of MMP activation in the myocyte mitochondria and MPT induction in HHCY are not understood. Here we report for the first time that HHCY causes a decline in myocyte mechanical properties by agonizing NMDA-R1 and involves MPT. This may be attributed to the myocyte calcium overloading that can contribute to ATP depletion by activation of calcium-dependent ATPases and by induction of the MPT leading to the myocyte dysfunction (3).

In the present study, we have shown that in HHCY the calcium clearance rate was slower, which was reflected by a decrease in the expression of calcium-handling proteins SERCA-2a and NCX. These events may have overloaded the myocyte with calcium, which depleted ATP by the induction of MPT leading to the decline in myocyte contractility.

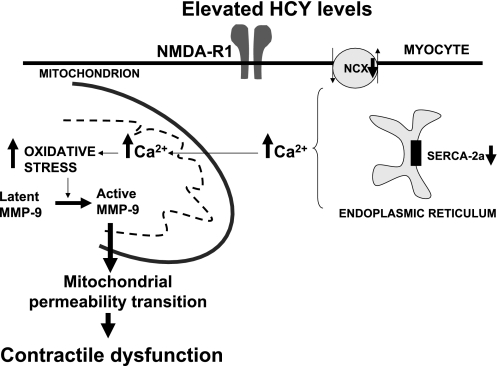

The results from this study suggest that HHCY increases MMP expression in the myocyte mitochondria, alters calcium homeostasis, and induces MPT, leading to the decline in myocyte contractility by agonizing NMDA-R1 (Fig. 7). Future studies will be directed toward understanding the mechanism how the induction of MPT in HHCY leads to myocyte dysfunction.

Fig. 7.

Schematic presentation of hypothesis. The elevated levels of HCY activate MMP in the mitochondria and induce mitochondrial permeability transition, leading to the decline in myocyte mechanical function.

GRANTS

This research was supported by American Heart Association Postdoctoral Training Grant No. 0625579B (to K. S. Moshal) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-71010, HL-74185, and HL-88012 (to S. C. Tyagi).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert CM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Ridker PM. Prospective study of C-reactive protein, Hcy and plasma lipid levels as predictors of SCD. Circulation 105: 2595–2599, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballou RJ, Simpson WG, Tseng MT. A convenient method for in situ processing of cultured cells for cytochemical localization by electron microscopy. J Pathol 147: 223–226, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry WH Na “Fuzzy space”: does it exist, and is it important in ischemic injury? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 17: S43–S46, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollani G, Ferrari R, Bersatti F, Ferrari M, Cattaneo M, Zighetti MI, Visioli O, Sanelli D. A hyperhomocysteinemia study in a population with a familial factor for acute MI and SCD at a young age. Cardiologia 44: 75–81, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke AP, Fonseca V, Kolodgie F, Zieske A, Fink L, Virmani R. Increased serum Hcy and SCD resulting from coronary atherosclerosis with fibrous plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 1936–1941, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colucci WS, Braunwald E. Path physiology of heart failure. In: Heart Disease (6th ed.), edited by E. Braunwald, D. P. Zipes, and P. Libby. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2001, p. 517–518.

- 7.Cui G, Esmailian F, Plunkett M, Marelli D, Ardehali A, Odim J, Laks H, Sen L. Atrial extracellular matrix remodeling and the maintenance of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 109: 363–368, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Amico M, Filippo C, Di Rossi F. Arrhythmias induced by myocardial ischemia-reperfusion are sensitive to ionotrophic excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists. Euro J Pharmacol 366: 167–174, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMicco J, Monroe AJ. Stimulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the dorsomedial hypothalamus elevate heart rate in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H1115–H1121, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folbergrova J NMDA and not non-NMDA receptor antagonists are protective against seizures induced by homocysteine in neonatal rats. Exp Neurol 130: 344–350, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao X, Xu XB, Pang J, Zhang C, Ding JM, Peng X, Liu Y, Cao JM. NMDA receptor activation induces mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and apoptosis in cultured neonatal rat cardio. Physiol Res 56: 559–569, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrmann M, Kindermann I, Müller S, Georg T, Kindermann M, Böhm M, Herrmann W. Relationship of plasma homocysteine with the severity of chronic heart failure. Clin Chem 51: 1512–1515, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann W, Herrmann M, Joseph J, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine, brain natriuretic peptide and chronic heart failure: a critical review. Clin Chem Lab Med 45: 1633–1644, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoit BD, Takeishi Y, Cox MJ, Gabel M, Kirkpatrick D, Walsh RA, Tyagi SC. Remodeling of the left atrium in pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem 238: 145–150, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph J, Joseph L, Shekhawat NS, Devi S, Wang J, Melchert RB, Hauer-Jensen M, Kennedy RH. Hyperhomocysteinemia leads to pathological ventricular hypertrophy in normotensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H679–H686, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YF, Cornish KG, Patel KP. Alteration of NMDA NR[1] receptors within the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus in rats with heart failure. Circ Res 93: 990–997, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limb GA, Matter K, Murphy G, Cambrey AD, Bishop PN, Morris GE, Khaw PT. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 associates with intracellular organelles and confers resistance to lamin A/C degradation during apoptosis. Am J Pathol 166: 1555–1563, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma YS, Chen YC, Lu CY, Liu CY, Wei YH. Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 1 and disruption of mitochondrial network in skin fibroblasts of patients with MERRF syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci 1042: 55–63, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuoka N, Kodama H, Arakawa H, Yamaguchi I. NMDA receptor blockade by dizocilpine prevents stress-induced sudden death in cardiomyopathic hamsters. Brain Res 944: 200–204, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCawley LJ, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: they're not just for matrix anymore! Curr Opin Cell Biol 13: 534–40, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meighan SE, Meighan PC, Choudhury P. Effects of ECM-degrading proteases MMP-3 and -9 on spatial learning and synaptic plasticity. J Neurochem 96: 1227–1241, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller A, Mujumdar V, Palmer L, Bower JD, Tyagi SC. Reversal of endocardial endothelial dysfunction by folic acid in homocysteinemic hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 15: 157–163, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moshal KS, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC. Mitochondrial matrix metalloproteinase activation and dysfunction in hyperhomocysteinemia. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 6: 84–92, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukherjee R, Herron AR, Lowry AS, Stroud RE, Stroud MR, Wharton JM, Ikonomidis JS, Crumbley 3rd AJ, Spinale FG, Gold MR. Selective induction of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases in atrial and ventricular myocardium in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 97: 532–537, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson KK, Melendez JA. Mitochondrial redox control of matrix metalloproteinases. Free Rad Biol Med 37: 768–784, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodrigues T, Santos AC, Pigoso AA, Mingatto FE, Uyemura SA, Curti C. Thioridazine interacts with the membrane of mitochondria acquiring antioxidant activity toward apoptosis–potentially implicated mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 136: 136–142, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rucklidge GJ, Milne G, McGaw BA, Milne E, Robins SP. Turnover rates of different collagen types measured by isotope ratio mass spectrometery. Biochim Biophys Acta 11: 1156–1157, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz R Intracellular targets of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in cardiac disease: rationale and therapeutic approaches, Annu. Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47: 211–242, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh K, Communal C, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS. Adrenergic regulation of myocardial apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res 45: 713–719, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sood HS, Cox MJ, Tyagi SC. Generation of nitrotyrosine precedes the activation of matrix metalloproteinase in left ventricle of hyperhomocystenemia rats. Antioxidant Redox Signal 4: 799–804, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swynghedauw B Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol Rev 79: 215–262, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tyagi SC, Meyer L, Schmaltz RA, Reddy HK, Voelker DJ. Proteinases and restenosis in human coronary artery: extracellular matrix production exceeds the expression of proteolytic activity. Atherosclerosis 116: 43–57, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasan RS, Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Wilson PW. Plasma homocysteine and risk for congestive heart failure in adults without prior myocardial infarction. JAMA 289: 1251–1257, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Schulze CJ, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Dyck JR, Sawicki G, Schulz R. Intracellular action of matrix metalloproteinase-2 accounts for acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Circulation 106: 1543–1549, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye G, Metreveli NS, Donthi RV, Xia S, Xu M, Carlson EC, Epstein PN. Catalase protects cardiomyocyte function in models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53: 1336–1343, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou HZ, Ma X, Gray MO, Zhu BQ, Nguyen AP, Baker AJ, Simonis U, Cecchini G, Lovett DH, Karliner JS. Transgenic MMP-2 expression induces latent cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358: 189–195, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]