Abstract

Here, we describe for the first time the prevalence and genetic properties of Bartonella organisms in wild rodents in Japan. We captured 685 wild rodents throughout Japan (in 12 prefectures) and successfully isolated Bartonella organisms from 176 of the 685 rodents (isolation rate, 25.7%). Those Bartonella isolates were all obtained from the rodents captured in suburban areas (rate, 51.8%), but no organism was isolated from the animals captured in city areas. Sequence analysis of rpoB and gltA revealed that the Bartonella isolates obtained were classified into eight genetic groups, comprising isolates closely related to B. grahamii (A-I group), B. tribocorum and B. elizabethae (B-J group), B. tribocorum and B. rattimassiliensis (C-K group), B. rattimassiliensis (D-L group), B. phoceensis (F-N group), B. taylorii (G-O group), and probably two additional novel Bartonella species groups (E-M and H-P). B. grahamii, which is one of the potential causative agents of human neuroretinitis, was found to be predominant in Japanese rodents. In terms of the relationships between these Bartonella genetic groups and their rodent species, (i) the A-I, E-M, and H-P groups appear to be associated with Apodemus speciosus and Apodemus argenteus; (ii) the C-K, D-L, and F-N groups are likely implicated in Rattus rattus; (iii) the B-J group seems to be involved in Apodemus mice and R. rattus; and (iv) the G-O group is probably associated with A. speciosus and Clethrionomys voles. Furthermore, dual infections with two different genetic groups of bartonellae were found in A. speciosus and R. rattus. These findings suggest that the rodent in Japan might serve as a reservoir of zoonotic Bartonella infection.

The genus Bartonella is associated with aerobic, fastidious, gram-negative, slow-growing bacteria and consists of 20 species and three subspecies at the present time (19). These microorganisms infect the erythrocytes of their mammalian hosts, and some species cause a wide spectrum of illness, such as chronic bacteremia, fever, and endocarditis. In particular, B. bacilliformis, B. henselae, and B. quintana are known to be causative agents of Carrion's disease, cat scratch disease, and trench fever, respectively, in humans (1, 27, 32). Because of the difficulty in identifying Bartonella species by use of conventional biochemical tests, molecular approaches by PCR, followed by sequencing of several housekeeping genes, such as citrate synthase (gltA), RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB), cell division-associated protein (ftsZ), heat shock protein (groEL), riboflavin synthase alpha chain (ribC), and 16S rRNA genes, as targets, have been useful for identification of Bartonella species (26). Particularly, rpoB and gltA have been well used for differentiating Bartonella species because of the much lower degrees of similarity between these genes in Bartonella species (26). Furthermore, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) has also been applied as a simple and rapid method to identify and/or classify many microorganisms, including Bartonella species (30).

A number of studies have shown that Bartonella species are widely distributed in wild rodents in many countries, such as the United Kingdom (4, 5), the United States (10, 19, 24), Sweden (18), China (37), Greece (33), Denmark (13), France (16), Canada (20), and the Republic of South Africa (29). Ten species and two subspecies of Bartonella, i.e., B. birtlesii (3), B. doshiae (5), B. elizabethae (12), B. grahamii (5), B. phoceensis (16), B. rattimassiliensis (16), B. taylorii (5), B. tribocorum (17), B. washoensis (23), B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis, and B. vinsonii subsp. vinsonii (2, 35), have been previously isolated from wild rodent origins. Of these, four rodent-associated Bartonella species are thought to be implicated in human infections, with B. elizabethae responsible for endocarditis (11), B. grahamii for neuroretinitis (21), B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis for bacteremia, fever, and endocarditis (15, 35), and B. washoensis for cardiac disease (23). Although environmental surveillance is required for control of infectious diseases, including zoonoses, there is no information on the prevalence and genetic characteristics of Bartonella organisms in wild rodents in Japan so far. Therefore, the aim of this study is to clarify the distribution of Bartonella organisms in Japan by isolation from wild rodents collected in 16 suburban or city areas and to characterize the Bartonella isolates by molecular techniques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood sampling.

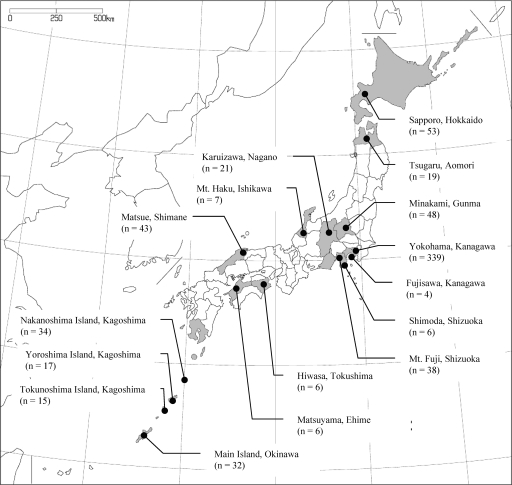

From October 1997 to May 2006, wild rodents were captured using Sherman traps in the 12 prefectures of Hokkaido, Aomori, Gunma, Kanagawa, Shizuoka, Ishikawa, Nagano, Shimane, Tokushima, Ehime, Kagoshima, and Okinawa in Japan (Fig. 1). Blood was aseptically collected from each animal and immediately placed into sterile 1.5-ml conical plastic tubes with heparin. The blood samples were sent to the Laboratory of Veterinary Public Health, Department of Veterinary Medicine, College of Bioresource Sciences, Nihon University, under frozen conditions with dry ice and were kept at −80°C until use.

FIG. 1.

Geographical representation of the locations where wild rodents were captured. Cities, areas, or islands and their prefectures (e.g., Yokohama [city], Kanagawa [Prefecture]) are shown around the map of Japan in the figure. The numbers of rodents captured are indicated in parentheses.

Isolation of bacteria.

The frozen blood samples were thawed at room temperature, and a 100-μl sample of each was plated on heart infusion agar plates (Difco, MI) containing 5% defibrinated rabbit blood (24). The plates were incubated at 35°C under 5% CO2 for 2 weeks. Small, rough gray colonies that required long culture periods (1 week or more) were selected. By Gram staining, we considered the microorganisms that were small, gram negative, and had bacillus shapes as Bartonella species. For pure culture, two or three colonies were picked from each plate, streaked out on fresh plates, and further cultured under the same conditions. The Bartonella isolates obtained were used for the following experiments.

PCR amplification of rpoB and gltA.

Genomic DNA was extracted from each isolate of bartonellae by using an Instagene matrix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The primers used for the amplification of rpoB (893 bp) were 1400F (5′-CGCATTGGCTTACTTCGTATG-3′) and 2300R (5′-GTAGACTGATTAGAACGCTG-3′) (30), and the primers for gltA (379 bp) were BhCS.781p (5′-GGGGACCAGCTCATGGTGG-3′) and BhCS.1137n (5′-AATGCAAAAAGAACAGTAAACA-3′) (28). The PCR was performed with 20-μl mixtures containing 20 ng of the extracted DNA, 200 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), and 1 pmol of each primer. The PCR cycle conditions were as described previously (28, 30).

PCR-RFLP of rpoB.

The PCR-amplified rpoB genes of the Bartonella isolates obtained from individual rodents were purified using a commercial purification kit (Spin Column PCR product purification kit; Bio Basic, Ontario, Canada). A 10-μl sample of the purified PCR products was mixed with 2 μl 10× B buffer and 5 U AcsI (identical to ApoI) restriction endonuclease (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany) (30), and the total volume was adjusted to 20 μl with double-distilled water. After incubation for 2 h at 50°C, the digestion products were separated on 3% agarose gels by electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of rpoB and gltA.

The PCR products of rpoB and gltA from individual Bartonella isolates were sequenced with specific primers for rpoB (1400F and 2300R, whose sequences are given above, and 1600R [5′-GGRCAAATACGACCATAATGSG-3′], 2000R [5′-CGYGGYRCCATRAAAACTTCWCC-3′], and 2000F [5′-GGWGAAGTTTTRATGGYRCCRCG-3′]) and for gltA (BhCS.781p and BhCS.1137n, whose sequences are given above), using an Applied Biosystems model 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The CLUSTAL_X program (34) was used for the alignment of Japanese Bartonella sequences obtained in this study with those of known Bartonella species deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases. A phylogenetic tree was drawn based on the sequences of rpoB (825 bp) and gltA (312 bp), using the neighbor-joining method with Kimura's two-parameter distance method in MEGA 3.1 (22, 25, 31). Bootstrap analysis was carried out with 1,000 resamplings (14).

RESULTS

Isolation and distribution of bartonellae in wild rodents in Japan.

From 1997 to 2006, a total of 685 wild rodents were collected in 16 areas of 12 prefectures throughout Japan, and the numbers of rodents captured in each area are shown in Fig. 1. The species of rodents obtained were Apodemus speciosus (a large Japanese field mouse; n = 224), A. argenteus (a small Japanese field mouse; n = 35), Clethrionomys rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae (a gray red-backed vole; n = 17), Mus caroli (a Ryukyu mouse; n = 7), Rattus rattus (a roof rat; n = 297), and R. norvegicus (a brown rat; n = 105). By isolation of Bartonella organisms from blood samples of those rodents, we eventually obtained Bartonella isolates from 176 of 685 rodents (25.7%) (Table 1). The isolation rate of bartonellae in suburban areas was 51.8% (176/340), but no Bartonella isolate was obtained from any rodents in either of the two city areas (0/345), Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Shimoda, Shizuoka Prefecture. The isolation rates ranged from 6.3% to 100% in the 12 prefectures of Japan, although the numbers of rodents captured in some areas were small. The areas with the highest isolation rates (>80%) were Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture (100% [4/4]), Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture (83.3% [5/6]), and Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture (81.0% [17/21]), and those with the lowest rates (<20%) were the main island of Okinawa Prefecture (6.3% [2/32]) and Matsue, Shimane Prefecture (18.6% [8/43]). Among rodent species, the isolation rates of bartonellae were 60.3% (135/224) for A. speciosus, 54.3% (19/35) for A. argenteus, 23.5% (4/17) for C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae, and 6.1% (18/297) for R. rattus. These results suggest that Bartonella organisms are widely distributed in wild rodents inhabiting suburban areas throughout Japan.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of Japanese Bartonella organisms in wild rodents

| Environment | Prefecture | Area | No. of bartonella-infected rodents/no. of rodents examined (isolation rate [%])

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. speciosus | A. argenteus | C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae | M. caroli | R. rattus | R. norvegicus | Subtotal | Total | |||

| Suburban | Hokkaido | Sapporo | 29/31 (93.5) | 3/5 (60.0) | 4/17 (23.5) | 36/53 (67.9) | ||||

| Aomori | Tsugaru | 11/17 (64.7) | 1/2 (50.0) | 12/19 (63.2) | ||||||

| Gunma | Minakami | 26/43 (60.5) | 3/5 (60.0) | 29/48 (60.4) | ||||||

| Kanagawa | Fujisawa | 1/1 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 4/4 (100) | ||||||

| Shizuoka | Mt. Fuji | 13/21 (61.9) | 8/17 (47.1) | 21/38 (55.3) | ||||||

| Ishikawa | Mt. Haku | 2/7 (28.6) | 2/7 (28.6) | |||||||

| Nagano | Karuizawa | 16/20 (80.0) | 1/1 (100) | 17/21 (81.0) | ||||||

| Shimane | Matsue | 8/40 (20.0) | 0/2 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 8/43 (18.6) | |||||

| Tokushima | Hiwasa | 2/6 (33.3) | 2/6 (33.3) | |||||||

| Ehime | Matsuyama | 5/6 (83.3) | 5/6 (83.3) | |||||||

| Kagoshima | Nakanoshima Island | 22/30 (73.3) | 2/4 (50.0) | 24/34 (70.6) | ||||||

| Kagoshima | Yoroshima Island | 10/17 (58.8) | 10/17 (58.8) | |||||||

| Kagoshima | Tokunoshima Island | 4/12 (33.3) | 4/12 (33.3) | |||||||

| Okinawa | Main Island | 0/7 (0.0) | 2/6 (33.3) | 0/19 (0.0) | 2/32 (6.3) | 176/340 (51.8) | ||||

| City | Kanagawa | Yokohama | 0/255 (0.0) | 0/84 (0.0) | 0/339 (0.0) | |||||

| Shizuoka | Shimoda | 0/2 (0.0) | 0/3 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/6 (0.0) | 0/345 (0.0) | ||||

| Total | 135/224 (60.3) | 19/35 (54.3) | 4/17 (23.5) | 0/7 (0.0) | 18/297 (6.1) | 0/105 (0.0) | 176/685 (25.7) | |||

Genetic characterization of Japanese Bartonella isolates in wild rodents.

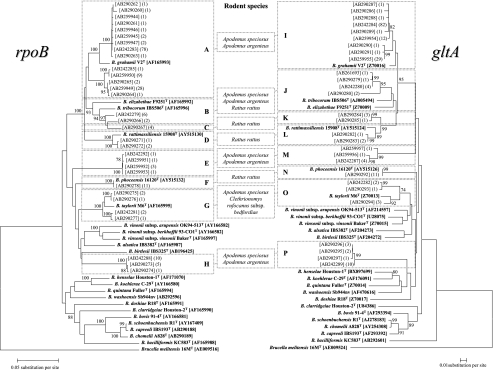

To characterize the Bartonella isolates, we first performed a comparative analysis of the RFLP patterns of the AcsI restriction enzyme-digested rpoB genes amplified. For each Bartonella culture obtained from the blood of a rodent, two or three bacterial colonies were tested. By PCR-RFLP analysis, for 169 out of the 176 rodents, the two or three isolates from each rodent were found to have identical PCR-RFLP patterns. However, three isolates from each rodent among the remaining seven animals had two different PCR-RFLP patterns, suggesting multiple infections as described below (RFLP data not shown). Therefore, we eventually obtained a total of 183 Bartonella isolates which have distinguishable PCR-RFLP patterns. To further characterize the 183 Bartonella isolates with different RFLP patterns, we sequenced all of the rpoB (825-bp) and gltA (312-bp) genes amplified from the 183 isolates. By this sequencing, we found that the 183 isolates have 31 and 28 different sequences of rpoB and gltA, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis based on the sequence similarities revealed that those isolates with different sequences were further classified into eight clusters, designated A to H for rpoB and I to P for gltA (Fig. 2). Each cluster for rpoB was correlated with one of the clusters for gltA. All Bartonella isolates seem to follow a pattern in which, e.g., the isolates in cluster A of rpoB also belongs to cluster I of gltA (designated the A-I genetic group), and idem for B-J, C-K, D-L, E-M, F-N, G-O, and H-P (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic classification of Japanese Bartonella isolates based on sequences of rpoB (left) and gltA (right). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method, and bootstrap values were obtained with 1,000 replicates. Only bootstrap replicates of >70% are noted. The 31 and 29 different sequences of rpoB and gltA, respectively, from Japanese Bartonella isolates were classified into eight clusters, A to H for rpoB and I to P for gltA. Based on the correlation between respective clusters in rpoB and gltA, combinations of clusters such as A-I, B-J, C-K, D-L, E-M, F-N, G-O, and H-P were assigned as Bartonella genetic groups. The numbers of Bartonella isolates with identical DNA sequences are shown in parentheses at the right and left of the respective GenBank accession numbers for the rpoB and gltA sequences, respectively. The rodent species associated with the respective Bartonella genetic groups are shown between the two trees. The rpoB and gltA sequences from Brucella melitensis 16 MT were used as an outgroup bacterium.

The closest relatives of the respective Bartonella isolates and the relationships between the organisms and their host species are shown in Table 2. The Bartonella isolates in the A-I genetic group had sequence similarities of 94.7 to 97.3% for rpoB and 96.8 to 98.4% for gltA with respect to B. grahamii V2T (the closest relative). The sequences also showed similarities of 98.3% for rpoB and 97.1 to 97.4% for gltA between the isolates of the D-L genetic group and B. rattimassiliensis 15908T, 100% for rpoB and 100% for gltA between the isolates of the F-N group and B. phoceensis 16120T, and 97.1 to 98.1% for rpoB and 94.1 to 97.0% for gltA between the isolates of the G-O group and B. taylorii M6T. With respect to rpoB, the isolates of groups B and C seem to be closely related to each other, and these isolates had high similarities to B. tribocorum IBS506T (95.0 to 96.4% and 95.9%, respectively). However, with respect to gltA, the corresponding groups J and K were clearly clustered, and their closest relatives seem to be different, i.e., B. tribocorum IBS506T (93.6 to 96.5%) for group J and B. rattimassiliensis 15908T (96.2 to 96.5%) for group K. Accordingly, in the case of genetic group C-K (for both rpoB and gltA), the isolates had the highest similarities to B. tribocorum IBS506T (95.9%) with respect to rpoB, while for gltA, they had higher similarities to B. rattimassiliensis 15908T (96.2 to 96.5%) than to B. tribocorum IBS506T (93.6 to 96.5%). In the case of genetic groups E-M and H-P, the isolates from A. speciosus and A. argenteus in both groups showed the highest levels of similarity to B. alsatica, with only <90.1% and <91.4% for rpoB. With respect to gltA, the isolates of genetic groups E-M and H-P also showed the highest levels of similarity to B. grahamii and B. vinsonii subsp. arupensis, with only <91.0% and 89.1%, respectively. These low degrees of similarity of the isolates to any known Bartonella species suggest that the isolates of these genetic groups may be new species.

TABLE 2.

Closest relatives of Japanese Bartonella isolates and relationships between organisms and their host species based on sequence analysis of rpoB and gltA

| Genetic group | Closest relativea | % similarities to rpoB and gltA | No. of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. speciosus | A. argenteus | C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae | R. rattus | Total | |||

| A-I | B. grahamii | 94.7-97.3, 96.8-98.4 | 116 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 129 |

| B-J | B. tribocorum | 95.0-96.4, 93.6-96.5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| B. elizabethae | 93.8-94.4, 92.6-94.2 | ||||||

| C-K | B. tribocorum | 95.9, 92.6-92.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| B. rattimassiliensis | 91.2, 96.2-96.5 | ||||||

| D-L | B. rattimassiliensis | 98.3, 97.1-97.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| E-M | NA | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| F-N | B. phoceensis | 100, 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| G-O | B. taylorii | 97.1-98.1, 94.1-97.0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| H-P | NA | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 16 | |

| Total | 140 | 19 | 4 | 20 | 183 | ||

NA, not applicable.

Among rodent species, (i) A. speciosus and A. argenteus mice were infected with bartonellae belonging to genetic groups A-I, B-J, E-M, G-O, and H-P; (ii) C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae voles were infected only with bartonellae of the G-O group; and (iii) R. rattus rats were infected with bartonellae belonging to groups B-J, C-K, D-L, and F-N.

Among the genetic groups of Bartonella isolates, (i) the A-I, E-M, and H-P groups were obtained only from Apodemus mice, such as A. speciosus and A. argenteus; (ii) the C-K, D-L, and F-N groups were obtained only from R. rattus; (iii) the G-O group was isolated from two different host species, A. speciosus and C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae; and (iv) the B-J group was obtained from two different host genera, including three species, A. speciosus, A. argenteus, and R. rattus (Fig. 2). These results suggest that there is some animal host specificity among Bartonella species, e.g., Apodemus mice for genetic groups A-I, E-M, and H-P and Rattus rats for C-K, D-L, and F-N (Table 2).

Additionally, as described in the above section on PCR-RFLP analysis, we detected two different RFLP patterns of rpoB in two or three Bartonella isolates obtained from a single rodent out of seven wild rodents. Sequencing of the rpoB and gltA genes amplified from those isolates with different RFLP patterns revealed that five A. speciosus mice among the seven animals were infected with the A-I group and either the E-M, the B-J, or the H-P group and that the remaining two rodents (both R. rattus rats) were infected with the B-J group and either the F-N or the D-L group, showing dual infection with two different genetic groups of bartonellae ( Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Dual infection with two different Bartonella genetic groups in wild rodents

| Rodent no. | Prefecture | Area | Rodent species | Details of dual infection

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic group | Closest relative(s) | GenBank accession no. for identical rpoB and gltA sequences | Genetic group | Closest relative(s)a | GenBank accession no. for identical rpoB and gltA sequences | ||||

| 1 | Aomori | Tsugaru | A. speciosus | A-I | B. grahamii | AB259944, AB242284 | E-M | NA | AB259953, AB259956 |

| 2 | Aomori | Tsugaru | A. speciosus | A-I | B. grahamii | AB259946, AB242284 | B-J | B. tribocorum, B. elizabethae | AB242279, AB261693 |

| 3 | Shimane | Matsue | A. speciosus | A-I | B. grahamii | AB242283, AB242284 | E-M | NA | AB259952, AB242287 |

| 4 | Kagoshima | Nakanoshima | A. speciosus | A-I | B. grahamii | AB259949, AB259955 | H-P | NA | AB290273, AB290295 |

| 5 | Kagoshima | Nakanoshima | A. speciosus | A-I | B. grahamii | AB259949, AB259955 | H-P | NA | AB290273, AB290296 |

| 6 | Kagoshima | Yoroshima | R. rattus | B-J | B. tribocorum, B. elizabethae | AB290270, AB290281 | F-N | B. phoceensis | AB290278, AB290292 |

| 7 | Okinawa | Main Island | R. rattus | B-J | B. tribocorum, B. elizabethae | AB290266, AB290280 | D-L | B. rattimassiliensis | AB290272, AB290283 |

NA, not applicable.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated for the first time the prevalence of Bartonella organisms in wild rodents in Japan and characterized the genetic properties of those Bartonella isolates. The overall prevalence of Bartonella infection in wild rodents was found to be 25.7% (176/685) in this study. Previous reports for other countries have shown that the prevalences of bartonellae in wild rodents ranged from 8.7%, in the northern part of Thailand (8), to 62.2%, in Shropshire County, United Kingdom (4). Our result (25.7%) was similar to the percent range for Greece, 30.0% (33). The prevalences of Bartonella organisms isolated from the rodents captured in the three prefectures of Kanagawa, Nagano, and Ehime are considerably high (>80%), whereas the prevalences for two prefectures of Shimane and Okinawa seem to be low (<20%). Furthermore, the rodents inhabiting suburban regions appear to be predominantly infected with Bartonella organisms (prevalence, 51.8% [176/340]), but the rodents living in city areas are likely to be bartonella free (0/345). Among rodent species, A. speciosus, A. argenteus, C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae, and R. rattus rodents captured in suburban areas were highly infected with Bartonella organisms, suggesting that those rodents might be major reservoirs of those Bartonella species in Japan. However, no bartonellae were isolated from M. caroli or R. norvegicus, although the number of M. caroli mice examined was small (n = 7) in this study. The reasons why the prevalences of Bartonella infection varied among several locations or among different rodent species in Japan are likely to depend on the distribution of reservoirs or arthropod vectors, such as fleas, and/or to depend on host specificities due to differences in reservoirs or vector species. However, we do not know why rodents living in city areas did not harbor any Bartonella species, even though arthropod vectors are probably present in city areas. At least, we could not find any blood-suckling arthropod vectors in the rodents captured in the city areas in this study (data not shown).

Previously, La Scola et al. proposed sequence similarities to rpoB and gltA for validation of species, i.e., when the sequence similarities to rpoB and gltA are neither below 95.4% nor below 96.0%, respectively, those isolates can be considered members of the same species (26). According to the criteria, the genetic groups D-L and F-N in this study probably belong to the Bartonella species B. rattimassiliensis and B. phoceensis, respectively. All of the other genetic groups include some isolates below the cutoff value of rpoB or gltA, but some fulfill the species criteria. In this case, we used genetic groups for classification of the isolates in this study.

Bartonella isolates belonging to the A-I genetic group, which is closely related to B. grahamii, known as a potential causative agent of neuroretinitis in humans (21), were obtained from Apodemus mice, and these isolates appear to be dominant in Japanese wild rodents, suggesting the possibility of the risk of human exposures. Previously, it was reported that B. grahamii infects several wild rodents, such as members of the genera Clethrionomys, Apodemus (A. speciosus and A. argenteus in this study), Microtus, Dryomys, and Mus, in many other countries, including the United Kingdom (4), Sweden (18), Denmark (13), China (37), Canada (20), and Greece (33). This may show the wide host range and the global distribution of B. grahamii-like organisms. The isolates of genetic groups E-M and H-P, which were obtained only from A. speciosus and A. argenteus, had low degrees of similarity to those of all known Bartonella species for rpoB (<91.4%) and gltA (<91.0%). This result strongly supports the idea that groups E-M and H-P are probably new species, although further biochemical and molecular analyses, such as determination of the activity of bacterial enzymes and DNA-DNA hybridization, may be required to combine those Bartonella organisms as new species.

R. rattus rats captured in suburban areas were found to be infected with several bartonellae, such as genetic groups C-K, D-L, and F-N, which were closely related to B. tribocorum, B. rattimassiliensis, and B. phoceensis, respectively. In contrast, no bartonellae were isolated from R. norvegicus rats living in city or suburban areas. This suggests that R. rattus rodents living in suburban areas may serve as a main reservoir for several Bartonella species in Japan. Previous studies in other countries have shown that wild rats, including the species R. norvegicus as well as R. rattus, are known to be reservoirs for B. phoceensis, B. rattimassiliensis, B. tribocorum, and B. elizabethae in France (16, 17), the United States (12), Portugal (12), and Indonesia (36); B. elizabethae, a causative agent of human endocarditis and neuroretinitis, is of particular public health significance (6, 11, 12). In this study, however, we did not isolate B. elizabethae from any wild rats in Japan, even though this Bartonella species has been commonly isolated from several rat species in the world (9, 12). The reason why B. elizabethae was not isolated in Japan is unknown. The organisms might not yet be distributed among wild rodents in Japan. To confirm whether B. elizabethae is absent in wild rats of Japan, further epidemiological and ecological studies will be needed.

The Bartonella isolates in the G-O genetic group, which is closely related to B. taylorii, were obtained from both A. speciosus and C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae in this study. B. taylorii had previously been isolated from several Apodemus spp. (A. speciosus in this study) and from C. glareorus in other countries, such as the United Kingdom (5, 7), Sweden (18), and Greece (33). In Japan, C. rufocanus subsp. bedfordiae seems to harbor only B. taylorii-like organisms, suggesting specificity between host species and some Bartonella species. However, Bartonella isolates in the B-J group, which is closely related to B. tribocorum and B. elizabethae, were obtained from several different species of wild rodents, such as A. speciosus, A. argenteus, and R. rattus, suggesting the wide host range of the bartonellae in Japan. In Bartonella-infected rodents, dual infection with two different genetic groups of bartonellae (including two possible new species) was observed only in A. speciosus and R. rattus, suggesting that these rodent species might be potential reservoirs harboring multiple Bartonella species. As mentioned above, our findings in this study may become a matter of public health significance with respect to Bartonella infection in Japan.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Gokuden, T. Honda, and T. Kuramoto (Kagoshima Prefecture Institute for Environment and Health); A. Itagaki and K. Tabara (Shimane Prefecture Institute of Health); Y. Yano (University of Fukui); R. Kondo, C. Toyoshima, K. Inari, and M. Ohseto (Ehime Prefecture Institute of Health); T. Yamauchi (University of Hiroshima); A. Takano (University of Gifu); N. Koizumi (National Institute of Infectious Diseases); F. Mahara (Mahara Hospital); F. Ishiguro (Fukui Prefecture Institute of Health); M. Inayoshi (Shizuoka Prefecture Institute of Health); A. Saito-Ito (University of Kobe); T. Ito and K. Kimura (Hokkaido Prefecture Institute of Health); F. Sato and M. Tsurumi (Yamashina Institute for Ornithology); and M. Takashi and H. Torikai (Amami Bird Banding Association) for providing blood samples of wild rodents.

This work was supported by a grant for the Academic Frontier project Surveillance and Control for Zoonoses from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autenrieth, I., and M. Haimerl. 1998. Human diseases—apart from cat-scratch disease, bacillary angiomatosis, and peliosis—and carriership related with Bartonella and Afipia species, p. 63-76. In A. Schmidt (ed.), Bartonella and Afipia species emphasizing Bartonella henselae, vol. 1. S. Karger AG, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker, J. A. 1946. A rickettsial infection of Canadian voles. J. Exp. Med. 84:37-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermond, D., R. Heller, F. Barrat, G. Delacour, C. Dehio, A. Alliot, H. Monteil, B. Chomel, H. J. Boulouis, and Y. Piemont. 2000. Bartonella birtlesii sp. nov., isolated from small mammals (Apodemus spp.). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1973-1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birtles, R. J., T. G. Harrison, and D. H. Molyneux. 1994. Grahamella in small woodland mammals in the U.K.: isolation, prevalence and host specificity. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 88:317-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birtles, R. J., T. G. Harrison, N. A. Saunders, and D. H. Molyneux. 1995. Proposals to unify the genera Grahamella and Bartonella, with descriptions of Bartonella talpae comb. nov., Bartonella peromysci comb. nov., and three new species, Bartonella grahamii sp. nov., Bartonella taylorii sp. nov., and Bartonella doshiae sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulouis, H. J., C. C. Chang, J. B. Henn, R. W. Kasten, and B. B. Chomel. 2005. Factors associated with the rapid emergence of zoonotic Bartonella infections. Vet. Res. 36:383-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bown, K. J., M. Bennet, and M. Begon. 2004. Flea-borne Bartonella grahamii and Bartonella taylorii in bank voles. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:684-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castle, K. T., M. Kosoy, K. Lerdthusnee, L. Phelan, Y. Bai, K. L. Gage, W. Leepitakrat, T. Monkanna, N. Khlaimanee, K. Chandranoi, J. W. Jones, and R. E. Coleman. 2004. Prevalence and diversity of Bartonella in rodents of northern Thailand: a comparison with Bartonella in rodents from southern China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70:429-433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Childs, J. E., B. A. Ellis, W. L. Nicholson, M. Kosoy, and J. W. Sumner. 1999. Shared vector-borne zoonoses of the Old World and New World: home grown or translocated? Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 129:1099-1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comer, J. A., T. Diaz, D. Vlahov, E. Monterroso, and J. E. Childs. 2001. Evidence of rodent-associated Bartonella and Rickettsia infections among intravenous drug users from Central and East Harlem, New York City. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:855-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly, J. S., M. G. Worthington, D. J. Brenner, C. W. Moss, D. G. Hollis, R. S. Weyant, A. G. Steigerwalt, R. E. Weaver, M. I. Daneshvar, and S. P. O'Connor. 1993. Rochalimaea elizabethae sp. nov. isolated from a patient with endocarditis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:872-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis, B. A., R. L. Regnery, L. Beati, F. Bacellar, M. Rood, G. G. Glass, E. Marston, T. G. Ksiazek, D. Jones, and J. E. Childs. 1999. Rats of the genus Rattus are reservoir hosts for pathogenic Bartonella species: an Old World origin for a New World disease? J. Infect. Dis. 180:220-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engbaek, K., and P. A. Lawson. 2004. Identification of Bartonella species in rodents, shrews and cats in Denmark: detection of two B. henselae variants, one in cats and the other in the long-tailed field mouse. APMIS 112:336-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenollar, F., S. Sire, and D. Raoult. 2005. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. arupensis as an agent of blood culture-negative endocarditis in a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:945-947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gundi, V. A., B. Davoust, A. Khamis, M. Boni, D. Raoult, and B. La Scola. 2004. Isolation of Bartonella rattimassiliensis sp. nov. and Bartonella phoceensis sp. nov. from European Rattus norvegicus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3816-3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heller, R., P. Riegel, Y. Hansmann, G. Delacour, D. Bermond, C. Dehio, F. Lamarque, H. Monteil, B. Chomel, and Y. Piemont. 1998. Bartonella tribocorum sp. nov., a new Bartonella species isolated from the blood of wild rats. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1333-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmberg, M., J. N. Mills, S. McGill, G. Benjamin, and B. A. Ellis. 2003. Bartonella infection in sylvatic small mammals of central Sweden. Epidemiol. Infect. 130:149-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iralu, J., Y. Bai, L. Crook, B. Tempest, G. Simpson, T. McKenzie, and F. Koster. 2006. Rodent-associated Bartonella febrile illness, southwestern United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1081-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jardine, C., G. Appleyard, M. Y. Kosoy, D. McColl, M. Chirino-Trejo, G. Wobeser, and F. A. Leighton. 2005. Rodent-associated Bartonella in Saskatchewan, Canada. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 5:402-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerkhoff, F. T., A. M. Bergmans, A. van der Zee, and A. Rothova. 1999. Demonstration of Bartonella grahamii DNA in ocular fluids of a patient with neuroretinitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:4034-4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosoy, M., M. Murray, R. D. Gilmore, Jr., Y. Bai, and K. L. Gage. 2003. Bartonella strains from ground squirrels are identical to Bartonella washoensis isolated from a human patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:645-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosoy, M. Y., R. L. Regnery, T. Tzianabos, E. L. Marston, D. C. Jones, D. Green, G. O. Maupin, J. G. Olson, and J. E. Childs. 1997. Distribution, diversity, and host specificity of Bartonella in rodents from the southeastern United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57:578-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Scola, B., Z. Zeaiter, A. Khamis, and D. Raoult. 2003. Gene-sequence-based criteria for species definition in bacteriology: the Bartonella paradigm. Trends Microbiol. 11:318-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loutit, J. S. 1997. Bartonella infections. Curr. Clin. Top. Infect. Dis. 17:269-290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norman, A. F., R. Regnery, P. Jameson, C. Greene, and D. C. Krause. 1995. Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1797-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pretorius, A. M., L. Beati, and R. J. Birtles. 2004. Diversity of bartonellae associated with small mammals inhabiting Free State province, South Africa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1959-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renesto, P., J. Gouvernet, M. Drancourt, V. Roux, and D. Raoult. 2001. Use of rpoB gene analysis for detection and identification of Bartonella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:430-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartzman, W. 1996. Bartonella (Rochalimaea) infections: beyond cat scratch. Annu. Rev. Med. 47:355-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tea, A., S. Alexiou-Daniel, A. Papoutsi, A. Papa, and A. Antoniadis. 2004. Bartonella species isolated from rodents, Greece. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:963-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Welch, D. F., K. C. Carroll, E. K. Hofmeister, D. H. Persing, D. A. Robison, A. G. Steigerwalt, and D. J. Brenner. 1999. Isolation of a new subspecies, Bartonella vinsonii subsp. arupensis, from a cattle rancher: identity with isolates found in conjunction with Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti among naturally infected mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2598-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winoto, I. L., H. Goethert, I. N. Ibrahim, I. Yuniherlina, C. Stoops, I. Susanti, W. Kania, J. D. Maguire, M. J. Bangs, S. R. Telford III, and C. Wongsrichanalai. 2005. Bartonella species in rodents and shrews in the greater Jakarta area. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 36:1523-1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying, B., M. Y. Kosoy, G. O. Maupin, K. R. Tsuchiya, and K. L. Gage. 2002. Genetic and ecologic characteristics of Bartonella communities in rodents in southern China. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66:622-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]