Abstract

Although many Lactobacillus strains used as probiotics are believed to modulate host immune responses, the molecular natures of the components of such probiotic microorganisms directly involved in immune modulation process are largely unknown. We aimed to assess the function of polysaccharide moiety of the cell wall of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota as a possible immune modulator which regulates cytokine production by macrophages. A gene survey of the genome sequence of L. casei Shirota hunted down a unique cluster of 10 genes, most of whose predicted amino acid sequences had similarities to various extents to known proteins involved in biosynthesis of extracellular or capsular polysaccharides from other lactic acid bacteria. Gene knockout mutants of eight genes from this cluster resulted in the loss of reactivity to L. casei Shirota-specific monoclonal antibody and extreme reduction of high-molecular-mass polysaccharides in the cell wall fraction, indicating that at least these genes are involved in biosynthesis of high-molecular-mass cell wall polysaccharides. By adding heat-killed mutant cells to mouse macrophage cell lines or to mouse spleen cells, the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-10, and IL-6 was more stimulated than by wild-type cells. In addition, these mutants additively enhanced lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-6 production by RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage-like cells, while wild-type cells significantly suppressed the IL-6 production of RAW 264.7. Collectively, these results indicate that this cluster of genes of L. casei Shirota, which have been named cps1A, cps1B, cps1C, cps1D, cps1E, cps1F, cps1G, and cps1J, determine the synthesis of the high-molecular-mass polysaccharide moiety of the L. casei Shirota cell wall and that this polysaccharide moiety is the relevant immune modulator which may function to reduce excessive immune reactions during the activation of macrophages by L. casei Shirota.

Lactic acid bacteria are industrially important microorganisms for fermented food production. Recent wide application of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria can be attributed to accumulating scientific evidence showing their beneficial effects on human health as probiotics. Immune modulation activities of some Lactobacillus strains in animal studies and in clinical situations are well documented (21, 27, 42), but the underlying mechanisms of these effects are not fully understood. There are several reports that indicate host immune responses to lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria, in which the involvement of various surface components of these bacteria are demonstrated (8, 12, 23, 25, 33, 43). Lactobacillus casei Shirota is one of the pioneer strains of probiotics, whose immune modulation activities have been studied extensively (9, 17, 23, 24, 35), and the contributions of lipoteichoic acid (23) and polysaccharide-peptidoglycan (PS-PG) complex (24) on its cell surface to immune stimulation and immune suppression activities have been suggested. However, the role and the function of cellular components often change their intrinsic functional properties once they are extracted from the original positions. In this respect, it is inevitably important to investigate the function of the cellular components by isolating isogenic mutants that are defective or additive in only one characteristic relative to the wild-type strain. For example, Grangette et al. (12) isolated Lactobacillus plantarum mutants defective in d-alanylation of teichoic acid and showed that the mutant strain gained the modification of its immune modulation activity on macrophages/monocytes.

We focused on the role of cell wall polysaccharides on the immune modulation activities of L. casei Shirota by isolating knockout mutants of the genes necessary for construction of the cell surface polysaccharide structure, since it has been suggested that PS-PG complex and PS itself have important roles for its immune modulation activities (24, 28, 34). In this study, we identified a cluster of genes from L. casei Shirota involved in the biosynthesis of cell wall PS and determined the immune modulation activities of the mutants defective in these genes on mouse macrophages and spleen cells in vitro. This report describes unique features of these genes and their contribution to the immune modulation activities of L. casei Shirota.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. casei strain Shirota YIT 9029 is a commercial strain used for the production of the probiotic drink Yakult and its related fermented milk drink products. L. casei ATCC 334 is the neotype strain of L. casei (10), which was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Escherichia coli JM109 was purchased from Toyobo Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), as competent cells for DNA transformation.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L casei | ||

| Shirota YIT 9029 | Wild type | Our collection |

| Ωcps1A | Insertion in cps1A gene | This study |

| Ωcps1B | Insertion in cps1B gene | This study |

| Δcps1C | Deletion in cps1C gene | This study |

| Ωcps1D | Insertion in cps1D gene | This study |

| Ωcps1E | Insertion in cps1E gene | This study |

| Ωcps1F | Insertion in cps1F gene | This study |

| Ωcps1G | Insertion in cps1G gene | This study |

| Ωcps1H | Insertion in cps1H gene | This study |

| Ωcps1I | Insertion in cps1I gene | This study |

| Ωcps1J | Insertion in cps1J gene | This study |

| Δcps1A | Deletion in cps1A gene | This study |

| Δcps1E | Deletion in cps1E gene | This study |

| Δcps1H | Deletion in cps1H gene | This study |

| Δcps1J | Deletion in cps1J gene | This study |

| Δcps1A/cps1A | Δcps1A carrying pYAP300-cps1A at attB site | This study |

| Δcps1C/cps1C | Δcps1C carrying pYAP300-cps1C at attB site | This study |

| ATCC 334 | L. casei neotype strain | ATCC |

| E. coli JM109 | Commercial strain purchased from Toyobo Co., Ltd. | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBE31 | Shuttle plasmid vector for E. coli and lactic acid bacteria carrying pUC19 ori region and pAMβ1 erythromycin resistance gene and ori region | 18 |

| pLP10 | Modified shuttle plasmid vector derived from pH4611 (18) carrying synthetic promoter sequence active in lactobacilli upstream of the multicloning site | This study |

| pYSSE3 | E. coli cloning vector carrying pUC19 ori region, pAMβ1 erythromycin resistance gene and multicloning sites | This study |

| pYAP300 | E. coli cloning vector carrying p15A ori region, pAMβ1 erythromycin resistance gene, phiFSW attP site and int, and multicloning site | This study |

| pdRA1 | pLP10 carrying deleted cps1C and its vicinity | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1A | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1A | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1B | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1B | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1D | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1D | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1E | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1E | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1F | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1F | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1G | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1G | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1H | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1H | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1I | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1I | This study |

| pYSSE-Ωcps1J | pYSSE3 carrying truncated fragment of cps1J | This study |

| pYAP-cps1A | pYAP300 carrying wild-type cps1A with its ribosome-binding site | This study |

| pYAP-cps1C | pYAP300 carrying wild-type cps1C with its ribosome-binding site | This study |

| pYSSE-Δcps1A | pYSSE3 carrying upstream region with N terminus of cps1A and downstream region with C terminus of cps1A | This study |

| pYSSE-Δcps1E | pYSSE3 carrying upstream region with N terminus of cps1E and downstream region with C terminus of cps1E | This study |

| pYSSE-Δcps1H | pYSSE3 carrying upstream region with N terminus of cps1H and downstream region with C terminus of cps1H | This study |

| pYSSE-Δcps1J | pYSSE3 carrying upstream region with N terminus of cps1J and downstream region with C terminus of cps1J | This study |

Reagents and chemicals for recombinant DNA technology.

DNA amplification by PCR was done by using KOD Plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) for DNA cloning and sequencing or by TaKaRa Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) for confirmation of the DNA structure. Restriction endonucleases, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase, and a DNA ligation kit were purchased from Takara Bio Co., Ltd., or Toyobo Co., Ltd. Plasmid purification was done by using the Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega K.K., Tokyo, Japan), and purification of DNA fragments amplified by PCR was done by using the Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen K.K., Tokyo, Japan). Erythromycin was purchased from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), and MRS medium was purchased from Nippon BD Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). E. coli JM109 was grown in LB broth (32). Custom-made synthetic DNAs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Japan K.K. (Tokyo, Japan).

Recombinant plasmid constructs for insertion and deletion mutagenesis.

Plasmid pLP10 was constructed by inserting a putative synthetic promoter sequence (5′-AATTCTTTAATATTTGACAAATGGACTACTAATAGTTATAATTTTGAATAGT-3′, where underlined sequences are putative −35 and −10 promoter sequences) active in lactobacilli at the EcoRI site of pH4611, a shuttle plasmid vector for E. coli and lactobacilli (18).

Plasmid pYSSE3 is a derivative of a shuttle plasmid vector pBE31 (18) devoid of the replication origin (ori) of pAMβ1. The DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using pBE31 DNA as a template, synthetic DNA primers having the sequences 5′-GCAGATCTTTTGATTTGCC-3′ and 5′-CTAGATCTAGGTGAAGATC-3′, and KOD Plus DNA polymerase. After digestion of the amplified fragment with BglII, the DNA was self-ligated to obtain plasmid pYSSE3 (2,446 bp in length), which consisted of the pUC19-derived replication origin active in E. coli, the erythromycin resistance gene active in both E. coli and lactobacilli, and the multicloning site.

Recombinant plasmids for the insertional mutagenesis were constructed as follows. The DNA fragment of the target gene, which was truncated at both 5′ and 3′ termini of the gene, was obtained by PCR using L. casei Shirota DNA as a template, a pair of primers listed in Table 2, and KOD Plus DNA polymerase. After digestion with relevant restriction endonucleases at both ends, the fragment was purified and ligated to the vector plasmid pYSSE3 DNA, which was predigested with the same restriction enzymes and treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase. The resulting plasmid having the correct structure was selected from E. coli JM109 transformants and then introduced into L. casei Shirota by electroporation (7) with a small modification. Briefly, cells were grown in MRS broth to early log phase and harvested by centrifugation. Cells were washed once with an equal volume of 1 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), followed by washing with a half volume of 10% glycerol, and then washed with a small volume of 10% glycerol. Cells were suspended in 1/200 of the original culture volume of 10% glycerol. Electroporation was done with 50 μl of competent cells and 1 to 2 μl of plasmid DNA solutions prepared with the Promega Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA purification system according to the instructions of the supplier in a 2-mm-path cuvette at a 25-μF capacitance and 1.5-kV voltage with a Bio-Rad electroporation apparatus. Cells were transferred to 1 ml of MRS broth and then incubated at 37°C for 90 min and were plated onto MRS agar plates containing 20 μg/ml erythromycin and incubated at 37°C for 2 or 3 days. Erythromycin resistance clones thus obtained were confirmed for plasmid integration by PCR with appropriate primers.

TABLE 2.

Synthetic primers for amplification of truncated and whole gene fragments

| Target gene | Primer sequence (5′→3′)

|

Position in relevant genea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ terminal | 3′ terminal | ||

| cps1A | CGGGATCCGACACTTCGCTGTTGGTCAA | AACTGCAGGGTTTGGTCTGTAAGCTCTC | +139 to +735 |

| cps1B | CGGGATCCGAGCCAAAACATGTTGTTGCT | AACTGCAGTGTTACGACAACAACCCCGT | +94 to +594 |

| cps1D | AACTGCAGGCTAAAATTGTTTGGCATGTTC | CGGGATCCCACAATCATCTCACTAGCTCC | +356 to +967 |

| cps1E | AACTGCAGAGAAACTTAGCTTTACAGAAAG | CGGGATCCCGGATCATTTACATACTTTTTA | +232 to +768 |

| cps1F | CGGGATCCGTGGCATACTTCTTTCCATTT | AACTGCAGGAGAGCTCCAAAGATTGCAA | +343 to +1035 |

| cps1G | CGGGATCCATCATGAATCGGCAGTATTTA | AACTGCAGACCGTCTAAAATAGTAACATTT | +145 to +543 |

| cps1H | CGGGATCCTGGTTCTTTCAAGGACTGGA | AACTGCAGGGAAAGAATTGTTCCAATCAC | +382 to +1161 |

| cps1I | CGGGATCCGGATTGCGAGCAATTGAAAG | AACTGCAGTTGTGTTGATCCCTGCCCTT | +220 to +711 |

| cps1J | CGGGATCCGCCGAGCTACATATTCTCGA | AACTGCAGTCCAACGCAACCATCTCAGA | +63 to +575 |

| Whole cps1A | TCCCCCGGGAAATCAAGGGATTAGGTGG | AAACTGCAGTCAAATCCGGCGACGGC | -30 to +930 |

| Whole cps1C | TCCCCCGGGTTGGGGGAATCTATCG | AAACTGCAGTTATATTTTTCCATCGATAAA | −17 to +1182 |

The relative nucleotide positions of the resulting amplified fragment calculated from the first nucleotide in the initiation codon as +1 in each respective gene are shown.

Recombinant plasmids for deletion mutagenesis were constructed by using pLP10 for deletion of cps1C or by using pYSSE3 for deletion of cps1A, cps1E, cps1H, and cps1J. Two fragments containing 5′-terminal and 3′-terminal ends of the target gene were amplified with the primers listed in Table 3. The primers for this use were designed to enable in-frame rejoining of the 5′- and 3′-terminal fragments of the gene, thereby avoiding translational interruption within an operon. These fragments were cloned into the respective plasmids in the same order as on the chromosome to obtain in-frame deletions within the genes. L. casei Shirota was transformed with these plasmids, and erythromycin-resistant clones were selected first. These clones have the recombinant plasmids integrated into either side of the respective gene regions by homologous recombination. After several cycles of subculturing (0.1% inoculation into fresh medium followed by full growth), erythromycin-sensitive clones were screened and checked for the reversion or deletion.

TABLE 3.

Synthetic primers for amplification of 5′- and 3′-terminal fragments to isolate deletion mutants

| Target gene and terminal fragment | Primer sequence (5′→3′)

|

Position in relevant genea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ terminal | 3′ terminal | ||

| cps1C | |||

| 5′ | CGGGATCCTAGGGGGAATCTATCGTGAC | GCGGTACCCTGACCTGAACTAATCTGCT | -13 to +651 |

| 3′ | GCGGTACCTCCAAAACCAAAAAGGATTTGG | TTCTGCAGGAGAATCTTATATTTTTCCATC | +721 to +1189 |

| cps1A | |||

| 5′ | ATACTGCAGATTGGCATGGGTTTTC | TAAGAATTCAGCTTCGTATTTTGGTACA | -943 to +140 |

| 3′ | GAAGAATTCAATATGCAGGATTTA | ATATCTAGATTCCCCCAACCATACT | +883 to +1839 |

| cps1E | |||

| 5′ | ACATCTAGACTTGTTCACGTCAATACGA | CTCATCGATTATGGGCGGGAATAATAAT | -986 to +51 |

| 3′ | TAGATCGATACGGTATACGAT | TATCTGCAGGCCAACAAAAGAAAGTCG | +518 to +1580 |

| cps1H | |||

| 5′ | ACCGGATCCGGAGCAGTTATTGGTGC | GGGGTACCATACAGATTAATTCCTAAGC | -808 to +187 |

| 3′ | CCGGTACCCTATTCAGCGAATCGTGG | AGAGGTACCTAATTGTGTTGATCCCTGC | +1222 to +2173 |

| cps1J | |||

| 5′ | AGACTGCAGACGATTATCTGTTGTCT | ATAGAATTCACCCCTCCAATACATTG | -919 to +48 |

| 3′ | TAAGAATTCTGAGATGGTTGCGTTGG | TAATCTAGATAGGCTTTATTCACATCG | +603 to +1530 |

The relative nucleotide positions of the resulting amplified fragment calculated from the first nucleotide in the initiation codon as +1 in each respective gene are shown.

Plasmid pYAP300, which enabled gene integration into the L. casei chromosome at the attB site for phage phiFSW, was constructed as follows. The DNA fragment of the replication origin from plasmid p15A was amplified from pHY460 (14), with primers having the sequences 5′-AGTATTAATCCTTTTTGATAATCTCATG-3′ and 5′-GGAAGATCTCCCTCACTTTCTGGCT-3′. The fragment was digested with restriction endonucleases PshBI and BglII and ligated to PshBI- and BglII-digested pYSSE3 DNA. The resulting plasmid, pYA1, consisting of the p15A replication origin and erythromycin resistance gene, was obtained. To the EcoRI site of pYA1 was introduced a synthetic promoter sequence (5′-AATTCTTTAATATTTGACAAATGGACTACTAATAGTTATAATTTTGAATAGT-3′) for lactobacilli to obtain pYAP3. A DNA fragment containing the phiFSW int gene and attP site (36) was amplified using phiFSW DNA as a template, a set of primers having the sequences 5′-ATGATTAATTTGATGAACTTGACAAAAG-3′ and 5′-ATCATTAATGGTGTTTTCAAGCCTTC-3′, and KOD Plus DNA polymerase. After digestion with PshBI, the fragment was introduced into the PshBI site of pYAP3, resulting in the formation of pYAP300 (5,017 bp in length), in which the attP site was located far from the lactobacillus promoter sequence and multicloning site.

PS-PG preparation and analyses.

Cells grown overnight in 100 ml of MRS medium with or without erythromycin (20 μg/ml) were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and washed three times with distilled water. Cells were resuspended in 4 ml of 5 mM Tris-malate-2 mM MgCl2 (pH 6.4). After boiling for 10 min, 1 mg of N-acetylmuramidase SG (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd.) and 1 mg of Benzonase (Merck Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were added to the cell suspension and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. The reaction mixture was heated at 100°C for 10 min and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. To the supernatant was added 1 mg of pronase (Roche Diagnostics K.K., Tokyo, Japan), and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for an additional 20 h. The resultant solution was dialyzed thoroughly in a 3,500-molecular-weight-cutoff dialysis bag against deionized water with several exchanges of water. The samples thus obtained were called the PS-PG fraction and stored in a refrigerator until use. We confirmed that the gel filtration pattern of the PS-PG fraction from the wild-type strain on a Sephacryl S-200 column was similar to that described previously (26), namely, there were two major peaks corresponding to PS-PG1 and PS-PG2, with molecular masses of more than 100 kDa and 30 kDa, respectively, meaning that the sample was comparable to that of Nagaoka et al. (26). Gel filtration analyses of the PS-PG fractions from wild-type and mutant cells by using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) were performed as described below. To the PS-PG fractions were added equal volumes of 100 mM NaCl, and the samples were applied onto an 8.0-mm-by-300-mm Shodex KS-804 size exclusion column (Showa Denko K.K., Tokyo, Japan), followed by elution with 50 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min on a Waters Alliance HPLC system (Nihon Waters K. K., Tokyo, Japan) with an RI 2414 differential refractometer (Nihon Waters K. K.) to detect carbohydrates.

Immunological assay methods.

Reactivity of L. casei Shirota and its mutant strains to L. casei Shirota-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) was determined by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method as essentially described previously (46).

Cytokine production in the culture supernatants of mouse macrophage-derived cell lines RAW 264.7 and J774.1 or of mouse spleen cells were determined by a sandwich ELISA method. Briefly, heat-killed L. casei Shirota and mutant cells suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Inc.) at a concentration of 100 μg/ml were prepared. Macrophage cells cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cancera International, Inc., Toronto, Canada) were suspended with RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum at a density of 106 cells/ml and poured into 96-well plates at 0.2 ml/well. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h in a CO2 incubator, the bacterial cell suspension was added at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for an additional 24 h, and then the culture supernatants were collected for measurement of cytokine production. Mouse spleen cells were prepared from female BALB/c mice (8 to 15 weeks old; Japan SLC, Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan), the cell density was adjusted to 5 × 106 cells/ml with RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 μl was poured into each well of 96-well plates. An equal volume of bacterial cells suspended with RPMI at a concentration of 1, 3, or 20 μg/ml was added to each well followed by incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 24 h, and then culture supernatants were collected. The antibodies or ELISA kits used for each cytokine assay were an ELISA development kit (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), C15.6 rat anti-mouse interleukin-12 (IL-12) MAb (BD Pharmingen, Inc., Franklin Lakes, NJ) and C17.8 biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-12 MAb for IL-12p40, a BD Opt EIA IL-10 kit (BD Pharmingen) for IL-10, rat anti-mouse IL-12(p70) MAb (ELISA capture) (BD Pharmingen) and C17.8 biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-12 MAb (BD Pharmingen) for IL-12p70, and rat anti-mouse IL-6 MAb (ELISA capture) (BD Pharmingen) and biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-6 MAb (ELISA detection) (BD Pharmingen) for IL-6. Each value was determined as the mean of three wells.

To measure the inhibitory or stimulatory activities of L. casei Shirota and its mutants on the production of IL-6 by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated RAW 264.7 cells, E. coli LPS (10 μg/ml) with or without heat-killed L. casei cells was added to RAW 264.7 cells inoculated into 96-well plates at 5 × 105 cells/well and incubated at 37°C for 24 h in a 5% CO2 incubator. Culture supernatants were collected and assayed for IL-6. The inhibitory or stimulatory activities of bacterial preparations were explained as the percent increase or decrease in IL-6 production compared with the value of LPS addition only as described previously (24).

Each immunological experiment was done at least twice, and all statistical analyses for cytokine production assays were performed with Dunnett's test.

RESULTS

Identification of a cluster of genes that may participate in PS biosynthesis.

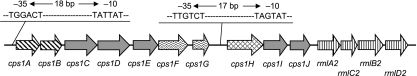

L. casei Shirota does not produce extracellular PS but is known to have two types of cell-wall-associated PS: longer, high-molecular-mass PS (PS-1) and shorter, low-molecular-mass PS (PS-2) (26). From the completed genome sequence of L. casei Shirota (unpublished in-house data), we searched for candidate genes possibly involved in biosynthesis of PS moieties of the cell wall based on the similarity to known exo-PS and capsular PS (EPS and CPS, respectively) biosynthesis genes from lactic acid bacteria by using GENETYX software (Genetyx Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). We could pick up several tens of candidate genes by this survey. Among them, we focused on a cluster of 10 genes lined up in the same direction on the chromosome (Fig. 1). The gene organization of this cluster constituted the basic structure of gene order for EPS and CPS syntheses (15, 20, 30), and the predicted amino acid sequences of some gene products had high percentages of amino acid sequence identities to known related gene products from various lactic acid bacteria (15, 20, 30) (Table 4). In addition, the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthesis gene cluster consisting of rmlA, rmlC, rmlB, and rmlD (38, 39) was also identified downstream of these genes, as shown in Fig. 1. These 10 genes may constitute two successive operons, one consisting of the first 7 genes and the other consisting of remaining 3 genes, with a possibility of including the rmlACBD gene cluster within the second operon, assumed from the nucleotide sequence of this region. Therefore, we postulated that these genes were involved in PS biosynthesis and named them cps1A, cps1B, cps1C, cps1D, cps1E, cps1F, cps1G, cps1H, cps1I, and cps1J in sequential order for cell wall polysaccharide synthesis (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of gene organization of a cluster of genes involved in the biosynthesis of high-molecular-mass cell wall PS of L. casei Shirota. Ten genes from cps1A to cps1J were localized within about an 11.2-kb segment of the genome and divided into groups of genes presumed from the amino acid sequence similarities to known gene products, as illustrated in different colors/patterns: arrows with hatched lines, chain length determination; arrows with gray color, glycosyltransferase; arrows with wavy lines, function unknown; arrow with cross-section, repeat unit transfer; arrows with vertical lines, nucleotide sugar synthesis. Two possible promoter sequences at the −35 and −10 regions are also described and thus may constitute two transcriptional units in this region.

TABLE 4.

Amino acid sequence similarities of the PS-1 biosynthesis gene products to proteins from other lactic acid bacteria

| Gene | Polypeptide length (amino acids) | COG Database no. | Predicted function | Predicted polypeptide localization | Similar gene (source) | Amino acid sequence similarity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cps1A | 309 | Chain length determination | Membrane | wzd (L. rhamnosus RW-9595M) | 70.2 | 30 | |

| epsA (L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus Lfi5) | 37.5 | 20 | |||||

| cps1B | 252 | COG0489 | Capsular polysaccharide | Cytosol | wze (L. rhamnosus RW-9595M) | 85.8 | 30 |

| biosynthesis | epsG (L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus Lfi5) | 46.4 | 20 | ||||

| epsC (L. acidophilus NCFM) | 40.6 | 2 | |||||

| cps1C | 393 | COG0438 | Rhamnosyltransferase | Cytosol | rgpA (L. lactis subsp. lactis IL-1403) | 43.4 | 4 |

| rgpAc (S. thermophilus CNRZ1066) | 46.3 | 3 | |||||

| cps1D | 385 | COG0438 | Glycosyltransferase | Cytosol | cpsG (S. salivarius NCFB2393) | 43.5 | 1 |

| epsG (L. johnsonii NCC533) | 22.3 | 31 | |||||

| cps1E | 324 | Glycosyltransferase | Cytosol | epsN (L. lactis subsp. cremoris HO2) | 24.8 | 11 | |

| cpsI (S. salivarius NCFB2393) | 22.0 | 1 | |||||

| cps1F | 419 | ? | Membrane | ||||

| cps1G | 221 | Galactoside acetyltransferase | Cytosol | thgA2 (L. plantarum WCFS1) | 30.6 | 19 | |

| epsH (S. thermophilus CNRZ1066) | 39.3 (in 84 aa) | 3 | |||||

| cps1H | 478 | COG2244 | Polysaccharide repeat unit transporter | Membrane | epsI (S. thermophilus CNRZ1066) | 46.2 | 3 |

| cps1C (L. plantarum WCFS1) | 44.5 | 19 | |||||

| cps1I | 295 | COG1215 | Glycosyltransferase | Cytosol | cps19bQ (S. pneumoniae 19b) | 26.3 | 6 |

| welF (L. rhamnosus RW-9595M) | 23.7 | 30 | |||||

| cps1J | 238 | COG2148 | Sugar transferase | Membrane | epsE (L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus Lfi5) | 58.3 | 20 |

| welE (L. rhamnosus RW-9595M) | 79.3 | 30 |

The amino acid identities of these genes' products to known bacterial proteins are summarized in Table 4. The highest identities were detected in Cps1A, Cps1B, and Cps1J to Wzd, Wze, and WelE from Lactobacillus rhamnosus RW-9595 M (30), which are all predicted to be members of an EPS biosynthesis cluster, at 70.2%, 85.8%, and 79.3% identities, respectively. Cps1C resembled RgpA from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL-1403 (43.4% amino acid identity) (4) and from Streptococcus mutans Xc (42.3% amino acid identity) (45) and was presumed to be a rhamnosyltransferase (38), and Cps1H resembled EpsI (46.2% identity) from Streptococcus thermophilus CNRZ1066 (3) and was presumed to be a repeat unit transporter. Cps1E and Cps1I had limited amino acid sequence identities to known genes of lactic acid bacteria, and there was no gene similar to cps1F detected.

Evidence for the genes of this cluster to participate in biosynthesis of PS-1 moiety of L. casei Shirota cell wall.

In order to determine the functional properties of the genes, each gene was disrupted by sequential double-crossover deletion mutagenesis (for the cps1C gene) or by insertional inactivation (the remaining nine genes) as described in Materials and Methods. These were designated as the Ωcps1A, Ωcps1B, Δcps1C, Ωcps1D, Ωcps1E, Ωcps1F, Ωcps1G, Ωcps1H, Ωcps1I, and Ωcps1J mutants. As a result, these mutations, except for Ωcps1H and Ωcps1I, caused aggregate formation of the cells during the growth in MRS medium. It is noteworthy that insertion of the plasmids carrying truncated genes in different loci did not seem to affect the function of other genes, especially those located downstream of the disrupted gene in the predicted same operon. For example, insertion of the plasmid into the cps1H or cps1I gene locus did not affect the function of cps1J, whose disruption caused cell aggregation, and insertion of the plasmid into cps1F, whose disruption caused less reactivity to MAb to L. casei Shirota, while the downstream cps1G disruption caused complete loss of reactivity to the antibody, as shown later. However, to avoid any polar effect, we also isolated deletion mutants for the cps1A, cps1E, cps1H, and cps1J genes as for cps1C. In addition, we introduced pYAP300 plasmid derivatives carrying the whole gene region for cps1A or cps1C and isolated plasmid integrants that harbored the recombinant plasmid at the attachment site attB on the Δcps1A and Δcps1C mutants, respectively. All of the Δcps1A, Δcps1E, Δcps1H, and Δcps1J deletion mutants showed quite similar growth phenotypes to respective insertion mutants (data not shown). On the contrary, the Δcps1A mutant harboring pYAP300-cps1A and the Δcps1C mutant harboring pYAP300-cps1C resembled wild-type cells, indicating that the defects of Δcps1A and Δcps1C were recovered by the wild-type cps1A and cps1C genes provided in trans, respectively, although pYAP300 or pYAP300-cps1C did not recover the defect of the Δcps1A mutant (data not shown). Therefore, it is obvious that the functions of cps1A and cps1C were complemented by the same genes located in different positions of the genome, and the deletions in cps1A and cps1C did not affect the functions of the other genes in the same cluster.

Next, we analyzed the reactivity of these mutant cells to the L. casei Shirota-specific MAb by ELISA (46) and found that gene disruptions in cps1A, cps1B, cps1C, cps1D, cps1E, cps1G, and cps1J, irrespective of the method of mutagenesis, completely diminished the reactivity to the MAb, Ωcps1F partially reduced the reactivity, and the reactivity of Ωcps1H, Ωcps1I, and Δcps1H did not change. Again, the Δcps1A/cps1A and Δcps1C/cps1C complementation clones recovered the reactivity to the MAb (data not shown).

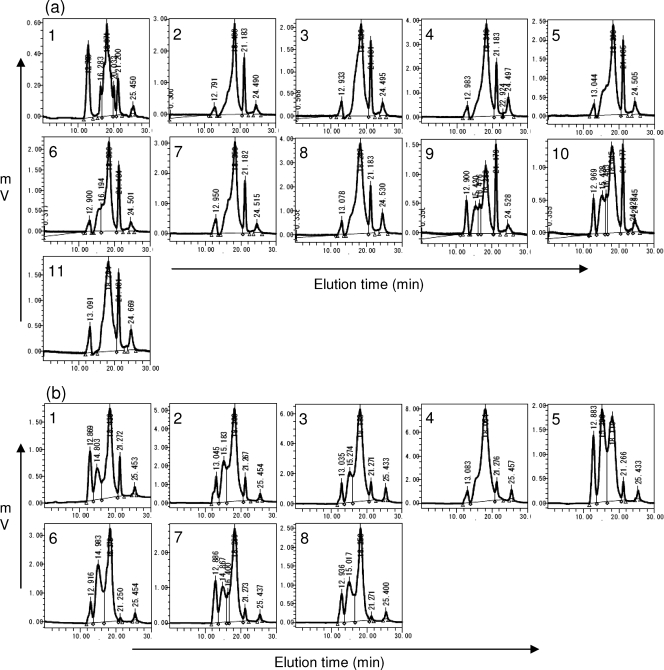

Cell wall components of L. casei Shirota and the gene disruption mutants were next analyzed. PS-PG fractions obtained by N-acetylmuramidase SG digestion were eluted with a KS804 size exclusion column using a Waters HPLC system. The PS-PG fraction from L. casei Shirota had two peaks, as has been shown (26) and as shown in Fig. 2a. On the contrary, most of the mutant cell wall fractions (except Ωcps1H and Ωcps1I) had only single peaks at the position of low-molecular-mass PS-2. The small peaks at pass-through positions indistinguishable from those of PS-1 from some of the mutants (Ωcps1A, Δcps1C, Ωcps1F, Ωcps1J, and Δcps1A) were confirmed not to be PS-1, because phenol-sulfate staining did not detect any sugar signals at those positions (data not shown). The PS-PG fractions from cps1H and cps1I mutants had two peaks like that from wild-type L. casei Shirota. Both PS-PG fractions of the Δcps1A/cps1A and Δcps1C/cps1C complementation clones showed quite similar elution patterns to that of the wild type, again (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

Elution profiles of PS-PG fractions from L. casei Shirota and its gene knockout mutants. PS-PG fractions were eluted through KS-804 size exclusion column using a Waters HPLC system, and refractive indexes were monitored with a differential refractometer. (a) Elution profiles of PS-PG fractions from wild type (diagram 1) and insertion and deletion mutants (diagram 2, Ωcps1A; diagram 3, Ωcps1B; diagram 4, Δcps1C; diagram 5, Ωcps1D; diagram 6, Ωcps1E; diagram 7, Ωcps1F; diagram 8, Ωcps1G; diagram 9, Ωcps1H; diagram 10, Ωcps1I; and diagram 11, Ωcps1J). (b) Elution profiles of PS-PG fractions from the wild type (diagram 1), deletion mutants (diagram 2, Δcps1A; diagram 3, Δcps1C; diagram 4, Δcps1E; diagram 5, Δcps1H; and diagram 6, Δcps1J), and complementation clones (diagram 7, Δcps1A/cps1A; diagram 8, Δcps1C/cps1C).

Immune modulation activities of L. casei Shirota mutants.

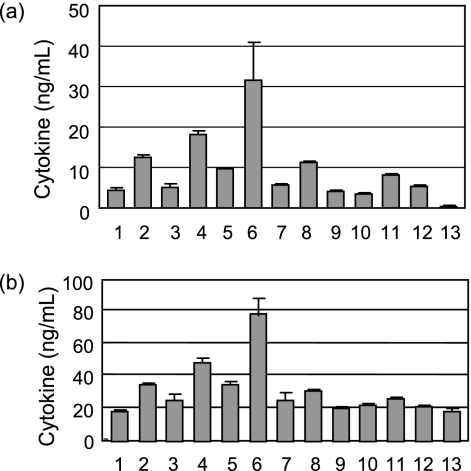

Mouse macrophage-derived cell lines RAW 264.7 and J774.1 were used to detect immune modulation activities of L. casei Shirota and its gene disruption mutants. Heat-killed bacterial cells were added at 10 μg/ml to macrophage cells confluent in 96-well plates, and the culture supernatants were collected for cytokine assay after 24 h of incubation. As shown in Fig. 3, the TNF-α-inducing activities of the Ωcps1A, Δcps1C, Ωcps1D, Ωcps1E, Ωcps1G, and Ωcps1J mutants were higher than that of wild-type L. casei Shirota. According to the assay for TNF-α production by both RAW 264.7 and J774.1 cells, the Ωcps1B and Ωcps1F mutants had weak stimulation activities at least compared to J774.1 cells and the Ωcps1H and Ωcps1I mutants had no stimulation activity compared to both RAW 264.7 and J774.1 cells.

FIG. 3.

TNF-α production by mouse macrophage-like RAW 264.7 (a) and J774.1 (b) cells in the presence of heat-killed L. casei Shirota and its mutant cells. Lane 1, wild type; lane 2, Ωcps1A mutant; lane 3, Ωcps1B mutant; lane 4, Δcps1C mutant; lane 5, Ωcps1D mutant; lane 6, Ωcps1E mutant; lane 7, Ωcps1F mutant; lane 8, Ωcps1G mutant; lane 9, Ωcps1H mutant; lane 10, Ωcps1I mutant; lane 11, Ωcps1J mutant; lane 12, L. casei Shirota/pYSSE3; lane 13, negative control (RPMI medium).

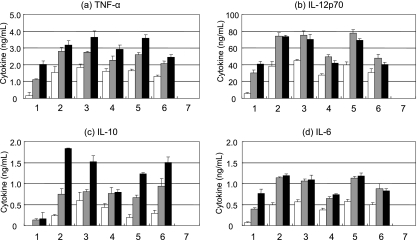

To avoid the effect of plasmid integration, we isolated deletion mutants of cps1A, cps1C, cps1E, cps1H, and cps1J genes having internal in-frame deletions with no plasmid-derived sequences by sequential homologous recombination on both sides of the genes and further analyzed the cytokine-inducing activities of these mutants. In this experiment, we used mouse spleen cells, because it is possible to analyze the production of various cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-12, IL-10, and IL-6 in a single culture preparation simultaneously. Figure 4 shows the results of stimulation of TNF-α, IL-12p70, IL-10, and IL-6 production of mouse spleen cells by the addition of L. casei Shirota or the deletion mutants. The production of TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IL-6 by mouse spleen cells was stimulated much more by the addition of a low concentration (1 or 3 μg/ml) of any of the Δcps1A, Δcps1C, Δcps1E, and Δcps1J cells than by wild-type cells, while the stimulation efficiencies of these mutants for TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IL-6 production at a high concentration (10 μg/ml) were less pronounced. On the other hand, stimulation of IL-10 production by these cells was concentration dependent. The stimulation activities of L. casei ATCC 334 were also higher than that of L. casei Shirota like those of the PS-1-deficient deletion mutants for any of the cytokines assayed. In any case, the L. casei Shirota mutants defective in the synthesis of PS-1 in the cell wall became more active in stimulation of macrophages for cytokine production.

FIG. 4.

Cytokine production by mouse spleen cells in the presence of heat-killed cells of various L. casei strains. The cytokines measured were TNF-α (a), IL-12p70 (b), IL-10 (c), and IL-6 (d). The bacterial strains used in this experiment were as follows: lane 1, wild type; lane 2, Δcps1A mutant; lane 3, Δcps1C mutant; lane 4, Δcps1E mutant; lane 5, Δcps1J mutant; and lane 6, L. casei ATCC 334. Lane 7 contained medium. The bacterial cells were added at a concentration of 1 μg/ml (white bars), 3 μg/ml (grayish bars), or 10 μg/ml (black bars).

The effect of the mutant strains on LPS-stimulated IL-6 production by RAW 264.7 was next analyzed as a model for inflammatory state. Matsumoto et al. (24) reported that the addition of heat-killed L. casei Shirota or its PS-PG fraction lowered the productivity of IL-6 by LPS-treated RAW 264.7 cells. In a similar experiment, when deletion (cps1C) or insertion (rest of the genes) mutants were added with LPS to RAW 264.7 cells, all of the mutants except for the Ωcps1H and Ωcps1I mutants rather enhanced IL-6 production, while the Ωcps1H and Ωcps1I mutants still had the ability to suppress IL-6 production like the wild type. Therefore, L. casei Shirota's suppressive activity on the LPS-induced IL-6 production by macrophage cells correlated with the presence of the PS-1 moiety on the cell wall.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have genetically identified a cluster of genes whose products have a pivotal role in biosynthesis of cell wall-associated high-molecular-mass PS (PS-1) in the genome of L. casei Shirota. The organization of these genes seems to be of a typical EPS and CPS biosynthesis gene cluster (6, 13, 16, 30, 44), assumed to comprise regulatory factors determining chain length (cps1A and cps1B) followed by glycosyltransferases (cps1C, cps1D, and cps1E), a factor modifying the glycosyl residue (cps1G), and a repeat unit transfer factor (cps1H) with genes for nucleotide sugar substrate synthesis (rmlA, -C, -B, and D), when predicted from the amino acid sequence similarities to other gene clusters from lactic acid bacteria. The position of cps1J, an ortholog of a conserved priming glycosyltransferase gene, at the 3′ end of this cluster is not usual among EPS and CPS biosynthesis gene clusters in lactic acid bacteria (15, 16, 20, 37). However, welE, a cps1J homolog in the L. rhamnosus EPS biosynthesis gene cluster, is also localized at the 3′ end of the cluster (30). In addition, there is a sequence-coding transposase-like gene from insertion sequence 1165 downstream of the PS-1 gene cluster (data not shown), as was the case in the L. rhamnosus EPS gene cluster (30). Therefore, the overall gene organizations of the PS-1 gene cluster of L. casei Shirota and the EPS gene clusters of L. rhamnosus strains (30) are similar to each other, implying that the both gene clusters probably have the same origin. On the contrary, glycosyltransferase genes localized in between are quite different from each other and from EPS gene clusters of other lactic acid bacteria, meaning that there have been frequent rearrangements and exchanges of glycosyltransferase genes within the clusters like those in S. thermophilus (6, 41) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (15). Indeed, the compositions and thus the structures of EPS from L. rhamnosus (40) and PS-1 from L. casei Shirota (26) are quite different. Some of the genes in the PS-1 cluster are unique and have limited (cps1E, cps1G, and cps1I) or almost no (cps1F) similarities to other prokaryotic genes, and thus the precise functions of these genes are still obscure. We have realized that not all of the strains of L. casei harbor the genes in this cluster (M. Serata, E. Yasuda, and T. Sako, unpublished result). For example, L. casei neotype strain ATCC 334 does not have this segment (22). The fact that the GC percent of the region between cps1A and cps1J is 38.5%, while that of the whole genome of L. casei Shirota is 46.3%, may support the idea that this segment was transferred from another genus or species.

Although cps1H and cps1I genes are members of this cluster, their contribution to the synthesis of PS-1 was not apparent. We found open reading frames having high similarities to cps1H (82.6% amino acid sequence identity) and cps1I (68.5% amino acid sequence identity) in another place on the L. casei Shirota genome (data not shown). Therefore, these homologs may complement the defect of the cps1H or cps1I mutant. Further analysis of the function of these genes is needed to clarify the role of each gene product in the cell wall-associated PS synthesis.

Based on the presumed function of each gene, we expected to obtain mutants whose structures and compositions of the cell wall PS have been altered differently. However, the disruption of each gene, except for cps1H and cps1I, apparently resulted in a common consequence of the loss of high-molecular-mass PS in the cell wall fraction which brought about similar phenotypic alteration of characteristics of L. casei Shirota cells, namely, cell aggregation in growth media and loss of reactivity to the specific MAb, indicating that all of these genes are primarily needed for synthesis of the backbone of PS-1 structure but not for its modification. The fact that the reactivity of cps1F mutant to the L. casei Shirota-specific MAb was partially positive implies that the Ωcps1F mutant strain still has either a small number of epitopes or less-reactive epitopes on its cell surface, although the elution pattern of the PS-PG fraction from the Ωcps1F mutant was not different from those of other mutants. Sugar composition analyses for PS-1 and PS-2 fractions from wild-type and mutant strains, which are in preparation as a next step, would be useful to clarify the structural differences between wild-type and mutant strains. A similar plus-or-minus phenotype was seen in the PS synthesis of Enterococcus faecalis FA2-2, in which a larger molecular species of PS was lost when each of several genes was disrupted by plasmid insertion (13). The proper structure and combination of oligosaccharide unit may be important for the following transmembrane transfer and/or polymerization of the unit at the outer surface.

The results in this study clearly show that the high-molecular-mass component of the cell wall PS on L. casei Shirota cells acts as a suppressor for its own immunologic activity to induce the production of various cytokines by macrophages, for both Th1 cytokines TNF-α, IL-12p70, and IL-6 and Th2 cytokine IL-10. Although the contributions of cell surface components of L. casei Shirota have been suggested through experiments using extracted materials from the cells (24, 28, 33) or chemically modified cells (33), the mechanisms of action of these molecules might be different from those of whole cells. In this regard, the mutants we constructed are the first examples which can evaluate directly the effects of presence or absence of a particular cell component on its immune modulation activity. Although we have not yet examined the effects of purified high-molecular-mass PS on the stimulation or suppression of cytokine production by macrophages, Matsumoto et al. (24) reported that the purified PS-PG fraction was active in suppressing the cytokine production by macrophages induced by LPS, which is consistent with our results. Determination of the activity of purified PS-1 or of PS-PG fraction devoid of PS-1 is needed to clarify the active component of this suppressive activity, and our mutant strains would be very useful in such experiments.

We measured the amounts of cytokines in the culture supernatant after 24 h of incubation with bacterial cells to compare the induction activities of various mutants in this study. There seemed to be differences in the kinetics of production of different cytokines, and the 24-h time point was still an accumulating stage or almost fully accumulated stage, depending on the bacterial strains and their concentrations added (Fig. 4), but there was no indication of breakdown of any cytokine that accumulated in the culture supernatant during 48 h of incubation (E. Yasuda and T. Sako, unpublished results). Therefore, it is appropriate to compare the stimulation activities of wild-type and mutant strains by using the amounts of cytokines at the 24-h time point.

In the course of the study, we realized that the L. casei Shirota immunologic activity was reduced when plasmid integrants were used to stimulate cytokine production by mouse spleen cells (E. Yasuda and T. Sako, unpublished result). This phenomenon was not apparent when macrophage cell lines were used (Fig. 3). However, the activities of plasmid integrants in such in vitro systems should be evaluated very carefully. Residual erythromycin, which was added for cultivation of plasmid integrants, may affect the monocyte response as described by Ortega et al. (29), or it may be possible that the DNA segment with a certain sequence on the plasmid affects the response.

While simultaneous addition of L. casei Shirota cells with E. coli LPS reduced the production of IL-6, the addition of mutant cells defective in PS-1 biosynthesis did not show this suppressive effect but rather additively increased the production of IL-6, indicating that the suppressive effect of the PS-PG fraction on IL-6 production by lamina propria mononuclear cells or by RAW 264.7 cells reported by Matsumoto et al. (24) is caused by the PS-1 moiety of the fraction. Although we do not know what will happen when L. casei Shirota cells are added after macrophages are pretreated with LPS, we presume that similar suppression will occur depending on the time point when L. casei Shirota cells are added. Since the production of IL-6 by the lamina propria lymphocytes isolated from both mice pretreated with LPS and mice pretreated with T-cell receptor β/CD28 was suppressed by the addition of L. casei Shirota cells (24), it is not probable that the direct interaction of L. casei Shirota cells with LPS or CD14 is a prerequisite step to exert the suppressive effect.

L. casei Shirota is thought to be a potent IL-12 inducer both in vitro and in vivo. However, it is probable that PS-1 on the cell wall somewhat reduces the activity of its own as well as other inducers such as LPS. Another L. casei strain, ATCC 334, does not have the gene cluster for PS-1 synthesis and is a stronger inducer of IL-12 and other cytokines than L. casei Shirota (Fig. 4). In addition, ATCC 334 was not suppressive but stimulative on LPS-induced IL-6 production by RAW 264.7 cells (data not shown), being consistent with our prediction. Therefore, the anti-inflammatory activity of L. casei Shirota (23) would be determined by the presence or absence of the PS-1 moiety on the cell wall. A similar suppressive effect of certain strains of L. casei on E. coli-stimulated TNF-α release has been observed in an ex vivo experiment (5) corresponding to our results, thus implying that the strain specificity of the immune modulation activities at least in part depends on the surface structure of each strain. Shida et al. (34) also suggested in an experiment using chemical modification of various lactic acid bacteria that the resistance to lytic enzymes which is specified by the cell surface structure including the PS moiety affects its immune modulation activity.

In conclusion, the gene cluster identified on the chromosome of L. casei Shirota in this study is involved in the biosynthesis of high-molecular-mass PS-1 on the cell surface of L. casei Shirota, and the PS-1 moiety of the cell wall functions as a unique regulatory component which suppresses the possible excessive immune response of macrophages/monocytes against not only its own stimulative components but also other inducers. This may indicate that PS-1 is a novel species of bacterial cell wall PS that interacts with a certain host cell component to regulate the activation of host immune responses.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to Satoshi Matsumoto and Kan Shida of the Yakult Central Institute for Microbiological Research for helping us with the data acquisition in immune modulation assays and Kazumasa Kimura of the Yakult Central Institute for Microbiological Research for advice and technical assistance with HPLC analyses of cell wall fractions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almiron-Roig, E., F. Mulholland, M. J. Gasson, and A. M. Griffin. 2000. The complete cps gene cluster from Streptococcus thermophilus NCFB 2393 involved in the biosynthesis of a new exopolysaccharide. Microbiology 146:2793-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altermann, E., W. M. Russell, M. A. Azcarate-Peril, R. Barrangou, B. L. Buck, O. McAuliffe, N. Souther, A. Dobson, T. Duong, M. Callanan, S. Lick, A. Hamrick, R. Cano, and T. R. Klaenhammer. 2005. Complete genome sequence of the probiotic lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:3906-3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolotin, A., B. Quinquis, P. Renault, A. Sorokin, D. Ehrlich, S. Kulakauskas, A. Lapidus, E. Goltsman, M. Mazur, G. D. Pusch, M. Fonstein, R. Overbeek, N. Kyprides, B. Purnelle, D. Prozzi, K. Ngui, D. Masuy, F. Hancy, S. Burteau, M. Boutry, J. Delcour, A. Goffeau, and P. Hols. 2004. Complete sequence and comparative genome analysis of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1554-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borruel, N., F. Casellas, M. Antolin, M. Llopis, M. Carol, E. Espiin, J. Naval, F. Guarner, and J. R. Malagelada. 2003. Effects of nonpathogenic bacteria on cytokine secretion by human intestinal mucosa. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98:865-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broadbent, J. R., D. J. McMahon, D. L. Welker, C. J. Oberg, and S. Moineau. 2003. Biochemistry, genetics, and applications of exopolysaccharide production in Streptococcus thermophilus: a review. J. Dairy Sci. 86:407-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chassy, B. M., and J. L. Flickinger. 1987. Transformation of Lactobacillus casei by electroporation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 44:173-177. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, T., P. Isomäki, M. Rimpiläinen, and P. Toivanen. 1999. Human cytokine responses induced by Gram-positive cell walls of normal intestinal microbiota. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 118:261-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Waard, R., J. Garssen, J. Snel, G. C. A. M. Bokken, T. Sako, J. H. J. Huis in't Veld, and J. G. Vos. 2001. Enhanced antigen-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity and immunoglobulin G2b responses after oral administration of viable Lactobacillus casei YIT9029 in Wistar and Brown Norway rats. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:762-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dicks, L. M. T., E. M. Du Plessis, F. Dellaglio, and E. Lauer. 1996. Reclassification of Lactobacillus casei subsp. casei ATCC 393 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 15820 as Lactobacillus zeae nom. rev., designation of ATCC 334 as the neotype of L. casei subsp. casei, and rejection of the name Lactobacilllus paracasei. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46:337-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forde, A., and G. F. Fitzgerald. 2003. Molecular organization of exopolysaccharide (EPS) encoding genes on the lactococcal bacteriophage adsorption blocking plasmid, pCI658. Plasmid 49:130-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grangette, C., S. Nutten, E. Palumbo, S. Morath, C. Hermann, J. Dewulf, B. Pot, T. Hartung, P. Hols, and A. Mercenier. 2005. Enhanced anti-inflammatory capacity of a Lactobacillus plantarum mutant synthesizing modified teichoic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:10321-10326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock, L. E., and M. S. Gilmore. 2002. The capsular polysaccharide of Enterococcus faecalis and its relationship to other polysaccharides in the cell wall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1574-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiwa, H., and N. Tsuchida. 1984. New shuttle vectors for Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. I. Construction and characterization of plasmid pHY460 with twelve unique cloning sites. Gene 32:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang, S.-M., L. Wang, and P. R. Reeves. 2001. Molecular chracterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 4, 6B, 8, and 18D capsular polysaccharide gene clusters. Infect. Immun. 69:1244-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jolly, L., J. Newell, I. Porcelli, S. J. F. Vincent, and F. Stingele. 2002. Lactobacillus helveticus glycosyltransferases: from genes to carbohydrate synthesis. Glycobiology 12:319-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato, I., T. Yokokura, and M. Mutai. 1984. Augmentation of mouse natural killer cell activity by Lactobacillus casei and its surface antigens. Microbiol. Immunol. 27:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiwaki, M., and M. Shimizu-Kadota. 2002. Development of genetic manipulation systems and application to genetic research in Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Biosci. Microflora 20:121-129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleerebezem, M., J. Boekhorst, R. van Krarenburg, D. Molenaar, O. P. Kuipers, R. Leer, R. Tarchini, S. A. Peters, H. M. Sandbrink, M. W. Fiers, W. Stiekema, R. M. Lankhorst, P. A. Bron, S. M. Hoffer, M. N. Groot, R. Kerkhoven, M. de Vries, B. Ursing, W. M. de Vos, and R. J. Siezen. 2004. Complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1990-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamothe, G. T., L. Jolly, B. Mollet, and F. Stingele. 2002. Genetic and biochemical characterization of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Arch. Microbiol. 178:218-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ljungh, A., and T. Wadström. 2006. Lactic acid bacteria as probiotics. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 7:73-89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makarova, K., A. Slesarev, Y. Wolf, A. Sorokin, B. Mirkin, E. Koonin, A. Pavlov, N. Pavlova, V. Karamychev, N. Polouchine, V. Shakhova, I. Grigoriev, Y. Lou, D. Rohksar, S. Lucas, K. Huang, D. M. Goldstein, T. Hawkins, V. Plengvidhya, D. Welker, J. Hughes, Y. Goh, A. Benson, K. Baldwin, J.-H. Lee, I. Diaz-Muniz, B. Dosti, V. Smeianov, W. Wechter, R. Barabote, G. Lorca, E. Altermann, R. Barrangou, B. Ganesan, Y. Xie, H. Rawsthorne, D. Tamir, C. Parker, F. Breidt, J. Broadbent, R. Hutkins, D. O'Sulllivan, J. Steele, G. Unlu, M. Saier, T. Klaenhammer, P. Richardson, S. Kozyavkin, B. Weimer, and D. Mills. 2006. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:15611-15616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsubuchi, T., A. Takagi, T. Matsuzaki, M. Nagaoka, K. Ishikawa, T. Yokokura, and Y. Yoshikai. 2003. Lipoteichoic acids from Lactobacillus strains elicit strong tumor necrosis factor alpha-inducing activities in macrophages through Toll-like receptor 2. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:259-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumoto, S., T. Hara, T. Hori, K. Mitsuyama, M. Nagaoka, N. Tomiyasu, A. Suzuki, and M. Sata. 2005. Probiotic Lactobacillus-induced improvement in murine chronic inflammatory bowel disease is associated with the down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in lamina propria mononuclear cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 140:417-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morath, S., A. Geyer, and T. Hartung. 2001. Structure-function relationship of cytokine induction by lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Exp. Med. 193:393-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagaoka, M., M. Muto, K. Nomoto, T. Matsuzaki, T. Watanabe, and T. Yokokura. 1990. Structure of polysaccharide-peptidoglycan complex from the cell wall of Lactobacillus casei YIT 9018. J. Biochem. 108:568-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naidu, A. S., W. R. Bidlack, and R. A. Clemens. 1999. Probiotic spectra of lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 39:13-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohashi, T., Y. Minamishima, T. Yokokura, and M. Mutai. 1989. Induction of resistance in mice against murine cytomegalovirus by cellular components of Lactobacillus casei. Biotherapy 1:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortega, E., M. A. Escobar, J. J. Gaforio, I. Algarra, and G. Alvarez De Cienfuegos. 2004. Modification of phagocytosis and cytokine production in peritoneal and splenic murine cells by erythromycin A, azithromycin and josamycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:367-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Péant, B., G. LaPointe, C. Gilbert, D. Atlan, P. Ward, and D. Roy. 2005. Comparative analysis of the exopolysaccharide biosynthesis gene clusters from four strains of Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Microbiology 151:1839-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pridomore, R. D., B. Berger, F. Desiere, D. Vilanova, C. Barretto, A. C. Pittet, M. C. Zwahlen, M. Rouvet, E. Altermann, R. Barrangou, B. Mollet, A. Mercenier, T. Klaenhammer, F. Arigoni, and M. A. Schell. 2004. The genome sequence of the probiotic intestinal bacterium Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:2512-2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.Schwandner, R., R. Dziarsk, H. Wesche, M. Rothe, and C. J. Kirschning. 1999. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by Toll-like receptor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17406-17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shida, K., J. Kiyoshima-Shibata, M. Nagaoka, K. Watanabe, and M. Nanno. 2006. Induction of interleukin-12 by Lactobacillus strains having a rigid cell wall resistant to intracellular digestion. J. Dairy Sci. 89:3306-3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shida, K., K. Makino, A. Morishita, K. Takamizawa, S. Hachimura, A. Ametani, T. Sato, Kumagai, S. Habu, and S. Kaminogawa. 1998. Lactobacillus casei inhibits antigen-induced IgE secretion through regulation of cytokine production in murine splenocyte cultures. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 115:278-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu-Kadota, M., M. Kiwaki, S. Sawaki, Y. Shirasawa, H. Shibahara-Sone, and T. Sako. 2000. Insertion of bacteriophage phiFSW into the chromosome of Lactobacillus casei Shirota (S-1): characterization of attachment sites and integrase gene. Gene 249:127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stingele, F., J. W. Newell, and J.-R. Neeser. 1999. Unraveling the function of glycosyltransferases in Streptococcus thermophilus Sfi6. J. Bacteriol. 181:6354-6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsukioka, Y., Y. Yamashita, T. Oho, Y. Nakano, and T. Koga. 1997. Biological function of the dTDP-rhamnose synthesis pathway in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 179:1126-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukioka, Y., Y. Yamashita, Y. Nakano, T. Oho, and T. Koga. 1997. Identification of a fourth gene involved in dTDP-rhamnose synthesis in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 179:4411-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Calsteren, M.-R., C. Pau-Roblot, A. Begin, and D. Roy. 2002. Structure determination of the exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains RW-9595M and R. Biochem. J. 363:7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaningelgem, F., M. Zamfir, F. Mozzi, T. Adriany, M. Vancanneyt, J. Swings, and L. De Vuyst. 2004. Biodiversity of exopolysaccharides produced by Streptococcus thermophilus strains is reflected in their production and their molecular and functional characteristics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:900-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Niel, C. W., C. Feudtner, M. M. Garrison, and D. A. Christakis. 2005. Lactobacillus therapy for acute infectious diarrhea in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 109:678-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, J. E., P. F. Jørgensen, M. Almlöf, C. Thiemermann, S. J. Foster, A. O. Aasen, and R. Solberg. 2000. Peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus induce tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-10 production in both T cells and monocytes in a human whole blood model. Infect. Immun. 68:3965-3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu, Y., B. E. Murray, and G. M. Weinstock. 1998. A cluster of genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis from Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Infect. Immun. 66:4313-4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamashita, Y., Y. Tsukioka, K. Tomihisa, Y. Nakano, and Y. Koga. 1998. Genes involved in cell wall localization and side chain formation of rhamnose-glucose polysaccharide in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 180:5803-5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuki, N., K. Watanabe, A. Mike, Y. Tagami, R. Tanaka, M. Ohwaki, and M. Morotomi. 1999. Survival of a probiotic, Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota, in the gastrointestinal tract: selective isolation from faeces and identification using monoclonal antibodies. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 48:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]