Abstract

A study was designed to recover Listeria monocytogenes from pasteurized milk and Minas frescal cheese (MFC) sampled at retail establishments (REs) and to identify the contamination source(s) of these products in the corresponding dairy processing plant. Fifty milk samples (9 brands) and 55 MFC samples (10 brands) were tested from REs located in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil. All milk samples and 45 samples from 9 of 10 MFC brands tested negative for L. monocytogenes; however, “brand F” of MFC obtained from REs 119 and 159 tested positive. Thus, the farm/plant that produced brand F MFC was sampled; all samples from the milking parlor tested negative for L. monocytogenes, whereas several sites within the processing plant and the MFC samples tested positive. All 344 isolates recovered from retail MFC, plant F MFC, and plant F environmental samples were serotype 1/2a and displayed the same AscI or ApaI fingerprints. Since these results established that the storage coolers served as the contamination source of the MFC, plant F was closed so that corrective renovations could be made. Following renovation, samples from sites that previously tested positive for the pathogen were collected from the processing environment and from MFC on multiple visits; all tested negative for L. monocytogenes. In addition, on subsequent visits to REs 159 and 119, all MFC samples tested negative for the pathogen. Studies are ongoing to quantify the prevalence, levels, and types of L. monocytogenes in MFC and associated processing plants to lessen the likelihood of listeriosis in Brazil.

Latin-style soft cheese, such as queso fresco (QF), has been identified in risk assessments by U.S. regulatory agencies as a food of greater concern to public health (www.foodsafety.gov/∼dms/lmr2-toc.html) due to listeriosis. Listeria monocytogenes has also been isolated from Latin-style soft cheese from South America, notably from Minas frescal cheese (MFC) in Brazil. For example, Destro et al. (13) found 2 of 20 samples (10%) of MFC made with pasteurized milk to be positive for L. monocytogenes. Delgado da Silva et al. (11) recovered L. monocytogenes from 7 of 17 samples (41%) of MFC made from raw milk and from 1 of 33 samples (3%) of MFC made from pasteurized milk. As another example, Carvalho et al. (6) recovered L. monocytogenes from 3 of 93 samples (3%) of MFC made with pasteurized milk. All positive samples were obtained from MFC manufactured using the traditional method plus the addition of lactic acid. The Brazilian standard of identity of the Common Market of the South (Mercosul) (31) defines MFC as a fresh cheese obtained by the enzymatic coagulation of milk with rennet and other appropriate coagulation enzymes; the use of lactic acid bacteria to complement the coagulation step is optional. The relatively high moisture content (55 to 58%) and pH levels (pH 5.0 to 6.3), low salt content (1.4 to 1.6%; the addition of salt is optional), absence of defined starter cultures, and considerable hand manipulation during manufacture by small and very small processors are factors that may all contribute to providing a favorable environment for contamination and survival/growth of L. monocytogenes in MFC (11, 35). However, despite their compositional similarities in moisture, salt content, and pH levels, unlike QF, which has caused human illness in the United States, MFC and other dairy products/food in Brazil have not been linked to listeriosis (19, 20), presumably because it is not listed in the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System as a disease of compulsory or immediate notification and/or because there is not a comprehensive surveillance network in Brazil to survey foods for this bacterium (4).

Numerous investigations on the presence, levels, and types of L. monocytogenes in pasteurized milk have been conducted. For example, Frye and Donnelly (15) conducted a survey for L. monocytogenes in pasteurized whole milk, nonfat milk, and chocolate milk produced in the United States. Of 5,519 samples tested over a five-week period beginning in June 2000, only 1 of 1,846 (0.018%) nonfat milk samples tested positive for this pathogen. Jayarao et al. (21, 22) isolated L. monocytogenes from 6 of 131 (5%) bulk tank milk (BTM) samples in eastern South Dakota and western Minnesota, and in a separate survey of food-borne pathogens conducted with 248 dairy herds in 16 counties in Pennsylvania, they reported that 3 of 248 (1%) corresponding BTM samples tested positive for this pathogen. In contrast, Casarotti et al. (7) did not find any species of Listeria in 20 samples each of raw milk, pasteurized milk, or MFC from retail establishments (REs) in Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil. Likewise, Nero et al. (33) did not recover L. monocytogenes from single raw milk samples from each of 210 small- to medium-sized dairy farms located in five states representing the three main milk-producing regions in Brazil. Several factors, such as the laboratory procedures performed, including their sensitivity and specificity, and the nature and number of samples tested, could, at least in part, explain the differences in the prevalence of L. monocytogenes among these various studies.

L. monocytogenes is also widespread on farms (34, 44) and in dairy-processing environments (10, 23, 30, 32, 36, 43). For example, Kabuki et al. (23) examined environmental and cheese samples from three Latin-style fresh cheese processing plants in New York City over a total of four visits to each plant. They recovered L. monocytogenes from 27 of 246 (11%) environmental samples from these processing plants. However, only finished products from one plant (7 of 24 [29%]) tested positive for L. monocytogenes. In a study conducted of two MFC processing plants in Bahia, Brazil, Silva et al. (39) isolated L. monocytogenes in one of the plants from raw milk (one of six samples was positive) and from the floor of the cheese refrigeration room (one of two samples was positive) from among a total of 118 samples representing the environment sites, food contact surfaces, and cheese. It was not possible to isolate the pathogen from among 100 similar samples that were tested in the second plant. More importantly, L. monocytogenes was not recovered from any of the cheese sampled from either of these two facilities.

Based on the association of L. monocytogenes with raw and pasteurized milk, dairy farms, cheese processing plants, and MFC and, in turn, on the potential threat of listeriosis, the primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and levels of L. monocytogenes in pasteurized milk and in MFC manufactured by a number of different processors in Brazil. A secondary objective was to conduct molecular characterization of any isolates retained from this survey to determine if there are persistent types, as well as to identify possible sources of contamination in the corresponding dairy processing plants so that corrective actions could be taken.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retail sampling.

A total of 50 pasteurized milk samples representing nine different brands (brands 1 to 9, five to seven samples per brand) were obtained from 37 separate REs (Table 1), chosen by stratified random sampling, located in five of eight areas of Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Fifty-five samples of MFC representing 10 brands (brands A to E and G to J, 5 samples per brand; brand F, 10 samples per brand) were obtained from 24 of these same 37 REs (Table 1). Both the milk and cheese samples were obtained at REs between June and October 2005 (dry/cold season). In addition, MFC was also obtained during two visits to RE 159 (one sample per visit) and four visits to RE 119 (six samples total) between January and March 2006. Samples were placed on ice and transported in cooler boxes to the Embrapa Dairy Cattle Microbiology Laboratory (Juiz de Fora, Brazil) for microbiological analyses where they were stored at 4°C and analyzed within 24 h of collection essentially as described by Hickey et al. (18).

TABLE 1.

REs in Juiz de Fora where pasteurized milk and MFC samples were obtained from June to September 2005

| Region of Juiz de Fora | Total no. of REs per region | No. of milk samples takena (no. of REs) | No. of cheese samples taken (no. of REs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central (mid) | 38 | 7, 17, 90, 114, 115, 128, 144, 169 (8) | 7, 17, 90, 114, 128, 144, 169 (7) |

| Central (north) | 21 | 95, 142, 151, 154, 160, 170, 171, 172, 173 (9) | 142, 151, 154, 172 (4) |

| Central (south) | 24 | 45, 49, 147, 164, 165, 166, 167 (7) | 45, 49, 147, 164 (4) |

| North | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Northeast | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Northwest | 19 | 65, 158, 159, 161, 162, 163 (6) | 65, 158, 159,b 162 (4) |

| West | 11 | 32, 155, 156 (3) | 155, 156 (2) |

| Southeast | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South | 12 | 119, 168 (2) | 119b (1) |

| East | 22 | 118, 157 (2) | 118, 157 (2) |

| Total | 150 | 37 | 24 |

Thirteen REs were unique for milk samples.

Positive result for L. monocytogenes in MFC.

Dairy processing plant sampling.

Plant F was surveyed for the pathogen during October 2005 (Fig. 1). Five of the 33 samples were from MFC and the remaining 28 were from raw milk, pasteurized milk, and the plant environment. Following corrective renovations of plant F, an additional 126 environmental samples (29 per each of the three visits in December 2005, March 2006, and June 2006 and 39 samples in October 2006) were examined. An additional 5 MFC samples (15 total MFC samples) obtained directly at plant F during each visit in March, June, and October 2006 were also examined for the presence of the pathogen.

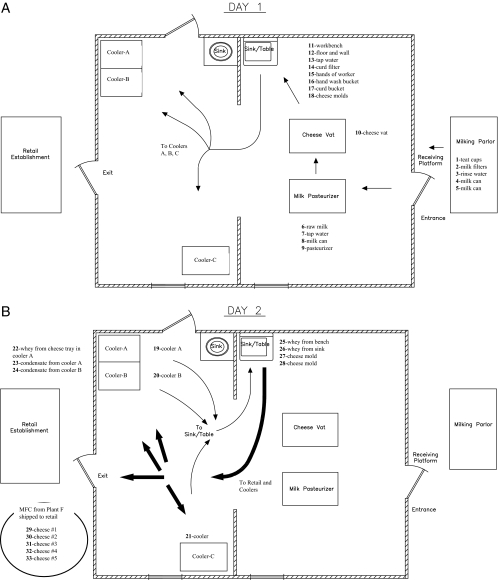

FIG. 1.

Diagram of plant F cheese processing plant. (A) Arrows indicate the flow of milk from the milking parlor to the cheese vat to form the curd, then to the sink/table to place the curd in the molds, and then to the coolers/refrigeration units for overnight storage on day 1 of production. (B) Thin arrows show the flow of cheese from the coolers/refrigeration units to the sink/table for removal from the molds and subsequent packaging on day 2 of production. Thick arrows show the flow of cheese after packaging either back to the coolers/refrigeration units for storage or for shipment from the plant to REs.

Manufacture of MFC.

In October 2005, plant F processed approximately 400 liters of milk each day from a herd owned by the cheese manufacturer that was located immediately adjacent to the plant. The herd contained 25 lactating crossbred cows (Holstein × zebu cattle). Milk was transferred in eight sanitized stainless steel vessels at ambient temperature to the dairy plant immediately after the milking that occurred twice each day. The MFC was manufactured essentially as described by Silva et al. (39) with only slight modifications. Briefly, milk was pasteurized (63°C for 30 min) in a double-walled tank and left to cool to 32°C in the same tank (Fig. 1A). Calcium chloride (20 g/100 liters of milk) (Produtos Macalé Ltda., Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil) was added, followed by the addition of rennet (1%) (Chymax; Chr. Hansen Ind. e Com. Ltda., Valinhos, SP, Brazil); the mixture was held at 35°C for 40 min to promote curd formation. The curd was cut gently into small cubes with the aid of a cutter composed of a wire string on a steel frame before the whey was drained using a strainer made of plastic. The resulting curd was placed into perforated circular cylindrical plastic molds (10 or 15 cm in diameter) (Produtos Macalé Ltda.) without the use of cheesecloth. The cheese was surface salted twice on each exposed side/face of the MFC (approximately 0.75% [wt/wt] NaCl on each side after reversing/inverting the containers every 15 min each of two times). Next, and without being pressed, the molds containing the curd were stored on trays that were placed inside three chest-type coolers/refrigeration units that were covered and maintained at approximately 4°C for 18 to 24 h to increase the firmness of the curd/cheese. The molds were removed on day 2 (Fig. 1B) from the coolers and placed onto the same sink where the cheese was hooped on day 1, so that the cheese could be removed from the molds and the excess whey could be drained. Lastly, the cheese was placed into plastic bags, 18 cm by 24 cm (ca. 500 g MFC) or 20 cm by 30 cm (ca. 1,000 g MFC), that were sealed with a twist tie and stored in the chest coolers for up to 24 h or transported directly to the marketplace for sale.

Isolation and identification of L. monocytogenes.

Pasteurized milk (1,000 ml) and cheese (500 g) samples were collected as finished packaged products at the above-mentioned REs. Swabs (CB Products, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) were used to sample teat cups and buckets from the milking parlor and associated equipment, as well as from the floor, wall, sink, coolers, milk pasteurization vat, cheese molds, and trays that had direct or indirect contact with MFC, essentially as described previously (18). Two swabs were used to sample a 50-cm2 area, and this process was repeated five times by passing the same two swabs over the same surface area of each sample. The swabs were placed in sterile tubes containing 10 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Sparks, MD) for transport to the laboratory on ice. Five milliliters of brain heart infusion broth was transferred to 45 ml of Listeria enrichment broth (LEB; Difco), and the contents were mixed at room temperature for 1 min using a stomacher (model MK 1204; ITR Instrumentos para Laboratórios Ltda., Esteio, RS, Brazil). Each sample was incubated at 30°C for 48 h. For MFC (25 g) and for test samples that were liquids, such as milk, whey, water from the sinks, and rinse water from the buckets used to transport milk (25 ml of each liquid sample), the samples were aseptically added to 225 ml of LEB, mixed as described above, and incubated at 30°C for 48 h (detection limit = ≤1 CFU per sample).

After incubation, a loopful of each LEB sample was transferred to Palcam selective agar (Difco) and to modified Oxford agar (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) plates. The plates were incubated at 35°C and examined for the presence of Listeria-like colonies after 24 and 48 h. From each selective agar plate, five presumptive Listeria colonies were streaked onto trypticase soy agar (Acumedia, Baltimore, MD) with 0.6% yeast extract (Oxoid). The plates were incubated for 48 h at 30°C. Select isolates were examined for Gram's reaction, catalase production, nitrate reduction, and motility on SIM medium, as well as for hemolysis and the CAMP reaction on 5% sheep blood agar (1). Isolates were further confirmed to be L. monocytogenes via PCR using primers targeting hlyA and genes 1 and 2 (2, 24).

Enumeration of L. monocytogenes from MFC.

Levels of L. monocytogenes in all five cheese samples obtained directly from plant F in October 2005 were determined as follows: a single 25-g portion was removed and transferred to a bag containing 225 ml of 2% sodium citrate solution, and following homogenization for 2 min at room temperature in a stomacher, each sample was serially diluted in 0.1% sterile peptone water and a total of 333 μl of the diluted sample was spread plated onto each of three modified of Oxford agar plates. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 35°C (detection limit of ≤10 CFU per 25 g of MFC).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Molecular subtyping was conducted using AscI and ApaI (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA) in accordance with the standardized CDC PulseNet protocol (17), essentially as described by Gilbreth et al. (16). The AscI-digested DNA from a laboratory control strain of L. monocytogenes (MFS1435; pulsotype 84; serotype 1/2a) was included as a reference on all gels. Pattern images were acquired using a Bio-Rad Gel Doc system with the Multi-Analyst software program (version 1.1; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and compared using the Applied Maths BioNumerics software package (version 4.0; Saint-Martins-Latem, Belgium). Pattern clustering was performed using algorithms within BioNumerics, specifically the unweighted-pair group method using arithmetic averages and the Dice correlation coefficient with a position tolerance of 1.0%.

Serotyping.

Isolates were serotyped using both a multiplex PCR assay (14) designed to identify serotypes 4b, 1/2a, and 1/2b strains and a commercially available antibody-based serotyping kit (Denka Seiken Co., Tokyo, Japan). Strains MFS-53 (F2365; serotype 4b; isolated from Jalisco cheese) (29), MFS-96 (H7858; serotype 4b; isolated from frankfurters) (9), MFS-98 (H7969; serotype 4b; isolated from frankfurters) (9), MFS-110 (F6854; serotype 1/2a; isolated from turkey frankfurters) (8), and MFS-108 (ATCC 19116; serotype 4c; isolated from chicken) (3) were used as controls.

RESULTS

Our survey of 37 REs in Juiz de Fora revealed that all 50 pasteurized milk samples and cheese from 9 of 10 MFC brands tested negative by enrichment (≤1 CFU per sample) for L. monocytogenes. However, between June and October 2005, 60% (6 of 10 samples) of MFC from one brand, brand F, tested positive. More specifically, four of six samples from RE 119 and two of four samples from RE 159 tested positive. This corresponds to a brand prevalence of 10% (1 of 10 brands) and an MFC prevalence of 11% (6 of 55 total MFC samples). Proximate composition analyses of the commercial MFC showed on average a relatively high moisture content of 56.4% (54.9 to 58%) and pH levels of 6.09 (pH 4.91 to 6.76), a low salt content of 0.85% (0.41 to 1.14%), a total solids content of 41.1% (35.4 to 45.1%), and a lipids content of 19% (17.0 to 22.5%), as is typical/expected for this type of cheese.

After finding that only one brand of cheese was contaminated with L. monocytogenes, our team in Juiz de Fora worked through proper channels to share our findings with the owner of plant F and with authorities at the Minas Gerais State Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Supervision (Instituto Mineiro de Agropecuária [IMA]/Inspeção e Fiscalização de Produtos de Origem Animal). To their credit, the producer was keenly interested in working with us and with the local authorities to identify the source(s) of contamination and make the necessary modifications to correct the problem. During the initial visit to the plant F farm/dairy in October 2005 (Fig. 1), all five samples taken from the milking parlor (bulk tank milk, teat cups, filters, milk buckets, and rinse water obtained from buckets used to carry milk) tested negative by enrichment for L. monocytogenes. However, all five samples of MFC obtained directly at plant F tested positive for the pathogen. L. monocytogenes was present at levels ranging from 2.48 to 4.28 log10 CFU/g (average = 3.64 log10 CFU/g) in these five samples. Perhaps more importantly, 10 of the 23 environmental samples taken from food contact and nonfood contact areas in the processing plant (floors, walls, sinks, refrigeration units, cheese molds, and liquid on trays, in sinks, and in refrigerators) tested positive (Fig. 1). Therefore, we studied both the plant design and cheese-making protocol to narrow down the most likely source(s) of contamination. Regarding the latter, as shown in Fig. 1, all samples which tested positive for the pathogen were sites related to day 2 of manufacturing. Areas associated with contamination were the coolers/refrigeration units wherein the cheese was stored overnight and sites that came in contact with the cheese after it was taken from the coolers/refrigeration units, such as the molds and sink area where the cheese was removed from the molds on day 2 of production. These data suggested that the excess fluid/whey within the coolers served as a point source of contamination. This hypothesis was further corroborated by the results obtained by PFGE fingerprinting of the retained isolates from each positive sample (see below).

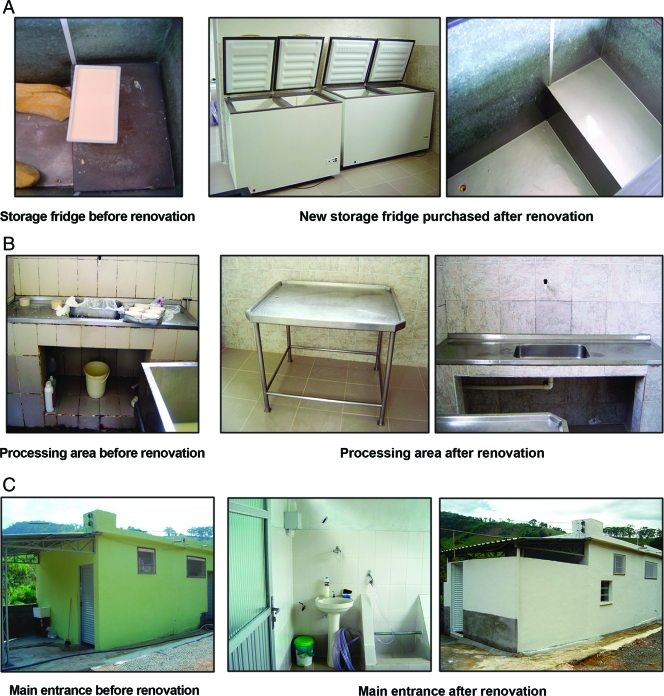

Plant F remained closed from October through December 2005, and no cheese was produced or sold, so that renovations could be made to this facility. As shown in Fig. 2, in general, most of the changes made were neither extensive nor costly. For example, broken floor and wall tiles were replaced, foot baths and sinks were installed both within and outside of the plant (Fig. 2A), windows and doors were replaced and/or properly sealed, and new sinks (Fig. 2B) and coolers/refrigeration units (Fig. 2C) were purchased and installed. In total, these modifications/renovations cost the owners of plant F less than US$5,000. This is arguably only a modest cost, considering it eliminated the source/niche of L. monocytogenes contamination and ultimately increased the amount of product made and the profitability for the producer, as well as enhanced the safety and wholesomeness of MFC produced at plant F.

FIG. 2.

Photographs of plant F before and after renovations. (A) Coolers used for storage of MFC. (B) Cheese processing area. (C) Main entrance.

After the renovations were completed, 29 sites in the plant environment were tested in December 2005 and found to be negative for L. monocytogenes. Based on our data showing the absence of L. monocytogenes in the plant environment, the local authorities gave approval for the plant to reopen. For the purposes of this research project, these same 29 sites were tested in March and June 2006 and an additional 10 sites, for a total of 39 sites, were tested in October 2006; all 97 samples tested negative for the pathogen. In addition, five MFC samples were obtained directly from plant F during the visits in March, June, and October 2006; all 15 samples tested negative for the pathogen. Furthermore, between January and March 2006, we returned to REs 119 (six samples over four visits) and 159 (one sample on each of two visits) and purchased MFC produced by plant F; all eight samples tested negative for the pathogen.

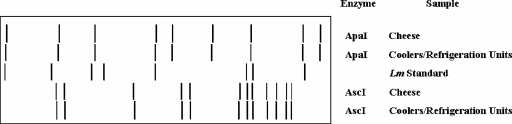

A total of 344 isolates of L. monocytogenes (5 to 20 isolates per positive sample) from retail cheese (6 samples; 88 isolates), cheese obtained directly from plant F (5 samples; 97 isolates), and environmental sites within plant F (10 samples; 159 isolates) were retained and further characterized. All 344 L. monocytogenes isolates displayed the same AscI (and ApaI) restriction endonuclease profile (REDP) which was designated as REDP 9 for AscI (Fig. 3). A subset of 24 isolates representing each sample type testing positive for the pathogen was confirmed as serotype 1/2a by both PCR and serological assays. As an aside, four representative serotype 1/2a isolates displaying REDP 9 were confirmed as DUP-1046 via automated ribotyping with EcoRI (RiboPrinter microbial characterization system; DuPont Qualicon, Wilmington, DE) (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of AscI- and ApaI-generated PFGE restriction patterns for L. monocytogenes strains isolated from a sample of MFC and from the coolers/refrigeration units. L. monocytogenes MFS1435 (serotype 1/2a) was used as the reference standard (Lm standard).

DISCUSSION

There is relatively little information about food-borne diseases in Brazil. The most-recent official data (4) refer to the period from 1999 to 2004 wherein the etiology was not established in 2,989 of 3,737 (80%) of the reported outbreaks; L. monocytogenes was not included in these statistics. Although L. monocytogenes is widespread in nature as well as in the dairy environment, our results and those of other investigators confirm that pasteurized milk is not a common source of this pathogen in Brazil (7, 39). However, our data also confirmed that MFC can be a source of L. monocytogenes to consumers even when it is prepared with pasteurized milk (6, 13, 11). The observed brand prevalence of 10% and MFC prevalence of 11% pertain specifically to the Juiz de Fora region of Brazil and may or may not be reflective of the “true” prevalence of L. monocytogenes in QF in other regions of Brazil or in other areas of the world. Our data established that plant F was the origin of contamination but did not totally exclude the possibility that MFC could also be contaminated at REs. Regardless, the fact that all 344 isolates displayed an indistinguishable PFGE pattern indicated a point source of contamination. Moreover, this specific pulsed-field profile, namely REDP 9, is unique among some 700 strains and some 70 REDP in our database. It is also of interest that strains displaying REDP 9 were subsequently ribotyped as DUP-1046. Sauders et al. (37) recovered DUP-1046 strains from ready-to-eat whitefish salad in New York state, and Manfreda et al. (27) recovered DUP-1046 strains from gorgonzola cheese in Lombardia, Italy. Although such strains have been associated with foods, it does not appear that they have been responsible for listeriosis (38). Thus, it would be interesting to further characterize such strains to determine their virulence potential and/or response to food processing and storage conditions relative to their ability to persist in foods and cause human illness. In addition, all isolates belonged to the same serotype, 1/2a, which is the second most frequent serotype recovered from clinical listeriosis in humans and the most frequent serotype found in dairy products in Brazil (19, 20). Although no illnesses were linked to the MFC produced by plant F, with the possible exception of an outbreak of febrile gastroenteritis in Sweden due to consumption of fresh cheese contaminated with a serotype 1/2a strain (5), previous listeriosis outbreaks linked to Latin-style soft cheeses have been caused by serotype 4b strains of L. monocytogenes.

Our study and others (30, 32, 44) show the importance of finding specific niches wherein L. monocytogenes can survive in the food-processing environment to more specifically direct the cleaning, disinfection, and renovation/repair efforts to these sites. No L. monocytogenes isolates were detected in raw milk, pasteurized milk, curd, or whey samples collected before the storage of cheese in the coolers/refrigeration units. This indicates that raw milk was not the source of the pathogen at the time of sampling, thus further confirming the low prevalence or absence of L. monocytogenes in raw milk from Brazilian herds (7, 33, 39). However, even if L. monocytogenes were present in raw milk, pasteurization would eliminate it. Likewise, Menendez et al. (30) recovered L. monocytogenes from 1 of 20 raw milk samples but not from 19 samples of pasteurized milk, curd, and whey. In this same study, L. monocytogenes was recovered from 8 of 31 samples obtained from several sites in the manufacturing area and in the ripening rooms (30), indicating the possibility of postpasteurization contamination. The introduction of L. monocytogenes into cheese via contaminated raw milk was also considered the cause of contamination of fresh Mexican-style cheese in California that resulted in 142 cases of human listeriosis and 48 deaths (25), as well as another outbreak in Winston-Salem, NC, in 2000 that resulted in 13 cases and 5 deaths (26).

The association of the production plant environment and equipment as primary sources of L. monocytogenes contamination in foods is common (23, 36). Moreover, inoculation of milk with L. monocytogenes confirmed that the pathogen survived the making of Mexican-style cheese (40). Suggestions of postprocessing contamination of MFC with L. monocytogenes have also been made (11, 12). These data indicate that L. monocytogenes contamination may occur both during and after cheese processing. In our case, contamination occurred during the cold storage of MFC. This assumption was based on the recovery of the pathogen only after the processed cheese was kept in the coolers/refrigeration units overnight. Moreover, all isolates of L. monocytogenes recovered from MFC obtained from both REs and directly from plant F displayed the same PFGE profile as that of isolates recovered from coolers/refrigeration units, the sink, cheese molds, and excess liquid found on trays. One could also surmise that the persistence and proliferation of the pathogen was facilitated by the cold storage conditions.

Our approach to control L. monocytogenes in the dairy plant was similar to that described by others (30, 32, 42) in the sense that improved sanitary practices, and to some extent structural changes to the plant, were made to eliminate any source of contamination or nonhygienic handling during manufacturing or storage. In our study, contamination was most likely confined to the storage environment, since replacement of two of the three refrigeration units eliminated the pathogen from within plant F. Whereas we eliminated L. monocytogenes from the plant, Unnerstad et al. (42) reported a decrease in the number of positive samples but not a complete elimination of the problem. Based on the continuing recovery of strains displaying the same serotype, 3b, from both cheese and the dairy plant environment, they suggested that some clones of L. monocytogenes survived in this environment for at least 7 years. In another study designed to characterize L. monocytogenes recovered from an ice cream plant, it was found that a predominate PFGE type persisted in this plant for 7 years (32). In our case, we were not able to recover L. monocytogenes from the finished product or from the plant environment for 12 months following the interventions that were made. Either our strain was transient in the dairy environment and/or the source of contamination was eliminated via renovation and by improving hygienic measures. Our data also indicate that the point source of contamination was the refrigeration units where cheese and other products were stored during and after processing. Cotton and White (10) reported that 12 of 16 samples from fluid milk plants that were positive for L. monocytogenes were obtained from the cooler, and they and others reported that recovery of this pathogen from cheese kept at refrigerated temperatures is not uncommon (41, 43). Success at controlling L. monocytogenes in dairy plants may vary, since it depends on a multiplicity of factors, as discussed herein and elsewhere by others (23, 43).

Our results validated that systematic culturing and analyses of products and processing facilities can identify areas that harbor L. monocytogenes. In addition, we also demonstrated that it is possible, with appropriate interventions, to eliminate harborage points within a food processing facility. Studies are ongoing to quantify the prevalence, levels, and types of L. monocytogenes on dairy farms and in dairy processing plants to better manage the threat of listeriosis in Latin-style fresh cheese.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals and organizations who contributed significantly to the initiation or conduct of the project per se and/or the analyses of the resulting data: Rosemary Martinjuk, Brad Shoyer, Ellen Sanders, and John P. Cherry (USDA/ARS/ERRC, Wyndmoor, PA); Cristobal Chiadez and Jorge Sillier (CIAD, Culiacan, Mexico); Carlos Rodriguez, Airdem Assis, Pedro Arrares, and Gretchen Flanley (USDA/ARS/OIRP, Beltsville, MD); Paulo do Carmo Martins, Pedro Braga Arcuri, Marcos A. S. Silva, Abiah N. I. Abreu, Alessandra P. Sant'Anna, Carolina F. S. Vasconcellos, and Gilmara B. de Paula (Embrapa, Dairy Cattle National Research Center, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil); the Minas Gerais State Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Supervision (Instituto Mineiro de Agropecuária Inspeção e Fiscalização de Produtos de Origem Animal IMA-MG); and the Brazilian Council for Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq).

Emilia M. P. Santos is a recipient of the CNPq scholarship. This work was financially supported by PRODETAB (047-02/99) and FAPEMIG (2411/05).

The mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bille, J., J. Rocourt, and B. Swaminathan. 2003. Listeria and Erysipelothrix, p. 461-471. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 2.Border, P. M., J. J. Howard, G. S. Plastow, and K. W. Siggens. 1990. Detection of Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes using polymerase chain reaction. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 11:158-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brosch, R., J. Chen, and J. B. Luchansky. 1994. Pulsed-field fingerprinting of listeriae: identification of genomic divisions for Listeria monocytogenes and their correlation with serovar. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2584-2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmo, G. M. I., A. A. Oliveira, C. P. Dimech, D. A. Santos, M. G. Almeida, L. H. Berto, R. M. S. Alves, and E. H. Carmo. 2005. Vigilância epidemiológica das doenças transmitidas por alimentos no Brasil, 1999-2004. Bol. Eletrôn. Epidemiol. 5(6):1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrique-Mas, J. J., I. Hokeberg, Y. Andersson, M. Arneborn, W. Tham, M. L. Danielsson-Tham, B. Osterman, M. Leffler, M. Steen, E. Eriksson, G. Hedin, and J. Giesecke. 2003. Febrile gastroenteritis after eating on-farm manufactured fresh cheese—an outbreak of listeriosis? Epidemiol. Infect. 130:79-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho, J. D. G., W. H. Viotto, and A. Y. Kuaye. 2007. The quality of Minas frescal cheese produced by different technological processes. Food Control 18:262-267. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casarotti, V. T., C. R. Gallo, and R. Camargo. 1994. Ocorrência de Listeria monocytogenes em leite cru, leite pasteurizado tipo C e queijo Minas frescal comercializados em Piracicaba, SP. Arch. Latin Nutr. 44:158-163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1989. Epidemiologic notes and reports listeriosis associated with consumption of turkey franks. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 38:267-268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1998. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1998. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:1085-1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotton, L. N., and C. H. White. 1992. Listeria monocytogenes, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Salmonella in dairy plant environments. J. Dairy Sci. 75:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado da Silva, M. C., E. Hofer, and A. Tibana. 1998. Incidence of Listeria monocytogenes in cheese produced in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Food Prot. 61:354-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado da Silva, M. C., M. T. Destro, E. Hofer, and A. Tibana. 2001. Characterization and evaluation of some virulence markers of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from Brazilian cheeses using molecular, biochemical and serotyping techniques. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 63:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Destro, M. T., A. M. Serrano, and D. Y. Kabuki. 1991. Isolation of Listeria species from some Brazilian meat and dairy products. Food Control 2:110-112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doumith, M., C. Buchrieser, P. Glaser, C. Jacquet, and P. Martin. 2004. Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3819-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frye, C., and C. W. Donnelly. 2005. Comprehensive survey of pasteurized fluid milk produced in the United States reveals a low prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 68:973-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbreth, S. E., J. E. Call, F. M. Wallace, V. N. Scott, Y. Chen, and J. B. Luchansky. 2005. Relatedness of Listeria monocytogenes isolates recovered from selected ready-to-eat foods and listeriosis patients in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8115-8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graves, L. M., and B. Swaminathan. 2001. PulseNet standardized protocol for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes by macrorestriction and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 65:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickey, P. J., C. E. Beckelheimer, and T. Parrow. 1992. Microbiological tests for equipment, containers, water, and air, p. 397-412. In R. T. Marshal (ed.), Standard methods for examination of dairy products, 16th ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC.

- 19.Hofer, E., C. M. F. Reis, and C. B. Hoffer. 2006. Serovars of Listeria monocytogenes and related species isolated from human clinical specimens. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 39:32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofer, E., R. Ribeiro, and D. P. Feitosa. 2000. Species and serovars of the genus Listeria isolated from different sources in Brazil from 1971 to 1997. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 95:615-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayarao, B. M., and D. R. Henning. 2001. Prevalence of foodborne pathogens in bulk tank milk. J. Dairy Sci. 84:2157-2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayarao, B. M., S. C. Donaldson, B. A. Straley, A. A. Sawant, N. V. Hegde, and J. L. Brown. 2006. A survey of foodborne pathogens in bulk tank milk and raw milk consumption among farm families in Pennsylvania. J. Dairy Sci. 89:2451-2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kabuki, D. Y., A. Y. Kuaye, M. Wiedmann, and K. J. Boor. 2004. Molecular subtyping and tracking of Listeria monocytogenes in Latin-style fresh-cheese processing plants. J. Dairy Sci. 87:2803-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange, C., N. D. Peres, E. F. Arcuri, M. A. V. P. Brito, J. R. F. Brito, P. M. Garcia, and M. M. O. P. Cerqueira. 2005. Identificação de Listeria monocytogenes pela reação em cadeia da polimerase. Rev. Inst. Lat. Cândido Tostes 60:150-153. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linnan, M. J., L. Mascola, X. D. Lou, V. Goulet, S. May, C. Sainen, D. W. Hird, M. L. Yonekura, P. Hayes, R. Weaver, A. Audurier, B. D. Plikaytis, S. L. Fannin, A. Kleks, and C. V. Broome. 1988. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N. Engl. J. Med. 319:823-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald, P. D. M., R. E. Whitwam, J. D. Boggs, J. N. MacCormack, K. L. Anderson, J. W. Reardon, J. R. Saah, L. M. Graves, S. B. Hunter, and J. Sobel. 2005. Outbreak of listeriosis among Mexican immigrants as a result of consumption of illicitly produced Mexican-style cheese. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:677-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manfreda, G., A. De Cesare, S. Stella, M. Cozzi, and C. Cantoni. 2005. Occurrence and ribotypes of Listeria monocytogenes in gorgonzola cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 102:287-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reference deleted.

- 29.Mascola, L., L. Lieb, J. Chiu, S. L. Fannin, and M. J. Linnan. 1988. Listeriosis: an uncommon opportunistic infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A report of five cases and a review of the literature. Am. J. Med. 84:162-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menendez, S., M. R. Godinez, J. L. Rodrigues-Otero, and J. A. Centeno. 1997. Removal of Listeria spp. in a cheese factory. J. Food Saf. 17:133-139. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercosul. 1996. Regulamento técnico Mercosul de identidade e qualidade do queijo Minas frescal. Resolução Mercosul/GMC/Research article no. 145/96.

- 32.Miettinen, M. K., K. J. Björkroth, and H. J. Korkeala. 1999. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes from an ice cream plant by serotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 46:187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nero, L. A., M. R. de Mattos, V. Beloti, M. A. F. Barros, D. P. Netto, J. P. A. N. Pinto, N. J. de Andrade, W. P. Silva, and B. D. G. M. Franco. 2004. Hazards in non-pasteurized milk on retail sale in Brazil: prevalence of Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes and chemical residues. Braz. J. Microbiol. 35:211-215. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nightingale, K. K., Y. H. Schukken, C. R. Nightingale, E. D. Fortes, A. J. Ho, Z. Her, Y. T. Grohn, P. L. McDonough, and M. Wiedmann. 2004. Ecology and transmission of Listeria monocytogenes infecting ruminants and in the farm environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4458-4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pereira, M. M. G., M. T. Lima, and M. F. S. Santana. 2006. Queijo Minas frescal. Comunicado Técnico 12:1-4. Universidade Federal do Piauí, Centro de Ciências Agrárias, Teresina, Piauí, Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pritchard, T. J., K. J. Flanders, and C. W. Donnelly. 1995. Comparison of the incidence of Listeria on equipment versus environmental sites within dairy processing plants. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 26:375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauders, B. D., K. Mangione, C. Vicent, J. Schermerhorn, C. M. Farchione, N. B. Dumas, D. Bopp, L. Kornstein, E. D. Fortes, K. Windham, and M. Wiedmenn. 2004. Distribution of Listeria monocytogenes molecular subtypes among human and food isolates in New York state shows persistence of human disease-associated Listeria monocytogenes strains in retail environments. J. Food Prot. 67:1417-1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauders, B. D., Y Schukken, L. Kornstein, V. Reddy, T. Bannerman, E. Salehi, N. Dummas, B. J. Anderson, J. P. Massey, and M. Wiedmenn. 2006. Molecular epidemiology and cluster analysis of human listeriosis cases in three U.S. states. J. Food Prot. 69:1680-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva, I. M. M., R. C. C. Almeida, M. A. O. Alves, and P. F. Almeida. 2003. Occurrence of Listeria spp. in critical control points and the environment of Minas frescal cheese processing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 81:241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solano-López, C., and H. Hernández-Sánchez. 2000. Behaviour of Listeria monocytogenes during the manufacture and ripening of Manchego and Chihuahua Mexican cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 62:149-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uhlich, G. A., J. B. Luchansky, M. L. Tamplin, F. J. Molina-Corral, S. Anandan, and A. C. S. Porto-Fett. 2006. Effect of temperature on viability of Listeria monocytogenes in queso blanco. J. Food Saf. 26:202-214. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unnerstad, H., E. Bannerman, J. Bille, M. L. Danielsson-Tham, E. Waak, and W. Tham. 1996. Prolonged contamination of a dairy with Listeria monocytogenes. Neth. Milk Dairy J. 50:493-499. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker, R. L., L. H. Jensen, H. Kinde, A. V. Alexander, and L. S. Owens. 1991. Environmental survey for Listeria species in frozen milk product plants in California. J. Food Prot. 54:178-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshida, T., Y. Kato, M. Sato, and K. Hirai. 1998. Sources and routes of contamination of raw milk with Listeria monocytogenes and its control. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 60:1165-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]