Abstract

Sepsis is a serious disease with high mortality in newborns. It is very important to have a convenient and accurate method for pathogenic diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. We developed a method of simultaneous detection and Gram classification of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens causing sepsis directly from blood samples with Gram stain-specific-probe-based real-time PCR (GSPBRT-PCR). With GSPBRT-PCR, 53 clinically important strains representing 25 gram-positive and 28 gram-negative bacterial species were identified correctly with the corresponding Gram probe. The limits of the GSPBRT-PCR assay in serial dilutions of the bacteria revealed that Staphylococcus aureus could be detected at concentrations of 3 CFU per PCR and Escherichia coli at concentrations as low as 1 CFU per PCR. The GSPBRT-PCR assay was further evaluated on 600 blood specimens from patients with suspicioon of neonatal sepsis and compared to the results obtained from blood cultures. The positive rate of the GSPBRT-PCR array was 50/600 (8.33%), significantly higher than that of blood culture (34/600; 5.67%) (P = 0.00003). When blood culture was used as a control, the sensitivity of GSPBRT-PCR was 100%, the specificity was 97.17%, and the index of accurate diagnosis was 0.972. This study suggests that GSPBRT-PCR is very useful for the rapid and accurate diagnosis of bacterial infection and that it can have an important impact on the current inappropriate and unnecessary use of antibiotics in the treatment of newborns.

Sepsis is a serious disease with high mortality in newborns, particularly in preterm, low-birth-weight infants (15, 22). A fast and correct diagnosis, followed by rapid treatment, plays an important role in the reduction of infant mortality resulting from sepsis. Currently, bacterial culture is required as a standard method for diagnosis of the presence of bacterial pathogens in clinical samples. However, this technique has some disadvantages with regard to the desired rapidity and sensitivity (28). Bacterial-culture results require 48 h to 72 h at least. Generally, samples are incubated for 5 days or until they show a positive signal in the continuously monitored blood culture systems for detection of bacterial sepsis. Moreover, the culture may lead to false-negative results when fastidious or slowly growing bacteria are involved or when samples are obtained after antimicrobial therapy has been started (10, 13). The early diagnosis and adequate treatment of bacterial infections have a great impact on the outcome of patients with systemic infection.

Recently, PCR-based assays have been seen as having the potential to provide an early and accurate diagnosis of diseases caused by bacterial pathogens and have improved the rate of microbial detection. The sequence of the 16S rRNA gene has been used to diagnose and identify bacterial infection in clinical practice (6, 27). Some PCR-based assays can be used to identify specific bacterial pathogens (16, 32), while broad-range bacterial PCR can detect almost any bacterial species (25, 33). The use of broad-range bacterial PCR has a great advantage: it can detect microorganisms that are found less frequently or even unknown causative agents of bacterial origin. However, most published PCR protocols have not been used in clinical diagnosis, since they either are time-consuming or have a risk of contamination. Conventional PCR is difficult to use for routine diagnosis due to the time required for sample handling and post-PCR analysis. Thus, it is necessary to develop a reliable broad-range detection system for bacterial DNA from clinical samples that is fast and easy to use and covers a wide range of clinically relevant microbes. Until now, broad-range real-time PCR assays have seldom been devised to identify bacterial DNA detected directly from clinical samples (18, 23). Additionally, the simultaneous quantification and differentiation of a Gram stain with a broad-range real-time PCR in clinical blood samples is rarely described.

In this study, we describe a Gram stain-specific-probe-based real-time PCR (GSPBRT-PCR) system involving the 16S rRNA gene that allows simultaneous detection and discrimination of clinically relevant gram-positive and -negative bacteria directly from blood samples. A total of 600 blood specimens from neonates with suspected bacterial infections were evaluated. The system may provide more rapid and accurate diagnosis of bacterial infection in sick neonates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains used in this study and their sources are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were obtained in the form of frozen cell pellets, streaks, or lyophilized cells. Prior to DNA extraction, each strain was streaked on chocolate or blood agar and examined for the proper colony morphology. In addition, Gram staining was performed to confirm the identification. For negative controls, we used the total human genome, cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

TABLE 1.

Representative bacterial species detected by GSPBRT-PCR using a pair of specific probes

| Genus | Species | GSPBRT-PCR CTa

|

GenBank accession no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G+ probe | G− probe | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||||

| Bacillus | B. subtilis | 16.28 ± 1.08 | AB065370 | |

| Enterococcus | E. avium | 17.67 ± 0.24 | AJ301825 | |

| E. faecalis | 19.26 ± 1.28 | AJ276460 | ||

| E. faecium | 16.37 ± 0.08 | AJ874342 | ||

| Listeria | L. monocytogenes | 17.10 ± 0.24 | AY946290 | |

| Staphylococcus | S. aureus | 16.97 ± 0.45 | X68417 | |

| S. auricularis | 20.47 ± 0.77 | D83358 | ||

| S. capitis | 16.32 ± 0.15 | AY030321 | ||

| S. cohnii | 19.21 ± 1.32 | AJ717378 | ||

| S. epidermidis | 21.06 ± 0.19 | L37605 | ||

| S. haemolyticus | 20.17 ± 0.97 | L37600 | ||

| S. hominis | 22.45 ± 0.97 | AY030318 | ||

| S. hyicus | 22.70 ± 0.41 | D83368 | ||

| S. lentus | 18.24 ± 0.28 | D83370 | ||

| S. saprophyticus | 21.49 ± 0.46 | D83371 | ||

| S. schleiferi | 24.45 ± 0.37 | D83372 | ||

| S. simulans | 16.56 ± 0.26 | D83373 | ||

| S. warneri | 18.62 ± 0.73 | L37603 | ||

| S. xylosus | 19.01 ± 1.49 | D83374 | ||

| Streptococcus | S. agalactiae | 17.24 ± 0.28 | AB023574 | |

| S. mitis | 23.45 ± 0.72 | AY005045 | ||

| S. mutans | 22.21 ± 0.42 | AF139603 | ||

| S. pneumoniae | 21.87 ± 0.45 | AF003930 | ||

| S. pyogenes | 17.12 ± 0.54 | AB023575 | ||

| S. sanguis | 19.10 ± 1.58 | AF003928 | ||

| Gram-negative bacteria | ||||

| Citrobacter | C. braakii | 20.45 ± 0.56 | AF025368 | |

| C. freundii | 20.78 ± 0.45 | AM184281 | ||

| Edwardsiella | E. tarda | 16.79 ± 0.48 | DQ233654 | |

| Enterobacter | E. aerogenes | 14.85 ± 0.76 | AJ251468 | |

| E. cloacae | 21.81 ± 0.82 | AJ251469 | ||

| Escherichia | E. coli | 16.35 ± 0.36 | AF233451 | |

| Haemophilus | H. influenzae | 24.38 ± 0.38 | AF224306 | |

| H. haemolyticus | 23.33 ± 0.46 | M75045 | ||

| Klebsiella | K. oxytoca | 19.11 ± 0.66 | EF127829 | |

| K. pneumoniae | 18.05 ± 0.38 | AF130981 | ||

| Neisseria | N. meningitidis | 22.18 ± 0.34 | AF059671 | |

| Pasteurella | P. haemolytica | 19.78 ± 0.56 | M75080 | |

| P. multocida | 20.55 ± 0.48 | DQ228979 | ||

| P. trehalosi | 21.30 ± 0.38 | DQ841185 | ||

| Proteus | P. mirabilis | 16.52 ± 0.44 | AF008582 | |

| P. penneri | 17.45 ± 1.07 | AJ634474 | ||

| P. vulgaris | 20.22 ± 0.32 | AJ301683 | ||

| Providencia | P. alcalifaciens | 22.22 ± 0.45 | AJ301684 | |

| P. rettgeri | 21.38 ± 0.52 | AM040492 | ||

| P. stuartii | 23.67 ± 0.56 | AM040491 | ||

| Pseudomonas | P. aeruginosa | 22.75 ± 0.41 | AF094720 | |

| Salmonella | S. enterica serovar Paratyphi | 23.06 ± 0.40 | X80682 | |

| S. enterica serovar Typhi | 23.06 ± 0.88 | U88545 | ||

| Serratia | S. marcescens | 21.48 ± 0.34 | EF035134 | |

| S. plymuthica | 22.20 ± 0.50 | EF064206 | ||

| Shigella | S. dysenteriae | 20.74 ± 0.55 | X96966 | |

| Yersinia | Y. enterocolitica | 18.55 ± 0.50 | AF366378 | |

| Y. pestis | 17.35 ± 0.78 | AF366383 | ||

Mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Clinical blood samples and patients.

From January 2005 to January 2007, a total of 600 blood specimens from different patients from the neonatal ward and the neonatal intensive care unit of Children's Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, who were clinically suspected to have bacterial infections or to be susceptible to infections were evaluated. The ages of the 600 patients (275 female and 325 male) ranged from 1 day to 28 days; 108 patients were preterm infants, and the remainder were term infants. Symptoms and signs of suspected bacterial sepsis were multiple and nonspecific. Patients with the following categories of clinical findings were enrolled: fever or temperature instability (n = 135; 22.5%), jaundice (n = 113; 18.3%), respiratory distress (n = 110; 18.3%), digestive manifestation (n = 94; 15.7%), neurological findings (n = 71; 11.8%), and others (n = 77; 12.8%). In addition, 30 blood specimens from healthy neonates served as negative controls. Bacteria were detected by blood culture and GSPBRT-PCR simultaneously. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all the participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects of Zhejiang University.

Design of primers and Gram stain-specific probes.

The designed primers and probe sets were based on regions of identity within the 16S rRNA gene following the alignment of sequences of the group's clinical bacterial pathogens outlined in Table 1. A 228-bp DNA fragment spanning nucleotides 967 to 1194 of the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene was amplified by the forward primer (p967F) and reverse primer (p1194R). The gram-positive TaqMan probe was the reverse complement of nucleotides 1056 to 1076 of the Staphylococcus aureus 16S rRNA gene. The gram-negative TaqMan probe was the reverse complement of nucleotides 1045 to 1065 of the E. coli 16S rRNA gene (Table 2). The BLAST search results showed that the primers and probes were specific for the 16S rRNA gene of the domain Bacteria. The primers and probes were synthesized by TAKARA.

TABLE 2.

Primers and probes used in this study

| Primer or probe | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Tmb (°C) | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward primer (P967F) | CAACGCGAAGAACCTTACC | 59.2 | 967-985 |

| Reverse primer (P1194R) | ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC | 59.0 | 1194-1177 |

| Gram-positive probe | 5′-FAM-ACGACAACCATGCACCACCTG-TAMRA-3′ | 69.2 | 1076-1056c |

| Gram-negative probe | 5′-HEX-ACGACAGCCATGCAGCACCT-TAMRA-3′ | 68.0 | 1065-1045d |

FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine; HEX, 6-carboxyhexachlorofluorescein.

Tms (melting temperatures) were calculated with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems).

Numbered according to the 16S rRNA gene of S. aureus (GenBank accession number X68417).

Numbered according to the 16S rRNA gene of E. coli (GenBank accession number AF233451).

DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted with the QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was extracted from 200-μl aliquots of EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood. Twenty microliters of Qiagen proteinase K (20 mg/ml) was added for every 200 μl of whole blood processed, along with an equal volume (200 μl) of buffer AL, and the sample was incubated for 30 min at 56°C. After incubation, an equal volume (200 μl) of 100% ethanol was added, and the resulting lysate was loaded onto the QIAamp DNA mini kit column (Qiagen) and washed with 500 μl of buffers AW1 and AW2 successively. Finally, the purified nucleic acids were eluted with 100 μl of Qiagen buffer AE. A 0.2-μm filter was used to filter the following reagents before use: proteinase K, ethanol, AW1, AW2, and Qiagen buffer AE.

GSPBRT-PCR.

The real-time PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 50 μl with the Line Gene Sequence Detection System (Bioer). The reaction mixtures comprised 400 nM (each) forward and reverse primers, 100 nM (each) gram-positive and -negative respective fluorescence-labeled specific probes, 1 U of mTP Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma), and 5 μl of template DNA, and water was added to give a final volume of 50 μl for each sample. The PCR mixture, except for Taq DNA polymerase, was filtered with a 0.2-μm filter device (Millipore Corp). Positive and negative controls were included throughout the procedure. No-template controls with water instead of template DNA were incorporated in each run under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 62°C for 1 min. The bacterial load was quantified by determining the cycle threshold (CT), i.e., the number of PCR cycles required for the fluorescence to exceed a value significantly higher than the background fluorescence. We assumed a threshold value of 2.0, which was approximately 10 times the background fluorescence, defined as the mean fluorescence value of the first 6 to 15 PCR cycles (13, 26).

Sequencing of amplified products from clinical samples.

Amplified DNA was sequenced with an ABI 3730 automated DNA sequencer, using the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator. The sequences obtained were compared with sequences in the GenBank database for species assignment.

Blood culture.

Between 1.0 and 2.0 ml of blood was obtained and inoculated into 20-ml BacT/Alert PF culture bottles (bioMérieux, France) under sterile conditions. Bottles from each culture set were placed in the BacT/Alert 3D Microbial Detection System (bioMérieux, France) and incubated for 5 days or until they gave a positive signal. Subcultures were performed once the continuously monitored blood culture systems recorded a positive signal. The liquid culture medium was removed from each culture bottle aseptically to a blood agar plate and a chocolate agar plate and incubated. Subsequent identification of microorganisms was performed with a Vitek-60 microorganism autoanalysis system.

Statistical analysis.

The results were analyzed using SPSS software (version 11.5). Quantitative data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. McNemar's test with the continuity correction was performed to analyze the association between the results of GSPBRT-PCR and blood culture. Two-tailed P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Specificity of GSPBRT-PCR.

The feasibility of the GSPBRT-PCR technique in detecting DNA from bacteria was determined for 53 clinically important strains representing 25 gram-positive and 28 gram-negative bacterial species (Table 1). These bacterial species accounted for more than 95% of the clinical bacteria identified from blood cultures in our hospital during the past few years. The Gram stain-specific probes appeared to be quite specific. All gram-positive bacteria examined showed fluorescence signals, for which the CT values were in the range of 16.28 to 24.45, and the gram-negative bacteria showed no fluorescence with the gram-positive probe. When tested with the gram-negative probe, DNAs from all of the gram-negative species were positive, with a range of CT values from 14.85 to 24.38, and the gram-positive bacteria showed no fluorescence. No fluorescence was detected and no cross-reaction was shown to DNAs extracted from the human genome, CMV, HBV, and EBV in this test (data not shown).

Sensitivities of GSPBRT-PCR.

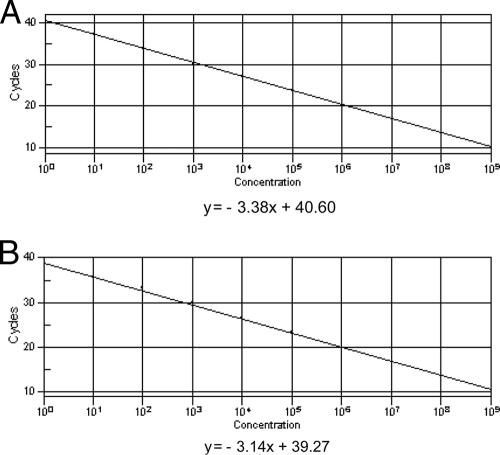

Targets were S. aureus as a representative of gram-positive bacteria and E. coli as a representative of gram-negative bacteria. To determine the detection range, we prepared a 10-fold dilution series from 108 CFU/ml to 100 CFU/ml. The limits of the GSPBRT-PCR assay in serial dilutions of the bacteria revealed that S. aureus could be detected at a concentration of 3 CFU per PCR with the gram-positive probe (CT value = 37.86) and E. coli at a concentration as low as 1 CFU per PCR with the gram-negative probe (CT value = 39.25) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the standard curves of the Gram stain-specific probes from serial dilutions of bacteria. (A) Standard curve of G+ probe for S. aureus. (B) Standard curve of G− probe for E. coli.

Results of GSPBRT-PCR and bacterial culture.

A total of 600 blood samples were analyzed by both blood culture and GSPBRT-PCR. The results were in complete accordance for 584 specimens (97.33%) when detected by the two methods, including 34 culture-positive/PCR-positive samples and 550 culture-negative/PCR-negative samples (Table 3). There were 50 positive results (50/600; 8.33%) with GSPBRT-PCR and 34 positive results (34/600; 5.67%) with blood culture. The positive rate of GSPBRT-PCR was significantly higher than that of blood culture (P = 0.00003). In the results of biochemical identification for the 34 culture-positive/PCR-positive samples, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) were identified most commonly, with a total of 20 cases, followed by S. aureus (n = 3), E. coli (n = 2), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 2), Citrobacter freundii (n = 1), Streptococcus agalactiae (n = 1), Enterococcus avium (n = 1), Enterococcus faecium (n = 1), Corynebacterium sp. (n = 1), Acinetobacter lwoffii (n = 1), and Sphingomonas paucimobilis (n = 1) (Table 4). Thirty blood samples from healthy neonates were confirmed to be negative by both blood culture and GSPBRT-PCR.

TABLE 3.

Overall results obtained by GSPBRT-PCR compared to blood culturea

| GSPBRT-PCR result | Blood culture result

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Positive | 34 | 16 | 50 |

| Negative | 0 | 550 | 550 |

| Total | 34 | 566 | 600 |

McNemar's test; P = 0.00003.

TABLE 4.

Summary of 34 culture-positive samples and the corresponding GSPBRT-PCR results

| Culture identification | No. of samples | GSPBRT-PCR result

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram+/− | Ranged CT value | Avg CT value | ||

| CoNS | 20 | + | 27.02-34.65 | 32.12 |

| S. aureus | 3 | + | 26.17-31.78 | 29.79 |

| E. coli | 2 | − | 27.89-32.56 | 30.23 |

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | − | 29.46-33.16 | 31.31 |

| C. freundii | 1 | − | 31.37 | 31.37 |

| S. agalactiae | 1 | + | 31.50 | 31.50 |

| E. avium | 1 | + | 28.21 | 28.21 |

| E. faecium | 1 | + | 29.80 | 29.80 |

| Corynebacterium sp. | 1 | + | 33.21 | 33.21 |

| A. lwoffii | 1 | − | 33.56 | 33.56 |

| S. paucimobilis | 1 | − | 34.00 | 34.00 |

For 16 culture-negative and GSPBRT-PCR-positive (culture-negative/PCR-positive) samples, the CT values ranged from 27.31 to 35, with an average and median CT value of 32.01 and 32.65, respectively. The 16 PCR-positive amplifications gave 10 positive results and seven interpretable sequences after sequencing. In these seven interpretable samples, S. pneumoniae was identified twice and Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, S. agalactiae, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis were identified once each (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

PCR-positive/culture-negative samples analyzed by sequence and clinical diagnosis

| Case no. | CT | No. of CFU | Gram+/− | Sequence | Clinical symptom | CRP (mg/liter)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27.31 | 6.30 × 103 | − | H. influenzae | Sepsis | 30 |

| 2 | 28.51 | 3.80 × 103 | + | S. pneumoniae | Pneumonia | 8 |

| 3 | 30.74 | 8.30 × 102 | + | S. pneumoniae | Pneumonia | 24 |

| 4 | 30.84 | 7.76 × 102 | + | S. haemolyticus | Hyperbilirubinemia | 8 |

| 5a | 31.03 | 6.76 × 102 | + | L. monocyogenes | Sepsis | 68 |

| 6 | 31.18 | 6.17 × 102 | + | S. agalactiae | Sepsis | 15 |

| 7 | 31.56 | 4.72 × 102 | + | S. epidermidis | Cyanosis | 53 |

| 8 | 32.65 | 2.25 × 102 | + | Equivocal | Sepsis | 4 |

| 9a | 32.65 | 2.25 × 102 | + | Equivocal | Sepsis | 102 |

| 10a | 32.70 | 2.18 × 102 | + | Equivocal | Pneumonia | 14 |

| 11 | 32.82 | 2.01 × 102 | + | Failed | Premature infant | 6 |

| 12 | 33.30 | 1.44 × 102 | + | Failed | Pneumonia | 2 |

| 13a | 33.24 | 8.32 × 101 | − | Failed | Sepsis | 28 |

| 14 | 34.21 | 7.76 × 101 | + | Failed | Sepsis | 34 |

| 15 | 34.43 | 6.70 × 101 | + | Failed | Sepsis | 45 |

| 16a | 35.00 | 2.23 × 101 | − | Failed | Blood in stool | 134 |

Patient was pretreated with antibiotics.

CRP, complement-reactive protein. The detection limit was 1 mg/liter, and a serum value of >8 mg/liter was defined as abnormally elevated.

Overall performance of the GSPBRT-PCR assay compared to blood culture.

The time required to do testing is very important for early diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. For blood culture, it normally took more than 5 days to get clinical reports, while when we used the GSPBRT-PCR assay, it took no more than 3 h. At the same time, the positive rate of the GSPBRT-PCR assay (50/600; 8.33%) was significantly higher than that of blood culture (34/600; 5.67%) (P = 0.00003). When blood culture was used as a control, the sensitivity of GSPBRT-PCR was 100%, the specificity was 97.17%, and the index of accurate diagnosis was 0.972 (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Current DNA-based Gram classification methods include Gram stain-specific PCR (20), nested PCR (5), and PCR followed by probe hybridization (1, 11, 30), but all of these methods are time-consuming and contain at least two sequential steps. Real-time PCR is a promising tool for the detection of bacterial DNA from biological fluids. Fluorescence hybridization probes result in fast detection of small amounts of bacterial DNA and correct Gram classification (19). In this study, we developed a new method of simultaneous quantification and Gram classification for bacterial pathogens with GSPBRT-PCR and diagnosed neonatal sepsis directly from blood samples. The GSPBRT-PCR assay was rapid; it usually took no more than 3 h to complete the whole experiment, which included only 1 h of sample preparation and 1.5 h for DNA amplification, because thermal cycling was much faster and amplicon detection was performed in real time. It allowed the rapid quantification and Gram classification of bacteria without the need for post-PCR processing. For blood culture, it usually took 2 to 5 days for the initial culture, followed by 2 to 3 days for subculture and identification.

In our previous study (29), we used microarray hybridization of the 16S rRNA gene to detect bacterial infection in neonatal sepsis. The method showed excellent specificity and sensitivity in the identification of bacterial strains. In this study, we evaluated Gram stain-specific probes followed by a real-time PCR assay using universal primer pairs targeting the 16S rRNA gene. The results showed that the GSPBRT-PCR system was specific for the bacteria tested. It allowed simultaneous detection and discrimination of gram-positive and -negative bacteria by means of fluorescence hybridization probes in one PCR tube. No fluorescence was detected, and no cross-reaction was found using DNA extracted from the human genome, CMV, HBV, or EBV.

To determine the detection limits of GSPBRT-PCR, S. aureus and E. coli were used to establish the standard curve and to detect the limits of the assay, based on a series of 10-fold dilutions. We found an inverse linear relationship of CT values versus template DNA serially diluted 1:10 from 1 × 105 CFU to 1 × 101 CFU using GSPBRT-PCR (Fig. 1). The linear relationship between serial dilutions of the bacteria and CT should be considered for determining the significant detection limits. The arbitrary definition of the clinically significant bacterial concentration was a CT value three CT values lower than the mean CT value from the negative template control. This definition was chosen to have a nearly 10-fold-higher concentration of detectable DNA in the positive samples than in the negative template control samples (34). In our assays, the negative template control showed CT values between 38 and 40. This induced us to establish a cutoff value of 35 cycles (14). Thus, CT values of ≤35 cycles were scored as positive results. According to this criterion, we could roughly measure as few as 40 CFU of S. aureus and 20 CFU of E. coli per PCR by GSPBRT-PCR when the CT values reached 35 cycles (Fig. 1). These detection limits are among the lowest reported up to the present (24, 34). In addition, multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene were present in a single bacterial cell on the chromosomes of most bacteria in the GenBank database (NCBI). Therefore, it could be concluded that the detection limit of GSPBRT-PCR could reach nearly 1 power of 10 in the copy number of the bacteria per PCR.

Our 16S rRNA gene GSPBRT-PCR proved to be extremely valuable in detecting bacterial sepsis compared to routine culture. Table 3 illustrates the results for 34 positive samples for which conventional and molecular methods were in complete concordance. CoNS were identified most often by blood culture, with a total of 20 cases. The gram-positive probe showed positive results for all 20 samples by GSPBRT-PCR, for which CT values ranged from 27.02 to 34.65 with an average CT value of 32.12. CoNS were reported to be the major causative microorganisms in neonatal nosocomial sepsis (21, 31).

GSPBRT-PCR also proved to be extremely valuable in cases where bacterial pathogens were fastidious and had special growth requirements or patients were pretreated with antibiotics (2, 13). For 16 PCR-positive/culture-negative samples, the 16 amplifications considered positive gave 10 positive results after sequencing and seven interpretable sequences. In two of these samples, Streptococcus pneumoniae was identified, and in the other five, H. influenzae, L. monocytogenes, S. agalactiae, S. haemolyticus, and S. epidermidis were each detected once (Table 5). H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, and S. agalactiae are fastidious bacteria with unusual growth requirements, growing more slowly in conventional culture (3, 9, 17). Furthermore, 5 of these 16 patients were pretreated with antibiotics because they were transferred from other hospitals and empirical antimicrobial therapies were administered. In addition, insufficient sample volumes of blood obtained by phlebotomy in small, sick neonates may also result in decreased sensitivity of blood culture compared to that of molecular assays (15). The “gold standard” for diagnosing sepsis is still blood culture, even though, in many cases, blood cultures are negative in the face of strong clinical indicators of neonatal sepsis (15). The 16 specimens were consistent with a diagnosis of sepsis on the basis of the GSPBRT-PCR results and clinical evaluations (Table 5). Antibiotics specific for gram-positive or -negative bacteria were administered to these 16 patients.

With regard to contamination, Taq DNA polymerases are frequently reported to be contaminated by bacterial DNA (4, 8). Several approaches, including UV irradiation, 8-methoxypsoralen treatment, DNase treatment, and restriction endonuclease treatment, have been successfully used to overcome DNA contamination (12). However, most decontamination also affects the sensitivity of a broad-range PCR when a sensitive detection system is evaluated (7). In our experience, it was essential that all PCR reagents, except for Taq polymerase, were allowed to decontaminate through filter devices. mTP Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma), which ensures a high-quality, low-contaminant DNA for reliable PCR amplification, was used in GSPBRT-PCR. Furthermore, we applied both gram-positive and -negative probes in a single reaction system to quantify and discriminate bacteria, which would be more specific and less vulnerable to contamination than broad-range real-time PCR (34).

In conclusion, the use of molecular biology is essential to increase the rate of microbiological diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. We have developed a GSPBRT-PCR technique that is a rapid, highly sensitive, and specific molecular assay. This technique allows the simultaneous detection, quantification, and Gram identification of bacterial organisms directly from blood samples. Furthermore, it can also be applied to infant, adult, and other types of specimens collected from normally sterile sites. We hypothesize that GSPBRT-PCR will prove to be the most effective method of detecting bacteria in clinical practice. It not only can differentiate bacterial from viral or other pathogens, but also can classify Gram staining with a much shorter turnaround time than the gold standard culture method. GSPBRT-PCR may accelerate therapeutic decisions and enable earlier adequate antibiotic treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Health Bureau of Zhejiang Province, China (2006074A).

We thank Haipeng Cheng at The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, for his critical review and revision of the manuscript. We also thank Li Jianping for his excellent technical support. In particular, we express our great gratitude to Mao Jianhua and Zhang Highzone for outstanding effort in polishing the language of this article.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anand, A. R., H. N. Madhavan, and K. L. Therese. 2000. Use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA probe hybridization to determine the Gram reaction of the infecting bacterium in the intraocular fluids of patients with endophthalmitis. J. Infect. 41221-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous. 1995. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 11-1995. A 39-year-old man with chronic renal failure, aortic regurgitation, and a calcified mass around the aortic root. N. Engl. J. Med. 3321015-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergeron, M. G., D. Ke, C. Menard, F. J. Picard, M. Gagnon, M. Bernier, M. Ouellette, P. H. Roy, S. Marcoux, and W. D. Fraser. 2000. Rapid detection of group B streptococci in pregnant women at delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 343175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll, N. M., P. Adamson, and N. Okhravi. 1999. Elimination of bacterial DNA from Taq DNA polymerases by restriction endonuclease digestion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 373402-3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll, N. M., E. E. Jaeger, S. Choudhury, A. A. Dunlop, M. M. Matheson, P. Adamson, N. Okhravi, and S. Lightman. 2000. Detection of and discrimination between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in intraocular samples by using nested PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 381753-1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarridge, J. E., III. 2004. Impact of 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis for identification of bacteria on clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17840-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corless, C. E., M. Guiver, R. Borrow, V. Edwards-Jones, E. B. Kaczmarski, and A. J. Fox. 2000. Contamination and sensitivity issues with a real-time universal 16S rRNA PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 381747-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehricht, R., H. Hotzel, K. Sachse, and P. Slickers. 2007. Residual DNA in thermostable DNA polymerases—a cause of irritation in diagnostic PCR and microarray assays. Biologicals 35145-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espy, M. J., J. R. Uhl, L. M. Sloan, S. P. Buckwalter, M. F. Jones, E. A. Vetter, J. D. Yao, N. L. Wengenack, J. E. Rosenblatt, F. R. Cockerill III, and T. F. Smith. 2006. Real-time PCR in clinical microbiology: applications for routine laboratory testing. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19165-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenollar, F., and D. Raoult. 2007. Molecular diagnosis of bloodstream infections caused by non-cultivable bacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30(Suppl. 1)S7-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greisen, K., M. Loeffelholz, A. Purohit, and D. Leong. 1994. PCR primers and probes for the 16S rRNA gene of most species of pathogenic bacteria, including bacteria found in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32335-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heininger, A., M. Binder, A. Ellinger, K. Botzenhart, K. Unertl, and G. Doring. 2003. DNase pretreatment of master mix reagents improves the validity of universal 16S rRNA gene PCR results. J. Clin. Microbiol. 411763-1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horz, H. P., M. E. Vianna, B. P. Gomes, and G. Conrads. 2005. Evaluation of universal probes and primer sets for assessing total bacterial load in clinical samples: general implications and practical use in endodontic antimicrobial therapy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 435332-5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan, J. A., and M. B. Durso. 2005. Real-time polymerase chain reaction for detecting bacterial DNA directly from blood of neonates being evaluated for sepsis. J. Mol. Diagn. 7575-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman, D., and K. D. Fairchild. 2004. Clinical microbiology of bacterial and fungal sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17638-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ke, D., C. Menard, F. J. Picard, M. Boissinot, M. Ouellette, P. H. Roy, and M. G. Bergeron. 2000. Development of conventional and real-time PCR assays for the rapid detection of group B streptococci. Clin. Chem. 46324-331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King, A. 2001. Recommendations for susceptibility tests on fastidious organisms and those requiring special handling. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48(Suppl. 1)77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klaschik, S., L. E. Lehmann, A. Raadts, M. Book, J. Gebel, A. Hoeft, and F. Stuber. 2004. Detection and differentiation of in vitro-spiked bacteria by real-time PCR and melting-curve analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42512-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klaschik, S., L. E. Lehmann, A. Raadts, M. Book, A. Hoeft, and F. Stuber. 2002. Real-time PCR for detection and differentiation of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 404304-4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klausegger, A., M. Hell, A. Berger, K. Zinober, S. Baier, N. Jones, W. Sperl, and B. Kofler. 1999. Gram type-specific broad-range PCR amplification for rapid detection of 62 pathogenic bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37464-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krediet, T. G., E. M. Mascini, E. van Rooij, J. Vlooswijk, A. Paauw, L. J. Gerards, and A. Fleer. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of coagulase-negative staphylococci causing sepsis in a neonatal intensive care unit over an 11-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42992-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIntire, D. D., S. L. Bloom, B. M. Casey, and K. J. Leveno. 1999. Birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality among newborn infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 3401234-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammadi, T., H. W. Reesink, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and P. H. Savelkoul. 2003. Optimization of real-time PCR assay for rapid and sensitive detection of eubacterial 16S ribosomal DNA in platelet concentrates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 414796-4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadkarni, M. A., F. E. Martin, N. A. Jacques, and N. Hunter. 2002. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology 148257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikkari, S., F. A. Lopez, P. W. Lepp, P. R. Cieslak, S. Ladd-Wilson, D. Passaro, R. Danila, and D. A. Relman. 2002. Broad-range bacterial detection and the analysis of unexplained death and critical illness. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8188-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosey, A. L., E. Abachin, G. Quesnes, C. Cadilhac, Z. Pejin, C. Glorion, P. Berche, and A. Ferroni. 2007. Development of a broad-range 16S rDNA real-time PCR for the diagnosis of septic arthritis in children. J. Microbiol. Methods 6888-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saravolatz, L. D., O. Manzor, N. VanderVelde, J. Pawlak, and B. Belian. 2003. Broad-range bacterial polymerase chain reaction for early detection of bacterial meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 3640-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuurman, T., R. F. de Boer, A. M. Kooistra-Smid, and A. A. van Zwet. 2004. Prospective study of use of PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S ribosomal DNA from cerebrospinal fluid for diagnosis of bacterial meningitis in a clinical setting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42734-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang, S., G. Chen, Y. Wu, L. Du, and Z. Zhao. 2005. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial sepsis with PCR amplification and microarray hybridization in 16S rRNA gene. Pediatr. Res. 58143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shang, S., Z. Chen, and X. Yu. 2001. Detection of bacterial DNA by PCR and reverse hybridization in the 16S rRNA gene with particular reference to neonatal septicemia. Acta Paediatr. 90179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoll, B. J., N. Hansen, A. A. Fanaroff, L. L. Wright, W. A. Carlo, R. A. Ehrenkranz, J. A. Lemons, E. F. Donovan, A. R. Stark, J. E. Tyson, W. Oh, C. R. Bauer, S. B. Korones, S. Shankaran, A. R. Laptook, D. K. Stevenson, L. A. Papile, and W. K. Poole. 2002. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 110285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Haeften, R., S. Palladino, I. Kay, T. Keil, C. Heath, and G. W. Waterer. 2003. A quantitative LightCycler PCR to detect Streptococcus pneumoniae in blood and CSF. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 47407-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu, J., B. C. Millar, J. E. Moore, K. Murphy, H. Webb, A. J. Fox, M. Cafferkey, and M. J. Crowe. 2003. Employment of broad-range 16S rRNA PCR to detect aetiological agents of infection from clinical specimens in patients with acute meningitis—rapid separation of 16S rRNA PCR amplicons without the need for cloning. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zucol, F., R. A. Ammann, C. Berger, C. Aebi, M. Altwegg, F. K. Niggli, and D. Nadal. 2006. Real-time quantitative broad-range PCR assay for detection of the 16S rRNA gene followed by sequencing for species identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442750-2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]