Abstract

Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2), a clinical test for carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA, has proven to be a sensitive but only modestly specific predictor of cervical precancer and cancer risk. Some of its nonspecificity for clinical end points can be ascribed to cross-reactivity with noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes. However, the reference genotyping tests that have been used for these comparisons are also imperfect. We therefore sought to describe further the HPV genotype specificity of hc2 by comparing the hc2 results to paired results from two related PGMY09/11 L1 primer-based HPV genotyping assays: Linear Array (LA) and its prototype predecessor, the line blot assay (LBA). LA and LBA results were considered separately and combined (detection by either assay or both assays) for 37 individual HPV genotypes and HPV risk group categories (carcinogenic HPV > noncarcinogenic HPV > negative). Baseline specimens from 3,179 of 3,488 (91.5%) women referred to ALTS (a clinical trial to evaluate the management strategies for women with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASCUS] or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions) because of an ASCUS Papanicolaou smear were tested by all three assays. Among single-genotype infections with genotypes targeted by hc2 as detected by either PCR assay, HPV genotype 35 (HPV35) (86.4%), HPV56 (84.2%), and HPV58 (76.9%) were the most likely to test positive by hc2. Among single-genotype infections with genotypes not targeted by hc2 as detected by either assay, HPV82 (80.0%), HPV66 (60.0%) (recently classified as carcinogenic), HPV70 (59.1%), and HPV67 (56.3%) were the most likely to test positive by hc2. Among women who tested negative for carcinogenic HPV by both PCR tests and were positive for noncarcinogenic HPV by either test, 28% of women were hc2 positive. Conversely, 7.8% of all hc2-positive results in this population were due to cross-reactivity of hc2 with untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes. In conclusion, hc2 cross-reacts with certain untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes that are phylogenetically related to the targeted genotypes, but the degree of cross-reactivity may be less than previously reported.

Carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing in conjunction with cytology is now approved in the United States for use in cervical cancer screening (36, 48) because of the causal role of persistent carcinogenic HPV infection in the development of cervical cancer and its immediate precursor lesions. The prescribed use of HPV testing is for triage of equivocal cytology, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), to determine which patients are referred to colposcopy, and as an adjunctive screening test to cytology in women who are ≥30 years old. Recent, randomized clinical trials have highlighted the sensitivity of HPV testing for cervical precancer and cancer, which might lead to even greater use of these assays in the near future (5, 24, 26, 30).

One test, Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2; Digene Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD), has received FDA approval for use in cervical cancer screening as described above; hc2 has proven to be reliable (6, 9, 14, 45) and sensitive for detection of cervical precancer (16, 17, 31, 32, 43). However, hc2 has exhibited cross-reactivity with untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes (12, 28, 29, 33, 41, 42, 45, 49), which further reduces the already suboptimal clinical specificity and positive predictive value of HPV testing (12). Its cross-reactivity is most pronounced in women with cytologic changes who often harbor multiple, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes concurrently and/or have higher viral loads (12). The HPV genotypes most commonly found to cause hc2 cross-reactivity are HPV genotype 53 (HPV53) and HPV66, the latter of which has recently been deemed to be a carcinogenic HPV genotype (15) and therefore probably increased the clinical sensitivity of hc2. Earlier studies of hc2 (12, 28, 29, 33, 41, 42, 45, 49) were based on single tests by research and prototype HPV genotyping assays, raising the possibility that some of the cross-reactivity resulted from misclassification by the HPV genotyping assay related to: (i) single testing of small aliquots for genotyping; (ii) modest analytic sensitivity; (iii) testing errors; and (iv) “drop out” of genotypes in multigenotype HPV infections due to PCR primer competition. Thus, the ability to describe the cross-reactivity of hc2 has been limited by the imperfections of referent standards used to detect HPV genotypes present in cervical specimens.

We have previously examined the performance of hc2 in ALTS, a clinical trial to evaluate the management strategies for women with ASCUS or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) (37), including a comparison to the line blot assay (LBA; Roche Molecular Systems, Alameda, CA) (41), a HPV genotyping assay based on PGMY09/11 L1 consensus primer PCR. PGMY09/11 primers are the most recent iteration of several generations of refinements from the original MY09/11 primers and are designed to more uniformly amplify a broad range of HPV genotypes (19). We also recently completed repeat testing of the baseline specimens of women with an ASCUS Papanicolaou smear (Pap smear) enrolled in ALTS using a commercialized, research-use-only version of LBA, Linear Array (LA; Roche) (7). Although LA proved to be more analytically sensitive than LBA, we observed that LBA detected some carcinogenic HPV infections apparently missed by LA. We therefore took advantage of the repeat testing by combining LBA and LA test results as a kind of replication to maximize the sensitivity for the detection of individual HPV genotypes by PGMY L1 consensus primer PCR. We used the paired test results to reevaluate the genotype-specific analytic specificity of hc2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population.

ALTS was a randomized trial comparing three management strategies for 5,060 women with ASCUS (n = 3,488) or LSIL (n = 1,572) Pap smear (37): (i) immediate colposcopy (immediate colposcopy arm) (referral to colposcopy regardless of enrollment test results); (ii) HPV triage (HPV triage arm) (referral to colposcopy if the enrollment HPV result was positive by hc2 or missing, or if the enrollment cytology was high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [HSIL]); or (iii) conservative management (conservative management arm) (referral to colposcopy if the enrollment cytology was HSIL). At enrollment, all women received a pelvic examination with collection of two cervical specimens; the first specimen in PreservCyt for ThinPrep cytology (Cytyc Corporation, Marlborough, MA) and hc2 testing, and the second in specimen transport medium (STM; Digene Corporation). Women in the three arms of the study were reevaluated by cytology every 6 months for 2 years of follow-up and sent to colposcopy if cytology was HSIL. An exit examination with colposcopy was scheduled for all women, regardless of the study arm or prior procedures, at the completion of the follow-up. We refer readers to other references for details on randomization, examination procedures, patient management, and laboratory and pathology methods (1-3, 37, 43). The National Cancer Institute and local institutional review boards approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent. This analysis was restricted to women referred for an ASCUS Pap smear because LA testing was conducted only in this subset of women (7).

HPV DNA testing.

Residual PreservCyt specimens, after being used for liquid-based cytology, were tested by hc2 (43), a pooled-probe, signal amplification DNA test that targets a group of 13 HPV genotypes (HPV16, -18, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, -59, and -68) (39). A positive cutoff point of 1.00 relative light unit per positive control (RLU/pc) was used. Hybrid Capture 2 does not distinguish which HPV genotypes are present.

HPV genotyping by LBA, a L1 consensus primer-based PCR assay that employs a primer set designated PGMY09/11, was performed on the STM specimen as previously described (19). Amplicons were subjected to reverse-line blot hybridization for detection of 27 individual HPV genotypes (HPV6, -11, -16, -18, -26, -31, -33, -35, -39, -40, -42, -45, -51 to -59, -66, -68, and -73 [PAP238a], HPV82 [W13b], HPV83 [Pap291], and HPV84 [PAP155]) (20). We also tested for an additional 11 noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes (HPV61, -62, -64, -67, -69 to -72, -81, -82 variant [82v or IS39], and -89 [CP6108]) (27) in 76% of the enrollment specimens from women referred into the study because of an ASCUS Pap test. An equivalent of 1.5% of the original specimen was used for LBA (41).

Aliquots of the archived, enrollment STM specimens were retested using LA, which tests for 37 HPV genotypes detected by LBA, excluding HPV57, as previously described (7, 10). LA was used according to the manufacturer's instructions in the product insert, which includes DNA extraction using the QIAamp MinElute media kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). The only deviation from the LA product insert protocol was to implement an automated sample preparation for extraction of up to 96 specimens at a time on the Qiagen MDx platform (using the MinElute media MDx kit and manufacturer's instructions) rather than processing 24 specimens per batch by the manual vacuum method (10). An equivalent of 2.8% of the original specimen was used for LA.

HPV genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68 were considered the primary carcinogenic genotypes (4, 15); we included HPV66 in our definition because it was recently classified a carcinogenic HPV genotype (15). However, it is well-known that hc2 strongly detects HPV66 although it is not one of the 13 targeted genotypes (12, 33, 41). For the results of each HPV genotyping test or the combination of tests, women were also assigned to one of the following HPV risk groups defined a priori: (i) positive for carcinogenic HPV genotypes; (ii) positive for any noncarcinogenic HPV genotype and negative for all carcinogenic HPV genotypes; or (iii) PCR negative (carcinogenic HPV > noncarcinogenic HPV > PCR negative).

Pathology and treatment.

Clinical management was based on the clinical center pathologists' cytologic and histologic diagnoses. In addition, referral smears, ThinPrep slides, and histology slides were sent to the Pathology Quality Control Group (QC Pathology) based at the Johns Hopkins Hospital for review and secondary diagnoses. A portion of the ThinPrep slides from follow-up were first submitted for computer-assisted screening to reduce the manual review of completely negative slides (Neopath; TriPath Imaging, Burlington, NC). A diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2) or worse (≥CIN2) based on the clinical center pathology or a diagnosis of CIN3 or worse (≥CIN3) based on the QC Pathology review triggered treatment by the loop electrosurgical excision procedure. In addition, women with persistent low-grade lesions or ≥CIN2 at the time of the exit from the study were offered the loop electrosurgical excision procedure.

Statistical analysis.

Of the women referred into ALTS because of an ASCUS Pap smear, 3,346 (95.9%) had LBA results, 3,446 (99.1%) had LA results, 3,300 (94.6%) had hc2 results, and 3,179 (91.5%) had results for all three assays on the enrollment specimens, which defined our analytic group.

We first calculated the percentage of hc2 test positives for samples with a single HPV genotype infection for each HPV genotype as detected by LBA, LA, both assays, or either assay. We next calculated the percentage of hc2 test positives related to the number (one, two, three, or four or more) of HPV genotypes as detected by either PCR assay for the following subgroups of women: (i) women with only carcinogenic HPV genotypes; (ii) women with only noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes; and (iii) women with only noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes excluding HPV53, -67, -70, -73, -82, and -82v, which appear to be the untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes with which hc2 showed the most cross-reactivity.

We also calculated the percentage of hc2-positive results for infections by each carcinogenic HPV genotype singly and as a double infection for that carcinogenic HPV genotype plus any other HPV genotype, any other carcinogenic HPV genotype, and any noncarcinogenic HPV genotype. For double infections, we calculated a ratio of observed versus expected percentages of hc2-positive results by comparing the observed percentage of hc2-positive results to the expected percentage, assuming that each HPV genotype contributed additively to positive results with the hc2 test. We used the formula p1 + (1 − p1)(p2) = p1 + p 2 − p1p2, where p1 is the probability of a positive result by the hc2 test due to the detection of the specified carcinogenic HPV genotype and p2 is the probability of a positive result by the hc2 test for any other, any other carcinogenic, or any noncarcinogenic HPV genotype in aggregate.

Multivariate logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals as measures of association for each HPV genotype detected with testing hc2 positive. A separate model for testing hc2-positive results was developed for the detection of each individual HPV genotype as detected by either HPV genotyping assay. Each HPV genotype-specific model included the detection of any other HPV genotype in aggregate, with an interaction term to account for the impact of the presence of the other HPV genotype(s) on the analytic sensitivity for the HPV genotype of interest. We used this crude approach to account for the other HPV genotypes because there were insufficient numbers of infections to statistically adjust pair-wise for all combinations of HPV genotypes. The models also controlled for other covariates, such as the QC Pathology reinterpretation of the enrollment cytology slide (negative versus ASCUS or worse [≥ASCUS]), number of HPV genotypes detected (zero, one, and two or more), and the worst 2-year QC Pathology histologic diagnosis (<CIN2, CIN2, or ≥CIN3).

Cross-tabulations of paired LBA and LA results, categorized according to risk groups defined by each, were used to examine the impact of cross-reactivity on hc2 accuracy in detection of ≥CIN3. These paired results were related to the 2-year absolute risk of ≥CIN3 as diagnosed by the QC Pathology stratified by hc2 results, and the association of hc2 testing positive (versus negative) with 2-year cases of ≥CIN3 was also represented as an OR.

We also evaluated the likelihood of hc2 cross-reactivity with untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes for hc2-positive results with a signal strength between 1.00 and 1.99 RLU/pc versus ≥2.00 RLU/pc, because recent reports (32) have suggested that using a 2.00-RLU/pc cutoff point might increase the accuracy of hc2. HPV risk group for this analysis was defined by the greatest HPV risk group detected by LBA or LA (HPV status). The 2-year absolute risk of ≥CIN3 were determined for paired results of HPV risk group and hc2 category (hc2 negative or hc2 positive with a signal strength of 1.00 to 1.99 RLU/pc, and hc2 positive with a signal strength of ≥2.00 RLU/pc). The sensitivity and specificity for detection of 2-year cumulative ≥CIN3 were calculated for the 1.00-RLU/pc and 2.00-RLU/pc cutoff points.

STATA version 8.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Relationships of HPV genotype detection and testing hc2 positive.

We first compared the results of LBA, LA, and the two tests combined (detection by either assay or by both assays) to the percentages of hc2-positive results for the 3,179 women for which we had results for all three HPV tests (Table 1). With decreasingly sensitive detection of HPV genotypes (either LBA or LA positive > LA > LBA > both LBA and LA positive for a particular HPV genotype), we observed that (i) more women tested completely negative for all HPV genotypes (862 versus 957 versus 1,224 versus 1,390, respectively), (ii) more women who did test negative for all HPV genotypes tested positive by hc2 (4.8% versus 8.1% versus 10.8% versus 13.5%, respectively), (iii) more women with single HPV genotype infections by untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes (i.e., excluding HPV66) tested positive by hc2 (20.2% versus 22.5% versus 29.1% versus 29.5%, respectively), and (iv) more women with single HPV genotype infections by carcinogenic HPV genotypes (including HPV66) tested positive by hc2 (68.9% versus 71.0% versus 83.2% versus 86.5%, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Reactivity of Hybrid Capture 2 to single HPV genotype infections detected by the line blot assay, Linear Array, and the two tests combined

| Result or HPV genotypea | Tested positive by the following method(s):

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBA or LAb

|

LA

|

LBA

|

LBA and LAc

|

|||||

| No. of women | % Positive by hc2 | No. of women | % Positive by hc2 | No. of women | % Positive by hc2 | No. of women | % Positive by hc2 | |

| Results | ||||||||

| No HPV type detected | 862 | 4.8 | 957 | 8.1 | 1,224 | 10.8 | 1,390 | 13.5 |

| Any single HPV type detected | 747 | 49.5 | 789 | 51.3 | 843 | 65.4 | 458 | 71.4 |

| Any single noncarcinogenic HPV genotype detected | 297 | 20.2 | 320 | 22.5 | 278 | 29.1 | 139 | 29.5 |

| Any single carcinogenic HPV genotype detected | 450 | 68.9 | 469 | 71.0 | 565 | 83.2 | 319 | 86.5 |

| Single HPV genotypes | ||||||||

| HPV6 | 10 | 0.0 | 11 | 9.1 | 6 | 16.7 | 3 | 0.0 |

| HPV11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | |||

| HPV16 | 96 | 72.9 | 105 | 75.2 | 124 | 88.7 | 72 | 88.9 |

| HPV18 | 33 | 60.6 | 35 | 62.9 | 39 | 76.9 | 24 | 75.0 |

| HPV26 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 | 0 | |

| HPV31 | 51 | 68.6 | 53 | 73.6 | 52 | 90.4 | 34 | 94.1 |

| HPV33 | 14 | 71.4 | 16 | 87.5 | 28 | 78.6 | 11 | 81.8 |

| HPV35 | 22 | 86.4 | 27 | 96.3 | 31 | 80.6 | 18 | 94.4 |

| HPV39 | 15 | 73.3 | 17 | 64.7 | 25 | 88.0 | 11 | 90.9 |

| HPV40 | 8 | 25.0 | 8 | 25.0 | 7 | 14.3 | 4 | 25.0 |

| HPV42 | 19 | 21.1 | 17 | 41.2 | 23 | 26.1 | 9 | 33.3 |

| HPV45 | 22 | 72.7 | 21 | 71.4 | 29 | 72.4 | 16 | 87.5 |

| HPV51 | 33 | 54.6 | 33 | 54.6 | 36 | 91.7 | 18 | 88.9 |

| HPV52 | 53 | 67.9 | 41 | 65.9 | 76 | 75.0 | 33 | 78.8 |

| HPV53 | 26 | 38.5 | 26 | 38.5 | 30 | 60.0 | 17 | 58.8 |

| HPV54 | 27 | 3.7 | 31 | 3.2 | 23 | 13.0 | 15 | 0.0 |

| HPV55 | 14 | 7.1 | 16 | 6.3 | 12 | 25.0 | 8 | 12.5 |

| HPV56 | 19 | 84.2 | 19 | 84.2 | 26 | 84.6 | 18 | 83.3 |

| HPV58 | 26 | 76.9 | 28 | 78.6 | 34 | 88.2 | 21 | 95.2 |

| HPV59 | 25 | 68.0 | 29 | 72.4 | 27 | 77.8 | 17 | 88.2 |

| HPV61d | 30 | 3.3 | 33 | 9.1 | 27 | 11.1 | 13 | 7.7 |

| HPV62d | 32 | 9.4 | 35 | 8.6 | 19 | 10.5 | 12 | 16.7 |

| HPV64d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| HPV66 | 25 | 60.0 | 28 | 57.1 | 25 | 84.0 | 18 | 83.3 |

| HPV67d | 16 | 56.3 | 15 | 60.0 | 15 | 53.3 | 7 | 42.9 |

| HPV68 | 16 | 43.8 | 17 | 41.2 | 13 | 69.2 | 8 | 62.5 |

| HPV69d | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | |||

| HPV70d | 22 | 59.1 | 24 | 58.3 | 21 | 57.1 | 15 | 60.0 |

| HPV71d | 4 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 | 3 | 33.3 | 1 | 0.0 |

| HPV72d | 4 | 0.0 | 6 | 16.7 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 | |

| HPV73 | 5 | 40.0 | 5 | 40.0 | 10 | 40.0 | 3 | 66.7 |

| HPV81d | 10 | 20.0 | 10 | 20.0 | 5 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 |

| HPV82 | 5 | 80.0 | 8 | 75.0 | 12 | 75.0 | 5 | 80.0 |

| HPV82vd | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 2 | 50.0 | 2 | 50.0 |

| HPV83 | 18 | 5.6 | 20 | 10.0 | 18 | 11.1 | 8 | 12.5 |

| HPV84 | 16 | 12.5 | 17 | 11.8 | 19 | 10.5 | 5 | 20.0 |

| HPV89d | 26 | 11.5 | 29 | 13.8 | 19 | 15.8 | 8 | 25.0 |

Genotypes in bold type are genotypes targeted by hc2. HPV66 (italicized) is not targeted by hc2, but its detection by hc2 has been previously well-documented (12, 28, 29, 33, 41, 42, 45, 49), and it is now considered a carcinogenic HPV genotype (15); therefore, its detection is considered of benefit.

Tested positive for that HPV genotype(s) by either HPV genotyping assay.

Tested positive for the HPV genotype(s) by both HPV genotyping assays (i.e., the specimen was considered positive for a HPV genotype only if both assays detected it.).

In a subset of the women, these HPV genotypes were not included in the LBA and therefore were not detected.

The single carcinogenic HPV genotype infections as detected by either assay that were most likely also to test hc2 positive were (in order) HPV35 (86.4%), HPV56 (84.2%), HPV58 (76.9%), HPV39 (73.3%), and HPV16 (72.9%). Sixty percent of the single-genotype infections by untargeted, carcinogenic HPV66 as detected by LA and/or LBA tested positive by hc2. The single HPV genotype infections by untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes as detected by LA and/or LBA that were most likely to also test hc2 positive were (in order) HPV82 (80.0%), HPV70 (59.1%), HPV67 (56.3%), HPV82v (50%), HPV73 (50%), and HPV53 (38.5%).

When HPV genotypes were confirmed by both assays, i.e., the least sensitive and most specific definition of testing positive for a HPV genotype, there was a greater tendency to test positive by hc2. This was presumably because these “confirmed” HPV infections represented a subset of HPV infections with higher viral load compared to those infections detected by only one assay. For most carcinogenic HPV genotypes, single-genotype infections detected by LA and LBA were generally 80% or greater hc2 positive, although HPV18 infections detected by LA and LBA only tested 75% hc2 positive and HPV68 infections only tested 62.5% hc2 positive.

Impact of the number of HPV genotypes detected on a positive test result by hc2.

We found an increasing likelihood of a positive test result by hc2 with an increasing number of HPV genotypes detected (defined as those detected by either HPV genotyping assay) regardless of the group of HPV genotypes evaluated (Table 2). The percentage of hc2-positive results was 70 for singly detected carcinogenic HPV genotype and reached a plateau of approximately 90 for two, three, or four or more detected genotypes (the test of trend for the number of HPV genotypes detected and testing hc2 was highly significant [Ptrend] < 0.0005). The percentage of hc2-positive results increased from 21 for a singly detected noncarcinogenic HPV genotype to 61 for four or more detected genotypes (Ptrend < 0.0005). By excluding a priori the untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes with which hc2 was most likely to cross-react, the percentage of hc2-positive results increased from 10 for singly detected noncarcinogenic HPV genotype to 75 for four or more detected genotypes (Ptrend < 0.0005).

TABLE 2.

Relationship of a positive test result by hc2 with the number of HPV genotypes as detected by LA and/or LBA for three different groups of womena

| No. of genotypes | Women with carcinogenic HPV

|

Women with noncarcinogenic HPV

|

Women with noncarcinogenic HPV (excluding HPV53, -67, -70, 7-3, -82, and -82v)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. negative by hc2 (% of total) | No. positive by hc2 (% of total) | Total no. | No. negative by hc2 (% of total) | No. positive by hc2 (% of total) | Total no. | No. negative by hc2 (% of total) | No. positive by hc2 (% of total) | Total no. | |

| 1 | 141 (30) | 324 (70) | 465 | 240 (79) | 64 (21) | 304 | 202 (90) | 22 (10) | 224 |

| 2 | 21 (10) | 180 (90) | 201 | 71 (65) | 39 (35) | 110 | 51 (84) | 10 (16) | 61 |

| 3 | 5 (7) | 64 (93) | 69 | 19 (46) | 22 (54) | 41 | 9 (56) | 7 (44) | 16 |

| 4+ | 2 (7) | 27 (93) | 29 | 7 (39) | 11 (61) | 18 | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 4 |

| Total | 169 | 595 | 764 | 337 | 136 | 473 | 263 | 42 | 305 |

Relationship of testing positive by hc2 with the number of HPV genotypes as detected by either LBA or LA for three different groups of women: (i) women with only carcinogenic HPV genotypes, (ii) women with only noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes, and (iii) women with only noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes excluding HPV53, -67, -70, -73, -82, and -82v, which appeared to be the untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes with which hc2 was most cross-reactive. The test of trend for the number of HPV genotypes detected and testing hc2 was highly significant (Ptrend < 0.0005) for groups for HPV genotypes.

Double infections by any combination of a carcinogenic HPV genotype with any other HPV genotype, any other carcinogenic HPV genotype, and any noncarcinogenic HPV genotype generally increased the likelihood of a positive result by the hc2 test (Table 3). This increase in hc2-positive test results for double infections versus single infections appeared to be additive, as the ratio of the observed and expected percentage [i.e., p1 + (1 − p1)(p2) = p1 + p2 − p1p2] of hc2-positive test results was very often near 1.

TABLE 3.

Likelihood of testing positive by hc2 for each carcinogenic HPV genotype detected by either or both HPV genotyping assays singly and as dual infection with any other HPV genotype, with any other carcinogenic HPV genotype, and any noncarcinogenic HPVa

| HPV genotype | Single-genotype infection %hc2+ | Dual infection (any other genotype)

|

Dual infection (any other carcinogenic genotype)

|

Dual infection (any noncarcinogenic genotype)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed %hc2+ | Expected %hc2+ | O/E | Observed %hc2+ | Expected %hc2+ | O/E | Observed %hc2+ | Expected %hc2+ | O/E | ||

| HPV16 | 72.9 | 87.9 | 85.4 | 1.03 | 91.7 | 91.3 | 1.00 | 84.1 | 78.4 | 1.07 |

| HPV18 | 60.6 | 76.6 | 79.9 | 0.96 | 75.0 | 88.0 | 0.85 | 80.0 | 68.6 | 1.17 |

| HPV31 | 68.6 | 83.9 | 83.7 | 1.00 | 89.3 | 90.3 | 0.99 | 78.6 | 75.0 | 1.05 |

| HPV33 | 71.4 | 83.3 | 85.5 | 0.98 | 84.6 | 91.1 | 0.93 | 81.8 | 77.2 | 1.06 |

| HPV35 | 86.4 | 84.6 | 93.0 | 0.91 | 93.3 | 95.6 | 0.98 | 72.7 | 89.1 | 0.82 |

| HPV39 | 73.3 | 84.4 | 86.4 | 0.98 | 92.0 | 91.7 | 1.00 | 75.0 | 78.7 | 0.95 |

| HPV45 | 72.7 | 72.2 | 86.0 | 0.84 | 85.0 | 91.5 | 0.93 | 56.3 | 78.2 | 0.72 |

| HPV51 | 54.6 | 84.6 | 77.0 | 1.10 | 80.0 | 86.4 | 0.93 | 90.9 | 63.7 | 1.43 |

| HPV52 | 67.9 | 83.6 | 83.4 | 1.00 | 95.4 | 90.1 | 1.06 | 66.7 | 74.4 | 0.90 |

| HPV56 | 84.2 | 91.4 | 91.9 | 1.00 | 100.0 | 95.0 | 1.05 | 75.0 | 87.4 | 0.86 |

| HPV58 | 76.9 | 85.3 | 88.1 | 0.97 | 85.0 | 92.7 | 0.92 | 85.7 | 81.6 | 1.05 |

| HPV59 | 68.0 | 79.1 | 83.6 | 0.95 | 89.3 | 90.1 | 0.99 | 60.0 | 74.5 | 0.81 |

| HPV66 | 60.0 | 76.9 | 79.7 | 0.97 | 91.3 | 87.6 | 1.04 | 56.3 | 68.1 | 0.83 |

| HPV68 | 43.8 | 78.3 | 71.7 | 1.09 | 92.3 | 82.8 | 1.12 | 55.6 | 55.1 | 1.01 |

Likelihood of testing positive by hc2 (%hc2+). The expected percent hc2+ was calculated by assuming that the HPV genotypes other than the one of interested contributed independently and additively to a hc-positive test result [i.e., p1 + (1 − p1)(p2) = p1 + p2 − p1p2]. A ratio of observed versus expected (O/E) was then calculated.

Modeling the HPV genotype specificity of hc2.

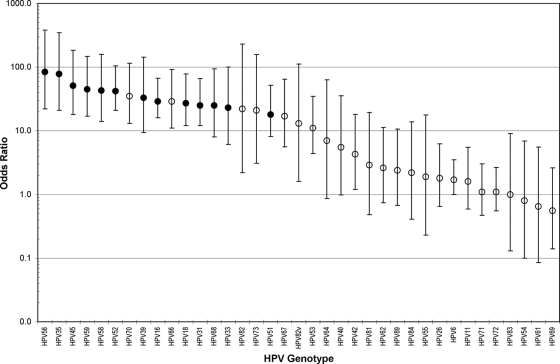

We constructed individual models for the association of each HPV genotype with hc2 testing positive, controlling for the detection of other HPV genotypes (Fig. 1). All targeted HPV genotypes were strongly associated with testing hc2 positive, with HPV56 (OR = 84) and HPV35 (OR = 78) being the strongest and HPV51 (OR = 18) being the weakest. Untargeted HPV70, HPV66, HPV82, HPV73, HPV82v, HPV67, and HPV53 were strongly and independently (OR > 10) associated with testing hc2 positive.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the odds ratio (circles) and 95% confidence intervals (bars) for the association of each HPV genotype with a positive Hybrid Capture 2 test result. A model was separately constructed for the detection of each HPV genotype by Linear Array and/or the line blot assay and adjusted for codetection of any of the other HPV genotypes. Targeted HPV genotypes (•) and untargeted HPV LA and/or LBA genotypes (○) are indicated.

Relationship of hc2 test results, HPV risk group, and risk of ≥CIN3.

We also examined the relationship of hc2 test results, classification of HPV risk status for detection of HPV genotypes by LA and/or LBA, and the 2-year risk of ≥CIN3. As shown in Table 4, most hc2-positive women tested positive for carcinogenic HPV as detected by either HPV genotyping assay (89.8%), and these women had a 16.5% 2-year risk of ≥CIN3. Only 7.8% of hc2-positive women were positive only for noncarcinogenic HPV, and only 2.4% of hc2-positive women tested negative for HPV genotypes by LBA and LA. Of note, the 2-year risk for ≥CIN3 among those hc2-positive women who tested positive for noncarcinogenic HPV was similar to those hc2-positive women who tested negative for any HPV genotype (2.3% versus 2.4%, respectively). Among the hc2-negative women, 23.2% of women tested positive for carcinogenic HPV by LA and/or LBA, but their 2-year risk for ≥CIN3 was only 2.6%. The 2-year risk for ≥CIN3 among those women who tested negative by all HPV assays was 0.7%. A more detailed comparison of HPV test results and the 2-year risk of ≥CIN3 is presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of hc2 test results to HPV risk group categorization based on HPV genotype detection by LA and/or LBA and the corresponding 2-year cumulative risk of CIN3 or cancer as diagnosed by QC Pathologya

| hc2 test result | HPV status | No. of women with HPV status | % of total women | No. of women with ≥CIN3 | Risk of ≥CIN3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Carcinogenic | 1,854 | 58.3 | 257 | 13.9 |

| Noncarcinogenic | 463 | 14.6 | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Negative | 862 | 27.1 | 7 | 0.8 | |

| Positive | Carcinogenic | 1,505 | 89.8 | 248 | 16.5 |

| Noncarcinogenic | 130 | 7.8 | 3 | 2.3 | |

| Negative | 41 | 2.4 | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Negative | Carcinogenic | 349 | 23.2 | 9b | 2.6 |

| Noncarcinogenic | 333 | 22.2 | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Negative | 821 | 54.6 | 6 | 0.7 |

Comparison of hc2 test results to HPV risk group categorization (HPV status) as determined by LA and LBA and the corresponding 2-year cumulative risk of CIN3 or cancer (≥CIN3) as diagnosed by QC Pathology.

The HPV genotypes detected in these nine ≥CIN3 cases that tested hc2 negative: HPV45, HPV51, HPV45, HPV39 and HPV51, HPV58, HPV68, HPV18 and HPV33, HPV16 and HPV45, and HPV16.

Hybrid Capture 2 signal strength and cross-reactivity with noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes.

Finally, we compared the degree of cross-reactivity with untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes among those hc2-positive specimens with signal strengths of 1.00 to 1.99 RLU/pc versus ≥2.00 RLU/pc. As shown in Table 5, hc2-positive specimens with signal strengths of 1.00 to 1.99 RLU/pc were characterized by a greater percentage that tested positive only for noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes (21.3%) than higher-signal-strength hc2-positive specimens (6.6%) (P < 0.001). In fact, the hc2-positive specimens with weak signal strengths were as likely as the hc2-negative specimens to test positive only for noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes as detected by LA and/or LBA (21.3% versus 22.2%; P = 0.5). The women with low-signal-strength hc2-positive specimens were at a low 2-year risk of ≥CIN3 regardless of their HPV risk group; women with low-signal-strength hc2-positive specimens that tested positive for carcinogenic HPV by either genotyping test had a significantly lower risk of 2-year risk of ≥CIN3 than the hc2-positive women with specimens with higher signal strengths (6.4% versus 17.2%, respectively; P < 0.001). Consequently, a 2.00-RLU/pc versus a 1.00-RLU/pc cutoff point for hc2 in this subpopulation within ALTS lowered the sensitivity (90.4% versus 92.6%) and increased the specificity (55.5% versus 51.0%) for 2-year cumulative ≥CIN3.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of hc2-negative and hc2-positive test results for specimens with different signal strengths to the HPV status, as defined by the high-risk group based on HPV genotype detection by LA and/or LBA, and 2-year cumulative diagnosis of ≥CIN3 as diagnosed by QC Pathology

| HPV status | hc2 negative

|

hc2 positive

|

Total no. of women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1.99 RLU/pc

|

≥2 RLU/pc

|

|||||||||

| No. of women (%) | No. of women with ≥CIN3 | %≥CIN3 | No. of women (%) | No. of women with ≥CIN3 | %≥CIN3 | No. of women (%) | No. of women with ≥CIN3 | %≥CIN3 | ||

| Negative | 821 (54.6) | 6 | 0.7 | 13 (9.6) | 0 | 0.0 | 28 (1.8) | 1 | 3.6 | 862 |

| Noncarcinogenic | 333 (22.2) | 5 | 1.5 | 29 (21.3) | 0 | 0.0 | 101 (6.6) | 3 | 3.0 | 463 |

| Carcinogenic | 349 (23.2) | 9 | 2.6 | 94 (69.1) | 6 | 6.4 | 1,411 (91.6) | 242 | 17.2 | 1,854 |

| Total | 1,503 (100) | 20 | 1.3 | 136 (100) | 6 | 4.4 | 1,540 (100) | 246 | 16.0 | 3,179 |

DISCUSSION

The aim of the analysis was to further describe the HPV genotype specificity of hc2, a FDA-approved test for detection of carcinogenic HPV DNA. In the United States, carcinogenic HPV DNA testing has been approved as a triage test for women with ASCUS cytology to determine who needs additional clinical management, i.e., colposcopic evaluation, and as an adjunctive screening test with cytology for women who are ≥30 years old (48). Other uses, such as postcolposcopy and posttreatment follow-up, have been recently accepted by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (46, 47). A recently conducted clinical trial comparing hc2 to cytology found again that hc2 was much more sensitive but slightly less specific than cytology (24). We were interested in evaluating the specificity of hc2 for PGMY-detected HPV genotypes to better understand its performance.

The studies of hc2 cross-reactivity have been relatively small or based on a single HPV genotyping result. We took advantage of repeat testing of the baseline ASCUS referral specimens with LA (7) to improve the accuracy of HPV genotyping. We acknowledge that the two assays, LBA and LA, are not independent, because both tests rely on PGMY09/11 primers but double testing reduced simple testing error that is inherent to all tests. We were therefore better able to truly attribute hc2-positive results to untargeted HPV genotypes whose detection has no clinical utility (i.e., noncarcinogenic HPV) versus misclassified HPV status (i.e., missed detection of carcinogenic HPV) by the referent test. Although LBA was less sensitive than LA (primarily due to the difference in the amount of specimen used) (7), it did detect some carcinogenic HPV missed by LA and thereby helped to overcome testing errors inherent to any test. Importantly, these added pick-ups by LBA appeared to be true positives, as they tended to correlate with the risk of precancer. Ideally, we would have tested with another PCR primer system or sequencing to account for errors in PGMY itself, but such data were not available. Using the two PGMY tests did create a rigorous referent standard for PGMY-detected HPV genotypes and did further clarify the patterns of true- and false-positive hc2 results that are consistent with other studies.

hc2 testing positive was strongly related to which and the number of HPV genotypes present, and the effects of having additional HPV genotypes present appeared to be additive. The distinction between targeted and untargeted HPV genotypes was not absolute, i.e., as previously reported, hc2 can cross-react with untargeted HPV genotypes. As shown in Fig. 1, there was a gradation in the strength of association of testing hc2 positive by HPV genotype, with the targeted HPV genotypes generally the most strongly associated. Untargeted HPV genotypes in the context of multigenotype infections can lead to a high percentage of hc2 test-positive results, decreasing the specificity. This emphasizes the importance of limited and judicious use of hc2 in younger women who are more likely to have multigenotype infections with very little cancer risk.

Some cross-reactivity has proven to be beneficial to the extent that hc2 detects HPV66, a HPV genotype recently classified as a carcinogenic HPV genotype (15), but on the whole, cross-reactivity reduces the specificity of the test (12). This is increasingly true, as the target of disease detection is raised from CIN2, an equivocal cervical precancer diagnosis (13), to CIN3, our more rigorous definition of cervical precancer and a better surrogate for cancer risk, to cancer.

Aside from the aforementioned HPV66, the untargeted HPV genotypes most likely to be associated with a positive hc2 test in this study were HPV82, HPV70, HPV67, HPV82v, and HPV53. All are genetically related to targeted (i.e., carcinogenic) HPV genotypes (18). HPV67 is found within α9 phylogenetic species that includes carcinogenic HPV16, HPV31, HPV33, HPV35, HPV52, and HPV58; HPV73 is found within the α11 phylogenetic species, which is closely related to α9. HPV70 is found within the α7 phylogenetic species that includes carcinogenic HPV18, HPV39, HPV45, and HPV68. HPV82 and HPV82v are found within the α5 phylogenetic species that includes carcinogenic HPV51, and HPV53 (and HPV66) are found within the α6 phylogenetic species that includes carcinogenic HPV56. It is noteworthy that HPV82 (and HPV82v) and HPV73 have been reported to be possible carcinogenic HPV genotypes (25). HPV67 has also been reported in cancers (23, 35). However, the benefit of detecting these additional genotypes by hc2 (or any other HPV test) may do more harm than good by reducing its clinical specificity (40).

Looking across studies (12, 28, 29, 33, 41, 42, 45, 49) (Table 6), infections by HPV6, HPV11, HPV53, HPV66, HPV67, HPV70, and HPV82/82v are consistently the most likely of the untargeted HPV genotypes to cause hc2-positive test results; the associations of other, untargeted HPV genotypes with hc2-positive test results appear sporadic and might easily be explained by misclassification/failed detection of a targeted HPV genotype present in a cervical specimen by the referent PCR assay. Importantly, hc2 does not appear to react as strongly with genotypes that predominantly cause genital warts, i.e., with benign genotypes that have a predilection for vaginal tissue (e.g., HPV61 and HPV71) (8, 11) and are unrelated to cancer risk.

TABLE 6.

Comparison across studies of untargeted HPV genotypes which are reportedly associated with hc2 testing positive (cross-reactivity)

| Reference | No. of specimens (hc2+)a | Cross-reactivityb with the following HPV genotype:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 11 | 26 | 34 | 40 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 61 | 62 | 64 | 66 | 67 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 81 | 82 | 82v | 83 | 84 | 89 | ||

| Peyton et al. (28)c | 27 | † | † | - | - | CR | † | - | † | - | CR | CR | † | CR | - | CR | - | - | - | † | CR | |||||||

| Terry et al. (45)d | 258 | CR | CR | CR | - | CR | CR | - | - | CR | - | CR | - | - | - | CR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | CR | CR | - |

| Schneede et al. (42) | 29 | CR | CR | CR | CR | - | - | CR | - | - | - | - | ||||||||||||||||

| Yamazaki et al. (49)e | 212 | CR | CR | - | CR | CR | CR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||||||||

| Castle et al. (12)f | 39 | † | CR | † | - | † | CR | † | † | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | † | † | - | CR | - | † | † | |||||||

| Poljak et al. (29)g | 325 | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | CR | ||||||||||

| Schiffman et al. (41)h | 8,783 | - | - | - | CR | CR | CR | CR | - | CR | CR | |||||||||||||||||

| Safaeian et al. (33)i | 1,962 | CR | CR | - | † | CR | † | CR | CR | CR | CR | - | - | - | - | CR | - | CR | - | - | - | CR | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Castle et al. (7) | 1,676 | ? | † | † | - | ? | ? | - | - | CR | † | † | † | † | ? | CR | CR | CR | † | † | CR | - | † | CR | CR | † | † | † |

Number of specimens that gave a positive test result by hc2.

An empty box or cell indicates that the HPV genotype was not detected or not detected singly in that study. Therefore, hc2 could not be assessed for cross-reactivity to that HPV genotype in the study. -, HPV genotype was not targeted by the PCR assay used as the referent test; †, no cross-reactivity detected; CR, cross-reactivity was reported for that HPV genotype; ?, genotypes that were either marginally associated (0.05 ≤ P ≤ 0.1) or had OR of 2 or greater.

Did not test separately for HPV6 and HPV11, HPV26 and HPV84, or HPV40 and HPV42.

Ranked detection of HPV genotypes hierarchically.

Did not provide data on individual HPV genotypes detected.

Detected HPV genotypes 2, 13, 34, 42 to 44, 57, 62, 64, 69, 74, 82, and AE9 as a pool; some cross-reactivity for this probe set was observed.

Did not evaluate PCR results among hc2-negative women.

Listed only those single HPV genotype infections in which >50% were hc2 positive.

HPV73 could not be distinguished from HPV68, a targeted hc2 genotype.

Even with improved classification, cross-reactivity of hc2 with untargeted, noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes still contributed significantly to its analytical and clinical nonspecificity. This cross-reactivity resulted in approximately 8% false-positive hc2 results in a population of women that was ∼50% hc2 positive (versus a screening population in which 5 to 10% of the population will be hc2 positive), with the five most “cross-reactive” genotypes accounting for 5% of all hc2-positive results. A not inconsequential fraction (82 of 381 [21.5%] [see Table S1 in the supplemental material]) of previously observed cross-reactivity by hc2 (41) was due the failure of LBA to detect carcinogenic HPV infections with lower viral loads, which are subsequently detected by LA in the context of coinfecting noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes. The women with hc2-positive results reclassified by LA as carcinogenic HPV positive tended to be at an elevated risk of ≥CIN3 compared to those confirmed as noncarcinogenic (4.3% versus 2.4%), although this difference was not significant due to small numbers. These hc2-positive results (LA positive for carcinogenic HPV, LBA negative for carcinogenic HPV but positive for noncarcinogenic HPV) appeared to be true-positive results, because the results were more strongly linked to ≥CIN3 risk than hc2-positive results in which no carcinogenic HPV genotype was detected.

Importantly, the estimated contribution of cross-reactivity of hc2 with noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes to its overall positivity depends significantly on the analytic sensitivity of the reference test(s), as we have shown here. Poor analytic sensitivity of the referent test can exaggerate the relative importance of hc2's cross-reactivity. For example, a recent study (34) comparing LBA to hc2 found that 31.5% of hc2-positive results were LBA negative for carcinogenic HPV genotypes and 11.0% of the hc2-positive results were LBA positive for noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes versus 16.3% and 7.9%, respectively, for LBA and 7.8% and 2.4%, respectively, as detected by either LBA or LA in ALTS.

There was a strong correlation between qualitative indicators of HPV viral load and hc2 testing positive for both targeted and untargeted HPV genotypes. Single carcinogenic HPV infections detected by either assay but not both (“unconfirmed”) were much less likely than confirmed single carcinogenic HPV infections to give a positive result by hc2 (26.0% versus 86.5%, respectively; P < 0.0005). Nonnormal cytology, such as ASCUS and LSIL, is typified by higher viral load and remained strongly associated with hc2 positivity even after controlling for all HPV genotypes and the underlying histopathologic disease. A positive test result by hc2 was associated with band strength for single-genotype infections of untargeted (Ptrend = 0.003) and targeted (Ptrend < 0.001) HPV genotypes detected by LA (data not shown), which confirms this relationship.

Detection of HPV genotypes that were confirmed by both PCR tests is intrinsically less sensitive but more specific than either test alone. Perhaps not surprisingly, hc2 was more likely to test positive among the PCR-negative results when both tests were required to be positive for a HPV genotype to be called positive for that HPV genotype than detection of HPV genotypes by either test alone or by either test in combination (i.e., LBA or LA). There were more false-negative results by PCR using this more stringent definition of detection, and hc2 detected these errors. This demonstrates the obvious trade-offs of analytic sensitivity with specificity and emphasizes that no HPV test is perfect: changes in analytic sensitivity also alter the likelihood of false-positive and false-negative results. However, the decision regarding the optimal cutoff points for analytic sensitivity must be made in reference to clinical end points of cervical precancer and cancer, balancing clinical sensitivity and specificity (44).

We also examined how the choice of hc2 cutoff point influenced the chances of cross-reactivity and the impact of clinical performance. A 2.00-RLU/pc cutoff point reduced the cross-reactivity with noncarcinogenic HPV types and the detection of some carcinogenic HPV infections that were less risky for ≥CIN3. As a result, the higher cutoff point increases specificity (and positive predictive value) at the cost of lower sensitivity (and negative predictive value) for ≥CIN3 compared to the 1.00-RLU/pc cutoff point. This suggests that there exists a “gray zone” but without perfect boundaries. A positive cutoff point of ≥2.00 RLU/pc results in a qualitatively more accurate hc2 test but sacrifices some of the reassurance of the negative test.

We mention an important limitation of this analysis: hc2 testing and HPV genotyping testing were done on different specimens, PreservCyt and STM, respectively, collected at the same visit. It is unclear how conducting these tests on different specimens influenced our test results and analyses. However, all three tests were highly correlated, which suggests that testing conducted on different specimens did not profoundly influence our observations.

In conclusion, we showed that hc2 has variable analytic sensitivity for carcinogenic HPV genotypes. Large clinical studies of hc2 might explore the HPV genotypes found in CIN3 and cancers falsely testing negative by hc2 to determine whether these HPV genotypes are the same genotypes shown to be the most poorly detected by hc2 in this analysis. We also confirmed that hc2 cross-reacted with certain untargeted genotypes that are phylogenetically related to the targeted genotypes, but this cross-reactivity added little or no value to its clinical performance for detection of cervical precancer and cancer. Some cross-reactivity with noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes previously attributed to hc2 was in fact the result of misclassification by the reference measurement. Using the most sensitive method of HPV genotype detection in this analysis (positive by either PCR test), we found that in this population approximately 8% of hc2-positive results were attributable to cross-reactivity in the population, which was referred to the study because of cytologic indications of cervical abnormalities. We would expect that the degree of hc2 cross-reactivity would be less in the general population because of fewer cytologic abnormalities, which are characterized by higher HPV viral loads and more multi-HPV genotype infections (12).

The accuracy of next generation versions of hc2 may benefit from reduced cross-reactivity with untargeted, noncarcinogenic genotypes, perhaps by applying more-specific probes, more-stringent hybridization conditions, and/or complementary, unlabeled probes against HPV genotypes like HPV53 to block hybridization and detection of these genotypes. HPV53 in particular can be highly prevalent (21), and therefore, a significantly greater number of women will be incorrectly labeled by hc2 as carcinogenic HPV positive and at risk (40). Increased accuracy will improve the confidence (regarding risk) in the meaning of a positive hc2 test result. The goal of HPV testing is to identify those at risk of ≥CIN3 (38), not detection of HPV itself and especially not the detection of noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes. The latter is particularly important, since some noncarcinogenic HPV genotypes, like HPV53, can cause CIN2 but have little or no possibility of causing cancer (40, 44). However, these cases of CIN2 might be treated by excisional procedures, which can cause iatrogenic morbidity and adversely affect reproductive outcomes (22).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

ALTS was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services contracts CN-55153, CN-55154, CN-55155, CN-55156, CN-55157, CN-55158, CN-55159, and CN-55105. This work was also supported in part by intramural research program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. Some of the equipment and supplies used in these studies were donated or provided at reduced cost by Digene Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD; Cytyc Corporation, Boxborough, MA; National Testing Laboratories, Fenton, MO; DenVu, Tucson, AZ; TriPath Imaging, Inc., Burlington, NC; and Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Alameda, CA.

We thank the ALTS Group Investigators for their help in planning and conducting the trial. We thank Information Management Services, Inc., Rockville, MD for data management and programming support. We thank Meera Sangaramoorthy, Manu Sharma, and Kennita Riddick for the Roche Linear Array testing.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 June 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. 2003. A randomized trial on the management of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology interpretations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1881393-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. 2003. Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1881383-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance/Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions Triage Study (ALTS) Group. 2000. Human papillomavirus testing for triage of women with cytologic evidence of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: baseline data from a randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch, F. X., M. M. Manos, N. Munoz, M. Sherman, A. M. Jansen, J. Peto, M. H. Schiffman, V. Moreno, R. Kurman, and K. V. Shah for the International Biological Study on Cervical Cancer (IBSCC) Study Group. 1995. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 87796-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulkmans, N. W., J. Berkhof, L. Rozendaal, F. J. van Kemenade, A. J. Boeke, S. Bulk, F. J. Voorhorst, R. H. Verheijen, K. van Groningen, M. E. Boon, W. Ruitinga, M. van Ballegooijen, P. J. Snijders, and C. J. Meijer. 2007. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet 3701764-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carozzi, F. M., A. Del Mistro, M. Confortini, C. Sani, D. Puliti, R. Trevisan, L. De Marco, A. G. Tos, S. Girlando, P. D. Palma, A. Pellegrini, M. L. Schiboni, P. Crucitti, P. Pierotti, A. Vignato, and G. Ronco. 2005. Reproducibility of HPV DNA testing by Hybrid Capture 2 in a screening setting. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 124716-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castle, P. E., P. E. Gravitt, D. Solomon, C. M. Wheeler, and M. Schiffman. 2008. Comparison of Linear Array and Line Blot Assay for detection of human papillomavirus and diagnosis of cervical precancer and cancer in the Atypical Squamous Cell of Undetermined Significance and Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion Triage Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46109-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castle, P. E., J. Jeronimo, M. Schiffman, R. Herrero, A. C. Rodriguez, M. C. Bratti, A. Hildesheim, S. Wacholder, L. R. Long, L. Neve, R. Pfeiffer, and R. D. Burk. 2006. Age-related changes of the cervix influence human papillomavirus type distribution. Cancer Res. 661218-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castle, P. E., A. T. Lorincz, I. Mielzynska-Lohnas, D. R. Scott, A. G. Glass, M. E. Sherman, J. E. Schussler, and M. Schiffman. 2002. Results of human papillomavirus DNA testing with the Hybrid Capture 2 Assay are reproducible. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401088-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castle, P. E., M. Sadorra, F. Garcia, E. B. Holladay, and J. Kornegay. 2006. Pilot study of a commercialized human papillomavirus (HPV) genotyping assay: comparison of HPV risk group to cytology and histology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 443915-3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castle, P. E., M. Schiffman, M. C. Bratti, A. Hildesheim, R. Herrero, M. L. Hutchinson, A. C. Rodriguez, S. Wacholder, M. E. Sherman, H. Kendall, R. P. Viscidi, J. Jeronimo, J. E. Schussler, and R. D. Burk. 2004. A population-based study of vaginal human papillomavirus infection in hysterectomized women. J. Infect. Dis. 190458-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castle, P. E., M. Schiffman, R. D. Burk, S. Wacholder, A. Hildesheim, R. Herrero, M. C. Bratti, M. E. Sherman, and A. Lorincz. 2002. Restricted cross-reactivity of hybrid capture 2 with nononcogenic human papillomavirus types. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 111394-1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castle, P. E., M. H. Stoler, D. Solomon, and M. Schiffman. 2007. The relationship of community biopsy-diagnosed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 to the quality control pathology-reviewed diagnoses: an ALTS report. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 127805-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castle, P. E., C. M. Wheeler, D. Solomon, M. Schiffman, and C. L. Peyton. 2004. Interlaboratory reliability of Hybrid Capture 2. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 122238-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cogliano, V., R. Baan, K. Straif, Y. Grosse, B. Secretan, and F. El Ghissassi. 2005. Carcinogenicity of human papillomaviruses. Lancet Oncol. 6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuzick, J., C. Clavel, K. U. Petry, C. J. Meijer, H. Hoyer, S. Ratnam, A. Szarewski, P. Birembaut, S. Kulasingam, P. Sasieni, and T. Iftner. 2006. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int. J. Cancer 1191095-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuzick, J., A. Szarewski, H. Cubie, G. Hulman, H. Kitchener, D. Luesley, E. McGoogan, U. Menon, G. Terry, R. Edwards, C. Brooks, M. Desai, C. Gie, L. Ho, I. Jacobs, C. Pickles, and P. Sasieni. 2003. Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human papillomavirus: the HART study. Lancet 3621871-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Villiers, E. M., C. Fauquet, T. R. Broker, H. U. Bernard, and H. zur Hausen. 2004. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 32417-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gravitt, P. E., C. L. Peyton, T. Q. Alessi, C. M. Wheeler, F. Coutlee, A. Hildesheim, M. H. Schiffman, D. R. Scott, and R. J. Apple. 2000. Improved amplification of genital human papillomaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38357-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravitt, P. E., C. L. Peyton, R. J. Apple, and C. M. Wheeler. 1998. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 363020-3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero, R., P. E. Castle, M. Schiffman, M. C. Bratti, A. Hildesheim, J. Morales, M. Alfaro, M. E. Sherman, S. Wacholder, S. Chen, A. C. Rodriguez, and R. D. Burk. 2005. Epidemiologic profile of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J. Infect. Dis. 1911796-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyrgiou, M., G. Koliopoulos, P. Martin-Hirsch, M. Arbyn, W. Prendiville, and E. Paraskevaidis. 2006. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 367489-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsukura, T., and M. Sugase. 2004. Human papillomavirus genomes in squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Virology 324439-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayrand, M. H., E. Duarte-Franco, I. Rodrigues, S. D. Walter, J. Hanley, A. Ferenczy, S. Ratnam, F. Coutlee, and E. L. Franco. 2007. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 3571579-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munoz, N., F. X. Bosch, S. de Sanjose, R. Herrero, X. Castellsague, K. V. Shah, P. J. Snijders, and C. J. Meijer. 2003. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 348518-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naucler, P., W. Ryd, S. Tornberg, A. Strand, G. Wadell, K. Elfgren, T. Radberg, B. Strander, O. Forslund, B. G. Hansson, E. Rylander, and J. Dillner. 2007. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 3571589-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peyton, C. L., P. E. Gravitt, W. C. Hunt, R. S. Hundley, M. Zhao, R. J. Apple, and C. M. Wheeler. 2001. Determinants of genital human papillomavirus detection in a US population. J. Infect. Dis. 1831554-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peyton, C. L., M. Schiffman, A. T. Lorincz, W. C. Hunt, I. Mielzynska, C. Bratti, S. Eaton, A. Hildesheim, L. A. Morera, A. C. Rodriguez, R. Herrero, M. E. Sherman, and C. M. Wheeler. 1998. Comparison of PCR- and hybrid capture-based human papillomavirus detection systems using multiple cervical specimen collection strategies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 363248-3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poljak, M., I. J. Marin, K. Seme, and A. Vince. 2002. Hybrid Capture II HPV Test detects at least 15 human papillomavirus genotypes not included in its current high-risk probe cocktail. J. Clin. Virol. 25(Suppl. 3)S89-S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronco, G., P. Giorgi-Rossi, F. Carozzi, M. Confortini, P. P. Dalla, A. Del Mistro, A. Gillio-Tos, D. Minucci, C. Naldoni, R. Rizzolo, P. Schincaglia, R. Volante, M. Zappa, M. Zorzi, J. Cuzick, and N. Segnan for the New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening Working Group. 2008. Results at recruitment from a randomized controlled trial comparing human papillomavirus testing alone with conventional cytology as the primary cervical cancer screening test. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100492-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronco, G., P. Giorgi-Rossi, F. Carozzi, P. P. Dalla, A. Del Mistro, L. De Marco, M. De Lillo, C. Naldoni, P. Pierotti, R. Rizzolo, N. Segnan, P. Schincaglia, M. Zorzi, M. Confortini, and J. Cuzick. 2006. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology in primary screening of women younger than 35 years: results at recruitment for a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 7547-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ronco, G., N. Segnan, P. Giorgi-Rossi, M. Zappa, G. P. Casadei, F. Carozzi, P. P. Dalla, A. Del Mistro, S. Folicaldi, A. Gillio-Tos, G. Nardo, C. Naldoni, P. Schincaglia, M. Zorzi, M. Confortini, and J. Cuzick. 2006. Human papillomavirus testing and liquid-based cytology: results at recruitment from the new technologies for cervical cancer randomized controlled trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98765-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safaeian, M., R. Herrero, A. Hildesheim, W. Quint, E. Freer, L. J. Van Doorn, C. Porras, S. Silva, P. Gonzalez, M. C. Bratti, A. C. Rodriguez, and P. Castle. 2007. Comparison of the SPF10-LiPA system to the Hybrid Capture 2 Assay for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus genotypes among 5,683 young women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J. Clin. Microbiol. 451447-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sargent, A., A. Bailey, M. Almonte, A. Turner, C. Thomson, J. Peto, M. Desai, J. Mather, S. Moss, C. Roberts, and H. C. Kitchener on behalf of the ARTISTIC Study Group. 2008. Prevalence of type-specific HPV infection by age and grade of cervical cytology: data from the ARTISTIC trial. Br. J. Cancer 981704-1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasagawa, T., W. Basha, H. Yamazaki, and M. Inoue. 2001. High-risk and multiple human papillomavirus infections associated with cervical abnormalities in Japanese women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1045-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saslow, D., C. D. Runowicz, D. Solomon, A.-B. Moscicki, R. A. Smith, H. J. Eyre, and C. Cohen. 2002. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 52342-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiffman, M., and M. E. Adrianza. 2000. ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. Design, methods and characteristics of trial participants. Acta Cytol. 44726-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiffman, M., P. E. Castle, J. Jeronimo, A. C. Rodriguez, and S. Wacholder. 2007. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 370890-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiffman, M., R. Herrero, A. Hildesheim, M. E. Sherman, M. Bratti, S. Wacholder, M. Alfaro, M. Hutchinson, J. Morales, M. D. Greenberg, and A. T. Lorincz. 2000. HPV DNA testing in cervical cancer screening: results from women in a high-risk province of Costa Rica. JAMA 28387-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiffman, M., M. J. Khan, D. Solomon, R. Herrero, S. Wacholder, A. Hildesheim, A. C. Rodriguez, M. C. Bratti, C. M. Wheeler, and R. D. Burk. 2005. A study of the impact of adding HPV types to cervical cancer screening and triage tests. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiffman, M., C. M. Wheeler, A. Dasgupta, D. Solomon, and P. E. Castle. 2005. A comparison of a prototype PCR assay and hybrid capture 2 for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus DNA in women with equivocal or mildly abnormal Papanicolaou smears. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 124722-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneede, P., P. Hillemanns, F. Ziller, A. Hofstetter, E. Stockfleth, R. Arndt, and T. Meyer. 2001. Evaluation of HPV testing by Hybrid Capture II for routine gynecologic screening. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 80750-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solomon, D., M. Schiffman, and R. Tarone. 2001. Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93293-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoler, M. H., P. E. Castle, D. Solomon, and M. Schiffman. 2007. The expanded use of HPV testing in gynecologic practice per ASCCP-guided management requires the use of well-validated assays. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terry, G., L. Ho, P. Londesborough, J. Cuzick, I. Mielzynska-Lohnas, and A. Lorincz. 2001. Detection of high-risk HPV types by the hybrid capture 2 test. J. Med. Virol. 65155-162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright, T. C., Jr., L. S. Massad, C. J. Dunton, M. Spitzer, E. J. Wilkinson, and D. Solomon. 2007. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright, T. C., Jr., L. S. Massad, C. J. Dunton, M. Spitzer, E. J. Wilkinson, and D. Solomon. 2007. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197340-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright, T. C., Jr., M. Schiffman, D. Solomon, J. T. Cox, F. Garcia, S. Goldie, K. Hatch, K. L. Noller, N. Roach, C. Runowicz, and D. Saslow. 2004. Interim guidance for the use of human papillomavirus DNA testing as an adjunct to cervical cytology for screening. Obstet. Gynecol. 103304-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamazaki, H., T. Sasagawa, W. Basha, T. Segawa, and M. Inoue. 2001. Hybrid capture-II and LCR-E7 PCR assays for HPV typing in cervical cytologic samples. Int. J. Cancer 94222-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.