Abstract

BipA is a highly conserved prokaryotic GTPase that functions to influence numerous cellular processes in bacteria. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, BipA has been implicated in controlling bacterial motility, modulating attachment and effacement processes, and upregulating the expression of virulence genes and is also responsible for avoidance of host defense mechanisms. In addition, BipA is thought to be involved in bacterial stress responses, such as those associated with virulence, temperature, and symbiosis. Thus, BipA is necessary for securing bacterial survival and successful invasion of the host. Steady-state kinetic analysis and pelleting assays were used to assess the GTPase and ribosome-binding properties of S. enterica BipA. Under normal bacterial growth, BipA associates with the ribosome in the GTP-bound state. However, using sucrose density gradients, we demonstrate that the association of BipA and the ribosome is altered under stress conditions in bacteria similar to those experienced during virulence. The data show that this differential binding is brought about by the presence of ppGpp, an alarmone that signals the onset of stress-related events in bacteria.

GTPases represent a superfamily of proteins conserved across all species (5, 48). While there is a great deal of information about the functional and structural aspects of eukaryotic heterotrimeric and small GTPases, little is known about their prokaryotic counterparts. Bacterial GTPases do not behave as analogs of eukaryotic GTPases, which function primarily as signal transduction proteins. What is becoming increasingly apparent is that most, if not all, bacterial GTPases act in concert with the ribosome to affect cellular events such as viability, protein synthesis, and pathogenesis (8, 10, 26). Recent evidence suggests that they act to protect and stabilize the ribosome and link it to its external environment, thereby serving as regulation points (8, 12).

BipA, also known as TypA, is a highly conserved prokaryotic GTPase that functions to regulate numerous actions in bacteria (16, 46). It is a member of the family of bacterial translational GTPases. There are nine families of translational GTPases that have been classified based on their amino acid sequence similarities with archetypical translation factors such as EF-G, EF-Tu, and initiation factor 2 (IF2) (31). Typically, one BipA ortholog is present per genome. BipA orthologs are large proteins (∼67 kDa) consisting of an N-terminal GTPase domain, a central area of unknown function, and a C-terminal region that shares sequence homology with EF-G (16, 31).

The exact function of BipA in bacteria is not understood, although BipA has been implicated in the regulation of virulence and stress response events. For example, the expression of BipA in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is induced sevenfold in response to bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein, an antimicrobial polypeptide produced by granulocytes (2, 38). BipA is essential in EPEC for actin pedestal formation in host epithelial cells, flagellum-mediated motility, and resistance to host defense mechanisms. It is also required for expression of genes from the locus of enterocyte attachment and effacement and espC pathogenicity islands in both EPEC and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (16, 20). Additional evidence links BipA to the temperature-dependent expression of group 2 capsule gene clusters in E. coli (44). Perhaps most interesting is the finding that an EPEC BipA null mutant failed to initiate virulence events, whereas increased BipA expression in this same system upregulated these processes (16).

BipA has also been connected to bacterial stress responses, such as those associated with symbiosis and adverse growth conditions (27). In EPEC, E. coli K-12, Bacillus subtilis, and Pseudomonas putida, BipA has been shown to be crucial for low-temperature growth (3, 21, 37, 41). The most direct demonstration of the requirement of BipA for survival under adverse cellular conditions is a study showing that a Sinorhizobium meliloti BipA null strain failed to grow at low temperature, at low pH, and in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (27). In addition, this strain was unable to carry out the various functions associated with nitrogen-fixing symbiosis. Interestingly, all phenotypes could be rescued with the addition of wild-type S. meliloti or E. coli BipA. Moreover, in the plant Cucumis sativus, the absence of BipA suppresses sexual development, indicating that it is essential for proper developmental events (1).

The evidence presented above supports the concept that BipA functions in bacteria not simply as a translation factor but rather as one critical to the regulation of stress adaptation and pathogenicity. To begin to understand the mechanism of action of BipA, we investigated the GTPase and ribosome-binding properties of S. enterica BipA under adverse cellular conditions. This system was selected because Salmonella infections are a significant public health threat worldwide, yet Salmonella pathogenicity, which requires the coordinated expression of numerous virulence factors and pathways, is not well understood (6). Data are presented which parallel those previously reported for E. coli BipA to show that S. enterica BipA, in its GTP-bound state, associates primarily with the 70S ribosome (35). Therefore, BipA exhibits behavior analogous to that of a classic GTPase, binding to its partner in the GTP-bound state and dissociating upon hydrolysis of the GTP to GDP. Steady-state kinetic studies demonstrate that binding to the 70S ribosome enhances the GTP hydrolysis activity of the protein fourfold. In addition, evidence is presented to indicate that cellular levels of GTP and guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp) influence the association of BipA and the ribosome, providing a clue as to how BipA functions in stress adaptation in bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The cDNA encoding full-length Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium BipA was amplified from genomic DNA (ATCC 700720D) using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) with the oligonucleotides 5′ CTA ACG TAC ATA TGG TGA TCG AAA ATT TGC GTA ACA TCG CC 3′) (oligonucleotide a) and 5′ CGT GGA TTC TTA CTC TTC TTT CTG ACC ACG GTT CGC 3′) (oligonucleotide b), digested with NdeI and BamHI (NdeI and BamHI sites are underlined), and inserted into the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites in the T7 promoter-based expression vector pJES307 to yield pEF41 (49). An N-terminal His-tagged BipA construct was also made by insertion of the PCR product produced with oligonucleotide a described above and 5′ ACT CGA GTT AAT TTC TCT TTC GAG CTA TAA TAT GAA TTG G 3′ (the XhoI site is underlined), digested with NdeI and XhoI, and cloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites of the vector pET28a (Novagen) to produce plasmid pWW3. Plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing (UConn DNA Biotechnology Facility). The Lys18Ala (K18A) BipA variant was constructed using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) (primers 5′ TGA CCA TGG TGC AAC TAC CCT GGT TGA TAA GCT CCA GCA AT 3′ and 5′ ACC AGG GTA GTT GCA CCA TGG TCA ACG T 3′; mutagenesis sites are underlined). Plasmids were confirmed with DNA sequencing.

Protein expression and purification.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with either pEF41 or pWW3. Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin or 30 μg/ml kamamycin at 37°C. At mid-log phase, BipA expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Anatrace). The cells were grown for an additional 12 h at 18°C and harvested by centrifugation in a Beckman GSA rotor (5,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The cells were washed in 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (βME) (buffer A), pelleted a second time, and stored at −20°C.

All protein purification was carried out at 4°C. Untagged BipA was purified as follows. Cells were resuspended in buffer A and lysed by sonication. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C; SA600; Sorvall). Ammonium sulfate was added to the lysate to 55% saturation. The precipitated protein was collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C; SA600; Sorvall). The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM bis-Tris (pH 7.0), 5 mM βME and dialyzed against two 4-liter volumes of the same buffer. The protein was filtered, applied to a 70-ml MonoQ column (GE Healthcare), and eluted with a 0.15-to-0.6 M NaCl gradient. Fractions containing BipA were identified by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), dialyzed against 20 mM potassium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM βME, and loaded onto a 70-ml ceramic hydroxyapatite type 1 column (Bio-Rad). The protein was eluted using a 0.02-to-0.5 M NaCl gradient. BipA fractions were pooled, concentrated, and subjected to gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 200 16/60 preparation-grade column (GE Biosciences) equilibrated in buffer A.

His-tagged BipA was purified by application of clarified filtered lysate onto a 10-ml HisTrap FF crude column (GE Biosciences). BipA was eluted with a 20-to-500 mM imidazole gradient. Fractions containing BipA were pooled, concentrated, and subjected to gel filtration as described above. His-tagged and untagged BipA fractions were more than 95% pure, as assessed by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined with a Bradford assay using serum albumin as the standard.

Ribosome isolation.

Ribosomes were purified based on the method described by Spedding (47). Salmonella enterica (ATCC 700720) cells were grown at 37°C until mid-log phase. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C in a GSA rotor; Beckman) and resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM magnesium acetate [Mg(OAc)2], 30 mM NH4Cl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (buffer B). Cells were lysed by two passages through a French press at 15,000 lb/in2, and 500 U of RNase-free DNase I (Roche Diagnostics) was added. The lysates were clarified twice by centrifugation (30,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C in a Sorvall SA600 rotor). The resulting supernatant was layered onto a 1.1 M sucrose cushion in buffer B and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 16 h at 4°C using a type 70.1 Ti rotor (Beckman) to produce a crude ribosomal pellet (47). Pellets were resuspended by stirring overnight at 4°C. The resulting suspension was clarified by centrifugation (30,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C), and then ribosomes were pelleted at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C in a type 70.1 Ti rotor (Beckman), resuspended in buffer B, and stored at −80°C until use.

To obtain purified 70S ribosomes, 30 A260 units of the crude ribosome preparation were applied to a 35-ml 7-to-47% RNase- and DNase-free sucrose density gradient made with buffer B and centrifuged at 96,000 × g for 430 min at 13°C in an SW28 rotor (Beckman). All sucrose density gradients were prepared by discontinuous loading of multiple density layers followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C to produce a continuous gradient. The 70S ribosomes were quantitated by absorbance at 260 nm, where 1 optical density unit is equal to 23 pmol.

To isolate 50S and 30S ribosomal subunits, the ribosomal pellet was resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM Mg(OAc)2, 500 mM NH4Cl, 2 mM DTT. Thirty A260 units was applied to a 35-ml 7-to-47% sucrose gradient in the same buffer and centrifuged at 96,000 × g for 430 min at 13°C. Fractions containing the individual subunits were pooled and pelleted at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C in a type 70.1 Ti rotor (Beckman). Pellets were resuspended in buffer B by gentle stirring overnight at 4°C. Ribosomes and ribosomal subunits were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. Quantitation of subunits was determined by absorbance at 260 nm, where 1 A260 unit is equivalent to 69 or 34.5 pmol of 30 or 50S ribosomes, respectively (13).

Steady-state GTP hydrolysis assays.

Nucleotide hydrolysis activities of BipA were determined by measuring the release of free phosphate by the malachite green-ammonium molybdate colorimetric assay (28). Reactions were performed at constant BipA concentrations of 1 μM and various GTP (GE Biosciences) concentrations from a 10-fold to a 5,000-fold molar excess of protein, which falls within the linear range of the assay. Hydrolysis reactions proceeded at 37°C in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 2 mM DTT for 180 min. Color formation was measured at 660 nm using a Beckman Coulter DU 640 spectrophotometer. Reactions were repeated a minimum of three times. Values for kcat were determined by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation with nonlinear regression curve fitting using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.; version 4.0) and are reported as average values with standard deviations. To study the effect of ribosomes on the GTPase activity of the protein, 5 nM of purified ribosomes was incubated with 1 μM BipA for 15 min at 25°C. The reaction mixture was then assayed for hydrolysis activity as described above.

Ribosome profiles.

The in vivo association of BipA and the ribosome was monitored by using sucrose density gradients. S. enterica SB300A cells (32) transformed with pWW3, encoding His-tagged BipA, were grown at 37°C until mid-log phase. Arabinose was added to a final concentration of 0.2%. After 2 h, the cells were harvested, resuspended in buffer B, and lysed using a French press. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). Thirty A260 units of the supernatant was applied to a 35-ml 7-to-47% sucrose density gradient and centrifuged at 96,000 × g for 430 min at 13°C using a SW-28 rotor (Beckman). The gradient was monitored at 254 nm and fractionated (1.5 ml) using an AKTA fast-performance liquid chromatograph (GE Biosciences). Individual fractions were trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitated, resuspended in SDS loading buffer, and run on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel. Fractions containing His-tagged BipA were identified by immunoblotting and detected using a HisDetector Western blot kit (KPL, Inc.).

To assess the association of BipA and the ribosome during a stringent response, SB300A cells transformed with the His-tagged BipA plasmid (pWW3) were grown at 37°C until mid-log phase. Arabinose was then added to a final concentration of 0.2%. After 90 min, serine hydroxamate (SHX) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. Cells were grown for an additional 30 min, harvested by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C in a Beckman GSA rotor) and resuspended in buffer B. The cells were lysed using a French press. Sucrose density centrifugation and immunoblotting as described above were used to analyze cosedimentation of BipA with various ribosomal species. Similar experiments were carried out to observe the association of BipA under conditions of heat shock and cold shock. Specifically, SB300A cells containing His-BipA were grown under the conditions described above. After induction with arabinose, the cells continued to grow at either 16°C for 14 h (cold shock) or 42°C for 1 h. The cells were harvested, and the binding of BipA to the ribosome was assessed as described above.

Pelleting assays.

Pelleting assays were performed based on the method described by Daigle and Brown (13). 70S, 50S, and 30S ribosomal species (100 pmol) were incubated with 100 pmol of His-tagged BipA and, where indicated, 2 mM of GDP, GMPPNP (Sigma-Aldrich), GTP (GE Biosciences), or ppGpp (Trilink Biotechnologies) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Mg(OAc)2, and 2 mM DTT for 30 min at 30°C. Samples (20 μl) were overlaid onto a 2.2-ml sucrose cushion consisting of 1.1 M sucrose, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM Mg(OAc)2, 50 mM NH4Cl, and 2 mM of either GDP, GMPPNP, or GTP and centrifuged at 250,000 × g for 150 min at 4°C in an S55-A rotor (Sorvall). The supernatant was removed, and the pellets were dissolved in 1 ml of buffer B. Supernatant and pellet fractions were precipitated with 10% TCA and resuspended in 200 μl 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and 25 μl was loaded onto a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel. Prestained Kaleidoscope markers (Bio-Rad) were used as molecular mass markers. Proteins from the gel were transferred onto an Immobilon-P transfer membrane (Millipore), and His-tagged BipA was visualized using a HisDetector Western blot kit (KPL, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Pure BipA in the absence of ribosomes and BipA K18A were included as controls.

Pelleting assays were also used to determine stoichiometries of the BipA-ribosome complexes. 70S or 30S ribosomal subunits (100 pmol) were incubated with 25 to 500 pmol of His-BipA and 2 mM of GMPPNP (Sigma-Aldrich) or ppGpp (Trilink Biotechnologies) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM Mg(OAc)2, 50 mM NH4Cl for 30 min at 30°C. Samples were overlaid onto sucrose cushions, and pelleting assays were carried out as described above. The amount of ribosome-bound His-tagged BipA in the pellet was calculated from a standard curve. Western blots were photographed and analyzed using a Kodak Gel Logic 100 imaging and analysis system (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY).

RESULTS

BipA binds to 70S ribosomes in vivo.

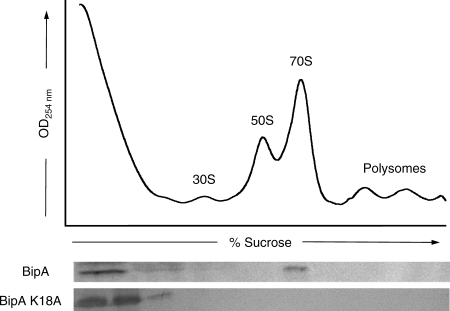

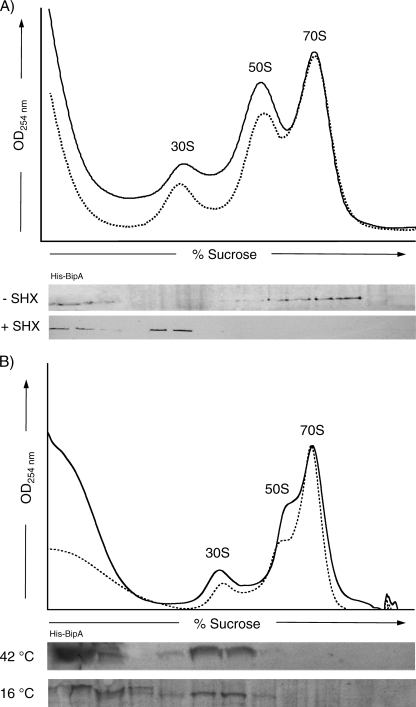

The in vivo association of S. enterica BipA and the ribosome under normal growth conditions was monitored using sucrose density gradients. No exogenous nucleotide was added to the samples. As shown in Fig. 1, BipA cosediments with 70S ribosomes. BipA was not detected in fractions corresponding to either the 30S or 50S ribosomal species or to polysomes; however, BipA was found at the top of the gradient. This observation is consistent with the idea that BipA dissociates from the ribosome over the course of the experiment or that BipA-binding sites on the ribosome are saturated. Alternatively, since no exogenous nucleotide was added to the cell extracts, the unbound BipA at the top of the gradient may be present in its GDP- or guanine nucleotide-free state. Similar results have been reported for E. coli BipA (35). Sucrose gradient profiles were also used to assess ribosome binding by a BipA construct with a single site-directed substitution, K18A. The comparable modification in Ras (K16A) causes a severe reduction in GTP turnover rates due to the inability of the protein to properly coordinate the guanine nucleotide and Mg2+ in its active site (36, 48). Equivalent site-directed substitutions are routinely used to produce “inactive” GTPases. BipA K18A was unable to bind to the ribosome, suggesting that nucleotide binding and/or turnover by BipA is necessary for its association with the ribosome.

FIG. 1.

Ribosome association profiles of S. enterica BipA under normal growth conditions. SB300A cells expressing minimal levels of BipA or BipA K18A were treated with 0.1 mg/ml chloramphenicol for 3 min prior to harvest. Cell lysates were prepared and separated over 7-to-47% sucrose gradients. Gradient fractions were TCA precipitated and analyzed for BipA by immunoblotting against the His6 tag using a HisDetector Western blot kit. The positions of the 30S, 50S, and 70S ribosomal species are labeled, as well as those of polysomes.

BipA binds to 70S ribosomes in the GTP-bound state.

An in vitro pelleting assay was used to determine if S. enterica BipA binds to isolated S. enterica ribosomes in the apo-, GDP-bound, or GTP-bound form. Full-length untagged and His-tagged S. enterica BipA was overexpressed in E. coli and purified by standard chromatographic methods. The addition of a six-residue histidine tag at the N terminus of BipA expedited protein purification and did not adversely affect the GTPase activity of the protein (discussed below). SDS-PAGE analysis of both proteins shows a single band with an apparent molecular mass of ∼74 kDa. Because the apparent mass of the proteins was larger than expected, mass spectrometry was used to confirm that the masses of the purified proteins were consistent with untagged and His-tagged full-length BipA. Gel filtration chromatography indicated that both proteins behave as monomers in solution, as determined by comparison to molecular mass standards (data not shown).

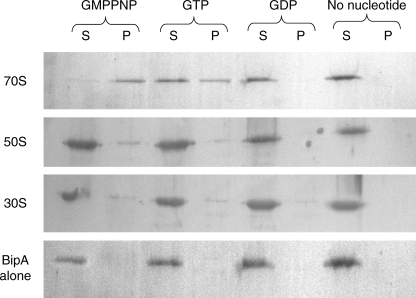

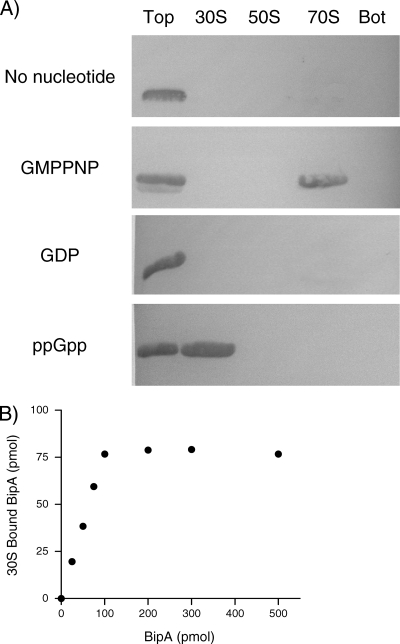

Purified BipA and either 30S, 50S, or 70S ribosomes were incubated in the presence of various guanine nucleotides, including the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog GMPPNP, and then sedimented through a 1.1 M sucrose cushion. As shown in Fig. 2, S. enterica BipA exhibits some binding to all three ribosomal species but associates predominantly with 70S ribosomes in the GMPPNP-bound state. E. coli BipA demonstrates the same pattern of ribosome association (35). Not surprisingly, BipA is observed in both the supernatant and pelleted fractions of the BipA-GTP-70S sample. This is likely due to partial hydrolysis of GTP to GDP during centrifugation with the concurrent dissociation of the GDP-bound BipA from the ribosome. These data indicate that BipA has maximum affinity for 70S ribosomes in the GTP-bound state. In addition, these results suggest that the association of BipA and the ribosome is likely regulated by the hydrolysis of the bound GTP to GDP or by the loss of bound GTP.

FIG. 2.

S. enterica BipA binds preferentially to 70S ribosomes in the presence of GTP. Equimolar amounts of purified His-tagged BipA and purified 30S, 50S, or 70S ribosomal species were incubated with excess guanine nucleotide (GDP, GTP, or GMPNP) for 30 min at 30°C. The reaction mixtures were sedimented through a 1.1 M sucrose cushion. The ribosome-associated fraction (pellet [P]) and the unbound fraction (supernatant [S]) were TCA precipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. BipA was detected with a HisDetector Western blot kit. Pure BipA in the absence of ribosomes was included as a control.

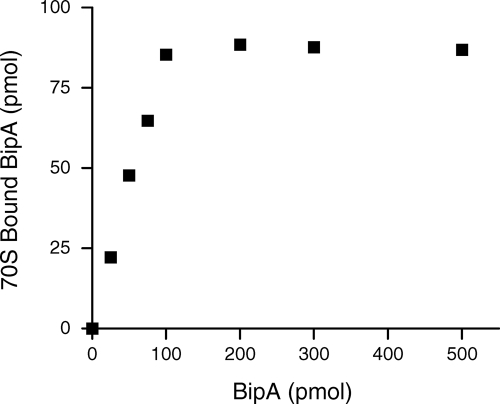

Pelleting assays were also utilized to measure the stoichiometry of S. enterica BipA binding to 70S ribosomes in the presence of GMPPNP. Increasing concentrations of BipA, up to 500 pmol, were incubated with 100 pmol of 70S S. enterica ribosomes. The ribosomes were pelleted through a sucrose cushion and the amount of 70S-BipA-GMPPNP determined by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3, BipA-GMPPNP binds to 70S particles in a stoichiometry of approximately 1:1.

FIG. 3.

Stoichiometry of the S. enterica BipA-ribosome complexes. The binding of various amounts of BipA-GMPPMP to 70S ribosomes (100 pmol) is shown. BipA-ribosome complexes were isolated using a sucrose cushion. The amount of ribosome-bound BipA was measured by Western blotting using a HisDetector kit and compared with known amounts of BipA used as standards.

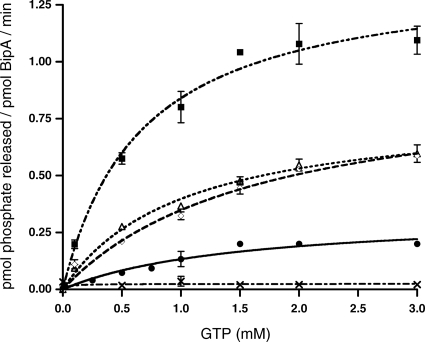

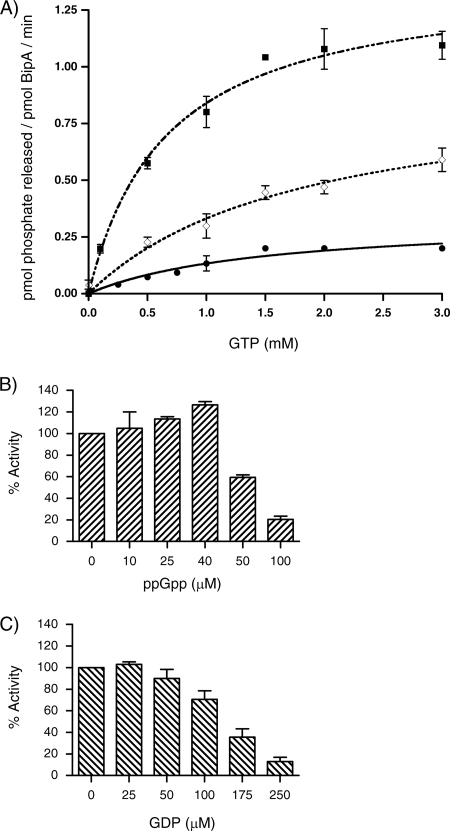

GTP hydrolysis by BipA is stimulated in the presence of the ribosome.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of GTP hydrolysis by S. enterica BipA, in the presence and absence of various ribosomal species, was carried out using the malachite green-molybdate colorimetric assay (Fig. 4). Similar to other bacterial GTPases, BipA slowly catalyzes the hydrolysis of GTP. The kcat values for His-tagged and untagged BipA were similar: 19.8 ± 0.1 h−1 and 27.0 ± 0.2 h−1, respectively. The BipA K18A construct was used to assess background levels of GTP hydrolysis. Hydrolysis rates of the BipA K18A protein fell below levels that are easily detectable by the malachite green assay. This is indicative of a protein with greatly diminished capacity to carry out hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, presumably due to a decreased ability to bind nucleotide. These results are in agreement with our observation that BipA K18A is unable to bind ribosomes in vivo.

FIG. 4.

GTP hydrolysis rates of BipA in the presence of various ribosomal species. Kinetic assays were done by utilizing the malachite green phosphate assay as described in Materials and Methods. Initial rates were determined based on the amount of phosphate produced after the reactions had proceeded for 180 min at 37°C. Reactions were done in triplicate. Values of kcat were determined by fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression algorithms furnished with the GraphPad Prism software package (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Background hydrolysis levels were assessed by measuring the GTPase activity of BipA K18A (×). GTP hydrolysis rates of BipA alone (•) and in the presence of 5 nM of either 30S (⋄), 50S (▵), or 70S (▪) ribosomes are shown.

Similar to other bacterial GTPases, the GTPase activity of S. enterica BipA was enhanced in the presence of ribosomes. When BipA was incubated with 30S and 50S subunits, an increase in kcat was detected: 55.8 ± 0.5 h−1 and 48.0 ± 0.6 h−1, respectively. A larger increase was observed upon the addition of the 70S ribosomes: 83.9 ± 0.2 h−1 (Fig. 4).

Association of BipA and ribosomes under conditions of stress.

As stated previously, numerous lines of evidence have indicated that BipA is involved in bacterial stress responses such as those associated with virulence and the stringent response (16, 20, 27, 37). By definition, the stringent response refers to an adaptation of bacteria to the onset of stress, usually in the form of nutritional depletion (11, 23). Because the cellular actions of BipA are determined by its GTPase activities as well as its association with the ribosome, sucrose gradients were used to assess the association of BipA and the ribosome after the onset of the stringent response.

SB300A cells expressing minimal levels of the His-tagged BipA were grown to mid-log phase in minimal medium, and then SHX was added. SHX, an amino acid analog which inhibits the charging of serine tRNAs, is routinely used to elicit the stringent response (51). After 20 min, the cells were harvested and the association of BipA with the ribosome assessed. As shown in Fig. 5A, there was a substantial change in the association pattern of BipA and the ribosome following the onset of the stringent response. A portion of BipA was present at the top of the gradient, and the remainder cofractionated with the 30S ribosomal subunits. This is in contrast to a parallel experiment without SHX, where BipA was bound to 70S particles. Interestingly, the relative amounts of 30S, 50S, and 70S ribosomal species observed in the normal and stressed ribosome profiles were similar. Therefore, the observed changes in the BipA-ribosome association under stringent-response conditions is not a result of an increase or decrease of ribosomal species but is in fact an alteration in the specificity of the association of BipA with different ribosomal species.

FIG. 5.

Cosedimentation of BipA with ribosomes under normal and stressed growth conditions. (A) S. enterica SB300A cells containing the plasmid encoding His-tagged BipA were grown in minimal medium to mid-log phase and induced with 0.2% arabinose. After 90 min, SHX was added to the cells to 0.1 mM to trigger the stringent response. The cells were grown for an additional 30 min and then harvested. Lysates were clarified and sedimented through 7-to-47% sucrose gradients. The resulting ribosomal UV profile measured at 254 nm (solid line, with SHX; dashed line, without SHX) is shown. Gradient fractions were TCA precipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting against His-tagged BipA (+ SHX). A parallel experiment without SHX (- SHX) demonstrated that under normal growth conditions BipA associates with 70S ribosome. (B) Similar experiments were carried out after high-temperature and low-temperature growth. SB300A cells transformed with His-tagged BipA were grown to mid-log phase induced with 0.2% arabinose. The cultures continued to grow at either 42°C for 1 h or 16°C for 4 h before harvest. Cosedimentation analysis was carried out as described above. As in the stringent-response experiment, BipA associates with 30S particles.

To determine whether the association of BipA and the ribosome is also modified under other adverse cellular conditions, BipA-ribosome complex formation was assessed under conditions of extreme-temperature growth. In brief, SB300A cells transformed with His-tagged BipA were grown at 37°C in minimal medium until mid-log phase, and BipA expression was induced. The cultures continued to grow for an additional hour at 42°C or 4 h at 16°C before cells were harvested. Cell lysates were separated by sucrose gradients, and the ribosome association patterns were determined by Western blotting (Fig. 5B). The distribution of BipA was similar to that observed during the stringent response. That is, BipA cosedimented with the 30S particles, whereas none was detected bound to 70S ribosomes.

Association of BipA and ppGpp in vitro.

It is often the case that when bacterial cells are stressed, GTP concentrations fall rapidly while levels of the alarmone guanosine-3′,5′-bisdiphosphate (ppGpp) become elevated (34). Thus, it is possible that the change in the association of BipA with the ribosome could be due to a substantial increase in the ppGpp levels in the cell upon the addition of SHX. To test this hypothesis, an in vitro ribosome-binding assay was utilized. Purified S. enterica ribosomes and His-tagged BipA were incubated with excess amounts of GDP, GMPPNP, or ppGpp. The samples were applied to sucrose gradients and centrifuged, and fractions from the ribosome profile were analyzed by Western blotting. Consistent with previous data, in the absence of nucleotide or in the GDP-bound state, BipA was observed at the top of the gradient, indicating that it was free in solution and did not associate with any ribosomal species (Fig. 6A). Moreover, BipA cofractionated with the 70S ribosomes when incubated with GMPPNP, the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog. Strikingly, when BipA was mixed with excess ppGpp, it was detected in the ribosome fraction corresponding to the 30S subunit, suggesting that ppGpp influences the ribosome association properties of BipA.

FIG. 6.

Binding of BipA to the ribosome in the presence of GDP, GMPPNP, and ppGpp. (A) Binding was measured by incubating equimolar concentrations of ribosomes and His-tagged BipA in the presence of a 20-fold molar excess of GDP, GMPPNP, or ppGpp at 30°C for 30 min. The sample was then applied to a 7-to-47% sucrose gradient and centrifuged. Fractions containing 30S, 50S, and 70S ribosomal subunits were pooled, as well as the top and the bottom of the gradient. Unbound BipA remains on the top of the gradient. The bottom of the gradient was collected to look for any precipitated components. The samples were analyzed by immunoblotting and detected using a HisDetector Western blot kit. (B) The binding of increasing amounts of BipA-ppGpp to 30S ribosomal subunits (100 pmol) was measured as described for Fig. 3 by isolating BipA-ribosome complexes using a sucrose cushion. The amount of ribosome-bound BipA was measured by Western blotting using a HisDetector kit and compared with known amounts of BipA as standards.

The stoichiometry of S. enterica BipA-30S complex in the presence of ppGpp was determined using pelleting assays. Increasing concentrations of BipA were incubated with 100 pmol of 30S ribosomes. The ribosomes were pelleted through a sucrose cushion, and the amount of 30S-BipA-ppGpp was quantified based on a standard curve. As shown in Fig. 6B, BipA associates with 30S particles in a 1:1 molar ratio when ppGpp is present.

BipA is sensitive to levels of GDP and ppGpp.

Hydrolysis assays were used to determine what effect, if any, ppGpp might have on the GTPase activities of BipA. Over the standard time course of the reaction (180 min), no significant hydrolysis of ppGpp by BipA alone was observed (data not shown). To determine if the presence of ppGpp affects the 70S-stimulated GTP hydrolysis activity of BipA, 1 μM of BipA and 1 μM of ppGpp were incubated together for 30 min at 25°C and then assayed for hydrolysis activity (Fig. 7A). Compared to the 70S-stimulated hydrolysis values of BipA reported above, there was a slight decrease in kcat, from 83.9 ± 0.2 h−1 to 56.2 ± 3.9 h−1. This suggests that the presence of ppGpp negatively influences the GTP hydrolysis rates of the protein, perhaps by altering the affinity of BipA for GTP.

FIG. 7.

The influence of ppGpp on the GTPase activity of BipA. (A) Steady-state kinetic assays measuring the 70S-stimulated GTP hydrolysis rates of BipA (1 μM) in the presence of ppGpp were done as described for Fig. 4. Intrinsic GTP hydrolysis rates of BipA alone (•), with 5 nM of 70S (▪) ribosomes and with 5 nM of 70S ribosomes and 1 μM ppGpp (⋄) are shown. (B) Intrinsic rate of hydrolysis of GTP (1 mM) by BipA (1 μM) measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of ppGpp. Rates were determined based on the amount of phosphate produced after the reactions proceeded for 180 min at 37°C and reported relative to wild-type BipA that has an activity of 0.13 mol phosphate (mol BipA)−1 min−1. Reactions were done in triplicate. (C) The intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis by BipA was measured in the presence of increasing amounts of GDP as described for panel B.

To further characterize this event, the intrinsic GTPase activity of BipA was measured in the presence of increasing amounts of ppGpp. Intriguingly, low concentrations of ppGpp, below 40 μM, have a stimulatory affect on the GTPase activity of BipA; however, above 40 μM ppGpp, we observe a marked inhibitory affect (Fig. 7B). In a similar manner, GDP was added to the hydrolysis reaction mixture. An increase in GDP-GTP ratios in the reaction mixture resulted in inhibition of the GTP hydrolysis rates of BipA but at a much higher concentration than seen with ppGpp (Fig. 7C). This inhibition of the GTPase activity by GDP was previously observed for E. coli BipA (35).

DISCUSSION

GTPases exert their regulatory effects through their ability to form specific stable interactions with cognate partners. Such interactions are dictated by the nucleotide-bound state of the protein, as is the case of the association of BipA with the ribosome. Our analysis of the ribosome-binding properties of S. enterica BipA indicate that although BipA shows some affinity for all three ribosomal subunits, it associates predominantly with the 70S subunit in its GTP-bound state. We also demonstrated that it does not bind to the 70S ribosome in its GDP-bound state. Thus, BipA behaves as a classic GTPase, binding to its cognate partner in the GTP-bound form and dissociating when the bound GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP. These results are consistent with those previously reported for E. coli BipA, suggesting that this mode of action is common to the BipA family of proteins (35).

Our steady-state kinetic studies indicate that BipA alone hydrolyzes GTP at a low rate (kcat ∼ 22 h−1). The steady-state rates of GTP turnover by BipA is slightly higher than rates of p21H-Ras, E. coli EF-Tu, and E. coli YjeQ, which are 1.7, 2.2, and 8.1 h−1, respectively (14, 17, 45) but is lower than those reported for Thermotoga maritima and E. coli EngA (4, 43). Upon the addition of 30S or 50S ribosomal subunits, a slight increase in kcat was observed, whereas a greater increase was seen in the presence of intact ribosomes. These data indicate that, as with most bacterial GTPase families, GTP hydrolysis by BipA is stimulated by the presence of the ribosome. We also determined background GTPase activity by constructing a BipA K18A site-directed substitution. The K18A construct demonstrated little or no GTP hydrolysis activity and did not bind to 70S ribosomes in the presence of GTP.

Of interest is the recently established link between bacterial GTPases and ppGpp, an alarmone synthesized from GTP (9, 33). ppGpp acts as a global regulator in bacteria and is essential for physiological adaptation to diverse environmental conditions (7, 30). This adaptation is crucial if bacteria are to survive periods of stress, nutrient depletion, and events associated with interaction with eukaryotic hosts, for example, during pathogenesis and symbiosis. This is especially important for bacteria associated with food-borne infections, such as S. enterica, as they experience environmental extremes during transfer, ingestion, and digestion.

IF2 is an essential GTPase that functions to position the initiator fMet-tRNA on the P site of the ribosome to enhance translation initiation. It was shown that ppGpp binds to IF2, inhibiting the formation of the initiation complex and downregulating translation initiation (33). Milon et al. speculate that IF2 acts as a metabolic sensor switch (33). When GTP is present, the protein is active and protein synthesis proceeds. During stress, cellular GTP levels drop and ppGpp levels are elevated. Concurrently, IF2 binds to ppGpp, translation events are stalled, and the bacteria are protected from adverse cellular conditions.

The Obg/CgtA family is another family of prokaryotic GTPases whose primary function in the cell is 50S ribosome assembly (8). For years, emerging evidence also suggested a relationship between Obg and stress responses associated with ppGpp. For example, B. subtilis Obg cocrystallized with ppGpp in its nucleotide-binding site (9). In another study, E. coli CgtA copurified with SpoT, a bifunctional (p)ppGpp synthetase (52). SpoT, together with RelA, regulates ppGpp accumulation in response to cell stress and nutrient deprivation (7). Both SpoT and RelA are thought to associate with and are functionally supported by the ribosome (19, 39, 42). Recently, CgtA was shown to promote SpoT-dependent activities on the ribosome (24). This study, as well as additional work with Vibrio cholerae, revealed that the interaction of CgtA and SpoT influences ppGpp levels in vivo (40).

We have also discovered a link between BipA and ppGpp. As stated previously, numerous lines of evidence indicate that BipA is involved with the regulation of virulence and stress-related genes. Therefore, we hypothesized that ribosome binding or biochemical properties of BipA may also be affected by adverse cellular conditions. Sucrose density gradients were used to observe the association of BipA and the ribosome under normal growth conditions and after the onset of the stringent response. During exponential growth, BipA binds to 70S ribosomes. Strikingly, when SHX is added to the cells, there is a dramatic change in the ribosome association pattern of BipA. BipA cosediments with 30S ribosomal subunits. However, the relative quantities of 70S ribosome and individual subunits are unaltered. Therefore, the 30S binding by BipA is not due to the disruption of the 70S ribosome into its component parts but is rather a change in the specificity of BipA for a given ribosomal particle.

The stringent response refers to an adaptation of bacteria to nutrient depletion and correlates with an increase in levels of ppGpp (23). Thus, the stringent response has been utilized extensively to examine the effect of ppGpp induction on cellular processes (23, 30, 51). In a nutrient-rich environment, cellular GTP concentrations are high and those of ppGpp are low. When bacterial cells are starved for amino acids or carbon, GTP concentrations fall rapidly while levels of ppGpp rise (34). GTPases are well suited to bind ppGpp (9), and so it was possible that under adverse cellular conditions, BipA was bound to ppGpp. Using ribosome-binding assays with purified components, we demonstrated that GTP-bound BipA associates with the 70S ribosomes, whereas in the presence of excess ppGpp, BipA associates only with 30S ribosomal subunits. Because these findings mirror the in vivo results, it is probable that the increase in ppGpp brought on by SHX addition is responsible for BipA binding to the 30S ribosomes. We also demonstrated that ppGpp inhibits GTPase activities of BipA as well as 70S-stimulated hydrolysis, suggesting that GTP and ppGpp both bind to the nucleotide-binding site of BipA.

To build on the hypothesis that the cellular environment influences the ribosome-binding properties of BipA, the association of BipA and the ribosome was examined under high- and low-temperature growth conditions. BipA cosediments with the 30S ribosome species under both conditions. In general, cellular levels of ppGpp become elevated in the course of heat shock, whereas they have been reported to both increase and decrease during cold shock (18, 22, 25, 29, 50). Therefore, while elevated ppGpp levels can account for the formation of the 30S-BipA complex during nutrient depletion and temperature elevation, the association of BipA with 30S particles observed in vivo during cold shock might involve some alternate stress signals.

Taken together, the results establish the idea that BipA has two ribosome-binding modes. Under normal cellular conditions, GTP-bound BipA associates with 70S ribosomes. However, under conditions of stress, BipA associates with 30S ribosomes. Therefore, we speculate that at least two BipA ribosome complexes, one promoted by GTP and the other related to ppGpp and possibly other stress factors, influence how the bacteria respond to environmental conditions and therefore may affect translation, stress responses, and virulence events. Studies are ongoing to identify the nature of the BipA ribosome complexes in the hope of shedding light on the molecular mechanism of action of this protein.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Connecticut Research Foundation and an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0635519T) awarded to V.L.R.

We thank Eileen Fox and Weimin Wang for construction of the initial BipA constructs, Jeffrey McKinney for the gift of the SB300A strain, Daniel Gage for guidance with the stress response experiments, Ann Stock for critical reading of the manuscript, and Terri G. Kinzy for assistance on multiple aspects of the project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barak, M., and T. Trebitsh. 2007. A developmentally regulated GTP binding tyrosine phosphorylated protein A-like cDNA in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Plant Mol. Biol. 65829-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker, H. C., N. Kinsella, A. Jaspe, T. Friedrich, and C. D. O'Connor. 2000. Formate protects stationary-phase Escherichia coli and Salmonella cells from killing by a cationic antimicrobial peptide. Mol. Microbiol. 351518-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckering, C. L., L. Steil, M. H. W. Weber, U. Volker, and M. A. Marahiel. 2002. Genomewide transcriptional analysis of the cold shock response in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1846395-6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharat, A., M. Jiang, S. M. Sullivan, J. R. Maddock, and E. D. Brown. 2006. A cooperative and critical role for both G domains in the GTPase activity and cellular function of ribosome-associated Escherichia coli EngA. J. Bacteriol. 1887992-7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne, H. R., D. A. Sanders, and F. McCormick. 1991. The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature 3491117-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle, E. C., J. L. Bishop, G. A. Grassl, and B. B. Finlay. 2007. Salmonella: from pathogenesis to therapeutics. J. Bacteriol. 1891489-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braeken, K., M. Moris, R. Daniels, J. Vanderleyden, and J. Michiels. 2006. New horizons for (p) ppGpp in bacterial and plant physiology. Trends Microbiol. 1445-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, E. D. 2005. Conserved P-loop GTPases of unknown function in bacteria: an emerging vital ensemble in bacterial physiology. Biochem. Cell Biol. 83738-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buglino, J., V. Shen, P. Hakimian, and C. D. Lima. 2002. Structural and biochemical analysis of the Obg GTP binding protein. Structure 101581-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldon, C. E., and P. E. March. 2003. Function of the universally conserved bacterial GTPases. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6135-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cashel, M., D. M. Gentry, V. J. Hernandez, and D. Vinella. 1996. The stringent response, p. 1458-1496. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 12.Comartin, D. J., and E. D. Brown. 2006. Non-ribosomal factors in ribosome subunit assembly are emerging targets for new antibacterial drugs. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6453-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daigle, D. M., and E. D. Brown. 2004. Studies of the interaction of Escherichia coli YjeQ with the ribosome in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 1861381-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daigle, D. M., L. Rossi, A. M. Berghuis, L. Aravind, E. V. Koonin, and E. D. Brown. 2002. YjeQ, an essential, conserved, uncharacterized protein from Escherichia coli, is an unusual GTPase with circularly permuted G-motifs and marked burst kinetics. Biochemistry 4111109-11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reference deleted.

- 16.Farris, M., A. Grant, T. B. Richardson, and C. D. O'Connor. 1998. BipA: a tyrosine-phosphorylated GTPase that mediates interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 28265-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frech, M., T. A. Darden, L. G. Pedersen, C. K. Foley, P. S. Charifson, M. W. Anderson, and A. Wittinghofer. 1994. Role of glutamine-61 in the hydrolysis of GTP by p21H-ras: an experimental and theoretical study. Biochemistry 333237-3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallant, J., L. Palmer, and C. C. Pao. 1977. Anomalous synthesis of ppGpp in growing cells. Cell 11181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentry, D. R., and M. Cashel. 1995. Cellular localization of the Escherichia coli SpoT protein. J. Bacteriol. 1773890-3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grant, A. J., M. Farris, P. Alefounder, P. H. Williams, M. J. Woodward, and C. D. O'Connor. 2003. Co-ordination of pathogenicity island expression by the BipA GTPase in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC). Mol. Microbiol. 48507-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant, A. J., R. Haigh, P. Williams, and C. D. O'Connor. 2001. An in vitro transposon system for highly regulated gene expression: construction of Escherichia coli strains with arabinose-dependent growth at low temperatures. Gene 280145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikehara, K., H. Okada, K. Maeda, A. Ogura, and K. Sugae. 1984. Accumulation of relA gene-independent ppGpp in Bacillus subtilis vegetative cells upon temperature shift-down. J. Biochem. 95895-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain, V., M. Kumar, and D. Chatterji. 2006. ppGpp: stringent response and survival. J. Microbiol. 441-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, M., S. M. Sullivan, P. K. Wout, and J. R. Maddock. 2007. G-protein control of the ribosome-associated stress response protein SpoT. J. Bacteriol. 1896140-6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones, P. G., M. Cashel, G. Glaser, and F. C. Neidhardt. 1992. Function of a relaxed-like state following temperature downshifts in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1743903-3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karbstein, K. 2007. Role of GTPases in ribosome assembly. Biopolymers 871-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiss, E., T. Huguet, V. Poinsot, and J. Batut. 2004. The typA gene is required for stress adaptation as well as for symbiosis of Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 with certain Medicago truncatula lines. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17235-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanzetta, P. A., L. J. Alvaez, P. S. Reinach, and O. A. Candia. 1979. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal. Biochem. 10095-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackow, E. R., and F. N. Chang. 1983. Correlation between RNA synthesis and ppGpp content in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magnusson, L. U., A. Farewell, and T. Nystrom. 2005. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 13238-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margus, T., M. Remm, and T. Tenson. 2007. Phylogenetic distribution of translational GTPases in bacteria. BMC Genomics 108-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKinney, J., C. Guerrier-Takada, J. Gala, and S. Altman. 2002. Tightly regulated gene expression system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1846056-6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milon, P., E. Tischenko, J. Tomsic, E. Caserta, G. Folkers, A. La Teana, M. V. Rodnina, C. L. Pon, R. Boelens, and C. O. Gualerzi. 2006. The nucleotide-binding site of bacterial translation initiation factor 2 (IF2) as a metabolic sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10313962-13967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray, K. D., and H. Bremer. 1996. Control of spoT-dependent ppGpp synthesis and degradation in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 25941-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens, R. M., G. Pritchard, P. Skipp, M. Hodey, S. R. Connell, K. H. Nierhaus, and C. D. O'Connor. 2004. A dedicated translation factor controls the synthesis of the global regulator Fis. EMBO J. 233375-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Pai, E. F., U. Krengel, G. A. Petsko, R. S. Goody, W. Kabsch, and A. Wittinghofer. 1990. Refined crystal structure of the triphosphate conformation of H-ras p21 at 1.35 A resolution: implications for the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 92351-2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfennig, P. L., and A. M. Flower. 2001. BipA is required for growth of Escherichia coli K12 at low temperature. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi, S. Y., Y. Li, A. Szyroki, I. G. Giles, A. Moir, and C. D. O'Connor. 1995. Salmonella typhimurium responses to a bactericidal protein from human neutrophils. Mol. Microbiol. 17523-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramagopal, S., and B. D. Davis. 1974. Localization of the stringent protein of Escherichia coli on the 50S ribosomal subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71820-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raskin, D. M., N. Judson, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2007. Regulation of the stringent response is the essential function of the conserved bacterial G protein CgtA in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1044636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reva, O. N., C. Weinel, M. Weinel, K. Böhm, D. Stjepandic, J. D. Hoheisel, and B. Tümmler. 2006. Functional genomics of stress response in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. J. Bacteriol. 1884079-4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richter, D., P. Nowak, and U. Kleinert. 1975. Escherichia coli stringent factor binds to ribosomes at a site different from that of elongation factor Tu or G. Biochemistry 144414-4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson, V. L., J. Hwang, E. Fox, M. Inouye, and A. M. Stock. 2002. Domain arrangement of Der, a switch protein containing two GTPase domains. Structure 101649-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe, S., N. Hodson, G. Griffiths, and I. S. Roberts. 2000. Regulation of the Escherichia coli K5 capsule gene cluster: evidence for the roles of H-NS, BipA, and integration host factor in regulation of group 2 capsule gene clusters in pathogenic E. coli. J. Bacteriol. 1822741-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rutthard, H., A. Banerjee, and M. W. Makinen. 2001. Mg2+ is not catalytically required in the intrinsic and kirromycin-stimulated GTPase action of Thermus thermophilus EF-Tu. Biochemistry 27618728-18733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott, K., M. A. Diggle, and S. C. Clarke. 2003. TypA is a virulence regulator and is present in many pathogenic bacteria. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 60168-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spedding, G. 1990. Isolation and analysis of ribosomes from prokaryotes, eukaryotes and organelles, p. 5-8. In G. Spedding (ed.), Ribosomes and protein synthesis: a practical approach. IRL Press, New York, NY.

- 48.Sprang, S. R. 1997. G protein mechanisms: insights from structural analysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66639-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 821074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takata, R., and L. A. Isaksson. 1978. The temperature sensitive mutant 72c. II. Accumulation at high temperature of ppGpp and pppGpp in the presence of protein synthesis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 16115-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tosa, T., and L. I. Pizer. 1971. Biochemical basis for the antimetabolite action of l-serine hydroxamate. J. Bacteriol. 106972-982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wout, P., K. Pu, S. M. Sullivan, V. Reese, S. Zhou, B. Lin, and J. R. Maddock. 2004. The Escherichia coli GTPase CgtAE cofractionates with the 50S ribosomal subunit and interacts with SpoT, a ppGpp synthetase/hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 1865249-5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]