Abstract

The liver-specific microRNA miR-122 has been shown to be required for the replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the hepatoma cell line Huh7. The aim of this study was to test if HCV replication can be modulated by exogenously expressed miR-122 in human embryonic kidney epithelial cells (HEK-293). Our results demonstrate that miR-122 enhances the colony formation efficiency of the HCV replicon and increases the steady-state level of HCV RNA in HEK-293 cells. Therefore, we conclude that although miR-122 is not absolutely required, it greatly enhances HCV replication in nonhepatic cells.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs approximately 22 nucleotides (nt) in length. They are derived from cellular or viral transcripts and bind to their target mRNAs in a sequence-specific manner, resulting in either mRNA cleavage or translational repression (3, 4, 23). miRNAs have been demonstrated to play an important role in defending the hosts against virus infection in plants and invertebrates (15), but it has been argued that in mammals, this sequence-specific innate antiviral immunity has been replaced by a sequence-independent, double-stranded-RNA-triggered, interferon (IFN)-mediated innate host defense mechanism (13, 38). However, recent studies suggest that cellular miRNAs are, indeed, among the key determinants controlling virus infection in mammalian hosts, via several distinct mechanisms (5, 34). First, as observed in plants and invertebrates, cellular miRNAs can serve as restriction factors to limit infection by several types of viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (22, 47), primate foamy virus type 1 (29), and vesicular stomatitis virus (36). Second, miRNAs can be induced by antiviral cytokines such as IFN, to inhibit virus infection as part of an innate host antiviral response (37). Third, engagement of Toll-like receptors with their cognate ligands, the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (1), induces the expression of specific miRNAs that regulate signal transduction in innate immunity and inflammation responses (35, 45) and hence could indirectly modulate virus infection (44). Finally, it has been demonstrated that a liver-specific miRNA, miR-122, binds to the 5′ nontranslational region of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genomic RNA and is essential for HCV replication in human hepatoma-derived Huh7 cells (26). This observation is further supported by a recent report showing that HCV (JFH1 strain) infection of Huh7 cells requires the functional miRNA biogenesis pathway (39).

It is intriguing that unlike the typical action of miRNA, the binding of miR-122 to its target sequences in the HCV genome does not inhibit the function of the viral RNA but instead positively regulates its replication in Huh7 cells. Another puzzle is that although HCV has been considered primarily a hepatotropic virus, the subgenomic replicons derived from both HCV genotypes 1b and 2a have been demonstrated to replicate in a variety of non-hepatocyte-derived cell lines, such as HeLa (a cervical cancer epithelial cell line), HEK-293 (a human embryonic kidney epithelial cell line), and mouse embryonic fibroblasts, following introduction of the replicons into the cells by electroporation (2, 12, 14, 27, 49). However, we and others have demonstrated that these types of cells do not express detectable levels of miR-122 (10, 26), suggesting that miR-122 may not be required for HCV replication in these nonhepatic cells. It is thus unclear whether the replication of HCV in nonhepatocytes could be regulated by miR-122. To answer this question and create a cell culture system to study the molecular mechanism by which miR-122 modulates HCV replication, we established a 293-derived cell line that inducibly expressed miR-122 and examined the effects of the miRNA on the replication of subgenomic replicons derived from HCV and West Nile virus (WNV).

Establishment of a cell line that inducibly expresses miR-122.

Our previous studies demonstrated that miR-122 is derived from a noncoding polyadenylated RNA transcribed from the gene hcr. Despite the sequence diversity in the primary transcript of hcr among different species, the sequence coding for miR-122, as well as the adjacent secondary structure within the hcr RNA, is conserved among species ranging from fish to human (10). In order to inducibly express miR-122 in 293 cells, a 160-bp region of the woodchuck genomic hcr sequence surrounding miR-122 was amplified by PCR. The PCR product was cloned into plasmid vector pcDNA5/FRT/TO to yield pcDNA5/FRT/hcr that was cotransfected with plasmid pOG44 into FLP-IN T Rex cells (Invitrogen). The genome of this 293-derived cell line contains stable integrations of a single Flp recombination target (FRT) site and a gene that expresses a TET repressor. Cotransfection of such cells with an FRT site-containing plasmid (pcDNA5/FRT/hcr) that encodes an miR-122 sequence and a plasmid (pOG44) that expresses Flp IN recombinase results in site-specific integration of the miR-122-containing cDNA through the FRT site with its expression under the control of the TET-on promoter (9). Two days after transfection, cells were trypsinized and reseeded at less than 25% confluence. The miR-122 precursor cDNA-integrated cells were selected with hygromycin (250 μg/ml) and blasticidin (5 μg/ml). Two weeks later, separate colonies appeared, and the pool of such cells was expanded to generate the cell line designated 293hcr. The primary transcript of miR-122 in 293hcr cells, upon induction by tetracycline, was expected to be recognized by Drosha and processed into an approximately 70-nt hairpin precursor in the nucleus. The precursor was further processed by Dicer into 22-nt mature miR-122 in the cytoplasm (30). Tetracycline-inducible expression of miR-122 in 293hcr cells was confirmed by Northern blot assay as described previously (11). As shown in Fig. 1A, lane 2, after culturing for 3 days in medium containing tetracycline, the 160-nt primary transcript was efficiently processed into 22-nt mature miR-122. The level of miR-122 in induced 293hcr cells was similar to that in Huh7 cells but was lower than that observed in mouse liver, woodchuck liver, and primary human hepatocytes. Based on our previous results obtained from an RNase protection assay, which estimated that the steady-state level of miR-122 in Huh7 cells was approximately 16,000 copies per cell (10), we deduced that the level of miR-122 in 293hcr cells after tetracycline induction was approximately 25,000 copies per cell.

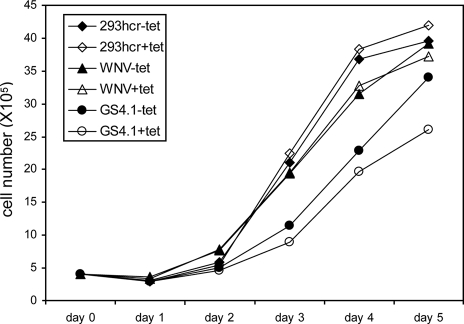

FIG. 1.

Establishment and characterization of 293 cells inducibly expressing miR-122. FLP-IN T Rex (Invitrogen) cells were cotransfected with plasmid pcDNA5/RFT/hcr that contains 160 bp of the woodchuck genomic hcr sequence encoding miR-122 and pOG44 to establish a stable cell line (293hcr) in which the transcription of miR-122 containing sequence is under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter. (A) 293hcr cells were cultured in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of 1 μg/ml tetracycline for 3 days. Total RNA was extracted, and 10 μg RNA was used to detect miR-122 by Northern blot hybridization with a [γ-32P]ATP-labeled oligonucleotide that is complementary to miR-122. Ten-microgram portions of total RNA extracted from Huh7 cells (lane 3), mouse liver (lane 4), woodchuck liver (lane 5), and primary human hepatocytes (lane 6) served as controls. The positions of the ∼70-nt miR-122 precursor (pre-miR-122) and the ∼22-nt miR-122 are indicated. (B) The function of miR-122 processed from integrated hcr transcript was validated by a reporter assay described previously (10). 293 cells and 293hcr cells cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml tetracycline and Huh7 cells were cotransfected with an internal control plasmid and either one of the two reporter plasmids. The internal control and reporter constructs expressed δAg-L and δAg-S, respectively. As indicated, in one reporter plasmid, a 22-nt miR-122 target sequence was inserted in the 3′ UTR (δAg-S-target). Cells were harvested 3 days after transfection, and total cellular protein was analyzed by Western blotting using a rabbit polyclonal antibody recognizing both forms of the δAg. The bound antibody was visualized by incubation with an infrared-dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody (LI-COR) and quantified with an Odyssey apparatus (LI-COR).

A test was made for the functionality of miR-122-induced in 293hcr cells relative to that in Huh7 cells. These cell types were cotransfected with an internal control plasmid together with either one of two reporter plasmids. While the internal control plasmid expressed the large form of the delta antigen (δAg-L) of hepatitis delta virus, the reporter plasmids expressed the small form of δAg, without (δAg-S) or with (δAg-S-target) a single miR-122 targeting site engineered into the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR) of δAg-S mRNA (10). Transfected cells were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline for 3 days, and total cellular protein was analyzed by Western blotting using a rabbit polyclonal antibody recognizing both forms of the δAg. Bound antibodies were visualized by incubation with an infrared-dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody (LI-COR), followed by quantification with LI-COR Odyssey (LI-COR). The results (Fig. 1B and C) showed that, as expected, δAg-S expression from mRNA containing a single miR-122 target site in its 3′ UTR (δAg-S-target) was reduced approximately 50% in Huh7 cells that expressed endogenous miR-122; similarly, expression of the reporter protein was reduced about 40% in miR-122-induced 293hcr cells but was not affected in HEK-293 cells when miRNA expression was not induced. Hence, these results indicate that we have established a stable cell line that inducibly expresses functional miR-122.

HCV replication was enhanced by miR-122 expression in 293 cells.

HCV contains a 9.6-kb, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome carrying a single long open reading frame that is flanked by highly invariant 5′ and 3′ UTRs. The open reading frame encodes an approximately 3,000-amino-acid-long polyprotein that is proteolytically processed into four structural and six nonstructural proteins (40). The viral nonstructural proteins induce rearrangements of endoplasmic reticulum membranes that form the locales for replication of viral RNA (16, 48). Because the viral structural proteins are not required for the replication of its RNA genome, subgenomic replicons can be constructed by replacing the structural genes with a selective marker, such as neomycin phosphotransferase II (NPT II) (see Fig. 4A). Selection of such replicon-transfected cells with G-418 results in the formation of distinct cell colonies that support persistent replication of the replicon (8, 19, 32). Technically, stable replication of HCV replicons in Huh7 cells can be established by transfection of cells with in vitro-transcribed replicon RNA, but thus far, the stable replication of HCV genotype 1b replicons in nonhepatic cells can be initiated only by transfection of cell-derived replicon RNA (49). The basis for this difference remains to be determined.

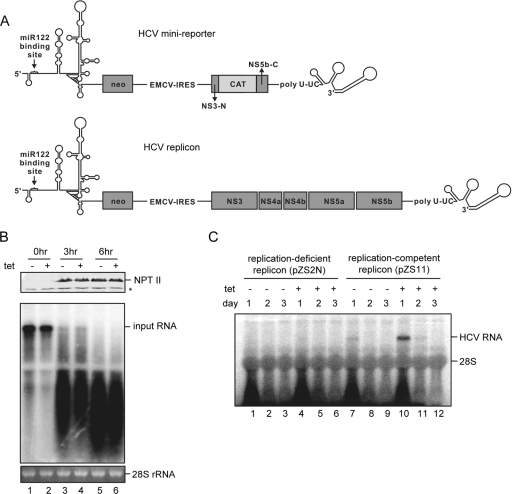

FIG. 4.

Exogenous expression of miR-122 in 293 cells does not affect HCV RNA stability and translation activity but dramatically enhances viral RNA replication. (A) Schematic representation of HCV minireporter (top) and dicistronic HCV replicon (49). The cis element in NS5B that forms a kissing loop with the 3′ UTR sequence is retained in the minireporter. (B) HCV minireporter RNA with significant deletion of the nonstructural protein coding region was electroporated into 293hcr cells without or with 2 days of prior tetracycline induction, by following the protocol described previously (19). Transfected cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and continued to be cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline for the indicated period. HCV minireporter RNA was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization with a riboprobe that is complementary to the plus strand of the NPT II coding region. 28S rRNA served as the loading control (bottom). NPT II protein in cell lysates was analyzed by Western blotting (top) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Upstate). The bound antibody was visualized by incubation with an infrared-dye-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody (LI-COR). The asterisk indicates a cross-reaction band. (C) An in vitro-transcribed replication-competent HCV replicon (pZS11) or a replication-deficient replicon with a 2-nt in-frame deletion (pZS2N) was electroporated into 293hcr cells without or with 2 days of prior tetracycline induction. Transfected cells were harvested at 1, 2, and 3 day posttransfection. Ten micrograms of total cellular RNA were resolved in 1% agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde and transferred onto Nylon membrane. The membrane was probed with a [α-32P]UTP-labeled riboprobe that is complementary to the plus strand of the HCV NS3 coding region.

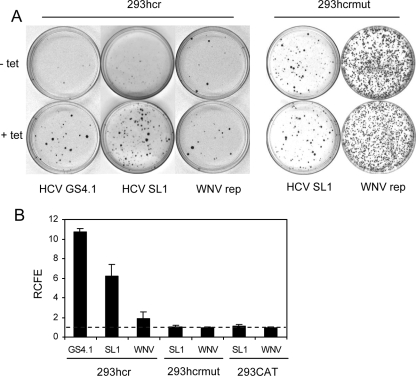

To investigate whether miR-122 modulates HCV replication in 293 cells, 293hcr cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 1 μg/ml tetracycline for 2 days and then electroporated with total cellular RNA derived from HCV subgenomic replicon-containing Huh7 (GS4.1) (21) and HeLa (SL1) (49) cells or WNV subgenomic replicon-containing 293 cells (WNVrep) (42), respectively. Electroporation was performed essentially as previously described (49). Briefly, cells were resuspended in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-F12 medium at a density of 107 cells/ml. To 200 μl of the cell suspensions in an electroporation cuvette (0.2-cm gap; BTX, San Diego, Calif.), 10 μg of total cellular RNA was added. The cells were immediately electroporated with an ECM 630 apparatus (BTX) set to 200 V and 1,000 μF. After electroporation, the cell suspension was kept for 5 min at room temperature and then diluted into complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium without or with 1 μg/ml of tetracycline and seeded in a 10-cm-diameter petri dish. After 24 h, G-418 was added to obtain a final concentration of 500 μg/ml, and medium was changed every other day. G-418-resistant colonies became visible after 2 to 3 weeks and were stained with crystal violet to facilitate colony counting. Photographs of the representative plates are presented in Fig. 2A. While more colonies were observed in HCV replicon-transfected cells in the presence of tetracycline, colony size was also greater in cells that express miR-122. To quantitatively describe the effects of miR-122 on colony formation, the relative colony formation efficiency (RCFE) was defined as the ratio of the colony number obtained with tetracycline-induced cells to that obtained with noninduced cells (24). Thus, the value of RCFE should be 1 if miR-122 does not affect HCV replication and greater than 1 if the miRNA promotes HCV replication. As summarized in Fig. 2B, while the RCFE values were approximately 1 for both HCV and WNV replicons in the cell line that inducibly expresses chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (293CAT), the RCFE was 2 for WNV replicons and 6 to 11 for HCV replicons in 293hcr cells, suggesting that miR-122 expression dramatically enhances HCV replication in 293 cells.

FIG. 2.

Cell colony formation efficiency of the HCV replicon was enhanced by exogenous expression of miR-122 in 293 cells. 293hcr, 293hcrmut, or 293CAT cells were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline for 2 days and then electroporated with total RNA extracted from HCV replicon-containing Huh7 (GS4.1) and HeLa (SL1) cells or WNV replicon-containing 293 cells (WNVrep), respectively. Transfected cells were then cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline and selected with 500 μg/ml of G-418 for 2 to 3 weeks (see the text for details). (A) Cell foci were stained with crystal violet, and representative photographs of 293hcr and 293hcrmut cells are shown. (B) The cell foci in three plates cultured in either the absence or presence of tetracycline were counted. RCFE was expressed and plotted as the ratio of the number of foci obtained from cells selected in the presence of tetracycline to that from cells cultured in the absence of the antibiotic.

As a control, we established an hcr mutant cell line (293hcrmut) in which nucleotides G, A, and U at positions 3, 4, and 6 of miR-122 (see Fig. 5A) were replaced with nucleotides C, U, and A. In order to ensure the proper processing of the mutant hcr sequence, the nucleotides base-pairing with miR-122 and maintaining the secondary structure of precursor RNA were also mutated correspondingly. Total cellular RNA derived from SL1 or WNVrep cells was electroporated into 293hcrmut cells, and selection was carried out with 500 μg/ml G-418 in the absence or presence of tetracycline. Compared with the results obtained with 293hcr cells, colony formation efficiency was generally higher in 293hcrmut cells transfected with either SL1- or WNVrep-derived RNA. This is most likely due to an unknown difference, unrelated to miRNA expression, between the two cell lines. Nevertheless, the RCFEs for both RNAs in 293hcrmut cells were approximately 1 (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting that the mutant miR-122 did not enhance the colony formation efficiency of the HCV replicon. Electroporation of GS4.1-derived cellular RNA into 293hcrmut cells did not yield any G-418-resistant colony under both tetracycline-induced and uninduced conditions (data not shown). Unlike transfection with HCV replicon RNA derived from SL1 cells, transfection of both parental 293 cells and 293hcr cells in the absence of tetracycline with HCV replicon RNA derived from GS4.1 cells usually yields no or a few colonies per 10-cm plate. Therefore, failure to obtained colonies in 293hcrmut cells transfected with GS4.1 cell-derived RNA in a small set of experiments is actually not a surprise. In fact, a lack of colony formation in 293hcrmut cells, even in the presence of tetracycline, is consistent with the conclusion that the mutant miR-122 does not enhance HCV colony formation. In addition, similar to the observation with the CAT expression cell line, transfection of parental 293 FLP-IN T Rex cells with total RNA derived from either HCV replicon- or WNV replicon-containing cells resulted in similar colony formation efficiency in the absence or presence of tetracycline (data not shown).

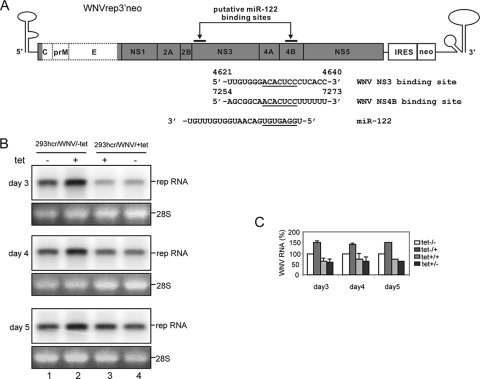

FIG. 5.

Effect of miR-122 on the replication of the WNV subgenomic replicon. (A) Schematic representation of the WNV subgenomic replicon (WNVrep3′neo) (42) and the putative miR-122 target sites and sequences, with seed and seed-match sequences underlined (numbering is according to a published WNV sequence, GenBank accession number AF404756). (B) 293hcr-derived WNV replicon-containing cell lines established in the absence (293hcr/WNV/-tet) and presence (293hcr/WNV/+tet) of tetracycline were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well. Cells were either cultured under the original conditions or switched to medium with or without tetracycline. Cells were then harvested at the indicated time points after seeding, and total cellular RNA was extracted. Ten micrograms of total RNA was analyzed by Northern blot analysis with an [α-32P]UTP-labeled riboprobe that is complementary to the plus strand of the NPT II coding region. 28S rRNA served as the loading control. (C) Levels of viral RNA were quantified with a Bio-Rad Bioimager, and the mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments were plotted.

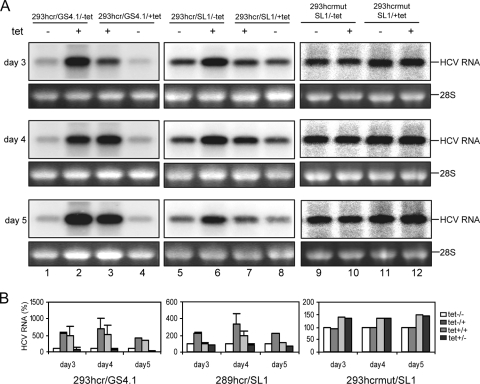

Next, we examined whether the induced expression of miR-122 altered the steady-state levels of HCV RNA in replicon-containing 293hcr cells. 293hcrmut cells were used as a control. Cell colonies were pooled from plates selected with G-418 in the absence or presence of tetracycline and expanded into cell lines under the same culture conditions. These cell lines were designated 293hcr/GS4.1/-tet, 293hcr/GS4.1/+tet, 293hcr/SL1/-tet, 293hcr/SL1/+tet, 293hcrmut/SL1/-tet, and 293hcrmut/SL1/+tet. Each cell line was cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline, and RNA was harvested at various time points for Northern blot assay. As shown in Fig. 3A, lanes 2 and 6, induction of miR-122 expression in the cell lines that were initially selected in the absence of tetracycline (293hcr/GS4.1/-tet and 293hcr/SL1/-tet) increased the levels of HCV RNA. Conversely, the levels of HCV RNA in cells that were initially selected in the presence of tetracycline (293hcr/GS4.1/+tet and 293hcr/SL1/+tet) were decreased upon culturing of cells in tetracycline-free medium (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 8). However, the levels of HCV RNA in 293hcrmut/SL1/-tet and 293hcrmut/SL1/+tet remained at steady state when cells were cultured in the presence and absence of tetracycline, respectively. Interestingly, the results obtained from both the colony formation and Northern blot assays indicated that miR-122 more profoundly affected the replication of the GS4.1-derived HCV replicons than HCV replicons derived from SL1 cells. Because the SL1 cell line was originally established by transfection of GS4.1-derived HCV replicons into HeLa cells (49), it is possible that acquired adaptation in HeLa cells rendered the replicons less dependent on miR-122.

FIG. 3.

Steady-state replication of HCV replicons was enhanced by exogenous expression of miR-122 in 293 cells. (A) 293hcr- and 293hcrmut-derived HCV replicon-containing cell lines established in the absence (293hcr/GS4.1/-tet, 293hcr/SL1/-tet and 293hcrmut/SL1/-tet) or presence (293hcr/GS4.1/+tet, 293hcr/SL1/+tet and 293hcrmut/SL1/+tet) of tetracycline were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well. Cells were either cultured under the original conditions or switched to medium with or without tetracycline. Cells were then harvested at the indicated time points after seeding, and total cellular RNA was extracted. Ten micrograms of total RNAs was analyzed by Northern blot analysis with an [α-32P]UTP-labeled riboprobe that is complementary to the plus strand of the HCV NS3 coding region. 28S rRNA served as the loading control. (B) Levels of viral RNA were quantified with a Bio-Rad Bioimager, and the mean values and standard deviations from three independent experiments were plotted.

Taken together, the results presented in this section clearly demonstrate that although miR-122 is not required for HCV replication in nonhepatic cells, exogenous expression of the miRNA, but not its mutant form, efficiently enhances the replication of HCV replicons in 293 cells. Moreover, unlike in the sophisticated and less-efficient method of modulating the level of miR-122 in Huh7 cells by antisense oligonucleotide transfection (26, 28, 41), expression of miR-122 in our 293hcr cell line is tightly controlled by a tetracycline-inducible promoter and can be turned on or off at will. Therefore, our 293hcr cell line should be a convenient cell culture system for dissecting the molecular mechanism by which miR-122 stimulates HCV replication.

How did miR-122 promote the HCV replication in 293 cells?

Concerning the molecular mechanism by which miR-122 enhances HCV replication, the most plausible possibilities include that the miRNA regulates HCV RNA translation and RNA stability or promotes viral RNA replication. To directly address the effects of miR-122 expression on HCV RNA translation and stability without influence from genome replication, a minidicistronic HCV reporter was constructed by replacing a 5-kb HCV nonstructural protein coding sequence with 0.7-kb CAT coding sequence (Fig. 4A, top). Hence, transfection of 293hcr cells with the minireporter RNA should lead to the translation of the neomycin-resistant protein NPT II under the control of authentic HCV 5′ UTR sequence but not the synthesis of any viral protein, and thus, cells should fail to form replication complexes. Furthermore, the presence of the authentic 3′ UTR of HCV in the minireporter allows the proper interaction between the 5′ and 3′ UTRs, which is critical for the translational regulation of HCV RNA (20, 43). The transfected cells were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline and harvested at various time points (Fig. 4B). The levels of input RNA and translated NPT II were assayed by Northern and Western blot assays, respectively. The results indicate that the input minireporter RNA (lanes 1 and 2) was quickly degraded in cells, and expression of exogenous miR-122 did not affect the rate of its decay. Moreover, NPT II was detectable within 3 h after transfection, and the levels of the protein were not different in 293hcr cells that were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline, indicating that expression of miR-122 did not affect HCV internal ribosome entry site-directed translation in this minireporter.

In order to examine whether miR-122 enhances viral RNA replication, 293hcr cells were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline for 2 days and then electroporated with in vitro-transcribed replication-competent (pZS11) and -deficient (pZS2N) HCV replicon RNAs (Fig. 4A, bottom) (49). Transfected cells were further cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline and harvested at days 1, 2, and 3. Total cellular RNA was extracted, and HCV replicon RNA was detected by Northern blot hybridization. The results showed that, consistent with the results obtained with the minireporter RNA (Fig. 4B), the input full-length replication-deficient pZS2N RNA was completely degraded within 1 day after culturing in either the absence or presence of tetracycline (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 and 4). However, the full-length replication-competent pZS11 RNA could still be detected 1 day after transfection (Fig. 4C, lanes 7 and 10) and then gradually disappeared at the later time points. Interestingly, the levels of full-length pZS11 RNA at 1 and 2 days after transfection in cells expressing miR-122 were more than fivefold higher than that in cells that did not express the miRNA (Fig. 4C, lanes 10 and 11 versus lanes 7 and 8). These results suggest that HCV replicon pZS11 might have initiated replication early after transfection into 293hcr cells but could not continue after 1 to 2 days posttransfection, which is similar to the phenomenon observed in wild-type HCV genotype 1b replicon (CON-1)-transfected Huh7 cells (19). While the results presented above might indicate that miR-122 could enhance the replication of HCV RNA in 293 cells initiated from in vitro-transcribed RNA, the possibility that the miRNA might stabilize replication-competent HCV replicon RNA in a complex with other viral proteins could not be ruled out.

Replication of WNV subgenomic replicon in 293hcr cells.

In the colony formation assay presented in Fig. 2, the WNV subgenomic replicon was originally designed as a negative control to demonstrate that miR-122 does not affect the replication of a closely related flavivirus in 293 cells. But to our surprise, expression of miR-122 did consistently increase the efficiency of WNV replicon colony formation twofold, indicating that the miRNA might also enhance the replication of WNV (Fig. 2). To confirm this observation, cell colonies were pooled from plates selected with G-418 in the absence or presence of tetracycline and expanded into cell lines under the same culture conditions. The cell lines, designated 293hcr/WNV/-tet and 293hcr/WNV/+tet, respectively, were cultured in the absence or presence of tetracycline and harvested at various time points (Fig. 5). Total cellular RNA was extracted, and the levels of intracellular WNV replicon RNA were assayed by Northern blot assay. Consistent with the results obtained from the colony formation assay, induction of miR-122 expression in 293hcr/WNV/-tet cells increased the levels of WNV replicon RNA approximately 50% (Fig. 5B, lane 2). In contrast, the levels of WNV replicon RNA in 293hcr/WNVrep/+tet cells were slightly decreased when cells were cultured in tetracycline-free medium.

The observed enhancement by miR-122 of WNV replication, albeit to a lesser extent than with HCV, provided another example of positive regulation of virus replication by miR-122. It is possible that, as in HCV replication, miR-122 might directly bind to its target sequence(s) in WNV genome to modulate its replication. Indeed, by sequence analysis, we have identified two potential miR-122 target sites that (i) are located in the NS3 and NS4B coding regions of the WNV genome (Fig. 5A), (ii) display perfect complementarity with the seed sequence of miR-122, and (iii) are conserved in the vast majority of WNV strains from both lineages (18, 31). While it remains to be experimentally determined if any of these putative target sequences are required for miR-122 to enhance WNV replication, it is quite obvious that unlike regular miRNAs, the potential interaction of miR-122 with its putative target sequences in WNV genome does not inhibit the viral replication.

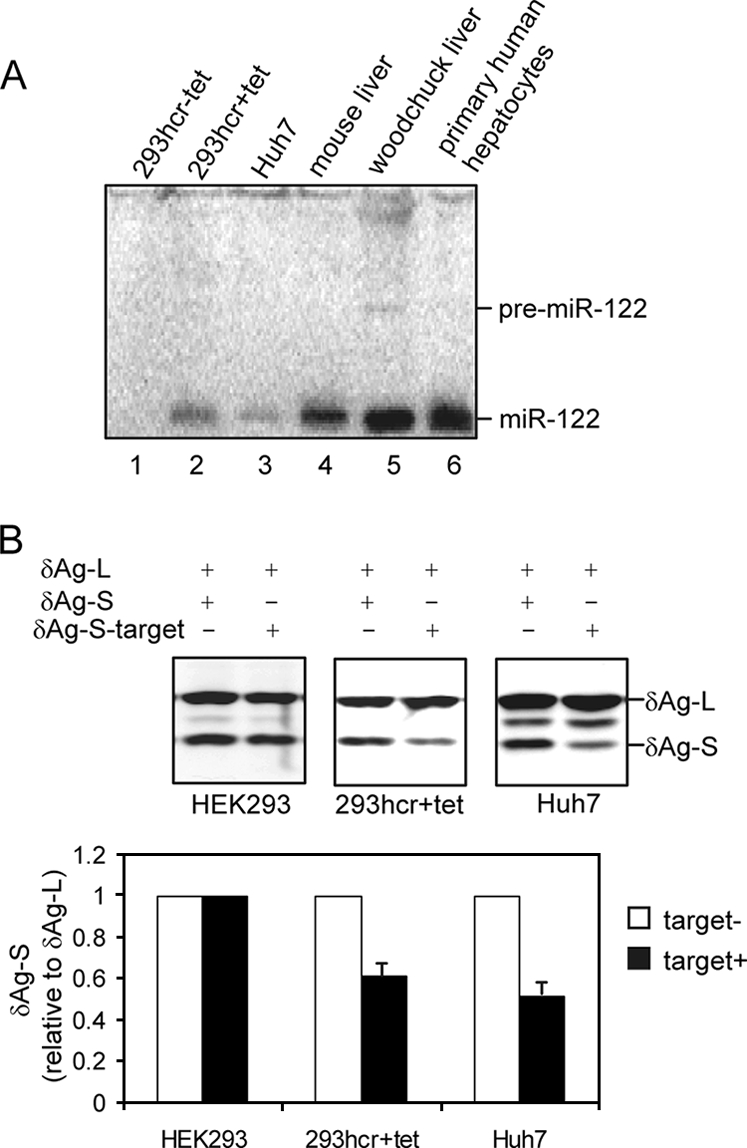

Alternatively, miR-122 may alter the expression of host cellular genes that control the cell growth and/or cholesterol biosynthesis pathway (17, 28) and indirectly modulate WNV replication (33). To evaluate the impact of exogenous miR-122 expression on the general cellular function of 293 cells, the growth kinetics of parental and replicon-containing 293hcr cells were determined. As shown in Fig. 6, the results revealed that replication of WNV replicon did not significantly affect cell growth, but the growth of HCV replicon-containing 293 cells (GS4.1) was generally slower than that of the parental 293 cells and cells that contain WNV replicon. Moreover, expression of miR-122 did not affect the growth of parental 293 and WNV replicon cells but significantly reduced the growth of HCV replicon cells, presumably due to the increased level of HCV replication, stimulated by miR-122 expression.

FIG. 6.

Effects of miR-122 expression and viral replication on cell growth. The indicated cell lines (293hcr, WNV, and HCV GS4.1) were seeded in six-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in medium with or without 1 μg/ml tetracycline. Three wells of cells from each of the cell lines cultured under either condition were trypsinized at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 days after seeding. Average cell numbers from the three wells were plotted.

In summary, this report demonstrates that as observed in Huh7 cells (26), exogenous expression of the liver-specific miRNA miR-122 does not affect the stability of viral plus-strand RNA and its translation activity but drastically enhances the accumulation of HCV replicon RNA and, to a lesser extent, WNV replicon RNA. While the previous study suggested that the direct interaction of miR-122 with its target sequences in HCV genome is required for its enhancement on HCV replication in Huh7 cells (26), it is not yet known if the observed regulatory effects of miR-122 on WNV replication require such a direct interaction or depend on the alteration of cellular gene expression. Nevertheless, the observed stimulating activity of miR-122 on HCV and WNV replication is thus far the only example of a case where the binding of a miRNA to its target RNA fails to inhibit, and actually enhances, the function of the RNA. All other miRNAs targeting viral RNA invariably inhibit the replication of viruses (22, 29, 36, 37). These observations suggest a unique property of the interaction between miR-122 and genomic RNA of viruses. Consistent with this notion, it was reported recently that while IFN induces several miRNAs that can inhibit HCV RNA replication, treatment of Huh7 cells with the same cytokine profoundly inhibits the expression of miR-122 (37). Hence, these observations seem to suggest that miR-122 is a unique miRNA that may promote the replication of many types of viruses, and therefore, down-regulation of its expression by IFN could be a general antiviral mechanism. However, due to the cell-type-specific expression of miR-122, this effect may be limited to viruses that infect hepatocytes.

One explanation for the observed enhancement of miR-122 on viral replication is that the miRNA may form a unique RNA-induced silencing complex that somehow targets viral RNA and facilitates the assembly of viral RNA replication complex and/or stimulates viral RNA replication. However, this explanation seems inconsistent with observations that miR-122 can act as a regular miRNA on mRNAs to repress their translation activity (Fig. 1B) (6, 7, 10, 25, 41). Alternatively, it has been suggested that long-range RNA-RNA interaction between HCV genomic RNA nt 22 to 40 (overlapping with the miR-122 binding site) and stem-loop VI (SLVI) in the core protein coding region may inhibit HCV internal ribosome entry site function (46). It is therefore reasonable to speculate that the binding of miR-122 on HCV RNA may interrupt this interaction and, as a consequence, facilitate HCV replication. However, while reported studies on miR-122 regulation of HCV replication were performed with full-length HCV sequence (26, 39) and thus could not formally rule out this possibility, our dicistronic HCV replicon system does not contain the stem-loop VI sequence, yet miR-122 can still regulate its replication. Further investigation of the molecular mechanism of unique interaction between miR-122 and viral RNAs should lead to a better understanding of miRNA modulation on viral replication and provide valuable information for therapeutic intervention in virus infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Cuconati for critical reading of the manuscript and Pei-Yong Shi for providing WNV subgenomic replicon.

This work was supported by an NIH grant (AI061441) and by the Hepatitis B Foundation through an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. J.M.T. was supported by grants from the NIH (AI26522 and CA06927).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S., and K. Takeda. 2004. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali, S., C. Pellerin, D. Lamarre, and G. Kukolj. 2004. Hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicons in the human embryonic kidney 293 cell line. J. Virol. 78491-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambros, V. 2004. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel, D. P. 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116281-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkhout, B., and K. T. Jeang. 2007. RISCy business: microRNAs, pathogenesis, and viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 28226641-26645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya, S. N., R. Habermacher, U. Martine, E. I. Closs, and W. Filipowicz. 2006. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell 1251111-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya, S. N., R. Habermacher, U. Martine, E. I. Closs, and W. Filipowicz. 2006. Stress-induced reversal of microRNA repression and mRNA P-body localization in human cells. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 71513-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blight, K. J., A. A. Kolykhalov, and C. M. Rice. 2000. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science 2901972-1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, J., S. O. Gudima, C. Tarn, X. Nie, and J. M. Taylor. 2005. Development of a novel system to study hepatitis delta virus genome replication. J. Virol. 798182-8188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, J., E. Nicolas, D. Marks, C. Sander, A. Lerro, M. A. Buendia, C. Xu, W. S. Mason, T. Moloshok, R. Bort, K. S. Zaret, and J. M. Taylor. 2004. miR-122, a mammalian liver-specific microRNA, is processed from hcr mRNA and may downregulate the high affinity cationic amino acid transporter CAT-1. RNA Biol. 1106-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, J., P. Provost, and J. M. Taylor. 2003. Resistance of human hepatitis delta virus RNAs to dicer activity. J. Virol. 7711910-11917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang, K. S., Z. Cai, C. Zhang, G. C. Sen, B. R. Williams, and G. Luo. 2006. Replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in mouse embryonic fibroblasts: protein kinase R (PKR)-dependent and PKR-independent mechanisms for controlling HCV RNA replication and mediating interferon activities. J. Virol. 807364-7374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen, B. R. 2006. Is RNA interference involved in intrinsic antiviral immunity in mammals? Nat. Immunol. 7563-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Date, T., T. Kato, M. Miyamoto, Z. Zhao, K. Yasui, M. Mizokami, and T. Wakita. 2004. Genotype 2a hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicon can replicate in HepG2 and IMY-N9 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27922371-22376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding, S. W., and O. Voinnet. 2007. Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell 130413-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger, D., B. Wolk, R. Gosert, L. Bianchi, H. E. Blum, D. Moradpour, and K. Bienz. 2002. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J. Virol. 765974-5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esau, C., S. Davis, S. F. Murray, X. X. Yu, S. K. Pandey, M. Pear, L. Watts, S. L. Booten, M. Graham, R. McKay, A. Subramaniam, S. Propp, B. A. Lollo, S. Freier, C. F. Bennett, S. Bhanot, and B. P. Monia. 2006. miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 387-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimson, A., K. K. Farh, W. K. Johnston, P. Garrett-Engele, L. P. Lim, and D. P. Bartel. 2007. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol. Cell 2791-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, J. T., V. V. Bichko, and C. Seeger. 2001. Effect of alpha interferon on the hepatitis C virus replicon. J. Virol. 758516-8523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo, J. T., J. A. Sohn, Q. Zhu, and C. Seeger. 2004. Mechanism of the interferon alpha response against hepatitis C virus replicons. Virology 32571-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo, J. T., Q. Zhu, and C. Seeger. 2003. Cytopathic and noncytopathic interferon responses in cells expressing hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicons. J. Virol. 7710769-10779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, J., F. Wang, E. Argyris, K. Chen, Z. Liang, H. Tian, W. Huang, K. Squires, G. Verlinghieri, and H. Zhang. 2007. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 131241-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson, R. J., and N. Standart. 2007. How do microRNAs regulate gene expression? Sci. STKE 2007re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, D., H. Guo, C. Xu, J. Chang, B. Gu, L. Wang, T. M. Block, and J. T. Guo. 2008. Identification of three interferon-inducible cellular enzymes that inhibit the replication of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 821665-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jopling, C. L., K. L. Norman, and P. Sarnow. 2006. Positive and negative modulation of viral and cellular mRNAs by liver-specific microRNA miR-122. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 71369-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jopling, C. L., M. Yi, A. M. Lancaster, S. M. Lemon, and P. Sarnow. 2005. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science 3091577-1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato, T., M. Miyamoto, A. Furusaka, T. Date, K. Yasui, J. Kato, S. Matsushima, T. Komatsu, and T. Wakita. 2003. Processing of hepatitis C virus core protein is regulated by its C-terminal sequence. J. Med. Virol. 69357-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krutzfeldt, J., N. Rajewsky, R. Braich, K. G. Rajeev, T. Tuschl, M. Manoharan, and M. Stoffel. 2005. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature 438685-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecellier, C. H., P. Dunoyer, K. Arar, J. Lehmann-Che, S. Eyquem, C. Himber, A. Saib, and O. Voinnet. 2005. A cellular microRNA mediates antiviral defense in human cells. Science 308557-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, Y., K. Jeon, J. T. Lee, S. Kim, and V. N. Kim. 2002. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 214663-4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis, B. P., C. B. Burge, and D. P. Bartel. 2005. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 12015-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohmann, V., F. Korner, J. Koch, U. Herian, L. Theilmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285110-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackenzie, J. M., A. A. Khromykh, and R. G. Parton. 2007. Cholesterol manipulation by West Nile virus perturbs the cellular immune response. Cell Host Microbe 2229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller, S., and J. L. Imler. 2007. Dicing with viruses: microRNAs as antiviral factors. Immunity 271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Connell, R. M., K. D. Taganov, M. P. Boldin, G. Cheng, and D. Baltimore. 2007. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1041604-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otsuka, M., Q. Jing, P. Georgel, L. New, J. Chen, J. Mols, Y. J. Kang, Z. Jiang, X. Du, R. Cook, S. C. Das, A. K. Pattnaik, B. Beutler, and J. Han. 2007. Hypersusceptibility to vesicular stomatitis virus infection in Dicer1-deficient mice is due to impaired miR24 and miR93 expression. Immunity 27123-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedersen, I. M., G. Cheng, S. Wieland, S. Volinia, C. M. Croce, F. V. Chisari, and M. David. 2007. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature 449919-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfeffer, S., and O. Voinnet. 2006. Viruses, microRNAs and cancer. Oncogene 256211-6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randall, G., M. Panis, J. D. Cooper, T. L. Tellinghuisen, K. E. Sukhodolets, S. Pfeffer, M. Landthaler, P. Landgraf, S. Kan, B. D. Lindenbach, M. Chien, D. B. Weir, J. J. Russo, J. Ju, M. J. Brownstein, R. Sheridan, C. Sander, M. Zavolan, T. Tuschl, and C. M. Rice. 2007. Cellular cofactors affecting hepatitis C virus infection and replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10412884-12889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reed, K. E., and C. M. Rice. 2000. Overview of hepatitis C virus genome structure, polyprotein processing, and protein properties. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 24255-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shan, Y., J. Zheng, R. W. Lambrecht, and H. L. Bonkovsky. 2007. Reciprocal effects of micro-RNA-122 on expression of heme oxygenase-1 and hepatitis C virus genes in human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 1331166-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi, P. Y., M. Tilgner, and M. K. Lo. 2002. Construction and characterization of subgenomic replicons of New York strain of West Nile virus. Virology 296219-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song, Y., P. Friebe, E. Tzima, C. Junemann, R. Bartenschlager, and M. Niepmann. 2006. The hepatitis C virus RNA 3′-untranslated region strongly enhances translation directed by the internal ribosome entry site. J. Virol. 8011579-11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taganov, K. D., M. P. Boldin, and D. Baltimore. 2007. MicroRNAs and immunity: tiny players in a big field. Immunity 26133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taganov, K. D., M. P. Boldin, K. J. Chang, and D. Baltimore. 2006. NF-κB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10312481-12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tellinghuisen, T. L., M. J. Evans, T. von Hahn, S. You, and C. M. Rice. 2007. Studying hepatitis C virus: making the best of a bad virus. J. Virol. 818853-8867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Triboulet, R., B. Mari, Y. L. Lin, C. Chable-Bessia, Y. Bennasser, K. Lebrigand, B. Cardinaud, T. Maurin, P. Barbry, V. Baillat, J. Reynes, P. Corbeau, K. T. Jeang, and M. Benkirane. 2007. Suppression of microRNA-silencing pathway by HIV-1 during virus replication. Science 3151579-1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westaway, E. G., J. M. Mackenzie, M. T. Kenney, M. K. Jones, and A. A. Khromykh. 1997. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J. Virol. 716650-6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu, Q., J. T. Guo, and C. Seeger. 2003. Replication of hepatitis C virus subgenomes in nonhepatic epithelial and mouse hepatoma cells. J. Virol. 779204-9210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]