Abstract

A new adeno-associated virus (AAV), referred to as AAV(VR-942), has been isolated as a contaminant of adenovirus strain simian virus 17. The sequence of the rep gene places it in the AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) complementation group, while the capsid is only 88% identical to that of AAV2. High-level AAV(VR-942) transduction activity requires cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans, although AAV(VR-942) lacks residues equivalent to the AAV2 R585 and R588 amino acid residues essential for mediating the interaction of AAV2 with the heparan sulfate proteoglycan receptor. Instead, AAV(VR-942) uses a distinct transduction region. This finding shows that distinct domains on different AAV isolates can be responsible for the same activities.

To date, more than 100 adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsid sequences have been cloned from a variety of sources, but little is known regarding the virus-host interactions required for entry, and even less is understood about regions on the surfaces of the particles involved in entry and transduction. A critical determinant of the ability of AAV serotype 2 (AAV2; the best-characterized AAV serotype) to transduce cells is its heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) binding activity (15). Extensive mutagenesis analyses have localized the heparan sulfate (HS) binding domain to a basic patch of amino acids, containing R585 and R588 (AAV2 VP1 numbering), located close to the top of the protrusions that surround the icosahedral threefold-symmetry axis of the capsid. Interaction with heparin is required for transduction both in vitro and in vivo, and the mutation of AAV2 R484 and R585 affects the biodistribution of AAV2 vectors in vivo (6). HS binding activity has also been observed with AAV3 (8) and AAV6 (1, 3, 16), and both can be purified using heparin agarose columns (9). However, in previous competition studies, soluble HS did not block transduction with AAV6 (3, 16). Mutagenesis studies with AAV6 have identified K531 (AAV6 VP1 numbering), located at the base of the protrusions surrounding the icosahedral threefold-symmetry axis toward the depression at the icosahedral twofold axis of symmetry, as being important for AAV6's HS binding activity. A mutation of this amino acid to the glutamic acid conserved in most other AAV serotypes blocks binding to a heparin column and results in a decrease in transduction activity to the level of that of AAV1 for HepG2 cells. However, the mechanism responsible for this change in transduction activity is unknown (16). It has now been demonstrated that AAV6 utilizes an interaction with sialic acid as a primary receptor for transduction via an undefined capsid region (14, 17).

Using PCR with AAV-specific primers, we have previously analyzed the ATCC virus collection for AAV contaminants and found a number of unique AAVs as contaminants of nonhuman primate adenovirus stocks (5, 12, 13). Using the same approach, we have analyzed other nonhuman primate adenovirus stocks and cloned the entire rep and cap coding regions of a new AAV from a simian virus 17 strain, VR-942, which was isolated from a vervet monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops). Due to its unique sequence and biologic activity, we propose to name this isolate AAV(VR-942).

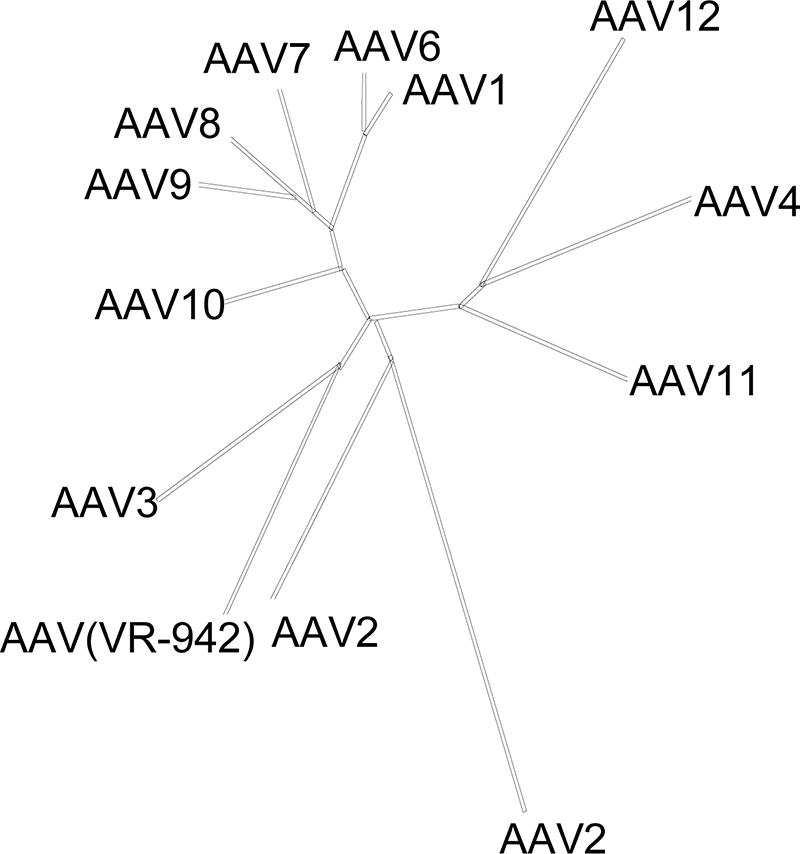

ClustalW alignments of the whole genome indicated the virus to have the highest degree of homology to AAV3 (Fig. 1). A comparison of the rep-encoded amino acid sequence of AAV(VR-942) to those of other AAVs demonstrated high-level homology to AAV4 and AAV3b sequences, with 98 and 93% identity, respectively. For VP1, the highest degrees of homology observed were those to VP1 proteins of clade C-type AAVs, such as Hu.60, Hu.25, Hu.s17, and clonal isolate AAV3b (93%) (1, 2a, 10). To test the biologic activity of AAV(VR-942), high-titer stocks of vectors based on AAV(VR-942) carrying a nucleus-localized green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression cassette flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats were produced using methods described previously (12). The level of vector transduction of COS cells was 20-fold lower for AAV(VR-942) (2 × 105 vector genomes/cell) than for AAV2 but similar to the transduction level observed previously for AAV5 (2).

FIG. 1.

Evolutionary relationships among human and nonhuman primate AAVs and AAV(VR-942). The unrooted phylogenetic tree is based on merged ClustalW alignments of partial genome sequences and shows the relatedness of different AAVs. The lengths of the branches are proportional to the evolutionary distances between isolates.

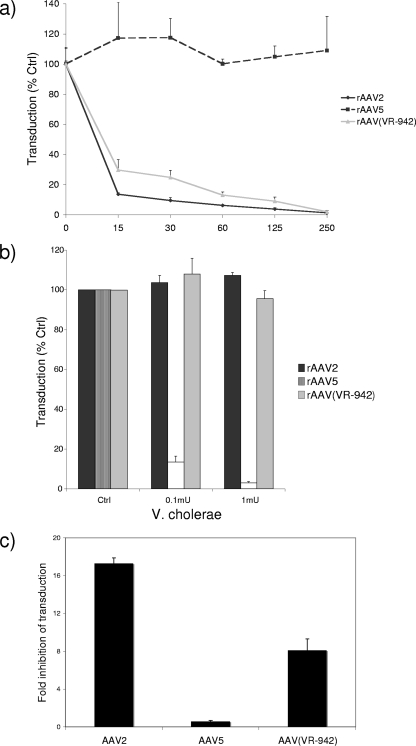

AAV2 transduction can be inhibited by heparin, an HS analog (15), whereas sialic acid-dependent AAVs can be inhibited by removing sialic acid from cell surfaces by using neuraminidase prior to transduction (4). Therefore, to determine if AAV(VR-942) used either of these two carbohydrates for cell attachment and transduction, we compared the transduction activity of AAV(VR-942) to those of AAV2 and AAV5 by using cells exposed to heparin competition, cells pretreated with neuraminidase (from Vibrio cholerae) to remove surface sialic acid, and glycan-deficient cells as described previously (9, 11). The results of all three experiments suggest that rAAV(VR-942) required HSPGs for efficient binding and transduction (Fig. 2). Recombinant AAV(VR-942) [rAAV(VR-942)] transduction of COS cells was inhibited by soluble heparin (Fig. 2a) and insensitive to neuraminidase treatment (Fig. 2b), and HSPG-deficient CHO pgsD cells were poorly transduced (Fig. 2c).

FIG. 2.

COS cell transduction by rAAV(VR-942) is inhibited by HS and is not sialic acid dependent. (a) COS cells were transduced with a preincubation mixture consisting of rAAV2-GFP, rAAV5-GFP, or rAAV(VR-942)-GFP expressing GFP, and HS was added at the concentrations indicated along the x axis (in micrograms per milliliter). Transduction was analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h postinoculation. Values are the means of results from three experiments; error bars represent standard deviations (SDs). Ctrl, control. (b) Cell surface sialic acid was removed from COS cells with increasing amounts of neuraminidase from V. cholerae prior to transduction with rAAV2-GFP, rAAV5-GFP, or rAAV(VR-942)-GFP. Twenty-four hours after transduction, cells were analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry. Values are the means of results from three experiments; error bars represent SDs. (c) CHO K1 and CHO pgsD mutants deficient in the synthesis of HSPG were transduced with either rAAV2-GFP, rAAV5-GFP, or rAAV(VR-942)-GFP expressing GFP in serial dilutions, and the degree of inhibition (n-fold) of the transduction of the CHO pgsD cells compared with the transduction of the wt CHO K1 cells was determined. Transduction was analyzed by flow cytometry 72 h postinoculation. Values are the means of results from three experiments; error bars represent SDs.

To compare the interactions of AAV(VR-942) and AAV2 with HS, we determined the binding and elution profiles of both vectors by using an HS affinity column. In agreement with the HS competition data, AAV(VR-942) was eluted earlier (200 mM) than AAV2 (500 mM), suggesting that the interaction of AAV(VR-942) with HS was slightly weaker than that of AAV2 (data not shown).

Several previous studies have identified amino acids on the capsid of AAV2 that are important for heparin binding (6, 7). Basic residues, R484, R487, K527, K532, R585, and R588 (AAV2 VP1 numbering), have been implicated in the interaction of AAV2 with heparin. These residues expose basic side chains on the capsid surface, extending from the sides of the threefold protrusions that surround the icosahedral threefold axis of symmetry to the base of this structural domain (Fig. 3a). While some of these amino acids are conserved between heparin binding and sialic acid binding AAVs, arginine 585 and 588 are unique to AAV2. These two basic amino acids are not found in AAV(VR-942), suggesting that it utilizes other residues for its heparin binding-associated transduction phenotype.

FIG. 3.

Mapping of basic residues in the HS binding region of AAV capsids. (a) Diagram of a trimer of AAV2 VP3 monomers (black, light gray, and dark gray) generated from AAV2 VP3 crystal structure coordinates (18) (Protein Data Bank accession no. 1LP3) showing the surface locations of basic residues R585 and R588 close to the top of the wall of the threefold (3f) protrusions that surround the threefold axis and basic residues R484, R487, K527, and K532 plus acidic residue E530 clustered at the base of these protrusions. The surfaces for the basic residues are colored blue, while that of E530 is colored red. A close-up view (rotated for clarity) is shown to the right. Note that residues R585 and R588 are juxtaposed close to the other residues from a threefold axis-related VP monomer and, thus, that this HS binding site is present only on assembled AAV2 capsids. (b) Diagram of a trimer of AAV(VR-942) VP3 monomers (colored as described above for AAV2) generated from a three-dimensional homologous model built using SWISS MODEL with the crystal structure of AAV2 (Protein Data Bank accession no. 1LP3) supplied as a template. The basic surface region that includes AAV(VR-942) K528, critical for HS binding activity and transduction, is shown in blue on the three monomers. A close-up view of the basic region (rotated for clarity) is shown to the right. Note that the AAV(VR-942) threefold protrusions are likely to be less pointed than those of AAV2 and that there is no basic region close to the top of the protrusions; also, the basic region at the base of the protrusion is not interrupted by an acidic region as observed in AAV2. The approximate position of the icosahedral threefold axis is indicated with an arrow in panels a and b. (c) Amino acid sequences and HS binding residues. Amino acids involved in the basic domain of AAV(VR-942) and the HS binding domain of AAV2 are indicated by #, with R585 and R588, which are unique to AAV2 and critical for its transduction activity, indicated by *. AAV(VR-942) K528 is indicated by +.

A structure-based sequence comparison of heparin binding and non-heparin binding AAVs identified a basic residue, K528, in AAV(VR-942) not found in AAV2, AAV3b, or non-heparin binding AAVs. Residue K528 forms a continuous basic patch on the capsid surface along with AAV(VR-942) R485, K525, and K530 (Fig. 3b), which are equivalent to three of the six AAV2 basic residues, R487, K527, and K532 (Fig. 3a), implicated in the heparin binding and transduction activities of AAV2. AAV(VR-942) residue K528 aligns with AAV6 K531 (Fig. 3c). However, AAV2 and most other AAV serotypes contain a glutamic acid (E) disrupting this basic region. The AAV(VR-942) basic patch is located at the base of the threefold protrusions that surround the icosahedral threefold axis, toward the depression at the icosahedral twofold axis (Fig. 3b), a region distinct from the AAV2 R585 and R588 region, which is located close to the top of the wall of the threefold protrusions surrounding the threefold axis (Fig. 3a). To understand the role of K528 of AAV(VR-942) in transduction, this residue was mutated to glutamate [generating the AAV(VR-942)-K528E mutant], and the mutant construct was compared to wild-type (wt) AAV(VR-942) with respect to the particle-to-infectivity ratio, heparin inhibition of transduction, and cell binding activity.

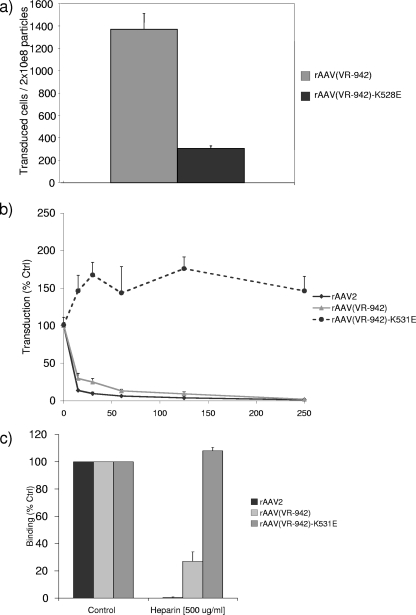

Very little difference in vector particle yields or physical properties among preparations of AAV(VR-942), AAV(VR-942)-K528E, and AAV2 was observed. However, the transduction activity of the AAV(VR-942)-K528E mutant on COS cells decreased 4.5-fold compared with that of wt AAV(VR-942), resulting in a significantly higher level of particle/transducing unit activity for the mutant (Fig. 4a). This result suggests that the K528 region is important in the biological activity of AAV(VR-942).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of wt rAAV(VR-942) and AAV(VR-942)-K528E mutant transduction activities. (a) COS cells were transduced with either wt rAAV(VR-942)-GFP or the rAAV(VR-942)-K528E-GFP mutant. Transduction was analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h after virus inoculation. Values are means of results from three experiments; error bars represent SDs. (b) rAAV(VR-942) but not rAAV(VR-942)-K528E COS cell transduction is inhibited by HS. COS cells were transduced with a preincubation mixture consisting of rAAV2-GFP, rAAV(VR-942)-GFP, or rAAV(VR-942)-K528E-GFP, and HS was added at the concentrations indicated along the x axis (in micrograms per milliliter). Transduction was analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h postinoculation. Values are the means of results from three experiments; error bars represent SDs. Ctrl, control. (c) Vector was incubated either alone or with 500 μg of HS/ml, and the mixture was added to COS cells at 4°C. After washing, virus binding was determined by quantitative PCR. The amount of vector DNA isolated from the cells treated with vector alone was then compared to that isolated from the HS-treated group. Values are means of results from three experiments; error bars represent SDs.

To determine whether the K528E mutation affected the heparin binding activity of AAV(VR-942) and its HS-dependent transduction phenotype, the HS sensitivities of AAV2, AAV(VR-942), and the AAV(VR-942)-K528E mutant were compared. In contrast to the transduction activity of wt AAV(VR-942), which was dramatically inhibited by low concentrations of HS, AAV(VR-942)-K528E transduction activity was slightly stimulated (50%) in the presence of HS (Fig. 4b). In contrast, AAV6 transduction is inhibited only at very high concentrations of HS, and an AAV6-K531E mutant also shows improved transduction (12, 16). These observations confirm the importance of the AAV(VR-942) capsid region containing K528 in the determination of transduction efficiency and suggest an alternative HS-sensitive transduction domain for AAV particles that does not include AAV2 R585 and R588.

To determine if K528 was involved in cell attachment, the binding activities of wt AAV(VR-942) and AAV(VR-942)-K528E in the presence of soluble HS were compared. Plated COS cells were chilled for 30 min at 4°C and then incubated for 30 min at 4°C with vector at a multiplicity of infection of 500 with or without heparin. After the cells were washed, the bound virus was quantified by PCR. We observed similar binding activities for the three viruses. AAV(VR-942) had 40% more binding activity than AAV2. In agreement with the mutation of the region corresponding to positions 585 to 588 in AAV2, AAV(VR-942)-K528E still retained 60% of its cell binding activity compared with that of AAV(VR-942) (6) (data not shown). However, the addition of heparin dramatically inhibited the binding of AAV2 and, to a lesser extent, that of AAV(VR-942), in agreement with data presented in Fig. 2a, suggesting that AAV(VR-942) heparin binding is weaker than that of AAV2 (Fig. 4c). AAV(VR-942)-K528E binding was not affected by heparin competition (Fig. 4c). Taken together, our findings suggest that the AAV(VR-942) K528 basic region is important as a distinct AAV surface binding domain for both cell attachment and transduction.

The identification of AAV2's HSPG binding activity has had a significant impact on our understanding of the biologic activity and the development of AAV2 as a vector for gene transfer. It has lead to a better understanding of AAV2's different transduction activities via the apical or basolateral surfaces of lung epithelia, cell tropism, and the retargeting of this vector for different tissue-directed applications. However, only the AAV2 and AAV3 isolates are reported to require HSPGs for cell attachment and transduction, and the heparin binding domain of AAV3 has not been identified. The base of the protrusions surrounding the icosahedral threefold axis of the AAV capsid, which we identified as being important for AAV(VR-942) receptor attachment and transduction, is only the second domain on the surface of any AAV particles to which this property has been mapped. As the identification of the AAV2 heparin binding domain, further analysis of the K528 region is likely to lead to improvements in gene transfer vectors and to suggest that the icosahedral threefold axis is important in cell binding by multiple isolates of AAV.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of AAV(VR-942) has been deposited in GenBank under accession number EU285562.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIDCR sequencing core facility and Danielle Mandikian for their excellent assistance.

This research was supported by funds from the Intramural Research Program of the NIH and NIDCR to J.A.C. and grants NIH R01 GM082946 and NIH P01 HL51811 to M.A.-M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen, C.-L., R. L. Jensen, B. C. Schnepp, M. J. Connell, R. Shell, T. J. Sferra, J. S. Bartlett, K. R. Clark, and P. R. Johnson. 2005. Molecular characterization of adeno-associated viruses infecting children. J. Virol. 7914781-14792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiorini, J. A., F. Kim, L. Yang, and R. M. Kotin. 1999. Cloning and characterization of adeno-associated virus type 5. J. Virol. 731309-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Gao, G., L. H. Vandenberghe, M. R. Alvira, Y. Lu, R. Calcedo, X. Zhou, and J. M. Wilson. 2004. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J. Virol. 786381-6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halbert, C. L., J. M. Allen, and A. D. Miller. 2001. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors. J. Virol. 756615-6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaludov, N., K. E. Brown, R. W. Walters, J. Zabner, and J. A. Chiorini. 2001. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J. Virol. 756884-6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katano, H., S. Afione, M. Schmidt, and J. A. Chiorini. 2004. Identification of adeno-associated virus contamination in cell and virus stocks by PCR. BioTechniques 36676-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kern, A., K. Schmidt, C. Leder, O. J. Muller, C. E. Wobus, K. Bettinger, C. W. Von der Lieth, J. A. King, and J. A. Kleinschmidt. 2003. Identification of a heparin-binding motif on adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids. J. Virol. 7711072-11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opie, S. R., K. H. Warrington, Jr., M. Agbandje-McKenna, S. Zolotukhin, and N. Muzyczka. 2003. Identification of amino acid residues in the capsid proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 that contribute to heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding. J. Virol. 776995-7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu, J., A. Handa, M. Kirby, and K. E. Brown. 2000. The interaction of heparin sulfate and adeno-associated virus 2. Virology 269137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinowitz, J. E., F. Rolling, C. Li, H. Conrath, W. Xiao, X. Xiao, and R. J. Samulski. 2002. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 76791-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutledge, E. A., C. L. Halbert, and D. W. Russell. 1998. Infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J. Virol. 72309-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt, M., and J. A. Chiorini. 2006. Gangliosides are essential for bovine adeno-associated virus entry. J. Virol. 805516-5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt, M., E. Grot, P. Cervenka, S. Wainer, C. Buck, and J. A. Chiorini. 2006. Identification and characterization of novel adeno-associated virus isolates in ATCC virus stocks. J. Virol. 805082-5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt, M., H. Katano, I. Bossis, and J. A. Chiorini. 2004. Cloning and characterization of a bovine adeno-associated virus. J. Virol. 786509-6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seiler, M. P., A. D. Miller, J. Zabner, and C. L. Halbert. 2006. Adeno-associated virus types 5 and 6 use distinct receptors for cell entry. Hum. Gene Ther. 1710-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summerford, C., and R. J. Samulski. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 721438-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu, Z., A. Asokan, J. C. Grieger, L. Govindasamy, M. Agbandje-McKenna, and R. J. Samulski. 2006. Single amino acid changes can influence titer, heparin binding, and tissue tropism in different adeno-associated virus serotypes. J. Virol. 8011393-11397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu, Z., E. Miller, M. Agbandje-McKenna, and R. J. Samulski. 2006. α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J. Virol. 809093-9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie, Q., W. Bu, S. Bhatia, J. Hare, T. Somasundaram, A. Azzi, and M. S. Chapman. 2002. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9910405-10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]