Abstract

Infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is still a major public health problem, and the events leading to hepatocyte infection are not yet fully understood. Combining confocal microscopy with biochemical analysis and studies of infection requirements using pharmacological inhibitors and small interfering RNAs, we show here that engagement of CD81 activates the Rho GTPase family members Rac, Rho, and Cdc42 and that the block of these signaling pathways drastically reduces HCV infectivity. Activation of Rho GTPases mediates actin-dependent relocalization of the HCV E2/CD81 complex to cell-cell contact areas where CD81 comes into contact with the tight-junction proteins occludin, ZO-1, and claudin-1, which was recently described as an HCV coreceptor. Finally, we show that CD81 engagement activates the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling cascade and that this pathway affects postentry events of the virus life cycle. In conclusion, we describe a range of cellular events that are manipulated by HCV to coordinate interactions with its multiple coreceptors and to establish productive infections and find that CD81 is a central regulator of these events.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV), the causal agent of hepatitis C, is a positive-strand RNA virus that belongs to the Flaviviridae family (11). The genome encodes a single polyprotein that is processed by a combination of host and viral peptidases into at least 10 different structural and nonstructural proteins. The HCV envelope is formed by the two heavily N-glycosylated type I transmembrane proteins E1 and E2, which are present on the virus as heterodimers (44, 48) anchored to a host cell-derived double-layer lipid membrane.

HCV infects mainly hepatocytes, but the precise mechanisms of early infection are largely unknown. As for other flaviviruses, it is generally accepted that HCV glycoproteins E1 and E2 play a major role in virus binding and entry into target cells (58).

Several putative HCV receptors have been identified so far. Some of these, like the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor (LDLR) (1) and other cell surface proteins involved in serum lipoprotein binding and metabolism, seem to act as relatively nonspecific attachment factors to allow virus concentration on the cell surface, as in the infected host, HCV can be associated with LDL and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL). The tetraspanin molecule CD81 (49) and the scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) (54) were both identified as putative receptors based on their interaction with recombinant soluble E2 (rE2) protein, and their role has been confirmed by means of HCV pseudotyped retroviral particles (2, 14, 29) and by the recently established in vitro infectious HCV system (HCVcc) (21, 30-32, 59). In addition, CD81 has been shown to play a role in the infection of primary human hepatocytes by serum-derived HCV (45). CD81 is an integral membrane protein that shows the structure common to all tetraspanins, with four transmembrane domains delimiting a large extracellular loop and a small extracellular loop and three short intracellular regions. Tetraspanins are molecular organizers, connecting not only extracellular and cytoplasmic elements but also laterally membrane-associated proteins and other tetraspanin family members into a specific, highly organized network, which serves as a scaffold for signaling processes (6, 27, 33). The sequence in the CD81 large extracellular loop essential for binding to HCV E2 is contained within residues 164 to 201 and constitutes the epitope for neutralizing antibodies which inhibit E2 binding to CD81 (28). The receptor binding domain of E2 encompasses polyprotein residues 384 to 661. The recombinant forms E2661 and E2715 lack the transmembrane domain, are efficiently secreted by transfected cells, and maintain the capability to interact with CD81 and SR-BI (13, 23). HCV E2 also binds to two C-type lectins, dendritic-cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) and liver/lymph node-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin (L-SIGN) (24, 37, 52), a calcium-dependent lectin expressed on liver sinusoidal endothelial cells that may favor infection by trapping the virus and facilitating the interactions with hepatocytes. In addition, recent data support a role for claudin-1 (CLDN1), a transmembrane component of the tight junctions (TJs), in a late stage of HCV entry (22), presumably after virus binding and interaction with CD81 (22). In polarized hepatocytes, CLDN-1 is mainly sequestered between adjacent hepatocytes, at TJ complexes. TJs of epithelial cells consist of narrow, belt-like intercellular contact structures in the apical region of lateral plasma membranes that wrap each cell, adjoining its neighbors. CLDN-1 is therefore expected to be mostly inaccessible to the external environment and absent from the basolateral surface, where the viral particles present in blood first interact with their other known cellular receptors. Therefore, the question that arises is how can HCV interact with all of its coreceptors in the HCV-infected liver. One hypothesis is that the initial binding of the viral particles on the cellular surface may cluster receptor proteins and activate signaling pathways that promote transfer of the bound viruses from the basolateral sinusoidal surface to the TJ region of the cell facing the bile canaliculi. A similar event has been demonstrated for the human picornavirus group B coxsackieviruses, whose binding to the decay-accelerating factor on the apical surface of Caco-2 cells triggers intracellular signals that permit virus to move to the TJ, interact with its primary receptor, the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, and enter the cell by a caveolin-dependent mechanism (15).

Although the recent characterization of a clone (JFH-1, for Japanese fulminant hepatitis 1) that is able to generate infectious particles in culture (HCVcc) has greatly increased the pace of research in the HCV field (35, 61, 63), the yields of virus obtained so far are not compatible with their use in confocal fluorescence microscopy to follow virus binding to target cells and/or in biochemical studies to define virus-induced cellular signaling. Therefore, we relied on surrogate systems (anti-CD81 monoclonal antibody [MAb] or the recombinant HCV E2 and HCV E1E2 glycoproteins) to follow the early cellular events induced by CD81 engagement; the relevance, timing, and contribution of the different signaling pathways to the establishment of productive infection were then validated by the HCVcc system and the use of specific inhibitors, pharmacological agents, and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Using the human hepatoma cell line Huh-7 as a model for infection, we found that CD81 engagement induces Rho family GTPase-dependent actin rearrangements that allow lateral movement of the virus and its delivery to areas of cell-cell contact, where the CD81/E2 complexes come into contact with claudin-1. Pharmacological treatments with latrunculin A (LatA) and other actin-destabilizing drugs blocked the CD81/E2 relocalization and dramatically reduced HCVcc infectivity. Furthermore, disruption of TJ-like structures in Huh-7 cells by calcium removal or cholesterol depletion greatly impaired HCV infectivity, indicating that TJs are instrumental in virus entry. Finally, we demonstrated that CD81 engagement triggers the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway that appears to be involved in postentry events. This study underlines the fact that CD81 is not a mere attachment factor for HCV but actively promotes infection by triggering signaling cascades which are important in both entry and more downstream events in the virus life cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.

The antibodies used were an anti-CD81 MAb (JS-81; BD Pharmingen) that neutralizes E2 binding to CD81, anti-β1 integrin antibody M-106 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-CD9 antibody M-L13 (BD Pharmingen), anti-HCV core antibody 3G1-1 (Novartis Vaccine, CA), an anti-SR-BI antibody (AffinityBioReagents), goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G F(ab)2 fragments (GαM; Sigma), and anti-HCV E2 MAb 291, which recognizes E2 bound to target cells. The rabbit polyclonal anti-claudin-1, anti-ZO-1, and anti-occludin antibodies were from Zymed Laboratories; the anti-p42/p44 (Erk1/Erk2) and anti-phospho p42/p44 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology; the anti-c-Jun and anti-phospho-c-Jun antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; the anti-Rac (23A8), anti-Rho-A, and anti-Cdc42 antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology; and the anti-actin MAb (C4) was from Chemicon International. The secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor dyes and To-Pro-3 iodide were from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes.

Recombinant purified HCV E1E2193-746 and HCV E2384-715 from genotype 1a were obtained as previously described (26, 57); the exoenzyme C3 transferease from Clostridium botulinum (5 μg/ml) was from Cytoskeleton; jasplakinolide (0.5 μM) was from Molecular Probes; LatA (1 μM), cytochalasin D (5 μM), wortmannin (1 μM), Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (100 μM), and nocodazole (1 μM) were from Calbiochem; nystatin (12.5 μg/ml), progesterone (10 μg/ml), and MβCD (1 mM) were from Sigma; and U0126 (25 μM) was from Upstate.

Production of Abelson murine leukemia virus pseudoparticles (MLVpp) and vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) pseudoparticles (VSVpp).

Lentiviral vector stocks were produced as previously described (10). Briefly, 293T cells were transiently transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation with the reporter plasmid pCCL.sin.PPT.hPGK-GFP, the packaging pMDLg/pRRE plasmid, the pRSV-Rev plasmid, and the pMD2.VSVG or SV-A-MLV-env plasmid. Supernatants were harvested at 48 h posttransfection, filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, and used to infect Huh-7 cells. Infected cells were defined through green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression as measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Production of HCVcc.

To generate genomic HCV RNA, the plasmid pUC/JFH-1, containing the full-length JFH-1 genome (GenBank accession number AB047639), was linearized at the 3′ end of the HCV cDNA, treated with mung bean nuclease, and used as a template for in vitro transcription with the MEGAscript kit from Ambion. S6.1 cells were then electroporated as previously described (36). Cell culture supernatants were harvested at different times posttransfection, cleared by low-speed centrifugation, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was determined by eight replicates of 10-fold serial dilutions according to the Spearman and Kaerber fit.

Cell culture.

HCVcc production was obtained in S6.1 cells, a subclone of Huh 5-2 cells that has cleared the replicon (64). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal calf serum. For relocalization experiments, Huh-7 cells were plated on glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (BD) at a density of 50,000 cells/coverslip in 24-well plates. Cells were grown for a minimum of 48 h before experiments to obtain confluent monolayers.

HCVcc infection.

Huh-7 cells grown in 96-well plates (10,000/well) were infected with HCVcc or control viruses at 100 TCID50/well. For experiments with inhibitors, cells were preincubated with inhibitors for 1 h at 37°C and exposed to the virus at 4°C for 1 h in the continuous presence of the drugs. Unbound virus was then washed away, and cells were shifted to 37°C with fresh medium containing or not containing the drug for the indicated period. In some experiments, drugs were added at different times postinfection and maintained in culture for a total of 3 h thereafter. At 72 h postinfection, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and processed for immunofluorescent detection of the HCV core protein with anti-core MAb 3G1-1. Infection was determined by enumerating core-positive cells or foci under a fluorescence microscope.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Huh-7 cell monolayers were exposed to anti-CD81 MAb JS-81 (10 μg/ml) or to recombinant HCV E2 or HCV E1E2 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-E2 MAb 291 (10 μg/ml) for the indicated time at 37°C. Cells were then fixed in 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 before staining. Cells were then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed, incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and mounted. Image acquisition and processing information: (i) make and model of microscope, Nikon Eclipse TE2000, Radiance 2100 Confocal System (Bio-Rad); (ii) magnification and type of objective lens, 63× Plan Apochromate; (iii) imaging medium, Prolong Antifade kit (Invitrogen); (iv) fluorochromes, Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 568, and Alexa Fluor 647; (v) acquisition software, Lasersharp 2000 (Zeiss). z stacks were generated in 0.2-μm step increments, and three-dimensional reconstructions were performed with Volocity (Improvision Inc.). Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

CD81 cross-linking and immunoblot analyses.

Huh-7 cells were incubated with anti-CD81 MAb JS-81 (10 μg/ml), 10 μg/ml rE2 plus anti-E2 MAb 291 (10 μg/ml), or an isotype control (10 μg/ml) for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were then stimulated at 37°C by cross-linking with 10 μg/ml anti-mouse immunoglobulin G F(ab)2 fragments for the indicated time and lysed. After removal of insoluble materials by centrifugation, cell extracts were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with specific antibodies plus horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The ECL reagent (Amersham Biosciences) was used as the substrate for detection.

Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 activation assay.

Assays were performed with reagents from Upstate Biotechnology according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were lysed in magnesium lysis buffer (Upstate Biotechnology) and then incubated for 1 h at 4°C with PAK-1 PBD-agarose to precipitate GTP-bound Rac and Cdc42 or with rhotekin Rho binding domain-glutathione S-transferase to precipitate GTP-bound Rho. Samples were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted.

siRNAs and transfections.

Double-stranded siRNAs targeted against human Rac (Upstate Biotechnology) and Cdc42 (target, 5′-CTATGCAGTCACAGTTATG-3′) were transfected into Huh-7 cells with the HiPerFect transfection reagent kit (Qiagen). At 48 h posttransfection, cells were monitored for gene silencing by immunoblot assays and then used for HCVcc infection or for confocal microscopy. The siRNA sequence targeting human CD81 spans nucleotides 138 to 156 (target, 5′-ATCTGGAGCTGGGAGACAA-3′), was chemically synthesized by Qiagen, and was transfected into Huh-7 cells as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). A two-tailed Student t test was performed to analyze variance.

RESULTS

Engagement of CD81 induces its relocalization to areas of cell-cell contact, where it colocalizes with claudin-1 and ZO-1.

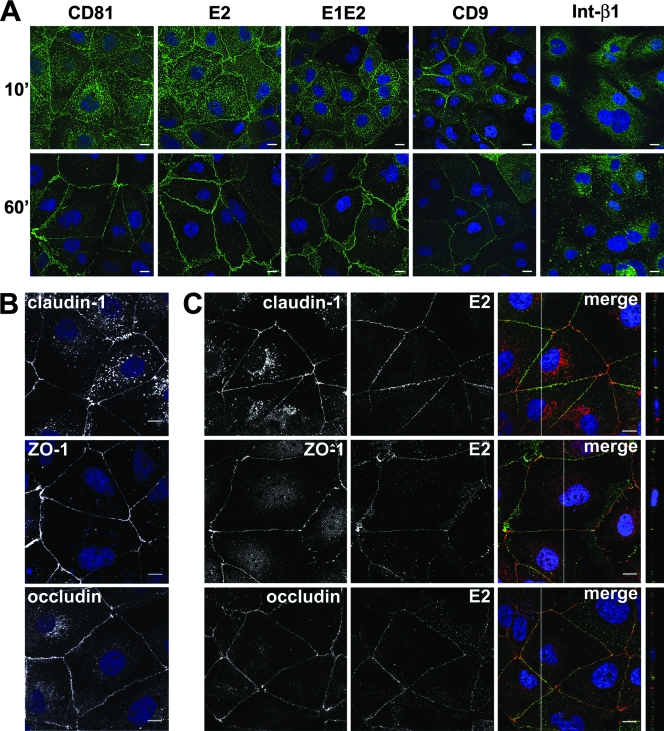

For biochemical and confocal microscopy studies, a quantitative engagement of receptors by excess ligand is required. We therefore used either anti-CD81 MAb or the recombinant viral envelope protein E2 or E1E2 to determine whether engagement of CD81 could induce lateral migration of the virus-receptor complex to areas of cell-cell contact, where the coreceptor molecule claudin-1 accumulates. For this purpose, Huh-7 cells were grown on lysine-coated glass coverslips for at least 48 h to obtain a confluent monolayer and then stimulated with anti-CD81 MAb or recombinant HCV E1E2 or HCV E2 at 37°C. Then, at different time points, cells were fixed and stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies. While CD81 and cell-bound HCV E2 and HCV E1E2 were detected in a diffuse pattern along the whole cellular surface at 10 min, after 60 min of engagement at 37°C, they concentrated at areas of cell-cell contact (Fig. 1A; see Fig.S1 in the supplemental material). Similar results were obtained whether or not cross-linking by an anti-E2 MAb was performed (not shown). This phenomenon was not observed when cells were exposed to anti-β1-integrin antibody, which induced the formation of clusters on the cell surface (Fig. 1A). When CD9, a different member of the tetraspanin family that has been shown to associate with CD81, was engaged by a MAb, a similar relocalization of the engaged molecules was observed, indicating that lateral movements on the plasma membrane may be a common characteristics of tetraspanins.

FIG. 1.

Upon engagement, CD81 relocalizes to areas of cell-cell contact. (A) Huh-7 monolayers grown on polylysine-coated slides were incubated with an anti-CD81 MAb (JS-81), recombinant HCV E1E2 or HCV E2 glycoprotein plus anti-E2 MAb 291, the anti-β1 integrin MAb, or the anti-CD9 MAb for the indicated time (minutes) at 37°C. Cells were then fixed and stained with an anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were visualized with To-Pro3 iodide (blue). The samples were then examined by confocal microscopy. The images provided represent one z section from deconvolved z stack images. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Nonstimulated Huh-7 monolayers were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against occludin, claudin-1, and ZO-1. (C) rE2 and anti-E2 MAb 291 were allowed to bind to Huh-7 cells at 37°C for 60 min. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against occludin, claudin-1, and ZO-1, followed by a rabbit-Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody (red) and an anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green), as indicated. Areas of colocalization appear yellow. In merged confocal images, the white line indicates the position of the y-z cross section. The images provided are one z section from deconvolved z stack images. Bars, 10 μm.

After 60 min of engagement at 37°C, we detected a partial colocalization of cell-bound HCV E2 (Fig. 1C), HCV E1E2, and CD81 (not shown) with the TJ proteins ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-1. In our cells, claudin-1 was partly intracellular and partly enriched at cell-cell contacts, while ZO-1 and occludin showed exclusively the polygonal web distribution characteristic of TJ proteins. In any case, the cellular distribution of these three proteins was not influenced or modified by CD81 engagement (Fig. 1B and C). These results strongly suggest that upon binding to the CD81 coreceptor, HCV bound to the surface of hepatocytes can be transported laterally to areas of cell-cell contact, where it comes into contact with the coreceptor claudin-1.

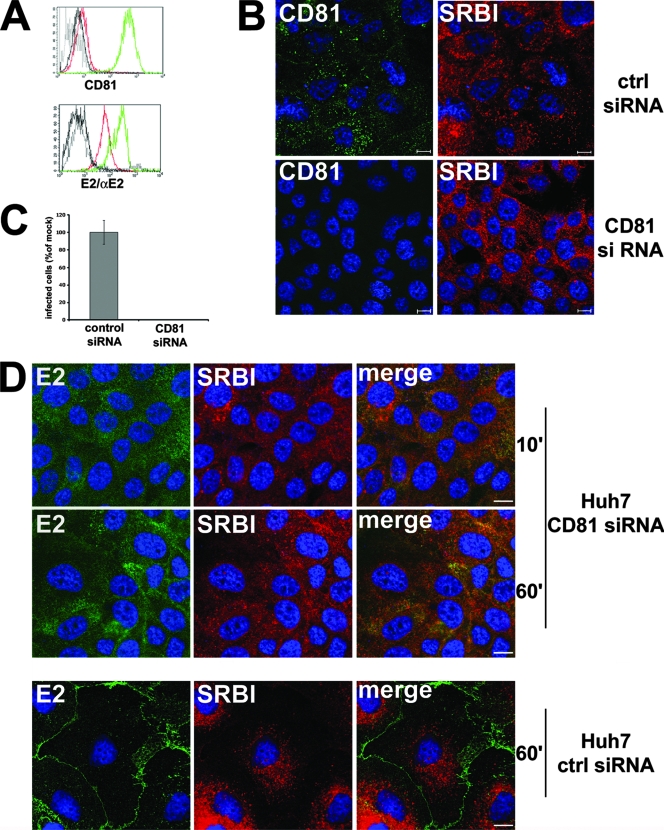

Relocalization of the HCV glycoproteins to the TJ is mediated solely by CD81.

To evaluate the contribution of CD81 to the relocalization of recombinant, cell-bound HCV glycoproteins, we transfected Huh-7 cells with control or CD81-specific siRNA. Transfection of CD81 siRNA caused a marked downregulation of CD81 surface expression (Fig. 2A and B) and greatly reduced the amount of E2 bound but did not abolish E2 binding (control siRNA mean fluorescence intensity, 242; CD81 siRNA mean fluorescence intensity, 62), as rE2 could still bind to SR-BI, whose expression was not affected by CD81 siRNA (Fig. 2B). However, in cells exposed to CD81 siRNA, bound E2 did not significantly relocalize to the TJs, even upon prolonged exposure at 37°C (Fig. 2D). Since a basal level of E2 accumulation is found at cell boundaries in these cells as in wild-type cells, we cannot formally exclude the involvement of an E2 receptor other than CD81 in this process. Importantly, downregulation of CD81 drastically reduced the susceptibility of Huh-7 cells to HCVcc infection, compared to cells exposed to control siRNA (Fig. 2C). From these data, we can speculate that expression of CD81 on the cellular surface mediates both the binding and the delivery of recombinant HCV glycoproteins, and possibly the virus, to the TJs and is then indispensable for subsequent infection.

FIG. 2.

Silencing of CD81 reduces HCV E2 binding to Huh-7 cells, abolishes its relocalization, and greatly impairs susceptibility to HCV infection. (A) Flow cytometry analysis. Huh-7 cells transfected with control (green line) or CD81 (red line) siRNA were incubated with anti-CD81 MAb or with E2 glycoprotein plus anti-E2 MAb and then treated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugate secondary antibody. Black lines indicate the isotype control. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis. Huh-7 cells transfected with control (ctrl) or CD81 siRNA were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with an anti-CD81 MAb and an anti-SR-BI rabbit polyclonal antibody. The images provided are one z section from deconvolved z stack images. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Huh-7 cells transfected with control or CD81 siRNA were infected with 100 TCID50 HCVcc. Infected cells were visualized 72 h postinfection by staining with anti-HCV core MAb 3G1-1 plus an anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody and counted under a fluorescence microscope. Infectivity is expressed relative to the values obtained for the control as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates in three independent experiments (** P < 0.001). (D) Huh-7 cells transfected with CD81 or control siRNA were incubated with sE2 plus anti-E2 MAb 291 at 37°C for the indicated time (minutes), fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-SR-BI rabbit polyclonal antibody, followed by an anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody (red) and an anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green). The images provided represent merged z stacks. Bars, 10 μm.

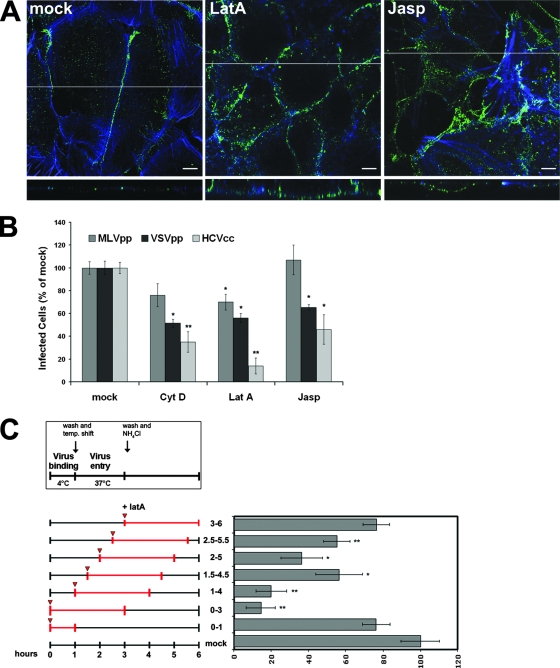

The actin cytoskeleton is required for virus movement to the TJ and for establishing productive infection.

When Huh-7 cells were exposed to LatA, an inhibitor of F-actin polymerization, the relocalization of the CD81/E2 complexes was blocked, indicating that remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton is required for CD81 relocalization (Fig. 3A; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). To evaluate the physiological relevance of this inhibition, we analyzed the effects of pharmacological treatments with actin-destabilizing agents on the JFH-1 infection of Huh-7 cells. We exposed Huh-7 cell monolayers to JFH-1 viral particles for 1 h at 4°C in the presence or absence of the drug, and then the medium containing the unbound virus was washed away and replaced with fresh medium supplemented or not supplemented with the compound. After 2 h at 37°C, the drugs were removed and the cells were treated with NH4Cl to block the entry of any virus that had bound to the cellular surface but not gotten inside. Treatments with LatA, cytochalasin D, or jasplakinolide dramatically reduced JFH-1 infectivity, while they had only a minor effect on the infectivity of MLVpp, a control for viruses that fuse at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3B; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The inhibition of entry also observed for VSVpp, a control for viruses that require delivery to early endosomes, can be explained by the fact that an intact actin cytoskeleton is also required for more downstream events, such as clathrin-mediated virus endocytosis (46).

FIG. 3.

An intact actin cytoskeleton is required for CD81 relocalization to the TJ and for HCVcc infection. (A) Huh-7 cells pretreated for 60 min with LatA (1 μM) or jasplakinolide (Jasp; 500 nM) or mock treated (dimethyl sulfoxide) were allowed to bind rE2 plus anti-E2 MAb 291 at 37°C for 60 min in the continuous presence of compounds. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with an anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green) and phalloidin (blue). The images shown here represent one z section from deconvolved z stack images. The white line indicates the position of the x-z cross section. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Huh-7 cells were mock treated or incubated for 1 h with medium containing 1 μM LatA, 5 μM cytochalasin D (Cyt D), or 500 nM Jasp and infected with different viruses for 3 h in the presence or absence of the drugs. After washing, cells were left for 72 h in medium alone and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-HCV core MAb 3G1-1. Positive cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope. Infectivity is expressed relative to the values obtained in the absence of the drugs as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates in three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). As a control, infections with retroviral pseudoparticles bearing VSV-G or Abelson murine leukemia virus envelope proteins were performed under the same conditions and the level of infectivity was determined by FACS analysis of GFP expression. (C) Kinetics of LatA inhibitory activity. Virus was allowed to bind to cells for 1 h at 4°C in the absence or presence of LatA (1 μM). Subsequently, cells were washed and shifted to 37°C to allow entry. As indicated in the scheme, LatA was added directly or 30, 60, 90, or 120 min after the temperature (temp.) shift and left for 3 h thereafter. NH4Cl was added 2 h after warming to block further infection. Efficiency of infection was determined 72 h later as the percentage of HCV core-positive cells relative to that of control infections performed in the same way but always without the drug. Mean values and SD of four replicates in three independent experiments are given (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001).

To better characterize the mode of inhibition by the drug, we investigated its inhibitory capacity when administrated at different intervals during the early phase of infection (Fig. 3C). Huh-7 cells were incubated with JFH-1 for 1 h at 4°C in the presence or absence of LatA. Under this condition, virus attaches to the cells but does not efficiently enter, allowing a synchronous infection when the inoculum is removed and the cells are shifted to 37°C. LatA was added either directly or 30, 60, 90, or 120 min after the temperature shift and left on the cells for 3 h, as indicated in the scheme of Fig. 3C. Addition of NH4Cl to cells 2 h after warming blocked acidic activation of additional incoming viruses (for the window in which ammonium chloride is effective in blocking infection, see Fig.S3 in the supplemental material). Under these conditions, we found that the drug had no effect on the virus binding to the cells when added to the cells solely during the incubation at 4°C and that infection was blocked with the highest efficiency when LatA was present in the first 30 min following the temperature shift to 37°C. JFH-1 infectivity was restored to 60% of the control when the drug was added 90 min after virus attachment and completely restored for drug addition at 3 h postattachment. This kinetics of inhibition suggests that an intact cytoskeleton is required for an early stage of infection (relocalization and/or entry).

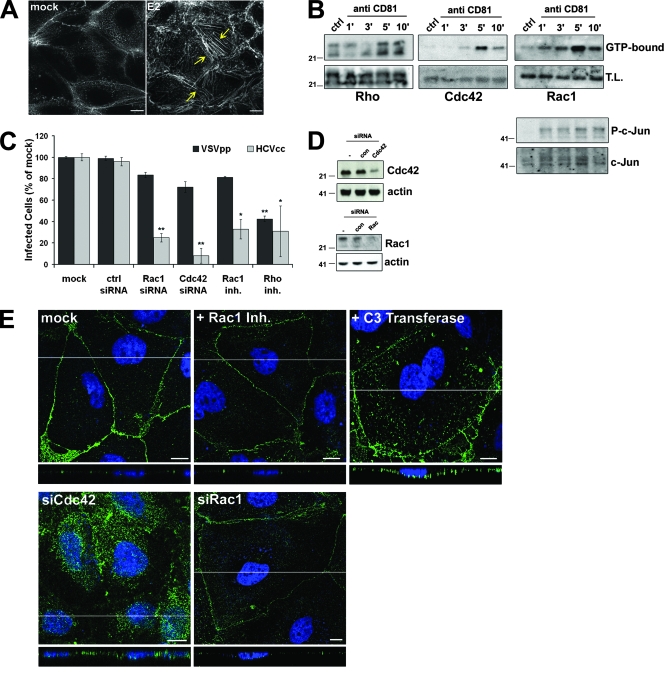

CD81 triggers Rho GTPase-mediated actin rearrangements.

We have previously shown that CD81 engagement induces actin rearrangements in different cell types of the immune system and that these modifications modulate the functionality of these cells (17, 18, 60). CD81 binding by an anti-CD81 MAb (not shown) or by recombinant E2 induced an extensive rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton also in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 4A). Moreover, CD81 engagement increased the level of activated (GTP bound) Rac1, RhoA, and Cdc42, three Rho family GTPase members, as demonstrated by affinity purification (Fig. 4B). Rho GTPases are molecular switches that cycle between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state. This cycling is regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors, GTPase-activating proteins, and guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (4, 20, 53). In the active conformation, each Rho GTPase binds to a subset of downstream effectors and regulates different aspects of cytoskeletal dynamics (7, 25). Upon CD81 engagement, we also observed the activation of one of these downstream effector molecules, c-Jun, as indicated by its phosphorylation on serine (Fig. 4B). Knockdown of Rac1 and Cdc42 with specific siRNAs (Fig. 4C and D) reduced JFH-1 infection by 65% ± 5% and 92% ± 8%, respectively, and a significant reduction in infectivity was also seen in cells treated with the Rac1-specific inhibitor NSC23766 or with the exoenzyme C3 transferase from Clostridium botulinum, a selective Rho inhibitor (Fig. 4C). The exoenzyme C3 transferase also blocked the accumulation of the CD81/E2 complexes at areas of cell-cell contact (Fig. 4E), while NSC23766- and Rac1-specific siRNAs had no effect on CD81 relocalization. Inhibition of bound HCV E2 relocalization was also seen in cells transfected with Cdc42 siRNA (Fig. 4E). In summary, Rho GTPases activated in response to CD81 play an essential role in HCVcc infectivity. Our data suggest that both Cdc42 and Rho are required for virus movement to the TJ, while Rac1 is dispensable for this process. As Rac1 inactivation by a specific drug or siRNA results in a great reduction in HCVcc infectivity, we speculate that Rac1 is required for other actin-dependent processes, e.g., virus endocytosis.

FIG. 4.

CD81 triggers the Rho family GTPases Rho, Rac, and Cdc42. (A) Phalloidin staining of the actin cytoskeleton in Huh-7 cells mock treated or exposed to rE2 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-E2 MAb 291 (10 μg/ml) for 60 min at 37°C. Yellow arrows indicate actin stress fibers. (B) Huh-7 cells were incubated with an anti-CD81 MAb or an isotype control (ctrl) and then cross-linked with GαM for the indicated times (minutes) at 37°C (5 min for the isotype control). After lysis, GTP-bound Rho, Cdc42, or Rac was affinity precipitated and immunoblotted with specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Whole-cell lysate (T.L.) was also blotted to evaluate total proteins and the level of phosho-c-Jun (P-c-Jun) and total c-Jun. (C) Mock-treated Huh-7 cells or cells treated with Rac1 inhibitor (inh.) NSC23766 or C3 exoenzyme or transfected with Cdc42, Rac, or control siRNA were infected with 100 TCID50 HCVcc for 3 h in the presence or absence of the drugs. Cells were then left in medium alone for an additional 72 h before fixation and staining with anti-HCV core MAb 3G1-1. Positive cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope. Infectivity is expressed relative to the values obtained in the absence of the drugs as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). As a control, infections with retroviral pseudoparticles bearing VSV-G were performed under the same conditions and the level of infectivity was determined by FACS analysis of GFP expression. (D) Lysates of Huh-7 cells transfected with control (con), Cdc42, and Rac siRNAs or not transfected were immunoblotted with Cdc42-, Rac-, and actin-specific antibodies. (E) Huh-7 cells transfected with Cdc42 or Rac1 siRNA or treated with the Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 or the C3 exoenzyme or mock treated were exposed to E2 plus anti-E2 for 1 h at 37°C and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-mouse-Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (green). Images shown here represent one z section from deconvolved z stack images. The white line indicates the position of the x-z cross section. Nuclei were stained in blue with To-Pro3 iodide. Bars, 10 μm. The values to the left of the gels in panels B and D are molecular sizes in kilodaltons.

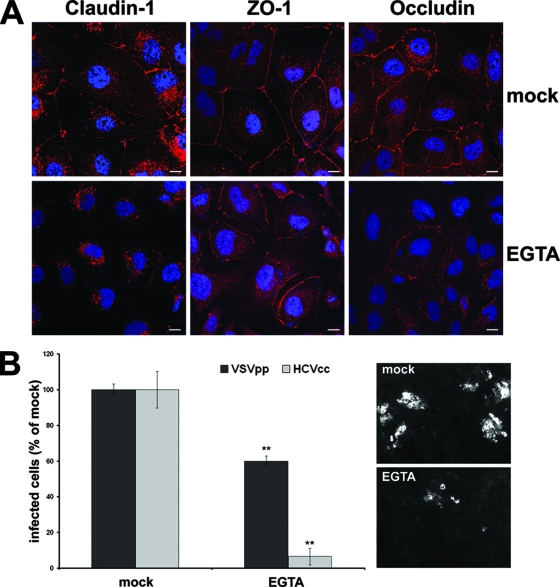

Disruption of TJs reduces HCV entry.

If HCV has to access TJ-sequestered claudin-1 to enter target cells, TJ disruption should impair viral entry. To test this hypothesis, we depolarized Huh-7 cells by calcium withdrawal and assessed their ability to support HCVcc infection. After virus inoculation at 37°C for 2 h, cells were refed medium supplemented with calcium to allow TJ formation. Depletion of calcium disrupted claudin-1, ZO-1, and occludin membrane expression and caused them to accumulate intracellularly (Fig. 5A). As a result, the infectivity of HCVcc decreased sharply, to around 10% of the control while infection of VSVpp was only partially affected (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Disruption of TJs inhibits viral entry. (A) Confluent Huh-7 cells were mock treated or exposed to 2.5 mM EGTA for 3 h, followed by fixation, permeabilization, and immunofluorescent staining of endogenous claudin-1, ZO-1, and occludin. (B) Untreated Huh-7 cells or cells treated for 3 h with 2.5 mM EGTA were infected with 100 TCID50 HCVcc for 2 h in the presence or absence of EGTA. Cells were then washed and left in medium alone for an additional 72 h before fixation and staining with the anti-HCV core MAb 3G1-1. Positive cells or foci were counted under a fluorescence microscope. Infectivity is expressed relative to the values obtained in the absence of the drugs as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates (**, P < 0.001). As a control, infection with retroviral pseudoparticles bearing the VSV-G envelope protein was performed under the same conditions and the level of infectivity was determined by FACS analysis of GFP expression.

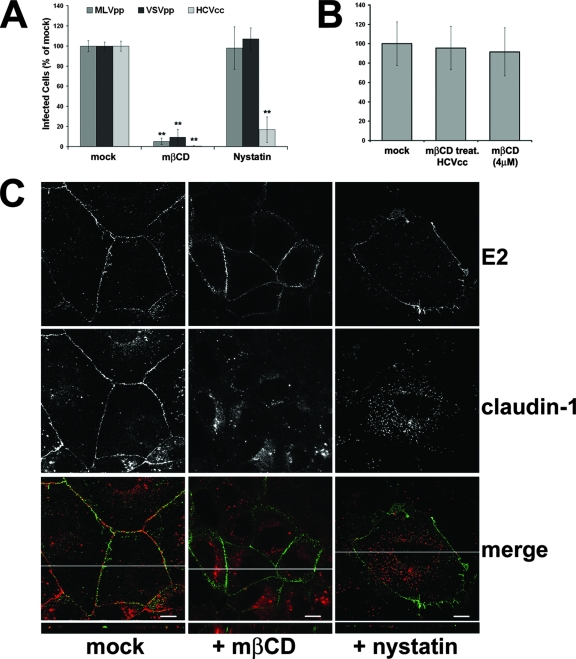

Cholesterol requirement for HCV infection.

It is now well established that tetraspanins associate extensively with one another and with other cellular proteins to form membrane microdomains that are enriched in palmitate, cholesterol, and gangliosides (27). So we tested the effects of nystatin and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), two cholesterol-depleting drugs, on HCVcc infection. The presence of the drugs during the phases of virus binding and infection led to a strong inhibition of JFH1 infectivity (Fig. 6A); MβCD had a very broad effect, dramatically reducing also VSVpp and MLVpp infectivity, while the effects of nystatin were limited to HCV (Fig. 6A). The observed reduction in infectivity depended on the effect of MβCD on target cells, as pretreatment of HCVcc particles with a 1 mM concentration of the drug did not have any consequence on viral infectivity (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Effects of cholesterol-depleting drugs. (A) Huh-7 cells were mock treated or incubated for 1 h with medium containing MβCD or nystatin and infected with different viruses for 3 h in the presence or absence of the drugs. Cells were then washed and left for 72 h in the presence of medium alone. Infectivity was determined by counting HCV core-positive cells under a fluorescence microscope. Infectivity is expressed relative to the values obtained in the absence of the drugs as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates in three different experiments (**, P < 0.001). As a control, infections with retroviral pseudoparticles bearing VSV-G or Abelson murine leukemia virus envelope proteins were performed as described for Fig. 3B. (B) HCVcc particles were pretreated for 1 h at 4°C with 1 mM MβCD or mock treated; virus was then diluted in fresh medium to reach an MβCD concentration of 4 μM when viral particles were put on cells. As a control, an aliquot of mock-treated HCV particles was diluted to 4 μM MβCD just before infection. Infectivity was determined by counting HCV core-positive cells under a fluorescence microscope and is expressed relative to the values obtained in the absence of the drugs as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates in three independent experiments. (C) Huh-7 cells treated with MβCD or nystatin or mock treated were exposed to rE2 plus anti-E2 for 1 h at 37°C and then stained for E2 (green) and claudin-1 (red). In merged confocal images, areas of colocalization appear yellow. The images provided represent one z section from deconvolved z stack images. The white line in each merged image indicates the position of the x-z cross section. Bars, 10 μm.

At the concentration used in these experiments, both MβCD and nystatin treatments did not inhibit the E2-driven CD81 relocalization to areas of cell-cell contact (Fig. 6C), indicating that the cellular functional effects determined by CD81 engagement were not compromised. Interestingly, the same treatment resulted in the displacement of claudin-1 from TJ regions (Fig. 6C). Based on this set of data, it is tempting to speculate that the observed block in virus infectivity was due to the destruction of the TJ structure as a consequence of cholesterol depletion.

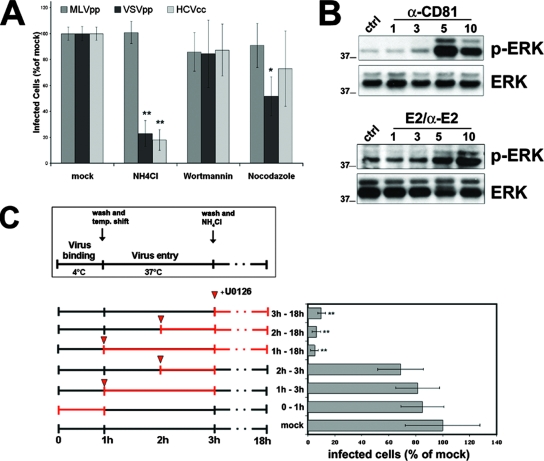

CD81-induced activation of the ERK pathway is required for HCV infection.

To further understand the route of infection followed by HCV and its dependence on specific cellular signals, we investigated the effects of different drugs on HCVcc entry and infection. In agreement with data published by other groups (32, 42, 59), we reconfirmed the requirement of a low endosomal pH for the entry of the virus, as NH4Cl treatment prevented HCV infection when applied prior to and during the first 90 min of infection (Fig. 7A) and had a minimal effect when applied at later time points (not shown). As expected, this treatment also inhibited VSVpp and had no effect on MLVpp infectivity (Fig. 7A). We then investigated the effects of nocodazole and wortmannin, which interfere with vesicular trafficking through the endosomal pathway. Nocodazole treatment causes the depolymerization of microtubules and inhibits trafficking between early and late endosomes, while wortmannin, at low concentrations, is a specific inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Both drugs reduced the infectivity of influenza A virus (not shown), which fuses at the level of late endosomes, while they did not have any effect on JFH-1 infectivity (Fig. 7A), indicating that HCVcc entry does not require delivery to late endosomes, as already shown for HCV pseudotyped retroviral particles (42).

FIG. 7.

Postentry requirements for HCV infection. (A) Huh-7 cells were mock treated or treated for 1 h with medium containing NH4Cl (10 mM), wortmannin (1 μM), or nocodazole (1 μM) and infected with different viruses for 3 h in the presence or absence of the drugs. Cells were then washed and left for 72 h in medium alone. Infectivity was determined by counting HCV core-positive cells under a fluorescence microscope. Infectivity is expressed relative to the values obtained in the absence of the drugs as the mean percentage ± the SD of four replicates in three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). As a control, infections with retroviral pseudoparticles bearing VSV-G or Abelson murine leukemia virus envelope proteins were performed as described for Fig. 3B. (B) Huh-7 cells were incubated with anti-CD81, rE2 plus anti-E2 MAb, or an isotype control for 5 min at 37°C and then cross-linked with GαM for the indicated times (minutes) at 37°C (5 min for the isotype control). Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-p42/p44 MAPK (p-Erk) antibody, stripped, and then reprobed with a rabbit polyclonal p42/p44 MAPK (Erk) antibody. (C) The Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway is required for a postentry event in HCV infection. Virus binding to cells was performed for 1 h at 4°C in the absence or presence of U0126 (1 μM). Subsequently, cells were washed and shifted to 37°C to allow entry. U0126 was added as indicated in the scheme; 2 h after warming, NH4Cl was added to block further infection (virus inactivation). Efficiency of infection was determined 72 h later as the percentage of HCV core-positive cells relative to control infections. Mean values and SD of four replicates in three independent experiments are shown (**, P < 0.001). The values to the left of the gels in panel B are molecular sizes in kilodaltons.

Finally, CD81 engagement activated the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, as evidenced by an increased phosphorylation level of ERK1/2 (Fig. 7B). To assess the biological relevance of ERK1/2 activation on HCV infectivity, we treated Huh-7 cells at different time points during infection with U0126, a specific inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase-(MAPK) kinases MEK-1 and MEK-2. The U0126 dose used here did not cause any cell death, even upon overnight exposure, as determined by trypan blue exclusion (not shown), while the kinetic of U0126 inhibitory activity shown in Fig. 7C suggested a role for ERK1/2 in a postentry step. Several other viruses, including influenza virus, coxsackievirus B3, and the murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus, have been shown to manipulate the host ERK signaling pathway and to be inhibited in their propagation by U0126 at postentry stages of their life cycles (8, 38, 51). In the case of HCV, activation of the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway is mediated by CD81, thus confirming that this molecule is key in HCV infection.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that CD81, rather then being a passive target for viral attachment to cells, plays a fundamental role in HCV infectivity, mediating not only the initial virus binding to the cellular surface but also the activation of endogenous cellular responses that provide assistance to the virus at different stages of its life cycle. CD81-mediated signals triggered Rho GTPase-dependent actin rearrangements that allowed lateral movement of the CD81/E2 complex and its delivery to areas of cell-cell contact. An intact actin network was required for the relocalization of engaged CD81 molecules, as pharmacological treatment with actin-destabilizing agents blocked lateral diffusion and dramatically reduced HCVcc infection of Huh-7 cells.

The CD81-mediated lateral migration of bound virus could explain how HCV present in human blood can be relocalized from the basolateral surface of hepatocytes to the TJs of polarized hepatocytes, the site where the coreceptor claudin-1 specifically localizes. Internalization would then occur by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, as already described (5), with transit through an endosomal low-pH compartment (32, 59).

The architecture of the hepatic parenchyma is unique compared to that of other epithelia and consists of multiple interconnected one-cell-thick plates separated by blood sinusoidal spaces. These plates consist of a single cell type, the hepatocyte, which is structurally and functionally polarized and has three distinct membrane domains: sinusoidal (basal), lateral, and canalicular (apical). Lateral plasma membranes come into close contact alongside bile canaliculi to form TJs that occlude the apical domain from the basolateral surface. Considering this, the use of the Huh-7 cell line as a model for infection does not fully represent the situation in the human liver. However, while isolated Huh-7 cells are relatively nonpolarized, if they are grown on lysine-coated plates, the contact between them triggers canalicular differentiation and the acquisition of membrane polarity (34). Under these conditions, we were able to observe the appearance of TJ-like structures, where the TJ components occludin, ZO-1, and claudin-1 preferentially accumulated and where the E2/CD81 complexes relocalized. In agreement with these data, a recent paper demonstrated that Huh-7 cells are capable of forming functional TJs, as assessed by proper localization of TJ-associated components and by measurements of transepithelial electric resistance (62).

Claudin-1 has been shown to be essential for HCV infection of human hepatoma cell lines, even though there is no clear evidence that it binds HCV directly. Recently, another transmembrane component of the TJ structurally related to claudins, occludin, has been shown to mediate group B coxsackievirus entry into target cells without interacting directly with the virus (16). Whether claudin-1 plays a similar role in HCV infection remains to be elucidated. In our system, we could not observe any internalization of the CD81/E2 complexes, even upon prolonged incubation at 37°C. It is conceivable that this represents a limit intrinsic to our experimental model and that proper endocytic internalization may be induced only by the more extensive cross-linking of CD81 by an ordered array of E2 ligand on the virion.

In our approach, we combined the use of surrogate systems to follow the early cellular events induced by CD81 engagement with the use of the recently established HCV cell culture system. To determine the physiological relevance of the different signaling pathways identified, all of the cellular events defined biochemically or by confocal microscopy have been tested for their effects on HCVcc infectivity with specific pharmacological agents and siRNAs. In this way, we were able to demonstrate that CD81 clustering, by HCV E2 or by antibodies, specifically activates different cellular signals that, when shut off, severely impair HCV infectivity. CD81 engagement activates different members of the Rho GTPase family that, in turn, mediate actin remodeling and initiate a mechanism that would allow transport of bound viruses from the apical surface to the TJ, whose integrity was also shown to be essential for virus infectivity. A number of studies (39) suggest that viruses move laterally on the plasma membrane before being internalized. These movements are actin dependent and appear to occur until the viruses have engaged sufficient receptors to initiate signaling events required for internalization. In the case of HCV, it is conceivable that the virus exploits GTPase-dependent actin remodeling induced by CD81 clustering to move to the TJs.

CD81 engagement also triggers the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway that plays a role in postentry events of the virus life cycle, as indicated by the kinetic of U0126 inhibition. The activation of this signaling pathway upon CD81 clustering has been already demonstrated in different cell types such as liver cancer cells (9), hepatic stellate cells (41), and cells of the immune system (17, 18). In these cellular systems, activation of the ERK/MAPK cascade has been associated with the pathogenesis of inflammation and fibrosis occurring in chronic HCV infection, with viral immune evasion strategies, and with immune system-mediated liver damage. Here we showed that HCV activates this cellular pathway to promote its own propagation inside the cell. We are currently investigating whether the initial wave of ERK activation mediated by virus binding to the surface is maintained over time by the subsequent process of infection, as already described for other viruses.

How CD81 mediates all of these different cellular events is not clear. As tetraspanins have no intrinsic enzymatic activity or typical signaling motifs, it is likely that they act mainly as adapter proteins, organizing other proteins into a network of multimolecular membrane microdomains (3, 27). Within this web, tetraspanins form primary strong complexes by interacting directly and specifically with other proteins and a network of secondary interactions through their tendency to associate with each other. In addition, the association with lipids contributes to the establishment of even larger complexes, with lipid raft-like properties. Despite similarities, lipid rafts and tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) are distinct, as they show different sensitivities to temperature and cholesterol depletion (12). Moreover, the specific primary and secondary interactions in TEMs are also present and can be studied in the soluble phase of detergent lysates, while lipid rafts are defined as detergent insoluble.

In our experiments, cholesterol depletion by nystatin or MβCD treatment did not influence CD81/E2 relocalization to the TJ, indicating that the signaling cascade initiated by CD81 engagement to promote lateral movement of the bound virions is still functional under these conditions. We speculate that the drastic effect of nystatin and MβCD on JFH-1 infectivity is due to the effects of the drugs on the TJs, as cholesterol depletion causes disassembly of the TJs (47), as reconfirmed here by displacement of claudin-1 and other TJ proteins from the plasma membrane. Tetraspanins have been shown to play a role in the pathology of various infectious diseases such as malaria (55, 56), human T-cell leukemia (50), and human immunodeficiency (40). Specific tetraspanins are selectively associated with specific viruses and may affect multiple stages of infectivity, from initial cellular attachment to syncytium formation and viral particle release, processes that have clear parallels in the physiological function of TEMs, often implicated in processes that involve cytoskeleton regulation. CD81 engagement has been shown to induce morphological changes and local F-actin accumulation in both NK and T cells (17); another tetraspanin, CD82, upon engagement, specifically associates with the cytoskeleton and induces morphological changes that are dependent on Rho GTPase activity and involve Vav and SLP76 activation (19). In addition, both CD81 and CD82 have been found in the contact zone between antigen-presenting cells and T cells where the T-cell receptor and signaling molecules assemble in a cytoskeleton-dependent manner (43).

In conclusion, our approach has allowed us to elucidate the cellular pathways triggered by HCV binding to CD81 and to show at which step these cellular events are required to promote viral infection. This study not only helps us to understand better the mechanism of HCV infection but also identifies new cellular targets for antiviral treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andreas Wack for critical reading of the manuscript, Susan Barnett and Brian Burke for sharing the SV-A-MLV plasmid, and Takashi Harada for the CD81 siRNA.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 June 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agnello, V., G. Abel, M. Elfahal, G. B. Knight, and Q.-X. Zhang. 1999. Hepatitis C virus and other Flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9612766-12771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartosch, B., A. Vitelli, C. Granier, C. Goujon, J. Dubuisson, S. Pascale, E. Scarselli, R. Cortese, A. Nicosia, and F. L. Cosset. 2003. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 27841624-41630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berditchevski, F. 2001. Complexes of tetraspanins with integrins: more than meets the eye. J. Cell Sci. 1144143-4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernards, A., and J. Settleman. 2004. GAP control: regulating the regulators of small GTPases. Trends Cell Biol. 14377-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchard, E., S. Belouzard, L. Goueslain, T. Wakita, J. Dubuisson, C. Wychowski, and Y. Rouille. 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 806964-6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucheix, C., and E. Rubinstein. 2001. Tetraspanins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 581189-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burridge, K., and K. Wennerberg. 2004. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell 116167-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai, Y., Y. Liu, and X. Zhang. 2007. Suppression of coronavirus replication by inhibition of the MEK signaling pathway. J. Virol. 81446-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carloni, V., A. Mazzocca, and K. S. Ravichandran. 2004. Tetraspanin CD81 is linked to ERK/MAPKinase signaling by Shc in liver tumor cells. Oncogene 231566-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavalieri, S., S. Cazzaniga, M. Geuna, Z. Magnani, C. Bordignon, L. Naldini, and C. Bonini. 2003. Human T lymphocytes transduced by lentiviral vectors in the absence of TCR activation maintain an intact immune competence. Blood 102497-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choo, Q. L., G. Kuo, A. J. Weiner, L. R. Overby, D. W. Bradley, and M. Houghton. 1989. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244359-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claas, C., C. S. Stipp, and M. E. Hemler. 2001. Evaluation of prototype transmembrane 4 superfamily protein complexes and their relation to lipid rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 2767974-7984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocquerel, L., C. Voisset, and J. Dubuisson. 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry: potential receptors and their biological functions. J. Gen. Virol. 871075-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cormier, E. G., F. Tsamis, F. Kajumo, R. J. Durso, J. P. Gardner, and T. Dragic. 2004. CD81 is an entry coreceptor for hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1017270-7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coyne, C. B., and J. M. Bergelson. 2006. Virus-induced Abl and Fyn kinase signals permit coxsackievirus entry through epithelial tight junctions. Cell 124119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne, C. B., L. Shen, J. R. Turner, and J. M. Bergelson. 2007. Coxsackievirus entry across epithelial tight junctions requires occludin and the small GTPases Rab34 and Rab5. Cell Host Microbe 2181-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crotta, S., V. Ronconi, C. Ulivieri, C. T. Baldari, N. M. Valiante, S. Abrignani, and A. Wack. 2006. Cytoskeleton rearrangement induced by tetraspanin engagement modulates the activation of T and NK cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 36919-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crotta, S., A. Stilla, A. Wack, A. D'Andrea, S. Nuti, U. D'Oro, M. Mosca, F. Filliponi, R. M. Brunetto, F. Bonino, S. Abrignani, and N. M. Valiante. 2002. Inhibition of natural killer cells through engagement of CD81 by the major hepatitis C virus envelope protein. J. Exp. Med. 19535-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaguillaumie, A., C. Lagaudriere-Gesbert, M. R. Popoff, and H. Conjeaud. 2002. Rho GTPases link cytoskeletal rearrangements and activation processes induced via the tetraspanin CD82 in T lymphocytes. J. Cell Sci. 115433-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerMardirossian, C., and G. M. Bokoch. 2005. GDIs: central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation. Trends Cell Biol. 15356-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreux, M., T. Pietschmann, C. Granier, C. Voisset, S. Ricard-Blum, P. E. Mangeot, Z. Keck, S. Foung, N. Vu-Dac, J. Dubuisson, R. Bartenschlager, D. Lavillette, and F. L. Cosset. 2006. High density lipoprotein inhibits hepatitis C virus-neutralizing antibodies by stimulating cell entry via activation of the scavenger receptor BI. J. Biol. Chem. 28118285-18295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans, M. J., T. von Hahn, D. M. Tscherne, A. J. Syder, M. Panis, B. Wolk, T. Hatziioannou, J. A. McKeating, P. D. Bieniasz, and C. M. Rice. 2007. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 446801-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flint, M., C. Maidens, L. D. Loomis-Price, C. Shotton, J. Dubuisson, P. Monk, A. Higginbottom, S. Levy, and J. A. McKeating. 1999. Characterization of hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein interaction with a putative cellular receptor, CD81. J. Virol. 736235-6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner, J. P., R. J. Durso, R. R. Arrigale, G. P. Donovan, P. J. Maddon, T. Dragic, and W. C. Olson. 2003. L-SIGN (CD 209L) is a liver-specific capture receptor for hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1004498-4503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall, A. 1998. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science 279509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heile, J. M., Y. L. Fong, D. Rosa, K. Berger, G. Saletti, S. Campagnoli, G. Bensi, S. Capo, S. Coates, K. Crawford, C. Dong, M. Wininger, G. Baker, L. Cousens, D. Chien, P. Ng, P. Archangel, G. Grandi, M. Houghton, and S. Abrignani. 2000. Evaluation of hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2 for vaccine design: an endoplasmic reticulum-retained recombinant protein is superior to secreted recombinant protein and DNA-based vaccine candidates. J. Virol. 746885-6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemler, M. E. 2005. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6801-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higginbottom, A., E. R. Quinn, C. C. Kuo, M. Flint, L. H. Wilson, E. Bianchi, A. Nicosia, P. N. Monk, J. A. McKeating, and S. Levy. 2000. Identification of amino acid residues in CD81 critical for interaction with hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2. J. Virol. 743642-3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu, M., J. Zhang, M. Flint, C. Logvinoff, C. Cheng-Mayer, C. M. Rice, and J. A. McKeating. 2003. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1007271-7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapadia, S. B., H. Barth, T. Baumert, J. A. McKeating, and F. V. Chisari. 2007. Initiation of hepatitis C virus infection is dependent on cholesterol and cooperativity between CD81 and scavenger receptor B type I. J. Virol. 81374-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koutsoudakis, G., E. Herrmann, S. Kallis, R. Bartenschlager, and T. Pietschmann. 2007. The level of CD81 cell surface expression is a key determinant for productive entry of hepatitis C virus into host cells. J. Virol. 81588-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koutsoudakis, G., A. Kaul, E. Steinmann, S. Kallis, V. Lohmann, T. Pietschmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 2006. Characterization of the early steps of hepatitis C virus infection by using luciferase reporter viruses. J. Virol. 805308-5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levy, S., and T. Shoham. 2005. The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5136-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lian, W. N., J. W. Tsai, P. M. Yu, T. W. Wu, S. C. Yang, Y. P. Chau, and C. H. Lin. 1999. Targeting of aminopeptidase N to bile canaliculi correlates with secretory activities of the developing canalicular domain. Hepatology 30748-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindenbach, B. D., M. J. Evans, A. J. Syder, B. Wolk, T. L. Tellinghuisen, C. C. Liu, T. Maruyama, R. O. Hynes, D. R. Burton, J. A. McKeating, and C. M. Rice. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohmann, V., F. Korner, J. Koch, U. Herian, L. Theilmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285110-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lozach, P. Y., H. Lortat-Jacob, A. de Lacroix de Lavalette, I. Staropoli, S. Foung, A. Amara, C. Houles, F. Fieschi, O. Schwartz, J. L. Virelizier, F. Arenzana-Seisdedos, and R. Altmeyer. 2003. DC-SIGN and L-SIGN are high affinity binding receptors for hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2. J. Biol. Chem. 27820358-20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo, H., B. Yanagawa, J. Zhang, Z. Luo, M. Zhang, M. Esfandiarei, C. Carthy, J. E. Wilson, D. Yang, and B. M. McManus. 2002. Coxsackievirus B3 replication is reduced by inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway. J. Virol. 763365-3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marsh, M., and A. Helenius. 2006. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell 124729-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin, F., D. M. Roth, D. A. Jans, C. W. Pouton, L. J. Partridge, P. N. Monk, and G. W. Moseley. 2005. Tetraspanins in viral infections: a fundamental role in viral biology? J. Virol. 7910839-10851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazzocca, A., S. C. Sciammetta, V. Carloni, L. Cosmi, F. Annunziato, T. Harada, S. Abrignani, and M. Pinzani. 2005. Binding of hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 to CD81 up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 in human hepatic stellate cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28011329-11339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meertens, L., C. Bertaux, and T. Dragic. 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry requires a critical postinternalization step and delivery to early endosomes via clathrin-coated vesicles. J. Virol. 8011571-11578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mittelbrunn, M., M. Yañez-Mó, D. Sancho, A. Ursa, and F. Sánchez-Madrid. 2002. Cutting edge: dynamic redistribution of tetraspanin CD81 at the central zone of the immune synapse in both T lymphocytes and APC. J. Immunol. 1696691-6695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyamura, T., and Y. Matsuura. 1993. Structural proteins of hepatitis C virus. Trends Microbiol. 1229-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molina, S., V. Castet, L. Pichard-Garcia, C. Wychowski, E. Meurs, J. M. Pascussi, C. Sureau, J. M. Fabre, A. Sacunha, D. Larrey, J. Dubuisson, J. Coste, J. McKeating, P. Maurel, and C. Fournier-Wirth. 2008. Serum-derived hepatitis C virus infection of primary human hepatocytes is tetraspanin CD81 dependent. J. Virol. 82569-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mousavi, S. A., L. Malerod, T. Berg, and R. Kjeken. 2004. Clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Biochem. J. 3771-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nusrat, A., C. A. Parkos, P. Verkade, C. S. Foley, T. W. Liang, W. Innis-Whitehouse, K. K. Eastburn, and J. L. Madara. 2000. Tight junctions are membrane microdomains. J. Cell Sci. 113(Pt. 10)1771-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Op De Beeck, A., L. Cocquerel, and J. Dubuisson. 2001. Biogenesis of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins. J. Gen. Virol. 822589-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pileri, P., Y. Uematsu, S. Campagnoli, G. Galli, F. Falugi, R. Petracca, A. J. Weiner, M. Houghton, D. Rosa, G. Grandi, and S. Abrignani. 1998. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282938-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pique, C., C. Lagaudriere-Gesbert, L. Delamarre, A. R. Rosenberg, H. Conjeaud, and M. C. Dokhelar. 2000. Interaction of CD82 tetraspanin proteins with HTLV-1 envelope glycoproteins inhibits cell-to-cell fusion and virus transmission. Virology 276455-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pleschka, S., T. Wolff, C. Ehrhardt, G. Hobom, O. Planz, U. R. Rapp, and S. Ludwig. 2001. Influenza virus propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling cascade. Nat. Cell Biol. 3301-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pöhlmann, S., J. Zhang, F. Baribaud, Z. Chen, G. J. Leslie, G. Lin, A. Granelli-Piperno, R. W. Doms, C. M. Rice, and J. A. McKeating. 2003. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins interact with DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J. Virol. 774070-4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossman, K. L., C. J. Der, and J. Sondek. 2005. GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6167-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scarselli, E., H. Ansuini, R. Cerino, R. M. Roccasecca, S. Acali, G. Filocamo, C. Traboni, A. Nicosia, R. Cortese, and A. Vitelli. 2002. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 215017-5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silvie, O., S. Charrin, M. Billard, J. F. Franetich, K. L. Clark, G. J. van Gemert, R. W. Sauerwein, F. Dautry, C. Boucheix, D. Mazier, and E. Rubinstein. 2006. Cholesterol contributes to the organization of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains and to CD81-dependent infection by malaria sporozoites. J. Cell Sci. 1191992-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silvie, O., E. Rubinstein, J.-F. Franetich, M. Prenant, E. Belnoue, L. Rénia, L. Hannoun, W. Eling, S. Levy, C. Boucheix, and D. Mazier. 2003. Hepatocyte CD81 is required for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite infectivity. Nat. Med. 993-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spaete, R. R., D. Alexander, M. E. Rugroden, Q. L. Choo, K. Berger, K. Crawford, C. Kuo, S. Leng, C. Lee, R. Ralston, et al. 1992. Characterization of the hepatitis C virus E2/NS1 gene product expressed in mammalian cells. Virology 188819-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stiasny, K., and F. X. Heinz. 2006. Flavivirus membrane fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 872755-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tscherne, D. M., C. T. Jones, M. J. Evans, B. D. Lindenbach, J. A. McKeating, and C. M. Rice. 2006. Time- and temperature-dependent activation of hepatitis C virus for low-pH-triggered entry. J. Virol. 801734-1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wack, A., E. Soldaini, C. Tseng, S. Nuti, G. Klimpel, and S. Abrignani. 2001. Binding of the hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 to CD81 provides a co-stimulatory signal for human T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 31166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wakita, T., T. Pietschmann, T. Kato, T. Date, M. Miyamoto, Z. Zhao, K. Murthy, A. Habermann, H. G. Krausslich, M. Mizokami, R. Bartenschlager, and T. J. Liang. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11791-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang, W., C. Qiu, N. Biswas, J. Jin, S. C. Watkins, R. C. Montelaro, C. B. Coyne, and T. Wang. 2008. Correlation of the tight junction-like distribution of claudin-1 to the cellular tropism of hepatitis C virus. J. Biol. Chem. 2838643-8653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhong, J., P. Gastaminza, G. Cheng, S. Kapadia, T. Kato, D. R. Burton, S. F. Wieland, S. L. Uprichard, T. Wakita, and F. V. Chisari. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1029294-9299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu, Q., Y. Oei, D. B. Mendel, E. N. Garrett, M. B. Patawaran, P. W. Hollenbach, S. L. Aukerman, and A. J. Weiner. 2006. Novel robust hepatitis C virus mouse efficacy model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 503260-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.