Abstract

The envelope fusion protein F of Plutella xylostella granulovirus is a computational analogue of the GP64 envelope fusion protein of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV). Granulovirus (GV) F proteins were thought to be unable to functionally replace GP64 in the AcMNPV pseudotyping system. In the present study the F protein of Agrotis segetum GV (AgseGV) was identified experimentally as the first functional GP64 analogue from GVs. AgseF can rescue virion propagation and infectivity of gp64-null AcMNPV. The AgseF-pseudotyped AcMNPV also induced syncytium formation as a consequence of low-pH-induced membrane fusion.

Baculovirus envelope fusion proteins play a key role in the cell-to-cell movement and systemic infection of viruses in insects via budded viruses (BVs). For the lepidopteran nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs), GP64 and F have not only been shown to be responsible for cell fusion upon entry but also to be essential for BV formation. Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) GP64 plays an important role in the attachment of virions to cells (5), low-pH-dependent membrane fusion (2, 7, 17), and efficient virion budding (15). Deletion of the gp64 gene is lethal for BV propagation; the deficiency can be rescued by gp64 homologues such as group II NPV F protein genes and vertebrate virus F genes (10, 12, 13, 14). Relative to NPVs, most granuloviruses (GVs) exhibit a relatively narrow host range and various tissue tropisms (21). GVs lack a gp64-like gene but have a putative F gene (18). The F protein of Plutella xylostella GV (PlxyGV), a pathogen which causes systemic infection to the diamondback moth P. xylostella (Yponomeutidae) (3, 4), cannot readily rescue the infectivity of gp64-null AcMNPV (12). It has hypothesized that the greater evolutionary distance between GVs and lepidopteran NPVs results in a less compatible interaction with AcMNPV proteins. This may be an explanation for the inability of the GV F proteins to compensate for the absence of GP64 in AcMNPV (12). However, in the present study we show that the F protein of Agrotis segetum GV (AgseF; GI151564275), a pathogen which causes systemic infection to the cutworm A. segetum (Noctuidae) and kills the infected larva in a few days (19), could rescue the infectivity of AcMNPV lacking its own envelope fusion protein GP64.

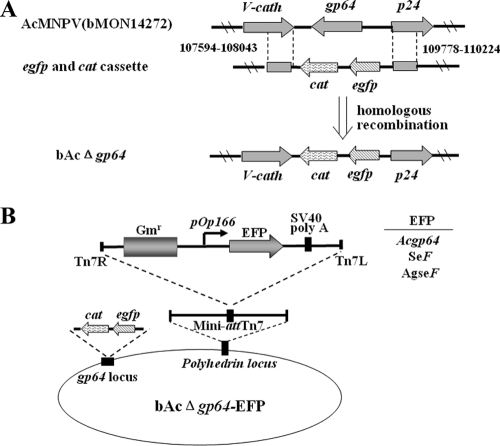

To determine whether AgseF could substitute for the function of GP64 in AcMNPV, the gp64 gene of AcMNPV was inactivated by replacement with a combined enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene cassette (Fig. 1A). This modified AcMNPV bacmid allowed the selection of recombinants in Escherichia coli through CAT and the detection of recombinants' replication in Sf9 cells through EGFP. The heterologous F genes, Spodoptera exigua MNPV-F (SeF) and AgseF, as well as Acgp64 (rescue control), were inserted into the polyhedrin locus of AcMNPV by using Tn7-mediated transposition (11). The structure of the recombinant bacmids generated is shown in Fig. 1B and includes (i) bAcΔgp64 (negative control), (ii) bAcΔgp64-gp64 (gp64 repaired), (iii) bAcΔgp64-SeF (positive control), and (iv) bAcΔgp64-AgseF (substitution of gp64 with AgseF). Positive clones proved to be correct by PCR and by EcoRI digestion (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

(A) Generation of the bacmid AcMNPVΔgp64. cat and egfp genes flanked by gp64 sequences (upstream nucleotides 109778 to 110224 and downstream nucleotides 107594 to 108043) were used for homologous recombination. (B) The structure of bacmids resulting in virions that are pseudotyped with F proteins. The envelope fusion protein genes (Acgp64, SeF, and AgseF) listed on the right under the control of the OpMNPV Op166 promoter were inserted into the polyhedrin locus of AcMNPV by Tn7-mediated transposition.

AgseF is a functional analogue of AcMNPV GP64.

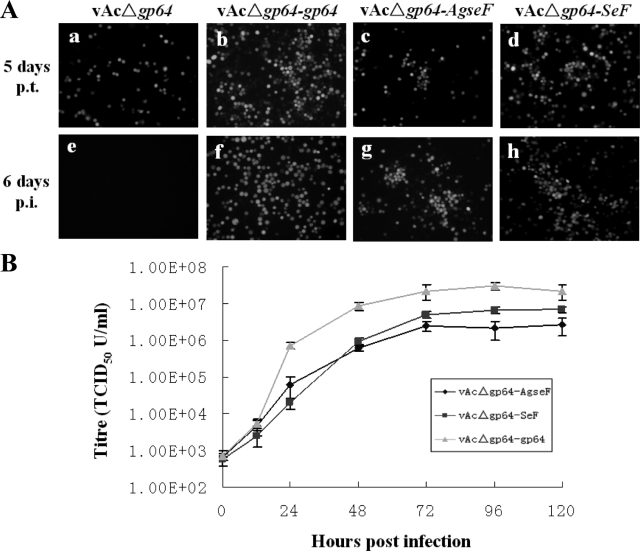

Using a transfection-infection assay, the effect of the gp64 deletion and F insertions on BV propagation could be determined by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2A). Upon transfection of Sf9 cells with bAcΔgp64 (Fig. 2Aa), many singly infected cells were seen (2Aa). Transfer of the supernatant to healthy cells did not result in infected cells (Fig. 2Ae), indicating that, as expected, BVs were not produced (15). As a positive control, gp64 was reinserted into bAcΔgp64 to give bAcΔgp64-gp64 (Fig. 1B) and the resulting virus (vAcΔgp64-gp64) rescued infectious BV production, since the supernatant of the primary transfection (Fig. 2Ab) was able to infect Sf9 cells efficiently (Fig. 2Af).

FIG. 2.

(A) Transfection-infection assays of pseudotype bacmids for viral propagation. The indicated bacmids (top) were transfected into Sf9 cells (a, b, c, and d). At 5 days posttransfection, clarified supernatants were used for infection of Sf9 cells (e, f, g, and h). The transfected and infected cells were observed by using fluorescence microscopy. (B) One-step growth curve analysis of BV production. Sf9 cells were infected at an MOI of 10 TCID50/cell by vAcΔgp64-SeF, vAcΔgp64-AgseF, or vAcΔgp64-gp64. BVs were harvested at the indicated time points postinfection, and titers were determined on Sf9 cells. Each data point represents the average titer from three independent infections. Error bars represent standard deviations.

To determine whether the F protein of AgseGV is a functional analogue of AcMNPV GP64 protein, the bacmid bAcΔgp64-AgseF (Fig. 1B) was transfected into Sf9 cells (Fig. 2A), and at 5 days posttransfection 0.5 ml of the supernatant was used to infect a fresh dish of Sf9 cells. As can be seen, vAcΔgp64-AgseF not only produced a primary infection upon transfection (Fig. 2Ac) but also produced infectious BVs (Fig. 2Ag). As a positive control for the functionality of F protein, bacmid bAcΔgp64-SeF was used and also showed a successful transfection and infection of Sf9 cells (Fig. 2Ad and h), as has been reported previously (12). These results demonstrate that deletion of the gp64 gene of the AcMNPV bacmid can be successfully complemented by AgseF and result in a functional pseudotyped AcMNPV.

One-step growth curves of infectious BV production were determined and compared to BV production from gp64-null AcMNPV substituted with SeF and gp64 (Fig. 2B). Sf9 cells were infected in parallel with vAcΔgp64-AgseF, vAcΔgp64-SeF, and vAcΔgp64-gp64 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50)/cell. Supernatants collected at the indicated time points postinfection were titrated by endpoint dilution on Sf9 cells. The virus titers of gp64-rescued AcMNPV are approximately 1 log unit higher than for AcMNPV pseudotyped with AgseF and SeF; the latter two showed similar levels of virus production (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that the efficiency of AgseF to substitute for the function of GP64 is similar to that of SeF.

Expression of AgseF in pseudotyped BV.

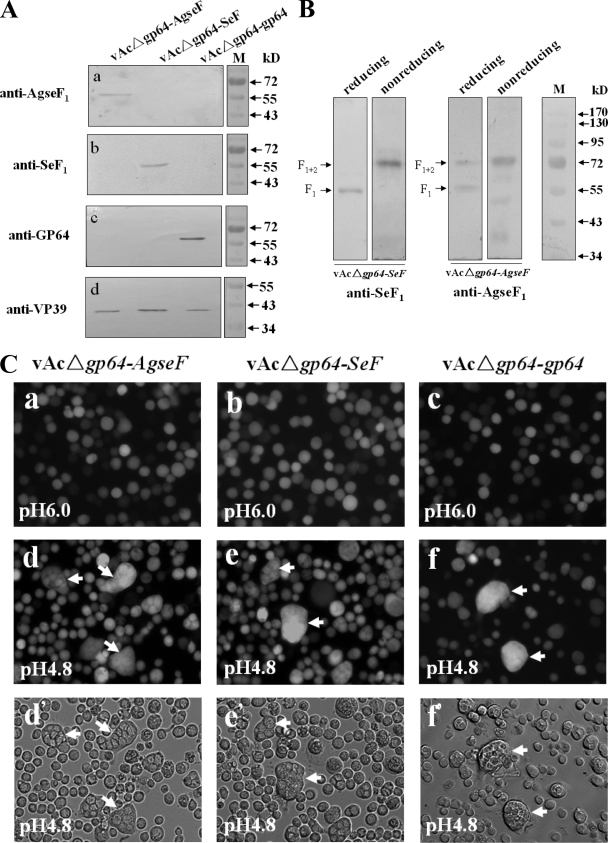

To show the presence of AgseF, vAcΔgp64-AgseF, vAcΔgp64-SeF, and vAcΔgp64-gp64 BVs were isolated from the supernatant of infected Sf9 cells and subjected to Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A and B). With the newly prepared antibody specifically against the large subunit F1 (amino acids 180 to 499) of AgseF according to procedures described previously (10), a band of about 57 kDa was detected in vAcΔgp64-AgseF BV, which was absent in lanes with proteins from vAcΔgp64-SeF and vAcΔgp64-gp64 BVs (Fig. 3Aa, lane 1). Similarly, a 59-kDa band was found in BVs from vAcΔgp64-SeF (Fig. 3Ab, lane 2) as expected for the size of SeF1 (6). BVs from vAcΔgp64-gp64 showed a band of 64 kDa (Fig. 3Ac, lane 3) representing GP64, the major envelope fusion protein of AcMNPV (2). Expression of GP64 was only detected in vAcΔgp64-gp64 BVs, and not in vAcΔgp64-SeF BVs or vAcΔgp64-AgseF BVs (Fig. 3Ac), a finding consistent with the lack of gp64 in bAcΔgp64 and the ability of SeF and AgseF to compensate for GP64 in AcMNPV infectivity. Since VP39 is the major capsid protein of AcMNPV, its detection was used as an internal control for the presence and an equal amount of BVs for each of the AcMNPV pseudotyped BV samples on the gel (Fig. 3Ad, lanes 1 to 3). These results confirm that the pseudotyped AcMNPV, which rescued infectivity, contained AgseF.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis and baculovirus-mediated cell fusion of pseudotyped gp64-null AcMNPV virions. (A) BVs pseudotyped with AgseF (lane 1), SeF (lane 2), and GP64 (lane 3) were detected by anti-AgseF1 (against 57-kDa cleavage product AgseF1), anti-SeF1 (against 59-kDa cleavage product SeF1), and anti-GP64 antisera. Anti-VP39 (nucleocapsid) antiserum was used as an internal control for each of the BV samples. (B) Posttranslational cleavage of SeF and AgseF. BVs of vAcΔgp64-SeF (lanes 1 and 2) and vAcΔgp64-AgseF (lanes 3 and 4) were collected from the supernatants of infected cells and separated under reducing (lanes 1 and 3) or nonreducing (lanes 2 and 4) conditions. The positions of F1 and F1+2 are indicated. The outer right lane contains marker proteins for size determination. (C) Baculovirus-mediated cell fusion. Sf9 cells were infected at an MOI of 10 TCID50/cell with either vAcΔgp64-AgseF (a, d, and d′), vAcΔgp64-SeF (b, e, and e′), or vAcΔgp64-gp64 (c, f, and f′) BV. At 48 h postinfection, cells were incubated with low pH (pH 4.8) Grace's medium for 10 min and then with the same medium but at pH 6.0. Syncytium formation was observed 24 h after the low-pH treatment. Multinucleate cells are indicated by arrows.

Posttranslational cleavage of group II NPV F-proteins by a proprotein convertase is essential for virus infectivity and results in two subunits that are linked by a disulfide bond (6, 10, 16, 20). The disulfide bridge between AgseF1 (C-terminal fragment) and AgseF2 (N-terminal fragment) was examined under both reducing and nonreducing conditions (Fig. 3B). For vAcΔgp64-SeF, a 59-kDa band (lane 1) and a 74-kDa band (lane 2) were detected, which correspond to SeF1 and SeF1+2 (F1 linked with F2), respectively (6). For AgseF, a 57-kDa band (lane 3) and a 75-kDa band (lane 4) were observed that would correspond to the predict sizes of AgseF1 and AgseF1+2. From these experiments we conclude that similar to NPV F proteins, the F-protein of AgseGV is probably cleaved by furin to release an N-terminal fragment F2 and a C-terminal membrane anchored fragment F1 linked by a disulfide bond.

Fusogenicity of AgseF.

Membrane fusion mediated by envelope fusion proteins of NPVs such as GP64, SeF, and HaF are activated by acidification (2, 6, 7, 8, 17). To determine whether low pH membrane fusion of Sf9 cells is mediated by AgseF as well, syncytium formation assays (6) were performed with vAcΔgp64-AgseF-infected cells (Fig. 3Ca, d, and d′). vAcΔgp64-SeF (Fig. 3Cb, e, and e′)- and vAcΔgp64-gp64 (Fig. 3Cc, f, and f′)-infected cells were used as positive controls for fusion. Cell-to-cell fusion was not observed upon infection of Sf9 cells by vAcΔgp64-AgseF virions (Fig. 3Ca). However, after exposure to low-pH medium for 10 min, cell fusion was observed after 24 h (Fig. 3Cd and d′). Low-pH-dependent fusion was also observed when Sf9 cells were transfected with plasmids carrying only the AgseF gene (data not shown). This confirms that AgseF is solely responsible for the fusogenicity of vAcΔgp64-AgseF.

Computational analysis did not reveal major structural differences between AgseF and PlxyF (data not shown). Both AgseF and PlxyF share all of the common features with NPV F proteins. AgseF contains a 24-residue cytoplasmic tail domain (CTD) that is similar to that of PlxyF (19 residues). Since a different length of the CTD is not an important determinant in the ability of an F protein to rescue AcMNPV gp64-null cells (9), the different performance of AgseF and PlxyF in the AcMNPV pseudotyping system is not likely due to a major difference in the structure of F, including CTDs. However, there are multiple smaller differences, which could explain the functional difference between PlxyF and AgseF. For example, the ends of the predicted fusion peptides are very different, with PlxyF having a glutamic acid, which is not particularly hydrophobic and could require a specialized interaction.

In summary, the AgseF has been characterized as a functional analogue of the AcMNPV GP64 protein and a homologue of baculovirus F proteins. This is the first study to experimentally identify a functional F protein from GVs. The successful substitution of GP64 with AgseF in AcMNPV and the functional characterization of AgseF provide further insight into the function of baculovirus envelope fusion proteins. Our data also emphasize the importance of studying phylogenetically distant baculovirus F proteins. In this context, it becomes interesting to see whether the nonlepidopteran baculoviruses, such as Culex nigripalpus (Diptera) NPV (1), also carry a functional GP64 analogue. Understanding the function of baculovirus F proteins furthers our understanding of baculovirus infection and evolution.

Acknowledgments

The anti-VP39 antiserum was kindly provided by Kai Yang. AgseGV occlusion bodies (NC_005839) were kindly provided by Xiulian Sun (Wuhan Institute of Virology, China Academy of Science).

The study was supported by NSFC grants (30470076, 30630002, and 30670078), the 973 project (2003CB114202), and the PSA project from MOST and KNAW (2004CB720404).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonso, C. L., E. R. Tulman, Z. Lu, C. A. Balinsky, B. A. Moser, J. J. Becnel, D. L. Rock, and G. F. Kutish. 2001. Genome sequence of a baculovirus pathogenic for Culex nigripalpus. J. Virol. 7511157-11165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blissard, G. W., and J. R. Wenz. 1992. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 666829-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto, Y., T. Hayakawa, Y. Ueno, T. Fujita, Y. Sano, and T. Matsumoto. 2000. Sequence analysis of the Plutella xylostella granulovirus genome. Virology 275358-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto, Y., E. Shimojo, K. Hayashi, T. Minakata, A. Kondo, M. Miyasono, and T. Matsumoto. 1996. Isolation and characterization of a granulosis virus isolated from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae). Bull. Fac. Text. Sci. Kyoto Inst. Tech. 2043-51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hefferon, K. L., A. G. P. Oomens, S. A. Monsma, C. M. Finnerty, and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Host cell receptor binding by baculovirus GP64 and kinetics of virion entry. Virology 258455-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IJkel, W. F. J., M. Westenberg, R. W. Goldbach, G. W. Blissard, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2000. A novel baculovirus envelope fusion protein with a proprotein convertase cleavage site. Virology 27530-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leikina, E., H. O. Onaran, and J. Zimmerberg. 1992. Acidic pH induces fusion of cells infected with baculovirus to form syncytia. FEBS Lett. 304221-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long, G., X. Pan, and J. M. Vlak. 2007. Absence of N-linked glycans from the F2 subunit of the major baculovirus envelope fusion protein F enhances fusogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 88441-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long, G., X. Pan, M. Westenberg, and J. M. Vlak. 2006. Functional role of the cytoplasmic tail domain of the major envelope fusion protein of group II baculoviruses. J. Virol. 801226-11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long, G., M. Westenberg, H. Wang, J. M. Vlak, and Z. Hu. 2006. Function, oligomerization, and N-linked glycosylation of the Helicoverpa armigera single nucleopolyhedrovirus envelope fusion protein, J. Gen. Virol. 87839-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luckow, V. A., S. C. Lee, G. F. Barry, and P. O. Olins. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 674566-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lung, O., M. Westenberg, J. M. Vlak, D. Zuidema, and G. W. Blissard. 2002. Pseudotyping Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV): F proteins from group II NPVs are functionally analogous to AcMNPV GP64. J. Virol. 765729-5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangor, J. T., S. A. Monsma, M. C. Johnson, and G. W. Blissard. 2001. A GP64-null baculovirus pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein. J. Virol. 752544-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monsma, S. A., A. Scott, A. G. P. Oomens, and G. W. Blissard. 1996. The GP64 envelope fusion protein is an essential baculovirus protein required for cell to cell transmission of infection. J. Virol. 704607-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oomens, A. G., and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Requirement for GP64 to drive efficient budding of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 254297-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson, M. N., R. L. Q. Russell, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2002. Functional analysis of a conserved region of the baculovirus envelope fusion protein, LD130. Virology 30481-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plonsky, I., and J. Zimmerberg. 1996. The initial fusion pore induced by baculovirus GP64 is large and forms quickly. J. Cell Biol. 1351831-1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohrmann, G. F., and P. A. Karplus. 2001. Relatedness of baculovirus and gypsy retrotransposon envelope proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi, Y. H., Z. Y. Wu, B. S. Qiu, X. F. Wang, and M. Y. Pei. 1983. The study of granulosis virus of Agrotis segetum. III. ELISA analysis of AgseGV. J. Cell Biol. 513-15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westenberg, M., H. Wang, W. F. J. IJkel, R. W. Goldbach, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2002. Furin is involved in baculovirus envelope fusion protein activation. J. Virol. 76178-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winstanley, D., and D. R. O'Reilly. 1999. Granuloviruses, p. 140-146. In R. Webster and A. Granoff (ed.), The encyclopedia of virology. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.