Abstract

Acetylation of histone tails is a hallmark of transcriptionally active chromatin. Mof (males absent on the first; also called MYST1 or KAT8) is a member of the MYST family of histone acetyltransferases and was originally discovered as an essential component of the X chromosome dosage compensation system in Drosophila. In order to examine the role of Mof in mammals in vivo, we generated mice carrying a null mutation of the Mof gene. All Mof-deficient embryos fail to develop beyond the expanded blastocyst stage and die at implantation in vivo. Mof-deficient cell lines cannot be derived from Mof−/− embryos in vitro. Mof−/− embryos fail to acetylate histone 4 lysine 16 (H4K16) but have normal acetylation of other N-terminal histone lysine residues. Mof−/− cell nuclei exhibit abnormal chromatin aggregation preceding activation of caspase 3 and DNA fragmentation. We conclude that Mof is functionally nonredundant with the closely related MYST histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Our results show that Mof performs a different role in mammals from that in flies at the organism level, although the molecular function is conserved. We demonstrate that Mof is required specifically for the maintenance of H4K16 acetylation and normal chromatin architecture of all cells of early male and female embryos.

Acetylation of the N-terminal tails of histones, catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases, is a critical element of gene regulation (reviewed in references 36 and 41). The MYST proteins, characterized by a highly conserved acetyltransferase domain, are involved in a wide range of physiological processes in mammals (reviewed in references 3, 22, and 34), ranging from the development of the nervous system (17, 35) to that of the hematopoietic system (12, 32). Mof (males absent on the first; also called MYST1 or KAT8) is one of the five mammalian MYST family histone acetyltransferases (18).

Mof was originally described as an essential component of the X chromosome dosage compensation system in Drosophila melanogaster. Mutations in Mof are lethal for male fruit flies (10). In male flies, Mof is part of a protein complex, the male-specific lethal (MSL) complex, required to increase gene expression from the single male X chromosome twofold (10). Interestingly, homologues of each protein of the Drosophila MSL complex have been identified in humans (26). Since male-to-female X chromosome dosage compensation occurs by a different mechanism in mammals, namely, by inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes in the female, Mof presumably has a different function in mammals than that in insects.

Mof has an amino-terminal chromodomain, reported to bind noncoding RNA (2), and a central MYST histone acetyltransferase domain. This domain structure is identical to that of Tip60 (human immunodeficiency virus Tat-interacting protein 60), and together, Mof and Tip60 form a subclass of MYST histone acetyltransferases (34). Mof and Tip60 are similar to the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Esa1p, which also has a chromodomain and a MYST domain. Esa1p is required for cell cycle progression in yeast and is one of the few essential histone acetyltransferases in yeast that causes severe phenotypic abnormalities when it is mutated (5, 27).

In mammalian cell culture systems, a variety of different activities have been ascribed to Mof, including roles in cell cycle regulation and response to DNA repair. In vitro depletion of Mof in 293T or HeLa cells can lead to the accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (26, 31). Under other conditions, however, a reduction in human Mof activity can result in a loss of the cell cycle checkpoint in response to DNA damage rather than in cell cycle arrest in 293 cells (9). In vitro, Mof can acetylate ATM, a protein with a key role in cell cycle checkpoint control, and through acetylation, modify its activity (9). Moreover, Mof can acetylate p53 at lysine 120, and this activity is important in directing the cell into an apoptotic pathway via the induction of Bax and Puma gene expression by p53, at least in H1299 cells (30). Another function ascribed to Mof is to enhance transcription as a coactivator for the trithorax group protein MLL in inducing the expression of the Hoxa9 gene (7). This action at a specific locus would mean that Mof may have distinctly different molecular roles in mammalian cells from those in insect cells, namely, effects on specific loci versus large regions of the genome, such as the male X chromosome.

In mammals, the Mof gene is ubiquitously expressed, and most tissues have similar, modest levels of expression (33). Exceptionally high levels of expression are found in the testis. Expression of Mof is high in late pachytene and diplotene spermatocytes as well as in round spermatids, suggesting that specific stages of sperm development require particularly high levels of Mof gene expression (33). Mof is expressed in both proliferating and postmitotic cells and, during development, does not appear to be restricted to regions with high levels of apoptosis or restricted to cells progressing through the cell cycle. The wide range of cellular processes that were reported to be affected by Mof, together with ubiquitous expression of the Mof gene, suggests that Mof is a multifunctional protein. In order to investigate the physiological role of Mof during embryonic development, we generated mice carrying a null mutation in the Mof gene.

We report here that the loss of Mof gene function in mice in vivo causes peri-implantation lethality. As discussed above, cell culture experiments revealed roles for mammalian Mof in cell cycle progression, but also in cell cycle checkpoint control, regulation of the response to DNA damage, and apoptosis. A major biochemical role of Mof in Drosophila and mammalian cells is histone 4 lysine 16 (H4K16) acetylation (1, 10, 31). In order to determine the essential physiological functions of Mof during development, we examined apoptosis, histone residue acetylation, and cell cycle parameters in mouse embryos lacking Mof. To assess a potential global role of Mof in chromatin regulation, we examined nuclear morphology in mutants and controls. Finally, we determined the time course of the manifestation of abnormalities in Mof mutant embryos. We show that Mof mutant embryos first lack acetylation specifically on H4K16 and then show abnormal chromatin morphology before finally undergoing death by apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of mutant Mof allele, timed matings, and Northern analysis.

A targeting construct for the Mof locus was produced using the “recombineering” method described by Liu and coworkers (16). A 13-kb fragment from the bacterial artificial chromosome RP23-310K3, which contains the entire Mof gene, was “recombineered” into pL253. A loxP site was introduced between exons 1 and 2, and a neomycin phosphotransferase expression cassette, flanked by frt sites and also containing a single loxP site at the 3′ end, was introduced between exons 5 and 6. This construct was electroporated into Bruce 4 embryonic stem (ES) cells (14), using standard techniques. Screening of 131 ES cell clones by Southern analysis yielded 13 homologously recombined clones. Nine of the 13 clones showed homologous recombination at both ends of the construct. We removed the neomycin phosphotransferase expression cassette, as well as exons 2 to 5, inclusive, by crossing offspring of the founder chimeras to a cre recombinase-expressing deleter strain (23). This resulted in a mouse strain in which bases 2373 to 8550 3′ of the start point of translation, including exons 2 to 5, have been deleted. A single loxP site is left between exons 1 and 6.

Mice were fed ad libitum and housed under a 12-h light-dark cycle. Experimental animals were backcrossed onto an F1 hybrid background of the strains FVB and BALB/c. For timed matings, females were housed with stud males, checked after 2 h for the presence of a vaginal plug, and then left to mate overnight. Mice were considered to be 0.5 day pregnant at midday if a vaginal plug was observed in the morning of the same day but was not present the previous evening. Experiments were undertaken with the approval of the Royal Melbourne Hospital Research Foundation Animal Ethics Committee.

PCR genotyping using three oligonucleotides allowed us to distinguish Mof+/+, Mof+/−, and Mof−/− embryos and mice. Amplification of the mutant allele resulted in a product of 229 bases, using oligonucleotide “wt1” (TCTCTGCATCTGTCCCTGTG) and oligonucleotide “dec2” (CCAGTGCTCCTGACTGTTGA), and a product of 153 bases resulted from amplification of the wild-type allele, using oligonucleotide “wt1” and oligonucleotide “wt2” (CTGGCTGGGGATTAAGACAG). Northern analysis was performed as described previously (33).

Histology, culture of embryos, and immunofluorescence.

Embryos were flushed using M2 medium and then cultured in M16 medium or ES cell medium as described previously (38). For histology, uteri were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin embedded, and then serially sectioned (5 μm). Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) and immunofluorescence were conducted as described previously (39). Antibodies used were anti-active caspase 3 (Promega G748A; 1:100), anti-acetylated H3K9 (Upstate 07-352; 1:500), anti-acetylated H3K14 (Upstate 07-353; 1:500), anti-acetylated H4K5 (Upstate 07-327; 1:500), anti-acetylated H4K8 (Millipore/Upstate 07-328; 1:500), anti-acetylated H4K12 (Abcam ab1761; 1:100), anti-acetylated H4K16 (Upstate 07-329; 1:500), and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Molecular Probes A-11035; 1:3,000).

Statistical analysis.

Frequencies of the three different genotypes with respect to the Mof locus, i.e., Mof+/+, Mof+/−, and Mof−/−, empty implantation sites, abnormal conceptuses, and embryos positive versus negative for histone residue acetylation, as indicated in the text and tables, were compared by the chi-square test. Acetylated H3K14 immunoreactivities, total cell numbers, numbers of mitotic cells, and mitotic indices were compared by one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher's post hoc test. The default α value of the StatView 5.0.1 software (5%) was used. P values are given as exact P values in the text and the tables or as “P < 0.0001,” where appropriate.

RESULTS

Generation of mutant allele.

The Mof protein consists of 458 amino acids carrying an amino-terminal chromodomain and a central MYST domain. The Mof gene consists of 11 exons. The chromodomain is encoded by exons 2 and 3, and the MYST domain is encoded by exons 5 to 9. We generated a Mof mutant allele by removing exons 2 to 5 as described in Materials and Methods and as shown in Fig. 1A and B. Splicing of exon 1 to exon 6 results in a frame shift such that only the first 57 amino acids can be produced from this allele. Since these 57 amino acids contain no functional domains, we concluded that this is a Mof null allele (Mof−/−). The deletion results in the removal of an NcoI restriction enzyme site between exons 3 and 4. Therefore, using a 3′ probe (Fig. 1A and B), a 7.2-kb wild-type band can be distinguished from an 8.9-kb mutant band by Southern analysis (Fig. 1C). In order to distinguish mutant and wild-type alleles in small quantities of material, we developed a PCR protocol using three oligonucleotides. Two products, of 229 bp and 153 bp, are generated from DNAs of Mof+/− heterozygous animals, whereas only the 153-bp product can be detected in wild-type animals and only the 229-bp product is detected for mutant embryos (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Mof−/− mutant allele. (A) Structure of the Mof locus prior to recombination. NcoI sites and a 3′ Southern probe are indicated. (B) Structure of the Mof locus after recombination and removal of the neomycin phosphotransferase cassette. (C) Note the change in size of the NcoI fragment, from 7,285 kb in the wild type (+/+) to 8,875 kb in Mof+/− heterozygous DNA (+/−), detected by Southern analysis using the 3′ probe. (D) Genotyping of E3.5 blastocysts from Mof+/− intercrosses, using three-way PCR. (E) Northern analysis showing differences in Mof mRNA levels in Mof+/− heterozygous (+/−) and wild-type (+/+) organs, as indicated. Densitometry values for wild-type and mutant tissues were corrected for loading and are shown below the top panel. (Bottom) Ethidium bromide staining of 18S rRNA on the nylon membrane. (F) Genotyping of E5.5 embryos from Mof+/− intercrosses, using three-way PCR.

Heterozygous animals were present at birth in the expected ratio, thrived, had normal fertility, and showed no obvious abnormalities. We analyzed Mof mRNAs from heterozygous and wild-type adult littermates in a range of tissues representing derivatives of the three germ layers, namely, the brain (ectoderm), kidney (mesoderm), liver (endoderm), spleen (mesoderm), and in particular, testis, the site of the highest Mof gene expression levels (Fig. 1E). We used a probe spanning bases 187 to 1082, as described previously (33). This probe includes exons 6, 7, 8, and 9, which were not deleted in our mutated Mof locus, accounting for 417 bp, or about 50%, of the 895-bp probe. Therefore, if splicing from exon 1 to exon 6 occurred at the Mof−/− allele in heterozygous animals, an additional mRNA species of 305 bp less than the wild-type mRNA, at approximately 50% of the intensity of the wild-type mRNA species, would be expected. Since the wild-type Mof mRNA is approximately 1.8 kb (33), a 1.5-kb mRNA should easily be detected. No mRNA species shorter (or longer) than the wild-type Mof mRNA was observed in heterozygous samples, despite extended autoradiography (Fig. 1E), suggesting that either the Mof mutant mRNA was unstable or the mutated allele was not transcribed. In each of these tissues, wild-type Mof mRNA levels were reduced in heterozygous animals. Densitometer readings indicated an overall reduction to 52% ± 4.6% of the wild-type level (P < 0.0001), showing that there was no compensation for the loss of one Mof allele by upregulation of the remaining wild-type allele.

Mutation of the Mof gene causes early embryonic lethality.

Expecting that a null mutation in the Mof gene would result in a recessive, embryonic lethal phenotype, we examined litters of heterozygous intercrosses at embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) and E8.5. We found that many implantation sites did not contain embryos (Table 1). Embryos recovered from all other implantation sites were of normal morphology and were either wild type or heterozygous. No Mof−/− homozygous embryos were detected (Table 1). This suggests that homozygous Mof−/− mutant embryos were able to induce a decidual reaction but were unable to develop to the point where embryonic structures are visible, at midgestation. Likewise, no normal homozygous embryos were detected at E5.5 or E6.5 (Table 1; Fig. 1F). The total absence of Mof−/− homozygous embryos differs significantly from the 25% expected if the Mof−/− allele were present in a Mendelian ratio (P < 0.0001) (Table 1). This shows that null mutation of the Mof gene causes peri-implantation embryonic lethality. A total of 39 wild-type and 96 Mof+/− heterozygous embryos were recovered between E5.5 and E9.5. The ratio of Mof+/+ to Mof+/− genotypes did not differ statistically from the 1:2 ratio expected when homozygous embryos are absent (P = 0.8542). Twenty-three of a total of 108 implantation sites isolated from E6.5 to E9.5 did not yield any embryonic material and were assumed to represent Mof−/− embryos. The fraction of empty implantation sites does not differ statistically from the expected 25% (P = 0.5075).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of the Mof −/− allele among offspring of Mof+/− intercrosses

| Developmental age | No. (%) of offspring with allele

|

No. (%) of empty implantations | Total no. (%) of offspring | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mof+/+ | Mof+/− | Mof−/− | |||

| E8.5 to E9.5 | 16 (22.5) | 43 (60.6) | 0a (0) | 12 (16.9) | 71 (100) |

| E6.5 | 8 (21.6) | 18 (48.6) | 0a (0) | 11 (29.7) | 37 (100) |

| E5.5 | 15 (30) | 35 (70) | 0a (0) | NDb | 50 (100) |

Significantly different from the expected Mendelian ratio of 25% (P < 0.0001).

ND, not determined.

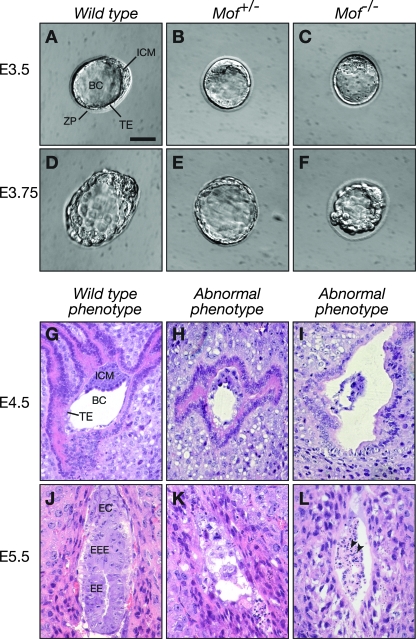

By examining preimplantation embryos, we recovered morphologically normal Mof−/− homozygous blastocysts (Fig. 1D and Fig. 2A to F). To determine the morphology of Mof−/− homozygous embryos shortly before their death, implantation sites from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses were compared histologically to those from control Mof+/− heterozygous-by-wild-type crosses at E4.5. As expected, all 23 implantation sites resulting from Mof+/− heterozygous-by-wild-type crosses contained morphologically normal embryos. In contrast, implantation sites resulting from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses contained a proportion of abnormal embryos. Severely affected embryos had a poorly developed inner cell mass, the blastocoelic cavities were not expanded, and the trophectoderm cells were degenerate (Fig. 2H and I versus G; Table 2). At E5.5, either no or only degenerating embryonic tissue was visible in the abnormal implantation sites (Fig. 2K and L versus J; Table 2). The remnant tissue detected contained cells with pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 2L), indicating chromatin condensation, usually associated with programmed cell death. At E6.5, no embryonic material was observed in 14 of 50 implantation sites (Table 2). From E4.5 to E6.5, 30 of a total of 147 implantation sites were found to be abnormal by histological examination (Table 2). This fraction does not differ statistically from the one-fourth abnormal conceptuses expected in the case of lethality of the Mof−/− embryos (P = 0.2598) (Table 2). Together, these results show that in the absence of embryonic Mof gene expression, embryos are unable to develop beyond expanded E4.5 blastocysts, although some embryonic cells, probably trophectoderm, can be detected histologically at E5.5.

FIG. 2.

Appearance of Mof−/− mutant embryos. Wild-type (A and D), heterozygous (B and E), and homozygous (C and F) embryos are shown at E3.5 (A, B, and C) and immediately prior to hatching (E3.75) (D, E, and F). Embryos were recovered from uteri after timed matings, individually photographed, and then genotyped. Histology of embryos was determined in utero. Uteri from timed matings were sectioned at E4.5 (G to I) and E5.5 (J to L). E4.5 embryos with normal morphology (G) and abnormal morphology (H and I) are shown. Note the poorly developed inner cell mass in the embryos depicted in panels H and I. At E5.5, uteri of Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses had significant numbers of implantation sites with either remnants of embryonic tissues (K) or only cells with pyknotic nuclei, indicative of cell death (L [arrowheads]). In uteri from control, heterozygous-by-wild-type matings, these mutant phenotypes were not observed. BC, blastocoelic cavity; EC, ectoplacental cone; EE, embryonic ectoderm; EEE, extraembryonic ectoderm; ICM, inner cell mass; TE, trophectoderm; ZP, zona pellucida. Bars, 53 μm (A to I) and 36 μm (J to L).

TABLE 2.

Histology assessment of conceptuses of Mof+/− intercrosses

| Developmental age | No. (%) of conceptuses with phenotype

|

Total no. (%) of conceptuses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Abnormala | ||

| E6.5 | 36 (72) | 14 (28) | 50 (100) |

| E5.5 | 45 (86.5) | 7 (13.5) | 52 (100) |

| E4.5 | 36 (80) | 9 (20) | 45 (100) |

Abnormal phenotype denotes poorly developed blastocysts at E4.5 and empty implantation sites at E5.5 and E6.5.

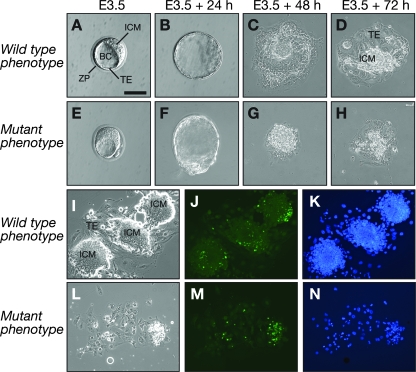

Mof is essential for inner cell mass cell survival in culture.

To examine if Mof−/− cells could survive in vitro, we recovered embryos from pregnant mice at E3.5 and cultured the embryos under conditions used to generate ES cell lines (38, 39). Embryos were collected from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses and compared to E3.5 embryos flushed from Mof+/− heterozygous-by-wild-type matings. Under these culture conditions, normal embryos hatched from the zona pellucida and attached to the cell culture substrate. The trophectoderm cells spread on the substrate, forming a monolayer, and within 72 h of culture, the inner cell mass proliferated to form a prominent inner cell mass outgrowth (Fig. 3A to D). Culturing embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous-by-wild-type matings, we found that there was no difference in the abilities of Mof+/− heterozygous and wild-type embryos to survive and proliferate in culture. Genotyping of these cultures revealed that the ratio of Mof+/− heterozygous to wild-type embryos did not differ from the expected 1:1 ratio (P = 0.8445) (Table 3). In contrast, although all embryos from Mof heterozygous intercrosses hatched and attached to the culture substrate, in 16 of 53 cases the growth and spreading of trophectoderm cells were limited. The survival rate of cultures derived from Mof+/− heterozygous-by-Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses differed significantly from that of cultures derived from control matings (P = 0.0004) (Table 3). Notably, in these cultures, the inner cell mass cells failed to proliferate and did not form an inner cell mass outgrowth (Fig. 3E to H). The phenotype of these embryo cultures was highly reproducible, cultures that would fail to survive could easily be identified 48 h after plating (Fig. 3G), and by 72 h, only remnants of the inner cell mass remained. When the cultures were used to prepare DNAs for genotyping after 10 days, no DNA was recovered from 16 of 53 cultures, all of which failed to produce an inner cell mass outgrowth. Genotyping showed that no homozygous embryos generated surviving cultures, and the ratio of wild-type to heterozygous cultures did not differ from the expected 1:2 ratio (P = 0.8059) (Table 3). The percentage of cultures that did not survive and were presumably derived from Mof−/− mutant embryos did not differ statistically from the expected 25% (P = 0.8266) (Table 3). We concluded from this comparison of embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses with embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous-by-wild-type matings that the embryos that degenerated from 48 h of culture onwards represented the homozygous phenotype. These results support our in vivo observations that homozygous embryos are able to survive until E4.5 but fail to develop beyond this point. The data also show that Mof−/− cells are unable to survive in culture, at least under the culture conditions used here, which ordinarily support the growth of ES cells as well as the survival of trophectoderm cells and, to a limited extent, primitive endoderm cells.

FIG. 3.

Appearance of Mof−/− mutant embryos during culture in vitro and cell death assessment. Embryos were recovered from uteri from Mof+/−-by-Mof+/− or from control Mof+/−-by-wild-type matings at E3.5 (A and E) and photographed daily. Day 1 images (B and F) show expanded blastocysts after 24 h in culture. Note that on day 1 of culture, there was no obvious difference between normal embryos and those embryos that would subsequently show a mutant phenotype. Day 2 images (C and G) show embryos attached to the culture substrate. Note that by day 3 (D and H), there were substantial differences in spreading of the trophectoderm cell layer and in development of an inner cell mass outgrowth in normal embryos (D) compared to embryos having an abnormal phenotype (H). (A, B, C, and D) Typical development of a normal embryo plated in ES cell medium. (E, F, G, and H) Progress of an embryo that displays the Mof−/− mutant phenotype. (I to K) Three normal embryos after 3 days of culture, stained using TUNEL to detect DNA fragmentation (J). Note that in these embryos, only a small proportion of the total number of cells at the periphery of the inner cell mass outgrowths is TUNEL positive (green). However, most inner cell mass cells in embryo cultures displaying the mutant phenotype (L) are TUNEL positive (M). (K and N) Bisbenzimide counterstain. Abbreviations are described in the legend to Fig. 2. Bars, 50 μm (A, B, E, and F), 46 μm (C and G), 68 μm (D and H), and 173 μm (I to N).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of Mof −/− allele among inner cell mass outgrowths

| Parental genotype | No. (%) of outgrowths with allele

|

No. (%) of outgrowths with no recoverable DNA | Total no. (%) of outgrowths | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mof+/+ | Mof+/− | Mof−/− | |||

| Mof+/− × Mof+/− | 13 (24.5) | 24 (45.3) | 0 | 16a (30.2) | 53 (100) |

| Mof+/+ × Mof+/− | 27 (50.0) | 25 (46.3) | NAb | 2 (3.7) | 54 (100) |

Significantly different from the control matings (P = 0.0004).

NA, not applicable.

Mof mutant cells die by apoptosis.

Since Mof−/− homozygous mutant embryos did not survive in vivo and did not give rise to cell lines in vitro, we examined their mode of death. We cultured embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous intercross matings and performed TUNEL, which labels cell nuclei containing fragmented DNA, a hallmark of apoptosis. Approximately 25% of embryos showed the degeneration phenotype, between day 3 and day 4 of culture, characteristic of Mof−/− homozygous mutant embryo cultures, as described above (Fig. 3A to H). Approximately 75% of cultures had normal morphology and underwent extensive proliferation of the inner cell mass, which was accompanied by the appearance of TUNEL-positive cells at the periphery of the inner cell mass outgrowth. However, the center of the proliferating inner cell mass as well as the trophectoderm monolayer was free of TUNEL-positive cells in cultures with normal morphology (Fig. 3I to K). In contrast, in cultures with Mof−/− homozygous mutant morphology, the majority of the remnant inner cell mass nuclei were TUNEL positive (Fig. 3L to N). Moreover, numerous TUNEL-positive trophectoderm cells could be seen in cultures with Mof−/− homozygous mutant morphology. We concluded that Mof−/− cells ultimately die by TUNEL-positive cell death.

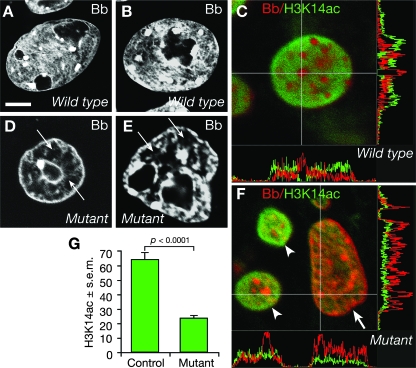

Mof mutant cells have abnormal chromatin distribution in the nucleus.

We examined nuclei of cultured embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous intercross matings by interference contrast optics (not shown) and their chromatin distribution after staining with bisbenzimide by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4). In addition, we assessed the distribution of transcriptionally active chromatin marked by acetylation of H3K14. In control nuclei, heterochromatin was visible in discrete areas of the nucleus that stained strongly with bisbenzimide (Fig. 4A and B) and was negative for marks of transcriptionally active chromatin (acetylation of H3K14) (Fig. 4C). Between the foci of dense heterochromatin, euchromatin could be observed as less strongly staining with bisbenzimide, often showing a filamentous or mesh-like bisbenzimide staining pattern (Fig. 4A and B). These areas of euchromatin stained strongly for acetylated H3K14 (Fig. 4C). One or more regions almost devoid of bisbenzimide staining could be seen in the normal nuclei, representing the nucleoli (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, distinctly different morphologies were observed in embryo cultures with a mutant phenotype. Nuclear morphology ranged from normal to severely disrupted, even within cultures derived from one embryo. In severe cases, almost all bisbenzimide staining was found in a few discrete clumps within large chromatin-free areas (Fig. 4D and E). In other cases, chromatin clumping was less severe, but nevertheless, the nucleus contained extensive chromatin-free areas and diffuse or filamentous staining was not apparent. When embryo cultures with a mutant phenotype were stained for acetylated H3K14, this marker of transcriptionally active chromatin was reduced in nuclei with abnormal chromatin distribution (Fig. 4F), while mutant nuclei that retained more normal morphology were positive for acetylated H3K14 (Fig. 4F). The overall H3K14 acetylation staining volume per nucleus was significantly reduced in cultures with mutant morphology compared to that in control cultures (Fig. 4G) (36% of controls; P < 0.0001). This type of abnormal distribution of chromatin was not seen in embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous-by-wild-type crosses.

FIG. 4.

Nuclear morphology in cultures of Mof−/− mutant embryos. (A to F) Confocal images of nuclei stained with bisbenzimide (gray scale) (A, B, D, and E) or stained with bisbenzimide (red) and for acetylated H3K14 (green) (C and F). Note the distribution of DNA stained by bisbenzimide in the wild-type nuclei (A and B), in strongly staining foci interspersed with diffuse and filamentous staining. Strongly bisbenzimide-positive foci (red) were negative for the active transcription marker H3K14ac (green) (C), shown in the nonoverlapping peaks and troughs of the x and y intensity plots displayed beside the nucleus. In the Mof−/− mutant nuclei (D and E), the DNA is aggregated in strongly bisbenzimide-positive foci, but between these are areas negative for bisbenzimide staining (arrows). The nuclei shown in panels D and E are representative of the fraction of cells most severely affected. A severely affected (arrow) and two less affected nuclei were stained for H3K14ac (green) (F). Note the reduction in H3K14 acetylation in the severely affected mutant nucleus with chromatin aggregation (arrow) and the comparably normal H3K14 acetylation in the less affected mutant nuclei (arrowheads). (G) Quantitation of mutant and control cultures showed a significant reduction in the H3K14 acetylation marker for transcriptionally active chromatin (observations were based on cultures from 14 embryos with the mutant phenotype and 20 embryos with control morphology; P < 0.0001 for quantitation [32 control nuclei and 73 mutant nuclei were assessed]). Bb, bisbenzimide; H3K14ac, acetylated lysine 14 on histone 3; s.e.m., standard error of the mean. Bars, 11 μm (A), 12 μm (B), 6 μm (D), and 5 μm (E).

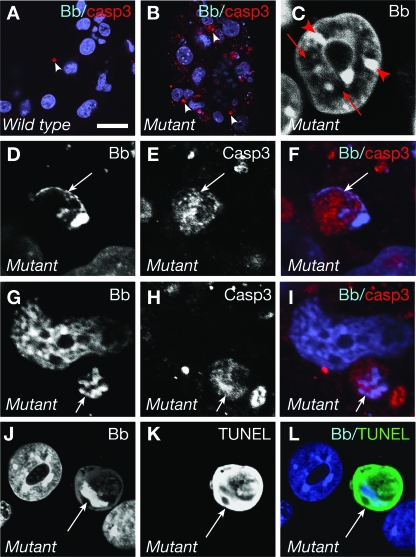

The abnormal chromatin distribution in Mof mutant cells precedes activation of caspase 3.

Changes in chromatin distribution are one of the signs of apoptosis. Therefore, we specifically examined cells positive and negative for indicators of apoptosis, namely, the activity of the effector caspase 3 and DNA fragmentation (TUNEL), in order to determine if the abnormal chromatin distribution observed in cultures with a mutant phenotype simply reflected a stage of apoptosis in the Mof−/− mutant embryos. In the course of apoptosis, activation of caspase 3 precedes DNA fragmentation, but caspase 3 subsequently remains active during the DNA fragmentation phase. TUNEL marks DNA fragmentation, the late stage of apoptosis. Active caspase 3-positive trophectoderm cells were rarely observed in cultures with the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 5A) but were prominent in cultures with a mutant phenotype (Fig. 5B). The abnormal chromatin distribution (Fig. 4D and E and 5C) seen in cultures with a mutant phenotype was observed in nuclei that were negative for active caspase 3 and TUNEL. Furthermore, in most cases, the abnormal chromatin distribution in these cells differed from the chromatin distribution seen in cells positive for active caspase 3 (Fig. 5D to I) or positive for TUNEL (Fig. 5J to L). The nuclei of active caspase 3-positive cells showed mostly chromatin marginalization (Fig. 5D) and, less frequently, irregular condensation (Fig. 5G), while TUNEL-positive cells exhibited more or less complete chromatin condensation and sequestration to one marginal position within the nucleus (Fig. 5J). Our findings suggest that changes in chromatin distribution precede the onset of apoptosis and are consistent with the possibility that apoptosis is an indirect consequence of abnormally distributed, inactive chromatin and failed transcription rather than a primary effect of loss of Mof.

FIG. 5.

Changes in nuclear morphology precede early and late indicators of apoptosis in cultures of Mof−/− mutant embryos. (A to L) Confocal images. Wild-type (A) and Mof−/− mutant embryo cultures (B) were stained with bisbenzimide (blue) and for active caspase 3 (red). (C) Mof−/− mutant nucleus stained with bisbenzimide (gray scale). Note the chromatin aggregates (arrowheads) and areas free of bisbenzimide staining (arrows). (D to I) Cells stained with bisbenzimide (gray scale) (D and G) and corresponding images of active caspase 3 immunofluorescence (gray scale) (E and H) and overlay (blue and red) (F and I). (J to L) Cells stained with bisbenzimide (gray scale) (J) and corresponding TUNEL (gray scale) (K) and overlay (blue and green) (L) images. Active caspase 3-positive nuclei were more numerous in Mof−/− mutant cultures (arrowheads in panels A and B). Abnormal chromatin distribution (C) was observed in nuclei of cells that were negative for active caspase 3 and TUNEL. The nuclear morphology of cells positive for active caspase 3 (arrows in panels D and G) and TUNEL (arrow in panel J) differed from the abnormal nuclear morphology observed in Mof−/− mutant cells preceding the onset of caspase 3 activity (C). Bb, bisbenzimide; casp3, active caspase 3. Bars, 49 μm (A and B), 5 μm (C), 8 μm (D to F), 7 μm (G to I), and 12 μm (J to L).

Mof mutant embryos show a specific loss of H4K16 acetylation.

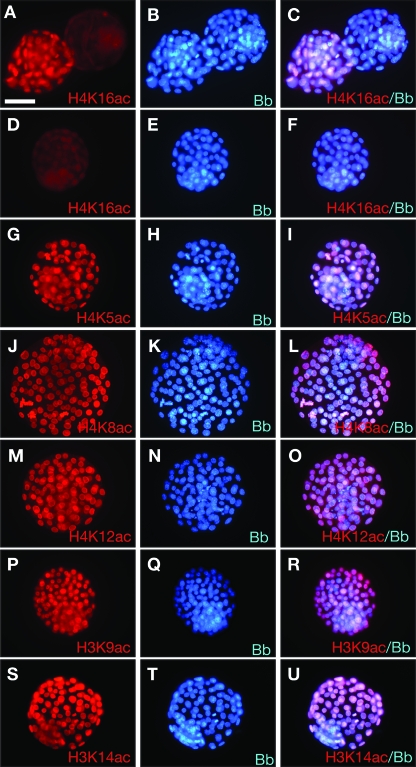

Mof has been shown to be the enzyme specifically responsible for H4K16 acetylation in Drosophila and in human cells in vitro (1, 10, 31). Therefore, we examined if mammalian Mof showed the same specificity in vivo. We collected blastocysts at E3.5 from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses, cultured them for 24 h to allow further time for any maternally encoded mRNA and protein to diminish, and examined their histone acetylation status by immunofluorescence. We observed that 14 of 35 embryos did not stain for acetylated H4K16 (Fig. 6A to F; Table 4). In contrast, all of 29 embryos isolated from wild-type-by-Mof+/− heterozygous matings stained positively for acetylated H4K16 (Table 4). The complete absence of histone acetylation in Mof mutant embryos was specific to H4K16, as all embryos of Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses stained positive for acetylation of lysines 5, 8, and 12 of histone 4 as well as lysines 9 and 14 of histone 3 (Fig. 6G to O and Table 4). Immunoreactivity for H4K8 acetylation was bright in mitotic nuclei in all embryos but varied in intensity in interphase nuclei of embryos recovered from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses. In contrast, mitotic and interphase nuclei of embryos recovered from wild-type matings stained comparably evenly for H4K8 acetylation. Variable H4K8 acetylation in embryos from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses may reflect a gradual loss of H4K8 acetylation in Mof mutant embryos. In contrast, H4K16 acetylation was completely absent from all nuclei in Mof mutant embryos. The lack of acetylated H4K16 staining was highly significant compared to staining in control matings (P = 0.0006) or to immunoreactivity to other acetylated residues (P < 0.0001) (Table 4), and the proportion of embryos lacking acetylated H4K16 staining, although high, was not statistically different from the expected 25% (P = 0.2032). These data show that mammalian Mof is required specifically to acetylate H4K16 in the early embryo in vivo, which mirrors the biochemical function of Mof in D. melanogaster (dMof). In contrast, Mof was not required for acetylation of H4K5, H4K12, H3K9, or H3K14 in E3.5 embryos cultured for 24 h, although Mof mutant nuclei showed a reduction in H3K14 acetylation 48 h later (Fig. 4). Mof is also not required for H4K8 acetylation in mitotic nuclei, although H4K8 acetylation in interphase nuclei appeared to be variable in E3.5 Mof mutant embryos cultured for 24 h.

FIG. 6.

Histone 3 and 4 acetylation of embryos from Mof+/−-by-Mof+/− intercrosses. Embryos were flushed from uteri from Mof+/−-by-Mof+/− intercrosses at E3.5, cultured for 24 h in M16 medium, and then subjected to immunofluorescence detection of acetylated lysine residues on histones 3 and 4, as indicated. (A, D, G, J, M, P, and S) Acetylated lysine residues or the absence thereof. (B, E, H, K, N, Q, and T) Bisbenzimide staining. (C, F, I, L, O, R, and U) Merged images. (A to F) Acetylated H4K16 was detected in only 21 of 35 embryos. A positive and a negative embryo are displayed side by side in panels A to C, and another negative embryo is shown in panels D to F. In contrast, acetylation of H4K5 (G to I), H4K8 (J to L), and H4K12 (M to O) as well as that of H3K9 (P to R) and H3K14 (S to U) was detected in all embryos. Labeling was done as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Bar, 43 μm (A to U).

TABLE 4.

Acetylation of histone residues in E3.5 embryos

| Immunoreactivity | No. of embryos from indicated cross with acetylation of histone residue

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4K16

|

H4K5 (Mof+/− mother × Mof+/− father) | H4K8 (Mof+/− mother × Mof+/− father) | H4K12 (Mof+/− mother × Mof+/− father) | H3K9 (Mof+/− mother × Mof+/− father) | H3K14 (Mof+/− mother × Mof+/− father) | ||

| Mof+/− mother × Mof+/− father | Mof+/+ mother × Mof+/− father | ||||||

| Positive | 21 | 32 | 21 | 29b | 29 | 22 | 26 |

| Negative | 14a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Significantly different from control matings (P = 0.0006) and from other acetylated histone residues (P < 0.0001).

Although all 29 embryos were positive for H4K8 acetylation, some embryos showed variable staining intensity in interphase nuclei.

Mof mutant embryos exhibit slightly elevated numbers of mitotic cells.

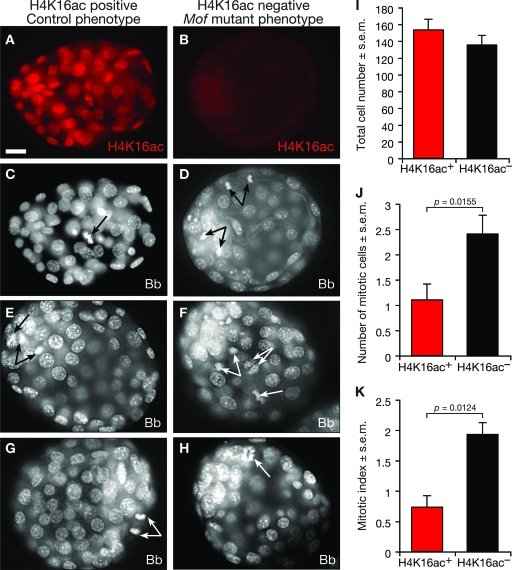

To assess the effects of the loss of Mof on mitosis, we determined the total number of cells and the number of mitotic cells per embryo. Embryos were recovered from Mof+/− heterozygous intercrosses at E3.5, cultured for 24 h, and stained with bisbenzimide and for H4K16 acetylation (Fig. 7A to H). The absence of H4K16 acetylation was used as an indication of the Mof−/− homozygous state. The total numbers of cells were not statistically different between H4K16 acetylation-positive (controls) and H4K16 acetylation-negative (Mof mutants) embryos (P = 0.3165) (Fig. 7I). In contrast, the number of mitotic cells was slightly but statistically significantly higher in the H4K16 acetylation-negative embryos (Mof mutants) than in H4K16 acetylation-positive embryos (controls; P = 0.0155) (Fig. 7J). The observation of a normal number of cells per embryo for the H4K16 acetylation-negative embryos shows that proliferation is not affected at this stage. The slightly elevated levels of mitotic cells may indicate that H4K16 acetylation-negative embryos take slightly longer to progress through M phase. However, because they have normal total numbers of cells, any extension of M phase must be compensated for by a shortening of another phase of the cell cycle. Alternatively, these data may be indicative of the beginning of a cell cycle arrest in M phase. Further work is required to differentiate between these two possibilities.

FIG. 7.

Mitosis in embryos from Mof+/−-by-Mof+/− intercrosses. (A to H) Embryos were flushed from uteri from Mof+/−-by-Mof+/− intercrosses at E3.5, cultured for 24 h in M16 medium, and then subjected to immunofluorescence detection of acetylated H4K16 (H4K16ac) (A and B). (C to H) Bisbenzimide staining to reveal mitotic and nonmitotic nuclei (gray scale). (A, C, E, and G) Embryos positive for H4K16 acetylation (the control phenotype). (B, D, F, and H) Embryos negative for H4K16 acetylation (the phenotype of Mof−/− mutant embryos). (I to K) Enumeration of the total cell number per embryo (I), the number of mitotic cells (J), and the mitotic index (K). The total numbers of cells were similar between phenotypes (P = 0.3165). Note that H4K16 acetylation-negative embryos had significantly more mitotic cells than did H4K16 acetylation-positive embryos (P = 0.0155; n = 10 embryos per genotype), with a higher mitotic index (P = 0.0124). Arrows indicate mitotic nuclei. s.e.m., standard error of the mean. Bar, 17 μm.

DISCUSSION

We have shown here that Mof is required for mouse embryos to develop beyond the expanded blastocyst stage. We have determined that Mof−/− blastocysts first have undetectable levels of H4K16 acetylation, then have a highly abnormal chromatin distribution, and subsequently die by apoptosis. In contrast to other MYST family proteins, such as Moz (Myst3) and Qkf (Myst4), which have specific functions in the hematopoietic system (12, 32) and the nervous system (17, 35), respectively, Mof appears to have a more general function in regulating chromatin structure.

During early mammalian development, the embryonic genome becomes activated at the two-cell stage (reviewed in reference 20), which is accompanied by changes in histone acetylation status (40). The early phase of development is supported by maternally encoded mRNA. Maternal proteins are present in the oocyte at fertilization, and proteins continue to be produced from stored maternal mRNA until the eight-cell stage. Consequently, a cell-autonomously lethal defect will not become apparent until maternally encoded protein is depleted. In this respect, it is interesting that mutation of Mof closely resembles the effect of mutating the Tbn gene (39). Tbn (Taf8) is a non-DNA-binding transcription factor (28). As maternally encoded Tbn protein becomes exhausted, the cells activate an apoptotic pathway leading to peri-implantation lethality (39), similar to the Mof mutant phenotype. These and similar studies show that stores of maternal mRNA generate sufficient quantities of essential nuclear proteins by the eight-cell stage to allow development to continue until the expanded blastocyst stage. At this stage, the blastocyst contains about 64 cells.

In Drosophila, dMof is required to hyperacetylate the single male X chromosome. Hyperacetylation is part of an X chromosome dosage compensation mechanism, which acts by increasing gene expression from the single male X chromosome twofold (4, 10, 25). Mutations in dMof are lethal for male flies because their X chromosome gene expression is inadequate. In this context, dMof is responsible for H4K16 acetylation (10), restricted, interestingly, to the male X chromosome (37). In contrast, in mammals, H4K16 acetylation is widespread throughout the genome, except for the inactivated female X chromosome, which contains low levels of this modification (11). X chromosome dosage compensation between male and female placental mammals occurs by a mechanism different from that in flies, namely, inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes in the females. We found no evidence for a differential requirement of Mof between males and female mammals, since all Mof−/− embryos died at the expanded blastocyst stage. This is consistent with dosage compensation proceeding by different mechanisms in mammals and insects. However, recent data comparing the global gene expression from the single male X chromosome and the single active female X chromosome in mammals to global gene expression from the paired autosomes suggest an approximately twofold upregulation of gene expression from the active X chromosome in both males and females (19). Interestingly, the single X chromosome is already upregulated at the blastocyst stage (15). Since all elements of the MSL complex are present in eutherian mammals (26), a function of this complex in regulating gene expression across the entire X chromosome in both males and females may well be conserved. Our findings exclude a sex-specific role for Mof in mammalian dosage compensation but are consistent with a role for Mof in X-chromosome-to-autosome dosage compensation. However, Mof is required for H4K16 acetylation throughout the genome in mammals, and therefore its role is certainly not restricted to X-chromosome-to-autosome dosage compensation.

A variety of functions in mammalian cells have been described for Mof in vitro. Human MOF was shown to participate in the activation of ATM in response to DNA damage in cultured cells (9). HeLa or 293T cells depleted of MOF accumulate in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, suggesting that Mof is involved in cell cycle regulation (26, 31). We found that expanded Mof mutant blastocysts had normal total cell numbers and elevated numbers of mitotic cells. Whether or not this is an early indication of a beginning block in the cell cycle in M phase requires further investigation. However, it appears that Mof null mutant cells, particularly the rapidly proliferating inner cell mass cells, certainly activate an apoptotic pathway once Mof protein levels become depleted.

Mof can acetylate p53 at lysine 120, and this is required for directing the cell along an apoptotic pathway, as opposed to entering cell cycle arrest. Depletion of Mof curbs the ability of p53 to induce expression of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bax and Puma in cultured cells (30). In contrast, our findings in vivo show that apoptosis ensues as a result of loss of Mof. Apoptosis is a normal feature of early embryonic development. In the blastocyst, apoptosis occurs in the inner cell mass, where cells die and exhibit the typical morphological features of programmed cell death (reviewed in reference 21). In the postimplantation period, the formation of the proamniotic cavity involves apoptosis of those inner cell mass cells that do not contribute to the formation of the epiblast (6). If the only function of Mof were to promote apoptosis, we would expect resistance to apoptosis in our mutant embryos. Examination of the Mof−/− mutant embryos shows that prior to death of the embryo, almost all cells show activation of caspase 3 and DNA fragmentation, which are clear signs of apoptosis. The high rate of apoptosis in Mof−/− mutant cells suggests that the primary role of Mof in the early embryo is not to act as a proapoptotic protein.

In agreement with the work of Gupta and coworkers, who studied a different Mof mutant allele and showed a reduction in acetylated H4K16 (8), we observed that loss of Mof causes a lack of acetylation on H4K16. Gupta and coworkers showed that H4K16 acetylation was normal in Mof mutant embryos before the blastocyst stage and absent from Mof mutant blastocysts (8). We determined that the acetylation defect was specific to H4K16. Acetylation of other histone residues was unaffected even 24 h after H4K16 acetylation was already undetectable. Importantly, we observed highly abnormal chromatin architecture in the Mof mutant cells. The appearance of aberrant chromatin morphology preceded activation of caspase 3 and DNA fragmentation, suggesting that although apoptosis of Mof−/− cells followed, it was nevertheless secondary to a defect in chromatin regulation. It appears that as the maternally encoded Mof protein level decreases, chromatin condenses in a disordered fashion, leading to randomly distributed aggregates of chromatin in the nucleus. This implies that the primary function of Mof is, directly or indirectly, to maintain large chromosomal domains in an open conformation. Interestingly, RNA interference knockdown of Mof in HeLa cells leads to a loss of acetylation on H4K16 and to abnormal nuclear architecture (31). In yeast, a balance between acetylation on H4K16 and deacetylation by the silencing machinery defines chromosomal boundaries between transcriptionally active and inactive chromatin (13, 29). Acetylation of H4K16, mediated by Mof, may exist to prevent chromatin from condensing. There is evidence in a variety of species to suggest that acetylation of chromatin, particularly H4K16, prevents the formation of higher-order, condensed chromatin structures (24). Therefore, these results suggest that the primary role of Mof is either to directly regulate the level of chromatin condensation or to promote the expression of a number of nuclear factors that normally function to keep chromatin in an open conformation.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate excellent technical assistance from T. McLennan, S. Michajlovic, D. Radford, A. Morcom, and M. Santamaria. We thank Neal Copeland for supplying the reagents used in BAC recombineering.

This work was supported by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 June 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhtar, A., and P. B. Becker. 2000. Activation of transcription through histone H4 acetylation by MOF, an acetyltransferase essential for dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 5367-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhtar, A., D. Zink, and P. B. Becker. 2000. Chromodomains are protein-RNA interaction modules. Nature 407405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avvakumov, N., and J. Cote. 2007. The MYST family of histone acetyltransferases and their intimate links to cancer. Oncogene 265395-5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone, J. R., J. Lavender, R. Richman, M. J. Palmer, B. M. Turner, and M. I. Kuroda. 1994. Acetylated histone H4 on the male X chromosome is associated with dosage compensation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 896-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke, A. S., J. E. Lowell, S. J. Jacobson, and L. Pillus. 1999. Esa1p is an essential histone acetyltransferase required for cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 192515-2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coucouvanis, E., and G. R. Martin. 1995. Signals for death and survival: a two-step mechanism for cavitation in the vertebrate embryo. Cell 83279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dou, Y., T. A. Milne, A. J. Tackett, E. R. Smith, A. Fukuda, J. Wysocka, C. D. Allis, B. T. Chait, J. L. Hess, and R. G. Roeder. 2005. Physical association and coordinate function of the H3 K4 methyltransferase MLL1 and the H4 K16 acetyltransferase MOF. Cell 121873-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta, A., T. G. Guerin-Peyrou, G. G. Sharma, C. Park, M. Agarwal, R. K. Ganju, S. Pandita, K. Choi, S. Sukumar, R. K. Pandita, T. Ludwig, and T. K. Pandita. 2008. The mammalian ortholog of Drosophila MOF that acetylates histone H4 lysine 16 is essential for embryogenesis and oncogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28397-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta, A., G. G. Sharma, C. S. Young, M. Agarwal, E. R. Smith, T. T. Paull, J. C. Lucchesi, K. K. Khanna, T. Ludwig, and T. K. Pandita. 2005. Involvement of human MOF in ATM function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 255292-5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hilfiker, A., D. Hilfiker-Kleiner, A. Pannuti, and J. C. Lucchesi. 1997. mof, a putative acetyl transferase gene related to the Tip60 and MOZ human genes and to the SAS genes of yeast, is required for dosage compensation in Drosophila. EMBO J. 162054-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeppesen, P., and B. M. Turner. 1993. The inactive X chromosome in female mammals is distinguished by a lack of histone H4 acetylation, a cytogenetic marker for gene expression. Cell 74281-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsumoto, T., Y. Aikawa, A. Iwama, S. Ueda, H. Ichikawa, T. Ochiya, and I. Kitabayashi. 2006. MOZ is essential for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Genes Dev. 201321-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura, A., T. Umehara, and M. Horikoshi. 2002. Chromosomal gradient of histone acetylation established by Sas2p and Sir2p functions as a shield against gene silencing. Nat. Genet. 32370-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontgen, F., G. Suss, C. Stewart, M. Steinmetz, and H. Bluethmann. 1993. Targeted disruption of the MHC class II Aa gene in C57BL/6 mice. Int. Immunol. 5957-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, H., V. Gupta, M. D. Vermilyea, F. Falciani, J. T. Lee, L. P. O'Neill, and B. M. Turner. 2007. Dosage compensation in the mouse balances up-regulation and silencing of X-linked genes. PLoS Biol. 5e326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, P., N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2003. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations. Genome Res. 13476-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merson, T. D., M. P. Dixon, C. Collin, R. L. Rietze, P. F. Bartlett, T. Thomas, and A. K. Voss. 2006. The transcriptional coactivator Querkopf controls adult neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2611359-11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neal, K. C., A. Pannuti, E. R. Smith, and J. C. Lucchesi. 2000. A new human member of the MYST family of histone acetyl transferases with high sequence similarity to Drosophila MOF. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1490170-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen, D. K., and C. M. Disteche. 2006. Dosage compensation of the active X chromosome in mammals. Nat. Genet. 3847-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nothias, J. Y., S. Majumder, K. J. Kaneko, and M. L. DePamphilis. 1995. Regulation of gene expression at the beginning of mammalian development. J. Biol. Chem. 27022077-22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pampfer, S., and I. Donnay. 1999. Apoptosis at the time of embryo implantation in mouse and rat. Cell Death Differ. 6533-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rea, S., G. Xouri, and A. Akhtar. 2007. Males absent on the first (MOF): from flies to humans. Oncogene 265385-5394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwenk, F., U. Baron, and K. Rajewsky. 1995. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 235080-5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shogren-Knaak, M., H. Ishii, J. M. Sun, M. J. Pazin, J. R. Davie, and C. L. Peterson. 2006. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science 311844-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith, E. R., C. D. Allis, and J. C. Lucchesi. 2001. Linking global histone acetylation to the transcription enhancement of X-chromosomal genes in Drosophila males. J. Biol. Chem. 27631483-31486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith, E. R., C. Cayrou, R. Huang, W. S. Lane, J. Cote, and J. C. Lucchesi. 2005. A human protein complex homologous to the Drosophila MSL complex is responsible for the majority of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16. Mol. Cell. Biol. 259175-9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith, E. R., A. Eisen, W. Gu, M. Sattah, A. Pannuti, J. Zhou, R. G. Cook, J. C. Lucchesi, and C. D. Allis. 1998. ESA1 is a histone acetyltransferase that is essential for growth in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 953561-3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soutoglou, E., M. A. Demeny, E. Scheer, G. Fienga, P. Sassone-Corsi, and L. Tora. 2005. The nuclear import of TAF10 is regulated by one of its three histone fold domain-containing interaction partners. Mol. Cell. Biol. 254092-4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suka, N., K. Luo, and M. Grunstein. 2002. Sir2p and Sas2p opposingly regulate acetylation of yeast histone H4 lysine16 and spreading of heterochromatin. Nat. Genet. 32378-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sykes, S. M., H. S. Mellert, M. A. Holbert, K. Li, R. Marmorstein, W. S. Lane, and S. B. McMahon. 2006. Acetylation of the p53 DNA-binding domain regulates apoptosis induction. Mol. Cell 24841-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taipale, M., S. Rea, K. Richter, A. Vilar, P. Lichter, A. Imhof, and A. Akhtar. 2005. hMOF histone acetyltransferase is required for histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 256798-6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas, T., L. M. Corcoran, R. Gugasyan, M. P. Dixon, T. Brodnicki, S. L. Nutt, D. Metcalf, and A. K. Voss. 2006. Monocytic leukemia zinc finger protein is essential for the development of long-term reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells. Genes Dev. 201175-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas, T., K. L. Loveland, and A. K. Voss. 2007. The genes coding for the MYST family histone acetyltransferases, Tip60 and Mof, are expressed at high levels during sperm development. Gene Expr. Patterns 7657-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas, T., and A. K. Voss. 2007. The diverse biological roles of MYST histone acetyltransferase family proteins. Cell Cycle 6696-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, T., A. K. Voss, K. Chowdhury, and P. Gruss. 2000. Querkopf, a MYST family histone acetyltransferase, is required for normal cerebral cortex development. Development 1272537-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner, B. M. 2000. Histone acetylation and an epigenetic code. Bioessays 22836-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner, B. M., A. J. Birley, and J. Lavender. 1992. Histone H4 isoforms acetylated at specific lysine residues define individual chromosomes and chromatin domains in Drosophila polytene nuclei. Cell 69375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voss, A. K., T. Thomas, and P. Gruss. 1997. Germ line chimeras from female ES cells. Exp. Cell Res. 23045-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voss, A. K., T. Thomas, P. Petrou, K. Anastassiadis, H. Scholer, and P. Gruss. 2000. Taube nuss is a novel gene essential for the survival of pluripotent cells of early mouse embryos. Development 1275449-5461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiekowski, M., M. Miranda, J. Y. Nothias, and M. L. DePamphilis. 1997. Changes in histone synthesis and modification at the beginning of mouse development correlate with the establishment of chromatin mediated repression of transcription. J. Cell Sci. 1101147-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang, X. J. 2004. The diverse superfamily of lysine acetyltransferases and their roles in leukemia and other diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 32959-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]