Abstract

ORAI1 is a pore subunit of the store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel. To examine the physiological consequences of ORAI1 deficiency, we generated mice with targeted disruption of the Orai1 gene. The results of immunohistochemical analysis showed that ORAI1 is expressed in lymphocytes, skin, and muscle of wild-type mice and is not expressed in Orai1−/− mice. Orai1−/− mice with the inbred C57BL/6 background showed perinatal lethality, which was overcome by crossing them to outbred ICR mice. Orai1−/− mice were small in size, with eyelid irritation and sporadic hair loss resembling the cyclical alopecia observed in mice with keratinocyte-specific deletion of the Cnb1 gene. T and B cells developed normally in Orai1−/− mice, but B cells showed a substantial decrease in Ca2+ influx and cell proliferation in response to B-cell receptor stimulation. Naïve and differentiated Orai1−/− T cells showed substantial reductions in store-operated Ca2+ entry, CRAC currents, and cytokine production. These features are consistent with the severe combined immunodeficiency and mild extraimmunological symptoms observed in a patient with a missense mutation in human ORAI1 and distinguish the ORAI1-null mice described here from a previously reported Orai1 gene-trap mutant mouse which may be a hypomorph rather than a true null.

Ca2+ is a universal second messenger that regulates a multitude of cellular functions, including secretion, muscle contraction, ion channel function, and gene expression (5). In many nonexcitable cells, Ca2+ influx occurs through “store-operated” Ca2+ channels which open in response to depletion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores (40). Physiologically, this occurs when ligand binds to receptors, such as G protein-coupled receptors, immunoreceptors, and receptor tyrosine kinases, that are coupled to the activation of phospholipase C. The resulting production of inositol trisphosphate leads to efflux of Ca2+ from the ER through inositol trisphosphate receptors and decreased Ca2+ concentration in the ER lumen. This decrease directly regulates the opening of store-operated Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane (26).

In lymphocytes and other immune system cells, the major route of Ca2+ influx is through store-operated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. CRAC currents (ICRAC) were first identified in T cells and mast cells (20, 21, 27, 53), and Ca2+ influx through CRAC channels is known to be essential for T-cell activation (8, 25). Mutant Jurkat tumor T-cell lines lacking functional CRAC channels cannot be activated properly (7); moreover, T cells obtained from three independent families of patients with hereditary severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) were shown to be severely deficient in store-operated Ca2+ entry and the CRAC channel current, ICRAC (10, 13, 23, 36). T-cell responses, particularly proliferation and cytokine production in vitro in response to T-cell receptor stimulation, were strongly impaired in patients from two of these families, explaining their SCID phenotype of increased susceptibility to infections in vivo (9, 12, 23). Notably, other cell types of the SCID patients (B cells, fibroblasts, and platelets) also showed diminished store-operated Ca2+ influx, although the functional consequences as read out by decreased proliferation and cytokine production were clearly the strongest for T cells (9, 12, 23).

The molecular players in the pathway leading to CRAC channel opening were recently identified by our own and other laboratories (reviewed in references 17 and 40). Two limited RNA interference screens, in Drosophila and human HeLa cells, respectively, identified Drosophila STIM and its human homologues STIM1 and STIM2 as proteins with essential roles in store-operated Ca2+ entry (29, 41). STIM proteins are ER transmembrane proteins with Ca2+-binding EF-hands located in the ER lumen, which permits them to function as sensors of Ca2+ levels in the ER (29, 41, 52). Depletion of Ca2+ stores causes dissociation of Ca2+ from the EF-hands of STIM1 and STIM2, triggering local oligomerization and relocalization to sites of ER-plasma membrane apposition that can be read out in the light microscope as “puncta” formation (4, 28, 29, 31, 48, 49). A second key regulator of store-operated Ca2+ entry was identified by three laboratories, including ours, in genome-wide Drosophila RNA interference screens (11, 47, 51). Drosophila ORAI and its human homologues, ORAI1, ORAI2, and ORAI3, are novel plasma membrane channel proteins with four transmembrane segments (15, 17, 38). Mutational and electrophysiological analyses confirmed that Drosophila ORAI and human ORAI1 were pore subunits of the CRAC channel (38, 45, 50). We identified a point mutation in human ORAI1—a single C→T transition resulting in an Arg to Trp substitution at amino acid 91 near the beginning of the first transmembrane helix—as the underlying molecular defect responsible for the lack of CRAC channel activity and store-operated Ca2+ entry and for hereditary SCID in human patients from one of the three families mentioned above (11).

ORAI1 and STIM1 are the limiting components required for CRAC channel activation. Combined overexpression of ORAI1 and STIM1 in numerous cell types results in Ca2+ currents which can be up to 50- to 100-fold larger than endogenous ICRAC, yet preserve most if not all of the characteristic biophysical features of ICRAC as determined by patch clamp analysis (37, 42, 50). Overexpression of ORAI2 or ORAI3 together with STIM1 also gives rise to large currents similar, but not identical, to ICRAC (6, 30), indicating that ORAI2 and ORAI3 may form Ca2+-permeable ion channels. ORAI proteins can interact with one another, and ORAI1 forms tetramers in the plasma membrane (15, 33). The physiological roles of ORAI and STIM family proteins are still being investigated. We have shown by conditional disruption of the Stim1 and Stim2 genes in mice that both STIM proteins contribute to store-operated Ca2+ entry and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NFAT in T cells (35). Moreover, combined deletion of Stim1 and Stim2 in T cells is associated with lymphoproliferative disease, which we have traced to a selective defect in the development and function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) (35). STIM1 also functions in muscle: mice with insertional inactivation of the Stim1 gene die perinatally from skeletal myopathy, and their myotubes lack store-operated Ca2+ entry and fatigue more rapidly than myotubes of wild-type mice (44). STIM1 and ORAI1 are both required for store-operated Ca2+ entry, cytokine production, and degranulation in mast cells, as shown by analysis of a second strain of STIM1-disrupted mice, as well as mice with a retroviral insertional mutation in the ORAI1 gene (2, 46). Mice with an insertional inactivation of ORAI1 were reported to show only minor defects in T-cell function (46), a surprising finding given the established importance of ORAI1 in human T cells as described above.

To address the physiological role of ORAI1, we generated mice with a targeted null allele of the Orai1 gene. We show here that ORAI1 is expressed in skin and lymphocytes and that gene-targeted mice lacking expression of ORAI1 protein have striking phenotypic and functional alterations in both tissues. Orai1−/− mice with the mixed ICR background showed a consistent overall phenotype of smaller size, eyelid irritation, and sporadic hair loss; in the immune system, lymphocyte development was normal but T- and B-cell function was impaired. These results suggest that the previously reported insertional mutation in the Orai1 gene (46) corresponds to a hypomorphic rather than a null allele.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and gene targeting.

Gene targeting of the Orai1 gene was performed by homologous recombination in B6/3 embryonic stem (ES) cells derived from C57BL/6 mice (TaconicArtemis GmbH, Koln, Germany). Chimeric mice with targeted Orai1 alleles were generated by blastocyst injection of heterozygous Orai1neo/+ ES cell clones. Founder Orai1neo/+ chimeric mice were bred to C57BL/6 mice to establish Orai1+/− mice. The Neo cassette was deleted by Cre expression under the control of the testis-specific angiotensin-converting enzyme promoter during spermatogenesis in chimeric mice. Rag2−/− γc−/− mice and outbred ICR mice were obtained from Taconic. All mice were maintained in specific-pathogen-free barrier facilities at Harvard Medical School and were used in accordance with protocols approved by the Center for Animal Resources and Comparative Medicine of Harvard Medical School. To generate Orai1−/− mice in a mixed genetic background, heterozygous Orai1+/− mice in the C57BL/6 background were intercrossed for one to three generations with mice of the outbred ICR strain (Taconic), after which heterozygotes were mated to generate N1F1-N3F1 mice.

Generation of fetal liver chimeras.

Fetal liver cells obtained from littermate control or Orai1−/− embryonic-day-14.5 embryos were injected intravenously into irradiated (7.5 Gy) Rag2−/− γc−/− mice. All reconstituted mice were sacrificed 6 weeks after transplantation to analyze the phenotypes of donor-derived cells in lymphoid organs.

Establishment of MEF cell lines.

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated by dissecting Orai1−/− embryonic-day-14.5 embryos using standard protocols.

T-cell differentiation, retroviral transductions, and stimulation.

Purification of CD4+ T cells from spleen and lymph nodes and induction of THN (“neutral”; cultured in the absence of exogenous cytokines), TH1, and TH2 differentiation were carried out for 6 days as described previously (1). Wild-type, Orai1+/−, and Orai1−/− CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). CD8+ T cells were purified from the pool of spleen and lymph nodes by negative selection using a CD8+ T cell negative isolation kit (Invitrogen) after the purification of CD4+ T cells. CD8+ T cells were activated by stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 48 h, and then cells were differentiated into cytolytic CD8+ T cells in medium containing 100 U/ml recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2) for 4 days. Retroviral transductions were performed as described previously (11) with pMSCV-CITE-eGFP-PGK-Puromycin retroviral expression plasmids, either empty or encoding ORAI proteins bearing an extracellular hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag inserted between transmembrane loops 3 and 4 (15, 38), followed by green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA under the control of an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). For cytokine expression, cells were stimulated with 10 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 1 μM ionomycin for 6 h, with 5 μg/ml brefeldin A added during the last 2 h.

Differentiation of bone marrow-derived mast cells.

Bone marrow-derived mast cells were generated from bone narrow cells isolated from femurs and tibias of mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice as described previously (43). Briefly, cells were maintained for 5 to 6 weeks in medium containing 50% WEHI-3 cell (ATCC)-conditioned supernatant as a source of IL-3. Differentiation was verified by metachromatic staining of cytoplasmic basophilic granules with toluidine blue and by surface staining of membrane c-Kit (43).

Cell surface staining and intracellular cytokine analysis.

Single-cell suspensions of thymuses, lymph nodes, spleens, and bone marrow (two femurs) were prepared and stained with fluorochrome- or biotin-conjugated mAbs, respectively. For each staining, at least 10,000 events were collected for analysis. The following antibodies were obtained from BD PharMingen: allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-B220 (30-F11 for all anti-B220), peridinin chlorophyll protein—anti-B220, phycoerythrin-anti-CD8 (53-6.7), phycoerythrin-anti-CD25 (PC61), allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD4 (RM4-5), fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-immunoglobulin D (IgD) (11-26), fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-CD43 (S7 for all anti-CD43), and peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5-conjugated streptavidin. Viable cells were assessed by trypan blue staining. Cytokine production was measured by intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis as described previously (1). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were pretreated with anti-CD16/CD32 (Pharmingen) to avoid nonspecific staining. Data were collected with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed by using FlowJo software (Treestar).

Proliferation assay for T or B cells.

CD4+ T cells were purified as described previously (1). B cells were isolated by using a B cell negative isolation kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). B cells and CD4+ T cells with >95% purity were labeled with 4 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) for 3 min at 37°C, the reaction was quenched using 50% fetal bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline, and the cells were then washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline. CFSE-labeled T cells (2.5 × 105) were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 48 h. Amounts of 2.5 ×105 B cells were cultured with various amounts of IgM or lipopolysaccharide on a 24-well plate for 48 h. The number of cell divisions was assessed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur.

Single-cell intracellular free calcium imaging.

CD4+ T and CD19+ B cells were isolated as described above. CD4+ CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes were sorted by using a FACSAria (BD Bioscience). Cells were incubated overnight in culture medium and loaded at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml with 1 μM fura-2/AM (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 22 to 25°C. Before measurements, T and B cells were attached to poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips for 15 min. For anti-CD3 stimulation, T cells were preincubated with 5 μg/ml biotin-conjugated anti-CD3 mAb (clone 2C11; Invitrogen) for 15 min at 22 to 25°C, after which anti-CD3 cross-linking was achieved by perfusion of cells either with 10 μg/ml streptavidin (Pierce) or with goat anti-hamster IgG (10 μg/ml), respectively. B cells were activated with 10 μg/ml anti-IgM (Jackson laboratory). Measurements of intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) were carried out and analyzed as described previously (11). For each experiment, ∼100 individual T or B cells were analyzed for their 340/380 ratio by using Igor Pro analysis software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Northern blot analysis and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was extracted from purified naïve T cells, naïve B cells, or differentiated T cells by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). An amount of 15 μg total RNA was separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, and then transferred onto Nytran SuPerCharge membrane (Schleicher and Schuell Bioscience). Probes with incorporated [α-32P]dCTP were synthesized from PCR fragments corresponding to the 3′ untranslated region of murine Orai mRNAs by using random-prime labeling mix (Pharmacia) and purified by using Sephadex G50 spin columns (Pharmacia). The following primers were used to generate the 3′ untranslated region PCR fragments used to make the labeled probes: Orai1, 5′ TCAATGAGCTGGCCGAGTTTGC and 3′ AGTAAGGAGTTTGAGGGCAGGACA; Orai2, 5′ TGGCCAGGCACATCTGTAAGGTAA and 3′ ATACACAGATGGCTGTCCCATGCT; and Orai3, 5′ AGTTGTTTGCTCCTCCAGGAAGGT and 3′ GTGGTGGTGGTGCATGCCTTTAAT.

For RT-PCR, first-strand DNA was synthesized by using 2 μg of total RNA and random hexamer primer with a Superscript II first-strand kit (Invitrogen). The following primers were used for RT-PCR: murine Orai1 5′ primer, 5′ CGAGTCACAGCAATCCGGAGCTTC and 3′ TGGTTGGCGACGATGACTGATTCA.

Patch clamp measurements.

CD4+ T cells were cultured in THN conditions and harvested at day 5. Patch clamp recordings were performed by using an Axopatch 200 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) interfaced to an ITC-18 input/output board (Instrutech, Port Washington, NY) and an iMac G5 computer. Currents were filtered at 1 kHz with a four-pole Bessel filter and sampled at 5 kHz. Recording electrodes were pulled from 100-μl pipettes (VWR), coated with Sylgard, and fire-polished to a final resistance of 2 to 5 MΩ. Stimulation and data acquisition and analysis were performed by using in-house routines developed on the Igor Pro platform (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). All data were corrected for the liquid junction potential of the pipette solution relative to Ringer's in the bath (−10 mV) and for leak currents collected in 20 mM extracellular free calcium plus 25 μM La3+. The standard extracellular Ringer solution contained 130 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 20 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM d-glucose, and 5 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.4). In some experiments, 2 mM CaCl2 was used in the standard extracellular solution and the NaCl concentration was raised to 150 mM. The standard divalent-free (DVF) Ringer solutions contained (in mM) 150 NaCl, 10 HEDTA, 1 EDTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4). A concentration of 25 nM charybdotoxin (Sigma) was added to all extracellular solutions to eliminate contamination from Kv1.3 channel currents. The standard internal solution contained 145 mM Cs aspartate, 8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 1,2-bis-(aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), and 10 mM Cs-HEPES (pH 7.2). Averaged results are presented as the mean value ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Curve fitting was done by least-squares methods by using built-in functions in Igor Pro 5.0. The relative permeability (P) of Cs+ (PCs/PNa) was calculated from the bi-ionic reversal potential by using the relation PCs/PNa = ([Cs]i/[Na]o)e−ErevF/RT, where R is the gas constant (8.314 J K−1 mol−1); T is the absolute temperature; F is the Faraday constant (9,648 C mol−1); PCs and PNa are the permeabilities of Cs+ and Na+, respectively; [Cs]i and [Na]o are the intracellular and extracellular ionic concentrations, respectively, of Cs and Na; and Erev is the reversal potential.

Antibody and histology.

A polyclonal antibody against the C terminus of ORAI1 was raised by immunizing rabbits with a conserved 17-amino-acid peptide corresponding to amino acids 278 to 294 of human ORAI1 (NP_116179) using standard protocols (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL; http://www.openbiosystems.com/antibodies/custom/polyclonal/2rabbit70day/). For immunohistochemistry, the antiserum was affinity-purified using the immunizing peptide. Immunohistochemistry was performed with support from the specialized histopathology core lab of the Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. Briefly, 5-μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sagittal tissue sections of newborn mice were soaked in xylene, passed through graded alcohols, and put into distilled water. Slides were then pretreated with 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) in a steam pressure cooker (Decloaking Chamber, BioCare Medical, Walnut Creek, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by washing in distilled water. Slides were pretreated with peroxidase block (Dako USA, Carpinteria, CA) for 5 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Affinity-purified rabbit anti-ORAI1 antibody was applied in Dako diluent for 1 h. For peptide block, anti-ORAI1 antibody was incubated with the C-terminal peptide used for immunization at a 1:1 molar ratio for 20 min at 4°C before dilution. Slides were washed in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody for 30 min (Envision+ detection kit; Dako) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After further washing, immunoperoxidase staining was developed by using a diaminobenzidine chromogen (Dako) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Tissues were visualized with an upright Leica DM LM microscope using 20×, 40×, and 63× dry objectives. Pictures were acquired with a MagnaFire cooled charge-coupled-device camera and MagnaFire software (both from Optronics, Goleta, CA).

RESULTS

Expression of ORAI1 in skin and lymphocytes of wild-type mice.

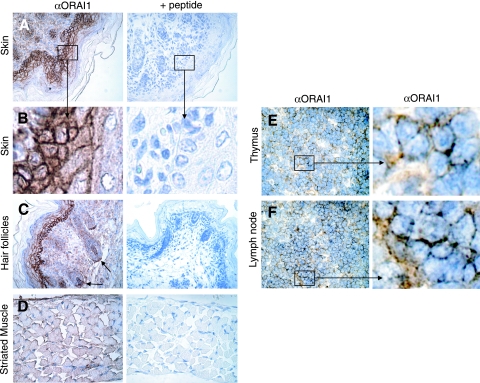

To investigate the endogenous expression pattern of ORAI1 in mouse tissues, we generated a polyclonal antibody to the intracellular C terminus of ORAI1. We used this antibody to stain tissue sections of newborn mice and lymphoid organs of adult C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1). The strongest signal was observed in keratinocytes of the stratum germinosum and stratum spinosum of the epidermis (Fig. 1A and B). Strong expression was observed in hair follicles as well (Fig. 1C). We also observed ORAI1 expression in muscle fibers of the thoracic diaphragm (Fig. 1D), as well as skeletal muscle of the trunk and intercostal muscles (data not shown). Weaker but clearly discernible expression was observed in lymphocytes located in the medulla of peripheral lymph nodes and the thymus of ∼8-week-old mice (Fig. 1E and F). We did not detect ORAI1 expression in cardiomyocytes or in the central nervous system (data not shown). Expression in lymphocytes was expected given the important functional role of ORAI1 for Ca2+ influx in human lymphocytes (10-12) and in mouse lymphocytes as shown below. On a cellular level, the ORAI1 signal was most prominent at the cell circumference, compatible with the expression of ORAI1 in the plasma membrane.

FIG. 1.

Expression of ORAI1 in skin, skeletal muscle, and lymphocytes of wild-type mice. (A to D) Sagittal sections of newborn mice were stained with rabbit polyclonal antibody to ORAI1 followed by peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody and counterstaining with hematoxylin. Where indicated (+ peptide), anti-ORAI1 antibody was preincubated with the immunizing peptide for peptide block. (A, B) ORAI1 staining is present in ectodermally derived epidermal keratinocytes with a pattern indicative of plasma membrane expression (see enlarged area in panel B). (C) ORAI1 is expressed in the mesenchymally derived dermal papillae and dermal sheath of hair follicles. (D) ORAI1 is expressed in the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle. Shown here is a sagittal section of the thoracic diaphragm. (E, F) ORAI1 staining in lymphocytes found in the medulla of thymus (E) and lymph nodes (F) of ∼8-week-old wild-type C57BL/6 mice. α, anti.

Generation of Orai1−/− mice.

We targeted the first exon of Orai1, which encodes the first 103 amino acids of the protein, including the first portion of transmembrane domain 1 (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Exon 1 was replaced with a self-deleting neomycin cassette that is excised in the germ line of male mice carrying the targeted allele (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Heterozygous and homozygous null mice were identified by Southern analysis of genomic DNA, as well as by PCR (see Fig. S1B and C in the supplemental material; data not shown). We confirmed the complete absence of Orai1 transcript in CD4+ T cells and CD19+ B cells of ORAI1-deficient mice by RT-PCR (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material). ORAI1-deficient mice in the C57BL/6 background showed perinatal lethality, with null mice born at lower than the expected Mendelian frequency and all surviving pups dying within 0.5 to 1.5 days after birth.

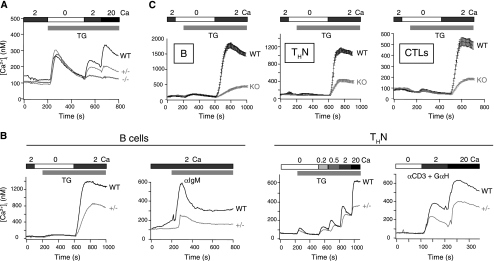

Defect in store-operated Ca2+ entry in ORAI1-deficient fibroblasts and lymphocytes.

To analyze the effect of ORAI1 deficiency on store-operated Ca2+ entry, we examined MEFs derived from homozygous positive, heterozygous, and homozygous null C57BL/6 background mice. Orai1−/− MEFs showed an almost complete loss of store-operated Ca2+ entry in response to thapsigargin, whereas heterozygous Orai1+/− MEFs showed an intermediate but striking decrease (Fig. 2A). Given the clear effect of haploinsufficiency of ORAI1, we also examined T and B cells from heterozygous Orai1+/− mice in the C57BL/6 background (Fig. 2B). Differentiated CD4+ T cells and freshly isolated B cells from the heterozygous mice showed a substantial reduction in store-operated Ca2+ entry compared to that in T and B cells from wild-type controls; this was apparent when the cells were treated with thapsigargin to induce passive depletion of ER Ca2+ stores, as well as when their T-cell receptors or B-cell antigen receptors were cross-linked with anti-CD3 or anti-IgM, respectively (Fig. 2B). However, haploinsufficiency of ORAI1 in the C57BL/6 background did not result in significant changes in T- and B-cell subsets, as judged by staining for appropriate surface markers (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Store-operated Ca2+ influx is impaired in fibroblasts and T and B cells from C57BL/6 background ORAI1-deficient mice. (A) Store-operated Ca2+ influx in wild-type (WT), Orai1 heterozygous (+/−), and Orai1 homozygous null (−/−) MEF cells stimulated with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) in Ringer solution containing the indicated Ca2+ concentrations (mM). (B) Heterozygous Orai1+/− B and T cells show a substantial decrease in store-operated Ca2+ influx. (Left) Store-operated Ca2+ influx in naïve B cells in wild-type littermates (WT) and heterozygous Orai1+/− mice (+/−) in response to TG (1 μM) or anti-IgM in the presence of indicated [Ca2+]o (mM). (Right) Store-operated Ca2+ influx in response to TG (1 μM) or anti-CD3 cross-linking with goat anti-hamster IgG (GαH) in differentiated CD4+ T cells (THN) from wild-type littermates (WT) and heterozygous Orai1+/− mice in the presence of indicated [Ca2+]o. (C) Decrease in store-operated Ca2+ influx in wild-type (WT) or Orai1−/− (KO) B and T cells obtained from fetal liver chimeras. Peripheral B and T cells from reconstituted mice were treated with TG (1 μM). Left, B cells (B); middle, differentiated CD4+ T cells (THN); right, differentiated CD8+ T cells (cytolytic T cells [CTLs]). For all experiments, Ca2+ influx was analyzed by single-cell video imaging of fura-2-labeled cells. The traces show the average results for more than 100 cells analyzed in each experiment. All the data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. α, anti. In all panels, the bars above the traces indicate the point at which the cell perfusion medium was changed and the duration of time that the indicated substance, stimulus, or [Ca2+]o was present.

To determine the effect of a complete absence of ORAI1 in lymphocytes, we examined store-operated Ca2+ entry in Orai1−/− T and B cells obtained from fetal liver chimeras (Fig. 2C). Fetal liver cells from wild-type or Orai1−/− embryos in the C57BL/6 background were injected into syngeneic Rag2−/− γc−/− mice that had been sublethally irradiated (7.5 Gy). Irradiated Rag2−/− γc−/− mice did not show any residual host-derived CD4 and CD8 single-positive cells in the periphery (two mice analyzed; data not shown); hence, all the CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive thymocytes originated from donor-derived fetal liver cells. Six weeks later, lymphocytes were isolated from thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes of the resulting chimeric mice. The mice did not display any obvious defects in T- and B-cell subsets or development (data not shown). However, ORAI1-deficient splenic B cells displayed a severe decrease in store-operated Ca2+ entry in response to thapsigargin, although a degree of residual influx remained (Fig. 2C, left panel). A similar severe but incomplete loss of store-operated Ca2+ influx was observed in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells differentiated for 6 days under THN conditions or in cytolytic T cells, respectively (Fig. 2C, middle and right panels).

Together these data indicate that loss of ORAI1 has a strong and detectable effect on store-operated Ca2+ entry in fibroblasts and lymphocytes. This finding is at variance with the results of a previous study, which reported that T cells from mice bearing a gene-trap insertion in the first exon of the Orai1 gene had no perceptible defect in store-operated Ca2+ entry (46). A potential explanation for this discrepancy is provided in a later section.

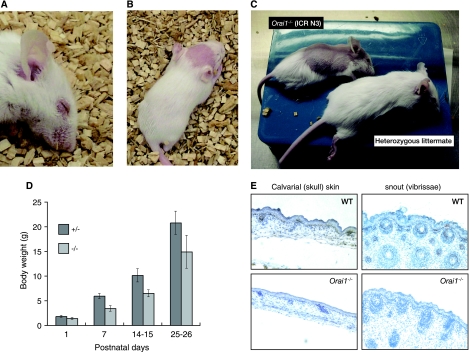

Hair loss and skin phenotypes of Orai1−/− mice.

To rescue the perinatal lethality of Orai1−/− mice, we backcrossed the mice to the outbred ICR mouse strain. After three generations of crossing to ICR mice, Orai1−/− mice in the mixed ICR genetic background were born at near-Mendelian ratios; about half survived past 1 day, and about a third survived for more than 90 days. As a result, we were able to compare the phenotypes of the surviving ORAI1-null mice with those of their wild-type and heterozygous littermates. Given the completely penetrant perinatal lethality seen in the C57BL/6 background, the surviving mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice were remarkably normal, and they lived past 90 days, although occasional mice were observed to have seizures. Consistent phenotypic features of the homozygous Orai1−/− mice were an obvious irritation of the eyelids (Fig. 3A), sporadic hair loss (Fig. 3B and C), and a smaller-than-normal size (about 25 to 30% smaller than wild-type or heterozygous littermates) (Fig. 3C and D). The eyelid irritation was seen in all Orai1−/− mice to some extent (Fig. 3A), but with variable severity; it was not accompanied by splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, or other obvious autoimmune pathologies and was unaffected by changing the conditions of housing (using nonallergenic paper bedding in the cages, for instance).

FIG. 3.

Epidermal defects in Orai1−/− mice. (A) Blepharitis (eye irritation) in an Orai1−/− mouse. The blepharitis is even more obvious by 60 days of age, with swelling and reddening of eyelids. (B, C) Hair loss in Orai1−/− mice (15 and 25 days of age, respectively). Hair loss is variable, appearing as completely denuded patches, most frequently on the head. In some cases, the hair loss is progressive, spreading from the head to affect, eventually, a large part of the dorsal skin (C, upper animal) before slowly regrowing to near-normal appearance. (D) Graph of body weights of heterozygous Orai1+/− and homozygous mutant Orai1−/− mice as a function of age. Shown are the averages and standard deviations (error bars) of the weights of 13 Orai1+/− and 8 Orai1−/− mice from a single litter. Results are representative of three litters examined. Orai1−/− mice are consistently 25 to 30% smaller than their heterozygous littermates. (E) Immunohistochemistry of skin from wild-type (WT) and Orai1−/− neonates using ORAI1 antiserum. Tissues were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Tissue section thickness, 6 μm; ×200, original magnification. Brown (peroxidase) reaction product shows ORAI1 immunoreactivity to be present in keratinocytes in normal skin (upper panels) but absent in Orai1−/− mice. Skin from Orai1−/− mice is thinner, with lower cell density and narrower follicles.

The hair loss phenotype we observed in Orai1−/− mice resembled the cyclical alopecia described in mice with a keratinocyte-specific deletion of the Cnb1 gene (encoding the regulatory subunit of calcineurin, calcineurin B1) (32). Some (but not all) null mice showed a patchy pattern of hair loss, concentrated on the occipital region of the skin of the skull (calvaria; Fig. 3B). Although hair loss can occur from a variety of trivial causes, it followed genotype closely in these mice: heterozygous littermates were unaffected (Fig. 3C). The affected mouse in Fig. 3C initially showed a progressive spread of the hairless region toward the tail, and then (as seen in the figure) a partial regrowth of hair in the affected region. With increasing age, hairless patches disappeared and the skin returned to near normal, although hair generally continued to be sparse. The denuded regions were not noticeably irritated (reddened or swollen).

Histological examination of skin sections taken from calvaria and snout showed that Orai1−/− mice have thinner skin, with fewer, more-elongated keratinocytes (Fig. 3E). Consistent with the shorter and thinner vibrissae of ORAI1-null mice (Fig. 3B), vibrissal follicles were smaller and less well-developed (Fig. 3E, compare top and bottom panels), although their number and pattern were normal. The sections were stained with an antiserum to a peptide at the C terminus of ORAI1, confirming the presence of ORAI1 in keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis of wild-type mice (Fig. 3E, top left). There was no detectable staining in skin sections from Orai1−/− mice, confirming that exon 1 deletion leads to loss of protein expression (Fig. 3E, bottom panels).

Alterations in lymphocyte function in Orai1−/− mice in the mixed ICR background.

Because of the prolonged survival of a substantial fraction of mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice, we were able to reexamine T- and B-cell function more thoroughly using lymphocytes from these mice. T- and B-cell subsets and development appeared normal in the mice (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material; data not shown), as did the numbers and function of Tregs (defined as CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ cells) in thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes (data not shown). When tested in in vitro suppression assays, Orai1−/− Tregs were capable of suppressing the proliferation of wild-type CD4+ CD25− responder cells, and conversely, Orai1−/− CD4+ CD25− T cells were capable of being suppressed by wild-type Tregs (data not shown).

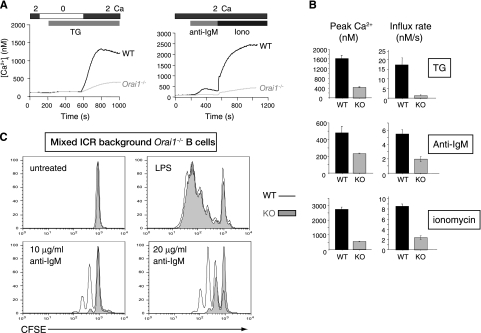

Despite showing no obvious developmental anomalies, B220+ B cells from the mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice showed a substantial decrease in store-operated Ca2+ influx compared to that in B cells from their littermate controls (Fig. 4). The decrease was apparent in thapsigargin-treated B cells, in B cells stimulated through their B-cell receptor with anti-IgM, and in B cells maximally stimulated with ionomycin at concentrations that deplete ER Ca2+ stores and thereby open CRAC channels in the plasma membrane (34) (Fig. 4A; quantified in Fig. 4B). Furthermore, ORAI1-deficient B cells derived either from fetal liver chimeras or from mice in the mixed ICR background showed a substantial decrease, but not a complete impairment, of proliferation induced by cross-linking with anti-IgM (Fig. 4C and data not shown). In both cases, proliferation in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was unaffected (Fig. 4C, far right panels), as expected given that LPS signals through TLR4 receptors and the MyD88-NFκB pathway (19, 22).

FIG. 4.

Substantial decrease in store-operated Ca2+ influx and proliferation of ORAI1-deficient B cells in the mixed ICR genetic background. (A) Store-operated Ca2+ influx in naïve B cells in wild-type littermates (WT) and Orai1−/− mice in response to thapsigargin (TG) treatment (1 μM) (left) or 10 μg/ml anti-IgM followed by ionomycin (iono; 1 μM) (right). Graphs are representative of the results of at least four independent experiments, and each trace shows the average of at least 100 individual cell responses. In both panels, the bars above the traces indicate the point at which the cell perfusion medium was changed and the duration of time that the indicated substance, stimulus, or [Ca2+]o was present. (B) Averaged [Ca2+]i peaks and initial rates of [Ca2+]i increase (influx rate) from four independent experiments such as those shown in panel A. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means (SEMs). WT, wild-type littermates; KO, Orai1−/− mice. (C) ORAI1-deficient B cells show a decrease in IgM-induced, but not LPS-induced, proliferation. Purified B cells from the mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with various concentrations of anti-IgM or 20 μg/ml of LPS for 48 h. WT, wild-type littermates; KO, Orai1−/− mice.

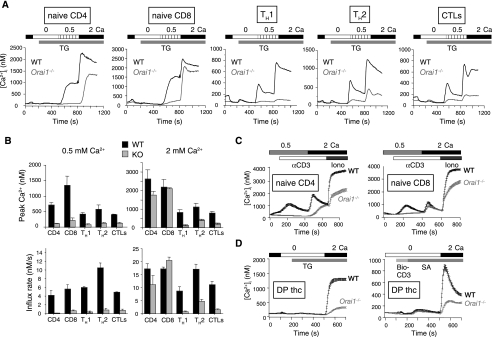

The effect of ORAI1 deficiency on T-cell function was more complex. Naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice showed little or no decrease in thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ influx when the extracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]o) was maintained at slightly above physiological levels (2 mM) but displayed a clear impairment at a lower [Ca2+]o (0.5 mM) (Fig. 5A, two left panels; quantified in Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained when naïve T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 (Fig. 5C). Consistent with these findings, ORAI1-deficient naïve T cells showed normal proliferation in standard culture medium in response to stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs (data not shown). In contrast, CD4+ T cells that had been differentiated in vitro under TH1 or TH2 conditions and CD8+ T cells that had been differentiated in vitro to induce cytolytic function showed substantial impairment of thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ influx at either 0.5 mM or 2 mM [Ca2+]o (Fig. 5A, three right panels). The Ca2+ influx defect was most apparent in TH1 cells, followed by cytolytic T cells and then TH2 cells (see quantification of peak Ca2+ levels and apparent influx rates in Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Naïve ORAI1-deficient T cells in the mixed ICR genetic background show a lesser impairment of store-operated Ca2+ influx than differentiated T cells. (A) Store-operated Ca2+ entry in T cells from wild-type littermates (WT) and Orai1−/− mice. Purified naïve or differentiated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were treated with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) in the presence of 0.5 or 2 mM [Ca2+]o as indicated. Orai1−/− naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells show only a partial decrease or almost no decrease of TG-induced Ca2+ influx in the presence of 2 mM [Ca2+]o. Graphs represent the results for an average of at least 100 cells. Each trace is representative of the results of at least four independent experiments. CTLs, CD8+ cytolytic T cells. In all panels, the bars above the traces indicate the point at which the cell perfusion medium was changed and the duration of time that the indicated substance, stimulus, or [Ca2+]o was present. (B) Averaged [Ca2+]i peaks and initial rates of [Ca2+]i increase (influx rate) from four independent experiments such as those in shown in panel A. Error bars indicate SEMs. WT, wild-type littermates; KO, Orai1−/− mice. Shown are responses in the presence of either 0.5 mM or 2 mM [Ca2+]o. (C) Store-operated Ca2+ influx in naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from wild-type littermates (WT) and Orai1−/− mice, induced by cross-linking biotinylated anti-CD3 with streptavidin and followed by addition of ionomycin (iono; 1 μM). Graphs are representative of the results of at least four independent experiments. Each trace shows averages and standard errors of at least 100 individual cell responses. α, anti. (D) Store-operated Ca2+ influx in CD4+ CD8+ DP thymocytes (thc) from wild-type littermates (WT) and Orai1−/− mice, induced with TG or by cross-linking biotinylated anti-CD3 (bio-CD3) with streptavidin (SA). Graphs are representative of the results of at least three independent experiments. Each trace shows averages and standard errors of at least 100 individual cell responses.

Ca2+ influx is important for cell motility and positive selection during T-cell development (3). Given the surprising fact that T-cell development was normal in Orai1−/− mice, we examined Ca2+ influx in CD4+ CD8+ DP thymocytes. ORAI1-deficient DP thymocytes showed a substantial decrease of Ca2+ influx elicited by thapsigargin treatment or cross-linking with anti-CD3, but some residual Ca2+ influx remained (Fig. 5D).

Store-operated Ca2+ entry via CRAC channels has also been well characterized in mast cells (20, 21). We derived mast cells from bone marrow cells of mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice. Consistent with the results of a previous report (46), ORAI1-deficient mast cells showed a substantial decrease of store-operated Ca2+ influx in response to thapsigargin (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

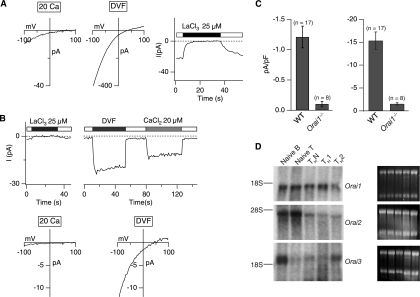

Residual ICRAC-like current in ORAI1-deficient T cells.

We examined the electrophysiological properties of ICRAC in ORAI1-deficient THN cells. In normal mouse T cells, the properties of ICRAC (Fig. 6A) are very similar to those previously documented for human T cells (16, 24, 39): currents in a 20 mM [Ca2+]o, as well as in DVF medium, show inwardly rectifying CRAC-like current-voltage curves with reversal potentials similar to those observed previously in Jurkat T cells; the current is blocked by La3+, and the amplitude of the Na+ current in DVF medium is reduced by half when 20 μM Ca2+ is added. In contrast to the essentially complete loss of ICRAC observed in Stim1−/− T cells (35), however, Orai1−/− T cells showed a small residual current whose properties were very similar to those of ICRAC (Fig. 6B; quantified in Fig. 6C). These data are consistent with the possibility that ORAI2 and/or ORAI3 contribute to ICRAC in wild-type and Orai1−/− T cells.

FIG. 6.

Severe impairment of ICRAC in differentiated ORAI1-deficient T cells. (A) Current-voltage relations recorded from differentiated CD4+ T cells derived from wild-type mice in the mixed ICR background in a 20 mM [Ca2+]o and DVF solutions. Store depletion by thapsigargin (1 μM) elicits a Ca2+ current (left panels) and monovalent cation current (center panel) with properties resembling ICRAC in wild-type cells (including inhibition by La3+; right panel). (B) Residual CRAC-like current in differentiated CD4+ T cells derived from Orai1−/− mice. (Top) Currents recorded in a 20 mM [Ca2+]o are blocked by La3+ (left), and residual Na+ CRAC currents are blocked by ∼50% with 20 μM Ca2+ (right), similar to the 50% inhibitory concentration of Ca2+ inhibition in Jurkat T cells. (Bottom) Current-voltage relation in a 20 mM [Ca2+]o and DVF solutions from differentiated CD4+ T cells derived from Orai1−/− mice. Orai1−/− T cells show significant decrease of ICRAC in comparison to the level in wild-type T cells in panel A. In both panels, the bars above the traces indicate the point at which the cell perfusion medium was changed and the duration of time that the indicated substance, stimulus, or [Ca2+]o was present. (C) Summary of peak current densities recorded under the indicated conditions. Error bars represent SEMs. “n” indicates the number of cells analyzed. (D) Results of Northern analysis of Orai transcripts in wild-type naïve B and T cells and differentiated T cells. An amount of 15 μg of total RNA was loaded in each sample. The gels on the right show corresponding 18S and 28S RNA bands as a loading control.

To address this possibility, we evaluated the steady-state transcript levels of all three Orai family members in wild-type T and B cells by Northern analysis (Fig. 6D). As shown previously, Orai1 transcripts are expressed ubiquitously in all cell types examined (15) (Fig. 6D, top panel), whereas Orai2 transcripts were high specifically in naïve T cells and in freshly isolated B cells (middle panel) and Orai3 transcripts were present in the highest amounts in B cells (bottom panel). These findings are consistent with the fact that loss of ORAI1 causes the least impairment of store-operated Ca2+ influx in naïve T cells, which express the highest amount of Orai2 mRNA, and the greatest impairment in TH1 cells, which express the least amounts of Orai2 and Orai3 mRNA (Fig. 6A and B).

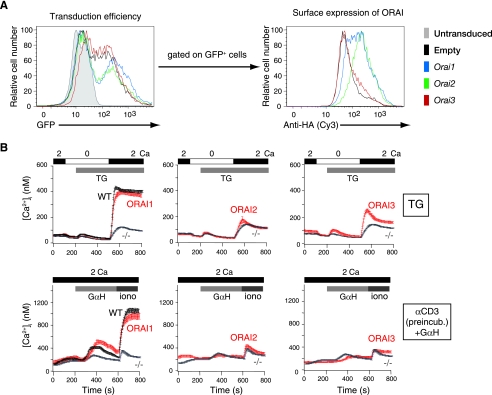

Reconstitution with ORAI1 rescues the defect in store-operated Ca2+ entry in ORAI1-deficient T cells, whereas reconstitution with ORAI2 does not.

Together, these results suggested that although ORAI1 was clearly predominant, ORAI2 and ORAI3 might also contribute to store-operated Ca2+ entry in wild-type and Orai1−/− T cells. To test this hypothesis, we asked whether ORAI2 or ORAI3 could substitute acutely for ORAI1 and increase Ca2+ influx when used to reconstitute Orai1−/− THN cells. To eliminate potential complications arising from a mixed genetic background, we performed the experiments with Orai1−/− T cells in a pure C57BL/6 genetic background derived from fetal liver chimeras as described above.

CD4+ T cells were purified from fetal liver chimeras as described in Fig. 2. They were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in THN conditions and retrovirally reconstituted to express ORAI1, ORAI2, or ORAI3 (Fig. 7). Reconstitution was performed by infecting the differentiating cells with retroviruses encoding modified versions of the ORAI proteins bearing extracellular HA tags introduced into the loop between transmembrane segments 3 and 4 and also bearing an IRES-GFP cassette (15, 38). As a result, the efficiency of retroviral infection and surface expression of the tagged ORAI protein could be monitored independently by flow cytometry of GFP expression and staining of unpermeabilized cells with anti-HA, respectively (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

ORAI1 reconstitutes store-operated Ca2+ entry and cytokine production in ORAI1-deficient T cells, whereas ORAI2 does not. (A) Retroviral expression of exogenous HA-tagged ORAI proteins in differentiated Orai1−/− T cells using retroviral vectors containing an IRES-GFP cassette. Efficiency of retroviral transduction was monitored by measuring GFP expression (left). Surface expression of the HA-ORAI proteins in the GFP+ cells was assessed by staining unpermeabilized cells with an anti-HA antibody (right). (B) Ca2+ influx in response to treatment with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) (top panels) or anti-CD3 cross-linking with goat anti-hamster IgG (+GαH) (bottom panels) in THN cells from wild-type littermates (WT) or Orai1−/− mice (−/−), reconstituted by retroviral transduction with empty retroviral vector (WT and −/−) or HA-tagged ORAI1, ORAI2, or ORAI3. Only GFP+ cells were analyzed. Data are representative of the results of two independent experiments. α, anti; preincub., preincubation. In all panels, the bars above the traces indicate the point at which the cell perfusion medium was changed and the duration of time that the indicated substance, stimulus, or [Ca2+]o was present.

Although GFP expression was approximately equivalent in all cases (Fig. 7A, left panel), the rank order of surface expression of the HA-tagged ORAI proteins was ORAI2 > ORAI1 [tmt] ORAI3 (right panel). The cell populations were treated with thapsigargin or stimulated through the T-cell receptor by anti-CD3 cross-linking to induce Ca2+ store depletion, and store-operated Ca2+ entry was measured in GFP-positive (GFP+) cells by single-cell video imaging (Fig. 7B). The results showed that reconstitution with ORAI1 restored store-operated Ca2+ influx in ORAI1-expressing GFP+ cells to the levels observed in wild-type cells reconstituted with empty vector, whereas reconstitution with ORAI2 had no effect, even though this protein was expressed at levels comparable to or higher than the levels of expression of ORAI1 (Fig. 7A, right, and B). Although ORAI3 was very poorly expressed at the cell surface, reconstitution with ORAI3 caused a marginal increase in store-operated Ca2+ entry that was more apparent after thapsigargin stimulation than upon cross-linking with anti-CD3 (Fig. 7B).

We conclude that ORAI1 can reconstitute Orai1−/− THN cells but ORAI2 is ineffective: that is, a further increase in the amount of ORAI2 present at the surface of Orai1−/− T cells does not increase the coupling of this acutely introduced protein to the pathway of store-operated Ca2+ entry or cytokine production. Because of the low expression of ORAI3 at the cell surface in our current experiments, we cannot at present come to any conclusion about ORAI3. However, the data presented here are reminiscent of those we previously obtained by reconstituting fibroblasts from ORAI1 (R91W) SCID patient cells with ORAI family proteins: ORAI2 was unable to reconstitute store-operated Ca2+ entry, whereas reconstitution with ORAI3 had a small but measurable effect (15).

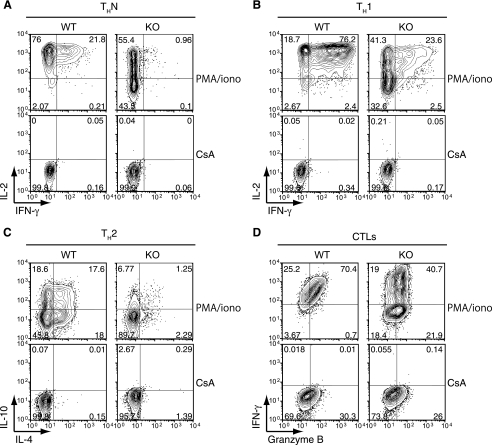

Impaired production of multiple cytokines by different subsets of ORAI1-deficient T cells.

We performed a systematic comparison of cytokine production by wild-type and Orai1−/− T cells in the mixed ICR background (Fig. 8). To measure the effect of ORAI1 deficiency on cytokine production, we differentiated wild-type and Orai1−/− CD4+ T cells in the mixed ICR background for 6 days under THN, TH1, and TH2 conditions. We also differentiated wild-type and Orai1−/− CD8+ T cells for 6 days under conditions that led to the generation of cytolytic T cells. The cells were stimulated for 6 h with PMA and ionomycin and stained for production of the appropriate cytokines (Fig. 8). In every case, inspection of the contour plots shows a substantial decrease in the number of cytokine-producing cells, as well as peak and mean fluorescence intensity of cytokine staining, in Orai1−/− T cells compared to these measures in wild-type T cells (IL-2 and gamma interferon [IFN-γ] for THN and TH1 cells, IL-10 and IL-4 for TH2 cells, and IFN-γ for CD8+ T cells differentiated into cytolytic T cells) (Fig. 8A to D). In contrast, the expression of granzyme B, whose induction is known to be Ca2+ independent, was essentially unaffected (Fig. 8D). Thus, the decrease in store-operated Ca2+ influx is associated, as expected, with a major decrease in cytokine production by all T-cell subsets. However, because outbred mice were used for these experiments, and because genetic variability can have a strong influence on cytokine production, we cannot make a determination from these data as to which cytokines have a stronger or lesser dependence on ORAI1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ influx.

FIG. 8.

Partial impairment of cytokine expression in differentiated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the mixed ICR background Orai1−/− mice. T cells isolated from wild-type littermates (WT) or Orai1−/− mice (KO) were cultured under the indicated conditions for 6 days (see Materials and Methods). The cells were then restimulated with 10 nM PMA and 1 μM ionomycin (PMA/iono), with or without pretreatment with 1 μM cyclosporine A (CsA). Cyclosporine A was kept in the cultures after pretreatment. The percentage of cytokine-expressing cells is indicated in each quadrant. Data are representative of the results of at least three independent experiments. (A) Cells cultured under THN conditions and assessed for IL-2 and IFN-γ expression. (B) Cells cultured under TH1 conditions and assessed for IL-2 and IFN-γ expression. (C) Cells cultured under TH2 conditions and assessed for IL-10 and IL-4 expression. (D) Cytolytic T cells (CTLs) cultured in the presence of 100 U/ml human IL-2 were assessed for IFN-γ and granzyme B expression.

DISCUSSION

We show here that ORAI1 is expressed in several murine tissues, including lymphocytes, muscle, and skin, and that deletion of exon 1 of the Orai1 gene in inbred C57BL/6 mice is associated with loss of ORAI1 protein and perinatal lethality. In contrast, mixed ICR background mice carrying the same mutation display a far less deleterious phenotype which resembles that observed in human SCID patients with a nonfunctional R91W mutation in ORAI1, who also survive after birth but are immunodeficient and fail to thrive (9-12). T and B cells from the mice show a substantial decrease in store-operated Ca2+ influx, as well as functional defects consistent with the primary immunodeficiency observed in the R91W SCID patients, including normal development of B cells but impaired B-cell proliferation and decreased cytokine production by T-cell subsets (9-12). Orai1−/− mice in the mixed ICR background are smaller in size than their wild-type littermates and display a phenotype of thin skin and sporadic hair loss which may correspond in part to the ectodermal dysplasia and anhydrosis observed in the surviving SCID patient with the R91W mutation (9) and in part to the phenotype of “cyclical alopecia” described in mice with keratinocyte-specific deletion of the Cnb1 gene (32). These data confirm the importance of the calcium/calcineurin pathway for normal development of hair follicles and skin (14, 18) and show that modifier genes from the mixed ICR background can ameliorate the perinatal lethality associated with global deficiency of ORAI1.

A previous study by Kinet and colleagues described mice bearing a gene-trap insertion in the first intron of the Orai1 gene (46). These mice resemble the Orai1−/− mice described here in some respects but differ in others. In particular, although the gene-trap mice were much smaller than their wild-type littermates, there was no perinatal lethality if the pups were fostered separately; in contrast, we have consistently observed that the Orai1−/− mice die between days 0.5 and 1.5 under all conditions of care. It is unlikely that the perinatal lethality we observe is due to a secondary mutation in the ES cells used to generate the Orai1−/− mice, since a very similar late embryonic/early postnatal lethality is observed in Stim1−/− mice (2, 35) and in “knock-in” mice in which nucleotide substitutions corresponding to the nonfunctional R91W mutation in human ORAI1 (11) were introduced at the corresponding position (R93) of the murine Orai1 gene (M. Oh-hora, J. Roether, C. A. McCarl, E. D. Lamperti, C. Gelinas, A. Rao, and S. Feske, unpublished data). In addition, the gene-trap mice displayed a pronounced defect in mast cell degranulation but no apparent hair loss. These differences are most readily explained if the Orai1 gene-trap mouse is a hypomorph able to express low levels of correctly spliced Orai1 mRNA in specific tissues, rather than a true null. Hypomorphic phenotypes arising from decreased protein expression are a known hazard of the gene-trap method (www.genetrap.org/tutorials/overview.html). Tissue-specific differences in splicing may also explain why LacZ expression in the gene-trap mice correlated poorly with the pattern of ORAI1 expression observed in wild-type mice by immunohistochemistry. The gene-trap mice showed high amounts of LacZ expression in skeletal muscle, but no expression in skin or lymphocytes, tissues in which ORAI1 expression is clearly detectable by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1 and 3) and which exhibit clear functional deficits resulting from lack of ORAI1 (Fig. 2 to 6 and 8).

Surprisingly, T cells taken directly from the gene-trap mice were reported to have no perceptible defect in store-operated Ca2+ entry (46). This result contrasts with our data both for the human SCID patients (10, 11) and for Orai1−/− mice. In both cases, T cells had a clear defect both in store-operated Ca2+ entry and in the production of multiple cytokines characteristic of all T-cell subsets. However, the above study primarily examined T cells taken directly from the gene-trap animals, which are most likely naïve, and we have shown that naïve T cells have considerably less impairment of store-operated Ca2+ influx than differentiated T cells (see Fig. 5). The study also reported measurements of store-operated Ca2+ influx in physiological concentrations of extracellular free calcium, where the defect in naïve T cells is much less apparent (Fig. 5). These considerations could well explain the difference in T-cell phenotypes between the gene-trap mice and mice with a targeted deletion of Orai1 that are entirely null for expression of ORAI1 protein. Consistent with this hypothesis, T cells taken directly from the gene-trap mice showed the expected decrease in IL-2 and IFN-γ production (46).

Unlike Stim1−/− T cells, which show a profound defect in cytokine production (35), Orai1−/− cells still express some IL-2, IFN-γ, and other cytokines. However, inspection of the contour plots shows that the peak fluorescent intensity is about 50 times less than that of wild-type cells (Fig. 8). The presence of some cytokines may reflect the fact that, unlike Stim1−/− T cells, Orai1−/− T cells retain some degree of sustained Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2, 5, and 7). Presumably, this residual sustained Ca2+ influx suffices to support some level of cytokine production by Orai1−/− T cells.

The residual CRAC-like current observed in Orai1−/− T cells (Fig. 6) is consistent with the possibility that ORAI2 and/or ORAI3 contributes to ICRAC in T cells. We tested this possibility by retroviral reintroduction of extracellularly HA-tagged ORAI1 and ORAI2, which we showed were expressed at equivalent levels on the surface of the reconstituted cells. We found that, whereas reconstitution with ORAI1 could restore store-operated Ca2+ entry to Orai1−/− T cells, reconstitution with ORAI2 was ineffective (Fig. 7). Similarly, reconstituting fibroblasts from ORAI1 (R91W) SCID patient cells with ORAI1 restored store-operated Ca2+ entry but reconstitution with ORAI2 had no effect (15). We conclude that if ORAI2 compensates for loss of ORAI1 as previously suggested (46), it must do so during development, since this protein is apparently unable to couple effectively to the mechanism of store-operated Ca2+ entry when acutely introduced into Orai1−/− T cells. One potential hypothesis is that differentiation results not only in downregulation of Orai2 itself but also in parallel downregulation of genes encoding other proteins required to couple ORAI2 to the store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway. Alternatively, ORAI3 could be the compensating ORAI protein, as we previously suggested based on results from the introduction of ORAI3 into SCID patient fibroblasts (15); given the recent data showing that ORAI3 can be gated simply by applying 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (5a, 41a, 50a), the presence of functional ORAI3 in T cells and other cell types of Orai1−/− mice could be tested by using this compound. Further studies will be needed to understand the distinct roles of ORAI proteins at different developmental stages and in different cell types.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hui Hu, Mark Sundrud, and Christine Patterson (Rajewsky lab) for help with experiments involving the generation of fetal liver chimeras, analysis of Tregs, and analysis of B-cell development, respectively. We also thank Jeffery L. Kutok from the specialized histopathology core at the Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center for his help with optimizing conditions for immunohistochemistry.

This work was supported by NIH and JDRF grants to A.R., an NIH grant and a March of Dimes Foundation grant to S.F., and NIH grants to M.P. and K.R. M.O. and Y.S. were supported by research fellowships from the Uehara Memorial Foundation.

P.G.H., S.F. and A.R. declare that they have competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 June 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansel, K. M., R. J. Greenwald, S. Agarwal, C. H. Bassing, S. Monticelli, J. Interlandi, I. M. Djuretic, D. U. Lee, A. H. Sharpe, F. W. Alt, and A. Rao. 2004. Deletion of a conserved Il4 silencer impairs T helper type 1-mediated immunity. Nat. Immunol. 51251-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, Y., K. Nishida, Y. Fujii, T. Hirano, M. Hikida, and T. Kurosaki. 2008. Essential function for the calcium sensor STIM1 in mast cell activation and anaphylactic responses. Nat. Immunol. 981-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhakta, N. R., D. Y. Oh, and R. S. Lewis. 2005. Calcium oscillations regulate thymocyte motility during positive selection in the three-dimensional thymic environment. Nat. Immunol. 6143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandman, O., J. Liou, W. S. Park, and T. Meyer. 2007. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) levels. Cell 1311327-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carafoli, E. 2003. The calcium-signalling saga: tap water and protein crystals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.DeHaven, W. I., J. T. Smyth, R. R. Boyles, G. S. Bird, and J. W. Putney, Jr. 2008. Complex actions of 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate on store-operated calcium entry. J. Biol. Chem. 28319265-19273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeHaven, W. I., J. T. Smyth, R. R. Boyles, and J. W. Putney, Jr. 2007. Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 28217548-17556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanger, C. M., M. Hoth, G. R. Crabtree, and R. S. Lewis. 1995. Characterization of T cell mutants with defects in capacitative calcium entry: genetic evidence for the physiological roles of CRAC channels. J. Cell Biol. 131655-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feske, S. 2007. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7690-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feske, S., R. Draeger, H. H. Peter, K. Eichmann, and A. Rao. 2000. The duration of nuclear residence of NFAT determines the pattern of cytokine expression in human SCID T cells. J. Immunol. 165297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feske, S., J. Giltnane, R. Dolmetsch, L. M. Staudt, and A. Rao. 2001. Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2316-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feske, S., Y. Gwack, M. Prakriya, S. Srikanth, S. H. Puppel, B. Tanasa, P. G. Hogan, R. S. Lewis, M. Daly, and A. Rao. 2006. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feske, S., J. M. Muller, D. Graf, R. A. Kroczek, R. Drager, C. Niemeyer, P. A. Baeuerle, H. H. Peter, and M. Schlesier. 1996. Severe combined immunodeficiency due to defective binding of the nuclear factor of activated T cells in T lymphocytes of two male siblings. Eur. J. Immunol. 262119-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feske, S., M. Prakriya, A. Rao, and R. S. Lewis. 2005. A severe defect in CRAC Ca2+ channel activation and altered K+ channel gating in T cells from immunodeficient patients. J. Exp. Med. 202651-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs, E., and V. Horsley. 2008. More than one way to skin. Genes Dev. 22976-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwack, Y., S. Srikanth, S. Feske, F. Cruz-Guilloty, M. Oh-hora, D. S. Neems, P. G. Hogan, and A. Rao. 2007. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 28216232-16243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermosura, M. C., M. K. Monteilh-Zoller, A. M. Scharenberg, R. Penner, and A. Fleig. 2002. Dissociation of the store-operated calcium current I(CRAC) and the Mg-nucleotide-regulated metal ion current MagNuM. J. Physiol. 539445-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogan, P. G., and A. Rao. 2007. Dissecting ICRAC, a store-operated calcium current. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horsley, V., A. O. Aliprantis, L. Polak, L. H. Glimcher, and E. Fuchs. 2008. NFATc1 balances quiescence and proliferation of skin stem cells. Cell 132299-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoshino, K., O. Takeuchi, T. Kawai, H. Sanjo, T. Ogawa, Y. Takeda, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol. 1623749-3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoth, M., and R. Penner. 1993. Calcium release-activated calcium current in rat mast cells. J. Physiol. 465359-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoth, M., and R. Penner. 1992. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature 355353-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawai, T., O. Adachi, T. Ogawa, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 11115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Deist, F., C. Hivroz, M. Partiseti, C. Thomas, H. A. Buc, M. Oleastro, B. Belohradsky, D. Choquet, and A. Fischer. 1995. A primary T-cell immunodeficiency associated with defective transmembrane calcium influx. Blood 851053-1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lepple-Wienhues, A., and M. D. Cahalan. 1996. Conductance and permeation of monovalent cations through depletion-activated Ca2+ channels (ICRAC) in Jurkat T cells. Biophys. J. 71787-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis, R. S. 2001. Calcium signaling mechanisms in T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19497-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis, R. S. 2007. The molecular choreography of a store-operated calcium channel. Nature 446284-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis, R. S., and M. D. Cahalan. 1989. Mitogen-induced oscillations of cytosolic Ca2+ and transmembrane Ca2+ current in human leukemic T cells. Cell Regul. 199-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liou, J., M. Fivaz, T. Inoue, and T. Meyer. 2007. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1049301-9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liou, J., M. L. Kim, W. D. Heo, J. T. Jones, J. W. Myers, J. E. Ferrell, Jr., and T. Meyer. 2005. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 151235-1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lis, A., C. Peinelt, A. Beck, S. Parvez, M. Monteilh-Zoller, A. Fleig, and R. Penner. 2007. CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr. Biol. 17794-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luik, R. M., M. M. Wu, J. Buchanan, and R. S. Lewis. 2006. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J. Cell Biol. 174815-825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mammucari, C., A. Tommasi di Vignano, A. A. Sharov, J. Neilson, M. C. Havrda, D. R. Roop, V. A. Botchkarev, G. R. Crabtree, and G. P. Dotto. 2005. Integration of Notch 1 and calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathways in keratinocyte growth and differentiation control. Dev. Cell 8665-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mignen, O., J. L. Thompson, and T. J. Shuttleworth. 2007. Orai1 subunit stoichiometry of the mammalian CRAC channel pore. J. Physiol. 586419-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan, A. J., and R. Jacob. 1994. Ionomycin enhances Ca2+ influx by stimulating store-regulated cation entry and not by a direct action at the plasma membrane. Biochem. J. 300665-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh-hora, M., M. Yamashita, P. G. Hogan, S. Sharma, E. Lamperti, W. Chung, M. Prakriya, S. Feske, and A. Rao. 2008. Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 9432-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Partiseti, M., F. Le Deist, C. Hivroz, A. Fischer, H. Korn, and D. Choquet. 1994. The calcium current activated by T cell receptor and store depletion in human lymphocytes is absent in a primary immunodeficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 26932327-32335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peinelt, C., M. Vig, D. L. Koomoa, A. Beck, M. J. Nadler, M. Koblan-Huberson, A. Lis, A. Fleig, R. Penner, and J. P. Kinet. 2006. Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1). Nat. Cell Biol. 8771-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prakriya, M., S. Feske, Y. Gwack, S. Srikanth, A. Rao, and P. G. Hogan. 2006. Orai1 is an essential pore subunit of the CRAC channel. Nature 443230-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prakriya, M., and R. S. Lewis. 2002. Separation and characterization of currents through store-operated CRAC channels and Mg2+-inhibited cation (MIC) channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 119487-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Putney, J. W., Jr. 2007. New molecular players in capacitative Ca2+ entry. J. Cell Sci. 1201959-1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roos, J., P. J. DiGregorio, A. V. Yeromin, K. Ohlsen, M. Lioudyno, S. Zhang, O. Safrina, J. A. Kozak, S. L. Wagner, M. D. Cahalan, G. Velicelebi, and K. A. Stauderman. 2005. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 169435-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41a.Schindl, R., J. Bergsmann, I. Frischauf, I. Derler, M. Fahrner, M. Muik, R. Fritsch, K. Groschner, and C. Romanin. 2008. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate alters selectivity of Orai3 channels by increasing their pore size. J. Biol. Chem. 28320261-20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soboloff, J., M. A. Spassova, X. D. Tang, T. Hewavitharana, W. Xu, and D. L. Gill. 2006. Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 28120661-20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solymar, D. C., S. Agarwal, C. H. Bassing, F. W. Alt, and A. Rao. 2002. A 3′ enhancer in the IL-4 gene regulates cytokine production by Th2 cells and mast cells. Immunity 1741-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stiber, J., A. Hawkins, Z. S. Zhang, S. Wang, J. Burch, V. Graham, C. C. Ward, M. Seth, E. Finch, N. Malouf, R. S. Williams, J. P. Eu, and P. Rosenberg. 2008. STIM1 signalling controls store-operated calcium entry required for development and contractile function in skeletal muscle. Nat. Cell Biol. 10688-697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vig, M., A. Beck, J. M. Billingsley, A. Lis, S. Parvez, C. Peinelt, D. L. Koomoa, J. Soboloff, D. L. Gill, A. Fleig, J. P. Kinet, and R. Penner. 2006. CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr. Biol. 162073-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vig, M., W. I. Dehaven, G. S. Bird, J. M. Billingsley, H. Wang, P. E. Rao, A. B. Hutchings, M. H. Jouvin, J. W. Putney, and J. P. Kinet. 2008. Defective mast cell effector functions in mice lacking the CRACM1 pore subunit of store-operated calcium release-activated calcium channels. Nat. Immunol. 989-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vig, M., C. Peinelt, A. Beck, D. L. Koomoa, D. Rabah, M. Koblan-Huberson, S. Kraft, H. Turner, A. Fleig, R. Penner, and J. P. Kinet. 2006. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 3121220-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, M. M., J. Buchanan, R. M. Luik, and R. S. Lewis. 2006. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 174803-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu, P., J. Lu, Z. Li, X. Yu, L. Chen, and T. Xu. 2006. Aggregation of STIM1 underneath the plasma membrane induces clustering of Orai1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350969-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeromin, A. V., S. L. Zhang, W. Jiang, Y. Yu, O. Safrina, and M. D. Cahalan. 2006. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature 443226-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50a.Zhang, S. L., J. A. Kozak, W. Jiwang, A. V. Yeromin, J. Chen, Y. Yu, A. Penna, W. Shen, V. Chi, and M. D. Cahalan. 2008. Store-dependent and -independent modes regulating Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity of human Orai1 and Orai3. J. Biol. Chem. 28317662-17671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, S. L., A. V. Yeromin, X. H. Zhang, Y. Yu, O. Safrina, A. Penna, J. Roos, K. A. Stauderman, and M. D. Cahalan. 2006. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1039357-9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, S. L., Y. Yu, J. Roos, J. A. Kozak, T. J. Deerinck, M. H. Ellisman, K. A. Stauderman, and M. D. Cahalan. 2005. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature 437902-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zweifach, A., and R. S. Lewis. 1993. Mitogen-regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 906295-6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.