Abstract

Resistin has been linked to components of the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia. We hypothesized that resistin deficiency would reverse hyperlipidemia in genetic obesity. C57Bl/6J mice lacking resistin [resistin knockout (RKO)] had similar body weight and fat as wild-type mice when fed standard rodent chow or a high-fat diet. Nonetheless, hepatic steatosis, serum cholesterol, and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion were decreased in diet-induced obese RKO mice. Resistin deficiency exacerbated obesity in ob/ob mice, but hepatic steatosis was drastically attenuated. Moreover, the levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, insulin, and glucose were reduced in ob/ob-RKO mice. The antisteatotic effect of resistin deficiency was related to reductions in the expression of genes involved in hepatic lipogenesis and VLDL export. Together, these results demonstrate a crucial role of resistin in promoting hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidemia in obese mice.

Keywords: adipocytokine, lipoprotein, triglyceride, cholesterol

the metabolic syndrome is characterized by abdominal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and an impairment of glucose metabolism (5, 9). Studies have suggested a link between the altered production and secretion of adipokines and the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome (11, 21). TNF-α is increased in obesity and insulin resistance and, along with other inflammatory mediators, is thought to contribute to dyslipidemia (4). Conversely, adiponectin levels are reduced in obesity and may contribute to insulin resistance, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (14, 40).

Resistin is secreted by adipocytes in rodents and monocytes in humans (38). Peripheral resistin infusion or the transgenic overexpression of resistin impairs insulin action in rodents (26, 32, 34, 37). Conversely, genetic ablation or downregulation of the retn gene improves insulin sensitivity (3, 19, 27). Although resistin has predominantly been studied with regard to its role in impairing insulin action in rodents, increased resistin expression has also been associated with dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in some patients (21, 22). Consistent with a role for resistin in modulating lipid metabolism, resistin induces the accumulation of lipids in skeletal muscle cells by inhibiting β-oxidation (23). Resistin also promotes lipid accumulation in macrophages (30, 41). Furthermore, the adenovirus-mediated overexpression of resistin in mice increased plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and increased hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) production rates (33). Thus we hypothesized that the loss of the retn gene will improve lipid parameters and prevent hyperlipidemia. We examined the role of resistin in lipid metabolism by deleting the retn gene in wild-type (WT) fed a standard rodent chow or high-fat diet and leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (3, 27, 31).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies.

Experimental procedures were in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania and adhered to American Physiological Society Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals. Heterozygote resistin-deficient mice (+/−) on the original 129/C57Bl/6J mixed background (3) were backcrossed onto C57Bl/6J background (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) for nine generations, followed by heterozygote matings to produce WT and resistin-knockout (RKO) mice (27). To generate mice deficient in resistin and leptin, retn (+/−) mice were mated with C57Bl/6J lepob (+/−) mice (Jackson Laboratories), and double heterozygotes were then mated to generate ob/ob, ob/ob-RKO, RKO, and WT (27). The mice were weaned at 3 wk and housed (n = 5/cage) in 12-h:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on 7:00) at an ambient temperature of 22°C. Normal chow (Lab Diet 5001; Richmond, IN) and water were provided ad libitum to one group of mice. Another group was fed a high-fat (45%) diet (No. D12451; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) for 10 wk (31). Body composition was measured using dual emission X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) as previously described (27). To assess VLDL secretion, 14-wk-old male mice were fasted for 4 h (8:00–12:00 h) and received 1 g/kg poloxamer-407 (intraperitoneally) (13, 18). Tail blood was drawn at time 0 and 1 and 4 h later, and serum was prepared for triglyceride measurement (13, 18, 39). The detergent poloxamer-407 inhibits lipases and prevents the clearance of triglycerides, thereby allowing for the assessment of its production (13, 18).

Tissue chemistry.

At 14 wk of age, the mice were euthanized following a 4-h fast using CO2 inhalation between 12:00 and 13:00 h, and blood was obtained via cardiac puncture. Cohorts of mice used for the analysis of serum chemistries and gene expression were different from those used for VLDL secretion. Samples of the liver were rapidly excised, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Serum triglycerides, cholesterol, nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), and β-hydroxybutyric acid were measured using enzymatic assays (Stanbio Labs and Wako Chemicals) (27, 28). Pooled serum samples (125 μl) from each group were analyzed by fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) as described (18, 39). Lipids were extracted from the livers for measurement of triglycerides and cholesterol (13, 18, 39). Serum levels of insulin, resistin, leptin, and adiponectin were measured using enzyme immunoassays (3, 27, 28).

Gene expression.

RNA was extracted from the livers using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following treatment with DNase I, the RNA was reverse transcribed with SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and amplified using Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix with Taqman Assay-on-Demand kits (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using an ABI-Prism 7800 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems) (3, 13, 39). The expression of mRNA levels of lipogenic and lipolytic genes was normalized to 36B4 (3, 13, 39).

Immunoblotting.

Liver samples were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 250 mM mannitol, 0.5% (wt/vol) Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM benzamidine, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride supplemented with a complete protein inhibition cocktail tablet from Roche (Penzberg, Germany). Protein extracts were separated by 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using semidry transfer cells (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After 1 h of blocking with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (TBST) containing 3% (wt/vol) nonfat dried milk, membranes were incubated with a polyclonal antibody against acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC; Millipore), fatty acid synthase (FAS; Cell Signaling), stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1; Cell Signaling), 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA-reductase (HMGCoAR; Cell Signaling), or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Santa Cruz) at 1:1,000 concentration overnight at 4°C, washed three times with TBST, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature, and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). Film autoradiograms were analyzed using laser densitometry and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Protein lysates from the livers of WT, ob/ob, and resistin-deficient mice were also blotted for AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), phosphorylated (p)-AMPK, suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-3, and β-actin as we have previously described (3, 27, 32).

Liver histology.

Liver samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and processed for hematoxylin-eosin staining (13, 39). The slides were examined under brightfield microscopy (Nikon E600), and images were captured using a Cool Snap CF digital camera (BD Biosciences Bioimaging, Rockville, MD).

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SE. The effects of retn deletion in diet-induced obese (DIO) and ob/ob mice were analyzed by ANOVA, and differences between groups were assessed by Fishers paired least significant difference test (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Resistin deficiency decreases hepatic triglyceride secretion and cholesterol in DIO C57Bl/6J mice.

RKO mice exhibited no differences in body weight, adiposity, or serum chemistry compared with those of WT mice on standard rodent chow, in agreement with our previous reports (3, 27). However, hepatic triglyceride content showed a tendency to decrease in chow-fed RKO mice (7.4 ± 1.04 mg/g in RKO vs. 10.5 ± 1.2 mg/g in WT, P = 0.101). Thus we studied the effects of resistin in DIO mice (Fig.- 1, A–L). The high-fat diet increased body weight and fat and serum lipids, glucose, insulin, resistin, and leptin (Fig. 1, A, C, D, I, J, and K), whereas NEFA, β-hydroxybutyric acid, and adiponectin were not altered (Fig. 1, F, G, and L). Resistin deficiency did not affect body weight (Fig. 1A) or total fat content (Fig. 1C) or abdominal fat measured by DEXA (data not shown) in DIO mice. Nonetheless, the hepatic content of triglyceride and not cholesterol was reduced in the absence of resistin (Fig. 2, A and B). Hepatic steatosis was attenuated in DIO RKO mice (Fig. 2, C and D), and the VLDL secretion and HDL fraction of cholesterol were also suppressed (Fig. 2, E and F).

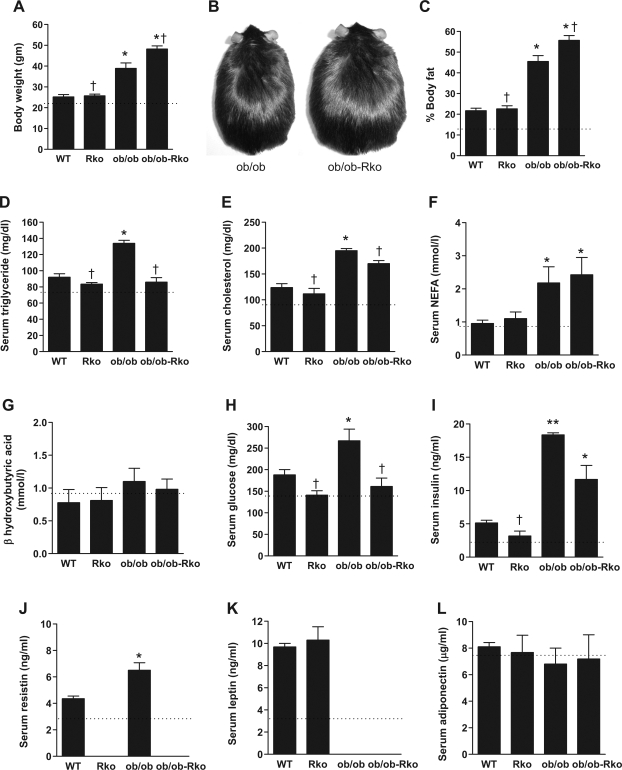

Fig. 1.

Effects of resistin deficiency on body weight (A and B), fat (C), lipids (D–F), ketones (G), glucose (H), insulin (I), resistin (J), leptin (K), and adiponectin (L). Wild-type (WT) and resistin-knockout (RKO) mice were fed a high-fat diet for 10 wk, and ob/ob and ob/ob-RKO mice were fed normal chow. Data are means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.01 vs. WT; **P < 0.001 vs. WT; †P < 0.01 vs. ob/ob. Dotted line denotes level in WT mice on normal chow. NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids.

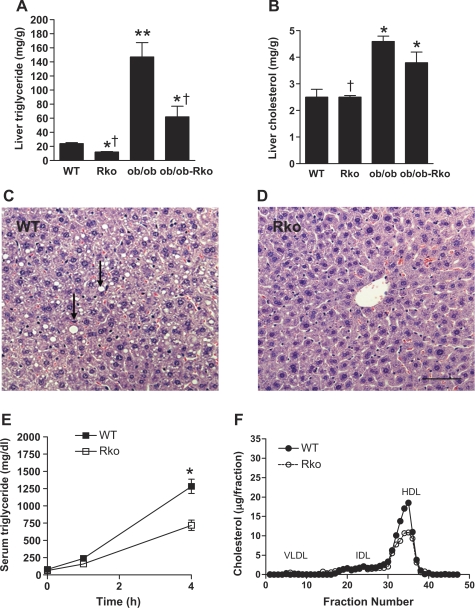

Fig. 2.

Effects of resistin deficiency on liver triglyceride (A) and cholesterol (B) contents. WT and RKO mice were fed a high-fat diet for 10 wk, and ob/ob and ob/ob-RKO mice were fed normal chow. Liver sections from WT (C) and RKO (D) mice on a high-fat diet were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. WT mice developed steatosis (arrows). Scale bar, 100 μm. Serum triglyceride levels after poloxamer treatment (E) and fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) analysis of cholesterol (F) in WT vs. RKO mice on a high-fat diet are shown. Data are means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.01 vs. WT; **P < 0.001 vs. WT; †P < 0.01 vs. ob/ob. VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein; IDL, intermediate density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Resistin deficiency increases obesity but reduces hepatic steatosis and lipid levels in ob/ob mice.

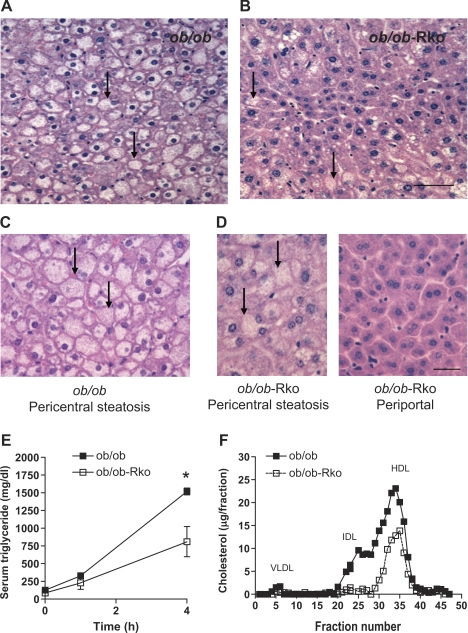

Leptin deficiency results in early onset obesity, hyperinsulinemia, steatosis, and hyperlipidemia (Figs. 1 and 3) (1, 10, 24, 27, 39). As we have previously reported, ob/ob mice lacking resistin were more obese (Fig. 1, A–C) (27). Despite a higher body weight and adiposity, the serum levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, glucose, and insulin were lower in ob/ob-RKO mice (Fig. 1, D, E, H, and I). Triglyceride content in the liver was also drastically reduced in ob/ob-RKO mice (Fig. 2A) in parallel with hepatic steatosis (Fig. 3B). Moreover, resistin deficiency restored normal histology in periportal hepatocytes (Fig. 3, C and D). The secretion of VLDL from the liver (Fig. 3E) and intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL) and HDL cholesterol fractions assessed by FPLC (Fig. 3F) were also decreased in ob/ob-RKO mice.

Fig. 3.

Effects of resistin deficiency on liver histology. ob/ob (A and C) and ob/ob-RKO (B and D) mice were fed normal chow. Arrows denote steatosis. Scale bar, 100 μm. Serum triglyceride levels after poloxamer treatment (E) and FPLC analysis of cholesterol (F) in ob/ob vs. ob/ob-RKO mice are shown. Data are means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.01 vs. ob/ob.

Resistin deficiency suppresses lipogenic gene expression.

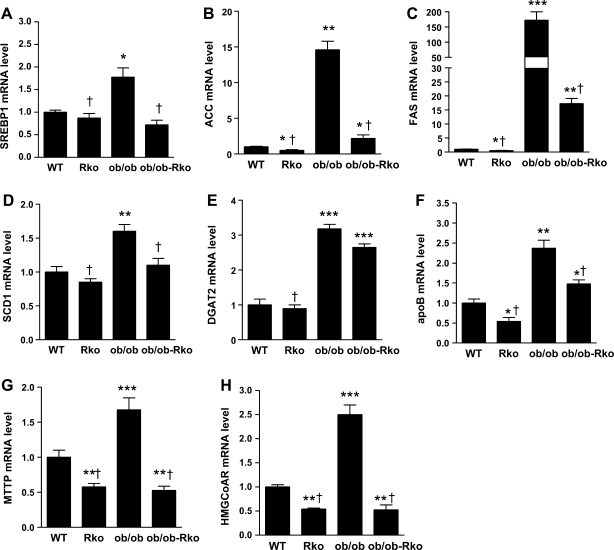

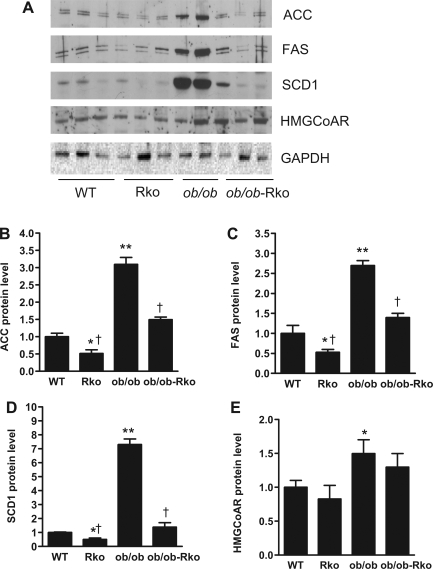

We analyzed the effects of resistin on pathways involved in hepatic lipid metabolism (13, 28, 39). The mRNA levels of sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1, ACC, FAS, SCD1, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase (DGAT)-2, apoB, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP), and HMGCoAR were increased in ob/ob and fell in resistin-deficient ob/ob-RKO mice (Fig. 4, A–H). Likewise, the mRNA levels of ACC, FAS, apoB, MTTP, and HMGCoAR were suppressed in the livers of resistin-deficient DIO mice (Fig. 4, B, C, and F–H). In contrast, the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1a was not altered by the lack of resistin in ob/ob or DIO mice (data not shown). The results of the immunoblotting of liver lysates paralleled the changes in mRNA expression. The protein levels of ACC, FAS, SCD1, and HMGCoAR were higher in ob/ob than in DIO mice (Fig. 5, A–E). Resistin deficiency decreased ACC, FAS, and SCD1 levels in both ob/ob and DIO mice (Fig. 5, A–D).

Fig. 4.

Effects of resistin deficiency on hepatic gene expression (A–F). WT and RKO mice were fed a high-fat diet for 10 wk, and ob/ob and ob/ob-RKO mice were fed normal chow. Data are means ± SE (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 vs. WT; **P < 0.01 vs. WT; ***P < 0.001 vs. WT; †P < 0.001 vs. ob/ob. SREBP, sterol regulated element binding protein; ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; FAS, fatty acid synthase; SCD, stearoyl-CoA desaturase; DGAT, diacylclycerol O-acyltransferase; apoB, apolipoprotein B; MTTP, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; HMGCoAR, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA-reductase.

Fig. 5.

Effects of resistin deficiency on lipogenic proteins in liver. WT and RKO mice were fed a high-fat diet for 10 wk, and ob/ob and ob/ob-RKO mice were fed normal chow (A–E). Data are means ± SE arbitrary densitometric units normalized to GAPDH (n = 3/group). *P < 0.05 vs. WT; **P < 0.01; †P < 0.001 vs. ob/ob.

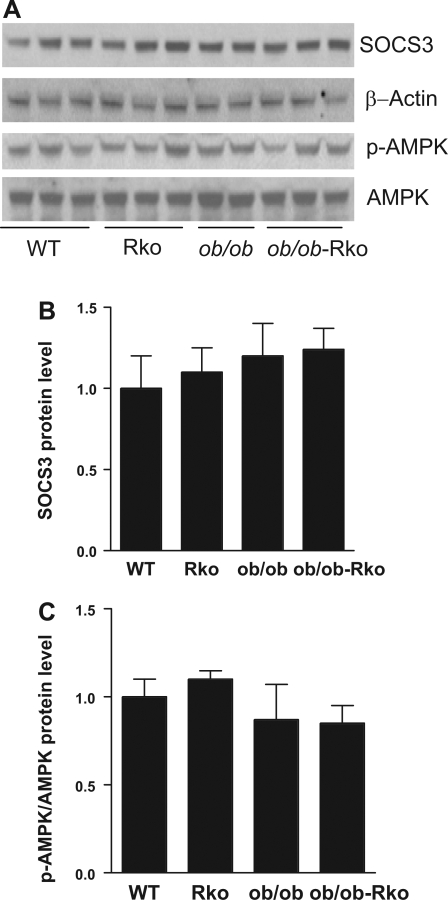

The resistin receptor is unknown, but the ability of resistin to induce insulin resistance under hyperinsulinemic clamp has been associated with the reduced phosphorylation of AMPK and the induction of SOCS-3 (3, 19, 27). However, in the absence of exogenous insulin in the current study, retn deletion did not alter hepatic levels of SOCS-3 and AMPK or the phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 6, A–C).

Fig. 6.

Lack of effect of resistin deficiency on putative mediators of hepatic insulin resistance. WT and RKO mice were fed a high-fat diet for 10 wk, and ob/ob and ob/ob-RKO mice were fed normal chow (A–C). Data are means ± SE arbitrary densitometric units. Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-3 was normalized to β-actin, and phosphorylated (p)-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) was normalized to total AMPK (n = 3/group).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that WT mice exhibit similar body weight as those lacking resistin (3, 27). However, insulin sensitivity is improved in resistin deficiency, resulting in the suppression of hepatic glucose production and increased glucose uptake in peripheral tissues (3, 27). The deletion of retn exacerbates obesity in ob/ob mice by further lowering energy expenditure (27). Studies indicate that resistin decreases body fat by inhibiting adipogenesis (15, 16). In the current study, we compared the effects of resistin deficiency on lipids in DIO and ob/ob mice. In both models, the ablation of retn decreased triglyceride production and serum cholesterol levels and attenuated hepatic steatosis. These effects were more pronounced in ob/ob mice, suggesting that deficiencies of both leptin and resistin have major consequences on lipids. Key lipogenic genes, i.e., SREBP-1, FAS, SCD1, DGAT2, and HMGCoAR, and those involved in VLDL packaging and export, i.e., MTTP and apoB, were suppressed in the livers of resistin-deficient mice. The increased expression of SREBP-1 induces hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidemia, whereas DGAT2 suppression prevents steatosis (5, 8, 36). A decrease in the MTTP level reduces VLDL secretion (29). HDL, which is the predominant lipoprotein in mice, was reduced in parallel with HMGCoAR mRNA levels in DIO and ob/ob mice. On the other hand, the expression of genes involved in lipolysis was not affected by the lack of resistin. Together, these results suggest that resistin affects lipids mainly by regulating lipogenic enzymes.

Our findings are consistent with those of Sato et al. (33). In the latter study, the adenovirus-mediated overexpression of resistin increased triglyceride and cholesterol levels. VLDL secretion was increased by resistin, although the expression of MTTP and apoB did not change (33). Hyperinsulinemia has been associated with steatosis and hyperlipidemia in humans and animal models (2, 5, 20, 36). Conversely, treatment with insulin-sensitizing drugs ameliorates steatosis and hyperilipidemia (5, 6, 7, 10, 23, 39). In the current study, the degree of steatosis was related to insulin levels in DIO WT (5.14 ± 0.4 ng/ml) and RKO (3.18 ± 0.73 ng/ml) and ob/ob (18.4 ± 0.3 ng/ml) and ob/ob-RKO (11.7 ± 2.1 ng/ml) mice. An association between resistin and insulin and steatosis is consistent with the elevation of basal insulin concentration in resistin-treated mice (33). The resistin receptor is as yet unknown, but insights have been gained from the effects of resistin on glucose metabolism (3, 27). We have reported that the ablation of retn attenuated insulin resistance in WT and ob/ob mice (3, 27). Likewise, a reduction in the circulating resistin level via antisense oligonucleotide treatment increased insulin sensitivity (19). Conversely, an increase in resistin via an infusion of recombinant resistin or transgenic overexpression impaired insulin sensitivity (32, 34).

Resistin-mediated hepatic insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity has been related to the inhibition of AMPK and activation of ACC and SOCS-3 (3, 19, 27). In the current study, ACC mRNA and protein levels were decreased in RKO mice on a high-fat diet and ob/ob-RKO mice on normal chow, consistent with the reduction in hepatic steatosis in these models. However, resistin deficiency did not alter SOCS-3, AMPK, or p-AMPK. This result is in contrast with our earlier studies in which acute resistin treatment induced SOCS-3 expression and suppressed AMPK phosphorylation (3, 19, 27). The reasons for these differences are unknown. Future studies are needed to discover the resistin receptor and determine the specific roles SOCS-3 and AMPK in insulin sensitivity and hepatic lipid metabolism.

Histological abnormalities associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease mainly affect pericentral hepatocytes (12). Leptin-deficient ob/ob mice exhibited steatosis in all zones of the hepatic lobule. In contrast, pericentral hepatocytes were mildly steatotic, whereas periportal hepatocytes were spared in ob/ob-RKO mice. These findings suggest that leptin and resistin interact to produce zonal patterns of steatosis. Insulin and glucose levels were reduced in ob/ob-RKO compared with ob/ob mice, suggesting these factors may play a role in determining the pattern of steatosis. Adiponectin is thought to be protective against steatosis in rodents and humans (14, 40). However, the levels of adiponectin did not change in DIO and ob/ob mice lacking resistin, arguing against a significant role of adiponectin in mediating the lipid dysregulation in these particular models (14, 40).

In summary, our studies demonstrate that resistin is an important mediator of hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidemia, particularly in mice lacking leptin. A further examination of the interactions between these adipokines may provide valuable insight into the pathogenesis and treatment of lipid abnormalities associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants PO1-DK049210 (to R. S. Ahima) and P30-DK19525 (Penn Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Core).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahima RS, Flier JS. Leptin. Annu Rev Physiol 62: 413–437, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo P Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 346: 1221–1231, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee RR, Rangwala SM, Shapiro JS, Rich AS, Rhoades B, Qi Y, Wang J, Rajala MW, Pocai A, Scherer PE, Steppan CM, Ahima RS, Obici S, Rossetti L, Lazar MA. Regulation of fasted blood glucose by resistin. Science 303: 1195–1198, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks WA, Willoughby LM, Thomas DR, Morley JE. Insulin resistance syndrome in the elderly: assessment of functional, biochemical, metabolic, and inflammatory status. Diabetes Care 30: 2369–2373, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest 114: 147–152, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao L, Marcus-Samuels B, Mason MM, Moitra J, Vinson C, Arioglu E, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. Adipose tissue is required for the antidiabetic, but not for the hypolipidemic, effect of thiazolidinediones. J Clin Invest 106: 1221–1228, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavez-Tapia NC, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Tellez-Avila FI, Sanchez-Avila F, Montano-Reyes MA, Uribe M. Insulin sensitizers in treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 12: 7826–7831, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi CS, Savage DB, Kulkarni A, Yu XX, Liu ZX, Morino K, Kim S, Distefano A, Samuel VT, Neschen S, Zhang D, Wang A, Zhang XM, Khan M, Cline GW, Pandey SK, Geisler JG, Bhanot S, Monia BP, Shulman GI. Suppression of diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 (DGAT2), but not DGAT1, with antisense oligonucleotides reverses diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 282: 22678–22688, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet 365: 1415–1428, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farooqi IS, Matarese G, Lord GM, Keogh JM, Lawrence E, Agwu C, Sanna V, Jebb SA, Perna F, Fontana S, Lechler RI, DePaoli AM, O′Rahilly S. Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest 110: 1093–1103, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallikainen M, Kolehmainen M, Schwab U, Laaksonen DE, Niskanen L, Rauramaa R, Pihlajamaki J, Uusitupa M, Miettinen TA, Gylling H. Serum adipokines are associated with cholesterol metabolism in the metabolic syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 383: 126–132, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubscher SG Histological assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Histopathology 49: 450–465, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai Y, Varela GM, Jackson MB, Graham MJ, Crooke RM, Ahima RS. Reduction of hepatosteatosis and lipid levels by an adipose differentiation-related protein antisense oligonucleotide. Gastroenterology 132: 1947–1954, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 116: 1784–1792, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KH, Zhao L, Moon Y, Kang C, Sul HS. Dominant inhibitory adipocyte-specific secretory factor (ADSF)/resistin enhances adipogenesis and improves insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6780–6785, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KH, Lee K, Moon YS, Sul HS. A cysteine-rich adipose tissue-specific secretory factor inhibits adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem 276: 11252–11256, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald GA, Bridle KR, Ward PJ, Walker NI, Houglum K, George DK, Smith JL, Powell LW, Crawford DH, Ramm GA. Lipid peroxidation in hepatic steatosis in humans is associated with hepatic fibrosis and occurs predominately in acinar zone 3. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 16: 599–606, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millar JS, Cromley DA, McCoy MG, Rader DJ, Billheimer JT. Determining hepatic triglyceride production in mice: comparison of poloxamer 407 with Triton WR-1339. J Lipid Res 46: 2023–2028, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muse ED, Obici S, Bhanot S, Monia BP, McKay RA, Rajala MW, Scherer PE, Rossetti L. Role of resistin in diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 114: 232–239, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nandi A, Kitamura Y, Kahn CR, Accili D. Mouse models of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev 84: 623–647, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norata GD, Ongari M, Garlaschelli K, Raselli S, Grigore L, Catapano AL. Plasma resistin levels correlate with determinants of the metabolic syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 156: 279–284, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagano C, Soardo G, Pilon C, Milocco C, Basan L, Milan G, Donnini D, Faggian D, Mussap M, Plebani M, Avellini C, Federspil G, Sechi LA, Vettor R. Increased serum resistin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is related to liver disease severity and not to insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 1081–1086, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palanivel R, Sweeney G. Regulation of fatty acid uptake and metabolism in L6 skeletal muscle cells by resistin. FEBS Lett 579: 5049–5054, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 269: 540–543, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen KF, Oral EA, Dufour S, Befroy D, Ariyan C, Yu C, Cline GW, DePaoli AM, Taylor SI, Gorden P, Shulman GI. Leptin reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. J Clin Invest 109: 1345–1350, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pravenec M, Kazdova L, Landa V, Zidek V, Mlejnek P, Jansa P, Wang J, Qi N, Kurtz TW. Transgenic and recombinant resistin impair skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Biol Chem 278: 45209–45215, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi Y, Nie Z, Lee YS, Singhal NS, Scherer PE, Lazar MA, Ahima RS. Loss of resistin improves glucose homeostasis in leptin deficiency. Diabetes 55: 3083–3090, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi Y, Takahashi N, Hileman SM, Patel HR, Berg AH, Pajvani UB, Scherer PE, Ahima RS. Adiponectin acts in the brain to decrease body weight. Nat Med 10: 524–529, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raabe M, Veniant MM, Sullivan MA, Zlot CH, Bjorkegren J, Nielsen LB, Wong JS, Hamilton RL, Young SG. Analysis of the role of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in the liver of tissue-specific knockout mice. J Clin Invest 103: 1287–1298, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rae C, Graham A. Human resistin promotes macrophage lipid accumulation. Diabetologia 49: 1112–1114, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajala MW, Qi Y, Patel HR, Takahashi N, Banerjee R, Pajvani UB, Sinha MK, Gingerich RL, Scherer PE, Ahima RS. Regulation of resistin expression and circulating levels in obesity, diabetes, and fasting. Diabetes 53: 1671–1679, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rangwala SM, Rich AS, Rhoades B, Shapiro JS, Obici S, Rossetti L, Lazar MA. Abnormal glucose homeostasis due to chronic hyperresistinemia. Diabetes 53: 1937–1941, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato N, Kobayashi K, Inoguchi T, Sonoda N, Imamura M, Sekiguchi N, Nakashima N, Nawata H. Adenovirus-mediated high expression of resistin causes dyslipidemia in mice. Endocrinology 146: 273–279, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satoh H, Nguyen MT, Miles PD, Imamura T, Usui I, Olefsky JM. Adenovirus-mediated chronic “hyper-resistinemia” leads to in vivo insulin resistance in normal rats. J Clin Invest 114: 224–231, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev 87: 507–520, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimano H, Horton JD, Hammer RE, Shimomura I, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Overproduction of cholesterol and fatty acids causes massive liver enlargement in transgenic mice expressing truncated SREBP-1a. J Clin Invest 98: 1575–1584, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, Patel HR, Ahima RS, Lazar MA. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature 409: 307–312, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steppan CM, Lazar MA. The current biology of resistin. J Intern Med 255: 439–447, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi N, Qi Y, Patel HR, Ahima RS. A novel aminosterol reverses diabetes and fatty liver disease in obese mice. J Hepatol 41: 391–398, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Targher G, Bertolini L, Rodella S, Zoppini G, Scala L, Zenari L, Falezza G. Associations between plasma adiponectin concentrations and liver histology in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 64: 679–683, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu W, Yu L, Zhou W, Luo M. Resistin increases lipid accumulation and CD36 expression in human macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 351: 376–382, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]