Abstract

Glucose metabolism is vital to most mammalian cells, and the passage of glucose across cell membranes is facilitated by a family of integral membrane transporter proteins, the GLUTs. There are currently 14 members of the SLC2 family of GLUTs, several of which have been the focus of this series of reviews. The subject of the present review is GLUT3, which, as implied by its name, was the third glucose transporter to be cloned (Kayano T, Fukumoto H, Eddy RL, Fan YS, Byers MG, Shows TB, Bell GI. J Biol Chem 263: 15245–15248, 1988) and was originally designated as the neuronal GLUT. The overriding question that drove the early work on GLUT3 was why would neurons need a separate glucose transporter isoform? What is it about GLUT3 that specifically suits the needs of the highly metabolic and oxidative neuron with its high glucose demand? More recently, GLUT3 has been studied in other cell types with quite specific requirements for glucose, including sperm, preimplantation embryos, circulating white blood cells, and an array of carcinoma cell lines. The last are sufficiently varied and numerous to warrant a review of their own and will not be discussed here. However, for each of these cases, the same questions apply. Thus, the objective of this review is to discuss the properties and tissue and cellular localization of GLUT3 as well as the features of expression, function, and regulation that distinguish it from the rest of its family and make it uniquely suited as the mediator of glucose delivery to these specific cells.

Keywords: neurons, sperm, preimplantation embryo, white blood cells

glucose metabolism is vital to most mammalian cells, and the passage of glucose across cell membranes is facilitated by a family of integral membrane transporter proteins, the GLUTs. There are currently 14 members of the SLC2 family of GLUTs, several of which have been the focus of this series of reviews. The subject of the present review is GLUT3 which, as implied by its name, was the third glucose transporter to be cloned (62) and was originally designated as the neuronal glucose transporter. Together with GLUT1, -2, and -4, it comprises the Class 1 group of transporters (For review see Refs. 15, 81, 121). With the cloning of GLUT3, it became apparent that the brain did not rely exclusively on GLUT1 and that GLUT3 was highly and specifically expressed by neurons. Thus, GLUT3 became the third facilitative glucose transporter isoform with unique characteristics suited for cell-specific expression and function. GLUT2 is ideally suited for expression in liver and pancreas due to its high Km for glucose; GLUT4 and its translocation from intracellular vesicles to the cell surface facilitates insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in insulin-sensitive cells: muscle and fat. The overriding question that drove the early work in GLUT3 in the brain was: why would neurons need a separate glucose transporter isoform; what is it about GLUT3 that specifically suits the needs of the highly metabolic and oxidative neuron with its high glucose demand? More recently, GLUT3 has been studied in other cell types with quite specific requirements for glucose, including sperm, preimplantation embryos, circulating white blood cells, and an array of carcinoma cell lines. The latter are sufficiently varied and numerous to warrant a review of their own and will not be discussed here. However, for each of these cases the same questions apply. Thus the objective of this review is to discuss the properties and tissue and cellular localization of GLUT3 as well as the features of expression, function, and regulation that distinguish it from the rest of its family and make it uniquely suited as the mediator of glucose delivery to these specific cells.

History

Human GLUT3 was initially cloned by low-stringency hybridization from a fetal skeletal muscle cell line, using a GLUT1 cDNA probe, and was found to share 64.4, 51.6, and subsequently 57.5% identity with GLUT1, -2, and -4, respectively (62). The original Northern blots suggested that, while GLUT3 was highly expressed in brain, it was also detected in various carcinoma cell lines in kidney, colon, and placenta, and to a lesser extent in small intestine, stomach, and subcutaneous fat. It was barely detectable in adult skeletal muscle and thus was not considered to be the then-elusive insulin-regulated glucose transporter GLUT4, which was cloned by a variety of groups shortly thereafter (17, 23, 39, 55, 56, 58). Subsequent studies using Western blot analysis have supported a far less ubiquitous distribution of GLUT3 protein (48, 107). GLUT3 received its commonly used title as the “neuronal glucose transporter” when it was cloned from a mouse library by Nagamatsu et al. (92). These studies revealed that the distribution of GLUT3 mRNA was much more restricted in mouse than in human tissues, being essentially confined to brain; GLUT3 was later found in other murine cells, as discussed below. The same study demonstrated GLUT3 expression by in situ hybridization exclusively in neurons, thus the designation neuronal glucose transporter. Having defined GLUT3 as the neuronal transporter, the question still arose as to its localization within the neuron. Currently, the consensus opinion is that GLUT3 is found predominantly in the cell processes, i.e., axons and dendrites, with less labeling in the cell body. However, as is evident in Fig. 1, which depicts rat cerebellar granule neurons in culture and pyramidal neurons in human hippocampus, labeling is evident in axons and dendrites as well as in the neuronal cell bodies (44, 71, 75, 78, 82, 84, 128).

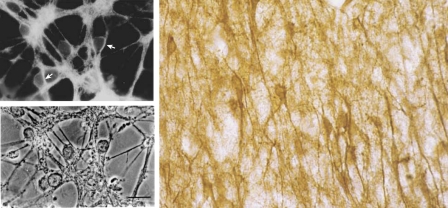

Fig. 1.

GLUT3 distribution in rat cerebeller granule cells and human hippocampal neurons. Top left: immunohistochemical distribution of GLUT3 in cerebeller granule cells derived from the cerebellum of 8-day-old rats having undergone differentiation over a subsequent 6 days in culture. Bottom left: corresponding phase micrograph. Right: distribution of GLUT3 in human hippocampal pyramidal neurons. In both human and rat neurons, it is evident that GLUT3 is in axons, dendrites, and cell bodies. Micrographs were previously published (78, 128) and are reprinted here with permission.

Structure

Although X-ray crystal structures of GLUT proteins are currently unavailable, a molecular model has been created for GLUT3 (32). High affinity glucose transporter proteins may be characterized by several structural features: the first extracellular loop; the N-terminal (membrane proximal) segment of intracellular loop 6; and central residues of TM9 and TM11 (depicted in the model of GLUT3 in Fig. 2). Class I (GLUT3) and II glucose transporter proteins bear an N-linked glycosylation site in loop 1, whereas Class III glucose transporters are glycosylated in extracellular loop 9. N-glycosylation of the GLUT is required to maintain high-affinity transport of glucose (9). The significance of the first extracellular loop is further highlighted by the fact that the length of this loop is inversely correlated (r = 0.8–0.9) with the Km of transport for GLUT1–4, GLUT8, and GLUT10 (D. Dwyer, unpublished observation). A second region of interest is intracellular loop 6. The membrane proximal segment just COOH-terminal to TM6 is in close proximity to the exit site of the transporter pore. The amino acid sequences of the GLUT family diverge at this point, which may determine the disposition of this segment relative to the pore or its flexibility and thus transport kinetics. Residues near the constriction of the pore in TM9 and TM11 represent a third area where sequence differences may explain function (Fig. 2). In human GLUT3, these segments include a number of small amino acids (particularly glycine) and residues capable of hydrogen bonding to glucose (e.g., serine and asparagine). In lower-affinity transporters such as GLUT1 and GLUT2, bulkier amino acids such as alanine, isoleucine, and phenylalanine replace glycine, threonine, and leucine/cysteine, respectively, in TM9 and TM11. The bulkier substitutions may alter local properties of the pore and increase the Km. Of course, changes at other sites may also contribute to the differences in transport kinetics.

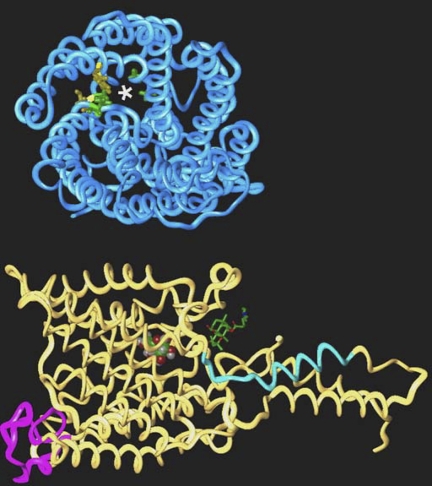

Fig. 2.

Structural features of GLUT3. Left: model of GLUT3 is oriented with the extracellular face at the top. Loop 1 is depicted in purple, and the membrane-proximal segment of loop 6 is shown in blue. Glucose (CPK rendering) is visible in the pore, and the putative intracellular binding site for forskolin (stick rendering) is indicated. Right: model has been tilted forward 90° to reveal the pore indicated with an asterisk. Small residues that line the pore are shown in green (Gly338, Gly340, and Gly406 and Asn409), and residues where bulkier substitutions may affect pore size are colored yellow (Phe348 and Cys407).

Kinetics

The determination of substrate specificity and kinetic parameters of the individual facilitative glucose transporter proteins as expressed in mammalian cells is frequently complicated by the simultaneous expression of multiple isoforms in a given cell. In addition, it is difficult to accurately determine the number of transporters on the cell surface. To circumvent the specificity problem, all of the family members have now been expressed in Xenopus oocytes (see Ref. 81 for review). In the original studies, GLUT3 was consistently found to exhibit a lower Km than its other Class 1 counterparts, GLUT1, -2, and -4, with Km values for 2-deoxyglucose uptake of 1.4 mM compared with GLUT1, 6.9 mM, GLUT2, 11.2 mM, and GLUT4, 4.6 mM; Km values for 3-O-methylglucose equilibrium exchange of 10.6 compared with Km for GLUT1, -2, and -4 of 21, 42, and 4.5 mM, respectively (6, 46, 47, 63, 81, 96). GLUT3 was also shown to transport mannose, galactose, and xylose but is unable to transport fructose. More recently, the Class II and III members of the transport family, particularly GLUT7, -9, -10, and -11 have been shown to have particularly high affinities for glucose with Kms on the order of 0.1–0.3 mM. With the exception of the study by Nishimura et al. (96), these studies were unable to shed any light on the transport capacity, i.e., Kcat, or turnover number for the respective transporters as this requires an accurate measurement of the number of transporters on the plasma membranes of the respective cells. The most common approaches to achieve this have been either to measure the binding of cytochalasin B, a competitive inhibitor of glucose transport, or to use the Holman reagent, which is a tritiated, impermeant reagent that upon photoactivation covalently binds to all glucose transporter proteins in the correct conformation at the plasma membrane. By use of a combination of such approaches, GLUT3 in rat cerebellar granule neurons was shown by Maher et al. to have a significantly greater Kcat, 6,500/s, than either GLUT1 expressed in human erythrocytes, 3T3-L1 adipocytes or oocytes, 1,200/s, or GLUT4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes or oocytes, 1,300/s at 37°C (73, 76, 77, 96, 98).

Thus GLUT3 has both a higher affinity for glucose than GLUT1, -2, or -4 and at least a fivefold greater transport capacity than GLUT1 and -4. This is particularly significant for the role of GLUT3 in neuronal transport, as the ambient glucose levels surrounding the neuron are only 1–2 mM compared with 5–6 mM in serum. Furthermore, as there are approximately the same number of GLUT1 glucose transporters on glial and endothelial cells, the combination of lower Km and higher capacity enables the neuron preferential access to available glucose.

Neuronal GLUT3 and Cerebral Glucose Utilization

Numerous studies, predominantly in rodent brain, concluded that glucose delivery and utilization in the mammalian brain is mediated primarily by both GLUT1 and GLUT3: a high molecular weight form of GLUT1 in the endothelial cells of the microvessels that comprise the blood-brain barrier (BBB), GLUT3 in all neuronal populations, and a lower-molecular-weight, less glycosylated form of GLUT1 in the remainder of the brain parenchyma (71, 85, 108, 128).

Having established the cell-specific expression of GLUT1 and GLUT3, the next question that arose concerned the relationship between expression of these transporters and cerebral glucose metabolism. In pursuit of this question, we and others initiated a series of experiments on the regulation of GLUT1 and GLUT3 expression in mammalian brain in both physiological and pathological conditions. One of the earliest in vivo studies by Bondy et al. (19) demonstrated that GLUT3 mRNA expression was very low in the prenatal rat brain, with GLUT1 being the predominant isoform in neural progenitor cells of the germinal matrix. However, GLUT3 mRNA was detected in neuronal cells that had migrated to the cerebral cortex, which would correlate with neuronal maturation and the establishment of synaptic connections. Indeed, it is the establishment of synaptic connectivity and communication that drives the largest energy demand of the brain (10). We (93, 94) subsequently demonstrated that both GLUT1 and GLUT3 increase with cerebral maturation, concurrent with the measured increases in cerebral glucose utilization. However, whereas GLUT1 increases steadily throughout cerebral maturation, GLUT3 mRNA and protein expression increases in a regional and activity-dependent manner. An analysis of GLUT3 protein expression, relative to a series of neuron-specific synaptic proteins such as synaptophysin, SNAP-25, and the α3 subunit of Na+-K+-ATPase, demonstrates a strikingly similar pattern in each brain region that correlates with the maturation and regional cerebral glucose utilization (rCGU) profile for each. Thus, it appears that GLUT3 expression in neurons in the rat coincides with maturation and synaptic connectivity (125) and a positive correlation between protein levels of GLUT1, GLUT3, and rCGU was established using immunoautoradiography (30, 134) and was also observed in the mouse (64).

The dynamic relationship between rCGU and GLUT3 expression was most clearly demonstrated when the effects of dehydration/rehydration were investigated in the adult rat. The neural lobe of the pituitary or neurohypophysis, is formed from the axon terminals of oxytocin- and vasopressin-expressing neurons that originate in the supraoptic and periventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus, and surrounding glial-like cells called pituicytes. Early studies demonstrated that, in response to progressive dehydration, these cells and others that are associated with the hypothalmalo-neurohypophysial axis become activated, resulting in markedly enhanced rates of glucose utilization and the secretion of vasopressin and oxytocin (57). Subsequent studies confirmed these observations and determined the effects of both dehydration and rehydration on the expression of GLUT1 and -3 (31, 68, 127). Three days of dehydration resulted in increases in the protein expression of GLUT1 and -3 in the neurohypophysis of 44 and 55%, respectively. A similar increase in GLUT3 levels in the neurohypophysis was also seen following 14 days of streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the rat, whereas GLUT1 expression was diminished by 25%. Interestingly, the levels of GLUT3 mRNA in the magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic and paraventicular nuclei were only very modestly altered, which was surprising given the substantial increase in GLUT3 protein expression. This might be explained by the dramatic increase in GLUT3 mRNA in the axon terminals that make up the neurohypophysis. It seems unlikely that the mRNA is translated within the axon, as there is no apparent rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi that would be necessary to synthesize a transporter protein (40). However, together with mRNAs for oxytocin and vasopressin, GLUT3 mRNA may be associated with a ribonucleoprotein complex that serves as a potential docking, storage, and posttranscriptional regulation site (114, 120). Within 3 days of rehydration, rates of rCGU and GLUT3 mRNA return to control levels, whereas restoration of GLUT3 protein levels within the neural lobe of the pituitary requires between 3 and 7 days (68).

These studies examined both normal and experimental increases in cerebral glucose utilization and the accompanying increase in GLUT3 expression. Marked declines in cerebral glucose metabolism are associated with Alzheimer's disease, especially in the parietal and temporal cortices (28, 29, 37, 54). Initial studies by Kalaria and Harik (59) demonstrated a reduction in the 55-kDa form of GLUT1 in cerebral microvessels prepared from Alzheimer's patients compared with normal age-matched controls (60). These observations were confirmed and extended in studies by Simpson et al., who also demonstrated a loss of the 45-kDa glial form of GLUT1 and a striking loss of GLUT3 protein expression in parietal, occipital, and temporal cortex, together with caudate nucleus and hippocampus; only the frontal cortex did not show any significant loss (109). Importantly, the decreases in GLUT3 in the parietal and temporal cortices, hippocampus, and caudate were still significant even after correction for overall neuronal loss using the synaptic protein SNAP25 as a marker.

Over the past decade, the central role of GLUT3 in cerebral metabolism has been questioned by the studies of Magistretti and colleagues who have proposed that astrocytes play the key role in the coupling of neuronal activity and cerebral glucose utilization, according to what has come to be known as the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (ANLS) hypothesis (74, 103). According to this hypothesis, the astrocyte, which relies on GLUT1 for glucose transport, is the primary consumer of blood-borne glucose in the brain. Within the astrocyte glucose is metabolized glycolytically to lactate which is then exported as the primary energetic fuel for the neuron; this process is supposedly stimulated by glutamate. Since its original proposal, the ANLS has become widely interpreted as suggesting that the principle source of energy consumed by the neuron is lactate, thus obviating the need for neuronal glucose uptake via GLUT3. This has recently been challenged in a publication by Simpson et al. (108) who support the more traditional concept of cerebral metabolism that glucose is taken up and metabolized primarily in the neuron (also Ref. 111). By modeling the kinetic characteristics and respective cellular concentrations of the neuronal and glial glucose and lactate transporters, it was concluded that the glucose transport capacity of the neuron via GLUT3 far exceeds that of the astrocyte (GLUT1). Consequently, the interstitial lactate results from excessive glycolysis in the neuron and not the astrocyte (108), thus reestablishing the uniqueness of GLUT3's role in neuronal metabolism. Certainly, during periods of activation and high neuronal energy demand, the neuron will likely utilize any available fuel; however, the demonstration of an increase in GLUT3 expression during all in vivo conditions associated with increased CGU described above provides further confirmation for the central role of GLUT3.

Although GLUT3 is clearly the ideal teleological choice for neuronal transporter, substantial evidence indicates that it is not the exclusive neuronal glucose transporter. GLUT1 can be readily detected in cultured neurons and is detected in vivo under conditions of stress such as following a hypoxic-ischemic insult (45, 70, 78, 129, 131). The presence of GLUT2 has been reported in neurons in the hypothalamus (7, 8), and GLUT4 has been found in several subsets of neurons, including Purkinje and granule cells in cerebellum, principle and nonprinciple cells in the hippocampus, and isolated cells in the cortex and hypothalamus (5, 7, 12, 67, 72, 106, 126). Both GLUT6 and -8 have been reported to be present in neurons; however, as with GLUT4, both proteins contain a dileucine motif in their COOH termini and would appear to reside in intracellular membranes; GLUT8 may be recruited to the ER in the presence of insulin (see Ref. 85 for review).

GLUT3 in Murine Sperm

Glucose metabolism has been shown to be critical for sperm function, through both glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. As with other cell types that express GLUT3, murine sperm experience states of “activation” with heightened energy demand. Sperm are stored in a quiescent state in the cauda epididymides of most mammalian species. Upon ejaculation, they mix with seminal plasma and acquire an “activated” pattern of motility. However, sperm are not competent to fertilize an egg until they mature functionally in response to stimuli within the female tract. This process is known as “capacitation” and involves changes in both the head and flagellum of the sperm (117). The head acquires the ability to undergo acrosomal exocytosis, and the flagellum acquires a “hyperactivated” pattern of motility. Both changes are essential for fertilization to occur.

To achieve maximal reproductive success, males have evolved a strategy of producing numerous sperm while investing as little as possible in each one. To supply the highly polarized sperm with the metabolic products it needs, precisely where it needs them, sperm have compartmentalized these pathways to the various regions of the cell. For example, the pentose phosphate pathway is found in the head and midpiece, and glycolysis is found down the length of the flagellar principal piece (Fig. 3). Remarkably, although the restriction of mitochondria to the sperm midpiece is highly conserved across species, at least in the mouse these mitochondria do not need to produce energy for sperm to have a normal activated pattern of motility (91). However, the ATP produced from glycolysis is essential for normal flagellar motility even in the presence of otherwise functional mitochondria (86, 91). In addition, ATP produced by glycolysis is essential for the protein tyrosine phosphorylation events associated with capacitation (116). Thus the glycolytic machinery compartmentalized to the principal piece of the flagellum powers both the dynein ATPases that provide motility, as well as the kinases that regulate it.

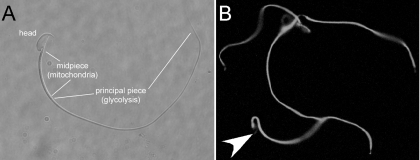

Fig. 3.

Murine sperm are highly compartmentalized in terms of structure and function. A: the head and the 2 major pieces of the flagellum, the midpiece, and principal piece. Oxidative respiration is restricted to the midpiece, whereas glycolysis is organized down the length of the principal piece. B: GLUT3 is shown as expressed throughout the flagellum. It is likely that the pentose phosphate pathway is active in the midpiece, which also has high abundance of the germ cell-specific hexokinase, but not other glycolytic enzymes, such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Arrowhead points to faint staining in the apical acrosome of one cell to show the location of the head in this sperm. But, as this figure shows, even faint signal in the head is relatively uncommon among murine sperm.

Of note, glucose concentrations as low as 10–100 μM are all that are necessary to support the tyrosine phosphorylation signaling in murine sperm (116). This low concentration is consistent with a primary role for GLUT3, which is the predominant family member in murine sperm (122). In this regard, GLUT3 is highly concentrated in the plasma membrane of the entire flagellum and is in fact one of the most abundant sperm membrane proteins (Fig. 3B; C. Mukai and A. Travis, unpublished observation). Consistent with its highly streamlined structure, the sperm flagellum does not have internal vesicles that function as stores of transporters or substrate. Rather, GLUT3 in the plasma membrane provides a “high throughput” capability by supplying substrate to the enzymes of glycolysis that are arrayed, at least in part, on the fibrous sheath, a cytoskeletal structure located immediately below the membrane (20, 90, 113, 115, 132). The high surface-area to volume of the flagellum maximizes the efficiency of the system, and then waste in the form of lactate can be removed by means of membrane monocarboxylate transporters (118).

In addition to providing energy to power and regulate motility for the sperm to reach the oocyte, glucose metabolism is also required for sperm-oocyte interaction (119, 122, 123). Yet it remains slightly unclear which GLUT family members are responsible for supplying substrate to the pentose phosphate pathway in the sperm head. Both GLUT8 and GLUT9b have been shown to be present in the apical portion of the head (66), putting them in appropriate position to do so, although other family members might also be present at low levels. The concentration of glucose required for this positive impact on sperm-egg binding and fusion is ∼1 mM (123), making it likely that glucose uptake in the apical acrosomal region is mediated by a transporter other than GLUT3.

Although GLUT3 is expressed highly in murine sperm, it should be noted that expression of GLUTs in sperm varies with species. This likely reflects important adaptations of the male gamete in response to the availability of different carbohydrate sources and abundance in the oviduct. Perhaps the best example of this is bovine sperm, in which GLUT5 is responsible for the uptake of fructose in seminal plasma (4). Unlike capacitation and fertilization in murine sperm, which rely on glucose, bovine sperm capacitation is inhibited by glucose (41, 102). Sperm of this species apparently use passage from the high fructose environment of seminal plasma (calculation of 28 mM based on Ref. 80) to the low carbohydrate environment of the oviduct (calculation of 0.01 to 0.05 mM glucose based on Ref. 21) as a signal, via the release of inhibition, to capacitate and become able to fertilize (102). Species that rely on sperm GLUT3 would be predicted to have reliable, but low glucose intermediates in oviductal fluid.

GLUT3 in the Embryo

Several studies have demonstrated that GLUT3 expression is crucial for optimal preimplantation embryo development and survival. Pantaleon et al. (99) first described the expression of this transporter in murine embryos in 1997. GLUT1 and GLUT2 had been identified six years earlier in the murine preimplantation embryo (1, 51). GLUT1 was expressed through this period, from one-cell zygote to blastocyst stage. GLUT2 expression was first detected at an eight-cell stage. At the blastocyst stage, GLUT2 protein expression was restricted to basal trophectoderm in direct contact with the blastocoele cavity, whereas GLUT1 was localized to apical, basolateral, and intercellular junctions between cells. In that report, GLUT1 was purported to be the main glucose transporter, responsible for uptake of maternal glucose. Pantaleon et al. (99) noted, however, that this would be unlikely given that the Km of glucose transport was much lower than that of GLUT1. Gardner and Kaye (43) had demonstrated that the mouse blastocyst had a Km of 6.3 ± 0.5 mM for 3-O-methylglucose (3-OMG) whereas GLUT1's Km for 3-OMG is 20.1 ± 2.9 mM. In contrast, GLUT3 has a Km of 10.6 ± 1.3 mM for 3-OMG and is normally expressed on apical surfaces where it typically functions as a high-capacity glucose transporter. Pantaleon et al. (101) went on to reveal that GLUT3 was expressed at an mRNA level at a late four-cell stage and at a protein level first at late eight-cell early morula stage and most clearly seen at a late morula stage on the apical surface of the polarized outer cells and finally in the blastocyst stage in the apical surface of the trophectoderm. They went on to show that downregulation of expression of GLUT3 with antisense oligonucleotides resulted in a significant drop (>40%) in glucose uptake and a 50% decrease in the number of embryos progressing to a blastocyst stage compared with blastocysts treated with sense oligonucleotides. Inhibition of GLUT1 expression with antisense oligonucleotides did decrease glucose uptake, albeit to a much lesser extent than GLUT3. They concluded that GLUT3 functions as the high-affinity glucose transporter and that its expression correlates with compaction and the switch to a metabolic preference for glucose vs pyruvate (99).

Subsequently, Moley et al. (88) described a pathological condition, maternal diabetes mellitus induced in the mouse by streptozotocin injection, in which GLUT3 expression was physiologically downregulated at both the mRNA and protein levels of expression in the blastocyst. These blastocyst stage embryos displayed decreased glucose uptake by measurements using nonradioactive microanalytic cycling reactions on individual blastocysts. These findings were consistent with those of Pantaleon et al. (99), in which downregulation with antisense oligoneucletides induced a similar decrease in glucose uptake. In addition, Moley et al. demonstrated increased apoptosis and an abnormal metabolic profile (25, 88). In vitro culture in high glucose concentrations induced the same decrease in GLUT3 expression and when transferred into recipient mice, these embryos displayed intrauterine growth retardation and a high incidence of fetal resorptions (133). This group concluded that decreased expression of GLUT3 in these embryos exposed to high maternal glucose levels was in response to unfavorable maternal milieu but that a threshold of glucose was required for embryonic growth and further development. They proposed that, if this threshold was crossed, an apoptotic pathway was triggered leading to loss of key cells required for optimal survival (88, 89). These findings all point to GLUT3 being a critical transporter protein required for this stage of development.

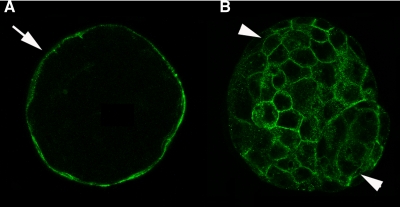

These findings were substantiated by the creation of a GLUT3-null (GLUT3−/−) mouse, as described by Devaskar's group [Ganguly et al. (42)]. In this model, the knockout construct globally removed exons 7–9 and coding region 10 of GLUT3. At a blastocyst stage, the GLUT3−/− embryo was detected but displayed increased apoptosis and delayed development. Despite the high incidence of apoptosis, the blastocysts implanted and GLUT3−/− embryos were detected at embryonic day 6.5; however, further investigation revealed a loss at embryonic day 8.5. Interestingly, the heterozygous blastocysts displayed an atypical localization of GLUT3 protein (Fig. 4). As opposed to the wild-type blastocyst, in which GLUT3 localized consistently to the apical trophectoderm, the heterozygote blastocysts expressed GLUT3 both apically and basolaterally in the trophectoderm and inner cell mass cells. These heterozygotes also displayed an increase in TUNEL-positive nuclei or apoptosis. The rate of apoptosis was intermediate between the GLUT3−/− and wild-type embryos. In addition, GLUT1 localization was also abnormal in both the GLUT3−/− and GLUT3−/+ blastocysts. GLUT1 was detected on both apical and basolateral surfaces of the trophectoderm in the heterozygote, whereas in the GLUT3−/− blastocyst GLUT1 resided in punctate cytoplasmic vesicles. This distribution pattern is identical to that seen in precompaction blastomeres prior to the establishment of polarity and the differentiation into trophectodermal epithelium (100). GLUT1 localization in the wild-type blastocyst was in the expected basolateral plasma membrane. Those authors concluded that some degree of GLUT3 expression was required to trigger polarization and successful establishment of a healthy blastocyst (42). The authors went further to postulate that GLUT1 and GLUT3 might need to be expressed differentially in timing and location to permit adequate glucose uptake and development.

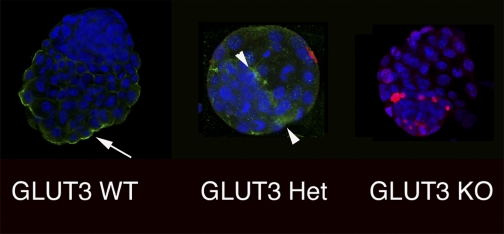

Fig. 4.

Preimplantation embryos demonstrate dual immunohistochemical staining for GLUT3 and TUNEL. A: representative wild type (WT); B: heterozygous (Het); C: homozygous knockout (KO) embryo demonstrating GLUT3 (green) and TUNEL (red) along with nuclear ToPro-3 (blue) staining. WT demonstrates apical distribution (arrow); heterozygous embryo demonstrates punctuate distribution of GLUT3 on apical and basolateral surfaces of the trophectoderm (arrowhead); homozygous embryos demonstrate no GLUT3. TUNEL staining progressively increases from WT to homozygous embryos.

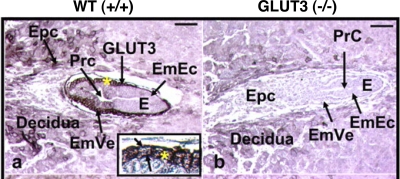

The GLUT3−/− mouse model was similar to the diabetic model in another aspect. The blastocysts exposed to diabetic conditions by downregulation of GLUT3 displayed increased fetal resorptions and significant growth retardation (133). Similarly, the GLUT3−/− embryos implanted but failed to progress past embryonic day 6.5 (42) (Fig. 5). The GLUT3−/+ fetuses demonstrated an intermediate expression of GLUT3 at both blastocyst stage and postimplantation and survived but were growth retarded with a 20% peak decline in body weight compared with controls. It is unclear whether these growth effects are due to decreased expression of placental or fetal GLUT3; however, due to the lack of significant growth retardation in the GLUT1-null mouse (130), the conclusion appears to be that GLUT3's critical function is the trophectoderm/placenta, which indirectly affects fetal growth, whereas GLUT1 functions to provide glucose for embryonic organogenesis (Fig. 6). Transplacental uptake studies in Devaskar's group demonstrated that, in the murine hemiochorial placenta, GLUT3 deficiency led to a decrease in transplacental glucose transport and fetal uptake that was more than a slight decrease in intraplacental glucose uptake (42).

Fig. 5.

Embryos at 6.5 days in longitudinal sections (E) in situ within maternal deciduas and uterine cavity demonstrate the presence (+/+) (a) consistent with a WT phenotype or absence (b) consistent with a GLUT3-null homozygous phenotype of GLUT3 immunoreaction (arrows) on the embryonic visceral endoderm (EmVe), seen under higher magnification (*) in inset.

Fig. 6.

Blastocysts at 6.5 days, fixed in paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Tween, were incubated with a primary rabbit anti-mouse GLUT3 antibody (A) or a primary murine anti-rat GLUT1 antibody for 1 h at room temperature (B) both at 20 g/ml. GLUT3 is predominantly located in the apical trophectoderm plasma membrane (arrow), whereas GLUT1 is localized to the basolateral surfaces of both the trophectoderm and inner cell mass cells (arrowheads).

Several studies using different technologies have shown that GLUT3 is expressed at high levels in the extra-embryonic membranes (amnion, chorion, and yolk sac) and goes on to be expressed in the rapidly dividing, poorly differentiated placental extravillous trophoblast and villous cytotrophoblast subpopulations (49, 110). This finding is consistent in both human and mouse early placental development, despite the fact that placental structures differ significantly between the species. Human placenta is hemomonochorial and villous in structure, whereas mouse placenta is hemotrichorial and labyrinthine in structure. GLUT3 protein has been detected in first trimester mouse and human trophoblast cells as well as in choriocarcinoma cell lines (52, 97), suggesting that GLUT3 protein may be most critical early in postimplantation gestation, when a high-affinity glucose transporter like GLUT3 would allow constant uptake of this energy substrate under conditions of decreased substrate concentration. These trophoblast cells invade and erode the uterine epithelium upon implantation and eventually reach the maternal blood supply where they bathe in these islands. Expression of GLUT3 on the extra-embryonic membrane surfaces would permit maternally produced glucose to travel to the rapidly growing and energetically demanding embryo.

Human term placenta expresses no GLUT3 protein despite the fact that GLUT3 mRNA is localized to the same placental membranes as GLUT1 mRNA in both syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts throughout gestation. This developmental differential expression of GLUT3 protein and constant expression of GLUT3 mRNA at term suggests some form of active regulation that suppresses expression of the protein. Studies have demonstrated that this level of mRNA in term human trophoblast is regulated by hypoxia, suggesting that a constitutive block in translation of the mRNA does exist (33).

The postimplantation embryonic expression of GLUT3 is transient. Although expressed in the 8.5-dpc nonneuronal surface ectoderm of the embryo proper, GLUT3 is downregulated significantly by dpc 10.5 (110) and is no longer detectable by dpc 8.5 in fetal brain (64). The consensus of all these studies is that blastocyst expression of GLUT3 is confined to trophectoderm and that postimplantation expression is predominantly extra-embryonic, supporting GLUT3 as a critical mediator of transplacental glucose transporter necessary for fueling fetal growth.

Finally, in a recent study, Kaye's group [Pantaleon et al. (101)] has suggested an interesting role for glucose in the metabolic differentiation of the murine blastocyst and in the induced expression of GLUT3. It has been known for over a decade that, although murine precompaction stage embryos are unable to metabolize glucose, they require a brief exposure to glucose prior to the morul stage (24). Without this glucose exposure, the embryos undergo increased apoptosis, decreased proliferation, and reduced glucose transport, and their progression to a blastocyst stage is impaired. This phenotype is similar to the GLUT3-null blastocyst; thus, this group hypothesized that perhaps GLUT3 expression was blocked. They confirmed this and went on to demonstrate that a pulse of glucose (27 mM for 1–3 h prior to 67 h post-hCG) is necessary to activate transcriptional and translational expression of GLUT3. In addition, glucosamine at the same concentration and timing is also sufficient to prime the embryo, suggesting that the hexosamine pathway may be involved. They concluded by postulating that the downstream component of this pathway, UDP-GlcNAC (uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine), may be the effector which triggers metabolic differentiation via O-linked glycosylation of the transcription factors regulating GLUT3 and possibly other key players in this process.

GLUT3 in Human White Blood Cells

The first observation of GLUT3 in white cells occurred when its localization in human brain was being studied (82). In addition to the expected pronounced neuronal localization, GLUT3 displayed both a vascular and an intravascular expression, and the latter was not associated with erythrocytes. GLUT3 has subsequently been shown to be present in human lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, and platelets. What is particularly significant about the presence of GLUT3 in white cells is that it is present in an intracellular pool and may be recruited to the plasma membrane upon activation in a manner entirely analogous to that of GLUT4 translocation in muscle and adipose tissue. Indeed, in B-lymphocytes and monocytes, insulin is able induce a translocation of GLUT3 but is without effect on neutrophils or T-lymphocytes (27, 34, 38, 83). It should be noted that an earlier study by Bilan et al. (16) demonstrated the translocation of GLUT3 in response to insulin and IGF-I in the fetal L6 rat muscle cell line.

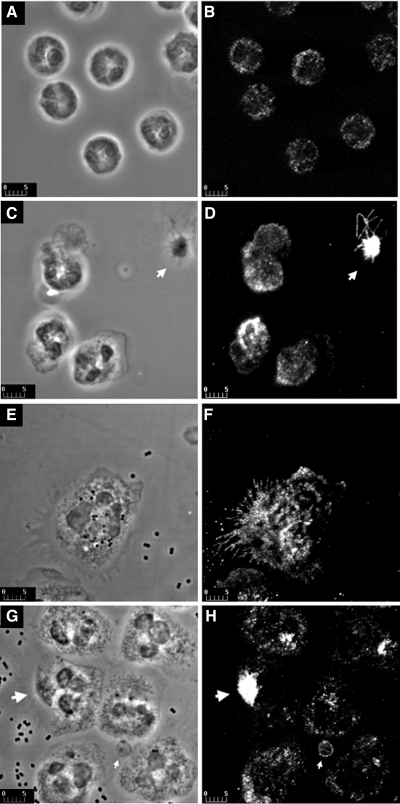

Activation of the white cells with either PMA or the appropriate activator, e.g., lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) for neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages, phytohemagglutinin (PHA) for lymphocytes, and thrombin for platelets also results in the recruitment of GLUT3 to the plasma membrane (26, 35, 38, 50, 53, 83, 112). Figure 7 depicts the activation of neutrophils and platelets and the recruitment of GLUT3 to the respective plasma membranes. This figure also illustrates the subcellular localization of GLUT3 in quiescent neutrophils and platelets (Fig. 7, A and B) and their subsequent activation by PMA (Fig. 7, C and D) and, in the case of neutrophils, by bacteria (Fig. 7, E–H). In the case of the platelets, GLUT3 is clearly recruited to the membrane from an intracellular location, namely the α-granules (50). A similar recruitment is seen in the neutrophils when activated with PMA. However, when activated with bacteria, not only is GLUT3 recruited to the cell surface and spike-like projections of the plasma membrane (Fig. 7F), but it also appears highly concentrated intracellularly in phase-dense (phagasome-like) structures (Fig. 7H). In some of these structures, the intensity of the fluorescence is higher or at least comparable to that observed over platelets (Fig. 7H). Very little is known of the nature of the intracellular membranes containing the GLUT3 or the signal transduction mechanism(s) promoting recruitment in each of these cells. In the case of platelets, EM studies of Heijnen et al. (50) demonstrated that GLUT3-containing vesicles are the α-granules that contain the adhesion factor P-selectin, and various growth factors including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), IGF-I, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. Analogous to the action of insulin in adipose cells, thrombin appears to mediate the recruitment of the α granules through a mechanism that clearly involves PI-3 kinase phosphorylation of Akt (35) (69). However, the mechanism appears to be augmented by a Ca2+-PKC phosphorylation of Akt. This can be mimicked by actions of PMA, which is able to stimulate transport activity in lymphocytes and monocytes, as well as neutrophils and platelets, illustrated in Fig. 7 (38, 79, 83, 112). The α-granules would also appear to share the same SNARE molecules as GLUT4-containing vesicles (22, 36).

Fig. 7.

Immunolocalization of GLUT3 in resting and activated neutrophils by confocal microscopy. Phase contrast micrographs (A), corresponding to fluorescence micrographs (B), show the morphology of unstimulated (control) cells: characteristic multinucleated cells with thin cytoplasm. In these cells, GLUT3 (B) exhibits punctate intracellular staining, which appears dispersed throughout the cytoplasm. Phase contrast (C) and corresponding fluorescent images (D) are presented from cells incubated with 100 nM PMA for 10 min. In response to PMA, GLUT3 displays clear redistribution to the cell surface from intracellular locations (D). Intensity of fluorescence at the cell surface remains below that observed over the platelet in the same field (arrow in D). Phase contrast micrographs (E and G) and corresponding fluorescence images (F and H) are presented for cells incubated with bacteria for 20 and 30 min, respectively. Striking morphological changes can be observed during cell activation: cells are larger and have more cytoplasm and large expansions of their plasma membrane; phagocytosed bacteria are seen inside most cells. These morphological changes are accompanied by marked redistribution of GLUT3 immunofluorescence from intracellular locations toward the cell surface, outlining the cell periphery and spike-like plasma membrane projections (E and F). Very bright intracellular spots appear to correspond to phase-dense membrane compartments (arrows in G and H). Platelets (small arrows in G and H) have much lower intensity of fluorescence than observed when activated in D. Bars, 5 μm (D. Malide, I. A. Simpson, and M. Levine, unpublished observations).

In each of the cell types the translocation of GLUT3 is in response to a substantial increase in energy need associated with cell activation. In the case of platelets, the action of thrombin induces a cascade of energy-dependent events: actin polymerization, changes in platelet shape, aggregation and secretion of α- and dense vesicles, and ultimately aggregation and clot formation. These processes rapidly triple the expenditure of ATP, which, due to the relative paucity of mitochondria, must be replenished by glycolysis. In addition, the absence of blood flow and thus low prevailing glucose clearly favors the kinetic characteristics of GLUT3 to mediate glucose uptake (2, 3). Neutrophils upon activation, and monocytes upon transformation to macrophages, also undergo dramatic shape and size changes to facilitate phagocytosis of bacteria and senescent cells. The elimination of the bacteria involves the phagocytosis of the organism, the generation of prodigious numbers of superoxide molecules to kill the organism, and an array of lysosomal hydrolases to digest the phagocytosed body. Upon activation, lymphocytes also undergo dramatic changes in size, shape, and protein content. In the case of B-cells, they become enlarged immunoglobulin-synthesizing factories, whereas T-cells undergo conformational changes to accommodate antigen presentation and polarized release of cytokines or perforins. Both cell types also undergo extremely rapid proliferation (18, 61, 124).

GLUT3: What Is in the Future

We have clearly moved beyond thinking of GLUT3 as solely a neuronal glucose transporter to appreciate that it is expressed in a variety of cell types with very specific, and high, energy needs. We know that in the neuron, which is not a rapidly turning-over cell, both acute and chronic changes in energy demand and glucose utilization result in changes in GLUT3 expression. In cells with short half-lives, such as circulating human white cells, changes in energy demand seem to be met by translocation of GLUT3 rather than changes in expression/concentration. Although the signal transduction and translocation mechanism(s) appear similar to those employed by GLUT4, they are clearly distinct and warrant further investigation. In the case of neurons and sperm, where pronounced intracellular pools of GLUT3 are not apparent such that translocation is unlikely, the question arises as to whether there are other mechanisms of GLUT3 activation to account for the rapid changes in transport activity occurring during seizures (neuron) and capacitation (sperm), such as movement in and out of lipid rafts as seen for GLUT1 (13, 105). In the mouse blastocyst, the level of GLUT3 expression appears to direct proper trafficking of GLUT1 to the plasma membrane (42), implying a role for GLUT3 in the trafficking of other GLUTs in the same cell.

There is still much to be learned about the regulation of this vital transporter isoform. For example, it remains to be determined which factors actually regulate expression in response to metabolic demand in the neurons at both the transcriptional and translational levels. We know that GLUT3 responds to hypoxia through Hif in a variety of cells, including neurons, carcinomas and monocytes, but what other factors regulate expression in response to metabolic demand remain to be determined (11, 14, 87, 129). Studies have also demonstrated that transcriptional regulation of GLUT3 in neurons depends on both the stage of differentiation and the function of the cell. This work suggests that nuclear factors Sp1/Sp3 may mediate the transcriptional activation of GLUT3 along with MSY-1 during neurodevelopment; whereas phosphorylated cAMP regulatory element-binding (pCREB) protein may regulate transactivation of GLUT3 expression during neurotransmission under conditions of substrate deficiency (104). Furthermore, posttranscriptional regulation of GLUT3 protein expression occurs in term placenta, suggesting a tight regulation of expression dependent on environmental conditions in the developing placenta (33). In the preimplantation embryo, a pulse of glucose or glucosamine for 1–2 h prior to compaction is necessary to induce expression of GLUT3 and thus to progress through normal development (101).

Furthermore, there are in vivo situations in which acute activation is associated with an increase in mRNA expression, which may or may not be translated into protein (95). The physiological value of this response of GLUT3, as well as potential regulators of both transcription and translation (65), are targets for future research.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-070351 and HD-040810 (K. H. Moley), HD-045664 and RR-00188 (A. Travis), NS-041405 and DK-075130 (I. A. Simpson), and ADA 1-05-RA-139 and AHA 0575055N (S. J. Vannucci).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aghajanian GK, Bloom FE. The formation of synaptic junctions in developing rat brain: a quantitative electron microscopic study. Brain Res 6: 716–727, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akkerman JW, Holmsen H. Interrelationships among platelet responses: studies on the burst in proton liberation, lactate production, and oxygen uptake during platelet aggregation and Ca2+ secretion. Blood 57: 956–966, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akkerman JWN Platelet Responses and Metabolism, edited by Holmsen H. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 1987, p. 190–206.

- 4.Angulo C, Rauch MC, Droppelmann A, Reyes AM, Slebe JC, Delgado-Lopez F, Guaiquil VH, Vera JC, Concha II. Hexose transporter expression and function in mammalian spermatozoa: cellular localization and transport of hexoses and vitamin C. J Cell Biochem 71: 189–203, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apelt J, Mehlhorn G, Schliebs R. Insulin-sensitive GLUT4 glucose transporters are colocalized with GLUT3-expressing cells and demonstrate a chemically distinct neuron-specific localization in rat brain. J Neurosci Res 57: 693–705, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbuckle MI, Kane S, Porter LM, Seatter MJ, Gould GW. Structure-function analysis of liver-type (GLUT2) and brain-type (GLUT3) glucose transporters: expression of chimeric transporters in Xenopus oocytes suggests an important role for putative transmembrane helix 7 in determining substrate selectivity. Biochemistry 35: 16519–16527, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arluison M, Quignon M, Nguyen P, Thorens B, Leloup C, Penicaud L. Distribution and anatomical localization of the glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) in the adult rat brain—an immunohistochemical study. J Chem Neuroanat 28: 117–136, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arluison M, Quignon M, Thorens B, Leloup C, Penicaud L. Immunocytochemical localization of the glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) in the adult rat brain. II. Electron microscopic study. J Chem Neuroanat 28: 137–146, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asano T, Katagiri H, Takata K, Lin JL, Ishihara H, Inukai K, Tsukuda K, Kikuchi M, Hirano H, Yazaki Y, Oka Y. The role of N-glycosylation of GLUT1 for glucose transport activity. J Biol Chem 266: 24632–24636, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21: 1133–1145, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badr GA, Zhang JZ, Tang J, Kern TS, Ismail-Beigi F. Glut1 and glut3 expression, but not capillary density, is increased by cobalt chloride in rat cerebrum and retina. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 64: 24–33, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bady I, Marty N, Dallaporta M, Emery M, Gyger J, Tarussio D, Foretz M, Thorens B. Evidence from glut2-null mice that glucose is a critical physiological regulator of feeding. Diabetes 55: 988–995, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes K, Ingram JC, Bennett MD, Stewart GW, Baldwin SA. Methyl-beta-cyclodextrin stimulates glucose uptake in Clone 9 cells: a possible role for lipid rafts. Biochem J 378: 343–351, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann MU, Zamudio S, Illsley NP. Hypoxic upregulation of glucose transporters in BeWo choriocarcinoma cells is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C477–C485, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell GI, Murray JC, Nakamura Y, Kayano T, Eddy RL, Fan YS, Byers MG, Shows TB. Polymorphic human insulin-responsive glucose-transporter gene on chromosome 17p13. Diabetes 38: 1072–1075, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilan PJ, Mitsumoto Y, Maher F, Simpson IA, Klip A. Detection of the GLUT3 facilitative glucose transporter in rat L6 muscle cells: regulation by cellular differentiation, insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 186: 1129–1137, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birnbaum MJ Identification of a novel gene encoding an insulin-responsive glucose transporter protein. Cell 57: 305–315, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boes M, Ploegh HL. Translating cell biology in vitro to immunity in vivo. Nature 430: 264–271, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bondy CA, Lee W, Zhou J. Ontogeny and cellular distribution of brain glucose transporter gene expression. Mol Cell Neurosci 3: 305–314, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao W, Gerton GL, Moss SB. Proteomic profiling of accessory structures from the mouse sperm flagellum. Mol Cell Proteomics 5: 801–810, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson D, Black DL, Howe GR. Oviduct secretion in the cow. J Reprod Fertil 22: 549–552, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chamberlain LH, Gould GW. The vesicle- and target-SNARE proteins that mediate Glut4 vesicle fusion are localized in detergent-insoluble lipid rafts present on distinct intracellular membranes. J Biol Chem 277: 49750–49754, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charron MJ, Brosius FC, Alper SL, Lodish HF. A glucose transport protein expressed predominately in insulin-responsive tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 2535–2539, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatot CL, Lewis-Williams J, Torres I, Ziomek CA. One-minute exposure of 4-cell mouse embryos to glucose overcomes morula block in CZB medium. Mol Reprod Dev 37: 407–412, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chi MM, Hoehn A, Moley KH. Metabolic changes in the glucose-induced apoptotic blastocyst suggest alterations in mitochondrial physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283: E226–E232, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craik JD, Stewart M, Cheeseman CI. GLUT-3 (brain-type) glucose transporter polypeptides in human blood platelets. Thromb Res 79: 461–469, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daneman D, Zinman B, Elliott ME, Bilan PJ, Klip A. Insulin-stimulated glucose transport in circulating mononuclear cells from nondiabetic and IDDM subjects. Diabetes 41: 227–234, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Santi S, de Leon MJ, Rusinek H, Convit A, Tarshish CY, Roche A, Tsui WH, Kandil E, Boppana M, Daisley K, Wang GJ, Schlyer D, Fowler J. Hippocampal formation glucose metabolism and volume losses in MCI and AD. Neurobiol Aging 22: 529–539, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duara R, Grady C, Haxby J, Sundaram M, Cutler NR, Heston L, Moore A, Schlageter N, Larson S, Rapoport SI. Positron emission tomography in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 36: 879–887, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duelli R, Kuschinsky W. Brain glucose transporters: relationship to local energy demand. News Physiol Sci 16: 71–76, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duelli R, Maurer MH, Heiland S, Elste V, Kuschinsky W. Brain water content, glucose transporter densities and glucose utilization after 3 days of water deprivation in the rat. Neurosci Lett 271: 13–16, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dwyer DS Model of the 3-D structure of the GLUT3 glucose transporter and molecular dynamics simulation of glucose transport. Proteins 42: 531–541, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esterman A, Greco MA, Mitani Y, Finlay TH, Ismail-Beigi F, Dancis J. The effect of hypoxia on human trophoblast in culture: morphology, glucose transport and metabolism. Placenta 18: 129–136, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Estrada DE, Elliott E, Zinman B, Poon I, Liu Z, Klip A, Daneman D. Regulation of glucose transport and expression of GLUT3 transporters in human circulating mononuclear cells: studies in cells from insulin-dependent diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. Metabolism 43: 591–598, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferreira IA, Mocking AI, Urbanus RT, Varlack S, Wnuk M, Akkerman JW. Glucose uptake via glucose transporter 3 by human platelets is regulated by protein kinase B. J Biol Chem 280: 32625–32633, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaumenhaft R Molecular basis of platelet granule secretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1152–1160, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedland RP, Jagust WJ, Huesman RH, Koss E, Knittel B, Mathis CA, Ober BA, Mazoyer BM, Budinger TF. Regional cerebral glucose transport and utilization in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 39: 1427–1434, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fu Y, Maianu L, Melbert BR, Garvey WT. Facilitative glucose transporter gene expression in human lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages: a role for GLUT isoforms 1, 3, and 5 in the immune response and foam cell formation. Blood Cells Mol Dis 32: 182–190, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukumoto H, Kayano T, Buse JB, Edwards Y, Pilch PF, Bell GI, Seino S. Cloning and characterization of the major insulin-responsive glucose transporter expressed in human skeletal muscle and other insulin-responsive tissues. J Biol Chem 264: 7776–7779, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gainer H, Wray S. Celluar and Molecular Biology of Oxytocin and Vassopressin. New York: Raven, 1994.

- 41.Galantino-Homer HL, Florman HM, Storey BT, Dobrinski I, Kopf GS. Bovine sperm capacitation: assessment of phosphodiesterase activity and intracellular alkalinization on capacitation-associated protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Reprod Dev 67: 487–500, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganguly A, McKnight RA, Raychaudhuri S, Shin BC, Ma Z, Moley K, Devaskar SU. Glucose transporter isoform-3 mutations cause early pregnancy loss and fetal growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E1241–E1255, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardner HG, Kaye PL. Characterization of glucose transport in preimplantation mouse embryos. Reprod Fertil Dev 7: 41–50, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerhart DZ, Leino RL, Borson ND, Taylor WE, Gronlund KM, McCall AL, Drewes LR. Localization of glucose transporter GLUT 3 in brain: comparison of rodent and dog using species-specific carboxyl-terminal antisera. Neuroscience 66: 237–246, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerhart DZ, Leino RL, Taylor WE, Borson ND, Drewes LR. GLUT1 and GLUT3 gene expression in gerbil brain following brief ischemia: an in situ hybridization study. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 25: 313–322, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gould GW, Holman GD. The glucose transporter family: structure, function and tissue-specific expression. Biochem J 295: 329–341, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gould GW, Thomas HM, Jess TJ, Bell GI. Expression of human glucose transporters in Xenopus oocytes: kinetic characterization and substrate specificities of the erythrocyte, liver, and brain isoforms. Biochemistry 30: 5139–5145, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haber RS, Weinstein SP, O'Boyle E, Morgello S. Tissue distribution of the human GLUT3 glucose transporter. Endocrinology 132: 2538–2543, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hahn D, Blaschitz A, Korgun ET, Lang I, Desoye G, Skofitsch G, Dohr G. From maternal glucose to fetal glycogen: expression of key regulators in the human placenta. Molecular human reproduction 7: 1173–1178, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heijnen HF, Oorschot V, Sixma JJ, Slot JW, James DE. Thrombin stimulates glucose transport in human platelets via the translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT-3 from alpha-granules to the cell surface. J Cell Biol 138: 323–330, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogan A, Heyner S, Charron MJ, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Thorens B, Schultz GA. Glucose transporter gene expression in early mouse embryos. Development 113: 363–372, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Illsley NP, Sellers MC, Wright RL. Glycaemic regulation of glucose transporter expression and activity in the human placenta. Placenta 19: 517–524, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobs DB, Lee TP, Jung CY, Mookerjee BK. Mechanism of mitogen-induced stimulation of glucose transport in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Evidence of an intracellular reserve pool of glucose carriers and their recruitment. J Clin Invest 83: 437–443, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jagust WJ, Seab JP, Huesman RH, Valk PE, Mathis CA, Reed BR, Coxson PG, Budinger TF. Diminished glucose transport in Alzheimer's disease: dynamic PET studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 11: 323–330, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.James DE, Brown R, Navarro J, Pilch PF. Insulin-regulatable tissues express a unique insulin-sensitive glucose transport protein. Nature 333: 183–185, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James DE, Strube M, Mueckler M. Molecular cloning and characterization of an insulin-regulatable glucose transporter. Nature 338: 83–87, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kadekaro M, Summy-Long JY, Freeman S, Harris JS, Terrell ML, Eisenberg HM. Cerebral metabolic responses and vasopressin and oxytocin secretions during progressive water deprivation in rats [erratum appears in Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 262 (6 Pt. 5), following Table of Contents]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 262: R310–R317, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaestner KH, Christy RJ, Lane MD. Mouse insulin-responsive glucose transporter gene: characterization of the gene and trans-activation by the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 251–255, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalaria RN, Harik SI. Abnormalities of the glucose transporter at the blood-brain barrier and in brain in Alzheimer's disease. Prog Clin Biol Res 317: 415–421, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalaria RN, Harik SI. Reduced glucose transporter at the blood-brain barrier and in cerebral cortex in Alzheimer disease. J Neurochem 53: 1083–1088, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaur A, Hale CL, Ramanujan S, Jain RK, Johnson RP. Differential dynamics of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-lymphocyte proliferation and activation in acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol 74: 8413–8424, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kayano T, Fukumoto H, Eddy RL, Fan YS, Byers MG, Shows TB, Bell GI. Evidence for a family of human glucose transporter-like proteins. Sequence and gene localization of a protein expressed in fetal skeletal muscle and other tissues. J Biol Chem 263: 15245–15248, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keller K, Strube M, Mueckler M. Functional expression of the human HepG2 and rat adipocyte glucose transporters in Xenopus oocytes. Comparison of kinetic parameters. J Biol Chem 264: 18884–18889, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khan JY, Rajakumar RA, McKnight RA, Devaskar UP, Devaskar SU. Developmental regulation of genes mediating murine brain glucose uptake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R892–R900, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khayat ZA, McCall AL, Klip A. Unique mechanism of GLUT3 glucose transporter regulation by prolonged energy demand: increased protein half-life. Biochem J 333: 713–718, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim ST, Moley KH. The expression of GLUT8, GLUT9a, and GLUT9b in the mouse testis and sperm. Reprod Sci 14: 445–455, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kobayashi M, Nikami H, Morimatsu M, Saito M. Expression and localization of insulin-regulatable glucose transporter (GLUT4) in rat brain. Neurosci Lett 213: 103–106, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koehler-Stec EM, Li K, Maher F, Vannucci SJ, Smith CB, Simpson IA. Cerebral glucose utilization and glucose transporter expression: response to water deprivation and restoration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 20: 192–200, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kroner C, Eybrechts K, Akkerman JW. Dual regulation of platelet protein kinase B. J Biol Chem 275: 27790–27798, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee WH, Bondy CA. Ischemic injury induces brain glucose transporter gene expression. Endocrinology 133: 2540–2544, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leino RL, Gerhart DZ, van Bueren AM, McCall AL, Drewes LR. Ultrastructural localization of GLUT 1 and GLUT 3 glucose transporters in rat brain. J Neurosci Res 49: 617–626, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leloup C, Arluison M, Kassis N, Lepetit N, Cartier N, Ferre P, Penicaud L. Discrete brain areas express the insulin-responsive glucose transporter GLUT4. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 38: 45–53, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lowe AG, Walmsley AR. The kinetics of glucose transport in human red blood cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 857: 146–154, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Magistretti PJ, Pellerin L. Metabolic coupling during activation. A cellular view. Adv Exp Med Biol 413: 161–166, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maher F Immunolocalization of GLUT1 and GLUT3 glucose transporters in primary cultured neurons and glia. J Neurosci Res 42: 459–469, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maher F, Davies-Hill TM, Simpson IA. Substrate specificity and kinetic parameters of GLUT3 in rat cerebellar granule neurons. Biochem J 315: 827–831, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maher F, Simpson IA. The GLUT3 glucose transporter is the predominant isoform in primary cultured neurons: assessment by biosynthetic and photoaffinity labelling. Biochem J 301: 379–384, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maher F, Davies-Hill T, Lysko P, Henneberry RC, Simpson IA. Expression of two glucose transporter, GLUT1 and GLUT3 in cultured cerebellar neurons: Evidence for neuron specific expression of GLUT3. Mol Cell Neurosci 2: 351–360, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Malide D, Davies-Hill TM, Levine M, Simpson IA. Distinct localization of GLUT-1, -3, and -5 in human monocyte-derived macrophages: effects of cell activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E516–E526, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mann T The Biochemistry of Semen and of the Male Reproductive Tract. New York: Wiley and Sons, 1964.

- 81.Manolescu AR, Witkowska K, Kinnaird A, Cessford T, Cheeseman C. Facilitated hexose transporters: new perspectives on form and function. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 234–240, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mantych GJ, James DE, Chung HD, Devaskar SU. Cellular localization and characterization of Glut 3 glucose transporter isoform in human brain. Endocrinology 131: 1270–1278, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maratou E, Dimitriadis G, Kollias A, Boutati E, Lambadiari V, Mitrou P, Raptis SA. Glucose transporter expression on the plasma membrane of resting and activated white blood cells. Eur J Clin Invest 37: 282–290, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCall AL, Van Bueren AM, Moholt-Siebert M, Cherry NJ, Woodward WR. Immunohistochemical localization of the neuron-specific glucose transporter (GLUT3) to neuropil in adult rat brain. Brain Res 659: 292–297, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McEwen BS, Reagan LP. Glucose transporter expression in the central nervous system: relationship to synaptic function. Eur J Pharmacol 490: 13–24, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miki K, Qu W, Goulding EH, Willis WD, Bunch DO, Strader LF, Perreault SD, Eddy EM, AOBD. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase-S, a sperm-specific glycolytic enzyme, is required for sperm motility and male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 16501–16506, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mobasheri A, Richardson S, Mobasheri R, Shakibaei M, Hoyland JA. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 and facilitative glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3: putative molecular components of the oxygen and glucose sensing apparatus in articular chondrocytes. Histol Histopathol 20: 1327–1338, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moley KH, Chi MM, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Mueckler MM. Hyperglycemia induces apoptosis in pre-implantation embryos through cell death effector pathways. Nat Med 4: 1421–1424, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moley KH, Chi MM, Mueckler MM. Maternal hyperglycemia alters glucose transport and utilization in mouse preimplantation embryos. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E38–E47, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mori C, Nakamura N, Welch JE, Gotoh H, Goulding EH, Fujioka M, Eddy EM. Mouse spermatogenic cell-specific type 1 hexokinase (mHk1-s) transcripts are expressed by alternative splicing from the mHk1 gene and the HK1-S protein is localized mainly in the sperm tail. Mol Reprod Dev 49: 374–385, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mukai C, Okuno M. Glycolysis plays a major role for adenosine triphosphate supplementation in mouse sperm flagellar movement. Biol Reprod 71: 540–547, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagamatsu S, Kornhauser JM, Burant CF, Seino S, Mayo KE, Bell GI. Glucose transporter expression in brain. cDNA sequence of mouse GLUT3, the brain facilitative glucose transporter isoform, and identification of sites of expression by in situ hybridization. J Biol Chem 267: 467–472, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nehlig A Respective roles of glucose and ketone bodies as substrates for cerebral energy metabolism in the suckling rat. Dev Neurosci 18: 426–433, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nehlig A, Pereira de Vasconcelos A. Glucose and ketone body utilization by the brain of neonatal rats. Prog Neurobiol 40: 163–221, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nehlig A, Rudolf G, Leroy C, Rigoulot MA, Simpson IA, Vannucci SJ. Pentylenetetrazol-induced status epilepticus up-regulates the expression of glucose transporter mRNAs but not proteins in the immature rat brain. Brain Res 1082: 32–42, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nishimura H, Pallardo FV, Seidner GA, Vannucci S, Simpson IA, Birnbaum MJ. Kinetics of GLUT1 and GLUT4 glucose transporters expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 268: 8514–8520, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ogura K, Sakata M, Okamoto Y, Yasui Y, Tadokoro C, Yoshimoto Y, Yamaguchi M, Kurachi H, Maeda T, Murata Y. 8-Bromo-cyclicAMP stimulates glucose transporter-1 expression in a human choriocarcinoma cell line. J Endocrinol 164: 171–178, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palfreyman RW, Clark AE, Denton RM, Holman GD, Kozka IJ. Kinetic resolution of the separate GLUT1 and GLUT4 glucose transport activities in 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem J 284: 275–282, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pantaleon M, Harvey MB, Pascoe WS, James DE, Kaye PL. Glucose transporter GLUT3: ontogeny, targeting, and role in the mouse blastocyst. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 3795–3800, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pantaleon M, Ryan JP, Gil M, Kaye PL. An unusual subcellular localization of GLUT1 and link with metabolism in oocytes and preimplantation mouse embryos. Biol Reprod 64: 1247–1254, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pantaleon M, Scott J, Kaye PL. Nutrient Sensing by the Early Mouse Embryo: Hexosamine Biosynthesis and Glucose Signaling During Preimplantation Development. Biol Reprod 78: 595–600, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Parrish JJ, Susko-Parrish JL, First NL. Capacitation of bovine sperm by heparin: Inhibitory effect of glucose and role of intracellular pH. Biol Reprod 41: 683–699, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. Food for thought: challenging the dogmas. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23: 1282–1286, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rajakumar A, Thamotharan S, Raychaudhuri N, Menon RK, Devaskar SU. Trans-activators regulating neuronal glucose transporter isoform-3 gene expression in mammalian neurons. J Biol Chem 279: 26768–26779, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rauch MC, Ocampo ME, Bohle J, Amthauer R, Yanez AJ, Rodriguez-Gil JE, Slebe JC, Reyes JG, Concha II. Hexose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT3 are colocalized with hexokinase I in caveolae microdomains of rat spermatogenic cells. J Cell Physiol 207: 397–406, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rayner DV, Thomas ME, Trayhurn P. Glucose transporters (GLUTs 1–4) and their mRNAs in regions of the rat brain: insulin-sensitive transporter expression in the cerebellum [published erratum appears in Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 1098, 1994]. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 72: 476–479, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shepherd PR, Gould GW, Colville CA, McCoid SC, Gibbs EM, Kahn BB. Distribution of GLUT3 glucose transporter protein in human tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 188: 149–154, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Simpson IA, Carruthers A, Vannucci SJ. Supply and demand in cerebral energy metabolism: the role of nutrient transporters. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27: 1766–1791, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Simpson IA, Chundu KR, Davies-Hill T, Honer WG, Davies P. Decreased concentrations of GLUT1 and GLUT3 glucose transporters in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease [see comments]. Ann Neurol 35: 546–551, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smith DE, Gridley T. Differential screening of a PCR-generated mouse embryo cDNA library: glucose transporters are differentially expressed in early postimplantation mouse embryos. Development 116: 555–561, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem 28: 897–916, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sorbara LR, Davies-Hill TM, Koehler-Stec EM, Vannucci SJ, Horne MK, Simpson IA. Thrombin-induced translocation of GLUT3 glucose transporters in human platelets. Biochem J 328: 511–516, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Storey BT, Kayne FJ. Energy metabolism of spermatozoa. V. The Embden-Myerhoff pathway of glycolysis: activities of pathway enzymes in hypotonically treated rabbit epididymal spermatozoa. Fertil Steril 26: 1257–1265, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tiedge H, Zhou A, Thorn NA, Brosius J. Transport of BC1 RNA in hypothalamo-neurohypophyseal axons. J Neurosci 13: 4214–4219, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Travis AJ, Foster JA, Rosenbaum NA, Visconti PE, Gerton GL, Kopf GS, Moss SB. Targeting of a germ cell-specific type 1 hexokinase lacking a porin- binding domain to the mitochondria as well as to the head and fibrous sheath of murine spermatozoa. Mol Biol Cell 9: 263–276, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Travis AJ, Jorgez CJ, Merdiushev T, Jones BH, Dess DM, Diaz-Cueto L, Storey BT, Kopf GS, Moss SB. Functional relationships between capacitation-dependent cell signaling and compartmentalized metabolic pathways in murine spermatozoa. J Biol Chem 276: 7630–7636, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Travis AJ, Kopf GS. The role of cholesterol efflux in regulating the fertilization potential of mammalian spermatozoa. J Clin Invest 110: 731–736, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Travis AJ, Kopf GS. The spermatozoon as a machine: compartmentalized pathways bridge cellular structure and function. In: Assisted Reproductive Technology: Accomplishments and New Horizons, edited by De Jonge CJ and Barratt CL. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002, p. 26–39.

- 119.Travis AJ, Tutuncu L, Jorgez CJ, Ord TS, Jones BH, Kopf GS, Williams CJ. Requirements for glucose beyond sperm capacitation during in vitro fertilization in the mouse. Biol Reprod 71: 139–145, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Trembleau A, Morales M, Bloom FE. Differential compartmentalization of vasopressin messenger RNA and neuropeptide within the rat hypothalamo-neurohypophysial axonal tracts: light and electron microscopic evidence. Neuroscience 70: 113–125, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Uldry M, Thorens B. The SLC2 family of facilitated hexose and polyol transporters. Pflügers Arch 447: 480–489, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Urner F, Sakkas D. A possible role for the pentose phosphate pathway of spermatozoa in gamete fusion in the mouse. Biol Reprod 60: 733–739, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Urner F, Sakkas D. Glucose participates in sperm-oocyte fusion in the mouse. Biol Reprod 55: 917–922, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.van Stipdonk MJ, Hardenberg G, Bijker MS, Lemmens EE, Droin NM, Green DR, Schoenberger SP. Dynamic programming of CD8+ T lymphocyte responses. Nat Immunol 4: 361–365, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vannucci SJ, Clark RR, Koehler-Stec E, Li K, Smith CB, Davies P, Maher F, Simpson IA. Glucose transporter expression in brain: relationship to cerebral glucose utilization. Dev Neurosci 20: 369–379, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vannucci SJ, Koehler-Stec EM, Li K, Reynolds TH, Clark R, Simpson IA. GLUT4 glucose transporter expression in rodent brain: effect of diabetes. Brain Res 797: 1–11, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vannucci SJ, Maher F, Koehler E, Simpson IA. Altered expression of GLUT-1 and GLUT-3 glucose transporters in neurohypophysis of water-deprived or diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 267: E605–E611, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Vannucci SJ, Maher F, Simpson IA. Glucose transporter proteins in brain: delivery of glucose to neurons and glia. Glia 21: 2–21, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vannucci SJ, Reinhart R, Maher F, Bondy CA, Lee WH, Vannucci RC, Simpson IA. Alterations in GLUT1 and GLUT3 glucose transporter gene expression following unilateral hypoxia-ischemia in the immature rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 107: 255–264, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wang D, Pascual JM, Yang H, Engelstad K, Mao X, Cheng J, Yoo J, Noebels JL, De Vivo DC. A mouse model for Glut-1 haploinsufficiency. Hum Mol Genet 15: 1169–1179, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Werner H, Raizada MK, Mudd LM, Foyt HL, Simpson IA, Roberts CT Jr, LeRoith D. Regulation of rat brain/HepG2 glucose transporter gene expression by insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I in primary cultures of neuronal and glial cells. Endocrinology 125: 314–320, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Westhoff D, Kamp G. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase is bound to the fibrous sheath of mammalian spermatozoa. J Cell Sci 110: 1821–1829, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]