Abstract

The biological role of macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue in obesity remains to be fully understood. We hypothesize that macrophages may act to stimulate angiogenesis in the adipose tissue. This possibility was examined by determining macrophage expression of angiogenic factor PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) and regulation of tube formation of endothelial cells by PDGF. The data suggest that endothelial cell density was reduced in the adipose tissue of ob/ob mice. Expression of endothelial marker CD31 was decreased in protein and mRNA. The reduction was associated with an increase in macrophage infiltration. In the obese mice, PDGF concentration was elevated in the plasma, and its mRNA expression was increased in adipose tissue. Macrophages were found to be a major source of PDGF in adipose tissue, as deletion of macrophages led to a significant reduction in PDGF mRNA. In cell culture, PDGF expression was induced by hypoxia, and tube formation of endothelial cells was induced by PDGF. The PDGF activity was dependent on S6K, as inhibition of S6K in endothelial cells led to inhibition of the PDGF activity. We conclude that, in response to the reduced vascular density, macrophages may express PDGF in adipose tissue to facilitate capillary formation in obesity. Although the PDGF level is elevated in adipose tissue, its activity in angiogenesis is dependent on the availability of sufficient endothelial cells. The study suggests a new function of macrophages in the adipose tissue in obesity.

Keywords: macrophage, platelet-derived growth factor, angiogenesis, ribosomal protein S6 kinase, hypoxia, obesity

tissue remodeling is involved in the expansion of adipose tissue during body weight gain. Angiogenesis is a critical event in tissue remodeling. Angiogenesis may be coupled with adipogenesis during adipose tissue remodeling throughout lifetime (11, 28, 33, 34). The increase in adipocyte size is associated with compensation in the microcirculation, as has been reviewed (5, 11). Inhibition of angiogenesis prevents fat mass expansion in several rodent models of obesity (6, 41). In addition to the well-known adipokines (including adiponectin, leptin, TNF-α, and resistin), adipose tissue also produces a variety of endothelial cell growth factors and angiogenic factors (11), such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor (PD-ECGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and angiopoietin. The functions of these factors are demonstrated in experimental angiogenesis assays with conditioned media obtained from preadipocytes and tissue homogenates of fat tissues (8, 17, 44). The factor that induces expression of the angiogenic factors or vascular compensation remains to be identified in adipose tissue. In a recent study, we demonstrated hypoxia in the adipose tissue in ob/ob and dietary obese mice (56). Adipose tissue hypoxia may play a role in the induction of these angiogenic factors. Cross-talk between adipocytes and endothelial cells has been supported by many studies and is required for adipose tissue growth (8, 27, 34, 50). However, not much is known about cross-talk between macrophages and endothelial cells in adipose tissue in tissue growth or remodeling.

Macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue contributes to the increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in obesity (52, 55). It remains to be investigated why macrophage infiltration is increased in adipose tissue. Some studies suggest that macrophage infiltration is for clearance of dead adipocytes in the adipose tissue (10, 45). Except for chronic inflammation and clearance of dead cells, the biological significance of macrophage infiltration remains largely unknown in the adipose tissue. In wound healing and tumor growth, macrophage infiltration contributes to the stimulation of angiogenesis (46). Such a role of macrophages remains to be established in adipose tissue remodeling in obesity. We hypothesized that macrophage infiltration might be involved in the stimulation of angiogenesis during expansion of adipose tissue.

As a proangiogenic factor in serum, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates differentiation of endothelial cells and migration of pericytes (21, 22, 29, 40). Although PDGF is secreted by many types of cells, including platelets, macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, macrophages are one of the major sources of PDGF in tissues (32, 43). Among the three active isoforms of PDGF (AA, AB, and BB), PDGF-BB is able to activate all of the three PDGF receptors (αα, αβ, and ββ), which are dimeric tyrosine kinases. The importance of PDGF in the regulation of vascular development and function was demonstrated in gene knockout mice in which inactivation of either PDGF-B or its receptor was embryonically lethal (29). The mice died from hemorrhage, edema, and absence of kidney glomerular mesangial cells. In addition to the regulation of vascular development, PDGF is also involved in oncogenesis, atherosclerosis, lung fibrosis, kidney fibrosis, etc. (20). Although PDGF expression is elevated locally in tissue remodeling processes such as wound healing and tumor growth, it is not clear whether PDGF expression is increased during adipose tissue growth in obesity. As hypoxia induces PDGF expression (16), we propose that PDGF expression may be increased by adipose tissue hypoxia and may be involved in stimulation of angiogenesis during adipose tissue remodeling in obesity.

The angiogenic activities of PDGF are mediated by signaling pathways of cell membrane receptors of PDGF (47). Ligand engagement leads to PDGF receptor phosphorylation and activation of several signaling pathways, including Src, PI3K, and phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) (47). The phophatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is activated by PDGF (25, 58) and is involved in the recruitment of pericytes (13). It remains to be tested whether the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is involved in tube formation of endothelial cells in response to PDGF. In studies of other angiogenic factors, the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was reported to stimulate proliferation (51) and tube formation of vascular endothelial cells (57). However, there is no direct evidence that this signaling pathway is required by PDGF in the stimulation of tube formation.

In this study, we demonstrated that vascular density was reduced in adipose tissue in ob/ob mice. PDGF expression was elevated in adipose tissue and expressed in macrophages. In cell culture, PDGF stimulated tube formation of endothelial cells, and the activity required ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K). These data suggest that macrophage PDGF may play an important role in the stimulation of tube formation in the process of angiogenesis in adipose tissue. The study provides direct evidence for the role of the PI3K/mTOR/S6K signaling pathway in the PDGF-induced tube formation.

EXPERIMENT PROCEDURES

Animals.

Male C57BL/6J-Lepob, and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) at 6 wk of age and used in the study according to the animal protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State university (Baton Rouge, LA). The mice were housed in regular cage with four mice per cage with free access to water and standard chow unless noted otherwise. The serum of the mice was collected from the tail vein. The serum level of PDGF was quantified with a Mouse/Rat PDGF-BB Immunoassay kit (MBB00; R&D Systems).

Cell lines and reagents.

Murine endothelial cell line SVEC4-10 (CRL-2181, ATCC), murine fibroblast cell line 3T3-L1 (CL-173, ATCC), and the RAW 264.7 cell line (TIB-71) were maintained in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum in a CO2 (5%) incubator. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated into adipocytes as described elsewhere (15). Antibodies to phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr421/Ser424, 9204) and phospho-Akt (Ser473, 9271) were obtained from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA). Antibodies to PDGF-BB (ab53716), phospho-glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β (Ser9, ab30619), GSK-3β (ab31366), S6K (ab9366), tubulin (ab7291), and actin (ab8227) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies to HA (sc-7392) and Akt1 (sc-8312) were bought from Santa Cruz Biotechnoloty (Santa Cruz, CA). Rapamycin (A275-0001), LY-294002 (ST-420), and SP-600125 (EI-305) were obtained from Biomol International (Plymouth Meeting, MA). Wortmannin (W1628) and SB-203580 (S8307) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). These reagents were diluted and added to the cells at indicated working concentrations.

Deletion of macrophages in adipose tissue.

Macrophages were deleted in the adipose tissue by a single injection of clodronate liposome. Clodronate liposome was prepared and administration at 100–150 mg/kg ip as described elsewhere (49). The macrophage deletion was confirmed in adipose tissue at day 4 after injection.

Tube formation assay.

Tube formation assay was conducted on the Matrigel (35027, BD Biosciences), which was added in a volume of 50 μl/well to a 96-well plate (3585, Fisher Scientific) and allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 30 min. After polymerization, the endothelial cells were plated on the Matrigel at 2 × 104 cells/well in 200 μl of serum-free medium with or without reagents. The cells were incubated at 37°C with 95% humidity and 5% CO2. The tube formation was observed under an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL) after 10 h. Images were captured with a Zeiss AxioCam Hrc CCD camera attached to the microscope. The tube formation was quantified by measuring the long axis of the individual cells on Matrigel using NIH Image J (version 1.31). A mean value of total length in each sample was used to represent the tube formation.

Protein extract and Western blot.

SVEC4-10 cells (5 × 105/well) were plated in a 12-well plate in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 24 h. Then the cells were starved overnight in serum-free medium and treated with various reagents for 30 min. Protein extraction and Western blot analysis were conducted for analysis of signaling activities in cells, as described elsewhere (15). The intensity of Western blot signal was quantified with NIH Image J, and the signal was normalized against loading control.

Generation of stable cell line with dominant-negative S6K mutant.

The SVEC4-10 endothelial cells were cotransfected with 3 μg of pRK7-HA-S6K1-KR plasmid for dominant-negative S6K (8985, Addgene) and 0.5 μg of pcDNA3.1 plasmid for neomycin resistance. In the control, the cells were transfected with pcDNA 3.1 plasmid. The transfection was conducted with Lipofectamine 2000 in 4.5 ml of medium. The transfected cells were cultured in G418 (300 mg/ml)-containing medium 36 h later for 24–28 days. The stable positive cells were confirmed in Western blot with HA antibody and S6K rabbit antibody. The positive cells were cultured in G418-free DMEM for two passages before experiment.

Cell viability (MTT) assay.

SVEC4-10 (1 × 104 cells/well) were plated in a 96-well plate in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Then the cells were starved overnight in a serum-free medium and treated with various reagents for 24 h. The MTT assay was conducted by incubation of the cells in 20 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) for 3–5 h. Cell viability was determined by formazan (MTT metabolic product), which was quantified with optical density at 560 nm in 200 μl of DMSO and normalized over the subtract background at 670 nm.

Hypoxia treatment.

Cells were treated with hypoxia (1% oxygen) in vitro, as described elsewhere (56). The control cells were maintained in normoxic condition. After treatment, the cell culture supernatant was collected as conditioned medium and stored at −80°C until experiments (30).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from homogenized fat pads or cells using Tri Reagent (T9424; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted using the ABI 7900HT fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The following primers and probes were ordered from Applied Biosystems: PDGF (Mm00437304_m1), CD31 (Mm01246167_m1), and F4/80 (Mm00802530_m1). The specific signal was normalized over 18S rRNA. A mean value of triplicates was used to express gene expression.

Immunohistochemistry.

The epididymal fat pads were isolated, fixed in neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Thin tissue slides (5 μm) were deparaffinized, blocked, and incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse anti-mouse CD31 antibody (ab24590; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), which was followed by signal amplification using a VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Kit (PK-6102; Vector Laboratories). The reaction was developed by addition of AEC chromogen substrate (AEC Staining Kit; Sigma-Aldrich). In fluorescence analysis, the CD31 signal was determined with goat anti-mouse IgG-FITC (sc-2010, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Microphotographs were taken under a microscope (×20).

Peritoneal macrophages.

Primary peritoneal macrophages were isolated from C57BL/6J mice, as described elsewhere (56). The macrophages were transferred to 35-mm tissue culture dishes and treated with hypoxia in serum-free medium 3 days later for collection of supernatant.

Statistical analysis.

All of the experiments were conducted at least three times with consistent results. The gel or image from representative experiment is presented. Values are means ± SE of multiple data points. Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA was used in statistical analysis of the data with a significance of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Decreased density of microvasculature in adipose tissue in ob/ob mice.

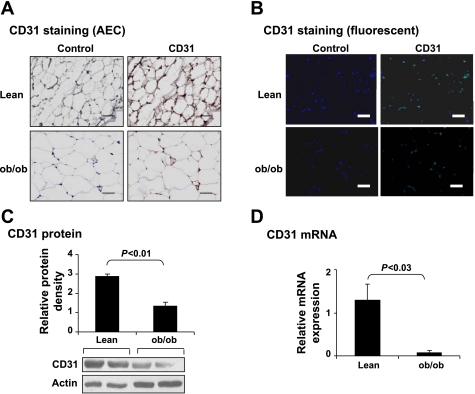

A decrease in capillary density has been proposed as a mechanism of blood flow reduction in adipose tissue in obesity. However, the reduction in capillary density is controversial (7, 23). One possible reason for the discrepancy is the quantification method for capillary density, which was determined by immunostaining in the studies (7, 23). To resolve the discrepancy, we compared capillary density in adipose tissues of lean mice and ob/ob mice via quantification of endothelial cell marker CD31. The CD31 protein was examined by immunostaining and Western blot. The CD31 mRNA was determined by qRT-PCR. In the immunohistostaining, the CD31 protein was detected in the tissue with either colorimetric- or fluorescence-based staining. CD31, distributed in the extracellular matrix of adipocytes, was reduced in obese mice (Fig. 1, A and B). The protein and mRNA of CD31 were both reduced in ob/ob mice (Fig. 1, C and D). These data suggest that neovascularization is reduced in white adipose tissue in obesity.

Fig. 1.

Vascular density decreased in adipose tissue in ob/ob mice. A and B: sections of epididymal fat pads were stained with CD31 antibody to reveal endothelial cell density. Immunohistostaining was conducted for the endothelial marker CD31. A: CD31 protein is indicated in red from AEC staining. B: CD31 protein is indicated in green fluorescent. Blue stands for nuclei stained by DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm. C: CD31 protein was determined in whole cell lysate of epididymal fat pads in Western blot. Representative blot is shown with an average signal strength in the bar figure. D: CD31 mRNA was determined in epididymal fat pads by qRT-PCR. In this figure, each data point represents mean ± SE (n = 5). Experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results.

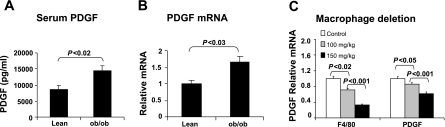

PDGF expression in adipose tissue of ob/ob mice.

To understand the reduction in capillary density, we examined PDGF activity in the adipose tissue of obese mice. As a proangiogenic factor, PDGF is increased in human serum in response to inflammation and is involved in angiogenesis in many tissues (1, 3). However, it is not clear whether blood PDGF is elevated in an obese condition. To address this issue, the PDGF protein was compared in the serum of lean and ob/ob mice. The PDGF protein was increased in obese mice, as indicated by the ELISA data (Fig. 2A). To determine the source of PDGF protein, PDGF mRNA was determined in the adipose tissue by qRT-PCR. The mRNA was increased in the ob/ob mice as well (Fig. 2B). To determine the cell types for the source of increased PDGF, we examined PDGF mRNA in the adipose tissue after deletion of macrophages in the obese mice. The PDGF expression was reduced by macrophage deletion in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that PDGF is elevated in the blood and that adipose tissue may contribute to the systemic increase in PDGF protein. Macrophages are responsible for the PDGF increase in adipose tissue.

Fig. 2.

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) increased in adipose tissue in ob/ob mice. A: serum PDGF was determined by ELISA. B: PDGF mRNA was determined in epididymal fat pads by qRT-PCR. C: PDGF mRNA in adipose tissue after macrophage deletion. Macrophages were reduced in adipose tissue by single ip injection of clodronate liposome in ob/ob mice (6 wk old). PDGF was examined at day 4 after injection. F4/80 is a marker of macrophage. Each data points represents mean ± SE (n = 3).

Expression of PDGF by macrophages and adipocytes.

The data above suggest that macrophages may be a major producer of PDGF in the adipose tissue of obese mice. To test this question, we compared macrophages and adipocytes for expression of PDGF mRNA. The primary cells and cell lines were used and their activities compared in the basal and hypoxia-treated conditions. In the primary cells, macrophages expressed more PDGF than the adipocytes in the basal condition (Fig. 3A). This pattern of expression was also observed in the cell lines of macrophages (RAW cell) and adipocytes (3T3-L1) (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that PDGF is expressed in adipocytes, but the expression level is significantly lower than that of macrophages. The impact of differentiation on PDGF expression was investigated in 3T3-L1 cells. After differentiation, PDGF expression was significantly reduced in 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that expression of PDGF is in the order of macrophage > preadipocytes > mature adipocytes.

Fig. 3.

PDGF expression in macrophages and adipocytes. A: PDGF mRNA in primary cells. The basal level of PDGF mRNA was determined in primary macrophages and adipocytes of lean mice. B: basal level of PDGF mRNA was determined in macrophage cell lines (RAW cells) and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. C: basal level of PDGF mRNA was determined in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts before and after differentiation into adipocytes. D: induction of PDGF mRNA expression by ambient hypoxia in primary macrophages and RAW macrophages. E: expression of PDGF in adipose tissue of lean mice after macrophage deletion. A single injection of clodronate liposome (150 mg/kg) was used to delete macrophages in lean C57BL/6J mice (8 wk old). Experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results. Each data point represents mean ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05, treated vs. untreated in RAW cells; +P < 0.05, treated vs. untreated in primary macrophages.

Induction of PDGF expression by hypoxia.

Hypoxia in adipose tissue may induce PDGF expression in obese mice, as PDGF-B is a hypoxia response gene (16); this possibility remained to be tested. To test this, PDGF expression was determined in primary macrophages after exposure to ambient hypoxia. As expected, PDGF expression was increased by the hypoxia treatment (Fig. 3D). In the macrophage cell line (RAW), the same effect was observed for hypoxia (Fig. 3D). However, the response of RAW macrophages was stronger than for the primary macrophages. These data further support that macrophages are a the major producer of PDGF in the adipose tissue of obese mice. Macrophage infiltration should contribute to the elevated PDGF expression in adipose tissue. In lean mice, preadipocytes or stromal cells may be the primary source of PDGF, as deletion of macrophages did not lead to reduction in PDGF expression (Fig. 3E).

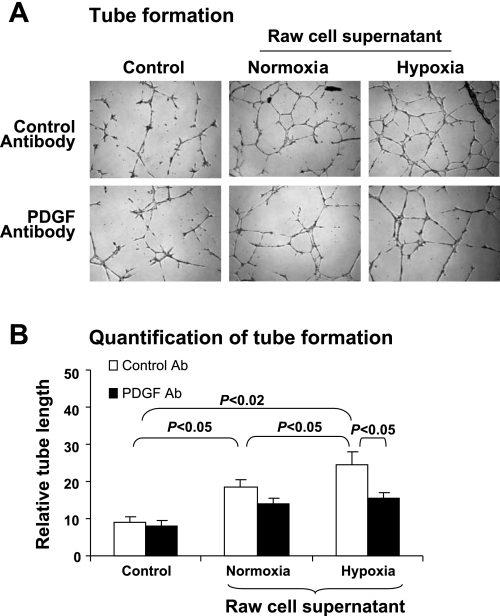

Function of PDGF in regulation of angiogenesis.

Given the role of PDGF in angiogenesis, we proposed that macrophage PDGF may be involved in the stimulation of capillary growth in adipose tissue under hypoxia, in which case the supernatant of hypoxia-treated macrophages should be able to stimulate angiogenesis. To test this possibility, the supernatant of RAW macrophages treated by hypoxia was examined in the tube formation assay. Such an assay was used to study PDGF activity elsewhere (2, 12). The results suggest that the macrophage supernatant induced more tube in the assay, and this activity increased in the supernatant of hypoxia-treated macrophages (Fig. 4, A and B, control antibody). In the presence of PDGF antibody, such an increase in tube formation was inhibited (Fig. 4, A and B, PDGF antibody).

Fig. 4.

Induction of tube formation by PDGF in macrophage supernatant. Tube formation of endothelial cells on Matrigel was used to test proangiogenic activity of PDGF in supernatants of macrophages. Raw cells were treated with hypoxia for 4 h, and its supernatant was collected for induction of tube formation in endothelial cells. PDGF antibody was used to determine activity of PDGF in the supernatant. A: representative images of tube formation of the endothelial cells on Matrigel. B: quantification of tube formation. Experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results. Each data point represents mean ± SE (n = 3 experiments).

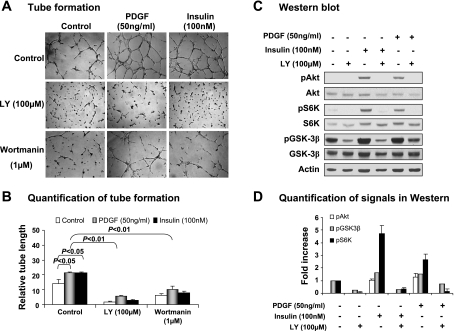

PI3K/Akt pathway in PDGF-stimulated tube formation.

The signaling pathway of PDGF receptor is involved in angiogenesis and is described in several pathological conditions (47). The importance of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in PDGF-induced angiogenesis was demonstrated in vivo in rodent models (13, 18, 25, 58). PDGF is known to activate the PI3K/Akt pathway in pericytes that normally form part of the capillary wall. It remains to be tested whether the same pathway is involved in tube formation by endothelial cells. To investigate the PI3K/Akt pathway in endothelial cells, we examined PI3K inhibitors on tube formation. In the positive control, insulin was used to induce tube formation (Fig. 5, A and B). In the presence of PI3K inhibitor LY-294002 (100 μM) or wortmanin (1 μM), the insulin-induced tube formation was reduced significantly. Recombinant PDGF was used to stimulate tube formation in the mouse endothelial cells. As expected, the tube formation was induced by the recombinant PDGF, and the effect was blocked by the PI3K inhibitors (Fig. 5, A and B). The data suggest that PI3K activity is required for tube formation induced by PDGF and insulin. The basal level of tube formation was also reduced by the PI3K inhibitors (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that PI3K activity is required for tube formation induced by Matrigel, which contains proangiogenic factors.

Fig. 5.

PI3K/Akt pathway in PDGF-induced tube formation. The role of PI3K in tube formation induced by PDGF was examined using PI3K inhibitors. A: representative images of tube formation of the endothelial cells induced by PDGF. B: quantification of tube formation. C: representative Western blots of phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt signaling molecules. D: quantification of Western blot signals. In this figure, all experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results. Each data point represents mean ± SE (n = 3 experiments).

To verify activation of PI3K/Akt by PDGF, we examined the phosphorylation status of Akt and its downstream molecules in a Western blot. Identical to those observed with insulin in the positive control, the activation markers of Akt, S6K, and GSK3-β were all increased by PDGF (Fig. 5, C and D). These changes were consistently blocked by the PI3K inhibitor LY-294002. We also tested the roles of MAPK kinases in PDGF-induced tube formation with chemical inhibitors to ERK (PD-098095 40 μM), JNK (SP-600125 50 μM), and p38 (SB-203580 2 μM). Although these inhibitors could inhibit the basal level of tube formation, they did not decrease the PDGF-induced tube formation significantly (Supplemental Fig. S1, online only). These data suggest that the PI3K/Akt pathway is required for angiogenesis induced by PDGF.

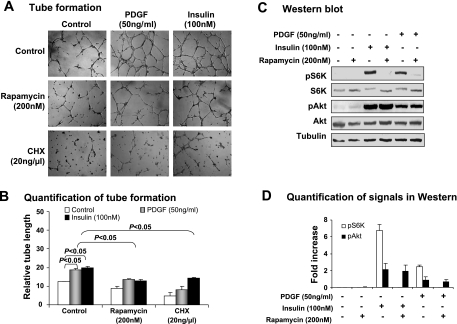

mTOR in PDGF-induced tube formation.

mTOR is a major signaling molecule downstream of Akt. Inhibition of angiogenesis by rapamycin in mice suggests that mTOR may mediate PI3K/Akt signaling in the stimulation of angiogenesis in mice (18). In the current study, inhibition of mTOR led to a reduction in tube formation induced by PDGF as well as by insulin (Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting that mTOR is required for the PDGF signaling pathway. Activation of mTOR by PDGF and its inhibition by rapamycin were examined by the phosphorylation status of S6K in Western blot. As was observed for insulin, the phosphorylation was induced by PDGF and blocked by rapamycin (Fig. 6, C and D). As inhibition of protein synthesis by cycloheximide abolished the tube formation induced by PDGF or insulin (Fig. 6A), protein synthesis is required for the tube formation. This observation suggests that mTOR may act through S6K in the PDGF signaling pathway in endothelial cells, as S6K controls gene translation.

Fig. 6.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in PDGF-induced tube formation. The role of mTOR/S6K in PDGF-induced tube formation was tested with mTOR inhibitor (rapamycin) and protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX). A: representative images of tube formation in the presence of rapamycin and CHX. Insulin was used as a positive control in induction of mTOR activation. Rapamycin (200 nM) and CHX (20 ng/ml) were used to pretreat cells for 30 min, followed by treatment of PDGF (50 ng/ml) or insulin (100 nM) for 10 h. B: quantification of tube formation. C: representative Western blots for mTOR/S6K signaling pathway in endothelial cells. Phosphorylation of S6K was determined in SVEC4-10 cells after treatment with PDGF or insulin. D: quantification of Western blot signals. In this figure, all experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results. Each data point represents mean ± SE (n = 3 experiments).

S6K in PDGF-induced tube formation.

S6K is one of the major signaling molecules activated by mTOR and is involved in regulation of protein synthesis. It remains to be tested whether S6K mediates PDGF signal in endothelial cells for tube formation (24, 38, 57). The S6K dominant-negative (S6K-DN) mutant in stable transfection was generated to test S6K activity in PDGF-induced tube formation. The mutant S6K was expressed in the SVEC4-10 cells, as indicated by detection of HA-tag in Western blot (Fig. 7A). Inhibition of S6K function was confirmed, with decreased phosphorylation of its substrate S6 in the transfected cells (Fig. 7B). In response to PDGF, the stable cell line expressing S6K-DN exhibited much fewer tubes on the Matrigel (Fig. 7, C and D), suggesting that S6K is required by PDGF in the signal transduction.

Fig. 7.

S6K in PDGF-induced tube formation. A: expression of dominant-negative S6K (S6K-DN) in stable cells. B: inhibition of S6K activity by S6K-DN mutant. C: tube formation in stable cells in response to PDGF. D: quantification of tube formation. In this figure, all experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results. Each data point represents mean ± SE (n = 3 experiments).

Stimulation of tube formation by albumin.

The data above suggest that the signal of tube formation is transduced through PI3K/Akt/mTOR/S6K under the PDGF receptor. It is not clear whether activation of S6K in the absence of activation of upstream signaling molecules including PI3K and Akt is sufficient to induce tube formation. To test this possibility, S6K was activated with albumin (Fig. 8A). The activation led to an increase in tube formation, and the increase was blocked by rapamycin (Fig. 8, B and C), which suppresses S6K by targeting mTOR. The data suggest that activation of S6K by albumin is able to increase tube formation. Toxicity of rapamycin was examined in an MTT assay. Treatment of the cells with rapamycin for 24 h had no significant effect on cell viability in presence or absence of PDGF (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

S6K in tube formation induced by albumin. A: Induction of phosphorylation of S6K by albumin. Phosphorylation of S6K was examined in whole cell lysate in Western blot. B: BSA-stimulated tube formation and inhibition by rapamycin (200 nM). C: quantification of tube formation. D: cell viability after rapamycin treatment. Cell viability was determined with MTT assay at 24 h after cell exposure to rapamycin. In this figure, all experiments were repeated 3 times with consistent results. Each data points represents mean ± SE (n = 3 experiments).

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that vascular density is decreased in adipose tissue in ob/ob mice. Angiogenesis is required for the development and growth of adipose tissue (7, 41). During development of obesity, angiogenic activity will be increased to compensate for expansion of adipocyte tissue. This compensation ensures quick growth in adipose tissue at the early stage of weight gain. Once the weight gain reaches a level such as BMI >25–30 kg/m2, a failure in angiogenic compensation may occur and thus reduce the growth rate of fat tissues. A reduction in adipose tissue blood flow may be a result of such angiogenic failure (53). To explain adipose tissue hypoxia in the obese condition (56), we proposed that angiogenic failure may occur in adipose tissue of obese mice. In the current study, this possibility is supported by the reduction of vascular density in the adipose tissue. The CD31 data from immunohistostaining, Western blot, and qRT-PCR consistently support the lack of endothelial cells in the adipose tissue of ob/ob mice (Fig. 1). A lack of VEGF induction by hypoxia was observed in the adipose tissue in the same condition (56). The VEGF non-response may contribute to the reduced endothelial cells, as VEGF is a primary growth factor for endothelia cells.

Macrophages may serve as a stimulator for angiogenesis in adipose tissue in obesity. Adipose tissue contains several types of cells, such as preadipocytes (or stromal cells), adipocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells. PDGF is expressed in all of these types of cells; however, the expression levels are different. The current study suggests that preadipocytes express more PDGF than mature adipocytes. In obesity, preadipocyte number is reduced, as most of them are differentiated into mature adipocytes. This change may lead to a decrease in local PDGF level, since mature adipocytes produce less PDGF than the preadipocytes (Fig. 3C). To meet the demand for PDGF, macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue is increased to compensate for the loss of preadipocytes for PDGF production (Fig. 2B). Our data support the idea that infiltration and activation of macrophages may contribute to the increased PDGF expression in the adipose tissue of obese mice. This conclusion is supported by the observations that deletion of macrophages led to a significant reduction in PDGF expression in adipose tissue of ob/ob mice. The reduction was observed in obese mice but not in lean mice, which have abundant preadipocytes (Figs. 2C and 3E). Macrophages are second next to platelets in expression of PDGF (32, 40, 43). We believe that, in addition to its roles in chronic inflammation (52, 55), macrophages may serve as an angiogenic stimulator in adipose tissue by expression of PDGF. To our knowledge, this may be the first study to support elevation and function of PDGF in adipose tissue of obesity. Hypoxia in adipose tissue is likely to induce PDGF expression in macrophages (Fig. 3D). In the current study, PDGF expression was determined mainly at the mRNA level. It remains to be tested whether PDGF protein is induced by hypoxia in macrophages.

We did not find literature about PDGF expression in adipose tissue in obesity. Closely related literature includes PDGF regulation of GLUT4 translocation, proliferation, or differentiation of adipocytes in cell culture (19, 31, 36). In vitro, PDGF or its receptor has been shown to promote GLUT4 translocation in adipocytes (31, 36). PDGF has been reported to inhibit adipocyte differentiation (19). In other organs, local PDGF has been suggested to play a role in pathogenesis of proliferative retinopathy and diabetic nephropathy (14, 26, 39). An increase in PDGF has been found in the retinal membranes and vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (14, 39). A higher PDGF level has also been reported in individuals with additional rubeosis iridis or ischemic nondiabetic retinopathy (14). In the renal biopsy of patients with diabetic nephropathy, expression of PDGF-A and PDGF-B has been reported to be increased in mRNA and protein (26). In mice with type 1 diabetes, the PDGF elevation has been associated with macrophage infiltration into kidney with diabetic nephropathy (9). These observations suggest a role of PDGF in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications.

The current study suggests that the activity of PDGF in angiogenesis is dependent on VEGF activity. Angiogenesis requires endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation. The two events are equally important in the process of formation of capillary. Tube formation requires the presence of endothelial cells; in the absence of endothelial cells, tube formation will not occur. Endothelial cell proliferation is dependent on proangiogenic factor VEGF, which stimulates cell proliferation through VEGF receptor 2 in the endothelial cells. The lack of endothelia cells was observed in adipose tissue of ob/ob mice in this study (Fig. 1). The reduction in endothelial cells is supported by quantification of CD31 (endothelial cell marker) in protein and mRNA. This reduction is consistent with our previous observation that VEGF expression was not increased in adipose tissue by obesity in ob/ob mice (56). Lack of leptin in the ob/ob mice may be related to the unresponsiveness of VEGF to obesity or adipose tissue hypoxia. In the wild-type mice, VEGF was increased by diet-induced obesity in the adipose tissue (56). Without sufficient endothelial cells, PDGF will not be able to increase angiogenesis in the adipose tissue by itself.

In addition to stimulation of tube formation, PDGF was reported to play a role in the recruitment of pericytes or the proliferation of vessel smooth muscle cells in angiogenesis. Recruitment of pericytes is required for maintenance of microvascular stability and function (21, 22, 29). This function of PDGF is established in a PDGF knockout study (29). Pericytes are able to transdifferentiate into fibroblasts (stromal cells/preadipocytes) and vessel smooth muscle cells (37). With these activities, it is possible that PDGF is involved in recruitment of preadipocytes into adipose tissue in obesity.

In the current study, we observed that insulin stimulated tube formation, suggesting a role for insulin in the stimulation of angiogenesis. This activity indicates that hyperinsulinemia may serve to stimulate angiogenesis in adipose tissue in the obese condition. Hyperinsulinemia is a prognosis factor for the incidence of microvascular abnormalities in diabetes patients for retinopathy and nephropathy (4). In the present study, insulin exhibited a similar activity to PDGF in the induction of tube formation (Figs. 5 and 6). This observation suggests that hyperinsulinemia may be involved in neovascularation in adipose tissue during the development of obesity.

S6K is required for tube formation induced by PDGF and insulin. S6K is activated by an array of mitogenic or nutrient stimuli, such as insulin, serum, phorbol ester, and PDGF (38, 48, 54). Knockout studies suggest that S6K is an important regulator of cell size and body growth in mice and Drosophila (35, 42). S6K1−/− mice are protected against age- and high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance due to increased energy expenditure (48). In tube formation, S6K may act through induction of FGF-2 expression in endothelial cells (57). In the present study, our data suggest that S6K mediates signals of PDGF and insulin in the induction of tube formation. This is supported by data that inhibition of S6K by dominant-negative mutant or chemical inhibitors (LY, wortmanin, and rapamycin) lead to inhibition of PDGF and insulin activity (Figs. 5–7). These data consistently support the notion that S6K is a critical kinase for endothelial differentiation and tube formation.

In summary, reduction in vascular density is likely a result of a lack of an endothelium growth factor (such as VEGF) in adipose tissue in ob/ob mice. This may contribute to the development of adipose tissue hypoxia and macrophage infiltration. PDGF expression is increased in macrophages in response to the hypoxia. Although PDGF is able to stimulate tube formation, it may not stimulate angiogenesis in the absence of sufficient endothelial cells or VEGF activity. The signaling pathway PI3K/Akt/mTOR/S6K is used by PDGF in the induction of tube formation. With insufficient endothelial cells in the adipose tissue of ob/ob mice, macrophages may fail to stimulate angiogenesis. These possibilities may support a new function for macrophages in adipose tissue. Hyperinsulinemia may also be involved in angiogenesis in adipose tissue in obesity by stimulation of tube formation in endothelial cells.

GRANTS

This study is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) funds (DK-68036) and ADA research award (7-07-RA-189) to J. Ye and the Key Project from the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai municipality (04DZ19501, 01ZD002, and National 973 Program) to W. Jia. The qRT-PCR study was conducted in the genomic core that is supported by the CNRU Grant (1P30 DK-072476) sponsored by NIDDK.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Burk in the Imaging Core Facility and Dr. Viktor Drel for their excellent technical support in the capture of images for tube formation and processing of tissue slides for immunohistostaining. We thank Hanjie Zhang for technical support in the preparation of clodronate liposome.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Au PY, Martin N, Chau H, Moemeni B, Chia M, Liu FF, Minden M, Yeh WC. The oncogene PDGF-B provides a key switch from cell death to survival induced by TNF. Oncogene 24: 3196–3205, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battegay EJ, Rupp J, Iruela-Arispe L, Sage EH, Pech M. PDGF-BB modulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via PDGF beta-receptors. J Cell Biol 125: 917–928, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betsholtz C Role of platelet-derived growth factors in mouse development. Int J Dev Biol 39: 817–825, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonadonna RC, Cucinotta D, Fedele D, Riccardi G, Tiengo A. The metabolic syndrome is a risk indicator of microvascular and macrovascular complications in diabetes: results from Metascreen, a multicenter diabetes clinic-based survey. Diabetes Care 29: 2701–2707, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouloumie A, Lolmede K, Sengenes C, Galitzky J, Lafontan M. Angiogenesis in adipose tissue. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 63: 91–95, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brakenhielm E, Cao R, Gao B, Angelin B, Cannon B, Parini P, Cao Y. Angiogenesis Inhibitor, TNP-470, Prevents Diet-Induced and Genetic Obesity in Mice. Circ Res 94: 1579–1588, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Wahlestedt C, Thyberg J, Cao Y. Leptin induces vascular permeability and synergistically stimulates angiogenesis with FGF-2 and VEGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6390–6395, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellot JJ, Karnovsky MJ, Spiegelman BM. Differentiation-dependent stimulation of neovascularization and endothelial cell chemotaxis by 3T3 adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 5597–5601, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC, Tesch GH. Macrophages in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy: potential role in renal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 2987–2996, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res 46: 2347–2355, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crandall DL, Hausman GJ, Kral JG. A review of the microcirculation of adipose tissue: anatomic, metabolic, and angiogenic perspectives. Microcirculation 4: 211–232, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Marchis F, Ribatti D, Giampietri C, Lentini A, Faraone D, Scoccianti M, Capogrossi MC, Facchiano A. Platelet-derived growth factor inhibits basic fibroblast growth factor angiogenic properties in vitro and in vivo through its alpha receptor. Blood 99: 2045–2053, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dell S, Peters S, Muther P, Kociok N, Joussen AM. The role of PDGF receptor inhibitors and PI3-kinase signaling in the pathogenesis of corneal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 1928–1937, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freyberger H, Brocker M, Yakut H, Hammer J, Effert R, Schifferdecker E, Schatz H, Derwahl M. Increased levels of platelet-derived growth factor in vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 108: 106–109, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Z, He Q, Peng B, Chiao PJ, Ye J. Regulation of nuclear translocation of hdac3 by I(kappa)B(alpha) is required for tumor necrosis factor inhibition of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (gamma) function. J Biol Chem 281: 4540–4547, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleadle JM, Ebert BL, Firth JD, Ratcliffe PJ. Regulation of angiogenic growth factor expression by hypoxia, transition metals, and chelating agents. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 268: C1362–C1368, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith HS, Griffith AL, Kupferman A, Catsimpoolas N. Lipid angiogenic factor from omentum. JAMA 252: 2034–2036, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guba M, von Breitenbuch P, Steinbauer M, Koehl G, Flegel S, Hornung M, Bruns CJ, Zuelke C, Farkas S, Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Geissler EK. Rapamycin inhibits primary and metastatic tumor growth by antiangiogenesis: involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor. Nat Med 8: 128–135, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauner H, Rohrig K, Petruschke T. Effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) on human adipocyte development and function. Eur J Clin Invest 25: 90–96, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev 79: 1283–1316, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hellstrom M, Gerhardt H, Kalen M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. J Cell Biol 153: 543–553, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellstrom M, Kalen M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development 126: 3047–3055, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kampf C, Bodin B, Kallskog O, Carlsson C, Jansson L. Marked increase in white adipose tissue blood perfusion in the type 2 diabetic GK rat. Diabetes 54: 2620–2627, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanda S, Hodgkin MN, Woodfield RJ, Wakelam MJ, Thomas G, Claesson-Welsh L. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-independent p70 S6 kinase activation by fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 is important for proliferation but not differentiation of endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 272: 23347–23353, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kratchmarova I, Blagoev B, Haack-Sorensen M, Kassem M, Mann M. Mechanism of divergent growth factor effects in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Science 308: 1472–1477, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langham RG, Kelly DJ, Maguire J, Dowling JP, Gilbert RE, Thomson NM. Over-expression of platelet-derived growth factor in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1392–1396, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau DC, Schillabeer G, Li ZH, Wong KL, Varzaneh FE, Tough SC. Paracrine interactions in adipose tissue development and growth. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 20, Suppl 3: S16–S25, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lijnen HR Angiogenesis and obesity. Cardiovasc Res 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C. Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science 277: 242–245, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lolmede K, Durand de Saint Front V, Galitzky J, Lafontan M, Bouloumie A. Effects of hypoxia on the expression of proangiogenic factors in differentiated 3T3-F442A adipocytes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27: 1187–1195, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marx M, Perlmutter RA, Madri JA. Modulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor expression in microvascular endothelial cells during in vitro angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 93: 131–139, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mornex JF, Martinet Y, Yamauchi K, Bitterman PB, Grotendorst GR, Chytil-Weir A, Martin GR, Crystal RG. Spontaneous expression of the c-sis gene and release of a platelet-derived growth factorlike molecule by human alveolar macrophages. J Clin Invest 78: 61–66, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neels JG, Thinnes T, Loskutoff DJ. Angiogenesis in an in vivo model of adipose tissue development. FASEB J 18: 983–985, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Hosoya Y, Yamashita H, Fujita H, Ohsugi M, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Nagai R, Sugiura S. Adipogenesis in obesity requires close interplay between differentiating adipocytes, stromal cells, and blood vessels. Diabetes 56: 1517–1526, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pende M, Um SH, Mieulet V, Sticker M, Goss VL, Mestan J, Mueller M, Fumagalli S, Kozma SC, Thomas G. S6K1(−/−)/S6K2(−/−) mice exhibit perinatal lethality and rapamycin-sensitive 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine mRNA translation and reveal a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent S6 kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3112–3124, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quon MJ, Chen H, Lin CH, Zhou L, Ing BL, Zarnowski MJ, Klinghoffer R, Kazlauskas A, Cushman SW, Taylor SI. Effects of overexpressing wild-type and mutant PDGF receptors on translocation of GLUT4 in transfected rat adipose cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 226: 587–594, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajkumar VS, Howell K, Csiszar K, Denton CP, Black CM, Abraham DJ. Shared expression of phenotypic markers in systemic sclerosis indicates a convergence of pericytes and fibroblasts to a myofibroblast lineage in fibrosis. Arthritis Res Ther 7: R1113–R1123, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebholz H, Panasyuk G, Fenton T, Nemazanyy I, Valovka T, Flajolet M, Ronnstrand L, Stephens L, West A, Gout IT. Receptor association and tyrosine phosphorylation of S6 kinases. FEBS J 273: 2023–2036, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robbins SG, Mixon RN, Wilson DJ, Hart CE, Robertson JE, Westra I, Planck SR, Rosenbaum JT. Platelet-derived growth factor ligands and receptors immunolocalized in proliferative retinal diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 35: 3649–3663, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross R, Raines EW, Bowen-Pope DF. The biology of platelet-derived growth factor. Cell 46: 155–169, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rupnick MA, Panigrahy D, Zhang CY, Dallabrida SM, Lowell BB, Langer R, Folkman MJ. Adipose tissue mass can be regulated through the vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 10730–10735, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shima H, Pende M, Chen Y, Fumagalli S, Thomas G, Kozma SC. Disruption of the p70(s6k)/p85(s6k) gene reveals a small mouse phenotype and a new functional S6 kinase. EMBO J 17: 6649–6659, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimokado K, Raines EW, Madtes DK, Barrett TB, Benditt EP, Ross R. A significant part of macrophage-derived growth factor consists of at least two forms of PDGF. Cell 43: 277–286, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverman KJ, Lund DP, Zetter BR, Lainey LL, Shahood JA, Freiman DG, Folkman J, Barger AC. Angiogenic activity of adipose tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 153: 347–352, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strissel KJ, Stancheva Z, Miyoshi H, Perfield JW, 2nd DeFuria J, Jick Z, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Adipocyte death, adipose tissue remodeling, and obesity complications. Diabetes 56: 2910–2918, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sunderkotter C, Goebeler M, Schulze-Osthoff K, Bhardwaj R, Sorg C. Macrophage-derived angiogenesis factors. Pharmacol Ther 51: 195–216, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tallquist M, Kazlauskas A. PDGF signaling in cells and mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15: 205–213, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Um SH, D'Alessio D, Thomas G. Nutrient overload, insulin resistance, and ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, S6K1. Cell Metab 3: 393–402, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods 174: 83–93, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varzaneh FE, Shillabeer G, Wong KL, Lau DC. Extracellular matrix components secreted by microvascular endothelial cells stimulate preadipocyte differentiation in vitro. Metabolism 43: 906–912, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vinals F, Chambard JC, Pouyssegur J. p70 S6 kinase-mediated protein synthesis is a critical step for vascular endothelial cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 274: 26776–26782, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112: 1796–1808, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.West DB, Prinz WA, Francendese AA, Greenwood MR. Adipocyte blood flow is decreased in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 253: R228–R233, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woo SY, Kim DH, Jun CB, Kim YM, Vander Haar E, Lee SI, Hegg JW, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ, Kim DH. PRR5, a novel component of mTOR complex 2, regulates PDGFRbeta expression and signaling. J Biol Chem 282: 25604–25612, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112: 1821–1830, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye J, Gao Z, Yin J, He H. Hypoxia is a potential risk factor for chronic inflammation and adiponectin reduction in adipose tissue of ob/ob and dietary obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1118–E1128, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang B, Cao H, Rao GN. 15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid induces angiogenesis via activation of PI3K-Akt-mTOR-S6K1 signaling. Cancer Res 65: 7283–7291, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang H, Bajraszewski N, Wu E, Wang H, Moseman AP, Dabora SL, Griffin JD, Kwiatkowski DJ. PDGFRs are critical for PI3K/Akt activation and negatively regulated by mTOR. J Clin Invest 117: 730–738, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.