Abstract

Socially inhibited individuals show increased vulnerability to viral infections, and this has been linked to increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). To determine whether structural alterations in SNS innervation of lymphoid tissue might contribute to these effects, we assayed the density of catecholaminergic nerve fibers in 13 lymph nodes from 7 healthy adult rhesus macaques that showed stable individual differences in propensity to socially affiliate (Sociability). Tissues from Low Sociable animals showed a 2.8-fold greater density of catecholaminergic innervation relative to tissues from High Sociable animals, and this was associated with a 2.3-fold greater expression of nerve growth factor (NGF) mRNA, suggesting a molecular mechanism for observed differences. Low Sociable animals also showed alterations in lymph node expression of the immunoregulatory cytokine genes IFNG and IL4, and lower secondary IgG responses to tetanus vaccination. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that structural differences in lymphoid tissue innervation might potentially contribute to relationships between social temperament and immunobiology.

Keywords: temperament, sociability, sympathetic, autonomic nervous system, health vulnerability

INTRODUCTION

One of the most prominent dimensions of stable individual difference in behavior involves the propensity to affiliate with others (Gosling, 2001; Goldberg, 1993; Kagan, 1994; Rothbart, et al., 1994). Some individuals are drawn to novel social experiences and readily interact with others (High Sociable), whereas other individuals tend toward social withdrawal, particularly in the presence of strangers (Low Sociable). Individual differences in Sociability are conserved across vertebrate evolution (Gosling, 2001; Capitanio, et al., 1999; Capitanio and Widaman, 2005) and over individual development (Kagan, 1994), with neurobiological antecedents observable in utero (Kagan, 1994) and behavioral manifestations in early infancy (Kagan and Snidman, 1991; Plomin and Rowe, 1979). A diverse array of psychological processes have attempted to explain individual differences in Sociability, including social inhibition (Kagan, 1994), introversion (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1985), behavioral inhibition (Rothbart, et al., 1994; Gray, 1991; Carver and White, 1994), social anxiety (Liebowitz, et al., 1985), rejection sensitivity (Kramer, 1997), reward dependence (Cloninger, 1986), and emotional reactivity (Eisenberg, et al., 1995). A common theme in these theories is the hypothesis that individual differences in social behavior stem from underlying variations in central nervous system (CNS) affective responses to threat or uncertainty (Schwartz, et al., 2003; Kramer, 1997; Westergaard, et al., 1999). Consistent with that perspective, low Sociability has also been linked to increased activity of stress-responsive peripheral systems, including activity of the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Block, 1957; Buck, et al., 1974; Jones, 1935, 1950, 1960; Kagan, 1994; Kagan, et al., 1988; Stansbury and Gunnar, 1994; Fox, et al., 2005).

Clinicians have long observed that Low-Sociable individuals seem to fall at increased risk for a variety of immune-mediated diseases, including viral infections, autoimmune diseases, and allergic reactions (Kagan, 1994). Empirical studies have supported this hypothesis in finding heightened vulnerability to viral upper respiratory infections (Broadbent, et al., 1984; Cohen, et al., 1997; Totman, et al., 1980; Cohen, et al., 2003), atopic allergy (Bell, et al., 1990; Gauci, et al., 1993; Kagan and Snidman, 1991), delayed type hypersensitivity reactions (Cole, et al., 1999), and HIV-1 disease progression (Cole, et al., 1997; Cole, et al., 2003) in Low-Sociable people, and heightened Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) disease pathogenesis in Low-Sociable rhesus monkeys (Capitanio, et al., 1999). In the context of HIV/SIV infection, Sociability-related differences in pathophysiology have been linked to variations in autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity (Cole, et al., 2003). A central question of current research in this area involves understanding which specific aspects of peripheral neurobiology link individual differences in Sociability to variations in the biology of disease.

Secondary lymphoid organs represent a key physiologic context for the biology of immune-mediated disease by serving as the primary environment in which antigen presenting cells from the innate immune response interact with naïve antigen-specific lymphocytes to generate adaptive immune responses (von Andrian and Mempel, 2003). In the context of lymphotropic infections such as HIV-1 and SIV, these tissues also constitute primary sites of viral replication and immunopathogenesis (Fox, et al., 1991; Fauci, 1988). One pathway by which Sociability-related differences in ANS activity might impact immune system biology involves the innervation of lymphoid tissues by nerve fibers from the sympathetic nervous system (Felten, et al., 1987; Bellinger, et al., 2001; Nance and Sanders, 2007). Sympathetic nerve fibers innervate all primary and secondary lymphoid organs (Felten, et al., 1984; Felten, et al., 1985; Nance and Sanders, 2007), where they release the catecholamine neurotransmitter norepinephrine from varicosities situated periodically over the length of the fiber (Bellinger, et al., 2001). Catecholaminergic innervation of lymphoid tissue can regulate a wide variety of immunologic processes (Madden, et al., 1994; Carlson, et al., 1997; Kohm and Sanders, 1999; Sanders and Straub, 2002; Nance and Sanders, 2007) and are implicated in the pathophysiology of lymphotropic viral infections (Sloan, et al., 2006; Sloan, et al., 2007b).

Most analyses of lymphoid innervation have implicitly presumed that functional alterations in neural activity constitute the primary mechanism by which behavioral factors regulate lymphoid tissue biology (Shimizu, et al., 1994). However, recent studies have identified a surprising degree of plasticity in the structure of lymphoid tissue innervation (Madden, et al., 1997; Kelley, et al., 2003; Sloan, et al., 2006; Sloan, et al., 2007b; Sloan, et al., 2007c). In the present research, we sought to determine whether individual differences in Sociability might be linked to alterations in the structure of lymphoid tissue sympathetic innervation in ways that might ultimately contribute to differences in immune system biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Analyses were carried out on 13 axillary lymph nodes biopsied from 7 adult male rhesus macaques. Animals ranged in age from 5.3–9.4 years (mean 7.2 years), and all served as non-infected control animals for a larger study of SIV pathogenesis in 36 animals (Capitanio, et al., 2008). SIV-infected animals were not included in this study of Sociability-related differences in lymphoid innervation to avoid the potentially confounding effects of lymphotropic viral infection on innervation density (Sloan, et al., 2006; Sloan, et al., 2007c). Behavioral characterization was carried out as previously described (Maninger, et al., 2003; Capitanio, et al., 2008), with monkeys observed in their outdoor, half-acre, natal cages for 20 × 5-min periods by human observers for two-week periods. Observers demonstrated ≥ 85% agreement on behavioral categories. Following behavioral coding, monkeys were rated by the observers using an inventory of 50 social-behavioral traits (http://psychology.ucdavis.edu/capitanio/rhesus_personality.pdf). Ratings that demonstrated adequate inter-rater agreement and reliability were factor-analyzed, and a four-factor solution was found (Maninger, et al., 2003) and subsequently confirmed (Capitanio and Widaman, 2005). The Sociability factor (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92) comprised the traits ‘affiliative and companionable’ (defined as ‘seeks out social contact with other animals’), ‘warm and affectionate’ (defined as ‘seeks or elicits bodily closeness, touching or grooming’) and reverse-scored ‘solitary’ (defined as ‘prefers to spend alone or avoids contact with other animals’). Animals selected for the SIV study had Sociability z-scores ranging from +0.52 to +2.02 (HS: High Sociability) and from −0.53 to −2.02 (LS: Low Sociability). Following Sociability assessment, the animals described here were selected to be non-infected controls for the larger study (Capitanio, et al., 2008), and moved to individual indoor cages. Animals were inoculated with saline 22 months later, and axillary lymph nodes were biopsied after a further 9.5 months prior as previously described (Capitanio, et al., 2008; Sloan, et al., 2006). All procedures were carried out under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care and University Institutional Review Boards at the University of California, Davis and Los Angeles campuses.

Lymph node innervation

Six lymph nodes from 3 HS macaques and 7 lymph nodes from 4 LS macaques were randomly selected for histological analysis. The distribution of catecholaminergic varicosities was mapped in 16 μm cryostat sections using glyoxylic acid chemofluorescence as previously described (de la Torre and Surgeon, 1976; Sloan, et al., 2006). To estimate the density of functional innervation, we used the stereological approach described by Mouton (Mouton, 2002) to quantify the number of catecholaminergic varicosities (sites of norepinephrine release) (Sloan, et al., 2006). Briefly, each lymph node section was digitally imaged over its entire surface at 200x magnification using an Axioskop 2 microscope and color camera (Zeiss, Thornwood NY). Individual images were assembled to compose a single digital file of the entire organ section, and a grid of 250 μm2 tissue units was superimposed. Within each tissue unit, the number of catecholaminergic varicosities was counted. Innervation density was estimated at the level of the whole lymph node, and within functionally distinct anatomical regions - paracortex, cortex, and medulla – that were identified by a veterinary pathologist (author RPT) blinded to localization of catecholaminergic fibers. All assays were carried out blind to information on Sociability classification.

Expression of neurotrophic factors and cytokines

Real-time RT-PCR was used to quantify NGF, IFNG, and IL4 mRNA in 3 mg of tissue from each of the lymph nodes analyzed. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy (Qiagen, Valencia CA), and cDNA was synthesized by iScript reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Biorad, Hercules CA). NGF was assessed by real-time PCR utilizing iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad) with 45 PCR amplification cycles of 15 sec of strand-separation at 95° C and 60 sec of annealing and extension at 60° C. Triplicate determinations on each individual lymph node sample were quantified by threshold cycle analysis of SYBR Green fluorescence intensity using iCycler software (BioRad), and normalization to parallel-amplified GAPDH mRNA (Collado-Hidalgo, et al., 2006). Primer sequences were verified to amplify macaque RNA, and were (NGF) F 5′-GTTTTACCAAGGGAGCAGCTTTC-3′ R 5′-TAGTCCAGTGGGCTTGGGGGA-3′, and (GAPDH) F 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ R 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTC-3′. Parallel real-time RT-PCR analyses of macaque IFNG, IL4, and ACTB mRNA were carried out using TaqMan gene expression assays (Rh02621721_m1, Rh02621716_m1, and Hs99999903_m1, respectively; Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) and Quantitect Probe RT-PCR enzymes (Qiagen, Valencia CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Secondary IgG response to vaccination

Following collection of a 3 ml baseline blood plasma sample, each animal received a 0.5-ml tetanus toxoid booster immunization (Colorado Veterinary Products/Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO) intramuscularly. Subsequent 3 ml blood samples were drawn at 2 weeks and 9 months post-immunization. Plasma samples were stored at −80°C and assayed for tetanus-specific IgG using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described (Maninger, et al., 2003; Capitanio, et al., 1998). Lymph nodes were biopsied at least 10 months after vaccination to ensure that any acute reactive tissue structure had abated.

Statistical analyses

To determine whether lymph node innervation density differed as a function of Sociability, nested hierarchical linear model analyses were carried out using SAS v9.1 PROC MIXED (SAS Institute, Cary NC) to analyze the density of catecholaminergic varicosities in tissue units of lymph nodes biopsied from HS and LS animals. To ensure independence of residuals, analyses controlled for differences in innervation density across individual lymph nodes (treated as a random factor nested within individual macaques), and across individual macaques (treated as a random factor nested within the fixed experimental factor of HS vs. LS) (Miller, 1986). Parallel linear model analyses treated Sociability z-scores as a continuous measure of individual differences. RT-PCR data were analyzed in parallel using a hierarchical linear model analysis that controlled for correlation among the triplicate determinations of mRNA concentration in each lymph node specimen.

To assess the potential contribution of differential NGF expression to differential innervation density, statistical mediation analyses were conducted in the context of hiearchical linear models (Hoyle and Kenny, 1999; Baron and Kenny, 1986). A “total effects” analysis first quantified the entire relationship between Sociability and lymph node innervation density (i.e., the effect stemming from all sources: NGF + other influences). A subsequent “mediated model” controlled for any variation in innervation density that could be attributed specifically to NGF, and assessed the residual effect of Sociability (i.e., that attributable to other mediators). Mediation was quantified as the percent of total Sociability-related variance in innervation that was attributable specifically to differences in NGF expression, and Sobel’s test (Hoyle and Kenny, 1999) assessed the statistical significance of the mediated pathway. To determine whether changes in NGF expression might potentially account for all systematic relationships between Sociability and innervation density, residual non-NGF effects of Sociability were tested for statistical significance (with non-significance of residual effects indicating that NGF variation is sufficient to account for all systematic relationship between Sociability and innervation density) (Hoyle and Kenny, 1999; Baron and Kenny, 1986). Parallel mediation analyses were carried out to examine the role of differential innervation in relationships between Sociability and vaccine-induced IgG responses.

RESULTS

Characterization of Sociability

Rhesus macaques were classified as High Sociable (HS: falling in the upper 1/3 of the Sociability distribution) or Low Sociable (LS: falling in the lower 1/3 of the Sociability distribution) based on trained observer ratings of affiliative/companionable behavior, warm/affectionate behavior, and (reverse-scored) solitary behavior in their field cages. HS and LS animals differed substantially in rated levels of ‘affiliation’ (HS: range 4.5 – 6.0 vs. LS: 3.0 – 3.5), ‘warm’ (HS: 4.5 – 5.5 vs. LS: 1.0 – 3.0) and ‘solitary’ (HS: 1.5 – 3.0 vs. LS: 3.5 – 5.5) (Table 1). Analysis of specific behaviors confirmed the trait rating-based distinction between HS and LS animals, with HS animals showing significantly greater frequencies of initiating and receiving approaches to within arm’s reach (HS: 98.3 ± 4.9 (mean ± SEM) vs. LS: 67.5 ± 6.8; p =.02), and marginally greater frequencies of physical contact (HS: 204.3 ± 10.1 vs. LS: 131.0 ± 23.6; p =.053) and grooming (HS: 125.7 ± 7.88 vs. LS: 90.5 ± 11.20; p =.063).

Table 1.

Observer trait ratings of High vs. Low Sociable rhesus macaques. Mean score ± standard error.

| Trait | High Sociable | Low Sociable |

|---|---|---|

| Affilitive, companionable | 5.00 ±.50 | 3.25 ±.14 |

| Warm, affectionate | 5.00 ±.29 | 2.37 ±.47 |

| Solitary | 2.33 ±.44 | 4.50 ±.41 |

Lymph node sympathetic innervation

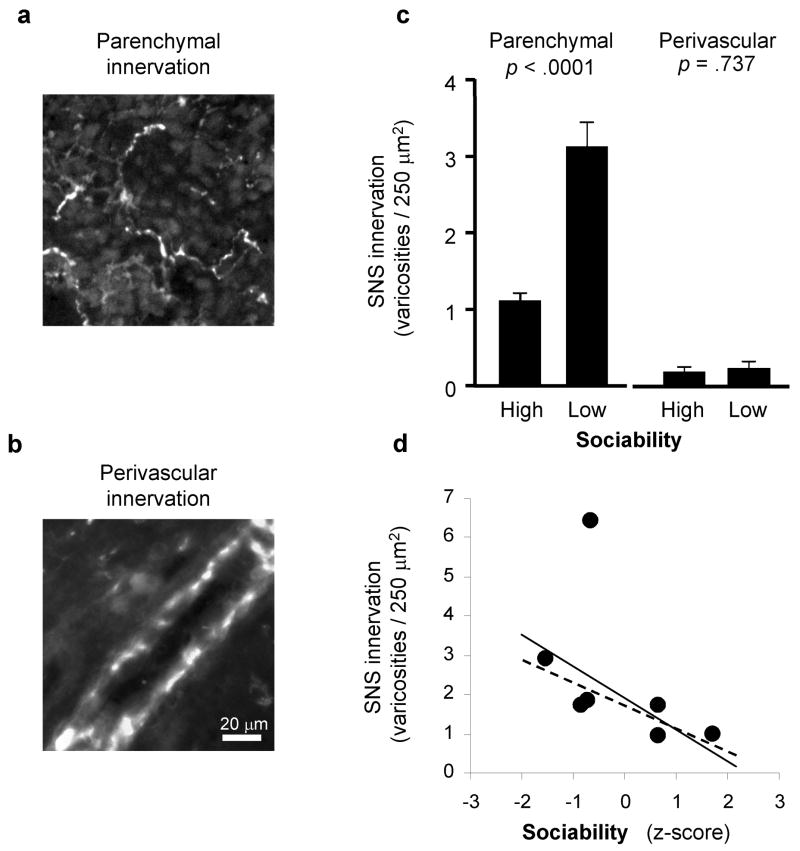

To determine whether lymph node innervation patterns differed in HS vs. LS animals, we used glyoxylic acid chemofluorescence to map the distribution of parenchymal and perivascular catecholaminergic neural fibers in randomly selected 16 μm sections from 13 axillary lymph nodes (Figure 1a, b). LS animals showed significantly greater density of lymph node sympathetic innervation than did HS animals (Figure 1c). Across 4,574 individual 250 μm2 lymph node tissue units analyzed in a hierarchical linear model (tissue units nested within lymph node, lymph node nested within animal, and animal nested within LS vs HS group), the absolute density of parenchymal catecholaminergic varicosities averaged 1.08 per unit (± 0.11) for HS animals vs. 3.05 (± 0.32) for LS animals (p < 0.0001). Individual differences across animals accounted for 42.5% of the total systematic variance in innervation density across lymph nodes (p <.0001), with localized effects specific to each lymph node (i.e., nested within individual) accounting for 57.5% (p <.0001). Of the 42.5% of systematic variance attributable to total individual differences, variations in Sociability accounted for 38.6% (i.e., 16.8% of total variability; p <.0001), with 61.4% attributable to other individual-specific factors (i.e., 26.7% of total variability; p <.0001). Expressed in terms of effect size correlations, replicate observations from the same animal showed a correlation of r = +.132, localized effects specific to each individual lymph node contributed a correlation of r = +.194, and effects of Sociability contributed r = +.105 (all correlations adjusted for confounding with other effects). Similar results emerged in analyses treating Sociability z-scores as a continuous measure of individual differences, with each 1-SD increase in Sociability associated with 0.79 (± 0.12) fewer parenchymal catecholaminergic varicosities per 250 μm2 tissue unit (p <.0001; Figure 1d). Sociability-related differences occurred specifically within the parenchyma of the lymph node and did not affect the density of perivascular catecholamineric varicosities (absolute densities averaged 0.18 ± 0.06 for HS animals vs. 0.23 ± 0.08 for LS animals, difference p =.641) (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Sociability and lymph node innervation.

Catecholaminergic neural fibers were mapped using glyoxylic acid chemofluorescence to define structural varicosities containing the sympathetic neurotransmitter norepinephrine within the lymph node parenchyma (a) or surrounding blood vessels (b). (c) Parenchymal and perivascular innervation density was compared across lymph nodes biopsied from adult male rhesus macaques characterized as High Sociable and Low Sociable. (d) Relationship between mean parenchymal innervation density for each animal and Sociability levels expressed as a continuous dimension of individual differences (z-score). The solid regression line summarizes the linear relationship between innervation density and Sociability for all animals analyzed (Spearman r = −.642, p =.119) and the dashed regression line shows the same relationship after exclusion of the high-range outlier (r = −.846, p =.034).

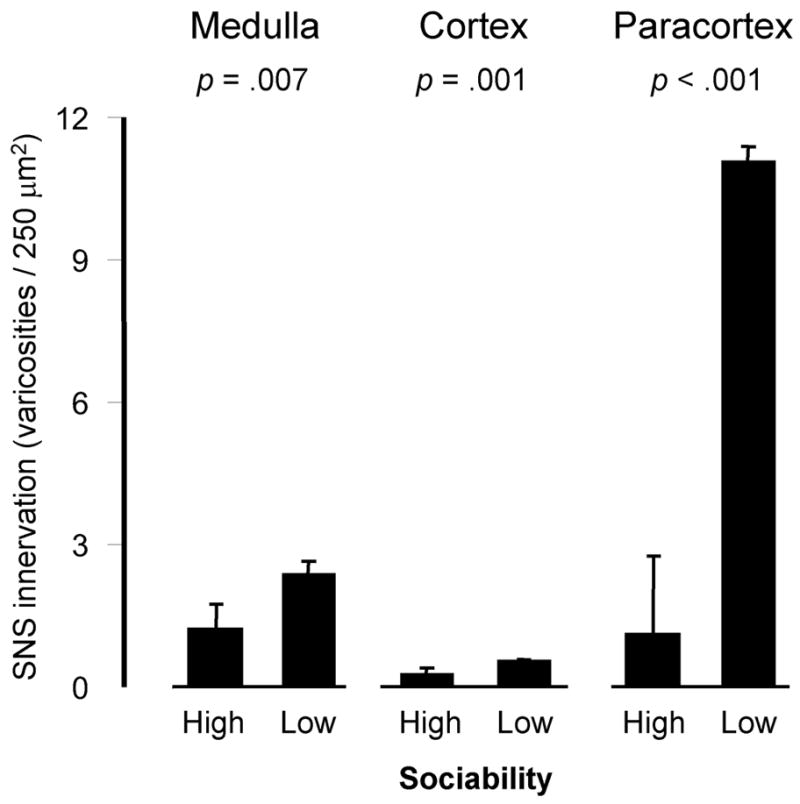

Analyses carried out within functionally distinct anatomic subregions of the lymph node found elevated parenchymal innervation in LS animals within all major anatomic subcompartments (Figure 2). These effects were most pronounced in the paracortex, where innervation density was elevated by 4.12-fold in LS animals relative to their HS counterparts (p <.0001). Innervation density was increased by 3.26-fold in the medulla (p =.0070), and by 3.10-fold in the cortex (p =.0011). Across these anatomic subcompartments, the magnitude of innervation difference associated with Sociability increased in direct proportion to the basal density of sympathetic innervation (i.e., the largest differential density was observed in the paracortex, which also showed the highest basal innervation density). Similar results emerged in analyses of continuous individual differences, with each 1-SD increase in Sociability associated with an average 4.47 ± 0.92 fewer catecholaminergic varicosities per tissue unit in the paracortex (p <.0001), an average −0.91 ± 0.25 fewer in the medulla (p =.0003), and an average −0.24 ± 0.09 fewer in the cortex (p =.0082; data not shown).

Figure 2. Sociability and innervation of lymph node anatomic subcompartments.

Density of parenchymal catecholaminergic varicosities (mean ± standard error) within distinct anatomic sub-compartments of lymph nodes from Low and High Sociable macaques.

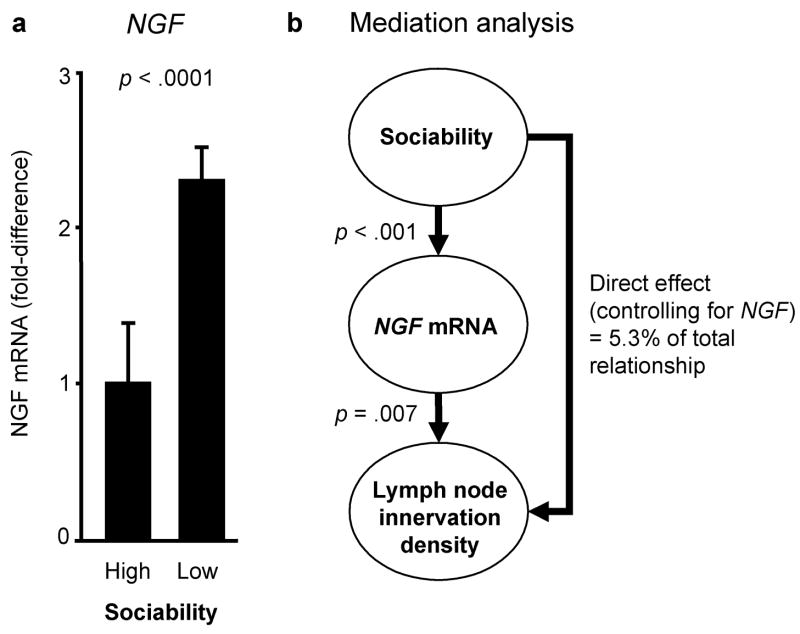

NGF gene expression

To determine whether observed differences in the catecholaminergic innervation of lymphoid tissue might stem from alterations in the expression of NGF, the key neurotrophic factor that supports growth and maintenance of peripheral sympathetic fibers (Levi-Montalcini, 1987; Farinas, 1999), we assayed expression of NGF mRNA using quantitative RT-PCR. Results showed significantly greater concentration of NGF mRNA in lymph nodes from LS animals (2.3-fold elevation relative to HS animals, p <.0001) (Figure 3a). NGF mRNA concentrations emerged as a quantitatively plausible mediator of Sociability-related differences in innervation in multivariate statistical mediation analyses (Figure 3b) (Baron and Kenny, 1986; Hoyle and Kenny, 1999), with results indicating that NGF variation alone could potentially account for 94.7% of Sociability-related differences in lymphoid innervation density (p =.0099 by Sobel’s test). NGF concentrations were strongly related to increased innervation density in analyses controlling for Sociability (p =.0427), and could account for all significant Sociability-related differences in innervation (i.e., no significant residual effect of Sociability remained after control for NGF, p =.1485).

Figure 3. NGF gene expression and Sociability-related differences in lymph node innervation.

(a) Expression of NGF mRNA in lymph nodes from High and Low Sociable animals (mean ± standard error). (b) Statistical analysis of NGF expression as a mediator of Sociability-related differences in lymph node innervation.

Immunoregulatory gene expression

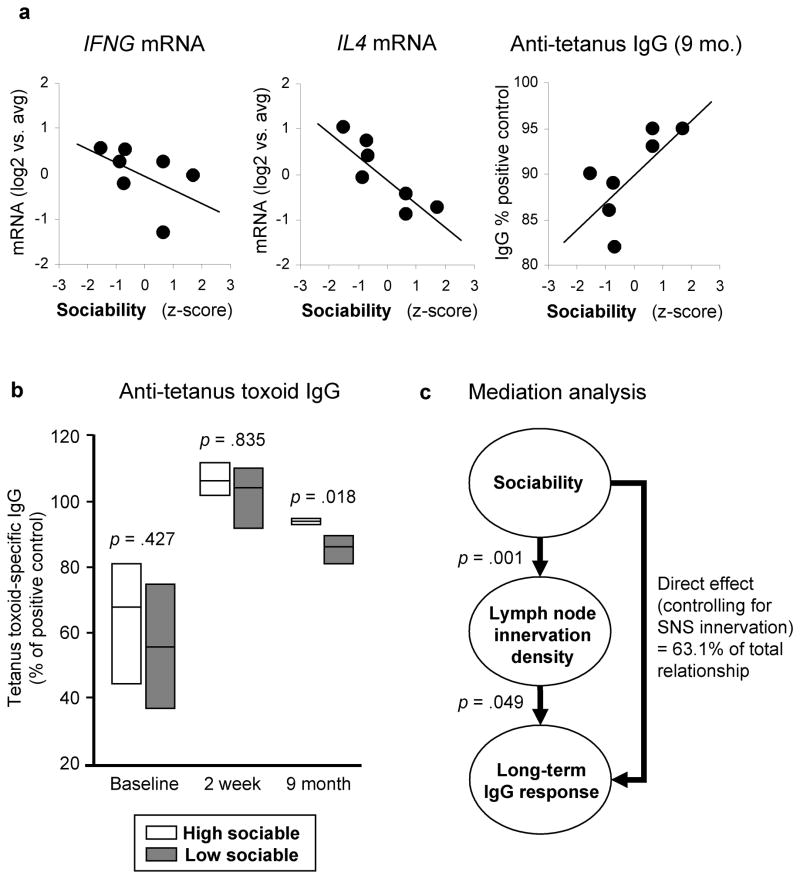

To assess the potential immunoregulatory correlates of Sociability-related differences in lymph node innervation, we assayed lymph node expression of genes encoding the Th1 cytokine interferon-γ (IFNG) and the Th2 cytokine IL-4 (IL4) (Table 2). Relative to HS animals, tissues from LS animals showed slightly greater expression of IFNG (1.35-fold elevation, p =.0340) and significantly greater expression of IL4 (2.48-fold, p =.0002), resulting in a net reduction in the overall equilibrium of Th1/Th2 signaling (.55-fold, p =.0401). Similar results were observed in analyses treating Sociability as a continuous measure of individual differences in relationship to all lymph nodes examined (correlation with IFNG, r = −.526, p =.0058; correlation with IL4, r = −.683, p <.0001), and in relationship to mean gene expression levels within each animal (Figure 4a). The density of parenchymal catecholaminergic varicosities was not significantly correlated with IFNG (r = +.353, p =.1268), but did show a significant positive relationship to IL4 (r = +.488, p =.0291).

Table 2.

IFNG and IL4 mRNA expression as a function of Sociability.

| Analyte | High Sociable | Low Sociable |

|---|---|---|

| IFNG | 0.86 ±.16 | 1.16 ±.17 |

| IL4 | 0.64 ±.18 | 1.57 ±.11 |

| IFNG/IL4 ratio | 1.35 ±.22 | 0.74 ±.28 |

All values represent mean ± standard error of expression level relative to average mRNA expression across all samples (after normalization to ACTB expression levels).

Figure 4. Sociability and IgG response to tetanus vaccination.

(a) Relationship between individual differences in Sociability (z-score) and average expression of IFNG mRNA (r = −.668, p =.100) or IL4 mRNA (r = −.849, p =.016) over all biopsied lymph nodes for each animal, or each animal’s plasma anti-tetanus toxoid IgG level at 9 months post-immunization (r = +.820, p =.046). (b) Anti-tetanus toxoid IgG levels measured prior to vaccination, 2 weeks post-immunization, and 9 months post-immunization. Boxes cover the range of observed IgG values, with a horizontal bar at the average value. (c) Statistical analysis of lymph node SNS innervation density as a mediator of Sociability-related differences in tetanus-specific IgG at 9 months post-vaccination.

Antibody response to vaccination

To define the functional impact of Sociability-related differences in lymph node innervation, we assayed secondary IgG responses to a tetanus toxoid booster vaccination. At baseline, tetanus-specific IgG levels varied substantially, and did not differ significantly as a function of Sociability (p =.427) (Figure 4b). Peak tetanus-specific IgG levels were also similar at 2 weeks post-vaccination (p =.835), but LS animals showed significantly lower IgG levels at a 9-month follow-up (p =.018). Similar results emerged when Sociability was analyzed as a continuous measure of individual differences, with nonsignificant associations observed at baseline (r = +.332, p =.446) and during peak response (r = +.116, p =.805), followed by a positive relationship between Sociability and plasma IgG levels at 9 months (r = +.707, p =.048; Figure 4a). Thus, Sociability-related differences in immunobiology do not appear to substantially affect the acute phase of a secondary antibody response, but LS animals do show poorer long-term maintenance of such responses.

Consistent with the possibility that differences in catecholaminergic innervation might mediate differential antibody responses, parenchymal varicosity density was inversely correlated with tetanus toxoid-specific IgG levels at 9 months post-vaccination (r =−.553, p =.0497). Quantitative mediation analyses estimated that 37.9% of that total relationship could be attributable to differential innervation (p =.0080; Figure 4c). However, a significant residual effect of Sociability also remained after control for lymph node innervation (p =.0070), suggesting that other factors also contribute. Tetanus toxoid IgG levels at 9 months post-vaccination showed a significant positive correlation with IFNG/IL4 expression ratios (r = +.422, p =.0316).

DISCUSSION

Results of this study suggest that Sociability-related differences in immune function may stem from underlying structural differences in the sympathetic innervation of lymphoid tissue. Compared to rhesus macaques that were High in Sociability (HS), Low Sociable (LS) animals showed significantly greater density of catecholaminergic varicosities throughout all regions of the lymph node parenchyma (paracortex, cortex, and medulla). Differential innervation was linked to increased expression of the key sympathetic neurotrophin, NGF, and statistical mediation analysis indicated that differential NGF expression could account for much of the sympathetic densification observed in LS animals. A functional impact of differential innervation was suggested by data showing correlated alterations in the expression of key immunoregulatory cytokine genes under basal conditions (IFNG and IL4), and long-term differences in secondary IgG responses to vaccination. These results are consistent with other recent data documenting systematic alterations in lymphoid sympathetic innervation (Madden, et al., 1997; Kelley, et al., 2003; Sloan, et al., 2007b; Sloan, et al., 2007c), and establish individual differences in social behavior as an additional correlate of lymphoid tissue neurobiology.

Several limitations of the present study need to be considered when interpreting its findings. The present results come from a small number of animals sampled from the tails of the Sociability distribution. Future studies are needed to replicate these findings in a larger sample spanning the entire range of variation in social temperament. In addition, this observational study design cannot decisively resolve causal relationships between Sociability and lymphoid innervation. Most theoretical accounts of Sociability would suggest that correlated variations in both factors stem from shared underlying determinants in CNS response to threat or uncertainty (Kagan, 1994). That hypothesis is consistent with recent studies showing experimental effects of stress on sympathetic innervation of lymphoid tissue (Sloan, et al., 2007b; Sloan, et al., 2007a), but it is also possible that primary differences in lymphoid innervation might causally affect social tendencies (e.g., via cytokine effects on the brain (Dantzer and Kelley, 2007)). It is also conceivable that variations in social behavior might directly impact lymphoid innervation (i.e., independently of a common CNS determinant, for example, by altering individual exposure to socially-transmitted pathogens (Boyce, et al., 1995; Cole, 2006)). Experimental manipulations of social temperament and/or lymphoid innervation will ultimately be required to define causal relationships. Similar issues impact the interpretation of NGF as a mediator of differential innervation. Experimental studies have shown that NGF activity is a necessary and sufficient determinant of lymphoid tissue innervation density (Carlson, et al., 1995; Carlson, et al., 1998; Kannan, et al., 1996). Although the quantitative mediation analyses presented here are consistent with that hypothesis, clear attribution of these effect to NGF will require experimental manipulation (e.g., NGF neutralization or genetic over-expression).

Analyses of cytokine gene expression under basal conditions and secondary IgG response to vaccination suggest that Sociability-related differences in lymphoid innervation may have functional implications for immunobiology. The differential secondary antibody responses of LS and HS animals is consistent with previous data linking LS characteristics to quantitative reductions in vaccine-induced antibody response (Coe, et al., 1987; Glaser, et al., 1992; Maninger, et al., 2003; Pressman, et al., 2005). However, the observed Th2 skew in IFNG/IL4 expression ratios in lymph nodes from LS animals seems paradoxical in light of the poorer long-term maintenance of vaccine-induced IgG response in these animals. A potential explanation is suggested by the empirical observation that a high IFNG/IL4 expression ratio was associated with better IgG response maintenance in this study. Th2 cytokine profiles are essential for IgE and IgG1 responses, but high IL4 levels can inhibit production of IgG2a, IgG3, and IgG4 (Snapper and Paul, 1987). Total IgG responses to tetanus booster vaccination include substantial contributions from the later isotypes (Feehally, et al., 1986), and the relative elevation of IL4 in lymph nodes from LS animals (and in densely innervated lymph nodes) might have undermined the long-term maintenance of those components of the total IgG response. Such dynamics do not appear to affect the initial phase of secondary antibody response (i.e., at the 2-week time-point), but both low Sociability and dense lymphoid innervation are inversely correlated with total IgG levels 9 months after vaccination. The emergence of such correlations despite substantial time lags between the assessment of antibody response and lymphoid innervation (which occurred ~10 months after the final IgG sample was drawn) implies that Sociability-related differences in immune regulation are relatively stable over time.

The impact of Sociability on clinical disease was not assessed in this study, and represents an important topic for future research. Based on the present data linking low Sociability to increased lymphoid innervation, and previous data linking lymphoid innervation to viral pathogenesis (Sloan, et al., 2006; Sloan, et al., 2007b), it can be speculated that LS animals might show increased vulnerability to viral infections and other immune-mediated diseases (see additional evidence by Capitanio, Abel et al., 2008). That speculation remains to be tested experimentally, but it would be consistent with the long-observed clinical relationships that motivated the present inquiry into relationships between social temperament and lymphoid tissue regulation by the autonomic nervous system (Broadbent, et al., 1984; Cohen, et al., 1997; Totman, et al., 1980; Cohen, et al., 2003; Cole, et al., 1997; Cole, et al., 2003; Capitanio, et al., 1999).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne Stevens and Srinivasan ThyagaRajan for protocols for glyoxylic acid chemofluorescence; Christine Brennan, Erna Tarara, Greg Vicinio, Carmel Stanko, Laura Del Rosso, Kristen Cooman, Nicole Maninger, and the Veterinary, Animal Care, and Research Services staff of the CNPRC for study conduct; Harry Vinters and the UCLA AIDS Institute for access to BSL2+ cryostat; Jesusa Arevalo, Caroline Sung, and Cathey Heron for administrative support; and Michael Irwin for thoughtful discussions of this research. These studies were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH049033), the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease and Neurological Disorders and Stroke (AI/NS052737), the National Cancer Institute (CA116778), the University of California Universitywide AIDS Research Program (CC99-LA-02), the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology in the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA, the UCLA AIDS Institute and the James B. Pendelton Charitable Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell IR, Jasnoski ML, Kagan J, King DS. Is allergic rhinitis more frequent in young adults with extreme shyness? A preliminary survey. Psychosom Med. 1990;52:517–525. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Lorton D, Lubahn C, Felten DL. Innervation of lymphoid organs - association of nerves with cells of the immune system and their implications in disease. In: Ader R, Felten DL, Cohen N, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology. 3. Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. pp. 55–111. [Google Scholar]

- Block J. A study of affective responsiveness in a lie-detection situation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1957;55:11–15. doi: 10.1037/h0046624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Chesney M, Alkon A, Tschann JM, Adams S, Chesterman B, Cohen F, Kaiser P, Folkman S, Wara D. Psychobiologic reactivity to stress and childhood respiratory illnesses: results of two prospective studies. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:411–422. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent DE, Broadbent MH, Phillpotts RJ, Wallace J. Some further studies on the prediction of experimental colds in volunteers by psychological factors. J Psychosom Res. 1984;28:511–523. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(84)90085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck R, Miller RE, Caul WF. Sex, personality, and physiological variables in the communication of affect via facial expression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1974;30:587–596. doi: 10.1037/h0037041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Abel K, Mendoza SP, Blozis S, McChesney MB, Cole S, Mason WA. Personality and serotonin transporter genotype interact with social context to affect immunity and viral set-point in simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.05.006. In Press - this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Baroncelli S. The relationship of personality dimensions in adult male rhesus macaques to progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Brain Behav Immun. 1999;13:138–154. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Lerche NW, Mason WA. Social stress results in altered glucocorticoid regulation and shorter survival in simian acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1998;95:4714–4719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. Confirmatory factor analysis of personality structure in adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Am J Primatol. 2005;65:289–294. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SL, Albers KM, Beiting DJ, Parish M, Conner JM, Davis BM. NGF modulates sympathetic innervation of lymphoid tissues. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5892–5899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05892.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SL, Fox S, Abell KM. Catecholamine modulation of lymphocyte homing to lymphoid tissues. Brain Behav Immun. 1997;11:307–320. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SL, Johnson S, Parrish ME, Cass WA. Development of immune hyperinnervation in NGF-transgenic mice. Exp Neurol. 1998;149:209–220. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatr Dev. 1986;4:167–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Rosenberg LT, Fischer M, Levine S. Psychological factors capable of preventing the inhibition of antibody responses in separated infant monkeys. Child Dev. 1987;58:1420–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM., Jr Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA. 1997;277:1940–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Turner R, Alper CM, Skoner DP. Sociability and susceptibility to the common cold. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:389–395. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. The complexity of dynamic host networks. In: Deisboeck TS, Kresh KY, editors. Complex Systems Science in Biomedicine. New York: Springer; 2006. pp. 605–629. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Kemeny ME, Fahey JL, Zack JA, Naliboff BD. Psychological risk factors for HIV pathogenesis: mediation by the autonomic nervous system. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1444–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01888-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE. Social identity and physical health: accelerated HIV progression in rejection-sensitive gay men. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:320–335. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Kemeny ME, Weitzman OB, Schoen M, Anton PA. Socially inhibited individuals show heightened DTH response during intense social engagement. Brain Behav Immun. 1999;13:187–200. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Hidalgo A, Sung C, Cole S. Adrenergic inhibition of innate antiviral response: PKA blockade of Type I interferon gene transcription mediates catecholamine support for HIV-1 replication. Brain Behav Immun. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre JC, Surgeon JW. Histochemical fluorescence of tissue and brain monoamines: results in 18 minutes using the sucrose-phosphate-glyoxylic acid (SPG) method. Neuroscience. 1976;1:451–453. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(76)90095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy BC. Relations of shyness and low sociability to regulation and emotionality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;68:505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MW. Personality and individual differences. New York: Plenum; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Farinas I. Neurotrophin actions during the development of the peripheral nervous system. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;45:233–242. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990515/01)45:4/5<233::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci AS. The human immunodeficiency virus: infectivity and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science. 1988;239:617–622. doi: 10.1126/science.3277274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feehally J, Brenchley PE, Coupes BM, Mallick NP, Morris DM, Short CD. Impaired IgG response to tetanus toxoid in human membranous nephropathy: association with HLA-DR3. Clin Exp Immunol. 1986;63:376–384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten DL, Felten SY, Bellinger DL, Carlson SL, Ackerman KD, Madden KS, Olschowki JA, Livnat S. Noradrenergic sympathetic neural interactions with the immune system: structure and function. Immunol Rev. 1987;100:225–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten DL, Felten SY, Carlson SL, Olschowka JA, Livnat S. Noradrenergic and peptidergic innervation of lymphoid tissue. J Immunol. 1985;135:755s–765s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten DL, Livnat S, Felten SY, Carlson SL, Bellinger DL, Yeh P. Sympathetic innervation of lymph nodes in mice. Brain Res Bull. 1984;13:693–699. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox CH, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Firpo A, Pizzo PA, Fauci AS. Lymphoid germinal centers are reservoirs of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:1051–1057. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauci M, King MG, Saxarra H, Tulloch BJ, Husband AJ. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profile of women with allergic rhinitis. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:533–540. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bonneau RH, Malarkey W, Kennedy S, Hughes J. Stress-induced modulation of the immune response to recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Psychosom Med. 1992;54:22–29. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am Psychol. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD. From mice to men: what can we learn about personality from animal research? Psychol Bull. 2001;127:45–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The neuropsychology of temperament. In: Strelau J, Angleitner A, editors. Explorations in temperament: International perspectives on theory and measurement. Plenum; London: 1991. pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Kenny DA. Statistical power and tests of mediation. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Statistical strategies for small sample research. Sage; Newbury Park: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE. The galvanic skin reflex as related to overt emotional expression. American Journal of Psychology. 1935;47:241. [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE. The study of patterns of emotional expression. In: Reymert ML, editor. Feelings and emotions: The Mooseheart Symposium. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1950. pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE. The longitudinal method in the study of personality. In: Iscoe I, Stevenson HW, editors. Personality development in children. University of Texas Press; Austin: 1960. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. Galen’s prophecy : temperament in human nature. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science. 1988;240:167–171. doi: 10.1126/science.3353713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Infant predictors of inhibited and uninhibited profiles. Psychol Sci. 1991;2:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan Y, Bienenstock J, Ohta M, Stanisz AM, Stead RH. Nerve growth factor and cytokines mediate lymphoid tissue-induced neurite outgrowth from mouse superior cervical ganglia in vitro. J Immunol. 1996;157:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SP, Moynihan JA, Stevens SY, Grota LJ, Felten DL. Sympathetic nerve destruction in spleen in murine AIDS. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:94–109. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm AP, Sanders VM. Suppression of antigen-specific Th2 cell-dependent IgM and IgG1 production following norepinephrine depletion in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:5299–5308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PD. Listening to Prozac: The Landmark Book About Antidepressants and the Remaking of the Self. New York: Penguin; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor 35 years later. Science. 1987;237:1154–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.3306916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, Fryer AJ, Klein DF. Social phobia: Review of a neglected anxiety disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:729–736. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300097013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Moynihan JA, Brenner GJ, Felten SY, Felten DL, Livnat S. Sympathetic nervous system modulation of the immune system. III. Alterations in T and B cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro following chemical sympathectomy. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;49:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Rajan S, Bellinger DL, Felten SY, Felten DL. Age-associated alterations in sympathetic neural interactions with the immune system. Dev Comp Immunol. 1997;21:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(97)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maninger N, Capitanio JP, Mendoza SP, Mason WA. Personality influences tetanus-specific antibody response in adult male rhesus macaques after removal from natal group and housing relocation. Am J Primatol. 2003;61:73–83. doi: 10.1002/ajp.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RG. Basics of Applied Statistics. New York: Wiley; 1986. Beyond ANOVA. [Google Scholar]

- Mouton PR. Introduction for Bioscientists. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press; 2002. Principles and Practices of Unbiased Stereology. [Google Scholar]

- Nance DM, Sanders VM. Autonomic innervation and regulation of the immune system (1987–2007) Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Rowe DC. Genetic and Environmental Etiology of Social Behavior in Infancy. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15:62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Derryberry D, Posner MI. A psychobiological approach to the development of temperament. In: Bates JE, Wachs TD, editors. Temperament: Individual differences at the interface of biology and behavior. America Psychological Association; Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders VM, Straub RH. Norepinephrine, the beta-adrenergic receptor, and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:290–332. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Wright CI, Shin LM, Kagan J, Rauch SL. Inhibited and uninhibited infants “grown up”: adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science. 2003;300:1952–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.1083703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Hori T, Nakane H. An interleukin-1 beta-induced noradrenaline release in the spleen is mediated by brain corticotropin-releasing factor: an in vivo microdialysis study in conscious rats. Brain Behav Immun. 1994;8:14–23. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1994.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. Stress-induced remodeling of lymphoid innervation. Brain Behav Immun. 2007a doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.06.011. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Capitanio JP, Tarara RP, Mendoza SP, Mason WA, Cole SW. Social stress enhances sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: mechanisms and implications for viral pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007b;27:8857–8865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1247-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Nguyen CT, Cox BF, Tarara RP, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. SIV infection decreases sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: The role of neurotrophins. Brain Behav Immun. 2007c doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.008. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Tarara RP, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. Enhanced replication of simian immunodeficiency virus adjacent to catecholaminergic varicosities in primate lymph nodes. J Virol. 2006;80:4326–4335. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4326-4335.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapper CM, Paul WE. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbury K, Gunnar MR. Adrenocortical activity and emotion regulation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59:108–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totman R, Kiff J, Reed SE, Craig JW. Predicting experimental colds in volunteers from different measures of recent life stress. J Psychosom Res. 1980;24:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(80)90037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:867–878. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard GC, Suomi SJ, Higley JD, Mehlman PT. CSF 5-HIAA and aggression in female macaque monkeys: species and interindividual differences. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:440–446. doi: 10.1007/pl00005489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.