Abstract

High-throughput studies in the Medical College of Wisconsin Program for Genomic Applications (Physgen) were designed to link chromosomes with physiological function in consomic strains derived from a cross between Dahl salt-sensitive SS/JrHsdMcwi (SS) and Brown Norway normotensive BN/NHsdMcwi (BN) rats. The specific goal of the vascular protocol was to characterize the responses of aortic rings from these strains to vasoconstrictor and vasodilator stimuli (phenylephrine, acetylcholine, sodium nitroprusside, and bath hypoxia) to identify chromosomes that either increase or decrease vascular reactivity to these vasoactive stimuli. Because previous studies demonstrated sex-specific quantitative trait loci (QTLs) related to regulation of cardiovascular phenotypes in an F2 cross between the parental strains, males and females of each consomic strain were included in all experiments. As there were significant sex-specific differences in aortic sensitivity to vasoconstrictor and vasodilator stimuli compared with the parental SS strain, we report the results of the females separately from the males. There were also sex-specific differences in aortic ring sensitivity to these vasoactive stimuli in consomic strains that were fed a high-salt diet (4% NaCl) for 3 wk to evaluate salt-induced changes in vascular reactivity. Differences in genetic architecture could contribute to sex-specific differences in the development and expression of cardiovascular diseases via differential regulation and expression of genes. Our findings are the first to link physiological traits with specific chromosomes in female SS rats and support the idea that sex is an important environmental variable that plays a role in the expression and regulation of genes.

Keywords: phenylephrine, acetylcholine, sodium nitroprusside, hypoxia, aortic rings

the vasculature must be able to respond appropriately to centrally and locally produced vasoactive substances to regulate blood flow to meet the metabolic needs of tissues. Alterations in the ability of vessels to respond to vasoconstrictor and vasodilator stimuli have been documented in many cardiovascular diseases (1, 3–5, 7, 8, 10–12, 37, 38, 52), and these contribute to the development and the progression of those diseases. An important epidemiological observation is that these cardiovascular pathologies develop and progress differently in men and women (32, 34, 47, 53, 56). Sex-based differences in vessel sensitivity to vasoactive compounds have been widely documented (2, 15–17, 36, 46, 55, 57, 61, 63, 70) and may play a role in the sexually dimorphic development and progression of cardiovascular diseases.

It is likely that sex plays an important role as an environmental variable in the regulation of genes related to cardiovascular functioning. For example, sex-specific differences in genetic architecture related to asthma (51), plasma insulin concentration (50), alcohol-related phenotypes (68), and susceptibility to Type 1 diabetes have been reported in humans and in other animal species (27). In another study, Weiss et al. (71) reported that the distribution of 11 of 17 quantitative traits studied in a founder population of Hutterites was statistically different between the sexes. A recently published (48) linkage analysis of traits related to blood pressure in males and females of an F2 cross of Dahl salt-sensitive SS/JrHsdMcwi (SS) and Brown Norway normotensive BN/SsNHsdMcwi (BN) rats revealed a sex-specific distribution of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) related to arterial blood pressure regulation and vascular reactivity in the genome. In that study, rat chromosomes 3, 6, 7, and 11 were identified as especially important in females (48), whereas aggregates of traits in male rats have been identified on chromosomes 1, 2, 7, and 18 (64). Taken together, these studies suggest that the genetic bases of the sex differences in the phenotypic expression of many diseases are related to differences in distribution of QTLs on chromosomes.

The underlying rationale for the present studies was to more clearly localize specific chromosomes containing genes that are important in regulating vascular reactivity in the female. In addition, we assessed the contribution of chromosomes to salt-induced changes in vascular reactivity since one group from each strain of rat was fed a high-salt diet (4.0% NaCl). This is important because alterations in vascular reactivity associated with high-salt diets (even without changes in blood pressure) have been documented (9, 19, 20, 22–25, 28, 30, 40, 41, 44, 60), and several studies (6, 26, 54) suggest that differences in sodium handling exist between males and females.

The intent of the Medical College of Wisconsin Program for Genomic Applications (Physgen; http://pga.mcw.edu) was to use consomic strains derived from SS and BN rat cross to link specific chromosomes with physiological functions in a variety of systems, including cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and biochemical. The overall goal of the Program for Genomic Applications was to begin the daunting task of linking physiological functions with specific chromosomes. The high-throughput studies of the vascular protocol were specifically designed to characterize the responses of aortic rings from a complete panel of consomic rats and their parental strains (SS/JrHsdMcwi and BN/NHsdMcwi) to phenylephrine (PE), acetylcholine (ACh), sodium nitroprusside (SNP), and reduced bath PO2. Because both males and females were studied, the results not only allowed for a careful comparison of phenotypic differences based on sex but also allowed these differences to be correlated with individual chromosomes, since the only genetic difference of each strain of rat from the parental acceptor strain is the chromosome received from the parental donor strain.

The global hypothesis of these studies is that chromosomal substitution between inbred parental rat strains exhibiting phenotypic differences related to vascular regulation (SS rat is a genetic model of hypertension that becomes hypertensive when fed a high-salt diet; BN rat remains normotensive on a high-salt diet) will reveal differences in vascular responses to constrictor and dilator stimuli in the consomic strains. Our ultimate hope (and the goal of the National Institutes of Health program funding these studies) is that these unique consomic rat strains, which are generated as a resource for the research community, can eventually be studied in detailed hypothesis-driven studies that investigate specific functions of genes on individual chromosomes.

We have previously reported the results of companion studies conducted in the males of these consomic strains (30). Since there was a sex-specific distribution of QTLs related to blood pressure and vascular reactivity in the F2 generation of this SS × BN cross, we hypothesized that there would be sexual dimorphism in the phenotypes measured in the consomic strain.

METHODS

Experimental animals.

All female rats (n = 195 for low salt and n = 222 for high salt) were produced and housed at the Medical College of Wisconsin Animal Resource Transgenic Barrier Facility. Rats were cared for according to established National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. The rats were part of a consomic rat panel in which each full-length chromosome (≥95% of the chromosome) from the inbred BN rat was substituted one at a time into the homogeneous background of the inbred SS rat. To create the consomic strains, BN and SS rats were mated to create a heterozygotic F1 generation. F1 progeny were backcrossed to the SS parental rat to obtain the SS genetic background. Offspring from this mating that were determined by genotyping to be heterozygotic for the target chromosome (i.e., the chromosome to be introgressed into parental genomic background) were backcrossed with the SS parental strain for four to eight generations using marker-assisted selection to keep the target chromosome heterozygous. Brother-sister intercrosses of those rats yielded rats that were homozygous at the target chromosome (BN/BN) and homozygotic for SS at all other chromosomes. (Note: For a complete genotype of each consomic and congenic rat, see the PhysGen website: http://pga.mcw.edu.)

Rats used in the present PhysGen study were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited animal care facility, and all procedures were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All rats were maintained from birth on 0.4% NaCl Teklad chow (3075S, Madison, WI). Three weeks before the study, at age 7 wk, one group of consomic rats (10 female rats of each consomic strain and two male parental SS rats for sentinels) were placed on a high-salt (4.0% NaCl) diet (Teklad, TD01454). Another group of consomic rats (10 females) and SS (2 males) sentinels of the same strain and number were maintained on the low-salt (0.4% NaCl) Teklad diet for 3 wk before the study.

Aortic rings from two male SS rats were studied simultaneously with the aortic rings of each strain of 10 female rats. These sentinel rats allowed us to confirm the internal consistency of the experimental protocol from strain to strain and week to week, since 10 male rats of same strain and stressor were studied at the same time. Phenotypes were measured in four groups of SS parental rats at four time periods over the year to account for any seasonal variations.

Experimental protocol.

Equipment used in these studies included a 16 tissue bath system with reservoirs and circulators (Radnoti Glass Technology, Monrovia, CA), Digi-Med tissue force analyzers (Micro Med DMSI-210, Louisville, KY), and Grass FT-03 force transducers. Gas tanks for delivery of 95, 10, 5, and 0% oxygen mixtures (with 5% CO2-balance N2) were obtained from Praxair (Burlington, WI).

The 10-wk-old rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) to produce a deep anesthesia. The chest of the rat was opened and a 3–5 cm length of aorta was removed and placed in a labeled Petri dish containing room temperature physiological salt solution (PSS) (119 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.17 mM MgSO4·7H20, 1.6 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 1.18 mM NaH2PO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 0.03 mM EDTA, 5.5 mM glucose, and 5.0 mM HEPES). The remaining blood was washed from the tissue by gently moving it back and forth in the PSS. The ends of the aorta were pinned to the Sylgard resin in a Petri dish. Under a dissecting microscope, fat and connective tissue were removed and the ends of the vessel were removed using fine #5 Dumont forceps and small Vannas scissors. The aorta was then divided into 3-mm wide rings. Triangular wire holders were inserted through the lumen of the vessel and connected to the force transducer and tissue holder rod in the vessel bath. Two aortic rings were mounted in fresh PSS for each rat. One ring was mounted in the 8-bath setup for the contraction and hypoxia studies and another was mounted in the 8-bath setup for the relaxation studies.

General procedures for aortic ring studies.

The tension on the rings was adjusted to 1.5-g passive force and allowed to equilibrate for 30 min in the bath with a 21% O2, 5% CO2, 74% N2 gas mixture. (Note: The high-throughput nature of the study necessitated that we pick a value for passive force midway between the values of 0.4–3.0 g found in the literature.) The rings were washed with fresh PSS every 10 min. Passive force was readjusted to 1.5 g as needed during this period. When passive force on the rings was stable at 1.5 g, the baseline reading on the tissue force analyzers was set at 0 g.

PE at a final concentration of 10−7 M was added to the bath to contract the ring, and force was allowed to stabilize for 5 min. ACh at a final concentration of 10−5 M was then added to the precontracted rings for 5 min to test for endothelial integrity. If a ring failed to contract in response to PE or failed to relax in response to ACh, it was replaced with an aortic ring from the same rat. After the initial test for vessel viability and endothelial integrity, the ring was washed 3 times with PSS, allowed to equilibrate, and then re-washed with fresh PSS at 10 min intervals until the measured active force stabilized at 0 g. The maximum contraction achievable by the ring was then determined by filling the bath with 80 mM K+ and adding PE at a final concentration of 10−5 M. Maximal contractile force generated in response to the combination of 80 mM K+ and 10−5 M PE was normalized to the wet weight of the aortic ring (determined at the end of the experiment). After determining the maximum contraction of the aortic rings, the vessels were allowed to stabilize and washed with PSS every 10 min until the measured active force returned to 0 g.

Contraction protocol.

The contraction protocol was performed on a single aortic ring from each rat. Ten female rats from each strain were studied within a 1-wk period (maximum of 8 rings per day). Cumulative concentration-response curves to PE, an α-adrenergic agonist that is widely used to test adrenergic vasoconstrictor sensitivity in isolated blood vessels, were created by increasing the PE concentration in the tissue bath by successive addition of appropriate dilutions of stock solutions to achieve final bath concentrations of 1 nM to 300 μM PE. The rings were then washed with PSS, allowed to equilibrate, and rewashed with fresh PSS at 5- to 10-min intervals until active force returned to a stable value of 0 g.

ACh and SNP protocol.

The relaxation protocol was performed on a single aortic ring from each rat. With few exceptions, rings studied in the relaxation protocols were from the same animals studied for the contraction experiments. Ten female rats from each strain were studied within one wk (maximum of 8 rings per day).

In one subset of the consomic strains, vessel responses to the endothelium-derived, NO-mediated vasodilator ACh were determined, followed by evaluation of vessel responses to the NO donor SNP in the same ring, after 30 min of equilibration in PSS that was changed every 5 min. In another subset of strains, aortic responses to SNP and hypoxia (see below) were not studied to expedite the movement of the large groups of rats demanded by the high-throughput design of the Program for Genomic Applications. In each of these subsets, the aortic rings were precontracted with 0.1 μM PE, and cumulative concentration-response curves to ACh were created by increasing the ACh concentration in the tissue bath by successive addition of appropriate dilutions of stock solutions to achieve final bath concentrations of 1 nM to 30 M ACh. In the subset of experiments in which vessel responses to SNP sensitivity were determined to evaluate vascular sensitivity to NO, cumulative concentration-response curves to SNP were created by increasing the SNP concentration in the tissue bath by successive addition of appropriate dilutions of stock solutions to achieve final bath concentrations of 0.1 nM to 3 M SNP. [Note: For typical concentration response curves for the above agents see Kunert et al. (30).]

Hypoxic relaxation protocol.

A variety of studies have demonstrated that vascular sensitivity to changes in oxygen availability are significantly altered in many forms of hypertension (31, 39, 42), including Dahl SS hypertension (20), and by elevated dietary salt intake, independent of an elevation in arterial blood pressure (43, 45, 69). With this in mind, we tested the sensitivity of aortic rings to stepwise reductions in tissue bath PO2 in a subset of the consomic strains. The rings used for this hypoxic relaxation protocol were the same ones used for the PE contraction protocol in those strains. In those studies, the rings were precontracted with PE at a final concentration of 0.1 μM and allowed to stabilize at a maximum response (∼10 min). Then, the gas equilibration mixture in the tissue bath was changed from 21% O2, 5% CO2, 74% N2 to one containing 95% O2-5% CO2. After 10 min at 95% O2-5% CO2, the oxygen concentration in the bath was reduced in a step-wise fashion at 20-min intervals to mixtures containing 10% O2, 5% O2, and 0% O2, with 5% CO2 and the balance N2. Since the volume of each tissue bath was small (5 ml) equilibration with the gases requires only a few minutes. To verify that the ring was viable at the end of the hypoxic relaxation protocol, the oxygen concentration in the bath was returned to 95% O2-5% CO2 for 20 min. If the aortic ring did not contract and develop a force approximately equal to the initial force development in response to 95% O2, the force values obtained during exposure to hypoxia were eliminated from the analysis.

Data and statistical analyses.

Analog to digital conversions of force waveforms were accomplished with a Digi-Med System Integrator Model 210 Micro-Med. The converted data was automatically transferred from the system Integrator into a spreadsheet and analyzed with GraphPad Prism software. Sensitivity to each agent was expressed as the negative log of EC50, which is directly calculated in the Graph Pad Prism program. All data are summarized as means ± SE. Differences between means were assessed by a conventional ANOVA or, if Levene's test showed that the groups had unequal variances, by a nonparametric ANOVA. This was followed by Dunnett's test to compare all consomic strains to the SS parental strain. Comparisons were made between an individual consomic strain and the SS parental strain on the same diet or within the same strain on two different diets. Complete sets of raw data for all consomic and congenic strains are available, along with statistical analyses, on the PhysGen website. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Differences in aortic ring sensitivity in BN and consomic strains versus the parental SS strain.

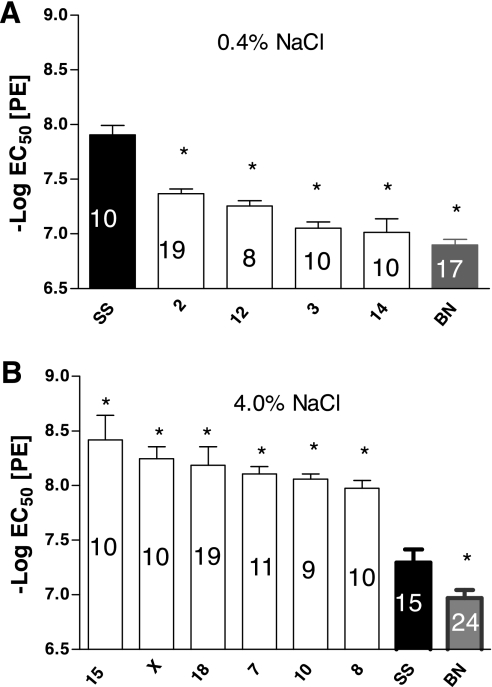

(Note: For the sake of clarity in each figure, we present only the data that were significantly different from those in the SS parental strain.) The sensitivity of the aortic rings from the SS and BN parental strains and the derived consomic strains to PE (expressed as the negative log of the EC50) are summarized in Fig. 1. When the rats were maintained on a low-salt diet, aortic rings of the SS-2BN, SS-12BN, SS-3BN, SS-14BN, and BN strains were less sensitive to PE than the SS parental strain, indicated by a lower negative log of the EC50 (Fig. 1A). None of the strains were more sensitive to PE than the SS parental strain. When the rats were maintained on a high-salt diet, aortic rings from the SS-15BN, SS-XBN, SS-18BN, SS-7BN, SS-10BN, and SS-8BN rats were more sensitive to PE than those of the parental SS strain, as judged by a significantly higher negative log of the EC50, while aortic rings from the parental BN strain were less sensitive to PE than those of the SS parental strain, as judged by a significantly lower negative log of the EC50 (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the sensitivity to phenylephrine (PE; −log EC50) of aortic rings from female consomic rats to those of the Dahl salt-sensitive parental strain (SS, black fill) after the rats were fed a low-salt (LS) diet (0.4% NaCl; A) or a high-salt (HS) diet (4.0% NaCl; B) for 3 wk. Numbers within each bar indicate number of rats (n) for that group. Data are summarized as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the SS parental strain.

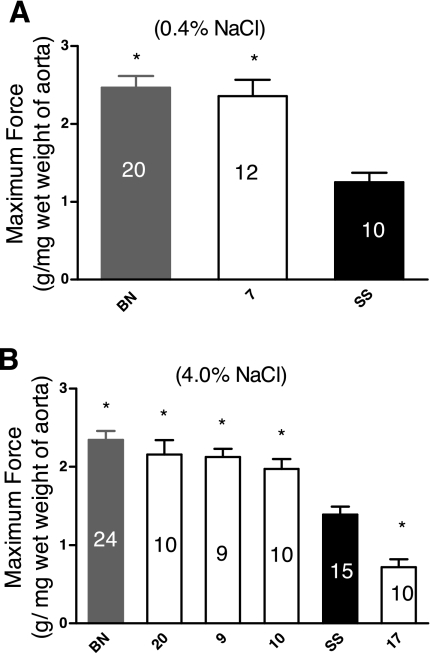

Figure 2 summarizes the maximum force generated by the aortic rings, normalized to the wet weight of the ring. Aortic rings from the BN and SS-7BN strains developed a significantly greater force than those from the SS parental strain when the rats were fed a low-salt diet (Fig. 2A). No strains developed less maximum force than the SS parental strain. In rats fed a high-salt diet, aortic rings from BN, SS-20BN, SS-9BN, and SS-10BN rats developed more force than those from the SS parental strain, while rings from the SS-17BN strain developed less force (Fig. 2B). In these experiments, there were no differences in aortic weight in the consomic strains compared with the parental SS rats, and no evidence of either vascular hypertrophy or atrophy in any of the strains, judging from data obtained in the PhysGen Histology protocol (see PhysGen website).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of maximum contractile force (g/mg wet wt of aorta) developed in response to 80 mM K+ plus 10−5 M PE in aortic rings from consomic female rats compared to those of the SS parental strain (black fill) after the rats were fed a LS diet (0.4% NaCl; A) or a HS diet (4.0% NaCl B) for 3 wk. Numbers within each bar indicate number of rats (n) for that group. Data are summarized as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the SS parental strain.

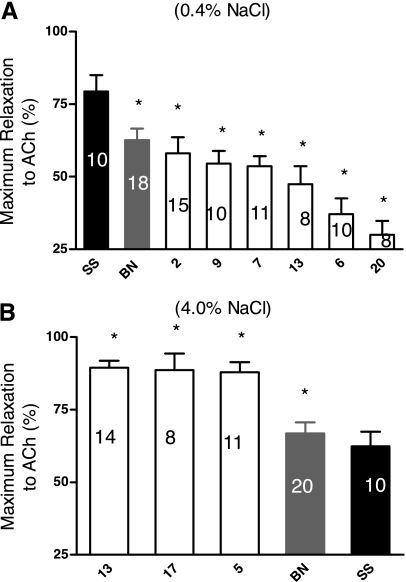

Studies of ACh-induced relaxation revealed several significant differences in the maximum relaxation of the aortic rings to ACh (Fig. 3), but there were no differences in aortic sensitivity to ACh between the parental SS and any of the consomic strains (data not shown). When the rats were fed a low-salt diet, aortas from the BN parental, SS-2BN, SS-9BN, SS-7BN, SS-13BN, SS-6BN, and SS-20BN consomic strains all relaxed less than those of the SS parental strain. In rats fed a high-salt diet, maximum relaxation to ACh was greater in aortic rings of SS-13BN, SS-17BN, SS-5BN, and the BN parental compared with those from the SS parental strain.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the maximum relaxation (%) to acetylcholine (ACh) in phenylephrine-contracted (0.1 μM) aortic rings from female consomic rats compared to those from femalesfrom the SS parental strain (black fill) after the rats were fed a LS diet (0.4% NaCl; A) or a HS diet (4.0% NaCl; B) for 3 wk. Numbers within each bar indicate number of rats (n) for that group. Data are summarized as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the SS parental strain.

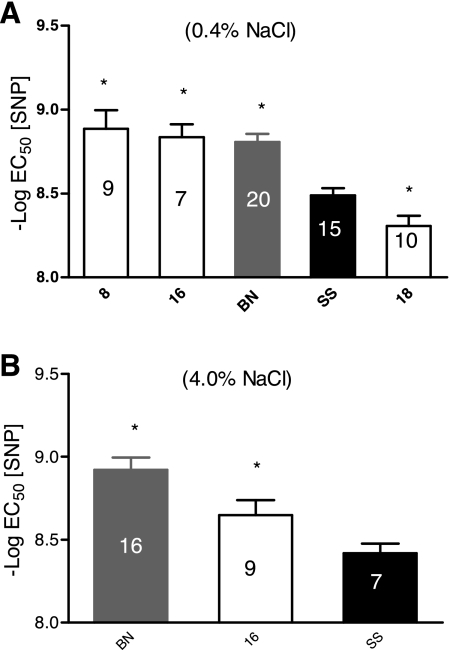

Figure 4 summarizes the sensitivity of the aortic rings to SNP expressed as the negative log of EC50. In rats fed a low-salt diet, aortic rings from SS-8BN and SS-16BN consomic rats and the BN parental strain were more sensitive to SNP (i.e., had a significantly higher negative log of the EC50) than those from the SS parental strain, while rings from SS-18BN rats were less sensitive (had a significantly lower negative log of the EC50 to SNP) than those of the SS parental strain (Fig. 4A). When the rats were fed a high-salt diet, aortic rings from the SS-16BN and BN strains had a significantly higher negative log of the EC50 to SNP (were more sensitive to SNP) than those of the parental SS strain (Fig. 4B). The maximum relaxation to SNP was not different in any strain compared with the SS parental rats, and there was no effect of a high-salt diet on maximum relaxation to SNP in any strain (data not shown). The range of maximum relaxation to SNP among all strains was between 96.3 ± 3 to 100%.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) sensitivity (−log EC50) of aortic rings from female consomic rats compared to those of the SS parental strain (black fill) after the rats were fed a LS diet (0.4% NaCl; A) or a HS diet (4.0% NaCl; B) for 3 wk. The numbers within each bar indicate the number of animals (n) for that group. Each ring was precontracted with PE (0.1 μM). Data are summarized as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the SS parental strain.

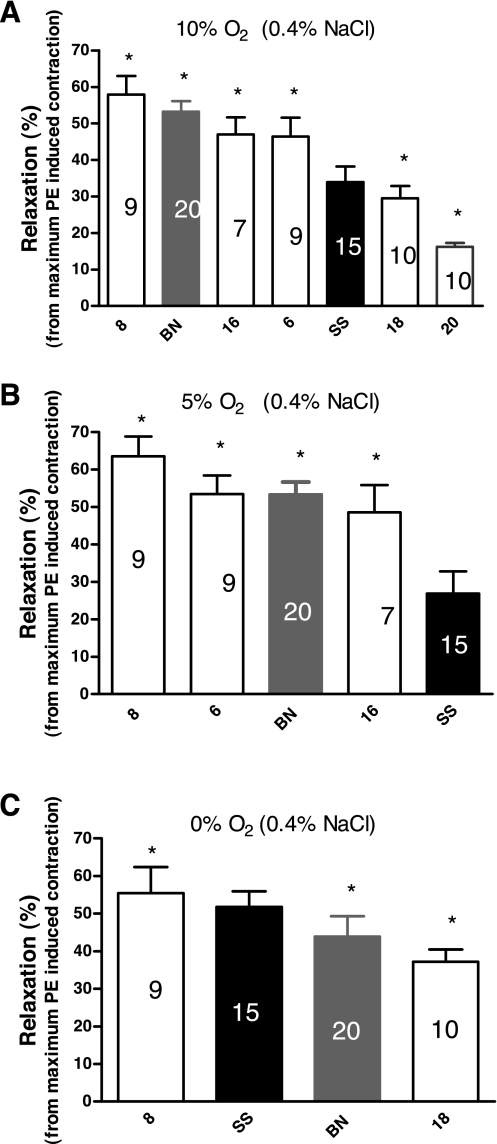

Figure 5 summarizes the sensitivity to the relaxing effect of three different levels of reduced PO2 in aortic rings from rats fed a low-salt diet, as judged by the percent relaxation of PE-induced contractions that occurred at each level of reduced PO2. In these experiments, aortic rings from the SS-8BN, BN parental, SS-16BN, and the SS-6BN strains were more sensitive to 10% O2 than those from the SS parental strain, while aortic rings from the SS-18BN and SS-20BN rats were less sensitive to 10% O2 than those from the SS parental strain. Aortas from SS-8BN, SS-6BN, BN parental, and SS-16BN rats relaxed more than those from the SS parental strain during exposure to 5% O2 in the tissue bath. Aortas from SS-8BN rats relaxed significantly more in response to 0% O2 in the tissue bath, compared with those from the SS parental strain, while aortas from SS-16BN rats and the BN parental strain relaxed less than those from the parental SS strain in response to this level of hypoxia. When the rats were fed a high-salt diet, there was no difference in aortic relaxation in response to 10% O2, 5% O2, or 0% O2 in the tissue bath in any of the strains (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the response of aortic rings of female consomic rats to three different levels of reduced PO2 [10% O2 (A), 5% O2 (B), or 0% O2 (C)] in the tissue bath versus aortas from the SS parental strain (black fill) after the rats were fed a LS diet (0.4% NaCl) for 3 weeks. Data are summarized as mean % of relaxation of PE-induced contraction ± SE, and numbers within each bar indicate number of rats (n) for that group. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the SS parental strain.

Effect of a high-salt diet on aortic ring sensitivity within strains.

Table 1 summarizes the effects of a high-salt diet on contractile parameters and the sensitivity of the aortic rings of female rats to different vasoactive stimuli within strains. In these experiments, a high-salt diet increased aortic ring sensitivity to PE in the SS-8BN, SS-9BN, SS-12BN, SS-14BN, and SS-15BN strains and reduced PE sensitivity in the SS and SS-17BN strains. The fast slope of PE-induced contraction was smaller in SS-7BN and larger in SS-18BN and SS-20BN rats fed a high-salt diet compared with animals fed a low-salt diet, and the slow slope of PE-induced contraction was increased in SS-10BN rats fed a high-salt diet compared with SS-10BN rats fed a low-salt diet. Maximum force development decreased in the SS-7BN, SS-11BN, SS-13BN, and SS-17BN strains when the animals were fed a high-salt diet and increased in SS-9BN and SS-10BN rats fed a high-salt diet.

Table 1.

Changes in sensitivity of the aortic ring of HS (4.0% NaCl) fed female rats as compared with the same strain on a LS (0.4% NaCl) diet

| Strain↓ | PE Sens. | Fast Slope PE | Slow Slope PE | Maximum Force | ACh Sens. | Maximum Relaxation to ACh | SNP Sens. | 10% O2 Sens. | 5% O2 Sens. | 0% O2 Sens. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇑ | |||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | |||||||

| 3 | ⇓ | |||||||||

| 4 | ⇓ | |||||||||

| 5 | ⇓ | |||||||||

| 6 | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇓ | |||||||

| 7 | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇓ | |||||||

| 8 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇓ | |||||

| 9 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇓ | |||||

| 10 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇓ | |||||||

| 11 | ⇓ | ⇓ | ||||||||

| 12 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 13 | ⇓ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 14 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 15 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 16 | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇓ | ||||||

| 17 | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇑ | |||||||

| 18 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||

| 19 | ||||||||||

| 20 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | |||||

| X |

SS, Dahl salt-sensitive SS/JrHsdMcwi rats; PE, phenylephrine; ACh, acetylcholine; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; HS, high salt; LS, low salt; Sens., sensitivity.

A high-salt diet decreased aortic sensitivity to ACh in SS-3BN, SS-4BN, SS-5BN, SS-7BN, and SS-10BN rats and increased aortic sensitivity to ACh in SS-2BN, SS-8BN, SS-18BN, and SS-20BN rats. A high-salt diet increased maximum relaxation in response to ACh in aortic rings from SS-6BN, SS-13BN, SS-17BN, and SS-20BN rats and decreased maximum relaxation in response to ACh in aortic rings from the SS parental strain and the SS-16BN and SS-18BN consomic strains. The sensitivity of aortic rings to the NO donor SNP was increased in the SS-16BN strain and reduced in the SS-8BN, SS-9BN, and SS-20BN strains fed a high-salt diet.

In the case of vessel sensitivity to reduced PO2, a high-salt diet was associated with an increase in aortic ring sensitivity to 10% O2 in the SS, SS-2BN, and SS-18BN rats and a reduced sensitivity to 10% O2 in the SS-6BN, SS-8BN, SS-9BN, and SS-16BN strains. Aortic sensitivity to 5% O2 was greater in SS-18BN and SS-20BN rats and lower in SS-6BN, SS-8BN, SS-9BN, and SS-16BN strains when the animals were fed a high-salt diet, compared with animals fed a low-salt diet. A high-salt diet also increased the sensitivity of aortic rings from SS-2BN and the SS-18BN rats to 0% O2 in the bath, compared with rats fed a low-salt diet.

Sex-specific differences in aortic ring sensitivity within strains (low-salt diet).

Table 2 summarizes the differences in contractile parameters and aortic ring sensitivity to PE, ACh, SNP and three levels of reduced PO2 (10% O2, 5% O2, and 0% O2) in females fed a low-salt diet (0.4% NaCl) compared with males fed a low-salt diet (26). These comparisons of phenotypes from male and female rats revealed several sex-specific differences in both contractile and vasodilator responses within strains.

Table 2.

Sensitivity of aortic rings of females on a LS diet (0.4% NaCl) as compared with males on a LS diet

| Strain↓ | PE Sens. | Fast Slope PE | Slow Slope PE | Maximum Force | ACh Sens. | Maximum Relaxation | SNP Sens. | 10% O2 Sens. | 5% O2 Sens. | 0% O2 Sens. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||

| 1 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 2 | ⇑ | ⇓ | ||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||

| 4 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 5 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||

| 7 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 8 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||

| 9 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 10 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 11 | ⇓ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 12 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 13 | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||

| 14 | ⇓ | ⇓ | ||||||||

| 15 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 16 | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | |||

| 17 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 18 | ⇓ | |||||||||

| 19 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 20 | ⇑ | ⇓ | ⇑ | |||||||

| X | ⇑ |

In the case of contractile responses, aortic rings of female SS, SS-12BN, SS-17BN, SS-19BN, and SS-XBN rats were significantly more sensitive to PE than aortic rings from male rats of the same strain. Aortic rings from SS-13BN and the SS-16BN females were less sensitive to PE than those of the males. The fast slope of PE-induced contraction was lower in aortic rings from female SS, SS-11BN, SS-13BN, SS-14BN, SS-16BN, and SS-18BN rats compared with the males of the same strain, and the slow slope of PE-induced contraction was significantly lower in aortic rings from female SS-13BN, SS-14BN, and SS-16BN rats compared with those of the corresponding males. The maximum contractile force attained by the aortic rings was significantly greater in females of the SS, SS-1BN, SS-2BN, SS-7BN, SS-8BN, SS-9BN, SS-11BN, SS-13BN, SS-16BN, SS-17BN, and SS-20BN strains compared with males from the same strains.

In the case of vessel responses to vasodilator stimuli, aortic rings from female SS-1BN, SS-5BN, SS-8BN, and SS-15BN rats were more sensitive to ACh than those of the males, while aortic rings from female SS-16BN and SS-20BN were less sensitive to ACh than those of the corresponding males. Aortic rings from female SS, SS-4BN, SS-10BN, SS-15BN, and SS-16BN had a greater maximum relaxation in response to ACh compared with those from male rats of the corresponding strain. The sensitivity of aortic rings from female SS-8BN, SS-9BN, SS-13BN, SS-16BN, and SS-20BN rats to SNP was greater than that of the corresponding males, but there were no differences in maximum relaxation in response to SNP, which was at or near 100% in all strains and in both genders.

In the case of vessel responses to reduced PO2, there were no sex-specific differences in vascular relaxation in response to 10% O2 in the tissue bath. However, aortic rings from female SS-13BN rats were more sensitive to 5% O2, while aortic rings from female SS-2BN rats were less sensitive to 0% O2 in the bath than aortic rings from males of the same strain.

Sex-specific differences in aortic ring sensitivity within strains (high-salt diet).

Table 3 summarizes the within-strain differences in the same parameters in female rats fed a high-salt diet (4.0% NaCl) compared with males fed a high-salt diet. In these studies, aortic rings from female SS-2BN and SS-13BN rats were less sensitive to PE, while aortic rings from female SS-5BN, SS-9BN, SS-10BN, and SS-12BN rats were more sensitive to PE than those of males from the same strain. The fast slope of PE-induced contraction was larger in female SS-9BN rats compared with the males. The slow slope of PE-induced contraction was larger in aortic rings from SS-10BN females compared with males from the same strain and smaller in aortic rings from SS-18BN females compared with the corresponding males. The maximum force of contraction attained by the aortic rings of the female SS, SS-3BN, SS-6BN, SS-7BN, SS-9BN, SS-10BN, SS-12BN, SS-15BN, SS-16BN, SS-17BN, SS-18BN, SS-19BN, and SS-20BN rats was greater than that attained by aortic rings from male rats of the same strain.

Table 3.

Sensitivity of aortic rings from females on a HS diet (4.0% NaCl) as compared with males on a HS diet

| Strain↓ | PE Sens. | Fast Slope PE | Slow Slope PE | Maximum Force | ACh Sens. | Maximum Relaxation | SNP Sens. | 10% O2 Sens. | 5% O2 Sens. | 0% O2 Sens. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||

| 3 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||

| 5 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 6 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||

| 7 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 8 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 9 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||

| 10 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | |||||||

| 11 | ||||||||||

| 12 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇓ | |||||||

| 13 | ⇓ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 14 | ||||||||||

| 15 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| 16 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 17 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 18 | ⇓ | ⇑ | ⇑ | |||||||

| 19 | ⇑ | |||||||||

| 20 | ⇑ | ⇑ | ||||||||

| X |

In the case of vasodilator stimuli, aortic sensitivity to ACh was greater in SS-6BN, SS-15BN, and SS-20BN females compared with the corresponding males and was lower in aortic rings from SS-9BN females compared with males of the same strain. Aortic rings from female SS-2BN, SS-8BN, and SS-13BN showed a greater maximum relaxation to ACh than those from male rats, while maximum relaxation to ACh was less in aortic rings of female SS-12BN rats compared with male rats from the same strain. Aortic rings from female SS-6BN and SS-18BN rats were more sensitive to SNP than those of the corresponding males. In the case of vessel responses to reduced PO2, aortic rings from female SS-2BN rats were more sensitive to the relaxing effect of 10% O2 and 5% O2 in the tissue bath than those of the corresponding males, and aortas from SS-6BN females were more sensitive to 0% O2 in the tissue bath than aortic rings from males of that strain.

DISCUSSION

The specific purpose of the vascular protocol of PhysGen was to reveal specific chromosomes that contain genes that may be involved in the regulation of vascular tone in the female. In addition, since the Dahl SS rat is an established genetic model of salt-sensitive hypertension, the present studies were also intended to reveal specific chromosomes that may contribute to differences in vascular reactivity that exist in experimental models of salt-sensitive hypertension in females. The global hypothesis of these studies is that chromosomal substitution (which can either increase or decrease responses to vasodilator and vasoconstrictor stimuli) between inbred parental rat strains exhibiting phenotypic differences will reveal differences in aortic responses to vasoconstrictor and vasodilator stimuli in the resulting consomic strains. The intent of the studies described herein was not to discover individual genes that are related to vascular reactivity but instead to determine the effect of chromosomal substitutions on standard tests of vascular reactivity.

The summarized data presented here are derived from a first-pass high-throughput screening of female rats from a consomic panel of an SS × BN cross plus the SS and BN parental strains. As such, these studies provide an important first step in linking phenotypic data to genomic data in the female and provide important evidence of a link between sex-specific differences in genetic architecture and sex-specific differences in physiological function. Significant changes in phenotypes related to vascular reactivity in consomic rat strains can provide valuable clues to design hypothesis-driven studies to identify individual genes or pathways affecting vascular reactivity.

One goal of this study was to use consomic rat strains to identify specific BN chromosomes that, when introduced into the SS genetic background, lead to either increases or decreases in vascular reactivity in the consomic strain compared with the SS parental strain (see Figs. 1–5). We also wanted to compare female and male consomic strains in terms of which strains had a significantly different aortic response to these vasoactive stimuli compared with the parental SS strain. For example, in male rats fed a low-salt diet, the aortic rings from SS-16, -7, -10, -13, and -11BN were significantly more sensitive to PE than those from the parental SS strain maintained on a low-salt diet (30). In contrast, there were no significant increases in PE sensitivity in aortic rings from female consomic strains fed a low-salt diet compared with those from SS female parental strain maintained on a low-salt diet. In contrast, substitution of chromosomes 3 and 14 from the Brown Norway rat into the SS genetic background reduced aortic ring sensitivity to PE in both male (30) and female consomic rats compared with the parental SS strain of the same sex. There were no differences in acetylcholine sensitivity (−Log EC50) between aortic rings from female SS parental rats vs. females from any of the consomic strains during either a low-salt or high-salt diet. However, aortic rings from male SS-16 and -YBN consomic rats fed a low-salt diet were significantly more sensitive to ACh than the male SS parental rats fed a low-salt diet, and aortic rings from consomic male SS-20, -9, and -13BN rats were significantly less sensitive to ACh than males from the SS parental strain that were maintained on a low-salt diet (30).

Another goal of the study was to use these consomic rat strains to identify specific BN chromosomes that lead to salt-induced changes in vascular reactivity (either increased or decreased responses to vasoactive stimuli) when they are introgressed into the SS genetic background (see Table 1). For example, in regard to salt-induced changes in aortic reactivity to ACh and PE, aortic rings of the female consomic strains SS-3, -4, -5, -7, and -10BN were less sensitive to ACh, and the rings of the female consomic strains SS-8, -9, -12, -14, and -15BN were more sensitive to PE when the rats were fed a high-salt diet. Salt-induced changes in vascular reactivity have been well documented (9, 19, 20, 22–25, 28, 30, 39, 40, 43, 59), and these consomic strains could be useful in studies investigating the genetic bases of these salt-induced changes in vascular reactivity. Of interest, as well, is the observation that these changes in vascular reactivity occurred in completely different female consomic strains than in the males (30). This supports the view that differences in genetic architecture and gene regulation can contribute importantly to sex-based differences in vascular reactivity and to the sex-based differences that have been noted in sodium handling (6, 27, 55).

The third goal of the present study was to compare changes in vascular reactivity in female consomic rat strains (fed either a high-salt or low-salt diet) with those of their male counterparts reported in a previous study (30) to assess whether genetic architecture affects vascular reactivity in the various strains of rats (see Tables 2 and 3). In the latter case, we compared the effect of substituting specific chromosomes on the reactivity of aortic rings to a variety of vasoactive stimuli in female consomic rats compared with the corresponding male consomic strains. Any differences in the effect of introducing specific BN chromosomes in those experiments were taken as an index of either the effect of genetic architecture on vascular reactivity or, possibly, sex-based differences in the physiological regulation of genes regulating vascular reactivity on various chromosomes.

The data at the outset can appear overwhelming, but if they are examined and analyzed in discrete units, we believe that they will be useful in parsing out the genetic bases of sex-specific differences in vascular reactivity. In particular, see Tables 2 and 3 for the female to male comparisons. Although each of the strains has unique characteristics, SS- 2, -6, -8, -9, -13, and -16BN seem to hold the most promise for discovering genes that are related to vascular reactivity in females and males, based on the number of sex-specific differences across the various vasoactive stimuli and the salt-induced alterations in those responses.

Although experimental evidence obtained in animal models and in humans suggests that estrogen plays an important role in modifying the response of blood vessels in females to vasoactive substances (29, 33, 35, 58, 62, 65–67), the results of the present study indicate that genetic architecture is sex specific and also contributes in an important way to sexual dimorphism in phenotypic expression. In this regard, the results of the present study suggest additional avenues of investigation in evaluating sex-specific determinants of vascular reactivity. It is highly likely that sex based differences in genetic architecture play a role in differential regulation of hormones, and it is just as probable that the hormonal environment plays a significant role in the regulation of genes on specific chromosomes. Differences in hormonal milieu and physiological regulation of genes could play an important role in the measured differences in vascular reactivity between the male and female consomic strains.

Since our initial question in these studies was not about the influence of sex hormones on vascular reactivity, per se, we did not ovariectomize the females or examine vaginal smears to determine the phase of estrus. However, given the fact that the rats were housed together for at least 3 wk, it is likely that their cycles were synchronized (59). In addition, in a pilot study of Sprague-Dawley rats (unpublished data) in which half of the females received DepoProvera to inhibit follicular development and prevent ovulation, there were no significant differences in vascular reactivity to any of the substances used between the groups. Nonetheless, it would be valuable to conduct these studies in ovariectomized female rats with and without hormonal replacement and/or inhibition of estrogen receptors to investigate the interplay among hormonal milieu, genes, and vascular reactivity.

Consomic strains have not yet been used extensively to study sex-specific differences in vascular reactivity at the microcirculatory level. However, it is interesting to note two studies by Drenjancevic-Peric et al. on the reactivity of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) from the male (20) and female (21) SS, SS-13BN, and BN to ACh and hypoxia. In those studies, MCA from both female and male SS rats exhibited a paradoxical constriction in response to hypoxia. In contrast, MCA from female SS dilated in response to ACh, while MCA from male SS constricted in response to ACh. Substitution of the BN chromosome 13 into the SS genetic background restored the dilation to ACh in the male, increased dilation to ACh in the female, and restored vascular relaxation in response to reduced PO2 in MCA of both male and female SS-13BN rats. One intriguing result of those studies was that the MCA from the BN female rat failed to dilate to hypoxia, in contrast to the significant relaxation of MCAs from the male BN. Substitution of BN chromosome 13 restored hypoxic dilation in the female SS-13BN consomic rats, indicating that a gene or genes responsible for the lack of hypoxic dilation of the MCA in the BN rat must be on chromosomes other than chromosome 13. Chromosomal substitutions to develop relevant consomic rat strains would be an ideal experimental model to study the questions that arise from those studies. For example, which chromosome contains a gene or genes that suppress hypoxic dilation of the MCA in female BN rats but not male BN rats? Does the estrous status of the female BN influence the response of the MCA to reduced PO2 and, if so, in which consomic strains of the SS × BN cross?

Another advantage of using chromosomal substitution to produce consomic strains is the ability to rapidly create overlapping congenic strains from the consomic strains that express the phenotypic traits of interest [for a complete discussion of the scientific advantages of the consomic strain, see Cowley et al. (13)]. These overlapping strains would narrow the region of the QTL and make it easier to identify genes that are involved in regulating the expression of these phenotypes. As such, the female consomic strains characterized in this study can be useful experimental tools to examine the genetic bases of sex-specific differences in vascular reactivity.

An example of this strategy is a recent study by Moreno et al. (49), who recently reported the results of studies conducted in a series of overlapping congenic lines covering chromosome 13, generated from an intercross between the consomic SS-13BN and the SS rat. Those investigators were specifically seeking regions of BN chromosome 13 that provided protection against the salt-induced increase in blood pressure characteristics of the SS rat. Of particular interest for the studies we report here is their finding that the salt-induced increase in blood pressure was attenuated in the female congenic strains containing the renin region of BN chromosome 13 but not in males of the corresponding congenic strain. The latter observation indicates the presence of a sex-specific element on chromosome 13 that affects the regulation of blood pressure. In a similar fashion, the initial phenotypic characterizations performed in this study and other publications arising from this program (e.g, our earlier publication describing phenotypic differences in vascular reactivity in male consomic and parental rat strains; Ref. 30) will hopefully serve as a road map for subsequent studies by other laboratories employing the consomic rat strains generated by the PhysGen resource (see website).

It is clear that consomic rat strains can provide unique and extremely valuable information regarding phenotypic alterations in disease models such as the Dahl SS model of salt-sensitive hypertension For example, the importance of altered function of chromosome 13 in contributing to salt sensitivity of blood pressure (14), impaired angiogenic responses to muscle stimulation (18), and loss of cerebral vascular relaxation to vasodilator stimuli (20–22) in SS rats was identified by using SS-13BN consomic rats to investigate the basis of these alterations.

However, there are some caveats regarding the use of high-throughput consomic strategies to investigate the genetic basis of altered vascular regulation (or altered regulation of other physiological systems). As we have stated previously, it is important not to over-interpret the data because the chromosome that is introgressed into the parental strain has lost its native genetic background (in this case BN) and the normal recipient genetic background (in this case SS) loses a native chromosome, which could alter the native gene-to-gene interactions and contribute to the differences between the consomic and parental strains (30). Nonetheless chromosomal substitutions in consomic strains still enable us to evaluate the relative contributions of the BN chromosomes to the control of the aortic responses to selected vasodilators and vasoconstrictors in the female rat, independent of the BN genomic background and/or evaluate the effect of the removal of a single parental SS chromosome on vascular reactivity in the female SS rat.

Another caveat associated with the use of high-throughput studies to evaluate vascular function arises from the logistics of conducting such studies. For example, high-throughput studies in which multiple aortic rings are obtained from individual rats to evaluate sensitivity to both constrictor and dilator stimuli in multiple animals each day necessitate the use of standardized parameters such as passive resting force and PE concentrations to precontract the aortic rings for vascular relaxation studies. This reduces the ability of investigator to optimize specific experimental conditions (e.g., PE concentration to precontract the aortas). In the present study, PE sensitivity was increased in some of the strains and reduced in others. In cases when the vessels are more sensitive to PE, the PE concentration used to precontract the vessel for vascular relaxation studies would likely produce a more active tone in the aortic ring than it would in cases where PE sensitivity was unchanged or reduced. This could either reduce the responses to vasodilator stimuli by overriding the action of the vasodilator or amplify vascular relaxation by providing a more active tone to inhibit. In the present study, a total of 110 individual comparisons of PE sensitivity were made between strains, between diets within strains, and between genders within strains. Of the 18 cases in which PE sensitivity was increased, responses to vasodilator stimuli were unaffected in 13, reduced in 3, amplified in 1, and mixed (increased response to some dilators and reduced response to others) in 1. Of the 12 cases in which PE sensitivity was reduced, responses to vasodilator stimuli were unaffected in 3, reduced in 1, increased in 5, and mixed in three. In cases where high-throughput studies demonstrate that vasoconstrictor sensitivity is altered in specific strains or under specific experimental conditions, additional studies would be warranted to determine whether vasodilator sensitivity is altered under equivalent levels of precontraction. The latter studies are a good example of how important clues obtained from high-throughput screening would lead to follow-up studies that investigate specific problems proposed by the initial high-throughput studies.

Since blood pressure is an important factor that influences vascular tone and reactivity, the absence of a report on the blood pressure measurements of the parental and the consomic rats may seem like an oversight. However, the blood pressure measurement in the vascular protocol described herein was under conditions of very deep anesthesia, and ultimately those blood pressure measurements were not considered to be useful data for our analysis. However, each strain of rat that was studied in the vascular protocol was also studied in the renal and respiratory protocol. Since these blood pressure measurements were not obtained from the specific rats that we studied and were captured under dissimilar circumstances, we thought it best not to include these data in our analysis. However, the data are available at http://pga.mcw.edu.

Perspectives and Significance

The overall intent of the PhysGen program is that the consomic rat strains that are generated through this program will provide a resource of unique rat strains that can eventually be studied in detailed hypothesis-driven studies investigating specific functions of genes on that chromosome. In the case of vascular reactivity studies, genes on individual chromosomes can either increase or decrease vessel responses to vasoconstrictor or vasodilator stimuli. As is evident by the data, the chromosomal regions involved in the regulation of vascular reactivity and that may be influenced by a high-salt diet are considerably different in female rats compared with males of the same strain. This finding is consistent with those of other investigators who have studied sex-specific genetic architecture (27, 50, 51, 71) and underscores the importance of considering sex as an important variable in cardiovascular studies. Because these consomic strains have <5% allelic difference from the parental strain (13), they can serve as powerful control animals compared with the parental strain and can serve as a beginning step in localizing genes that influence vascular reactivity in the female.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study linking phenotypic traits related to vascular reactivity with the genotype in the female Dahl SS rat. The results of these experiments underscore the importance of including females in studies of vascular reactivity. In this regard, sex should certainly be considered as an important environmental factor in the analysis of any cardiovascular disease, since gene-environment interactions have a great deal of influence on the penetrance and expressivity of complex traits, such as responses to vasoactive substances.

GRANTS

This project is one of five Program for Genomic Applications funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01 HL-66579) and was supported by Grant HL-65289 and HL-72920 (to J. H. Lombard).

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory technologists that completed these studies: Sarah Kaplan, Jennifer Labecki, Jaime Petersen, Kathryn Privett, Janelle Curran, Julie Antczak, Jess Powlas, Maurice Jones, Alison Kriegel, Janelle Yarina, and Julie Holding.

Present address: I. D. Peric, Univ. Josip Juraj Strossmayer, Sch. Med., Dept. Physiol. and Immunol., J Huttlera 4, Osijek 31000, Croatia.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adeagbo ASO, Zhang XD, Patel D, Joshua IG, Wang Y, Sun XC, Igbo IN, Oriowo MA. Cyclo-oxygenase-2, endothelium and aortic reactivity during deoxycorticosterone acetate salt-induced hypertension. J Hypertens 23: 1025–1036, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajayi AA, Hercule H, Cory J, Hayes BE, Oyekan AO. Gender difference in vascular and platelet reactivity to thromboxane A(2)-mimetic U46619 and to endothelial dependent vasodilation in Zucker fatty (hypertensive, hyperinsulinemic) diabetic rats. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 59: 11–24, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allahdadi KJ, Walker BR, Kanagy NL. Mechanism of augmented vascular reactivity to endothelin (ET-1) in rats with sleep apnea-induced hypertension. Hypertension 44: 543, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balakireva LA, Mahanova NA, Nosava MN, Dymshitz GM, Markel AL, Yakobson GS. Vascular reactivity in NISAG hypertensive rats. Bull Exp Biol Med 126: 762–764, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballew JR, Watts SW, Fink GD. Effects of salt intake and angiotensin II on vascular reactivity to endothelin-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296: 345–350, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barron LA, Green GM, Khalil RA. Gender differences in vascular smooth muscle reactivity to increases in extracellular sodium salt. Hypertension 39: 425–432, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauersachs J, Bouloumie A, Mulsch A, Wiemer G, Fleming I, Busse R. Vasodilator dysfunction in aged spontaneously hypertensive rats: changes in NO synthase III and soluble guanylyl cyclase expression, and in superoxide anion production. Cardiovasc Res 37: 772–779, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell DM, Johns TE, Lopez LM. Endothelial dysfunction: implications for therapy of cardiovascular diseases. Ann Pharmacother 32: 459–470, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boegehold MA Effect of dietary salt on arteriolar nitric oxide in striated muscle of normotensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H1810–H1816, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boegehold MA Microvascular structure and function in salt-sensitive hypertension. Microcirculation 9: 225–241, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briones AM, Xavier FE, Arribas SM, Gonzalez MC, Rossoni LV, Alonso MJ, Salaices M. Alterations in structure and mechanics of resistance arteries from ouabain-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H193–H201, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JD Overview of physiology, vascular biology, and mechanisms of hypertension. J Manag Care Pharm 13: S6–S8, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowley AW, Liang M, Roman RJ, Greene AS, Jacob HJ. Consomic rat model systems for physiological genomics. Acta Physiol Scand 181: 585–592, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowley AW, Roman RJ, Kaldunski ML, Dumas P, Dickhout JG, Greene AS, Jacob HJ. Brown Norway chromosome 13 confers protection from high salt to consomic Dahl S rat. Hypertension 37: 456–461, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crews JK, Murphy JG, Khalil RA. Gender differences in Ca2+ entry mechanisms of vasoconstriction in Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 34: 931–936, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dantas APV, Scivoletto R, Fortes ZB, Nigro D, Carvalho MHC. Influence of female sex hormones on endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor prostanoid generation in microvessels of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 34: 914–919, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David FL, Carvalho MHC, Cobra ALN, Nigro D, Fortes ZB, Reboucas NA, Tostes RCA. Ovarian hormones modulate endothelin-1 vascular reactivity and mRNA expression in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Hypertension 38: 692–696, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Resende MM, Amaral SL, Moreno C, Greene AS. Congenic strains reveal the effect of the renin gene on skeletal muscle angiogenesis induced by electrical stimulation. Physiol Genomics 33: 33–40, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.dos Santos L, Goncalves MV, Vassallo DV, Oliveira EM, Rossoni LV. Effects of high sodium intake diet on the vascular reactivity to phenylephrine on rat isolated caudal and renal vascular beds: endothelial modulation. Life Sci 78: 2272–2279, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drenjancevic-Peric I, Greene AS, Kunert MP, Lombard JH. Arteriolar responses to vasodilator stimuli and elevated P(O2) in renin congenic and Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Microcirculation 11: 669–677, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drenjancevic-Peric I, Kunert MP, Lombard JH. Vascular responses of cerebral resistance arteries in female Dahl S, consomic SS-13BN(2) and Brown Norway rat strains (Abstract). J Vasc Res 43: 54, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drenjancevic-Peric I, Lombard JH. Introgression of chromosome 13 in Dahl salt-sensitive genetic background restores cerebral vascular relaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H957–H962, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drenjancevic-Peric I, Phillips SA, Falck JR, Lombard JH. Restoration of normal vascular relaxation mechanisms in cerebral arteries by chromosomal substitution in consomic SS.13BN rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H188–H195, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisbee JC, Sylvester FA, Lombard JH. Contribution of extrinsic factors and intrinsic vascular alterations to reduced arteriolar reactivity with high-salt diet and hypertension. Microcirculation 7: 281–289, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frisbee JC, Sylvester FA, Lombard JH. High-salt diet impairs hypoxia-induced cAMP production and hyperpolarization in rat skeletal muscle arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1808–H1815, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerhold D, Bagchi A, Lu MQ, Figueroa D, Keenan K, Holder D, Wang YH, Jin H, Connolly B, Austin C, Alonso-Galicia M. Androgens drive divergent responses to salt stress in male versus female rat kidneys. Genomics 89: 731–744, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivakine EA, Mortin-Toth SM, Gulban OM, Valova A, Canty A, Scott C, Danska JS. The Idd4 locus displays sex-specific epistatic effects on type 1 diabetes susceptibility in nonobese diabetic mice. Diabetes 55: 3611–3619, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaeckel M, Simon G. Altered structure and reduced distensibility of arteries in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. J Hypertens 21: 311–319, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knuuti J, Kalliokoski R, Janatuinen T, Hannukainen J, Kalliokoski KK, Koskenvuo J, Lundt S. Effect of Estradiol-drospirenone hormone treatment on myocardial perfusion reserve in postmenopausal women with angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol 99: 1648–1652, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunert MP, Drenjancevic-Peric I, Dwinell MR, Lombard JH, Cowley AW Jr, Greene AS, Kwitek AE, Jacob HJ. Consomic strategies to localize genomic regions related to vascular reactivity in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Physiol Genomics 26: 218–225, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunert MP, Roman RJ, Falck JR, Lombard JH. Differential effect of cytochrome P-450 omega-hydroxylase inhibition on O2-induced constriction of arterioles in SHR with early and established hypertension. Microcirculation 8: 435–443, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurtulmus N, Bos S, Arslan S, Kurt T, Tukek T, Ince N. Differences in risk factors for acute coronary syndromes between men and women. Acta Cardiol 62: 251–255, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahm T, Patel KM, Crisostomo PR, Markel TA, Wang M, Herring C, Meldrum DR. Endogenous estrogen attenuates pulmonary artery vasoreactivity and acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: the effects of sex and menstrual cycle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E865–E871, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Legato MJ, Gelzer A, Goland R, Ebner SA, Rajan S, Villagra V, Kosowski M. Gender-specific care of the patient with diabetes: review and recommendations. Gend Med 3: 131–158, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung SWS, Teoh H, Keung W, Man RYK. Non-genomic vascular actions of female sex hormones: Physiological implications and signalling pathways. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 822–826, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, Stallone JN. Estrogen potentiates vasopressin-induced contraction of female rat aorta by enhancing cyclooxygenase-2 and thromboxane function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1542–H1550, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lind L, Granstam SO, Millgard J. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypertension: A review. Blood Press 9: 4–15, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linder AE, Weber DS, Whitesall SE, D'Alecy LG, Webb RC. Altered vascular reactivity in mice made hypertensive by nitric oxide synthase inhibition. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 46: 438–444, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Fredricks KT, Roman RJ, Lombard JH. Response of resistance arteries to reduced PO2 and vasodilators during hypertension and elevated salt intake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H869–H877, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Fredricks KT, Roman RJ, Lombard JH. Response of resistance arteries to reduced PO2 and vasodilators during hypertension and elevated salt intake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H869–H877, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Rusch NJ, Lombard JH. Loss of endothelium and receptor-mediated dilation in pial arterioles of rats fed a short-term high salt diet. Hypertension 33: 686–688, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lombard JH, Hess ME, Stekiel WJ. Neural and local control of arterioles in SHR. Hypertension 6: 530–535, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lombard JH, Sylvester FA, Phillips SA, Frisbee JC. High-salt diet impairs vascular relaxation mechanisms in rat middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1124–H1133, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Losada M, Torres SH, Hernandez N, Lippo M, Sosa A. Muscle arteriolar and venular reactivity in two models of hypertensive rats. Microvasc Res 69: 142–148, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marvar PJ, Falck JR, Boegehold MA. High dietary salt reduces the contribution of 20-HETE to arteriolar oxygen responsiveness in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1507–H1515, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McBride SM, Flynn FW, Ren J. Cardiovascular alteration and treatment of hypertension–do men and women differ? Endocrine 28: 199–207, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Metz CNB, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson D, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL, Rogers WJ, Pohost GM, Lerman A, Quyyumi AA, Sopko G. Insights from the NHLBI-sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study part II: Gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 21S–29S, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreno C, Dumas P, Kaldunski ML, Tonellato PJ, Greene AS, Roman RJ, Cheng Q, Wang Z, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW Jr. Genomic map of cardiovascular phenotypes of hypertension in female Dahl S rats. Physiol Genomics 15: 243–257, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno C, Kaldunski ML, Wang T, Roman RJ, Greene AS, Lazar J, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW Jr. Multiple blood pressure loci on rat chromosome 13 attenuate development of hypertension in the Dahl S hypertensive rat. Physiol Genomics 31: 228–235, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.North KE, Franceschini N, Borecki IB, Gu CC, Heiss G, Province MA, Arnett DK, Lewis CE, Miller MB, Myers RH, Hunt SC, Freedmans BI. Genotype-by-sex interaction on fasting insulin concentration–The HyperGEN study. Diabetes 56: 137–142, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ober C, Pan L, Phillips N, Parry R, Kurina LA. Sex-specific genetic architecture of asthma-associated quantitative trait loci in a founder population. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 6: 241–246, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oda E, Abe M, Kato K, Watanabe K, Veeraveedu PT, Aizawa Y. Gender differences in correlations among cardiovascular risk factors. Gend Med 3: 196–205, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Onat A, Hergenc G, Keles I, Dogan Y, Turkmen S, Sansoy V. Sex difference in development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease on the way from obesity and metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 54: 800–808, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pechere-Bertschi A, Maillard M, Stalder H, Bischof P, Fathi M, Brunner HR, Burnier M. Renal hemodynamic and tubular responses to salt in women using oral contraceptives. Kidney Int 64: 1374–1380, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Polk DM, Naqvi TZ. Cardiovascular disease in women: sex differences in presentation, risk factors, and evaluation. Curr Cardiol Rep 7: 166–172, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Brokat S, Tschope C. Role of gender in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 49: 241–251, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robert R, Chagneau-Derrode C, Carretier M, Mauco G, Silvain C. Gender differences in vascular reactivity of aortas from rats with and without portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20: 890–894, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosano GMC, Vitale C, Marazzi G, Volterrani M. Menopause and cardiovascular disease: the evidence. Climacteric 10: 19–24, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schank JC, McClintock MK. A coupled-oscillator model of ovarian-cycle synchrony among female rats. J Theor Biol 157: 317–362, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider MP, Inscho EW, Pollock DM. Attenuated vasoconstrictor responses to endothelin in afferent arterioles during a high-salt diet. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1208–F1214, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwertz DW, Penckofer S. Sex differences and the effects of sex hormones on hemostasis and vascular reactivity. Heart Lung 30: 401–426, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sellers MM, Stallone JN. Selective estrogen receptor agonists enhance blood pressure and vascular reactivity to vasopressin in aortic coaretation-induced hypertensive female rats (Abstract). FASEB J 21: A1419, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva-Antonialli MM, Tostes RCA, Fernandes L, Fior-Chadi DR, Akamine EH, Carvalho MHC, Fortes ZB, Nigro D. A lower ratio of AT(1)/AT(2) receptors of angiotensin II is found in female than in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovas Res 62: 587–593, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stoll M, Kwitek-Black AE, Cowley AW Jr. Harris EL, Harrap SB, Krieger JE, Printz MP, Provoost AP, Sassard J and Jacob HJ. New target regions for human hypertension via comparative genomics. Genome Res 10: 473–482, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sullivan JC, Sasser JM, Pollock JS. Sexual dimorphism in oxidant status in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R764–R768, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsang SY, Yao XQ, Chan HY, Chan FL, Leung CSL, Yung LM, Au CL, Chen ZY, Laher I, Huang Y. Tamoxifen and estrogen attenuate enhanced vascular reactivity induced by estrogen deficiency in rat carotid arteries. Biochem Pharmacol 73: 1330–1339, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van den Meiracker AH, de Ronde W. Gender differences in vascular disease: not a simple explanation. J Hypertens 25: 1193–1194, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vendruscolo LF, Terenina-Rigaldie E, Raba F, Ramos A, Takahashi RN, Mormede P. Evidence for a female-specific effect of a chromosome 4 locus on anxiety-related behaviors and ethanol drinking in rats. Genes Brain Behav 5: 441–450, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang J, Roman RJ, Falck JR, de la CL, Lombard JH. Effects of high-salt diet on CYP450-4A ω-hydroxylase expression and active tone in mesenteric resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1557–H1565, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wangensteen R, Moreno JM, Sainz J, Rodriguez-Gomez I, Chamorro V, Luna JDD, Osuna A, Vargas F. Gender difference in the role of endothelium-derived relaxing factors modulating renal vascular reactivity. Eur J Pharmacol 486: 281–288, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weiss LA, Pan L, Abney M, Ober C. The sex-specific genetic architecture of quantitative traits in humans. Nat Genet 38: 218–222, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]