Abstract

A Social StoriesTM intervention package was used to teach 2 students with autism to read Social Stories, answer comprehension questions, and engage in role plays. Appropriate social behaviors increased and inappropriate behaviors decreased for both participants, and the effects were maintained for up to 10 months. This intervention package appears to be useful in inclusive classroom environments and does not require intensive supervision of the child's behavior.

Keywords: autism, inclusion classroom, role play, social skills training, Social Stories

Social StoriesTM (Gray & Garand, 1993) are a frequently used treatment method for children with autism; however, the research literature on their use includes only a small number of well-controlled experimental studies (e.g., Green et al., 2006). Studies have often combined Social Stories with other instructional methods such as prompting (e.g., Swaggart et al., 1995), reinforcement (e.g., Swaggart et al.), and self-evaluation (e.g., Thiemann & Goldstein, 2001), making it difficult to determine the unique or additive effects of intervention components. However, Reynhout and Carter (2006) found little difference in effect sizes across studies using Social Stories alone and those using Social Stories intervention packages.

Social Stories have been experimentally investigated in home settings (Lorimer, Simpson, Myles, & Ganz, 2002), self-contained special education/resource classrooms (Delano & Snell, 2006), and campus outdoor areas (Sansosti & Powell-Smith, 2006) but not in general education inclusion settings. Including students with autism in general education classrooms can create meaningful social opportunities with peers without disabilities (Fryxell & Kennedy, 1995) and is considered a preferred alternative to self-contained educational settings (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 1997). Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to examine the use of a Social Stories intervention package on the social communication behaviors of 2 students with autism enrolled in full-inclusion kindergarten classrooms.

Method

Participants, Setting, and Target Behaviors

Matt, a 6-year-old Asian American boy, and Ted, a 5-year-old Caucasian boy, attended two different general education kindergarten classrooms full-time at a public elementary school. A teaching assistant was assigned to Matt's classroom, and Ted had a teaching assistant who was assigned to accompany him during the entire school day. Both participants had been diagnosed with autism and had language skills that were appropriate for the Social Stories intervention (standardized assessment scores are available from the first author).

Training sessions took place in the morning before the start of the school day in private rooms at the students' school. Hour-long observation sessions were conducted in the participants' classrooms during circle time and centers time on the same day as training sessions. Matt's target behaviors were inappropriate social interactions (e.g., standing or sitting within a few centimeters of peers, causing peers to lean or move away), appropriate hand raising (e.g., above shoulder and vertical rather than horizontal extension), and inappropriate vocalizations (e.g., monosyllables, noises, comments irrelevant to classroom activities). Target behaviors for Ted were appropriate hand raising, appropriate social initiations (e.g., approaching peers and asking to play), and inappropriate vocalizations (e.g., comments irrelevant to classroom activities). Data were collected using a frequency count for appropriate social initiations, inappropriate social interactions, and inappropriate vocalizations. During each observation session, data were collected on one to three behaviors per participant. Measurement of hand raising was based on the number of opportunities presented during circle time (i.e., questions posed by the teacher) and is presented as the percentage of opportunities resulting in appropriate hand raising.

Design and Procedure

A multiple probe design across behaviors was used.

Baseline

During baseline, data were collected on the target behaviors during hour-long observation sessions described above. Established classroom rules and discipline procedures remained in effect.

Social Stories Intervention Package

Participants received intervention on an individual basis. Intervention sessions occurred one to four times per week. Matt's intervention lasted for 5 weeks and consisted of 13 intervention sessions. Ted received intervention for 18 sessions over 10 weeks. Sessions occurred prior to the start of the school day and lasted 10 to 20 min, depending on the number of stories read and the number of behaviors practiced. Participants read only stories that pertained to the behaviors targeted for intervention on a given day (i.e., one to three stories per day). There was one story per target behavior for each participant. A total of six stories were used in this study. Stories were written using Gray's (1995) guidelines. The text was presented on white paper with no pictures, and the font size was 22 to 26 points (i.e., the largest font that allowed each story to fit on a single page). The intervention consisted of three steps: (a) reading the story, (b) answering comprehension questions, and (c) role play. These steps were always presented in this order.

First, the participant was instructed to read the story aloud or to choose another reading option, such as having the instructor read the story aloud or to read the story silently. Matt always read the story aloud, and Ted read the story aloud except for three sessions in which he chose to read silently.

Next, the instructor asked three questions about the story to test for comprehension (e.g., “What can I try to do when my teacher asks questions?”). Three questions were written for each story and were printed out as a reference for the instructor, but the instructor was free to alter the order of the questions and general wording. If the student was unable to answer the question correctly or did not provide an answer, they were prompted to reread the portion of the story that pertained to the question.

The final step was a role play of the social situation described in the story. First, the instructor introduced the role play by verbally describing the situation and target behavior. Next, the instructor, participant, and another adult acted out the situation, which ended with the performance of the target behavior. For example, for hand raising, the instructor said, “Let's pretend we're in circle time. I'll be the teacher and will read this story to you. When I ask a question, don't forget to raise your hand.” The instructor then read a short passage from a book and asked a question (i.e., teacher role). At this point, the participant could raise his hand and wait to be called on to give an answer. The other adult sometimes acted as a student, listened to the story, and occasionally raised his or her hand in response to the teacher's question. In other scenarios, the adult acted as a peer with whom the participant interacted. Verbal prompts were delivered if the participant had difficulty completing any of the three steps, and praise was delivered after successful completion of each of the three steps.

Follow-Up

Follow-up probes were conducted with Matt at 1, 3, 5, and 10 months after completion of the intervention. Follow-up probes were conducted with Ted at 2 and 7 months.

Interobserver Agreement, Treatment Integrity, and Social Validity

All data collectors were trained graduate students. Two data collectors independently collected data for 32% of sessions. Agreement was calculated for frequency measures by dividing the lower frequency of a target behavior by the higher frequency and converting this ratio to a percentage. Interobserver agreement for the percentage of opportunities measure was calculated by dividing the lower percentage-of-opportunities observation score by the higher percentage of opportunities score and converting this ratio to a percentage. Agreements for Matt's target behaviors were 95% (hand raising), 100% (inappropriate social interaction), and 88% (inappropriate vocalizations). One day's data were removed from Matt's data set due to low interobserver agreement. For Ted, agreements were 94% (hand raising), 100% (social initiations), and 92% (inappropriate vocalizations). To measure treatment integrity, a checklist was created that listed the steps of the intervention. The checklist consisted of (a) reading the story, (b) asking three comprehension questions, (c) engaging in a role play of the target behavior, and (d) delivering prompts or positive reinforcement following each comprehension question and at appropriate times during the role play. Treatment integrity data were collected during 39% of treatment sessions, and the percentage of intervention steps implemented correctly was 96% (range, 83% to 100%). Finally, classroom teachers, teaching assistants, and parents were asked to rate statements regarding the social validity (i.e., importance of skills taught, perceived effectiveness, appropriateness, future use) of the intervention package on a Likert-type scale from 1 (negative) to 5 (positive). Mean rating of social validity statements was 4.3 (range, 3 to 5 across questions).

Results and Discussion

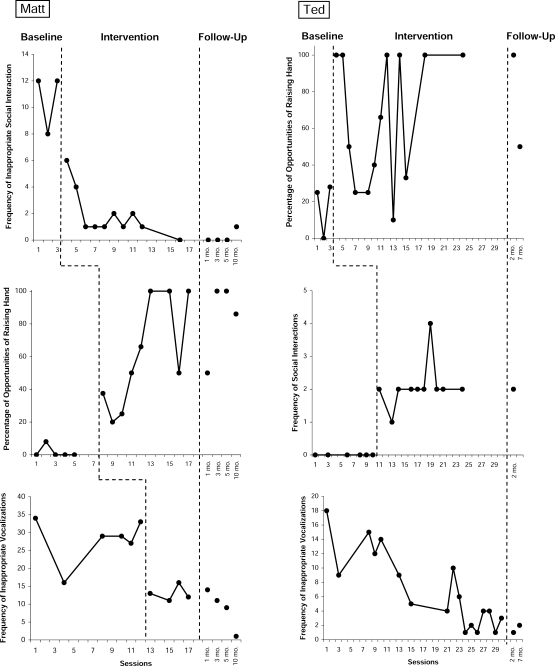

Figure 1 shows the frequency and percentage of opportunities for the three target behaviors for Matt and Ted during baseline, intervention, and follow-up phases. For Matt, introduction of the Social Stories intervention package resulted in (a) an immediate decrease in inappropriate social interaction behavior, (b) a progressive increase in hand raising, and (c) a reduction of his inappropriate vocalizations. For Ted, implementation of the intervention package led to (a) an increase in hand raising to higher and variable levels and (b) an increase in appropriate social initiations. Ted's inappropriate vocalizations decreased steadily throughout baseline, so the intervention was never introduced. Follow-up data for both participants indicated that positive behavior changes were maintained over time, with the final maintenance session conducted during a new school year in which both participants had been promoted to the first grade and had new teachers.

Figure 1.

Frequency and percentage of opportunities of target behaviors during baseline and intervention phases for Matt and Ted during 60-min observation sessions.

The results of the current study extend previous studies on Social Stories by extending the findings to inclusive classrooms and targeting appropriate classroom behaviors. The intervention did not require intensive supervision of the child's behavior or substantial time for implementation, making it suitable for regular education classroom settings. Although no comparative data of classmates' behavior are available, anecdotal evidence suggests that the participants performed similarly to their peers following the introduction of the intervention. For example, most students raised their hand regularly when the teacher asked a question and made a few social initiations during each circle time or center time.

The design of this study and the multicomponent nature of the intervention do not permit conclusions about the behavioral mechanisms that account for the effects of the intervention package or the importance of the stories themselves in changing behavior. It is possible that modeling and role play could have achieved the same effects without the stories. The advanced language capabilities of the participants in this study leave open the possibility that rule governance may account for the treatment effects (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001). If so, students without such verbal abilities may not benefit as readily from Social Stories or might require additional intervention components to achieve effects via different behavioral mechanisms (e.g., direct contingencies in the target setting).

Several future studies are needed to fully understand the impact of this popular educational intervention. Additional studies should be conducted in inclusive settings and should attempt to analyze the effects of the different intervention components by initially introducing Social Stories in isolation and introducing other components if needed. In addition, group-delivered Social Stories could target all students without singling out an individual child for special treatment. Increased teacher involvement is another possible target for research, with classroom teachers playing a role in the design and implementation of Social Stories studies (DiGennaro, Martens, & Kleinmann, 2007). Future studies should also address some of the measurement limitations evident in this experiment. For example, rate measures are preferable to the simple frequency counts reported here, and the ratio methods for measurement of interobserver agreement provide a liberal estimate of agreement compared to point-by-point methods. These issues are especially pertinent in light of the fact that data were discarded from this study because of low agreement.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the MA degree from the Department of Special Education of the University of Texas at Austin. We thank the parents, administrators, and teachers of the participants for their cooperation. The first author also thanks Ben Smith, Missy Olive, Lee Kern, Linda LeBlanc, Laura Peroutka, Eric Larsson, and Nicole Murillo.

References

- Delano M, Snell M.E. The effects of social stories on the social engagement of children with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2006;8:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- DiGennaro F.D, Martens B.K, Kleinmann A.E. A comparison of performance feedback procedures on teachers' treatment implementation integrity and students' inappropriate behavior in special education classrooms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:447–461. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.40-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryxell D, Kennedy C.H. Placement along the continuum of services and its impact on students' social relationships. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1995;20((4)):259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Gray C.A. Teaching children with autism to read social situations. In: Quill K.A, editor. Teaching children with autism. New York: Delmar; 1995. pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Gray C.A, Garand J.D. Social stories: Improving responses of students with autism with accurate social information. Focus on Autistic Behavior. 1993;8:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Green V.A, Pituch K.A, Itchon J, Choi A, O'Reilly M, Sigafoos J. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2006;27:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. 20 U.S.C. 1401 et seq 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer P.A, Simpson R.L, Myles B.S, Ganz J.B. The use of social stories as a preventative behavioral intervention in a home setting with a child with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Reynhout G, Carter M. Social StoriesTM for children with disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:445–469. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansosti F.J, Powell-Smith K.A. Using social stories to improve the social behavior of children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2006;8:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Swaggart B, Gangon E, Bock S.J, Earles T.L, Quinn C, Myles B.S, et al. Using social stories to teach social and behavioral skills to children with autism. Focus on Autistic Behavior. 1995;10:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann K.S, Goldstein H. Social stories, written text cues, and video feedback: Effects on social communication of children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:425–446. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]