According to the Compact Oxford English Dictionary, a palimpsest is “a parchment or other surface on which writing has been applied over earlier writing which has been erased.” Scholars are often able to decipher the earlier writing present on palimpsests by using chemical and imaging techniques. In a new study of a key enzyme that's involved in the biosynthesis of the guanine nucleotides, inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), Donghong Min and her colleagues uncovered an enzymatic palimpsest, an ancient chemical-bond–cleaving mechanism that lay obscured by the mechanism currently used by modern IMPDH.

Enzymes catalyze a mind-boggling variety of chemical reactions, from breaking down other proteins to regulating DNA transcription. Some enzymes are quite complex, and rather than increasing the rate of just one reaction, they can catalyze several very different reactions. Some multipurpose enzymes do this by tethering their molecular substrate to a flexible “linker” of amino acids, which then swings the substrate from one enzymatic active site to another. However, IMPDH catalyzes two very different chemical reactions at a single active site.

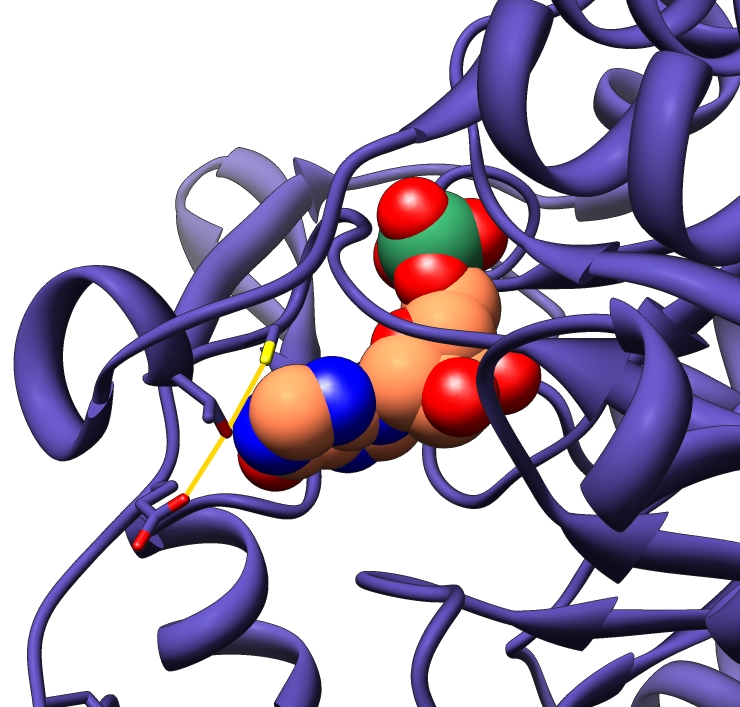

For the dehydrogenase reaction, IMPDH binds to the substrate inosine 5′-monophosphate (IMP) and to the cofactor NAD+ and transfers a proton and two electrons from IMP to NAD+. This produces NADH and the intermediate product E-XMP*, which is linked to the residue cysteine 319 (Cys319) on IMPDH. NADH departs, and a mobile protein flap of IMPDH that was open during the dehydrogenase reaction closes, carrying arginine 418 (Arg418) and tyrosine 419 (Tyr419) into the active site and converting the enzyme into a hydrolase (an enzyme that uses water to cleave a chemical bond). Previous research showed that the hydrolase reaction activates a water molecule by transferring one of its protons to Arg418. It then uses the activated water to break the chemical bond between Cys319 and E-XMP*, releasing XMP, which is the final product.

The multipurpose nature of IMPDH's active site poses some fascinating evolutionary questions: Since it's difficult to envision two sets of complex catalytic machinery evolving simultaneously during evolution, how might the conformational changes that take place in IMPDH's active site have arisen? And how might the ancestral enzyme have functioned?

To find out, the researchers ran computer simulation models using the known crystal structure of IMPDH from the protozoan Tritrichomonas foetus to investigate the mechanism of IMPDH's hydrolase function. They not only confirmed the existence of a previously proposed pathway, in which Arg418 accepts a proton from a water molecule, but they also identified second pathway, which uses threonine 321 (Thr321) for the same purpose. In this second, unexpected pathway, Thr321—which also plays a role in the dehydrogenase reaction—abstracts a proton from water while simultaneously transferring its own proton to glutamate 431 (Glu431). This finding was backed up by experimental results showing that, when Arg418 was replaced with an amino acid incapable of activating water, the Thr321/Glu431 pathway could account for most of the residual hydrolase activity.

Why would an enzyme have two pathways dedicated to the same task? The researchers believe that the Thr321 pathway may be an evolutionary vestige of the pathway used by the ancestral enzyme. This hypothesis was supported by phylogenetic analyses (which compare genetic sequences of different species to infer their evolutionary history) of IMPDH proteins from a variety of prokaryotic and eukaryotic species, as well as guanosine monophosphate reductase (GMPR), IMPDH's closest enzymatic relative. Although GMPR doesn't contain Arg418 or Tyr419 and its flap is truncated, amino acids Cys319, Thr321, and Glu431 are highly conserved and appear to interact in GMPR as they do in IMPDH. This fact suggests that the amino acids were almost certainly present in the ancestral enzyme, which was likely a dehydrogenase.

Although Glu431 is conserved among GMPRs and most prokaryotic IMPDHs, it is substituted with glutamine—an amino acid incapable of inactivating water—in the eukaryotic branch. The authors suggest that although the ancestral IMPDH/GMPR probably relied exclusively on the Thr321 pathway, once the more energetically favorable Arg418 pathway was established, the Thr321 pathway became expendable, and Glu431 was no longer constrained from mutating. However, if prokaryotic IMPDHs also use the Arg418 pathway, why is Glu431 so highly conserved among bacteria? The researchers suggest a couple of possibilities: First, the presence of the Thr321 pathway increases the rate at which IMPDH can convert IMP to GMP, which may be important for maintaining the large pool of guanine nucleotides necessary for rapidly reproducing bacteria. Second, the presence of Glu431 actually provides a 5–10-fold increase in resistance to mycophenolic acid, an antibiotic and immunosuppressive produced by the fungus Penicillium that specifically inhibits IMPDH. The researchers suggest that the presence in the environment of natural inhibitors like mycophenolic acid could have exerted evolutionary pressure on IMPDH, leading to the remarkable multifunctional nature of its active site. The presence of the Thr pathway could have allowed the enzyme to increase the productivity of its active site while protecting it from inhibition.

How does nature create an enzyme that can catalyze multiple chemical reactions in a single active site? Quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical simulations unexpectedly reveal a vestigial catalytic mechanism in IMPDH.