Abstract

The effect of oestradiol on the intact and castrated adult gerbil prostate was evaluated by focussing on stromal and epithelial disorders, and hormonal receptor immunoreactivity. The experimental animals were studied by histological, histochemical and immunohistochemical techniques, morphometric–stereological analysis and transmission electron microscopy. Epithelial alterations in the oestradiol-treated animals were frequent, with an increase in epithelial cell height, areas of intense dysplasia and hyperplasia and formation of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Another aspect that did not depend on the presence of testosterone was the arrangement of the fibrillar and non-fibrillar elements of the extracellular matrix among smooth muscle cells (SMC), suggesting a possible role of these cells in rearrangement and synthesis of these components, after oestrogenic treatment. In the castrated animals, an accumulation of extracellular matrix elements under the epithelium was evident, while in the intact animals the same compounds were dispersed and scarce. In the groups of intact and castrated animals, SMC and fibroblasts exhibited a secretory phenotype, which was accentuated after oestradiol administration. There was an increase of the immunoreactivity to α-oestrogen and androgen receptors in hyperplastic areas compared to normal epithelium, revealing the involvement of these steroid receptors in the hyperplasia and PIN development.

Keywords: castration, epithelium, gerbil, oestradiol, prostate, stroma

Oestrogens regulate the prostate development and function at several stages by indirect and direct mechanisms. Prostate growth, differentiation and functions are primarily controlled by androgens (ARs) but oestrogens modulate these effects in several ways. The most important routes of indirect oestrogen regulation are interference in AR production by repression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and direct effects on testis. Oestrogens also clearly have direct effects on the prostate, which may be elicited by external hormones or by oestradiol produced by local aromatization of testosterone (Härkönen & Mäkelä 2004). Oestrogen regulation has also been considered as one of the hormonal risk factors in association with development of benign prostate hyperplasia and prostate cancer (Bosland 2000; Henderson & Feigelson 2000). Exogenous oestrogens given during the perinatal period elicit abnormalities in prostate growth (Naslund & Coffey 1986), differentiation (Arai et al. 1977), function (Prins et al. 1993), AR metabolism (Santii et al. 1991), expression of AR receptors (Prins et al. 1993) and may lead to prostate cancer (Santii et al. 1990; Prins 1997).

Squamous metaplasia, dysplasia and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) are direct effects of oestrogen on the prostate induced by long-term exposure to high levels of exogenous or endogenous oestrogens (Risbridger et al. 2001; Scarano et al. 2004). For example, the squamous metaplasia of the prostate epithelium is characterized by the total replacement of the columnar secretory epithelium by layers of stratified squamous cells (Risbridger et al. 2001). The oestrogen hormone effects are mediated through α-oestrogen (ERα) signalling. Stromal–epithelial interactions and a requirement of both epithelial and stromal ERα contributed to elicit oestrogen-induced prostate normal epithelial growth and pathological disorders. Presumably, the development of prostate epithelial disorders involves the stimulation of epithelial proliferation mediated by stromal ERα and an epithelial differentiation mediated by epithelial ERαs (Cunha et al. 2002).

Previous studies have indicated that following the oestrogen administration the smooth muscle cells (SMC) increased in size and number, in the rat prostate (Thompson et al. 1979). Castrated and intact adult guinea-pig prostates showed an increased density and thickness of the collagen fibrils after oestradiol treatment (Neubauer & Mawhinney 1981; Mariotti & Mawhinney 1982; Scarano et al. 2005). These effects are directly associated with the presence of oestrogen receptors (α-ER) in the stroma and stimulation of the stromal cells by means of autocrine and paracrine mechanisms (Droller 1997).

The Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) has been recognized as experimentally useful in some biomedical sciences, such as immunology (Nawa et al. 1994), physiology (Nolan et al., 1990) and morphology (Pinheiro et al. 2003; Santos et al. 2003, 2006; Corradi et al. 2004; Custódio et al. 2004). More recently, the gerbil has also been suggested as a suitable model for studies on mammalian ageing and neoplasic prostate lesions (Pegorin de Campos et al. 2006; Campos et al. 2007). The gerbil prostate has compact lobes, somewhat similar to the human prostate, unlike rats and mice, which have distinct lobes (Pinheiro et al. 2003; Góes et al. 2006). Previous data from our laboratory have demonstrated that histological, histochemical and ultrastructural features of the adult gerbil ventral prostate are comparable to the human prostate. Also, we have observed that old gerbils (12 months) may spontaneously develop benign prostate hyperplasia, cancer and other prostate disorders, mainly in ventral prostate (Pegorin de Campos et al. 2006).

Morphological studies on the oestrogenic effects in the prostate gland had been performed in many commonly used experimental animals, including mouse (Triche & Harkin 1971), rat (Kjaerheim et al. 1974; Thompson et al. 1979) and guinea-pig (Neubauer & Mawhinney 1981; Scarano et al. 2005), however, these studies focus on more general aspects of the gland, related to the epithelial comportment at most times and they used more simple morphological methodologies.

In the present study, we evaluated in intact and castrated gerbils the influence of oestrogen in epithelial and stromal prostate compartments to establish the effects of this hormone in this new animal model and to compare the results obtained in other experimental models.

Material and methods

Animals and hormone treatments

Twenty adult (120 days) male M. unguiculatus gerbils were randomly divided into four experimental groups: intact control (C), intact oestradiol-treated (E), castrated (Ca) and castrated oestradiol-treated (CaE). The Ca and CaE groups were submitted to bilateral orchiectomy by abdominal surgical incision. The deferent ducts were sectioned and tied and the two testes were removed by abdominal cavity. After the surgery, the animals of these groups were placed in individual boxes and submitted to the treatments after 7 days. The E and CaE groups received, during 21 days, alternately, subcutaneous injections of oestradiol benzoate (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) diluted in corn oil (10 mg/ml), at a dose of 0.1 ml/application/animal (1 mg/application), while C and Ca groups received only vehicle.

After 21 days of treatment, the animals were lightly anesthetized by CO2 inhalation, weighed and immediately decapitated for blood collection. The ventral prostate was removed, weighed in an analytical balance, and immediately processed for light and electron microscopic studies.

Animal handling and experiments were carried out according to the ethical guidelines of the São Paulo State University (Unesp), following the ‘Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’. The number of individuals employed in this work was justified by the large number of analytical procedures employed.

Serum hormonal levels

Circulating serum testosterone levels were determined by immunochemical assays. After 21 days of treatment, blood was collected by decapitation from the ruptured cervical vessels and the serum was separated by centrifugation (300 g) and stored at −20 °C for subsequent hormone assay. The determination of serum testosterone levels was performed by luminescence immunoassay (mouse anti-testosterone antibodies; Johnson & Johnson, Orthoclinical Diagnostics Division, Amersham, UK) in an automatic analyzer: Vitros-ECi (Johnson & Johnson, Orthoclinical Diagnostics Division, USA) for ultrasensitive chemiluminescence detection. The intra-assay and inter-assay variation were 4.6% and 4.3% respectively. The tests are linear from 0 to 30 ng/ml (detection level).

Histochemistry

Ventral prostates of the four experimental groups were cut into fragments of 5 μm, selected from the gland distal segment. Same ventral prostatic fragments samples were separated from these to be proceeded for transmission electron microscopy. The remaining fragments were immediately fixed by immersion in Karnovsky’s fixative (0.1 m Sörensën phosphate buffer pH 7.2 containing 5% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde) for 24 h. Fixed tissue samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and embedded in glycol methacrylate resin (Leica historesin embedding kit). Histological sections (3 μm) were subjected to haematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining for general studies, to Gömöri’s reticulin (Gömöri 1937) staining for collagen and reticular fibres analyses and to the Feulgen reaction (Mello & Vidal 1980) for nuclear study. Histopathological analyses were performed on Zeiss-Jenaval or Olympus photomicroscopes, and the microscopic fields were digitized using the software Image-Pro®Plus version 4.5 for Windows™ software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Morphometric and stereological analysis

Using an imaging analysis system (Image-Pro®Plus version 4.5 for Windows™ software), H&E and Feulgen sections were studied. Randomly H&E images of 100 histological fields per experimental group were captured and analysed by the stereological method, such that histological fragments of all animals were evaluated equally (20 per animal). Stereological analyses were obtained by Weibel’s multipurpose graticulate, with 120 points and 60 test lines (Weibel 1979) to compare the relative volume among the prostate components (epithelium, stroma and acinar lumen) in the experimental groups.

Morphometric analysis was performed to evaluate epithelial height, SMC layer thickness surrounding the acini, and nuclear area and nuclear perimeter (kariometry) of the secretory epithelial cells. For this comparative study, 200 random group measures in normal acini (free of hyperplasic processes) were performed for each parameter.

To quantify the density of cells positive for ERα and AR, cells from normal and hyperplasic epithelial regions (if present) were selected and analysed per experimental animal (200/each region) totalling 1000 cells per group/region (n = 5), and the percentage of cells negative and positive for hormonal receptor immunoreactivity were estimated.

Statistical analysis

The effects of oestradiol on gerbil ventral prostate were evaluated by analysing mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical analysis was performed with the statistica 6.0 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). The anova hypothesis test and Tukey honest significant difference (HSD) test were employed and P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Transmission electron microscopy

Ventral prostates fragments of the experimental groups were processed for transmission electron microscopy as described previously (De Carvalho et al. 1994), employing the fixation procedure of Cotta-Pereira et al. (1976). Briefly, ventral prostate fragments, selected from the distal segment of the gland, were fixed in 0.25% tannic acid plus 3% glutaraldehyde in Millonig’s buffer, dehydrated in acetone and embedded in Araldite resin. After selecting the area of interest in the distal region of the prostate by trimming of the material using a glass knife, silver sections (50–75 nm) obtained with a diamond knife were collected and stained by uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Observation and electron micrographs were made with a LEO–Zeiss 906 transmission electron microscope (Leo-Zeiss, Cambridge, UK).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Androgen (SC-816, 1:100 dilution; rabbit polyclonal antibody), ERα (SC-542, 1:50 dilution; rabbit polyclonal antibody) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and chondroitin sulphate-anti-SC56 (Sigma Chemical Co.) were used for IHC. The immunohistochemical reaction was performed using the avidin–biotin complex (ABC) kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For the immunohistochemical technique, ventral prostate fragments selected from the gland distal segment were fixed in 10% formaldehyde, dehydrated in alcohol and embedded in paraplast. The sections (4 μm) were dewaxed and then rehydrated in graded alcohol and distilled water. Antigenic recuperation was realized in citrate buffer at high temperature (100 °C) for 45 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 45 min, followed by a quick rinse in distilled water and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Sections were incubated with normal goat and primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. The slides were then incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit at 37 °C followed by peroxidase-conjugated ABCs and diaminobenzidine (DAB). The sections were then counterstained with Harris’s haematoxylin. For negative control, the primary antibody was replaced with the corresponding normal isotype serum.

Results

Structure and ultrastructure

C group

The prostate of the intact adult gerbil presented glandular units, with simple cylindrical epithelium, adjacent to and a fine smooth muscle, which delimited the lumen of the gland (Figure 1a,b). Among the acini was noted a dispersed and loose connective vascularized tissue. The epithelial cells of the gland possessed evident secretory characteristics, revealed by the presence of the secretion organelles above the nucleus (Figure 13). Adjacent to the epithelium and interspersed with the SMC, there was scanty extracellular matrix fibres (Figures 1b, 5a and 14). Alteration in body weight was not verified among the experimental groups (Table 1).

Figures 1–4.

Histological sections stained by haematoxylin–eosin. 1(a,b): Intact control group (C) – 1(a) general aspect of the prostate acinus; 1(b) detail of the epithelium (e) and smooth muscle cells layer (SMC) of adult prostate acinus. 2(a–d): Oestradiol-treated group (E) – 2(a) general aspect of a prostate acinus with high epithelium and dysplasia; 2(b) cells dislocated to the apical regions (arrow), simulating a possible detachment and secretory granules in the lumen were observed; 2(c) detail of the transition epithelium-stroma; arrow point the subepithelial stroma and the fusiforms smooth muscle cells. Between the SMC conjunctive tissue was observed; 2(d) a high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). 3(a,b): Castrated group (Ca) – 3(a) prostate acinus with a low epithelium (ep), SMC and evident subepithelial conjunctive stroma (arrow); 3(b) detail of the prostate acinus where a prominent subepithelial conjunctive stroma (arrow) and SMC with irregular aspect were noticed. 4(a–d): Oestradiol-treated castrated group (CaE) – 4(a) prostate acinus showing the epithelial enfolding (ep). Arrow points to subepithelial connective stroma; 4(b) arrows point to basal membrane with sinuous aspect (e) abundant conjunctive stroma. Arrow head show the SMC with irregular spine-like cytoplasmic projections. Notice the high epithelial cells (ep); 4(c) presence of PIN and abundant subepithelial stroma (arrow) and a substantial layer of SMC; 4(d) detail of epithelium-stroma transition showing the subepithelial connective tissue (arrow), the SMC and the dysplasic epithelium (ep).

Figures 13–22.

Transmission electron microscopy: ultrastructural aspects – (13) epithelial cells (ep) from intact control prostate. Arrow points to secretion organelles, bar = 2.60 μm; (14) epithelium-stroma transition. Arrow point to basal laminae; in the stroma the smooth muscle cells (SMC), fibroblasts (fib) and scarce collagen fibres (col); intact control group, bar = 0.94 μm; (15) abundance of bunches of collagen fibres (col) in the subepithelial stroma and fibroblasts (fib), epithelium (ep), Ca group, bar = 1.56 μm; (16) detail of the activated fibroblast (fib) with dilated endoplasmic reticulum cisternae (arrow), Ca group, bar = 0.72 μm; (17) sinuous aspect of basal laminae (bl) with collagen deposition (col) in the subepithelial stroma, Ca group, bar = 0.72 μm; (18) irregular arrangement of SMC and collagen fibres (col), Ca group, bar = 1.56 μm; (19) epithelial cells from oestradiol-treated castrated prostate, bar = 2.60 μm; (20) PIN in oestradiol-treated prostate. The epithelial stratification with loose chromatin and conspicuous nucleolus were used here as morphological parameters for PIN diagnosis, bar = 3.36 μm; (21) detail of an epithelial cell from oestradiol-treated prostate, showing the circular endoplasmic reticulum, bar = 0.56 μm; (22) a high epithelial cell from oestradiol-treated group. The arrow points to dilated cisternae, bar = 2.01 μm. n, nuclei; ep, epithelium; st, stroma; SMC, smooth muscle cells.

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis from experimental groups

| Experimental groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | E | Ca | CaE | |

| Morphometry (μm) | ||||

| Epithelium height | 13.08a ± 2.14 | 22.32b ± 4.80 | 10.16a ± 2.73 | 19.42b ± 3.24 |

| SMC layer thickness | 8.51a ± 1.85 | 11.87b ± 2.00 | 12.38b ± 2.43 | 11.75b ± 2.48 |

| Kariometry of secretory cells | ||||

| Nuclear area (μm2) | 23.15a ± 3.84 | 30.06b ± 4.27 | 21.15a ± 4.51 | 27.80b ± 4.96 |

| Nuclear perimeter (μm) | 21.27a ± 2.80 | 22.96a ± 3.20 | 19.61a ± 2.61 | 21.94a ± 2.74 |

| Relative volume of tissue components (%) | ||||

| Epithelium | 19.84a ± 2.64 | 28.15b ± 2.66 | 17.87a ± 4.64 | 33.90b ± 12.47 |

| Stroma | 38.77a ± 10.04 | 38.42a ± 5.34 | 50.13b ± 7.85 | 41.20a ± 10.25 |

| Lumen | 43.89a ± 10.52 | 33.46b ± 6.19 | 32.0b ± 11.99 | 24.90c ± 13.52 |

| Body weight (g) | 80.0 ± 8.7 | 79.5 ± 7.0 | 78.8 ± 8.5 | 81.2 ± 6.5 |

| Prostate weight (g) | 1.04a ± 0.25 | 0.55b ± 0.16 | 0.64b ± 0.11 | 0.76b ± 0.17 |

| Relative prostate weight (g prostate/g body weight)2 | 0.013a ± 0.002 | 0.007b ± 0.001 | 0.008b ± 0.001 | 0.009b ± 0.001 |

Statistical analyses based on anova and Tukey tests. Lower case letters

indicate statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05).

C, control; Ca, castrated; E, oestradiol-treated; CaE, catrated oestradiol-treated animals).

E group

In E animals, absolute and relative weights of the prostatic gland decreased when compared with the C group (Table 1). The acinar lumen was also decreased. However, increases in the epithelial height and in the smooth muscle layer were noted (Figure 2c). The nuclear area was also statistically significantly increased, and the nuclear perimeter, although not statistically significant, was also increased (Table 1). Ultrastructurally, the epithelial secretory cells appeared with a large number of dilated cisternae (Figure 22) and with circular endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 21). Areas containing frequent hyperplasia and dysplasia presented elongated epithelial cells with nuclei of different sizes and heights (Figure 2a,b). In the epithelial compartment, due to intense dysplasia, areas with cells dislocated to the apical regions were noted, implying a possible detachment (Figure 2b). In some acini, the presence of PIN was documented at the light microscopy (Figure 2d). At the transmission electron microscopy the epithelial stratification with loose chromatin and conspicuous nucleolus were observed (Figure 20). These morphological parameters were considered here as PIN lesions. Morphologically, the stroma of the E group presented less elongated and more fusiform SMC compared with the C group (Figure 2c). The ultrastructure showed hypertrophic SMC with well-developed secretory organelles (Figure 24). Besides, fibroblasts activated with large quantities of endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex were observed (Figure 26). Extracellular matrix compounds appeared in an expressive feature, with an increase in elastic and collagen fibres mainly adjacent to SMC. An intimate relationship was observed between synthesized fibrils and stromal cells, including the formation of cytoplasmic compartments through elongation of fibroblasts and SMC (Figures 6a, 29 and 30). Furthermore, non-fibrillar components of chondroitin sulphate had a predominantly inter-SMC demarcation and distribution (Figure 6b).

Figures 23–30.

Transmission electron microscopy – ultrastructural aspects –(23) general aspect of stromal compartment showing the SMC with ER prominent in oestradiol-treated castrated prostate, bar = 1.21 μm; (24) the SMC with dilated Golgi apparatus cisternae (arrow), E group, bar = 0.56 μm; (25) the SMC with irregular spine-like cytoplasmic projections surrounded by collagen fibres (col), CaE group, bar = 1.21 μm; (26) the activated fibroblast replete of ER and with dilated Golgi apparatus cisternae (Ga). Notice the prominent nucleolus, E group, bar = 1.21 μm; (27 and 28) detail of SMC prolongations and collagen (col) arrangement between them. elastic fibers (el), CaE group; (27) bar = 1.56 μm; (28) bar = 1.21 μm; (29 and 30) detail of SMC showing the intimate contact with elastic fibres (el) in cytoplasmic prolongations and collagen fibres (col), E group; (29) bar = 0.72 μm; (30) bar = 0.94 μm. n, nuclei; nu, nucleolus.

Figures 5–8.

5(a), 6(a), 7(a) and 8(a) Histological sections stained by Gömöri’s reticulin; 5(b), 6(b), 7(b) and 8(b): histological sections submitted to chondroitin sulphate IHC – 5(a,b) intact control group; 6(a,b) oestradiol-treated group; 7(a,b) castrated group; 8(a,b) oestradiol-treated castrated group. Arrows point positive demarcation to reticulin fibres and chondroitin sulphate respectively. *collagen fibres; ep, epithelium; l, lumen.

Ca group

The prostate gland of the Ca group showed acini with cubic/short cylindrical epithelium, surrounded by a thick connective tissue and SMC concentrically arranged (Figure 3a,b). The short epithelial cells assumed, a flat aspect (Figure 3a,b), increasing the nucleus–cytoplasm ratio. An irregular and wavy basal membrane was noted in most of its extension, forming a semi-pleated arrangement (Figures 3b, 7a, 15 and 17). Adjacent to the epithelium and filling out the irregularities of the basal membrane, a thick connective subepithelial tissue was observed (Figures 3b, 7a, 15 and 17). This connective stroma had abundant extracellular matrix fibres, mainly collagen (Figures 7a, 15 and 17) and reticular ones (Figure 7a). Strongly immunoreactive non-fibrillar components, such as chondroitin sulphate revealed by IHC, were also noted in this subepithelial region (Figure 7b). It is interesting that in this experimental group the extracellular matrix components, despite being markedly distributed in the periacinar region, were concentrated mainly in the adjacent area to the basal lamina (Figures 7a, 15 and 17) where fibroblasts presented high synthetic activity (Figure 16). In the concentrically smooth muscle arranged around acini, the SMC formed irregular layers (Figure 3a) among the extracellular matrix fibres (Figure 3b) of the subepithelial stroma. These cells assume a spinous and irregular phenotype (Figures 3b and 18), different from the elongated fusiform aspect usually found in the layers of the C group prostates (Figure 3a).

CaE group

After oestradiol administration for 21 days to castrated animals, we observed an increase in the amount of epithelium, besides a decrease in the amount of the lumen, when compared with the Ca group (Table 1). Significant alterations in the secretory activity of CaE prostates were observed. The epithelium was predominantly cylindrical, which culminated in an increase in the height of the epithelium (Table 1). An increase in the nuclear area of secretory epithelial cells was also observed (Table 1). After the treatment, dysplastic areas with an increase in cellular size were observed (Figure 4b,d). Besides, there were areas with occurrence of PIN characterized by agglomerated epithelial cells with heterogeneous phenotypes (Figure 4c). Yet the basal membrane was observed, as found in the Ca group, with a wavy and semi-pleated arrangement (Figures 4b,d and 8a). Accumulation of collagen fibres (Figure 8a) was observed adjacent to the epithelium, accompanying the confluences of the basal membrane and interspersed with SMC. Apparently, a preferential deposition of collagen fibres occurred among the SMC in this experimental group (Figures 8a, 27 and 28). Besides, there was also a discreet increase in the fibrous bunches that permeate SMC and in chondroitin sulphate (Figure 8b). The arrangement of the SMC resembles that observed in the Ca group because they assumed an elongated fusiform phenotype, forming concentric bunches of fibres (Figure 4a), and irregular spine-like cytoplasmic projections, unwrapped by the extracellular matrix (Figures 4b and 25).

Immunohistochemistry

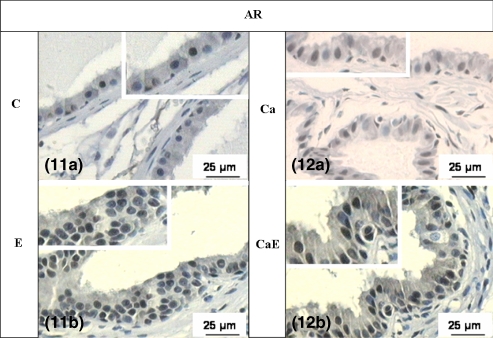

The expression of AR and ERα, in all experimental groups, presented positive and negative reaction in the epithelial and stromal cells (Figures 9a, 10a, 11a and 12a). The immunoreactivity was heterogeneous, demonstrating that some cellular clones are more sensitive to the action of those hormones. After oestradiol treatment, the density of ERα and AR positive cells was greater in hyperplastic and dysplastic epithelial areas (Figures 9b,c, 10b,c, 11b and 12b; Table 2), when compared with areas in normal epithelium (Table 2).

Figures 9 and 10.

Histological sections submitted to ERα IHC – 9(a) intact control group; 9(b–c) oestradiol-treated group; 10(a) castrated group; 10(b–c) oestradiol-treated castrated group. Brown stain means positive demarcation.

Figures 11 and 12.

Histological sections submitted to AR IHC – 11(a) intact control group; 11(b) oestradiol-treated group; 12(a) castrated group; 12(b) oestradiol-treated castrated group. Brown stain means positive demarcation.

Table 2.

Relative frequencies (%) of AR and ERα positive cells obtained by anti-AR and anti-ERα immunohistochemical method

| Experimental groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | E | Ca | CaE | ||

| AR positive cells | |||||

| Normal epithelium | 49.5 ± 4.5 | 52.2 ± 5.1 | 45.8 ± 3.9 | 51.5 ± 4.8 | |

| Hyperplasic epithelium | – | 72.4* ± 6.0 | 55.5 ± 5.9 | 77.2* ± 6.5 | |

| ERα positive cells | |||||

| Normal epithelium | 35.2 ± 3.2 | 42.5 ± 5.2 | 36.2 ± 4.8 | 39.5 ± 3.5 | |

| Hyperplasic epithelium | – | 71.5* ± 7.2 | 37.2 ± 4.5 | 69.8* ± 7.2 | |

Statistical analyses based on Tukey test.

Statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05).

The IHC assays for the demarcation of chondroitin sulphate, a glycosaminoglycan of the stromal extracellular matrix, in the C group (Figures 7 and 8) demonstrated a diffuse demarcation, with moderate intensity of reaction, in the areas adjacent to the epithelial base and SMC. Besides, in some acini the specific demarcation in the epithelial cells, especially in the Golgi complex, was observed due to the production of sulphated residues. Immunoreactivity of chondroitin sulphate in E and CaE groups (Figures 6b and 8b) showed localization less diffuse than in C and Ca groups, with strong reaction mainly in the areas adjacent to the basal lamina and among the SMC. A preferential deposition of chondroitin occurred among the SMC (Figures 6b and 8b), what was similar to the collagen fibres in the E and CaE groups.

Hormonal levels

Serum testosterone levels varied significantly (P ≤ 0.05) between C, E, Ca and CaE groups, which confirmed an expected decrease in hormonal concentrations in each experimental group in comparison to the intact C group (Figure 31).

Figure 31.

Mean ± SD values of serum testosterone levels (ng/ml) from experimental groups (C, control; Ca, castrated; E, oestradiol-treated; CaE, catrated oestradiol-treated animals). Statistical analysis based on anova and Tukey tests. Different superscript letters (a, b) indicate statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Understanding the role of oestrogens in the prostate and how it acts to modulate prostate development growth and disease is of immense interest. In this work, we investigate the influence of oestradiol benzoate in the ventral prostatic stroma and epithelium and demonstrated the direct activity of oestrogens on stromal cells and extracellular elements resulting in compositional changes in the stromal compartment.

Oestrogen has been implicated in the pathogenesis of prostate diseases by their direct and indirect effects. Prominent among the direct effects is the anti-androgenic action caused by repression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and direct effect on the testis. Oestrogens also clearly have direct effect on the prostate, which may be elicited by external hormone or by oestradiol produced by local aromatization of testosterone (Härkönen & Mäkelä 2004).

The effects of orchiectomy have been studied under various aspects in several experimental animals, mainly as a model of studying the rearrangement of extracellular matrix architecture (Carvalho & Line 1996; Vilamaior et al. 2000; Antonioli et al. 2004). Along with these studies, researches using oestrogen have been accomplished to define its role more precisely in hypoandrogenic prostate tissue (Tam & Wong 1991; Pelletier 2002) and in physiological conditions (Scarano et al. 2004).

According to Pegorin de Campos et al. (2006) and Scarano et al. (2006), the prostatic acinus of intact adult gerbil presents simple cylindrical epithelium, with the presence of secretion granules in the lumen, and prominent chromophobes areas adjacent to the nucleus, identified as Golgi apparatus.

Our results showed that the epithelium of the Ca group was found short and cubic, with scarce secretion vesicles in the luminal border and relatively high nucleus–cytoplasm ratio. There was no significant decrease in the height of the epithelium in Ca when compared with C, but it was an evident morphological and quantitative tendency to this. This regression of the prostate was frequent in androgenic ablation, which agrees with the data obtained previously by Pelletier (2002) with mice and after experimental chemical castration with guinea-pig (Cordeiro et al. 2004) and also with adult gerbil (Corradi et al. 2004).

The surgical castration process also reveals an increase in stromal compartment, when comparing with intact animals (Vilamaior et al. 2000). In the Ca group, a great amount of extracellular matrix fibres was observed in the subepithelial stroma, in addition to structural modifications of SMC. According to Vilamaior et al. (2000), the androgenic deficiency promotes a rearrangement of extracellular matrix fibres, and possibly, synthesis of constituents of this matrix. This rearrangement occurs probably due to alterations in SMC synthetic capacity, which might play a more synthetic, than contractile, role.

Horsfall et al. (1994) demonstrated in guinea-pigs that during the ageing process, SMC increases its synthetic capacity, thus modifying its morphological structure. Similarly, experimental studies using orchiectomy and chemical castration showed an increase in extracellular matrix components allied with phenotypic alterations of SMC that started to exhibit an irregular and spinous arrangement (Antonioli et al. 2004; Corradi et al. 2004). The phenotypic transition of SMC, in this case, involves a process denominated dedifferentiation previously described in androgenic blockade processes (Corradi et al. 2004) and after oestrogen treatments (Zhao et al. 1992), where the muscle cells assume an essentially secretory phenotype (Vilamaior et al. 2005).

Alterations in prostatic nuclei structure during the castration, hormonal recovering and in prostatic lesions by quantitative nuclear morphometry (kariometry) may be an excellent histopathological tool for microscopic diagnosis. The kariometric data revealed that even the E and CaE groups had increased the nuclear area, besides an increase of the epithelial height, as was previously observed by Scarano et al. (2004) and could be related with increase of the synthetic and/or metabolic cell activity. Nuclear parameters can be efficient to compare some epithelial modifications (Martínez-Jabaloyas et al. 2002; Taboga et al. 2003), but it is not effective in diagnosis of prostate lesions and should be interpreted together with other results. Recent research employing 40 quantitative nuclear morphometric parameters suggested with those parameters as a new biomarker for prostatic cancer and histopathological gradation (Veltri et al. 2007). Furthermore, dysplastic processes with alteration of the epithelial structure and hyperplasia in determinate regions of the ventral prostate contributed to the relative increase of the epithelium verified in these animals. Scarano et al. (2004) described intraepithelial alterations in guinea-pigs treated with oestradiol, and observed the occurrence of PINs with relative increase in the epithelial compartment.

The histopathological classification of the epithelial alterations in this work were based to the model proposed by Campos et al. (2007) to the prostate lesions in the aged gerbil that classify and compare normal epithelium, hyperplasic epithelium, PIN and adenocarcinoma. According to Campos et al. (2007) and Bar Harbor Classification System for the mouse prostate, developed by National Cancer Institute Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium Prostate Steering Committee (Shappell et al. 2004), PIN was characterized by agglomerations of heterogeneous epithelial cells with probable atypical function and cytoplasmic projections can extend towards the extracellular matrix, compressing the basement membrane.

The cytoplasm of epithelial cells presented dilated endomembranes in some areas and circular endoplasmic reticulum, in E group, was also noted. This circular structure had been described by Kjaerheim et al. (1974) in castrated animals, where reduction was observed in the size of synthesis organelles and number of ribosomes.

Receptors specific for oestrogen were identified in both the epithelium and stroma (Prins & Birch 1997). Experimental studies have demonstrated that oestrogen is involved in the induction of premalignant and malignant alterations (Weihua et al. 2001; Scarano et al. 2004). According to Cunha et al. (2002), the epithelial alterations, such as squamous metaplasia, require oestrogen action through stromal ERα, in a paracrine mechanism, as well as by the ERα epithelial route. Such results concur with the data obtained in this study, where higher density of ERα-positive cells was found in hyperplasic areas, showing that oestrogen has affected routes that do not depend on androgenic levels. In spite of that, it is important to emphasize that the treatments with oestradiol exhibited larger AR expression. According to Droller (1997), oestrogen induces stromal fibroblasts to express receptors for both epidermal growth factor (EGF-R) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF-R), besides increasing the level of AR. The androgenic effects on normal epithelium are explained by paracrine factors produced by stromal AR-positive cells (Cunha et al. 2002). However, androgenic regulation of prostate epithelial cells during malignant transformation of prostate epithelial cells appears to involve conversion from a paracrine to an autocrine mechanism of AR-stimulated growth (Gao et al. 2001). Perhaps this mechanism of autocrine performance explains the increased density of AR-positive cells in the hyperplasic areas and in PINs.

Droller (1997) identified ER in stromal cells. According to this author, oestrogen induces receptor expression for specific growth factors, increasing the synthetic activity of those cells and also of the SMC. This incentive may be responsible for the increase in synthesis of extracellular-matrix fibres and for the apparent increase in the stromal compartment of the oestrogenized animals, observed in both E and CaE groups. However the increase in synthetic capacity may be related to the sensitive decrease in intra-prostate androgenic levels, which was provoked by the oestrogenic supplementation previously described by Härkönen and Mäkelä (2004).

Despite verifying that castration increased the stromal compartment as much as oestrogenic treatments and that both situations have stimulated the synthesis of fibrillar and non-fibrillar extracellular matrix components, it should be emphasized that their distributions were different, castration promoted a preferential deposition of connective tissue in the sub-epithelial area while oestrogenic treatments caused an accumulation of connective tissue around the SMC. This observation exposes a possible role of SMC in the arrangement of the constituents of the extracellular matrix during the rearrangement process caused by oestradiol (Scarano et al. 2005) and in BPH (Cardoso et al. 2004). Besides, it was observed that in the intact animals treated with oestradiol, the frequency of elastic fibres was higher, in agreement with the data obtained previously by Scarano et al. 2005.

This work revealed two important data: one that the gerbil is a good experimental model to study prostatic diseases of hormonal aetiology and that oestradiol has direct effects on gerbil prostate, independently of the androgenic levels. Such effects are represented mainly by the proliferative and dysplastic epithelial alterations and by the architecture of the extracellular matrix constituents. This new microenvironment may be achieved possibly by the fundamental role of SMC in the post-treatment arrangement. Besides, hormonal receptors seem to have a fundamental role in the expression of altered epithelial phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the thesis presented by WRS to the Institute of Biology, UNICAMP, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a PhD degree, and was supported by grants from the Brazilian agencies CNPq – Brazilian National Research and Development Council (fellowship to WRS and SRT – Proc. Nr. 301111/2005-7) and FAPESP – Sao Paulo State Research Foundation (Proc. Nr. 02/12942-6 and fellowship to DES and SGPC). The authors wish to thank Mrs Rosana S. Sousa MS and Mr Luis Roberto Faleiros Jr for their technical assistance, as well as all other researchers at the Microscopy and Microanalysis Laboratory. Comments provided by the anonymous referees helped improve our original manuscript. Special acknowledgement is also due to Mr James Welsh and Mr Davi A. Pontes for English language revision of this paper.

References

- Antonioli E, Della-Colleta HHM, Carvalho HF. Smooth muscle cells behavior in the ventral prostate of catrated rats. J. Androl. 2004;25:50–56. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y, Suzuki Y, Nishizuka Y. Hyperplastic and metaplastic lesions in the reproductive tract of male rats induced by neonatal treatment with diethylstilbestrol. Virchows Arch. 1977;376:21–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00433082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosland MC. The role of steroid hormones in prostate carcinogenesis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2000;27:39–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos SGP, Zanetoni C, Scarano WR, Vilamaior PSL, Taboga SR. Age-related histopathological lesions in the Mongolian gerbil ventral prostate as a good model for studies of spontaneous hormone-related disorders. Int. J. Exp. Path. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00550.x. EPub ahead of print; doi 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso LEM, Falcao PG, Sampaio FJB. Increased and localized accumulation of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the hyperplastic human prostate. BJU Int. 2004;93:532–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2003.04688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho HF, Line SRP. Basement membrane associated changes in the rat ventral prostate following castration. Cell Biol. Int. 1996;20:809–819. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro RS, Scarano WR, Góes RM, Taboga SR. Tissular alterations in the guinea pig prostate following antiandrogen flutamide therapy. BioCell. 2004;28:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corradi LS, Góes RM, Carvalho HF, Taboga SR. Inhibition of 5-alpha-reductase activity induces remodeling and smooth muscle dedifferentiation in adult gerbil ventral prostate. Differentiation. 2004;72:198–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07205004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta-Pereira G, Rodrigo FG, David-Ferreira JF. The use of tannic acid-glutaraldehyde in the study of elastic related fibers. Stain Technol. 1976;51:7–11. doi: 10.3109/10520297609116662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha GR, Hayward SW, Wang YZ. Role of stroma in carcinogenesis of the prostate. Differentiation. 2002;70:473–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custódio AM, Góes RM, Taboga SR. Acid phosphatase activity in gerbil prostate: comparative study in male and female during postnatal development. Cell Biol. Int. 2004;28:335–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho HF, Lino Neto J, Taboga SR. Microfibrils: neglected components of pressure-bearing tendons. Ann. Anat. 1994;176:155–159. doi: 10.1016/s0940-9602(11)80441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droller MJ. Medical approaches in the management of prostate disease. Br. J. Urol. 1997;79(Suppl. 2):42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1997.tb16920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Arnold JT, Isaacs JT. Conversion from a paracrine to an autocrine mechanism of androgen-stimulated growth during malignant transformation of prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5038–5044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Góes RM, Zanetoni C, Tomiosso TK, Ribeiro DL, Taboga SR. Histological response on dorsal and ventral gerbil prostate lobes induced by different testosterone withdrawal procedures. Micron. 2006 doi 10.1016/j.micron.2006.06.016. [Google Scholar]

- Gömöri G. Silver impregnation for reticulin in paraffin sections. Am. J. Pathol. 1937;13:993–1002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härkönen PL, Mäkelä SI. Role of estrogen in development of prostate cancer. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;92:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson BE, Feigelson HS. Hormonal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:427–433. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall DJ, Mayne K, Ricciardelli C, et al. Age-related in guinea pig prostate stroma. Lab. Invest. 1994;70:753–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerheim A, Dahl E, Tveter KJ. The ultrastructure of accesory sex organs of the male rat: effects of estrogen on the prostate. Lab. Invest. 1974;31:391–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti A, Mawhinney M. The hormonal maintenance and restoration of guinea pig seminal vesicle fibromuscular stroma. J. Urol. 1982;128:852–857. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Jabaloyas JM, Ruiz-Cerdá JL, Hernández M, Jiménez-Cruz F. Prognostic value of DNA ploidy and nuclear morphometry in prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation. Urology. 2002;59:715–720. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01530-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello MLS, Vidal BC. Práticas de Biologia Celular. São Paulo: Edgard Blücher-Funamp; 1980. pp. 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Naslund MJ, Coffey DS. The differential effects of neonatal androgen, estrogen and progesterone on adult rat prostate growth. J. Urol. 1986;136:1136–1140. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawa Y, Horii Y, Okada M, Arizono N. Histochemical and cytochemical characterization of mucosal and connective tissue mast cells of Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1994;104:249–254. doi: 10.1159/000236673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer B, Mawhinney M. Actions of androgen and estrogen on guinea pig seminal vesicle epithelium and muscle. Endocrinology. 1981;108:680–687. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-2-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan CC, Brown AW, Cavanagh JB. Regional variations in nerve cell responses to the trimethiltin intoxication in Mongolian gerbil. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 1990;81:204–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00334509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegorin de Campos SG, Zanetoni C, Goes RM, Taboga SR. Biological behavior of the gerbil ventral prostate in three phases of postnatal development. Anat. Rec. 2006;288:723–733. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier G. Effects of estradiol on prostate epithelial cells in the castrated rat. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2002;50:1517–1523. doi: 10.1177/002215540205001112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro PFF, Almeida CCD, Segatelli TM, Martinez M, Padovani CR, Martinez FE. Structure of the pelvic and penile urethra-relationship with the ducts of the sex accessory glands of the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) J. Anat. 2003;202:431–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins GS. Development estrogenization of the prostate gland. In: Naz RK, editor. Prostate: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Boca Raton, FL: CRC press; 1997. pp. 245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Prins GS, Birch L. Neonatal estrogen exposure up-regulate estrogen receptor expression in the developing and adult rat prostate lobes. Endocrinology. 1997;139:874–883. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins GS, Hoodham C, Lepinske M, Birtch L. Effects neonatal estrogen on prostate secretory genes and their correlation with androgen receptor expression in the separate prostate lobes of the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2387–2398. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8504743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risbridger G, Wang H, Young P, et al. Evidence that epithelial and mesenchymal estrogen receptor- alpha mediates effects of estrogen on prostate epithelium. Dev. Biol. 2001;229:432–442. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santii R, Pilkkanen L, Newbold RR, Mclachlan JA. Development oestrogenization and prostate neoplasia. Int. J. Androl. 1990;13:77–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1990.tb00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santii R, Newbold RR, Mclachlan JA. Androgen metabolism in control and in neonatally estrogenized male mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 1991;5:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(91)90043-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos FCA, Góes RM, Carvalho HF, Taboga SR. Structure, histochemistry and ultrastructure of the epithelium and stroma in the gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) female prostate. Tissue Cell. 2003;35:447–457. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(03)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos FC, Leite RP, Custodio AM, et al. Testosterone stimulates growth and secretory activity of the adult female prostate of the gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) Biol. Reprod. 2006;75:370–379. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.051789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarano WR, Cordeiro RS, Goes RM, Taboga SR. Intraepithelial alterations in the guinea pig lateral prostate after estradiol treatment at different ages. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 2004;36:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarano WR, Cordeiro RS, Carvalho HF, Goes RM, Taboga SR. Tissue remodeling in guinea pig lateral prostate at different ages after estradiol treatment. Cell Biol. Intern. 2005;29:778–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarano WR, Vilamaior PSL, Taboga SR. Tissue evidence of the testosterone role on the abnormal growth and aging effects reversion in the gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) prostate. Anat. Rec. A. 2006;228A:1190–1200. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shappell SC, Thomas GV, Roberts RL, et al. Prostate pathology of genetically engineered mice: definitions and classification. The consensus report from the Bar Harbor Meeting of the mouse models of human cancer consortium prostate pathology committee. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2270–2305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taboga SR, Santos AB, Rocha A, Vidal BC, Mello MLS. Nuclear phenotypes and morphometry of human secretory prostatic cells: a comparative study of benign and malign lesions in Brazilian patients. Caryologia. 2003;56:313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Tam CC, Wong YC. Ultrastructural study of the effects of 17β-Oestradiol on the lateral prostate and seminal vesicle of the castred guinea pig. Acta Anat. 1991;141:51–62. doi: 10.1159/000147099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AS, Rowley DR, Heidger PM., Jr Effects of estrogen upon the fine structure of epithelium and stroma in the rat ventral prostate gland. Invest. Urol. 1979;17:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triche TJ, Harkin JC. An ultrastructural study of hormonally induced squamous metaplasia in the coagulating gland of the mouse prostate. Lab. Invest. 1971;6:596–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltri RW, Marlow C, Kahn MA, Miller MC, Epstein JI, Partin AW. Significant variations in nuclear structure occur between and within Gleason grading patterns 3, 4, and 5 determined by digital image analysis. Prostate. 2007 doi: 10.1002/pros.20614. doi 10.1002/pros.20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilamaior PSL, Felisbino SR, Taboga SR, Carvalho HF. Collagen fiber reorganization in the rat ventral prostate following androgen deprivation: an possible role for the smooth muscle cells. Prostate. 2000;45:253–258. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20001101)45:3<253::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilamaior PSL, Taboga SR, Carvalho HF. Modulation of smooth muscle cell function: Morphological evidence for a contractile to synthetic transition in the rat ventral prostate. Cell Biol. Int. 2005;29:809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Principles and methods for the morphometric study of the lung and other organs. Lab. Invest. 1979;12:131–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihua Z, Makela S, Andersson LC, et al. A role for estrogen receptor beta in the regulation of growth of the ventral prostate. Proc. Natl. Acad. USA. 2001;98:6330–6335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111150898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Holterhus PM, Dammshäuser I, Hoffbauer G, Aumüller G. Estrogen-induced morphological and immunohistochemistry changes in stroma and epithelium of rat ventral prostate. Prostate. 1992;21:183–199. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990210303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]