Abstract

We examined the hypothesis that post-burn activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is one aspect of the signalling cascade culminating in post-burn secretion of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α which contributes to post-burn myocardial apoptosis. Studies were designed to determine the time course of the induction of p38MAPK, TNF-α and myocardial apoptosis after burn injury. Our quantitative bacterial culture data demonstrated that viable bacteria reached the heart, and Western blotting data identified the increase in the phosphorylation of p38MAPK at an early time after burn. The peak incidence of myocardial apoptosis was also seen at an early time after burn. The expression of TNF-α mRNA, infiltrated neutrophils and serum creatine phosphokinase myocardial band data peaked at a late time after burn. FR167653, a specific inhibitor of p38MAPK, prevented the induction of myocardial apoptosis, TNF-α expression and myocardial injury after burn. Presumably, the bacterial LPS-induced activation of p38MAPK pathway occurring at an early time after burn induced the subsequent myocardial apoptosis. The p38MAPK-induced activation of pro-inflammatory cytokine appeared to promote the degenerative myocardial injury at a late time after burn. Our present data provided evidence for the hypothesis that the p38MAPK pathway controls both myocardial apoptosis and the pro-inflammatory mediator.

Keywords: caspase-3, myocardial apoptosis, p38MAPK, post-burn heart failure, tumour necrosis factor-α

It has generally been accepted that cardiovascular failure can be induced by thermal injury (Reynolds et al. 1995; Murphy et al. 1998; Carlson & Horton 2006). Previous studies (Horton et al. 1995; Horton 1996; Maass et al. 2002) demonstrated that post-burn myocyte apoptosis occurred in the ventricular myocardium and was temporally correlated with the development of cardiac depression. Comstock et al. (1998) found apoptosis in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged cardiac myocytes due to the production of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and its release from myocytes. It is well known that cardiac myocytes themselves produce TNF-α by the stimulation of bacterial LPS and that the local myocardial TNF-α seems to be a potential source of the TNF-α affecting myocardial function (Tanaka et al. 1994; Hickson-Bick et al. 2006; Shang et al. 2006). The existence of endogenous TNF-α in the cardiovascular system has been reported by several workers (Tanaka et al. 1994; Ballard-Croft et al. 2001; Mukherjee et al. 2003). However, the process in which this mediator induces myocardial apoptosis has not been clearly established, because even the basic question of which cells in the cardiovascular system synthesizes TNF-α during burn injury has not yet been determined. A previous study by Horton et al. (2004) suggested that the burn-related loss of gastrointestinal barrier function and translocation of microbial products were upstream mediators of post-burn myocardial inflammatory signalling and dysfunction.

Recent studies (Ballard-Croft et al. 2001; Kyoi et al. 2006; Li et al. 2006) have shown that p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation is one aspect of the signalling cascade that culminates in post-burn secretion of TNF-α and contributes to post-burn myocardial apoptosis. We have previously demonstrated that bacterial LPS enhances the activation of the renal p38MAPK after burn injury and post-burn renal failure can be more easily observed in infant rats than in adult rats possibly because of the immature intestinal barrier against bacterial LPS (Kita et al. 2004).

Thus, the present study was designed to show post-burn TNF-α localization in the cardiovascular system and the time course of the above-mentioned candidates in post-burn injury by using an infant rat model with a specific inhibitor of p38MAPK in order to estimate the valid cause of heart failure following burn shock.

Materials and methods

Animal and animal care

The Ethics Committee of Animal Care and Experimentation, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, approved all requests for animals and intended procedures of the present study according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institute of Health (NIH publication No. 85–23, revised in 1996).

Ten-day-old male Wistar pups were obtained from Seiwa Experimental Animal Co. (Oita, Japan) from a dam with a litter of six to seven pups at 3–5 days of age. The dams and the pups were allowed to acclimate to their new surroundings. The dams were allowed ad libitum intake of water and standard rat chow. The pups were allowed to nurse ad libitum until the 10th day of life. Ten-day-old pups (weight 18–23 g) were used (as infant rats) for the experiment.

Thermal injury procedure

The animals were anaesthetized by ether inhalation. The burn group rats were then immersed in a water bath at 95 °C for 10 s, resulting in a full-thickness burn of approximately 20% of the total body surface area. FR167653 [1-[7-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-8-(4-pyridyl)pyrazolo[5,1-c](′1,2,4)triazin-2-yl]2-phenylethanedine sulphate monophydrate] R (a gift from Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was diluted with Ringer’s solution (1 mg/ml) and used as a specific inhibitor of p38MAPK (Kimura et al. 2006; Kyoi et al. 2006; Ruusalepp et al. 2007). The animals of the Sham and FR (FR167653 1 mg/100 g s.c.) groups underwent the same procedure, except for the thermal injury; that is, their backs were immersed in a water bath at 20 °C for the same period of time. The treatment of FR at a dose of 1 mg/100 g was enough to induce its previous effect (Matsumoto et al. 2002).

All animals were resuscitated with 0.9% saline (1 ml/100 g body weight) solution administered intraperitoneally and received Lepetan ( = buprenofine 0.2 mg/ml) 0.1 ml/100 g body weight as an analgesic. All animals recovered under an infrared lamp.

Experimental design

Two hundred forty male Wistar infant rats were used. The animals were randomly divided into three sacrificed groups (at 2, 6 and 24 h after treatment) and each of these groups was further divided into the four subgroups mentioned below:

Animals in the ‘Sham group’ (Sham, n = 20) underwent the same treatment but did not receive a thermal injury.

Animals in the ‘Burn group’ (Burn, n = 20) received a 20% burn wound.

The burn wound + FR167653 group (Burn + FR, n = 20) received the FR167653 (1 mg/100 g s.c.) treatment before a 30 min burn wound.

FR167653 group (FR, n = 20) received the FR167653 (1 mg/100 g s.c.) treatment but did not receive a thermal injury.

Bacterial translocation

The testing for bacterial translocation was assessed at 2 h after treatment. Using aseptic technique, through a midline laparotomy incision hearts from six rats per experimental group were taken for bacteriologic cultures. Bacterial qualitative analysis was performed as described previously (Kita et al. 2004).

Immunohistochemical experiment

Light microscopy

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal anti-active caspase-3 (cleaved caspase-3; antibody as marker for apoptosis; Chemicon International Inc., Temecula, CA, USA), was used at a dilution of 1:100. There are several techniques which have been developed for the detection of apoptosis cells. The most widely used technique is the terminal transferase-mediated DNA nick-end labelling assay that recognizes cells containing DNA strand breaks. DNA strand breaks are not only a unique feature of apoptosis but have also been observed in the events of necrosis, repair of reversibly damaged DNA and postmortem autolysis. The detection of caspase-3 is believed to be a unique and sensitive indicator for apoptosis (Fukuzuka et al. 1999; Zidar et al. 2006). So we involved caspase-3 antibody as marker for apoptosis.

Rabbit polyclonal anti-rat myeloperoxidase (MPO; antibody as marker for neutrophil; Lab Vision Co., Fremont, CA, USA) was used.

Immunostaining procedures

At 2, 6 and 24 h after treatment, the rats were killed by bleeding under ether anaesthesia and the hearts were isolated, cut into 2-mm-thick slices and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.6. Immunostaining procedure was performed as described previously (Kita et al. 2004).

The obtained slides were counted as the MPO or cleaved caspase-3 positive cells in 10 randomly selected fields of ventricular myocardium (500 μm)2 for five rats in each group. The obtained data was expressed as the number per fields. All of the histological analysis was performed by a pathologist without prior knowledge of the experimental conditions.

Electron microscopy

Antibodies

Polyclonal goat anti-rat TNF-α antibody (Genzyme Co., Cambridge, MA, USA), diluted to 1:400 in 0.1 M PBS was used.

Immunostaining procedures

At 2, 6 and 24 h after treatment, the rats were killed by bleeding under ether anaesthesia and the hearts were isolated. Selected fields of ventricular myocardium were cut into 2-mm-thick slices and fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.6. Immunostaining procedure was performed as described previously (Kita et al. 2004).

Histological experiment

For light microscope (LM), at 2, 6 and 24 h after treatment, the rats were killed by bleeding under ether anaesthesia and the hearts were isolated, cut into 2-mm-thick slices, fixed in 10% buffered formalin and prepared for LM. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Serum creatine phosphokinase myocardial band isozyme analysis

Myocardial injury was assessed by measuring the creatine phosphokinase myocardial band isozyme (CPK-MB). The value of CPK-MB was determined by the method of electrophoresis using cellulose-acetate membrane associated with enzymatic staining.

Assessment of p38MAPK activation

Western blot analysis was performed. Briefly, the collected heart was homogenized, as we previously reported (Kita et al. 2004), with extraction buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM sodium fluoride and 100 M sodium vanadate) containing the protease inhibitors cocktail. The densities of bands were quantified with scion image beta 4.02 (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MA, USA), and the ratio of phospholyl/non-phospholyl p38MAPK were calculated.

Assessment of TNF-α mRNA expression in the heart

Total RNA was extracted from each heart using Isogen (Nippon gene, Toyama, Japan). One microgram of total RNA of heart was reverse-transcribed by using the Rnase H-reverse Transcription and random hexamers (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). To assess the amount of TNF-α mRNA in each sample, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for TNF-α and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which is a constitutively expressed housekeeping gene. PCR was performed as described previously (Kita et al. 2004). Densitometry was performed with an Adobe photoshop software package (Adobe Systems Inc, Mountain View, CA, USA). We compared the expression levels of TNF-α to GAPDH mRNA by scion image beta 4.02 (Scion Corporation). Levels of TNF-α mRNA expression were normalized relative to GAPDH mRNA in the sample. The values were similar to those of p38MAPK activation described above.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SE. Differences among groups were examined for statistical significance using one-way anova and Fisher post hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 denoted the presence of a statistically significant difference.

Results

Bacterial translocation

The results of the quantitative bacterial culture of tissue samples are depicted in Table 1. In the Burn group, 33% of the animals showed bacterial translocation to the heart. Bacteria isolated from organs were Escherichia coli and Moeganella spp. In the other groups, positive tissue cultures for enteric bacteria were not observed.

Table 1.

Bacterial translocation of enteric organisms at 2 h after burn

| Tissue samples | Sham | Burn | Burn + FR | FR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | 0/6 | 2/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 |

Number of bacterial positive animals/number of animals.

Immunohistochemical experiment

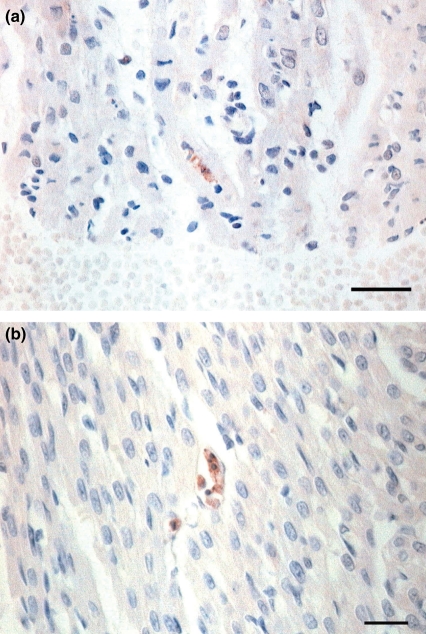

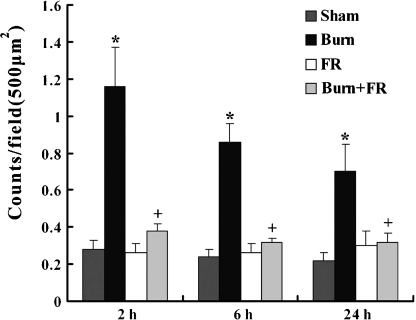

Apoptosis in the heart was detected by immunohistochemical staining. In the Burn group, activated caspase-3 stained the cytoplasm of cardiac myocytes indicating apoptotic cells (Figure 1a), and these activated caspase-3 positive reactions were also observed in the vascular endothelium (Figure 1b) and inflammatory cells. In the other groups, such apoptotic immunoreactions were rarely observed. These results are shown quantitatively in Figure 2. The expression of apoptosis in the Burn group was significantly higher (1.16 ± 0.21 counts/field at 2 h, 0.86 ± 0.1 counts/field at 6 h and 0.7 ± 0.15 counts/field at 24 h after burn) than in the Sham group (0.28 ± 0.05 counts/field at 2 h, 0.24 ± 0.04 counts/field at 6 h and 0.22 ± 0.04 counts/field at 24 h). In contrast to the burn group, the incidence of apoptosis in the Burn + FR group was significantly lower (0.38 ± 0.04 counts/field at 2 h, 0.32 ± 0.02 counts/field at 6 h and 0.32 ± 0.05 counts/field at 24 h).

Figure 1.

Light micrograph of immunohistochemical staining for activated caspase-3 showing the heart of infant rats at 2 h after burn. (a) In the Burn group, a clustered appearance of reddish brown precipitates seen in the cytoplasm of cardiac myocyte showed apoptotic cell (Bar = 25 μm). (b) In the Burn group, activated caspase-3 immunoreactions were localized in the vascular endothelium (Bar = 25 μm).

Figure 2.

Incidence of apoptotic cells in the cardiac myocyte of ventricular wall (500 μm)2 after burn. Data are shown as mean ± SE for five rats. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham and +P < 0.05 between Burn and Burn + FR.

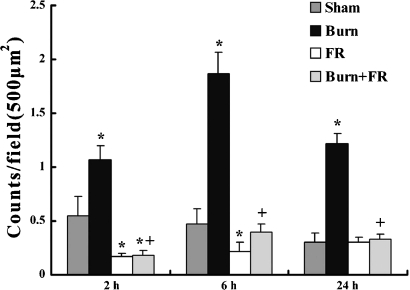

The immunohistochemical MPO staining of heart was observed and these results are shown semiquantitatively in Figure 3. The expression of MPO positive cells in the Burn group was significantly higher (1.07 ± 0.13 counts/field at 2 h, 1.87 ± 0.2 counts/field at 6 h and 1.22 ± 0.09 counts/field at 24 h after burn) than in the Sham group (0.55 ± 0.18 counts/field at 2 h, 0.47 ± 0.14 counts/field at 6 h and 0.3 ± 0.09 counts/field at 24 h). In contrast to burn group, the incidence of MPO positive cells in the Burn + FR group was significantly lower (0.18 ± 0.05 counts/field at 2 h, 0.4 ± 0.07 counts/field at 6 h and 0.33 ± 0.05 counts/field at 24 h).

Figure 3.

Incidence of activated neutrophils in the ventricular wall (500 μm)2 after burn. Data are shown as mean ± SE for five rats. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham and +P < 0.05 between Burn and Burn + FR.

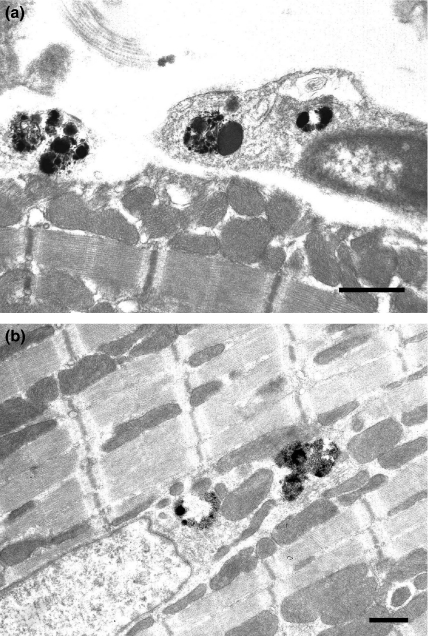

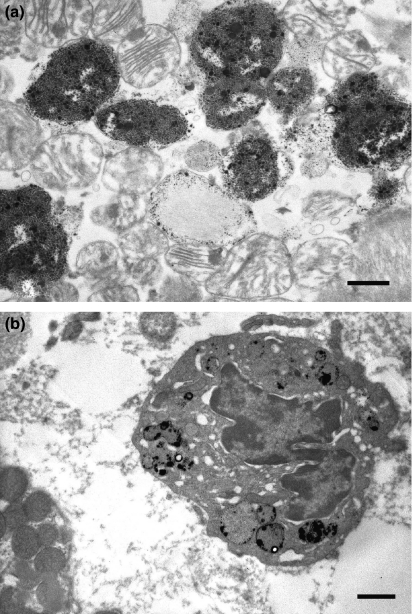

In the Burn group, immunoreactions for TNF-α were localized in the lysosomes of the vascular endothelium (Figure 4a) and cardiac myocytes (Figure 4b) at 2 h after burn. At 6 h after burn, immunoreactions of TNF-α were localized in the lysosomes of degenerating cardiac myocytes (Figure 5a) and neutrophils (Figure 5b), and these immunoreactions were observed at 24 h after burn. In the other groups, TNF-α immunoreactions were not observed.

Figure 4.

Electron micrograph of immunohistochemical staining for TNF-α showing the heart of infant rats at 2 h after burn. (a) In the Burn group, TNF-α immunoreactions were localized in the lysosome of vascular endothelium (Bar = 500 nm). (b) In the Burn group, TNF-α immunoreactions were localized in the lysosome of cardiac myocyte (Bar = 500 nm).

Figure 5.

Electron micrograph of immunohistochemical staining for TNF-α showing the heart of infant rats at 6 h after burn. (a) In the Burn group, TNF-α immunoreactions were localized in the lysosome of degenerating cardiac myocyte (Bar = 500 nm). (b) In the Burn group, TNF-α immunoreactions were localized in the lysosome of neutrophil (Bar = 1 μm).

Histological examination

Light microscopic findings of the heart revealed that some neutrophils, which often existed in the interstitial space or vascular cavity, were observed in the Burn group at 2 h after treatment. The frequency of the infiltrations of inflammatory cells increased, and the eosinophilic, hypertrophic and interstitial oedematous changes of cardiomyocytes increased at 6 h after burn. The interstitial oedematous changes continued at 24 h after burn. Abnormal histological changes were not seen in the other groups.

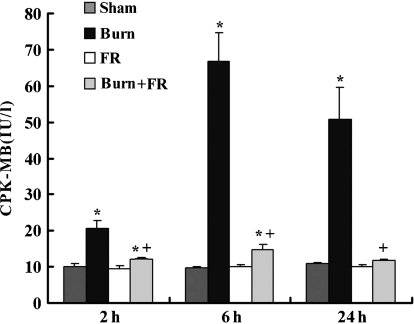

The value of serum CPK-MB

There was no change of CPK-MB value in the Sham group (10.0 ± 0.9 IU/l at 2 h, 9.6 ± 0.3 IU/l at 6 h and 10.8 ± 0.5 IU/l at 24 h after burn) or FR groups throughout the experimental period (Figure 6). The CPK-MB value in the Burn group was significantly higher (20.6 ± 2.1 IU/l at 2 h, 66.7 ± 8.0 IU/l at 6 h and 50.6 ± 8.9 IU/l at 24 h after burn) than the Sham group. In contrast to the Burn group, CPK-MB value in the Burn + FR group was significantly lower (12.0 ± 0.3 IU/l at 2 h, 14.8 ± 1.4 IU/l at 6 h and 11.8 ± 0.4 IU/l at 24 h after burn).

Figure 6.

Evaluation of heart injury of infant rats after burn with FR167653 treatment. The degree of heart injury was assessed by measuring creatine phosphokinase myocardial band (CPK-MB) value (IU/l). Data are shown as mean ± SE for five rats. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham and +P < 0.05 between Burn and Burn + FR.

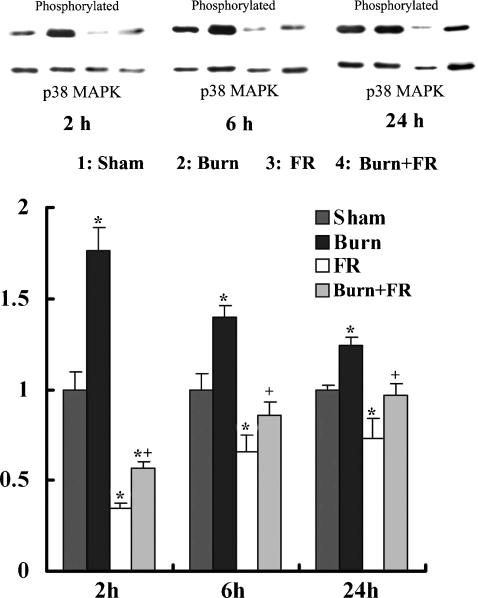

Assessment of p38MAPK activation in the heart

Figure 7 shows the relative p38MAPK phosphorylation levels that were expressed relative to sham levels after normalization with p38MAPK. At 2, 6 and 24 h after treatment, the ratio levels of p38MAPK phosphorylation in the Burn group were significantly higher than in those of the Sham group. At 2 h after treatment, the administration of FR167653 significantly decreased the phosphorylation levels of p38MAPK in the Burn + FR and FR groups compared to the Sham group. At 6 h after treatment, the ratio levels of p38MAPK phosphorylation significantly decreased in the FR groups compared to the Sham group. At 24 h after treatment, there were no significant differences in the Burn + FR and FR groups compared to the Sham group. In contrast to the Burn group, the ratio levels of p38MAPK phosphorylation in the Burn + FR group were significantly lower.

Figure 7.

Effects of FR167653 on p38MAPK activation (assessed by Western blotting method) in the heart of infant rats. Relative p38MAPK phosphorylation levels were expressed relative to Sham levels after normalization with p38MAPK. Data were expressed as the mean ± SE for five rats. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham and +P < 0.05 between Burn and Burn + FR.

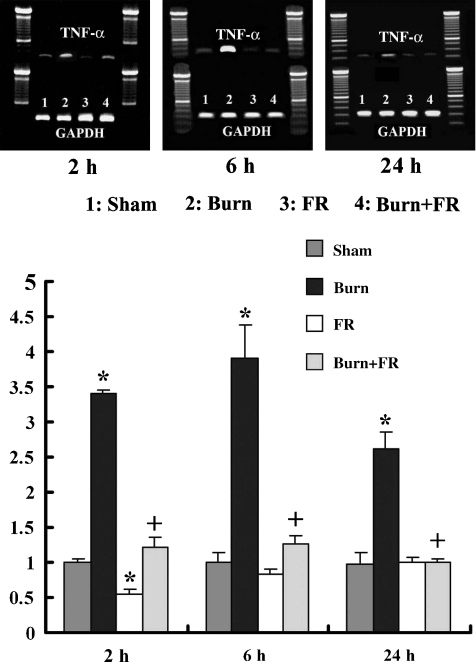

TNF-α mRNA expression in the heart

Figure 8 shows the relative TNF-α mRNA expression levels that were expressed relative to the sham levels after normalization with GAPDH. The ratio levels of TNF-α mRNA expression in the Burn group significantly increased compared to the Sham group at 2, 6 and 24 h after treatment. The TNF-α mRNA expression in the FR group significantly decreased when compared with the Sham group at 2 h after treatment. In contrast to the Burn group, the ratio levels of TNF-α mRNA expression in the Burn + FR group were significantly lower.

Figure 8.

Effects of FR167653 on TNF-α mRNA in the heart of infant rat after burn. Relative TNF-α mRNA expression levels were expressed relative to Sham levels after normalization with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Data were expressed as the mean ± SE for five rats. *P < 0.05 vs. Sham and +P < 0.05 between Burn and Burn + FR.

Discussion

Our present immunohistochemical data showed that a positive reaction for caspase-3 positive reaction was observed in the cytoplasm of cardiac myocytes and vascular endothelia. The incidence of myocardial apoptosis peaked quantitatively at 2 h after burn injury as shown in Figure 2. Carlson et al. (2002) suggested that burn plasma may account for the apoptotic effect via an endotoxin-dependent mechanism and their data showed that TNF-α was not directly involved in the pathogenesis of burn-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Petillot et al. (2007) demonstrated that LPS-treated rat heart could be related to the activation of caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway in cardiac myocytes. Our previous data (Kita et al. 2004) showed that gut barrier function was impaired as early as 2 h after burn, and the present data demonstrated that viable bacteria reached the heart at that time. These results support the idea that the bacterial LPS entering the blood flow may induce myocardial apoptosis after burn.

Previous studies (Wang et al. 1998, 2004; Li et al. 2006) have clearly demonstrated that the bacterial LPS activated the p38MAPK pathway and suggested that the p38MAPK family was important for the induction of myocardial apoptosis. Recent studies (Baines & Molkentin 2005; Fiedler et al. 2006) have pointed to p38MAPK as a central regulator of apoptosis in cardiac myocytes that can have both pro- and anti-apoptotic effects depending on the cell death-inducing stimulus and upstream signalling events leading to its activation. We used FR167653 as an inhibitor of p38MAPK activation. Pharmacological characteristics and chemical structure of FR resemble those of pyridinyl imidazole inhibitor of p38MAPK such as SB203580 and RWJ67657 (Takahashi et al. 2001). In other clearly defined experimental studies on cardiac damage, SB203580 was used as a specific inhibitor to suppress p38MAPK phosphorylation (Ballard-Croft et al. 2001; Lu et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2004; Okada et al. 2005). FR167653 showed a stronger inhibitory effect on the heart than SB203580 in several studies (Kimura et al. 2006; Kyoi et al. 2006). Takahashi et al. (2001) demonstrated that FR167653 inhibited p38αMAPK activity in a dose-dependent pattern without affecting the activities of other kinases such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (EPK)-1, c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK)-2, protein kinase A, protein kinase C, protein kinase G, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase and cyclooxygenase. In the present study, FR167653 decreased the activity of cardiac p38MAPK and prevented the induction of myocardial apoptosis after burn. These data show that bacterial LPS may correlate with the activation of the p38MAPK pathway and that the activated p38MAPK induces myocardial apoptosis at an early time after burn.

It is well known that bacterial LPS stimulates the produced of TNF-α by cardiac myocytes (Tanaka et al. 1994; Shang et al. 2006; Yayama et al. 2006). Comstock et al. (1998) suggested that apoptosis was induced in LPS-challenged cardiac myocytes mediated by the TNF-α produced by myocytes. Our present data showed that the peak of myocardial apoptosis was seen at 2 h after burn, while the peak of TNF-α mRNA levels was seen at 6 h after burn. The peak of infiltrated neutrophils was also observed at 6 h after burn and coincident when lysosomes were stained with immunoreactions of TNF-α. Thus, it appears that the increase of the genetic cytokine in the heart was induced by infiltrated neutrophils to the heart. Niederbichler et al. (2006) demonstrated that an early depression of cardiomyocyte sarcomere contractility was induced as early as 1 h after burn and suggested that the event was induced without significant induction of myocardial proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. Raeburn et al. (2002) demonstrated that neutrophil depletion did not prevent LPS-induced myocardial depression. Conceivably then, the first attack of activated p38MAPK, which could be enhanced by the bacterial LPS, may have induced the myocardial apoptosis in the present experiments.

Our serum CPK-MB data (Figure 6) showed that the burn-induced myocardial injury was assessed throughout the experiment period. It peaked at 6 h after burn, and the peak of infiltrated neutrophil levels was also observed at 6 h after burn at the same levels as TNF-α mRNA (Figures 3 and 8). FR167653 decreased the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and prevented the burn-induced myocardial injury in the present study. Wencker et al. (2003) showed that very low levels of cardiac myocyte apoptosis such as 23 myocytes per 105 nuclei in transgenic caspase-activated samples compared with 1.5 myocytes per 105 nuclei in controls is sufficient to cause death. They suggested that myocardial apoptosis might be causal mechanisms for cardiac depression. This could possibly account for the cardiac deterioration in the early phase of this study. Raeburn et al. (2002) suggested that neutrophil infiltration could lead to tissue necrosis of the myocardium, since it is well known that cardiac myocytes themselves produce TNF-α by the stimulation of the LPS-activated p38MAPK pathway. Some investigators (Tanaka et al. 1994; Chen et al. 2006) have demonstrated that bacterial LPS can induce neutrophils to secrete cytokines. TNF-α has been reported to promote myocardial degeneration via direct cytotoxicity (Bolger & Anker 2000; Maass et al. 2002). Our immunohistochemical data demonstrated that TNF-α was localized in the lysosomes of the degenerate cardiac myocytes and infiltrated neutrophils and that the peak cytokine levels were observed at 6 h after burn. This late burn-induced myocardial injury may be due to the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines released from the infiltrated neutrophils or cardiac myocytes themselves.

In conclusion, this study has shown that the activation of the p38MAPK pathway, which is related to bacterial LPS, occurs earlier in the post-burn period and induces myocardial apoptosis. It also revealed that the pro-inflammatory cytokine is produced from cardiac myocytes and infiltrated neutrophils triggered by p38MAPK activation and promotes the degenerative myocardial injury later in the post-burn period. The direct correlation between apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine could not be established, although the p38MAPK activation was demonstrated to lead their outbreaks following burn shock.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid scientific research (No. 17590589) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- Baines CP, Molkentin JD. STRESS signaling pathways that modulate cardiac myocyte apoptosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;38:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard-Croft C, White DJ, Maass DL, Hybki DP, Horton JW. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in cardiac myocyte secretion of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-alpha. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001;280:H1970–H1981. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AP, Anker SD. Tumour necrosis factor in chronic heart failure: a peripheral view on pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and therapeutic implications. Drugs. 2000;60:1245–1257. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DL, Horton JW. Cardiac molecular signaling after burn trauma. J. Burn Care Res. 2006;27:669–675. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000237955.28090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DL, Lightfoot E, Jr., Bryant DD. Burn plasma mediates cardiac myocyte apoptosis via endotoxin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;282:H1907–H1914. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00393.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LW, Huang HL, Lee IT, Hsu CM, Lu PJ. Thermal injury-induced priming effect of neutrophil is TNF-alpha and P38 dependent. Shock. 2006;26:69–76. doi: 10.1097/01.shk0000209531.38188.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock KL, Krown KA, Page MT. LPS-induced TNF-alpha release from and apoptosis in rat cardiomyocytes: obligatory role for CD14 in mediating the LPS response. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1998;30:2761–2775. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler B, Feil R, Hofmann F. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I inhibits TAB1-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase apoptosis signaling in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:32831–32840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzuka K, Rosenberg JJ, Gaines GC. Caspase-3-dependent organ apoptosis early after burn injury. Ann. Surg. 1999;229:851–859. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson-Bick DL, Jones C, Buja LM. The response of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes to lipopolysaccharide-induced stress. Shock. 2006;25:546–552. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209549.03463.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JW. Cellular basis for burn-mediated cardiac dysfunction in adult rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H2615–H2621. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JW, Garcia NM, White DJ, Keffer J. Postburn cardiac contractile function and biochemical markers of postburn cardiac injury. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1995;181:289–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JW, Tan J, White DJ, Maass DL, Thomas JA. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract attenuated the myocardial inflammation and dysfunction that occur with burn injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H2241–H2251. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00390.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Shintani-Ishida K, Nakajima M. Ischemic preconditioning or p38 MAP kinase inhibition attenuates myocardial TNF alpha production and mitochondria damage in brief myocardial ischemia. Life Sci. 2006;78:1901–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita T, Yamaguchi H, Sato H. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway on renal failure in the infant rat after burn injury. Shock. 2004;21:535–542. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyoi S, Otani H, Matsuhisa S. Opposing effect of p38 MAP kinase and JNK inhibitors on the development of heart failure in the cardiomyopathic hamster. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;69:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Ma JY, Kerr I. Selective inhibition of p38α MAPK improves cardiac function and reduces myocardial apoptosis in rat model of myocardial injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;291:H1972–H1977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Shimpo H, Shimamoto A. Specific inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase with FR167653 attenuates vascular proliferation in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004;128:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass DL, Hybki DP, White J, Horton JW. The time course of cardiac NF-kappaB activation and TNF-alpha secretion by cardiac myocytes after burn injury: contribution to burn-related cardiac contractile dysfunction. Shock. 2002;17:293–299. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto Y, Ito Y, Hayashi I. Effect of FR167653, a novel inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta synthesis on lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatic microvascular dysfunction in mice. Shock. 2002;17:411–415. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Banerjee SK, Maulik M. Protection against acute adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity by garlic: role of endogenous antioxidants and inhibition of TNF-alpha expression. BMC Pharmacol. 2003;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JT, Horton JW, Purdue GF, Hunt JL. Evaluation of troponin-I as an indicator of cardiac dysfunction after thermal injury. J. Trauma. 1998;45:700–704. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederbichler AD, Westfall MV, Su GL. Cardiomyocyte function after burn injury and lipopolysaccharide exposure: single-cell contraction analysis and cytokine secretion profile. Shock. 2006;25:176–183. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000192123.91166.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Otani H, Wu Y. Role of F-actin organization in p38 MAP kinase-mediated apoptosis and necrosis in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes subjected to simulated ischemia and reoxygenation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;289:H2310–H2318. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00462.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petillot P, Lahorte C, Bonanno E. Annexin V detection of lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac apoptosis. Shock. 2007;27:69–74. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235085.56100.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeburn CD, Dinarello CA, Zimmerman MA. Neutralization of IL-18 attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H650–H657. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00043.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds EM, Ryan DP, Sheridan RL, Doody DP. Left ventricular failure complicating severe pediatric burn injuries. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1995;30:264–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruusalepp A, Czibik G, Flatebo T, Vaage J, Valen G. Myocardial protection evoked by hyperoxic exposure involves signaling through nitric oxide and mitogen activated protein kinases. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2007;102:318–326. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang F, Zhao L, Zheng Q. Simvastatin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes: the role of reactive oxygen species. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;351:947–952. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Keto Y, Fujita T, Uchiyama T, Yamamoto A. FR167653, a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, prevents Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis in Mongolian gerbils. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;296:48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Kita T, Kasai K, Nagano T. The immunocytochemical localization of tumour necrosis factor and leukotriene in the rat heart and lung during endotoxin shock. Virchows Arch. 1994;424:273–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00194611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Huang S, Sah VP. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2161–2168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Sankula R, Tsai BM. P38 MAPK mediates myocardial proinflammatory cytokine production and endotoxin-induced contractile suppression. Shock. 2004;21:170–174. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000110623.20647.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wencker D, Chandra M, Nguyen K. A mechanistic role for cardiac myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1497–1504. doi: 10.1172/JCI17664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayama K, Hiyoshi H, Sugiyama K, Okamoto H. The lipopolysaccharide-induced up-regulation of bradykinin B(2)-receptor in the mouse heart is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and angiotensin II. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006;29:1143–1147. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidar N, Dolenc-Strazar Z, Jeruc J, Stajer D. Immunohistochemical expression of activated caspase-3 in human myocardial infarction. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]