Abstract

A highly efficient one-pot methodology is described for the synthesis of heparin and heparan sulfate oligosaccharides utilizing thioglycosides with well defined reactivity as building blocks. l-idopyranosyl and d-glucopyranosyl thioglycosides 5 and 10 were used as donors due to low reactivity of uronic acids as the glycosyl donors in the one-pot synthesis. The formation of uronic acids by a selective oxidation at C-6 was performed after assembly of the oligosaccharides. The efficiency of this strategy with the flexibility for sulfate incorporation was demonstrated in the representative synthesis of disaccharides 17, 18, tetrasaccharide 23 and pentasaccharide 26.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Heparin, Oligosaccharides, One-Pot Synthesis, Thioglycoside

Introduction

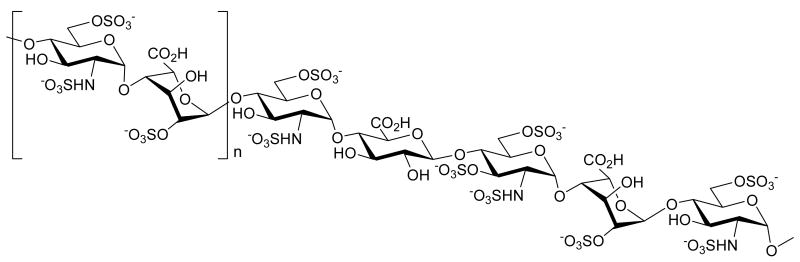

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are a family of highly sulfated, linear polyanionic molecules that are found on most animal cell surfaces as well as in the basement membranes and other extracellular matrixes. Heparin and heparan sulfate are the most widely studied members of this family. Heparin is exclusively synthesized by tissue mast cells and is stored in cytoplasmic granules, whereas the closely related molecule heparan sulfate is expressed on cell surfaces and throughout tissue matrices.1 They are composed of repeating disaccharide units of 1→4 linked uronic acid and d-glucosamine (Figure 1). The uronic acid residues typically consist of 90% l-iduronic acid and 10% of d-glucuronic acid. The interaction of these polyanionic molecules with proteins plays an important role in several biological recognition processes, including blood coagulation, virus infection, cell growth, inflammation, wound healing, tumor metastasis, lipid metabolism and diseases of the nervous system.1,2

Figure 1.

Schematic view of heparin

The biosynthesis of heparin and heparan sulfate occurs by similar pathways.2 Chain initiations occur in the Golgi apparatus. The first step in the pathway involves the attachment of a tetrasaccharide fragment to a serine residue in the core protein. This structure is then modified by a series of enzymatic transformations involving N-deacetylation followed by N-sulfation, substrate directed epimerization of glucuronic acid to iduronic acid moieties, and finally O-sulfation. Although these enzymatic modifications result in a mixture of very complex polysaccharides, structural studies have shown that heparin/heparan sulfates are composed of only 19 distinct disaccharide subunits, differing in their sulfation pattern and in the presence of either d-glucuronic or l-iduronic acid.

To date, more than one hundred heparin-binding proteins have been identified. With the exception of the antithrombin III-heparin interaction3, in which the minimal sequence of heparin pentasaccharide is required for binding, the structure and function of heparin interaction with proteins is poorly understood. This is mainly due to the complexity and heterogeneity of these polymers. With the discovery of increasing numbers of heparin-binding proteins, there is a need to characterize the molecular elements responsible for binding to a particular protein and modulating its biological activity. Since the first total synthesis of heparin pentasaccharide4, numerous synthetic methodologies have been reported for the synthesis of heparin fragments.5 Most of the strategies involve traditional stepwise oligosaccharide synthesis in which protecting group and anomeric leaving group manipulations, intermediate work-up and purification in each step are required. Access to differentially substituted derivatives is important for dissecting recognition and activity, as recently demonstrated in the synthesis of heparin6 and chondroitin sulfates7. A rapid and truly practical strategy capable of creating diverse derivatives of heparin oligosaccharides with differential sulfation pattern would be useful for detailed functional studies of these important molecules. Recently, we reported a reactivity-based one-pot method for complex oligosaccharides synthesis. In this methodology, the oligosaccharide is assembled rapidly by sequential addition of thioglycoside building blocks, with the most reactive one being added first.8 The generality of thioglycosides makes them convenient and attractive building blocks due to their stability, accessibility and compatibility.9 Here we report an efficient one-pot strategy for the rapid assembly of representative heparin and heparan sulfate oligosaccharides.

Results and Discussion

For the synthesis of heparin and heparin sulfate, one has to overcome a range of synthetic difficulties imposed by the complex structure of heparin and heparin sulfate saccharides. Besides the careful design of protecting group strategy to enable the installation of sulfate groups on selected hydroxyl and amino functions, the stereoselective construction of the glucosamine-uronic acid backbone has to be developed. The use of uronic acid building blocks as glycosyl donor10 is limited and is often avoided,11 because uronic acids are prone to epimerization, have the inherent low reactivity imposed by the C-5 carboxyl group and complicate protecting group manipulations. Thus, in our synthetic approach, the formation of uronic acids by selective oxidation at the C-6 hydroxyl group was done after assembly of oligosaccharides. Control of the stereoselectivity of each glycosylation and generation of a significant reactivity difference between the thioglycosides are crucial for the successful synthesis of heparin oligosaccharides with the one-pot strategy. The reactivity of a sugar is highly dependent on its protecting groups and the anomeric activating group used. The reactivity differences between thioglycosides were mainly influenced by electron-donating and electron-withdrawing protecting groups. To this end, the hydroxyl groups to be sulfated were protected as acyl (acetyl and benzoyl) groups. Selective removal of acetate esters12 in the presence of benzoates also enabled us to synthesize oligosaccharides with differential sulfation patterns. The primary hydroxyl groups to be selectively oxidized to uronic acids were protected as tert-butyldiphenylsilyl ethers. Finally, benzyl groups were installed on the remaining hydroxyls and the amino functionalities were masked as azides. Relative reactivity values (RRV) of monosaccharide building blocks were obtained by HPLC analysis with the established competitive assay method. 8a,13

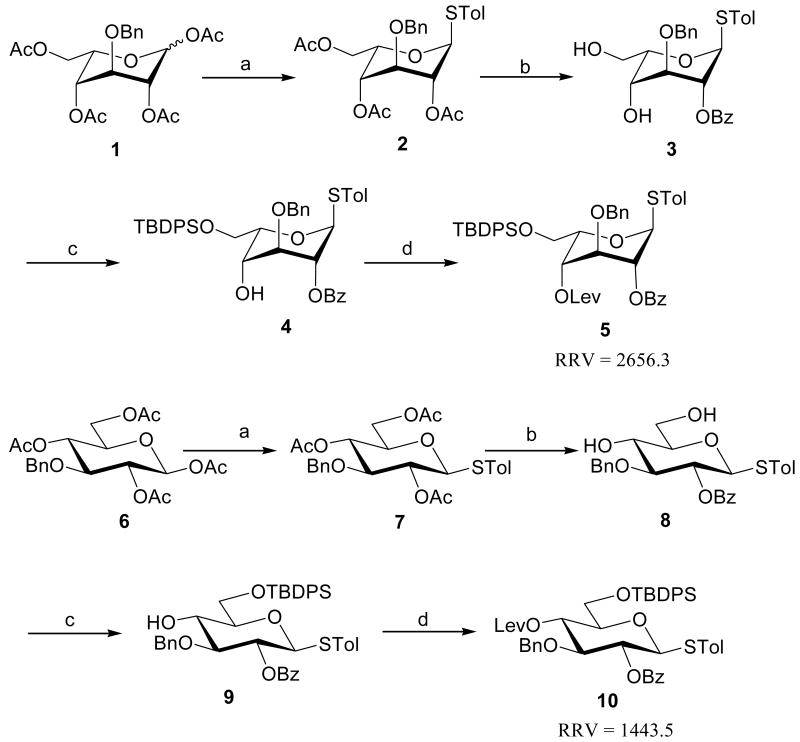

To test the above synthetic strategy, fully protected disaccharides 17, 18, tetrasaccharide 23 and pentasaccharide 26 (a binding epitope for antithrobin III) were selected as model saccharides. Thus, l-idopyranosyl, d-glucopyranosyl and azidoglucosyl thioglycosides were designed and prepared using above synthetic strategy (Scheme 1). The known 1,2,4,6-O-tetra-O-acetyl-3-O-benzyl-α/β-d-idopyranoside14 was used as starting material for the construction of 5. The reaction of 1 with p-toluenethiol in the presence of BF3·Et2O gave 2 in 93% yield. Standard removal of acetate esters in 2 and formation of the 4,6-O-benzylidene acetal, followed by protection of the C-2 hydroxyl as a benzoate ester, which was chosen for its participating group assistance in the forthcoming glycosylation reaction. Subsequent acidolysis of the cyclic acetal afforded idopyranosyl thioglycoside 3 in 78% yield. Using standard methods, introduction of the tert-butyldiphenylsilyl group at C-6 (91%) and introduction of the levulinyl group at C-4 provided fully protected idopyranosyl thioglycoside 5 (RRV = 2656.4) in 89% yield. This route was also applied to the synthesis of glucopyranosyl thioglycoside 10 (RRV = 1443.5) starting from the known 1,2,4,6-O-tetra-O-acetyl-3-O-benzyl-β-D-glucopyranoside15 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of the 1-thio uronic acid building blocks 5 and 10a

aReagents and conditions: (a) TolSH, BF3·Et2O, 2: 93% (9:1 α/β), 7: 87%; (b) i. NaOMe, MeOH; ii. PhCH(OMe)2, p-TsOH, CH3CN/DMF; iii. BzCl, Pyridine; iv. 60% TFA in H2O, CH2Cl2, 3: 78%, 8: 81%; (c) TBDPSCl, Pyridine, 4: 91%, 9: 95%; d) Lev2O, Pyridine, 5: 89%, 10: 91%.

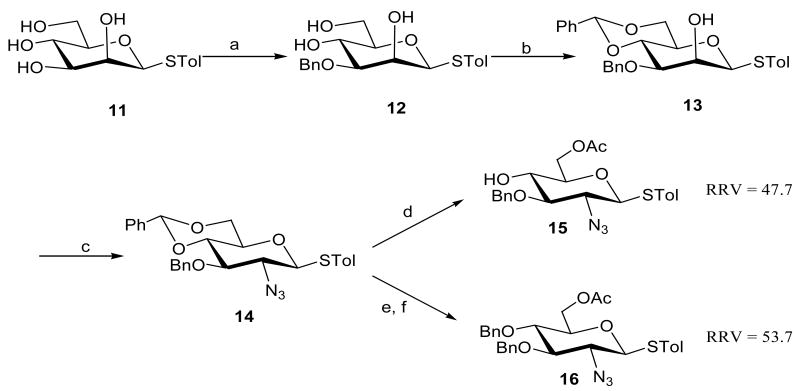

Next azidoglucosyl thioglycoside building blocks 15 and 16 were synthesized following our previously reported methods (Scheme 2).5f Briefly, the C-3 hydroxyl was selectively protected as a benzyl ether after di-n-butyltin oxide activation.16 Direct benzylidination of resulting 12 afforded 13 in 89% yield. Azidoglucosyl thioglycoside derivative 14 was formed through a two-step sequence: triflation of the free hydroxyl was followed by nucleophilic substitution with NaN3 in DMF gave compound 14 in 83%. Removal of 4,6-O-benzylidene acetal and regioselective introduction of the acetyl group at C-6 afforded the fully protected azidoglucosyl acceptor 15 (RRV = 47.7). In a similar manner, selective opening of 4,6-O-benzylidene acetal in 14 using PhBCl2 and Et3SiH, followed by acetylation at C-6 afforded azidoglucosyl donor 16 (RRV = 53.7).

Scheme 2.

Preparation of azidoglucosyl acceptors 15 and 16a

aReagents and conditions: (a) i. Bu2SnO, Toluene ii. Bu4NBr, BnBr, 65% in two steps; (b) PhCH(OMe)2, CSA, 89%; (c) i. Tf2O, Pyr-CH2Cl2, ii. NaN3, DMF, 83% in two steps; (d) i. 80% AcOH, ii. AcCl, Pyridine, 15: 89%; (e) PhBCl2, Et3SiH, CH2Cl2, 92%; (f) Ac2O, Pyridine, 16: 95%;

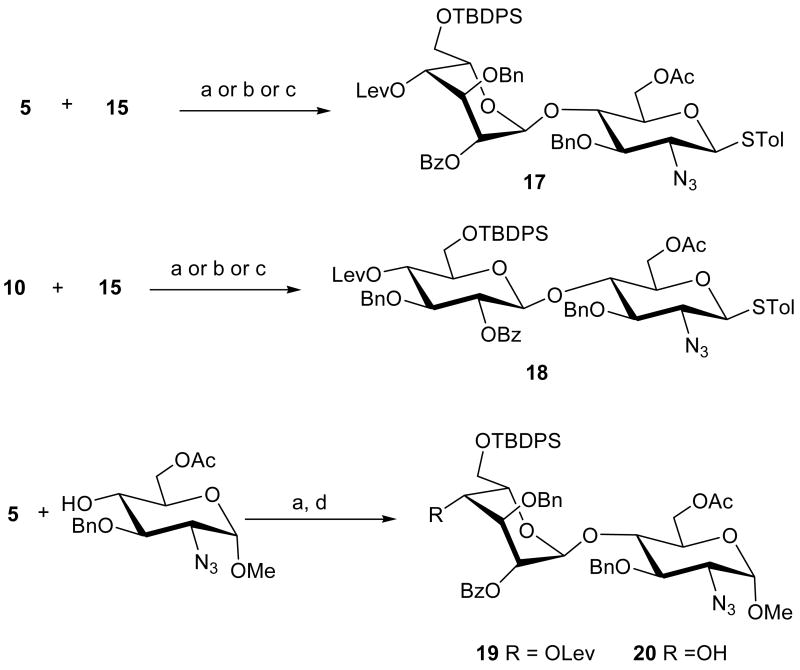

With all monosaccharide building blocks in hand, we turned our attention to the one-pot synthesis of heparin oligosaccharides. First, disaccharide formation by different thioglycoside activators was examined, using N-iodosuccinimide/trifluoromethanesulfonic (triflic) acid (NIS/TfOH),8a benzenesulfinyl piperidine (BSP)/triflic anhydride (Tf2O)8b or N-(phenylythio)-ε-caprolactam/Tf2O.8c These activators were previously used in several reactivity-based one-pot syntheses.8 Since the reactivity of idopyranosyl thioglycoside 5 (RRV=2656.3) or glucopyranosyl thioglycoside 10 (RRV=1443.5) is much higher than that of 15 (RRV=47.7), glycosylation of donor 5 or 10 with azidoglucosyl thioglycoside acceptor 15 afforded the desired disaccharide 17 or 18 in excellent yield and stereoselectivity with no self coupling of 5 (Scheme 3). Slightly better yield was observed in both cases using NIS/TfOH as activator. In addition, disaccharide acceptor 20 was synthesized in a straightforward manner (Scheme 3). Glycosylation of 5 with methyl 2-azido-3-O-benzyl-2-deoxy-α-d-glucopyronoside10a in the presence of NIS/TfOH afforded desired disaccharide 19 in 96% yield. Removal of the levulinyl group with NH2NH2/AcOH/Pyridine afforded disaccharide acceptor 20 in 95% yield.

Scheme 3.

One-pot synthesis of disaccharide derivatives 17 – 20

aReagents and conditions: (a) NIS, TfOH, CH2Cl2, -45°C to room temperature, 17: 92%, 18: 89%, 19: 96%; (b) BSP, Tf2O, CH2Cl2, -45°C to room temperature, 17: 72%, 18: 75%; (c) N-(phenylythio)-ε-caprolactam, Tf2O, CH2Cl2, -45°C to room temperature, 17: 85%, 18: 88%; (d) NH2NH2/AcOH/Pyridine, 20: 95%.

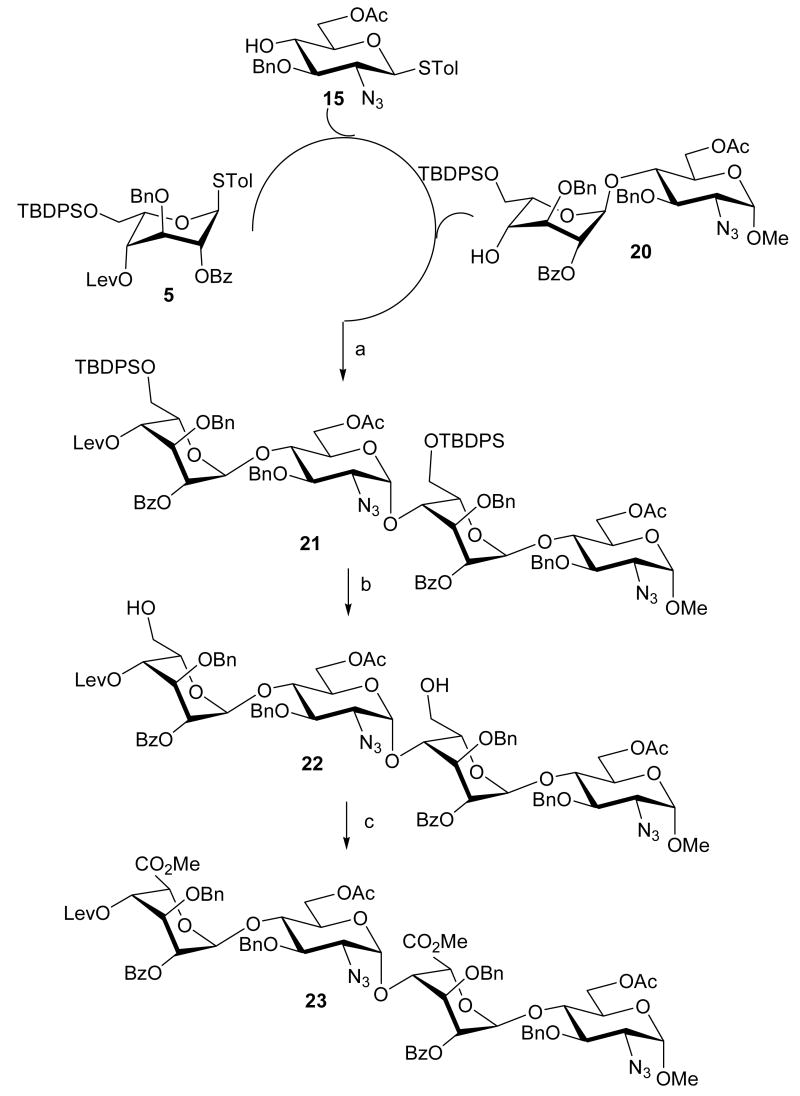

In an effort to extend the application of one-pot synthesis, syntheses of tetrasaccharide and pentasaccharide were next examined. For the one-pot tetrasaccharide synthesis (Scheme 4), fully protected idopyranosyl donor 5 was first coupled with azidoglucosyl acceptor 15 in the presence of NIS/TfOH at -45°C followed by slow warming to room temperature. After 3 h, α-methyl disaccharide acceptor 20 was added, followed by the addition NIS/TfOH at the same temperature. The fully protected tetrasaccharide 21 was obtained in 35% yield. With this methodology, protecting group and anomeric leaving group manipulations, intermediate work-up and purification can be avoided. Removal of the silyl ether protection group with HF·pyridine afforded 22 in 87% yield. The resulting primary hydroxyl groups were oxidized with 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) and NaOCl as a co-oxidant5g under basic conditions (pH = 10). The corresponding carboxyl groups were then esterified in the presence of MeI and KHCO3 to give the desired fully protected tetrasaccharide 23 in 68% yield over two steps.

Scheme 4.

One-pot synthesis of tetrasaccharide derivative 23a

aReagents and conditions: (a) NIS, TfOH, CH2Cl2, -45°C to room temperature, 35%; (b) HF·Pyr, THF, 87%; (c) i. TEMPO, KBr, NaOCl, CH2Cl2, H2O, ii. MeI, KHCO3, DMF, 68% in two steps.

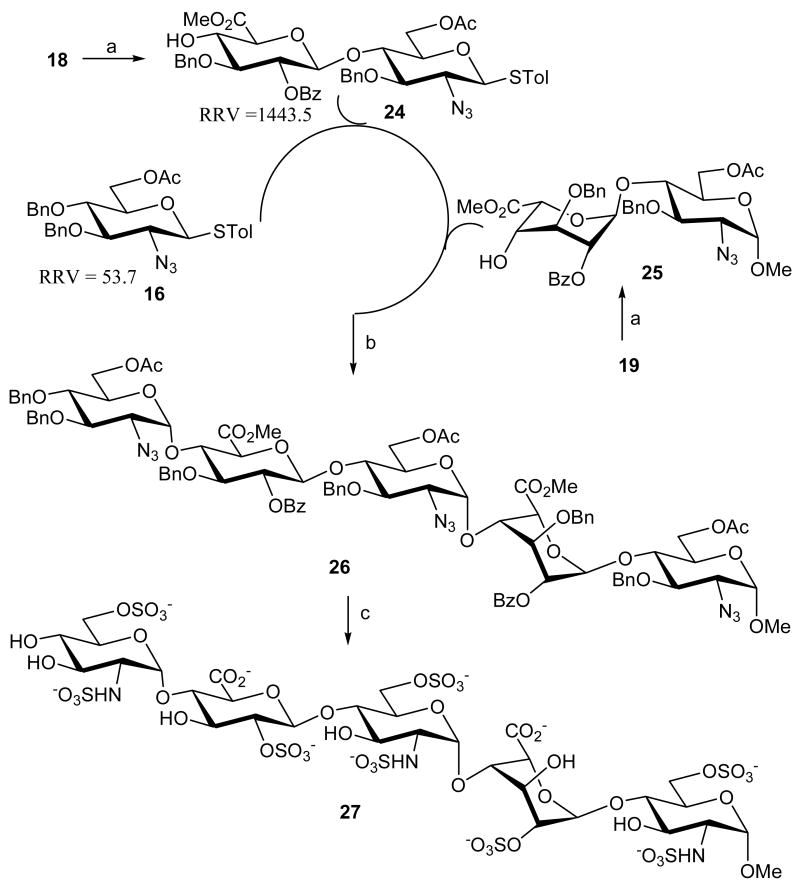

When the same approach was applied to the one-pot synthesis of the pentasaccharide, unfortunately, the yield in the first glycosylation was very low. This was partially attributed to the bulky silyl group at C-6 on 18 which partially blocks the C-4 hydroxyl. Changing the silyl protection at C-6 to a smaller group was expected to increase the yield. Thus, the TBDPS groups of compounds 18 and 19 were deprotected using HF·pyridine in THF and oxidation of the resulting hydroxyl groups with TEMPO, NaOCl followed by methylation, and finally removal of levulinate afforded disaccharides 24 and 25 in 45% and 77% yield respectively. For the one-pot pentasaccharide synthesis (Scheme 5), azidoglucosyl donor 16 (RRV = 53.7) was first coupled with disaccharide acceptor 24 (RRV = 18.2), and then α-methyl disaccharide acceptor 25 was added to the reaction mixture. Under these conditions the fully protected pentasaccharide 26 was obtained in 20% yield. The corresponding O-sulfates, were obtained by consecutive saponification with LiOOH and O-sulfation with triethylamine-sulfur trioxide followed by palladium catalyzed hydrogenolysis and N-sulfation with pyridine-sulfur trioxide to provide the desired heparin pentasaccharide 27. It is noted however that selective deprotection of the acetyl group, the benzoyl group, the methyl ester group and the benzyl group can be carried out with known procedures to create different sulfation patterns.

Scheme 5.

One-pot synthesis of pentasaccharide derivative 27a

aReagents and conditions: (a) i. HF·Pyr, THF; ii. TEMPO, KBr, NaOCl, CH2Cl2, H2O, then MeI, KHCO3, DMF; iii. NH2NH2/AcOH/Pyridine, 24: 45%, 25: 77%; (b) i. NIS, TfOH, CH2Cl2, -45°C to room temperature; ii. NIS, TfOH, CH2Cl2, -45°C to room temperature, 20%; c) i. LiOOH, THF; ii. Et3N·SO3, DMF; ii. H2, Pd/C; iv- Pyr·SO3, H2O, 33%.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a one-pot strategy for the synthesis of heparin-like oligosaccharides. Carefully designed monosaccharide building blocks (e.g., 5, 10, 15 and 16) with well defined reactivity were successfully used in the representative one-pot synthesis of disaccharides 17, 18, tetrasaccharide 23 and pentasaccharide 26. No self coupling of the building blocks was observed in each case, illustrating the importance of quantitative reactivity determination for the implementation of programmable one-pot synthesis. Heparin pentasaccharide derivative 27 was obtained after global deprotection and sulfation. We believe that this new strategy has potential for rapid synthesis of various heparin analogs for the study of their biological properties.

Supplementary Material

Full experimental and characterization details for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank to the NIH for support of this work.

References

- 1.(a) Comper WD. Heparin and Related Polysaccharides. Vol. 1. Gordon and Breach; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]; (b) Linhardt RJ, Toida T. In: Carbohydrates as Drugs. Witczak Z, Nieforth K, editors. Dekker; New York: 1998. pp. 277–341. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Kjellen L, Lindahl U. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Conrad HE. Heparin Binding Proteins. Academic Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]; (c) Capila I, Linhardt RJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:390. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<390::aid-anie390>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Koshida S, Suda Y, Sobel M, Ormsby J, Kusumoto S. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:3127. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Driguez PA, Jaurand G, Herault JP, Lormeau JC, van Boeckel CAA, Herbert JM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:3009. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981116)37:21<3009::AID-ANIE3009>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Petitou M, Herault JP, Bernat A, Driguez PA, Duchaussoy P, Lormeau JC, Herbert JM. Nature. 1999;398:417. doi: 10.1038/18877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Jacquinet JC, Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Lederman I, Choay J, Torri G, Sinay P. Carbohydr Res. 1984;130:221. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sinay P, Jacquinet JC, Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Lederman I, Choay J, Torri G. Carbohydr Res. 1984;132:C5. [Google Scholar]; (c) Van Boeckel CAA, Beetz T, Vos JN, De Jong AJM, Van Aelst SF, Van den Bosch RH, Mertens JMR, Van der Vlugt FA. Carbohydr Res. 1985;4:293. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ichikawa Y, Monden R, Kuzuhara H. Carbohydr Res. 1988;172:37. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poletti L, Lay L. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:2999. and the references therein Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.013. and the references therein Orgueira HA, Bartolozzi A, Schell P, Litiens REJN, Palmacci ER, Seeberger PH. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:140. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390009.Haller MF, Boons GJ. Eur J Org Chem. 2002:2033.de Paz JL, Ojeda R, Erichardt N, Martin-Lomas M. Eur J Org Chem. 2003;68:3308.Yu HY, Furukawa JI, Ikeda T, Wong CH. Org Lett. 2004;6:723. doi: 10.1021/ol036390m.Lee JC, Lu XA, Kulkarni SS, Wen YS, Hung SC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:476. doi: 10.1021/ja038244h.Codee JDC, Stubba B, Schiattarella M, Overkleeft HS, van Boeckel CAA, van Boom JH, van der Marel GA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3767. doi: 10.1021/ja045613g.Zhou Y, Lin F, Chen J, Yu B. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:1619. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.02.020.Lu LD, Shie CR, Kulkarni SS, Pan GR, Lu XA, Hung SC. Org Lett. 2006;8:5995. doi: 10.1021/ol062464t.

- 6.(a) Fan RH, Achkar JMHT, Wei A. Org Lett. 2005;7:5095. doi: 10.1021/ol052130o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) de Paz JL, Noti C, Seeberger PH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2766. doi: 10.1021/ja057584v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Noti C, de Paz JL, Polito L, Seeberger PH. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:8664. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gama CI, Tully SE, Sotogaku N, Clark PM, Rawat M, Vaidehi N, Gaddard WA, III, Nishi A, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Nature Chem Biol. 2006;2:467. doi: 10.1038/nchembio810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Zhang Z, Ollmann IR, Ye XS, Wischnat R, Baasov T, Wong CH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:734. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mong TKK, Lee HK, Duron SG, Wong CH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Duron SG, Polat T, Wong CH. Org Lett. 2004;6:839. doi: 10.1021/ol0400084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Oscarson S. In: Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology. Ernst B, Hart GW, Sinay P, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]; (b) Codee JDC, Litjens REJN, van den Bos LJ, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34:769. doi: 10.1039/b417138c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Tabeur C, Machetto F, Mallet JM, Duchaussoy P, Petitou M, Sinay P. Carbohydr Res. 1996;281:253. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(95)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Krog-Jensen C, Oscarson S. Carbohydr Res. 1998;308:287. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Kovensky J, Duchaussoy P, Bono F, Salmivirta M, Sizun P, Herbert JM, Petitou M, Sinay P. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7:1567. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Haller M, Boons GJ. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 2001;814 [Google Scholar]; (c) Ichikawa Y, Monden R, Kuzuhara H. Carbohydr Res. 1988;172:37. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) van Boeckel CAA, Beetz T, Vos JN, de Jong AJM, van Aelst SF, van den Bosch RH, Mertens JMR, van der Vlugt FA. J Carbohydr Chem. 1985;4:293. [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Pozsgay V. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6673. [Google Scholar]; b) Baptistella LHB, dos Santos JF, Ballobio KC, Marsaioli AJ. Synthesis. 1989:436. [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Boeckel CAA, Beetz T, Vos JN, de Jong AJM, van Aelst SF, van den Bosch RH, Mertens JMR, van der Vlugt FA. J Carbohydr Chem. 1985;4:293. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JC, Greenberg WA, Wong CH. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:3143. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeo K, Kitamura S, Murata Y. Carbohydr Res. 1992;224:111. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)84098-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Yu HN, Ling CC, Bundle DR. Can J Chem. 2002;80:1131. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bazin HG, Du Y, Polat T, Linhardt RJ. J Org Chem. 1999;64:7254. doi: 10.1021/jo981477k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Full experimental and characterization details for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.