Abstract

Pregnancy related compressive myelopathy secondary to vertebral hemangioma is a rare occurrence and its treatment antepartum is rare. We report a 22-year-old lady in her 26th-week of pregnancy who was treated in two stages––antepartum with a laminectomy and posterior stabilization. This resulted in complete recovery of the neurological deficits. She delivered a normal baby after 3 months, following which a corpectomy and fusion was performed. This two-staged approach appears safe and effective in treating symptomatic vertebral haemangiomas causing neurological deficits during pregnancy. A review of relevant literature has been done.

Keywords: Vertebral hemangioma, Pregnancy, Instrumentation, Antepartum treatment

Introduction

Hemangiomas of bone are localized benign tumors composed of fully developed adult blood vessels [5]. Vertebral hemangiomas are present without symptoms in approximately 10% of the population [13, 16] more common in women, usually located in the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebra, and are often multifocal [5]. Infrequently these benign lesions may cause local or radicular pain and neurological deficits ranging from myeloradiculopathy to paralysis [1]. In particular, pregnancy is a well-recognized condition during which vertebral hemangiomas may become clinically significant. A review of literature excluding epidural hemangiomas and histological variants such as angiosarcomas and angiolipomas are revealed in 15 reported [1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 11, 15, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25–28] cases of vertebral hemangiomas complicated by pregnancy of which only eight cases had been treated for antepartum. This report describes a case that was treated by a two-staged surgical procedure and reviews relevant literature.

Case report

A 22-year-old lady presented in the 26th-week of her first gestation with an 8 day history of difficulty in walking due to impaired balance and rapidly progressive weakness of the lower limbs. She was unable to stand without assistance. She did not have any back pain or constitutional symptoms. Although there was difficulty in initiating micturation, there was no bladder and bowel incontinence.

There was no spinal deformity or tenderness. Root tension signs were negative. Higher mental functions and cranial nerves were normal. There was spasticity of both lower limbs and power grade was 1–2 in the hips, knees and ankle (Medical Research Council scale). Knee jerks were exaggerated bilaterally with ankle clonus and positive Babinski’s sign. Abdomen reflex was present. There was loss of position sense in the toes with patchy sensory loss in the lower limbs. There were no neurological deficits in the upper limbs. Abdominal examination showed a single live fetus of 26 weeks size corresponding to gestational age. General and systemic examination was normal.

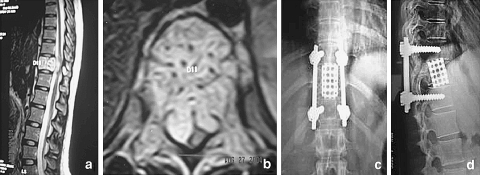

The X-ray showed an expansile lesion of D11 corpus extending to the pedicles with canal compromise without collapse. Keeping her pregnancy in mind an MRI was done, which showed features suggestive of a hemangioma involving the whole of the vertebral body with severe compression of the cord by a soft tissue mass and hemorrhage (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

a, b Preoperative MRI scan: Showing expansion of the body, pedicles and transverse process of 11th thoracic vertebrae with an anterolateral epidural soft tissue component causing gross compression of the spinal cord. c, d Two years postoperative radiographs: pedicle screw instrumentation and reconstructive cage in situ, with no evidence of tumour recurrence

The accepted norm is to delay intervention until a viable fetus can be delivered, as surgery can precipitate premature labor. However, we decompressed the cord immediately as the neurological deficit was progressive. Waiting for further 6–8 weeks for the fetus to achieve a viable status would risk neurological deterioration.

Embolization with anterior decompression and fusion was ideally required. Embolization was avoided due to pregnancy. We decided on a less invasive posterior decompression and short segment instrumentation on the premise that a laminectomy would achieve the necessary decompression of the cord without risk of abortion which was higher with an anterior decompression. It would also allow for evacuation of the hemorrhage and partial decompression of the tumor from the postero-lateral side. A review of relevant literature [2, 18, 21, 26] revealed that pregnancy related vertebral hemangiomas with neurological deficits treated antepartum by laminectomy alone had good to excellent neurological recovery.

With an Obstetrician on stand by and continuous fetal heart monitoring, under general anesthesia a laminectomy of T11 was performed. The tumor was found to be compressing the cord antero-laterally. Without retracting the cord the hemorrhage was evacuated, a part of the tumor compressing the cord antero-laterally was excised piece meal and the dura completely decompressed. Profuse bleeding was encountered during the procedure which was controlled with bone wax and surgicel packing. The spine was stabilized with pedicle screw instrumentation in T10 and T12. There was improvement in muscle power by one grade within a week of surgery and she went on to have complete recovery in 5 weeks, without residual spasticity. Twelve weeks postoperatively she delivered a full term normal baby.

Nine months later the patient developed pain in the middle of the back. Clinical examination revealed intact neurology, but a repeat MRI showed expansion of the lesion. An embolization followed by an anterior corpectomy and fusion with a titanium cage was performed (Fig. 1c, d). At 28 months follow up the patient is asymptomatic with no residual neurological deficits.

Discussion

Vertebral hemangiomas were first described by Virchow [29]. Hammes[13] and Junghanns [16] documented that 10% of the population had asymptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. The typical radiological appearance of vertical striations was described by Perman [24]. The first case of pregnancy related hemangioma was reported in 1927 by Balado [9].

There are few cases of pregnancy related vertebral hemangiomas in literature. Majority of them presented during the third trimester and the rest during the second trimester. Contrary to their usual location in the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in non-pregnant patients, pregnancy related vertebral hemangiomas occur more frequently in the upper thoracic levels [18]. Patients may experience improvement in the immediate postpartum period, only to have symptoms recur in a subsequent pregnancy [9]. Myelopathic symptoms appear to worsen in severity with subsequent pregnancies [14].

It is postulated that neurological symptoms may be produced by one or more of the following mechanisms: (a) expansion of an involved vertebrae leading to narrowing of the spinal canal, (b) compression fracture of involved vertebrae, (c) acute hemorrhage into the epidural space, (d) sub-periosteal growth of tumor creating an extradural mass producing compression, and (e) spinal cord ischemia caused by “steal” [2, 3, 17, 23, 26].

The physiological vascular, hemodynamic and hormonal changes in pregnancy act to enlarge a preexisting hemangioma and most of these changes peak in the third trimester. The most important contributing factor is the increase in venous pressure resulting from mechanical obstruction of blood flow from the paravertebral veins into the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus. Distension of the vascular channels due to a 30–50% increase in circulating blood volume [12, 18, 21], increased venous distensibility due to maternal production of progesterone, and the endothelial growth promoting effect of estrogen [20] are the other factors implicated. Immunohistochemical analysis done on vertebral hemangiomas has not been able to demonstrate estrogen and progesterone receptors on tumor tissue and this implicates a hemodynamic rather than a hormonal cause for disease progression [27, 28].

The typical radiological features show vertical striations and coarse thick traberculae described as “corduroy” vertebrae. Aggressive lesions may show expansion and erosion of the vertebral body. Axial computed tomography scan shows a classic “polka dot” appearance. MRI is the diagnostic procedure of choice and in pregnancy it saves the patient and fetus from ionizing radiation. The characteristic appearance is of a hyperintense mottled or “starburst” signal on T1 and T2 weighted images. Extradural component and hemorrhage is also visualized.

Surgery, radiotherapy [7], embolization [6], and various combinations of these have been used in the treatment of symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas. More recently vertebroplasty has been used in the treatment of symptomatic vertebral hemangiomas [8, 10]. Pregnancy is a relative contraindication to radiotherapy. Embolization is not risk free especially during pregnancy, and complications include vascular injury and radiation exposure to the fetus during fluoroscopy [15]. No cases of antepartum embolization or vertebroplasty for vertebral hemangioma have been reported. The treatment of spinal cord compression due to vertebral hemangioma during pregnancy is undoubtedly surgical. Surgery allows for direct decompression of the cord and if required, instrumentation of the spine. Profuse bleeding may occur during decompression.

The timing of surgery in cases diagnosed antepartum is controversial, as many patients show spontaneous remission after delivery [1, 4, 9, 11, 17, 22]. However the symptoms do not disappear completely [22, 25–27] or often can recur [9, 17], requiring surgery at a later time. The accepted norm is to delay intervention until a viable fetus can be delivered should premature labor occur [18]. But in the presence of progressive neurological deficits, decompression is essential at the earliest to achieve an optimal outcome especially in those cases that present in the second trimester or early third trimester. The treatment algorithm proposed by Chi et al. based on the duration of pregnancy and status of neurology is useful in planning treatment in these cases. Patients at 36 weeks of gestation or later, are observed, if neurological function deteriorates, one can consider induction of delivery followed by appropriate management of the tumor. Between 32 and 36 weeks of gestation, expectant observation is considered; surgery is reserved for severe cases of paraplegia. For patients in whom gestation is earlier than 32 weeks, prepartum surgical treatment should be considered for those who are severely symptomatic [15].

As the majority of the vertebral hemangiomas involve the body resulting in anterior and anterolateral spinal cord compression, embolization followed by decompression and fusion through an anterior approach is ideal. This extensive procedure is seldom done due to the high risk of premature labor. Laminectomy provides adequate decompression and allows for neurological recovery [2, 18, 21, 26], so a two stage approach of laminectomy antepartum and anterior procedure postpartum is a viable treatment option. Posterior stabilization is not required routinely, but should be considered if the tumor have caused significant destruction of the anterior structure.

A review of literature showed that eight patients underwent surgery antepartum. Six patients had a laminectomy and two had a vertebrectomy and fusion. Except two [11, 22] all the patients treated with laminectomy had a good to excellent outcome. The two patients who underwent vertebrectomy also had an excellent outcome. Information on the patients, treatment and fetal survival is seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vertebral hemangiomas symptomatic during pregnancy treated antepartum

| Author | Age (years) | Trimester at first symptoms | Location | Treatment/maternal outcome | Fetal outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guthkelch (1948) | 34 | 3 | T5 | Laminectomy, died early post partum | Survived |

| Askenasy (1957) | 20 | 3 | T10 | Laminectomy, pre-term labour Complete recovery |

Survived |

| Newman (1958) | 34 | 3 | T4–5 | Laminectomy, pre-term labour Died post surgery |

Survived |

| Nelson (1964) | 16 | 3 | T3 | Laminectomy and RT, pre-term labour Good recovery |

Died |

| Lavi (1986) | 25 | 3 | T4 | Laminectomy, pre-term labour Complete recovery |

Three of four survived |

| Liu (1988) | 25 | 2 | T4 | Vertebral body resection and fusion, complete recovery | Survived |

| Schwartz (1989) | 30 | 3 | T5 | Laminectomy Revision surgery for worsening symptoms Mild residual deficit |

Survived |

| Chi (2005) | 26 | 2 | C7 | Corpectomy and fusion Complete recovery |

Survived |

| Our case | 22 | 2 | T11 | Laminectomy and stabilization antepartum, corpectomy and reconstruction 9 months postpartum Complete recovery |

Survived |

T thoracic, C cervical

Our patient had rapidly progressive symptoms and at presentation had grade 1–2 power in the lower limbs with early bladder function disturbance. The MRI scan showed severe compression of the cord by the hemangioma, necessitating a decompression. A wide laminectomy and cord decompression was performed. Posterior stabilization was added as the tumor involved the whole of the vertebral body and a pathological fracture with collapse of the corpus was anticipated. She had completed neurological recovery. Anterior corpectomy and reconstruction was required 9 months postpartum as the patient developed pain in the middle of the back with out neurological deficits. Radiographs and a repeat MRI revealed expansion of the lesion and we were of the opinion that the spine was biomechanically unstable. At 28 months follow up the patient is asymptomatic.

Conclusion

The syndrome of spinal cord compression in pregnancy is rare, but when neurological deficits occur spontaneously during pregnancy enlargement of a preexisting vertebral hemangioma should be considered. The need for intervention antepartum should be guide by numerous factors, such as (1) extent of neurological deficits and progression, (2) the cause of compression as ascertained by MRI, and (3) the time duration from presentation to term. Extensive neurological involvement which is rapidly progressive due to compression should be considered for immediate decompression. This case is unique in that it is the first reported case of spinal instrumentation antepartum for the treatment of vertebral hemangioma. A two stage approach appears to be safe and effective in the treatment of these patients. Posterior stabilization should be considered after laminectomy if stability of the spinal column is compromised due to extensive vertebral involvement by the tumor.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Acquaviva R, Lhevenot C. Compression medullaire recidevante par hemangiome vertebral. Role determinant des grossesses. Maroc Med. 1957;389:924–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Askenasy H, Behmoaram A. Neurological manifestation in hemangioma of the vertebrae. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:276–284. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brobeck O. Hemangioma of vertebrae associated with compression of the spinal cord. Acta Radiol. 1950;34:235–243. doi: 10.3109/00016925009135267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David M, Constans-Lamarch JP. Compression medullaire recidevante par hemangiome extradural. Role determinant des grossesses sur les rechutes. Rev Neurol. 1952;87:638–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorfman HD, Stainer GE, Jaffe HL. Vascular tumors of bone. Hum Pathol. 1971;2:349–376. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(71)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esparza J, Castro S, Portillo JM, Roger R. Vertebral hemangiomas: spinal angiography and preoperative embolization. Surg Neurol. 1978;l10:171–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faria SL, Schlupp WR, Chiminazze H., Jr Radiotherapy in the treatment of vertebral hemangiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1985;11:387–390. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(85)90162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feydy A, Cognard C, Miaux Y, et al. Acrylic vertebroplasty in symptomatic cervical vertebral haemangiomas: report of 2 cases. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:389–391. doi: 10.1007/BF00596600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fields WS, Jones JR. Spinal epidural hemangioma in pregnancy. Neurology. 1957;7:825–841. doi: 10.1212/wnl.7.12.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gangi A, Guth S, Imbert JP, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: indications, technique, and results. Radiographics. 2003;23:e10. doi: 10.1148/rg.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guthkelch AN. Hemangiomas involving the spinal epidural space. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1948;11:199–210. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.11.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hacker NF, Moore JG. Essentials of obstetrics and gynecology. Toronto: W.B.Saunders; 1986. pp. 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammes EM. Cavernous hemangiomas of the vertebrae. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1993;29:330–333. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hytten FE, Paintin DB. Increase in plasma volume during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1963;70:402. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1963.tb04922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi JH, Manley GT, Chou D. Pregnancy related vertebral hemangioma. Case report, review of literature, management algorithm. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(3):E7. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junghanns H. Hamangiom des drie brustwir-belkorpers mit Ruckenmark-kompression. Arch Klin Chir. 1932;169:321–330. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam RH, Rhoulac GE, Erwin HJ. Hemangioma of the spinal canal and pregnancy. J Neurosurg. 1951;8:668–671. doi: 10.3171/jns.1951.8.6.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavi E, Jamieson D, Grant M. Epidural hemangiomas during pregnancy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:709–712. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.6.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu CL, Yang DJ. Paraplegia due to vertebral hemangeomas during pregnancy. A case report. Spine. 1988;13:107–108. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198801000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mealey J, Carter JE. Spinal cord tumor during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1968;32:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson DA. Spinal cord compression due to vertebral angiomas during pregnancy. Arch Neurol. 1964;11:408–413. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1964.00460220070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman MJD. Spinal angeoma with symptoms in pregnancy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1958;21:38–41. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.21.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padovani R, Poppi M, Pozzati E, Jognetti F. Spinal epidural hemangiomas. Spine. 1981;6:336–340. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perman E. On hemangeomata in the spinal column. Acta Chir Scand. 1926;61:91–105. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redekop GJ, Mastero RF. Vertebral hemangioma causing spinal cord compression during pregnancy. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:210–215. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90171-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz DA, Nair S, Hershey B, et al. Vertebral arch hemangioma producing spinal cord compression in pregnancy––diagnosis by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 1989;14:888–890. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198908000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tekkok IH, Acikgoz B, Saglam S, et al. Vertebral hemangioma symptomatic during pregnancy: report of a case and review of literature. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:302–306. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199302000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theodore HS, Hanina H, Charles JR. Estrogen and progesterone receptor negative T11 vertebral hemangioma presenting as a postpartum compression fracture: case report and management. Neurosurgery. 2000;46(1):218–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virchow R. Die krankhaften Geschwulste, vol 3. Berlin: A Hirschwald; 1867. [Google Scholar]