Abstract

Marjolin’s ulcer is a squamous cell carcinoma that develops in posttraumatic scars and chronic wounds. It was first noted to be associated with chronic osteomyelitis in 1835 and is usually described occurring in lower extremity wounds. Suspicion of such lesions should be raised in chronic wounds demonstrating characteristic changes. Impaired immunologic activity in chronic wounds has also been shown to contribute to the pathologic process. Definitive treatment in the past has been amputation proximal to the tumor, however; recently, wide resection and radiation therapy have been used. According to Lifeso et al., wide local excision is unreliable and they recommend amputation in grade II or III disease and wide local excision in very small lesions that can be radically excised or in grade I lesions. We report a case of a Marjolin ulcer that developed at the elbow. Physicians should have a high index of suspicion in chronic wounds that are recalcitrant to therapy and should remember to biopsy all suspected lesions. Early recognition and definitive treatment are the mainstays ensuring the best prognosis.

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma is a tumor of epidermal origin. A “Marjolin ulcer” is identified as a squamous cell carcinoma that develops in posttraumatic scars and chronic wounds. It has been well documented that it was first described by Jean Nicholas Marjolin in 1828, and then Hawkins reported in 1835 a case of squamous cell carcinoma that appeared to have originated from a site of chronic osteomyelitis [2, 9, 13, 15, 17–19, 25, 26, 32]. Although well described [1–32], squamous cell carcinoma consistent with the diagnosis of a Marjolin’s type is an uncommon entity. Its incidence ranges from 0.23% to 1.7% [26, 31]. Cases of chronic osteomyelitis that may develop into squamous cell carcinoma have an incidence range of 0.2–1.7% [2, 26, 31]. It most often occurs in Caucasian males, age range 18–40 years. The average reported duration of osteomyelitis before the development of the squamous cell carcinoma is 27–30 years, but ranges from 18 to 72 years. Mean latency period is 30.5 years.

Most of the literature regarding malignant tumors, such as squamous cell carcinoma, arising from chronic wounds or scar tissue has been documented in the lower extremities with a 50% occurrence in the tibia [28]. Vishniavsky [29], in a review of the reported cases until 1966, noted 112 cases of squamous cell carcinoma developing from chronic sinus tracts associated with osteomyelitis.

Two cases of a squamous cell carcinoma of the humeral shaft have been reported [14, 31]. To our knowledge, there has not been a report describing squamous cell carcinoma arising from the elbow joint.

Case Report

The patient is a 60-year-old, right-hand-dominant male who suffered a motorcycle accident in the 10 years prior to admission. At the time of initial injury, he sustained a large soft tissue “road rash” injury to his right elbow area that according to the patient went to the elbow joint. There were no fractures of the osseous structures at the elbow. During the ensuing years he stated that he continued to have a chronic wound, which he cared for at home using daily dressing changes. He was seen numerous times at different facilities for this chronic persistent wound. After several years of such treatment he stated that he developed an infection and area of chronic ulceration. He had been on multiple antibiotic regimens as both an outpatient and inpatient. He was diagnosed with chronic osteomyelitis and had completed a 6-week course of antibiotics. However, his follow-up in the clinics was often inconsistent.

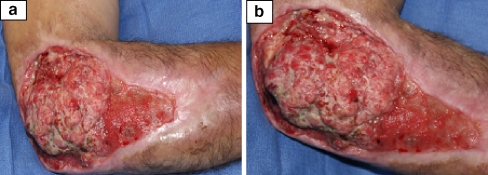

He presented to the our institution’s orthopedic infection clinic in July 2005 with an enlarging fungating mass for that he said had increased in size during the past 2 months. His pain level had increased tremendously and now the pain was not localized to the elbow area but also radiated to his forearm and hand. He also noted the wound had a foul smell and had increased drainage. He presumed it to be part of the infection and had continued silver sulfadine dressings at home. His past medical history included hepatitis B and C, hypertension, and history if intravenous drug abuse. The patient admitted to frequent self-injections of illicit drugs into his right elbow wound as a “site of convenience.” Physical examination revealed a well-nourished but disheveled appearing man. He was afebrile. There was a large 14 × 18 cm wound over the lateral border of his right elbow with irregularly shaped hypertrophic edges (Fig. 1a,b). There was foul-smelling, seropurulent drainage coming from the fungating mass. He had decreased range of motion secondary to pain and the thick tissue edges of the soft tissue mass that prevented full elbow flexion and extension. His neurovascular exam was intact. He had no axillary lymphadenopathy. Laboratory analysis revealed his WBC was normal, ESR 69 and CRP 6.3. He was initially admitted for wound care and intravenous antibiotics. Cultures grew out Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the patient was started on Imipenem per Infectious Disease staff. The attending hand surgeon suggested biopsy of the soft tissue lesion at multiple sites and depth prior to extensive debridement and wound coverage based on a presumptive diagnosis of possible malignancy.

Figure 1.

(a, b) Right elbow wound. Photographs courtesy of Milan V. Stevanovic, M.D.

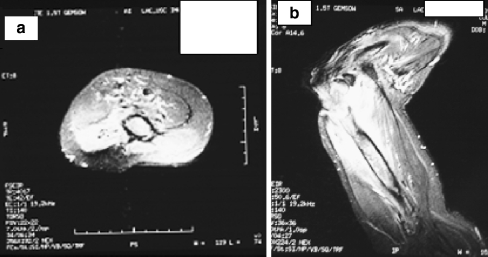

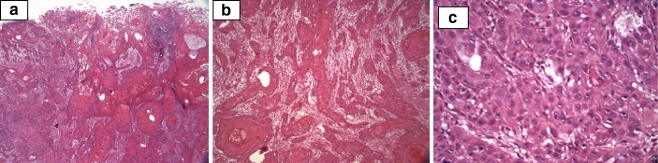

Radiographs of the right elbow showed gross destruction of the elbow joint with periosteal changes in the distal humerus and proximal radius and ulna (Fig. 2). A large soft mass was also evident. Magnetic resonance imaging showed this large, soft tissue mass and osteomyelitis of the distal humerus and proximal forearm (Fig. 3a,b). Decreased signal was evident on the T1-weighted images of the distal humerus and proximal forearm and increased signal on the T2-weighted images consistent with osteomyelitis. There was uniform signal intensity enhancement of the periosteum, mass, and adjacent medullary bone. Biopsy results were consistent with squamous cell carcinoma, large keratinizing type, moderately differentiated (Fig. 4a–c).

Figure 2.

Right elbow radiograph lateral view. Soft tissue swelling, bony involvement, periosteal changes evident.

Figure 3.

(a, b) MRI axial and sagittal views showing soft tissue edema and medullary canal signal increases.

Figure 4.

(a, b, c) Histology: low, intermediate, and high magnification showing typical squamous cells.

Staging chest CT scan was also carried out which showed no lesions.

After presentation to the tumor service, the treatment recommendation was for surgical amputation at the midshaft of the humerus (Fig. 5). His postoperative course was benign. Five months postoperative is currently doing well and his pain has resolved.

Figure 5.

Postoperative picture showing above elbow amputation.

Discussion

Suspicion should be raised for a malignant process such as squamous cell carcinoma when there are certain characteristic changes in chronic wounds. These include foul odor, change in drainage or an increase in drainage, enlarging or exophytic mass, increase in pain, continued unresponsiveness to therapy, lymphadenopathy, hemorrhage, progressive bone destruction on radiographs, or recalcitrant lesion.

Visuthikosol et al. [30] hypothesized that scar tissue has impaired immunologic reactivity to tumor cells compared to normal skin. Lymphatics are obliterated in scar tissue, which could delay deliver of tumor-specific antigen to regional nodes delaying the host response. Hammond et al. [10] proposed that rapidly proliferation in cells with poor blood supply have increased susceptibility to carcinogen. Gillis and Lee [8] found that the duration of osteomyelitis is a more important factor leading to squamous cell carcinoma than age of patient. They stated that at least 20 years is necessary for malignant changes to occur.

Cultures can help assist with choosing an antimicrobial regimen; however, they are not effective in the diagnosis or treatment of a malignancy. Manale and Brower [22] studied bacterial flora in 10 patients whose initial diagnosis was Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. However, most did not grow S. aureus when squamous cell carcinoma was diagnosed. Therefore the theory is that malignancy limits S. aureus proliferation.

Plain roentgenograms may be difficult to discern osseous changes related to previous trauma or osteomyelitis versus adjacent or invasive tumor [19]. This can often lead to a delay in diagnosis and subsequently treatment.

Confirmation of malignancy is performed by biopsy, which can be performed bedside. Biopsies of multiple sites and depth should be taken. Failure to biopsy at multiple sites and depths can result in false-negative biopsy results and again cause delay in diagnosis [11].

Early reports found other tumors to be associated with osteomyelitis including basal cell, adenocarcinoma, myeloma, fibroblastic osteosarcoma, angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, reticulosarcoma, and B-cell lymphoma [1, 4, 7, 12, 16].

Definitive treatment should include amputation proximal to tumor. This has been the treatment of choice in the past. Current therapy may now alternatively offer wide excision with radiation therapy. McGrory et al. [23] reported that six of 41 patients with malignant tumor who underwent amputation had local recurrence. The actual margin distance could not be discerned. They suggest wide removal of the tumor aided by CT or MR imaging to identify appropriate surgical margins. Eroglu and Camlibel [6] found reviewed 91 patients with squamous cell carcinoma who underwent primary curative surgery. They found no difference in risks of local or regional recurrence whether wide local excision or extremity amputation was performed. However, those with larger tumor initially tended to have a higher recurrence rate.

Goldberg and Arbesfeld [9] reported Mohs micrographic surgery in 1991 in calcaneal osteomyelitis leading to squamous cell carcinoma. They reported on a patient who refused amputation and failed radiation therapy. He was treated with Mohs surgery and had good response. Cure rates, however, have still not been compared with amputation.

Enneking et al. [5] recommended that for surgical planning, musculoskeletal neoplasms should be divided into two grades: low grade and high grade. Squamous cell carcinomas complicating osteomyelitis are usually of low-grade malignancy [9]. Prognosis depends on grading. Lifeso et al. [19] studied 63 patients with squamous cell carcinoma from scar in chronic osteomyelitis. They found worsening prognosis with higher lesion grades; thus they recommend the following treatment algorithm. They studied grade I (low grade), grade II (moderately well differentiated), and grade III (poorly differentiated) lesions. In grade I lesions, treatment is with wide local excision. In grade II and III lesions, treatment consists of amputation. Irradiation of local nodes should occur even if there are no node metastases. There is a significant decrease in metastasis with prophylactic node irradiation. Those patients with no nodal irradiation had a 24% chance of subsequently developing metastasis.

In 1976 Fitzgerald [7] stated that regional lymphadenectomy is not necessary because most nodes are enlarged due to inflammation. However, if nodes remain enlarged for more than 3 months postoperative, biopsy should be performed. Eroglu and Camlibel [6] found no significant correlation between prophylactic lymph node dissection and recurrence regardless of tumor grade or primary lesion size. They found that nodal biopsy should be performed if the patient has suspicious lymph nodes and that lymph node dissection should be carried out if histology confirms nodal metastases.

Rates of metastasis range from 20% to 35% in those treated with amputation. Sedlin and Fleming [28], after studying 102 cases, found regional or visceral metastases in 22 patients of whom only 3 lived. They showed that the tumors metastasized early and if patients survived 3 years without metastasis, they have a good prognosis. Luce [20] found that 95% who present with metastasis would do so in the first 12 months.

It is important to consider malignancy in intractable nonhealing lesions. Although rare, malignancy such as squamous cell carcinoma can occur in the setting of presumed isolated infections. Physicians should have a high index of suspicion in chronic wounds that are recalcitrant to therapy and should remember to biopsy all suspected lesions. Early recognition and definitive treatment should be the mainstay to ensure the best prognosis.

References

- 1.Akbarnia BA, Wirth CR, Colman N. Fibrosarcoma arising from chronic osteomyelitis. J Bone Jt Surg 1976;58-A(1):123–5. [PubMed]

- 2.Altay M, Arikan M, Yildiz Y, Saglik Y. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic osteomyelitis in foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2004;25(11):805–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Coy J. Combat injury with chronic osteomyelitis complicated by squamous cell carcinoma. Mil Med 1994;159:665–7. [PubMed]

- 4.Denham RH, Dingley AF. Fibrosarcoma occurring in a draining sinus. J Bone Jt Surg 1963;45-A(2):384–6.

- 5.Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcomas. Clin Orthop 1980;153:106–20. [PubMed]

- 6.Eroglu A, Camlibel S. Risk factors for locoregional recurrence of scar carcinoma. Br J Surg 1997;84(12):1744–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fitzgerald RH, Brewer NS, Dahlin DC. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating chronic osteomyelitis. J Bone Jt Surg 1976;58-A(8):1146–8. [PubMed]

- 8.Gillis L, Lee S. Cancer as a sequel to war wounds. J Bone Jt Surg 1951;33B:167–79. [PubMed]

- 9.Goldberg DJ, Arbesfeld D. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a site of chronic osteomyelitis: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. J Dermatologic Surgical Oncology 1991;17:788–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hammond J, Thomsen S, Ward G. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma 1987;27(6):681–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hejna W. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in the chronic sinuses of osteomyelitis. Cancer 1965;18(1):128–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Henderson MS, Swart HA. Chronic osteomyelitis associated with malignancy. J Bone Jt Surg 1936;18:56–60.

- 13.Hensel KS, Ono CM, Doukas WC. Squamous cell carcinoma in chronic ulcerative lesions: a case report and literature review. Am J Orthop 1999. 4:253–6. [PubMed]

- 14.Horn CV, Templeton AC. Carcinoma developing in a drainage sinus of chronic osteomyelitis of the humerus. Br J Surg 1971;58(5);399–400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Inglis AM, Morton KS, Lehmann ECH. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic osteomyelitis. Can J Surg 1979;22(3):271–3. [PubMed]

- 16.Johnston RM, Miles JS. Sarcomas arising from chronic osteomyelitic sinuses. J Bone Jt Surg 1973;55-A(1):162–8. [PubMed]

- 17.Leis SB, Bayne O, Karlin JM, Scurran BL, Reiner M. Squamous cell carcinoma: an unusual early complication of postoperative osteomyelitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 1993;33(1):21–7. [PubMed]

- 18.Lifeso RM, Bull CA. Squamous cell carcinoma of the extremities. Cancer 1985;55:2862–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lifeso RM, Rooney RJ, El-Shaker M. Posttraumatic squamous cell carcinoma. J Bone Jt Surg 1990;72-A(1):12–8. [PubMed]

- 20.Luce E. Malignant epithelial tumors of the lower extremity—part I: basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Contemp Orthop 1986;12(6):31–9.

- 21.Luchs JS, Hines J, Katz DS, Athanasian EA. MR imaging of squamous cell carcinoma complicating chronic osteomyelitis of the femur. Am J Radiol 2002;178:512–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Manale BL, Brower TD. The significance of bacterial flora in carcinoma in chronic osteomyelitis. 1973;136:63–4. [PubMed]

- 23.McGrory JE, Pritchard DJ, Unni KK, Ilstrup D, Rowland CM. Malignant lesions arising in chronic osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop 1999;362:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Morris JM, Lucas DB. Fibrosarcoma within a sinus tract of chronic draining osteomyelitis. J Bone Jt Surg 1964;46-A(4):853–7. [PubMed]

- 25.Noonan KJ, Goetz DD, Marsh JL, Peterson KK. Rapidly destructive squamous cell carcinoma as a complication of chronic osteomyelitis. Orthop 1993;16(10):1140–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Patel NM, Weiner SD, Senior M. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic osteomyelitis of the patella. Orthoblue J 2002;25:334–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Saglik Y, Arikan M, Altay M, Yildiz Y. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic osteomyelitis. Int Orthop 2001;25:389–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Sedlin ED, Fleming JL. Epidermoid carcinoma arising in chronic osteomyelitis foci. J Bone Jt Surg 1963;45-A(4):827–38.

- 29.Vishniavsky S. Squamous cell carcinoma in sinus tract of chronic osteomyelitis. Va Med Mon 1970;97:645–50. [PubMed]

- 30.Visuthikosol V, Boonpucknavig V, Nitiqanant P. Squamous carcinoma in scars: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Plast Surg 1986;16(1):42–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Wagner RF, Grande DJ. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia vs. squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic osteomyelitis of the humerus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1986;12(6):632–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ziets RJ, Evanski PH, Lusskin R, Lee M. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating chronic osteomyelitis in a toe. A case report and review of the literature. Foot Ankle 1991;12(3):178–81. [DOI] [PubMed]