Abstract

This work presents evidence that photo-excitation of guanine cation radical (G•+) in dGpdG and DNA-oligonucleotides: TGT, TGGT, TGGGT, TTGTT, TTGGTT, TTGGTTGGTT, AGA and AGGGA in frozen glassy aqueous solutions at low temperatures leads to hole transfer to the sugar phosphate backbone and results in high yields of deoxyribose radicals. In this series of oligonucleotides we find that, G•+ on photo-excitation, at 143 K leads to the formation of predominantly C5′• and C1′• with small amounts of C3′•. Photo-conversion yields of G•+ to sugar radicals in oligonucleotides decreased as the overall chain length increased. However, for high molecular weight dsDNA (salmon testes) in frozen aqueous solutions substantial conversion of G•+ to C1′• (only) sugar radical is still found (ca. 50%). Within the cohort of sugar radicals formed we find a relative increase in the formation of C1′• with length of the oligonucleotide along with decreases in C3′• and C5′• For dsDNA in frozen solutions, only the formation of C1′• is found via photo-excitation of G•+ without a significant temperature dependence (77 K to 180 K). Long wavelength visible light (>540 nm) is observed to be about as effective as light under 540 nm for photoconversion of G•+ to sugar radicals for short oligonucleotides but gradually loses effectiveness with chain length. This wavelength dependence is attributed to base-to-base hole transfer for wavelengths >540 nm. Base-to-sugar hole transfer is suggested to dominate under 540 nm. These results may have implications for a number of investigations of hole transfer through DNA in which DNA-holes are subjected to continuous visible illumination.

Introduction

Sugar-phosphate free radicals are among the most damaging of DNA lesions as they are precursors to DNA strand breaks.1 We have found that irradiation of hydrated DNA samples with heavy-ion beams results in substantially increased amounts of sugar and phosphate backbone radicals over that found with low LET γ-irradiation.2 In these same ion beam samples we also found evidence for the C3′-dephosphorylated and phosphoryl radicals, resulting from immediate strand breaks.2 The usual mechanism suggested for formation of sugar radicals (hole deprotonation)1 c - k can neither explain production of these two sugar-radicals nor can it account for the higher yield of sugar phosphate radicals observed in high LET irradiated samples. Therefore, two new mechanisms are under serious consideration in our laboratory to explain these increases in sugar radical formation: (i) the role of low energy electrons (LEE) as a potential source of prompt strand breaks which we have suggested result in the immediate strand break radicals,3 - 12 and (ii) the role of excited states of DNA-base cation radicals.13 - 17 This study continues our efforts to understand the role of excited states in the production of DNA sugar-phosphate radicals.

In our early work with γ-irradiated DNA we found evidence suggestive of conversion of G•+ to sugar radicals at high irradiation doses.18 This led us to suggest a role for excited states of DNA base cation radicals as a source for sugar radical formation.18 The observation of relatively high yields of neutral sugar radicals in DNA irradiated with high-energy argon-ion beams, relative to that found in γ-irradiated samples, also led us to hypothesize that excited states in the densely ionized ion beam track core may lead to sugar radicals.2

In our ongoing efforts to delineate the role of involvement of excited states of one-electron oxidized base cation radicals in the formation of sugar radicals, we have already observed that photo-excitation of guanine cation radical (G•+) in aqueous (D2O) glassy systems produced primarily C5′• and C3′• (in dGuo), C5′• and C1′• (in 3′-dGMP), and predominantly C1′• (in 5′-dGMP and in the dinucleoside phosphate -TpdG).13-15 Sugar radical formation was also found by photo-excitation of one-electron oxidized adenine in deoxynucleosides and deoxynucleotides.16 Wavelengths of light from 320 to 650 nm are found to be effective.14, 16 Photo-excitation of G•+ in γ-irradiated hydrated (Γ = 12±2 D2O/nucleotide) DNA in the UVA-vis range (310-480 nm) shows conversion of G•+ to C1′• in substantial yields.14 Photoexcitation of G•+ in DNA at wavelengths above 500 nm was not effective.14 These experiments along with theoretical studies using the time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT)14 - 16 have established that excitation of one-electron oxidized purine base radical results in delocalization of a significant fraction of the spin and charge onto the sugar moiety followed by rapid deprotonation leading to the formation of a neutral sugar radical. Moreover, TD-DFT studies in TpdG15 and also in other dinucleoside phosphates17 show evidence for a competitive excitation process, base to base hole transfer which was predicted to occur at low excitation energies in stacked DNA base systems.

While, the experimental and theoretical efforts described above have established the role of hole-excited states in the sugar formation in DNA, a number of points still remain unexplained.

Why wavelengths over 500 nm are effective in sugar radical formation in the photo-excitation of G•+ in small DNA model systems but not in dsDNA.

Why photo-excitation of G•+ in dGuo results in C3′•, C5′• and C1′• but only C1′• in dsDNA?

Is the hole excitation mechanism applicable at biologically relevant temperatures?

What is the base sequence and DNA strand length dependence of the sugar radical formation process?

In this work we attempt to answer these questions through a number of experiments in which we investigate the wavelength dependence, and free radical identity and base sequence dependence on photo-excitation of G•+ in a series of DNA-oligonucleotides (noted as “oligonucleotides” in this work). We have compared the initial rates of sugar radical formation in these wavelength regions with the corresponding data in dsDNA. Also, we have carried out photo-excitation studies in dsDNA at temperatures from 77 K to 180 K which extends the temperature range for sugar radical formation. These efforts provide important answers to the questions posed.

Materials and Methods

Model compound sample preparation

The dinucleoside phosphate (monosodium salt) dGpdG, as well as Lithium chloride (99% anhydrous, SigmaUltra) were procured from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The DNA oligonucleotides TGT, TGGT, AGA - desalted and tested by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry were purchased from Synthegen, LLC. (Houston, TX). 5′-Phosphorylated and desalted 5′-p-TGGT was obtained from IDT (Coralville, IA). The remaining oligonucleotides TGGGT, TTGTT, TTGGTT, TTGGTTGGTT, AGGGA - used in this study, were all obtained from IDT with standard desalting (Coralville, IA). Potassium persulfate (crystal) was from Mallinckrodt, Inc. (Paris, KY). All were employed without further purification.

About 0.5 mg of each of the dinucleoside phosphates or 1.5 mg of each of the oligonucleotides was dissolved in 0.35 mL of 7.5 M LiCl in D2O in the presence of 2 mg K2S2O8. 13 – 16 The solutions were deoxygenated by bubbling with nitrogen and as per our earlier works. 13 – 16 The transparent glassy samples were prepared by drawing the solution into 4mm Suprasil quartz tubes (cat. no. 734-PQ-8, WILMAD Glass Co., Inc., Buena, NJ) followed by cooling to 77 K. All samples are stored at 77 K in the dark.13 – 16

DNA sample preparation

Salmon testes DNA (sodium salt, 57.3% AT and 42.7% GC, Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO)), Thallium trichloride as well as deuterium oxide (99.9 atom % D, Aldrich Chemical Company Inc. (Milwaukee, WI)) and were used without any further purification.

Ice-like samples of DNA with Tl3+, at loading (1 Tl3+/10 bp) in D2O were prepared using procedures described earlier. 14 This loading of Tl3+ thoroughly suppresses the reductive-damage pathway14 and allows observation of the formation of sugar radicals from photo-excited G•+ in DNA.13 All samples were stored at 77 K in the dark.13,14

γ-Irradiation

γ-irradiation of glassy samples of all oligonucleotides was performed using a model 109-GR 9 irradiator which contains a shielded 60Co source. A 400 ml Styrofoam dewar containing the samples under liquid nitrogen enters irradiation chamber via an elevator system that prevents exposure. Glassy samples of all the oligonucleotides containing number of bases up to 4 were γ-irradiated (60Co) with an absorbed dose of 2.5 kGy at 77 K. For glassy samples of oligonucleotides containing number of bases higher than 4, the absorbed dose was 5 kGy at 77 K. Salmon testes DNA-Tl3+ ice samples were γ-irradiated (60Co) with an absorbed dose of 15.4 kGy at 77 K as per our earlier work. 14

Annealing and illumination of samples

As mentioned in our previous works13-16, we have used a variable temperature assembly for carrying out the annealing of the samples. For monitoring the temperatures during annealing, we have used a copper-constantan thermocouple in direct contact with the sample.13 - 16 The glassy samples (7.5 M LiCl/D2O) stored at 77 K were annealed to 155 K for 10 - 20 min which results in the loss of Cl2•− with the concomitant formation of only G•+.13-16 Note that we did not observe sugar radical formation by direct attack of Cl2•− on the sugar moiety in these oligonucleosides/tides.

Photo-excitation of these glassy samples of oligonucleosides or dinucleoside phosphate, containing either the G•+ were then carried out at 143 K with a 250 W tungsten lamp with or without a cut-off filter (≤540 nm). 14, 16 The active visible light intensity at the sample was a small fraction of the total intensity (ca. 60 mW).16

Following our earlier works, γ-irradiated DNA-Tl3+ ice samples were annealed to 130 K to remove the ESR signal from •OH. 13, 14, 19, 20 The •OH is in a separate ice phase, and annealing does not result in additional DNA radicals.19, 20 These annealed samples were then illuminated using a 250 W tungsten lamp at 143 K with and without a cut-off filter (≤540 nm) and at 180 K without any filter.

Electron Spin Resonance

After γ-irradiation at 77 K, annealing to 155 K and illumination at 143 K, samples were immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen, and an ESR spectrum was recorded at 77 K and 40 dB (20 μW).14-16 After γ-irradiation at 77 K, annealing to 130 K and illumination at 143 K and at 180 K, DNA-Tl3+ ice samples were immediately immersed in liquid nitrogen, and an ESR spectrum was recorded at 77 K and 40 dB (20 μW).14 We have recorded these ESR spectra using a Varian Century Series ESR spectrometer operating at 9.2 GHz with an E-4531 dual cavity, 9-inch magnet and with a 200 mW klystron. Similar to our previous works, Fremy's salt (with g = 2.0056, AN = 13.09 G) was used for field calibration.13 - 16, 19, 20 In the case of glassy samples of oligonucleosides or dinucleoside phosphate, we have subtracted a small singlet “spike” from irradiated quartz at g = 2.0006 from spectra before analyses.14-16

Analysis of ESR spectra

The fraction that a particular radical contributes to an overall spectrum is estimated from doubly integrated areas of benchmark spectra. The doubly integrated areas are directly proportional to the number of spins of each radical species (moles of each radical). Least square fittings of benchmark spectra (Figure 1) were employed to determine the fractional composition of radicals in experimental spectra using programs (ESRPLAY, ESRADSUB) written in our laboratory.13-16

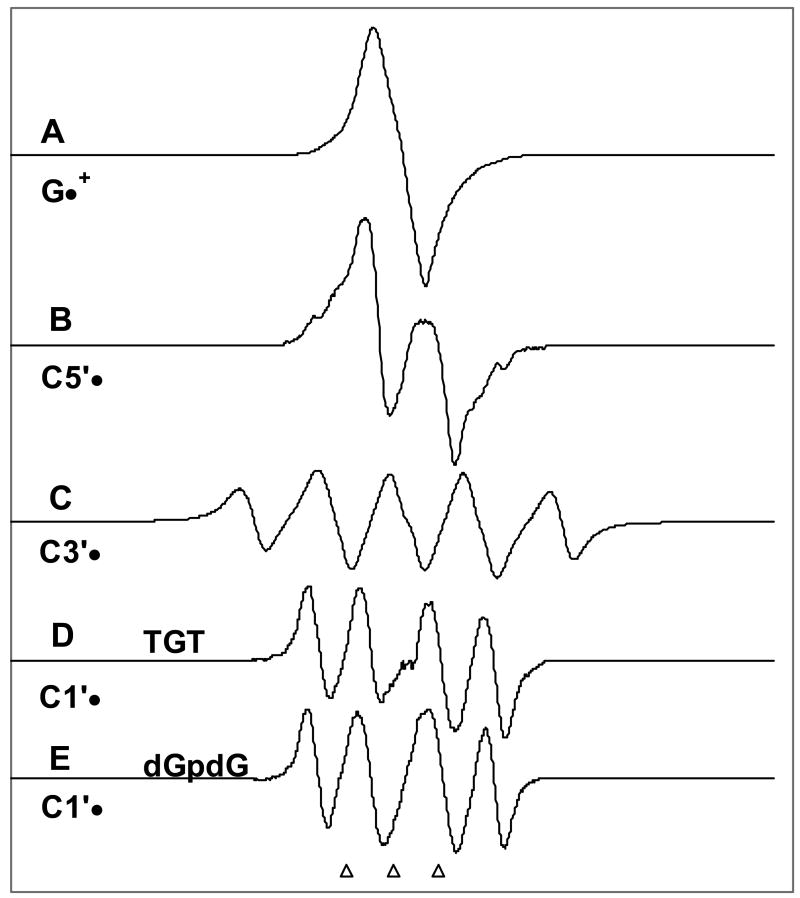

Figure 1.

Benchmark spectra used for computer analysis. (A) G•+ in dGpdG by one-electron oxidation by Cl2•– (see Figure 2A also). (B) C5′•, formed via photo-excitation of G•+ in 8-D-3′-dGMP.14 (C) C3′•, produced from G•+ in dGuo.14 (D) C1′•, produced from G•+ in TGT. (E) C1′•, produced from G•+ in dGpdG. (see supporting information Figure S1 for details regarding Figures 1D and 1E). The three reference markers in this figure and in the other figures in this work represent positions of Fremy's salt resonances (The central marker is at g = 2.0056 and each of three markers is separated from one another by 13.09 G).

The benchmark spectra for the glassy samples of dinucleoside phosphate and oligonucleotides are shown in Figure 1. These are - for G•+ from dGpdG (Figure 1A), C5′• (figure 1B) and C3′• (Figure 1C) from dGuo.14 We have used two benchmark spectra for C1′• (Figures 1D (for TGT) and 1E (for dGpdG)) because the two major hyperfine coupling constants for the two C2′-H atoms (β-proton couplings) vary slightly with compound (see supporting information Figure S1). The origin of the benchmark spectra for C1′• in TGT and dGpdG as well as hyperfine couplings and the g-values are given in supporting information Figure S1.

The spectra obtained from DNA-Tl3+ ice samples were analyzed using the benchmark spectra of the guanine cation radical (G•+), of the one-electron reduced species viz. T−•, and C(N3H)•, of a composite spectrum of neutral radicals found in low temperature irradiated DNA, and of a C1′• spectrum obtained via photo-excitation at 77 K.14

Results

Photo-excitation of one-electron-oxidized dGpdG

In Figure 2A, we show the ESR spectrum of G•+ formed in the dinucleoside phosphate – dGpdG after one-electron oxidation by Cl2•− on annealing to 155 K. This spectrum in Figure 2A is found to be identical to that of the G•+ spectrum already reported in the literature.1c-f, h-k, 13 - 15, 21, 22 The presence of G•+ in this sample is also validated by its characteristic UV-vis absorption which produces red-violet color.14 In other work we have shown that in 7.5 M LiCl (D2O) glasses at low temperatures, the proton at N1 in G•+ is still largely retained. 21

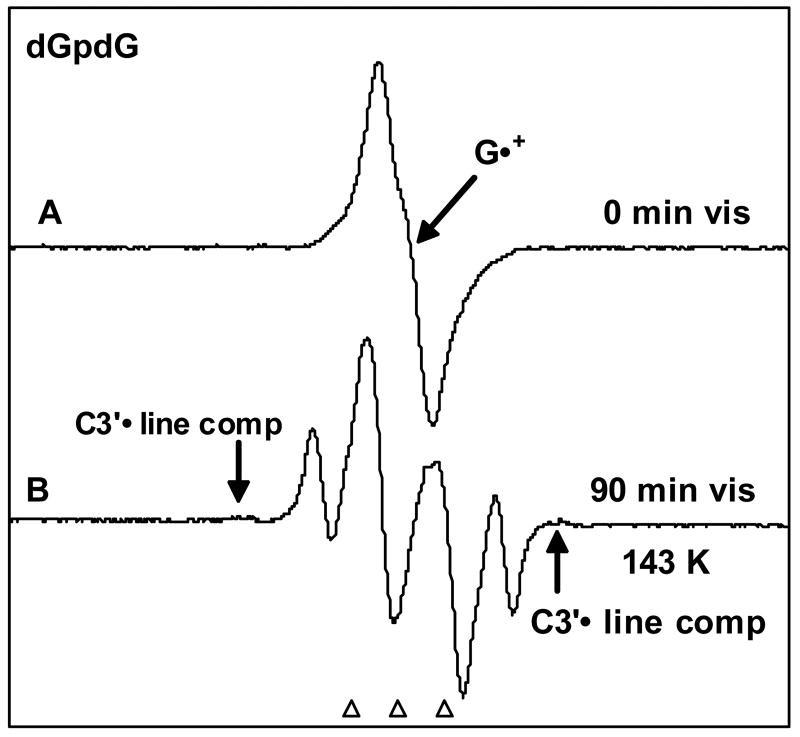

Figure 2.

(A) ESR spectrum of one-electron oxidized dGpdG (1 mg/ml) by Cl2•− attack in the presence of K2S2O8 (5 mg/ml) as an electron scavenger in 7.5 M LiCl glass / D2O. (B) Spectrum found after visible photo-excitation the sample in A for 90 min at 143 K. Nearly complete conversion of G•+ to sugar radicals is found. Analyses shows three radicals: C5′• (prominent doublet at the centre), C1′• (prominent quartet) and a very small amount of C3′• visible in the wings. All spectra were recorded at 77 K.

Figure 2B shows formation of sugar radicals after photo-excitation of G•+ at 143 K. Prominent outer line components from C1′• and an intense central ca. 19 G doublet from C5′• 14 are visible in the spectrum. We also observe, in low intensity, line components of C3′• in the wings (arrows). Analysis using the benchmark spectra shown in Figure 1 indicates that the spectrum in Figure 2B contains contributions from C1•' (33%), C5′• (53%), C3′• (4%) and a small residual amount of G•+ (ca. 10%).

Photo-excitation of one-electron oxidized DNA-oligonucleotide radicals

In Figures 3A and 3F, the ESR spectra of one-electron oxidized TGT and TTGTT are shown. These two spectra and those of one-electron oxidized TGGT, 5′-p-TGGT, TGGGT, TTGGTT and TTGGTTGGTT (see supporting information Figure S2) as well as that of one-electron oxidized AGGGA (see supporting information Figure S3) is found to be similar. Using the benchmark spectrum of G•+ in Figure 1 A, we find that the spectra in Figures 3A and 3F and those of the one-electron oxidized oligonucleotides mentioned above are all found to result predominantly from G•+.

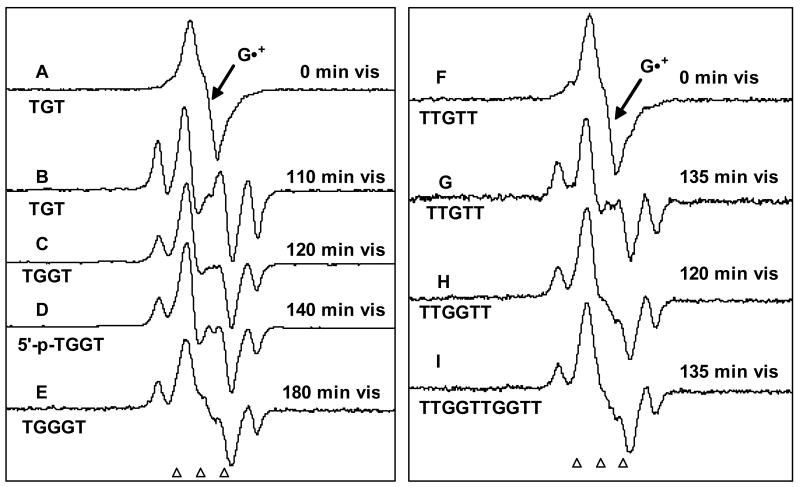

Figure 3.

ESR spectra of (A) and (F) of one-electron oxidized TGT (4.5 mg/ml) and TTGTT (4.5 mg/ml) formed by attack of Cl2•– in the presence K2S2O8 (8 mg/ml) as an electron scavenger in 7.5 M LiCl glass / D2O, in annealing to 155 K. These spectra in (A) and (F) are chiefly due to G•+. Spectra (B) – (E) and (G) – (I) are obtained after photo-excitation of G•+ in the oligonucleotides indicated with visible light at 143 K, showing considerable conversion of G•+ to sugar radicals - C5′• (prominent doublet at the centre) as well as to C1′• (prominent quartet). The samples in A and (F) are red-violet due to the absorption of G•+ whereas those in (B) – (E) and (G) – (I) are fade in color or are near colorless as conversion to sugar radical occurs. All spectra were recorded at 77 K.

While thymine is not found to be significantly oxidized in oligonucleotides containing T and G, we find that A was also oxidized in AGA and AGGGA. Using the benchmark spectrum of deprotonated one-electron oxidized adenine i.e., A(-H)• from our earlier work16 and the benchmark spectrum of G•+ in Figure 1A, we find that the spectrum of one-electron oxidized AGA (see supporting information Figure S3) is a mixture of G•+ (ca. 60%) and A(-H)• (ca. 40%). The guanine base is preferentially oxidized by Cl2•− due to its lower redox potential than adenine. 1, 21, 23

Formation of sugar radicals via photo-excitation of G•+ in oligonucleotides at 143 K is evidenced in the ESR spectra shown in Figures 3(B-E) and 3(G-I) as well as in one-electron oxidized AGA and AGGGA (see supporting information Figure S3). Prominent line components from C1′• and an intense central ca. 19 G doublet from C5′• are visible in these spectra. We do also observe small amounts of the line components of C3′• in the wings in these systems.

Analyses of the spectra shown in Figures 3(B-E) and 3(G-I) were obtained after photo-excitation using benchmark spectra (Figure 1). The percent conversion of one-electron oxidized dinucleoside monosphosphates and oligonucleotides to the sugar radicals, the initial rate of sugar radical formation, and relative percentages of various types of sugar radicals at 143 K in the presence and in absence of a cut-off filter (≤540 nm) are presented in Table 1 and are compared with the previous results obtained from samples of dGuo and its 3′- and 5′- nucleotides at 143 K as well as at 77 K.14 Initial rates shown in Table 1 represent the rate of sugar radical production during the first 20 min in %/min and are determined by analyses of the spectra for the fraction of sugar radicals produced after the initial 20 min photo-excitation.

Table 1. Sugar radicals formed via photo-excitation of one-electron oxidized dinucleoside phosphates and oligonucleotides at 143K a,b,c.

| Compound | Percent convertedd | Init. Rate (%/min) | C1′•e | C3′• e | C5′• e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No filter | ≥540 nm | |||||

| dGuof | 90 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 10 | 35 | 55 |

| 8-D-dGuof | 90 | 4.0 | - | 10 | 35 | 55 |

| 8-D-3′-dGMPf | 85 | 1.9 | - | 40 | - | 60 |

| 8-D-3′-dGMP(77 K)f | 15 | 0.08 | - | 40 | - | 60 |

| 5′-dGMPf | 95 | 4.0 | - | 95 | 5 | - |

| 5′-dGMP (77 K)f | 30 | 1.0 | - | 15 | 30 | 55 |

| TpdGg | 85 | 4.0 | - | 90 | 10 | - |

| dGpdG | 90 | 2.5 | - | 35 | 5 | 60 |

| AGA | 50 | 0.5 | - | 20 | 20 | 60 |

| TGT | 95 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 40 | 5 | 50 |

| TGGT | 75 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 30 | 10 | 60 |

| 5′-p-TGGT | 80 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 30 | 10 | 60 |

| TGGGT | 70 | 1.0 | - | 60 | - | 40 |

| AGGGAh | 80 | 1.2 | - | 10h | 20h | 30h |

| TTGTT | 75 | 0.8 | - | 50 | 10 | 40 |

| TTGGTT | 55 | 1.1 | - | 50 | 7 | 43 |

| TTGGTTGGTT | 55 | ca. 0.6 | 0.15 | 60 | - | 40 |

| dsDNA (ice) i | 40 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 100 | - | - |

Radical percentages expressed to ±10% relative error. Initial rates are based on the % G•+ converted to sugar radicals after the first 20 min of visible light exposure and should be consider as indicative of the relative rates of sugar radical formation.

All glassy samples are at the native pH of 7.5 M LiCl (ca. 5).14

All samples were illuminated at 143 K unless indicated otherwise.

Percentage of conversion of one-electron oxidized dinucleoside phosphate or oligonucleotide to sugar radicals. The total spectral intensities before and after illumination were the same, within experimental uncertainties.

Each calculated as percentage of total sugar radical concentration; these sum to 100%.

The overall spectrum obtained after photo-excitation has also an underlying unidentified spectrum (ca. 40%).

DNA (salmon testes) in a frozen aqueous (D2O) solution (ice).

Our analyses shown in Table 1 suggest the following salient points:

-

Wavelength dependence for sugar radical formation via photo-excitation of G•+:

We find that the initial rate as well as overall extent of sugar radical formation via photo-excitation of G•+ at wavelengths ≥540 nm decreases as the overall chain length increases from dGuo to TTGGTTGGTT. In dsDNA ice samples, the overall conversion of sugar radicals is slightly lower than the largest oligonucleotide and the initial rate of sugar radical formation via photo-excitation becomes negligible at wavelengths ≥540 nm.

- Effect of the sequence and length of the oligomers on the initial rate as well as overall production of sugar radicals via photo-excitation:

- Photo-excitation of G•+ in both TpdG and 5′-dGMP at 143 K are unusual as they show conversion to C1′• and C3′• sugar radicals only while all others show significant yields of C5′•. We note that the C5′• formation does occur in 5′-dGMP when photo-excitation was carried out at 77 K (see Table 1)14. This observation leads us to suggest that conformation of the sugar phosphate ring in the excited state may control the sites of deprotonation.

- Photo-excitation of G•+ in dGuo and in 8-D-dGuo shows that C8 deuterium substitution in the guanine moiety has no effect on the initial rate or on the sugar radical cohort.

- Phosphorylation at 3′- reduces the initial rate of formation of sugar radicals by a factor of two whereas at 5′- substitution does not reduce the initial rate. For example, compare the data of dGuo and 3′-dGMP as well as TpdG and TGT in Table 1 which show the factor of two in initial rates; whereas, dGuo and 5′-dGMP as well as TGGT and 5′-p-TGGT show the same initial rate.

- Photo-conversion yields of G•+ to sugar radicals in oligonucleotides decreases as the overall chain length increases. However, for high molecular weight dsDNA (salmon testes) in frozen aqueous solutions substantial conversion of G•+ to C1′• (only) sugar radical is still found.

- Within the cohort of sugar radicals formed we find a relative increase in the formation of C1′• with length of the oligonucleotide along with decrease in C3′• production while C5′• also decrease but to a lessor extent. In dsDNA, similar to our earlier work 13, 14 formation of only C1′• via photo-excitation is observed.

- In earlier work we showed that phosphate substitution at a 3′- or 5′- position in nucleosides tended to deactivate radical formation at that site, presumably by increasing the bond strength of the C-H bond at that site.24 Thus, one hypothesis for the large extent of C5′• formation in these systems was that the hole was transferred from G•+ to the 5′- nucleoside which has a 5′-OH. Therefore, we tested 5′-p-TGGT in addition to TGGT expecting a decrease in C5′• formation via photo-excitation of G•+. However, the initial rate and the final sugar radical cohort remained identical in TGGT and in 5′-p-TGGT. Thus, the presence of the phosphate moiety at the 5′-end in 5′-p-TGGT apparently does not have a significant influence on the rate or the type of sugar radical formed via photo-excitation.

Temperature dependence of these photo-excitation reactions in DNA

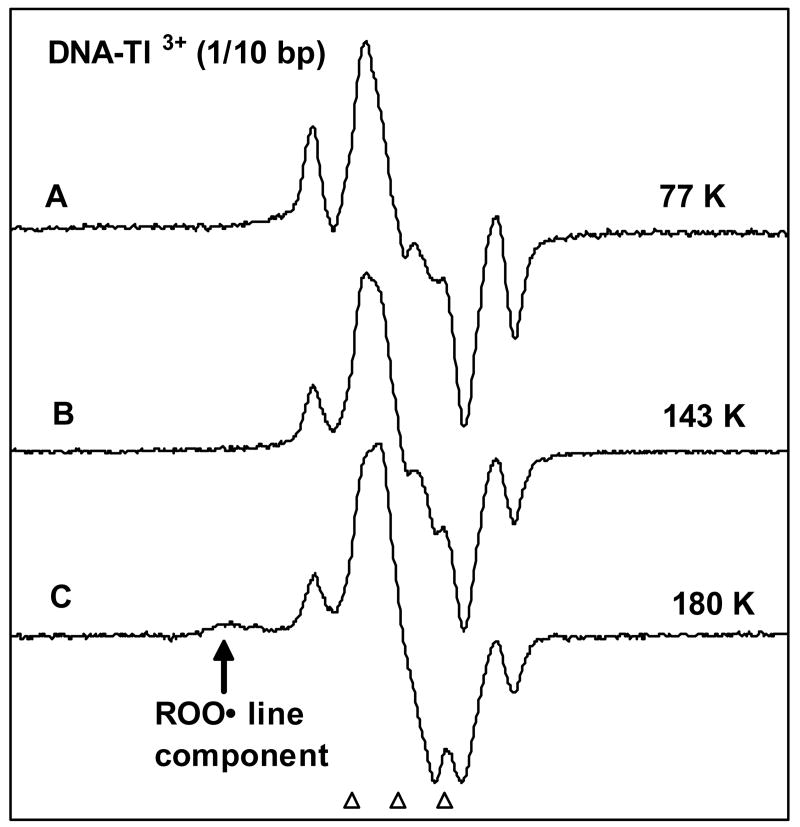

In Figure 4A, from our earlier work14, we show the spectrum obtained after photo-excitation of G•+ in the ice samples of high molecular weight ds DNA (50 mg salmon testes DNA/mL in D2O) with 1 Tl3+/10 base pairs for 110 minutes using a 380 – 480 nm band-pass filter. In this case, photo-excitation was carried out using a high pressure Xe lamp at 77 K. This spectrum shows prominent line components of C1′• at the wings.14 In Figure 4B and 4C, ESR spectra are presented of an identically prepared and handled sample as in Figure 4A after photo-excitation using a 250 W photoflood lamp at 143 K for 90 min (4B) and 180 K for 90 min (4C). In Figure 4A, B and C, we observe prominent outer line components of C1′• in the wings in spectra. In dsDNA in ices, unlike the deoxyribonucleoside/tide systems in glasses, we do not observe an increase in the conversion of G•+ to C1′• at 143 K as opposed to 77 K (see Table 1). The spectrum in Figure 4C for photolysis at 180 K shows evidence of peroxyl radicals 1a, d, j in the wings, which result from reaction of residual oxygen in the sample with the sugar radicals formed. However, we still observe the prominent line components of C1′• Thus, we conclude that the mechanisms in the formation of C1′• via photo-excitation of G•+ are functional up to at least 180 K. From the lack of temperature dependence observed from 77 K to 180 K it is likely that at temperatures which more closely correspond to biological conditions this mechanism will be operative.

Figure 4.

Ice samples of DNA (50 mg/mL in D2O) with 1 Tl3+/10 base pairs were γ-irradiated to 15.4 kGy dose at 77 K and were then annealed to 130 K to remove the •OH signal. (A) ESR spectrum obtained after illumination with the aid of a high pressure Xe lamp (Oriel corporation), at 77 K for 110 min with 380-480 nm band-pass filter.14 (B) After photo-excitation using a 250 W photoflood tungsten lamp of an identically prepared and handled sample as in A at 143 K for 90 min without any filter. (C) After illumination by the same photoflood lamp of another identically prepared and handled sample as in A and B at 180 K for 90 min. Spectrum (C) also shows outer line component of peroxyl radical which decreases the intensity of the sugar components slightly. All spectra were recorded at 77 K.

Discussion

Wavelength and DNA strand length influence on sugar radical formation with photo-oxidation of G•+

The initial yield found for sugar radical formation was highest in nucleosides or dinucleoside phosphates and decreased gradually to 50% yield as the oligonucleotide increased in length. A definitive wavelength dependence on yield was observed for the longest oligonucleotide TTGGTTGGTT as well as high molecular weight dsDNA. TD-DFT calculations for excited G•+ in dGuo predict allowed electronic transitions throughout the whole visible spectral region that show delocalization of spin and positive charge on to sugar moiety.14 These calculations agree with experimental findings that for excited G•+ in dGuo, radical yields and radical identities are relatively independent of wavelength. When these TD-DFT calculations were extended to excited G•+ in TpdG 15 and to other dinucleoside phosphates17 the calculated transition energies indicated that base-to-base hole transfer is predicted at the longest wavelengths and that hole transfer to the sugar-phosphate moiety is predicted in the UVA-vis wavelengths. These theoretical results offer an explanation for our experimental finding regarding decline in the yield of sugar radical formation at longer wavelengths with oligonucleotide length, i.e., at longer wavelengths (>500 nm), base-to-base hole transfers occur which do not transfer the hole to the sugar-phosphate portion and thereby prevents DNA-sugar damage.

While base-to-base hole transfer in the oligonucleotides studied is expected to place holes on thymine based on the recent TD-DFT calculations15, 17, experimentally, no significant line component of thymine radicals was observed during formation of C1′• and C3′• via photo-excitation of G•+ in TpdG.15 Similarly, we did not observe line components of thymine radicals in oligonucleotides studied here (see Figures 3(B) – (E) and (G) – (I) and also supporting information Figure S3) or in DNA (see Figure 4 in this study and Figure 3 in Ref.14) during or after photo-conversion of G•+ to sugar radicals. It is well known that base stacking in oligonucletides and in dsDNA allows photo-induced transfer of spin and charge to nearby bases as suggested in this work.25 – 27 We note that for double stranded oligonucleotides lacking guanine bases, formation of the allylic thymyl i.e. UCH2• radical has been observed by Schuster and his co-workers.28 Initial ongoing studies on our part (not shown) regarding photo-excitation of one-electron-oxidized TpdA and dApT point towards slightly higher yields of thymine radical components on photo-excitation of the one-electron oxidized dinucleoside phosphates.

Why does photo-excitation of G•+ in dGuo result in C3′•, C5′• and C1′• but only C1′• in dsDNA?

Among all the model compounds including mononucleosides/tides, dinucleoside phosphates and oligonucleotides listed in Table 1, G•+ in 5′-dGMP and in TpdG show very high initial rates of conversion as well as the near complete conversion to C1′• (90-95% of sugar radicals) upon photo-oxidation at 143 K. However, for 5′-dGMP at 77 K the results in Table 1 shows less overall conversion to sugar radicals with little C1′• formation (15% of sugar radicals) but with substantial amounts of C3′• and C5′•. Earlier we showed that warming of the glassy samples of 5′-dGMP (already photo-excited at 77 K) from 77 K to 143 K in the dark without further photo-excitation results only in small changes in hyperfine splittings with no changes in radical distribution.14 Thus the C5′• and C3′• do not convert to C1′• on annealing.14 Interestingly while we find predominantly C1′• and no C5′• formation in TpdG, we find substantial C5′• formation in TGT (50%) and in TGGT (60%) (Table 1). The presence of the central doublet found in spectra shown in Figure 3B and 3C, clearly and unequivocally point to the formation of C5′• in one-electron-oxidized the TGT and TGGT samples. However, it is not clear whether the C5′• radical is formed at C5′ position on G or at the C5′ position on the 5′-terminal T. TD-DFT calculations of one-electron oxidized TpdG predicts that during photo-excitation (1.5 eV), hole transfer to the sugar moiety attached to the 5′- thymine with occur.15 Therefore, theory does allow for C5′• formation at several sites on TGGT. In TGGT, if the 5′- terminal T site was the site for C5′• formation, we would expect that the presence of a phosphate moiety at the 5′-end in TGGT (i.e. in 5′-p-TGGT) would hinder C5′• formation at that site. However, no such effect was observed experimentally (see Table 1 and compare spectra shown in Figures 3C and 3D).

Many of the above observations suggest that it is more than just gross structure which determines the deprotonation site. These results strongly suggest that conformation of the one-electron oxidized radicals in the excited state during photo-excitation is critical. It is likely that conformation alters the hole distribution on the sugar ring and thus the final sugar radical cohort during photo-excitation at 143 K in the excited state. We also note here that recent ion-imaging studies regarding photo-dissociation of propanal cation29 show that fast intersystem crossing occurs from the excited state to a hot ground state and that this results in products observed. Further the authors find that the specific pathway and the type of products formed depends critically on the conformation of the cation radical. Thus while this work is in accord with our suggestion that the type of sugar radical formed via photo-excitation of G•+ depends upon its conformation, this work also suggests that in our work the deprotonation from the sugar moiety leading to the sugar radical formation may not not occur directly from the excited cation state but from a “hot” cation ground state.

Is the mechanism of sugar radical formation via photo-oxidation of one-electron oxidized base radical found applicable to biological relevant temperatures?

The formation of C1′• due to photo-excitation of G•+ in dsDNA ice samples is shown in Figure 4 to occur at 180 K as well as at 77 K and 143 K. Although these temperatures still do not correspond to biological conditions, the lack of a significant temperature dependence in the initial rate of C1′• formation upon photo-excitation of G•+ in dsDNA from 77 K to 180 K suggests applicability at higher temperatures. The availability of multiple local sites on the DNA itself as proton acceptors as well as a structure that inherently allows for facile proton transfer, we believe, accounts for the lack of significant temperature dependence of C1′• formation upon photo-excitation of G•+ in frozen samples of highly polymerized dsDNA.

Conclusions

This work shows evidence that photo-excitation of one-electron oxidized DNA-dinucleoside phosphates and DNA-oligonucleotides (no. of bases ≤5) lead to the formation of high yields (ca. 75-90 %) of deoxyribose-sugar radicals. The extent of photo-conversion to sugar radicals as well as its initial rate decreases with increasing size of the oligonucleotides but remains substantial (50%) even for DNA of thousands of base pairs in length (salmon testes DNA). Specific sugar radicals have been identified predominantly from deprotonation at the C5′, and C1′ positions in the deoxyribose moiety. In our earlier experimental and theoretical works 13 - 17 we have shown that photo-excited one-electron oxidized adenine and guanine base-radicals are quenched by formation of sugar radicals. These results may have implications for a number of investigations of hole transfer through DNA 25 -27 in which DNA holes are subjected to continuous visible illumination. These investigations rely on the competition of hole transfer with the quenching reaction of the hole (e.g., G•+) with water, forming 8-HO-G• and ultimately 8-oxo-G. 25 -27 Therefore, from this work and also from our earlier works 13 - 17, we note that photo-induced DNA-hole transfer and its conversion to sugar radicals are also expected along with the natural DNA-hole transfer processes such as tunneling and thermally activated hopping reported in the literature 1, 25-27 and the references therein.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information is available and it contains the following. 1. Figure S1 showing comparison of the C1′• spectra obtained experimentally in TGT and in dGpdG via subtraction and via simulation. 2. Figure S2 representing ESR spectra of one-electron oxidized TGT, TGGT, 5′-p-TGGT, TGGGT, TTGTT, TTGGTT and TTGGTTGGTT and showing that each one of these spectrum is mainly due to G•+. 3. ESR spectra of one-electron oxidized AGA and AGGGA followed by photo-oxidation leading to the sugar radical formation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH NCI under grant no. R01CA045424. A.A. is grateful to the authorities of the Rajdhani College and the University of Delhi for leave to work on this research program.

References

- 1.von Sonntag C. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology. Taylor & Francis; London: 1987. pp. 221–294.Lett JT. Prog Nuceic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990;39:305–352. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60630-3.Becker D, Sevilla MD. Adv Radiat Biol. 1993;17:121–180.Becker D, Sevilla MD. Royal Society of Chemistry Specialist Periodical Report. In: Gilbert BC, Davies MJ, Murphy DM, editors. Electron Spin Resonance. Vol. 16. 1998. pp. 79–114.Weiland B, Hüttermann J. Int J Radiat Biol. 1998;74:341–358. doi: 10.1080/095530098141483. and references therein. Weiland B, Hüttermann J. Int J Radiat Biol. 1999;75:1169–1175. doi: 10.1080/095530099139647. and references therein. Ward JF. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000;65:377–382. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.377. and references therein. Sevilla MD, Becker D. Royal Society of Chemistry Specialist Periodical Report. In: Gilbert BC, Davies MJ, Murphy DM, editors. Electron Spin Resonance. Vol. 19. 2004. pp. 243–278.Bernhard WA, Close DM. In: Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter Chemical, Physicochemical and Biological Consequences with Applications. Mozumdar A, Hatano Y, editors. Marcel Dekkar, Inc.; New York, Basel: 2004. pp. 431–470.von Sonntag C. Free-radical-induced DNA Damage and Its Repair. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2006. pp. 335–447.Becker D, Adhikary A, Sevilla MD. In: Charge Migration in DNA Physics, Chemistry and Biology Perspectives. Chakraborty T, editor. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2007. In Press.

- 2.Becker D, Bryant-Friedrich A, Trzasko C, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 2003;160:174–185. doi: 10.1667/rr3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudaïffa B, Cloutier P, Hunting D, Huels MA, Sanche L. Science. 2000;287:1658–1660. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanche L. Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 2002;21:349–369. doi: 10.1002/mas.10034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Sevilla MD, Sanche L. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13668–13669. doi: 10.1021/ja036509m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdys J, Anusiewicz I, Skurski P, Simons J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6441–6447. doi: 10.1021/ja049876m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Y, Cloutier P, Hunting DJ, Sanche L, Wagner JR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16592–16598. doi: 10.1021/ja054129q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bald I, Kopyra J, Illenberger E. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4851–4855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.König C, Kopyra J, Bald I, Illenberger E. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:018105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.018105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ptasiska S, Denifl S, Gohlke S, Scheier P, Illenberger E, Märk TD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1893–1896. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu J, Xie Y, Schaefer HF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1250–1252. doi: 10.1021/ja055615g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swiderek P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4056–4059. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shukla LI, Pazdro R, Huang J, DeVreugd C, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 2004;161:582–590. doi: 10.1667/rr3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adhikary A, Malkhasian AYS, Collins S, Koppen J, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5553–5564. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 2006;165:479–484. doi: 10.1667/rr3563.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adhikary A, Becker D, Collins S, Koppen J, Sevilla MD. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1501–1511. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar A, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24181–24188. doi: 10.1021/jp064524i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, Yan M, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 1994;137:174–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker D, La Vere T, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 1994;140:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.La Vere T, Becker D, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 1996;145:673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Becker D, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:24171–24180. doi: 10.1021/jp064361y. and references therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Sevilla MD, Becker D, Yan M, Summerfield SR. J Phys Chem. 1991;95:3409–3415. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yan M, Becker D, Summerfield SR, Renke P, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:1983–1989. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang W, Sevilla MD. Radiat Res. 1994:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Spaletta RA, Bernhard WA. Radiat Res. 1993:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Mrozcka NE, Bernhard WA. Radiat Res. 1993;135:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Mrozcka NE, Bernhard WA. Radiat Res. 1995;144:251–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Cullis PM, Davis AS, Malone ME, Podmore ID, Symons MCR. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1992;2:1409–1412. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hüttermann J, Lange M, Ohlmann J. Radiat Res. 1992;131:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Hüttermann J, Röhrig M, Köhnlein W. Int J Radiat Biol. 1992;61:299–313. doi: 10.1080/09553009214550981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Jovanovic SV, Simic MG. J Phys Chem. 1986;90:974–978. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jovanovic SV, Simic MG. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1008:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Seidel CAM, Schulz A, Sauer MHM. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:5541–5533. [Google Scholar]; (d) Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]; (e) Baik MH, Silverman JS, Yang IV, Ropp PA, Szalai VS, Thorp HH. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:6437–6444. [Google Scholar]; (f) Fukuzumi S, Miyao H, Ohkubo K, Suenobu T. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:3285–3294. doi: 10.1021/jp0459763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Colson AO, Sevilla MD. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:3867–3874. [Google Scholar]; (b) Colson AO, Sevilla MD. Int J Radiat Biol. 1995;67:627–645. doi: 10.1080/09553009514550751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuster GB, editor. Topics In Current Chemistry. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2004. Long Range Charge Transfer in DNA. I and II. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagenknecht HA, editor. Charge Transfer in DNA: From Mechanism to Application. Willey-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weiheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Giese B. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:631–636. doi: 10.1021/ar990040b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Giese B. Ann Rev Biochem. 2002;71:51–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.083101.134037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schuster GB. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:253–260. doi: 10.1021/ar980059z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lewis FD, Letsinger RL, Wasielewski MR. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:159–170. doi: 10.1021/ar0000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Delaney S, Barton JK. J Org Chem. 2003;68:6475–6483. doi: 10.1021/jo030095y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lewis FD. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:65–72. doi: 10.1562/2004-09-01-ir-299.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Shao F, Augustyn K, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17446–17452. doi: 10.1021/ja0563399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Pascaly M, Yoo J, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9083–9092. doi: 10.1021/ja0202210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joy A, Ghosh AK, Schuster GB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5346–5347. doi: 10.1021/ja058758b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim MH, Shen L, Tao H, Martinez TJ, Suits AG. Science. 2007;315:1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1136453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information is available and it contains the following. 1. Figure S1 showing comparison of the C1′• spectra obtained experimentally in TGT and in dGpdG via subtraction and via simulation. 2. Figure S2 representing ESR spectra of one-electron oxidized TGT, TGGT, 5′-p-TGGT, TGGGT, TTGTT, TTGGTT and TTGGTTGGTT and showing that each one of these spectrum is mainly due to G•+. 3. ESR spectra of one-electron oxidized AGA and AGGGA followed by photo-oxidation leading to the sugar radical formation.