Abstract

BACKGROUND

Discrimination has been shown as a major causal factor in health disparities, yet little is known about the relationship between perceived medical discrimination (vs. general discrimination outside medical settings) and cancer screening behaviors. We examined whether perceived medical discrimination is associated with lower screening rates for colorectal and breast cancers among racial and ethnic minority adult Californians.

METHODS

Pooled cross-sectional data from 2003 and 2005 California Health Interview Surveys were examined for cancer screening trends among African-American, American-Indian/Alaskan-Native, Asian, and Latino adult respondents reporting perceived medical discrimination compared to those not reporting discrimination (n=11,245). Outcome measures were dichotomous screening variables for colorectal cancer among respondents, ages 50 -75; and breast cancer among women, ages 40 - 75.

RESULTS

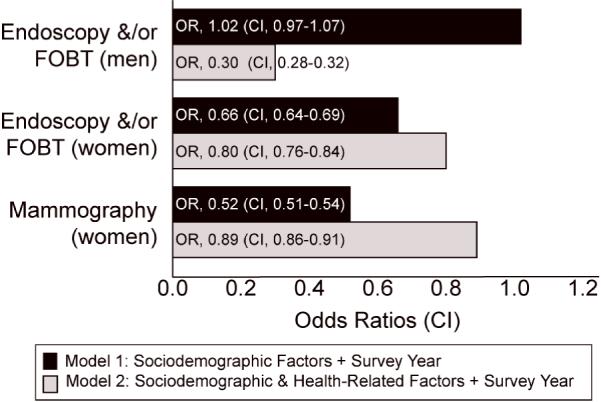

Women perceiving medical discrimination were less likely to be screened for colorectal (OR = 0.66; CI = 0.64 - 0.69) or breast cancer (OR = 0.52; CI = 0.51 - 0.54) compared to women not perceiving discrimination. Although men who perceived medical discrimination were no less likely to be screened for colorectal cancer than those who did not (OR = 1.02; CI = 0.97 - 1.07), significantly lower screening rates were found among men who perceived discrimination and reported having a usual source of health care (OR = 0.30; CI = 0.28 - 0.32).

CONCLUSIONS

These findings of a significant association between perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination and cancer screening behaviors have serious implications for cancer health disparities. Gender differences in patterns for screening and perceived medical discrimination warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Cancer screening, Racial/ethnic disparities, Perceived discrimination, Colorectal cancer, Breast cancer

INTRODUCTION

Much of the morbidity and mortality disparities associated with colorectal and breast cancer can be attributed to lower screening rates or later stage disease detection among racial or ethnic minority persons as compared to whites.1 Acceptance of and adherence to screening recommendations may be influenced by factors at the patient level (e.g. health beliefs, education status, cultural barriers), provider level (e.g. failure to recommend), system level (e.g. access, costs, unavailable translators) or any combination of these factors.2 In their 2002 report on unequal treatment in American health care, the Institute of Medicine raised the concern that racial and ethnic discrimination may play a major causal role in health care disparities.2 We explored discrimination and its relationship to cancer screening behaviors as a potential contributor to cancer health disparities among racial and ethnic minority adults.

Defined as “differences in care that result from biases, prejudices, stereotyping, and uncertainty in clinical communication and decision-making,”2 discrimination is difficult to measure directly. Indirect observational studies on provider bias have focused on screening and referral behaviors, using differential patient outcome measures (i.e., was a patient referred for screening/intervention or not) or physician responses to hypothetical patients in different scenarios as proxies for discrimination.3, 4 Among studies that have employed audio and video techniques to directly observe physician-patient encounters, none have examined indicators of physician bias.5-8 Thus, without direct observed evidence, much of the literature linking discrimination to health outcomes use patient or subject self reports of the perception of being treated unfairly vs. the actual intentional or de facto act of discrimination,9 and thus do not address if and how patients might misinterpret provider behaviors and presume bias when it may not be real. Nonetheless, discrimination—perceived or real—has been shown to impact health seeking behaviors: persons reporting perceived general (vs. medical) discrimination have been shown to be less likely to use prevention services such as cholesterol testing, hemoglobin A1c monitoring, diabetic foot and eye examinations, and flu shots compared to those who do not perceive being treated unfairly.10,11 Perceived general discrimination has also been shown to influence medication adherence, with delays in filling prescriptions or receiving medical tests being greater among persons who perceive unfair treatment or racism in their health care setting.12, 13

The substantial literature on the relationship between perceived discrimination and health outcomes has most commonly measured discrimination experienced in general (such as at the workplace or other social arenas) rather than medical discrimination—that is, unfair perceived or real treatment experienced within the health system or by medical providers.9, 14-26 It would seem that the proximity of perceived discriminatory behaviors or cues occurring in settings where health advice or recommendations are given would have a greater influence on patient health practices than perceived discrimination occurring in non-health care settings. Therefore we wished to explore if patients who perceive racial or ethnic-based discrimination in medical settings would be similarly less likely to participate in prevention activities. We were particularly interested in understanding the relationship between perceived medical (as opposed to general) discrimination and specific cancer screening behaviors as there have been no studies that have tested this particular association.

In this paper we examine the association between perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination and screening outcomes for two leading causes of cancer morbidity and mortality (colorectal and breast cancers) among a large racially and ethnically diverse sample. Previous surveys found that the study population met or exceeded Healthy People 2000 and 2010 screening goals for colorectal, breast, and cervical cancers; however Asian-Americans and Latinos consistently showed lower screening rates for colorectal and breast cancers, (but not for cervical cancer).27, 28 We therefore limit our paper to colorectal and breast cancer screening outcomes. Our study aims are to: 1) determine the rates of cancer screening for racial and ethnic minority populations in California according to recommendations for colorectal and breast cancer; and 2) determine whether recent perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination (within the past five years) is associated with being up to date with screening for these two types of cancers.

METHODS

Data Source and Sampling

We used pooled data from the 2003 and 2005 surveys of adult women and men, from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), a large population survey of non-institutionalized racially and ethnically diverse adults residing in California households. The CHIS is one of several state-wide surveys that provide data on health behaviors, including cancer screening practices. It is unique among state surveys (such as individual state modules for the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System—BFRSS) or among national surveys (such as the National Health Interview Survey—NHIS) in that it is the only survey that has included specific questions on both perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination and cancer screening. CHIS survey methods were similar across both the 2003 and 2005 study years; thus pooling was achieved by concatenating data from both surveys and creating new replicate and final statistical weights for the combined data. Details of this process have been described previously.29

Sample selection was made by a random-digit dialing using a list-assisted procedure.30 Randomly generated telephone numbers within the California area codes were classified as listed, unlisted, or nonresidential by matching to computerized files of White Pages (residential) and Yellow Pages (business). All numbers listed in the Yellow Pages were eliminated from the sample. A random sample of remaining numbers was drawn from within each of 41 predefined geographic areas (roughly equivalent to all California counties). Only one adult per household was sampled. Households without landlines (3% of California households) or with cell phones only (10% of households) were not included in the sample.30-32 Telephone interviews were then conducted in one of the six major languages spoken by most Californians (English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese, and Korean).

Response rates for each survey year are reported by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.33, 34 Nearly fifty-six percent (55.9 %) of households contacted in 2003 completed the survey screening questionnaire; in 2005 the screening completion rate was lower (49.8%). The adult interview completion rates among those screened were 60% and 54% for 2003 and 2005, respectively. Thus the overall response rates (composites of screener and adult interview completion rates) were 33.5% for the 2003 CHIS survey and 26.9% for the 2005 survey. These figures are comparable to California BRFSS response rates for the same survey years.

Data were obtained directly from public use files available at http://www.chis.ucla.edu/chis_questionnaires.html. For our analysis, the sample was limited to the population for whom screening recommendations for colorectal and breast cancer have been established.35-38 This includes women and men aged 50 - 75 years (for colorectal cancer screening) and women aged 40 -75 years (for breast cancer screening). Following the reports from the IOM study on racial and ethnic discrimination,2 we were interested in perceived discrimination among all respondents who self-described their race as African-American, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, or ethnicity as Latino. We did not include White, non-Hispanics (who represented 63% of the 2003 and 2005 CHIS respondents) as this group historically has not been subjected to discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity.2 In addition, respondents identifying as “other” or as multiple racial groups were excluded as they represented only 3% of the total sample.

Study Design

Analyses

We conducted separate multivariate logistic regression models with up to date colorectal and breast cancer screenings as the outcome variables, using weighted data to account for potential sampling biases.39 These models tested the associations between perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination and measures of recent colorectal and breast cancer screenings, defined below. Based on past literature showing differential reporting of perceived discrimination by gender,10, 11, 14 we explored potential interactions by adding the variable gender along with a combined cross-product (gender-discrimination). Both variables were highly significant (data not shown); thus we stratified by gender. In addition, we ran two models for each cancer screening outcome, adjusting for potential confounding from sociodemographic factors (age, education, household income, race or ethnicity) and health-related factors (health insurance, health status, having a usual source of care, having a previous diagnosis of cancer).40-42 For both colorectal and breast cancer screening, Model 1 examined the association between perceived medical discrimination and screening, adjusted for sociodemographic factors and survey year. Model 2 adjusted for sociodemographic factors in addition to health-related factors and survey year. Results for Models 1 and 2 are presented separately for women and men as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Lastly, we present screening rates (adjusted for potential confounding variables) by race or ethnicity and gender and by whether respondents perceived or did not perceive medical discrimination. We present this as weighted data to be representative of the California population.

Predictor variable

The predictor variable in the models was perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination within the last five years (yes/no). The variable was derived from two survey questions: “Was there ever a time when you would have gotten better medical care if you had belonged to a different race or ethnic group?” and if yes, “Think about the last time this happened. How long ago was that?” Because we were interested in whether recent perceptions of medical discrimination affected whether or not a respondent was up to date with screening recommendations (i.e., screening within the last 1 - 5 years), we limited our analysis to respondents who reported perceived medical discrimination within that time period.

Outcome variables

The outcome variables in the models were derived from survey questions related to colorectal and breast cancer screening. Respondents were asked if they ever had a home blood stool test; if they ever had an endoscopic exam; and if they ever had a mammogram. Each question was followed by asking about time intervals (how long since the most recent of these tests). To determine if respondents were up to date for those cancer screenings, we followed recommendations established by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)38, the American Cancer Society (ACS)35, the American Gastroenterological Society36, and the American Geriatrics Society37. There are several options available for colorectal cancer screening, each with different recommended time intervals. The recommended interval for home fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) is once yearly. Although recommendations differ between the timing of the two endoscopic examinations (sigmoidoscopy every 5 years and colonoscopy every 10 years), the CHIS combines both in a single question. Therefore, we limited our analysis to endoscopic screening for the more recent of the two intervals (five years). The recommended screening interval for mammography is once yearly. Thus we created dichotomous (yes/no) outcome variables defined as follows:

Endoscopy and/or FOBT: a combined variable of endoscopic tests (sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy) within 5 years and/or FOBT within the past 1 year to assess whether respondents received either one or both of these two recommended colorectal cancer screening modalities, ages 50 -75.

Mammography: breast cancer screening by mammography within the past 1 year, ages 40 and 75.

Co-variables

Co-variables in the models included the survey year and the following sociodemographic and health status variables (to account for potential confounders40-42), as well as all first-order interaction terms:

Sociodemographic factors: age (continuous), education (in 4 categories: <12, 12, 13-15, 16+ years of education), household income (imputation was used for missing data, thus income as percentage of federal poverty level was complete, reported in 4 categories: ratio of annual household income divided by federal poverty level), and self-reported race or ethnicity (using UCLA Center for Health Policy Research categories, self-described ethnicity as African-American, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian American, or Latino)39

Health status factors: health insurance (yes/no), self-reported health status (5 levels: excellent/very good/good/fair/poor), having a usual source of care (yes/no), and having a previous diagnosis of cancer (yes/no)

Survey year: 2003 or 2005 CHIS survey

RESULTS

Our sample included 8,051 women ages 40 - 75 years and 3,194 men ages 50 - 75 years. The sociodemographic, health related profile, and cancer screening rates are shown in Table 1 (unweighted data characterizing the actual sample). About 53% of women and 56% of men had completed some college or more. Most reported having at least some health insurance (84% women; 86% men); identified having a usual source of health care (92% women; 91% men); and reported their health status as good to excellent (65% women; 64% men). Less than 7% of respondents reported a previous diagnosis of cancer. Nearly 9% of women reported perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination within the past 5 years; reported rates for men were lower (6.2%). Colorectal cancer screening rates were nearly identical for women and men, ages 50 - 75 years (42% and 43%, respectively). Nearly 60% of women ages 40 - 75 years had received a mammogram within the past year.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Health Related Profile and Cancer Screening Rates for Study Sample, Pooled 2003 and 2005 CHIS data, Unweighted, women aged 40-75, men aged 50-75.

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 40 - 49 | 3493 | (43.4) | - | - |

| 50 - 59 | 2523 | (31.3) | 1758 | (55.0) |

| 60 - 75 | 2035 | (25.3) | 1436 | (45.0) |

| Education (years) | ||||

| < 12 | 2065 | (25.6) | 770 | (24.1) |

| 12 | 1764 | (21.9) | 628 | (19.7) |

| 13-15 | 2043 | (25.4) | 730 | (22.8) |

| >15 | 2179 | (27.1) | 1066 | (33.4) |

| 2002 household income (% of federal poverty level) | ||||

| 0 - 99% | 1679 | (20.8) | 533 | (16.7) |

| 100 - 199% | 1882 | (23.4) | 658 | (20.6) |

| 200 -299% | 1027 | (12.8) | 449 | (14.1) |

| ≥ 300% | 3463 | (43.0) | 1554 | (48.6) |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||

| African-American | 1744 | (21.7) | 676 | (21.2) |

| American Indian/American Native | 420 | (5.2) | 176 | ( 5.5) |

| Asian | 2601 | (32.3) | 1152 | (36.1) |

| Latino | 3286 | (40.8) | 1190 | (37.2) |

| Health related profile | ||||

| Insurance status | ||||

| Insured | 6757 | (83.9) | 2734 | (85.6) |

| Uninsured | 1294 | (16.1) | 460 | (14.4) |

| Usual source of health care | ||||

| Yes | 7417 | (92.1) | 2891 | (90.5) |

| No | 634 | (7.9) | 303 | (9.5) |

| Health status | ||||

| Excellent | 997 | (12.4) | 406 | (12.7) |

| Very Good | 1846 | (22.9) | 710 | (22.2) |

| Good | 2392 | (29.7) | 942 | (29.5) |

| Fair | 2020 | (25.1) | 790 | (24.7) |

| Poor | 796 | (9.9) | 346 | (10.8) |

| Ever told had cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 536 | (6.7) | 222 | (6.9) |

| No | 7515 | (93.3) | 2972 | (93.1) |

| Perceived medical discrimination within last 5 | ||||

| years† | ||||

| Yes | 685 | ( 8.9) | 187 | (6.2) |

| No | 7041 | (91.1) | 2825 | (93.8) |

| Cancer screening rates | ||||

| Endoscopy within past 5 years and/or fecal occult blood test within past year, age ≥ 50‡ | 1903 | (41.8) | 1386 | (43.4) |

| Mammography within past year, age ≥ 40 | 4761 | (59.1) | ||

Self-reported race/ethnic identity using UCLA CHPR categories; white, non-Hispanic excluded.

Respondents answering “yes” to question: “Was there ever a time when you would have gotten better medical care if you had belonged to a different race or ethnic group?”

Endoscopy: sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

Figure 1 presents the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from the logistic regression models (Models 1 and 2), showing the associations between perceived racial or ethnic-based medical discrimination and the two cancer screening outcomes, by gender. In Model 1, which examined the association between perceived medical discrimination and screening and adjusted for the four sociodemographic factors (age, education, household income, race or ethnicity), men who had perceived medical discrimination were no less likely (OR = 1.02) to be screened for colorectal cancer using endoscopic and/or fecal occult blood testing compared to those who did not perceive medical discrimination (CI = 0.97 - 1.07). By contrast, women who had perceived medical discrimination within the past five years were two-thirds as likely to be screened for colorectal cancer and more than half as likely to have received a mammogram compared to women who did not perceive medical discrimination (colorectal screening OR = 0.66; CI = 0.64 - 0.69; mammography screening OR = 0.52; CI = 0.51 - 0.54).

Figure 1.

Logistic Regression Models: Medical Discrimination and Colorectal & Breast Cancer Screening—Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) by Gender

Model 1: + Sociodemographic Factors + Survey Year

Model2: + Sociodemographic & Health Related Factors + Survey Year

In Model 2, when more specific health-related factors (health insurance, health status, having a usual source of care, having a previous diagnosis of cancer) were added to the previous model, we found a consistent pattern of lower odds of screening for all tests among both men and women who reported perceived medical discrimination. In this second model, it is notable that men who perceived medical discrimination had roughly one-third the risk of not being screened for colorectal cancer using either endoscopy or FOBT compared to those who did not perceive medical discrimination (OR= 0.30, CI = 0.28 - 0.32). A stepwise regression to explain the differences in outcomes among men between Models 1 and 2 showed significant changes when the interaction between having a usual source of care and discrimination was added to the model, indicating that this factor accounted for almost all the decreased likelihood for screening for men.

Differences in adjusted screening rates for colorectal and breast cancer by gender across the four racial or ethnic minority groups are shown in Tables 2 (weighted data). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, all colorectal cancer screening modalities were consistently lower among minority women as compared to men. This pattern held when screening rates were adjusted by both sociodemographic and health related factors for all groups except African-Americans, for whom men had slightly lower screening rates than women. In general, the pattern for women across all ethnic groups showed lower screening rates among those who reported medical discrimination compared to those who did not. This pattern was seen among men as well when screening rates were adjusted for both sociodemographic and health factors, but not when adjusted for sociodemographic factors alone.

Table 2. Weighted Colorectal and Breast Cancer Screening Rates by Ethnicity and Medical Discrimination*.

| % screened | Women % screened | Men % screened | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | No reported discrimination | Reported discrimination | No reported discrimination | Reported discrimination | |

|

Sociodemographic Model‡ Endoscopy&/or FOBT Screening (Adults, age 50-75 years, n=7752) |

||||||

| African-American | 45.6 | 50.5 | 47.7 | 43.6 | 50.5† | 50.4† |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 33.7 | 48.2 | 42.9 | 25.5 | 49.4 | 47.0 |

| Asian | 38.4 | 46.9 | 43.4 | 33.7 | 46.7† | 47.2 † |

| Latino | 38.3 | 45.3 | 41.3 | 35.4 | 44.4 | 46.1 |

| Mammography Screening (Women, age 40-75 years, n=8051) | ||||||

| African-American | 59.1 | 68.3 | 49.3 | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 49.4 | 64.9 | 33.9 | |||

| Asian | 56.3 | 64.0 | 48.2 | |||

| Latino | 57.4 | 66.9 | 47.4 | |||

|

Sociodemographic + Health Factors Model§ Endoscopy&/or FOBT Screening (Adults, age 50-75 years, n=7752) |

||||||

| African-American | 42.9 | 38.6 | 44.1 | 41.7 | 54.4 | 24.9 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 26.8 | 48.1 | 31.4 | 22.6 | 63.6 | 33.1 |

| Asian | 32.3 | 48.4 | 34.8 | 29.9 | 63.0 | 33.9 |

| Latino | 29.9 | 42.1 | 30.8 | 29.0 | 55.1 | 30.1 |

| Mammography Screening (Women, age 40-75 years, n=8051) | ||||||

| African-American | 52.8 | 56.3 | 49.4 | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 37.1 | 44.0 | 30.7 | |||

| Asian | 54.3 | 55.8 | 52.8 | |||

| Latino | 50.9 | 54.4 | 47.3 | |||

Unless otherwise indicated, all the comparisons between no reported vs. reported discrimination are statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Not statistically significant

Predictor variables included in the sociodemographics model were age, education, household income, ethnicity and survey year.

Predictor variables included in the sociodemographics and health factors model were age, education, household income, ethnicity, survey year, health insurance, health status, having a usual source of care, and having a previous diagnosis of cancer.

DISCUSSION

For cancer outcomes, the consequences of delaying or not receiving screening can be critical. When detected early, five-year survival rates for colorectal and breast cancer are greater than 90%. However, survival drops drastically (down to 10% for colorectal cancer and 23% for breast cancer) if detected at an advanced stage. Results from analyses of CHIS data provide a window into cancer screening patterns among Californians. Using earlier 2001 California Health Information Survey data, Etzioni, et. al found that the lack of insurance or not having a usual source of medical care was associated with decreased colorectal cancer screening rates.43 Other CHIS investigators reporting on the impact of immigration or citizenship status suggest that non-citizens and recent immigrants are less likely to be screened for breast or colorectal cancer than immigrants who hold US citizenship.44-46 These earlier CHIS studies did not include perceived discrimination among their predictor variables. Only one study to date has used data from the 2001 CHIS to examine relationships between perceived discrimination and the use of preventive health services, however PSA testing was the only cancer screening measure included among other measures of prevention.10 In addition, the survey question regarding perceived discrimination used in the 2001 CHIS differed from subsequent years. Respondents in 2001 were not asked specifically about perceived racial or ethnic discrimination but rather if they felt they perceived healthcare discrimination for any reason. Subsequent analyses showed that the most frequently cited reason for perceived discrimination among 2001 respondents was insurance type.10 By contrast, the 2003 and 2005 CHIS surveys asked a more specific question about perceived racial or ethnic discrimination within the healthcare system.

Reports of survey data from other US populations have shown no correlations between perceived medical discrimination and cancer screening practices. A study of community-based African-American and White women reported no association between perceived discrimination, (defined as the experience of discrimination in any one of several settings) and breast cancer screening behavior; however, investigators did not study the independent effects of medical discrimination.47 In a national study of medical discrimination among 6,722 adults, investigators similarly reported no relationship between “optimal cancer screening” (a combined variable of fecal occult blood testing, pap smear, and mammography screening) and whether or not respondents reported a range of negative perceptions in health care settings.11 Our study differed from these earlier studies in that we focused on medical discrimination and we analyzed colorectal and breast cancer screening as separate outcomes rather than combined. In addition, we defined our colorectal screening variable to account for multiple testing options rather than one test alone (FOBT), a choice consistent with other investigators and with overall recommendations for colorectal cancer screening.48-50

While the analysis of cross-sectional survey data precludes making causal inferences regarding perceived discrimination and cancer screening behaviors, our findings add to the knowledge of factors that should be considered when determining causes of disparities in cancer screening. We suggest that some persons may delay or avoid getting screened for cancers and that this delay may be associated with racial or ethnic-based experiences they encounter within the medical setting. These results are supported by the range of earlier studies reported by the IOM that cite racial or ethnic discrimination as one of the underlying mechanisms accounting for ethnic cancer health disparities.2

Our findings showed gender differences in three areas: reporting perceived discrimination; being up to date with cancer screening; and the effect of having a usual source of care. A slightly greater proportion of women in our CHIS sample reported medical discrimination (8.9%) compared to men (6.2%). Trivedi et al. also found more California women (5.3%) than men (4.0%) reporting perceived discrimination (for any reason) in the earlier 2001 CHIS.10 As other investigators have reported that (non-California) men are more likely than women to report perceived general14 or medical11 discrimination, our findings and that of Trivedi et al may reflect gender differences in self-disclosure51 that may be specific to California populations.

We also found gender differences in colorectal cancer screening rates. After adjusting for sociodemographic and health factors, screening rates for men exceeded women across all racial and ethnic groups except for African-Americans. Previous investigators have shown gender differences in preferences for types of screening tests.52, 53 In their analysis of Health Information National Trends Survey data, investigators found that the prevalence of FOBT use was greater among women than men; conversely, more men than women used endoscopy for colorectal cancer screening.52 As our study combined several screening test options (home FOBT, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy) into one outcome variable, we were unable to detect gender differences by type of screening test.

We detected gender differences in the effects of having a usual source of medical care on cancer screening outcomes, consistent with other investigators. A multi-year study of NHIS data showed that the increased use of endoscopy by men was modified by having a usual source of health care and other primary care factors.53 Our logistic regression models analyzing the interaction of having a usual source of care on the relationship between perceived discrimination and cancer screening did not show a strong effect for women. However, for men, the effects were not only striking in magnitude, but also in direction. Why would having a usual source of care increase the odds that discrimination negatively impacts screening among men? One possible explanation is that having a usual source of care may increase exposure to situations unique for men that are subsequently perceived to be discriminatory. Discrimination may be compounded by the simultaneous experience of gender bias—that is, gender stereotyping may impact the experience and perception of differential treatment on the basis of race or ethnicity.54, 55 Therefore, in situations where one group (e.g. African-American men) may be subject to more gender bias (e.g. stereotyped as violent), the result may be more discrimination toward or greater perception of racial discrimination by those men as compared to women in similar situations. Thus, gender differences in perceptions and impact of discrimination are likely context specific.

While the overall survey response rates (33.5% for 2003 and 26.9% for 2005) may introduce sample bias, the use of weighted estimates statistically adjusts for non-response and other sample biases.56, 57 The sample excludes institutionalized persons, the small percent (3%) of those without landline telephones, and the 10% of households with only cellular telephones, which may limit generalizations to these small segments of the population who reside in California. In addition, the use of broad ethnic categories fails to account for differences among subgroups within these aggregated population groups (e.g., Mexican-Americans within Latino populations).58, 59 Nonetheless, the strengths of this study include its use of a pooled representative sample over a time that captures the rich diversity of the California population, its inclusion of the four primary ethnic minority groups in the state, and its administration in six languages.

By focusing on medical discrimination, as opposed to general discrimination, our findings suggest that disparities in outcomes may be associated with events (or perceptions of events) that take place in health care settings. We cannot know whether the reported events represented actual discriminatory acts or if perception of discrimination was accurate. Clearly more research is needed to confirm these initial findings and to explain gender differences, as well as to explore important subgroup differences. Equally important is the need to identify specific provider and/or institutional behaviors or cues that signal discrimination among racial and ethnic minority patients. In turn, identifying gender-based and culturally specific interventions and strategies within medical settings may improve the experience of patients from diverse backgrounds and contribute to increased participation in cancer screening and other prevention activities.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Crawley received funding from the National Cancer Institute (Grant #K01 CA 098326-02) for this project. No conflicts of interests are reported among all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures 2007. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002 Jan;40(1 Suppl):I140–151. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999 Feb 25;340(8):618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellerbeck EF, Engelman KK, Gladden J, Mosier MC, Raju GS, Ahluwalia JS. Direct observation of counseling on colorectal cancer in rural primary care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Oct;16(10):697–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Azari R, Kelly-Reif S, Krupat E, Thom DH. Direct observation of requests for clinical services in office practice: what do patients want and do they get it? Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jul 28;163(14):1673–1681. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA, Kelly RB, Zyzanski SJ. Direct observation of rates of preventive service delivery in community family practice. Prev Med. 2000 Aug;31(2 Pt 1):167–176. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Oct;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Jun;21(6):553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard J, Lurie N. R-E-S-P-E-C-T: patient reports of disrespect in the health care setting and its impact on care. J Fam Pract. 2004 Sep;53(9):721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, et al. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Jul;20(7):578–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Mar;22(3):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Williams DR, Diez-Roux AV, Gordon-Larsen P. Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Soc Sci Med. 2006 Sep;63(6):1415–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003 Feb;93(2):232–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manuel RC. Perceived race discrimination moderates dietary beliefs’ effects on dietary intake. Ethn Dis. 2004 Summer;14(3):405–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duffy SA, Jackson FC, Schim SM, Ronis DL, Fowler KE. Racial/ethnic preferences, sex preferences, and perceived discrimination related to end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006 Jan;54(1):150–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Wise LA, Horton NJ, Corwin MJ. Perceptions of racial discrimination and the risk of preterm birth. Epidemiology. 2002 Nov;13(6):646–652. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson JM, Scarinci IC, Klesges RC, Slawson D, Beech BM. Race, socioeconomic status, and perceived discrimination among healthy women. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002 Jun;11(5):441–451. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Din-Dzietham R, Nembhard WN, Collins R, Davis SK. Perceived stress following race-based discrimination at work is associated with hypertension in African-Americans. The metro Atlanta heart disease study, 1999-2001. Soc Sci Med. 2004 Feb;58(3):449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bird ST, Bogart LM, Delahanty DL. Health-related correlates of perceived discrimination in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004 Jan;18(1):19–26. doi: 10.1089/108729104322740884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes LL, Mendes De Leon CF, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Racial differences in perceived discrimination in a community population of older blacks and whites. J Aging Health. 2004 Jun;16(3):315–337. doi: 10.1177/0898264304264202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90307-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 1996 Oct;86(10):1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N, Sidney S, Coakley E. Racial discrimination and skin color in the CARDIA study: implications for public health research. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Am J Public Health. 1998 Sep;88(9):1308–1313. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustillo S, Krieger N, Gunderson EP, Sidney S, McCreath H, Kiefe CI. Self-reported experiences of racial discrimination and Black-White differences in preterm and low-birthweight deliveries: the CARDIA Study. Am J Public Health. 2004 Dec;94(12):2125–2131. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winkleby MA, Kim S, Urizar GG, Jr., Ahn D, Jennings MG, Snider J. Ten-year changes in cancer-related health behaviors and screening practices among Latino women and men in California. Ethn Health. 2006 Feb;11(1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/13557850500391329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babey SH, Ponce NA, Etzioni DA, Spencer BA, Brown ER, Chawla N. Cancer screening in California: racial and ethnic disparities persist. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2003 Sep;(PB20034):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westat Inc. [Accessed August 24, 2007];California Health Information Survey: Examining Trends and Averages Using Combined Cross-Sectional Survey Data from Multiple Years. CHIS Methodology Paper [ http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/paper_trends_averages.pdf.

- 30.California Health Interview Survey . CHIS 2003 Methodology Series: Report 1 - Sample Design. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Census Bureau 2005 American Community Survey [Accessed Jan 2, 2008];California Population and Housing Narrative Profile. 2005 http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/NPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=04000US06&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_NP01&-gc_url=null&-ds_name=&-_lang=en&-redoLog=false.

- 32.California Health Interview Survey . CHIS 2005 Methodology Series: Report 1 - Sample Design. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.California Health Information Survey . CHIS 2003 Methodology Series: Report 4 - Response Rates. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.California Health Information Survey . CHIS 2005 Methodology Series: Report 4 - Response Rates. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Cancer Society . Cancer Prevention and Early Detection: Cancer facts and figures 2003. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003 Feb;124(2):544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee Health Screening Decisions for Older Adults: AGS Position Paper. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(2):270–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) [Accessed Jan 2, 2008];Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/cps3dix.htm#cancer.

- 39.California Health Interview Survey . CHIS 2003 Methodology Series: Report 3 - Data Processing Procedures. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiatt RA, Klabunde C, Breen N, Swan J, Ballard-Barbash R. Cancer screening practices from National Health Interview Surveys: past, present, and future. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002 Dec 18;94(24):1837–1846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.24.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004 May 15;100(10):2093–2103. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2003 Mar 15;97(6):1528–1540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Etzioni DA, Ponce NA, Babey SH, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer test use: results from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2004;101(11):2523–2532. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Alba I, Hubbell FA, McMullin JM, Sweningson JM, Saitz R. Impact of U.S. citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. Journal of general internal medicine. 2005;20(3):290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: Cultural influences or access to care? Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–192. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong ST, Gildengorin G, Nguyen T, Mock J. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening rates among Asian Americans and non-Latino whites. Cancer. 2005;104(12 Suppl):2940–2947. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dailey AB, Kasl SV, Holford TR, Jones BA. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Nonadherence to Screening Mammography Guidelines: Results from the Race Differences in the Screening Mammography Process Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007 Mar 10 1;Jun 10 1;165(11):1287–1295. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang SY, Phillips KA, Nagamine M, Ladabaum U, Haas JS. Rates and predictors of colorectal cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006 Oct;3(4):A117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips KA, Liang SY, Ladabaum U, et al. Trends in colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2007 Feb;45(2):160–167. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000246612.35245.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ananthakrishnan AN, Schellhase KG, Sparapani RA, Laud PW, Neuner JM. Disparities in colon cancer screening in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb 12;167(3):258–264. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dindia K, Allen M. Sex differences in self-disclosure: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1992 Jul;112(1):106–124. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McQueen A, Vernon SW, Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Rakowski W. Are there gender differences in colorectal cancer test use prevalence and correlates? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Apr;15(4):782–791. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Feb;15(2):389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Broman CL, Mavaddat R, Hsu S-y. The Experience and Consequences of Perceived Racial Discrimination: A Study of African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26(2):165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: patterns and psychological correlates. [Accessed March 13, 2007];Dev Psychol. 2006 Mar;42(2):218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.California Health Information Survey Weighting and Estimation of Variance in the CHIS Public Use Files. http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/weighting_var_chis_02282007.pdf.

- 57.Westat Inc. [Accessed Jan 2, 2008];California Health Information Survey: Methodology Series: Report Four - Response Rates. http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/CHIS2005_method4.pdf.

- 58.Blendon RJ, Buhr T, Cassidy EF, et al. Disparities in health: perspectives of a multi-ethnic, multi-racial America. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Sep-Oct;26(5):1437–1447. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin SS, Clarke CA, Prehn AW, Glaser SL, West DW, O’Malley CD. Survival differences among Asian subpopulations in the United States after prostate, colorectal, breast, and cervical carcinomas. Cancer. 2002 Feb 15;94(4):1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]