Abstract

The endothelium plays an important role in maintaining vascular homeostasis by synthesizing and releasing several relaxing factors, such as prostacyclin, nitric oxide (NO), and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF). We have previously demonstrated in animals and humans that endothelium-derived hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is an EDHF that is produced in part by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS). In this study, we show that genetic disruption of all three NOS isoforms (neuronal [nNOS], inducible [iNOS], and endothelial [eNOS]) abolishes EDHF responses in mice. The contribution of the NOS system to EDHF-mediated responses was examined in eNOS−/−, n/eNOS−/−, and n/i/eNOS−/− mice. EDHF-mediated relaxation and hyperpolarization in response to acetylcholine of mesenteric arteries were progressively reduced as the number of disrupted NOS genes increased, whereas vascular smooth muscle function was preserved. Loss of eNOS expression alone was compensated for by other NOS genes, and endothelial cell production of H2O2 and EDHF-mediated responses were completely absent in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, even after antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine. NOS uncoupling was not involved, as modulation of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) synthesis had no effect on EDHF-mediated relaxation, and the BH4/dihydrobiopterin (BH2) ratio was comparable in mesenteric arteries and the aorta. These results provide the first evidence that EDHF-mediated responses are dependent on the NOSs system in mouse mesenteric arteries.

The endothelium plays an important role in maintaining vascular homeostasis by synthesizing and releasing several vasodilators, including prostacyclin (PGI2), nitric oxide (NO), and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) (1–3). It is widely accepted that EDHF plays an important role in modulating vascular tone, especially in microvessels (4, 5). Since the first reports on the existence of EDHF (6, 7), several candidates for EDHF have been proposed, including epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (8, 9), potassium ions (10, 11), gap junctions (12, 13), and, as we have identified, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (14–16). We have demonstrated that endothelium-derived H2O2 is an EDHF in mouse (14) and human (15) mesenteric arteries and porcine coronary microvessels (16). Other investigators have subsequently confirmed the importance of H2O2 as an EDHF in human (17) and canine (18, 19) coronary microvessels and piglet pial arteries (20). We have also demonstrated that endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) is a major source of EDHF/H2O2 (14), where copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD) plays an important role to dismutate eNOS-derived superoxide anions to EDHF/H2O2 in animals and humans (21, 22). However, the mechanism for the endothelial production of H2O2 as an endogenous EDHF remains to be elucidated. Indeed, some EDHF-mediated responses still remain in singly eNOS−/− mice, and the remaining responses are also sensitive to catalase that dismutates H2O2 to form water and oxygen (14).

NO is synthesized by three distinct NOS isoforms (neuronal NOS [nNOS], inducible [iNOS], and eNOS) that compensate each other. Although both eNOS and nNOS are constitutively expressed, iNOS is usually expressed in the context of inflammatory responses, such as sepsis, cytokine release, and heart failure (23, 24). In the vasculature, eNOS is a well-established primary source of NO that plays an important role in the regulation of systemic blood pressure, blood flow, and regional vascular tone (2, 25–27), whereas NO derived from nNOS or iNOS also plays an important role in vasodilatation and vascular protection under various pathological conditions (28–31). A critical determinant of NOS activity is the availability of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a NOS cofactor (32). When BH4 levels are inadequate, the enzymatic reduction of molecular oxygen by NOS is no longer coupled to l-arginine oxidation, resulting in generation of superoxide anions rather than NO, thus contributing to vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. BH4 bioavailability in the vasculature appears to be regulated at the level of biosynthesis by the rate-limiting enzyme GTP cyclohydrolase-1 (GTPCH1). In contrast, administration of the BH4 precursor sepiapterin ameliorates endothelial dysfunction in ApoE-deficent mice (33).

We have recently generated n/i/eNOS−/− mice, which are unexpectedly viable and appear normal, but their survival and fertility rates are markedly reduced compared with WT mice (34). They also exhibit marked hypotonic polyuria, polydipsia, and renal unresponsiveness to the antidiuretic hormone vasopressin, all of which are characteristics consistent with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (34). Furthermore, our recent study indicates that n/i/eNOS−/− mice spontaneously develop cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, and myocardial infarction, resembling metabolic syndrome in humans (35). These results suggest that NOSs system plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis.

Both NO- and EDHF-mediated responses are impaired by various risk factors for atherosclerosis (2, 5) and, conversely, the treatments of those risk factors ameliorate both NO- and EDHF-mediated responses (36, 37). In various pro-atherogenic conditions, the production of reactive oxygen species is increased, whereas NO-mediated relaxations are reduced. EDHF-mediated relaxations are temporarily enhanced to compensate for the reduced NO-mediated relaxations; however, during the progression of atherosclerosis, the EDHF-mediated responses are also subsequently reduced (2).

These lines of evidence led us to hypothesize that EDHF-mediated responses are closely coupled to the whole endothelial NOSs system. In this study, we thus examined the contribution of the whole endothelial NOSs system to EDHF-mediated responses, using eNOS−/−, n/eNOS−/−, and n/i/eNOS−/− mice (34).

RESULTS

Endothelium-dependent relaxations and hyperpolarizations in WT and NOS−/− mice

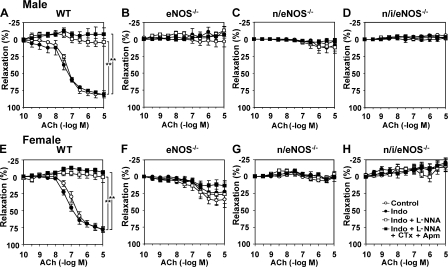

In mesenteric arteries from WT mice of both genders, endothelium-dependent relaxations in response to acetylcholine (ACh) were highly resistant to indomethacin (10−5 M) or Nω-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA; 10−4 M), but were markedly inhibited by a combination of 100 nM charybdotoxin (an inhibitor of large- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium [KCa] channels) and 1 μM apamin (an inhibitor of small-conductance KCa channels), indicating a primary role of EDHF in endothelium-dependent relaxations in those resistance vessels (Fig. 1, A and E). On the other hand, in both genders of eNOS−/−, n/eNOS−/−, and n/i/eNOS−/− mice, NO-mediated relaxations were absent as expected, and whole endothelium-dependent relaxations were reduced in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes (Fig. 1, B-D and F-H). Fig. 1 (I and J) shows the relative contribution of EDHF to endothelium-dependent relaxations of mesenteric arteries from male (Fig. 1 I) and female (Fig. 1 J) WT and the three genotypes of NOS−/− mice. Importantly, EDHF-mediated relaxations were progressively reduced in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes in both genders compared with WT mice, and EDHF-mediated relaxations were approximately halved in eNOS−/− mice, further reduced in n/eNOS−/− mice, and totally absent in n/i/eNOS−/− mice (Fig. 1, I and J). Electrophysiological recordings of membrane potentials with the microelectrode technique in mesenteric arteries demonstrated that endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations to ACh (10−5 M) in male mice in the presence of indomethacin (10−5 M) and l-NNA (10−4 M) were also progressively attenuated in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes (Fig. 1 K).

Figure 1.

Reduced EDHF-mediated relaxations and hyperpolarizations of mesenteric arteries in both genders of NOS−/− mice. Endothelium-dependent relaxations of mesenteric arteries from male (A–D) and female (E–H) mice are shown (n = 6 each). In both genders of WT mice (A and E), endothelium-dependent relaxations were mainly mediated by EDHF, whereas in those of eNOS−/− (B and F), n/eNOS−/− (C and G), and n/i/eNOS−/− mice (D and H) mice, the relaxations were progressively reduced in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes. Indo, indomethacin; CTx, charybdotoxin; Apm, apamin. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Relative contribution of EDHF in male (I) and female (J) mice to the whole endothelium-dependent relaxations to ACh were progressively reduced in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes. *, P < 0.05. (K) Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizations to ACh of mesenteric arteries from male mice also were progressively attenuated in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes (n = 6 each). *, P < 0.05. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

In contrast, in the aorta, endothelium-dependent relaxations to ACh were mainly mediated by NO in WT mice (Fig. 2, A and E) and were totally absent in all three genotypes of NOS−/− mice of both genders (Fig. 2, B-D and F-H).

Figure 2.

Endothelium-dependent relaxations of the aorta in both genders of mice. Endothelium-dependent relaxations of the aorta from male (A–D) and female (E–H) mice are shown (n = 5 each). In the aorta of WT mice (A and E), endothelium-dependent relaxations to ACh were resistant to indomethacin, but were markedly inhibited by l-NNA, indicating a primary role of NO. In contrast, in the eNOS−/− (B and F), n/eNOS−/− (C and G), and n/i/eNOS−/− (D and H) mice, endothelium-dependent relaxations in response to ACh were totally absent. **, P < 0.01. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Endothelium-independent relaxations in WT and NOS−/− mice

Endothelium-independent relaxations to sodium nitroprusside (SNP; an NO donor) were rather enhanced in mesenteric arteries from the three genotypes of NOS−/− mice of both genders compared with WT mice (Fig. 3, A and B), whereas those to NS-1619 (an opener of the large-conductance KCa channels) were preserved (Fig. 3, C and D). Endothelium-independent relaxations to SNP and NS-1619 of the aorta were preserved in all three genotypes of NOS−/− mice of both genders (Fig. 3, E-H).

Figure 3.

Vascular smooth muscle responses of mesenteric arteries and aorta in both genders of mice. Endothelium-independent relaxations of mesenteric arteries in response to SNP (an NO donor) in male (A) and female (B) mice, and those to NS-1619 (an opener of KCa channels) in male (C) and female (D) mice, are shown (n = 6 each). The relaxations to SNP were significantly enhanced in both genders of the three genotypes of NOS−/− mice as compared with WT mice (A and B), whereas those to NS-1619 were unaltered (C and D). Endothelium-independent relaxations of the aorta in response to SNP in male (E) and female (F) mice, and those to NS-1619 in male (G) and female (H) mice are shown (n = 5 each). Those vasodilator responses of vascular smooth muscle were preserved in both genders of the three genotypes of NOS−/− mice compared with WT mice. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Immunoreactivity and protein expression of NO synthases

We performed immunostaining for the three NOS isoforms to examine their localization in mesenteric arteries of WT and the three genotypes of NOS−/− mice. In WT mice, the immunoreactivity of eNOS and nNOS, but not that of iNOS, was noted mainly in the endothelium, and in eNOS−/− and n/eNOS−/− mice, the expression of nNOS and iNOS was noted, respectively (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, none of the NOS isoforms were noted, as expected (Fig. 4 A). Furthermore, we performed Western blot analysis to quantify the protein expression of NOS isoforms in the whole mesentery. In WT mice, the expression of both eNOS and nNOS was noted, whereas that of iNOS was minimal (Fig. 4 B). In eNOS−/− mice, the expression of nNOS was again noted, and in n/eNOS−/− mice, the expression of iNOS was significantly up-regulated compared with WT or eNOS−/− mice (Fig. 4 B). In n/i/eNOS−/− mice, none of the NOS isoforms were noted, as expected (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

Immunostaining and Western blotting for NOS isoforms. (A) Immunostaining for three NOS isoforms and negative control of mesenteric arteries from WT and three genotypes of NOS−/− mice. The magnification (400×) is the same in all figures. Endothelial immunoreactivities of nNOS and iNOS in mesenteric arteries were observed in eNOS−/− and n/eNOS−/− mice, respectively, whereas in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, none of the NOS isoforms were noted. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Protein expression of three NOS isoforms in the whole mesenteric artery from WT and three genotypes of NOS−/− mice (n = 5 each). In WT mice, protein expression of both eNOS and nNOS was noted, and in eNOS−/− mice, that of nNOS alone was noted. In n/eNOS−/− mice, the expression of iNOS was significantly up-regulated, whereas in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, none of the NOS isoforms were noted, as expected. *, P < 0.05. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

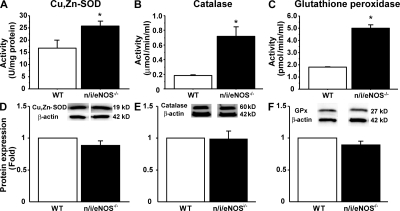

Activities and protein expressions of scavenging enzymes in mouse mesenteric arteries

In the whole mesenteric tissue, the activities of scavenging enzymes, including Cu,Zn-SOD (Fig. 5 A), catalase (Fig. 5 B), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx; Fig. 5 C), were all significantly enhanced in n/i/eNOS−/− mice compared with WT mice. On the other hand, the protein expression of Cu,Zn-SOD (Fig. 5 D), catalase (Fig. 5 E), and GPx (Fig. 5 F) were all comparable between WT and n/i/eNOS−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Activities and expressions of scavenging enzymes in mouse mesenteric arteries. The activities (top row) and protein expressions (bottom row) of Cu,Zn-SOD (A and D), catalase (B and E), and GPx (C and F) in the whole tissue of mesentery from WT and n/i/eNOS−/− mice are shown (n = 5 each). The vascular activities of the enzymes were all significantly enhanced in n/i/eNOS−/− mice compared with WT mice, whereas the protein expressions of the enzymes were all comparable between WT and n/i/eNOS−/− mice. *, P < 0.05 vs. WT. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

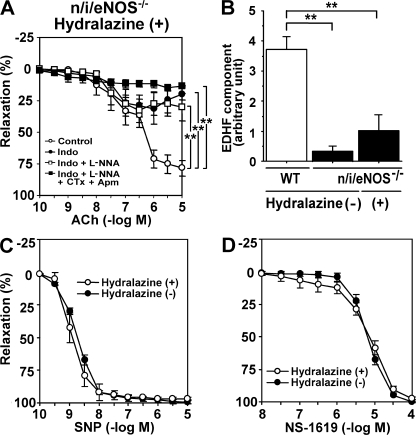

Effect of antihypertensive treatment on EDHF-mediated relaxations in n/i/eNOS−/− mice

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) was significantly higher in n/i/eNOS−/− mice (141 ± 3 mmHg) compared with WT mice (105 ± 3 mmHg; n = 6 each; P < 0.0001). Although antihypertensive treatment with oral hydralazine for 1 wk normalized blood pressure in n/i/eNOS−/− mice (102 ± 2 mmHg), the antihypertensive treatment failed to improve EDHF-mediated responses in those mice (Fig. 6, A and B). The antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine increased indomethacin-sensitive endothelium-dependent relaxations, suggesting an up-regulation of vasodilator prostaglandins (Fig. 6 A). Endothelium-independent relaxations in response to SNP and NS-1619 were comparable between n/i/eNOS−/− mice with and those without the antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine (Fig. 6, C and D).

Figure 6.

Failure of antihypertensive therapy to improve the reduced EDHF-mediated responses in n/i/eNOS−/− mice. (A) In hydralazine-treated n/i/eNOS−/− mice, endothelium-dependent relaxations of mesenteric arteries were improved, but were markedly inhibited by indomethacin (n = 4). **, P < 0.01. (B) Quantitative analysis demonstrated that the antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine failed to improve the reduced EDHF-mediated responses (n = 4 each). **, P < 0.01. Endothelium-independent relaxations in response to SNP (C) and NS-1619 (D) were comparable between n/i/eNOS−/− mice with and those without the antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine (n = 4–6). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

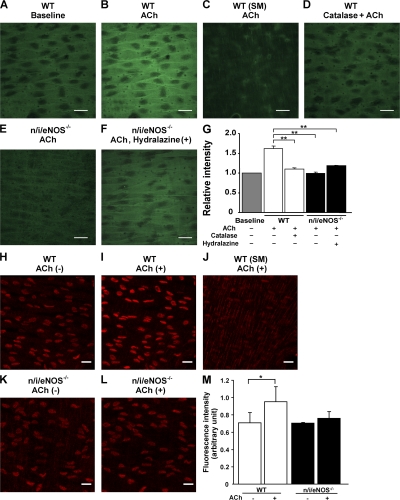

Endothelial H2O2 production

Endothelial H2O2 production in mesenteric arteries was evaluated in the experiments using a laser confocal microscope loaded with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCF), a peroxide-sensitive fluorescence dye (14, 21). All experiments were performed in the presence of indomethacin (10−5 M) and l-NNA (10−4 M). In this system, the endothelial monolayer was clearly distinguished from underlying smooth muscle cell layer (Fig. 7, A-C). In WT mice, ACh caused a significant increase in the DCF fluorescence intensity in endothelial cells 6 min after the application (Fig. 7 B). When arterial strip was pretreated with catalase, the ACh-induced increase in DCF fluorescence intensity was abolished (Fig. 7 D). Importantly, the extent of the ACh-induced increase in the DCF fluorescence intensity at the endothelial layer was absent in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, regardless of the presence or absence of the antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine (Fig. 7, E and F). Fig. 7 G summarizes the quantitative analysis of relative DCF fluorescence intensity in response to ACh in WT and n/i/eNOS−/− mice.

Figure 7.

Endothelial production of H2O2 and superoxide in response to ACh. DCF image at the endothelial layer of a WT mouse under basal conditions (A) and after application of ACh (B), and that at the smooth muscle (SM) layer of a WT mouse after ACh application (C). (D) Catalase abolished the endothelial H2O2 production to ACh, and the production was absent in an n/i/eNOS−/− mouse without (E) and in one with hydralazine treatment (F). (G) Quantitative analysis of the endothelial H2O2 production (n = 3–5). **, P < 0.01. DHE image at the endothelial layer of a WT mouse under basal conditions (H) and after application of ACh (I), and that at SM layer of a WT mouse after ACh application (J). Endothelial production of superoxide was absent in an n/i/eNOS−/− mouse (K and L). (M) Quantitative analysis of the endothelial superoxide production (n = 3 each). *, P < 0.05. Bar, 20 μm. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

Endothelial superoxide production

Endothelial superoxide production in mesenteric arteries was evaluated using a laser confocal microscope loaded with dihydroethidium (DHE), an oxidant fluorescent dye (38). All experiments were performed in the presence of indomethacin (10−5 M) and l-NNA (10−4 M). In this system, the endothelial monolayer was clearly distinguished from the underlying smooth muscle cell layer (Fig. 7, H-L). In WT mice, ACh caused a significant increase in the DHE fluorescence intensity in endothelial cells 5 min after the application (Fig. 7, H, I, and M). Importantly, in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, the endothelial production of superoxide in response to ACh was absent (Fig. 7, K, L, and M).

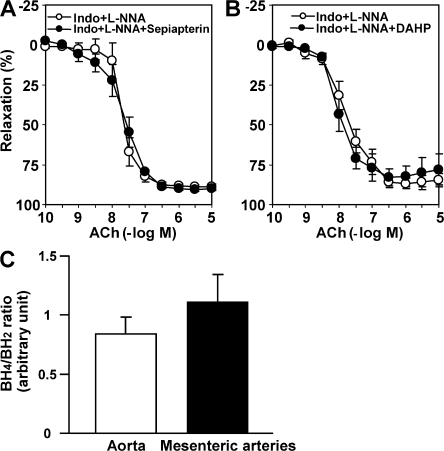

No involvement of pathological NOS uncoupling in EDHF-mediated relaxations

We examined whether pathological NOS uncoupling caused by BH4 deficiency is involved in the EDHF-mediated relaxations in WT mice. Sepiapterin (precursor of BH4, 10−4 M) and 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine (DAHP; GTPCH1 inhibitor, 10−2 M) had no acute effects on EDHF-mediated relaxations (in the presence of indomethacin and l-NNA) of mesenteric arteries from WT mice (Fig. 8, A and B). Furthermore, we measured tissue concentrations of BH4 and dihydrobiopterin (BH2) in the aorta and small mesenteric arteries in mice and used the BH4/BH2 ratio as an index of BH4 bioavailability (39). As shown in Fig. 8 C, the BH4/BH2 ratio, an index of BH4 bioavailability, was not reduced in mesenteric arteries, but instead tended to be increased as compared with the aorta. These results indicate that pathological eNOS uncoupling is not involved in the production of superoxide anions in normal mouse mesenteric arteries.

Figure 8.

No involvement of NOS uncoupling in EDHF-mediated responses. In the presence of indomethacin and l-NNA, the precursor of BH4, sepiapterin (A) or the GTPCH1 inhibitor DAHP (B) did not change EDHF-mediated relaxations of mesenteric arteries from WT mice (n = 6–7). (C) The BH4/BH2 ratio was comparable between the aorta and mesenteric arteries from WT mice (n = 4). To generate sufficient amount of total protein, the aorta and mesenteric arteries were pooled from three mice. This pool was considered as n = 1. 4 individual pools of a total of 12 different mice were used to extract protein, which yielded a total of n = 4. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

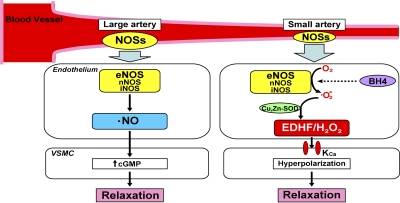

In this study, we were able to demonstrate that endothelial NOSs system has diverse vasodilator functions depending on the vessel size, mainly contributing to EDHF/H2O2 responses in microvessels (small mesenteric arteries) while serving as a NO-generating system in large arteries (the aorta; Fig. 9). Thus, the study provides a novel concept on the diverse roles of the endothelial NOSs system to modulate vascular tone, which is apparently dependent on vessel size (Fig. 9). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrates that disruption of certain genes (NOSs) abolishes EDHF-mediated responses.

Figure 9.

Summary of this study. NO mediates vascular relaxation of relatively large, conduit arteries (e.g., aorta and epicardial coronary arteries), whereas EDHF plays an important role in modulating vascular tone in small, resistance arteries (e.g., small mesenteric arteries and coronary microvessels). All three NOS isoforms (nNOS, iNOS, and eNOS), especially eNOS, produce NO and superoxide anions, and the latter is dismutated by Cu,Zn-SOD to EDHF/H2O2. EDHF hyperpolarizes VSMCs by opening KCa channels, and then elicits vasodilation. On the other hand, superoxide anions from uncoupled NOSs may not significantly contribute to EDHF-mediated relaxations. Collectively, this study provides a novel concept on the diverse roles of endothelial NOSs system mainly contributing to the EDHF/H2O2 responses in microvessels while serving as NO-generating system in large arteries.

In WT mice, endothelium-dependent relaxations of small mesenteric arteries were mainly mediated by EDHF, whereas those of the aorta were mediated by NO, a finding that is consistent with our previous studies (2, 4, 14). Interestingly, EDHF-mediated relaxations were progressively reduced in accordance with the number of disrupted NOS genes in mesenteric arteries and were absent in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, indicating that EDHF-mediated relaxations are totally mediated by the endothelial NOSs system in mouse mesenteric arteries.

In this study, after the classical definition of EDHF (1–3), we evaluated EDHF-mediated responses in mouse mesenteric arteries in the presence of indomethacin and l-NNA. It is known that eNOS generates superoxide anions under normal conditions from reductase domain and only when uncoupled (e.g., BH4 and/or l-arginine depletion) from the oxidase domain, and that l-arginine analogues only inhibit the latter process (40). Indeed, we were able to demonstrate that endothelial superoxide generation was significantly increased in response to ACh in WT mice, whereas in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, this endothelial production of superoxide to ACh was absent, indicating that superoxide anions derived from NOS leads to endothelial formation of EDHF/H2O2 in WT mice. On the other hand, the residual dilation after blocking all three pathways in WT mice was greater than when blocking the same pathways in eNOS−/− mice. It has been reported that l-NNA dose not completely inhibit NOSs (41, 42). It is thus conceivable that the residual dilation after blocking all three pathways in male WT mice may reflect uninhibited NO-mediated responses.

In this study, in n/eNOS−/− mice, some EDHF-mediated responses remained. It is known that iNOS is commonly induced by endotoxins and cytokines, producing NO independently of calcium influx. However, it has also been reported that the activation of iNOS requires Ca2+ (43, 44). Furthermore, in our study, the expression of iNOS in mesentery was significantly increased in n/eNOS−/− mice compared with WT or eNOS−/− mice. These findings suggest that residual EDHF-mediated dilation in n/eNOS−/− mice could be caused by Ca2+-dependent iNOS activity.

It has been reported that in skeletal muscle arterioles of female eNOS−/− mice, EDHF-mediated responses were rather increased (45). However, in this study, no such gender-specific differences were noted in the whole range of genotypes of NOSs−/− mice. The discrepancy between the previous study (45) and this study might be caused by the differences in blood vessels used (skeletal muscle arterioles vs. small mesenteric arteries), method of blood vessel preparation used (pressurized vs. nonpressurized) and analysis performed for the EDHF responses (pharmacological analysis alone vs. pharmacological/electrophysiological study).

The reduced EDHF-mediated responses in NOSs−/− mice could be caused by mechanism(s) other than reduced production of the factor. First, vasodilator properties of vascular smooth muscle might be impaired in NOSs−/− mice. However, in the NOSs−/− mice of both genders, endothelium-independent relaxations to NS-1619, a KCa opener, were preserved and those to SNP were rather enhanced, a finding consistent with the previous reports with eNOS−/− mice (14, 46). Second, the reduced EDHF-mediated responses in n/i/eNOS−/− mice could be a result of the elevated blood pressure. However, the antihypertensive treatment with hydralazine failed to improve the reduced EDHF-mediated relaxations in those mice. Third, the enhanced production of superoxide anions in n/i/eNOS−/− mice from intracellular sources other than eNOS might interfere with EDHF responses. Indeed, we have confirmed that cardiac superoxide production is markedly enhanced in our n/i/eNOS−/− mice (unpublished findings) and, in this study, we also noted that the activities of superoxide anion scavenging enzymes, including Cu,Zn-SOD, catalase, and GPx, were all enhanced. This issue needs to be further examined in future studies.

In this study, in WT mice, the eNOS immunoreactivity was noted mainly in the endothelium of mesenteric arteries, whereas in eNOS−/−and n/eNOS−/− mice, immunoreactivities of other NOSs that had not been disrupted were observed in the endothelium of the blood vessels. In n/i/eNOS−/− mice, none of the NOS isoforms was noted, as expected. These results support our hypothesis that the endothelial NOSs system is substantially involved in EDHF-mediated responses. On the other hand, in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), muscarinic receptors exist and it is possible that ACh might act there to elicit vasomotor responses through EDHF. However, we (14) and others (47) confirmed that in endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries of normal mice, ACh-induced relaxation is absent, indicating that a sufficient amount of functional NOS to cause vasodilation does not exist in VSMC. Furthermore, in this study, the eNOS immunoreactivity was markedly less in the vascular smooth muscle compared with the endothelial layer (Fig. 4).

The confocal microscopy study with DCF and DHE staining demonstrated that endothelial production of H2O2 and superoxide in response to ACh was absent in n/i/eNOS−/− mice, further confirming the important role of the endothelial NOSs system in the synthesis of EDHF/H2O2. We have previously demonstrated that catalase-sensitive EDHF responses and endothelial H2O2 production still remained in singly eNOS−/− mice (14). Thus, these findings support our hypothesis that superoxide anions derived from endothelial NOSs system appear to be the main source of EDHF/H2O2 production from the endothelium.

Recent evidence suggests that BH4-dependent eNOS uncoupling may be an important mechanism that causes endothelial dysfunction and increased superoxide production in vascular diseases (48, 49). However, in this study with normal mouse mesenteric arteries, sepiapterin or DAHP had no acute effects on EDHF-mediated relaxations. Furthermore, it has been reported that endothelial production of superoxide anions from eNOS is noted even under physiological conditions in the absence of BH4 deficiency (40). Indeed, in this study, we were able to demonstrate that the BH4/BH2 ratio was comparable between the aorta and mesenteric arteries in WT mice, suggesting that superoxide from physiological (coupled) NOSs is the major source of EDHF/H2O2 with preserved BH4 bioavailability (Fig. 9).

Several limitations should be mentioned for this study. First, in this study, although we were able to demonstrate the diverse roles of endothelial NOSs system depending on the vessel size, the detailed molecular mechanism(s) for it remains to be elucidated in future studies (Fig. 9). Second, although we were able to demonstrate the endothelial production of H2O2 and superoxide anions using confocal microscopy with DCF and DHE, respectively, we were unable to quantify the H2O2 and superoxide production caused by technical difficulties and limited availability of mesenteric microvessels for the measurement. However, we have previously demonstrated with an electron spin resonance method that endothelial cells produce H2O2, at least in micromolar concentrations, in porcine coronary microvessels under physiological conditions upon agonist stimulation, which should be enough to cause EDHF-type vasodilatation (16). Third, although we were able to demonstrate the important role of endothelial NOSs system in EDHF-mediated responses in vitro, the in vivo importance of the system remains to be examined in future studies. Fourth, vascular endothelial cells have several intracellular sources other than NOSs to produce superoxide anions that are dismutated to H2O2, including NAD(P)H oxidase, mitochondrial electron transport chain, lipoxygenase, and xanthine oxidase (50). In this study, we did not examine the contribution of superoxide anions derived from intracellular sources other than the endothelial NOSs system to EDHF-mediated relaxations. Fifth, although we demonstrated the important role of endothelial NOSs system in EDHF-mediated responses, we did not test our hypothesis using endothelial cell-specific NOSs−/− mice. In this study, however, we examined endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent responses separately, and confirmed that endothelium-independent responses were unaltered in the three genotypes of NOS−/− mice.

This study may have important clinical implications. EDHF plays an important role in human arteries, especially in microvessels, and its vasodilator effects are impaired in several disease states, such as aging and hypercholesterolemia, with a resultant microvascular dysfunction (5). Our n/i/eNOS−/− mice are characterized by the phenotypes resembling metabolic syndrome in humans, which is not evident in singly eNOS−/− mice (35). Thus, the novel concept of this study on the diverse roles of endothelial NOSs system may provide the basis of new therapeutic strategy for the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular diseases (Fig. 9).

In conclusion, this study provides a novel concept on the diverse roles of the endothelial NOSs system contributing to the EDHF/H2O2 responses in microvessels while serving as a NO-generating system in large arteries (Fig. 9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and tissue preparation.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Committee on Ethics of Animal Experiments of Tohoku University and Kyushu University. 10–16-wk-old male and female mice were used. The eNOS−/− mice were originally provided by P. Huang (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). We generated n/i/eNOS−/− mice by crossing doubly NOSs−/− mice, as previously reported (34). Some n/i/eNOS−/− mice were treated with hydralazine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg/day in drinking water for 1 wk). Systolic blood pressure was measured by tail-cuff method.

Organ chamber experiments.

Isometric tension was recorded using isolated small mesenteric arteries (200–250 μm) and aorta as previously described (14, 21). The contributions of vasodilator prostaglandins, NO, and EDHF to ACh-induced endothelium-dependent relaxations were determined by the inhibitory effect of indomethacin, l-NNA, and a combination of charybdotoxin and apamin, respectively (14, 21). To examine the effect of NOS uncoupling on EDHF-mediated responses, additional experiments were performed in small mesenteric arteries using sepiapterin and DAHP. To compare the relaxation curve, we used area under the curve. All agents were applied to organ chambers 30 min before precontraction with prostaglandin F2α.

Electrophysiological experiments.

The rings of small mesenteric arteries were placed in experimental chambers perfused with Krebs solution containing indomethacin and l-NNA. A fine glass capillary microelectrode was impaled into the smooth muscle from the adventitial side of mesenteric arteries, and changes in membrane potentials produced by ACh were continuously recorded (14, 21).

Immunostaining for NOSs.

Mesenteric arteries were fixed by immersion in a solution of 1% paraformaldehyde. After washing in PBS containing 0.45 M sucrose, the vascular strips were embedded in an OCT compound and cut into 3-μm-thick slices (4). After dehydration, the sections for eNOS immunostaining were stained using the Vector M.O.M. immunodetection kit (Vector Laboratories). The mouse monoclonal eNOS antibody (Transduction Laboratories) was applied at a dilution of 1:500. The rabbit polyclonal nNOS antibody (Zymed Laboratories) and rabbit polyclonal iNOS antibody (Abcam) were applied at a dilution of 1:500 and 1:100, respectively, and incubated overnight at 4°C, after which these sections were stained using the avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex.

Cu,Zn-SOD activity.

Cu,Zn-SOD activity was examined using a nitroblue tetrazolium method (51). The extract protein from the mesentery (40 μg) was separated on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. The Cu,Zn-SOD activity was visualized by initially soaking the gel in nitroblue tetrazolium, followed by incubation in a solution of potassium phosphate buffer containing riboflavin and tetramethyl-ethylenediamine (21, 51).

Catalase and GPx activity.

Catalase and GPx activities of the extract protein from mesentery were measured using catalase assay kit and GPx assay kit (Cayman Chemical Company).

Western blot analysis for three NOS isoforms, Cu,Zn-SOD, catalase, and GPx.

The extract protein from the mesentery (20 μg) was loaded for SDS-PAGE immunoblot analysis. The regions containing three NOS isoforms, Cu,Zn-SOD, catalase, GPx, and β-actin were detected with antibodies and visualized using ECL or ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System (GE Healthcare).

Detection of H2O2 and superoxide production from endothelial cells.

Small mesenteric arteries were cut into rings and then opened longitudinally. The vascular strip was incubated with 5 μM DCF or DHE for 15 min and observed using a laser confocal microscope (LSM 510 META; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm at 25°C (14, 21) or (C1; Nikon) at an excitation wavelength of 543 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm (38). Fluorescence images of the endothelium were obtained before and 6 min (DCF) or 5 min (DHE) after application of 10 μM ACh. Relative fluorescence intensity was calculated using images obtained under basal conditions without ACh. The inhibitory effect of pretreatment with catalase (1,250 U/ml) on the ACh-induced increase in fluorescence intensity was determined (14).

BH4 and BH2 measurement.

Isolated vessels were homogenized in 0.5 M perchloric acid containing 0.1 mM disodium EDTA and 0.1 mM Na2S2O3 for protein separation. After centrifugation (20,000× g for 10 min) and filtration, we measured BH4 and BH2 concentrations using HPLC. In brief, by post-column NaNO2 oxidation with a reversed-phase ion-pair LC system, pterins were detected fluorometrically at a wavelength of 350 nm for excitation and 440 nm for emission (LC-10 series; Shimadzu) (52).

Drugs and solution.

The ionic composition of Krebs solution was as follows (mM); Na+ 144, K+ 5.9, Mg2+ 1.2, Ca2+ 2.5, H2PO4− 1.2, HCO3− 24, Cl− 129.7, and glucose 5.5. DCF and DHE were obtained from Invitrogen. Other drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies to GPx and β-actin were obtained from Abcam, catalase antibody from Epitomics Inc., and Cu,Zn-SOD antibody from Stressgen Biotechnologies Corp.

Statistical analysis.

Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Dose–response curve was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] followed by Scheffe's post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. The relative contribution of EDHF to the endothelium-dependent relaxations was analyzed by Bonferroni/Dunn test. Other values were analyzed by paired and unpaired Student's t test or one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. T. Fujiki and E. Gunshima of Kyushu University and F. Tatebayashi and N. Yamaki of Tohoku University for their collaboration.

This study was supported in part by grants-in-aid (Nos. 15256003 and 16209027) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Tokyo, Japan.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: ACh, acetylcholine; BH2, dihydrobiopterin; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; Cu,Zn-SOD, copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase; DAHP, 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine; DCF, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydro-fluorescein diacetate; DHE, dihydroethidium; EDHF, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor; eNOS, endothelial NOS; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GTPCH1, GTP cyclohydrolase-1; iNOS, inducible NOS; KCa, calcium-activated potassium; l-NNA, Nω-nitro-l-arginine; NO, nitric oxide; NOS; NO synthase; nNOS, neuronal NOS; PGI2, prostacyclin; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

References

- 1.Félétou, M., and P.M. Vanhoutte. 2006. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: where are we now? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26:1215–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimokawa, H. 1999. Primary endothelial dysfunction: atherosclerosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 31:23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busse, R., G. Edwards, M. Félétou, I. Fleming, P.M. Vanhoutte, and A.H. Weston. 2002. EDHF: bringing the concepts together. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimokawa, H., H. Yasutake, K. Fujii, M.K. Owada, R. Nakaike, Y. Fukumoto, T. Takayanagi, T. Nagao, K. Egashira, M. Fujishima, and A. Takeshita. 1996. The importance of the hyperpolarizing mechanism increases as the vessel size decreases in endothelium-dependent relaxations in rat mesenteric circulation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 28:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urakami-Harasawa, L., H. Shimokawa, M. Nakashima, K. Egashira, and A. Takeshita. 1997. Importance of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in human arteries. J. Clin. Invest. 100:2793–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feletou, M., and P.M. Vanhoutte. 1988. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization of canine coronary smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 93:515–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, G., H. Suzuki, and A.H. Weston. 1988. Acetylcholine releases endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor and EDRF from rat blood vessels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 95:1165–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosolowsky, M., and W.B. Campbell. 1993. Role of PGI2 and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in relaxation of bovine coronary arteries to arachidonic acid. Am. J. Physiol. 264:H327–H335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisslthaler, B., R. Popp, L. Kiss, M. Potente, D.R. Harder, I. Fleming, and R. Busse. 1999. Cytochrome P450 2C is an EDHF synthase in coronary arteries. Nature. 401:493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards, G., K.A. Dora, M.J. Gardener, C.J. Garland, and A.H. Weston. 1998. K+ is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in rat arteries. Nature. 396:269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beny, J.L., and O. Schaad. 2000. An evaluation of potassium ions as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in porcine coronary arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131:965–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor, H.J., A.T. Chaytor, W.H. Evans, and T.M. Griffith. 1998. Inhibition of the gap junctional component of endothelium-dependent relaxations in rabbit iliac artery by 18-alpha glycyrrhetinic acid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 125:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto, Y., H. Fukuta, Y. Nakahira, and H. Suzuki. 1998. Blockade by 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid of intercellular electrical coupling in guinea-pig arterioles. J. Physiol. 511:501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matoba, T., H. Shimokawa, M. Nakashima, Y. Hirakawa, Y. Mukai, K. Hirano, H. Kanaide, and A. Takeshita. 2000. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 106:1521–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matoba, T., H. Shimokawa, H. Kubota, K. Morikawa, T. Fujiki, I. Kunihiro, Y. Mukai, Y. Hirakawa, and A. Takeshita. 2002. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in human mesenteric arteries. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290:909–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matoba, T., H. Shimokawa, K. Morikawa, H. Kubota, I. Kunihiro, L. Urakami-Harasawa, Y. Mukai, Y. Hirakawa, T. Akaike, and A. Takeshita. 2003. Electron spin resonance detection of hydrogen peroxide as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in porcine coronary microvessels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23:1224–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miura, H., J.J. Bosnjak, G. Ning, T. Saito, M. Miura, and D.D. Gutterman. 2003. Role for hydrogen peroxide in flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles. Circ. Res. 92:e31–e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yada, T., H. Shimokawa, O. Hiramatsu, T. Kajita, F. Shigeto, M. Goto, Y. Ogasawara, and F. Kajiya. 2003. Hydrogen peroxide, an endogenous endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor, plays an important role in coronary autoregulation in vivo. Circulation. 107:1040–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yada, T., H. Shimokawa, O. Hiramatsu, Y. Haruna, Y. Morita, N. Kashihara, Y. Shinozaki, H. Mori, M. Goto, Y. Ogasawara, and F. Kajiya. 2006. Cardioprotective role of endogenous hydrogen peroxide during ischemia-reperfusion injury in canine coronary microcirculation in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291:H1138–H1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacza, Z., M. Puskar, B. Kis, J.V. Perciaccante, A.W. Miller, and D.W. Busija. 2002. Hydrogen peroxide acts as an EDHF in the piglet pial vasculature in response to bradykinin. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283:H406–H411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morikawa, K., H. Shimokawa, T. Matoba, H. Kubota, T. Akaike, M.A. Talukder, M. Hatanaka, T. Fujiki, H. Maeda, S. Takahashi, and A. Takeshita. 2003. Pivotal role of Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase in endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization. J. Clin. Invest. 112:1871–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morikawa, K., T. Fujiki, T. Matoba, H. Kubota, M. Hatanaka, S. Takahashi, and H. Shimokawa. 2004. Important role of superoxide dismutase in EDHF-mediated responses of human mesenteric arteries. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 44:552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ignarro, L.J., G. Cirino, A. Casini, and C. Napoli. 1999. Nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the vascular system: an overview. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 34:879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mungrue, I.N., M. Husain, and D.J. Stewart. 2002. The role of NOS in heart failure: lessons from murine genetic models. Heart Fail. Rev. 7:407–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanhoutte, P.M. 1989. Endothelium and control of vascular function. State of the art lecture. Hypertension. 13:658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furchgott, R.F., and P.M. Vanhoutte. 1989. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. FASEB J. 3:2007–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncada, S., R.M. Palmer, and E.A. Higgs. 1991. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamping, K.G., D.W. Nuno, E.G. Shesely, N. Maeda, and F.M. Faraci. 2000. Vasodilator mechanisms in the coronary circulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 279:H1906–H1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang, A., D. Sun, E.G. Shesely, E.M. Levee, A. Koller, and G. Kaley. 2002. Neuronal NOS-dependent dilation to flow in coronary arteries of male eNOS-KO mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282:H429–H436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morishita, T., M. Tsutsui, H. Shimokawa, M. Horiuchi, A. Tanimoto, O. Suda, H. Tasaki, P.L. Huang, Y. Sasaguri, N. Yanagihara, and Y. Nakashima. 2002. Vasculoprotective roles of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. FASEB J. 16:1994–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yogo, K., H. Shimokawa, H. Funakoshi, T. Kandabashi, K. Miyata, S. Okamoto, K. Egashira, P. Huang, T. Akaike, and A. Takeshita. 2000. Different vasculoprotective roles of NO synthase isoforms in vascular lesion formation in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20:E96–E100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alp, N.J., and K.M. Channon. 2004. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by tetrahydrobiopterin in vascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laursen, J.B., M. Somers, S. Kurz, L. McCann, A. Warnholtz, B.A. Freeman, M. Tarpey, T. Fukai, and D.G. Harrison. 2001. Endothelial regulation of vasomotion in apoE-deficient mice: implications for interactions between peroxynitrite and tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 103:1282–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morishita, T., M. Tsutsui, H. Shimokawa, K. Sabanai, H. Tasaki, O. Suda, S. Nakata, A. Tanimoto, K.Y. Wang, Y. Ueda, et al. 2005. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in mice lacking all nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:10616–10621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakata, S., M. Tsutsui, H. Shimokawa, O. Suda, T. Morishita, K. Shibat, Y. Yatera, K. Sabanai, A. Tanimoto, M. Nagasaki, et al. 2008. Spontaneous myocardial infarction in mice lacking all nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Circulation. 117:2211–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimokawa, H., and K. Morikawa. 2005. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium- derived hyperpolarizing factor in animals and humans. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39:725–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Félétou, M., and P.M. Vanhoutte. 2004. EDHF: new therapeutic targets? Pharmacol. Res. 49:565–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukui, S., Y. Fukumoto, J. Suzuki, K. Saji, J. Nawata, S. Tawara, T. Shinozaki, Y. Kagaya, and H. Shimokawa. 2008. Long-term inhibition of Rho-kinase ameliorates diastolic heart failure in hypertensive rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 51:317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vásquez-Vivar, J., P. Martásek, J. Whitsett, J. Joseph, and B. Kalyanaraman. 2002. The ratio between tetrahydrobiopterin and oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues controls superoxide release from endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an EPR spin trapping study. Biochem. J. 362:733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stuehr, D., S. Pou, and G.M. Rosen. 2001. Oxygen reduction by nitric-oxide synthases. J. Biol. Chem. 276:14533–14536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCall, T.B., M. Feelisch, R.M. Palmer, and S. Moncada. 1991. Identification of N-iminoethyl-L-ornithine as an irreversible inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase in phagocytic cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 102:234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Traystman, R.J., L.E. Moore, M.A. Helfaer, S. Davis, K. Banasiak, M. Williams, and P.D. Hurn. 1995. Nitro-L-arginine analogues. Dose- and time-related nitric oxide synthase inhibition in brain. Stroke. 26:864–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens-Truss, R., and M.A. Marletta. 1995. Interaction of calmodulin with the inducible murine macrophage nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 34:15638–15645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gribovskaja, I., K.C. Brownlow, S.J. Dennis, A.J. Rosko, M.A. Marletta, and R. Stevens-Truss. 2005. Calcium-binding sites of calmodulin and electron transfer by inducible nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 44:7593–7601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang, A., D. Sun, M.A. Carroll, H. Jiang, C.J. Smith, J.A. Connetta, J.R. Falck, E.G. Shesely, A. Koller, and G. Kaley. 2001. EDHF mediates flow-induced dilation in skeletal muscle arterioles of female eNOS-KO mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280:H2462–H2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faraci, F.M., C.D. Sigmund, E.G. Shesely, N. Maeda, and D.D. Heistad. 1998. Responses of carotid artery in mice deficient in expression of the gene for endothelial NO synthase. Am. J. Physiol. 274:H564–H570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding, H., P. Kubes, and C. Triggle. 2000. Potassium- and acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 129:1194–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuzkaya, N., N. Weissmann, D.G. Harrison, and S. Dikalov. 2003. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 278:22546–22554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landmesser, U., S. Dikalov, S.R. Price, L. McCann, T. Fukai, S.M. Holland, W.E. Mitch, and D.G. Harrison. 2003. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 111:1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li, J.M., and A.M. Shah. 2004. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 287:R1014–R1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Machida, Y., T. Kubota, N. Kawamura, H. Funakoshi, T. Ide, H. Utsumi, Y.Y. Li, A.M. Feldman, H. Tsutsui, H. Shimokawa, and A. Takeshita. 2003. Overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases production of hydroxyl radical in murine myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 284:H449–H455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takaya, T., K. Hirata, T. Yamashita, M. Shinohara, N. Sasaki, N. Inoue, T. Yada, M. Goto, A. Fukatsu, T. Hayashi, et al. 2007. A specific role for eNOS-derived reactive oxygen species in atherosclerosis progression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27:1632–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]