Abstract

Lactone-hydrolyzing enzymes derived from some Bacillus species are capable of disrupting quorumsensing in bacteria that use N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as intercellular signaling molecules. Despite the promise of these quorum-quenching enzymes as therapeutic and anti-biofouling agents, the ring opening mechanism and the role of metal ions in catalysis have not been elucidated. Labeling studies using 18O, 2H, and the AHL lactonase from Bacillus thuringiensis implicate an addition-elimination pathway for ring opening in which a solvent-derived oxygen is incorporated into the product carboxylate, identifying the alcohol as the leaving group. 1H-NMR is used to show that metal binding is required to maintain proper folding. A thio effect is measured for hydrolysis of N-hexanoyl-l-homoserine lactone and the corresponding thiolactone by AHL lactonase disubstituted with alternative metal ions including Mn2+, Co2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+. The magnitude of the thio effect on kcat values and the thiophilicity of the metal ion substitutions vary in parallel and are consistent with a kinetically significant interaction between the leaving group and the active-site metal center during turnover. X-ray absorption spectroscopy confirms that dicobalt substitution does not result in large structural perturbations at the active-site. Finally, substitution of the dinuclear metal site with Cd2+ results in a greatly enhanced catalyst that can hydrolyze AHLs 1600 to 24000-fold faster than other reported quorum-quenching enzymes.

Chronic lung infections are a major health concern for patients with cystic fibrosis (1). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia are two of the most common bacterial pathogens that can form recalcitrant mixed species biofilms on lung surfaces (2, 3). The N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone (AHL) 1-mediated quorum-sensing pathways of these bacteria have been experimentally linked to their coordinated expression of virulence factors and to mature biofilm development (4). To combat these infections, “quorum-quenching” reagents that can disrupt the quorum-sensing pathways of these organisms have been suggested as novel therapeutics (5). In addition to small molecule antagonists (6), several classes of enzymes capable of catalytically metabolizing AHLs have been reported. Enzymes that cleave the N-acyl bond of AHLs (AHL acylases, Scheme 1a) have been found in several different types of bacteria including a Ralstonia strain XJ12B, pseudomonads, and a Streptomyces species (7-9). Alternatively, humans and other mammals carry several paraoxonase isozymes capable of breaking a different bond by catalyzing a hydrolytic ring opening (Scheme 1b) (10, 11). However AHLs are not the preferred substrates of human paraoxonases, which have a 102 to 106-fold higher specific activity for non-AHL substrates (11).

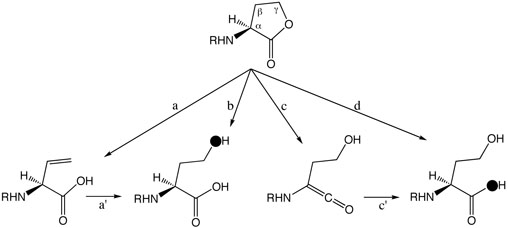

Scheme 1.

Enzymic hydrolysis of quorum-sensing AHL signals by a) AHL acylases, which target the amide bond for hydrolysis or b) paroxonases and AHL lactonases, which target the lactone bond for hydrolysis. Either pathway yields inactive products.

The most active quorum-quenching agents discovered to date are naturally-occurring AHL lactonases (metallo-γ-lactonases) from certain Bacillus species, which can block quorum-sensing dependent processes in several in vivo systems by catalyzing the hydrolytic ring opening of AHLs (12-14). For example, expression of AHL lactonase in the human pathogen P. aeruginosa resulted in large decreases in virulence gene expression and swarming motility (15). Expression of AHL lactonase in Burkholderia species can also attenuate virulence (16, 17). In agricultural applications, the expression of AHL lactonase in transgenic tobacco leaves and potatoes significantly enhances resistance against Erwinia carotovora infections, a pathogen reliant on AHL-mediated quorum-sensing for its virulence (13). The monomeric AHL lactonase produced by Bacillus thuringiensis belongs to the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily, and is purified with two tightly-bound metal ions shown to be essential for activity (18, 19).

Despite the promise of this enzyme as a potential therapeutic agent, and the publication of several high-resolution X-ray crystal structures (18, 20), little is understood about the AHL lactonase mechanism. The role of metal ions in the catalytic mechanism has been disputed (21), and the mechanism that this enzyme uses to open the AHL ring is undefined. A larger question of significant interest to the entire metallo-β-lactamase superfamily is whether the dinuclear metal sites in these enzymes can use their metal ions for leaving-group stabilization (22). The studies described herein provide evidence consistent with an addition-elimination pathway for ring opening, identify the product's alcohol as the leaving-group, show that the metal ions associated with AHL lactonase are required for proper protein folding, and use a thio effect to reveal a kinetically significant interaction between the leaving-group and the metal center during turnover. These studies establish a foundation for designing more effective therapeutic and anti-biofouling biocatalysts for use against quorum-sensing organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and all restriction enzymes were acquired from New England BioLabs (Beverly, MA). D2O (99.9 %) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, and H2 18O (95 %) from Isotec (Miamisburgh, OH). Metal analysis of purified proteins was completed using inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry as described previously (19). The catalytic activities of dizinc and alternative metal-containing AHL lactonases were quantified using a continuous spectrophotometric phenol red-based assay as described previously (19).

Enzyme-catalyzed incorporation of 18O from H2 18O into the N-hexanoyl-l-homoserine product

A reaction buffer (1 mL) containing 50 % H2 18O / 50 % H2 16O was prepared by mixing KH2PO4 buffer (40 mM, 0.47 mL) in H2 16O, pH 7.4, with H2 18O (95%, 0.53 mL). To this solution was added N-hexanoyl-(S)-homoserine lactone [C6-HSL, synthesized as reported earlier (19)] (0.5 M, 20 μL) in a methanol stock solution. AHL lactonase (6.5 μg) was added, and the mixture was allowed to react at room temperature for 1 h after which the reaction was stopped by freezing in liquid N2, and the solvent removed under vacuum using a speedvac (Eppendorf). The remaining solid residue was re-dissolved in D2O (99.9 %, 1 mL) and incubated at 25° C for 1 day before analysis by 13C-NMR spectroscopy to determine the resulting peaks for product: 13 C NMR (D2O, 500 MHz) δ 13.39, 21.86, 25.21, 30.71, 35.93, 58.84, 62.70, 72.27, 177.05, 179.11, 179.13.

1H-NMR spectroscopy of reaction products after hydrolysis in D2O

Products resulting from enzymic and non-enzymic hydrolysis of C6-HSL in 99.9% D2O (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) KH2PO4 buffer (20 mM, pH 7.86) were compared. The pH was read using a standard electrode and corrected using the equation pD = pH + 0.4 (23). Substrate was added from a stock solution of C6-HSL (0.5 M in methanol-d4). Non-enzymic alkaline hydrolysis of C6-HSL (83.3 mM) was carried out in the buffer described above upon addition of NaOH (105 mM, 1.25 equiv). 1H NMR spectroscopy was performed using a Varian 300 MHz spectrometer before and after hydrolysis. A comparison of the peak integration values for the terminal methyl group in the C6-alkyl chain (3 H, 0.9 ppm) and the lactone ring's α proton (1 H, 4.3 ppm or 4.1 ppm for the closed and open lactone, respectively) was used to determine whether exchange between hydrogen and solvent deuterium occurs at the α position. Investigation of the enzymic reaction utilized C6-HSL (20 mM) in the same deuterated buffer solution described above. 1H NMR spectroscopy was carried out on the sample prior to addition of enzyme. After addition of dizinc AHL lactonase (0.48 mg/mL), the solution was incubated (25° C), and 1H NMR spectra were obtained at various time points (1, 2 and 20 h). Comparison of the peak integration values for the terminal methyl group in the C6-alkyl chain and for the lactone α proton was completed as described above.

1H NMR spectroscopy of dinuclear zinc and apo AHL lactonase

Dinuclear zinc AHL lactonase (final concentration of 1.6 mg / mL) was prepared as described earlier (19) and dialyzed (12-14 KDa MWCO, Spectrapor) against Chelex (Biorad)-treated KH2PO4 buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4), with addition of D2O (10 % v/v). Samples of apo AHL lactonase (final concentration of 1.6 mg / mL) were prepared as described earlier (19) and exchanged into the same buffer described above. One-dimensional (1D) 1H NMR spectra of the dizinc and apo proteins were recorded using a 500 MHz Varian Inova NMR spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance probe and z-axis pulsed field gradient. In each case, the NMR signal from the solvent was suppressed by presaturation.

Synthesis of N-hexanoyl homocysteine thiolactone (C6-HCTL)

In a procedure similar to that reported elsewhere (24), triethylamine (3.0 mL, 21 mmol) was added to a stirred suspension of racemic dl-homocysteine thiolactone hydrochloride (3.0 g, 20 mmol) in dimethylformamide (350 mL) at 0° C. Hexanoyl chloride (3.2 mL, 23 mmol) was added dropwise, and the mixture was allowed to react at room temperature with stirring for 1.5 hours. Solvent was removed by rotary evaporation with heating at ≤ 50° C. The residue was dissolved in isopropanol and purified by column chromatography on silica gel using isopropanol as the mobile phase. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation at 20° C. The remaining residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and washed sequentially with saturated NaHCO3, KHSO4 (1M), and saturated NaCl. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, followed by removal of solvent by rotary evaporation to leave the final product, which shows as one spot by TLC. Rf = 0.83 in isopropanol; Tm = 50 - 53 ° C (uncorrected); 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 0.86 (t, 3H), 1.25 (m, 4H), 1.48 (m, 2H), 2.04-2.12 (m, 3H), 2.36 (m, 1H), 3.25 (m, 1H), 3.35 (m, 1H), 4.57 (m, 1H), 8.12 (broad, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) 13.86, 21.86, 24.85, 26.68, 30.18, 30.86, 35.17, 58.04, 172.30, 205.50; EI-HRMS MH+ calc = 216.0980, MH+ obs = 216.1060.

Expression and purification of metal-substituted AHL lactonases

In order to incorporate different metal ions into AHL lactonase, expression conditions were altered from previous procedures (19). Briefly, BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells harboring the expression plasmid pMAL-t-aiiA (19) were incubated at 37° C with shaking in M9 minimal media [Na2HPO4 (47 mM), KH2PO4 (22 mM), NaCl (8.5 mM), NH4Cl (18.7 mM), MgSO4 (2.0 mM), CaCl2 (0.1 mM), and glucose (0.4 % w/v)] supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) until cells reached an OD600 of 0.5 – 0.7. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and then resuspended in fresh M9 minimal media containing IPTG (0.3 mM), ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and one of the following metal salts (0.5 mM): ZnSO4, CoCl2, CdCl2 or MnSO4. Induction at 25° C was continued with shaking for an additional 16 h, followed by harvesting by centrifugation at 8275g, 4° C, for 30 min. Cell pellets from 2 L of expression culture were resuspended in 50 mL of Tris-HCl buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) with NaCl (100 mM) and stored at −20° C until use.

Unless otherwise noted, all purification procedures were done at 4° C. BioLogic LP protein purification systems (BioRad, Hercules, CA) were used for all chromatographic procedures. Thawed cell pellets were resuspended in 200 mL of Tris-HCl buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) with NaCl (100 mM). Cells were lysed by sonication and the cell debris was removed as described previously (19). The resulting supernatant was loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose FF column (2.5 × 20 cm) equilibrated with Buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), and the column was washed with 200 mL of Buffer A made to 160 mM NaCl. The salt concentration was subsequently increased to 250 mM (NaCl) using a linear gradient. The fractions containing active fusion protein generally eluted at a conductivity near 20 mS/cm (approx 200 mM NaCl). Pooled fractions containing maltose-binding protein (MBP)-AHL lactonase fusion protein were split into two portions and loaded in parallel on two columns (2.5 × 10 cm) of amylose-agarose resin (New England BioLabs) at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min. Each column was washed with 2-3 column volumes of Buffer A made to 100 mM NaCl at a flow rate of < 1 mL/min, and the fusion protein was subsequently eluted at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min using Buffer A made to 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM maltose.

The MBP-AHL lactonase fusion proteins prepared with ZnSO4 or CoCl2 were subsequently cleaved with tobacco etch virus protease and the untagged enzyme was purified as described previously (19). During preliminary cleavage experiments, the MBP-AHL lactonase fusion proteins prepared using CdCl2 or MnSO4 were observed to gradually bind zinc, present in buffers only at trace concentrations, at the expense of either cadmium or manganese binding (data not shown). To avoid the resulting metal heterogeneity in these purified proteins, the lactonases that were grown in media supplemented with either CdCl2 or MnSO4 were not cleaved but rather used as the MBP-fusion proteins for the remaining experiments. It has previously been demonstrated that AHL lactonase is monomeric (18) and that the presence of the MBP tag does not significantly affect catalysis (19).

EXAFS of dinuclear cobalt AHL lactonase

Samples of dicobalt AHL lactonase (ca. 1 mM) containing 10% (v/v) glycerol were loaded in Lucite cuvettes with 6 μm polypropylene windows and frozen rapidly in liquid nitrogen. X-ray absorption spectra were measured at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), beamline X9B, with a Si(111) double crystal monochromator; harmonic rejection was accomplished using a Ni focusing mirror. EXAFS data collection and reduction were performed according to published procedures (19, 25). Spectra were collected on two independently prepared samples. As each data set gave similar results, the two data sets were averaged. The spectra shown (see below) represent the average of the two datasets (16 total scans, 13 detector channels per scan). Background subtracted EXAFS spectra were Fourier transformed over the range k = 1 − 13.6 Å−1; Fourier filtered EXAFS data (ΔR = 0.8 − 2.0 Å for first shell fits, ΔR = 0.1 − 4.5 Å for multiple scattering fits) were then fit using amplitude and phase functions, As(k)exp(−2Rasλ) and øas(k), that were calculated using FEFF v. 8.00 (26). The Co-N scale factor, Sc, and the threshold energy, ΔE0, were determined by fitting the experimental spectrum for bistrispyrazolylborato cobalt(II) (25). These two parameters were then held fixed at their optimal values (Sc = 0.78 and ΔE0 = −21 eV) in subsequent fits to protein data, which varied only Ras and σas 2 for a given shell. Metal-metal (Co-Co) scattering was modeled by fitting calculated amplitude and phase functions to the experimental EXAFS of Co2(sapln)2.

RESULTS

Enzyme-catalyzed incorporation of 18O from H2 18O into the N-hexanoyl-l-homoserine product

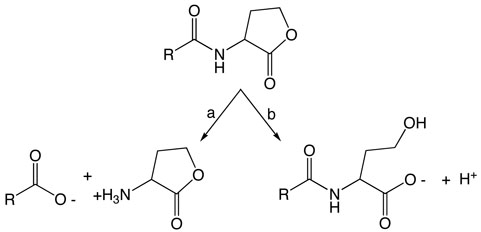

AHL lactonase was used to hydrolyze C6-HSL in a mixture of 50 % H2 18O / 50 % H2 16O in order to detect an isotope-induced shift in the 13C resonance for the carbon adjacent to the site of incorporation (27). To rule out non-enzymatic exchange of H2 18O into the product, after a short incubation (1 h) of substrate with the enzyme, the samples were dried and re-suspended in D2O followed by a long incubation (1 day) before analysis. The presence of a characteristic 18O-isotope induced 13C shift (see below) indicates that there was no significant washout of this position during the D2O incubation following enzymic cleavage. This result is consistent with reports that oxygen exchange reactions with acetic acid in water are acid catalyzed, and only very slow exchange occurs when pH values are greater than 6.0 (28). For the ring-opened product obtained after incubation with AHL lactonase, the 13C-resonance peak for the Cγ methylene carbon at 72.272 ppm, and a split peak for the ring-carbonyl carbon at 179.108 ppm and 179.132 ppm are shown in Figure 1. The magnitude of the new upfield isotope shift observed at 179 ppm is 0.024 ± 0.004 ppm relative to the resonance position of the unlabeled 16O-containing product, consistent with incorporation of one 18O atom into the product carboxylate (27, 29).

Figure 1.

Partial 13C NMR spectra of 18O-labeled product. C6-HSL was hydrolyzed by AHL lactonase in 50 % H218O / 50 % H216O, and two selected regions of the 13C NMR spectrum of the resulting product, N-hexanoyl-L-homoserine, are shown, corresponding to the carboxylic carbon (approx 179 ppm) and the Cγ methylene carbon (approx 72 ppm).

1H-NMR spectroscopy of reaction products after hydrolysis in D2O

To determine whether the lactone α-proton is exchanged with solvent deuterium during catalysis, non-enzymic and AHL lactonase-catalyzed hydrolysis of C6-HSL were completed in deuterated buffer and the reaction products analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. In both cases, peak integration values were compared between the protons of the terminal methyl group of the alkyl chain and the α-proton (see discussion section). These peaks are well-resolved and the protons of the methyl group should not readily exchange with solvent, allowing these values to be set equivalent to 3 protons. In the non-enzymic control reaction, before hydrolysis, the methyl protons (3.0 H, 0.73 ppm) integrated with a 3:1 ratio to the α-proton (1.1 H, 4.25 ppm) of the substrate. After addition of hydroxide, characteristic chemical shifts indicated complete ring opening (data not shown), and the methyl protons (3.0 H, 0.71 ppm) integrated with approximately the same ratio to the α-proton of the product (0.8 H, 4.06 ppm). In the enzyme-catalyzed reaction, complete hydrolysis was observed at the first time point (1 h) and the methyl protons (3.0 H, 0.72 ppm) integrated with a 3:1 ratio to the α-proton of the product (0.9 H, 4.08 ppm). To insure no further reaction, the enzymic reaction was analyzed at later time points (2 h, 20 h). The methyl protons (2 hours: 3.0 H, 0.72 ppm; 20 hours: 3.0 H, 0.73 ppm) and the product's α-proton (2 hours: 1.1 H, 4.08 ppm; 20 hours: 1.2 H, 4.10 ppm) remained in a 3:1 ratio, indicating that there is not significant exchange of the α-proton with solvent deuterium during turnover.

1H NMR spectroscopy of dinuclear zinc AHL lactonase and apo AHL lactonase

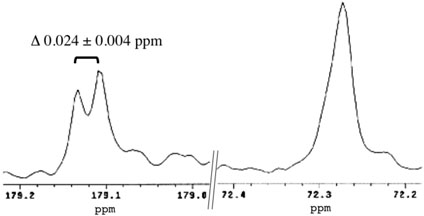

In order to determine whether removal of metal ions from AHL lactonase resulted in any protein unfolding, 1D 1H-NMR spectra were compared between dizinc and apo AHL lactonase for differences in downfield-shifted resonances typical of folded proteins (30, 31). 1D 1H-NMR spectroscopy is commonly used to qualitatively determine whether a protein is folded or unstructured (30). Dizinc AHL lactonase appears to be well folded, showing peaks for backbone amides shifted downfield of 8.5 ppm (Figure 2A). After removal of the metal ions, most of these downfield peaks disappeared and broader features were present near 8.3 ppm, the characteristic shift of backbone amides in random coils (Figure 2B). It is unlikely that the chelator itself causes unfolding because only modest concentrations are used (2 mM) and because re-addition of metal ions (19), but not removal of the chelators (this work) can recover enzyme activity. These observations are consistent with a significant structural destabilization of AHL lactonase upon, or after, removal of the active-site metal ions.

Figure 2.

Partial one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra of dinuclear zinc AHL lactonase (A) and apo AHL lactonase (B), indicating significant unfolding after removal of metal ions.

Expression and purification of metal-substituted AHL lactonases

Yields of purified untagged AHL lactonase (29 KDa) from 2 L expression cultures were typically greater when the induction media was supplemented with CoCl2 (40 mg) than with ZnSO4 (7 mg). Yields of purified MBP-AHL lactonase fusion proteins (73 KDa) from 2L expression cultures were lower when the induction media was supplemented with CdCl2 (10 mg) or MnSO4 (22 mg). Metal analysis was performed as previously described (19) and confirmed that enzymes grown in each metal supplement resulted in a purified protein containing approximately 2 equivalents of the supplemented metal ion per monomer (Table 1). Several independent expression and purification trials confirmed the reproducibility of these procedures for preparing AHL lactonase that is homogeneously substituted with alternative divalent metal ions.

Table 1.

Metal content of purified monomeric AHL lactonase grown in minimal media with different metal supplements.

| Metal Supplement |

Manganese (equiv) |

Cobalt (equiv) |

Zinc (equiv) |

Cadmium (equiv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnSO4 | 1.8 | < 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| CoCl2 | < 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.2 | < 0.01 |

| ZnSO4 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 2.0 | < 0.01 |

| CdCl2 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 | 2.0 |

Steady-state kinetics of metal-substituted AHL lactonases

Using a previously-reported (19) phenol red-based spectrophotometric activity assay, the steady-state rate constants were measured for hydrolysis of C6-HSL and C6-HCTL at 28° C and pH 7.4 by AHL lactonase disubstituted with manganese, cobalt, zinc, or cadmium (Table 2). Progress curves remained linear over the timescale used for calculating initial rates, typically about 0.2 min. The maximum substrate concentrations used in these experiments were at least 5-fold higher than KM values, except for hydrolysis of C6-HCTL by dizinc AHL lactonase, where the high KM and the limited aqueous solubility of the thiolactone only allowed assays with a maximum near 40 mM substrate.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic constants for hydrolysis of substrates with oxygen (C6-HSL, O) or sulfur (C6-HCTL, S) leaving groups by AHL lactonase disubstituted with various divalent metal ions.a

| Metal Supplement |

C6-HSL |

C6-HCTL |

b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | KM (mM) | kcat (s−1) | KM (mM) | |||

| MnSO4 | 330 ± 20 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 500 ± 20 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.66 ± 0.07 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| CoCl2 | 510 ± 10 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 198 ± 8 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 0.054 ± 0.006 |

| ZnSO2 | 91 ± 3 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 36 ± 10 | 22 ± 5 | 0.16 ± 0.06 |

| CdCl2 | 480 ± 20 | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 100 ± 20 | 2.0 ± 0.6 |

Reactions were carried out at pH 7.4, 28° C.

Ratios compare the relative steady-state kinetic constants for hydrolysis of substrates with an oxygen (O) leaving group, C6-HSL, or with a sulfur (S) leaving group, C6-HCTL.

In general, rankings of the absolute values for steady-state rate constants do not obviously correlate with the Lewis acid strength or thiophilicity of the substituted metal ions. For the C6-HSL substrate, kcat values increased upon substitution by Zn2+ << Mn2+ < Cd2+ < Co2+, and KM values decreased with a different rank order: Zn2+ >> Co2+ > Cd2+ > Mn2+. These absolute rankings are different for the sulfur-containing C6-HCTL substrate, which showed increasing kcat values upon substitution by Zn2+ < Cd2+ << Co2+ < Mn2+, and decreasing KM values with Zn2+ > Co2+ > Mn2+ > Cd2+. In all cases, disubstitution with zinc resulted in the least effective catalyst. These results are somewhat surprising because, in all cases, disubstitution with zinc results in the least effective catalyst. In contrast, zinc appears to be the optimum metal ion for catalysis by a related metallo-β-lactamase (32).

While the trends of these absolute values are difficult to interpret, it is more instructive to compare the ratio of rate constants for the oxygen and sulfur-containing substrates (O/S ratios in Table 2) which can be used to isolate the effects of metal substitution on the leaving group position (see discussion section). The O/S ratio of kcat values for C6-HSL and C6-HCTL showed a clear trend, varying by 150-fold, with the rank order of Mn2+ < Co2+ < Zn2+ < Cd2+. Under our experimental conditions, product inhibition did not significantly contribute to the observed thio effect (Supporting Information). This ranking of O/S kcat ratios matched the trend of reported stability constants for these metal ions binding to small molecule thiols: Mn2+ < Co2+ < Zn2+ < Cd2+ (33-36), and is consistent with an apparent correlation between the ability of these metal ions to bind thiols and their ability to perturb the kcat values of thiolactones as compared to the oxygen congeners.

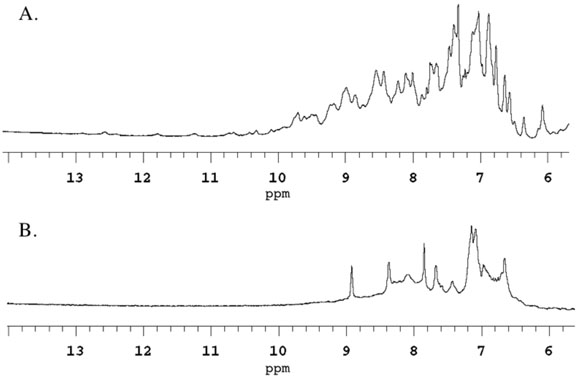

EXAFS of dinuclear cobalt AHL lactonase

Our previous EXAFS studies of dizinc AHL lactonase revealed a dinuclear structure, with an average of 5 N/O donors per zinc ion, including 2 ± 0.5 His ligands, per zinc ion. The Zn-Zn distance of 3.32 Å was taken as evidence of the presence of two bridging groups, including a carboxylate and a solvent molecule (19). To determine whether the changes in reactivity upon metal substitution are a manifestation of structural perturbations, we examined the EXAFS of the dicobalt enzyme.

The data presented in Figure 3 are consistent with similar structures for the dizinc and dicobalt enzymes (the original dizinc spectrum is included for comparison). First shell fits to the dicobalt data, summarized in Table 3, indicate an average of 5 ± 1 N/O donors per cobalt ion, at a distance of 2.03 Å. These results are indistinguishable from those observed for the dizinc enzyme, indicating identical coordination numbers for the Zn and Co ions. Attempts to fit the first shell with a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen donors did not lead to significant improvement in the fit residuals.

Figure 3.

Fourier transformed EXAFS data (solid lines) for dizinc (top) (19) and dicobalt (bottom) AHL lactonase, and corresponding best fits (open diamonds).

Table 3.

EXAFS fitting results for dicobalt AHL lactonase.a

| Fit | Scatterer(b) | Path(c) | Ras (Å) | σas2(d) | Rf(e) | Ru(e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

5 N/O |

2.03 |

7.2 |

27 |

267 |

|

| 2 | 5 N/O | 2.03 | 6.0 | 199 | 201 | |

| 2 His | C1 | 2.98 | 9.0 | |||

| C1-N1 | 3.35 | 6.0 | ||||

| C2-N1 | 4.22 | 15. | ||||

| C1-N2-N1 |

4.67 |

14. |

||||

| 3 | 5 N/O | 2.03 | 6.0 | 146 | 157 | |

| 2 His | C1 | 3.02 | 6.4 | |||

| C1-N1 | 3.38 | 16. | ||||

| C2-N1 | 4.24 | 6.6 | ||||

| C1-N2-N1 | 4.68 | 13. | ||||

| 1 Co | Co | 3.55 | 9.0 |

Values of Ras and σas2 are for fits to filtered data, as described in Materials and Methods. Fits to unfiltered data gave similar results.

Integer coordination number giving the best fit.

Multiple scattering paths represent combined paths, with labels that correspond to the path with largest amplitude (19).

Mean square deviation in absorber-scatterer bond length in 10−3 Å2.

Goodness of fit defined as 1000*, where N is the number of data points. Rf corresponds to fits to filtered data, Ru corresponds to fits to unfiltered data. The apparent similarity of the residuals for filtered and unfiltered fits is an artifact of the Fourier filtering process, which converts real data (unfiltered) into complex data (filtered). This results in an effective doubling of the number of points being fit, leading to apparently higher residuals for fits to filtered data.

Multiple scattering fits indicate the presence of an average of 2 ± 0.5 His ligands per Co(II) ion, also in accord with the dizinc EXAFS (19). These fits adequately reproduce the position of the four prominent outer shell features, but poorly model the intensity pattern, particularly for the feature at R + α = 3.1 Å. Inclusion of a Co-Co interaction dramatically improves the appearance of the fit, more closely matching the observed outer shell intensities. More importantly, addition of the Co-Co interaction (an increase in the number of variable parameters in the fit from 10 to 12) leads to a 27 % improvement in the fit residual. The Co-Co distance refines to 3.55 Å, which is significantly longer than the 3.32 Å Zn-Zn distance observed for dizinc AHL lactonase. This can be accounted for, in part, by the slightly larger (0.06 Å) covalent radius of Co(II) vs. Zn(II), which predicts an increase of up to 0.12 Å in metal-metal distance. The remaining 0.1 Å increase is at most a minor perturbation of the active site structure.

DISCUSSION

Although AHL lactonase holds potential as a therapeutic and anti-biofouling agent, its enzymic ringopening mechanism has not yet been characterized. Generally alkaline ester hydrolysis occurs through an addition-elimination pathway (rather than elimination-addition, or an SN2 pathway). However, lactones are known to have different reactivity than open chain esters (37). For instance, ring sizes less than 8 force the alkyl and acyl groups of the lactone into a cis configuration as opposed to the trans configuration of open-chained esters, and these lactones hydrolyze more than 200-fold faster than their open chain analogs ((38) reviewed in (37)). Besides the expected attack of hydroxide at the carbonyl carbon, alternative mechanisms for AHL lactonase should also be considered. For example, enzymecatalyzed ring opening of type B streptogramin macrolactones have been shown to occur via elimination mechanisms rather than hydrolysis (39). The non-enzymatic hydrolysis of lactones can also occur by different mechanisms. If an ionizable α-proton is present, this may allow deprotonation and elimination of the alcohol to form a ketene that would subsequently react with water to give product. While this mechanism has not been observed in non-enzymic lactone hydrolysis, it has been observed with particular open-chain esters (37, 40, 41). Even differences in the site of bond cleavage have been noted. Under neutral conditions, four membered lactone rings have been shown to open between the methylene carbon and the ring oxygen rather than between the carbonyl carbon and the ring oxygen (reviewed in (41)). This unusual cleavage has even been observed during non-enzymatic acid hydrolysis of N-benzoylhomoserine lactone (42). Because the dinculear metal center of AHL lactonase provides two strong Lewis acids as well as a pre-formed hydroxide ion, it is not clear whether an acidic or an alkaline non-enzymatic hydrolysis mechanism is most appropriate to use as a model. Therefore, the possibility of several alternative pathways for lactone hydrolysis justifies the investigation of the particular ringopening mechanism catalyzed by AHL lactonase.

In light of the known possibilities, we considered four potential ring-opening mechanisms for AHL lactonase (Scheme 2): path a) elimination of the acetate group - the resulting alkene product has not been detected in previous analysis of reaction products (19, 21, 43), but elimination might be followed by hydration (path a') to yield the expected product; path b) attack of hydroxide at the γ-carbon with the acetate acting as a leaving group; path c) deprotonation of the α-proton and elimination of the alcohol to form a ketene, which could readily react (path c') with solvent to yield product; and path d) hydroxide attack at the carbonyl carbon.

Scheme 2.

Possible AHL ring-opening mechanisms by elimination of the acetate (a) possibly followed by hydration (a′); by hydroxide attack at the Cγ-carbon (b); by elimination of the alcohol (c) followed by hydration (c′); or by hydroxide attack at the carbonyl carbon (d). Predicted labeling by solvent [18O]-H2O is indicated (●).

Both pathways a and b are predicted to incorporate solvent oxygen into the product alcohol, but pathways c and d predict incorporation of solvent oxygen into the product's carboxylate. To determine the actual site of incorporation, C6-HSL was hydrolyzed by AHL lactonase in buffered solution containing 50% H2 18O / 50 % H2 16O, and the resulting product was analyzed by natural abundance 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Incorporation of an 18O isotope adjacent to a carbon atom is known to introduce a small but reproducible change in the adjacent carbon's chemical shift (27). After hydrolysis, the product's γ-carbon showes only a single symmetrical peak (Figure 1), with no indication of a neighboring 18O label. However, the product's carbonyl carbon peak is split into two, with approximately 50% of the sample shifted upfield by 0.024 ± 0.004 ppm. The magnitude of the 18O-induced isotope shift agrees with that observed previously with carboxylic acids, and indicates that only one 18O atom is incorporated into the product (29). The observed site of solvent oxygen incorporation into the product carboxylate rather than into the alcohol rules out pathways a and b.

Pathways c and d can be distinguished by washout of the α-proton during hydrolysis. Pathway c predicts that the α-proton should readily exchange with solvent but pathway d predicts this proton would be retained. To determine whether the α-proton is washed out during turnover, C6-HSL was hydrolyzed by AHL lactonase in buffer containing > 95 % D2O and the resulting product analyzed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy. The product's α-proton integrates well with the three protons of the terminal methyl group of the alkyl chain and shows a 1:3 stoichometry, indicating that there is no significant exchange at this position during catalysis. This finding disfavors pathway c. These results do not rule out the formal possibility that a general base, not in rapid equilibrium with the solvent, catalyzes both α-proton removal and reprotonation of the ketene. However, the high pKa of the α-proton and the solvent accessibility of the active site (18) makes this possibility unlikely. In sum, isotope labeling patterns are most consistent with an addition-elimination mechanism with attack of a solvent-derived hydroxide at the carbonyl carbon and elimination of an alcohol leaving group.

Another significant unknown in the AHL lactonase mechanism is the role of metal ions. The absolute requirement of metal ions for the catalytic activity of AHL lactonase has been debated (21). Our group (and others (20)) found two equivalents of Zn2+ that co-purified with this enzyme, and demonstrated that the presence of these metal ions is required for catalytic activity (19). However, loss of activity upon removal of metal ions a) could be caused by protein unfolding, indicating a structural role for the metal ions; b) could be caused by removal of these Lewis acids without significant unfolding, suggesting a catalytic role for the metal ions; or c) could be a combination of these two effects. To determine whether metal ion binding is important for stabilization of the protein fold, we compared qualitative differences between the NMR spectra of dinuclear zinc AHL lactonase and apo AHL lactonase, which no longer contains any bound metal ions (Figure 2). Comparison of 1D 1H NMR spectra is commonly used to qualitatively detect gross changes in protein folding (30). The spectrum of dinuclear zinc AHL lactonase contains many defined peaks, even occurring well above 8.5 ppm, distinctive of the backbone amide protons in folded proteins. In contrast, the spectrum of apo AHL lactonase shows fewer, broader, and less resolved peaks, mostly occurring near 8.3 ppm, indicating a loss (44) of structural integrity upon removal of metal ions. This result is consistent with the dinuclear zinc site serving a structural role in stabilizing the protein fold of AHL lactonase. Indeed, crystal structures of this enzyme show that the dizinc site helps bridge two pseudosymmetrical halves of the overall αββα fold (18, 20), and reconstitution experiments with apo-protein and metal ions are slow to reach equilibrium and only have low yields (19). Other superfamily members have also been shown to rely on metal-ion binding for proper folding (44, 45). While these results support a structural role for the bound metal ions, they do not provide any information as to whether these metals might also play a role in catalysis. In order to determine whether the metal ions of AHL lactonase directly participate in catalysis, experiments are underway to track specific metal-to-substrate interactions that occur throughout the reaction coordinate.

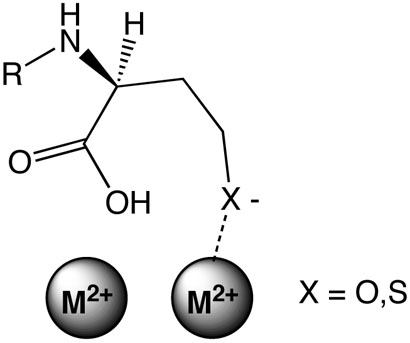

The importance of metal ions to stabilizing the proper fold of AHL lactonase, and the identity of the leaving group have now been established. One of the remaining questions is whether the metal center participates in the catalytic mechanism. Most metallo-β-lactamase superfamily members rely on activesite metal ions for catalysis (46). One structure of AHL lactonase complexed with homoserine lactone indicates ligand-to-metal contacts (20), but this likely represents a non-productive complex. In contrast, early studies of AHL lactonase suggest that metals may not be essential (21), and recent structures of a related dinuclear zinc alkylsulfatase suggest that the active-site metal ions may not interact directly with the substrate (47). Herein, we measured the kinetic thio effect on hydrolysis rates of lactone and thiolactone substrates by AHL lactonase substituted with metals of varying thiophilicity. If the leaving group does not interact with the metal center, then there should be no change in the ratio of hydrolysis rates for the lactone and thiolactone substrates (O/S ratio) upon metal substitution. However, if the leaving group makes a kinetically significant interaction with the metal center, then it would be reasonable to expect that the ratio of hydrolysis rates should vary in parallel with the thiophilicity of the active-site metals. Similar experiments are common in the study of metal-mediated phosphoester hydrolysis (48), and the use of thionolactams (49), thioureas (50) and thionopeptides (34, 51) have also been used to assay for a thio effect on various metallohydrolases. It should be noted that the studies described here are somewhat different than the previous studies because the sulfur-for-oxygen substitution is made at the leaving group position rather than at the carbonyl group.

Steady-state kinetic constants for hydrolysis of C6-HSL and C6-HCTL were determined as catalyzed by AHL lactonase containing two equivalents each of four different metal ions (Tables 1 and 2): Mn2+, Co2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+. The O/S ratios of KM values do not show a clear correlation with the ranking of these metal's thiophilicity, nor is a correlation necessarily expected. However, the O/S ratio of kcat values, which vary by 150-fold, show a strong correlation with the known thiophilicity of the active-site metal ions. The rank order of O/S kcat ratios for metal-substituted AHL lactonase, Cd2+ > Zn2+ > Co2+ > Mn2+ correlates well with the ranking (52) of these metals' thiophilicity: Cd2+ > Zn2+ > Co2+ > Mn2+ (Table 2). In fact, under saturating conditions, the Mn2+-substituted AHL lactonase, expected to be the least thiophilic species, hydrolyzed the thiolactone faster than the oxygen containing congener. In contrast, Cd2+-substituted AHL lactonase, expected to be the most thiophilic species, hydrolyzed the oxygen-containing lactone faster than the thiolactone. The observation that that the most thiophilic metal displays the slowest rate for thiolactone hydrolysis suggests that breaking the leaving group-tometal bond (Figure 4) may be at least partially rate-limiting during steady-state turnover. A similar ratelimiting metal-to-leaving-group interaction has been characterized in related metallo-β-lactamase enzymes (22), although this interaction may be substrate-dependent (53). These findings are consistent with the presence of a kinetically significant interaction between the substrate's leaving group and the active-site metal ions of AHL lactonase during turnover. Future kinetic and spectroscopic studies will address the leaving group-to-metal interaction of AHL lactonase in greater detail and determine which of the two metal ions is responsible for this interaction.

Figure 4.

Proposed metal-to-leaving-group interaction during lactone and thiolactone hydrolysis by AHL lactonase.

In order to insure that the different metal ion substitutions do not cause large structural changes in the dinuclear site, X-ray absorption spectroscopy of the dinuclear cobalt AHL lactonase (Table 3, Figure 3) was compared with that reported earlier for the dizinc enzyme (19). Fits to the EXAFS data indicate identical coordination spheres for both Co(II) and Zn(II) in the AHL lactonase active site, including an average of 5 nitrogen/oxygen ligands per metal ion, 2 ± 0.5 of which are histidine residues. The 3.55 Å cobalt-cobalt distance determined for dicobalt AHL lactonase is slightly longer than the 3.32 Å zinc-zinc distance in the dizinc enzyme, but is still consistent with formation of a dinuclear cobalt metal center. In sum, no major structural differences in the metal binding site are observed by EXAFS between the dicobalt and dizinc AHL lactonase. Therefore, the observed differences in reactivity between dizinc and dicobalt AHL lactonase are likely due to intrinsic differences in each metal's properties rather than changes in the protein structure.

One unexpected benefit of this study is the finding that different metal ions can greatly enhance catalytic rates, with the Cd2+-substituted enzyme showing a 5-fold increase in kcat, a 23-fold decrease in KM and a corresponding 125-fold increase in kcat/KM for hydrolysis of a naturally occurring substrate, C6-HSL, as compared with the dizinc enzyme. This dicadmium catalyst is orders of magnitude faster than other reported quorum-quenching enzymes. For example, the AHL-acylase AhlM (9) is 3200-fold slower, and the human paraoxonases-1, -2 and -3, are 24000-fold, 1600-fold, and 9600-fold slower, respectively (11), than dicadmium AHL lactonase. 2 Further studies will be required to determine whether more physiologically relevant metal ions, such as Fe2+, also afford rate enhancements, and whether the non-physiological alternative metals which display greater activity can remain stably incorporated into AHL lactonase when used in a biological milieu.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the dinuclear metal site of AHL lactonase is essential both for structural stabilization and for catalysis. Substrate AHL ring opening is shown to be consistent with a proposed addition-elimination mechanism where solvent-derived hydroxide, presumably the hydroxide that bridges the dinuclear zinc site, attacks the lactone's carbonyl and an alcohol leaving group is eliminated. An observed thio effect indicates that a kinetically significant interaction between the substrate's leaving group and the metal center occurs during catalysis and is consistent with proposing a role of the metal center in stabilizing the leaving group, thereby facilitating bond cleavage. Because alternative-metal incorporation results in a hyperactive AHL lactonase, this raises the possibility that through an understanding of the structure and mechanism of this enzyme family, more effective quorum-quenching agents can be developed for use as antibacterial and antibiofouling agents.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Prof. David W. Hoffman (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas, Austin) for assistance with the protein 1H-NMR spectra. The National Synchrotron Light Source is supported by the U. S. Department of Energy.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Product synthesis, product inhibition constants, and comparison of product inhibition with the observed thio effect (4 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This research was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Research Scholar Development Award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K22 AI50692 to W.F.), the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1572 to W.F.), the Texas Advanced Research Program (003658-0018-2006 to W.F.), and the BRIN/INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources (RR16480 to D.L.T.).

Abbreviations: AHL, N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone; HSL, homoserine lactone; Hcy, homocysteine; Hse, homoserine; MBP, maltose binding protein; LB, Luria-Bertani; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; HCTL, homocysteine thiolactone; SDS, sodium dodecyl sulfate; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; OD600, optical density at 600 nm; ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; aiiA, the gene for AHL lactonase; bp, base pairs; equiv, equivalents; TEV, tobacco etch virus; TB, Terrific Broth; MWCO, molecular weight cut off; HIC, hydrophobic interaction chromatography; 1D, one dimensional; ESI-HRMS, electrospray ionization high resolution mass spectrometry; TLC, thin layer chromatography; mS milliSiemens; EXAFS, extended X-ray absorption fine structure; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

Kinetic characterizations of quorum-quenching lactonases are scant, but the kcat values of dicadmium AHL lactonase are compared with those calculated from the highest reported specific activities of AhlM and PON1-3, assuming saturating optimal AHL substrates and one active-site per monomer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh PK, Schaefer AL, Parsek MR, Moninger TO, Welsh MJ, Greenberg EP. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature. 2000;407:762–4. doi: 10.1038/35037627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RS, Iglewski BH. P. aeruginosa quorum-sensing systems and virulence. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003;6:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewenza S, Visser MB, Sokol PA. Interspecies communication between Burkholderia cepacia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can. J. Microbiol. 2002;48:707–16. doi: 10.1139/w02-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong YH, Zhang LH. Quorum sensing and quorum-quenching enzymes. J. Microbiol. 2005;43:101–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice SA, McDougald D, Kumar N, Kjelleberg S. The use of quorum-sensing blockers as therapeutic agents for the control of biofilm-associated infections. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2005;6:178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suga H, Smith KM. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial quorum sensing as a new drug target. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003;7:586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin YH, Xu JL, Hu J, Wang LH, Ong SL, Leadbetter JR, Zhang LH. Acyl-homoserine lactone acylase from Ralstonia strain XJ12B represents a novel and potent class of quorum-quenching enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;47:849–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang JJ, Han JI, Zhang LH, Leadbetter JR. Utilization of acyl-homoserine lactone quorum signals for growth by a soil pseudomonad and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:5941–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5941-5949.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Kang HO, Jang HS, Lee JK, Koo BT, Yum DY. Identification of extracellular N-acylhomoserine lactone acylase from a Streptomyces sp. and its application to quorum quenching. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:2632–41. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2632-2641.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang F, Wang LH, Wang J, Dong YH, Hu JY, Zhang LH. Quorum quenching enzyme activity is widely conserved in the sera of mammalian species. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3713–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Draganov DI, Teiber JF, Speelman A, Osawa Y, Sunahara R, La Du BN. Human paraoxonases (PON1, PON2, and PON3) are lactonases with overlapping and distinct substrate specificities. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:1239–47. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400511-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong YH, Gusti AR, Zhang Q, Xu JL, Zhang LH. Identification of quorum-quenching N-acyl homoserine lactonases from Bacillus species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:1754–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1754-1759.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, Park SY, Lee JJ, Yum DY, Koo BT, Lee JK. Genes encoding the N-acyl homoserine lactone-degrading enzyme are widespread in many subspecies of Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:3919–24. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.3919-3924.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong YH, Xu JL, Li XZ, Zhang LH. AiiA, an enzyme that inactivates the acylhomoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal and attenuates the virulence of Erwinia carotovora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3526–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060023897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reimmann C, Ginet N, Michel L, Keel C, Michaux P, Krishnapillai V, Zala M, Heurlier K, Triandafillu K, Harms H, Defago G, Haas D. Genetically programmed autoinducer destruction reduces virulence gene expression and swarming motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbiology. 2002;148:923–32. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulrich RL. Quorum quenching: enzymatic disruption of N-acylhomoserine lactonemediated bacterial communication in Burkholderia thailandensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6173–80. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6173-6180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wopperer J, Cardona ST, Huber B, Jacobi CA, Valvano MA, Eberl L. A quorum-quenching approach to investigate the conservation of quorum-sensing-regulated functions within the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:1579–87. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1579-1587.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu D, Lepore BW, Petsko GA, Thomas PW, Stone EM, Fast W, Ringe D. Three-dimensional structure of the quorum-quenching N-acyl homoserine lactone hydrolase from Bacillus thuringiensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11882–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505255102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas PW, Stone EM, Costello AL, Tierney DL, Fast W. The quorumquenching lactonase from Bacillus thuringiensis is a metalloprotein. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi050050m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MH, Choi WC, Kang HO, Lee JS, Kang BS, Kim KJ, Derewenda ZS, Oh TK, Lee CH, Lee JK. The molecular structure and catalytic mechanism of a quorum-quenching N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17606–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504996102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang LH, Weng LX, Dong YH, Zhang LH. Specificity and enzyme kinetics of the quorum-quenching N-Acyl homoserine lactone lactonase (AHL-lactonase) J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:13645–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrity JD, Bennett B, Crowder MW. Direct evidence that the reaction intermediate of metallo-beta-lactamase L1 is metal bound. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1078–87. doi: 10.1021/bi048385b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glasoe PK, Long FA. Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 1960;64:188–189. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chhabra SR, Harty C, Hooi DS, Daykin M, Williams P, Telford G, Pritchard DI, Bycroft BW. Synthetic analogues of the bacterial signal (quorum sensing) molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone as immune modulators. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:97–104. doi: 10.1021/jm020909n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Periyannan GR, Costello AL, Tierney DL, Yang KW, Bennett B, Crowder MW. Sequential binding of cobalt (II) to metallo-beta-lactamase CcrA. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1313–20. doi: 10.1021/bi051105n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ankudinov AL, Ravel B, Rehr JJ, Condradson SD. Real space multiple scattering calculation and interpretation of XANES. Phys. Rev. B. 1998;58:7565–7576. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risley JM, Van Etten RL. Mechanistic studies utilizing oxygen-18 analyzed by carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 1989;177:376–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)77021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Llewellyn DR, O'Connor C. Tracer studies of carboxylic acids. Part I. Acetic and pivalic acid. J. Chem. Soc. 1964:545–549. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Risley JM, Van Etten RL. 18O-Isotope effect in 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. 4. Oxygen exchange of [1-13C, 18O2]acetic acid in dilute acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;102:4389–4392. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehm T, Huber R, Holak TA. Application of NMR in structural proteomics: screening for proteins amenable to structural analysis. Structure. 2002;10:1613–8. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00894-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wüthrich K. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. Wiley; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Benkovic SJ. Purification, characterization, and kinetic studies of a soluble Bacteroides fragilis metallo-beta-lactamase that provides multiple antibiotic resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22402–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neurath H. The proteins: composition, structure, and function. 2d. Vol. 5. Academic Press; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bond MD, Holmquist B, Vallee BL. Thioamide substrate probes of metalsubstrate interactions in carboxypeptidase A catalysis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1986;28:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(86)80074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sillén LG, Martell AE. Stability constants of metal-ion complexes. Supplement, Chemical Society; London: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sillén LG, Martell AE, Bjerrum J. Stability constants of metal-ion complexes. 2d. Chemical Society; London: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaiser ET, Kezdy FJ. Hydrolysis of Cyclic Esters. Prog. Bioorg. Chem. 1976;4:239–267. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huisgen R, Ott H. Die konfiguration der carbonestergruppe und die sondereigenschaften der lactone. Tetrahedron. 1959;6:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnston NJ, Mukhtar TA, Wright GD. Streptogramin antibiotics: mode of action and resistance. Curr. Drug Targets. 2002;3:335–44. doi: 10.2174/1389450023347678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tobias PS, Kezdy FJ. The alkaline hydrolysis of 5-nitrocoumaranone. A method for determining the intermediacy of carbanions in the hydrolysis of esters with labile [alpha] protons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:5171–5173. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruice TC, Holmquist B. The carbanion (E1cB) mechanism of ester hydrolysis. I. hydrolysis of malonate esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:2993–3002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore JA, Schwab JM. Unprecedented observation of lactone hydrolysis by the AAI2 mechanism. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:2331–2334. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong YH, Wang LH, Xu JL, Zhang HB, Zhang XF, Zhang LH. Quenching quorum-sensing-dependent bacterial infection by an N-acyl homoserine lactonase. Nature. 2001;411:813–7. doi: 10.1038/35081101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dragani B, Cocco R, Ridderstrom M, Stenberg G, Mannervik B, Aceto A. Unfolding and refolding of human glyoxalase II and its single-tryptophan mutants. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;291:481–90. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Periyannan G, Shaw PJ, Sigdel T, Crowder MW. In vivo folding of recombinant metallo-beta-lactamase L1 requires the presence of Zn(II) Protein Sci. 2004;13:2236–43. doi: 10.1110/ps.04742704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daiyasu H, Osaka K, Ishino Y, Toh H. Expansion of the zinc metallo-hydrolase family of the beta-lactamase fold. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagelueken G, Adams TM, Wiehlmann L, Widow U, Kolmar H, Tummler B, Heinz DW, Schubert WD. The crystal structure of SdsA1, an alkylsulfatase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, defines a third class of sulfatases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7631–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510501103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aubert SD, Li Y, Raushel FM. Mechanism for the hydrolysis of organophosphates by the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5707–15. doi: 10.1021/bi0497805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy BP, Pratt RF. A thiono-beta-lactam substrate for the beta-lactamase II of Bacillus cereus. Evidence for direct interaction between the essential metal ion and substrate. Biochem. J. 1989;258:765–8. doi: 10.1042/bj2580765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopreore C, Byers LD. The urease-catalyzed hydrolysis of thiourea and thioacetamide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;349:299–303. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bienvenue DL, Gilner D, Holz RC. Hydrolysis of thionopeptides by the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica: insight into substrate binding. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3712–9. doi: 10.1021/bi011752o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siegel H, McCormic DB. On the discriminating behavior of metal ions and ligands with regard to their biological significance. Acc. Chem. Res. 1970;3:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spencer J, Clarke AR, Walsh TR. Novel mechanism of hydrolysis of therapeutic beta-lactams by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia L1 metallo-beta-lactamase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33638–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.