Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD) is recognized as a systemic vasculitis affecting multi-organ with inflammatory changes. The commonest and most serious complication of KD is coronary artery aneurysm, but KD may cause other organic complications beside cardiac problems. Gastrointestinal tract also present complications of KD in which, for example, hepatic dysfunction, pancreatitis, intussusception, colonic obstruction, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, and bowel edema are included. Among them, colonal wall edema is left unknown in the incidence, and it has been reported even if rare. In this report, we describe a case of KD with colonal wall edema, occurred in 5-yr-old boy who complained of severe abdominal pain and vomiting.

Keywords: Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome, Gastrointestinal Complication

INTRODUCTION

Kawasaki disease (KD) was named as acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome or infantile polyarteritis, and first reported by Dr. Tomisaku Kawasaki in Japan in 1967 (1). The disease causes severe inflammation and necrosis of all blood vessels, in particular, invading medium-sized artery with a marked tendency affecting the coronary arteries. This vasculitis results in exudative change with infiltration of lymphocytes and large mononuclear cells into the media and adventitia of the vessels with endothelial necrosis (2). Moreover, these problems of vessels manifest not only in heart but also in many other systemic organs. Therefore, KD is a multi-systemic disease and unusual symptoms may be part of the systemic illness (3). Gastrointestinal involvement due to KD is not common, and its prevalence is 2.3% (4, 5).

The gastrointestinal symptoms have importance, because these throw into confusion to make a diagnosis of KD in case there are not enough characteristic diagnostic criteria for KD in acute febrile phase. We report a child - not diagnosed as KD on admission - who suffered from abdominal pain and showed improvement in all clinical manifestations including abdominal pain only after intravenous immunoglobulin was administered.

CASE REPORT

A 5-yr-old boy was admitted with a complaint of severe abdominal pain of three days' duration that had spontaneously occurred without a noticeable cause. At the time of admission, he had no other symptoms than abdominal pain and vomiting. His initial body temperature was checked at 38℃ with a slight fever that could be noticed until admission, with a pulse rate of 124 beats per minute and respiration at the rate of 30 per minute.

On physical examination, he appeared acutely ill, and skin rash, conjunctival injection and cervical lymphadenopathy were not seen. There was no specific lesion in the oral cavity or on the tongue. Neither erythema nor swelling on both extremities was found. His abdomen was soft and moderately distended with decreased bowel sound. Direct tenderness was so diffuse and severe, especially on the lower abdomen, that it was difficult to differentiate from the surgical abdomen. Rebound tenderness was obvious without muscle guarding. Hepatosplenomegaly or palpable abdominal mass was not detectable.

Initial laboratory examinations revealed white blood cell count of 13,790/µL with predominance of neutrophil 86.5%, red blood cell count of 4,390,000/µL, hemoglobin level of 12.4 g/dL, hematocrit of 35.6%, and platelet count of 229,000/µL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, urea, creatinine level and electrolytes were all within normal limits. Hematuria, pyuria and proteinura did not occur on a urine analysis. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated at 40 mm/hr (normal range, 0-10 mm/hr) and 15.85 mg/dL (normal range, 0-0.8 mg/dL), respectively. The result of blood culture was sterile. An abdominal radiograph showed distended bowel loop with fecal materials (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal radiograph reveals distended bowel loop with fecal materials.

He presented with atypically erythematous and maculopapular skin rash of irregular shapes and sizes just after admission. The rash predominantly involved the trunk, which was not improved with intravenous antihistamine. He continued to complain of abdominal pain with vomiting, without any improvement over two days.

Abdominal ultrasonography was performed to distinguish from acute appendicitis on day 2. It showed multiple variable lymph nodes in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. On day 3, he revealed erythema and swelling of the hands and feet, and strawberry tongue. Secondary follow-up laboratory findings on day 4 showed slightly more elevated ESR and CRP, 50 mm/hr and 19.46 mg/dL, respectively.

High spiking fever was prolonged remittently for five consecutive days and unresponsive to antibiotics. At this time, we came to make a presumed diagnosis of KD. Meanwhile, his abdominal pain was not improved at all. The abdomen was soft, but tenderness was still observed without rebound tenderness. We performed abdominal ultrasonography again, which showed bowel wall thickening (Fig. 2). Subsequent abdominal computed tomographic scan showed circumferential enhanced wall thickening and edema in the distal descending and sigmoid colon and normal rectum (Fig. 3). We noted that his lips changed red on day 6, and that bilateral conjunctivas were injected without exudate. A right cervical lymph node was enlarged with a size of greater than 1.5 cm in diameter on day 7. On the basis of these characteristic features that corresponded to the diagnostic clinical criteria, we confirmably made the diagnosis of KD. Therefore, we perceived that gastrointestinal complications might be closely related to a vasculitis by KD. We intended to perform colonoscopy, but it could not be done because of his parents' refusal. Echocardiography performed on day 8 revealed minimal pericardial effusion and mild tricuspid regurgitation, and no dilatation of coronary arteries.

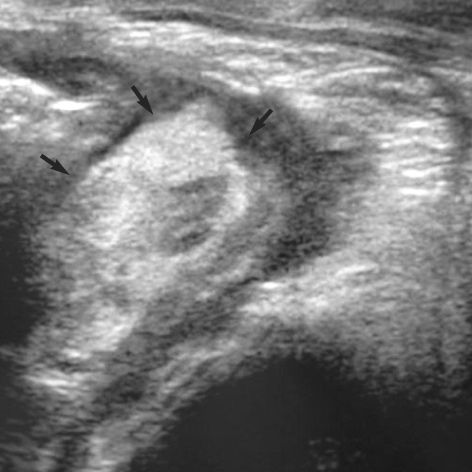

Fig. 2.

Transabdominal ultrasonograph shows circumferential bowel wall thickening (arrows) in the descending and sigmoid colon.

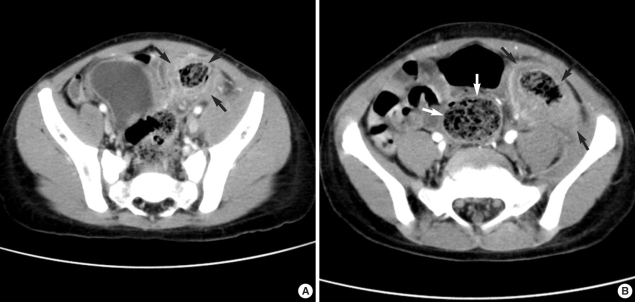

Fig. 3.

(A) Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT reveals circumferential bowel wall thickening with submucosal low attenuation in the lower distal descending colon (arrows). There are no abnormal enhanced lesion in pelvic solid organs and no ascites in the pelvic cavity. (B) Abdominal CT reveals circumferential bowel wall thickening in the sigmoid colon (black arrows), but normal thickness in the rectum (white arrows).

Abdominal pain and remittent fever persisted. He was treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin, 2 g/kg in a single infusion, together with 50 mg/kg per day of oral aspirin on day 8 after admission. Not only did his fever begin to subside, but abdominal pain also diminished dramatically the day after IVIG administration. On the third day after the treatment, laboratory findings showed a slightly more elevated platelet count, 507,000/µL and a remarkable fall of the CRP levels at 1.29 mg/dL. No infectious foci were found. A rapid resolution of all the clinical features was noted. On follow-up abdominal ultrasonogrphy performed on day 11, we found that bowel wall thickening was almost all decreased, and the hepatobiliary system was unremarkable. On day 12, he was discharged with reduced dosage of aspirin, 5 mg/kg per day as a single dose.

About four weeks after discharge, desquamation was noticed on the fingers and the perianal area, but the patient was clinically free of abdominal symptoms.

DISCUSSION

KD is a febrile systemic vasculitis of unknown cause usually affecting children younger than 5 yr of age. The etiology and pathophysiology of KD, despite numerous efforts to identify for 40 yr period, are still in a hypothetical stage. According to the consensus view, KD results from widely distributed infectious agents which evoke an abnormal immunological response in genetically susceptible individuals (6, 7). The results of recent immunologic, microbiologic and molecular studies show that superantigen-producing agents have been given attention with respect to the etiology of KD (4).

The diagnosis of KD can be made by fulfilling 5 characteristic diagnostic criteria (prolonged fever for at least 5 days together with four of a collection of five clinical features, including rash, non-purulent conjunctivitis, oropharyngeal changes, lymphadenopathy and change of the extremities) in the absence of any specific diagnostic tests. As approximately 20-25% of the untreated patients in KD have cardiac involvement, the delayed diagnosis could result in life-threatening problems particularly including cardiac sequelae. It demonstrates the importance of the early diagnosis of KD.

Among the clinical manifestations of KD, fever and skin rash are most common, while changes of the lips and oral cavity, cervical lymphadenopathy or bilateral conjunctivitis are less than the ones. Also, unusually, other manifestations such as irritability and vomiting are not observed. This was obtained from the result that Tizard et al. (8) studied 100 patients with KD through classification by symptoms. According to the study, irritability and vomiting were most common among other significant findings of KD. In addition, there are such as joint pain and tenderness, preceding upper respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, and hydrops of the gall bladder. There were 81 of 100 patients with KD who revealed various organic findings individually. Up to date, there have been consistently numerous reports showing that various complications arise in other organs as well.

Regarding complications of KD according to the system, the most common and life-threatening complication of KD, coronary artery aneurysm, occurs in about 25% of untreated patients which may lead to death by causing coronary thrombosis or myocardial infarction. There are also non-aneurysmal cardiac complications such as dilatation of coronary artery, pericardial effusion, pericarditis, myocarditis, and mitral incompetence.

We described a child who complained of severe abdominal pain on admission of which the cause was difficult to be explained until the sequential appearance of the clinical diagnostic manifestations of KD enabled us to make a definite diagnosis. Based on the diagnosis of KD, we performed abdominal evaluations and could ultimately clarify that the abdominal pain was associated with gastrointestinal complication of KD. Diarrhea or vomiting are the most common gastrointestinal findings in KD. Elevated liver enzyme levels and gall bladder hydrops are well-known findings, and splenic infarct, pancreatitis and ascites occur less frequently. Jejunal stricture and obstruction, intussusception, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, ischemic colitis, bowel edema, hemorrhagic enteritis, and so on have presented as complications related with the intestinal tract. These complications result from vasculitis and thrombosis of the small submucosal arteries involving the intestine. Submucosal hemorrhage has been also described as a causing factor of the complications through numerous cases.

Zulian et al. (9) reported that surgical abdominal complications were found in 12 patients with KD. Among them, gallbladder hydrops with cholestasis has been described in three cases, small intestinal occlusion in four, functional obstruction caused by paralytic ileus in three, ischemic colitis in one, and abdominal vasculitis with massive liver necrosis in one. In most of current reports, the diagnosis of KD was usually made 4 to 6 weeks after the onset of abdominal symptoms (10, 11). However, in this case, we could make the diagnosis of KD 10 days after the onset of abdominal pain. Compared with other previous reports, this is a case where the diagnostic signs of KD revealed a little earlier. KD complicated by colonic edema as this case has rarely been reported all over the world.

KD with colonic edema is explained in the view that KD is associated with inflammatory changes and vasculitis involving bowel vessels. More severe cases might produce nodular area or cause obstruction that could not help requiring surgical treatment. Descending and sigmoid colon were involved in this case, but there have been no studies or reports about the most common area where colonic wall edema occurs.

With respect to the relationship between abdominal symptoms and KD, as an interesting study, a hypothesis has been reported that the gastrointestinal tract could be one of the primary sites of entry of bacterial toxins in KD patients which affect immune system acting as superantigens. Therefore, we perceive the relationship between gastrointestinal symptoms and KD in that while KD give rise to complications in gastrointestinal tract, bacterial toxins affect the onset of KD by developing bacterial infection into gastrointestinal tract (12).

Furthermore, as in this case, some complications precede diagnostic clinical features in the acute phase, which might lead us to have a difficulty in making an earlier diagnosis. Since no diagnostic tests are available for KD, the diagnosis is absolutely based on clinical criteria. Although the numerous efforts to improve the early diagnosis have been made, KD remains a disease at risk to be underrecognized or misdiagnosed with other febrile illnesses.

We should recognize that the diagnosis and treatment of KD might be delayed if symptoms triggered by organic complications appear before the characteristic clinical features of KD.

References

- 1.Kawasaki T. Acute febrile mucocutaneous syndrome with lymphoid involvement with specific desquamation of the fingers and toes in children. Arerugi. 1967;16:178–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung CJ, Stein L. Kawasaki disease: a review. Radiology. 1998;208:25–33. doi: 10.1148/radiology.208.1.9646789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tizard EJ. Complication of Kawasaki disease. Current Paediatrics. 2005;15:62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaniv L, Jaffe M, Shaoul R. The surgical manifestations of the intestinal tract in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyake T, Kawamori J, Yoshida T, Nakano H, Kohno S, Ohba S. Small bowel pseudo-obstruction in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1987;17:383–386. doi: 10.1007/BF02396613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgner D, Harnden A. Kawasaki disease: What is the epidemiology telling us about the etiology? Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cimaz R, Falcini F. An update on Kawasaki disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:258–263. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(03)00032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tizard EJ, Suzuki A, Levin M, Dillon MJ. Clinical aspects of 100 patients with Kawasaki disease. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:185–188. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zulian F, Falcini F, Zancan L, Martini G, Secchieri S, Luzzatto C, Zacchello F. Acute surgical abdomen as presenting manifestation of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2003;142:731–735. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy DJ, Jr, Morrow WR, Harberg FJ, Hawkins EP. Small bowel obstruction as a complication of Kawasaki disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1987;26:193–196. doi: 10.1177/000992288702600410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan ST, Lau WY, Wong KK. Ischemic colitis in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:964–965. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(86)80107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashiro Y, Nagata S, Ohtsuka Y, Oguchi S, Shimizu T. Microbiologic studies on the small intestine in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:622–624. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]