Abstract

We describe a 37-yr-old man who developed central pontine myelinolysis (CPM) after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. After HSCT, desquamation developed on the whole body accompanied by hyperbilirubinemia. The liver biopsy of the patient indicated graft-versus-host disease-related liver disease, and the dose of methylprednisolone was increased. Then, the patient developed altered mentality with eye ball deviation to the left, for which electroencephalogram and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were done. Brain MRI scan demonstrated the imaging findings consistent with central pontine myelinolysis and extrapontine myelinolysis. He did not have any hyponatremia episode during hospitalization prior to the MRI scan. To the best of our knowledge, presentation of CPM after allogeneic HSCT is extremely rare in cases where patients have not exhibited any episodes of significant hyponatremia. We report a rare case in which hepatic dysfunction due to graft-versus-host disease has a strong association with CPM after HSCT.

Keywords: Myelinolysis, Central Pontine; Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation; Graft versus Host Disease

INTRODUCTION

Central pontine myelinolysis (CPM) is an acute, non-inflammatory demyelinating disease of the pons of the central nervous system (CNS) (1). The etiology and the pathogenesis of CPM remain unclear, but too-rapid correction of hyponatremia is often associated with CPM, which is the result of the selective loss of myelin. Other risk factors identified include alcoholism, malnutrition, liver disease, and interestingly, liver transplant (2, 3). Only one prior case report of subjects associated with CPM and hepatic veno-occlusive disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been published (4).

We describe a rare case who developed CPM after allogeneic HSCT for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

CASE REPORT

A 37-yr-old man was admitted to our hospital for HSCT. He was diagnosed with ALL, presenting with mild fever, fatigue, and headache. A bone marrow examination showed acute precursor B cell leukemia with morphology consistent with FAB L2 subtype. Cytogenetic study demonstrated a clonal abnormality with translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22. BCR/ABL rearrangement was positive by fluorescence in situ hybridization (78.5%). The patient received initial induction chemotherapy, which was composed of vincristine 2 mg on days 1 and 8, daunorubicin 90 mg/m2/day on days 1-3, prednisolone 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-14, and imatinib 600 mg once daily from day 8 with intrathecal methotrexate. He achieved morphological remission. Since an HLA-matched sibling donor was available, allogeneic HSCT was performed with the matched sibling donor.

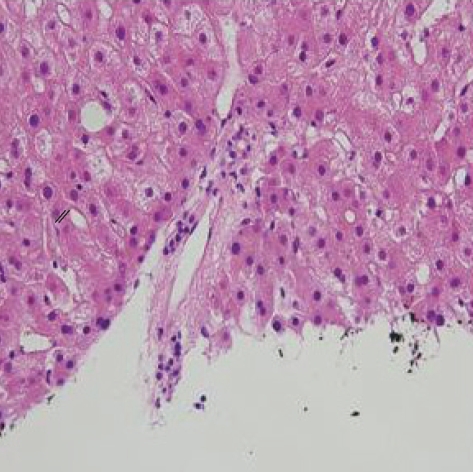

Following a conditioning regimen of busulfan 0.8 mg/kg/dose four times daily on days -8, -7, -6, -5 and cytoxan 60 mg/kg/day on days -3, -2, the patient received 9.23×108 nucleated cells/kg (10.4×106 CD34 cells/kg) from his brother. For prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), cyclosporine and prednisolone were used. He tolerated this conditioning therapy well, and the post-transplant course was unremarkable until the 12th day. The patient showed altered mentality on the 13th day, and his serum cyclosporine level was increased higher than 1,300 ng/mL (normal range, 150-300 ng/mL). As his altered mentality was attributed to cyclosporine-induced agitation and psychosis, we stopped administering cyclosporine and replaced cyclosporine with methylprednisolone. Thereafter, the patient showed much improvement in consciousness. On the 25th day, the patient developed desquamation at whole body and hyperbilirubinemia with a peak bilirubin level of 29 mg/dL. To rule out the possibility of veno-occlussive disease (VOD), doppler ultrasonography was conducted, which revealed no evidence of VOD. Then, transjugular liver biopsy was done. Liver biopsy revealed vacuolated cytoplasm and hyperchromasia of the bile duct epithelium, which was compatible with GVHD (Fig. 1). Therefore, we conducted high-dose steroid pulse therapy for 6 days and maintained methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day since then.

Fig. 1.

Needle biopsy of the liver. The GVHD here is affecting the liver and marked by bile duct damage (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×400).

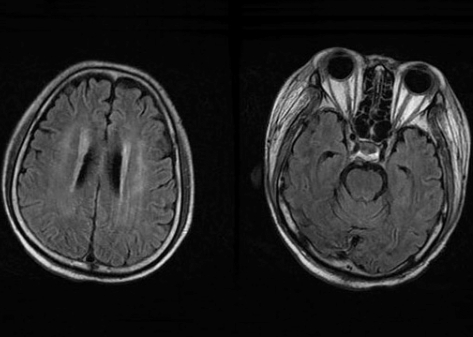

On the 48th day, the patient demonstrated drowsy consciousness with Glasglow Coma Scale E4M1V1 and left eyeball deviation. We conducted cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tapping and a brain MRI scan. CSF cytology was negative for malignant cells, and the brain MRI scan showed multiple white matter low densities (Fig. 2), which meant a nonspecific result with respect to his neurologic problem.

Fig. 2.

Brain MRI reveals nonspecific findings including multiple white matter low densities.

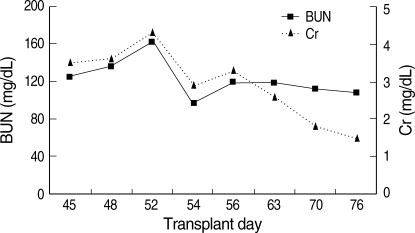

At that time, the patient had a decreased urine output and increased serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/Creatinine (Cr) level. The ranges of serum BUN (normal range, 10-26 mg/dL) and Cr level (normal range, 0.7-1.4 mg/dL) were 125-165 mg/dL, 2.3-4.3 mg/dL respectively. To rule out the possibility of uremic encephalopathy, he received hemodialysis three times per week from the 53th day. Thereafter, the BUN and Cr level were maintained around 96-120 mg/dL, 1.5-3.3 mg/dL respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Serial changes of BUN and Cr.

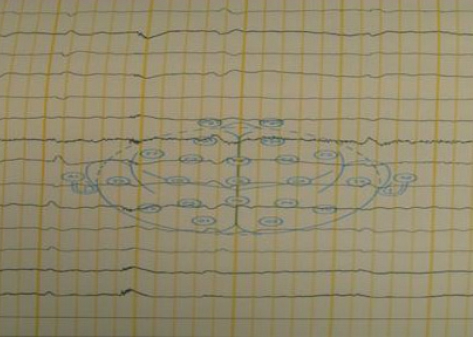

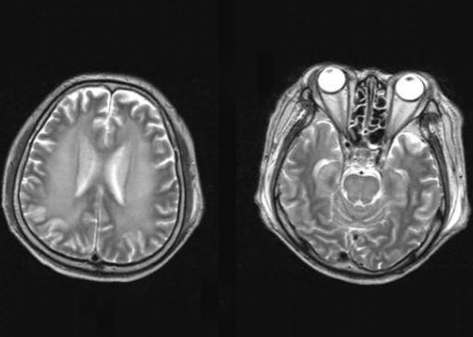

During these treatments, the patient's consciousness was unchanged, so we followed up with CSF tapping, electroencephalogram, and a brain MRI scan on the 70th day. CSF cytology was negative, and the electroencephalogram finding showed low amplitude theta slowings at all leads, which meant diffuse cerebral dysfunction (Fig. 4). The follow-up brain MRI revealed diffuse marked progression of confluent white matter T2 high-signal lesions in periventricular white matter, basal ganglia, pons, and cerebellum, which was consistent with CPM and extrapontine demyelinolysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Low amplitude theta slowings at all leads on electroencephalogram indicate diffuse cerebral dysfunction.

Fig. 5.

Follow-up Brain MRI showed diffuse marked progression of confluent white matter T2 high-signal lesion in both periventricular white matter, basal ganglia, pons, and cerebellum, consistent with CPM.

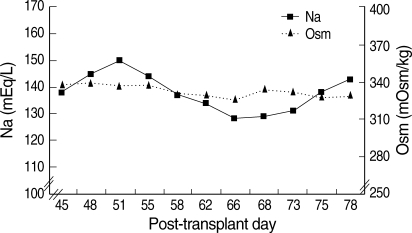

A review of serial serum sodium levels revealed that though serum sodium measurements (normal range, 135-145 mEq/L) had fluctuated between 128-150 mEq/L during 20 days of hospitalization prior to follow-up MRI scan, there was no episode of correcting hyponatremia in our patient.

On the 48th day, the serum sodium level was 145 mEq/L and daily variations of serum sodium level were within the range of 3-7 mEq/L/day since then. Also, the range of serum osmolarity (normal range, 289-302 mOsm/kg) was 328-339 mOsm/L (Fig. 6). During the same period, cyclosporine as another risk factor was not used any longer since the 14th day.

Fig. 6.

Serial changes of sodium (Na) and osmolarity (Osm).

The patient was given plasmapheresis three times per week and steroid therapy as the experimental treatment of CPM, but its effectiveness was insignificant. He died of bilateral intraventricular hemorrhage on the 78th day.

DISCUSSION

CPM is a clinical syndrome including disturbances of consciousness, disturbed function of caudal cranial nerves with signs of pseudobulbar palsy, dysarthria as well as spastic paraparesis and tetraparesis of various degrees of severity, epileptic seizures, and hypotension (5-7).

A clinical diagnosis of CPM can be made, if patients suffering from chronic alcoholism, electrolyte disturbance, or other chronic diseases as well as liver transplant patients presenting with massive mental changes show specific neuroradiological findings on MRI scan (2). There is no treatment of choice in CPM.

CPM has been known to result from the rapid correction of hyponatremia and merge as a well-recognized neurological complication following hepatic dysfunction such as chronic liver disease and liver transplant (6, 8). In one series of postmortem examinations of liver transplant patients, a 29% incidence of CPM was reported (9). It has been revealed that the use of cyclosporine following liver transplant increases the risk of development of CPM (10).

Neurological deterioration was a prominent feature of our patient's post-transplant course. In such a critically ill patient, it is likely that several factors contributed to his encephalopathy, including liver dysfunction, uremia, cyclosporine, and CPM.

Other causes of encephalopathy in the setting of HSCT include electrolyte disturbances, cerebrovascular events or infection, and sedative drugs; but laboratory parameters and imaging findings did not support a role for these possibilities in this case.

Despite the likely multifactorial etiology of the encephalopathy, the clinical signs of left eyeball deviation and the loss of consciousness in conjunction with suggestive neuroimaging are best explained by the diagnosis of CPM.

To the best of our knowledge, presentation of CPM after allogeneic HSCT is extremely rare in cases where patients have not exhibited any episodes of significant hyponatremia. Only one case was reported that severe hepatic VOD and cyclosporine therapy after HSCT induced the development of CPM without any episodes of significant hyponatremia (4).

Given the known association with liver disease as the cause of CPM, we concluded that our patient's severe hepatic dysfunction due to GVHD might have predisposed him to the development of CPM.

References

- 1.Messert B, Orrison WW, Hawkins MJ, Quaglieri CE. Central pontine myelinolysis. Considerations on etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurology. 1979;29:147–160. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lampl C, Yazdi K. Central pontine myelinolysis. Eur Neurol. 2002;47:3–10. doi: 10.1159/000047939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashrafian H, Davey P. A review of the causes of central pontine myelinolysis: yet another apoptotic illness? Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:103–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser C, Charnas L, Orchard P. Central pontine myelinolysis following bone marrow transplantation complicated by severe hepatic veno-occlusive disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:733–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormick WF, Danneel CM. Central pontine myelinolysis. Arch Intern Med. 1967;119:444–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karp BI, Laureno R. Pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a neurologic disorder following rapid correction of hyponatremia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1993;72:359–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterns RH, Cappuccio JD, Silver SM, Cohen EP. Neurologic sequelae after treatment of severe hyponatremia: a multicenter perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;4:1522–1530. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V481522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bronster DJ, Emre S, Boccagni P, Sheiner PA, Schwartz ME, Miller CM. Central nervous system complications in liver transplant recipients-incidence, timing, and long-term follow-up. Clin Transplant. 2000;14:1–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2000.140101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh N, Yu VL, Gayowski T. Central nervous system lesions in adult liver transplant recipients: clinical review with implications for management. Medicine (Baltimore) 1994;73:110–118. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199403000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fryer JP, Fortier MV, Metrakos P, Verran DJ, Asfar SK, Pelz DM, Wall WJ, Grant DR, Ghent CN. Central pontine myelinolysis and cyclosporine neurotoxicity following liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61:658–661. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199602270-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]