Abstract

This study reports on an effort to evaluate and interrelate the existence and strength of two core laws and fourteen expanded laws designed to (a) control the sales of alcohol, (b) prevent possession and consumption of alcohol, and (c) prevent alcohol impaired driving by youth aged 20 and younger. Our first analysis determined if the enactment of the possession and purchase laws (the two core minimum legal drinking age laws) was associated with a reduction in the ratio of drinking to nondrinking drivers aged 20 and younger who were involved in fatal crashes controlling for as many variables as possible. The ANOVA results suggest that in the presence of numerous covariates, the possession and purchase laws account for an 11.2% (p = 0.041) reduction in the ratio measure. Our second analysis determined whether the existence and strength of any of the 16 underage drinking laws was associated with a reduction in the percentage of drivers aged 20 and younger involved in fatal crashes who were drinking. In the regression analyses, making it illegal to use a false identification to purchase alcohol was significant. From state to state, a unit difference (increase) in the strength of the False ID Use law was associated with a 7.3% smaller outcome measure (p = .034).

Keywords: Minimum legal drinking age laws, underage drinking drivers, fatal crashes, possession and purchase laws, alcohol policy information system, fatality analysis reporting system

1. INTRODUCTION

To reduce youth drinking and alcohol-related problems, the federal government passed legislation in 1984 that provided for a uniform minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) of 21 throughout the United States. Threatened by the loss of federal highway funds, by 1988, every state that had a lower MLDA had raised its minimum legal age for both the purchase and possession of alcohol to 21. Additionally, all the states and the District of Columbia have passed laws prohibiting the furnishing or selling of alcohol to those younger than age 21, many at the same time as the two “core MLDA laws.” These two core MLDA laws (prohibiting possession and purchase of alcohol by youth) have been studied extensively and considerable evidence exists that such laws can influence underage alcohol-related traffic fatalities (O’Malley and Wagenaar, 1991; Ponicki et al., 2007; Shults et al., 2001; Voas et al., 2003). From 1988 to 1995, alcohol-related traffic fatalities for youth aged 15 to 20 declined from 4,187 to 2,212, a 47% decrease, with wide variability in these declines between states (National Center for Statistics and Analysis [NCSA], 2003).

To support the two core MLDA laws and further enhance their underage alcohol prevention programs, states have enacted other legislation targeting retail and social access to alcohol by youth and the prevention of impaired driving by underage youth. For example, laws addressing keg registration, the use of fake identification, and minimum server/seller age all seek to make it more difficult for youth to obtain alcohol from retail sources. Other laws such as zero tolerance (ZT), which makes it an offense for drivers aged 20 and younger to operate a vehicle with any amount of alcohol in their system (blood alcohol concentration [BAC] > .00), focus on preventing youth from drinking and driving. Some provisions of recent graduated driver licensing (GDL) laws have night restrictions on driving by youth in order to reduce the risk of drinking and driving, most of which occurs at night. Use and lose laws, which authorize the suspension of driving privileges for underage alcohol violations (i.e., purchase, possession, or consumption of alcohol) aim to provide meaningful sanctions for youth who violate the MLDA laws. Social host laws target those who host underage drinking parties. All of these ancillary laws (hereafter referred to as “expanded MLDA laws”) were designed to strengthen the earlier core MLDA 21 laws (prohibiting possession and purchase) and increase states’ alcohol prevention efforts targeting youth.

Despite the promise of such laws, however, considerable public ambivalence has resulted in substantial variation between states in the comprehensiveness of such legislation. For example, although all states make it unlawful for an underage person to possess alcohol, it is not illegal in some states for an underage person to consume alcohol. Further, some states have ZT laws that are unenforceable because police officers cannot take a youth into custody or transport them to the police station for a breath test unless they can demonstrate that the youth has a BAC higher than the adult illegal limit of .08 BAC (Ferguson et al., 2000). Not all states have graduated driver licensing (GDL) laws and some states do not have provisions in them restricting unsupervised driving at night when alcohol is most likely to be a factor (Williams and Preusser, 1997).

This study has two primary objectives: (1) to verify the value of the core MLDA laws in reducing alcohol-related fatal crashes among underage drivers with a methodology that improves upon previous studies by controlling for as many factors as possible (including safety belt usage laws) that could affect underage drinking and driving, and (2) to investigate the existence and strength of the 2 core and 14 expanded MLDA laws simultaneously and determine whether any specific laws emerge as uniquely effective in reducing underage traffic fatalities.

2. METHODS

2.1 Data Sources

The primary source of data for underage drinking laws in the states is the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) dataset (1998-2005) (NIAAA, 2005). APIS provides information on 15 of the 16 laws examined in this study. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA, 2006) Digest of Impaired Driving and Selected Beverage Control Laws was also used to obtain information on the license sanctions for violating ZT laws. For the final law, GDL, information from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS, 2006) was used.

The outcome data—drinking driver and nondrinking driver fatal traffic crashes—were obtained from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) maintained by NHTSA. The FARS is a census of all police-reported motor vehicle crashes on public roadways that result in the death of at least one road user (e.g., vehicle occupant or nonmotorist such as a pedestrian or bicyclist) within 30 days of the crash. The database contains considerable detail about roadways, vehicles, road users, weather, time of day, and other factors about each fatal crash. Alcohol involvement is documented through BAC test results collected by police or coroners. Where such data are not available, the BACs of drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists are statistically imputed using crash characteristics (such as a police report of driver impairment) to obtain more complete and accurate alcohol data (Subramanian, 2002).

2.2 Coding of the Two Core and Fourteen Expanded MLDA Laws

The public generally assumes that the MDLA 21 is embodied in a single law and, therefore, all states have essentially the same law. In actuality, the MLDA 21 has multiple components targeting outlets that sell alcohol to minors; adults who provide alcoholic beverages to minors; and underage persons who purchase or attempt to purchase, possess, or consume alcohol. In addition, there are companion laws that provide for lower BAC limits for underage drivers, GDL, and other legislation such as keg registration and social host liability laws (see Table 1). These laws vary considerably from state to state, and no state has all of the 16 law components or regulations that were documented. Thus, the current U.S. effort to control underage drinking involves a variable package of legislative policies.

Table 1.

Status of 16 Key Underage Drinking Laws in the United States - January 2007

| (1) Possession (APIS) |

(2) Consumption ((APIS) |

(3) Purchase ((APIS) |

(4) Furnishing/Selling ((APIS) |

(5) Age 21 for on-premises servers/sellers ((APIS) |

(6) Age 21 for off-premises servers/sellers ((APIS) |

(7) Zero tolerance ((APIS) |

(8) Use and lose ((APIS) |

(9) Keg registration ((APIS) |

(10) RBS training ((ABC) |

(11) Use of Fake ID ((APIS) |

(12) Transfer/production of Fake ID ((APIS) |

(13) Retailer support provisions for Fake ID ((APIS) |

(14) Social host-underage parties ((APIS) |

(15) GDL with night restrictions ((IIHS, CC) |

(16) State control of alcohol ((PIRE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| AK | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AZ | 8 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| AR | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CA | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| CO | 4 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| CT | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| DE | 5 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| DC | 7 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| FL | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| GA | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| HI | 4 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| ID | 5 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| IL | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| IN | 7 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| IA | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| KS | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| KY | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LA | 3 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| ME | 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| MD | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| MA | 7 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| MI | 7 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| MN | 5 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MS | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| MO | 8 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| MT | 7 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| NE | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| NV | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| NH | 8 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| NJ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| NM | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| NY | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| NC | 7 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| ND | 7 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OH | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| OK | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| OR | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| PA | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| RI | 7 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| SC | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| SD | 8 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| TN | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| TX | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| UT | 8 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| VT | 8 | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| VA | 8 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| WA | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| WV | 7 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| WI | 7 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| WY | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total # | ||||||||||||||||

| w/law | 51 | 30 | 47 | 51 | 24 | 24 | 51 | 37 | 26 | 33 | 51 | 25 | 46 | 18 | 44 | 18 |

To assess the relative strength among states for each of the 2 core and 14 expanded MLDA laws, a scoring system was developed to assign points for provisions of laws that should deter young people from using alcohol and to deduct points (i.e., reduce scores) for provisions that increase the likelihood of underage alcohol use or that make law enforcement more difficult. These assessments of the core and expanded laws were based on empirical evidence, where it exists, and/or reasoned theoretical arguments. The scoring system was also reviewed by legal and traffic safety experts. Provisions such as family member and location exceptions, the type and severity of sanctions for violations, and applicability of the law across situations or substances (e.g., beer, wine, and distilled spirits) were among the variables coded. In all cases, the scoring was designed so that a value of zero corresponds with a state not having a law and higher values represent stronger laws. Such a scoring scheme is similar to that developed by the IIHS in its assessment of key components of GDL (IIHS, 2007). Because each law differs in the number of provisions assessed (and possible point additions or deductions), the base scores and total scores that are possible vary across the 16 laws. Thus, the maximum possible number of points for a law does not imply relative importance of that law compared to the other laws. Each law’s point scale is independent, and the magnitudes of scores are not comparable between laws. These differences between laws in range and absolute value of their scores, however, do not affect the statistical analyses (i.e., do not make one law inherently more likely to predict the outcome measure). This is the case because the analyses examine whether each law’s distribution of scores correlates with the variation in underage drivers in fatal traffic crashes. The detailed coding scheme for each of the 16 laws in presented in Appendix A.

In summary, Table 1 provides each state’s scores for each law. Aside from issues relating to the level of enforcement and the publicity given to underage laws, there is substantial variation in the comprehensiveness and the strength of adopted MLDA laws.

2.3 Analyses for the Core MLDA Laws

The aim of the first analysis was to determine if the enactment of the possession and purchase laws (the two core MLDA laws) was associated with a reduction in the ratio of drinking to nondrinking drivers younger than 21 years old who were involved in fatal crashes controlling for as many variables as possible that could affect the outcome. Annual FARS data from 1982 to 1990 were used in this analysis because: (a) imputed BAC data are available only from 1982 and later in FARS; (b) most states adopted their age 21 possession and purchase laws between 1982 and 1988; and (c) a wave of impaired driving laws were introduced after 1990 (e.g., ZT laws for youth, .08 BAC limits for adults, primary safety belt laws) and would be confounded with the effects of possession and purchase laws if the analyses were extended beyond 1990. The ratio of drinking to nondrinking drivers in fatal crashes has been shown in previous studies to be a good outcome measure that takes into account exposure to a fatal crash. Introduced and applied to the evaluation of other alcohol traffic safety laws (Tippetts et al., 2005; Voas et al., 2000; 2003; 2007), this crash incidence ratio has been shown to be similar to the quasi-induced exposure technique known as the relative accident involvement ratio.

An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used with the outcome variable, the annual ratio of drinking to nondrinking drivers younger than 21 in fatal crashes in each state. Because the possession and purchase laws were implemented on the same date in each state, only one intervention variable was created to represent both laws, with values from zero to one: zero for the absence of the laws, one for the presence, and a decimal representing the portion of the year during which the law was present. Geographical and socio-economic data available for the analyses were “state,” “region,” annual state unemployment rates, annual state vehicular miles traveled per capita (VMT), annual percent of the state population living in an urban area (urbanization) and the annual state percentage of alcohol-positive drivers older than 25 years involved in fatal crashes. All of these factors have been shown to be important in analyses of this type (O’Neill and Kyrychenko, 2006; Voas et al., 2003). Although the majority of states enacted a series of impaired driving and other traffic safety laws—administrative license revocation (ALR), .10 per se, .08 per se, and primary and secondary safety belt enforcement—in the 1990s and later, some states adopted these laws earlier. To account for the effects of these other laws, we coded their enactment dates for each state. No state had implemented true ZT laws by the end of 1989. Using the implementation dates for the above laws, variables indicating the absence or presence of each of these laws in each state for each year were created. In addition, as with the possession and purchase laws, decimals were used to represent the portion of the implementation year during which the laws were in effect. These laws were all used as covariates in the models.

A categorical factor for “region” was included in the analyses because the available socio-economic variables were not adequate to explain all of the between-state variation in the outcome variable. “Region” represented the ten geographic divisions of the country (e.g., New England, Mid-Atlantic, Southeast) corresponding to the Regions that NHTSA uses. Economic conditions correlating with traffic risk and exposure have been shown to vary by region. The NHTSA Regions were included in the models as a way to control for unmeasured external factors that vary between states in a consistent manner. Panel-style models such as this would typically use “state” as a main effect to partial out all this between-state variance, but doing so uses 50 parameters or degrees of freedom (many of which would be nonsignificant individually). With so few data points available, using such a “state” factor risks overfitting the model. Because many of these unknown external factors that affect the outcomes are likely related to economic, demographic, and other environmental factors that cause these state-to-state differences to be similar within geographic region, tests were conducted to see if a “region” could account for much of this between-state “error” variance in a more parsimonious way, i.e., sacrificing far fewer degrees of freedom than a “state” factor. As “region” was associated with greater statistical efficiency, it was used for these analyses instead of “state.” (Incidentally, the “region” model also produced a more conservative estimate of the law effects than did the “state” model.)

“Year” was not used as a factor in the models as the presence or absence of the law is a linear function of “Year” and could produce colinearity problems. Finally, total per capita beer consumption (no separate figure for underage drinkers was available) was used as a covariate in the models because past studies have shown that this is significant in predicting alcohol involvement in fatal crashes (Voas et al., 2000; 2003).

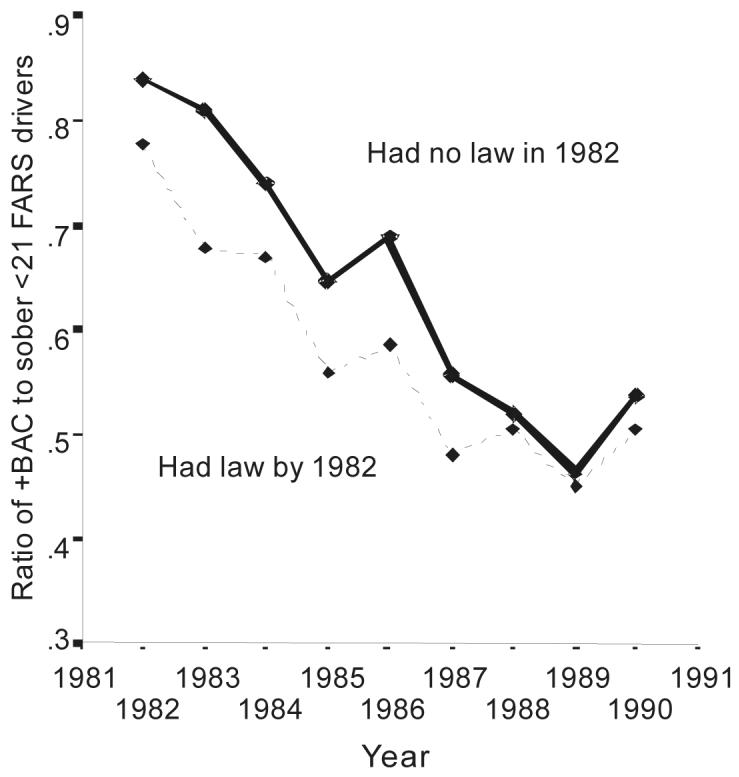

There were 14 states that had implemented minimum age 21 possession and purchasing laws prior to 1982. Because these states did not change law status during the years studied, they functioned as comparison states, and their alcohol involvement rates were used as a covariate in the model. As the 14 states that already had MLDA 21 were distributed throughout 8 of the 10 regions of the country that were used in the analyses, it was possible to pool the annual number of drinking and nondrinking crashes for those comparison states within the same region to compute an annual regional comparison ratio of drinking to nondrinking drivers younger than 21. For these comparison states, the variation in the number of fatal crashes was less within regions than between regions. Therefore, the “region comparisons” model was considered a better alternative to using a single national comparison ratio of all 14 states that implemented the MLDA 21 core laws before 1982. However, because there were no comparison states in Region 1 (the New England states) and Region 2 (New York and New Jersey) with the possession and purchase laws implemented by 1982, the comparison states’ ratio for Region 3 (Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia) was also used as the comparison for both Regions 1 and 2. Plots of the ratios for the states with and without MLDA 21 laws prior to 1982 are shown in Figure 1. Note the convergence of the ratio in years 1988-1990 when all 50 states and DC had the MLDA 21 core laws.

Figure 1.

Ratio of drinking (alcohol-positive) to nondrinking (alcohol-negative) younger than age 21 drivers from FARS for states that had enacted the possession and purchase laws by 1982 and states that had not.

2.4 Analyses for Existence and Strength of Core and Expanded MLDA Laws

The aim of the second analysis was to determine if the existence and strength of any of the 16 underage drinking laws was associated with a reduction in the percent of drivers younger than 21 years old involved in fatal crashes who were drinking. Using pooled data from the 1998-2004 Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), the total numbers of alcohol-positive and alcohol-negative drivers were used to compute the percentages of drivers from three age groups (younger than 21, 21-25, 26+) who were drinking. The predictors in the Stepwise Linear Regression models were the percentages of alcohol-positive drivers aged 21 to 25 years and aged 26 and older and the 16 laws, the existence and strengths of which were coded separately for each state (a cross-sectional between-state design).

Before the second analysis was undertaken, a Factor Analysis was used to determine if any of the laws “clustered” or were grouped together. To extract any factors, Principal Component Factoring (PCF) was used with both Quartimax rotation and Varimax rotation methods. Six factors emerged, but three of them explained little more than one variable. Generally, the eigenvalues were all quite low. Because some of the laws we examined (e.g. ZT, possession and purchase) were already shown to be strong predictors of our outcome, we decided not to combine any of them. See Appendix B for the results of the factor analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Core MLDA laws

The ANOVA results pertaining to the effect of the enactment of the possession and purchase core MLDA 21 laws in 36 states plus DC between 1982 and 1990 are shown in Table 2. The significant predictors are the possession and purchase laws, the .08 law, the ALR law, the younger-than-21 ratios in the comparison states, “urbanization,” unemployment rates, per capita VMT, and “region.” These results suggest that in the presence of the aforementioned covariates, the implementation of the possession and purchase laws was associated with an 11.2% (p = 0.041) reduction in the ratio of alcohol-positive to alcohol-negative younger than age 21 drivers involved in fatal crashes.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for the natural log of the ratio of drinking to nondrinking drivers younger than age 21 in fatal crashes. In this model, “region” and data from the 14 states that had the possession/purchase laws in place in 1982 serve as a covariate (R2 = 0.49)

| Parameter | B | SE (B) | Effect Sizea (%) | P-Value | 95% CI for B | Variance explained (partial Eta2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Possession & Purchasing Laws | -0.12 | 0.06 | -11.2 | 0.041 | -0.23 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| .08 Law | -0.80 | 0.24 | -55.1 | 0.001 | -1.27 | -0.33 | 0.03 |

| ALR Law | -0.26 | 0.05 | -22.6 | <0.001 | -0.35 | -0.17 | 0.09 |

| Under 21 ratio in comparison States (in log transformed metric) | 0.46 | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.68 | 0.05 | |

| % Urbanization | -0.32 | 0.15 | 0.038 | -0.62 | -0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Unemployment | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.022 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| VMT per licensed driver | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.048 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |

| Categorical Factors | F-statistic | df | P-Value | partial Eta2 | |||

| Region (Region 10 = Ref cat ) | 16.68 | 9 | <0.001 | 0.32 | |||

Effect size is the percentage change in the outcome variable’s metric, per unit change in the predictor variable. For binary variables representing presence/absence of a law, it can be interpreted as the proportional amount of change in the outcome associated with the presence of a law.

The effect size found for the .08 law here should be viewed with caution. The estimate is based on the four earliest states to implement the law—Oregon Utah, Maine, and California—and for each of these states there were very few pre- or post-law data points from which to estimate the change. This parameter for the .08 law effect is likely biased and is neither representative of the entire breadth of .08 states, nor the longer-range experience of these four states (see Tippetts et al., 2005; Voas et al., 2000). The effect size of the ALR law may have also suffered from the same limitations as the .08 BAC law. Most of the studies of the effects of ALR have shown smaller effect sizes because more years were taken into account (Voas et al., 2000; Wagenaar, 2007).

An alternative model (not shown here) that includes a covariate for the older-aged driver cohorts within the same states as a comparison produces similar results (unemployment and VMT were no longer significant, as the within-state cohort likely explained much of the same variance these covariates had). Although that alternative model explains a slightly greater proportion of total variance (R2= .55), it is also likely to dampen the parameter estimates for any law implementation that should impact both youth and adult drivers, such as ALR and .08. With the inclusion of the older cohort, the effect size of the two core MLDA 21 laws (possession and purchase) is slightly less at 9.1%, but still significant (p=.047).

3.2 Existence and Strength of 16 Core and Expanded MLDA laws

In the regression analyses used to examine the effect of the existence and strength of the 2 core and 14 expanded MLDA 21 laws, only the percentages of drivers in the older age groups who were drinking and “False ID Use” were significant (Table 3). Specifically, from state to state, a unit difference (increase) in the strength of the False ID Use law was associated with a 7.3% smaller outcome measure (p = .034). The difference between the weakest (no license sanction) and strongest (administrative license sanction) False ID Use laws (two units on our scoring scale) represents a 14.1% difference. Excluding the two older cohorts increases the effect size of False ID Use slightly, but the other laws remained nonsignificant.

Table 3.

Final model for percentage of younger-than-age-21 drivers involved in fatal crashes who had a positive BAC with the two older driver age groups and the 16 MLDA 21 laws included as covariates

| Parameter | B | Effect size (% change) | SE | P-value | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | -0.484 | 0.440 | .276 | ||

| Natural log of % of 26+ with + BAC | 0.689 | 0.156 | .000 | .508 | |

| Natural log of % of 21-25 with + BAC | 0.437 | 0.158 | .008 | .496 | |

| False ID - Use | -0.076 | -7.32 | 0.035 | .034 | .966 |

Dependent variable: Log of the percentage of younger-than-age-21 drivers with + BAC. R2 = 0.68

4. DISCUSSION

The finding that the core possession and purchase laws were associated with a significant reduction in the ratio of drinking to nondrinking underage drivers in fatal crashes is consistent with previous research even though substantially different methods were used. The 11% reduction may be considered conservative compared to findings from other studies (Arnold, 1985; Hedlund et al., 2001; O’Malley and Wagenaar, 1991; Shults et al., 2001; Toomey et al., 1996; Voas et al., 2003; Womble, 1989). In this study, more factors were accounted for as covariates (including regional variation); the period selected was unique; and the comparison to 14 states that already had MLDA 21—with contrasts stratified within region—was unique and might serve to dampen the effect found by others. Our earlier study (Voas et al., 2003) which suggested a 19% decrease, had used many of the same covariates as this study, but without the explicit contrast of comparison states within region, or the regional stratification to account for the ‘panel’ effect of cross-sectional correlated error within regions. Our earlier study had also examined a longer time period that overlapped with the wave of ZT laws being implemented in the 1990s, which we excluded in this study. Another likely explanation for the more conservative effect size found here is that any within-state temporal correlation of errors was not fully accounted for using time series style parameters. We expect that doing so would result in smaller error variance, and likely greater sensitivity to detecting the laws’ effects.

In the second analyses, only 1 of the 16 laws examined showed an association with reductions in underage drinking drivers in fatal crashes. While this appears surprising, there were various methodological limitations that made detection of an impact difficult. Perhaps the way the “strengths” of the laws were coded had something to do with this. Although the coding was guided by extant empirical evidence, theory, and consultation with traffic safety and legal experts, such assessments of key legal provisions are not simple or straightforward. This is relatively new territory in the analyses of underage drinking policies. Although some similar attempts have been undertaken such as by IIHS to quantify the components of GDL laws by using a point system, few precedents exist. Secondly, because APIS did not document the implementation dates for most of the expanded MLDA laws, it was impossible to incorporate a pre-post element. To provide the most reliable rates (due to relatively small youth crashes for many smaller states), the multiple years of data within each state were pooled into a single data point per state. This resulted in a sample N of only 51 cases for this analysis. Thus, a cross-sectional between-state design had to be used. This essentially “static” design, in which all test relationships are between-state, greatly reduces the sensitivity to detect effects of laws. In addition, small sample size likely influenced the results (or lack thereof). Also, the 16 laws were tested in the model simultaneously, and with the amount of overlap (or cross-correlation) among the laws, finding an incremental or differential effect for additional variables would be very difficult once the most significant law has been modeled. Finally, it should be noted that our outcome variable, drivers in fatal crashes, only represents the most severe types of crashes that these laws were designed to impact. If moderate or lower risk youth drivers are being prevented from drinking and driving, it may not be discernable within the most serious crashes (fatalities) whereas it might be detectable within the much larger pool of nonfatal crashes (injury and property damage).

The 16 laws examined here were adopted generally to reduce youth access to alcohol and related problems. Thus, our analyses sought to assess the full complement of relevant laws to determine overall which laws are most strongly related to reductions in underage drinking driver fatal crashes. It is important to note, however, that differences across states in patterns of underage alcohol use and drinking-related problems may exist that call for varying mixes of legal provisions. Such differences across states in effectiveness of laws could also explain why we found few significant results. Perhaps clusters of certain laws, scored using the Delphi method, might show a significant relationship to reductions in underage drinking driver fatal crashes. This should be explored.

A likely additional explanation is that the awareness of these laws by youth and the enforcement of these laws may play a much greater role than their existence or strength. The one law that indicated an association with lower levels of underage drinking drivers in fatal crashes was that law prohibiting the use of fake identification. This seems logical for the following reasons: (1) most youth are probably keenly aware that it is illegal to use a fake ID (this is especially true after 9/11); (2) this is a premeditated illegal act (the youth must show the ID to some authority such as a bouncer, bartender, store clerk) that may inherently decrease its occurrence if the sanction is considered severe; (3) there is at least a loss of one’s driver’s license as a sanction for a conviction and many youth highly value their driving privilege.

Most of the basic underage drinking laws have been in place since the mid-1980s and have produced a substantial reduction in underage drinking. Some laws (GDL with night restrictions, Keg Registration, and ZT) have been adopted more recently. Nevertheless, teenagers as young as 13 appear to find it easy to obtain alcohol, and alcohol-related deaths of drivers aged 20 and younger have not changed in the last decade and remain a serious problem. The lack of differentiation between 16 laws considered in this study suggests that MLDA laws are primarily having their impact by their presence (or absence) as composite “lump” package—through deterrence created through public media and general familiarity with the age 21 limit—and that the nuanced differences of additional components are perhaps too subtle to be perceived (or at least to be detected with the grossness of the outcome measure available). It is doubtful that youth are aware of the existence of each of the MLDA 21 law components in their state. Where differential impacts of the various MLDA laws might be measured is in the extent to which they are enforced, which is believed to vary substantially from state to state. Unfortunately, information on the level of enforcement of MLDA laws is very difficult to obtain. Some of the MLDA law elements and provisions may lend themselves to effective enforcement more than others. As a result, this may provide a better basis for mounting programs that will be effective in producing a further reduction in underage drinking consequences. This study, which could only analyze the presence, absence and strength of the laws, did not have the opportunity to uncover the impact of the enforcement of the laws, which may be the most important factor in MLDA effectiveness.

5. CONCLUSION

The results seem to support stronger laws against use of false ID and to confirm previous research and recommendations regarding the presence (but not strength) of the core purchase and possession laws. Even without substantial enforcement, it may be important for states to adopt effective expanded MLDA 21 laws (Toomey et al., 1996) to have a good foundation in preventing, or at least reducing, underage drinking. Further research is needed to address the following questions:

What are the enforcement levels of the 16 components of the underage drinking laws and are they related to underage drinking deterrence?

What other characteristics of the state (e.g., level of public awareness of the core and expanded MLDA 21 laws, other alcohol laws and policies, enforcement intensity) are associated with significant decreases in underage drinking driver fatal crashes?

These results do not necessarily mean that the only effective law of the expanded MLDA 21 laws was making it illegal to use fake identification to purchase alcohol. They do indicate that the existence and strength of the expanded MLDA laws (as we coded the strength) probably have limited effects. Prior research has indicated that ZT laws (Voas et al., 2003) and GDL night restrictions (Williams and Preusser, 1997) were effective in pre-post analyses. In this regard, the enactment dates are also available for ZT laws, GDL laws, keg registration laws, and use-and-lose laws in the states. Perhaps using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) may show an effect for some of these expanded MLDA 21 laws. The results of these and other analyses could help states establish a legislative agenda that will focus on the most effective laws and policies they do not already have.

Recently, there has been a movement to lower the drinking age to 18 in the states (Wasley, 2007). If that occurs, it will mean that not only would the core possession and purchase laws be lowered from 21 to 18, but the foundation for most of the expanded MLDA laws would also be affected. MLDA 21 laws have been shown to be effective when adopted and currently keep the underage 21 drinking driver traffic fatalities at a static level. Lowering the MLDA, as was done in the 1970s in the U.S., has recently been shown to dramatically increase alcohol-related fatalities and injuries (Kypri et al., 2006) and could reverse the protective benefits achieved over the past several decades in the United States.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The research for this article was supported by two grants: one from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant No. AA015599-01) and one from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant No. 053129).

8. Appendix A

8.1 Possession

This law applies to youth aged 20 and younger. All states prohibit possession of alcoholic beverages by people aged 20 and younger; however, many states apply various statutory exceptions. Location exceptions permit youth to legally possess alcohol in certain places such as a private residence. Family exceptions allow youth to possess alcohol under certain conditions such as the presence or permission of a family member (e.g., a parent/guardian or spouse). In most states, possession refers to a container, not alcohol in the body. Several states, however, have enacted internal possession provisions that permit police to press charges against underage drinkers because of what is in their bodies. The data for this law came from the NIAAA APIS (updated through 1/1/2005) and, in part, from a Washington Post article on February 5, 2006, regarding internal possession provisions.

The three location exceptions (any private location, any private residence, parents’/guardians’ home only) represent an ordered variable; for any given state only one location exception applies. Any private location is the most liberal location exception and thus results in a larger point deduction from a state’s base score than the exception for parents’/guardians’ home only, which is the most limited location exception. In addition, location exceptions may be conditioned on family variables (i.e., a minor can possess in any private location if a parent gives consent). Such situations are more circumscribed than a location exception that is unconditional (i.e., minor can possess in any private location). For any given location exception, conditional exceptions result in one-half the point deduction from the base score than the same unconditional location exception.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Any private location: -6.0 points (unconditional); -3.0 points (conditional)

Any private residence: -4.0 points (unconditional); -2.0 points (conditional)

Parents’/guardians’ home only: -2.0 points (unconditional); -1.0 (conditional)

Provision for internal possession (i.e., use of positive BAC as evidence of possession): +1.0 point

With a base score of 7 points allotted for having a possession law, scores can range from 0 (no law) to 8.0 (law with no location exceptions and one point for an internal possession provision).

8.2 Consumption

This law also targets youth aged 20 and younger. Most states specifically prohibit minors (defined in this document as being younger than age 21) from consuming alcoholic beverages. Note that this means observed drinking in most cases, not merely the presence of a positive BAC from a breath test. As with possession, many states have one or more statutory exceptions to this law.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Any private location: -6.0 points (unconditional); -3.0 points (conditional)

Any private residence: -4.0 points (unconditional); -2.0 points (conditional)

Parents’/guardians’ home only: -2.0 points (unconditional); -1.0 (conditional)

With a base score of 7 points allotted to a state for having a consumption law, scores can range from 0 (no law) to 7.0 (law with no location exceptions).

8.3 Purchase

This law targets youth aged 20 and younger. States were coded as having this law if their policies specifically prohibit the purchase or attempted purchase of alcoholic beverages by minors. Additionally, states received a point if they contained a provision for minors to purchase alcohol for law enforcement purposes.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Provision for youth to purchase alcohol for law enforcement purposes: +1.0 point

With a base score of 1 point (for having an underage purchase law), states are coded as 0 (no law), 1 (law with no provision for youth to purchase alcohol for enforcement purposes), and 2 (law plus ability to use minors in compliance checks). Technically, four states (Delaware, Indiana, New York and Vermont) do not have laws that specifically make it illegal for persons younger than age 21 to purchase alcohol. However, the federal government ruled that they were in compliance with the federal law because their possession laws were strong enough to cover and enforce underage youth purchasing or attempting to purchase alcohol.

8.4 Furnishing/Selling

This law targets licensed alcohol outlets and adults who provide alcohol to youth aged 20 and younger. All states have laws prohibiting the furnishing of alcoholic beverages to minors. As with possession and consumption, many states have one or more exceptions to this law.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Any private location: -6.0 points (unconditional); -3.0 points (conditional)

Any private residence: -4.0 points (unconditional); -2.0 points (conditional)

Parents’/guardians’ home only: -2.0 points (unconditional); -1.0 (conditional)

Provision for affirmative defense (i.e., for retailer to be exonerated of charges if minor not charged): -1.0 point

With a base score of 8 points for having a furnishing law, scores can range from 0 (no law) to 8.0 (law with no location exceptions and no affirmative defense for sellers).

8.5 Age for On-Premise Sellers/Servers

This law applies to licensed alcohol outlets. State laws specify a minimum age for employees who serve or dispense alcoholic beverages in on-premise establishments. In some states, the minimum age for serving and bartending beer, wine, and/or spirits is 21; however, some states permit those younger than age 21 to sell alcohol. Additionally, some states specify conditions that must be met if minors are permitted to serve or dispense alcohol, such as having a manager present.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Require 21 as minimum age for alcohol servers for all 3 beverage types (beer, wine, and spirits): +4.0 points

Require 21 as minimum age for bartenders for all three beverage types (beer, wine, and spirits): +4.0 points

Conditions that must be met if underage youth allowed to serve alcohol: +1.0 point each for (a) manager present, (b) RBS training, and (c) parental consent

Conditions that must be met if underage youth allowed to bartend: +1.0 point each for (a) manager present, (b) RBS training, and (c) parental consent

Scores range from 0 (law does not require age 21 for both serving and bartending and the law does not provide for any conditions that must be met for underage youth to serve/bartend) to 8.0 (law requires age 21 for both serving and bartending).

8.6 Age for Off-Premise Sellers

This law applies to licensed alcohol outlets. Most states have laws that specify the ages at which employees may sell alcohol in off-premise establishments. As with laws regarding the minimum age for on-premise servers and bartenders, some states require employees be age 21 to sell beer, wine, and/or spirits; those that allow minors to sell may require certain conditions be satisfied.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Require 21 as minimum age for alcohol sellers for all three beverage types (beer, wine, and spirits): +4.0 points

Conditions that must be met if underage youth allowed to sell alcohol: +1.0 point each for (a) manager present, (b) RBS training, and (c) parental consent

Scores range from 0 (law does not require age 21 to sell alcohol) to 4.0 (21 minimum age to sell alcohol at off-premise establishments).

8.7 Zero Tolerance

This law applies to youth aged 20 and younger. In all states it is illegal for people younger than 21 to drive with any measurable level of alcohol in their systems. States were coded as having this law if the minimum BAC limit for underage operators of noncommercial automobiles, trucks, and motorcycles was ≤.02. Information on license sanctions for violating ZT laws were extracted and coded from NHTSA’s Digest of Impaired Driving and Selected Beverage Control Laws (NHTSA, 2006).

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Administrative license sanction: +4.0 points if mandatory, +2.0 points if discretionary

- Minimum length of administrative license sanction:

- 0 points for 30 days and less

- +1.0 point for 31 to 90 days

- +2.0 points for 91 days or longer

Criminal license sanction: +2.0 point if mandatory, +1.0 point if discretionary

- Minimum length of criminal license sanction:

- 0 points for 30 days and less

- +1.0 point for 31 to 90 days

- +2.0 points for 91 days or longer

Scores range from 1.0 (discretionary criminal license sanction only with a maximum suspension period of 30 days or less) to 10.0 (both mandatory administrative and mandatory criminal license sanctions of 91 days or longer).

8.8 Use and Lose

This law applies to youth aged 20 and younger. This term describes laws that authorize driver licensing actions against persons found to be using or in possession of illicit drugs, and against young persons found to be drinking, purchasing or in possession of alcoholic beverages. States vary in how many of the alcohol violations (i.e., underage purchase, possession, consumption) are covered as well as whether the license suspension or revocation for violating the law is mandatory versus discretionary.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

License sanction applicable to underage purchase: +2.0 points if mandatory, +1.0 point if discretionary

License sanction applicable to underage possession: +2.0 points if mandatory, +1.0 point if discretionary

License sanction applicable to underage consumption: +2.0 points if mandatory, +1.0 point if discretionary

Upper age limit less than 21: -1.0 point

- Minimum length of suspension (same as for ZT):

- 0 points for 30 days and less;

- +1.0 point for 31 to 90 days;

- +2.0 points for 91 days or longer

Scores range from 0 (no use and lose law) to 8.0 (license sanction is mandatory for all three violations—purchase, possession, and consumption; minimum length of license suspension is 91+ days, and law applies to all minors).

8.9 Keg Registration

This law applies to licensed alcohol outlets. It allows alcohol beverage control agents to locate adults who purchase beer kegs for underage drinking parties. States were coded as having this law if they required wholesalers or retailers to attach an identification number to their kegs and collect identifying information from the keg purchaser.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Kegs prohibited: +8.0 points

For prohibited actions: +1.0 point for possession of an unregistered/unlabeled keg, +1.0 point for destruction of the label on a keg

Deposit required: +1.0 point

Purchaser information collected: +1.0 point for requiring retailer to record purchaser’s identification number or the form of ID presented together with purchaser’s name, address, and date of birth; +1.0 point for requiring retailer to record address where keg will be consumed

Warning to purchaser: +1.0 point for passive; +2.0 points for active

For states that allow keg sales, scores can range from 0 (no law) to 7.0 (law prohibiting both unregistered/unlabeled kegs and destruction of the label on a keg, requiring a deposit regardless of amount, requiring two additional pieces of information be collected from purchaser beyond name and address, requiring active warning to purchaser). Utah, which prohibits kegs altogether, was assigned a score of 8.0 as banning kegs is a stronger method of keg regulation.

8.10 Responsible Beverage Service Training

This law applies to licensed alcohol outlets. Responsible beverage service (RBS) or “server training” programs involve (1) development and implementation of policies and procedures for preventing alcohol sales and service to minors and intoxicated persons and (2) training managers and servers/clerks to implement policies and procedures effectively. Such programs may be mandatory or voluntary. In APIS, a program is considered to be mandatory if state provisions require at least one specified category of alcohol retail employees (e.g., clerks, managers, or owners) to attend training. States with voluntary programs offer incentives to licensees to participate in RBS training such as discounts on dram shop liability insurance and protection from license revocation for sales to minors or intoxicated persons.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Type(s) of RBS program: +2.0 points for mandatory; +1.0 point for voluntary program

Personnel trained in mandatory program: +1.0 point for manager; +1.0 point for server/seller

Incentives for voluntary program: +1.0 point each for: (1) liability defense in dram shop litigation, (2) mitigation of penalties for sales to minors or intoxicated patrons, (3) dram shop insurance discounts, (4) protection of license revocation/suspension for sales to minors or intoxicated persons

Type of establishment covered: +1.0 point for on-premises outlets, +1.0 point for off-premises outlets

Type of licensee covered: +1.0 point for new licensees, +1.0 point for existing licensees

Scores primarily range from 0 (no RBS law) to 8.0 (mandatory program requiring both managers and servers to be trained, covering both on- and off-premise outlets and both new and existing licensees). A few states have both a mandatory program and a voluntary program (booster sessions), so scores could theoretically be as high as 13.0 if a state had both a strong mandatory program and a voluntary or booster program that included all four incentives.

8.11 Use of Fake ID

This law applies to youth aged 20 and younger. All states prohibit the use of false identification cards by minors.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

License sanction procedure: +2.0 points for administrative or both administrative and judicial; +1.0 for judicial only

Scores range from 1.0 (law with no license sanction procedure) to 3.0 (law with administrative or both administrative and judicial license sanction procedures).

8.12 Transfer/Production of False IDs

This law applies to manufacturers of fake IDs and persons who transfer or sell fake IDs. In some states, it is illegal to produce false IDs and/or to transfer an ID to another person.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Lend, transfer, sale of false ID criminalized: +1.0 point yes; 0.0 points no

Manufacturing and distributing false ID criminalized: +1.0 point yes; 0.0 points no

Scores range from 0 (no law against providing false ID) to 1.0 (one action above prohibited) to a maximum of 2.0 (both actions—manufacturing/distributing and lend/transfer/sale—prohibited).

8.13 Retailer Support Provisions for False ID

This law applies to licensed alcohol outlets. Some states include provisions to assist retailers in avoiding sales to potential buyers who present false identification.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Incentives for retailers to use electronic scanners that read ID: +1.0 point yes

Distinctive licenses: +2.0 points yes

Seizure of suspicious ID by retailer permitted: +1.0 point yes

Right to sue minor who uses fake ID for any losses or fines suffered by retailer as a result of an illegal sale: +1.0 point yes

Affirmative defense that can be asserted by retailer: -1.0 point for general (i.e., retailer came to good faith or reasonable decision that purchaser was 21 or older); 0.0 points for specific (i.e., retailer inspected false ID and came to reasonable conclusion based on appearance that it was valid) or none

Scores range from 0 (no retailer support provisions for false ID) to 5.0 (all provisions except general affirmative defense).

8.14 Social Host Liability—Underage Parties

This law applies to adults who host underage drinking parties. Social host liability refers to a law holding individuals criminally responsible for underage drinking events on property they own, lease, or otherwise control.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Type of statute: +2.0 points for general (i.e., prohibit individuals from allowing or permitting underage drinking on their property generally without reference to parties, gatherings, or similar terms); +1.0 point for specific (reference specific places/events where allowing underage drinking on property is prohibited such as parties, gatherings)

Underage guest actions triggering violation: +1.0 point for each: (1) possession, (2) consumption, (3) intention to possess or consume

Property type covered: +1.0 point each for: (1) residence, (2) outdoor, (3) other

Knowledge standard (i.e., threshold for hosts’ knowledge or action regarding an underage drinking party that must be satisfied before criminal liability is imposed): +2.0 points for negligence (i.e., host knew or should have known of event’s occurrence), +1.0 point for knowledge (i.e., no action required), 0 for overt act (i.e., host must have actual knowledge and commit an act that contributes to the occurrence)

Preventive action by social host negates criminal liability: -1.0 point if yes

Exceptions: -1.0 point for family, -1.0 point for resident of household, -1.0 point for other

Scores range from 0 (no law) to 10.0 (general statute covering all underage actions, all property types, with negligence as the knowledge standard and no exceptions).

8.15 GDL with Night Restrictions

This law applies to youth with intermediate licenses. GDL is a system in which beginning drivers are required to go through three stages of limited driving privileges. States were coded as having this law if they had a three-stage GDL system and if they had restrictions on unsupervised nighttime driving during the second stage. Limitations on nighttime driving are designed to reduce drinking and driving by underage drivers.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

Start time of nighttime driving restriction = 10 p.m. or earlier: +3.0 points; 10:01 p.m. to midnight: +2.0 points; After 12:01 a.m.: +1.0 point

Scores range from 0 (no three-stage GDL with nighttime driving restrictions in intermediate phase) to 3.0 (three-stage GDL with nighttime restriction starting at 10 p.m. or earlier).

8.16 State Control of Alcohol

This law applies to the states with regard to their system of controlling alcohol distribution. There are two types of retail alcohol distribution: license and control (APIS uses the term “state-run”). For each alcohol beverage type (beer, wine, distilled spirits) a state may use a state-run distribution system, a system of private licensed sellers, or some combination of these. A state-run system is considered to have better control of the sale of alcohol.

Scoring of exceptions/provisions:

State-run retail distribution systems: +1.0 point for each beverage type that is under state-run system: (1) beer, (2) wine, (3) spirits

Scores theoretically range from 0 (no part of retail distribution system is state-run) to 3.0 (state-run retail system for all three beverage types), although as no state has a state-run system for beer, scores range from 0 to 2.0.

9. Appendix B

Table B1.

Factors formed by the different laws

| Factor # |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Underage drinking law | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1 | Underage Possession | .572 | -.320 | -.542 | |||

| 2 | Underage Consumption | .642 | |||||

| 3 | Responsible Beverage Service | .699 | |||||

| 4 | State Control of Alcohol-Retail Distribution Systems | .711 | |||||

| 5 | Min Age for On-Premise Sellers/ Servers | .809 | |||||

| 6 | Min Age for Off- Premise Sellers | .880 | |||||

| 7 | Graduated Licensing with Nighttime Provisions | .809 | |||||

| 8 | Use/ Lose | .762 | |||||

| 9 | Social Host Liability-Underage Parties | .659 | |||||

| 10 | Underage Purchase / Attempted Purchase | .802 | .310 | ||||

| 11 | Zero Tolerance | .695 | |||||

| 12 | Keg Registration | .868 | |||||

| 13 | False ID- Use | -.488 | .360 | -.309 | |||

| 14 | False ID- Transfer/ Production | ||||||

| 15 | False ID-Retailer Support Provisions | -.634 | .306 | ||||

| 16 | Furnishing to Minors | .881 | |||||

| % of variance each factor accounts for (Total = 65.7%) | 14.8 | 12.9 | 10.5 | 9.6 | 9.3 | 8.5 | |

Note: Pattern loadings with absolute values < 0.3 were excluded from this table.

Principal Component Analysis, with Quartimax rotation, was used to extract the above factors.

Table B2.

Descriptive statistics

| Law | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underage Possession | 51 | 1 | 8 | 5.59 | 2.238 |

| Underage Consumption | 51 | 0 | 7 | 3.59 | 3.245 |

| Underage Purchase / Attempted Purchase | 51 | 0 | 2 | 1.31 | .616 |

| Furnishing to Minors | 51 | 5 | 8 | 7.57 | .900 |

| Min Age for On-Premise Sellers/ Servers | 51 | 0 | 8 | 2.12 | 2.551 |

| Min Age for Off-Premise Sellers | 51 | 0 | 4 | 1.06 | 1.529 |

| Zero Tolerance | 51 | 1 | 10 | 6.59 | 2.174 |

| Use/Lose | 51 | 0 | 8 | 3.49 | 2.693 |

| Keg Registration | 51 | 0 | 8 | 1.82 | 2.224 |

| Responsible Beverage Service | 51 | 0 | 11 | 3.75 | 3.352 |

| False ID-Use | 51 | 1 | 3 | 1.94 | .544 |

| False ID-Transfer/ Production | 51 | 0 | 2 | .69 | .787 |

| False ID-Retailer Support Provisions | 51 | 0 | 3 | 1.96 | .848 |

| Social Host Liability-Underage Parties | 51 | 0 | 8 | 1.84 | 2.641 |

| Graduated Licensing with Nighttime Provisions | 51 | 0 | 3 | 1.75 | .891 |

| State Control of Alcohol-Retail Distribution Systems | 51 | 0 | 2 | .22 | .503 |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

7. REFERENCES

- Arnold R. Effect of raising the legal drinking age on driver involvement in fatal crashes: The experience of thirteen states. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 1985. DOT HS 806 902. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SA, Fields M, Voas RB. Enforcement of zero tolerance laws in the US - Prevention Section. In: Laurell H, Schlyter F, editors. Drugs and Traffic Safety; Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety - T 2000: Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Alcohol; ICADTS, Stockholm, Sweden. May 22-26, 2000.2000. pp. 713–718. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund JH, Ulmer RG, Preusser DF. Determine Why There are Fewer Young Alcohol-Impaired Drivers. U.S. Department of Transportation; Washington, DC: 2001. DOT HS 809 348. [Google Scholar]

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety . U.S. licensing systems for young drivers: Laws as of March 2006. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety; Arlington, VA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety . U.S. licensing systems for young drivers: Laws as of May 2007. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety; Arlington, VA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Voas RB, Langley JD, Stephenson SCR, Begg DJ, Tippetts AS, Davie GS. Minimum purchasing age for alcohol and traffic crash injuries among 15- to 19- year-olds in New Zealand. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(1):126–131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.073122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis . Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2003. [Accessed on April, 2003]. at http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/departments/nrd-30/ncsa//fars.html. [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration . Digest of impaired driving and selected beverage control laws. 23 ed. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2005. [March 5, 2007. Accessed, 2006]. at http://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Wagenaar AC. Effects of minimum drinking age laws on alcohol use, related behaviors and traffic crash involvement among American youth: 1976-1987. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(5):478–491. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill B, Kyrychenko SY, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety Use and misuse of motor vehicle crash death rates in assessing highway safety performance. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2006;7(4):307–318. doi: 10.1080/15389580600832661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponicki WR, Gruenewald PJ, LaScala EA. Joint impacts of minimum legal drinking age and beer taxes on US youth traffic fatalities, 1975 to 2001. Alcohol Clinical Experimental Research. 2007;31(5):804–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, Nichols JL, Alao MO, Carande-Kulis VG, Zaza S, Sosin DM, Thompson RS, Task Force on Community Preventive Services Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21(4 Suppl):66–88. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian R. Transitioning to multiple imputation - A new method to estimate missing blood alcohol concentration (BAC) values in FARS. Mathematical Analysis Division, National Center for Statistics and Analysis, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation; Washington, DC: 2002. DOT HS 809 403. [Google Scholar]

- Tippetts AS, Voas RB, Fell JC, Nichols JL. A meta-analysis of .08 BAC laws in 19 jurisdictions in the United States. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2005;37(1):149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Rosenfeld C, Wagenaar AC. The minimum legal drinking age: History, effectiveness, and ongoing debate. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1996;20(4):213–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Tippetts AS, Fell J. Assessing the effectiveness of minimum legal drinking age and zero tolerance laws in the United States. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2003;35(4):579–587. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Tippetts AS, Fell JC. The relationship of alcohol safety laws to drinking drivers in fatal crashes. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2000;32(4):483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Tippetts AS, Romano E, Fisher DA, Kelley-Baker T. Alcohol involvement in fatal crashes under three crash exposure measures. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2007;8(2):107–114. doi: 10.1080/15389580601041403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC. Effects of drivers’ license suspension policies on alcohol-related crash involvement: Long-term follow-up in forty-six states. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(8):1399–1406. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasley AF. Taking on 21. [Accessed, 2007];The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2007 at http://chronicle.com/weekly/v53/i31/31a03501.htm.

- Williams AF, Preusser DF. Night driving restrictions for youthful drivers: A literature review and commentary. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1997;18(3):334–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womble K. Impact of minimum drinking age laws on fatal crash involvements: An update of the NHTSA analysis. Journal of Traffic Safety Education. 1989;37:4–5. [Google Scholar]