Abstract

Objective

Based on theories regarding cognitive representations of illness and processes of conceptual change, a Representational Intervention to Decrease Cancer Pain (RIDcancerPain) was developed and its efficacy tested.

Design

A two-group RCT (RIDcancerPain versus control) with outcome and mediating variables assessed at baseline (T1) and one and two months later (T2 and T3). Subjects were 176 adults with pain related to metastatic cancer.

Main Outcome Measures

Outcome variables were two pain severity measures (BPI and TPQM), pain interference with life, and overall quality of life. Mediating variables were attitudinal barriers to pain management and coping (medication use).

Results

150 subjects completed the study. Subjects in RIDcancerPain (T1-T2 and T1-T3) showed greater decreases in Barrier scores than those in control. Subjects in RIDcancerPain (T1-T3) showed greater decreases in pain severity than those in control. Change in Barriers scores mediated the effect of RIDcancerPain on pain severity.

Conclusion

RIDcancerPain was efficacious with respect to some outcomes. Further work is needed to strengthen it.

Unrelieved pain impairs the quality of life of many individuals with cancer (Wells, 2000). Despite years of attention to this problem, from both clinicians and researchers, patients continue to under-utilize available analgesic medications (Miaskowski, Dodd, West, Paul, Tripathy, Koo, et al., 2001; Ward, Goldberg, Miller-McCauley, Mueller, Nolan, Pawlik-Plank, et al., 1993). Under-utilization of analgesics often results from patients’ uninformed beliefs about reporting pain and using analgesics. These include their concerns about side effects and their misconceptions about pain control such as the exaggerated fear of addiction (Gunnarsdottir, Donovan, Serlin, Voge, & Ward, 2002; Ward et al., 1993). Previous trials of patient education interventions designed to overcome such barriers have involved interventions that were empirically rather than theoretically derived, making it difficult to replicate the studies or generalize the findings. Furthermore, scant attention has been given to determining if intervention effects differ by gender, even though women compared to men experience less optimal pain management (Cleeland, Gonin, Baez, Loehrer, & Pandya, 1997).

Based on theories regarding illness cognition and conceptual change (Hewson & Thorley, 1989; Leventhal & Diefenbach, 1991), an innovative representational approach to patient education has been developed (Donovan & Ward, 2001). Using this representational approach, we have designed an intervention to overcome barriers to cancer pain management, a Representational Intervention to Decrease Cancer Pain (RIDcancerPain). The purpose of this study was to test the efficacy of RIDcancerPain.

Patient-related Barriers to Pain Management

A number of attitudinal barriers to pain management have been identified among cancer patients. One of these barriers is the fatalistic belief that cancer pain is inevitable and uncontrollable (Sherwood, Adams-McNeil, Starck, Nieto, & Thompson, 2000). Other barriers include patients’ fear of addiction and the fear that analgesics cause immune suppression (Breitbart, Passik, McDonald, Rosenfeld, Smith, Kaim, et al., 1998). Additional barriers related to physiological effects of analgesics include concerns that analgesics may block one’s ability to monitor illness symptoms and the belief that side effects from pain medication are unmanageable (Hawkins, 1997). Finally, some barriers relate to communication with care providers, such as the belief that ‘good’ patients do not complain about pain, and concerns that reporting pain will distract the physician from treating the cancer (Gunnarsdottir et al., 2002). These attitudinal barriers are inversely related to patients’ coping efforts (e.g. use of pain medication) and, consequently, to outcomes such as pain severity and well being (Ward, Carlson-Dakes, Hughes, Kwekkeboom, & Donovan 1998). Older persons have higher barriers scores than do younger persons (Gunnarsdottir et al., 2002), suggesting the need to control for age when examining the effect of an educational intervention.

Tests of Educational Interventions

Targeting educational interventions toward patients has the potential to improve pain management. If patients are well informed, their involvement in their own care will be enhanced, and they will be more likely to report pain in a timely fashion and be more likely to make use of analgesic medications (Thomas & Weiss, 2000). Several trials of patient education interventions to enhance pain management have been conducted. In 1987, Rimer and colleagues tested a 15-minute interactive nurse-counseling intervention supplemented with printed material versus care as usual in a randomized trial. They found that the intervention had a significant beneficial effect on fears of addiction, worry about tolerance, and correct medication usage. De Wit and colleagues (1997) tested a 30-60 minute, one-on-one, nurse-delivered, tailored intervention that was designed to enhance patients’ knowledge about pain management and to stimulate patients’ help-seeking behavior. Data revealed a small but statistically significant effect in favor of intervention over control in some subgroups of patients (those without district nursing) with respect to pain intensity but not quality of life. Similarly, Clotfelter (1999) developed an education program consisting of a booklet and companion video that addressed a variety of topics related to cancer pain management in the elderly. In a randomized trial, she compared this program to care-as-usual and found that the program significantly reduced pain intensity. Oliver and colleagues conducted a randomized trial with 78 patients with cancer (Oliver, Kravitz, Kaplan, & Meyers, 2001). Subjects in the intervention group received individualized information about misconceptions (based on scores on baseline measures of knowledge), supplemental information in a booklet, and coaching regarding communication with physicians about pain. Patients receiving the intervention had larger decreases in their pain than did those in the control condition, but there were no group differences in pain knowledge or in adherence to analgesic therapy. Wells and colleagues (2003) tested the effects of continued access to information following a baseline education program provided to patients and their caregivers. Subjects received the structured pain education program and were then randomized to usual care, pain hotline, or weekly provider-initiated follow-up calls for a month after they received the educational program. Subjects had improvements in knowledge and beliefs immediately following the educational program, but continued access to information had no effect on long-term outcomes of pain intensity.

Each of these studies made a contribution to the care of persons experiencing cancer-related pain, however, their impact is limited for two reasons. First, because they were empirically rather than theoretically guided, it is not clear how or why beneficial effects were obtained. If results are to be generalized to practice, it is critical that the intervention be grounded in a theoretical basis (Leventhal & Johnson, 1984). A second limitation is that a differential response based on gender was not evaluated in any of these studies, in spite of the fact that women are more at risk than are men for less than optimal pain management (Cleeland et al., 1997).

Development of a Representational Approach to Patient Education

The Representational Approach to patient education (Donovan & Ward, 2001) is based on theory regarding cognitive representations of illness (Leventhal & Diefenbach, 1991) and on theory regarding the process of conceptual change (Hewson & Thorley, 1989). Leventhal has asserted that people have common sense beliefs, or representations, about their health problems (Leventhal & Diefenbach, 1991). An illness representation is the set of thoughts - whether medically sound or not - that a person has about a health problem. Illness representations have five core dimensions: identity, cause, time-line, consequences, and cure/control. Identity refers to how one describes the symptoms of a health problem. Cause refers to beliefs about the origin of the health problem. Time-line relates to temporal ideas, such as whether the problem is acute, chronic, or cyclic in nature. Consequences are ideas about the short- and long-term outcomes of the problem. Cure/control refers to beliefs about the extent to which one can control or cure a health problem.

Representations are knowledge structures, and as such serve two functions. They guide interpretation and processing of new information, and they guide the selection of coping strategies. Representations are resistant to change and consequently can serve as impediments to the success of educational interventions. Traditional educational interventions present new information or new coping skills without first addressing the well-established beliefs that are driving the selection of current coping strategies. Therefore, while patients may become knowledgeable about new strategies, it is unlikely that they will translate new knowledge into behavior change if the strategies are inconsistent or incompatible with existing beliefs.

Literature on conceptual change suggests ways to increase patients’ acceptance and implementation of new information. According to Posner, learning is not the acquisition of a set of correct responses or behaviors, but rather is a process of conceptual change (Posner, Strike, Hewson & Gertzog, 1982). Conceptual change refers to the process by which persons’ conceptions (beliefs) change under the impact of new ideas. Posner et al. (1982) proposed that conceptual change occurs when (a) a person is dissatisfied with an existing conception, (b) an intelligible and plausible alternative is offered, and (c) it is clear that the new conception will be beneficial. Change is also facilitated when individuals are given the opportunity to monitor and comment on their own ideas (Hewson & Thorley, 1989).

Based on these theories, the Representational Approach to patient education was developed (Donovan & Ward, 2001). The critical point in the Representational Approach is that assessing a patient’s representation about a health problem can prepare that patient to have conceptual change about misconceptions that are embedded in the representation. Encouraging individuals to describe their illness beliefs along the five dimensions of illness representation described earlier can set the stage for conceptual change in three ways. First, through a detailed discussion of illness beliefs, patients have an opportunity to examine these beliefs carefully and to comment on them. During this discussion, the status of existing, erroneous assumptions can be mitigated by explicitly discussing the limitations, or consequences, of adhering to and acting upon beliefs that are misconceptions. Second, once an individual’s illness representation has been assessed, educational information can be presented in a highly contextual manner such that the new information will be seen as a plausible replacement for misconceptions. Finally, discussing the benefits of replacing existing misconceptions with plausible information can promote the acceptance of new information, solving the problems associated with existing misconceptions. Because assessment of individuals’ representations is the core of the Representational Approach, the patient education is provided in the context of patients’ own ideas or representations.

Based on this representational approach and on previous work regarding patient-related barriers to pain management, we developed a Representational Intervention to Decrease Cancer Pain (RIDcancerPain). RIDcancerPain is delivered in a single 1:1 face-to-face psychoeducational session that lasts from 20 minutes to an hour. There are five steps, starting with a representational assessment in which the patient is describes his/her beliefs about cancer pain with respect to cause, timeline, consequences, cure/control, and identity. This assessment reveals misconceptions (barriers) that are embedded in the representation. The second step involves an exploration of misconceptions that were revealed. The third step is a discussion of problems that arise from holding beliefs that are misconceptions -- i.e., what one loses by maintaining those beliefs. In the fourth step replacement information is provided. The fifth step is an opportunity for clarification and a summary of what has been discussed.

The hypotheses tested in this study were (a) that compared to subjects receiving standard educational information (SEI), subjects receiving RIDcancerPain would show greater change from before to after the intervention with respect to beliefs, coping, pain severity, pain interference with life and overall well-being, and (b) the effect of RIDcancerPain on pain severity, interference and well-being would be mediated by changes in beliefs (barriers) and by coping (analgesic use). In addition, we addressed whether intervention effects would be similar across gender.

Methods

Design

The design was a two-group randomized trial with measures taken at baseline (T1) and one and two months later (T2 and T3). To assure that groups were similar with respect to pain severity at study entry, subjects were blocked by level of pain (BPI worst pain in the past two weeks of 1 to 4 versus 5 to 10) before being randomized. Randomization was accomplished according to random numbers generated by Excel’s RAND function. Power analysis determined that two samples of size 64 would yield .80 power to detect an effect size of 0.5 standard deviations, with Type I error rate of .05 assigned to two directional tests according to Holm’s (1979) sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. The sample size of 176 was planned to accommodate an attrition rate of up to 25%.

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from outpatient oncology clinics in Wisconsin, one in Madison and one in Milwaukee. Inclusion criteria were (a) age 21 or older, (b) diagnosis of metastatic cancer, and (c) a rating of 1 or greater on a 0 to 10 scale for worst cancer related pain experienced during the past two weeks. Exclusion criteria were (a) inability to read English, (b) incarceration, and (c) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 3 or 4 (patient is in bed more than 50% of the time).

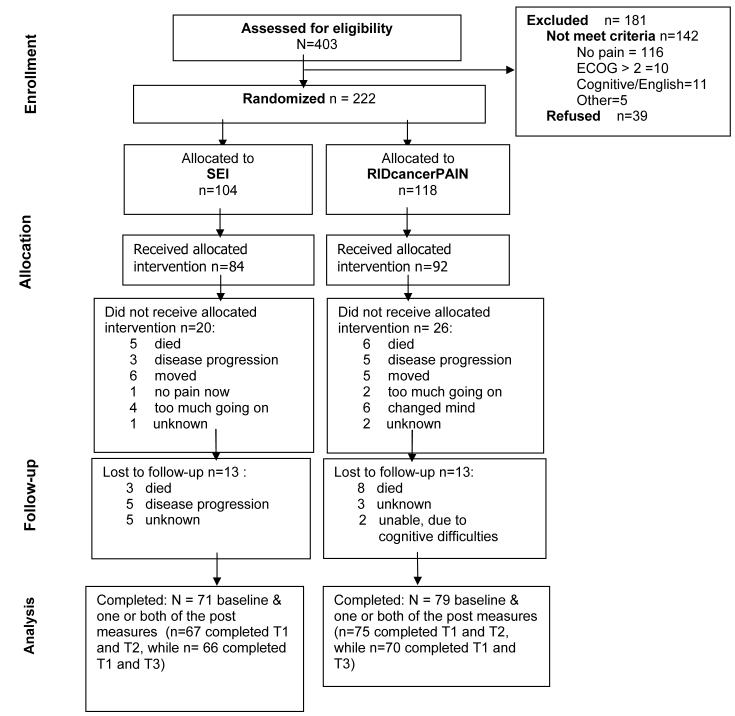

Figure 1 displays the flow of participants through the study. Two hundred and twenty two persons agreed to join the study, but 46 (21%) dropped out between providing initial consent and actually completing baseline measures and receiving the intervention. Much of this attrition was due to death or advances in illness (n = 19), or to care being transferred to another facility (n=11). Of the 176 subjects who completed baseline measures and received the intervention, 26 (15%) did not complete T2 and T3 measures. Conversely, 150 subjects completed T1 and T2, or T1 and T3, or T1, T2, and T3. The mean (SD) age of the 176 subjects was 55.11 (11.52). Demographic, disease, and treatment information for the 176 subjects is provided in Table 1. Men (n=75) and women (n=101) did not differ with respect to age, years of education, recruitment site, marital status, or income.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of RIDcancerPAIN.

Table 1. Demographic and Health Related Variables at Baseline by Treatment Group (N=176).

| SEI (n=84) |

RIDPAIN (n=92) |

Total (N=176) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Study Site | ||||||

| Madison | 72 | 85.7 | 77 | 83.7 | 149 | 84.7 |

| Milwaukee | 12 | 14.3 | 15 | 16.3 | 27 | 15.3 |

| Pain Group | ||||||

| Low (1-4) | 42 | 50.0 | 51 | 55.4 | 93 | 52.8 |

| High (5-10) | 42 | 50.0 | 41 | 44.6 | 83 | 47.2 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 38 | 45.2 | 37 | 40.2 | 75 | 42.6 |

| Female | 46 | 54.8 | 55 | 59.8 | 101 | 57.4 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 61 | 72.7 | 64 | 71.8 | 125 | 71.0 |

| Single | 23 | 27.3 | 26 | 25.2 | 49 | 27.2 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.2 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 75 | 89.3 | 78 | 84.6 | 153 | 86.9 |

| African Am | 7 | 8.3 | 11 | 12.1 | 18 | 10.2 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.2 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Asian | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.1 |

| East Indian | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Income Level | ||||||

| Below $20,000 | 12 | 14.2 | 16 | 17.3 | 28 | 16.0 |

| $20,000-49,999 | 27 | 32.2 | 26 | 28.3 | 53 | 30.1 |

| $50,000-99,999 | 25 | 29.8 | 23 | 25.0 | 48 | 27.3 |

| Over 100,000 | 2 | 2.4 | 9 | 9.8 | 11 | 6.3 |

| Not Respond | 18 | 21.4 | 18 | 19.6 | 36 | 20.2 |

| Ca Dx | ||||||

| Breast | 18 | 21.4 | 24 | 26.1 | 42 | 23.9 |

| Lung | 16 | 19.0 | 8 | 8.7 | 24 | 13.6 |

| GI | 16 | 19.0 | 28 | 30.4 | 44 | 25.0 |

| GU/GYN | 18 | 21.4 | 24 | 26.1 | 42 | 23.9 |

| Heme | 7 | 8.3 | 2 | 2.2 | 9 | 5.1 |

| Other | 9 | 10.7 | 6 | 6.5 | 15 | 8.5 |

| Other Health Problems | ||||||

| No | 54 | 64.3 | 60 | 65.2 | 114 | 64.8 |

| Yes | 29 | 34.5 | 29 | 31.5 | 58 | 33.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 1.2 | 3 | 3.3 | 4 | 2.3 |

| Current Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | 52 | 61.9 | 47 | 51.0 | 99 | 56.3 |

| Yes | 32 | 38.1 | 40 | 43.7 | 72 | 40.9 |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 5.3 | 5 | 2.8 |

Note. SEI = Standard Educational Information. RIDPAIN = A Representational Intervention to Decrease Pain.

The demographic characteristics of minorities (n=23) differed from those of Caucasians (n=153). The minorities had fewer years of education (M=12.7, SD=3.17) than did the Caucasians (M=14.1, SD=3.03) [t(168)=1.961, p=.051), and 48% of the minorities had household incomes below $20,000/year whereas this was the case for only 11% of the Caucasians [χ2 (5, 176) = 23.853, p = .000]. Therefore, minority status was used as a control variable in the analyses.

Experimental Protocols

Standard Educational Information (SEI)

This intervention served as a control for attention and for basic pain information. The patient was asked to read a booklet “Questions & Answers about Pain Medicines: Breaking Down the Barriers” that contained two major sections. The first section was a review of common beliefs (misconceptions) in a question and answer format. For example, the question, “Won’t I get addicted if I take medicine like morphine?” is followed by a brief discussion of this issue and corrective information. The second section of the booklet contained information about opioid side effect management. Reading the booklet took approximately 20 minutes. The patient was then given an opportunity to ask questions about the booklet. A telephone call was made by the research nurse 2 to 3 days later to give the patient an opportunity to ask questions and make comments.

RIDcancerPain

RIDcancerPain is an educational intervention based on the representational approach to patient education (Donovan & Ward, 2001). RIDcancerPain has five steps. In the first step, patients are asked to describe their beliefs about their cancer pain in terms of cause, timeline, consequences, cure, and control. Next, in the second step, misconceptions about reporting pain and using analgesics are identified and discussed. In the third step (creating conditions for conceptual change), patients discuss the limitations and losses that are a consequence of these misconceptions. In the fourth step the intervener provides credible information to replace the misconceptions that have been identified. The fifth step is a summary and discussion of the benefits of adopting this new information. These five steps occurred in a single session that lasted from 20 minutes to one hour, depending on the number of misconceptions that were elicited in the assessment interview. A telephone call was made by the research nurse 2 to 3 days later to give the patient an opportunity to ask questions and make comments. In a pilot study, subjects described the intervention very positively, portraying it as providing helpful, new information (Donovan & Ward, 2001).

Instruments

Beliefs about analgesic use

The Barriers Questionnaire-II (BQ) is a 27-item self-report instrument designed to measure the extent to which subjects have eight beliefs about reporting pain and using analgesics (Gunnarsdottir et al., 2002). Response options range from 0 “do not agree at all” to 5 “agree very much”. Sample items are: “Using pain medicine can harm your immune system” and “Reports of pain could distract a doctor from curing the cancer”. A mean of the 27 items was used in hypothesis testing, with higher scores indicating more negative beliefs. The content validity of the BQ-II has been supported by expert panel review. The reliability, validity, and factor-structure of the BQ-II have been supported (Gunnarsdottir et al., 2002). Internal consistency in the present study was .89.

Coping -- Adequacy of analgesic use

Adequacy of analgesic use was measured by the Pain Management Index (PMI) (Zelman, Cleeland, & Howland, 1987). Based on the WHO’s “Analgesic Ladder” for cancer pain, the PMI is a comparison of the most potent analgesic used by a subject relative to the level of that subject’s reported pain. To construct the index, one determines which of 4 levels of analgesic has been used, where the levels are: (0) no analgesic, (1) non-opioid (e.g., NSAID or Acetaminophen), (2) weak opioid (e.g. codeine or oxycodone in combination with a non-opioid), and (3) strong opioid (e.g. morphine). One determines the subject’s level of pain by using the pain worst item from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). The following levels are used: (0) Pain worst rating of 0; (1) pain worst rating of 1 to 4; (2) pain worst rating of 5 to 6; and (3) pain worst rating of 7 to 10. The index is computed by subtracting the value of the pain level from the analgesic level. The resulting scores yield a two-category system where negative scores indicate inadequate analgesic use and scores of 0 or greater indicate acceptable analgesic use. Validity of the PMI has been demonstrated by finding predicted relationships between it and other variables, such as barriers scores (Ward et al., 1993).

Pain severity

The first of the two measures of pain severity was constructed from three items from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI; Anderson, Syrjala, & Cleeland, 2001). Subjects reported their worst pain during the past week, least pain during the past week, and pain now. Response options range from 0 “no pain” to 10 “pain as bad as I can imagine”. These items have been shown to be reliable and valid. For example, test-retest reliability of the pain worst item was .93 over a two-day period in a sample of 20 inpatients with cancer, and the pain worst item was sensitive in detecting differences, over a two-week interval, between interventions used to decrease pain (Daut, Cleeland, & Flannery., 1983). For the present study, a mean of the three items was taken, resulting in a severity item with a range of 0 to 10 called BPIseverity.

The other measure of pain severity consisted of a single item - “During the past week, when you had pain was it usually...?” Response options were 0 to 3, with the following verbal descriptors: “none”, “mild”, “moderate”, and “severe”. This item is based on one developed for the Total Pain Quality Management data set, and its validity has been supported by Gordon et al. (2002). This item is called Usual Severity in the rest of this report.

Pain interference

Pain interference was assessed with the BPI (Anderson, Syrjala & Cleeland, 2001). Subjects rated on a 0 (does not interfere) to 10 (completely interferes) scale the extent to which pain had interfered with the following activities in the past week: general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work (including housework), relations with other people, sleep and enjoyment of life. Based on feedback from subjects in previous studies of pain, an eighth item was added to assess the extent to which pain interferes with one’s ability to take care of others. A mean of the eight items was used in analysis. Internal consistency of this scale has been very good (e.g. Ward et al., 1998) and was excellent in the present study (alpha = .95).

Well-being

Well-being was assessed with the Quality of Life Index-Cancer Version (QLI-CV) (Ferrans, 1990). The QLI-CV assesses patients’ perceptions of quality of life in four domains -- functioning, socioeconomic, psychological, and family. For each of the 34 items in the scale, the subject rates from 1 to 6 both the importance of, and their satisfaction with, this aspect of life. A total score was calculated by weighting each satisfaction response by each importance response yielding an adjusted score with a possible range of 0-30. The QLI-CV has been used in numerous studies and has demonstrated internal consistency (alpha = .86 to .98 for the total scale), stability (r = .87 over a two-week interval), content validity, and construct validity (demonstrated by factor analysis) (Bliley & Ferrans, 1993).

Procedure

This study was conducted in two outpatient oncology clinics in Wisconsin, one in Madison and the other in Milwaukee. IRB approval was obtained at both sites. In each clinic, late each afternoon, nurses reviewed lists of patients who were coming to clinic the next day to identify those who met eligibility criteria. When eligible patients arrived for their appointments, the receptionist in the oncology clinic asked if they were interested in learning more about the study. Names of interested persons were passed on to a research nurse employed by the study. This nurse explained the study, screened for the presence of pain (1 or greater on a 0 to 10 scale), obtained consent and made an appointment to meet with the subject at his/her next clinic visit (usually one to three weeks later). One or two days prior to the appointment, the research nurse telephoned to remind the subject to complete the baseline measures. At the appointment, randomization envelopes were opened, and subjects were informed of the condition to which they had been randomized and the intervention (SEI versus RIDcancerPain) was delivered. Intervention sessions were conducted in a private room adjacent to the clinic. The interventions were provided by masters-prepared nurses who were specialists in cancer nursing. Sessions were audio taped for quality control; 30% of the tapes were coded to ascertain fidelity to the 5 steps of the Representational Approach and 100% of the tapes showed that all 5 steps had been addressed.

T2 and T3 measures were mailed to subjects one week before they were supposed to complete them. Self-addressed stamped envelopes were enclosed for their return. Subjects were given a small reimbursement for their time and effort ($10.00) after each of the three sets of measures (T1, T2 and T3) they completed for a total of $30.

Results

Descriptive information for baseline variables

At baseline (T1), the 176 subjects had a mean (SD) BPIseverity score of 2.83 (2.05) with a range of 0 to 9. They were experiencing a moderate amount of pain interference with life activities (M = 3.75, SD = 2.71), with a range of 0 to 10. Their barriers scores were low, with a mean (SD) of 1.50 (0.74), and a range of 0.13 to 3.50. Based on the PMI, 58 subjects had inadequately managed pain at baseline (T1).

Dropouts were compared to those who stayed on study. A dropout is a subject who completed the intervention but then dropped before completing both the Time 2 and Time 3 data collection points. If a subject competed only baseline measures and one of the two follow up data collection points, they were still included in analyses. Those who dropped (n=26) had significantly higher baseline (T1) pain severity and pain interference with life activities compared to those who stayed on study (n=150) (see Table 2). The number dropping did not differ between the RIDcancerPain group (n=13) and the SEl group (n=13). There were no differences in demographic or disease variables between those who dropped from RIDcancerPain versus from SEI.

Table 2. Mean (SD) of Baseline Variables by Completion Status (N= 176).

| Those who completed baseline only (n=26) |

Those who completed baseline & at least one post measure (n=150) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (possible range) | M | SD | M | SD | t | p |

| Barriers (0-5) | 1.66 | 0.76 | 1.47 | 0.73 | -1.197 | .233 |

| BPIseverity (0-10) | 4.17 | 2.09 | 2.60 | 1.97 | -3.662 | .000 |

| Usual Severity (0-3) | 1.83 | 0.76 | 1.42 | 0.78 | -2.419 | .017 |

| Interference (0-10) | 4.94 | 2.66 | 3.54 | 2.67 | -2.472 | .014 |

| Well being (0-30) | 16.82 | 4.82 | 18.77 | 5.14 | 1.737 | .084 |

Hypothesis testing

To test for both initial and delayed impact of the intervention, separate analyses were conducted to evaluate changes between T1 and T2, and between T1 and T3. Such analyses were conducted for coping (PMI categorization), beliefs (barriers), BPIseverity, Usual Severity, pain interference, and well-being. Because data from two time-points were necessary to compute the change scores, the number of subjects available for each of these analyses varies from N=129 (Well-Being T1-T3) to N=144 (Pain Interference T1-T3) and therefore degrees of freedom vary slightly. These are not intent to treat analyses, but rather analyses of those still on study at T2 or at T3.

Test of intervention effects on coping (PMI)

Because it was expected that the PMI scores would not be normally distributed, a 2 (RIDcancerPain v. SEI) × 2 (male v. female) nonparametric aligned rank analysis of covariance was conducted (Harwell & Serlin, 1988), with gender nested within treatment, and with three covariates - age, baseline PMI score and minority status nested within gender. The percentage of subjects in RIDcancerPain with acceptable PMI scores at T1, T2, and T3 was 66.7%, 70.3% and 64.7%, respectively. The percentage of subjects in SEI with acceptable PMI scores at those time points was 66.7%, 60.0%, and 70.3%. The analysis revealed no main effect for RIDcancerPain versus SEI, nor was there a differential effect by gender.

Test of intervention effects on remaining variables

For remaining analyses, parametric ANCOVAs were conducted to evaluate changes between T1 and T2, and between T1 and T3. T1-T2 and T1-T3 change scores were computed for each dependent variable by subtracting the later score from the earlier score, so that a negative change score indicated that the value of the variable was higher on the later occasion than it had been at baseline. For beliefs (barriers), BPIseverity, Usual Severity, and Pain Interference, an increase (a negative change score) is an undesired outcome, while for well-being an increase is a desired outcome. Each ANCOVA was a 2 (RIDcancerPain v. SEI) × 2 (male v. female), with gender nested within treatment, and three covariates -- age, baseline (T1) score of the dependent variable being tested, and minority status nested within gender. The ANCOVA of change scores (e.g. T1-T2), with T1 scores as a covariate, yields covariate-adjusted means that are corrected for regression to the mean (Laird, 1983). The values reported in the text (MA) are covariate-adjusted change scores, while values in Table 3 are not adjusted.

Table 3. Mean (SD) Value of Outcome and Mediation Variables at Baseline (T1), T2, and T3 by Group.

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (range) | SEI | RIDPAIN | SEI | RIDPAIN | SEI | RIDPAIN |

| (n=84) | (n=92) | (n=68) | (n=76) | (n=66) | (n=70) | |

| Barriers (0-5) | 1.45 (0.71) | 1.55 (0.77) | 1.17 (0.78) | 0.99 (0.67) | 0.98 (0.79) | 1.01 (0.78) |

| BPIseverity (0-10) | 3.05 (2.11) | 2.63 (1.99) | 3.84 (2.31) | 3.85 (2.51) | 4.04 (2.53) | 3.45 (2.32) |

| Usual Severity (0-3) | 1.52 (0.80) | 1.43 (0.78) | 1.63 (0.74) | 1.41 (0.84) | 1.47 (0.77) | 1.39 (0.75) |

| Interference (0-10) | 3.75 (2.62) | 3.75 (2.80) | 4.09 (2.48) | 3.91 (2.82) | 4.02 (2.64) | 3.76 (2.72) |

| QOL (0-30) | 18.09 (4.96) | 18.87 (5.29) | 18.73 (4.68) | 18.69 (5.73) | 18.33 (5.05) | 18.85 (5.64) |

Note. SEI = Standard Educational Information. RIDPAIN = A Representational Intervention to Decrease Pain.

Because tests were conducted for both the T1 to T2 and the T1 to T3 changes, Type I error rate was controlled using the Holm (1979) sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. For each dependent measure, the more significant of the two change scores ANCOVAs was tested for significance using an assigned Type I error rate of .025. If this result was not significant, then both change scores were reported as non-significant. If the result was significant, the remaining change score ANCOVA was tested using an assigned Type 1 error rate of .05. For the investigation of the main effect of intervention, the tests were one-tailed, whereas tests of the gender effects were two-tailed.

Beliefs about analgesic use

As hypothesized, the ANCOVA for T1 to T2 change in barriers revealed main effects for intervention group. Subjects in RIDcancerPain showed greater decreases in barriers (MA = 0.49, SE = 0. 10) than those in SEI (MA = 0.08, SE=0.10), [F(1,129) = 8.236, p(one-tailed) = .0025] with an effect size of d = 0.7651. Changes in barriers scores for women and men did not differ significantly in RIDcancerPain, while men in SEI (MA =-.170, SE=.143) did worse than women in SEI (MA =.336, SE=.126) [F (1,129)=6.99, p=0.009)] with an effect size of d=0.9632.

The ANCOVA for T1 to T3 changes in barriers scores also revealed main effects for intervention group. Subjects in RIDcancerPain again showed greater decreases in barriers (MA = 0.45, SE = 0.13) than those in SEI (MA = -0.03, SE = 0.17) [F(1,122) = 4.952, p (one-tailed) = .014] with an effect size of d = 0.7885. Men and women faired similarly in both groups.

Pain severity

Contrary to our hypothesis, neither the T1 to T2 nor the T1 to T3 changes in BPI severity score ANCOVAs revealed any main effects for intervention, nor were there any main effects for intervention for T1 to T2 change in Usual Severity. On the other hand, consistent with our hypothesis, the ANCOVA for T1 to T3 Usual Severity revealed a main effect for group [F(1,126) = 5.852, p (one-tailed) = .0085], with those in RIDcancerPain experiencing more decrease in Usual Severity (MA = 0.14, SE = 0.15) than those in SEI (MA = -0.38, SE = 0.16), with an effect size of d=0.7448. Women and men did similarly in RIDcancerPain and SEI.

Pain interference, well-being

Contrary to our hypotheses, neither the ANCOVA for T1 to T2 change or the T1 to T3 change in pain interference or in well-being revealed any overall intervention effects nor any differential effects by gender.

Test of mediation

The tests of mediation were planned according to the method suggested by Cohen and Cohen (1983) and investigated by Serlin, Jacobs, and Franke (1995). In this method, a variable is declared to be a mediator if the two indirect paths, one from the independent variable to the mediator and the other from the mediator to the dependent variable, are found to be statistically significant when each path is tested at the nominal Type I error rate. The overall Type I error rate was split among the three possible mediating scenarios: 1) Change in Coping (PMI) or Barriers scores from Time 1 to Time 2 would serve as a mediator between intervention and changes in outcomes from Time 1 to Time 2, 2) change in PMI or Barriers scores from Time 1 to Time 2 would mediate changes in outcomes from Time 1 to Time 3, or 3) changes in PMI or Barriers scores from Time 1 to Time 3 would serve as a mediator between intervention and changes in outcome from Time 1 to Time 3. Each of the indirect paths was tested on a directional basis.

The only mediator that was tested was Barriers scores because the intervention did not have an effect on PMI. The path from intervention to change in Barriers scores from Time 1 to Time 3 was previously reported to be significant [F(1,122) = 4.952, p (one-tailed) = .014]. To test the path from the change in Barriers scores from Time 1 to Time 3 to changes in Usual Severity from Time 1 to Time 3, we used an ANCOVA model. As in previous analyses, the ANCOVA was a 2 (RIDcancerPain v. SEI) × 2 (male v. female), with gender nested within treatment, and three covariates -- age, baseline (T1) Usual Severity, and minority status nested within gender. The partial regression coefficient relating change in Usual Severity to change in Barriers scores was significant [F(1,120) = 8.593, p (one-tailed) = .002]. Therefore, a change in Barriers scores from Time 1 to Time 3 is a mediator between intervention and changes in Usual Severity from Time 1 to Time 3. On the other hand, similarly conducted analyses revealed that change in Barriers from Time 1 to Time 2 was not a mediator of change in Usual Severity.

Discussion

The major findings in this study are that the RIDcancerPain intervention had an effect on some, but not all, outcomes. The first hypothesis, that subjects receiving RIDcancerPain would show greater change from before to after intervention with respect to beliefs, coping, pain severity, pain interference with life and overall well being compared to those receiving a Standardized Educational Intervention, was partially supported. Patients receiving RIDcancerPain showed greater changes from before to after intervention than those receiving SEI with respect to beliefs and some measures of pain severity. On the other hand, our hypothesis that RIDcancerPain intervention would have an effect on coping (analgesic use), pain interference and overall well-being was not supported.

The second hypothesis that the effects of RIDcancerPain on pain severity, pain interference and overall well being would be mediated by changes in beliefs and coping from pre to post intervention was also partially supported. Coping did not function as a mediator. Beliefs mediated the long-term effects on usual pain severity but not the short-term effects, suggesting that subjects needed more than one month to integrate the new knowledge into their mental representations. On the other hand, the composition of the sample at time 3 could have been different enough to reveal relationships that were not seen at time 2.

Despite the fact that barriers scores were low in this sample before the intervention was provided, barriers were lower at completion of the study and there was a significant difference between the intervention groups. Furthermore, these changes in barriers mediated the effects of the intervention on the outcomes that changed as a result of the RIDcancerPain intervention. This supports the importance of addressing patient-related barriers in an attempt to improve pain management.

The effects of RIDcancerPain were consistent across gender, but the effects of the SEI were not. Men did worse than women in the SEI group. The efficacy of the representation intervention across gender supports that it is more useful than is a standard educational approach. This may be due to the fact that in RIDcancerPain the education is individualized, while the SEI is delivered in exactly the same manner and the same information is provided to all, regardless of their prior knowledge or educational needs. It seems that addressing patient’s representations about their cancer pain is useful to identify issues pertinent to the patient, thereby setting the stage for addressing concerns in a highly contextual manner. The intervention is highly individualized to the patient’s needs and requires an active involvement of the patient. It is imperative that testing of this intervention be conducted with more robust sample sizes of minority subjects. Such testing is vitally important because studies have shown that minorities experience less adequate pain management compared to Caucasians (e.g., see Cleeland et al., 1997).

RIDcancerPain did not have an effect on several of the outcomes. It did not have an impact on pain severity measured with the BPI, pain interference or well-being. The measures used in this study may be a limiting factor in being able to detect such changes. All measures are based on patients’ retrospective self-reports of pain and well being in the past week, as opposed to measures collected in real time that would not depend on recall. Further, these measures were only administered one and two months after the intervention, limiting our ability to track potential changes over longer periods of time. One could also question how reasonable it is to have expected the intervention to have an impact on all domains of quality of life (as measured by the QLI-CV). In retrospect, it seems that this was an overly ambitious expectation. Another limitation of this study is the fact that subjects were eligible to participate in the study if they had a pain intensity of one or more on a scale from 0 to 10 at the time of recruitment. Therefore, a number of subjects had low levels of pain before receiving the intervention, leaving limited room for improvement. Further, because of attrition, mostly due to illness progression and death, those patients that could have benefited the most from an intervention to improve pain management may, in fact, be the patients who were unable to complete the study.

The lack of difference between intervention groups in some of the outcome measures could partially be explained by the fact that the SEI was arguably above and beyond what would be considered usual care. All patients in SEI were provided with an educational booklet with up to date information about analgesics, importance of communicating pain with health care professionals, and side effect management. In addition, patients had the opportunity to ask a research nurse questions about the content of the booklet.

The RIDcancerPain intervention itself is limited in that it only provides one patient contact, and in the case of pain, which is a multifaceted and complicated clinical problem, one session may be inadequate to incorporate changes in beliefs into action and thereby impact pain-related outcomes. The possible benefits of additional sessions would need to be weighed against the additional costs that would be incurred. Cost benefit and cost effectiveness analyses of the intervention should be considered.

Even if improvements occurred over time in pain management practices, this would be difficult to detect with the measure we used to evaluate coping (analgesic use). As noted before, coping did not mediate the effect of the intervention on the outcome of usual pain-severity, an outcome that did change in response to the RIDcancerPain intervention. An explanation for this lack of effect could be limitations of the Pain Management Index. Firstly, although it is not inconsistent with common conceptualizations of coping (e.g., Leventhal, Nerenz, & Steele, 1984), the PMI constitutes a very narrow operationalization of this concept in that it focuses on only one strategy, analgesic use. On the other hand, this facet of coping is precisely the target of the intervention we tested. Nonetheless, in future work, it would be useful to consider using additional measures of coping strategies. Secondly, the PMI provides a crude measure of analgesic use based on which type of drug is used by the patient, but it does not take into account the dosage of the medication or how it is used (e.g., around the clock or PRN). Therefore, we had no means to capture changes in dosage or frequency of analgesic use, failings shared by available approaches to assessing analgesic use (de Wit, van Dam, Abu-Saad, Loonstra, Zandbelt, van Burren, et al.,1999).

In conclusion, while this theoretically strong intervention did not have all the effects that were hypothesized it is a promising approach to improving pain management. It is evident, however, that the intervention could be strengthened in a number of ways, for example by providing additional sessions to support the patient while making changes in their pain management practices.

Contributor Information

Sandra Ward, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Heidi Donovan, University of Pittsburgh.

Sigridur Gunnarsdottir, University of Iceland.

Ronald C. Serlin, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Gary R. Shapiro, Johns Hopkins University

Susan Hughes, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

References

- Anderson K, Syrjala K, Cleeland C. How to assess cancer pain. In: Turk D, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 579–600. [Google Scholar]

- Bliley A, Ferrans C. Quality of life after angioplasty. Heart & Lung. 1993;22(3):193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W, Passik S, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Smith M, Kaim M, et al. Patient-related barriers to pain management in ambulatory AIDS patients. Pain. 1998;76:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland C, Gonin R, Baez L, Loehrer P, Pandya K, The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127:813–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotfelter C. The effect of an educational intervention on decreasing pain intensity in elderly people with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1999;26:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, N J: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Daut R, Cleeland C, Flanery R. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983;17:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit R, van Dam F, Abu-Saad HH, Loonstra S, Zandbelt L, van Buuren A, et al. Empirical evaluation of commonly used measures to evaluate pain treatment in cancer patients with chronic pain. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17(4):1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit R, van Dam F, Zandbelt L, van Buuren A, van der Heijden K, Leenhouts G, et al. A pain education program for chronic cancer pain patients: Follow-up results from a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 1997;73(1):55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan H, Ward S. A representational approach to patient education. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans C. Development of a quality of life index for patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1990;17(Suppl):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Pellino T, Miaskowski C, Adams J, Paice J, Laferriere D, et al. A 10-year review of quality improvement monitoring in pain management: Recommendations for standardized outcome measures. Pain Management Nursing. 2002;3:116–130. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2002.127570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarsdottir S, Donovan H, Serlin R, Voge C, Ward S. Patient-related barriers to pain management: The barriers questionnaire II (BQ-II) Pain. 2002;99:385–396. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwell MR, Serlin RC. An empirical study of a proposed test of nonparametric analysis of covariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;104:268–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins R. The role of the patient in the management of post-surgical pain. Psychological Health. 1997;12(4):565–577. [Google Scholar]

- Hewson PW, Thorley NR. The conditions of conceptual change in the classroom. International Journal of Science and Education. 1989;11:541–553. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Laird N. Further comparative analyses of pretest-posttest research designs. American Statistician. 1983;37:329–330. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M. The active side of illness cognition. In: Skelton J, Croyle R, editors. Mental representation in health and illness. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1991. pp. 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Johnson J. Laboratory and field experimentation: Development of a theory of self-regulation. In: Wooldridge P, Schmitt M, Skipper J, Leonard R, editors. Behavioral science & nursing theory. Mosby; St. Louis: 1984. pp. 189–262. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Nerenz D, Steele D. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor S, Singer J, editors. A Handbook of Psychology and Health, Vol. IV: Social Psychological Aspects of Health. Erlbaum; New Jersey: 1984. pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, West C, Paul S, Tripathy D, Koo P, et al. Lack of adherence with the analgesic regimen: A significant barrier to effective cancer pain management. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:4275–4279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J, Kravitz R, Kaplan S, Meyers F. Individualized patient education and coaching to improve pain control among cancer outpatients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:2206–2212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer B, Levy M, Keintz M, Fox L, Engstrom P, McElwee N. Enhancing cancer pain control regimens through patient education. Patient Education and Counseling. 1987;10:267–277. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(87)90128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner GJ, Strike KA, Hewson PW, Gertzog WA. Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education. 1982;66:211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Serlin RC, Jacobs V, Franke T. Testing for mediation; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association; San Francisco. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood G, Adams-McNeil J, Starck P, Nieto B, Thompson C. Qualitative assessment of hospitalized patients’ satisfaction with pain management. Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:486–495. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200012)23:6<486::AID-NUR7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E, Weiss S. Non-pharmacological interventions with chronic cancer pain in adults. Cancer Control. 2000;7:157–164. doi: 10.1177/107327480000700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S, Carlson-Dakes K, Hughes S, Kwekkeboom K,, Donovan H. The impact on quality of life of patient-related barriers to pain management. Research in Nursing & Health. 1998;21:405–413. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199810)21:5<405::aid-nur4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward S, Goldberg N, Miller-McCauley V, Mueller C, Nolan A, Pawlik-Plank D, et al. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain. Pain. 1993;52:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90165-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells N. Pain intensity and pain interference in hospitalized patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2000;27:985–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells N, Hepworth JT, Murphy BA, Wujcik D, Johnson R. Improving pain management through patient and family education. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25(4):344–356. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00685-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelman D, Cleeland C, Howland E. Factors in appropriate pharmacologic management of cancer pain: A cross-institutional investigation. Pain. 1987:S136. [Google Scholar]