Abstract

Cryptococcal meningitis is a rare complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The nonspecific neurologic findings associated with this infection delays accurate diagnosis because initial neuropsychiatric manifestations of SLE are in instances indistinguishable from that of crytococcal meningitis. We report a case of cryptococcal meningitis presenting with unilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy in a male patient with SLE, which was successfully treated with antifungal agents.

Keywords: Lupus Erythematosus, Systemic; Meningitis, Cryptococcal; Abducens Nerve Palsy

INTRODUCTION

Infection still remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Patients with SLE are well known to have increased risk for not only bacterial but other infections such as viral, fungal, and protozoa (1, 2). Susceptibility to infection may be due to intrinsic abnormalities in the components constituting the immune system such as complements, mannose binding lectin, phagocytic cells, and T cells. The use of immuosuppressive agents, particularly steroids and cyclophosphamide, are the strongest extrinsic risk factors contributing to infection (3).

Cryptococcal meningitis is a common opportunistic infection in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients and occurs not only in patients with other forms of immunosuppression but also in immunocompetent individuals (4). The mortality rate remains high in both human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated cases and in non-HIV associated cases (4, 5). However, crytococcal meningitis is not a common complication of SLE (6).

We describe a case of cryptococcal meningitis that presented with isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy in a male patient with SLE, which was successfully treated with antifungal agents. Most reports of ophthalmoplegia in patients with SLE were related to the disease manifestations of SLE (7-10). To our knowledge, isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy as a presenting sign of crytococcal meningitis in an SLE patient has not been reported.

CASE REPORT

A 32-yr-old man was admitted to Kang-Nam St. Mary's Hospital in September 2006 with complaints of double vision and mild headache that had persisted for three days. In 1993, he had been diagnosed with SLE based on the presence of malar rash, photosensitivity, thrombocytopenia, positive antinuclear antibody, and positive anti-double stranded DNA antibody. In November 1994, he was diagnosed with lupus nephritis (WHO classification IV) and underwent a series of intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapies (total 13 times; total cumulative dose, 9,750 mg). Azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil were tried to maintain renal remission. He was treated with 24 mg of deflazacort and 1,000 mg of mycophenolate mofetil during the last one year before admission.

On admission, his body temperature was 37.7℃. Blood pressure, pulse rate, and respiratory rate were normal. He did not complain of nausea, vomiting, or chilling. The remaining general examination was unremarkable, and there were no signs indicative of meningeal irritation. His mental status was alert and no abnormalities were detected on neurologic or fundoscopic examination. On ophthalmic examination, he was found to have right sixth cranial nerve palsy without retinal abnormalities. Initial laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10,350/µL (neutrophil: 82.2%), a platelet count of 123,000/µL, a serum creatinine level of 2.66 mg/dL, and slight hypocomplementemia (C3: 77.7 mg/dL). Other laboratory findings were unremarkable. Plain radiography of the chest was normal. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no abnormal findings. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a pressure of 21 mmHg, a protein level of 179 mg/dL, and a glucose level of 73 mg/dL (serum glucose, 91 mg/dL). Only 2 WBC/µL were noted. CSF studies for bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and syphilis were all negative. Cryptococcal antigen test by latex agglutination and indian ink stain were both negative.

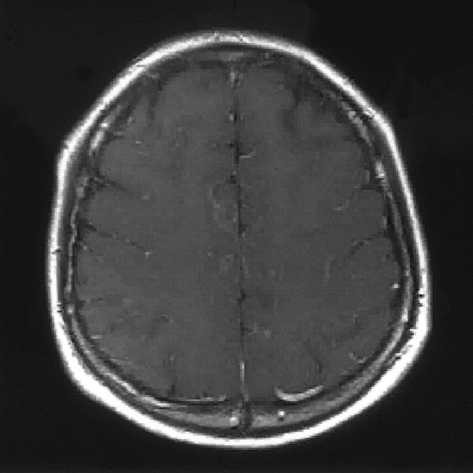

Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued and empirical antibiotics (ceftriaxone) were administered without lowering the steroid dosage due to difficulties in differentiation between infection and lupus disease activity at the time of admission. On the fourth hospital day, he complained of severe headache and nausea. His body temperature increased to 39℃ and serum C-reactive protein elevated. CSF and blood cultures performed on the first hospital day revealed growth of Cryptococcus neoformans. Subsequently, amphotericin B and flucytosine were administered immediately, and lumbar puncture for a second CSF analysis was performed. The second CSF analysis done on the fourth hospital day revealed markedly elevated pressures of 42 mmHg and increased pleocytosis of 280/µL. Both crytococcal antigen test and indian ink stain were positive. The second brain MRI done on the same day showed accentuation of leptomeningeal contrast enhancement along the sulci of both cerebral hemisphere, findings suggestive of meningitis (Fig. 1). Mannitol was added to control the increased intracranial pressure. After 3 weeks of amphotericin B and flucytosine, all symptoms except diplopia subsided. Subsequent blood and CSF cultures were negative for fungal growth. He was discharged and treated with oral fluconazole for an additional 8 weeks. Currently, he has recovered completely from esotropia that had been related to right sixth cranial nerve palsy.

Fig. 1.

The second brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) done on the fourth hospital day shows accentuation of leptomeningeal contrast enhancement along the sulci of both cerebral hemisphere in T1-weighted image, findings suggestive of meningitis.

DISCUSSION

Cryptococcal meningitis is a common opportunistic infection in patients with late stage HIV infection (4). In parts of sub-Saharan Africa where HIV infections are prevalent, cryptococcal meningitis is now the leading cause of communityacquired meningitis, ahead of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitides (11, 12). It also occurs in other immunocompromised patients and in apparently immunocompetent individuals (4). Since clinical features are often non-specific without neurologic deficit, cryptococcal meningitis should be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic or subacute meningoencephalitis (4, 6).

Cryptococcal meningitis is an uncommon complication of SLE (6, 13). There have been various reports that describe cryptococcal meningitis in SLE patients (6, 13-16). In 1992, Zimmermann et al. described 2 cases and reviewed 24 previous cases of cryptococcal meningitis occurring in SLE patients (6). The outcome without antifungal agents was poor. On the contrary, among 20 patients treated with amphotericin B, 8 patients died. They demonstrated that the nonspecific neurologic findings associated with this infection are often a cause of misdiagnosis as a neuropsychiatric manifestation of lupus, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and implementation of effective antifungal therapy to ultimately improve the prognosis of cryptococcal meningitis in SLE patients. Our case also showed that cryptococcal meningitis could not be fully differentiated from central nervous system (CNS) lupus at the time of initial presentation. In 2005, Hung et al. reported 17 cases of CNS infections occurring in patients with SLE (13). Among the 17 cases, 10 cases were due to cryptococcal meningitis, indicating a major role of cryptococcal meningitis in CNS infection in patients with SLE albeit being rare.

In our case, the initial presenting symptom was horizontal diplopia caused by right sixth cranial nerve palsy. Sixth cranial nerve palsy is the most common form of extraocular muscle palsy. Causes of acquired sixth nerve palsy differ depending on the age of the patient. Common causes in young adults are a CNS mass, demyelinating disease, or idiopathic causes (17). Cryptococcal meningitis is an uncommon cause of sixth cranial nerve palsy, and only a few cases of sixth cranial nerve palsy associated with cryptococcal meningitis have been reported irrespective of SLE (18). Moreover, there have been a few cases of ophthalmoplegia occurring in SLE patients (7-10). However, all of them were associated with the disease manifestations of SLE.

In summary, we report a case of cryptococcal meningitis presenting with unilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy in a male patient with SLE, which was successfully treated with antifungal agents. We recommend a clinical awareness for the possibility of crytococcal meningitis in SLE patients whose presenting sign is isolated cranial nerve palsy without other neurologic manifestations. If the diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis is delayed, the fatality would be high. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first case of cryptococcal meningitis presenting with unilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy in a patient with SLE.

References

- 1.Gladman DD, Hussain F, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. The nature and outcome of infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2002;11:234–239. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu170oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellmann DB, Petri M, Whiting-O'Keefe Q. Fatal infections in systemic lupus erythematosus: the role of opportunistic organisms. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987;66:341–348. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang I, Park SH. Infectious complications in SLE after immunosuppressive therapies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:528–534. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bicanic T, Harrison TS. Cryptococcal meningitis. Br Med Bull. 2005;72:99–118. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih CC, Chen YC, Chang SC, Luh KT, Hsieh WC. Cryptococcal meningitis in non-HIV-infected patients. QJM. 2000;93:245–251. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann B, 3rd, Spiegel M, Lally EV. Cryptococcal meningitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;22:18–24. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(92)90044-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedwick LA, Burde RM. Isolated sixth nerve palsy as initial manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. A case report. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1983;3:109–110. doi: 10.3109/01658108309009726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman AS, Folkert V, Khan GA. Recurrence of systemic lupus erythematosus in a hemodialysis patient presenting as a unilateral abducens nerve palsy. Clin Nephrol. 1995;44:338–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan CN, Li E, Lai FM, Pang JA. An unusual case of systemic lupus erythematosus with isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy, fulminant acute pneumonitis, and pulmonary amyloidosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:236–239. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenstein ED, Sobelman J, Kramer N. Isolated, pupil-sparing third nerve palsy as initial manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1989;9:285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakim JG, Gangaidzo IT, Heyderman RS, Mielke J, Mushangi E, Taziwa A, Robertson VJ, Musvaire P, Mason PR. Impact of HIV infection on meningitis in Harare, Zimbabwe: a prospective study of 406 predominantly adult patients. AIDS. 2000;14:1401–1407. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon SB, Walsh AL, Chaponda M, Gordon MA, Soko D, Mbwvinji M, Molyneux ME, Read RC. Bacterial meningitis in Malawian adults: pneumococcal disease is common, severe, and seasonal. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:53–57. doi: 10.1086/313910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung JJ, Ou LS, Lee WI, Huang JL. Central nervous system infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huston KK, Gelber AC. Simultaneous presentation of cryptococcal meningitis and lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:2501–2502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mok CC, Lau CS, Yuen KY. Cryptococcal meningitis presenting concurrently with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16:169–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liou J, Chiu C, Tseng C, Chi C, Fu L. Cryptococcal meningitis in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Mycoses. 2003;46:153–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin D. Differential diagnosis and management of acquired sixth cranial nerve palsy. Optometry. 2006;77:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchetee P. Cryptococcal meningitis in immunocompetent patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998;46:617–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]