Abstract

To investigate myosin II function in cell movement within a cell mass, we imaged green fluorescent protein-myosin heavy chain (GFP-MHC) cells moving within the tight mound of Dictyostelium discoideum. In the posterior cortex of cells undergoing rotational motion around the center of the mound, GFP-MHC cyclically formed a “C,” which converted to a spot as the cell retracted its rear. Consistent with an important role for myosin in rotation, cells failed to rotate when they lacked the myosin II heavy chain (MHC−) or when they contained predominantly monomeric myosin II (3xAsp). In cells lacking the myosin II regulatory light chain (RLC−), rotation was impaired and eventually ceased. These rotational defects reflect a mechanical problem in the 3xAsp and RLC− cells, because these mutants exhibited proper rotational guidance cues. MHC− cells exhibited disorganized and erratic rotational guidance cues, suggesting a requirement for the MHC in organizing these signals. However, the MHC− cells also exhibited mechanical defects in rotation, because they still moved aberrantly when seeded into wild-type mounds with proper rotational guidance cues. The mechanical defects in rotation may be mediated by the C-to-spot, because RLC− cells exhibited a defective C-to-spot, including a slower C-to-spot transition, consistent with this mutant’s slower rotational velocity.

INTRODUCTION

Cell migration within a three-dimensional (3D) cell mass is common to many biological processes, such as embryonic development, wound healing, and tumor cell invasion. Despite its importance, the mechanisms of locomotion within such an environment are poorly understood. This problem is amenable to study in the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum (Kay and Insall, 1994) where a variety of molecularly generated mutants are available, and where cells undergo extensive rearrangements within a 3D cell mass called the mound.

Earlier studies have shown that normal cell movement within the mound requires myosin II. In mounds composed of myosin heavy chain–null cells (MHC−), directional motion is largely abolished, most cells merely jiggle in place (Eliott et al., 1993; Doolittle et al., 1995), and the mounds fail to proceed further in development (DeLozanne and Spudich, 1987; Knecht and Loomis, 1987; Manstein et al., 1989).

There are several possible explanations for the severe motility defects of MHC− cells in the mound. First, myosin II may be important for maintaining the rigidity that cells require to move on and around each other in the tightly packed 3D cell mass. Support for this view comes from mixing experiments in which a small percentage of MHC− cells were combined with normal cells and allowed to develop. In chimeric aggregation streams, the mutant cells appeared abnormally stretched and deformed, suggesting that they could not resist the traction forces of the surrounding, normal cells (Knecht and Shelden, 1995; Shelden and Knecht, 1995). Even isolated MHC− cells exhibit significant cell shape differences compared with normal cells (Shelden and Knecht, 1996; Wessels et al., 1988), further suggesting a role for myosin II in cell shape maintenance. The aberrant cell shapes in MHC− cells may be caused by a loss of cortical tension, because the mutant cells are less stiff than normal cells (Pasternak et al., 1989).

As a second possibility, myosin II may be involved in breaking adhesive bonds during cell locomotion within the mound (Doolittle et al., 1995; Knecht and Shelden, 1995). Adhesive forces between cells are thought to increase as the mound forms, thereby creating an environment where bond breaking becomes critical. Consistent with this possibility are the observations that MHC− cells cannot move on adhesive substrates, even though normal cells still can (Jay et al., 1995).

A third conceivable role for myosin II in mound motility is in chemotactic signaling. Within the mound, chemotactic signals in the form of cAMP waves are thought to be present and to play a role in directional cell motion (Siegert and Weijer, 1995; Rietdorf et al., 1996). In principle, if myosin II were in some way required for this signaling, then in a myosin II–null mound chemotactic guidance cues would be disrupted, thereby disrupting cell motion. However, previous work has shown that myosin II–null cells have a normal chemotactic response to cAMP, normal levels of cAMP receptors, and a normal rate of cAMP secretion (Peters et al., 1988). Thus, there is no evidence to date that myosin II plays a role in signaling.

To understand more about myosin II’s role in 3D motility, we have examined its distribution within moving cells in the mound, extended earlier mutant analyses of mound cell locomotion, and finally examined its effect on chemotactic signaling waves in the mound. We found that normal cells at a certain stage of mound development often displayed a characteristic distribution of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-myosin II in the cell posterior. As the rear retracted, GFP-myosin II condensed from a “C” to a spot at the posterior cell cortex. At this point in mound development, cells executed vigorous rotational motion that was adversely affected in three different myosin II mutants. One of these mutants, the regulatory light chain null (RLC−), exhibited an aberrant C-to-spot during its defective rotational motion, suggesting a further correlation between the myosin II pattern and cell locomotion. We hypothesize that the C-to-spot condensation represents an actomyosin contraction that retracts the cell rear by pulling in the cortex and/or by breaking adhesive bonds between neighboring cells and therefore is required for normal rotational motion in the mound. RLC− cells attempting to rotate also showed a significant reduction in the generalized cortical localization of myosin II, consistent with the hypothesis that myosin II provides cortical tension required for normal rotational motion. To our surprise, in the course of our studies, we have also found some influence of myosin II on signaling patterns in the mound, demonstrating that myosin II is in some way required for organization of these signaling patterns.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

The following D. discoideum cell lines were used: HS1 expressing GFP fused to the N terminus of MHC (referred to here as GFP-MHC), kindly provided by Drs. James Sabry and James Spudich (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) (Moores et al., 1996); HS1 (Ruppel et al., 1994), a derivative of JH10, as the MHC-null strain; JH10 (Hadwiger and Firtel, 1992), a derivative of KAx3, as a parent strain for HS1 and RLC−; pBIG-ASP (3xAsp) and its parent pBIG-WT, both derivatives of HS1, kindly provided by Dr. Thomas Egelhoff (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) (Egelhoff et al., 1993); and RLC−, a derivative of JH10, kindly provided by Dr. Rex Chisholm (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) (Chen et al., 1994). All cell lines were grown at 21°C in HL-5 medium (Spudich, 1982) in 100-mm-diameter plastic Petri plates. All motility studies were repeated on at least two independent clones of each mutant line. GFP-MHC, 3xAsp, and pBIG-WT were maintained with 10 μg/ml geneticin selection. JH10 requires 100 μg/ml thymidine for growth. Cells were starved by harvesting, centrifugation, and washing in phosphate buffer (5.7 mM K2HPO4, 17.0 mM KH2PO4, 2.0 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.2 mM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.34 mM dihydrostreptomycin sesquisulfate salt) (Clark et al., 1980; DeLozanne and Spudich, 1987).

Cell-labeling Procedure

After washing cells in phosphate buffer, we incubated them at ∼107 cells/ml in 0.1 mM 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After 20 min of incubation, cells were washed once in phosphate buffer, allowed to release dye for 10 min, washed twice in phosphate buffer, and then mixed with unlabeled cells such that labeled cells comprised 2–3% of the total cell population.

Microscopy

Mixtures of labeled and unlabeled cells were allowed to settle onto a dialysis membrane laid on a coverslip kept in a humid chamber. Imaging setup and collection were performed as described by Doolittle et al. (1995). We recorded images from a custom-modified Olympus Optical (Tokyo, Japan) IMT-2 inverted microscope with a scientific grade charge-coupled device camera cooled to −40°C.

Time-Lapse Two-dimensional Microscopy of GFP-MHC Cells.

GFP-MHC cells were imaged alone or by mixing with unlabeled cells of the wild-type control (pBIG-WT). Vegetative cells, aggregation fields, and various mound stages were imaged in the humid chamber described above. Depending on the magnification and resolution required for a particular experiment, we used one of the following lenses: an Olympus D Plan Apo UV 0.8 numerical aperture (NA)/20× oil immersion lens, a Leitz (Wetzlar, Germany) NPL Fluotar 1.3 NA/40× oil immersion lens, a Nikon (Garden City, NY) Plan Apo 1.4 NA/60× oil immersion lens, or an Olympus D Plan Apo UV 1.3 NA/100× oil immersion lens. An exposure time of 10–300 msec was used with a 50–95% neutral density filter in the light path of a 150-W xenon arc lamp. Two-dimensional (2D) images were acquired at 5-s to 5-min intervals, depending on the experiment.

Time-Lapse 3D Fluorescence Microscopy of Myosin II Mutants.

To determine 3D cell trajectories, we used 3D time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. Imaging was begun when the cells reached the appropriate developmental stage. We used an Olympus D Plan Apo UV 0.8 NA/20× oil immersion objective lens; x and y resolution of the charge-coupled device camera was 1.3 μm/pixel; focal plane position was set by a computer-controlled microstepping motor; and z step size was also 1.3 μm, thereby yielding comparable resolution in x, y, and z. Thirty-two or 64 focal planes were collected per time point. An exposure time of 50–200 msec/focal plane was used with a 50–95% neutral density filter in the light path of a 100-W mercury arc lamp or 150-W xenon arc lamp. 3D images were acquired at 2- to 5-min intervals. A typical experiment had 30 time points.

Dark-Field Microscopy.

2D dark-field wave images were collected as follows. The microscope was set up for differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging using the halogen lamp, polarizer, Wollaston prisms, and analyzer. The prism beyond the objective lens was set such that the image background was black. We used either an Olympus S Plan PL 0.3 NA/10× objective lens or an Olympus D Plan Apo UV 0.8 NA/20× oil immersion objective lens. Depending on the experiment, we used either a red emission filter or no emission filter. Exposure times of 10–50 msec were used, and images were acquired at 10- to 30-s intervals.

Cell Viability.

The following precautions were taken to ensure cell viability. First, after an imaging experiment, cell chambers were observed up to 1 d later to confirm that development proceeded properly. Second, the rate of development was compared in cell chambers on and off the microscope and found to be the same. Third, to reduce light exposure to a specimen, time points were spaced more widely, or 2D imaging was performed instead of 3D imaging. In either case, cell movements were consistent with those observed under increased light exposure. Finally, to verify that transitions in cell motile behavior were not due to imaging, data collection was sometimes started after the transition occurred to demonstrate that light exposure did not induce the transition.

Image Processing

Recorded 3D images were processed to reduce out-of-focus light by several different well-characterized restoration methods (Preza et al., 1992; Conchello and McNally, 1996). See Doolittle et al. (1995) and McNally et al. (1994) for a detailed discussion of these methods and their validation.

To better visualize dark-field waves, successive time-lapse images were subtracted. This produced brighter pixels where intensities differed and dimmer pixels where intensities were similar.

Quantification of Cell Motion

3D cell tracking was performed using an upgraded version of customized software (Awasthi et al., 1994).

For a quantitative analysis of cell trajectories, cell motion was divided into two broad categories: directional and nondirectional. A cell was considered directional if it moved in a linear or circular path for at least 30 min. Most directional cells could be further subclassified as radial or rotational. Radial motion was defined as movement greater than two cell diameters (∼20 μm) occurring within a 5-min period along radii running from the mound center to the mound edge. Rotational motion was defined as movement greater than two cell diameters occurring within a 5-min period along any circular arc centered about the mound’s center. A cell was considered nondirectional if, for at least 30 min, it failed to follow a persistent linear or circular path. Nondirectional motion was subdivided into two categories: random and jiggling. Random motion was defined as a cell that moved at least two cell diameters away within 5 min and eventually moved outside of a three-cell-diameter circular zone drawn around the cell at the first time point. Jiggling motion was defined as a cell that moved no more than one cell diameter away within 5 min and thereafter remained within a three-cell-diameter circular zone drawn around the cell at the first time point (i.e., stayed in that constrained location). For each cell line, motion statistics were generated for both loose and tight mounds. The result of motion analysis for each mound was the percentage of total trajectories in these four categories: rotation, radial, random, and jiggling.

Immunofluorescence of Myosin II

Immunofluorescence was performed on mounds using a modified version of a protocol by Eliott et al. (1991). Mounds on a dialysis membrane were fixed in methanol (with or without 1% formalin) at −20°C for 15–25 min. Some mounds had been previously submerged in liquid nitrogen for 10 s. Mounds were washed in PBS for 10–20 min or overnight. Mounds were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS for 30 min. After three 5-min washes in PBS, mounds were incubated for 2–4 h at room temperature with mAb M151 (5 μg/ml) specific for D. discoideum myosin II (Reines and Clarke, 1985). After a 5-min wash in PBS, mounds were blocked in 5% milk for 20–35 min. Then after three 5-min washes in PBS, mounds were incubated at room temperature for 0.5–3.5 h with a secondary antibody, either donkey anti-mouse dichlorotriazinyl amino fluorescein (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) diluted 1:200 or Oregon Green 488 goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (heavy- and light-chain) conjugate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted 1:250 or 1:500. Then mounds were washed in PBS three times for 10 min each.

Observation of the Cringe Response after cAMP Stimulation of Cells

Parental strain (JH10) and MHC-null (HS1) cells were starved in phosphate buffer for ∼16 h. Drops of cells were put in a humid chamber at a density such that individual cell shapes could be easily viewed. Before addition of cAMP, cells were imaged by DIC microscopy for at least 75 s to establish that active pseudopodia were present. Then a known volume of cAMP was added via pipette to one side of the field. Final cAMP concentrations ranged from 5 × 10−7 to 3 × 10−4 M. To view cell recovery after addition of cAMP, DIC imaging continued for 2–9 min at 2- to 5-s intervals.

Transformation Procedure

RLC− and JH10 cells were transformed with the GFP-MHC construct described by Moores et al. (1996) (kindly provided by Drs. James Sabry and James Spudich) using standard CaCl2 protocols (Nellen et al., 1987). Clones were selected and then maintained at 20 μg/ml geneticin.

RESULTS

GFP-Myosin II Exhibits a C-to-Spot during Rear Retraction

We imaged D. discoideum cells containing the well-characterized fusion of MHC to GFP. This GFP-MHC rescues all defects in MHC− cells and in biochemical assays exhibits both normal actin-activated ATPase activity and in vitro motility rate (Moores et al., 1996). We observed GFP-MHC cells in many developmental stages, including vegetative cells, starved amoebae on a substrate, streams, and mounds. We found that GFP-MHC often exhibited complex and dynamic patterns of distribution within moving cells. Many cells showed an enhancement of myosin staining at the cortex (Figures 1 and 2). At the tight mound stage of development, when cells have begun to rotate around the mound center, we discerned a prominent spatiotemporal pattern of GFP-MHC.

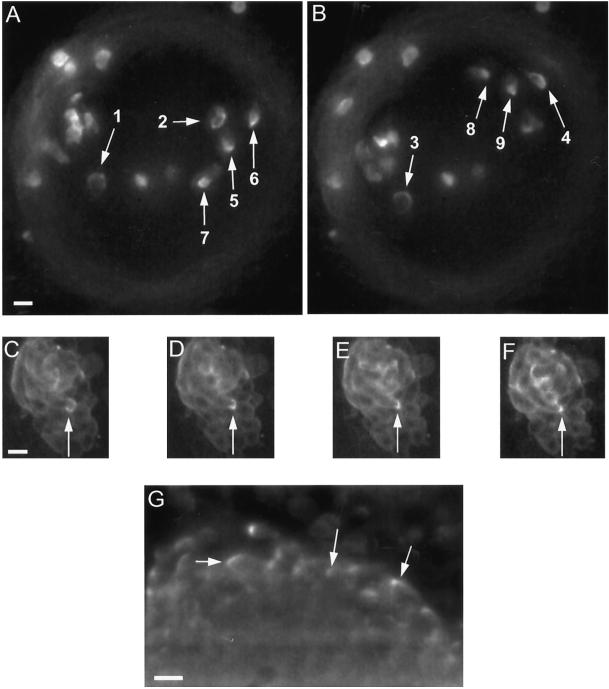

Figure 1.

Examples of the C-to-spot transition of myosin II at the cell rear. (A and B) Sampling of C-to-spot patterns in GFP-MHC cells seeded into a mound of unlabeled cells. In this mound, a number of cells undergoing counterclockwise rotation exhibit Cs (arrows 1–4), Cs condensing to a spot (arrows 5 and 6) and spots (arrows 7–9). Assignment of Cs and spots are based on movie data incorporating these images, and in each case showing the full transition from a C to a spot (See online movies or the author’s website as listed in ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.) Each view is a projection of three focal planes spanning a total depth of 20 μm. The time interval from A to B is 280 s. The mound edge is defined by the dim gray ring. (C–F) Sequence of the C-to-spot transition in an individual cell (arrows), showing the initial C (C), the C condensing to a spot (D and E), and the spot (F). Images are from the same focal plane obtained 100 s apart. This tight mound is composed entirely of GFP-MHC cells undergoing clockwise rotation. (G) Control demonstrating Cs and spot patterns in a mound fixed and stained for immunofluorescence using an anti-myosin II mAb. Shown is one focal plane slice from a 3D image stack that was deconvolved to reduce out-of-focus light. Bars, 10 μm.

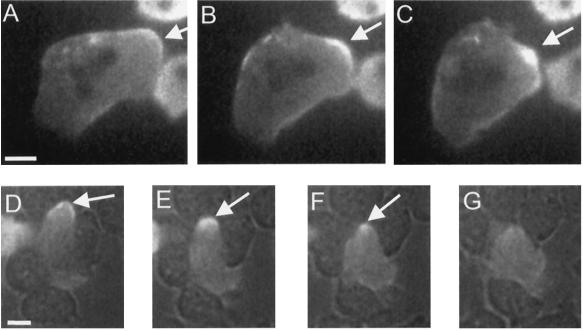

Figure 2.

Examples of the C-to-spot transition during pseudopod retraction and cell squeezing. (A–C) C condensing to a spot (arrows) in a pseudopod as it retracts in a starved GFP-MHC cell resting on a substrate. (Also see online movies, or the author’s web site listed in ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.) (A) C, 0 s; (B) condensing C, 35 s; (C) spot, 65 s. (A second pseudopod in the same cell is being retracted just below the spot marked by the arrow. This second pseudopod is in the process of condensing to a spot.) (D–F) C condensing to a spot as a starved cell squeezes between two neighbors. The image was obtained by simultaneous fluorescence and bright-field microscopy. A GFP-MHC–labeled cell is moving between several unlabeled adjacent cells. Arrows indicate the C at the cell posterior (D, 0 s) undergoing condensation (E, 23 s) to a spot (F, 39 s), which eventually disintegrates (G, 62 s). Bars, 5 μm.

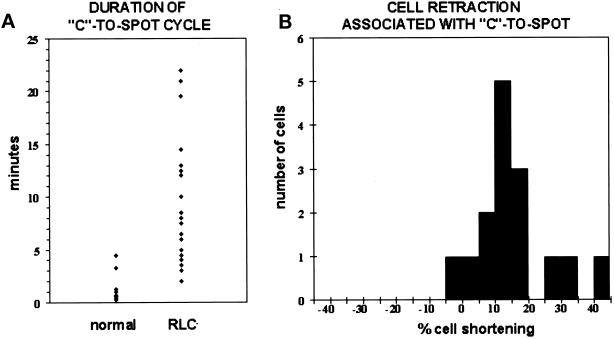

In rotating cells within the mound, GFP-MHC was often enhanced at the cell posterior in a cortical C, which then condensed into a spot during rear retraction (Figure 1, A–F). The spot then disintegrated, a new cortical C appeared, and the cycle repeated. Cycle time varied from 0.2 to 5 min (Figure 3A). Consistent with a possible role of the C-to-spot transition in rear retraction, we found that on average cells shortened by 15% as the C converted to a spot (n = 15 cells; Figure 3B). The GFP-MHC distribution patterns did not appear to be artifactual, because we observed similar patterns for native myosin II in mounds visualized by immunofluorescence with a myosin II antibody (Figure 1G).

Figure 3.

C-to-spot statistics. (A) The conversion from a C to a spot is on average slower in RLC− cells. Dots represent the duration of a C-to-spot conversion for a particular cell in the mound as measured from time-lapse images recorded at intervals ranging from 1 to 60 s, depending on the experiment. Only cells that remained in focus throughout the entire C-to-spot conversion were selected for these measurements. Duration of the C-to-spot was determined by measuring the time interval between the first appearance of a C through the condensation into a spot at the cell rear. Normal on the left represents nine GFP-MHC cells in five different mounds. RLC− on the right represents 23 RLC− cells with GFP-MHC in 10 different mounds. (B) The conversion of a C to a spot is normally associated with cell retraction. To determine percent cell shortening, cell length was measured at the beginning of a C and then at the end of the cycle when a full spot had formed. Percent shortening was calculated by subtracting the cell length at the spot stage from the cell length at the C stage and then normalizing this difference by cell length at the C stage. Negative values therefore represent an increase in cell length. Again, only cells that remained in focus throughout the entire C-to-spot conversion were selected for these measurements. Fifteen cells are represented in six different mounds; 14 of these cells shortened when a spot formed.

Rotating mound cells had the most prominent C-to-spot, but it could also be discerned in the following instances. The tips of retracting pseudopodia had a cortical C of myosin II, which condensed to a spot as retraction occurred (Figure 2, A–C). This was observed in at least 100 retracting pseudopodia. In contrast, in extending pseudopodia, there was no enhancement of fluorescence at the cortex but only a dim, diffuse fluorescence throughout the cytoplasm. C-to-spot transitions could also be observed in some aggregating cells and in cells squeezing between other cells on a substrate (Figure 2, D–G). In all cases, there was a strong correlation between retraction of a cell extension and a C-to-spot transition.

Myosin II Is Required for 3D Rotational Cell Motion

Because the myosin II C-to-spot was especially prominent in rotating cells, we asked whether myosin II was important for rotation. Using time-lapse 3D microscopy, a preliminary screen of myosin II mutants identified three mutants with obvious problems in rotational motion. These mutants were 1) a myosin II heavy chain null (MHC−), 2) a site-directed mutant that mimics heavy chain phosphorylation (3xAsp), and 3) a regulatory light chain null (RLC−). All three mutants arrest development at the mound stage. Each of these mutants was subjected to a more a careful analysis of motion in the mound.

Our previous studies had shown that individual MHC− cells moved poorly in mounds (Doolittle et al., 1995), but this analysis was done in an Ax2 background, which is a parental strain that does not exhibit vigorous rotational motion (Kellerman and McNally, 1999). When the MHC-null mutation was made in an Ax3 background, a parental strain that does normally rotate, Eliott et al. (1993) observed that rotational cell flows were abolished, but their technique did not permit examining the motion of individual mutant cells in the mound. To determine whether the MHC is required for rotation of individual cells, we examined MHC− cells in the same strain background (KAx3) as the GFP-MHC cells described above. In this KAx3 strain, cells rotate vigorously. When this strain carried the MHC knockout, rotation was abolished, and instead most cells merely jiggled in place (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Representative cell trajectories and motion statistics for parent strain and mutant cells. (A, C, E, and G) Trajectories from a representative tight mound from each strain. Arrowheads represent the location of a cell, and lines connect a cell’s position at successive time points. Time increases in the direction of the arrowheads from black to white. (B, D, F, and H) Schematics summarizing measurements of 3D motion for tight mounds in each strain. See MATERIALS AND METHODS for a definition of each motile category. Motion percentages were determined for each mound and then averaged over the set of mounds in each strain. Each symbol in the schematic reflects a 10% representation of that type of motion in the measured data. Exact percentages are given to the right. (A) Parent strain (JH10). Rotational motion is prominent. Arrowheads represent time points 5 min apart. (B) Average statistics for eight mounds of the parent strain calculated from a total of 400 cell trajectories. (C) MHC− (HS1). Jiggling motion is prominent, and arrowheads representing cell position at each time point are largely superimposed. Time points are 2.3 min apart. (D) Average statistics for 11 mounds of the MHC− calculated from a total of 439 cell trajectories. (E) 3xAsp. Jiggling motion is prominent, and arrowheads representing cell position at each time point are largely superimposed. Time points are 2.5 min apart. (F) Average statistics for four mounds of 3xAsp calculated from a total of 233 cells. (G) RLC−. Random and some rotational motion is evident. Arrowheads represent time points 5 min apart. (H) Average statistics for 22 mounds of RLC− calculated from a total of 1906 cells. Bar, 30 μm.

A quantitative analysis verified that the MHC is essential for cell rotation in the mound. Cell trajectories were classified into one of three categories—jiggling, random, or rotational—for both MHC− mounds (n = 487 trajectories) and for parent mounds (n = 535 trajectories). In tight mounds, 1% of MHC− trajectories could be classified as rotational (Figure 4D) compared with 80% in the parent (Figure 4, A and B). In contrast, most MHC− trajectories were categorized as jiggling.

In the second mutant examined, 3xAsp, the MHC phosphorylation sites are converted to aspartate residues, thereby inhibiting filament formation (Egelhoff et al., 1993). We found that in these 3xAsp cells, which form few if any filaments, rotation was abolished. In 3xAsp mounds (n = 528 trajectories), no cells rotated (Figure 4, E and F), whereas in the parent strain (pBIG-WT) tight mounds (n = 317 trajectories), 71% of cells rotated. We conclude that myosin II filaments are essential for rotational motion.

Our mutant analysis also showed that the myosin II RLC is required for proper cell rotation in the mound. Compared with their parent (JH10; n = 535 trajectories), fewer RLC− cells (n = 2013 trajectories) rotated, their rotational velocity was slower, and rotation eventually stopped. Only 21% of RLC− tight mound cells were classified as rotational (Figure 4, G and H), compared with 80% of parental tight mound cells. The mean rotational velocity for RLC− cells was 3.5 μm/min (n = 14 cells; range, 1–15 μm/min), compared with a mean rotational velocity of 15.8 μm/min for the parent (n = 11 cells; range, 4–36 μm/min). RLC− cells stopped rotating completely by 5–7 h after mound formation. At this time, ∼14% of the cells exhibited a radially outward movement away from the center of the mound, rarely seen in the parent.

Myosin II Plays a Role in Establishing Chemotactic Wave Patterns

The cell motion data show that myosin II is required for rotational motion. It is during rotation that the myosin II C-to-spot pattern becomes especially prominent, suggesting that this pattern may reflect myosin II function during rotation. This pattern and its association with rear retraction suggest that myosin II could play a mechanical role in cell motility in the mound. However, in principle, the defective rotation observed in the myosin II mutants could also be caused by a defect in guidance signals.

Guidance signals in the mound have been indirectly visualized using a modified form of time-lapse, dark-field microscopy. As applied to mounds, this technique reveals light and dark patterns moving across the mound. Some evidence suggests that these optical density patterns represent underlying chemical cAMP waves propagated by cells (Siegert and Weijer, 1995; Rietdorf et al., 1996). Dark-field images are thought to reveal these wave patterns by highlighting the cell shape change or “cringe,” which occurs as a cAMP pulse passes by a cell (Alcantara and Monk, 1974; Tomchik and Devreotes, 1981). When cells rotate in a mound, counter-rotating spiral waves are always observed (Siegert and Weijer, 1995) (see example in Figure 5, A and B). Because cells are known to move perpendicular to dark-field wave fronts, rotational motion is a likely consequence of the rotating spiral wave patterns.

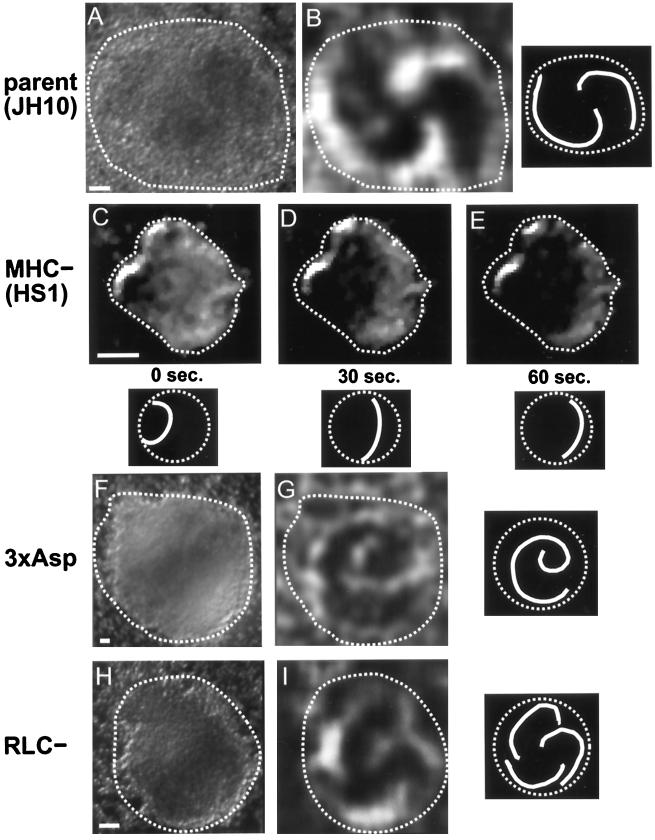

Figure 5.

Dark-field waves in parent and mutant mounds. Wave patterns are most easily visualized in movies available online or at the author’s web site listed in ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The still-frame images shown here have been image enhanced to help highlight the wave front. Adjacent to each wave image is a schematic of the wave pattern. The dashed line in the schematic indicates the mound periphery, and the solid line indicates the wave front. (A) Dark-field image of parent strain (JH10) mound. The wave pattern is not visible in a still-frame image but can be seen when a time sequence of such images is played in rapid succession, as available online. (B) Two-armed spiral wave from the same mound as in A, but after subtraction of time points 30 s apart to enhance the differences between the two images and thereby highlight the moving wave front (which in this case rotates counterclockwise). (C–E) Aberrant waves in an MHC− mound. Instead of producing a clear wave front, these mutant mounds tended to form a dark zone that propagated, in this case from left to right, into a light zone. Wave centers tended to be at the edge of the mound (leftmost edge in this mound) and were transient, with new centers eventually arising elsewhere near the mound periphery. (F) Dark-field image of 3xAsp mound. (G) Apparently normal wave in a 3xAsp mound displaying a single dominant center about which a one-armed spiral wave rotates. The image is the same mound as in F but after subtraction of time points 90 s apart to enhance the wave profiles. (This one-armed spiral wave rotates clockwise.) (H) Dark-field image of an RLC− mound. (I) Apparently normal wave in an RLC− mound displaying a single dominant center about which a three-armed spiral wave rotates. The image is the same mound as in H but after subtraction of time points 30 s apart. (This rotates counterclockwise.) Bars, 40 μm.

To test for impaired signaling, we examined dark-field wave patterns in the three different myosin II mutants. In MHC− mounds, we found that dark-field signaling waves were present, but their patterns were disrupted. Wave patterns in the parent strain mounds (n = 15) took the form of either concentric rings (bull’s eye pattern) or spirals (Figure 5, A and B), in approximately equal proportions. In contrast, MHC− mounds (n = 20) did not have organized wave patterns. In these mounds, a single wave front sometimes propagated across the mound (Figure 5, C–E), often followed by weaker pulses arising from different locations in the mound. These pulses appeared to be bona fide waves, because when they reached the edge of the mound they became more clearly visible as they propagated down the lengths of streams.

Dark-field wave patterns are thought to arise from a transient cell shape change or cringe induced by the passage of a cAMP wave (Siegert and Weijer, 1995; Rietdorf et al., 1996). The presence of such dark-field waves in the MHC− cells suggested that these cells might be able to undergo a shape change or cringe in response to cAMP. To test this directly, we imaged single cells isolated on a coverslip before, during, and after addition of cAMP. Over a range of cAMP concentrations (5 × 10−7–3 × 10−4 M), a cell shape change could still be detected in 74% (n = 94) of MHC− cells (Figure 6) and, as expected, 100% (n = 15) of the parental strain (Figure 6). These data demonstrate that the MHC is not required for a cell shape change induced by cAMP and further suggest that dark-field waves remain visible in MHC− because these cells are still exhibiting some cringe response.

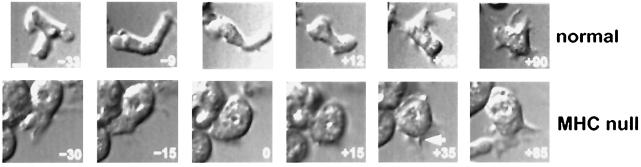

Figure 6.

Cell cringe in response to cAMP. Numbers in each panel indicate the approximate time (±2 s) before or after addition of cAMP to starved cells of the normal strain (top row) or MHC− cells (bottom row). Observe how the central cell in each panel is more elongate before addition of cAMP but becomes more rounded at, or just subsequent to, addition of cAMP. Specifically, the normal cell is less elongated at +12 s compared with −9 or −33 s, and the MHC− cell is nearly round at +15 s compared with −30 or −15 s. By +30 s, this particular MHC− cell begins to show signs of new pseudopodia (arrow) and by +85 s is once more elongate. This normal cell shows new pseudopodia (arrow) by the +30-s time point. cAMP concentrations ranging from 10−7–10−4 M were tested, and no significant differences were observed by this assay. For the images shown, 10−4 M cAMP was used in the top row, and 10−7 M cAMP was used in the bottom row. Bar, 5 μm.

The wave patterns that are present in MHC− mounds are aberrant, and this offers a possible explanation for the lack of rotation in the MHC− cells. To test whether the MHC− cells could move rotationally when provided with proper guidance signals, we seeded parent mounds with a few labeled MHC− cells. To incorporate mutant cells into mound interiors, we added a small number of labeled, starved mutant cells to parent mounds as they were forming. We then observed the mutant cells within mounds. Seventy-five percent of the mutant cells were seemingly oblivious to the vigorous rotational motion of the parent strain and quickly drifted to the inner core or outer edge (Figure 7, A and B). Twenty-five percent rotated in the same direction as the parent cells but reached the inner core or outer edge of the mound within at most a quarter of a full rotation around the mound (Figure 7, A and B). Parent cells similarly seeded into normal mounds always joined the rotational motion and never segregated to the mound’s periphery or core (Figure 7, C and D). We conclude that the MHC− cells likely suffer from a motility defect, which leads to aberrant motion even in the presence of proper guidance cues. In sum, our dark-field wave studies demonstrate that the MHC is somehow required to organize signaling wave patterns, and our seeding experiments support a mechanical role for the MHC in motility.

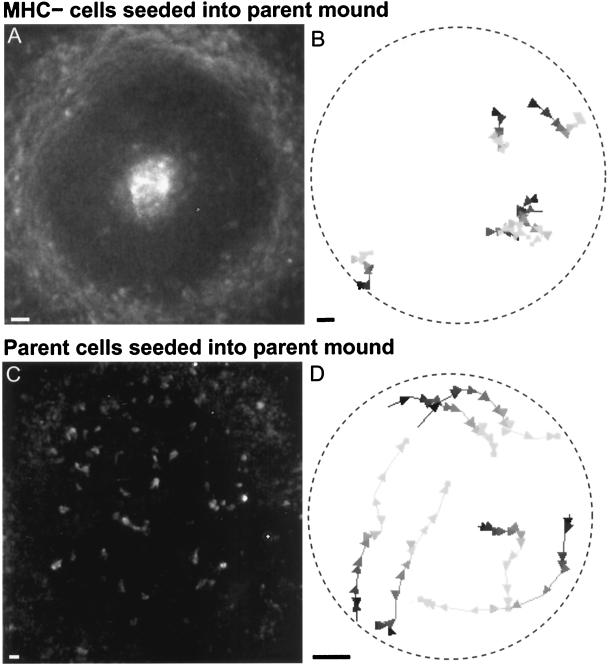

Figure 7.

Fluorescently labeled cells seeded into a mound composed of parent strain cells. (A) In such chimeric mounds, MHC− cells segregated to the inner core or outer periphery. Shown is one image from a time-lapse movie obtained ∼3 h after a small number of starved MHC− cells were added to a mound of unlabeled parent strain cells. (B) MHC− cells fail to rotate in such chimeric mounds. Five sample trajectories are shown (the two near the 4:00 position partially overlap). Conventions for trajectory display are as described in Figure 4. Arrowheads represent time points 1 min apart. The slow, irregular movements of the MHC− cells indicate that the spiral wave generated by the parent cells is not enough to restore normal motion in MHC− cells. (C) Control. One time point of a 2D time-lapse movie taken ∼3.5 h after starved parent cells were added to a parent mound. Fluorescently labeled parent cells do not segregate in these mounds. (D) Typical trajectories of parent cells added to a parent strain mound. The seeded cells rotate normally. Arrowheads represent time points 40 s apart. Bars, 10 μm.

When we examined signaling wave patterns in the 3xAsp mutant, we found some improvement compared with MHC− cells. 3xAsp waves were more clearly visible, and organized wave patterns were observed. Of 15 3xAsp mounds examined, 10 exhibited concentric ring waves, and the other 5 exhibited one-armed spiral waves (Figure 5, F and G). Although such one-armed spirals are sometimes observed in other WT strains, the parent strain for the 3xAsp mutant normally exhibited a multiarmed spiral wave pattern. This suggests that the production and/or maintenance of multiarmed spiral wave patterns may require normal myosin II filament levels. Because some 3xAsp mounds do exhibit at least a single-armed spiral, this should be a sufficient signal for rotational cell motion. Nevertheless, 3xAsp mound cells never rotate; so our data suggest that filamentous myosin II also plays a mechanical role in cell motility in the mound.

In mounds of the third mutant, RLC−, we found normal wave patterns comparable to those in the parent strain, demonstrating that the RLC is not required for normal wave patterns. Of 34 RLC− mounds examined, 18 showed concentric ring waves, and 16 showed multiarmed spiral waves, which is in similar proportion to the parent strain (Figure 5, H and I). The latter patterns should be sufficient for normal rotational motion, but nevertheless the RLC− cells rotate more slowly and eventually stop. This implies that the RLC plays a mechanical role in rotational cell motility.

RLC− Myosin II Exhibits an Aberrant C-to-Spot and Reduced Cortical Localization

Of the three mutants examined, the RLC− cells were the only ones that appeared to exhibit completely normal signaling wave patterns in the mound; so this mutant provides the cleanest example of a purely mechanical defect in cell motility attributable to a disruption in myosin II. If myosin II’s mechanical function is exemplified by some visible feature such as the C-to-spot, then we reasoned that feature might be aberrant in RLC− cells.

To observe myosin II in living RLC− cells, we transformed RLC− cells with the GFP-MHC construct. These RLC− cells already have an MHC gene, unlike the GFP-MHC cells described above, in which GFP-MHC was expressed in an MHC− background. To test whether excess MHC might disrupt myosin II distributions, we transformed a parental strain (JH10) with the GFP-MHC. These cells exhibited comparable patterns of GFP-MHC, as seen in the MHC− background, suggesting that excess myosin II did not affect its spatial and temporal distributions.

In RLC− cells, previous immunofluorescence studies with a myosin II antibody had shown that myosin II tended to form aberrant aggregates in many vegetative cells (Chen et al., 1994). After transformation of the RLC− cells with GFP-MHC, we observed comparable aggregates in vegetative and starved cells (Figure 8, E and F), further substantiating that the GFP-MHC was a reliable reporter of myosin II distributions in the RLC− cells. These myosin II aggregates in the RLC− cells (Figure 8F) were not the same as the spot that we observed in normal cells after condensation of a C pattern (Figures 1 and 2). The myosin aggregates were significantly larger than the spot observed in a C-to-spot. Moreover, the RLC− myosin II aggregates persisted for hours, whereas the spots associated with a normal condensing C disintegrated within minutes, at most.

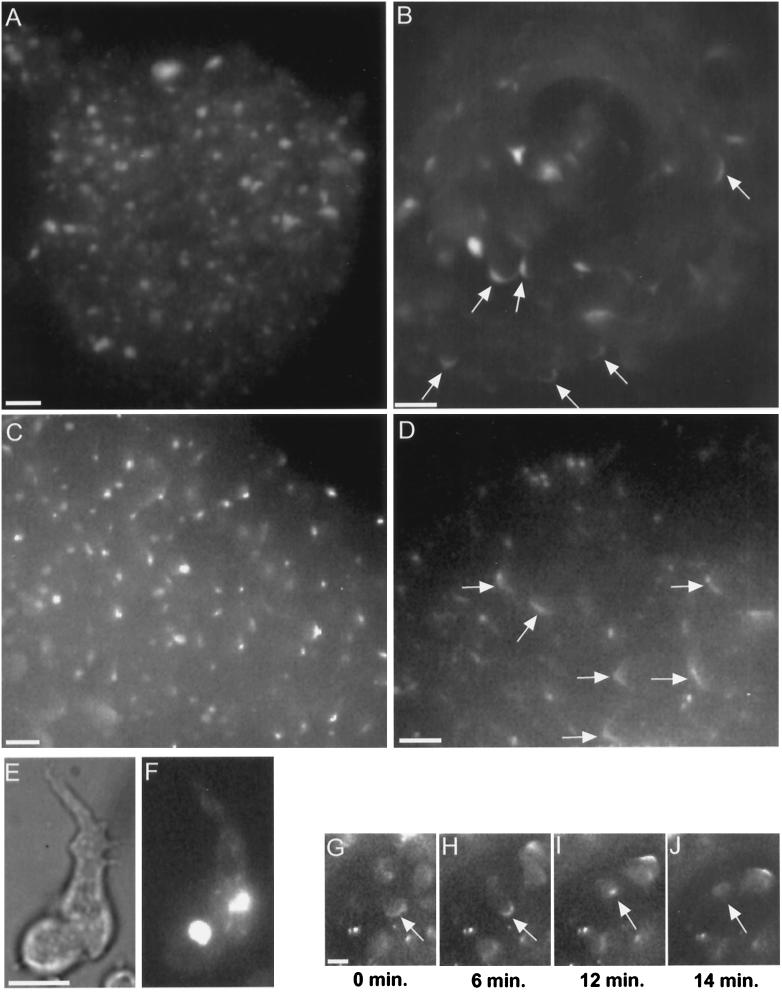

Figure 8.

Myosin II in RLC− cells. Starved cells with GFP-MHC reveal a bright myosin II aggregate (E, bright field; F, fluorescence), consistent with the distribution of myosin II previously observed by immunofluorescence in isolated RLC− cells (Chen et al., 1994). RLC− cells retain their GFP-MHC aggregate during aggregation and in the early mound (A). Cells in the mound shown in A were moving randomly, as is normal for early mounds. As rotation begins in RLC− mounds, the GFP-MHC aggregate disappears, and a cortical C pattern appears instead (B, arrows). The disappearance of the GFP-MHC aggregate is not an artifact of this GFP construct. Immunofluorescence staining reveals native myosin II aggregates in an early mound (C) and reveals Cs (arrows) and spot patterns in a later mound (D). Rotating RLC− mound cells with GFP-MHC exhibit a C-to-spot transition (G–J), including dissolution of the spot (J). The C-to-spot transition is much slower than normal (also see Figure 3A). Although the mound shown in B is composed entirely of RLC− cells, the generalized enhancement of GFP-MHC around cell perimeters is largely absent. Compare with Figure 1, C–F, which shows a mound also composed entirely of normal GFP-MHC cells, in which many individual cell outlines can be clearly discerned. Bars, 10 μm.

We found that the aberrant GFP-MHC aggregates were still present during aggregation and in the early mounds of RLC− cells (Figure 8A). Within early mounds of RLC− or its parent, cells move randomly and then after ∼0.5 h, organized rotational motion develops. To our surprise, when rotation ensued in the RLC− cells, the aberrant GFP-MHC aggregates disintegrated. GFP-MHC instead became concentrated at the posterior cortex of rotating cells where C-to-spot patterns were observed (Figure 8, B and G–J). These RLC− C-to-spots were different in two ways from the parent: 1) the C appears to be shorter in RLC− cells (lengths ranging from 7 to 13 μm [average, 10.9 μm] in RLC− [n = 7 cells] vs. lengths ranging from 10 to 17 μm [average, 13.3 μm] in the parent [n = 7 cells]), although because of a small sample size, we could not assess statistical significance; and 2) in RLC− cells the C-to-spot transition was slower (2–22 min [n = 6 cells] versus 0.2–5 min in the parent [n = 9 cells]) (Figure 3A). In the RLC− cells, the spot that formed at the end of a C-to-spot transition always disintegrated (Figure 8J), just as in the parent strain. The GFP-MHC distribution patterns in the mound did not appear to be artifactual, because we observed similar patterns for native myosin II in RLC− mounds visualized by immunofluorescence with a myosin II antibody (Figure 8, C and D).

The GFP-MHC distribution in rotating RLC− cells differed from the parent in one other way. In parent strain mounds containing only GFP-MHC cells (i.e., no unlabeled cells), the entire cell cortex was often visible circumscribing each cell (Figure 1, C–F). In rotating parent cells, this general cortical staining was typically less intense than the cortical staining specifically associated with a C or a spot at the posterior. In rotating RLC− cells, this general cortical staining of GFP-MHC was typically absent (Figure 8B). After rotation finally stopped in RLC− mounds (which occurred at a point when the cells had remained at the mound stage for at least 2–4 h longer than normal), we found that all GFP-MHC was diffusely distributed throughout the cell.

DISCUSSION

The Myosin II C-to-Spot Is Associated with Retraction of Cell Extensions

We have examined the distribution of GFP-MHC in Dictyostelium cells and have found a novel, dynamic pattern in cells undergoing rotational motion within the multicellular mound. In these rotating cells, a C of myosin II became localized to the rear cortex and converted to a spot as the rear retracted. The spot then dissolved, and later a new C reformed. This is the first report of dynamic redistributions of myosin II associated with cell locomotion. Because this C-to-spot transition in myosin II was so prominent during rotational motion, we asked whether myosin II was required for such motion. In three different myosin II mutants, we showed that rotation was abolished or severely hindered, even when a proper chemotactic signal was present. This suggests that each of these myosin II mutants suffers a mechanical defect in motility. Two observations suggest that at least part of myosin II’s mechanical function during rotation involves the C-to-spot transition. First, the C-to-spot is the most prominent distribution of myosin II in rotating cells. Second, the RLC− mutant exhibits both defective rotation and an aberrant C-to-spot.

What function might this C-to-spot serve? We found several different examples suggesting it could play a role in retraction of cell extensions. Within the mound, rotating cells shortened as the C converted to a spot at the cell rear. For cells crawling between other cells on a substrate, we observed a comparable C-to-spot transition as the cell rear was retracted between adjacent cells. We also found for isolated cells on a substrate that pseudopodia retracted as a C converted to a spot. Enhanced cortical myosin was not present in extending pseudopodia; so monomers of myosin II may assemble into filaments just as the pseudopod begins to retract.

Although it was seen in several cases of retracting cell extensions, this C-to-spot process was most prominent during rotational motion when the mound condenses into a densely packed cell mass. This tightly confined hemisphere is likely to have many cell–cell adhesive forces that place greater constraints on cell movement than would be present for individual cells on a substrate. If the C-to-spot helps a moving cell overcome this tight packing and adhesion, we would expect to see it occur when cells are in such an environment. Consistent with this expectation, a myosin II C has also been observed in fixed cells in the densely packed environment of the slug (Eliott et al., 1991; Yumura et al., 1992), as well as in fixed cells under the constraining pressure of an agar overlay (Yumura and Fukui, 1985). Moores et al. (1996) also observed a spot in pseudopodia with the same GFP-MHC but did not detect the preceding C, in part because they may not have examined motion in the mound when the C-to-spot conversion becomes most prominent.

If the C-to-spot is involved in retraction of cell extensions, it could aid these processes by helping pull in the extension or by applying a shear force to cell–cell contacts to overcome adhesive bonds. A role for myosin II in overcoming adhesion is supported by studies of Jay et al. (1995), who showed that MHC− cells barely move on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine, even though parent cells at the same concentration of poly-l-lysine moved normally.

Regardless of its specific function, we suggest that the C-to-spot transition could reflect an actomyosin contraction. Some evidence to support this model comes from our observation that cells without the myosin II RLC exhibited a slower C-to-spot transition. The time required for the C-to-spot conversion could be related to the rate of myosin movement relative to actin, as measured in in vitro motility assays. In such assays, other myosins lacking the RLC were found to move more slowly (Lowey et al., 1993; Uyeda and Spudich, 1993; Trybus et al., 1994).

In addition to highlighting the C-to-spot transition, observing cell motion in the 3D adhesive environment of the mound allowed us to uncover distinctions among several myosin II mutants, which had previously exhibited nearly identical phenotypes. For example, 3xAsp and MHC− cells both displayed defects in cytokinesis, receptor capping, and developmental arrest (DeLozanne and Spudich, 1987; Knecht and Loomis, 1987; Egelhoff et al., 1993). We found, however, a striking difference between signaling wave patterns in these two mutants (see below). Similarly, RLC− and MHC− cells also displayed comparable defects in cytokinesis and developmental arrest, although unlike MHC− cells, RLC− cells could cap cell surface receptors (Chen et al., 1994). Our findings now show that RLC− cells can rotate in the mound, whereas MHC− cells cannot, even though both mutant strains arrest development at the mound. These observations not only suggest that different components of the myosin II molecule may contribute to different functions, they also underscore the utility of sophisticated assays for uncovering mutant phenotypes.

Myosin II Is Not Required for Visualization of Signaling Waves or for a Cell Shape Cringe in Response to cAMP

We used dark-field microscopy of mounds to visualize so-called signaling waves thought to reflect underlying cAMP signals (Siegert and Weijer, 1995; Rietdorf et al., 1996). We could still see waves in mounds lacking the MHC, even though these dark-field waves are known to reflect transient cell shape changes or the so-called cringe in response to passage of a cAMP wave (Alcantara and Monk, 1974; Futrelle et al., 1982; Siegert and Weijer, 1995). In addition, we recorded individual MHC− cells cringing upon addition of cAMP, suggesting that sufficient cell shape changes occur even in the absence of myosin II to permit wave visualization. However, the MHC− waves are less intense than normal, as expected if myosin II ordinarily plays some role in the cringe response (Yumura and Fukui, 1985). Our observation of less intense wave profiles in the MHC− cells is also consistent with a body of data suggesting that these mutant cells have altered cell shapes (Wessels et al., 1988; Shelden and Knecht, 1996; Xu et al., 1996). The fact that waves are nevertheless visible in MHC− mounds and that MHC− cells cringe upon addition of cAMP does suggest that other myosins and/or actin also contribute to cell shape changes in response to chemotactic signals in the mound.

When two other myosin II mutants (3xAsp and RLC−) were examined, we observed waves of essentially normal intensity. The 3xAsp cells contain predominantly monomeric myosin II, suggesting that myosin II monomers may be sufficient for the requisite cell shape change, or that residual filamentous myosin II in 3xAsp cells is sufficient. Our data also suggest that the RLC is not needed for the cell shape change required to see waves, because waves of normal intensity were also seen in this mutant.

Myosin II Is Required for Normal Signaling Patterns in the Mound

Because we could visualize waves in the myosin II mutants, we were also able to see the wave pattern. Surprisingly we found that in mounds of some myosin II mutants, the wave pattern is altered. This suggests that myosin II itself is involved in establishing these patterns. In the parent strain, we consistently observed one dominant signaling center either from which concentric waves emanated or about which a multiarmed spiral wave pivoted. In contrast, MHC− mounds could not maintain a dominant signaling center, and neither concentric nor spiral waves were ever seen. These data show that the MHC is required for establishing a single, dominant signaling center within mounds. In the second mutant examined, 3xAsp, a dominant signaling center was established in each mound, but only one-armed spiral waves formed, never multiarmed waves. This suggests that myosin II monomers or the residual filaments still present in the 3xAsp strain are sufficient to establish center dominance, but filamentous myosin II is otherwise required for multiarmed spiral waves. The third mutant that we examined, RLC− cells, showed normal wave patterns, demonstrating that the RLC is not required for wave pattern establishment.

How might myosin II be required for proper signaling wave patterns? One possibility is that motile defects indirectly cause signaling defects. In normal mounds, a subset of prestalk cells ordinarily migrates to the mound apex to form a cluster that might be involved in the initiation of signaling waves. In MHC− mounds, a prestalk cluster still forms in the middle core of the mound, although not at the mound apex (Traynor et al., 1994). Thus, MHC− mounds should also have a dominant signaling center if prestalk cluster formation is a prerequisite for this process. More generally, it does not appear as if extensive cell motility in the mound is required to establish a dominant signaling center. Cell motility in mounds of the 3xAsp mutant was as minimal as that in the MHC− mutant, yet 3xAsp mounds consistently formed a dominant signaling center. Thus, at present, it is unclear how defects in motility could indirectly cause the signaling defect seen in the MHC− cells.

The alternative possibility is that myosin II in some way participates directly in the signaling process that establishes a dominant wave center, although to date there is no evidence to indicate how myosin II could play such a direct role in signaling. The mechanism by which a dominant dark-field wave center is established in the mound is unknown. Some upstream regulatory genes in this process have been identified, and some evidence suggests that in normal mounds multiple centers are suppressed by some form of inhibition (Sukumaran et al., 1998), but none of these data suggests how myosin II could be involved. The dark-field waves observed in mounds may reflect an underlying cAMP signal (Siegert and Weijer, 1995; Rietdorf et al., 1996), although that has not been proven. Even if this is true, the establishment or maintenance of a dominant signaling wave center may be independent of cAMP or whatever else may underlie the dark-field wave. In any event, it is difficult to envision that myosin’s role in center establishment occurs via cAMP signaling, because there is no direct evidence to date that cAMP signaling is altered in MHC− cells. These cells are chemotactically responsive, have normal levels of cAMP receptors, and secrete normal levels of cAMP in response to a cAMP stimulus (Peters et al., 1988). Until more is known about the mechanisms of wave center dominance in mounds, it is difficult to speculate about myosin’s potential role in this process. More generally, however, some precedent exists for the influence of cytoskeletal proteins upon cell signaling (Moll et al., 1991; Bahler, 1996; Chrzanowska-Wodnicka and Burridge, 1996; Sisson et al., 1997), and our observations on wave patterns in the myosin II mutants may reflect another example of such phenomena.

Myosin II’s Function

What then is myosin II’s role in motility within the mound? Three possible functions have been cited (see INTRODUCTION), and our results have provided, in varying degrees, some measure of support for each.

Our observations of disrupted signaling wave patterns in MHC− cells suggest that myosin II is involved in some way in establishing a dominant signaling center in the mound. Our observations of enhanced GFP-MHC throughout the cell cortex of rotating cells are consistent with the hypothesis that myosin II supplies structural rigidity to cells within a cell mass (Knecht and Shelden, 1995; Shelden and Knecht, 1995). This structural rigidity may be critical for proper rotational motion, because altered rotation in RLC− cells was correlated with a loss of this generalized cortical distribution of GFP-MHC. Our observations of the C-to-spot transition support a role for myosin as a motor that generates some of the force required to withdraw cell extensions, a function that may be particularly important in the adhesive environment of the mound. Consistent with this possibility, the C-to-spot transition was slower than normal in RLC− cells, correlating with the reduced velocity of these mutant cells. Our data suggest that each of these factors may contribute to the defective rotational motion observed in various myosin II mutants.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rex Chisholm and Tom Egelhoff for providing cells and James Sabry and James Spudich for providing cells and the GFP-MHC construct. We thank John Cooper and Kathy Miller for helpful discussions and two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM-47330 to J.G.M. Selected time-lapse movies of the data in Figures 1, 2, and 5 are also available at the authors’ web site (http://rex.nci.nih.gov/RESEARCH/basic/lrbge/fig.html).

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Alcantara F, Monk M. Signal propagation during aggregation in the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;85:321–334. doi: 10.1099/00221287-85-2-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi V, Doolittle KW, Parulkar G, McNally JG. Cell tracking using a distributed algorithm for 3D-image segmentation. Bioimaging. 1994;1:98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bahler M. Myosins on the move to signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Ostrow BD, Tafuri SR, Chisholm RL. Targeted disruption of the Dictyostelium RMLC gene produces cells defective in cytokinesis and development. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1933–1944. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1996;6:1403–1415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RL, Retzinger GS, Steck RL. Novel morphogenesis in Ax-3, a mutant strain of the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;121:319–331. doi: 10.1099/00221287-121-2-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conchello JA, McNally JG. Proceedings of the Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers. Vol. 2655. Bellingham, WA: Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers; 1996. Fast regularization technique for expectation maximization algorithm for optical sectioning microscopy; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- DeLozanne A, Spudich JA. Disruption of the Dictyostelium myosin heavy chain gene by homologous recombination. Science. 1987;236:1086–1091. doi: 10.1126/science.3576222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle KW, Reddy I, McNally JG. 3D analysis of cell movement during normal and myosin-II-null cell morphogenesis in Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1995;167:118–129. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelhoff TT, Lee RJ, Spudich JA. Dictyostelium myosin heavy chain phosphorylation sites regulate myosin filament assembly and localization in vivo. Cell. 1993;75:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80077-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliott S, Joss GH, Spudich A, Williams KL. Patterns in Dictyostelium discoideum: the role of myosin II in the transition from the unicellular to the multicellular phase. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:457–466. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.2.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliott S, Vardy PH, Williams KL. The distribution of myosin II in Dictyostelium discoideum slug cells. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1267–1274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futrelle RP, Traut J, McKee WG. Cell behavior in Dictyostelium discoideum: preaggregation response to localized cyclic AMP pulses. J Cell Biol. 1982;92:807–821. doi: 10.1083/jcb.92.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger JA, Firtel RA. Analysis of Gα4, a G-protein subunit required for multicellular development in Dictyostelium. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:38–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay PY, Pham PA, Wong SA, Elson EL. A mechanical function of myosin II in cell motility. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:387–393. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay RR, Insall RH. In: Dictyostelium discoideum. In: Embryos: Color Atlas of Development. Bard JBL, editor. London: Wolfe; 1994. pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman KA, McNally JG. Mound cell movement and morphogenesis in Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1999;208:416–429. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht DA, Loomis WF. Antisense RNA inactivation of myosin heavy chain gene expression in Dictyostelium discoideum. Science. 1987;236:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.3576221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht DA, Shelden E. Three-dimensional localization of wild-type and myosin II mutant cells during morphogenesis of Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1995;170:434–444. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowey S, Waller GS, Trybus KM. Skeletal muscle myosin light chains are essential for physiological speeds of shortening. Nature. 1993;365:454–456. doi: 10.1038/365454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manstein DJ, Titus MA, DeLozanne A, Spudich JA. Gene replacement in Dictyostelium: generation of myosin null mutants. EMBO J. 1989;8:923–932. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally JG, Preza C, Conchello JA, Thomas LJ. Artifacts in computational optical-sectioning microscopy. J Opt Soc Am [A] 1994;11:1056–1067. doi: 10.1364/josaa.11.001056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, Sansig G, Fattori F, Van der Putten H. The murine rac1 gene: cDNA cloning, tissue distribution, and regulated expression of rac1 mRNA by disassembly of actin microfilaments. Oncogene. 1991;6:863–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moores SL, Sabry JH, Spudich JA. Myosin dynamics in live Dictyostelium cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:443–446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellen W, Datta S, Reymond C, Sivertsen A, Mann S, Crowely T, Firtel RA. Molecular biology in Dictyostelium: tools and applications. Methods Cell Biol. 1987;28:67–100. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak C, Spudich JA, Elson EL. Capping of surface receptors and concomitant cortical tension are generated by conventional myosin. Nature. 1989;341:549–551. doi: 10.1038/341549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DJM, Knecht DA, Loomis WF, DeLozanne A, Spudich J, Van Haastert PJM. Signal transduction, chemotaxis, and cell aggregation in Dictyostelium discoideum cells without myosin heavy chain. Dev Biol. 1988;128:158–163. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preza C, Miller MI, Thomas LJ, McNally JG. Regularized linear method for reconstruction of three-dimensional microscopic objects from optical sections. J Opt Soc Am [A] 1992;9:219–228. doi: 10.1364/josaa.9.000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reines D, Clarke M. Quantitative immunochemical studies of myosin in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1133–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietdorf J, Siegert F, Weijer CJ. Analysis of optical density wave propagation and cell movement during mound formation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Dev Biol. 1996;177:427–438. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppel KM, Uyeda TQP, Spudich JA. Role of highly conserved lysine 130 of myosin motor domain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18773–18780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelden E, Knecht DA. Mutants lacking myosin II cannot resist forces generated during multicellular morphogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1105–1115. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelden E, Knecht DA. Dictyostelium cell shape generation requires myosin II. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;35:59–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)35:1<59::AID-CM5>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert F, Weijer CJ. Spiral and concentric waves organize multicellular Dictyostelium mounds. Curr Biol. 1995;5:937–943. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson JC, Ho KS, Suyama K, Scott MP. Costal2, a novel kinesin-related protein in the Hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell. 1997;90:235–245. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA. Dictyostelium discoideum: methods and perspectives for study of cell motility. Methods Cell Biol. 1982;25:359–364. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran S, Brown JM, Firtel RA, McNally JG. lagC-null and gbf-null cells define key steps in the morphogenesis of Dictyostelium mounds. Dev Biol. 1998;200:16–26. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchik KJ, Devreotes PN. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate waves in Dictyostelium discoideum: a demonstration by isotope dilution-fluorography. Science. 1981;212:443–446. doi: 10.1126/science.6259734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor D, Tasaka M, Takeuchi I, Williams J. Aberrant pattern formation in myosin heavy chain mutants of Dictyostelium. Development. 1994;120:591–601. [Google Scholar]

- Trybus KM, Waller GS, Chatman TA. Coupling of ATPase activity and motility in smooth muscle myosin is mediated by the regulatory light chain. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:963–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda TQP, Spudich JA. A functional recombinant myosin II lacking a regulatory light chain-binding site. Science. 1993;262:1867–1870. doi: 10.1126/science.8266074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels D, Soll DR, Knecht D, Loomis WF, DeLozanne A, Spudich J. Cell motility and chemotaxis in Dictyostelium amebae lacking myosin heavy chain. Dev Biol. 1988;128:164–177. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XS, Kuspa A, Fuller D, Loomis WF, Knecht DA. Cell-cell adhesion prevents mutant cells lacking myosin II from penetrating aggregation streams of Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 1996;175:218–226. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumura S, Fukui Y. Reversible cyclic AMP-induced change in distribution of myosin thick filaments in Dictyostelium. Nature. 1985;314:194–196. doi: 10.1038/314194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumura S, Kurata K, Kitanishi-Yumura T. Concerted movement of prestalk cells in migrating slugs of Dictyostelium revealed by the localization of myosin. Dev Growth & Differ. 1992;34:319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1992.tb00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.