Abstract

Thrombospondin 2 (TSP2) can inhibit angiogenesis in vitro by limiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis of endothelial cells (ECs). TSP2 can also modulate the extracellular levels of gelatinases (matrix metalloproteases, MMPs) and potentially influence the remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Here, we tested the hypothesis that by regulating MMPs, TSP2 could alter EC-ECM interactions. By using a three-dimensional angiogenesis assay, we show that TSP2, but not TSP1, limited angiogenesis by decreasing gelatinolytic activity in situ. Furthermore, TSP2-null fibroblast-derived ECM, which contains irregular collagen fibrils, was more permissive for EC migration. Investigation of the role of TSP2 in physiological angiogenesis in vivo, using excision of the left femoral artery in both TSP2-null and wild-type mice, revealed that TSP2-null mice displayed accelerated recovery of blood flow. This increase was attributable, in part, to an enhanced arterial network in TSP2-null muscles of the upper limb. Angiogenesis in the lower limb was also increased and was associated with increased MMP-9 deposition and gelatinolytic activity. The observed changes correlated with the temporal expression of TSP2 in the ischemic muscle of wild-type mice. Taken together, our observations implicate the matrix-modulating activity of TSP2 as a mechanism by which physiological angiogenesis is inhibited.

The thrombospondins (TSPs) are a small family of five, secreted, modular glycoproteins (TSPs 1 to 5), with diverse functions.1,2 TSP1 and TSP2 share a high degree of similarity and are thought to constitute a subfamily. TSP1 has been extensively studied and has been shown to be synthesized by a variety of cells and to interact with a number of receptors such as CD36, CD47, GPIIb/IIIa, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), and several integrins.3 TSP2, has not been extensively studied, but because of its similarity to TSP1 it is believed that it can bind to the same receptors.4,5 In fact, CD36, heparan sulfate proteoglycan, LRP, and αVβ3 have been shown to be receptors for TSP2.6,7 TSPs have also been shown to interact with several extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins including collagen, fibrinogen, and fibronectin.2,8 Recently, the very low-density lipoprotein receptor was shown to be a receptor for TSP1 and TSP2, and their interaction was shown to inhibit the division of microvascular endothelial cells (ECs).9

TSP1 was identified as the first endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis.10 The anti-angiogenic activities of TSP1 and TSP2 have been the focus of rigorous investigation and numerous studies have implicated both proteins in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis.3,11,12,13 TSP1 and TSP2 have also been shown to have broad anti-angiogenic activities in in vivo and in vitro assays, and a down-regulation of TSP1 synthesis has been implicated in a number of pathological conditions that involve increased angiogenesis. Like TSP1, TSP2 can directly influence ECs by inhibiting basic fibroblast growth factor-induced migration, lysophosphatidic acid-induced mitogenesis, and the formation of focal adhesions.14,15,16,17 A mechanism for the anti-angiogenic effect of TSP1 was shown to involve the interaction of the type I repeats of TSP1 with the scavenger receptor CD36 on ECs.18 Subsequent studies determined the downstream events that included activation of p59fyn leading to activation of p38MAPK and caspase 3-like proteases and induction of EC apoptosis.19 However, it is unclear if the same mechanism is involved in the regulation of physiological angiogenesis. It is also unclear whether TSP2 can induce the activation of this cascade, even though binding of TSP2 to CD36 on ECs has been reported.20 Surprisingly, studies have shown that TSP2 does not induce apoptosis in ECs, but inhibits cell cycle progression independent of CD36.9,21

Differences between the phenotypes of TSP1-null and TSP2-null mice suggest that the two proteins might function differently. For example, wound-healing studies in TSP1-null, TSP2-null, and double-TSP1/2-null mice indicated that, based on spatiotemporal expression patterns, only the loss of TSP2 could lead to augmented angiogenesis and accelerated repair.22,23 TSP1-null mice on the other hand, displayed delayed healing because of a compromised inflammatory response. Studies using models of ischemia have indicated that TSP1, and perhaps TSP2, can limit angiogenesis and hinder recovery of blood flow and tissue survival. Specifically, it was shown that TSP1-null mice have enhanced ischemic tissue survival in a random myocutaneous flap and hindlimb ischemia models.24,25 The ability of TSP1 to reduce NO/cGMP signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells was implicated as the mechanism mediating the endogenous response to ischemia. In both the myocutaneous flap and the hindlimb ischemia models, the association of TSP1 with CD47, but not CD36, was shown to be critical for these responses.24 In a separate study, double-TSP1/2-null mice were shown to have enhanced recovery from hindlimb ischemia.26 The improved phenotype could be conferred to wild-type (WT) mice and reversed in double-null mice after reverse bone marrow transplantation, suggesting that circulating TSP-producing cells, namely platelets, can influence recovery. Even though the observed changes were attributed to both TSP1 and TSP2, platelets do not contain TSP2.27 Thus, the participation of TSP2 in ischemic revascularization still remains unclear.

Clearly TSP1 and TSP2 can interact directly with ECs and modulate their function in vitro. However, recent studies have shown that the loss of TSP2 can cause an increase in the levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and/or MMP-9.28,29,30 To date, an increase in the levels of MMP-2 or MMP-9 and changes in ECM assembly in TSP1-null mice have not been reported. Perhaps this is attributable to the spatiotemporal expression of TSP1, which is predominantly secreted by platelets at sites of injury during the acute phase. A possible mechanism for the regulation of the extracellular levels of MMP-2 by TSP2 has been elucidated in dermal fibroblasts.31 Specifically, it was shown that TSP2 could bind MMP-2 and direct it to the catabolic receptor LRP, thus causing its clearance from the ECM. However, it is not clear whether the same mechanism can effectively control the levels of MMPs during tissue remodeling.

We postulated that TSPs act as ECM-associated proteins to influence EC function in an ECM-dependent manner. Thus, we analyzed the ability of TSP1 and TSP2 to inhibit angiogenesis in a three-dimensional matrix-based assay. We found that only TSP2 could limit angiogenesis, suggesting a mode of action independent of binding to receptors that are common between TSP1 and TSP2. Furthermore, we found that addition of TSP2 caused a decrease in gelatinolytic activity and in subsequent experiments, discovered ultrastructural abnormalities in the ECM produced by TSP2-null cells. Moreover, ECM derived from TSP2-null fibroblasts could alter EC function.

To investigate further the participation of TSP2 in modulating physiological angiogenesis we induced hindlimb ischemia via femoral artery excision in TSP2-null and WT mice and compared their respective abilities to recover blood flow. In addition, we determined the spatiotemporal expression of TSP2 during the recovery process. Ischemic tissues respond to reduced blood flow and hypoxia by mounting arteriogenic and subsequent angiogenic responses that collectively can lead to partial or full restoration of blood flow.32,33 Experimental hindlimb ischemia in mice has served as a useful model for the identification of molecules that are critical for recovery from ischemia. Specifically, because mice have pre-existing collaterals in the limbs, after ischemia they display an impressive increase in arteriogenesis and angiogenesis.34 In the present study, we found that the deposition of TSP2 is increased in ischemic tissues and that TSP2-null mice display more baseline collaterals and enhanced recovery of blood flow after ischemia. The improved recovery was associated with increased angiogenesis, and elevated levels of MMP-9 and gelatinolytic activity. Therefore, we conclude that the paracrine function of TSP2 as a modulator of ECM assembly was responsible, in part, for its anti-angiogenic activity.

Materials and Methods

Three-Dimensional Angiogenesis Assay

In preparation for the angiogenesis assay, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs) at 80% confluence were cultured overnight in M199 medium supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum. The cells were collected by trypsinization and incubated at 4°C for 10 minutes in M199 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Cells (5 × 105) in 250 μl of medium were mixed with 250 μl of growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and plated in 24-well plates. After 30 minutes of incubation to allow for gel formation, M199 medium containing 5% serum and various concentrations of TSP1 or TSP2 (1 to 10 μg/ml) was added to the wells. Human platelet TSP1 was from a commercial source (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and recombinant TSP1 and TSP2 were prepared as described previously.9 Selected wells were treated with 10 μmol/L MMP inhibitor GM6001 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) or dimethyl sulfoxide as vehicle control. Images were collected 24 hours later. The three-dimensional angiogenesis assay was also performed with 250 μl of Vitrogen (Cohesion, Palo Alto, CA) containing 90 μg of human fibronectin (BD Biosciences).

For detection of gelatinolytic activity, HUVECs were prepared as described above and mixed in Matrigel supplemented with 25 μg of DQ gelatin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and plated in 24-well plates. Gels were treated with 2 μg/ml of TSP1 or TSP2 or 10 μmol/L GM6001 for 24 hours and the medium was removed and the gels were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour. The cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 minutes, stained with 1 mg/ml of 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and visualized with fluorescence microscopy. Gelatinase activity was detected as green fluorescence and nuclei appeared blue. Gelatinase activity was quantified from digital images using Metamorph imaging software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Structural Characterization of TSP2-Null-Derived ECM

Primary dermal fibroblasts from WT mice or TSP2-null mice were prepared as we described previously and plated into 24-well plates (7.5 × 104 cells per well).29 Cells were incubated for 7 days in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 μmol/L ascorbic acid to increase the production of ECM. TSP2-null fibroblasts were also cultured in media that was supplemented with 10 μmol/L GM6001 or dimethyl sulfoxide. Cells were removed by incubation and gentle shaking at 37°C for 2 minutes in decellularization buffer (20 mmol/L NH4OH and 0.5% Triton X-100). For morphological analysis, the ECM was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with DAPI (1 mg/ml) and rhodamine phalloidin (1:100, Molecular Probes) to confirm the absence of cells. In addition, ECM was stained with anti-fibronectin antibody at 1:400 dilution (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Furthermore, mAb HU177 (100 μg/ml), a kind gift from Dr. Peter Brooks, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, was used to detect the presence of degraded collagen as described previously.35 For ultrastructural analysis, samples were prepared according to standard procedures for transmission electron microscopy analysis.

ECM-Mediated HUVEC Attachment and Migration

Confluent HUVECs were recovered by trypsinization and suspended in M199 medium deprived of serum. Three hundred μl of cell suspension (3 × 105 cells) was added to wells containing decellularized ECM. Cells were allowed to attach for 1 hour at 37°C and unattached cells were removed by washing (3× in PBS). Cell attachment was determined by the analysis of five random high-power (×200) microscopic fields (phase-contrast) per well. To determine the effects of the ECM on cell morphology and growth, cells were cultured on ECM for 12 hours. To visualize the actin cytoskeleton and nuclei, cells were fixed and permeabilized in 4% paraformaldehyde/Triton X-100 (JT Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) for 20 minutes at room temperature, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and DAPI according to standard protocols. All wells were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and examined with the aid of an Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) equipped with fluorescent optics. The effect of the ECM on cell migration was analyzed using a modified Boyden chamber (Transwell; Costar Corp., Cambridge, MA). Specifically, WT- or TSP2-null fibroblasts (5 × 104 cells per well) were plated in the top chamber of a transwell for 7 days and WT and TSP2-derived ECM were prepared by decellularization as described above. Subconfluent HUVECs were serum-starved overnight, collected by trypsinization, and suspended in M199 medium without serum. Cells (1 × 105) were added to the top of each migration chamber and allowed to migrate to the underside of the chamber for 6 hours in the presence or absence of 400 nmol/L sphingosine-1-phosphate. At the completion of the migration assay, cells were fixed and stained (Hema 3 Stain System; Fisher Diagnostics, Pittsburgh, PA) and the upper surface of the filter was scraped with a cotton swab. Four random fields (×100) per well were counted. All experiments were performed in quadruplicate wells and repeated at least twice.

Mouse Hindlimb Ischemic Model

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Yale University. TSP2-null (C57BL6/129SVJ mice) and littermate WT (C57BL6/129SVJ) mice were used for all experiments. Mouse hindlimb ischemia was induced as described previously.36,37 Briefly, after anesthesia (100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine), the left femoral artery was exposed under a dissection microscope. The proximal portion of the femoral artery and the distal portion of the saphenous artery were ligated. All branches between the two sites were ligated or cauterized and arteriectomy was performed. Sham operations involved skin incision without femoral artery ligation. A total of six mice per time point per genotype were analyzed.

Blood Flow Measurement

Blood flow was measured by the Periflux system with a laser Doppler perfusion unit (Perimed, North Royalton, OH). A deep measurement probe was placed directly onto the gastrocnemius muscle to ensure a deep muscle flow measurement. Ischemic and nonischemic limb perfusion were measured before and directly and then at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after surgery. The final blood flow value was expressed as the ratio of ischemic to nonischemic hindlimb perfusion. A total of six mice per time point per genotype were analyzed.

Arteriogenesis Analysis

Two weeks after surgery, mice were anesthetized and heparinized. Mice were perfused with PBS containing vasodilators (papaverine, 4 mg/L; adenosine, 1g/L) for 3 minutes at physiological pressure through the descending aorta, and blood was drained from the inferior vena cava.37 The vasculature was fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) for 5 minutes, flushed with PBS for 2 minutes, and infused with contrast agent (bismuth oxychloride in saline and 10% gelatin in PBS, 1:1). Mice were then immersed in ice to solidify the contrast agent. Microangiography was taken with a Kubtec X-ray machine (XPERT80; KUB Technologies Inc., Fairfield, CT) at 25 kV for 70 seconds. Upper limb vascular density (pixel density), vessel length (average length of vessels with diameter >1 pixel), and fractal dimension were analyzed by modified IMAGEJ and MATLAB software (Research Services Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD). A total of six mice per genotype were analyzed.

Postcontraction Hyperemia before Ischemia

Skeletal muscle contraction-stimulated hyperemia was determined as described previously.37 Briefly, anesthetized mice were placed on a heated surface and the gastrocnemius and adductor muscle group were exposed via a midline incision of the limb. Gastrocnemius muscle blood flow was measured at baseline (prestimulation), and followed by 2 minutes of stimulation of the adductor muscles with two electrodes at 2 Hz and 5 mA with the aid of an electrostimulator. Measurements were taken at baseline and at 1-minute intervals after stimulation and recorded by Matlab Chart (ADInstruments, Grand Junction, CO). A total of eight mice per time point per genotype were analyzed.

Muscle Protein Extract

Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, pulverized, and resuspended in lysis buffer containing: 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1 mmol/L Pefabloc SC, and 2 mg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN). The mixture was incubated 30 minutes at 4°C with inversion and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 14,000 rpm. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Mice were sacrificed at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after surgery, and muscles of the lower limb were harvested, fixed with zinc fixative, preserved, and embedded in paraffin to generate tissue sections (5 μm thick). Sections were stained using anti-PECAM-1/CD31 antibody (1:100 dilution; BD Bioscience-Pharmingen), anti-smooth muscle actin antibody (Ab15267, Abcam), anti-MMP-9 antibody (1:1000, Abcam), 7/4 neutrophil (1:400, Abcam), anti-ephrin B2 (1:100; Neuromics, Edina, MN) and anti-TSP2 antibody (1:1000, BD Bioscience). The bound primary antibodies were detected by using the peroxidase-based ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories). The sections were counterstained with 1% methylene green for 2 minutes and mounted. High-power (×40 objective) and low-power (×10 objective) images from three random areas of each section and two sections per muscle were taken using a Zeiss microscope equipped with a digital camera. Capillary density and collaterals were quantified by counting the number of blood vessels per field from high- and low-power images, respectively. A total of 40 images from six mice per genotype per time point were analyzed in a blind manner.

Western Blotting

Tissue homogenates (50 μg) were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Western blots for TSP2, MMP-2, and MMP-9 were performed according to standard protocols using anti-MMP-2 antibody (1:500; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) anti-MMP-9 antibody (1:5000, Abcam), and anti-TSP2 antibody (1:250, BD Bioscience). The membranes were developed using a luminol-based chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate kit. A total of five samples per genotype per time point were analyzed.

Gelatin Zymography

Protein extracts from ischemic and nonischemic muscle were analyzed by gelatin zymography as described previously.29 Briefly, 50 μg of protein were analyzed on an 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel containing 1 mg/ml of gelatin. After electrophoresis, gels were washed twice with 100 ml of 100 mmol/L NaCl and 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 to remove sodium dodecyl sulfate. The gels were then incubated at 37°C for 18 hours in 100 mmol/L NaCl and 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, supplemented with 10 mmol/L CaCl2, and subsequently stained with Coomassie Blue. Zones of proteolysis appeared as clear bands against a blue background. A total of five samples per genotype per time point were analyzed.

In Situ Zymography

Ischemic muscle tissues were embedded in OCT and used to generate 10-μm-thick cryostat sections. Sections were incubated with reaction buffer (0.05 mol/L Tris-HCl, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L CaCl2, and 0.l2 mmol/L NaN3, pH 7.6) containing 20 mg/ml fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled DQ gelatin (Molecular Probes) for 3 hours. Gelatinolytic activity was visualized by fluorescence microscopy and quantified as percent area per high-power field using Metamorph software (Molecular Dynamics). A total of 30 images from six mice per genotype were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical differences were measured by either Student’s t-test or one- or two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

TSP2 Modulates Gelatinase Activity and Inhibits Three-Dimensional Chord Formation

We hypothesized that TSPs function as matrix-associated proteins and interact with cells that are also engaged in interactions with the ECM. Thus, we proceeded to analyze the effects of TSP1 and TSP2 in a well-established three-dimensional assay of EC chord formation. Specifically, we suspended HDMECs or HUVECs in a solution of Matrigel and allowed them to form blood vessel-like chords. Inclusion of recombinant TSP2 in the system limited chord formation in Matrigel (Figure 1B) compared to control (Figure 1A). The inhibitory effect of TSP2 was observed in the range of 1 to 10 μg/ml. Inclusion of recombinant TSP1 (1 to 10 μg/ml) did not limit chord formation in either matrix (Figure 1C). Both recombinant and platelet-derived TSP1 failed to limit chord formation (not shown). Similar to TSP2, addition of 10 μmol/L GM6001, an inhibitor of MMP activity, reduced chord formation (Figure 1G). The ability of HUVECs to form chords in the presence of TSP1 or TSP2 was also evaluated in gels consisting of type I collagen (Vitrogen) supplemented with fibronectin and was found to be the same as in gels made of Matrigel (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Because we obtained similar results with both matrices, we opted to perform our subsequent studies in Matrigel. TSP2 was inhibitory for both HDMECs and HUVECs, but the former formed shorter chords and displayed less branching. Thus, we focused mainly on HUVECs because they were easier to obtain. Detailed morphometric analysis of images taken from the three-dimensional cultures using Metamorph software showed that TSP2 limited several parameters of the chord formation process. These included total chord length, total chord area, and number of segments. Mean chord length and thickness were not altered in the presence of TSP2 (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). More importantly, TSP2-treated gels did not display a reduction in cell number.

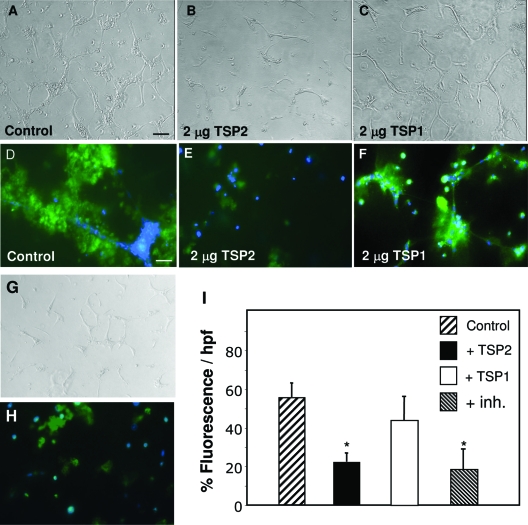

Figure 1.

TSP2-mediated inhibition of EC chord formation in a three-dimensional assay associated with reduced gelatinase activity. HUVECs were suspended in Matrigel supplemented with vehicle control (A), TSP2 (B), TSP1 (C), or GM6001 (G) and allowed to form chords for 24 hours. Representative fluorescent images of control (D), TSP2-treated (E), TSP1-treated (F), and GM6001-treated (H) gels supplemented with DQ gelatin for 24 hours. Green fluorescence is indicative of gelatinase activity. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Images were merged using ImagePro. Triplicate wells were used, and the experiment was repeated three times. I: Morphometric analysis of fluorescence intensity expressed as percentage fluorescence per hpf. *P ≤ 0.05. Scale bars: 50 μm (A–C, G); 25 μm (D–F, H).

During handling of the gels we made the empirical observation that gels containing TSP2 were stronger and somewhat stiffer. To test the hypothesis that this was attributable to reduced MMP activity, the experiments were repeated with gels that contained DQ gelatin, which is a fluorescence-emitting substrate for the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9. Morphometric evaluation of digital images of chord forming cells indicated that addition of 2 μg of TSP2 or GM6001 caused a reduction in fluorescence indicative of reduced gelatinase activity whereas addition of TSP1 did not have an effect and was indistinguishable from untreated cultures (control, 54.9 ± 7.6%; TSP2, 21.6 ± 5.7%*; TSP1, 43.13 ± 12.74%; GM6001, 18.03 ± 10.1%*; *P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 1, D–F, H, I).

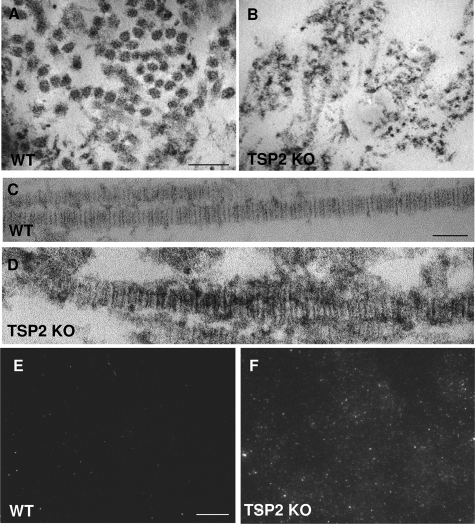

Because TSP2 is predominantly secreted by fibroblasts and seldom by ECs,21 we postulated that non-EC-derived ECM might influence ECs indirectly. We pursued this hypothesis by performing ultrastructural analysis of the ECM secreted and assembled by dermal fibroblasts from WT and TSP2-null mice. Transmission electron microscopic analysis of decellularized cultures revealed the lack of well-defined individual collagen fibrils and the presence of a loosely organized collagenous network in the TSP2-null ECM (Figure 2). Examination of individual collagen fibrils indicated abnormal periodicity and association with surrounding dense material lacking characteristics of collagen (compare Figure 2, C and D). Immunocytochemical analysis of decellularized chamber slides with HU177 antibody, which is specific for cryptic epitopes present only on partially degraded collagens, revealed a significant increase of these epitopes in TSP2-null-derived ECM (Figure 2, E and F). For all decellularization experiments the efficiency of cell removal and the presence of ECM was verified by the lack of positive stain with DAPI (nuclei), phalloidin (cytoskeleton), and the presence of fibronectin (see Supplemental Figure 1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 2.

Irregular collagen fibril assembly, enhanced degradation, and increased HUVEC migration in TSP2-null fibroblast-derived matrix. WT (A, C, E) and TSP2-null (B, D, F) dermal fibroblasts were grown in the presence of ascorbic acid for 7 days and the secreted matrix was analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (A–-D) and immunocytochemistry with HU177 antibody (E, F). WT matrix contained regular-shaped collagen fibrils that in cross section appeared to organize in bundles (A), whereas TSP2-null matrix contained irregular fibrils that lacked organization (B). D: Unlike WT fibrils that exhibited normal periodicity, fibrils in TSP2-null matrix lacked consistent periodicity and were surrounded by undefined material. The presence of cryptic collagen epitopes, detected by immunofluorescence, was minimal on WT-derived matrix (E) and prominent on TSP2-null matrix (F). Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bars: 50 nm (A, B); 25 nm (C, D); 50 μm (E, F).

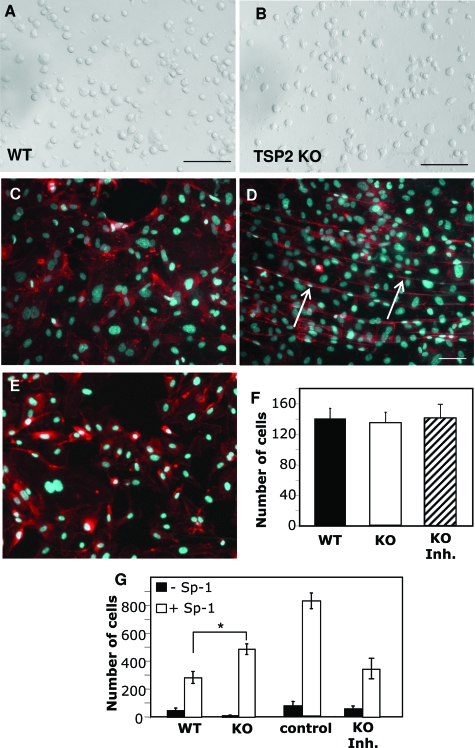

To test the hypothesis that alterations in the ECM could influence angiogenesis, we performed experiments involving ECs cultured on WT and TSP2-null fibroblast-derived ECM. In short term (1 hour) attachment assays, attachment and morphology of HUVECs were indistinguishable on the two matrices (Figure 3, A and B), as were cell numbers (Figure 3F). However, after 12 hours of incubation on TSP2-null ECM, HUVECs visualized by phalloidin (cytoskeleton) and DAPI (nuclei) displayed increased cellular organization that resembled primitive chord formation (Figure 3D) compared to WT (Figure 3C). In addition, such cellular organization was not observed on TSP2-null ECM-derived from cells cultured in the presence of GM6001 (Figure 3E). Furthermore, in a modified transwell migration assay, HUVECs displayed enhanced migration through TSP2-null-derived ECM in response to sphingosine-1-phosphate (TSP2-null, 64.5 ± 9.7%*; WT, 32 ± 13.7%; TSP2-null + GM6001, 42 ± 16.9%; values represent percentage in relation to uncoated transwells, *P ≤ 0.05) (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Normal attachment and altered EC function on TSP2-null fibroblast-derived ECM. HUVEC attachment, 1 hour after plating, on WT-derived (A) and TSP2-null-derived (B) was quantified as number of cells per field and found to be equal (F). HUVECs visualized by phalloidin and DAPI displayed chord-like formations (arrows in D) when plated on TSP2-null ECM (D) for 12 hours; WT shown in C. E: ECM derived from TSP2-null fibroblasts cultured in the presence of GM6001 failed to induce chord-like formations. G: Migration in response to sphingosine-1-phosphate was significantly enhanced in wells coated with TSP2-null ECM in comparison to WT or TSP2-null ECM from GM6001-treated cells. Control in F represents migration of HUVECs in uncoated wells (n = 5 in quadruplicate wells). *P ≤ 0.05. Scale bars = 50 μm.

TSP2 Is Highly Induced in Ischemic Hind Limbs

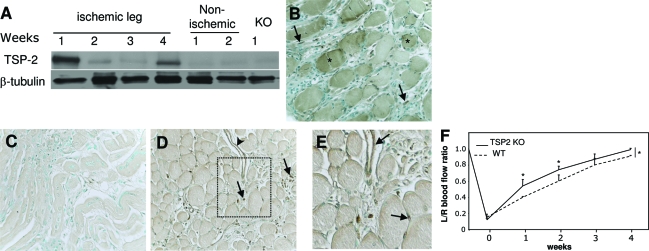

To determine the role of TSP2 in limb ischemia, we first examined TSP2 protein expression in response to ischemic injury in the mouse hindlimb model induced by surgical arteriectomy of the left femoral artery. Protein extracts from the upper (thigh) and lower (calf) limbs of the ischemic (left) and nonischemic (right) legs were prepared at time 0 and on weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 after surgery, and the expression of TSP2 was determined by Western blotting with anti-TSP2 antibody. TSP2 was highly induced in the lower limb after ischemia at 1 week (Figure 4A). Subsequently, the levels dropped at 2 and 3 weeks and increased again at 4 weeks. The biphasic expression of TSP2 was confirmed in two independent experiments. In contrast to the high expression of TSP2 in ischemic tissues, nonischemic muscle contained almost no detectable TSP2. As expected, TSP2 was not detected in any of the TSP2-null preparations. Because of the biphasic expression pattern of TSP2, we examined the spatial deposition of TSP2 in ischemic tissues by immunohistochemistry with an anti-TSP2 antibody. We found that at 1 week, TSP2 was predominantly present in muscle fibers and in the ECM and cells within the interstitial space (Figure 4B). Double immunostaining with endothelial- and smooth muscle-specific antibodies revealed no co-localization of TSP2 with these cells at this time point (not shown). We presume that at this stage, TSP2 is expressed mainly by muscle cells and fibroblasts, and thus influences angiogenesis in a paracrine manner. Deposition at 2 weeks was diffuse and did not show extensive association with any cellular elements (Figure 4C). At 4 weeks, the deposition of TSP2 was somewhat elevated in muscle fibers, but was more pronounced in cells present in the interstitial space and in blood vessels (Figure 4, D and E). Thus, the biphasic deposition of TSP2 in ischemic tissues can contribute to early tissue remodeling events and to late tissue homeostasis.

Figure 4.

Increased TSP2 expression in ischemic muscle and improved ischemia-initiated blood flow recovery in TSP2-null mice. A: Western blot analysis of protein extracts from ischemic and nonischemic muscle. The KO sample is shown as a negative control. A β-tubulin blot is shown as loading control. Analysis was repeated three times with similar results. B–D: Representative sections of muscles from WT mice at 1 (B), 2 (C), and 4 (D) weeks after surgery stained with an anti-TSP2 antibody and visualized with the peroxidase reaction (brown color). Asterisks in B denote muscle fibers. Arrows in B and D denote interstitial cells and arrowhead in D denotes a TSP2-positive blood vessel. E: Enlarged image of the rectangular area in D. Arrows denote TSP2-immunoreactive blood vessels. Nuclei were counterstained with methyl green. F: Blood flow in the gastrocnemius muscle of 3-month-old mice was measured at 1 to 4 weeks using deep penetrating laser Doppler probe and expressed as the ratio of the left limb (ischemic) relative to the right limb (nonischemic). *P ≤ 0.05. n = 6. Original magnifications, ×400 (B–D).

Enhanced Blood Flow Recovery in TSP2-Null Mice

To investigate the significance of TSP2 in the functional recovery from limb ischemia, WT and TSP2-null mice were subjected to femoral artery ligation and the blood flow was measured at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after surgery by using a deep-penetrating laser Doppler probe placed directly onto the gastrocnemius muscle. Before surgery, the ratio of blood flow between the ischemic (left) and nonischemic (right) legs was 1. Consistent with a complete arteriectomy, blood flow dropped by 80% in both WT and TSP2-null mice immediately after surgery (time 0; Figure 4F). However, recovery of flow was greater in TSP2-null mice at 1 and 2 weeks, suggesting that TSP2 plays a necessary role in reducing the rate of recovery. Both WT and TSP2-null mice displayed near complete recovery of flow within 4 weeks. However, the overall rate of recovery was augmented in TSP2-null mice.

Enhanced Arteriogenesis and Ischemic Reserve Capacity in TSP2-Null Mice

Enhanced limb perfusion could be attributable to increased arteriogenesis from existing vessels in the upper limb. Thus, we examined ischemia-initiated arteriogenesis at 2 weeks after ischemia in WT and TSP2-null mice by quantitative angiography in the presence of vasodilators (Figure 5). Specifically, the degree of branching (fractal dimension; Figure 5, A–C) and the average vessel area (Figure 5D) and length (Figure 5E) were determined. Remarkably, compared with WT mice, baseline arteriogenesis was greater in TSP2-null mice (Figure 5, D and E). Both the average vessel area and length were increased whereas the fractal dimension was similar to that of WT, suggesting that the increase in arterial dimensions was not attributable to changes in branching patterns. After 2 weeks of limb ischemia, arteriogenesis increased in WT mice, but not in TSP2-null mice. Thus, the lack of TSP2 appears to influence the baseline arteriogenesis in muscle tissue and this high level of arteriolization in nonischemic muscle was not further enhanced in TSP2-null ischemic muscle. To further confirm the presence of an enhanced arterial network, the number of collaterals was determined from sections of uninjured muscles from WT (Figure 5F) and TSP2-null (Figure 5G) mice, stained with anti-smooth muscle actin antibody, and was found to be higher in the latter (3.8 ± 1.3 versus 6.5 ± 2.2; P ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, ephrinB2 immunostain confirmed the arterial identity of the enhanced network (Figure 5, H and I).

Figure 5.

Increased arteriogenesis and hyperemia in TSP2-null mice. Arterial phase angiograms from WT and TSP2-null mice were analyzed. Representative images demonstrating the perfusion of WT (A) and TSP2-null (B) nonischemic muscle; quantification of fractal dimension is shown in C. Quantitative image analysis revealed that the latter displayed an increase in vessel area (D) and vessel length (E). Smooth muscle actin-positive and ephrin B2-positive vessels in WT (F, H) and TSP2-null (G, I) nonischemic muscle were visualized by immunohistochemistry. J: The adductor muscle groups of mice were electrostimulated, and the increase in gastrocnemius blood flow was recorded. TSP2-null mice showed increased peak blood flow and delayed return to baseline levels. Data are mean values ± SD. #Comparison between left and right leg within groups. *Comparison between groups. P ≤ 0.05. n = 6 (A–E); n = 8 (F).

The increase in baseline arteriogenesis in TSP2-null limbs suggested that in these mice the ability to use pre-existing collaterals to supply blood flow to the lower leg after ischemia is enhanced. To investigate this possibility, we examined skeletal muscle contraction-stimulated hyperemia in the gastrocnemius muscle in WT and TSP2-null mice at baseline. Electrical stimulation of the adductor muscle groups in the upper leg resulted in a marked increase in peak blood flow in the gastrocnemius muscle group of both strains (Figure 5J). However, in comparison to WT, the increase in TSP2-null mice was greater, suggesting that TSP2 functions as a critical regulator of the vasodilation necessary for the gradual return of blood flow back to normal levels. Taken together, our observations of increased baseline arteriogenesis and ischemic reserve capacity indicate that TSP2-null mice possess an enlarged and properly functioning network of collaterals in the limb.

Ischemia-Induced Angiogenesis Is Enhanced in TSP2-Null Mice

In the model of hindlimb ischemia, changes in the perfusion of the upper limb induce physiological angiogenesis in the lower limb. Thus, we examined tissue sections from the ischemic and nonischemic gastrocnemius muscles by immunohistochemistry with anti-CD31 (PECAM-1) antibody to determine the extent of angiogenesis in WT and TSP2-null tissues (Figure 6, A–D). Overall capillary densities in nonischemic muscle were similar between the two mouse groups (Figure 6E, time 0), however, ischemia-induced angiogenesis was evident in both groups but was greatly enhanced in TSP2-null muscle. Specifically, quantification of the number of blood vessels indicated enhanced angiogenesis in both WT and TSP2-null mice with the latter having significantly more vessels 1 to 3 weeks after surgery (Figure 6E). Determination of the capillary/fiber ratio established that the increase in angiogenesis was not attributable to alterations in muscle fiber regeneration, with the exception of the 4 weeks time point in which, unlike WT, TSP2-null mice had a higher ratio of vessels to fibers (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Increased angiogenesis in TSP2-null ischemic muscle. Representative sections of nonischemic (A, C) and 1-week ischemic (B, D) muscles from WT (A, B) and TSP2-null (C, D) mice 2 weeks after surgery, stained for PECAM-1 and visualized with the peroxidase reaction (brown color). Nuclei were counterstained with methyl green. E: Quantification of capillaries indicated that TSP2-null muscle was excessively vascularized at 1 and 2 weeks after surgery. F: The ratio of capillaries to muscle fibers was evaluated. For each genotype, a total of 40 images from six samples per time point were analyzed. #Comparison between WT samples at 1 to 4 weeks and WT time 0. *Comparison for each time point between WT and TSP2 KO samples. P ≤ 0.05. Original magnifications, ×400.

Enhanced Expression of MMP-9 in TSP2-Null Mice

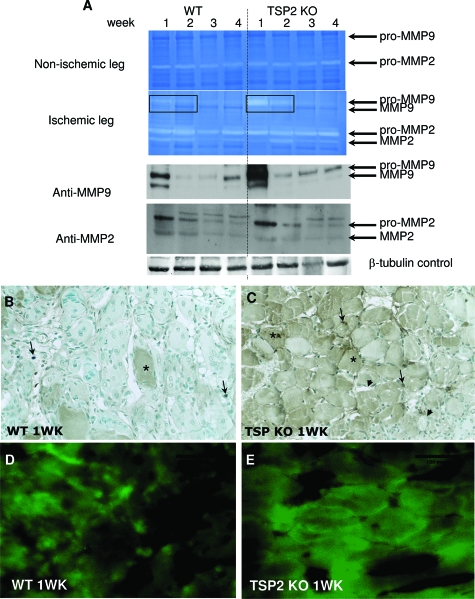

To examine whether the levels of MMPs were altered during ischemia in TSP2-null mice, protein extracts from the lower ischemic and nonischemic limbs were analyzed by gelatin zymography and Western blot. Nonischemic tissues displayed very low levels of pro-MMP-9 and somewhat higher levels of pro-MMP-2, both of which remained unaltered during the experiment (Figure 7A, top). Both pro- and activated MMP-2 were detected in ischemic muscle extracts, with maximum expression observed at 1 week in both WT and TSP2-null samples. Overall, the levels of MMP-2 did not differ significantly between the two groups. On the other hand, pro-MMP-9 was strongly induced in TSP2-null ischemic muscle and the levels were significantly higher than WT. Interestingly, the levels of MMP-9 in WT ischemic muscles peaked at 1 week, decreased between 2 to 3 weeks, and increased again at 4 weeks in a pattern that mirrored that of TSP2. The identity of the various gelatinolytic bands in ischemic muscles was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 7A, bottom). The distribution of MMP-9 was examined by immunohistochemistry at 1 week after ischemia and found to be predominantly associated with cells in the interstitial space and some muscle fibers (Figure 7B). Increased deposition of MMP-9 in muscle fibers was observed in TSP2-null tissues (Figure 7C). Analysis of neutrophil infiltration in 1-week ischemic muscles revealed similar levels between WT and TSP2-null samples (34.4 ± 5.8 cells/hpf for WT versus 30.77 ± 9.6 cells/hpf for TSP2-null), suggesting that the increase in MMP-9 deposition was not attributable to differences in inflammation (see Supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). To directly evaluate the presence of proteolytically active gelatinases, we performed in situ zymography on cryosections from 1-week WT and TSP2-null ischemic muscle (Figure 7, D and E). Consistent with our other analyses, image analysis of sections with Metamorph software, indicated significantly elevated gelatinolytic activity in TSP2-null muscle (56.5 ± 6.9% area) in comparison to WT (31.3 ± 11.4% area; P ≤ 0.05, n = 6). Because we found the levels of MMP-2 to be similar between the two groups, we believe that the increase is predominantly attributable to elevated activity of MMP-9.

Figure 7.

Increased MMP-9 levels in TSP2-null ischemic muscle. A: Representative zymogram of muscle protein extracts from nonischemic (top) and ischemic (bottom) from 1 to 4 weeks WT and TSP2-null (KO) mice. Western blot analysis of ischemic muscles for MMP-2 and MMP-9 is shown. Loading was controlled by blotting for β-tubulin as shown. Results are representative of five animals per time point for each group. B and C: Representative sections from 1-week WT ischemic (B) and TSP2-null (C) muscle stained with anti-MMP-9 antibody and visualized with the peroxidase reaction (brown color) are shown. Asterisks in B and C denote muscle fibers, arrows denote interstitial cells. Arrowheads in C denote nonimmunoreactive blood vessels. Nuclei were counterstained with methyl green. D--E: Representative images of sections from 1-week WT ischemic (D) and TSP2-null (E) muscle subjected to in situ zymography with DQ gelatin to detect gelatinolytic activity. Original magnifications, ×400.

Discussion

In the present study we show that TSP2 can inhibit three-dimensional angiogenesis by limiting the gelatinolytic activity of ECs, suggesting that it can limit their ability to modulate their extracellular microenvironment. In addition, we show irregular assembly of the ECM made by TSP2-null fibroblasts, which renders it more permissive for EC assembly and migration. The ability of TSP2 to alter EC remodeling and the TSP2-null ECM to alter EC migration was found to be associated with decreased and increased MMP-2/9 activity, respectively. Consistent with these observations, inclusion of a MMP inhibitor reproduced the effect of TSP2 on HUVEC chord formation and altered the properties of TSP2-null-derived ECM. Furthermore, TSP2-null mice displayed accelerated recovery of blood flow after hindlimb ischemia attributable to increased baseline arteriogenesis and ischemia-induced angiogenesis. Multiple analyses confirmed that the activity of a gelatinase, MMP-9, was increased during the recovery from ischemia in TSP2-null mice.

TSP2 and Three-Dimensional Angiogenesis

Our observations in the three-dimensional angiogenesis assay indicate that TSP2 can influence the ability of HUVECs to form networks. The observed reduction in gelatinolytic activity indicates that TSP2 can limit the ability of cells to degrade the surrounding ECM. Because TSP1 did not inhibit angiogenesis in this model and HUVECs do not express CD36, we presume that the effect of TSP2 is independent of binding to common receptors such as CD47, LRP, and very low-density lipoprotein receptor. Conceivably, access of TSPs to these receptors is limited when ECs are embedded in a three-dimensional ECM. More importantly, we show that TSP2 can influence the ability of HUVECs to form vascular-like networks in three-dimensional culture, whereas previous studies have shown that TSP2 could not inhibit growth factor-induced proliferation in HUVECs in conventional culture.9 Based on our observations we suggest that previous interpretations regarding the anti-angiogenic activity of TSPs might not be complete. In our opinion, in vitro examination of EC function should be expanded to include three-dimensional assays. In fact, a discrepancy was recently identified regarding the angiogenic activity of IL-20, prompting the investigators to suggest that vascular remodeling should be assayed only in three-dimensional culture and in vivo models.38 It should be noted however, that we have not excluded the possibility that the effect of TSP2 might be mediated by a unique, not yet identified, TSP2 receptor. Nevertheless, we think it is more likely that the ECM-modifying property of TSP2 plays a significant role in limiting angiogenesis.

Our in vitro studies suggest that TSP2 can influence EC function in at least two ways. First, as discussed above, by modulating the abilities of ECs to remodel the surrounding ECM and second, by rendering non-EC-derived ECM anti-angiogenic. Both mechanisms rely on the ability of TSP2 to lower the levels of MMPs leading to increased ECM integrity. The complexity of the mechanism through which TSP2 modulates the ECM has been partially elucidated in dermal fibroblasts where we have shown that TSP2-null cells have elevated levels of MMP-2 and reduced cross-linking of the ECM because of reduced levels of tissue transglutaminase.29,39 This finding is also consistent with our previous observations in TSP2-null mice in which we reported irregular collagen fibrillogenesis in connective tissues and elevated levels of MMP-2 in skin wounds.40,41 The latter observation was made in aged TSP2-null mice, which displayed improved healing. Recently, we were able to detect increased levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 and soluble VEGF in the wounds of young TSP2-null mice (T.R. Kyriakides et al, submitted). More importantly, EC proliferation and apoptosis were similar in the wounds of TSP2-null and WT mice, suggesting the regulation of angiogenesis via a novel mechanism.

TSP2 Modulation of the ECM and Vascular Remodeling

Consistent with an increase in MMPs, we observed irregular collagen fibrillogenesis and increased degradation of TSP2-null-derived ECM. The latter was detected by the appearance of neo-epitopes that are associated with degraded collagen. Interestingly, the appearance of these epitopes was reduced in the ischemic muscles of MMP-9-null mice, implicating MMP-9 in their generation in vivo.42 Furthermore, MMP-2-null and MMP-9-null mice display compromised recovery from ischemia.43,44,45 To expand on our observations in vitro, we used the hindlimb ischemia model to compare the response between TSP2-null and WT mice. The observation of reduced HU177-positive epitopes in MMP-9-null ischemic muscle, served as a major impetus for our study. Furthermore, the model provided us with the opportunity to investigate the participation of TSP2 in arteriogenesis in the upper limb and physiological angiogenesis in the lower limb, processes in which TSP2 had not been previously implicated. We found that TSP2 expression in the lower limb is highly induced by a disruption of blood flow in a biphasic manner and plays a role in limiting ischemia-induced angiogenesis. The latter conclusion was supported by a pronounced increase in angiogenesis in TSP2-null mice. In addition, we found that baseline arteriogenesis was enhanced, providing the first evidence for an association of TSP2 with this process. Even though we were unable to detect TSP2 in noninjured muscles, our finding is not unprecedented because we have previously shown abnormalities in the skin of TSP2-null mice, such as irregular collagen fibrillogenesis and reduced tensile strength, despite the absence of detectable TSP2 expression.40

It has been shown that collateral vessel development plays an important role in the restoration of distal blood flow and tissue salvage in a number of physiological and clinical settings.46 The importance of pre-existing collaterals has been suggested by studies in pigs and dogs, in which the initial collateral-dependent perfusion after coronary artery occlusion correlated with final recovery of perfusion.47 Mechanistically, ischemia-induced vascular remodeling is known to involve the following steps: hypoxia-induced activation of vascular ECs, release of inflammatory and proangiogenic factors, arterialization of preformed collaterals (arteriogenesis) in the upper limb, and capillary angiogenesis in the lower limb. Defects in these steps could lead to failure to recover blood flow to tissue and functional limb salvage.33,34 In the present study, differences in preexistent collateral vasculature can strongly impact the milieu for growing collateral vessels as demonstrated by the dramatic differences in the recovery of blood flow between WT and TSP2-null mice. In addition, the increased vessel density in TSP2-null mice is consistent with previous reports of increased angiogenesis in models of skin injury, skin tumor growth, and corneal wound healing.12,23,48 Interestingly, a recent study of a strain of hypertensive rats revealed an association between increased levels of TSP2 and progression to heart failure.30 Thus, TSP2 was implicated as a modulator of cardiac remodeling and in the same study elevated levels of MMP-9 were observed after cardiac infarct in TSP2-null mice.

Modulation of MMP Levels by TSP2

At this time we have no explanation for the selective effect of TSP2 on MMP-9 in limb ischemia, but our findings are consistent with the infarct model discussed above. Our in vitro studies indicate that TSP2 can alter the levels of MMP-2 in dermal fibroblasts and MMP-9 in ECs, but neither cell type expresses both gelatinases. In dermal fibroblasts, TSP2 can bind MMP-2 to form a complex that is then endocytosed by LRP-1.31 Additional evidence for this interaction has been found in the microvasculature of tumors propagated in mouse brain where LRP-1, TSP2, and MMP-2 have been co-localized.49 In addition, MMP-2 and MMP-9 has been shown to bind TSP2 in an in vitro binding assay.50 Thus, it is possible that direct interaction between TSP2 and MMPs can lead to alterations in the levels of these enzymes in the extracellular milieu and modulate angiogenesis. MMPs are thought to promote angiogenesis by proteolysis of the endothelial basement membrane, thus facilitating EC sprouting and invasion. In addition, MMP-9 has been shown to modulate the availability of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a pro-angiogenic growth factor.51,52 Interestingly, in a mammary tumor model, the absence of TSP1 resulted in increased association of VEGF with its receptor VEGFR2 and higher levels of active MMP-9.53 Conceivably, a TSP-MMP-soluble VEGF axis could modulate ischemia-induced angiogenesis.

The spatial and biphasic temporal expression of TSP2 during ischemia in the lower limb suggests that TSP2 participates in the early remodeling and late resolution events in muscle. In fact, immunohistochemistry revealed extensive TSP2 deposition in muscle fibers at 1 week. Furthermore, the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are also elevated at this time point, suggesting that their expression is similar to that of TSP2. In addition, the deposition of MMP-9 in TSP2-null tissues mirrors that of TSP2 in the WT (compare images in Figures 4B and 7C). Because TSP2 is not made by ECs in the early response to ischemia, we postulate that its effect is predominantly to modulate ECM remodeling and influence EC function in a paracrine manner. During the late response to ischemia, TSP2 is highly expressed in blood vessels and interstitial fibroblasts, and could contribute to their stabilization by decreasing ECM turnover. However, it is unclear at this time whether either ECs or pericytes or both express TSP2 in vessels. Nevertheless, the strong association of TSP2 with blood vessels suggests its involvement in their function.

A recent analysis of the ischemic response in double-TSP1/TSP2-null mice showed results consistent with the phenotype of TSP2-null mice and proposed a mechanism by which the deficiency in TSPs confers a pro-angiogenic phenotype through increased MMPs.26 Because the phenotype was transferable by bone marrow transplantation, a hypothesis was proposed that involved the participation of MMP-9-mediated platelet mobilization and platelet-derived TSPs in regulating ischemia-induced angiogenesis. In fact, evidence was presented for increased MMP-9-dependent platelet production after ischemia in double-TSP1/TSP2-null mice. However, we have shown that even though megakaryocytes contain TSP2, platelets do not,27 suggesting that the introduction of WT bone marrow into double-null mice reintroduces only TSP1 in circulating platelets. Furthermore, we have also shown that TSP2-null platelets have an inherent aggregation defect.27 In addition, a recent report showed that TSP1-null platelets fail to aggregate in response to thrombin in the presence of exogenous NO.54 Thus, reintroduction of double-null platelets in WT mice might have produced results that are more relevant in the context of suboptimal platelet activation. Nevertheless, our studies in TSP2-null mice are conceptually consistent with the overall improvement in recovery after ischemia, the increased angiogenesis, and the elevated levels of MMP-9.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tom Wight (Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, WA) for helpful discussions, Dr. Peter Brooks (New York University, New York, NY) for provision of the HU177 antibody, and Anush Oganesian and Yumiko Adachi for preparation of recombinant TSP2.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Themis R. Kyriakides, Ph.D., Departments of Pathology and Biomedical Engineering, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06536-9812. E-mail: themis.kyriakides@yale.edu.

Supported by the National Institute of Health (grant GM 072194-01 to T.R.K.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp. amjpathol.org.

References

- Adams JC. Thrombospondins: multifunctional regulators of cell interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:25–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P. Thrombospondins as matricellular modulators of cell function. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:929–934. doi: 10.1172/JCI12749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruela-Arispe ML, Luque A, Lee N. Thrombospondin modules and angiogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P, Devarayalu S, Li P, Disteche CM, Framson P. A second thrombospondin gene in the mouse is similar in organization to thrombospondin 1 but does not respond to serum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8636–8640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P, O'Rourke K, Wikstrom K, Wolf FW, Katz R, Li P, Dixit VM. A second, expressed thrombospondin gene (Thbs2) exists in the mouse genome. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:12821–12824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Strickland DK, Mosher DF. Metabolism of thrombospondin 2. Binding and degradation by 3t3 cells and glycosaminoglycan-variant Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15993–15999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.15993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Sottile J, O'Rourke KM, Dixit VM, Mosher DF. Properties of recombinant mouse thrombospondin 2 expressed in Spodoptera cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32226–32232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JC, Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oganesian A, Armstrong LC, Migliorini MM, Strickland DK, Bornstein P. Thrombospondins use the VLDL receptor and a non-apoptotic pathway to inhibit cell division in microvascular endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:563–571. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good DJ, Polverini PJ, Rastinejad F, Le Beau MM, Lemons RS, Frazier WA, Bouck NP. A tumor suppressor-dependent inhibitor of angiogenesis is immunologically and functionally indistinguishable from a fragment of thrombospondin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6624–6628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J. Thrombospondin-1 as an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cursiefen C, Masli S, Ng TF, Dana MR, Bornstein P, Lawler J, Streilein JW. Roles of thrombospondin-1 and -2 in regulating corneal and iris angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1117–1124. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Lawler J. Thrombospondin-based antiangiogenic therapy. Microvasc Res. 2007;74:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpert OV, Stellmach V, Bouck N. The modulation of thrombospondin and other naturally occurring inhibitors of angiogenesis during tumor progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;36:119–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00666034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panetti TS, Chen H, Misenheimer TM, Getzler SB, Mosher DF. Endothelial cell mitogenesis induced by LPA: inhibition by thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-2. J Lab Clin Med. 1997;129:208–216. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Gurusiddappa S, Frazier WA, Hook M. Heparin-binding peptides from thrombospondins 1 and 2 contain focal adhesion-labilizing activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26784–26789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Hook M. Thrombospondin modulates focal adhesions in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1309–1319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Pearce SF, Zhong R, Silverstein RL, Frazier WA, Bouck NP. CD36 mediates the in vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:707–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez B, Volpert OV, Crawford SE, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, Bouck N. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat Med. 2000;6:41–48. doi: 10.1038/71517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simantov R, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. The antiangiogenic effect of thrombospondin-2 is mediated by CD36 and modulated by histidine-rich glycoprotein. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong LC, Bjorkblom B, Hankenson KD, Siadak AW, Stiles CE, Bornstein P. Thrombospondin 2 inhibits microvascular endothelial cell proliferation by a caspase-independent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1893–1905. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E01-09-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agah A, Kyriakides TR, Lawler J, Bornstein P. The lack of thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) dictates the course of wound healing in double-TSP1/TSP2-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:831–839. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides TR, Tam JW, Bornstein P. Accelerated wound healing in mice with a disruption of the thrombospondin 2 gene. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:782–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg JS, Romeo MJ, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Oldenborg A, Pappan L, Wink DA, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Increasing survival of ischemic tissue by targeting CD47. Circ Res. 2007;100:602–613. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259579.35787.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg JS, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Romeo MJ, Abu-Asab M, Tsokos M, Kuppusamy P, Wink DA, Krishna MC, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 limits ischemic tissue survival by inhibiting nitric oxide-mediated vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Blood. 2007;109:1945–1952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp HG, Hooper AT, Broekman MJ, Avecilla ST, Petit I, Luo M, Milde T, Ramos CA, Zhang F, Kopp T, Bornstein P, Jin DK, Marcus AJ, Rafii S. Thrombospondins deployed by thrombopoietic cells determine angiogenic switch and extent of revascularization. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3277–3291. doi: 10.1172/JCI29314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides TR, Rojnuckarin P, Reidy MA, Hankenson KD, Papayannopoulou T, Kaushansky K, Bornstein P. Megakaryocytes require thrombospondin-2 for normal platelet formation and function. Blood. 2003;101:3915–3923. doi: 10.1182/blood.V101.10.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides TR, Zhu YH, Yang Z, Huynh G, Bornstein P. Altered extracellular matrix remodeling and angiogenesis in sponge granulomas of thrombospondin 2-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1255–1262. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62512-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Kyriakides TR, Bornstein P. Matricellular proteins as modulators of cell-matrix interactions: adhesive defect in thrombospondin 2-null fibroblasts is a consequence of increased levels of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3353–3364. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroen B, Heymans S, Sharma U, Blankesteijn WM, Pokharel S, Cleutjens JP, Porter JG, Evelo CT, Duisters R, van Leeuwen RE, Janssen BJ, Debets JJ, Smits JF, Daemen MJ, Crijns HJ, Bornstein P, Pinto YM. Thrombospondin-2 is essential for myocardial matrix integrity: increased expression identifies failure-prone cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004;95:515–522. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141019.20332.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Strickland DK, Bornstein P. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase 2 levels are regulated by the low density lipoprotein-related scavenger receptor and thrombospondin 2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8403–8408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters RE, Terjung RL, Peters KG, Annex BH. Preclinical models of human peripheral arterial occlusive disease: implications for investigation of therapeutic agents. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:773–780. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00107.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil M, Schaper W. Cellular mechanisms of arteriogenesis. EXS. 2005;94:181–191. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7311-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil M, Schaper W. Influence of mechanical, cellular, and molecular factors on collateral artery growth (arteriogenesis). Circ Res. 2004;95:449–458. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141145.78900.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Rodriguez D, Kim JJ, Brooks PC. Generation of monoclonal antibodies to cryptic collagen sites by using subtractive immunization. Hybridoma. 2000;19:375–385. doi: 10.1089/02724570050198893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackah E, Yu J, Zoellner S, Iwakiri Y, Skurk C, Shibata R, Ouchi N, Easton RM, Galasso G, Birnbaum MJ, Walsh K, Sessa WC. Akt1/protein kinase Balpha is critical for ischemic and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2119–2127. doi: 10.1172/JCI24726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, deMuinck ED, Zhuang Z, Drinane M, Kauser K, Rubanyi GM, Qian HS, Murata T, Escalante B, Sessa WC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is critical for ischemic remodeling, mural cell recruitment, and blood flow reserve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10999–11004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501444102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritsaris K, Myren M, Ditlev SB, Hubschmann MV, van der Blom I, Hansen AJ, Olsen UB, Cao R, Zhang J, Jia T, Wahlberg E, Dissing S, Cao Y. IL-20 is an arteriogenic cytokine that remodels collateral networks and improves functions of ischemic hind limbs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15364–15369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707302104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agah A, Kyriakides TR, Bornstein P. Proteolysis of cell-surface tissue transglutaminase by matrix metalloproteinase-2 contributes to the adhesive defect and matrix abnormalities in thrombospondin-2-null fibroblasts and mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62955-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides TR, Zhu YH, Smith LT, Bain SD, Yang Z, Lin MT, Danielson KG, Iozzo RV, LaMarca M, McKinney CE, Ginns EI, Bornstein P. Mice that lack thrombospondin 2 display connective tissue abnormalities that are associated with disordered collagen fibrillogenesis, an increased vascular density, and a bleeding diathesis. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:419–430. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agah A, Kyriakides TR, Letrondo N, Bjorkblom B, Bornstein P. Thrombospondin 2 levels are increased in aged mice: consequences for cutaneous wound healing and angiogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2004;22:539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne PJ, Tihonov N, Li X, Glaser J, Qiao J, Silberstein M, Yee H, Gagne E, Brooks P. Temporal exposure of cryptic collagen epitopes within ischemic muscle during hindlimb reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1349–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61222-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, Sung HJ, Lessner SM, Fini ME, Galis ZS. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for adequate angiogenic revascularization of ischemic tissues: potential role in capillary branching. Circ Res. 2004;94:262–268. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111527.42357.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XW, Kuzuya M, Nakamura K, Maeda K, Tsuzuki M, Kim W, Sasaki T, Liu Z, Inoue N, Kondo T, Jin H, Numaguchi Y, Okumura K, Yokota M, Iguchi A, Murohara T. Mechanisms underlying the impairment of ischemia-induced neovascularization in matrix metalloproteinase 2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2007;100:904–913. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260801.12916.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XW, Kuzuya M, Nakamura K, Maeda K, Tsuzuki M, Kim W, Sasaki T, Liu Z, Inoue N, Kondo T, Jin H, Numaguchi Y, Okumura K, Yokota M, Iguchi A, Murohara T. Mechanisms underlying the impairment of ischemia-induced neovascularization in matrix metalloproteinase 2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2007;100:904–913. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260801.12916.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M. Angiogenesis: where do we stand now? Circulation. 2005;111:1556–1566. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159345.00591.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helisch A, Schaper W. Arteriogenesis: the development and growth of collateral arteries. Microcirculation. 2003;10:83–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawighorst T, Velasco P, Streit M, Hong YK, Kyriakides TR, Brown LF, Bornstein P, Detmar M. Thrombospondin-2 plays a protective role in multistep carcinogenesis: a novel host anti-tumor defense mechanism. EMBO J. 2001;20:2631–2640. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears CY, Grammer JR, Stewart JE, Jr, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Bornstein P, Gladson CL. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein contributes to the antiangiogenic activity of thrombospondin-2 in a murine glioma model. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9338–9346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bein K, Simons M. Thrombospondin type 1 repeats interact with matrix metalloproteinase 2. Regulation of metalloproteinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32167–32173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K, Tanzawa K, Thorpe P, Itohara S, Werb Z, Hanahan D. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:681–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Lane TF, Ortega MA, Hynes RO, Lawler J, Iruela-Arispe ML. Thrombospondin-1 suppresses spontaneous tumor growth and inhibits activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and mobilization of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12485–12490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171460498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg JS, Romeo MJ, Yu C, Yu CK, Nghiem K, Monsale J, Rick ME, Wink DA, Frazier WA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 stimulates platelet aggregation by blocking the anti-thrombotic activity of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling. Blood. 2008;111:613–623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]