Abstract

Keratins 6a and b (K6a, K6b) belong to a subset of keratin genes with constitutive expression in epithelial appendages, and inducible expression in additional epithelia, when subjected to environmental challenges or disease. Mutations in K6a or K6b cause a broad spectrum of epithelial lesions that differentially affect nail, hair, and glands in humans. Some lesions reflect a loss of the structural support function shared by K6, other keratins, and intermediate filament proteins. The formation of sebaceous gland-derived epithelial cysts does not fit this paradigm, raising the question of the unique functions of different K6 isoforms in this setting. Here, we exploit a mouse model of constitutively expressed Gli2, a Hedgehog (Hh) signal effector, to show that K6a expression correlates with duct fate in sebaceous glands (SGs). Whether in the setting of Gli2 transgenic mice skin, which develops a prominent SG duct and additional pairs of highly branched SGs, or in wild-type mouse skin, K6a expression consistently coincides with Hh signaling in ductal tissue. Gli2 expression modestly transactivates a K6a promoter-driven reporter in heterologous systems. Our findings thus identify K6 as a marker of duct fate in SGs, partly in response to Hh signaling, with implications for the pathological expansion of SGs that arises in the context of certain keratin-based diseases and related disorders.

Genetically determined mutations in individual intermediate filament protein-encoding genes account for, or are associated with, more than 70 distinct human disorders.1 These disorders tend to be individually rare but collectively affect a broad range of tissues, reflecting the tissue- and cell type-specific transcriptional regulation of intermediate filament genes.1,2,3 For several of these disorders, at least part of the underlying pathophysiology involves the expression of cellular fragility following exposure to mechanical trauma, brought about by a partial loss of the structural support function provided by intermediate filament polymers. There are, however, many examples of lesions that do not fit the classical paradigm of trauma-induced cell lysis; whether the newly emerging, non-mechanical functions of intermediate filament proteins4,5 are compromised in such settings is unknown.

A group of four keratin genes, the type II keratin paralogs 6a and 6b (K6a, K6b), and type I keratins 16 and 17 (K16 and K17), show an intriguing regulation comprising a constitutive component in all major types of epithelial appendages (eg, hair, nail, glands) and an inducible component that either follows a “challenge” (eg, injury, infection) or mirrors an ongoing pathology (eg, psoriasis, carcinoma).6,7 Unlike several other keratin pairings, the expression of K6a, K6b, K16, and K17 does not correlate with execution of a specific program of terminal differentiation.6,8,9 Several functions have been associated with these keratins from the study of various types of genetically modified mice, including structural support,10,11 modulation of keratinocyte migration,12,13,14 of tumor necrosis factor-α-induced apoptosis (for K17)15 and of protein synthesis.16 Conversely, small mutations in these keratin genes act dominantly to produce an unusually broad spectrum of epithelial lesions resembling ectodermal dysplasias,17 and which predominantly affect one or many epithelial appendages. These disorders (and the affected target proteins) include type I (K6a, K16) and type 2 (K6b, K17) pachyonychia congenita, steatocystoma multiplex (K17), and two palmoplantar keratoderma variants (K16) (see Human Intermediate Filament Database, http://www.interfil.org/)1,3 There is pronounced phenotypic heterogeneity among these conditions, and many aspects of their pathophysiology cannot be readily explained through a loss of structural support in the relevant epithelial cell population(s).3,7,18

A puzzling element that is frequently (>50%) associated with mutations in K6a, K6b and K17 is the development of epithelial cysts, generally, at the time of puberty.19,20 Other than steatocystoma multiplex, a “pure” glandular disorder, epidermal inclusion cysts are seen in type 1 and type 2 pachyonychia congenita, while vellus hair cysts and steatocystomas are additionally seen in type 2 pachyonychia congenita.20 The content of these cysts bear a resemblance to sebaceous glands (SGs); in the case of steatocystoma multiplex they are believed, in fact, to originate from SG ducts.20,21,22 There is no molecular rationale, at present, for the development and proliferation of cysts in the skin of individuals bearing mutations in those keratin genes.

Here, we report that K6a gene expression preferentially marks ductal tissue in SGs. We discovered this phenomenon while studying Gli2 transgenic mice (Gli2TG), which as reported offer the distinct advantage of showing markedly enlarged SGs.23 We show that this anomaly begins with an enlargement and elongation of the ductal portion in SG tissue, and is closely paralleled by local enhancement of Hedgehog (Hh) signaling, and by K6a expression at the mRNA and protein levels. Thereafter, additional SGs appear according to a well defined spatiotemporal pattern in Gli2TG mice, and Hh signaling along with K6a expression consistently marks SG ductal tissue during this process. Hh signaling and K6a expression also marks ductal tissue in the normal setting of wild-type mouse skin. Finally, we present molecular evidence that suggests a causal link, likely indirect or partial, between Hh signaling and K6a expression. These original findings have implications for how mutations affecting K6a and its type I keratin partner genes K16 and K17 cause appendageal defects that frequently include an abnormal expansion of SG tissue.20,24,25,26,27,28

Materials and Methods

Animal Models and Whole Mount Epidermal Sheets Preparation

The following transgenic lines were used: hK6a-lacZ mice (23-1p line),29 harboring a transgene consisting of 5.2-kb of 5′upstream sequence from the hK6a gene fused to the lacZ coding sequence modified with a nuclear localization signal; Ptch-lacZ mice (C57Bl/6 strain),30 in which the LacZ sequence has been knocked-in the Patched locus; Gli2TG mice (C57Bl/6 strain),23 in which the mouse Gli2 sequence is downstream from the bovine K5 promoter. Gli2TG/K6a-lacZ and Gli2TG/Ptch-lacZ double-transgenic mice were generated through selective crosses. Genotyping for the K5-Gli2 transgene were performed via PCR. Genotyping for hK6a-lacZ and Ptch-lacZ were performed using β-galactosidase assay in situ.31 All whole mount epidermal sheets were prepared from the upper one-third region on the dorsal side of male mouse tail skin, as described.31,32 All protocols involving mice were reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care Use Committee.

Antibodies, Probes, Plasmids, and Other Reagents

The following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal antisera directed against K6 (“K6gen”),33,34 K1733; a mouse monoclonal antibody directed against K14 (LLOO1).35 Rhodamine- and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were obtained from Kirkegaard and Perry Labs (Gaithersburg, MD).

In situ hybridization for the mK6α mRNA was done as described elsewhere.31 The hK6a promoter-luciferase construct was generated by subcloning 3.3 kb of 5′upstream sequence from the hK6a gene (obtained by NcoI digestion)36 into pGL3-firefly (Promega, Madison, WI). Rat FoxE1 was a gift from Dr. Caterina Missero (Ceinge Biotechologie, Napoli, Italy); mouse Gli2 was a gift from Dr. Philip Beachy. Nuclear factor kappa-B/p6537 and IgK-interferon promoter-luciferase constructs38 were provided by Dr. Mollie Meffert (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Transcription factor coding sequences were subcloned into mammalian expression vectors (nuclear factor kappa-B /p65 in pEGFP; Gli2 in pRK5; FoxE1 in pCMV6). Empty vectors served as controls.

Morphological Analyses

Indirect immunofluorescence and β-galactosidase histochemistry on whole mount epidermal sheets were performed as described.31 For β-galactosidase histochemistry, the incubation were performed 1 hour at 37°C for hK6a-lacZ samples, and overnight for Ptch-lacZ samples. For Oil Red O histochemistry, whole mount epidermal sheets were fixed with 10% formalin for 5 minutes and rinsed in three changes of distilled water. Samples were transferred to Oil Red O working solution (60% of 0.5% Oil Red O/isopropanol in distilled water). After 1 hour, samples were rinsed in 60% isopropanol for 5 minutes and in three changes of distilled water. Samples were mounted with Crystal mounting media (Biomeda, Foster City, CA) and analyzed by microscopy.

Mouse skin tissues (ear, tail, paw, tongue, and eyelid) were obtained from male mice at various ages. Samples were fresh frozen and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetec, Torrance, CA), or were fixed in Bouin’s solution and embedded in paraffin. Normal adult human skin samples, also paraffin-embedded, were used. Five to twenty-μm thick sections (frozen or paraffin) were subjected to H&E staining, indirect immunofluorescence, Oil Red O histochemistry, or β-galactosidase histochemistry as described above. Final preparations were visualized using either a Zeiss Axioplan-2 microscope equipped for fluorescence imaging or a PerkinElmer UltraView confocal microscope.

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assays

Monkey kidney Cos-1 epithelial cells or alternatively, mouse 308 skin keratinocytes,39 were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/ml and incubated at 37°C for one day before transfection. Transient transfection of mouse K6a (cf. above) and mouse K17 gene promoters40 and transcription factors (or corresponding empty vectors, used as controls; cf. above) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in serum-free medium as described.41 Cells were harvested 48 hours later for analysis. Cells were cotransfected with plasmid featuring a given promoter (see description below) subcloned in a pGL3-basic vector (Firefly luciferase, Promega), the promoter-less pGL3-basic plasmid (included as a negative control), and the pRL-TK plasmid (Renilla luciferase, Promega; included to normalize data for transfection efficiency). The assays were controlled, and normalized, by parallel transfection of the relevant empty vectors. Optimal transfection conditions consisted of 1.2 μg total plasmid DNA per well, and a ratio of pGL3 to pRL-TK of 10:1. To assay for luciferase activity, cells were lysed with 100 μl/well of lysis buffer provided with the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega); lysates were stored at −20°C until analyzed. Assays for firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activity were sequentially performed in one reaction well in 96-well plates using 20 μl aliquots of cell lysates. Luciferase activity was measured using a microplate luminometer (Fluoroskan Ascent FL, Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three independent experiments were performed to yield a given reporter activity, which was calculated as “x-fold expression” relative to the control luciferase activity.

Additional Studies on Gli2TG Mouse Skin

For analysis of the hair follicle cycle, skin tissue was always obtained from the mid-back region of age- and gender-matched mouse littermates. Skin pigmentation provides a reliable index of progression through the hair follicle cycle, reflecting the strict coupling of the latter with follicular melanogenesis.42 Shaved mouse back skin was photographed, at predetermined ages, before histological study. For the latter, skin tissue was Bouin’s-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and 5 to 10 μm sections were counterstained with H&E. Hair cycle stage was determined based on mouse age along with well established morphological criteria.42

Morphological analyses of tumor tissue was performed as described in the main text of this article. To determine the levels of K6 and K17 mRNA transcripts by semiquantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from ear tumor of Gli2TG mice and ear tissue of normal littermate mice. Reverse transcription and semiquantitative PCR were performed15 using β-tubulin as an internal control. The oligonucleotide primers used for PCR were used as follows: K17, Forward: 5′-GATGGAGCAGCAGAACCAGGAGTA-3′, Reverse: 5′-GGTCTCAAGCATAGGAATGCTGGGG-3′; K6a, Forward: 5′-GAGCTGGCTTTGGTGGTG-3′, Reverse: 5′-GTCCTCCACTGTGTCCTG-3′; β-tubulin, Forward: 5′-CAACGTCAAGACGGCCGTGTG-3′, Reverse: 5′-GACAGAGGCAAACTGAGCACC-3′.

Results

Dysmorphology and Increased Number of SGs in Gli2TG Mice

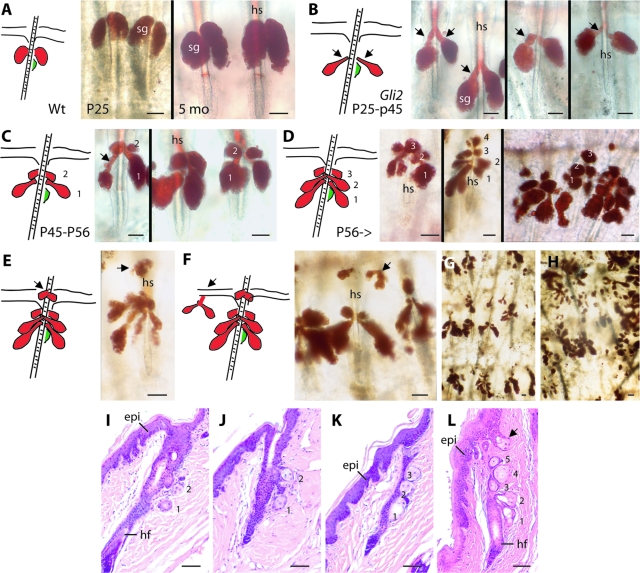

We noted a tremendous expansion of SG tissue in the course of studying whole mount preparations of tail skin epithelia from Gli2TG mice. Normally, a single pair of SGs occurs above the hair bulge/arrector pili muscle unit in hair follicles from tail skin (Figure 1A). This is so for the lifetime of wild-type mice (unpublished data). Owing to its shortness, SG duct tissue is not readily visible on whole-mount preparations (Figure 1A) or tissue sections (data not shown). In Gli2TG mice, however, SG become aberrantly shaped and show markedly elongated and enlarged ducts starting at ∼p25 (Figure 1B). At ∼P45, a second pair of SGs appears above the existing one (Figure 1C). At ∼2 months of age, third and fourth pairs of SGs develop, again in an upward direction along the follicle axis (Figure 1D). Still later on, additional SGs develop at infundibulum-epidermal junctions (Figure 1E) and in the proximal interfollicular epidermis (Figure 1F). In parallel to SG duplication, the original SG and oldest supernumerary ones adopt a complex, branched morphology (Figure 1, G and H). Ectopic SG units can also be seen in Gli2TG skin sections stained with H&E (Figure 1, I–L). While especially prominent in tail tissue, this SG phenotype is also seen in the skin of other body sites in Gli2TG mice (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Comparing sebaceous gland (sg) development in wild-type and Gli2TG mice. A–H: Whole mount tail epidermal preparations, stained with Oil Red O, from wild-type (Wt) (A) and Gli2TG mice (B–H). In (A–F), a summary schematic of the pilosebaceous unit and associated epidermis is shown at left (red: SG; green: hair bulge). A: SG morphology in 25-day-old (P25, left) and 5-month-old (right) wild-type mice. B–H: Gli2TG mice develop a spectacular SG phenotype over time. B: Expansion and elongation of SG ducts (see arrows) in Gli2TG mice between P25 and P45. C: Appearance of an additional pair of SGs in Gli2TG mice, typically seen between P45 and P56. D: Formation of a third, and additional pairs of SGs, in Gli2TG mice after 2 months of age. The original SG is numbered 1 in B–D. E–F: Oil Red O staining reveals the present of ectopic SGs in the infundibulum region of hair follicles (E), and in interfollicular epidermis (F), in a 10-month-old Gli2TG mouse. G–H: Complex arborization of SGs, at lower magnification, in Oil Red O-stained whole mounts from a 10-month-old Gli2TG mouse. I–L: H&E-stained sections prepared from paraffin-embedded Gli2TG tail tissue. Between two and five pairs of SGs can be distinguished. The arrow in frame (L) shows an example of SG seemingly originating from in interfollicular epidermis. Epi, epidermis; hf, hair follicle; hs, hair shaft. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Enhanced Hedgehog Signaling Correlate with Enlargement of SG Ducts in Gli2TG Mice

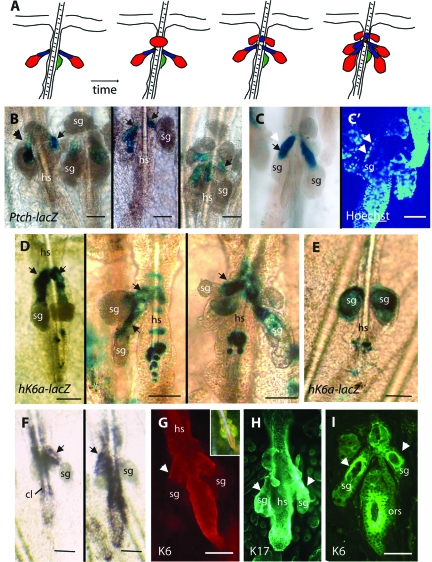

Ptch-lacZ mice30 provide a read-out of sites of Hh-dependent transcription in mouse skin epithelia.43 We crossed Ptch-lacZ and Gli2TG mice and analyzed the double-transgenic progeny by whole-mount X-Gal staining. As illustrated in Figure 2A, Ptch-lacZ reporter signal is strongest to the elongated ducts in SGs from Gli2TG/Ptch-lacZ mice (Figure 2B). Preparations dual-stained for LacZ activity and nuclear DNA (via Hoechst) suggest that the Patched reporter is excluded from the outermost cell layer (Figure 2C). X-Gal staining intensity in SG ducts was comparable to that seen in newly formed hair bulb at the onset of anagen in Ptch-lacZ hair follicles (data not shown). These observations establish that the onset of alterations in SG morphology correlate, early on, with local activation of Hh-dependent transcription. As a side note, the perplexing lack of Ptch-lacZ reporter activity at sites where the Gli2TG transgene is knowingly expressed (eg, epidermis), for at least 4 weeks after birth, has recently been explained by powerful mechanisms mediating Gli degradation.43,44

Figure 2.

Elongation of SG ducts is accompanied by enhanced Hh signaling and K6a expression in Gli2TG mice. A: Summary of Ptch-lacZ and hK6a-lacZ expression, which is very similar, during the development of the SG phenotype between P25 and P56 in Gli2TG mice. B: Activity of the Ptch-lacZ transgene, reflecting Hh signaling, is conspicuously restricted to the elongated ducts of SGs in Gli2TG skin. Several examples are shown (see arrows). C, C’: Dual-staining of a phenotypic SG in Gli2TG skin for lacZ activity (C) and Hoechst (C’), to reveal nuclei, confirms that the outermost layer of SG ducts is devoid of Ptch-lacZ reporter activity (compare the white arrowheads, depicting the outermost layer, with the black arrow in C: marking in inner location of X-Gal staining). D: The hK6a-lacZ transgene is also active in the elongated segment of SG ducts in Gli2TG mice. Several examples are shown (see arrows). E: Occasionally, hK6a-lacZ transgene activity is detected in the distal portion of SG, as shown here; in many cases, interestingly, the duct phenotype is not as pronounced. F: Detection, by in situ hybridization, of the endogenous K6a mRNA in the elongated segment of SG ducts in Gli2TG mice. Signal also occurs in the hair follicle companion layer (cl), as expected.31 G–I: Indirect immunofluorescence for specific antigens on whole mount skin tail preparations (G–H) and tissue sections (I) from Gli2TG mice. F: Whole mount preparation showing K6 immunoreactivity in SG ducts (see arrow) and the lower segment of hair follicles, as described.31 G: Immunoreactivity for K17 in more broadly distributed, although is also includes SG ducts (see arrows). I: K6 immunoreactivity in a tail tissue section from a Gli2TG mouse. Signal is preferentially localized to the inner layer(s) of ductal epithelium (see arrows). hs, hair shaft; sg, sebaceous gland. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Abnormal SG Ducts Show Enhanced Keratin 6a Expression in Gli2TG Mice

Mutations altering the coding sequence of K6a, K6b, K16, or K17 cause pachyonychia congenita, which often features marked anomalies in SGs. We crossed the Gli2TG mice with hK6a-lacZ reporter mice to gain further insight into the SG lesions elicited by local Hh signaling. In addition to being up-regulated after skin injury,29 the hK6a-lacZ reporter is regulated in a hair cycle-dependent fashion in the companion layer of hair follicles.31 LacZ reporter activity is readily detectable in the SG ducts of Gli2TG/hK6a-lacZ mice (Figure 2D). X-Gal staining covers the entire duct (Figure 2D), and in some cases, extends distally to glandular cells (Figure 2E). Endogenous mK6a is also expressed in ductal tissue, as shown by in situ hybridization (Figure 2F) and antibody staining of whole mount preparations (Figure 2G), suggesting that the hK6a-lacZ transgene faithfully reports on its activity. By comparison, K17 shows a broader distribution in the pilosebaceous unit, that also includes the ductal epithelium of SG (Figure 2H). The restriction of K6 immunoreactivity to the innermost portion of SG ducts can be readily appreciated in tissue sections (Figure 2I).

Hedgehog Signaling and K6 Expression Also Coincide in the SG Ducts of Wild-Type Skin

We analyzed the skin of Ptch-lacZ and hK6a-lacZ mice for reporter transgene expression, with a particular emphasis on the P15-P35 age window. In Ptch-lacZ skin, X-Gal staining was present at the base of growing (anagen) hair follicles, as expected (Figure 3A”; also see43), as well as in SG ducts (Figure 3A’). In hK6a-lacZ skin, X-Gal staining also occurred in SG ducts, in addition to a narrow ring located below the SG (Figure 3B; see31). Of note, no X-Gal staining is detectable in wild-type mouse skin (data not shown), confirming the specificity of these findings. In situ hybridization performed on whole-mount epidermal sheets of wild-type mouse skin using a probe specific for the mK6a mRNA also gave rise to a signal in, or near, SG ducts (data not shown). The shortness of the duct, and/or its masking by the gland, precluded us from identifying the precise location of the signal. Unlike Ptch-lacZ (Figure 3A), however, neither hK6a-lacZ nor endogenous mK6a is expressed in the newly formed hair tissue at anagen onset (Figure 3B; see31). These findings indicate that Hh-dependent transcription and K6a expression temporally and spatially coincide in SG ducts of normal mouse skin tissue.

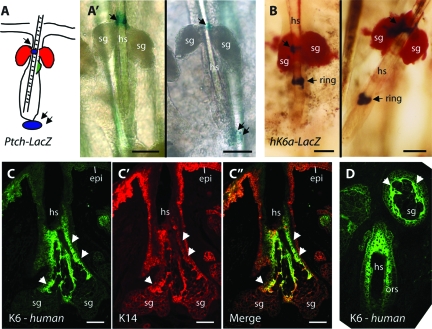

Figure 3.

Hh signaling and K6a expression occurs at the base of sebaceous glands in wild-type mice. A: Summary of Ptch-lacZ transgene activity in otherwise wild-type mouse skin after onset of anagen at P25-P28. A’: Detection of Ptch-lacZ activity in whole mount epidermal sheets prepared from mouse tails, showing lacZ activity in the secondary hair germ (see double arrows) as expected,43 and at the base of SGs near their point of attachment to hair follicles (see arrows). Follicles shown are late telogen (left image) and early anagen stages (right image). B: Detection of hK6a-lacZ activity at the base of SGs (see arrow), and in a ring-like pattern (see “ring”) as described.31 C–C”: Dual immunostaining for K6 (C; green) and K14 (C’; red) in normal human hair-bearing skin. (C”) show the merged signals. Unlike K14, K6 does not occur in epidermis (epi) of normal skin, and its distribution in the pilosebaceous unit is more restricted, and includes the innermost portion of the SG ducts (see arrows). Frame (D) shows a region adjacent to (C); K6 immunoreactivity is strong in the innermost layers of the outer root sheath (ors) in addition to innermost aspect of the SG ducts (arrowheads). hs, hair shaft; sg, sebaceous gland. Scale bars = 50 μm.

In sections prepared from hair follicle-bearing human skin, K6 immunoreactivity occurs in the ductal portion of SG (Figure 3, C and D). K6 antigens show a more restricted distribution than K14 (Figure 3, C’ and C”), as expected. As is the case in mouse skin (Figure 2I), K6 antigens are largely excluded from the outmost layer of epithelial cells encasing SG ducts (Figure 3D).

The Human K6a Promoter Is Modestly Responsive to Gli2 Co-expression in Heterologous Systems

The parallel occurrence of hedgehog signaling and K6a expression in SG ducts raises the prospect that Gli2 stimulates K6a gene transcription. This possibility is strengthened by the notion that K17, which encodes a type I partner keratin for K6a/K6b in several epithelial settings,33 is a bona fide Gli2 target gene.40,45 To test this notion, we performed standard, internally controlled transient transfection assays with luciferase reporter constructs in Cos-1 cells and in mouse skin keratinocytes. Expression of nuclear factor kappa-B (used as a positive control; see46) enhances the intrinsic activity of the K6b promoter by ∼16-fold in Cos-1 cells (Figure 4A), as previously reported,46,47 thereby establishing the validity of our experimental setting. Expression of Gli2 also enhances K6a promoter activity, by ∼4.4-fold in Cos-1 cells (Figure 4A), and ∼3.2-fold in skin keratinocytes (Figure 4B). The transcription factor FoxE1, a Gli2 target gene whose activity is increased during hair follicle morphogenesis and in basal cell carcinoma,48,49 fails to stimulate K6a promoter activity (eg, Figure 4A), showing the specificity of Gli2’s effect on the K6a promoter. On the other hand, and consistent with previous findings,45,40 we find that Gli2 has a considerably stronger impact on the K17 promoter compared to the K6a promoter activity in both Cos-1 cells and skin keratinocytes (Figure 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of Gli2 activates human K6a promoter activity in Cos-1 epithelial cells (A) and 308 mouse skin keratinocytes (B). The hK6a-Luc, mK17-Luc constructs, or control empty vectors, were transiently transfected with or without the identified transcription factor (TF) in Cos-1 cells. Luciferase activity was measured 48 hours later, and normalized, as described in Materials and Methods. Cotransfection of Gli2 increases K6a promoter activity in both Cos-1 cells (4.4-fold; see A) and mouse skin keratinocytes (3.2-fold; see B), though markedly less so than mK17 promoter activity (>50-fold in both instances). Results are representative of three experiments (mean + SD). See text for details.

Additional Observations in Gli2TG Mouse Skin

Hh signaling is essential for the morphogenesis and postnatal cycling of hair follicles.43,50,51,52,53 Mouse skin tissue becomes sensitive to constitutive Gli1 and Gli2 overexpression only at the onset of the first postnatal anagen during the fourth week postbirth.43,44 This time frame also corresponds to the onset of SG anomalies in Gli2TG, prompting us to examine the postnatal hair cycle in the back skin of these mice. Entry into the first iteration of the catagen and telogen stages occurs at similar times in Gli2TG and wild-type littermates (data not shown). However, anagen re-entry is delayed and occurs at ∼P30/P31 in Gli2TG mice, instead of ∼P25-P28 as seen in wild-type controls (Supplementary Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).42 The initial alterations affecting SGs thus coincide with a delay in anagen re-entry in Gli2TG hair follicles, and these events occur significantly ahead of tumor formation in this mouse model (unpublished observations).23

Previous reports indicate that several Hedgehog target genes, including Patched and K17, are robustly expressed in skin tumors arising in older Gli2TG mice, and in tumor-proximal hyperplastic epithelium.23,43,44 If K6a expression is under the (direct or indirect) control of Gli2, then it should be induced in Gli2TG tumor tissue. K6 immunoreactivity can indeed be detected in pretumoral epithelial downgrowths (Supplementary Figure S1C, C’ at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) and in tumor tissue as well (Supplementary Figure S1D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In the latter, however, K6 immunoreactivity is only patchy, and is strongest in donut-shaped structures (Supplementary Figure S1D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org) which, on H&E staining, are reminiscent of glandular ducts (Supplementary Figure S1E at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). This pattern is distinct from the uniform, pan-tumor staining seen when staining similar sections for K17 (Supplementary Figure S1F at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), and extends previous reports of spotty K6 expression in human BCC tumors.54,55 Away from such skin lesions, K6 immunoreactivity is restricted to epithelial appendages as is the case for wild-type skin (Supplementary Figure S1G, G’ at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Again, the hK6a-lacZ reporter shows an identical activity profile when examined in the skin of Gli2TG/hK6a-lacZ double-transgenic mice (data not shown). Confirming these findings, RT-PCR analyses show that the endogenous K6a and K17 mRNAs are elevated in ear tumor tissue harvested from adult Gli2TG mice, as compared with wild-type (Supplementary Figure S1H at http://ajp.amjpathol. org).

Discussion

The morphogenesis of sebaceous glands, and their homeostasis, is not well understood. Sebocytes arise from a pool of mitotically active, transit-amplifying “basal cells” located in the outermost aspect of the gland per se, and undergo holocrine secretion in the hair canal, calling for their replenishment on a continuous basis.56,57,58 The ultimate source for the sebocyte lineage, in adult mouse skin, is a small pool of committed progenitor cells tucked within the outer root sheath at or near the point of SG branching from hair follicles. There is evidence that a transcriptional repressor, Blimp-1, helps maintain these cells in a relatively quiescent state.58 The ductal epithelium, which comprises three layers (basal, intermediate, granular layers), lies between these quiescent stem cells and the transit-amplifying “basal” cells that encapsulate the distal part of the SG.57 Whether the various cell types in the ductal epithelium and gland per se represent different steps along a single path to differentiation, or are the product of distinct differentiation programs from a common progenitor, is unknown, as is the pattern of cell movement within SG.

Molecularly, gain- and loss-of-function studies have shown that activation of Hedgehog signaling59,60 and c-Myc61,62 stimulates SG morphogenesis and, eventually, cause SG tumors in mouse skin.63 Likewise, interference with Lef1-dependent Wnt signaling, resulting from either a dominant-negative strategy in mice (via ΔNLef1)60 or somatic mutations in humans,64 leads to de novo formation of SGs and their tumorigenesis as well. Intriguingly, overexpressed ΔNLef1 causes an up-regulation of Indian hedgehog in mature sebocytes, which on its secretion and limited diffusion would activate the proliferation of committed SG progenitors, causing SG enlargement.60 The idea of an interplay between Wnt and Hh signaling, and likely other pathways, in determining lineage choices followed by organ morphogenesis in skin epithelia has gained a lot of support in recent years.60,65,66

Our results establish that Hh signal reception is strongest within the duct segment of SG. This is so not only in the skin of wild-type mice but also in Gli2-overexpressing mice starting at 4 weeks postbirth. Previous work showed that Hh signaling plays a key role during ductal and branching morphogenesis in other glandular organs including prostate,67 mammary gland,68 salivary gland,69 lung,70 and pancreas.71 Our findings of “duct-preferred” Hh signaling, and of an aberrant branching phenotype in Gli2TG skin, suggest that Hh signaling plays a similar role in SG as well. Hh signaling is also key to initiation of a new anagen phase in the resting follicles of adult skin51,53,72 and, interestingly, the initial enlargement and elongation of SG ducts in Gli2TG mice temporally coincides with a delay in the onset of the first postnatal anagen (growth) phase in hair follicles. Therefore, the “broad” ectopic expression of Gli2 in this setting, and at ∼3.5 weeks postbirth, could stimulate early progenitor cells to divide, and contribute to re-direct their fate from hair follicle to SG. Bulge stem cells, which are proximal to SG ducts but normally give rise to hair follicle lineages, can indeed be directed toward SG and epidermal fates under special circumstances.58,73,74,75 Such a mechanism has been proposed to underlie the continued formation of sebum-filled dermal cysts in Hairless mice, which fail to re-initiate anagen.76,77 It may prove relevant to investigate the status of signaling effectors known to promote SG morphogenesis, such as Gli, c-Myc, and others, in steatocystoma lesions from pachyonychia congenita patients.

Another observation having potential implications for stem cell location, and regulation, is the highly ordered pattern of de novo SG morphogenesis observed along the hair follicle axis, and in the interfollicular epidermis, of adult Gli2TG mice. The specific spatial pattern seen may reflect the location of early progenitor, bipotent cells in the upper segment of skin epithelia, as recently suggested.78

We report here that K6a is primarily expressed in the suprabasal layers of SG ducts in both wild-type and Gli2TG mice, and in human. These findings extend previous reports of K6 expression in the ductal epithelium of sweat glands79 and developing mammary glands,80,81,82 and of K6b isoform expression, specifically, in sweat gland ducts of human skin.83 The role of K6 isoforms in glandular epithelia remains an enigma (eg, ref. 82) despite the creation and study of several relevant mouse models, in particular, K6a/K6b double null mice.10,84 Clearly, SGs can form in the absence of these keratins (unpublished data),14,84 but the significance of this observation is unclear as K5 and possibly K75 (formerly K6hf) may well compensate for the loss of K6.34,84 The early postnatal death of K6a/K6b null mice10 also makes it impossible to examine SG homeostasis in the adult setting. What about functions revealed in non-glandular epithelia? Studies in K6a/K6b null mice evidenced the essential structural support role of these two keratins in the oral mucosa,10 and during wound repair after acute injury to skin.14 Constitutive K6 expression often occurs in contexts where an epithelial sheet is moving alongside a stationary epithelial phase.4 In addition to the wound edge, this is so at the interface between the outer root sheath and companion layer in hair follicles, and between the nail bed and nail plate.4,31,85,86 Both mechanical support and regulation of cell migration could account for the presence of K6 in sweat gland ducts. In addition to better mouse models, however, resolution of this issue awaits a better understanding of cellular homeostasis in mature SGs. As a side note, the frequent occurrence of steatocystoma lesions and, though in a rare manner, of premature tooth eruption19,20 lends further credence to the notion that K6 protein(s) (and their partners) may fulfill roles other than structural support in epithelia. In this vein, the positive role of K1716 and other skin keratins87 toward the regulation of protein synthesis could be enhanced by mutations in K6 isoforms, and/or in K17.

Finally, there is the issue of whether K6a is a direct target for Gli2 transcription factors in vivo. Relative to the K17 proximal promoter, which is exquisitely sensitive to Gli2 (>70-fold response), the K6a promoter shows a very modest response (3- to 4-fold range; see Figure 4). Unlike K17,88 the epidermis of newborn and young adult Gli2TG mice is negative for K6 antigens, though later on, spotty K6 expression can be observed in tumors and tumor-proximal hyperplastic epidermis (Supplementary Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Such arguments favor the possibility that K6 is an indirect target of Gli2, or alternatively, that the latter works cooperatively with another factor(s) to transactivate the K6a promoter. While the 5′ upstream sequence of both hK6a and mK6a do not feature the strong Gli2-responsive element identified in the K17 proximal promoter,40 another Gli-binding site, GGACACCCA, is present (−1925 bp to −1917 bp from the translational start site of hK6a; data not shown). This particular site confers a similar responsiveness to the FoxE1 gene promoter.48 Although our findings definitely establish that K17 and K6a represent Gli2 targets of high and low sensitivity, respectively, further studies are required to establish the mechanism of Hh signal-associated K6a gene expression in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Anj Dlugosz and David Berman for kindly sharing transgenic mouse lines, Drs. Phil Beachy, Caterina Missero, and Mollie Meffert for providing constructs, and members of the Coulombe laboratory for support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Pierre A. Coulombe, Department of Biological Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 725 N. Wolfe St., Baltimore, MD 21205. E-mail: coulombe@jhmi.edu.

Supported by the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant AR42047 to P.A.C.), and National Cancer Institute (grant CA123530 to P.A.C.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Szeverenyi I, Cassidy AJ, Chung CW, Lee BT, Common JE, Ogg SC, Chen H, Sim SY, Goh WL, Ng KW, Simpson JA, Chee LL, Eng GH, Li B, Lunny DP, Chuon D, Venkatesh A, Khoo KH, McLean WH, Lim YP, Lane EB. The Human Intermediate Filament Database: comprehensive information on a gene family involved in many human diseases. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:351–360. doi: 10.1002/humu.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Cleveland DW. A structural scaffolding of intermediate filaments in health and disease. Science. 1998;279:514–519. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary MB, Coulombe PA, McLean WHI. Intermediate filament proteins and their associated diseases. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2087–2100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu LH, Coulombe PA. Keratin function in skin epithelia: a broadening palette with surprising shades. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Coulombe PA. Intermediate filament scaffolds fulfill mechanical, organizational, and signaling functions in the cytoplasm. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1581–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.1552107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan KM, Coulombe PA. The wound repair associated keratins 6, 16, and 17: insights into the role of intermediate filaments in specifying cytoarchitecture. Harris JR, Herrmann H, editors. London: Plenum Publishing Co.,; 1998:pp. 141–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe PA, Tong X, Mazzalupo S, Wang Z, Wong P. Great promises yet to be fulfilled: defining keratin intermediate filament function in vivo. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:735–746. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RA, Eichner R, Sun TT. Monoclonal antibody analysis of keratin expression in epidermal diseases: a 48- and 56-kdalton keratin as molecular markers for hyperproliferative keratinocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1397–1406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swensson O, Langbein L, McMillan JR, Stevens HP, Leigh IM, McLean WH, Lane EB, Eady RA. Specialized keratin expression pattern in human ridged skin as an adaptation to high physical stress. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:767–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Colucci-Guyon E, Takahashi K, Gu C, Babinet C, Coulombe PA. Introducing a null mutation in the mouse K6alpha and K6beta genes reveals their essential structural role in the oral mucosa. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:921–928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan KM, Tong X, Colucci-Guyon E, Langa F, Babinet C, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 null mice exhibit age- and strain-dependent alopecia. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1412–1422. doi: 10.1101/gad.979502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik S, Bundman D, Roop D. Delayed wound healing in keratin 6a knock-out mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5248–5255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5248-5255.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawersik MJ, Mazzalupo S, Nguyen D, Coulombe PA. Increased levels of keratin 16 alter the epithelialization potential of mouse skin keratinocytes in vivo and ex vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3439–3450. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Coulombe PA. Loss of keratin 6 (K6) proteins reveals a function for intermediate filaments during wound repair. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:327–337. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 regulates hair follicle cycling in a TNFalpha-dependent fashion. Genes & Dev. 2006;20:1353–1364. doi: 10.1101/gad.1387406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Wong P, Coulombe PA. A keratin cytoskeletal protein regulates protein synthesis and epithelial cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature04659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thesleff I, Mikkola ML. Death receptor signaling giving life to ectodermal organs. Sci STKE. 2002:PE22. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.131.pe22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine AD, McLean WH. Human keratin diseases: the increasing spectrum of disease and subtlety of the phenotype-genotype correlation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:815–828. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein A, Friedman J, Schewach M. Pachyonychia congenita. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:705–711. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70226-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leachman SA, Kaspar RL, Fleckman P, Florell SR, Smith FJ, McLean WH, Lunny DP, Milstone LM, van Steensel MA, Munro CS, O'Toole EA, Celebi JT, Kansky A, Lane EB. Clinical and pathological features of pachyonychia congenita. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen C, Ackerman AB, editors. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger,; Steatocystomas. 1994:148–181. [Google Scholar]

- Naik NS. Steatocystoma multiplex. Derm Online J. 2000;6:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grachtchouk M, Mo R, Yu S, Zhang X, Sasaki H, Hui CC, Dlugosz AA. Basal cell carcinomas in mice overexpressing Gli2 in skin. Nat Genet. 2000;24:216–217. doi: 10.1038/73417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean WHI, Rugg EL, Lunny DP, Morley SM, Lane EB, Swensson O, Dopping-Hepenstal PJC, Griffiths WAD, Eady RAJ, Higgins C, Navsaria HA, Leigh IM, Stachan T, Kunkeler L, Munro CS. Keratin 16 and keratin 17 mutations cause pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;9:273–278. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden PE, Haley JL, Kansky A, Rothnagel JA, Jones DO, Turner RJ. Mutation of a type II keratin gene (K6a) in pachyonychia congenita. Nat Genet. 1995;10:363–365. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FJ, Corden LD, Rugg EL, Ratnavel R, Leigh IM, Moss C, Tidman MJ, Hohl D, Huber M, Kunkeler L, Munro CS, Lane EB, McLean WH. Missense mutations in keratin 17 cause either pachyonychia congenita type 2 or a phenotype resembling steatocystoma multiplex. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:220–223. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12335315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covello SP, Smith FJ, Sillevis Smitt JH, Paller AS, Munro CS, Jonkman MF, Uitto J, McLean WH. Keratin 17 mutations cause either steatocystoma multiplex or pachyonychia congenita type 2. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:475–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FJ, Jonkman MF, van Goor H, Coleman CM, Covello SP, Uitto J, McLean WH. A mutation in human keratin K6b produces a phenocopy of the K17 disorder pachyonychia congenita type 2. Human Molecular Genetics. 1998;7:1143–1148. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Coulombe PA. Defining a region of the human keratin 6a gene that confers inducible expression in stratified epithelia of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11979–11985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich LV, Milenkovic L, Higgins KM, Scott MP. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science. 1997;277:1109–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu LH, Coulombe PA. Keratin expression provides novel insight into the morphogenesis and function of the companion layer in hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun KM, Niemann C, Jensen UB, Sundberg JP, Silva-Vargas V, Watt FM. Manipulation of stem cell proliferation and lineage commitment: visualisation of label-retaining cells in wholemounts of mouse epidermis. Development. 2003;130:5241–5255. doi: 10.1242/dev.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan KM, Coulombe PA. Onset of keratin 17 expression coincides with the definition of major epithelial lineages during skin development. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:469–486. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wong P, Langbein L, Schweizer J, Coulombe PA. Type II epithelial keratin 6hf (K6hf) is expressed in the companion layer, matrix, and medulla in anagen-stage hair follicles. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1276–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkis PE, Steel JB, Mackenzie IC, Nathrath WB, Leigh IM, Lane EB. Antibody markers of basal cells in complex epithelia. J Cell Sci. 1990;97:39–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Paladini R, Coulombe PA. Cloning and characterization of multiple human genes and cDNAs encoding highly related type II keratin 6 isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18581–18592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffert MK, Chang JM, Wiltgen BJ, Fanselow MS, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B functions in synaptic signaling and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/nn1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz JL, Denny EM, Baltimore D. CARD11 mediates factor-specific activation of NF-kappaB by the T cell receptor complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:5184–5194. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland JE, Greenhalgh DA, Koceva-Chyla A, Hennings H, Restrepo C, Balaschak M, Yuspa SH. Development of murine epidermal cell lines which contain an activated rasHa oncogene and form papillomas in skin grafts on athymic nude mouse hosts. Cancer Res. 1988;48:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi N, DePianto D, McGowan K, Gu C, Coulombe PA. Exploiting the keratin 17 gene promoter to visualize live cells in epithelial appendages of mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7249–7259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7249-7259.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu LH, Coulombe PA. Defining the properties of the nonhelical tail domain in type II keratin 5: insight from a bullous disease-causing mutation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1427–1438. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Rover S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, Eichmuller S, Foitzik K, McKay IA, Stenn KS, Paus R. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oro AE, Higgins K. Hair cycle regulation of hedgehog signal reception. Dev Biol. 2003;255:238–248. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntzicker EG, Estay IS, Zhen H, Lokteva LA, Jackson PK, Oro AE. Dual degradation signals control Gli protein stability and tumor formation. Genes Dev. 2006;20:276–281. doi: 10.1101/gad.1380906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CA, Ofstad T, Horng L, Wang JK, Zhen HH, Coulombe PA, Oro AE. MIM/BEG4, a sonic hedgehog-responsive gene that potentiates Gli-dependent transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2724–2729. doi: 10.1101/gad.1221804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komine M, Rao LS, Kaneko T, Tomic-Canic M, Tamaki K, Freedberg IM, Blumenberg M. Inflammatory versus proliferative processes in epidermis. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces K6b keratin synthesis through a transcriptional complex containing NFkappa B and C/EBPbeta. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32077–32088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Rao L, Freedberg IM, Blumenberg M. Transcriptional control of K5. K6, K14, and K17 keratin genes by AP-1 and NF-kappaB family members. Gene Expr. 1997;6:361–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichberger T, Regl G, Ikram MS, Neill GW, Philpott MP, Aberger F, Frischauf AM. FOXE1, a new transcriptional target of GLI2 is expressed in human epidermis and basal cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1180–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio A, Minichiello A, Grachtchouk M, Antonini D, Sheng H, Parlato R, Dathan N, Dlugosz AA, Missero C. Requirement of the forkhead gene foxe1, a target of sonic hedgehog signaling, in hair follicle morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2595–2606. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, Botchkarev VA, Li J, Danielian PS, McMahon JA, Lewis PM, Paus R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Leopold PL, Crystal RG. Induction of the hair growth phase in postnatal mice by localized transient expression of Sonic hedgehog. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:855–864. doi: 10.1172/JCI7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Swan RZ, Grachtchouk M, Bolinger M, Litingtung Y, Robertson EK, Cooper MK, Gaffield W, Westphal H, Beachy PA, Dlugosz AA. Essential role for sonic hedgehog during hair follicle morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 1999;205:1–9. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paladini RD, Saleh J, Qian C, Xu GX, Rubin LL. Modulation of hair growth with small molecule agonists of the hedgehog signaling pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:638–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey AC, Lane EB, Macdonald DM, Leigh IM. Keratin expression in basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:154–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb07813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto O, Asahi M. Cytokeratin expression in trichoblastic fibroma (small nodular type trichoblastoma), trichoepithelioma and basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:8–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiboutot D. Regulation of human sebaceous glands. J Investig Dermatol. 2004;123:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2004.t01-2-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie MMT, Guy R, Kealy T. Advances in sebaceous gland research: potential new approached to acne management. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2004;26:291–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2004.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley V, O'Carroll D, Tooze R, Ohinata Y, Saitou M, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Blimp1 defines a progenitor population that governs cellular input to the sebaceous gland. Cell. 2006;126:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Grachtchouk M, Sheng H, Grachtchouk V, Wang A, Wei L, Liu J, Ramirez A, Metzger D, Chambon P, Jorcano J, Dlugosz AA. Hedgehog signaling regulates sebaceous gland development. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2173–2178. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63574-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann C, Unden AB, Lyle S, Zouboulis Ch C, Toftgard R, Watt FM. Indian hedgehog and beta-catenin signaling: role in the sebaceous lineage of normal and neoplastic mammalian epidermis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100 Suppl 1:11873–11880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834202100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waikel RL, Kawachi Y, Waikel PA, Wang XJ, Roop DR. Deregulated expression of c-Myc depletes epidermal stem cells. Nat Genet. 2001;28:165–168. doi: 10.1038/88889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull JJ, Pelengaris S, Hendrix S, Chronnell CM, Khan M, Philpott MP. Ectopic expression of c-Myc in the skin affects the hair growth cycle and causes an enlargement of the sebaceous gland. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1125–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann C, Owens DM, Schettina P, Watt FM. Dual role of inactivating Lef1 mutations in epidermis: tumor promotion and specification of tumor type. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2916–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda H, Lyle S, Lazar AJ, Zouboulis CC, Smyth I, Watt FM. Human sebaceous tumors harbor inactivating mutations in LEF1. Nat Med. 2006;12:395–397. doi: 10.1038/nm1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Celso C, Prowse DM, Watt FM. Transient activation of beta-catenin signalling in adult mouse epidermis is sufficient to induce new hair follicles but continuous activation is required to maintain hair follicle tumours. Development. 2004;131:1787–1799. doi: 10.1242/dev.01052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Horsley V. More than one way to skin. Genes Dev. 2008;22:976–985. doi: 10.1101/gad.1645908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm ML, Catbagan WS, Laciak RJ, Barnett DH, Hebner CM, Gaffield W, Walterhouse D, Iannaccone P, Bushman W. Sonic hedgehog activates mesenchymal Gli1 expression during prostate ductal bud formation. Dev Biol. 2002;249:349–366. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes RC, Zhang X, Harrington N, Fung JY, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Allred DC, Lewis MT. Constitutive activation of smoothened (SMO) in mammary glands of transgenic mice leads to increased proliferation, altered differentiation and ductal dysplasia. Development. 2007;134:1231–1242. doi: 10.1242/dev.02797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskoll T, Leo T, Witcher D, Ormestad M, Astorga J, Bringas P, Jr, Carlsson P, Melnick M. Sonic hedgehog signaling plays an essential role during embryonic salivary gland epithelial branching morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:722–732. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urase K, Mukasa T, Igarashi H, Ishii Y, Yasugi S, Momoi MY, Momoi T. Spatial expression of sonic hedgehog in the lung epithelium during branching morphogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;225:161–166. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri S, Hebrok M. Dynamics of embryonic pancreas development using real-time imaging. Dev Biol. 2007;306:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LC, Liu ZY, Gambardella L, Delacour A, Shapiro R, Yang J, Sizing I, Rayhorn P, Garber EA, Benjamin CD, Williams KP, Taylor FR, Barrandon Y, Ling L, Burkly LC. Conditional disruption of hedgehog signaling pathway defines its critical role in hair development and regeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:901–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Rendl M, Fuchs E. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 2004;303:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy V, Lindon C, Harfe BD, Morgan BA. Distinct stem cell populations regenerate the follicle and interfollicular epidermis. Dev Cell. 2005;9:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, Nguyen J, Liang F, Morris RJ, Cotsarelis G. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat Med. 2005;11:1351–1354. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteleyev AA, van der Veen C, Rosenbach T, Muller-Rover S, Sokolov VE, Paus R. Towards defining the pathogenesis of the hairless phenotype. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:902–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin G, Sisk J, Coulombe PA, Thompson C. Hairless triggers reactivation of hair growth by promoting Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14653–14658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507609102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Celso C, Berta MA, Braun KM, Frye M, Lyle S, Zouboulis CC, Watt FM. Characterisation of bipotential epidermal progenitors derived from human sebaceous gland: contrasting roles of c-Myc and {beta}-catenin. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1141–1152. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernot K, McGowan K, Coulombe PA. Keratin 16 expression defines a subset of epithelial cells during skin morphogenesis and the hair cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1137–1149. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.19518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GH, Mehrel T, Roop DR. Differential keratin gene expression in developing, differentiating, preneoplastic, and neoplastic mouse mammary epithelium. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:161–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Welm B, Podsypanina K, Huang S, Chamorro M, Zhang X, Rowlands T, Egeblad M, Cowin P, Werb Z, Tan LK, Rosen JM, Varmus HE. Evidence that transgenes encoding components of the Wnt signaling pathway preferentially induce mammary cancers from progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15853–15858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136825100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm SL, Bu W, Longley MA, Roop DR, Li Y, Rosen JM. Keratin 6 is not essential for mammary gland development. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R29. doi: 10.1186/bcr1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik SM, Longley MA, Roop DR. Discovery of a novel murine keratin 6 (K6) isoform explains the absence of hair and nail defects in mice deficient for K6a and K6b. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:619–630. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan KM, Coulombe PA. Keratin 17 expression in the hard epithelial context of the hair and nail, and its relevance for the pachyonychia congenita phenotype. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:1101–1107. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Domergue R, Coulombe PA. Overcoming functional redundancy to elicit pachyonychia congenita-like nail lesions in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:197–205. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.197-205.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kellner J, Lee CH, Coulombe PA. Interaction between the keratin cytoskeleton and eEF1Bgamma affects protein synthesis in epithelial cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:982–983. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns ML, DePianto D, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P, Coulombe PA. Reprogramming of keratin biosynthesis by sulforaphane restores skin integrity in epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14460–14465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706486104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]