Abstract

Decorin, a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan gene family, down-regulates members of the ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase family and attenuates their signaling, leading to growth inhibition. We investigated the effects of decorin on the growth of ErbB2-overexpressing mammary carcinoma cells in comparison with AG879, an established ErbB2 kinase inhibitor. Cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth assays showed that decorin was a potent inhibitor of breast cancer cell growth and a pro-apoptotic agent. When decorin and AG879 were used in combination, the inhibitory effect was synergistic in proliferation assays but only additive in both colony formation and apoptosis assays. Active recombinant human decorin protein core, AG879, or a combination of both was administered systemically to mice bearing orthotopic mammary carcinoma xenografts. Primary tumor growth and metabolism were reduced by approximately 50% by both decorin and AG879. However, no synergism was observed in vivo. Decorin specifically targeted the tumor cells and caused a significant reduction of ErbB2 levels in the tumor xenografts. Most importantly, systemic delivery of decorin prevented metastatic spreading to the lungs, as detected by novel species-specific DNA detection and quantitative assays. In contrast, AG879 failed to have any effect. Our data support a role for decorin as a powerful and effective therapeutic agent against breast cancer due to its inhibition of both primary tumor growth and metastatic spreading.

Decorin is a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan gene family,1,2,3 with a protein core that directly modulates collagen fibrillogenesis and matrix assembly.4 It negatively regulates the growth of a variety of tumor cells5,6,7,8 by specifically binding to and down-regulating the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)9,10,11,12,13,14,15 and blocking the transforming growth factor β signaling pathway.16,17,18,19 Decorin affects a number of biological processes including inflammatory responses,20,21wound healing, and angiogenesis22,23,24,25 by affecting endothelial cell migration,26 interacting with thrombospondin 1,27 and suppressing the endogenous production of the vascular endothelial growth factor.28 Although mutant mice with a targeted deletion of decorin do not develop spontaneous tumors,29 mice with a double deficiency of decorin and p53 die prematurely of aggressive lymphomas indicating that lack of decorin is permissive for in vivo tumorigenesis.30 In support of this concept, low levels of decorin in invasive breast carcinomas are associated with poor outcome as compared with patients expressing higher levels.31

We have previously shown that squamous carcinoma tumor xenografts can be inhibited when tumor cells genetically engineered to express ectopic decorin are injected or when decorin is injected systemically.13,32 These results have been corroborated by the fact that adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of decorin can attenuate the growth of tumor xenografts of various histogenetic background, including those derived from colon and squamous carcinoma,33 lung and liver carcinoma,6 gliomas,7 and breast carcinoma.34

In the present study we focused on proving the clinical potential of decorin against breast cancer. In this regard, we compared decorin’s effect to the one of AG879, an established ErbB2-selective kinase inhibitor35 using MTLn3 breast carcinoma cells, which grow rapidly, express high levels of ErbB2 as in humans, and metastasize to the lungs in nearly 100% of cases.36 For the first time, we injected decorin systemically to mice bearing orthotopic mammary carcinoma xenografts to investigate whether decorin could inhibit breast cancer growth and metastases.

The results showed an effective antitumor and antimetastatic activity of decorin protein core. This could potentially translate into a powerful and effective therapeutic modality for metastatic breast cancer in humans.

Materials and Methods

Cells, Materials, and Purification of Recombinant Decorin

MTLn3 rat mammary adenocarcinoma cell line was a kind gift of Dr. Segall (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY). Cells were grown in α-modified Eagles’ medium with 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The 4-anilinoquinazoline derivative AG879 was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA) and Trappsol from CTD, Inc. (High Springs, FL). Monoclonal mouse anti-His6 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), polyclonal rat anti-CD31 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and polyclonal rabbit anti-ErbB2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were used. Purification and characterization of biologically active decorin was performed as described before.37,38

Kinase Inhibitor and Cell Proliferation Assays

AG879 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide for in vitro or in 100 mmol/L Trappsol for in vivo. Trappsol (hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin) was dissolved in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline. Dimethyl sulfoxide was used for controls. 2.5 × 104 cells/well were seeded in 12-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and cultured for 24 hours. Cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of decorin protein core (0.01 to 4 μmol/L), AG879 (0.5 to 20 μmol/L), or the combination of decorin protein core and AG879. At the end of the incubation, cells were washed once with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline, trypsinized, stained with trypan blue, and counted using a hematocytometer chamber.

Combination Index and Isobologram

The pharmacological interactions of decorin and AG879 were determined by isobologram and the “Chou and Talalay” combination index analysis.39 Combination index of mutually nonexclusive agents = (Da + Db)/(Dxa + Dxb) + DaDb/DxaDxb. A combination index <1, = 1 and >1 indicates synergism, additive effect, and antagonism, respectively. Combination index values were determined for a range of effects (Fa = 0.1 to 0.8) where AG879 and decorin were used at a ratio of 3:1. The dose of each drug required to achieve x% inhibition was acquired from the median-effect equation: fa/fu = (D/Dm)m, where D is the dose of a drug, fa is the fraction of the population affected by D, fu is the fraction unaffected (1 – fa), Dm is the median-effect dose (ED50) and m is the coefficient signifying the shape of the dose-effect curve.

Colony Formation Assay, Apoptosis, and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis

Agarose base was made using 1% (w/v) agarose (Promega, Madison, WI) combined with 2× Dulbecco’s-modified Eagles’ medium/20% fetal bovine serum, and 1.5 ml of the mixture was added to 35-mm plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). Top agarose (FisherBiotech, Fair Lawn, NJ) was 0.35% (w/v) final concentration. 0.5 × 104 cells were added to each plate by mixing with 1.5 ml of 0.35% agarose along with decorin core (1.04 μmol/L), AG879 (3.16 μmol/L), or the combination. Plates were incubated for 10 days with medium replacement every 48 hours. Colonies were examined with a DP12 camera system (Olympus Optical Co., LTD) and measured by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Minimum colony size cut off was set at 50 μm; and 105 cells were seeded on glass slides and cultured overnight. Cells were treated with decorin (1.04 μmol/L), AG879 (3.16 μmol/L), or the combination, in medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum for 48 hours. Cells were fixed with ice-cold acetone and nuclei were stained with 4′-6-diamindino-2-phenylindole. Fractured and condensed nuclei were recognized as apoptotic bodies under fluorescence microscopy and quantified. For fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis, cells were suspended in 50 μg/ml propidium iodide in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline with 1 μg/ml RNase A. Cells were stained for 2 hours and DNA fragmentation was analyzed using an Epics XL-MCL sorter (Beckman Coulter, San Diego, CA).

Migration and Invasion Assays

MTLn3 cells were seeded onto 12-well plates and allowed to grow in 5% serum-containing medium. When cells reached confluence, the wells were scratched with a thin disposable tip to generate a wound in the monolayer. The cells were grown for an additional day in the presence or absence of decorin (1.04 μmol/L), AG879 (3.16 μmol/L), or in combination in medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum. Photos of the wound were taken every 2 hours with a DP12 camera system (Olympus Optical Co., LTD) and the wound closure was measured by ImageJ software. Three measurements were taken for each wound at each time point and the mean was used for quantification purpose. Invasion assays were performed using a Boyden chamber with a Matrigel-soaked 8.0 μm filter membrane. Approximately 3 × 104 cells were re-suspended in serum-containing medium in the presence or absence of decorin (1.04 μmol/L), AG879 (3.16 μmol/L) or in combination, and applied to the top chamber. The bottom chamber contained MTLn3-conditioned medium. After 24 hours the filters were washed and fixed in methanol and the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution.

In Vivo Tumor Studies and Immunofluorescence Analysis

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Thomas Jefferson University. Orthotopic mammary adenocarcinoma xenografts were established as described previously.34,40 Female severe-combined immunodeficient mice (Charles River Laboratories) were injected with 106 MTLn3 cells into the upper right fat pad. Three independent experiments were performed injecting decorin at a dose of 5 mg/kg. One additional experiment was performed injecting 10 mg/kg. In two independent experiments the mice received decorin (3 mg/kg), AG879 (20 mg/kg), or their combination. Treatment was started 4 days after cell inoculation and carried on every other day via intraperitoneal injections. Controls received 100 mmol/L Trappsol solution. Tumor volumes were determined as described before.33 Animals were sacrificed at day 26, and tumors, lungs, livers, and hearts were collected, snap-frozen, or fixed. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized with CO2 in accordance with guidelines. Frozen sections were fixed in ice-cold acetone, blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin, and subjected to immunohistochemistry. Sections were also counterstained with 4′-6-diamindino-2-phenylindole. Images were acquired as described before.32 The green channel intensity to quantify ErbB2 levels was analyzed by three-dimensional surface plot with ImageJ 1.34 (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).41

Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Scanning and Image Analysis

Positron emission tomography (PET) studies were performed using the MOSAIC PET scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA). Before PET and computed tomography (CT) imaging, mice were injected with 0.4 to 0.5 mCi of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose and allowed two hours for tracer distribution. Immediately before imaging, mice were anesthetized with an injection of ketamine, xylazine, and acetopromozine (200, 10, and 2 mg/kg, respectively) and placed in a 50-ml tube to facilitate multimodality stereotactic positioning. The images were acquired and analyzed as described before.32 Tumor area and signal were defined by PET comparing to contralateral abdominal region.

Species-Specific PCR Analysis

DNA was isolated from mice lungs using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). To assess the presence of rat cell-derived metastasis, a set of primers was designed for the detection of the Rattus Norvegicus vomeronasal 1 receptor m3 (V1rm3; accession number NM_001008934). Two superfamilies of vomeronasal pheromone receptors, V1r and V2r, are known in mammals and they differ in expression, location, and gene structure.42 The most notable difference between the V1r repertories of the mouse and the rat is the presence of two mouse-specific (H and I) and two rat-specific (M and N) families.43 No functional genes or pseudo-genes that belong to the two rat families were found in the mouse. For detection of the V1rm3 DNA, forward primer 5′-GGTGAGACCCACAAACTTGA-3′, in frame and reverse primer 5′-GATAAGATGGCAGCTACAGG-3′, not in frame, were designed. PCR was performed using the PCR Core Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Three PCR were performed in all cases with different DNA concentrations (50, 100, and 200 ng/μl) and different melting temperatures (57°C, 61°C, and 64°C). Densitometric analysis of the PCR bands was performed using the β 4.0.3 version of Scion Image software (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed with SigmaStat for Windows version 3.10 (Systat Software, Inc., Port Richmond, CA). Data were expressed as the mean values with 95% confidence interval (CI) after running two-sided Student’s t-test. Treatments effect on tumor growth was statistically evaluated by analysis of variance, followed by Student’s t-test.

Results

Synergistic Effects of Decorin Protein Core and AG879 on Mammary Carcinoma Cell Growth

Anilinoquinazoline molecules and their derivatives, such as AG1478 and AG879,35 have received much attention in the literature by displaying therapeutic potential against certain types of cancer.44,45,46 We have previously shown that decorin dramatically affects the growth of EGFR- and ErbB2-expressing cells both in vitro and in vivo. 32,34 To strengthen further these observations we compared decorin antitumor effects to those of AG879, using MTLn3 mammary adenocarcinoma cell line as a model.

First, we examined the growth inhibitory effects of decorin and AG879 as single agents. The MTLn3 cell line was chosen due to its overexpression of ErbB2 and its metastatic qualities.36 It is known that the ErbB2 kinase inhibitor AG879 has at least 500-fold higher selectivity for ErbB2 (IC50 = 1 μmol/L) than EGFR (IC50 > 500 μmol/L) in cell-free systems.35 ED50 values of decorin core and AG879 were 1.04 and 3.16 μmol/L, respectively, as determined by cell count on 48-hour treatment in multiple (n = 3 to 12) independent assays (Table 1). The ED50 value, defined as the concentration that affects 50% of the total cell population, was chosen over IC50 value, defined as the concentration that inhibits 50% of the maximal cell population, due to the fact that decorin-induced growth inhibition reached a plateau at about 65% of the total cell population, whereas the AG879 effect reached plateau at about 95% (data not shown). Thus, ED50 values were considered more comparable than IC50 values.

Table 1.

ED30, ED50, and ED60 Values for Decorin Core, AG879 as Single Agents or in Combination in MTLn3 Cells*

| Treatment | ED30 (μM) | ED50 (μM) | ED60 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decorin core† | 0.29 | 1.04 | 1.92 |

| AG879‡ | 1.81 | 3.16 | 4.12 |

| Decorin core/AG879§ | 0.04/0.22 | 0.19/0.59 | 0.60/1.29 |

ED30, ED50, ED60 = effective dose/concentration that affects 30%, 50%, 60% of the total cell population.

Decorin core concentrations ranged from 0.01 to 4 μmol/L. For each data point n = 3 to 12.

AG879 concentrations ranged from 1 to 20 μmol/L. For each data point n = 3 to 9.

Concentrations of single agents used in the combination treatment were 4/3, 1, 2/3, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, 1/8, and 1/15 of their obtained ED30, ED50, and ED60 values.

For each data point n = 3.

Combination therapy to target multiple pathways involved in tumorigenesis represents the future in clinical trials; therefore, we tested decorin core and AG879 effect on cell proliferation when used in combination. ED50 value of AG879 was ∼ threefold higher than decorin core, when used as single agent. Therefore, in combination experiments, we tested AG879 to decorin core concentrations at a 3:1 ratio. Concentrations of AG879 were 4.2, 3.16, 2.1, 1.58, 1.05, 0.79, 0.4, and 0.2 μmol/L, corresponding to 4/3, 1, 2/3, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, 1/8, and 1/15 of its ED50 (n = 3). Dose-effect curves showed a concentration-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation in both single treatments (Figure 1A). The median-effect plot39,45 provided the ED50 values of the agents used alone or in combination as determined from the x axis intersection of the lines, where log (Fa/Fu) = 0 (Fa = fraction of cells affected by the treatment; Fu = fraction of unaffected cells). We observed a “left” shift of the line representing the treatment of decorin core and AG879 in combination (Figure 1B, yellow diamonds), suggesting that MTLn3 cells are more sensitive to the combination of decorin core and AG879 than to the single agents. Significantly, a 5.4-fold decrease in the concentration of AG879 and decorin core was required to inhibit 50% of the tumor cell proliferation when used in combination vis-à-vis the single agents (Table 1). When the obtained ED30, ED50, and ED60 values were plotted as an isobologram,39 the data clearly showed that the two agents achieved a synergistic effect in inhibiting cell proliferation, insofar as all data points obtained in the combination fell below the “additive effect” line defined by the concentrations of the single agents (Figure 1C, arrows). The synergistic effect was further demonstrated by combination index analysis. Doses of the single agents or the agents used in combination were calculated for a range of given effects (fractional effect = 0.1 to 0.8) using the median-effect equation (Figure 1d).39 All of the combination index values fell below 1.0, ranging between 0.3 and 0.7, indicating a grade of synergism between “moderate” (0.7 to 0.85) and “strong” (0.1 to 0.3).39

Figure 1.

Synergistic effects on tumor cell growth by combinatorial treatment with decorin and AG879. A: Dose-effect curve was obtained for AG879 and decorin alone or in combination. The dose ratio used for the combination was 3:1, AG879 to decorin. In this case, the percentage of growth inhibition was plotted against the concentrations of AG879 used in the combinations. Values represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals. B: Median-effect plot was obtained by plotting the value of log (fa/fu) against log (D). Fa is fraction of cells affected by treatment, whereas Fu is fraction of cells unaffected. D is the dose; log (fa/fu) values obtained for combination treatment are plotted against decorin doses used in the combination. Anti-logs of the x axis intercept values signify the potency of each drug, where fa/fu = 1 or log (fa/fu) = 0, gives their ED50 value. C: Isobologram using ED30, ED50, and ED60 values of decorin and AG879 as indicated on the X- and Y-axes, respectively. Concentrations of decorin and AG879 in combination that induce similar inhibitory effects are plotted to compare with single drug effect. Note that all of the obtained values fall to the left of the lines (arrows) defined by the concentration of single agents which represent additive effect. D: Combination index values of AG879 and decorin at a 3:1 ratio were plotted against their fractional effect. Combination index value of 1, <1, or >1 signifies an additive, synergistic or antagonistic effect, respectively. In all experiments growth inhibition of MTLn3 cells treated for 48 hours with decorin, AG879 or in combination was measured by cell count (n = 3 to 12).

Inhibition of Anchorage-Independent Cell Growth, Migration, and Invasion

To further examine the significance of the synergistic effect of decorin and AG879, we tested the ability to inhibit anchorage-independent cell growth both as single agents and in combination. The results showed that decorin and AG879 alone or in combination inhibited colony formation (Figure 2A). To quantitatively evaluate this effect, we considered two parameters: total colony number and colony size. The data, collected from two independent experiments run in triplicate, showed that both decorin and AG879 used as single agents were effective in inhibiting the number of MTLn3 colonies (Figure 2B, ***P < 0.001, n = 6). In this regard, decorin’s effect was more prominent than that induced by AG879 (∼70% inhibition compared to ∼20%). Combination of decorin and AG879 inhibited colony formation by ∼85% (Figure 2B, ***P < 0.001, n = 6), suggesting the occurrence of an additive rather than a synergistic effect.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of tumor cell colony formation and size by decorin and AG879 alone or in combination. A: MTLn3 cell colonies grown in soft agarose for 10 days in the presence or absence of the designated agents. Plates were treated with 1.04 μmol/L decorin, 3.16 μmol/L AG879 alone, or 1.04 μmol/L decorin and 3.16 μmol/L AG879, in combination. Photos are representative of each condition. Scale bar = 200 μm. B: Total number of colonies counted per photographic field. Each field is approximately 3.75 mm2 of culture dish. Values represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (***P < 0.001, n = 6). C: Average colony size on the indicated treatment. Colony areas were measured with ImageJ software. Values represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (***P < 0.001, n = 6). D: Distribution of colonies size following the specified treatment. Size I = 50 to 70 μm, Size II = 70 to 100 μm and Size III >100 μm. All data were collected from two independent experiments. Within each experiment, each treatment was run in triplicate. P values of each treatment are relative to the control value.

The average colony size was reduced by 25%, 45%, and 60% after a 10-day treatment with AG879, decorin or in combination, respectively (Figure 2C, ***P < 0.001, n = 6). Colonies were also categorized within different size groups of small (Size I, 50 to 70 μm), medium (Size II, 70 to 100 μm), and large (Size III, >100 μm) dimensions. Interestingly, the combination treatment caused a remarkable shift of the size distribution toward smaller colonies as compared with control (Figure 2D). These results support the growth inhibition presented above and show that the two agents significantly reduce the ability of this breast carcinoma cell line to grow in soft agar, suggesting antimetastatic potential. To further assess the potential role of decorin and AG879 in inhibiting metastatic formation, we performed wound healing assays as a measure of cell motility (supplemental Figure S1, A and B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org, *P < 0.05, n = 3) and Matrigel assays as a measure of invasion through a three-dimensional matrix (supplemental Figure S1 C and D at http://ajp.amjpathol.org, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n = 5). Both decorin and AG879 inhibited cell migration (by ∼60%) as well as invasion (by ∼40%), but no synergism was observed.

Pro-Apoptotic Effects of Decorin

Next, we established whether decorin would induce apoptosis in MTLn3 cells. MTLn3 cells were cultured for 48 hours with decorin (1.04 μmol/L), AG879 (3.16 μmol/L) alone or in combination. Cells were then fixed and their nuclei stained to visualize morphological changes. Typically, nuclei of cells that are undergoing apoptosis (apoptotic bodies), show features such as condensation and fragmentation47 that can be detected by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3, A and B, arrows). Quantification of 10 random fields for each condition showed that decorin and AG879 increased the amount of apoptotic bodies by 70% and 50% over control levels, respectively (Figure 3C, ***P < 0.001, n = 30). When used in combination, decorin and AG879 caused 100% increase (Figure 3C, ***P < 0.001, n = 30).

Figure 3.

Effect of decorin, AG879, and the combination on apoptosis. A, B: MTLn3 cells were left untreated or treated with 1.04 μmol/L decorin for 48 hours before 4′-6-diamindino-2-phenylindole staining. Arrows indicate apoptotic bodies. Scale bar = 60 μm. C: Quantification of percentage of apoptotic bodies from two independent experiments. Each condition n = 30 (***P < 0.001). D: Percentage of apoptotic cells measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting/DNA fragmentation analysis. MTLn3 cells were exposed to ED50 of decorin, AG879 (1.04 and 3.16 μmol/L, respectively) or their combination for 48 hours, as indicated, and stained with propidium iodide. Data were collected from three independent experiments and each condition was performed in triplicate. Values represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n = 9).

We further investigated apoptosis by DNA fragmentation analysis and fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Decorin and AG879 alone doubled the percentage of apoptosis (∼4% versus ∼2% in control samples) (Figure 3D, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01). Remarkably, when they were used in combination, apoptosis increased by ∼ 3.5-fold (∼7% versus ∼2%) (Figure 3D, ***P < 0.001). These data indicate that decorin and AG879 used in combination lead to a greater-than-additive effect.

Inhibition of Orthotopic Breast Cancer Growth and Metabolism, and Reduction of Pulmonary Metastases by Systemic Delivery of Decorin

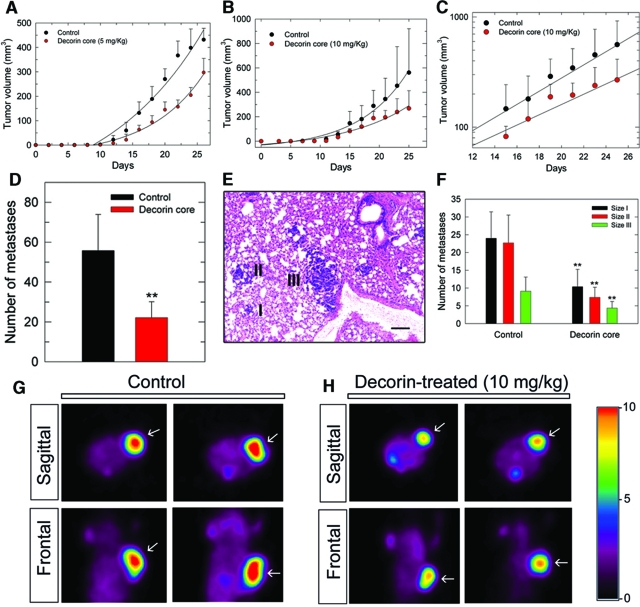

We evaluated the effects of systemic delivery of recombinant decorin on the growth kinetics of established breast carcinoma xenografts. Female severe-combined immunodeficient mice were injected into the upper right mammary fat pad with ∼106 MTLn3 cells. We performed four in vivo experiments using a total of 40 mice. The results obtained with a low dosage of decorin (∼5 mg/kg) showed a significant growth inhibition of the tumor xenografts (Figure 4A). The treatment effect was analyzed by two-way RM analysis of variance statistics and showed to be significant (P = 0.0006). When the dosage was increased to 10 mg/kg, we observed a greater growth inhibition (Figure 4B, P = 0.031). The basis for the size difference at day 25 was primarily due to a growth rate advantage, insofar as the doubling time for the vehicle-treated tumors was shorter than that of the decorin-treated animals (4.5 vs. 7.1 day, respectively) (Figure 4C). Remarkably, quantitative analysis of the pulmonary metastases showed that systemic delivery of decorin significantly reduced their number (Figure 4D, P = 0.002). The metastatic nodules were separated into three classes of increasing size (Figure 4E). In the decorin-treated mice the overall reduction was 60% for size I (P = 0.005), 70% for size II (P = 0.001), and 55% for size III (P = 0.039) (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Effects of decorin on orthotopic mammary adenocarcinoma growth, metastatic spreading, and metabolism. A: Growth of MTLn3 tumor xenografts in severe-combined immunodeficient mice treated with decorin (5 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS). Treatment was started at day 4 post-tumor cell injections. At day 12 tumor diameters were measurable by caliper and converted to volumes using the equation a (b2/2), where a and b represent the larger and smaller diameters, respectively. Measurements were taken every other day. Data were collected from three independent experiments and represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (n = 12 control, n = 11 decorin-treated). The effect of decorin on tumor growth was statistically validated by two-way RM analysis of variance. Treatment effect P = 0.0006; sampling time effect P < 0.001; treatment × sampling time effect P < 0.001; difference in mean tumor volume on the last experimental day = 134.6 mm3, mean control tumor volume = 431.5 mm3, mean decorin-treated tumor volume = 296.9 mm3, 95% CI = 238.7 to 355.1, P = 0.003. B: Same experiment as in A using double amount of decorin (10 mg/kg). Data were collected from one experiment and represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (n = 4 control, n = 5 decorin-treated). Treatment effect P = 0.031; sampling time effect P < 0.001; treatment × sampling time effect P < 0.001; difference in mean tumor volume on the last experimental day = 293 mm3, mean control tumor volume = 561.9 mm3, mean decorin-treated tumor volume = 268.9 mm3, 95% CI = 124.3 to 413.5, P = 0.063. C: Same data as in B (from day 15) presented by linear regression. D–F: Quantitative analysis of pulmonary metastasis number and size. Lungs were perfused-fixed with 10% buffered formaldehyde, paraffin-embedded, sectioned at multiple levels (10 levels every 50 μm), and stained with H&E to visualize metastases (blue nodules stained differentially from surrounding lung tissue). Size I = 50 to 70 μm, Size II = 70 to 100 μm, Size III = > 100 μm. Data represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (n = 10 control, n = 8 decorin-treated, **P < 0.01). Scale bar = 40 μm. G–H: Sagittal and frontal PET scan images of two control and two decorin-treated tumors. Notice the marked reduction in metabolism in the treated tumors (arrows). For signal intensity refer to the scale bar on the right.

Next, we determined whether decorin could inhibit in vivo tumor growth by affecting tumor metabolism. To this end, eight animals from separate experiments were analyzed by CT and PET scan. This strategy allows for direct visualization and quantification of tissue metabolic activity via the administration of a radioactive sugar, [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose, which proportionally distributes to metabolically active tissue. The results showed a dramatic difference in tumor metabolic activity caused by decorin treatment (Figure 4, G and H). Quantification of a pool of animals (n = 4) by normalizing the maximal signal in each tumor to that in the abdomen showed a ∼40% difference in tumor metabolic rate. Tumor mass identification and volumes were verified by concurrent CT scanning, and these values supported the results obtained by manual measurements (supplemental Figure S2A at http://ajp. amjpathol.org). Note that in the PET scans, the largest tumors within the decorin-treated group were chosen to avoid obtaining differences in the metabolic rate non-specifically connected to differences in tumor volume. Importantly, decorin-treated animals bearing tumors of a size comparable to controls, showed a decrease in the number of pulmonary metastases (supplemental Figure S2C at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Slowing Primary Breast Cancer Growth and Metabolism by Systemic Delivery of Decorin and AG879

Next, we determined whether decorin and AG879 could synergistically slow in vivo tumor growth. Four days after tumor cell inoculation, treatment was commenced by intraperitoneal administration of decorin (3 mg/kg), AG879 (20 mg/kg), or in combination. The concentration of anilinoquinazoline compounds to be used in vivo has been reported.35 Before treatment regimen started, five mice were randomized in each experimental arm. AG879 was dissolved in a hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin Trappsol solution.46 Control animals received Trappsol. Individual or combined agents were administered every other day and tumors were measured for 26 days. Decorin, AG879 and the combination had a statistically significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth without any overt side effects (Figure 5A, P = 0.006, P = 0.005, and P = 0.001, respectively).

Figure 5.

Effects of decorin on breast tumor growth and metabolism as compared with AG879. A: Growth of MTLn3 orthotopic tumor xenografts in severe-combined immunodeficient mice treated every other day with decorin (3 mg/kg), AG879 (20 mg/kg), both AG879 and decorin (at the same dosage as when used alone), or Trappsol. Treatments were started at day 4 post-tumor cell injections (P = 0.003). Decorin group: treatment effect P = 0.006; sampling time effect P < 0.001; treatment × sampling time effect P < 0.001; difference in mean tumor volume on the last experimental day = 243.7 mm3, mean control tumor volume = 532.3 mm3, mean decorin-treated tumor volume = 288.6 mm3, 95% CI = 240.7 to 336.5, P = 0.005. AG879 group: treatment effect P = 0.005; sampling time effect P < 0.001; treatment × sampling time effect P < 0.001; difference in mean tumor volume on the last experimental day = 248.7 mm3, mean control tumor volume = 532.3 mm3, mean AG879-treated tumor volume = 283.6 mm3, 95% CI = 226 to 341.2 P = 0.004. Combination group: treatment effect P = 0.001; sampling time effect P < 0.001; treatment × sampling time effect P < 0.001; difference in mean tumor volume on the last experimental day = 266.4 mm3, mean control tumor volume = 532.3 mm3, mean combination-treated tumor volume = 265.9 mm3, 95% CI = 202 to 329.8, P = 0.003. B: Sagittal and frontal PET scan images of representative tumors as indicated. For signal intensity refer to the scale bar on the right. Arrows point to the tumor xenografts. C: Fluorescence microscopy images of one control and one decorin-treated tumor. Frozen sections were double-stained with an anti-CD31 antibody to visualize blood vessels (red) and an anti-His antibody to detect recombinant decorin within the tumor tissue (green). Scale bar = 150 μm. Arrows point to intense deposits of decorin.

In summary, decorin, AG879 and their combination inhibited primary breast tumor growth by 46%, 47%, and 51%, respectively. Decorin and AG879 effects in inhibiting tumor growth were comparable but no synergism of decorin and AG879 was observed. At the end of each in vivo experiment the mice were dissected and the final tumor volumes were measured. These measurements were in accordance with the volumes assessed while the animals were alive and are plotted as last points in the tumor growth graphs.

PET scan analysis demonstrated that the three regimens caused a 30% decrease in the primary tumor metabolism (Figure 5B). Tumor volumes were verified by concurrent CT scanning (supplemental Figure S2B at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Decorin Targets Breast Cancer Cells in Vivo and Reduces ErbB2 Levels

Having established that systemic delivery of decorin retards in vivo tumor growth, we investigated whether decorin would specifically target the ErbB2-overexpressing tumor cells. We discovered that decorin is specifically localized to the orthotopic tumors with intervening areas lacking any signal (Figure 5C, arrows). No detectable decorin was found in various organs (supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org), suggesting highly favorable tumor localization over normal organs.

Notably, decorin treatment caused a marked suppression of tumor cell-associated ErbB2 (Figure 6, A and B). The ErbB2 fluorescence intensity was analyzed and quantified by three-dimensional surface plot (Figure 6, C and D). The results clearly demonstrated that systemically delivered decorin caused a significant reduction in the receptor amount (Figure 6E, ***P < 0.001, n = 30).

Figure 6.

In vivo down-regulation of ErbB2 receptor by decorin. A,B: Immunohistochemical analysis of MTLn3 vehicle- and decorin-treated tumor using an anti-ErbB2 antibody (green, arrows) and 4′-6-diamindino-2-phenylindole (blue). Scale bar = 100 μm. C,D: Three-dimensional surface plot images as determined by ImageJ software analysis of fluorescence intensity of the FITC channel. E: Quantification of fluorescence intensity representing the expression of ErbB2 in various tumor sections from control and decorin-treated mouse. Values represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (n = 30, ***P < 0.001).

Decorin-Evoked Inhibition of Pulmonary Metastases

We performed additional in vivo experiments (40 animals) to determine the specific effect of decorin on the generation of pulmonary metastases (Figure 7A). Quantification of the number of metastases per mouse revealed that decorin treatment had a dramatic effect in reducing metastatic spreading to the lungs (Figure 7B, **P < 0.01). AG879 did not have any appreciable effect, suggesting that the antimetastatic activity observed in the combination was primarily due to decorin (Figure 7B, *P < 0.05). Interestingly, after treatment with AG879, the total number of metastases was equal to control but the average metastasis size was smaller (supplemental Figure S2 days at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These findings were validated by a novel molecular approach to detect metastatic tumor cells. The presence of MTLn3 cells in the lungs was visualized by performing PCR on DNA extracted from lung samples, using primers for a subfamily of vomeronasal receptor genes that are specific for the rat.43 The rat-specific band is 645 bp (Figure 7, C and D) whereas the non-specific band from mouse DNA is ∼900 bp. Both rat- and mouse-derived bands were quantified by densitometry and the mouse bands were used as loading controls to obtain normalized values (Figure 7E, **P < 0.01). The results strongly support the data obtained with morphological analysis thereby strengthening the concept that decorin reduces the metastatic burden to the lungs.

Figure 7.

Decorin-mediated suppression of metastatic spreading to the lungs. A: Photomicrographs of pulmonary metastases (arrows) from representative mice treated as indicated. The arrows indicate the metastatic nodules. Scale bar = 200 μm. B: Quantification of pulmonary metastases in each treatment group, as indicated. Values represent the means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Five lungs per treatment group were collected and from each lung 10 sections, 10 μm apart, were obtained. Metastases were counted from each section. C: Agarose gel of a representative PCR of mouse and rat DNA (mDNA and rDNA, respectively) using primers specific for the rat vomeronasal receptors (V1rm3 and V1rm4). The rat-derived (MTLn3) product is a 645-bp band (lane 2), while the 900-bp band is mouse-derived and serves as loading control (lane 1). Lanes 3–5 represent different ratios of mDNA/rDNA: 50/50, 50/10, and 50/1 ng, respectively. D: PCR for rat vomeronasal receptors of control and various treatments as indicated. Arrow indicates the 645-bp band specific for rat DNA, which represents MTLn3-derived DNA within the mouse lung. E: Quantification of metastatic pulmonary burden from lung tissue using the PCR approach described in (D). Bar graph was obtained by normalizing mean absorbance units of rat DNA over mouse DNA. Values represent means with their upper 95% confidence intervals (n = 5, **P < 0.01).

Discussion

The central hypothesis of our research is that decorin binds to and down-regulates its main functional receptor, the EGFR, thereby affecting a wide variety of solid tumors in which EGFR or other members of the ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase family are overexpressed or misregulated.32,34 In the present work we sought to reproduce a scenario that is the closest possible to a clinical situation by using an animal model of orthotopic breast carcinoma which spontaneously metastasizes to the lungs. We first studied decorin’s effect on MTLn3 cells in vitro. We provide strong evidence that decorin inhibits MTLn3 cell proliferation, in a dose-dependent fashion, as well as anchorage-independent cell growth and colony formation. Notably, decorin also slows cell motility and impedes cell invasion through a three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Moreover, decorin induces significant apoptosis. We have shown before that tumor cells of various histological origin engineered to express decorin undergo cell cycle arrest in G1 phase and that this effect is due to p21 expression.11 It is logical that the selected decorin-expressing clones did not undergo apoptosis. More recently, we have proposed that decorin causes apoptosis of A431 squamous carcinoma cells via caspase-3 activation and that EGFR phosphorylation is required for the outcome.32 Most likely, decorin induces apoptosis of MTLn3 cells by interacting with the EGFR and also by disrupting EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers. It is reasonable to speculate that cells that express different receptors amounts and require different receptors for their growth would be differently affected by decorin. Therefore, decorin can induce both growth arrest and apoptosis. An important aspect of our study was to compare the effects of decorin to those evoked by AG879, an established tyrosine kinase inhibitor. AG879 is member of a family of small molecules, anilinoquinazoline, that are considered potential drugs against various types of cancer35; it is important to note that gefitinib (Iressa) and erlotinib, currently in clinical trials, are part of this family of compounds. Notably, AG879 also inhibits MTLn3 cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner but with an ED50 ∼3 times higher than that of decorin (3.16 vs. 1.04 μmol/L). Furthermore, AG879 treatment reduces colony number and size in soft agar assays, although its effect is less dramatic than that of decorin, along with inhibiting cell motility and invasion. It also induces a degree of apoptosis comparable to the one induced by decorin.

In this study orthotopic MTLn3 tumor xenografts were treated for the first time via systemic delivery of decorin. The size of treated primary tumors was reduced by ∼50%, depending on the amount of decorin injected. This successful outcome is explained by reduction of growth rate and inhibition of tumor metabolism, which is directly related to tumor angiogenesis and inversely related to tumor cell toxicity. The most striking and clinically relevant observation from our in vivo studies is the ability of decorin to prevent metastatic spreading to the lungs. These data were validated by quantification of the metastatic nodules in the lungs and further corroborated by a novel molecular approach that detects traces of metastatic cells of rat origin in the mouse lungs. Remarkably, there is no direct relationship between primary tumor size and number of pulmonary metastases, suggesting that decorin mechanism of action has a specific effect in halting metastatic dissemination.

Although AG879 also shows to be effective against tumor growth and metabolism, the combinatorial treatment with decorin only slightly increases the inhibitory effect in comparison to the single agents. Thus, while in vitro decorin and AG879 have a significant synergistic effect, this does not occur in vivo. Moreover, despite its inhibitory effect on primary tumor growth, AG879 treatment was not capable of halting metastatic spreading to the lungs. Although the total number of metastases was not reduced by AG879, we noticed that the average size shifted toward the smaller dimensions. These data indicate that AG879 does not prevent cancer cell detachment from the primary tumor but might just affect the size of the secondary lesion by affecting cell proliferation. In contrast, decorin treatment prevents metastatic spreading. A possible explanation for these results is that decorin directly targets the EGFR,14,15 which promotes cell motility and intravasation of MTLn3 cells.48 In the present study, we also show that decorin reduces the amount of ErbB2 receptor in the tumor. This result is in line with our previous finding that de novo expression of decorin leads to a profound inhibition of the steady state levels of ErbB2 phosphorylation in ErbB2-overexpressing human mammary carcinoma cells.49 Concurrently, the decorin-expressing cells become growth retarded, undergo cytodifferentiation toward a benign phenotype and fail to generate tumors in mice.49 Decorin targeting multiple receptors, directly or indirectly, could explain its striking effect on blocking metastatic spreading when compared to AG879. It is interesting to note that AG879 showed potential in vitro to interfere with cell motility and invasion but this ability did not transfer to the complex in vivo environment. On the contrary to AG879, decorin acts as a pan-ErbB receptors inhibitor and most likely it affects various receptor tyrosine kinases. Certainly, decorin’s mechanism of action requires more investigation. In the future we will seek to understand the signaling pathways affected and also possible interactions of decorin with other receptors such as the Met receptor. The aberrant activation of this receptor has been associated with high tumor invasiveness and poor prognosis.50,51 This idea is supported by the evidence that LRIG1, a leucine-rich protein homologous to decorin,52 directly binds to and negatively regulates the Met receptor.53 In vivo studies will need to be expanded to better understand at what stage of tumor growth and metastastic spreading decorin is most effective and at what concentration.

This study has several limitations. First, all of the results are based on a single cell line. Moreover, investigations are limited by the availability of good antibodies directed toward rat epitopes. For this reason, we were not able to investigate apoptosis in vivo via biochemical means, such as detection of active caspase-3. In the future, we will investigate further decorin-evoked signaling that leads to apoptosis. Also, these cells are extremely susceptible to serum-free medium conditions in which they undergo significant apoptosis. Nevertheless, our data do provide strong evidence in support of decorin as an effective and powerful antitumor, as well as antimetastatic agent that deserves consideration as a future therapeutic modality for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Interestingly, it has been recently proposed that transforming growth factor β induced by anticancer therapies promotes tumor metastases based on the effects of transforming growth factor β-neutralizing antibodies.54 Because decorin can inhibit tumor growth by blocking transforming growth factor β activity,16,17 in addition to targeting multiple signaling pathways,8 it could represent a more successful anticancer therapy by its virtue of antagonizing tumor cell invasion. Considering that metastatic spread is the leading cause of mortality in cancer patients, clinical testing of a natural inhibitor of primary tumor growth and metastatic spreading such as decorin should be promoted in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Cardi for performing PET/CT scan analysis and quantification.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Renato V. Iozzo, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Room 249 JAH, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107. E-Mail: iozzo@mail.jci.tju.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 CA39481, RO1 CA47282, and RO1 CA120975 (to R.V.I.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http:// ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Iozzo RV. The family of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: key regulators of matrix assembly and cellular growth. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:141–174. doi: 10.3109/10409239709108551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking AM, Shinomura T, McQuillan DJ. Leucine-rich repeat glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18843–18846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Iozzo RV. The role of decorin in collagen fibrillogenesis and skin homeostasis. Glycoconj J. 2003;19:249–255. doi: 10.1023/A:1025383913444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV. Matrix proteoglycans: from molecular design to cellular function. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:609–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tralhão JG, Schaefer L, Micegova M, Evaristo C, Schönherr E, Kayal S, Veiga-Fernandes H, Danel C, Iozzo RV, Kresse H, Lemarchand P. In vivo selective and distant killing of cancer cells using adenovirus-mediated decorin gene transfer. FASEB J. 2003;17:464–466. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0534fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglari A, Bataille D, Naumann U, Weller M, Zirger J, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Effects of ectopic decorin in modulating intracranial glioma progression in vivo, in a rat syngeneic model. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2004;11:721–732. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Biological functions of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: from genetics to signal transduction. J Biol Chem In press. 2008;238:21305–21309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800020200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV, Moscatello D, McQuillan DJ, Eichstetter I. Decorin is a biological ligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4489–4492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra M, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Lattime EC, Iozzo RV. De novo decorin gene expression suppresses the malignant phenotype in human colon cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7016–7020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra M, Mann DM, Mercer EW, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Iozzo RV. Ectopic expression of decorin protein core causes a generalized growth suppression in neoplastic cells of various histogenetic origin and requires endogenous p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:149–157. doi: 10.1172/JCI119507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscatello DK, Santra M, Mann DM, McQuillan DJ, Wong AJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin suppresses tumor cell growth by activating the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:406–412. doi: 10.1172/JCI846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordás G, Santra M, Reed CC, Eichstetter I, McQuillan DJ, Gross D, Nugent MA, Hajnóczky G, Iozzo RV. Sustained down-regulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by decorin. A mechanism for controlling tumor growth in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32879–32887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra M, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Decorin binds to a narrow region of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor, partially overlapping with but distinct from the EGF-binding epitope. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35671–35681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-X, Goldoni S, Bix G, Owens RA, McQuillan D, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Decorin evokes protracted internalization and degradation of the EGF receptor via caveolar endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32468–32479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Mann DM, Ruoslahti E. Negative regulation of transforming growth factor-b by the proteoglycan decorin. Nature. 1990;346:281–284. doi: 10.1038/346281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ständer M, Naumann U, Dumitrescu L, Heneka M, Löschmann P, Gulbins E, Dichgans J, Weller M. Decorin gene transfer-mediated suppression of TGF-b synthesis abrogates experimental malignant glioma growth in vivo. Gene Therapy. 1998;5:1187–1194. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ständer M, Naumann U, Wick W, Weller M. Transforming growth factor-b and p-21: multiple molecular targets of decorin-mediated suppression of neoplastic growth. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:221–227. doi: 10.1007/s004410051283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous Z, Wei VM, Iozzo RV, Höök M, Grande-Allen KJ. Decorin-transforming growth factor-β interaction regulates matrix organization and mechanical characteristics of three-dimensional collagen matrices. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35887–35898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti G, Bertoni A, Viola M, Tira E, Balduini C, Torti M. The small proteoglycan decorin supports adhesion and activation of human platelets. Blood. 2002;100:1707–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer L, Macakova K, Raslik I, Micegova M, Gröne H-J, Schönherr E, Robenek H, Echtermeyer FG, Grässel S, Bruckner P, Schaefer RM, Iozzo RV, Kresse H. Absence of decorin adversely influences tubulointerstitial fibrosis of the obstructed kidney by enhanced apoptosis and increased inflammatory reaction. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1181–1191. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64937-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järveläinen HT, Iruela-Arispe ML, Kinsella MG, Sandell LJ, Sage EH, Wight TN. Expression of decorin by sprouting bovine aortic endothelial cells exhibiting angiogenesis in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1992;203:395–401. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järveläinen H, Puolakkainen P, Pakkanen S, Brown EL, Höök M, Iozzo RV, Sage H, Wight TN. A role for decorin in cutaneous wound healing and angiogenesis. Wound Rep Reg. 2006;14:443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr E, Levkau B, Schaefer L, Kresse H, Walsh K. Decorin-mediated signal transduction in endothelial cells. Involvement of Akt/protein kinase B in up-regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 but not p27KIP1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40687–40692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr E, Sunderkotter C, Schaefer L, Thanos S, Grässel S, Oldberg Å, Iozzo RV, Young MF, Kresse H. Decorin deficiency leads to impaired angiogenesis in injured mouse cornea. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:499–508. doi: 10.1159/000081806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella MG, Fischer JW, Mason DP, Wight TN. Retrovirally mediated expression of decorin by macrovascular endothelial cells. Effects on cellular migration and fibronectin fibrillogenesis in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13924–13932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange Davies C, Melder RJ, Munn LL, Mouta-Carreira C, Jain RK, Boucher Y. Decorin inhibits endothelial migration and tube-like structure formation: role of thrombospondin-1. Microvasc Res. 2001;62:26–42. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant DS, Yenisey C, Rose RW, Tootell M, Santra M, Iozzo RV. Decorin suppresses tumor cell-mediated angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2002;21:4765–4777. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo RV, Chakrani F, Perrotti D, McQuillan DJ, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Eichstetter I. Cooperative action of germline mutations in decorin and p53 accelerates lymphoma tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3092–3097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troup S, Njue C, Kliewer EV, Parisien M, Roskelley C, Chakravarti S, Roughley PJ, Murphy LC, Watson PH. Reduced expression of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans, lumican, and decorin is associated with poor outcome in node-negative invasive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler DG, Goldoni S, Agnew C, Cardi C, Thakur ML, Owens RA, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin protein core inhibits in vivo cancer growth and metabolism by hindering epidermal growth factor receptor function and triggering apoptosis via caspase-3 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26408–26418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Gauldie J, Iozzo RV. Suppression of tumorigenicity by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of decorin. Oncogene. 2002;21:3688–3695. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Waterhouse A, Kirby S, Kay P, Owens RA, McQuillan DJ, Iozzo RV. Decorin prevents metastatic spreading of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitzki A, Gazit A. Tyrosine kinase inhibition: an approach to drug development. Science. 1995;267:1782–1788. doi: 10.1126/science.7892601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri A, Welch D, Kawaguchi T, Nicholson GL. Development and biologic properties of malignant cell sublines and clones of a spontaneously metastasizing rat mammary adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1982;68:507–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy P, Hocking AM, McQuillan DJ. Recombinant decorin glycoforms. Purification and structure. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19578–19584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldoni S, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Shriver Z, Sasisekharan R, Birk DE, Campbell S, Iozzo RV. Biologically active decorin is a monomer in solution. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6606–6612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T-C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharm Rev. 2006;58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bix G, Castello R, Burrows M, Zoeller JJ, Weech M, Iozzo RA, Cardi C, Thakur MT, Barker CA, Camphausen KC, Iozzo RV. Endorepellin in vivo: targeting the tumor vasculature and retarding cancer growth and metabolism. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1634–1646. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons-Wingerter P, Kasman IM, Norberg S, Magnussen A, Zanivan S, Rissone A, Baluk P, Favre CJ, Jeffry U, Murray R, McDonald DM. Uniform overexpression and rapid accessibility of a5b1 integrin on blood vessels in tumors. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:193–211. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62965-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grus WE, Zhang J. Rapid turnover of species-specificity of vomeronasal pheromone receptor genes in mice and rats. Gene. 2004;340:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P, Bielawski JP, Yang H, Zhang Y-P. Adaptive diversification of vomeronasal receptor 1 gene in rodents. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:566–576. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0172-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse D, Doughty RS, Ramsey TT, Russell WE, Price JO, Flanagan WM, Shawver LK, Arteaga CL. Reversible G1 arrest induced by inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase requires up-regulation of p27KIP1 independent of MAPK activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6987–6995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Brattain MG. Synergy of epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor AG1478 and ErbB2 kinase inhibitor AG879 in human colon carcinoma cells is associated with induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5848–5856. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AG, Doherty MM, Walker F, Weinstock J, Nerrie M, Vitali A, Murphy R, Johns TG, Scott AM, Levitzki A, McLachlan G, Webster LK, Burgess AW, Nice EC. Preclinical analysis of the analinoquinazoline AG1478, a specific small molecule inhibitor of EGF receptor tyrosine kinase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1422–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Chuang YJ, Jin T, Swanson R, Xiong Y, Leung L, Olson ST. Antiangiogenic antithrombin induces global changes in the gene expression profile of endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5047–5055. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, Wyckoff J, Liang F, Sidani M, Violini S, Tsai K-L, Zhang Z-Y, Sahai E, Condeelis J, Segall JE. Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression results in increased tumor cell motility in vivo coordinately with enhanced intravasation and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:192–197. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra M, Eichstetter I, Iozzo RV. An anti-oncogenic role for decorin: down-regulation of ErbB2 leads to growth suppression and cytodifferentiation of mammary carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35153–35161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. MET, metastasis, motility and more. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:915–925. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp RL, Rimm EB, Rimm DL. Met expression is associated with poor outcome in patients with axillary lymph node negative breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:2259–2265. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991201)86:11<2259::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldoni S, Iozzo RA, Kay P, Campbell S, McQuillan A, Agnew C, Zhu J-X, Keene DR, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. A soluble ectodomain of LRIG1 inhibits cancer cell growth by attenuating basal and ligand-dependent EGFR activity. Oncogene. 2007;26:368–381. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck DL, Miller JK, Laederich M, Funes M, Petersen H, Carraway KLI, Sweeney C. LRIG1 is a novel negative regulator of the Met receptor and opposes Met and Her2 synergy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1934–1946. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00757-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Guix M, Rinehart C, Dugger TC, Chytil A, Moses HL, Freeman ML, Arteaga CL. Inhibition of TGF-b with neutralizing antibodies prevents radiation-induced acceleration of metastatic cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1305–1313. doi: 10.1172/JCI30740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]