Abstract

To examine the role of matrilysin (MAT), an epithelial cell-specific matrix metalloproteinase, in the normal development and function of reproductive tissues, we generated transgenic animals that overexpress MAT in several reproductive organs. Three distinct forms of human MAT (wild-type, active, and inactive) were placed under the control of the murine mammary tumor virus promoter/enhancer. Although wild-type, active, and inactive forms of the human MAT protein could be produced in an in vitro culture system, mutations of the MAT cDNA significantly decreased the efficiency with which the MAT protein was produced in vivo. Therefore, animals carrying the wild-type MAT transgene that expressed high levels of human MAT in vivo were further examined. Mammary glands from female transgenic animals were morphologically normal throughout mammary development, but displayed an increased ability to produce β-casein protein in virgin animals. In addition, beginning at approximately 8 mo of age, the testes of male transgenic animals became disorganized with apparent disintegration of interstitial tissue that normally surrounds the seminiferous tubules. The disruption of testis morphology was concurrent with the onset of infertility. These results suggest that overexpression of the matrix-degrading enzyme MAT alters the integrity of the extracellular matrix and thereby induces cellular differentiation and cellular destruction in a tissue-specific manner.

INTRODUCTION

The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of extracellular proteases thought to be responsible for normal matrix remodeling and pathological tissue destruction by virtue of their ability to catabolize extracellular matrix components (Birkedael-Hansen et al., 1993; Hulboy et al., 1997 for review). The expression pattern of MMPs in normal tissues suggests that they are particularly involved in the remodeling associated with reproductive processes, including menstruation, trophoblast invasion, mammary gland morphogenesis, and involution of the uterus, mammary gland, and prostate (Hulboy et al., 1997). Studies with natural and synthetic inhibitors of MMPs (Brannstrom et al., 1988; Butler et al., 1991; Talhouk et al., 1992; Marbaix et al., 1996) and recent experiments that utilized genetically altered mice that express altered MMP substrates (Liu et al., 1995) or lack specific MMP family members (Rudolph-Owen et al., 1997) have confirmed the importance of MMPs in reproductive processes in several systems.

Sixteen MMP family members have been described (reviewed in Hulboy et al., 1997; see also Cossins et al., 1996; Puente et al., 1996). All MMPs described have three essential domains: a signal sequence or predomain to direct secretion from the cell, a pro sequence to maintain latency, and a catalytic domain containing the critical zinc-binding site. Matrilysin (MAT, MMP-7, pump-1, uterine metalloproteinase, EC 3.4.24.23) is unique in that it contains only these minimal domains. All other MMP family members have an additional hemopexin/vitronectin-like domain that is connected to the catalytic domain by a variable hinge region (Birkedael-Hansen et al., 1993 for review). This and other domains found in specific MMP family members generate diversity by modifying properties such as substrate specificity, interaction with endogenous inhibitors of metalloproteinases, intracellular activation, and cell-surface localization (Powell and Matrisian, 1996 for review).

Matrilysin (MAT) is considered a member of the stromelysin subfamily of MMPs. The stromelysins, including stromelysin-1 (STR-1, MMP-3, EC 3.4.24.17), stromelysin-2 (STR-2, MMP-10, EC 3.4.24.22), and MAT, can degrade a broad range of substrates such as fibronectin, proteoglycans, and denatured and basement membrane collagens. Subtle differences in substrate specificity within this subfamily have been observed. For example, although extracellular matrix proteoglycans are substrates for MAT, STR-1, and STR-2, MAT can degrade elastin (Murphy et al., 1991; Imai et al., 1995), entactin (Sires et al., 1993), and tenascin (Imai et al., 1994; Siri et al., 1995) more efficiently than the other stromelysins. MAT is also distinct from most MMP family members in that it is expressed primarily by normal and malignant glandular epithelial cells. MAT is expressed in the epithelial cells of the cycling human endometrium, small intestinal crypts, and postpartum and cycling mouse uterus, as well as epithelial tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, prostate, and breast (Wilson and Matrisian, 1996 for review). The stromelysins and most other MMP family members, in contrast, are expressed primarily in mesenchymal tissues, including endometrial stromal (Hulboy et al., 1997 for review) and stromal cells surrounding several tumor types (Powell and Matrisian, 1996 for review). The unique protein structure, altered substrate specificity, and uncommon localization patterns of MAT suggest that this MMP may have in vivo functions that are distinct from other stromelysins and MMP family members.

Since MMPs are expressed in a variety of reproductive organs and there are features that distinguish MAT from other stromelysins and MMP family members, we were interested in determining the effects of MAT overexpression in reproductive organs. Transgenic mice expressing wild-type, inactive, and constitutively active MAT under the control of the murine mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-long terminal repeat (LTR) were generated, and their affect on mammary gland development and male reproductive function was assessed. The comparison of these transgenic mice with other MMP-expressing mice provides insights into the action of specific MMPs in reproductive processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction

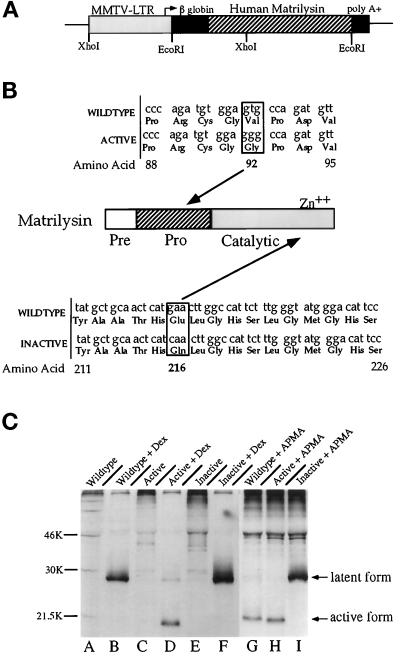

The 1.1-kilobase (kb) full-length human MAT cDNA (pPump-1; Muller et al., 1988) was altered by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. An active form of human MAT with a substitution of valine to glycine at amino acid 92 was generated with the oligonucleotide 5′-CCGGTGTGGTGGGCCCGACGTC-3′ and cloned into pKCR3 (Witty et al., 1994). An inactive form of human MAT with a substitution for glutamic acid to glutamine at amino acid 216 was generated with the oligonucleotide 5′-ATGGCCAAGTTGATGAGTTGC-3′ and also cloned into pKCR3. The resulting full-length human MAT cDNAs (wild-type, active, and inactive, Figure 1B) were subcloned into the unique EcoRI site of the MMTV-LTR expression vector pMMTVEV (Matsui et al., 1990) to generate pMMTV-MAT, pMMTV-ActMAT, and pMMTV-InMAT, respectively (Figure 1A). The expression vector contains intron, splice sites, and polyadenylation signals derived from the rabbit β-globin gene that increase the efficiency of expression (Breathnach and Harris, 1983).

Figure 1.

(A) MMTV-MAT transgenic construct. Diagram of the plasmid construct utilized for creation of transgenics. The filled boxes correspond to the 3′-splice sites and 5′- polyadenylation signals of the rabbit β-globin gene. Three forms of the human MAT cDNA were inserted into the third exon of the β-globin gene. (B) Mutations in the human MAT transgenic constructs. The MAT cDNA sequence and corresponding amino acids are depicted. Boxed areas indicate the position of the nucleotide mutation and amino acid substitution. Active MAT contains a substitution in the pro domain at amino acid 92 from valine to glycine, while inactive MAT contains a substitution in the catalytic domain at amino acid 216 from glutamic acid to glutamine. (C) Immunoprecipitation of the MAT protein. The breast cancer cell line Hs578t was transiently transfected with each MMTV-MAT construct, and the MAT protein immunoprecipitated from the conditioned medium as indicated by the arrows. Dex (100 μM) was added to the culture medium of samples shown in lanes B, D, and F. APMA, a known MMP activator, was added to the conditioned medium of samples shown in lanes G, H, and I.

Human MAT cDNA probes were generated by digesting full-length human MAT in pPump-1 (Muller et al., 1988) with EcoRI and XbaI to remove the poly(A)+ tail. The 1.1-kb human MAT fragment was then subcloned into pGEM7zf(+) to yield pG7 pumpEX. For in situ hybridization, a 356-base pair (bp) fragment of human MAT cDNA corresponding to positions +700 to +1056 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers 5′-CGCGTCTAGACCTCTGATCCTAATGCAG-3′ and 5′-CGCGAAGCTTGACATCTACGCGCACTG-3′. The human MAT fragment was subconed into pGEM7zf(+) to yield pG7-HmatUT and linearized with HindIII or XbaI to generate riboprobe templates for transcription using either T7 (antisense) or SP6 (sense) RNA polymerase, respectively.

Generation of MMTV-MAT Transgenic Mice

The three human MAT constructs, pMMTV-MAT, pMMTV-ActMAT, and pMMTV-InMAT, were purified by CsCl centrifugation, and the Aat II/BglII fragment was then isolated by gel electrophoresis on low melting point agarose (SeaKem Agarose; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) and purified using Gelase (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI). The purified fragments were subsequently injected into FVB/N fertilized eggs by the Vanderbilt Transgenic/ES Cell Shared Resource and transfered to pseudopregnant mothers as described (Hogan et al., 1995). Transgenic founders were identified by Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested genomic tail DNA using a random-primed (DNA Labeling Kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) 1.1-kb EcoRI/XbaI fragment of human MAT from pG7 pumpEX. The approximate copy number of founder transgenic animals was determined by adding 10 pg (1 copy) or 100 pg (10 copies) of MMTV-MAT to genomic DNA from a nontransgenic mouse and comparing relative intensity of hybridization. Transgenic lines were generated by mating founder animals with FVB/N nontransgenic mice.

Immunoprecipitation

The human breast cancer cell line Hs578t was transiently transfected with 10 μg of pMMTV-MAT, pMMTV-ActMAT, or pMMTV-InMAT. The cells were allowed to recover overnight, placed in serum- and methionine-free media for 6 h, and labeled with 100 μCi of [35S]methionine for 14–16 h. The MMTV promoter was induced with 100 μM dexamethasone (Dex) in the culture media for 14–16 h before collection of the conditioned medium. The wild-type, mutant, and inactive MAT protein from 9 × 105 trichloroacetic acid precipitable counts was immunoprecipitated from 35S-labeled conditioned medium using a polyclonal antibody raised against human MAT (McDonnell et al., 1991) and separated on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel. In addition, the MAT protein in the conditioned medium was activated by incubation with 1 mM of the organic mercuride 4-aminophenyl-mercuric acetate (APMA) at 37°C for 30 min before electrophoresis.

Tissue Preparation

The right thoracic and inguinal mammary glands and other organs were removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen or on dry ice and stored at −70°C. Tissue was later homogenized in a guanidinium/acid phenol solution, and total RNA was extracted as described by Chomczynski and Sacchi (1987). Poly(A)+ RNA was then isolated from total RNA over an oligo dT cellulose (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA) column or a latex bead-oligo dT column (Oligotex; Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA).

Left thoracic mammary glands were routinely fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and PBS for whole mount staining, while the left inguinal mammary glands and the testis and epididymis were fixed in paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin for subsequent sectioning.

Northern Analysis

Three to four micrograms of poly(A)+ RNA were electrophoretically separated on a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Micron Separations, Inc., Westborough, MA), and UV cross-linked (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Blots were hybridized at 42°C under high-stringency conditions [50% formamide, 5× SSC, 1× PAF (50× = 10g each polyvinyl pyrrolidine, bovine serum albumin, and ficoll/1), 20 mM NaPO4, 0.1% SDS, 50 μg/ml salmon sperm, and 4% dextran sulfate] using the radiolabeled, random-primed (DNA Labeling Kit; Boehringer Mannhein) 1.1-kb EcoRI/XbaI fragment of the human MAT cDNA, the 700-bp ApaI/HindIII fragment of the mouse MAT cDNA from plasmid pG7-mMATAH (Wilson et al., 1995), or the cDNA for the endogenously expressed cyclophillin gene (1B15; Danielson et al., 1988) to control for RNA loading. Washes were carried out at 50°C in 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS.

In Situ Hybridization

Paraffin-embedded paraformaldehyde-fixed tissue sections 5–7 μm in thickness were placed onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and analyzed for the human MAT transgene expression as previously described (McDonnell et al., 1991). The slides were prehybridized for 2–4 h, after which 35S-labeled riboprobes at 1.2 × 106 cpm/slide were added and hybridized overnight at 50°C. The slides were dipped in photographic emulsion (type NTB2; Kodak, Rochester, NY), exposed for 2 to 4 wk at 4°C, developed, and counterstained with hematoxylin. Background hybridization was assessed using the sense probe for each transcript analyzed.

Whole Mount Analysis

Inguinal and/or thoracic mammary glands were removed and placed flat in plastic embedding cassettes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight, transferred to 70% ethanol, and stored at 4°C. The glands were defatted in 100% acetone and stained with iron hematoxylin (0.1% wt/vol hematoxylin, 0.1 M FeCl3, 0.17 M HCL in 95% EtOH) for 3 h (Medina, 1973). Whole mounted glands were destained in 0.025 M HCl in 50% ethanol, dehydrated to xylene, and stored in 100% methyl salicylate. Glands were viewed using a Nikon dissecting microscope (Southern Micro Instruments, Atlanta, GA).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed, hydrated through graded ethanols, treated with 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in methanol (to destroy endogenous peroxidase activity), microwaved in 0.1 M sodium citrate for 3 min and 45 s at high power to unmask the antigens and exposed to blocking solution (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Tween-20, 1% wt/vol bovine serum albumin, and 5% wt/vol goat serum) for 1 h. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking solution with affinity-purified rabbit anti-human MAT antibody (1:1000 dilution; kindly provided by Dr. William Parks, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO; Saarialho-Kere et al., 1995), or control rabbit IgG (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO). The sections were washed in TBST buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated with biotinylated anti-goat IgG (1:5000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for at least 1 h at room temperature. Labeled cells were visualized using an avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) and TrueBlue peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD). Sections were then counterstained with Contrast Red.

Tissues were similarly processed but without microwave treatment with a rabbit antibody to mouse casein (1:5000 dilution; kindly provided by Dr. Charles Daniel, University of California at Santa Cruz; Robinson et al., 1993), or to proliferating cell nuclear antigen (1:100 dilution; Sigma; Waseem and Lane, 1990).

To localize the transgene protein in the testis and epididymis, tissue was dissected and frozen in OCT medium (Fisher Scientific) and liquid nitrogen. Five-micrometer sections were postfixed in Bouin’s fixative and then washed in PBS for 10 min. Slides were dipped in saturated LiCO3 to eliminate picric acid and washed again in PBS. Sections were analyzed for the expression of human MAT protein as described above for paraformaldehyde-fixed tissues except without microwave treatment.

Analysis of Programmed Cell Death

Paraffin-embedded sections were analyzed for apoptotic cells using a modification of the TUNEL assay (Gavrieli et al., 1992). Tissues were deparaffinized, and endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 1% hydrogen peroxide in ethanol and incubated in chloroform to remove lipids and reduce background levels of staining, as previously described (Witty et al., 1995a). Tissues were then dehydrated and washed with 1× TBS, and free 3′-OH DNA ends were labeled with biotin-conjugated deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim) using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (Life Technologies BRL, Grand Island, NY), followed by a 1:5000 dilution of a horseradish peroxidase-strepavidin–conjugated antibody (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Labeled cells were visualized with 1,2-diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through ethanols to xylene, and coverslipped under Permount.

RESULTS

Generation and Evaluation of MAT Expression Constructs

To determine the effects of ectopic expression of the metalloproteinase MAT on select reproductive organs, the human MAT cDNA was placed under the control of the MMTV-LTR in a vector designed to contain flanking, splice, and polyadenylation sites to improve expression efficiency (Figure 1A). This expression vector has been demonstrated to be effective in directing transgene expression to the murine mammary gland, salivary gland, brain, testes, and epididymis (Matsui et al., 1990; Witty et al., 1995b). Three distinct expression constructs were generated to produce wild-type, constitutively active, and inactive forms of the MAT protein (Figure 1B). The constitutively active MAT cDNA contains a valine-to-glycine substitution in the highly conserved sequence PRCGVPDV, which corresponds to amino acids 88–95 near the carboxyl-terminal end of the prodomain. Mutations in the rat stromelysin-1 sequence in this same region leads to variants that have a significantly increased tendency to spontaneously generate active STR-1 (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 1988, Park et al., 1991). MAT protein produced by this construct therefore theoretically circumvents any dependence on exogenous factors for activation. The catalytically inactive MAT cDNA contains a glutamic acid-to-glutamine substitution at position 216 within the highly conserved zinc-binding domain. Similar mutations in the rat STR-1 cDNA result in protein that cannot be activated by organic mercurides to auto-proteolyze (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 1988). We reasoned that this construct would encode a MAT protein with three-dimensional structure that deviates only slightly from wild-type MAT but lacks proteolytic activity. This inactive mutant would provide a control to determine whether observable effects could be attributed to the catalytic activity of this metalloproteinase.

To determine whether the wild-type, active, and inactive human MAT transgenic constructs were functional in vitro, the human breast cancer cell line Hs578t was transfected with each MMTV-MAT expression vector, and the conditioned medium was analyzed for MAT protein by immunoprecipitation. Specific MAT immunoreactivity was not detected in the conditioned medium of untreated transfected cells, but was induced by the addition of the synthetic glucocorticoid Dex, a known inducer of the MMTV promoter/enhancer (Ringold, 1983; Figure 1C, compare lanes A and B, C and D, and E and F). The wild-type MAT cDNA produces a 28-kDa protein corresponding to the latent zymogen (Figure 1C, lane B). In the presence of the organic mercuride APMA, which activates the cysteine switch of MMPs (Birkedael-Hansen et al., 1993 for review), wild-type MAT protein was cleaved and converted to 19 kDa, consistent with the removal of the pro domain and conversion to the mature, active catalytic form (Figure 1C, compare lanes B to G). Immunoprecipitation of the constitutively active human MAT protein demonstrated that the majority of the protein in the medium of transfected cells was present in the 19-kDa active form, and the residual 28- kDa protein could be completely converted to the activated form with APMA treatment (Figure 1C, lanes D and H). These data indicate that the mutation in the pro domain of MAT results in constitutive activation of the enzyme in the absence of exogenous activators, as was predicted from the results of similar mutations in rat STR-1 (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 1988; Park et al., 1991). In contrast, the inactive mutant protein was produced as the higher molecular weight proenzyme form and was not converted to the mature form by APMA treatment, indicating that a mutation at amino acid 216 in human MAT prevents the enzyme from autoproteolytic cleavage and thus represents an inactivating mutation (Figure 1C, compare lanes F and I).

Generation of MAT-expressing Transgenic Mice

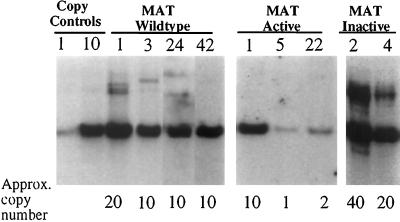

To test the effects of overexpressing the epithelium-specific matrix-degrading enzyme MAT in select reproductive tissues in vivo, the MMTV-MAT expression vectors producing wild-type, active, and inactive MAT protein were used to establish transgenic mouse lines by standard pronuclear injection techniques. Transgenic mice were identified by Southern blot analysis, and founder mice harboring the transgene were mated to establish transgenic lines (Figure 2). At least two lines per construct were established with varying copy numbers to control for insertional variation. The resulting transgenic lines were identified by the founder animal number and will be referred to hereafter as MMTV-MAT (MMTV-wild-type-matrilysin), MMTV-ActMAT (MMTV-active-matrilysin), and MMTV-InMAT (MMTV-inactive-matrilysin).

Figure 2.

MMTV-MAT transgenic lines. Southern hybridization of 10 μg of genomic DNA from MMTV-MAT founder animals (lines 1, 3, 24, and 42), MMTV-ActMAT founder animals (lines 1, 5, and 22), and MMTV-InMAT founder animals (lines 2 and 4). The approximate copy number of each line is indicated below the lane.

Expression and Localization of the MAT Transgene in Mammary Epithelial Cells

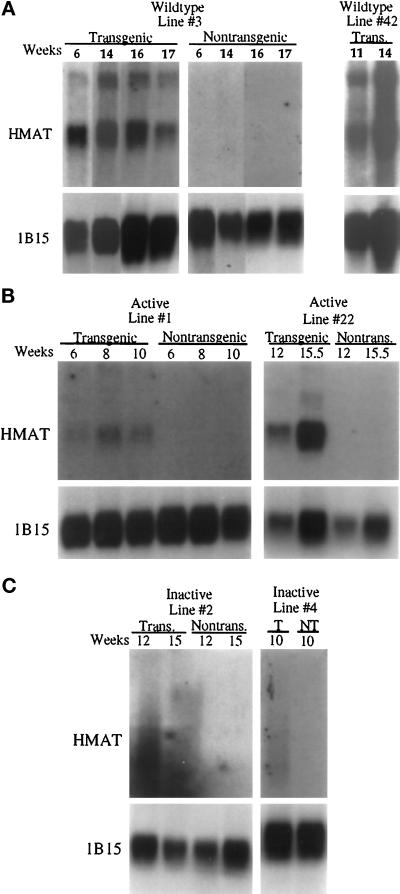

The MMTV-LTR promoter/enhancer has been used extensively to drive the expression of transgenes in the mammary epithelium (Cardiff and Muller, 1993 for review). The MMTV-LTR promoter activity responds to endogenous steroid hormone levels in the murine mammary glands during development, pregnancy, and lactation, as well as during the normal estrous cycle (Gunzburg and Salmons, 1992). MAT expression in the transgenic animals was analyzed by Northern blot analysis of poly(A+) RNA from developing mammary glands of female mice harboring the wild-type, active, and inactive human MAT constructs. We observed considerable variability in the expression of the MAT transgene within and between the various transgenic lines, presumably due to hormonal fluctuations. For example, approximately 42% (8/19) of transgenic mammary glands examined from MMTV-MAT line 3 expressed human MAT wild-type mRNA at various stages of mammary development. No correlation of human MAT mRNA expression could be made for a particular time during mammary development or during a specific day of the estrous cycle. However, when animals in which the MAT transgene was expressed were compared, human MAT expression appeared abundant between 6 and 17 wk of age in the MMTV-MAT lines 3 and 42 and was absent in nontransgenic littermate controls (Figure 3A and our unpublished results). MMTV-ActMAT lines 1 and 22 also displayed detectable levels of MAT mRNA during mammary gland development, although in general MAT mRNA levels appeared lower than for MMTV-MAT mice (Figure 3B). In contrast, MAT mRNA appeared as a smear instead of a distinct band when isolated from the mammary glands of both the MMTV-InMAT lines 2 and 4 animals (Figure 3C). Several attempts were made to extract intact human MAT RNA from the mammary glands of the MMTV-InMAT transgenic lines, all of which proved to be futile. Endogenous mouse MAT mRNA was not detectable by Northern blot analysis in the developing mammary glands of either nontransgenic or MMTV-MAT transgenic mice (our unpublished results). However, we have previously shown by reverse transcriptase-PCR that low levels of mouse MAT are expressed in the adult mammary gland (Wilson et al., 1995).

Figure 3.

Expression of the human MAT transgene in developing mammary tissue. Northern analysis of poly A+ selected RNA (4 μg) from nontransgenic and transgenic female mammary tissue at various weeks during mammary development. Blots were probed with a 1.1-kb 32P-labeled human MAT cDNA probe (HMAT), and a cyclophilin (1B15) cDNA probe was used to control for RNA loading. (A) Expression of MAT transgene is present at relatively high levels in selected samples from lines 3 and 42 and absent in the nontransgenic littermates. (B) Line 1 and line 22 express the MMTVActMAT transgene, while nontransgenic littermates do not express the transgene. (C) Isolation of intact human MAT mRNA from both MMTV-InMAT transgenic lines 2 and 4 was not possible after several attempts. Degraded human MAT mRNA as shown was consistently isolated in both lines of transgenic mammary glands.

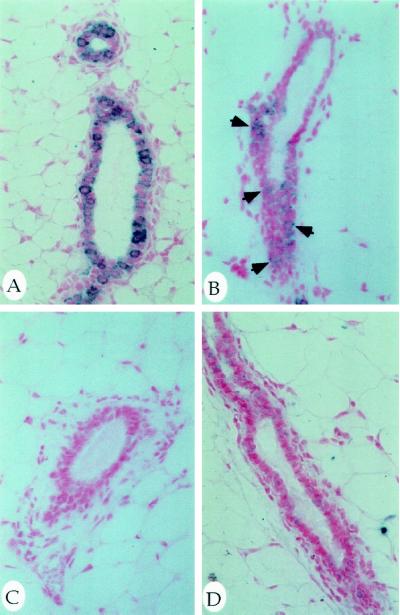

Immunohistochemistry was performed to localize the product of the MAT transgene in the mammary glands. Protein expression from the MMTV-MAT wild-type transgene was detected during several stages of mammary gland development (6–14 wk), with staining localized to the cytoplasm of the epithelial cells of the mammary ducts (Figure 4A and data not shown). MAT protein was also detected in mammary tissue from the MMTV-ActMAT lines, but at relatively lower levels than the MMTV-MAT wild-type lines (Figure 4B). We detected no MAT immunoreactivity in mammary glands from the MMTV-InMAT animals (Figure 4C), suggesting that the mutation impairs the production of MAT protein in vivo. No immunoreactivity was detected in any mammary gland sections from nontransgenic littermate controls at various times of mammary development (Figure 4D for example). Because of the absence or low expression of MAT protein in the transgenic animals carrying the mutated human MAT cDNA constructs and the high MAT expression in the transgenic animals carrying the wild-type human MAT cDNA construct, we focused our attention in subsequent studies on those animals carrying the wild-type MAT transgene. In general, initial observations suggest that transgenic animals carrying the activated form of MAT showed similar phenotypes to wild-type MAT transgenics but to a lesser degree, while the inactive MAT transgenics were indistinguishable from nontransgenic controls.

Figure 4.

Localization of human MAT protein by immunohistochemistry. Representative sections from developing transgenic (A, B, and C) and nontransgenic (D) mammary glands were probed with an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody against a human MAT peptide. Staining of human MAT is in the cytoplasm of the mammary ducts from MMTV-MAT line 3 (A) and to a lesser extent in MMTV-ActMAT line 22 (B) developing glands (arrows). No specific staining was detected in MMTV-InMAT line 2 transgenic (C) or nontransgenic (D) mammary glands. Photographs were taken using a 50× objective.

Consequences of MAT Overexpression in the Mammary Glands

Previous studies have indicated that the expression of the MMP STR-1 in mammary epithelial cells results in disruption of the basement membrane and subsequent changes in the proliferative and apoptotic indices of these cells, as well as premature lobuloalveolar development and milk protein production in virgin female mice (Sympson et al., 1994; Witty et al., 1995b). STR-1 is normally expressed during murine mammary gland development; however, its expression is confined to stromal cells surrounding the developing ducts (Witty et al., 1995b). We have shown that MAT is endogenously expressed, albeit at very low levels, in the adult murine mammary gland by reverse transcriptase-PCR (Wilson et al., 1995). Although we have been unable to localize endogenous MAT expression in this tissue by in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry, studies with human mammary glands demonstrate that MAT mRNA and protein are expressed in mammary epithelial cells (Saarialho-Kere et al., 1995; Heppner et al., 1996). Examination of other murine tissues also suggests that MAT is primarily expressed in glandular epithelial cells (Wilson et al., 1995). Therefore, we were interested in investigating the effects of overexpressing the epithelium-specific MMP MAT in the epithelial cells of developing murine mammary glands and comparing the effect to previous results with STR-1 overexpression.

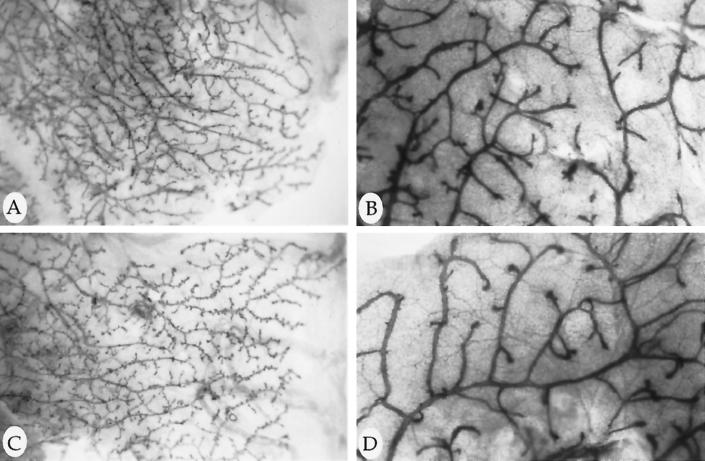

The ductal tree of developing mammary glands in nontransgenic and MMTV-MAT transgenic mice was examined by whole mount tissue preparation. During mammary gland development, which begins at approximately 5 wk of age and following the onset of estrogen production, the mammary end buds grow outward from the nipple to fill the entire fat pad with a highly branched network of epithelial cells (Snedeker et al., 1991 and references therein). There was no apparent morphological difference in the mammary ductal tree during development, pregnancy, lactation, or involution in MMTV-MAT (Figure 5A and B, and unpublished results) when compared with nontransgenic littermate controls (Figure 5C and D, and unpublished results). We also observed no difference in mammary gland morphology in the MMTV-ActMAT and MMTV-InMAT animals.

Figure 5.

Morphological appearance of developing mammary glands. Iron hematoxylin-stained whole mounts of inguinal mammary glands from MMTV-MAT line 3 transgenic (A and B) and nontransgenic (C and D) female virgin animals. Glands were removed at 14 wk (A and C), 16 wk (B), and 12 wk (D) of mammary gland development. Photographs were taken using a 2.5× (A and C) and 6.4× (B and D) objective.

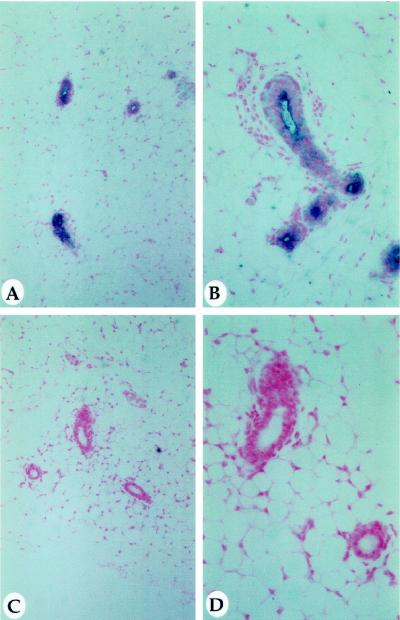

Although the MMTV-MAT glands display normal morphology, we examined them for subtle changes in differentiation, proliferation, or apoptosis that may have occurred in response to MMTV-MAT. Production of the milk proteins in the casein family is normally restricted to differentiated mammary epithelial cells during late pregnancy and lactation. However, using an antibody specific for mixed caseins, milk proteins were detected in all virgin MAT transgenic animals previously shown to express the MAT transgene by Northern analysis or MAT protein by immunohistochemistry (Figure 6A and B). No casein protein was detected in age-matched nontransgenic control mammary glands (Figure 6C and D). These results suggest that there is aberrant differentiation of mammary epithelial cells as a result of the transgene expression, although there are no accompanying morphological changes resembling lobuloalveolar development. The lack of morphological changes is consistent with our inability to detect differences in the number of proliferative or apoptotic cells in the MMTV-MAT mammary glands compared with age-matched, nontransgenic controls. We observed no significant difference in the number or location of proliferating cells as determined by immunoreactivity with the cell cycle marker proliferating cell nuclear antigen, or apoptotic cells as determined by the number of cells with excessive nuclear DNA fragmentation (TUNEL assay; unpublished results).

Figure 6.

Casein expression in virgin MMTV-MAT mammary glands. MMTV-MAT line 3 transgenic mammary glands (A and B) at 6 wk of age were positive for β-casein expression using immunohistochemistry, while nontransgenic control mammary glands (C and D) were negative. Panels A and C were taken using a 16× objective, and panels B and D were taken using a 32× objective.

Localization of MAT Transgene Expression in the Male Reproductive Tract

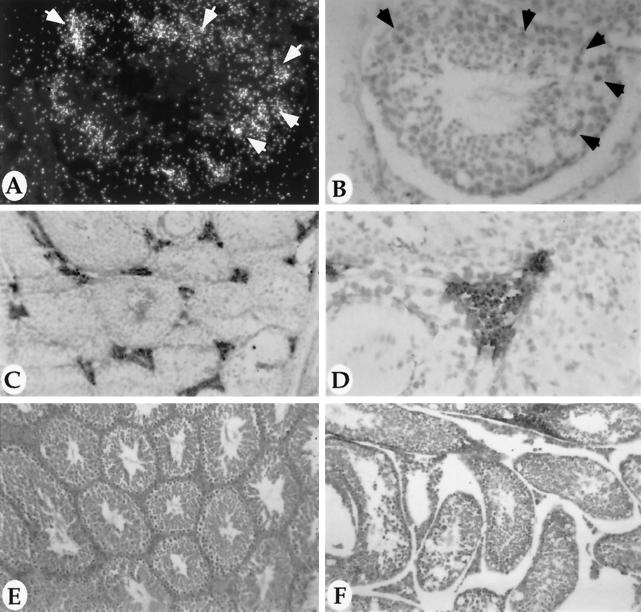

The MMTV-LTR targets expression of a reporter gene to the male reproductive tract (Choi et al., 1987; Ross et al., 1990). Several transgenic animals previously generated using this promoter have reported transgene expression in the testis and epididymis (Witty et al., 1995b: Matsui et al., 1990). In agreement with this, we found that the MAT transgene was expressed in both the testis and epididymis of MMTV-MAT transgenic mice. More specifically, the human MAT mRNA was localized by in situ hybridization to the primary spermatocytes of the transgenic testis (Figure 7A and B). In contrast, the human MAT protein localizes by immunohistochemistry on frozen sections of the testis to the interstitial space surrounding the seminiferous tubules (Figure 7C and D). In the transgenic epididymis, the human MAT protein was also localized by immunohistochemistry to the epithelial ducts of the initial segment of the epididymis (Figure 8, A and B). Endogenous murine MAT protein has been previously shown to be expressed in the epithelial cells lining the efferent ducts (Wilson et al., 1995). The antibody that we have utilized for these studies is specific for human MAT as shown by the inability of this antibody to detect endogenous mouse MAT protein in the efferent ducts (Figure 8, A and B, and unpublished results). In addition, the human MAT antibody detects the transgene product in the transgenic testis (Figure 7C and D) whereas the antibody specific for mouse MAT protein does not show specific staining in transgenic testis (unpublished results).

Figure 7.

Expression and consequence of human MAT in the testis. Sections from the testis of a young (4- to 6-mo-old) MMTV-MAT line 3 male were hybridized with an antisense 35S-labeled human MAT probe (A, dark-field and B, light-field; 40× objective). Hybridization was localized to the primary spermatocytes (arrows) in the testis (A and B). Frozen sections of the testis from a young (4- to 6-mo-old) MMTV-MAT line 3 transgenic male were probed with a polyclonal antibody specific to human MAT. MAT transgene product is localized to the interstitial space surrounding the seminiferous tubules as can be seen at low power (C; 12.5× objective) and at higher power (D, 50× objective). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of sections obtained from an aged (8- to 9-mo-old) normal (E) or MMTV-MAT line 3 transgenic (F) adult testis (both taken using a 12.5× objective).

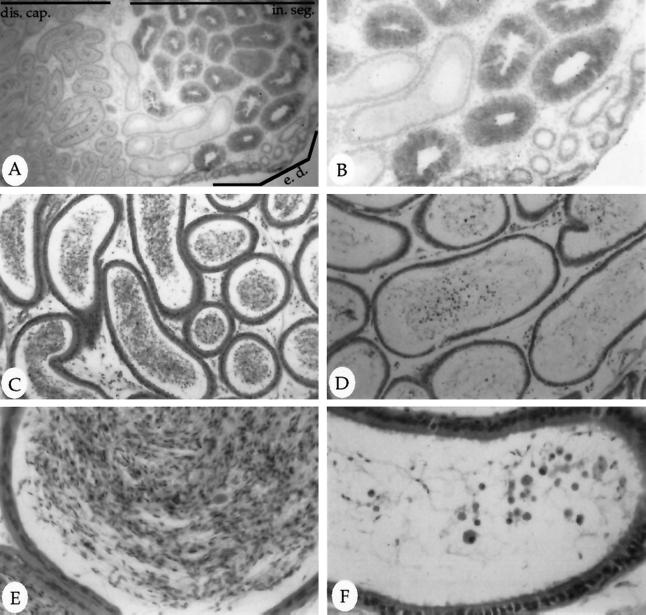

Figure 8.

Expression and consequence of human MAT in the epididymis. Frozen sections of the epididymis from a MMTV-MAT line 3 transgenic male were probed with a polyclonal antibody specific to human MAT. The protein is localized to the epithelial ducts of the uppermost region of the epididymis, the initial segment (in. seg.), as can be seen at low power (A; 6.25× objective; distal caput, dis. cap.; efferent ducts, e. d.) and high power (B; 12.5× objective). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of normal (C and E) or MMTV-MAT line 3 transgenic (D and F) adult corpus epididymis. Pictures taken using a 16× (C and D) and 50× (E and F) objective.

Consequences of MAT Overexpression in the Male Reproductive Tract

When breeding the MMTV-MAT male transgenics, we noted that one of the male founder animals was infertile. In addition, other male founders and their offspring also demonstrated reduced fertility, producing few litters with only one to three pups. These same male transgenic animals eventually became infertile at approximately 6 mo of age. We therefore analyzed several male transgenic gonads to address the cause of the observed reproductive defect. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of testis from 8-mo-old or older transgenic males show extreme disorganization of seminiferous tubule morphology (Figure 7F, for example) compared with an age-matched nontransgenic controls (Figure 7E). In addition, an absence or reduced number of mature spermatozoa is noted in the seminiferous tubules of transgenic testis (Figure 7F) compared with the abundant presence of spermatozoa in the lumen of nontransgenic testis (Figure 7E). Less severe morphological disruption was also observed in younger males. The MMTV-MAT transgenic epididymis demonstrated a lack of mature sperm production (Figure 8D), and the abnormal presence of sloughed undifferentiated germ cells was observed at higher magnification (Figure 8F), compared with age-matched nontransgenic controls (Figure 8, C and E). The morphology of the epididymis, and specifically the epithelial cells of the initial segment, appear normal (Figure 8), indicating that this is a local response and not a general effect on the male reproductive tract. Consistent with this observation, circulating androgen levels in aged transgenic male animals was not significantly different from age-matched nontransgenic controls (unpublished results). These histological data support our initial observations of decreased fertility in the MMTV-MAT male transgenic animals. To our knowledge, perturbation of male reproductive function by MMP expression has not been previously observed.

Expression of the MAT Transgene in Other Organs

The MMTV-LTR is known to be expressed in the epithelial cells of the salivary glands, lungs, kidneys, and lymphoid cells of the spleen and thymus in addition to the tissues discussed above (Ross et al., 1990). We detected human MAT mRNA in the adult brain, salivary glands, lung, spleen, and thymus of MMTV-MAT transgenic mice, while the female reproductive tract and liver contained no detectable human MAT RNA (unpublished results). Although these additional organs expressed MAT, there were no observable functional or morphological changes in these tissues as a result of transgene expression.

DISCUSSION

Our goal in this study was to generate transgenic animals that overexpress three separate forms of human MAT in the reproductive tissues. To this end, we first developed wild-type, active, and inactive human MAT constructs and examined the ability of these constructs to produce functional MAT protein in an in vitro system. We have shown that full-length wild-type human MAT cDNA under the control of the MMTV-LTR promoter/enhancer was capable of producing full-length pro-MAT that was efficiently converted to active MAT after exposure to an exogenous activator. A valine-to-glycine substitution in the highly conserved prodomain sequence PRCGVPDV of MAT encoded a protein with an increased tendency to spontaneously generate active protein, similar to that previously observed with STR-1 (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 1988; Park et al., 1991). In addition, a glutamic acid-to-glutamine substitution in the conserved zinc-binding sequence of MAT resulted in a catalytically inactive protein, as observed for STR-1 (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 1988; Park et al., 1991). Although we could detect MAT protein produced by these constructs in the conditioned medium of cultured breast carcinoma cells, mutations of the MAT cDNA significantly decreased the efficiency with which MAT protein was produced in the transgenic mammary gland in vivo. The relative mRNA and protein levels of MAT were reduced in animals expressing the active MAT construct, and we observed no intact mRNA and no immunostaining for MAT protein in animals containing the inactive MAT transgene. The effect of the inactivating mutation on mRNA stability is unusual, although nonsense mutations have been shown to result in increased mRNA decay in several different organisms (Kessler and Chasin, 1996 and references therein). It is presumed that this effect occurs in the cultured cells as well, but that sufficient mRNA is present to allow translation and accumulation of protein in the culture medium. A reduction in the efficiency of protein production was noted previously after mutation of similar sequences in the STR-1 protein (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 1988; Park et al., 1991). It was speculated that this was due to the presence of active enzyme in an intracellular compartment resulting in premature auto-degradation (Park et al., 1991), or possibly a conformational change that may have altered the secretory pathway of the mutant protein. Similar effects are likely to have occurred with the mutated MAT protein in vitro and in vivo, resulting in a reduction in protein levels. The absence of detectable inactive MAT protein in vivo may reflect a protein turnover system that is not operable in cultured cells or is reliant on other cell types.

The expression of wild-type MAT results in an altered phenotype in the mammary gland and male reproductive tract compared with nontransgenic controls. We assume this is the result of degradation of MAT substrates, although we were unable to definitively attribute the effect to MAT-induced proteolysis since the inactive MAT transgenic mice expressed no detectable MAT protein. However, since MAT is the “minimal domain MMP,” it is unlikely to possess biological activities other than proteolysis. Since phenotypic alterations were observed in the mammary gland and testis, wild-type MAT is apparently activated in the tissues. Similar endogenous activation of interstitial collagenase was assumed in transgenic mice expressing a human MMP-1 genomic fragment under the control of the haptoglobin promoter (D’Armiento et al., 1992). MMPs such as MAT are activated by the “cysteine switch” mechanism, in which the cysteine in the conserved PRCGVDV sequence in the pro domain becomes dissociated from the catalytic Zn, resulting in a conformation change and autoproteolysis of the pro domain (Van Wart and Birkedal-Hansen, 1990). The activation of latent MMPs is affected by a variety of natural molecules. For example, plasmin activates most MMPs by cleaving once in the pro domain, producing an unstable intermediate form of the enzyme, which then autoproteolyses to produce a fully active enzyme (Birkedal-Hansen et al., 1993 for review). Other enzymes, such as cathepsin G, neutrophil elastase, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and plasma kallikrein, have also been shown to activate latent MMPs by similar mechanisms (Eeckhout and Vaes, 1977; Grant et al.., 1987; Okada and Nakanishi, 1989; Nagase et al., 1990; Saari et al., 1990). In addition to proteases, oxygen radicals are also potential activators of MMPs due to their ability to disrupt the cysteine switch (Burkhardt et al., 1986; Rajagopalan et al., 1996). At this time, the endogenous activator of MAT is unidentified, but it is interesting that phenotypic alterations are observed in some, but not all, tissues that express the wild-type MAT transgene. A more thorough examination of tissues in the MMTV-ActMAT mice may provide insights as to whether the absence of phenotypic differences is due to the lack of an effect of MAT in these organs or the deficiency of an endogenous activator of latent MAT.

The Effect of MAT Overexpression on Mammary Gland Development

The developing murine mammary gland has provided an excellent model system to examine the role of MMPs in a remodeling tissue. The expression patterns of MMPs suggest that they play an important role in the dramatic morphological and functional changes that take place in the mammary gland during ductal development. STR-1 and GEL A in particular are expressed in the developing mouse mammary gland as well as during the involution process (Talhouk et al., 1992; Sympson et al., 1994; Witty et al., 1995b). MAT mRNA, in contrast, is expressed at low levels in the murine mammary gland (Wilson et al., 1995), but is found in abundant levels in human mammary epithelium from reduction mammoplasties (Saarialho-Kere et al., 1995; Heppner et al., 1996). Since the function of MAT in human mammary epithelium is unknown, recapitulation of MAT expression in the murine mammary gland provides a system in which to address this question.

Overexpression of human MAT protein had no effect on the general morphological development of the mammary ductal tree, but induced the ectopic expression of a pregnancy-associated protein, β-casein, in developing virgin transgenic mammary glands. In contrast, the MMTV-STR-1 (Witty et al., 1995b) and WAP-STR-1 (Sympson et al., 1994) transgenic animals express β-casein mRNA, but not protein, display the morphological features of precocious lobuloalveolar development, and demonstrate increased proliferation and apoptotic indices (Boudreau et al., 1995; Witty et al., 1995b). There are several potential explanations for these differences. Experimental variation, such as differences in the integration sites, expression levels, and genetic backgrounds of the mice, may be contributing factors, although the phenotypes were observed in several independent lines of mice in all cases. STR-1 contains a hemopexin/vitronectin-like domain that is absent in MAT, and may confer additional activities or alter substrate specificity in vivo resulting in the observed phenotypic differences. The abnormal tissue-type expression of STR-1 in glandular epithelial cells, as opposed to the normal expression in stromal fibroblast-like cells surrounding the developing ducts (Witty et al., 1995b), may also account for the more profound cellular alterations in these mice compared with MAT transgenic animals. In addition, the differential endogenous expression levels of STR-1 and MAT in the mammary gland suggest that these MMPs may have distinct roles during mammary development. The low endogenous expression levels of MAT (Wilson et al., 1995) implies that this particular MMP plays a minor role in mammary development compared with the abundantly expressed STR-1 (Witty et al., 1995b), which may explain the less dramatic consequences of MAT overexpression. Although the morphological features of lobuloalveolar development were not observed in the MMTV-MAT transgenic mice, they displayed features of lactational differentiation by the production of β-casein protein in virgin transgenic mammary glands. This implies that β-casein expression can be dissociated from the morphological changes and may be directly related to alterations in the integrity of the basement membrane of mammary epithelial cells.

MMTV-MAT Expression in Male Reproductive Tract Induces Infertility

An unexpected consequence of generating MAT transgenic animals under the control of the MMTV promoter/enhancer was the development of abnormalities of the male reproductive tract, since this phenotype was not observed in the MMTV-STR-1 mice (Witty et al., 1995b). In the testis, spermatozoa normally develop within the seminiferous tubules in close association with the Sertoli cells, while androgens are synthesized between the tubules in the Leydig cells (reviewed in Johnson and Everitt, 1995). These two compartments are separated by structural and physiological barriers that develop during puberty before the initiation of spermatogenesis. The barriers consist of gap and tight junctional complexes that completely encircle each Sertoli cell, linking it to the next adjacent cell. A few molecules may traverse these junctional complexes and penetrate into the basal compartment of the tubules from the surrounding interstitium, usually as the result of selective transport. Ions and proteins not only flow from the Leydig cells into the tubules, but proteins such as androgen-binding protein, testicular transferrin, and sulfated glycoproteins 1 and 2 move from the intratubular compartment out into the interstitial area surrounding the tubules (Griswold, 1988; Gunsalus and Bardin, 1991). Similar to these proteins, the mRNA and protein localization patterns of the MAT transgene suggest that MAT protein is produced by the germ cells of the seminiferous tubules and selectively transported into the interstitial space surrounding the Leydig cells. The functional consequence of this is to disrupt sperm production, as evidenced by the absence of mature spermatozoa in the epididymis of these transgenic male animals. This is presumably due to the degradation of the cellular barriers between the interstitium and seminiferous tubules and subsequent loss of tissue architecture. The decrease in sperm production is not a direct result of a loss of Leydig cell function, as demonstrated by the maintenance of normal testosterone levels in transgenic animals. The degradative effects of MAT seem to be gradual, suggesting that a threshold of excess enzyme needs to be reached before damaging effects occur, or that the destructive effects are cumulative. The absence of mature spermatozoa in the transgenic epididymis could also be caused by the overexpression of MAT in the initial segment of the epididymis. Overexpression of the MAT transgene in the epididymis may have specific effects on sperm maturation by disrupting the spatial or temporal cleavage of specific substrates or may have more nonspecific effects caused by excessive degradation of proteins in these organs.

High levels of endogenous MAT expression have been localized to the efferent ducts while low levels of endogenous MAT hybridization were also observed in the proximal area of the initial segment of the epididymis and in the cauda, where mature fully differentiated sperm accumulate in the lumen (Wilson et al., 1995). Very little is known about the endogenous expression of other metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in the male reproductive tract. GEL A is expressed by cultured rat Sertoli cells (Sang et al., 1990a,b), and TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 have been detected in the Sertoli cells of maturing rats (Ulisse et al., 1994). In addition, precursor regions in the α- and β-subunits of the fertilin complex or PH-30, a sperm surface protein that has been implicated in sperm–egg fusion, contain metalloproteinase domains that align with those found in snake venom proteins (Wolfsberg et al., 1993). The function of MAT and other MMPs in the male reproductive system is not known. However, the specific tissue expression pattern of endogenous MAT is suggestive of a role in sperm maturation, possibly by proteolytically processing sperm antigens. MAT-deficient and STR-1-deficient mice display no obvious defects in male fertility (Wilson et al., 1997 and our unpublished observations). In earlier studies we have observed up-regulation of STR-1 and STR-2 in the involuting uterus of MAT-deficient mice, and a similar apparent compensatory mechanism in STR-1-deficient mice (Rudolph-Owen et al., 1997). These data suggest that there is strong selective pressure for MMP activity in reproductive processes, which we speculate may also include the male reproductive tract.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jane Wright and the Vanderbilt Transgenic Core for production of the transgenic animals, Melody Henderson for assistance with animal husbandry, Ginger Winfrey for furnishing frozen sections, Drs. Howard Crawford and Kathleen Heppner for the generation of the human MAT PCR fragment and subsequent plasmid, Dr. Gary Olson for help with identifying histological structures, and Dr. Loren Hoffman for informative conversations and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Department of Defense (DAMD 17–94-J-4226 to L.M.M, and predoctoral fellowship DAMD 17–94-J-4228 to L.A.R-O.) and the National Institutes of Health (Vanderbilt Cancer Center support grant P30-CA68485 and Reproductive Biology Center grant P30-HD-05797).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: MAT, matrilysin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MMTV-LTR, murine mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat.

REFERENCES

- Birkedal-Hansen H, Moore WGI, Bodden MK, Windsor LJ, Birkedal-Hansen B, DeCarlo A, Engler JA. Matrix metalloproteinases: a review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau N, Sympson CJ, Werb A, Bissell MJ. Suppression of ICE and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells by extracellular matrix. Science. 1995;267:891–893. doi: 10.1126/science.7531366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannstrom M, Woessner JF, Jr, Koos RD, Sear CH, LeMaire WJ. Inhibitors of mammalian tissue collagenase and metalloproteinase suppress ovulation in the perfused rat ovary. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1715–1721. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-5-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breathnach R, Harris BA. Plasmids for the cloning and expression of full-length double-stranded cDNAs under control of the SV40 early or late gene promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:7119–7136. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.20.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt H, Hartmann F, Schwingel MF. Activation of latent collagenase from polymorphonuclear leukocytes by oxygen radicals. Enzyme. 1986;36:221–231. doi: 10.1159/000469298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler TA, Zhu C, Mueller RA, Fuller GC, Lemaire WJ, Woessner JF., Jr Inhibition of ovulation in the perfused rat ovary by the synthetic collagenase inhibitor SC 44463. Biol Reprod. 1991;44:1183–1188. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.6.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Transgenic mouse models of mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Surv. 1993;16:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Henrard D, Lee I, Ross SR. The mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat directs expression in epithelial and lymphoid cells of different tissues in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1987;61:3013–3019. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3013-3019.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossins J, Dudgeon TJ, Catlin G, Gearing AJ, Clements JM. Identification of MMP-18, a putative novel human matrix metalloproteinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:494–498. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson P, Forss-Petter S, Brow M, Calavetta L, Douglass J, Milner R, Sutcliffe J. p1B15: A clone of the rat mRNA encoding cyclophilin. DNA. 1988;7:261–267. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Armiento J, Dalal SS, Okada Y, Berg RA, Chada K. Collagenase expression in the lungs of transgenic mice causes pulmonary emphysema. Cell. 1992;71:955–961. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90391-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhout Y, Vaes G. Further studies on the activation of procollagenase, the latent precursor of bone collagenase: Effects of lysosomal cathepsin B, plasmin and kallikrein, and spontaneous activation. Biochem J. 1977;166:21–29. doi: 10.1042/bj1660021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant GA, Eisen AZ, Marmer BL, Roswit WT, Goldberg GI. The activation of human skin fibroblast procollagenase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5886–5889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold MD. Protein secretions of Sertoli cells. Int Rev Cytol. 1988;110:133–156. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunsalus GL, Bardin CW. Sertoli-germ cell interactions as determinants of bidirectional secretion of androgen-binding protein. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;637:322–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb27319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzburg WH, Salmons B. Factors controlling the expression of mouse mammary tumour virus. Biochem J. 1992;283:625–632. doi: 10.1042/bj2830625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner KJ, Matrisian LM, Jensen RA, Rodgers WH. Expression of most matrix metalloproteinase family members in breast cancer represents a tumor-induced host response. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:273–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B, Beddington R, Costantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo, A Laboratory Manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. Production of transgenic mice; pp. 217–253. [Google Scholar]

- Hulboy DL, Rudolph LA, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloprotienases as mediators of reproductive function. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:27–45. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Kusakabe M, Sakakura T, Nakanishi I, Okada Y. Susceptibility of tenascin to degradation by matrix metalloproteinases and serine proteinases. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:216–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Yokohama Y, Nakanishi I, Ohuchi E, Fujii Y, Nakai N, Okada Y. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 (matrilysin) from human rectal carcinoma cells. Activation of the precursor, interaction with other matrix metalloproteinases and enzymic properties. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6691–6697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, Everitt BJ. Essential Reproduction. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell Science, Ltd.; 1995. Testicular function; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler O, Chasin LA. Effects of nonsense mutation on nuclear and cytoplasmic adenine phosphoribosyltransferase RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4426–4435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wu H, Byrne M, Jeffrey J, Krane S, Jaenisch R. A targeted mutation at the known collagenase cleavage site in mouse type I collagen impairs tissue remodeling. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:227–237. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbaix E, Kokorine I, Moulin P, Donnez J, Eeckhout Y, Courtoy PJ. Menstrual breakdown of human endometrium can be mimicked in vitro and is selectively and reversibly blocked by inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9120–9125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Halter SA, Holt JT, Hogan BLM, Coffey RJ. Development of mammary hyperplasia and neoplasia in MMTV-TGFα transgenic mice. Cell. 1990;61:1147–1155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90077-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell S, Navre M, Coffey RJ, Matrisian LM. Expression and localization of the matrix metalloproteinase pump-1 (MMP-7) in human gastric and colon carcinomas. Mol Carcinog. 1991;4:527–533. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940040617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina D. Methods in Cancer Research. H. Busch, New York: Academic Press; 1973. Preneoplastic lesions in mouse mammary tumorigenesis; pp. 3–53. [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Quantin B, Gesnel M, Millon-Collard R, Abecassis J, Breathnach R. The collagenase gene family in humans consists of at least four members. Biochem J. 1988;253:187–192. doi: 10.1042/bj2530187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Cockett MI, Ward RV, Docherty AJP. Matrix metalloproteinase degradation of elastin, type IV collagen, and proteoglycan: A quantitative comparison of the activities of 95 kDa and 72 kDa gelatinases, stromelysins-1 and -2 and punctuated metalloproteinase (PUMP) Biochem J. 1991;277:277–279. doi: 10.1042/bj2770277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Enghild JJ, Salvesen G. Stepwise activation mechanisms of the proecursor of matrix metalloproteinase-3 (stromelysin) by proteinases and (4-aminophenyl) mercuric acetate. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5783–5789. doi: 10.1021/bi00476a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Nakanishi I. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase 3 (stromelysin) and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (“gelatinase”) by human neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. FEBS Lett. 1989;249:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80657-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park AJ, Matrisian LM, Kells AF, Pearson R, Yuan Z, Navre M. Mutational analysis of the transin (rat stromelysin) autoinhibitor region demonstrates a role for residues surrounding the “cysteine switch”. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1584–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell WC, Matrisian LM. Complex roles of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor progression. In: Gunthert U, Birchmeier W, editors. Attempts to Understand Metastasis Formation I: Metastasis-Related Molecules. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Puente XS, Pendas AM, Llano E, Velasco G, Lopez-Otin C. Molecular cloning of a novel membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase from human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:944–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan S, Meng XP, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG, Galis ZS. Reactive oxygen species produced by macrophage-derived foam cells regulate the activity of vascular matrix metalloproteinases in vitro. Implications for atherosclerotic plaque stability. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2572–2579. doi: 10.1172/JCI119076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringold GM. Regulation of mouse mammary tumor virus gene expression by glucocorticoid hormones. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1983;106:79–103. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-69357-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SD, Roberts AB, Daniel CW. TGF-beta supresses casein synthesis in mouse mammary explants and may play a role in controlling milk levels during pregnancy. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:245–251. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SR, Hsu CLL, Choi Y, Mok E, Dudley JP. Negative regulation in correct tissue-specific expression of mouse mammary tumor virus in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5822–5829. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph-Owen LA, Hulboy DL, Wilson CL, Mudgett J, Matrisian LM. Coordinate expression of matrix metalloproteinase family members in the uterus of normal, matrilysin-deficient, and stromelysin-1-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4902–4911. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari H, Suomalainen K, Lindy O, Konttinen YT, Sorsa T. Activation of latent human neutrophil collagenase by reactive oxygen species and serine proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;171:979–987. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90780-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarialho-Kere UK, Crouch EC, Parks WC. The matrix metalloproteinase matrilysin is constitutively expressed in adult human exocrine epithelium. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:190–196. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12317104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Lopez R, Nicholson R, Gesnel M-C, Matrisian LM, Breathnach R. Structure-function relationships in the collagenase family member transin. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11892–11899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q-X, Dym M, Byers SW. Secreted metalloprotienases in testicular cell culture. Biol Reprod. 1990a;43:946–955. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q-X, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Liotta LA, Byers SW. Identification of type IV collagenase in rat testicular cell culture: Influence of peritubular-Sertoli cell interactions. Biol Reprod. 1990b;43:956–964. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sires UI, Griffin GL, Broekelmann TJ, Mecham RP, Murphy G, Chung AE, Welgus HG, Senior RM. Degradation of entactin by matrix metalloproteinases. Susceptibility to matrilysin and identification of cleavage sites. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2069–2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri A, Knauper V, Veirana N, Caocci F, Murphy G, Zaradi L. Different susceptibility of small and large human tenascin-c isoforms to degradation by matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8650–8654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedeker SM, Brown CF, DiAugustine RP. Expression and functional properties of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor during mouse mammary gland ductal morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:276–280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sympson CJ, Talhouk RS, Alexander CM, Chin JR, Clift SM, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Targeted expression of stromelysin-1 in mammary gland provides evidence for a role of proteinases in branching morphogenesis and the requirement for an intact basement membrane for tissue-specific gene expression. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:681–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talhouk RS, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Coordinated expression of extracellular matrix-degrading proteinases and their inhibitors regulates mammary epithelial function during involution. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:1271–1282. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.5.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulisse S, Farina AR, Piersanti D, Tiberio A, Cappabianca L, D’Orazi G, Jannini EA, Malykh O, Stetler-Stevenson WG, D’Armiento M, Gulino A, Mackay AR. Follicle-stimulating hormone increases the expression of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 and induces TIMP-1 AP-1 site binding complex(es) in prepubertal rat Sertoli cells. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2479–2487. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wart HE, Birkedal-Hansen H. The cysteine switch: A principle of regulation of metalloproteinase activity with potential applicability to the entire matrix metalloproteinase gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5578–5582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waseem NH, Lane DP. Monoclonal antibody analysis of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Structural conservation and the detection of a nucleolar form. J Cell Sci. 1990;96:121–129. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CL, Heppner KJ, Rudolph LA, Matrisian LM. The metalloproteinase matrilysin is preferentially expressed by epithelial cells in a tissue-restricted pattern in the mouse. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:851–869. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.7.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CL, Matrisian LM. Matrilysin: An epithelial matrix metalloproteinase with potentially novel functions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;28:123–136. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(95)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CL, Heppner KJ, Labosky PA, Hogan BLM, Matrisian LM. Intestinal tumorigenesis is suppressed in mice lacking the metalloproteinase matrilysin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;64:1402–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witty JP, Lempka T, Coffey RJ, Jr, Matrisian LM. Decreased tumor formation in 7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene-treated stromelysin-1 transgenic mice is associated with alterations in mammary epithelial cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1995a;55:1401–1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witty JP, McDonnell S, Newell KJ, Cannon P, Navre M, Tressler RJ, Matrisian LM. Modulation of matrilysin levels in colon carcinoma cell lines affects tumorigenicity in vivo. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4805–4812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witty JP, Wright J, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases are expressed during ductal and alveolar mammary morphogenesis, and misregulation of stromelysin-1 in transgenic mice induces unscheduled alveolar development. Mol Biol Cell. 1995b;6:1287–1303. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.10.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsberg TG, Bazan JF, Blobel CP, Myles DG, Primakoff P, White JM. The precursor region of a protein active in sperm-egg fusion contains a metalloproteinase and a disintegrin domain: structural, functional, and evolutionary implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10783–10787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]