Abstract

Substrates of a ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system called the N-end rule pathway include proteins with destabilizing N-terminal residues. N-recognins, the pathway's ubiquitin ligases, contain three substrate-binding sites. The type-1 site is specific for basic N-terminal residues (Arg, Lys, and His). The type-2 site is specific for bulky hydrophobic N-terminal residues (Trp, Phe, Tyr, Leu, and Ile). We show here that the type-1/2 sites of UBR1, the sole N-recognin of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, are located in the first ∼700 residues of the 1,950-residue UBR1. These sites are distinct in that they can be selectively inactivated by mutations, identified through a genetic screen. Mutations inactivating the type-1 site are in the previously delineated ∼70-residue UBR motif characteristic of N-recognins. Fluorescence polarization and surface plasmon resonance were used to determine that UBR1 binds, with a Kd of ∼1 μm, to either type-1 or type-2 destabilizing N-terminal residues of reporter peptides but does not bind to a stabilizing N-terminal residue such as Gly. A third substrate-binding site of UBR1 targets an internal degron of CUP9, a transcriptional repressor of peptide import. We show that the previously demonstrated in vivo dependence of CUP9 ubiquitylation on the binding of cognate dipeptides to the type-1/2 sites of UBR1 can be reconstituted in a completely defined in vitro system. We also found that purified UBR1 and CUP9 interact nonspecifically and that specific binding (which involves, in particular, the binding by cognate dipeptides to the UBR1 type-1/2 sites) can be restored either by a chaperone such as EF1A or through macromolecular crowding.

The N-end rule relates the in vivo half-life of a protein to the identity of its N-terminal residue. The ubiquitin (Ub)3-dependent N-end rule pathway recognizes several kinds of degradation signals (degrons), including a set called N-degrons (Fig. 1A) (1-9). Although prokaryotes lack the Ub system, they still contain the N-end rule pathway, albeit Ub-independent versions of it (10-18). In eukaryotes, an N-degron consists of three determinants: a destabilizing N-terminal residue of a protein substrate, one (or more) of its internal Lys residues (the site of formation of a poly-Ub chain), and a conformationally flexible region in a vicinity of this residue (1, 19-23). The N-end rule has a hierarchic structure (Fig. 1A). In eukaryotes, N-terminal Asn and Gln are tertiary destabilizing residues in that they function through their enzymatic deamidation, to yield the secondary destabilizing N-terminal residues Asp and Glu (24, 25). The destabilizing activity of N-terminal Asp and Glu requires their conjugation to Arg, one of the primary destabilizing residues, by Arg-tRNA-protein transferase (arginyl-transferase or R-transferase) (5-7, 26, 27). In mammals and other eukaryotes that produce nitric oxide (NO), the set of arginylated residues contains not only Asp and Glu but also N-terminal Cys (28), which is arginylated after its oxidation to Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate (27). The in vivo oxidation of N-terminal Cys requires NO, as well as oxygen (O2) or its derivatives (Fig. 1A) (6, 7, 29). The N-end rule pathway is thus a sensor of NO, through the ability of this pathway to destroy proteins with N-terminal Cys, at rates controlled by NO, O2, and their derivatives.

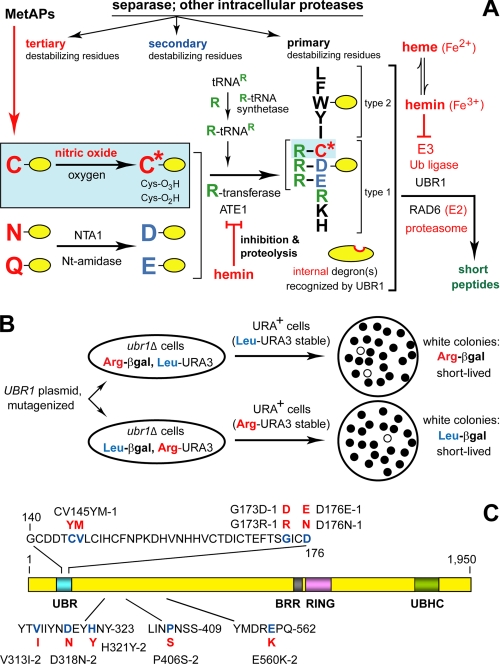

FIGURE 1.

The N-end rule pathway in the yeast S. cerevisiae. A, S. cerevisiae N-end rule pathway. N-terminal residues are indicated by single-letter abbreviations for amino acids. Yellow ovals denote the rest of a protein substrate. Hemin (Fe3+-heme) has been found to inhibit the arginylation activity of both the S. cerevisiae and mouse ATE1-encoded Arg-tRNA-protein transferase (R-transferase) (4). At least in mammalian cells, hemin also induces the proteasome-dependent degradation of R-transferase (4). MetAPs, methionine aminopeptidases. Separase refers to the ESP1-encoded protease that cleaves, in particular, the SCC1 subunit of cohesin and thereby allows mitosis (86). The resulting C-terminal fragment of SCC1 bears a destabilizing N-terminal residue (Arg in S. cerevisiae) and is degraded by the N-end rule pathway, a step that is essential for high fidelity of chromosome segregation (43). The reactions in a shaded rectangle are a part of the N-end rule pathway that is active in eukaryotes (e.g. vertebrates) that produce nitric oxide (NO) (6), but is also relevant to organisms such as S. cerevisiae, which lack NO synthases but can produce NO by other routes, and in addition can be influenced by NO from extracellular sources. C* denotes oxidized Cys, either Cys-sulfinate or Cys-sulfonate, produced in reactions mediated by nitric oxide, oxygen, and their derivatives. Oxidized N-terminal Cys is arginylated by ATE1-encoded isoforms of R-transferase (6, 7). Type-1 and type-2 primary destabilizing N-terminal residues (see Introduction) are recognized by UBR1, the sole N-recognin of S. cerevisiae that functions as a holoenzyme containing UBR1 and the E2 enzyme RAD6. Through its third substrate-binding site, UBR1 recognizes internal (non-N-terminal) degrons in substrates (denoted by a larger oval) such as CUP9, a transcriptional repressor of regulon that includes the PTR2 peptide transporter (8, 39, 40). The addition of hemin to S. cerevisiae UBR1 in vitro (in cell extracts) was found to inhibit the interaction of UBR1 (through its third substrate-binding site) with CUP9 (4). This inhibition was selective in that hemin did not interfere with the binding of primary destabilizing N-terminal residues of peptide reporters to the type-1 or type-2 binding sites of UBR1 (4). B, design of a genetic screen to isolate UBR1 mutants with selectively inactivated type-1 or type-2 substrate-binding sites. C, locations of mutations in S. cerevisiae UBR1 that were found to selectively inactivate either the type-1 site or the type-2 site. The mutant residues are in red. For the names of specific UBR1 domains, see Refs. 9, 29, 32 and the main text.

E3 Ub ligases of the N-end rule pathway, called N-recognins (1, 8, 29-37), recognize (bind to) primary destabilizing N-terminal residues, including Arg (Fig. 1A). (The term “Ub ligase” denotes either an E2-E3 holoenzyme or its E3 component.) At least four N-recognins, including UBR1, mediate the N-end rule pathway in mammals (30-33, 36). The known N-recognins share an ∼70-residue motif called the UBR box. Mouse UBR1 and UBR2 are sequelogous (similar in sequence) 200-kDa RING-type E3 Ub ligases that are 47% identical. Several other UBR-containing N-recognins, either confirmed or putative ones, are HECT-type or SCF-type E3 Ub ligases that share the UBR motif with the RING-type UBR1/UBR2 but are largely nonsequelogous to them otherwise (29-33). (A note on terminology: “sequelog” and “spalog” denote, respectively, a sequence that is similar, to a specified extent, to another sequence, and a three-dimensional structure that is similar, to a specified extent, to another three-dimensional structure (38). Besides their usefulness as separate terms for sequence and spatial similarities, the rigor-conferring advantage of sequelog and spalog is their evolutionary neutrality, in contrast to interpretation-laden terms such as “homolog,” “ortholog,” and “para-log.” The latter terms are compatible with the sequelog/spalog terminology and can be used to convey understanding about functions and common descent, if this (additional) information is available (38).)

The N-end rule pathway of S. cerevisiae is mediated by a single N-recognin, UBR1, a 225-kDa sequelog of mammalian UBR1 and UBR2 (Fig. 1, A and C) (8, 9). Saccharomyces cerevisiae UBR1 (Fig. 1C) contains at least three substrate-binding sites. The type-1 site is specific for basic N-terminal residues of protein substrates (Arg, Lys, and His), whereas the type-2 site is specific for bulky hydrophobic N-terminal residues (Trp, Phe, Tyr, Leu, and Ile). The third binding site of UBR1 targets proteins through their internal (non-N-terminal) degron, and is allosterically “activated” through a conformational change that is caused by the binding of short peptides to the two other binding sites of UBR1, type-1 and type-2. The known substrate of the third binding site of UBR1 is CUP9 (8, 39, 40), a transcriptional repressor whose regulon includes PTR2 (41), a gene encoding transporter of di- and tripeptides. The reversal of UBR1 autoinhibition by imported peptides accelerates the UBR1-dependent ubiquitylation of CUP9, leads to its faster degradation, and thereby causes a derepression of PTR2. The resulting positive feedback circuit allows S. cerevisiae to detect the presence of extracellular peptides and to react by increasing their uptake (8, 40). ClpS, a 12-kDa prokaryotic N-recognin, is an “adaptor” protein that mediates the (Ub-independent) targeting of N-end rule substrates in bacteria (13-15). ClpS recognizes type-2 (bulky hydrophobic) N-terminal residues and contains a region of sequelogy to the 225-kDa yeast UBR1, near its UBR box (2, 13, 42). This similarity and other common features of eukaryotic and prokaryotic N-end rule pathways (1, 2, 29) suggest that at least some N-degrons, N-recognins, and relevant “down-stream” proteases had evolved before the split between eukaryotes and prokaryotes.

The functions of the N-end rule pathway include: (i) the sensing of heme, through inhibition of the ATE1 R-transferase, in both yeast and mammals, by hemin (Fe3+-heme), which also inhibits N-recognins, the latter at least in yeast (4) (Fig. 1A); (ii) the sensing of NO and oxygen and the resulting control of signaling by transmembrane receptors through the conditional, NO/O2-mediated degradation of G-protein regulators RGS4, RGS5, and RGS16 (6, 7); (iii) regulation of import of short peptides through the degradation, modulated by peptides, of CUP9, the repressor of import (8, 40); (iv) fidelity of chromosome segregation through degradation of a separase-produced cohesin fragment (43); (v) regulation of apoptosis through degradation of a caspase-processed inhibitor of apoptosis (44, 45); (vi) a multitude of processes mediated by the transcription factor c-FOS, a conditional substrate of the N-end rule pathway (46); (vii) regulation of the human immunodeficiency virus replication cycle through degradation of human immunodeficiency virus integrase (47); and (viii) regulation of meiosis, spermatogenesis, neurogenesis, and cardiovascular development in mammals (6, 7, 27, 31, 33) and leaf senescence in plants (48). Mutations in human UBR1 (Fig. 1A) (29, 32, 33) are the cause of Johansson-Blizzard syndrome, which includes mental retardation, physical malformations, and severe pancreatitis (49). The abnormalities of UBR1-/- mice (30) include pancreatic insufficiency (49), a less severe counterpart of this defect in human Johansson-Blizzard syndrome (UBR1-/-) patients.

In this study, we used a genetic screen to probe the type-1 and type-2 substrate-binding sites of S. cerevisiae UBR1. This analysis demonstrated a modular organization of these sites, which could be selectively inactivated by specific mutations. We also characterized physical interactions between UBR1 and CUP9 that involve the internal (non-N-terminal) degron of CUP9, and we employed a completely defined in vitro system to probe the conditional (modulated by dipeptides) polyubiquitylation of CUP9 by the UBR1-RAD6 Ub ligase. In addition, we used both fluorescence polarization (FP) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to determine the affinities of purified UBR1 for specific N-terminal residues of model peptides. The results indicated, among other things, that at least the bulk of the observed in vivo specificity of UBR1 for N-end rule substrates (1, 2, 29) (Fig. 1, A and C) stems from differences in the physical affinity of UBR1 for destabilizing versus stabilizing N-terminal residues in the N-end rule.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains, Media, and Genetic Techniques—Synthetic yeast media (50) contained 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (Difco) and either 2% glucose (SD medium) or 2% galactose (SG medium). Synthetic media lacking appropriate nutrients were used to select for (and maintain) specific plasmids. Cells were also grown in rich medium (YPD) (51). The S. cerevisiae strains were YPH500 (MATα ura3-52 lys2-801 ade2-101 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ63 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1), JD52 (MATa trp1-Δ63 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 lys2-801), JD55 (MATa ubr1Δ::HIS3 trp1-Δ63 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 lys2-801) (52), SC295 (MATa GAL4 GAL80 ura3-52, leu2-3, 112 reg1-501 gal1 pep4-3) (8), and PJ69-4A (MATa trp1-901 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ GAL2-ADE2 LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 met2::GAL7-lacZ). The medium for dipeptide import assays was methionine-lacking SD containing allantoin (1 mg/ml) and the toxic dipeptide l-leucyl-l-ethionine (Leu-Eth; 37 μm) (39). To induce the PCUP1 promoter, CuSO4 was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mm (52). The XGal colony overlay assay was performed using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (XGal) at 0.1 mg/ml, as described (53). Transformation of S. cerevisiae was carried out using the lithium acetate method (50).

Reporter Plasmids—Five sets of reporter plasmids were used. Details of their construction are available upon request. pUB23-X high copy plasmids expressed Ub-X-eK-β-galactosidase fusions (denoted below as Ub-X-βgal) from the galactose-inducible PGAL1 promoter (19, 54). pBAX plasmids expressed Ub-X-eK-ha-URA3 fusions (X = Arg or Leu), denoted below as Ub-X-URA3. The largely cotranslational deubiquitylation of these Ub fusions (55) yielded the corresponding X-βgal and X-URA3 reporter proteins. pBAX plasmids were constructed from pBAM, a pRS314-based low copy plasmid expressing Ub-Met-eK-ha-URA3 (tagged with the ha epitope (50)) from the PCUP1 promoter (56). The term eK (extension (e) bearing lysines (K)) denotes an ∼40-residue, Escherichia coli Lac repressor-derived sequence (21, 54, 56). pDSRULB was constructed by subcloning the 5.4-kb ScaI fragment from pUB23-L (encoding Ub-Leu-βgal) into the SmaI site of pBAR, encoding Ub-Arg-URA3. The resulting low copy TRP1-marked pRS314 plasmid expressed Ub-Arg-URA3 from the PCUP1 promoter and Ub-Leu-βgal from the PGAL1 promoter. The similarly constructed pDSLURB expressed Ub-Leu-URA3 and Ub-Argβgal. The UPR (Ub/protein/reference) plasmids (21, 40, 57) for expression in S. cerevisiae, termed pBAXUPR, were based on the low copy pRS314 vector (58) and were constructed using PCR. A pBAXUPR plasmid expressed DHFRha-UbR48-X-eK-ha-URA3 (denoted below as DHFR-Ub-X-URA3) from the PCUP1 promoter (where X = Met, Arg, Leu, Glu, Lys, His, Ile, Phe, Tyr, or Trp). The analogous UPR-based plasmids, termed pXβgalUPR, expressed DHFRha-UbR48-X-eK-βgal (X = Met, Arg, or Leu), denoted as DHFR-Ub-X-βgal. pXβgalUPR were constructed by cutting an appropriate pBAXUPR plasmid with BamHI and SmaI, recovering the vector-containing fragment, and ligating it to the 3.8-kb βgal-encoding fragment produced from pUB23-M using BamHI and ScaI.

UBR1 Plasmids—S. cerevisiae UBR1 plasmids encoding wild-type or mutated UBR1 included pRBUBR1, pRB208, pFLAGUBR1SBX, pFLAGNT1UBR1, pUBR1NT1140FLAG, p209NTUBR1FLAG, p454NTUBR1FLAG, p710NTUBR1FLAG, p866NTUBR1FLAG, and p1002NTUBR1FLAG. Details of construction are available upon request. UBR1 alleles were expressed from the PADH1 promoter of the high copy LEU2-marked YEplac181 vector (59) in SC295, a protease-deficient S. cerevisiae strain. UBR1 and its derivatives that were encoded by the above plasmids carried either the ha epitope (pRBUBR1 and pRB208) or the FLAG epitope. pRB208 and pRBUBR1 (a derivative of pRB208) encoded full-length, C-terminally ha-tagged S. cerevisiae UBR1 (UBR1ha). pFLAGUBR1SBX encoded fUBR1, the N-terminally FLAG-tagged full-length UBR1. pFLAGNT1UBR1 encoded fUBR11-717, the N-terminally FLAG-tagged C-terminally truncated variant of UBR1. The design and expression of fUBR1 and fUBR11-717 were described (8). The plasmids p209NTUBR1FLAG, p454NTUBR1FLAG, p710NTUBR1FLAG, p866NTUBR1FLAG, and p1002NTUBR1FLAG, which encoded, respectively, UBR1209-1140f, UBR1454-1140f, UBR1710-1140f, UBR1866-1140f, and UBR11002-1140f, were derivatives of pUBR1NT1140FLAG (8), a high copy plasmid that expressed C-terminally FLAG-tagged UBR11-1140f from the yeast PADH1 promoter. The FLAG tag was located at the C terminus of the UBR1 derivatives except for the full-length fUBR1 and fUBR11-717. UBR1 test proteins remained intact in yeast extracts that were prepared and incubated as described previously (8).

Expression and Purification of X-SCC1-GST—A set of three pTYB12-X-SCC1-GST plasmids, which expressed Intein-CBD-X-SCC1-GST fusions (X = Arg, Leu, or Met), was employed for glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assays. Details of construction are available upon request. A specific pTYB12-X-SCC1-GST plasmid was cotransformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) together with pRI952, which expressed tRNAs for the codons AGG, AGA, and AUA that are rare in E. coli (60). A fresh E. coli colony was inoculated into LB medium (600 ml) containing ampicillin (0.1 mg/ml) and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), followed by growth at 37 °C until A600 of 0.5-0.8. Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was then added to the final concentration of 0.4 mm, followed by a 10-h incubation, with shaking, at 18 °C. The cells were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and frozen in liquid N2. For isolation of proteins, the cell pellet was thawed at 0 °C and then resuspended in lysis buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 m NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) containing protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) (6 ml of buffer per1gof pellet), and cells were disrupted by sonication on ice. The suspension was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated chitin column (10-ml bed volume), at a rate not higher than 0.5 ml/min, and washed with 200 ml of column buffer (0.5 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5), at 1 ml/min. The column was then flushed quickly with 30 ml of freshly prepared cleavage buffer (column buffer containing 40 mm dithiothreitol); the flow was stopped, and the column was incubated at 23 °C for 16 h. X-SCC1-GST proteins were eluted with 30 ml of column buffer, concentrated with Centriplus (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and dialyzed against column buffer at 4 °C. The resulting samples were stored in small aliquots at -80 °C. The presence of desired N-terminal residues in the purified X-SCC1-GST proteins was verified using N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation. GST-CUP9 was expressed and purified as described (8).

Expression and Purification of fUBR1 and UBR11-1140f—To express and purify the C-terminally FLAG-tagged UBR11-1140f, S. cerevisiae (SC295) carrying pUBR1NT1140FLAG was grown to A600 of ∼1.5, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation. The lysate was prepared as described (8), using lysis buffer (10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 m KCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.1), followed by the addition of anti-FLAG beads (Sigma), 1-h incubation with rocking, washing of the beads with lysis buffer, and the elution of UBR11-1140f with the FLAG peptide at 0.2 mg/ml in lysis buffer lacking Nonidet P-40. The expression and purification of N-terminally FLAG-tagged full-length UBR1 (fUBR1) were similar to that of UBR11-1140f, with modifications. A single colony of SC295 S. cerevisiae transformed with the pFLAGUBR1SBX was inoculated into 20 ml of yeast SD medium and grown at 30 °C to A600 of ∼1. The 20-ml culture was re-inoculated into 2 liters of SD medium and grown to A600 of ∼1, followed by the addition of equal volume of yeast YPD medium. The cells were grown for ∼3 more generations, until A600 of ∼4, harvested by centrifugation, washed once with cold 1× PBS, and frozen in liquid N2. Other procedures, including purification, were identical to those with UBR11-1140f. Concentrations of purified fUBR1 and UBR11-1140f were determined using the Protein Assay reagent (Bio-Rad). Samples of purified fUBR1 and UBR11-1140f were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at -80°C.

GST Pulldown Assays and Related Procedures—An SCC1-based GST fusion protein (∼2 μg) (see above) was diluted to 0.3 ml in PBS-based buffer (10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4.3 mm Na2HPO4, 1.4 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and incubated with 20 μl of glutathione-Sepharose-4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 30 min at 4 °C. The beads were washed once with 0.5 ml of PBS-based buffer and twice with 0.5 ml of GST pulldown buffer (10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm NaCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.6). The washed beads, in 0.15 ml of the binding buffer, were incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with 0.1 ml of S. cerevisiae extract (∼5 mg/ml total protein) containing either fUBR1 (N-terminally FLAG-tagged UBR1) or its truncated derivatives (see above) at the same concentration. These assays were performed in either the presence or absence of specific amino acids or amino acid derivatives, including dipeptides (Sigma), at concentrations indicated in figure legends. Binding assays also contained ovalbumin (Sigma; at 0.1 mg/ml, unless not stated otherwise), protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and 50 μm bestatin (Sigma). The beads were washed twice with 0.2 ml of the binding buffer either containing or lacking specific dipeptides, depending on whether a binding assay contained them. Washed beads were resuspended in 30 μl of SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heated at 95 °C for 4 min, and 15-μl samples were subjected to SDS-10% PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma).

CUP9-based GST pulldown assays with fUBR1 were carried out similarly except for the following: the total volume was 0.26 ml, with 1 μl of purified fUBR1 (0.4 mg/ml), either in binding buffer (10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm NaCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5), or in binding buffer supplemented with 60 μl of S. cerevisiae“empty” extract (no FLAG-tagged UBR1), or in GST-binding buffer containing ovalbumin (at 10 mg/ml); or in 0.2 ml of binding buffer supplemented with 60 μl of S. cerevisiae extract containing fUBR1. With UBR11-1140f, the assay was performed similarly, except that the reaction volume was 0.23 ml (0.2 ml of binding buffer plus 30 μl of extract from S. cerevisiae that produced UBR11-1140f) or, alternatively, the same (30 μl) volume but containing 1 μl of purified UBR11-1140f (at 0.2 mg/ml), and ovalbumin at 50 mg/ml, as described in figure legends.

In another binding assay, we employed pyCUP9his6, a purified (after overexpression in E. coli), GST-lacking, full-length CUP9 bearing the N-terminal “polyoma” (py) epitope tag that could be detected with a monoclonal antibody (61) (AK6967; a gift from Dr. S. Stevens and Dr. J. Abelson (Caltech)). 0.25 ml of fUBR1-containing yeast extract (∼5 mg/ml total protein) was incubated with 15 μl of anti-FLAG M2 affinity beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 1 h. The beads were then washed with 1 ml of lysis buffer (0.2 m KCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40), twice with 1 ml of lysis buffer containing 0.6 m KCl, once with 1 ml of lysis buffer, and twice with 0.5 ml of GST pulldown buffer (see above). The washed beads were incubated in 0.2 ml of GST pulldown buffer at 4 °C for 1 h with 2 or 4 μl of purified pyCUP9his6 (0.8 mg/ml), either alone or in the presence of fUBR1-lacking yeast extract (60 μl; 5 mg/ml total protein). Some of assay samples also contained Arg-Ala and Leu-Ala dipeptides, at 1 mm each (Sigma). In addition, all assay samples contained 0.1 mg/ml ovalbumin, a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) and 50 μm bestatin (Sigma). Incubated samples were processed by washing anti-FLAG affinity beads twice with 0.2 ml of GST pulldown buffer (containing dipeptides at the same concentrations as in incubated samples), and the bound proteins were eluted with 0.5 mg/ml FLAG peptide in GST pulldown buffer, followed by SDS-10% PAGE and immunoblotting with antibody to the Py epitope.

X-Peptide Pulldown Assays—Procedures were similar to those described previously (8, 29, 31, 32). Residues 2-9 of synthetic 12-mer X-peptides (X-Ile-Phe-Ser-Thr-Asp-Thr-Gly-Pro-Gly-Gly-Cys, where X = Arg, Phe, or Gly), were derived from residues 2-9 of Sindbis virus polymerase nsP4, a previously identified N-end rule substrate (1, 62). Hence the acronym for a specific X-peptide, “X-nsP4pep.” 20 μl (5 mg/ml total protein) of S. cerevisiae extract containing (overexpressed) S. cerevisiae UBR1 or its fragments (indicated above) was diluted into 0.2 ml of binding buffer (10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 m KCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5) in the presence of 0.1 mg/ml ovalbumin, protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), and 50 μm bestatin. The samples were incubated with 5 μl (packed volume) of a carrier-linked X-nsP4pep for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were pelleted by a brief centrifugation and then washed with 0.3 ml of binding buffer three times. The beads were then resuspended in 30 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heated at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by a brief centrifugation in a microcentrifuge, SDS-10% PAGE of 3-μl samples of supernatants, and detection of FLAG-tagged UBR1 or its fragments by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG M2 antibody.

Labeling, Purification, and Analysis of X-Peptides—The above peptides were also employed as probes in the fluorescence polarization (FP) assay. To conjugate Alexa Fluor-488-C5 maleimide (Invitrogen) to C-terminal Cys of an X-nsP4pep, this dye (0.6 μmol in 90 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) was added to 0.4 μmol of X-nsP4pep in 90 μl of DMSO, followed by incubation at room temperature for 4 h. Alexa-labeled X-peptides were purified by HPLC, using analytical scale VYDAC column (C18 reverse phase), followed by verification of purified peptides by mass spectrometry. The concentration of labeled X-peptides was measured by using either BCA reagent (Pierce) or N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation, or amino acid analysis, with similar results.

Fluorescence Polarization Assay—The concentration of fluorescently labeled X-peptides was kept at 10 nm. Before carrying out the FP assay, we ascertained that the levels of background fluorescence of the binding buffer (10% glycerol, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 m KCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.1), of the competitor (unlabeled) dipeptides or X-peptides, and of the UBR11-1140f protein (in the same buffer), at their highest concentrations used, were low enough, less than 5% of the fluorescence of a labeled X-nsP4pep in the assay. The FP assay (63, 64) was carried out as described in the published protocol (“Fluorescence Polarization: Technical Resource Guide” (PanVera Corp., now a part of Invitrogen)), with the following modifications. Purified UBR11-1140f was serially diluted into ∼14 microcentrifuge tubes, covering the range of its concentrations from more than 10-fold below (estimated) dissociation constant (Kd) of UBR11-1140f interactions with a cognate peptide to more than 10-fold above estimated Kd. Identical samples of an Alexa-labeled X-nsP4pep were added to each of the above tubes, gently mixed, and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min, in the final volume of 50 μl. FP measurements were carried out using the Analyst AD&HT Assay Detection System (Molecular Devices, Sunny-vale, CA) and a xenon-arc lamp as a light source, in a standard FP configuration, with filter settings optimized for the excitation wavelength of 485 nm and the emission wavelength of 530 nm. Two fluorescence measurements were collected for each well, with either parallel (S and S) or perpendicular (S and P) polarizers. These data were used to calculate polarization, in millipolarization units (mP), by the Analyst System. The affinities, expressed as Kd values, were calculated from the above data. Their statistical significance was estimated by nonlinear regression analysis, using Prism (Graphpad, San Diego, CA). FP-based competition assays were carried out similarly, except that concentration of UBR11-1140f was kept constant, and (unlabeled) competitor X-peptides were added to the binding assay. The concentration of UBR11-1140f in competition FP assays was close to the Kd value (∼1 μm; see “Results”) of the UBR11-1140f interaction with Arg-nsP4pep.

Surface Plasmon Resonance BIAcore Assay—The X-peptides Phe-nsP4pep, Arg-nsP4pep, or Gly-nsP4pep were linked, through their C-terminal Cys (see above), to biotin, using EZ-Link PEO-Iodoacetyl Biotin (Pierce), to allow immobilization of peptides onto streptavidin-coated SA sensor chips of BIAcore-2000 (Biacore). Biotin-labeled X-peptides were purified by HPLC, using analytical scale VYDAC column (C18 reverse phase), followed by verification of purified peptides by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight. The concentration of labeled X-peptides was measured using EZ™-Biotin quantification kit (Pierce). A biotin-containing X-peptide, at 0.1 μm in the running buffer (0.02% Nonidet P-40, 0.2 m KCl, 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5), was injected over the sensor chip surface at 10 μl min-1 at 25 °C, resulting in the surface density for the X-peptide of 30-35 resonance units. Purified UBR11-1140f was serially diluted in running buffer and injected at 75 μl min-1 for 80 s at 25 °C. After 5 min, to allow dissociation of the formed complexes, the sensor chip was washed by two 1-min injections of 2 m MgCl2 at 50 μl/min. BIAcore readouts were corrected by subtracting readouts from the mock surface (lacking an X-peptide) as well as readouts from a buffer-only (control) injection. Raw data were processed using Scrubber (BioLogic Software, Australia) and CLAMP programs and the 1:1 Langmuir interaction model, with a correction for mass transport (65, 66).

UBR1-dependent in Vitro Ubiquitylation System—This completely defined system, consisting exclusively of purified recombinant proteins and small compounds, was described in Ref. 40 and in detail in Ref. 67. Briefly, C-terminally His6-tagged S. cerevisiae UBA1 (E1, Ub-activating enzyme) was overexpressed in S. cerevisiae SC295 and purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (His6 affinity) chromatography, immobilized Ub (“covalent” affinity) chromatography, and Superdex-200 gel filtration (68). S. cerevisiae RAD6 (UBC2) was overexpressed in E. coli and purified by fractionation over DEAE, Mono-Q, and Superdex-75 columns. N-terminally FLAG-tagged S. cerevisiae UBR1 (fUBR1) was overexpressed in S. cerevisiae, as described section above, and was purified by fractionation over immobilized anti-FLAG M2 antibody, immobilized RAD6, and Superdex-200 columns (Fig. 7D). N-terminally FLAG-tagged, C-terminally His6-tagged S. cerevisiae fCUP9his6 was expressed and labeled with [35S]methionine in E. coli, followed by purification over nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid and anti-FLAG M2 antibody columns. Details of these and related procedures are described in Ref. 67. We also employed a similarly produced, labeled, and purified pyCUP9his6 with a different N-terminal tag, called polyoma (py) that was bound by a monoclonal antibody (61) (AK6967; a gift from Dr. S. Stevens and Dr. J. Abelson (Caltech)). The in vitro ubiquitylation reactions contained the following components: 7 μm Ub, 50 nm UBA1, 50 nm RAD6, 50 nm UBR1, 550 nm 35S-labeled fCUP9his6, 25 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm ATP, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, and ovalbumin (as a carrier protein) at 0.5 mg/ml. Pairs of dipeptides were added to final concentrations specified in the legend to Fig. 8. All components except UBA1 were mixed on ice for 10 min; UBA1 was then added and reactions shifted to 30 °C. The reactions were carried out for 10 min and were terminated by adding an equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heating at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by SDS-10% PAGE and autoradiography.

FIGURE 7.

CUP9 mutants, UBR1-CUP9 interactions, and effects of macromolecular crowding on the specificity of interaction between purified proteins. A, map of the 306-residue CUP9 and its truncation mutants. B, GST pulldown assays with UBR11-1140f and GST fusions to indicated CUP9 derivatives (see also the legend to Fig. 4, “Experimental Procedures” and the main text). Lane 1, 5% refers to a directly loaded sample of UBR11-1140f-containing yeast extract that corresponded to 5% of the amount of extract in GST pulldowns of this panel. Lane 2, GST pulldown with UBR11-1140f and GST fusion to wild-type CUP9. Lanes 3-7, same as lane 2 but with GST fusions to CUP9 mutants. Lane 8, same as lane 2, but GST lacking the CUP9 moiety. The band of UBR11-1140f (retained on glutathione-Sepharose beads) is indicated. C, lane 1, same as lane 1 in B, except that the test S. cerevisiae extract contained full-length fUBR1. Lanes 2-9, GST pulldowns with fUBR1 and the indicated GST-CUP9 fusions. As indicated above the lanes, all samples except those in lanes 3 and 5 contained a mixture of Arg-Ala (RA) and Leu-Ala (LA) dipeptides, each of them at 1 mm (see“Experimental Procedures”). Lane 10, same as lane 2, but with GST alone. D, lane 1, molecular mass markers;single and double asterisks denote, respectively, 220 and 60 kDa. Lane 2, Coomassie-stained gel of purified full-length fUBR1. E, lane 1, same as lane 1 in C, but 2% of total fUBR1 in the assay. Lanes 2 and 3, same as lanes 3 and 2 (respectively) in C, but an independent experiment. Lane 4, same as lane 1 but with purified fUBR1. Lanes 5 and 6, same as lanes 2 and 3 but with purified fUBR1 to which was added an empty (lacking fUBR1) S. cerevisiae extract. Note that purified fUBR1 assayed in the presence of “added-back” yeast extract exhibited specific (dipeptides-dependent) binding to GST-CUP9 (lanes 5 and 6), indistinguishably from fUBR1 that had not been initially purified (lanes 2 and 3). F, lanes 1-4, same as lanes 1-4 in E but an independent experiment. Lane 4, same as lane 1, but 10% of the input sample of the purified fUBR1 (see lane 2 in D). Lanes 5 and 6, same as lanes 2 and 3 but with purified fUBR1. Note the lack of dependence of UBR1-CUP9 interaction on the presence of cognate dipeptides. Lanes 7 and 8, same as lanes 5 and 6 but GST pulldowns were carried out in the presence of added ovalbumin, at 10 mg/ml. G, lanes 1-3, same as lanes 1-3 in E or F, but an independent experiment. Lane 4, same as lane 4 in F, but an independent experiment. Lanes 5 and 6, same as lanes 7 and 8 in F, but with oval buminat 50 mg/ml. Lanes 7 and 8, same as lanes 5 and 6, but with purified EF1A added to the assay (to 1.2 mg/ml), instead of ovalbumin. Lanes 9 and 10, same as lanes 7 and 8, but in the absence of added EF1A. H, Coomassie-stained gel of purified EF1A (see “Experimental Procedures”). I, lane 1, same as lane in F, but an independent experiment. Lanes 2 and 3, same as lanes 2 and 3 in E or F, but with GST-CUP9L294P, a previously characterized missense mutant of CUP9 (in the region of its degron)that did not bind to UBR1 and was metabolically stabilized in vivo(8). Note the absence of binding of fUBR1 (in the extract) to GST-CUP9L294P, irrespective the absence or presence of dipeptides. Lane 4, same as lane 4 in F, but an independent experiment. Lanes 5 and 6, same as lanes 2 and 3 but with purified fUBR1. Note that purified fUBR1 binds to degron-impaired GST-CUP9L294P and does so irrespective of the presence or absence of dipeptides. J, lane 1, same as lanes 4 in F or I, but an independent experiment. Lanes 2 and 3, same as lanes 5 and 6 in F, but in the presence of ovalbumin (at 50 mg/ml). Lanes 4 and 5, same as lanes 2 and 3 but with GST-CUP9L294P, instead of “wild-type” GST-CUP9. K, lane 1, same as lane 1 in F, but an independent experiment. Lanes 2 and 3, same as lanes 2 and 3 in F and G, but with GST-CUP9222-306, an N-terminally truncated CUP9. Note the retention of specific (dipeptides-modulated) binding of this CUP9 derivative to fUBR1. Lane 4, same as lane 4 in F, but an independent experiment. Lanes 5 and 6, same as lanes 2 and 3 but with purified fUBR1. Lanes 7 and 8, same as lanes 5 and 6, but with added ovalbumin (ov), at 50 mg/ml. Note the restoration of specific binding. L, an alternative UBR1-CUP9 binding assay in which the interactions were probed using coimmunoprecipitation of fUBR1 and pyCUP9his6, a GST-lacking, full-length CUP9 bearing the N-terminal pyepitope tag (see “Experimental Procedures”). FLAG-tagged fUBR1 in the yeast extract was incubated with beads-immobilized anti-FLAG antibody, followed by isolation of fUBR1-bearing beads by centrifugation, washes with binding buffer, and incubation with either purifiedpyCUP9his6 alone(lanes2and3, upperpanel) or in the presence of (added) UBR1-lacking yeast extract (lanes 4-7). The incubations were carried out in either the absence (lanes 2, 4, and 6) or the presence of Arg-Ala (RA) and Leu-Ala (LA) dipeptides, each of them at 1 mm. The beads containing immobilized fUBR1 were pelleted by centrifugation and washed, and the relative amounts of retained pyCUP9his6 were then determined by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-py antibody (see “Experimental Procedures”). The upper panel shows the amounts of pyCUP9his6 that were bound to fUBR1 in the absence of added yeast extract (lanes 2 and 3) or in the presence of extract. Lane 1 shows the amount of pyCUP9his6 that corresponds to 10% of its input in each of the binding assays. The lower panel is the result of SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (with anti-FLAG antibody) of fUBR1 that was eluted from anti-FLAG beads by the FLAG peptide, to verify the approximate equality of “input” levels of fUBR1 in each assay. Note that in the absence of added (UBR1-lacking) yeast extract, the interaction between fUBR1 and pyCUP9his6 was nonspecific, in that it was independent of the absence or presence of cognate dipeptides (lanes 2 and 3; compare with lanes 4-7). Lanes 6 and 7, same as lanes 4 and 5, but the input pyCUP9his6 was 2-fold higher.

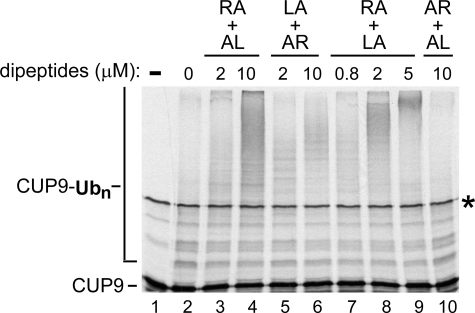

FIGURE 8.

Synergistic effects of type-1/2 dipeptides in a UBR1-dependent ubiquitylation system. Reactions consisting of purified S. cerevisiae Ub, purified UBA1 (E1, Ub-activating enzyme), RAD6 (the N-end rule pathway E2, Ub-conjugating enzyme), UBR1 (the N-end rule pathway E3 Ub ligase), 35S-labeled, purified CUP9, and ATP were supplemented with pairs of purified dipeptides, at indicated concentrations. The pairs of added dipeptides were Arg-Ala plus Ala-Leu (RA+AL), or Leu-Ala plus Ala-Arg (LA+AR), or Arg-Ala plus Leu-Ala (RA+LA), or Ala-Arg plus Ala-Leu (AR+AL). The reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 10 min, followed by SDS-10% PAGE and autoradiography (see “Experimental Procedures”). Unmodified CUP9 and CUP9-linked poly-Ub chains are indicated on the left. Asterisk on the right denotes a protein present in the initial CUP9 sample, possibly an SDS-resistant dimer of CUP9. Lane 1, purified CUP9 (input). Lanes 2-10, same as in B, but a set of independently performed reactions, with different concentrations of added dipeptide pairs. Note a synergistic enhancement of CUP9 polyubiquitylation in the presence of RA+LA (lane 9).

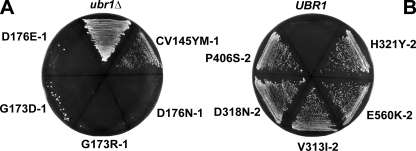

Genetic Screen for Type-1 and Type-2 UBR1 Mutants—Fig. 1B describes the design of the screen. Reporter plasmids expressing either Arg-URA3 (a type-1 N-end rule substrate) and Leu-βgal (a type-2 N-end rule substrate) (pDSRULB plasmid) or Leu-URA3 (a type-2 substrate) and Arg-βgal (a type-1 substrate) (pDSLURB plasmid) were transformed into S. cerevisiae JD55, a ubr1Δ strain. pRBUBR1, a high copy plasmid expressing UBR1 from the PADH1 promoter, was mutagenized by treatment with 1 m hydroxylamine for 1 h at 75°C. DNA was precipitated with ethanol, redissolved in 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and hydroxylamine was removed using G-25 spin-desalting column (Roche Applied Science). Hydroxylamine-treated pRBUBR1 was transformed into JD55 (ubr1Δ) carrying one of two reporter plasmids, either pDSRULB or pDSLURB. The transformants were plated onto SD(-Ura) plates, and the resulting Ura+ colonies (cells that were, presumably, impaired in degrading either Arg-URA3 or Leu-URA3) were replica-plated onto galactose-containing SG plates. The colonies on SG plates were stained for βgal using XGal overlay. Most of the colonies in these experiments stained blue. Because the cells of these colonies were selected, in the preceding step, to be impaired in the degradation of one class (type-1 or type-2) of N-end rule substrates, the failure to degrade an X-βgal that belonged to the other class of N-end rule substrates (type-2 or type-1, respectively) meant that the corresponding alleles of UBR1 were defective in degrading both classes of N-end rule substrates However, some white colonies on XGal were produced as well, with each of the two bi-reporter plasmids, pDSRULB and pDSLURB. The corresponding pRBUBR1 plasmids were rescued from these white colonies and were retransformed into the JD55 (ubr1Δ) cells carrying other reporter plasmids, either pBAM (Met-URA3), or pBAR (Arg-URA3), or pBAL (Leu-URA3). The resulting transformants were plated onto either SD (+Ura) or SD(-Ura) to verify that the corresponding variants of UBR1 were indeed selectively impaired in the degradation of either type-1 or type-2 N-end rule substrates.

Mapping Type-1/2 Mutations in UBR1—Five fragments of S. cerevisiae UBR1, from the pRB208 plasmid, were produced using the following restriction endonucleases: fragment I, SmaI-SpeI (nt 1-510 of the UBR1 ORF); fragment II, SpeI-BglII (nt 510-1, 653); fragment III, BglII-BalI (nt 1, 653-3, 511); fragment IV, BalI-XbaI (nt 3,511-4,515); and fragment V, XbaI-PstI (nt 4,515-beyond the end of ORF). Each of these fragments was replaced, in the non-mutant pRBUBR1, by the corresponding fragments from a rescued and amplified mutant pRB208, yielding five pRBUBR1-derived plasmids for every mutant plasmid. The five plasmids were transformed, separately, into JD55 (ubr1Δ) cells carrying either pBAR (Arg-URA3) or pBAL (Leu-URA3), and the transformants were tested for their ability to grow in the absence of uracil. This way we identified the regions of relevant alterations in the UBR1 ORF. The corresponding fragments were then sequenced to identify the actual alteration(s).

Pulse-Chase Analysis—S. cerevisiae in liquid SD medium containing 0.1 mm CuSO4 (A600 0.5-1) were labeled for 2 min at 30 °C with 0.15 mCi of [35S]methionine/cysteine (EXPRESS, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) as described (21, 52). Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.3 ml of SD medium containing 10 mm l-methionine and 0.5 mg/ml cycloheximide, and incubated further at 30 °C. Samples of 0.1 ml were removed during the incubation and added to microcentrifuge tubes containing 0.5 ml of 0.5-mm glass beads and 0.7 ml of lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.15 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma)). The cells were lysed by vortexing with glass beads, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-ha antibody (Covance, Princeton, NJ), SDS-PAGE, autoradiography, and quantitation (21, 56). Immunoprecipitation of labeled CUP9-FLAG was carried out as described (39).

β-Galactosidase and Other Assays—Cells in 5-ml cultures (A600 0.8-1) were pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 2 min and lysed with glass beads in 20% glycerol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 8, and the activity of βgal was measured in the clarified extract using o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactoside, as described (50, 69). The activity was normalized to the total protein concentration, determined using Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). For growth-dilution assays, S. cerevisiae strains were grown under selection for plasmids in SD medium to an A600 of 0.8-1. Cells (1.5 × 107) from each sample were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of water. 4-Fold serial dilutions of cell cultures were set up in microtiter plates as described (39), and cell suspensions were transferred to various media using a 48-pin applicator, followed by incubation at 30 °C for ∼36hto assay for growth.

RESULTS

UBR1 Mutants That Are Selectively Defective in Targeting Type-1 or Type-2 N-end Rule Substrates—To locate the regions of S. cerevisiae UBR1 that encompass its type-1 and type-2 substrate-binding sites (see Introduction), and to determine whether these apparently distinct sites (1, 28, 69) are sufficiently modular (independent) to be selectively perturbed by mutations, we carried out a screen described in Fig. 1B and “Experimental Procedures.” A plasmid that expressed Arg-URA3 (a type-1 N-end rule substrate) and Leu-βgal (a type-2 N-end rule substrate), or an otherwise identical plasmid that expressed a “converse” set of reporters, Leu-URA3 (a type-2 substrate) and Arg-βgal (a type-1 substrate), were transformed into ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae, which lacked the N-end rule pathway. pRBUBR1, a high copy plasmid expressing UBR1, was mutagenized in vitro with hydroxylamine and transformed into ubr1Δ cells carrying one or the other of the double-reporter plasmids (Fig. 1B). By replica-plating transformants on uracil-lacking SD plates, we could identify cells in which an X-URA3 reporter remained long lived in the presence of pRBUBR1 from the mutagenized pool, as those cells were Ura+, because of higher steady-state levels of URA3. (Both Arg-URA3 and Leu-URA3 were long lived in ubr1Δ cells but short lived in wild-type cells (1, 70).) Ura+ colonies were then plated on galactose-containing SG plates. The levels of galactose-induced Arg-βgal (in the Leu-URA3-expressing plasmid) or Leu-βgal (in the Arg-URA3-expressing plasmid) could then be assessed by staining the colonies with XGal. A blue, i.e. high-βgal colony (which already proved to be Ura+ at the preceding step of the screen), would imply the presence of a UBR1 allele that was impaired in degradation of both type-1 and type-2 substrates (Fig. 1B). Most colonies in these experiments stained blue. The rare white colonies on XGal suggested the presence of UBR1 variants selectively impaired in one but not the other of two substrate-binding sites. The pRBUBR1 plasmids were rescued from these colonies and were retransformed into ubr1Δ cells carrying either Met-URA3 (not an N-end rule substrate and a relatively long lived protein), or Arg-URA3 (type-1 substrate), or Leu-URA3 (type-2 substrate). Plating transformants on either SD (+Ura) or SD (-Ura) plates could verify whether the corresponding variants of UBR1 were selectively impaired in the degradation of type-1 or type-2 N-end rule substrates (Fig. 1B).

The initial screen involved ∼2,000 transformants bearing mutagenized UBR1. With each of two reporter plasmids, ∼10% of these transformants were Ura+. Among these, no UBR1 isolates were found that were unable to confer instability on a type-1 N-end rule substrate (basic N-terminal residues) but retained the activity against a type-2 substrate (hydrophobic N-terminal residues). However, this screen did yield five putative UBR1 variants of the opposite kind (active against type-1 but not type-2 N-end rule substrates). A more extensive screen, with ∼1 × 106 transformants, was then carried out exclusively for UBR1 variants of the former class (active against type-2 but not type-1 substrates). It yielded ∼17,000 Ura+ colonies, i.e. isolates in which Arg-URA3 was at least partially stabilized. 20 of these colonies showed low levels of βgal in the XGal assay (i.e. they retained degradation of Leu-βgal). The pRBUBR1 plasmids encoding 20 putative type-1-impaired and 5 putative type-2-impaired UBR1 variants were rescued, and the specificity of their targeting defects was confirmed by re-testing them in ubr1Δ cells expressing either Arg-URA3 and Leu-βgal or Leu-URA3 and Arg-βgal, using, in particular, pulse-chase and immunoblot assays (data not shown; see also below).

Identifying Mutations in UBR1—The approximate locations of mutations within the 5,850-bp UBR1 ORF were determined through fragment swapping between wild-type and mutant UBR1s, using unique restriction sites to divide UBR1 into five nonoverlapping fragments (see “Experimental Procedures”). Once localized to a specific fragment, the actual mutation was determined by DNA sequencing. All of the type-1 and type-2 mutations were located in the N-terminal 30% of UBR1. Among ∼20 type-1 mutant isolates of UBR1 (those active with type-2 substrates but inactive with type-1 substrates), only 5 different amino acid changes were present, with 18 of the 20 mutations affecting either Asp176 or Gly172 (Fig. 1C). All of recovered type-1 mutations in UBR1 were missense alterations, one of them a double missense, in two adjacent residues. Specific changes in the type-1 UBR1 mutants were C145Y/V146M (a double missense; one isolate); G172R (seven isolates); G172E (four isolates); D176N (five isolates); and D176E (two isolates), encompassing an ∼30-residue region of UBR1 (positions 145-176) (Fig. 1C). In contrast to type-1 UBR1 mutants, all five of the type-2 UBR1 mutants contained different amino acid alterations; collectively, these (type-2) alterations encompassed a different and larger region of UBR1 (positions 313-560). Specific type-2 alterations were V313I; D318N; H321Y; P406S; and E560K (Fig. 1C). Together, the identified type-1 and type-2 mutations spanned a 416-residue stretch within the first 560 residues of the 1,950-residue UBR1 protein.

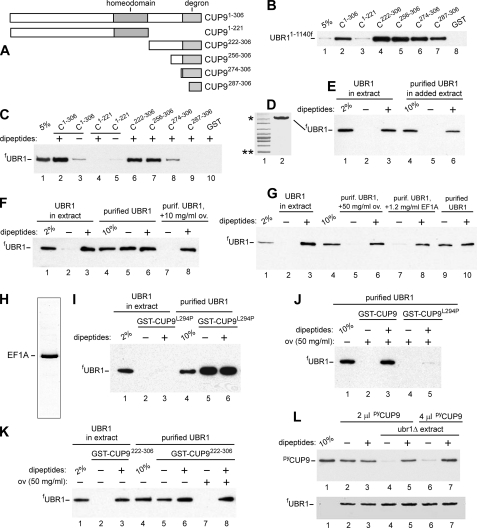

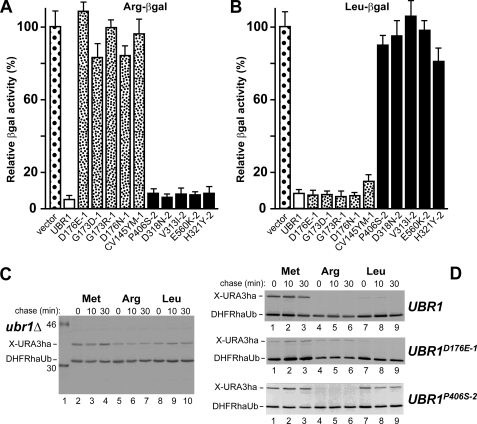

Degradation of N-end Rule Substrates in Type-1 or Type-2 UBR1 Mutants—Specific type-1 and type-2 S. cerevisiae UBR1 mutants were verified and further characterized by transforming the corresponding UBR1-expressing plasmids into JD55 (ubr1Δ) S. cerevisiae carrying pRβgalUPR or pLβgalUPR. The latter are low copy plasmids expressing, respectively, Arg-βgal or Leu-βgal reporter N-end rule substrates. The relative rates of in vivo degradation of X-βgals were assessed using extensively validated (9, 24) steady-state measurements of βgal activity in whole cell extracts from ubr1Δ cells that carried plasmids expressing specific UBR1 mutants (Fig. 2, A and B). The results confirmed the initial screen-derived data that Arg-βgal was long lived in the presence of type-1 UBR1 mutants, but was degraded with type-2 UBR1 mutants. Conversely, Leu-βgal was long lived in the presence of type-2 UBR1 mutants but short lived with type-1 UBR1 mutants (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition to steady-state levels of N-end rule substrates (Fig. 2, A and B), their metabolic stability was also assessed by pulse-chase analysis, using the Ub-protein-reference (UPR) technique (21, 57). This method provides a “built-in” (long lived) reference protein as a part of reporter fusion, and thereby increases the accuracy of pulse-chase and analogous assays. In agreement with steady-state data (Fig. 2, A and B), Arg-URA3 was relatively long lived in type-1 UBR1 mutants, exemplified by UBR1D176E-1 cells (the superscript suffixes “-1” or “-2” denote the inactivation of, respectively, the type-1 or type-2 substrate-binding sites of UBR1). In contrast, Leu-URA3 was short lived in a type-1 mutant (Fig. 2D and data not shown; see also Fig. 1C). “Conversely,” Leu-URA3 was relatively long lived in type-2 UBR1 mutants, exemplified by UBR1P406S-2, whereas Arg-URA3 was short lived in the same mutant (Fig. 2D and data not shown; see also Fig. 1C). (Both Arg-URA3 and Leu-URA3 were long lived in the absence of UBR1 (Fig. 2C).)

FIGURE 2.

Selective inactivation of type-1 versus type-2 substrate-binding sites in UBR1 mutants. A, wild-type UBR1 and its mutant alleles were expressed from low copy plasmids in S. cerevisiae JD55 (ubr1Δ) cells that also carried a plasmid expressing Arg-βgal (Ub-Arg-βgal) reporter (see “Experimental Procedures”). Measurements of βgal activity in cell extracts were used to compare the rates of X-βgal reporter degradation in vivo (9, 21). The values shown are the means of duplicate measurements of three independent transformants. Standard deviations are indicated above the bars. For the locations of indicated mutations in UBR1, see Fig. 1C. B, same as in A but with cells expressing Leu-βgal (Ub-Leu-βgal). C, pulse-chase assays, using a UPR-type construct (21, 57) expressing either Met-URA3ha, or Arg-URA3ha, or Leu-URA3ha in ubr1Δ cells (see “Experimental Procedures”). Lane 1, molecular mass marker; their masses, in kDa, are indicated on the left. D, same as in C, but with ubr1Δ cells that expressed either wild-type UBR1, or its type-1 UBR1D176E-1 mutant, or its type-2 UBR1P406S-2 mutant. The 35S-bands of X-URA3ha reporters and the DHFRh-Ub reference protein are indicated.

UBR1-dependent Targeting of CUP9 Requires Intact Type-2 Binding Site of UBR1—Previous work has shown that the N-end rule pathway controls the import of short peptides (8, 39-41). Specifically, a third substrate-binding site of S. cerevisiae UBR1, apparently distinct from its two other (type-1 and type-2) binding sites, targets CUP9. The latter is a transcriptional repressor of, among other genes, PTR2, which encodes a plasma-membrane transporter that can import di- and tripeptides. UBR1 targets CUP9 for ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation through a distinct internal (non-N-terminal) degron of CUP9. In wild-type cells, peptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues bind to the type-1 and type-2 binding sites of UBR1 and thereby allosterically activate its otherwise autoinhibited third site for binding to CUP9 (8, 40). This reversal of autoinhibition leads to the targeting of CUP9 by UBR1, to accelerated degradation of CUP9, and thus to the induction of PTR2 expression and peptide import. The resulting positive feedback circuit allows S. cerevisiae to detect the presence of extracellular peptides and to react by increasing their uptake (8, 40). In ubr1Δ yeast, CUP9 is a relatively long lived protein (t½>50 min). As a result, the expression of PTR2 transporter is extinguished, making ubr1Δ cells incapable of importing peptides and therefore resistant to a toxic dipeptide such as Leu-Eth (39).

We employed the toxic peptide resistance assay to probe in vivo aspects of UBR1 mutants identified in this study work. Plasmids expressing type-1 or type-2 mutant alleles of UBR1 were transformed into ubr1Δ yeast, and the resulting transformants were streaked onto Leu-Eth (toxic peptide) plates. Growth of cells on such plates indicates that the CUP9 repressor is metabolically stabilized in these cells, resulting in a down-regulation of expression of PTR2 transporter and therefore in hyper-resistance of cells to Leu-Eth. The results showed that CUP9 was stabilized in cells transformed with all of type-2 UBR1 mutants (Fig. 3B), but it was still degraded in cells transformed with four of the five type-1 UBR1 mutants (Fig. 3A). (With the fifth type-1 mutant, UBR1CV145YM-1 (Fig. 1C), cell growth on Leu-Eth plates was partially retarded relative to ubr1Δ strains.) These findings suggest that the third (CUP9-recognizing) site of UBR1 either structurally overlaps with the type-2 binding site or depends on this site for its function.

FIGURE 3.

In vivo effects of mutants in the type-1 or type-2 substrate-binding sites of UBR1. A, toxic-peptide (Leu-Eth) resistance assay (39, 41) (see “Experimental Procedures”) with ubr1Δ S. cerevisiae versus its derivatives that expressed type-1 UBR1 mutants (Fig. 1C). B, same as in A, but the assay was carried with type-2 UBR1 mutants, and the result with wild-type UBR1 is shown as well (Fig. 1C). See the main text for details.

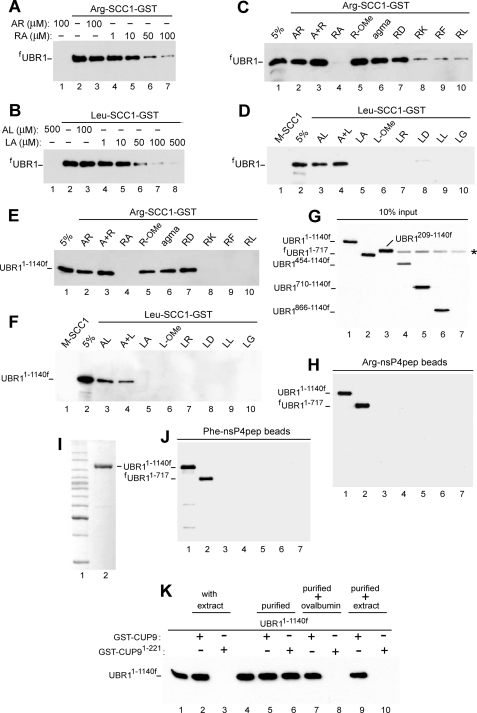

Specificity of UBR1 Interactions with N-end Rule Substrates and X-Peptides—Our previous work described the use of N-recognin ligands containing the GST moiety linked to the C terminus of a fragment of S. cerevisiae SCC1, a subunit of cohesin. This 33-kDa SCC1 fragment, which normally bears N-terminal Arg, is produced in yeast through the conditional cleavage by separase ESP1 and is degraded by the N-end rule pathway (43). Purified X-SCC1-GSTs (X = Arg, Leu, or Met) bearing type-1 (Arg), or type-2 (Leu), or stabilizing (Met) N-terminal residues were linked to glutathione-Sepharose, and the previously characterized (8) GST pulldown assay was carried out with yeast extracts that contained the overexpressed, FLAG-tagged, full-length fUBR1 or its derivatives (Fig. 4). Similarly to mouse UBR1 and UBR2 (31), S. cerevisiae fUBR1 did not bind to Met-SCC1-GST (Fig. 4D, lane 1) but bound to both Leu-SCC1-GST and Arg-SCC1-GST (Fig. 4, A and B, lanes 2). This binding was specific for type-1 versus type-2 N-terminal residues, as the Arg-Ala and Leu-Ala dipeptides selectively inhibited the binding of corresponding (“alternative”) X-SCC-GST reporters (Fig. 4, A and B). To probe specificity of this inhibition, we tested other small compounds as well. Whereas increasing concentrations of Arg-Ala inhibited the binding of Arg-SCC1-GST to fUBR1, neither Ala-Arg, nor an equimolar mixture of the corresponding free amino acids (Arg+Ala), nor Arg methyl ester (Arg-OMe), nor agmatine ((4-aminobutyl)-guanidine), the decarboxylation product of Arg and a putative neurotransmitter (71)) exhibited this effect (Fig. 4, A and C). Similarly, the binding of Leu-SCC1-GST to fUBR1 was inhibited by Leu-Ala but neither by Arg-Ala (31), nor by Ala-Leu, nor by Leu+Ala (a mixture of free amino acids) (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Specific interactions between UBR1 and its physiological substrates or model ligands. A, GST pulldown assays with full-length, FLAG-taggedfUBR1 and immobilized Arg-SCC1-GST. Equal amounts of extract from S. cerevisiae that expressed fUBR1 were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads preloaded with Arg-SCC1-GST, in the presence of indicated concentrations of either the Arg-Ala (RA) or Ala-Arg (AR) dipeptides. The beads-associated fUBR1 was eluted from the beads, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and detected by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody (see “Experimental Procedures”). B, same as in A but with Leu-SCC1-GST and either Leu-Ala (LA) or Ala-Leu (AL). C, same assay format, with Arg-SCC1-GST. Lane 1, 5% refers to a directly loaded sample of fUBR1-containing yeast extract that corresponded to 5% of the amount of extract in GST pulldowns of this panel. Lane 2, Arg-SCC1-GST pulldown assay with fUBR1 in the presence of 1 mm AR dipeptide (single-letter notations for amino acids). Lanes 3-10, same as lane 2 but with either A+R(1 mm free Ala and 1 mmfree Arg), or RA, or R-OMe (O-methyl ester), or agmatine (see the main text), or RD, or RK, or RF, or RL, all of them at 1 mm. D, same as in C but with Leu-SCC1-GST and different dipeptides or related compounds, as shown. Lane 1, Met-SCC1-GST (instead of Leu-SCC1-GST); note the absence of its interaction with fUBR1, in contrast to Leu-SCC1-GST and Arg-SCC1-GST. E, same as in C, but with UBR11-1140f, the N-terminal half of UBR1. F, same as in D but with UBR11-1140f. G, input samples of UBR11-1140f and its derivatives. Lane 1, UBR11-1140f. Lanes 2-7, fUBR11-717, UBR1209-1140f, UBR1454-1140f, UBR1710-1140f, UBR1866-1140f, and UBR1ha, respectively. These derivatives of UBR1 were overexpressed in S. cerevisiae as described for UBR11-1140f. The asterisk denotes a protein cross-reacting with anti-FLAG antibody. UBR1ha (lane 7) was employed as a (negative) control for antibody specificity. 10% input refers to a directly loaded sample of yeast extract that corresponded to 10% of the amount of extract in GST pulldowns of H and J. H, X-peptide assay (see “Experimental Procedures”) with UBR11-1140f and its derivatives, described in G. UBR11-1140f and fUBR11-717, but not the other UBR1 derivatives of G bound to immobilized Arg-nsP4pep peptide. I, lane 1, molecular mass markers. Lane 2, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE pattern of (overexpressed) UBR11-1140f that was purified from yeast extract using anti-FLAG affinity chromatography and used for GST-CUP9 pulldowns (see K and “Experimental Procedures”). J, same as in H but with immobilized Phe-nsP4pep peptide. K, lane 1, 2% input. Lane 2, GST-CUP9 pulldown with UBR11-1140f in S. cerevisiae extract. Lane 3, same as lane 2, but with GST-CUP91-221, a C-terminally truncated mutant of the 306-residue CUP9 that lacks its C-terminal degron (67). Note the absence of binding of UBR11-1140f (in yeast extract) to GST-CUP91-221, in contrast to its binding to full-length GST-CUP91-306. Lane 4, 10% input. Lane 5, same as lane 2 but with purified UBR11-1140f, as distinguished from UBR11-1140f in yeast extract. Lane 6, same as lane 5 but with GST-CUP91-221. Note that purified UBR11-1140f, in contrast to the same protein in yeast extract, binds to both degron-containing (lane 5) and degron-lacking CUP9 (lane 6). Lane 7, same as lane 5 but with ovalbumin (at 50 mg/ml) added to UBR11-1140f before GST pulldown with full-length GST-CUP9. Lane 8, same as lane 7 but with GST-CUP91-221. Note restoration of the binding specificity of UBR11-1140f in the presence of ovalbumin. Lanes 9 and 10, same as lanes 5 and 6 but “empty” yeast extract was added to purified UBR11-1140f before GST pulldowns with either full-length GST-CUP9 (lane 9) or degron-lacking GST-CUP91-221.

In agreement with earlier findings (8), both full-length fUBR1 and UBR11-1140f (N-terminal “half” of fUBR1) exhibited qualitatively indistinguishable patterns of binding specificity (Fig. 4, E and F), indicating that UBR11-1140f contained the type-1 and type-2 binding sites. It should be noted that whereas Arg-OMe (in contrast to Arg-Ala) did not inhibit the binding of Arg-SCC1-GST to either UBR11-1140f or full-length fUBR1, the analogous methyl ester Leu-OMe inhibited the binding of Leu-SCC1-GST apparently as efficaciously as did Leu-Ala (Fig. 4, C-F). Yet another difference between the inhibition patterns of type-1 and type-2 sites was a comparably strong inhibition, by either Leu-Ala or Leu-Asp, of the binding of Leu-SCC1-GST to UBR1 versus the absence of inhibition, by Arg-Asp (in contrast to Arg-Ala), of the binding of Arg-SCC1-GST to UBR1 (Fig. 4, C-F). Detailed understanding of these differences requires the knowledge of the crystal structure of UBR1.

The binding of UBR1 to destabilizing N-terminal residues of polypeptides was also examined using the X-peptide assay, which employed a set of otherwise identical 12-mer peptides (termed X-nsP4pep) whose sequence X-Ile-Phe-Ser-Thr-Asp-Thr-Gly-Pro-Gly-Gly-Cys (X = Arg or Phe) was derived, in part, from the N-terminal sequence of nsP4, the RNA polymerase of the Sindbis virus and a physiological N-end rule substrate (27, 62). Purified X-nsP4pep peptides were cross-linked to microbeads through their C-terminal Cys residue (8, 31, 32). Both full-length fUBR1 and several of its truncated derivatives were overexpressed in S. cerevisiae and assayed for their binding to either Arg-nsP4pep or Phe-X-nsP4pep. Whereas fUBR11-717, the 717-residue N-terminal fragment of the 1,950-residue UBR1, was capable of specific binding to X-nsP4pep peptides, shorter N-terminal fragments of UBR1 did not bind (Fig. 4, G and H). In addition, UBR1209-1140f, which differed from the binding-competent UBR11-1140f by deletion of the first 208 residues, did not bind to either Arg-nsP4pep or Phe-X-nsP4pep (Fig. 4, G, H and J). All of these findings were consistent with the conclusions from genetic mapping of the type-1 and type-2 sites (Fig. 1C).

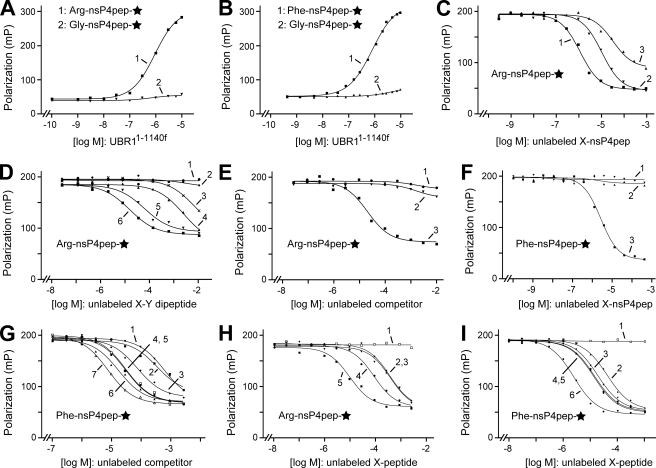

Measurements of Affinity between UBR1 and Peptide Reporters Using Fluorescence Polarization Assay—To measure the binding of UBR1 to different N-terminal residues of otherwise identical polypeptides, we employed both fluorescence polarization (FP) (63, 64, 66) and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (72, 73). These measurements used purified UBR11-1140f (Fig. 4I). Its specific binding to N-terminal residues of either protein-size substrates or short peptides was indistinguishable from that of full-length fUBR1 in GST pulldown assays (Fig. 4, A-F). The otherwise identical Arg-nsP4pep, Phe-nsP4pep, and Gly-nsP4pep peptides, with type-1 destabilizing, type-2 destabilizing, and stabilizing N-terminal residues, respectively (Fig. 1A), were C-terminally conjugated to Alexa Fluor-488, followed by purification of the resulting fluorescent peptides by HPLC and verification of their structures by mass spectrometry (see “Experimental Procedures”).

The concentration of X-nsP4pep♦ (C-terminal symbol denotes fluorescent tag) in FP assays was set at 10 nm, well below the (anticipated) micromolar range of affinities between UBR1 and test peptides. As expected (8), both Arg-nsP4pep♦ and Phe-nsP4pep♦ interacted with UBR11-1140f. The calculated Kd values (see “Experimental Procedures”) were ∼1.0 and ∼0.7 μm, respectively. In contrast, no binding to UBR11-1140f could be detected with the otherwise identical Gly-nsP4pep♦, i.e. the corresponding Kd was at least 0.1 mm or higher (Fig. 5, A and B). The affinities of X-nsP4pep peptides for UBR11-1140f were also measured in a competition FP assay, in which, for example, the binding of Phe-nsP4pep♦ to UBR11-1140f was titrated by the addition of Alexa lacking (unlabeled) Phe-nsP4pep (Fig. 5F). The corresponding Kd was ∼2 μm, close to the value deduced from direct binding FP assay (Fig. 5, B and F). In contrast, the competition by unlabeled Arg-nsP4pep (a type-1 destabilizing N-terminal residue) or by unlabeled Gly-nsP4pep (a stabilizing N-terminal residue) for the binding of Phe-nsP4pep♦ to UBR11-1140f was too weak to measure by FP (Fig. 5F). The Kd value of Arg-nsP4pep♦ binding to UBR11-1140f that was deduced from a similar competition assay, using unlabeled Arg-nsP4pep as a competitor, was ∼1.2 μm, close to the value of ∼1.0 μm from direct-binding assay (Fig. 5, A and C). Interestingly, however, the unlabeled Phe-nsP4pep could detectably compete with the binding of (labeled) Arg-nsP4pep♦ to UBR11-1140f (Fig. 5C), with the apparent Kd of ∼11 μm, i.e. Phe-nsP4pep was an ∼10-fold weaker inhibitor of the binding of Arg-nsP4pep♦ to UBR11-1140f than Arg-nsP4pep itself. As to unlabeled Gly-nsP4pep, its apparent binding to the type-1 site of UBR11-1140f was weaker still but could still be detected in this competition assay, with the corresponding (apparent) Kd of ∼36 μm (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Measurements of affinity between UBR11-1140f and peptides with different N-terminal residues using FP assay. A, purified UBR11-1140f (Fig. 4I) was incubated, at increasing concentrations, with either Arg-nsP4pep♦ peptide (curve 1) or Gly-nsP4pep♦ peptide (curve 2), each of them at 10 nm (C-terminal diamond in the text and a star in the figure denote a C-terminal fluorescent tag; see “Experimental Procedures”). Note the binding to Arg-nsP4pep♦ (bearing a type-1 destabilizing N-terminal residue) and the absence of significant binding to Gly-nsP4pep♦ (bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue). B, same as in A but with Phe-nsP4pep♦ versus Gly-nsP4pep♦ (curves 1 and 2, respectively). C, competition assay, with UBR11-1140f at 1 μm, Arg-nsP4pep♦ at 10 nm, versus increasing concentrations of unlabeled Arg-nsP4pep, Phe-nsP4pep, or Gly-nsP4pep (curves 1-3, respectively). D, same as in C but with unlabeled dipeptides as competitors, at indicated concentrations. Curves 1-6, LA, AR, FA, RD, RK, and RA, respectively (single-letter abbreviations for amino acids). E, same as in D, but with an equimolar mixture of Arg and Ala (curve 1), Arg-OMe (R-OMe) (curve 2), and Arg-Ala (RA) as unlabeled competitors. F, same as in C, but with fluorescent Phe-nsP4pep♦, with UBR11-1140f at 0.7 μm, and the competition with unlabeled Gly-nsP4pep, Arg-nsP4pep, or Phe-nsP4pep (curves 1-3, respectively). G, same as in D but with Phe-nsP4pep♦ as a labeled peptide, with UBR11-1140f at 0.7 μm, and with unlabeled dipeptides (or their derivatives) as competitors. Curves 1-7, LD, l-OMe (Leu-OMe), LG, LL, LR, LA, and WA, respectively. H, same as in G, but with Arg-nsP4pep♦ as a labeled peptide, with UBR11-1140f at 0.7 μm, and with unlabeled competitors GGGG, RGD, RGDS, RG, or RAGESGSGC (single-letter abbreviations for amino acids) (curves 1-5, respectively). The RAGES sequence of the latter peptide is identical to the N-terminal sequence of the separase-produced C-terminal fragment of SCC1, a physiological N-end rule substrate (see “Results” and “Discussion”). I, same as in H, but with Phe-nsP4pep♦ as a labeled peptide, with UBR11-1140f at 0.7 μm, and with unlabeled GGGG, FG, FGG, FGGF, FA, and Phe-nsP4pep peptide as competitors (curves 1-6, respectively).

We conclude that the type-1 and type-2 substrate-binding sites of UBR1 bind to the corresponding N-terminal residues of model substrates with approximately equal affinities (Kd of ∼1 μm). We also conclude that the UBR1 type-2 site, which binds to bulky hydrophobic N-terminal residues (Fig. 1A), is significantly more discriminating than the type-1 site. Specifically, we could not detect the binding of noncognate N-terminal residues to the type-2 site of UBR1, in either qualitative or quantitative assays (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, B and F), whereas a type-2 N-terminal residue could weakly compete with a type-1 N-terminal residue for the binding to the type-1 site of UBR1, and a stabilizing N-terminal residue could also compete, albeit even more weakly than a type-2 residue (Fig. 5, A-F).

We also carried out competition assays with unlabeled dipeptides and other dipeptide size compounds versus either Arg-nsP4pep♦ or Phe-nsP4pep♦ (Fig. 5, D, E and G). Some of these competitors were also used in qualitative binding assays (Fig. 4, D and E). The results of FP-based competition assays indicated that dipeptides (as distinguished from 12-mer X-nsP4pep peptides) with cognate N-terminal residues were significantly (5-10-fold) weaker competitors relative to unlabeled cognate X-nsP4pep peptides (Fig. 5, D and G), and that dipeptides (or analogous compounds) with noncognate N-terminal residues were either not competitors at all or much weaker competitors (see the legend to Fig. 5, D and G for details). Among the tested dipeptide sequences, Ala at position 2 of an otherwise cognate dipeptide (Arg-X or Leu-X) resulted in best competitor dipeptides, whereas a negatively charged (Asp) residue at position 2 significantly decreased the affinity of a dipeptide for the corresponding (type-1 or type-2) substrate-binding site of UBR1 (Fig. 5, D and G). A basic (Arg or Lys) residue at position 2 was not as detrimental for the interaction of dipeptide with UBR1 (Fig. 5, D and G).

Although the length of a competitor peptide is less important than whether or not it bears a cognate N-terminal residue, the data of Fig. 5, H and I, indicate that the length of a peptide (in the tested range) is a significant, apparently independent parameter that determines its affinity for UBR1. One possibility is that the C-terminal carboxyl group of the peptide (e.g. its negative charge) would weaken the binding of peptide to its cognate (type-1 or type-2) binding site of UBR1, unless the peptide is long enough to place its C-terminal carboxyl group away from the binding site. This interpretation would also account for the fact that free “cognate” amino acids (in contrast to dipeptides bearing them as N-terminal residues) do not bind to UBR1 (Fig. 4, C and E).

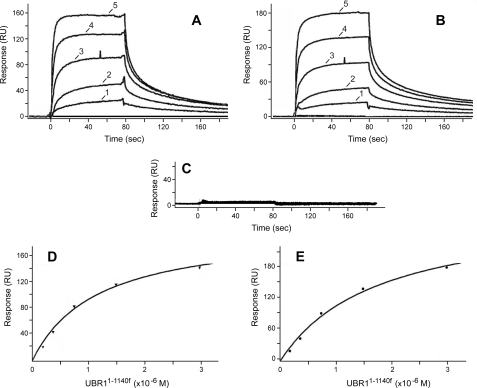

Measurements of Affinity between UBR1 and Model Peptides Using Surface Plasmon Resonance—To measure the affinity between UBR11-1140f and 12-mer X-nsP4pep peptides using a technique other than FP (Fig. 5), we employed SPR and BIAcore-2000 (65, 66, 72, 73). Phe-nsP4pep, Arg-nsP4pep, or Gly-nsP4pep, modified to bear a C-terminal biotin moiety (see “Experimental Procedures”), were immobilized on streptavidin-coated sensor chips. Purified UBR11-1140f (see Fig. 4I) was serially diluted in the running buffer and injected over the chip surface for 80 s. BIAcore readouts were corrected by subtracting readouts from the mock surface (lacking an X-peptide) as well as readouts from buffer-only (control) injections. Raw data were processed using Scrubber (BioLogic Software) and were globally fit using CLAMP (65), yielding the corresponding Kd values. As shown in Fig. 6, BIAcore detected the binding of UBR11-1140f to either Arg-nsP4pep (bearing a type-1 destabilizing N-terminal residue) or Phe-nsP4pep (bearing a type-2 destabilizing N-terminal residue), with the Kd values of ∼1.2 and ∼1.0 μm, respectively (Fig. 6), in excellent agreement with the results of FP-based measurements (Fig. 5 and see preceding section). In contrast, the otherwise identical Gly-nsP4pep, bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue, did not exhibit a detectable binding to UBR11-1140f (Fig. 6C). These BIAcore-based findings (Fig. 6) demonstrated yet again (in addition to GST pulldown and FP-based data) that at least the bulk of the in vivo specificity of UBR1 for N-end rule substrates (Fig. 1, A and B) (see Introduction) stems from differences in its physical affinity for destabilizing versus stabilizing N-terminal residues in the N-end rule.

FIGURE 6.

Measurements of affinity between UBR11-1140f and peptides with different N-terminal residues using surface plasmon resonance. A, BIAcore sensograms (see “Experimental Procedures”) illustrating the binding of UBR11-1140f to the immobilized 12-residue Arg-nsP4pep peptide, bearing a type-1 primary destabilizing N-terminal residue. RU, resonance units. Curves 1-5 correspond to the passing of purified UBR11-1140f, at either 0.188, 0.375, 0.75, 1.5, or 3 μm, over immobilized Arg-nsP4pep. B, same as in A but with immobilized Phe-nsP4pep, bearing a type-2 primary destabilizing N-terminal residue (Fig. 1A). C, same as in A but with Gly-nsP4pep bearing a stabilizing N-terminal residue (no detectable binding to UBR11-1140f at any of its tested concentrations). D and E, binding isotherms (derived from the data in A and B, respectively) for Arg-nsP4pep and Phe-nsP4pep (see “Experimental Procedures”).

Nonspecific Binding of Purified UBR1 to CUP9, and Restoration of Specificity through Chaperones and Macromolecular Crowding—Through its type-1 and type-2 sites, the 225-kDa UBR1 can bind to primary destabilizing N-terminal residues in proteins or short peptides apparently “nonconditionally,” i.e. under all conditions tested (8) (Figs. 4, 5 and 6). In contrast, UBR1 can bind, through its third binding site, to its physiological substrate CUP9 only if the type-1 and type-2 sites of UBR1 are occupied by cognate N-terminal residues of ligands such as dipeptides (8) (e.g. Fig. 7, E-G, lanes 2 and 3). This dependence of the UBR1-CUP9 interaction (via the C terminus-proximal degron of CUP9 (8) (Fig. 7, B and C)) on the state of occupancy of other two binding sites of UBR1 yields, in vivo, a positive feedback circuit through which S. cerevisiae can sense the presence of extracellular peptides and accelerate their uptake (8, 40) (see Introduction). The negligible binding of CUP9 by UBR1 in the absence of occupancy of its type-1/2 sites (e.g. Fig. 7, E-G, lanes 2 and 3) is thus the consequence of a negligible fraction of UBR1 molecules, under these conditions, that exhibit an “open” (active) CUP9-binding site.

The binding of type-1/2 ligands to the corresponding sites of UBR1 increases, in an ensemble of UBR1 molecules, the probability of a conformational transition that “opens up” the CUP9-binding site of UBR1 (8). The type-1/2 sites of UBR1 encompass its N-terminal and proximal UBR domain (Fig. 1C and Introduction). The allosteric influence of UBR1-bound dipeptides on the probability of transition that induces the UBR1-CUP9 interaction was shown to require the evolutionarily conserved C-terminal region of UBR1 that includes two critical cysteines, Cys1703, and Cys1706 (8). In particular, UBR11-1140f, the N-terminal “half” of UBR1, retains all three of its substrate-binding sites but exhibits a constitutively open (active) CUP9-binding site. More recent findings, using UBR1 derivatives that contained sequences allowing site-specific cleavages of UBR1, indicated that a conformational transition in UBR1 that “opens up” its CUP9-binding site is “subtle” in that it does not appear to involve a large scale repositioning of UBR1 domains.4

GST pulldowns with UBR1 versus GST-CUP9 were carried out in the presence of yeast extract (8) (e.g. Fig. 7, E-G, lanes 2 and 3). We repeated these assays with purified UBR1 (see “Experimental Procedures”) and GST-CUP9. Surprisingly, the specificity of UBR1-CUP9 interaction, i.e. its dependence on the presence of dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues, as well as its dependence on the presence of C-terminal degron of CUP9 (67) were abolished with purified UBR1; it bound to GST-CUP9 irrespective of the presence or absence of dipeptides and irrespective of the presence or absence of the UBR1-specific degron of CUP9 (Fig. 7, C and F, and data not shown). These effects of using purified UBR1 (as distinguished from UBR1 in the presence of yeast extract) were also observed with its N-terminal fragment UBR11-1140f (Figs. 4K and 7B). For example, in the presence of yeast extract, UBR11-1140f bound to CUP9 constitutively (i.e. independently of the presence of dipeptides) (8) but specifically (i.e. depending on the presence of the CUP9 degron) (Fig. 7B). However, purified UBR11-1140f bound either to full-length CUP9 (containing its C-terminal degron) or to C-terminally truncated CUP91-221 that lacked the degron (Fig. 4K, lanes 1-6). The same pattern was observed with purified full-length UBR1 versus CUP9L294P that contained a previously characterized degron-inactivating missense mutation (8) (Fig. 7I).

We found that the specificity of these interactions, i.e. their dependence on the presence of the CUP9 degron, could be restored if GST-CUP9 pulldowns with purified UBR11-1140f or purified UBR1 were carried out in the presence of a “carrier” protein such as ovalbumin, at concentrations (10-50 mg/ml) that would be expected to produce “macromolecular crowding” (Fig. 4K, lanes 4-6, compare with lanes 7 and 8; Fig. 7F, lanes 5 and 6, compare with lanes 7 and 8; Fig. 7G, lanes 9 and 10, compare with lanes 5 and 6; Fig. 7K, lanes 5 and 6, compare with lanes 7 and 8). These terms refer to volume-exclusion and related effects that recapitulate, in part, the properties of intracellular milieu, where the total protein concentration can be as high as 200-400 mg/ml (74-76).

As expected, and similarly to the effect of ovalbumin, the re-addition of fUBR1-lacking yeast extract to purified fUBR1 also restored the specificity of UBR1 binding to GST-CUP9 (Fig. 7E). We noticed that GST-CUP9 interacted not only with fUBR1 in the yeast extract but also with another protein that was present in extracts irrespective of the presence of fUBR1 (data not shown). Mass spectrometry of that protein identified it as EF1A, which functions as a translation elongation factor, a protein chaperone, and is a highly abundant protein (Ref. 77 and references therein). We employed two chromatographic steps, DEAE-Sepharose and CM-Sepharose chromatography, to purify S. cerevisiae EF1A to near homogeneity (Fig. 7H). The addition of purified EF1A to GST-CUP9 pulldowns with purified fUBR1, at the EF1A concentration of 1.2 mg/ml (a relatively low level, in comparison to minimally effective concentrations of ovalbumin), was found to restore the specificity of UBR1-CUP9 interactions. Specifically, in the presence of purified EF1A, a significant binding of purified fUBR1 to GST-CUP9 was observed only in the presence of dipeptides with destabilizing N-terminal residues (Fig. 7G, lanes 7 and 8, compare with lanes 2-6 and 9 and 10).