Abstract

Plants, fungi, and animals generate a diverse array of deterrent natural products that induce avoidance behavior in biological adversaries. The largest known chemical family of deterrents are terpenes characterized by reactive α,β-unsaturated dialdehyde moieties, including the drimane sesquiterpenes and other terpene species. Deterrent sesquiterpenes are potent activators of mammalian peripheral chemosensory neurons, causing pain and neurogenic inflammation. Despite their wide-spread synthesis and medicinal use as desensitizing analgesics, their molecular targets remain unknown. Here we show that isovelleral, a noxious fungal sesquiterpene, excites sensory neurons through activation of TPRA1, an ion channel involved in inflammatory pain signaling. TRPA1 is also activated by polygodial, a drimane sesquiterpene synthesized by plants and animals. TRPA1-deficient mice show greatly reduced nocifensive behavior in response to isovelleral, indicating that TRPA1 is the major receptor for deterrent sesquiterpenes in vivo. Isovelleral and polygodial represent the first fungal and animal small molecule agonists of nociceptive transient receptor potential channels.

Terpenes represent the largest group of natural products synthesized by plants, fungi, animals, and microorganisms (1). Although some terpenes function as hormonal messengers or as constituents of biological membranes and enzymatic cofactors, the biological functions of most of the ∼25,000 different terpenes remain to be determined (1). Recent studies investigating the biochemical interactions of plants, fungi, and animals suggest that one of the major biological roles of terpenes is to act as chemical deterrents against herbivores, fungivores, and predators, respectively (1, 2). Deterrent terpenes interact with chemosensory detection systems in target organisms to induce avoidance behavior. In animals, it has been speculated that chemodefensive terpenes could activate gustatory and olfactory pathways as well as pain-sensing neuronal pathways. Indeed, some terpenes produce a painfully pungent taste in humans, probably related to their deterrent function.

Recent research on terpene deterrents has focused on sesquiterpenes, a class of terpenes consisting of three isoprene units. One of the most intensively studied defensive sesquiterpenes is isovelleral, the pungent product of the fungus Lactarius vellereus. Isovelleral is thought to be part of a fungal chemical defense system against predators (3, 4) and is rapidly synthesized in response to injury from chemical precursors stored in the fungal laticiferous hyphae (5, 6). In behavioral tests, fungivorous mammals were strongly repelled by isovelleral (5, 6). In humans, skin contact with the fungal milky exudate often leads to painful inflammatory responses, including eczema and blistering (7, 8). Another pungent sesquiterpene is polygodial, initially isolated from the leaves of water pepper (Polygonum hydropiper) (9). Polygodial is also a major product of winter's bark (Drimys winteri), a South American medicinal tree, and horopito (Pseudowintera colorata), a medicinal plant native to New Zealand (10, 11). Leaves and barks from these plants are used for analgesic and anti-inflammatory preparations to treat dental and stomach pain and other painful conditions (12). Although initially painful, polygodial acts as an analgesic through desensitization of sensory neurons (12). Polygodial is also found in ferns (pteridophytes), bryophytes (liverworts) (13, 14), and even in animals. Studies on Mediterranean and Pacific sea slugs have shown that these animals synthesize polygodial as a chemodefensive agent to deter predatory fish (15, 16). Thus, pungent sesquiterpenes are used as chemical defense agents across plant, fungal, and animal kingdoms.

Both isovelleral and polygodial have been proposed to act on vanilloid receptors in peripheral sensory neurons to induce pungent sensations and neurogenic inflammation (17, 18). The vanilloid receptor, TRPV1, is a Ca2+-permeable transient receptor potential (TRP)3 ion channel activated by vanilloids such as capsaicin, the pungent ingredient in chili peppers. TRPV1 is specifically expressed in nociceptive chemosensory neurons and is also sensitive to acidity and noxious heat. Both isovelleral and polygodial induce Ca2+ influx into cultured sensory neurons (17, 18). Ca2+ influx was partially abolished by the vanilloid antagonist capsazepine (17, 18). In addition, isovelleral and polygodial diminished binding and changed cooperativity of the high affinity vanilloid agonist resiniferatoxin on sensory neuronal membrane preparations (17, 18). Polygodial induced bladder contraction, a process mediated by neuropeptides released from activated sensory nerve endings in the bladder wall (18). Intriguingly, capsazepine was generally ineffective in blocking this activity, whereas the TRP channel pore blocker ruthenium red almost completely blocked polygodial-induced contraction (18). In a similar fashion, isovelleral-activated relaxation of the mesenteric artery appeared to be partially independent of vanilloid receptors (19).

Surprisingly, pharmacological studies failed to detect any agonist activity of isovelleral or polygodial on cloned vanilloid receptors, including human, rat and porcine TRPV1 isoforms (20-22). On the contrary, it was found that isovelleral has TRPV1 antagonist activity, inhibiting capsaicin activation of TRPV1 at IC50 values similar to those of capsazepine and ruthenium red (20, 22). Activity of polygodial on cloned vanilloid receptors remains to be established. These observations suggested that the biological actions of isovelleral and other sesquiterpenes are mediated by unknown sensory neuronal targets different from TRPV1. The discovery of the targets of sesquiterpenes will provide important insights into the molecular mechanism of pain and deterrence induced by this large class of biological deterrents and may delineate novel approaches for the development of analgesics.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals—TRPA1-/- mice were a gift from David Julius (University of California, San Francisco). Mice were housed at an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-accredited facility in standard environmental conditions (12 h light-dark cycle and ∼23 °C). All animal procedures were approved by the Yale Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were identically matched for age (12-22 weeks) and gender, and the experimenter was blind to the genotype. Mice were genotyped as described (23).

Chemicals and Analysis—Isovelleral was purchased from either Sigma or A.G. Scientific, Inc. Polygodial was purchased from Sequoia Research Products, Ltd. Methylvinylketone was purchased from Acros Organics, and methacrolein was from Alfa Aesar. All other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma.

Cell Culture and Transfections—Adult mouse dorsal root ganglia were dissected and dissociated by a 1-h incubation in 0.28 Wünsch unit/ml Liberase Blendzyme 1 (Roche Applied Science), followed by washes with phosphate-buffered saline, trituration, and straining of debris (70 μm; Falcon). Neurons were cultured in neurobasal-A medium (Invitrogen) with B-27 supplement, 0.5 mm glutamine, and 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor (Calbiochem) on 8-well chambered coverglass or 35-mm cell culture dishes (Nunc) coated with polylysine (Sigma) and laminin (Invitrogen). HEK-293T cells for Ca2+ imaging and electrophysiology were cultured and transfected as described (24).

Ca2+ Imaging and Electrophysiology—Imaging and electrophysiological recordings were performed 16-26 h after dorsal root ganglion (DRG) dissection or transfection. For imaging, medium was replaced by modified standard Ringer's bath solution: 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.2. Cells were loaded with Fura-2/AM (10 μm, Calbiochem, CA) for 1 h and subsequently washed and imaged in standard bath solution. Ratiometric Ca2+ imaging was performed on an Olympus IX51 microscope with a Polychrome V monochromator (Till Photonics) and a PCO Cooke Sensicam QE camera and Imaging Workbench 6 imaging software (Indec). Fura-2 emission images were obtained with exposures of 0.100 ms at 340-nm and 0.100 ms at 380-nm excitation wavelengths. Intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) concentrations were derived from the F340/F380 emission ratio adjusted by the Kd of Fura-2 (238 nm) and ratiometric data at minimum and maximum [Ca2+]i (25-27). Ratiometric images were generated using ImageJ software.

For electrophysiology, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. After 12-24 h, cells were washed with extracellular solution (140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm glucose, 10 mm HEPES) and recorded. For whole cell recordings, pipette solution contained 75 mm CsCl, 70 mm CsF, 10 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES. For cell-attached recordings, bath and pipette solution contained 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm glucose, 10 mm HEPES. For inside-out recordings, pipette solution contained 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm EGTA, and bath solution contained 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm EGTA, 0.1 mm PPPi. Cell-attached and inside-out recordings were performed by forming a gigaseal using wax-coated borosilicate pipettes with the desired resistance (4-5 megaohms). Whole cell recordings were performed with a holding potential of 0 mV unless otherwise indicated. All currents were recorded with an HEKA EPC 10 patch-clamp amplifier (Instrutech, Port Washington, NY), filtered at 2.9 kHz with a 4-pole Bessel filter, and subsequently stored on a computer disk. All traces were digitally filtered at 1 kHz. Data were analyzed with HEKA Patchmaster and HEKA Fitmaster.

Pain Behavior—Mice received a 25-μl injection of 1 mm isovelleral (in 10% DMSO saline) intraplantarly into the right hind paw using a 100-μl Hamilton syringe. Responses were recorded in a clear cylinder for 5 min. Nocifensive responses were visualized by slowing the video frame speed with Media Player software (Microsoft Windows). Nocifensive responses after paw injection (licking, flicking, and lifting) were quantified and combined as “total number of behaviors.”

Statistics—For all statistical tests, a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The sums of nocifensive paw licking, flicking, and lifting responses (total number of behaviors, n = 10/group) after isovelleral treatment were compared between TRPA1-/- mice and wild-type littermates using analysis of variance or repeated measures analysis followed by post hoc analysis. The percentages of cultured neurons from TRPA1+/+ and TRPA1-/- mice responding to isovelleral or polygodial with an increase of [Ca2+]i to levels of >500 nm were compared using a two-tailed, two-sample with unequal variance, Student's t test.

RESULTS

TRPV1-independent Activation of Sensory Neurons by Isovelleral—To identify sensory neuronal targets for pungent sesquiterpenes, we studied the cellular and pharmacological effects of isovelleral on cultured murine DRG neurons by ratiometric Ca2+ imaging (Fig. 1, A-C). Isovelleral (200 μm) induced a robust increase in intracellular Ca2+ in a subpopulation of tested neurons (Fig. 1, B and C). The activity of isovelleral was abolished in Ca2+-free, EGTA-buffered medium, indicating that isovelleral initiated influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cells (supplemental Fig. 1A). We further characterized the neuronal samples by application of mustard oil (allyl isothiocyanate; 100 μm) and capsaicin (800 nm), two C-fiber-specific sensory irritants activating the Ca2+-permeable ion channels TRPA1 and TRPV1, respectively (Fig. 1, B and C). As a final stimulus, potassium chloride was added to depolarize all neurons, thus activating voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Mustard oil raised [Ca2+]i in some of the cells preactivated by isovelleral but was largely ineffective at inducing Ca2+ influx into additional neurons, indicating that these two painful agents target the same cellular population. The isovelleral- and mustard oil-responsive cellular population was 92 ± 4% identical. Capsaicin activated additional cells (Fig. 1, B and C). The cells activated by isovelleral were contained within the population of capsaicin-sensitive cells and represented 75 ± 5% of capsaicin-sensitive neurons (three fields of cultured neurons, 342 total cells analyzed). Isovelleral activated neuronal Ca2+ influx with an EC50 of 130 ± 40 μm (n = 50 ± 4 neurons/concentration, tested at nine concentrations within the range of 0-200 μm).

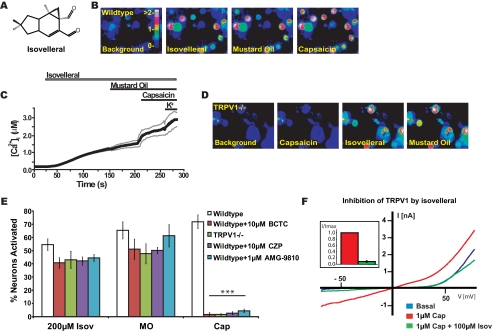

FIGURE 1.

Isovelleral-activated Ca2+ influx into cultured sensory neurons. A, structure of the pungent sesquiterpene isovelleral, the chemodefensive product of the fungus L. vellereus. B, activation of Ca2+ influx into cultured murine DRG neurons by 200 μm isovelleral as measured by fluorescent Fura-2 imaging. [Ca2+]i is represented by pseudocolors before (first panel) and 125 s after challenge with 200 μm isovelleral (second panel), followed by 100 μm mustard oil (after 50 s; third panel), and 1 μm capsaicin (after 50 s; fourth panel) at ×10 magnification. Scale bar, intracellular calcium concentration (μm). C, activation of Ca2+ influx by isovelleral into DRG neurons, plotted against time. The thick line represents the averaged [Ca2+]i in response to application of 200 μm isovelleral, followed by 100 μm mustard oil, 1 μm capsaicin, and 65 mm KCl. The thin lines represent ±S.E. Neurons (n = 342) were analyzed from three mice at ×10 magnification. D, responses of cultured DRG neurons dissociated from TRPV1-/- mice following application of 1 μm capsaicin (50 s; second panel), followed by 200 μm isovelleral (after 100 s; third panel) and 100 μm mustard oil (50 s; fourth panel). Isovelleral-induced calcium influx is retained in TRPV1-deficient sensory neurons. E, insensitivity of neuronal isovelleral-activated Ca2+ influx to pharmacological inhibition or genetic ablation of TRPV1. The bar graph shows percentages of activated neurons, in response to 200 μm isovelleral (Isov), 100 μm mustard oil (MO), and 1 μm capsaicin (Cap). The activity of agonists was tested in wild-type neurons without inhibitor (white), in the presence of the TRPV1 antagonist BCTC (10 μm; red), in TRPV1-/- neurons without inhibitor (green), and in wild-type neurons in the presence of the TRPV1 antagonists capsazepine (CZP (10 μm); purple) and AMG-9810 (1 μm; cyan). A neuron was considered to be activated when [Ca2+]i exceeded 500 nm. Values denote percentages of KCl-sensitive cells. Whereas capsaicin responsiveness was significantly reduced by antagonist and genetic ablation of TRPV1 (***, p < 0.001), isovelleral and mustard oil responsiveness remained unaffected. F, inhibition of capsaicin-activated TRPV1 currents by isovelleral. Currents from representative TRPV1-transfected HEK293t cells are shown before (blue) and after saturation of currents with 1 μm capsaicin (red). Capsaicin-activated currents were inhibited by co-application of 100 μm isovelleral (green; co-applied with capsaicin for 20 s). Currents were recorded in response to a voltage ramp (-100 mV to +100 mV for 100 ms). Inset, inward TRPV1 currents at -80 mV recorded from transfected HEK293t cells (n = 7) in the presence of capsaicin (1 μm; black) and capsaicin plus isovelleral (1 μm + 100 μm; black). Currents were normalized to the maximal capsaicin-activated current and averaged.

TRPV1, the capsaicin receptor, was proposed to be a candidate target for isovelleral in sensory neurons. We therefore examined the effects of genetic ablation and pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 on isovelleral-induced neuronal influx of Ca2+. As expected, capsaicin responsiveness of DRG neurons dissociated from TRPV1-/- mice was completely abolished (Fig. 1, D and E). In contrast, responsiveness to isovelleral was maintained in TRPV1-/- neurons (Fig. 1, D and E). Application of isovelleral to TRPV1-deficient neurons activated a similar proportion of sensory neurons and caused a similarly robust increase in intracellular Ca2+. (Fig. 1E). Sensitivity to isovelleral was also retained in wild-type neurons superfused with isovelleral in the presence of three TRPV1 antagonists, N-(4-tertiarybutylphenyl)-4-(3-chloropyridin-2-yl)tetrahydropyrazine-1(2H)-carboxamide (BCTC) (28-30), capsazepine (31), and AMG-9810 (32) (Fig. 1E). Capsazepine, reported to counteract the effects of isovelleral in vivo, was also ineffective in blocking isovelleral-induced Ca2+ influx in TRPV1-deficient neurons (supplemental Fig. 1B). Although all three antagonists abolished the effects of capsaicin, the proportion of neurons activated by isovelleral remained similar to the proportion of cells activated in the absence of TRPV1 antagonists (Fig. 1E). Finally, our patch clamp analysis of capsaicin-activated TRPV1 currents in heterologous cells confirmed earlier fluorescent imaging studies reporting an inhibitory action of isovelleral on TRPV1. Isovelleral (100 μm) robustly inhibited capsaicin (1 μm)-activated currents throughout the applied range of voltages (Fig. 1F). Only small inward TRPV1 currents remained. Capsaicin (1 μm) was transiently capable of overcoming isovelleral (100 μm) inhibition (Fig. 1F, inset, and supplemental Fig. 1C). Taken together, our initial studies suggest that TRPV1 is unlikely to be the major mediator of isovelleral-activated Ca2+ influx into cultured sensory neurons. In fact, our data confirm that isovelleral is an inhibitor of TRPV1.

Activation of TRPA1 by Isovelleral in Sensory Neurons and Heterologous Cells—To further characterize the isovelleral-activated Ca2+ influx pathway, we measured the effects of isovelleral on neuronal membrane conductance by whole cell patch clamp electrophysiology. Isovelleral activated sustained currents in 4 of 14 recorded sensory neurons (Fig. 2, A and B). The induced currents were outwardly rectifying and blocked by ruthenium red, a blocker of a subgroup of TRP ion channels (Fig. 2, A and B). In Ca2+ imaging experiments, ruthenium red also completely abolished isovelleral-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2C). These results indicated that isovelleral activated a Ca2+-permable ion channel, possibly a TRP channel, in the mustard oil-sensitive population of sensory neurons. This population is characterized by expression of TRPA1, a TRP ion channel activated by mustard oil (allyl isothiocyanate) (24, 33).

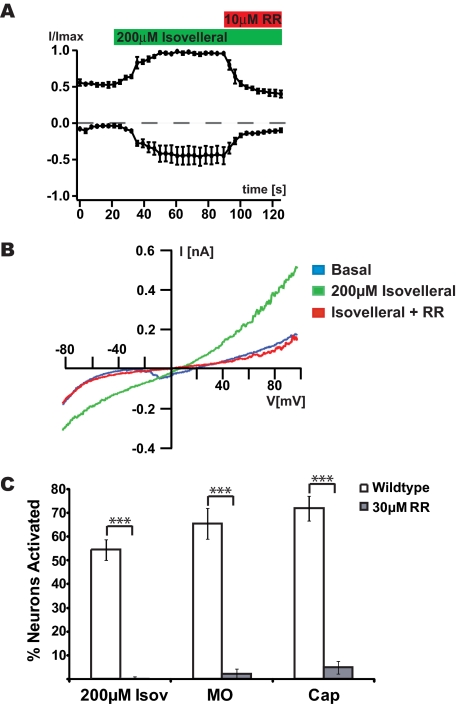

FIGURE 2.

Activation of ruthenium red-sensitive ionic currents in sensory neurons by isovelleral. A, activation of ionic currents in sensory neurons by isovelleral, as measured by whole cell patch clamp electrophysiology. Currents were measured in response to a 100-ms voltage ramp from -100 to +100 mV. Averaged normalized outward and inward currents at +60 and -60 mV, respectively, of DRG neurons (n = 3) are shown measured. 200 μm isovelleral was superfused after 20 s (green bar), and 10 μm ruthenium red (RR) after 90 s (red bar). B, representative isovelleral-activated currents in a DRG neuron. The current was measured in response to a 100-ms voltage ramp from -100 to +100 mV. Blue trace, basal current before isovelleral application; green trace, fully activated currents after 200 μm isovelleral application; red trace, ruthenium red (10 μm) block of isovelleral (200 μm)-activated current. C, percentages of DRG neurons activated by 200 μm isovelleral, 100 μm mustard oil, 1 μm capsaicin, and 65 mm KCl in the presence of 30 μm ruthenium red, a TRP channel blocker (n = 147 cells with ruthenium red; n = 342 cells without ruthenium red). A neuron was considered to be activated when [Ca2+]i exceeded 500 nm.

To investigate potential agonist activity of isovelleral on TRPA1, we examined its effects on cloned TRPA1 channels in heterologous cells by fluorescent Ca2+ imaging and patch clamp electrophysiology. Indeed, isovelleral induced robust influx of Ca2+ into HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with human (EC50 = 0.50 ± 0.13 μm) or mouse (EC50 = 2.58 ± 1.09 μm) TRPA1 cDNA, whereas vector-transfected cells were unresponsive (Fig. 3, A and B). In patch clamp recordings from hTRPA1-transfected CHO cells, isovelleral (50 μm) activated sizable currents inhibited by ruthenium red (Fig. 3C). Cell-attached single channel recordings revealed that the channels underlying isovelleral-induced currents had a conductance of 75 ± 1 picosiemens at +60 mV and 45 ± 1 picosiemens at -60 mV, similar to single channel conductances reported for TRPA1 (Fig. 3D and supplemental Fig. 1D) (34). The open single channels conductance showed outward rectification (Fig. 3E). Patch clamp recordings in the inside out configuration revealed that isovelleral was capable of activating TRPA1 channels when applied to the cytosolic side of the patch (Fig. 3F and supplemental Fig. 1E). Activity of isovelleral in the inside out configuration was retained in the absence of Ca2+ on both sides of the membrane (Fig. 3F and supplemental Fig. 1E). Agonist activity of isovelleral was unique to TRPA1, since other TRP channels, including TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3, TRPV4, and TRPM8, did not respond to isovelleral (200 μm; not shown).

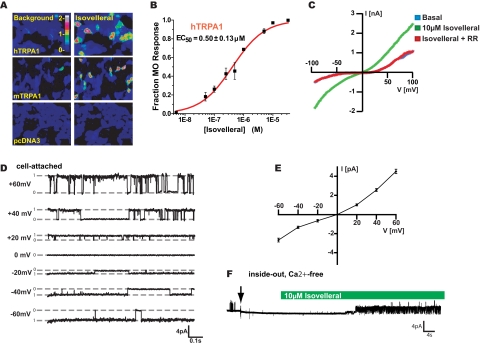

FIGURE 3.

Isovelleral activates TRPA1 channels in heterologous cells. A, isovelleral (10 μm) evokes calcium influx into hTRPA1- and mTRPA1 (30 μm isovelleral)-transfected cells, as measured by fluorescent Ca2+ imaging. Mock-transfected (pcDNA3) cells were insensitive to 30 μm isovelleral. Pseudocolors indicate [Ca2+]i in Fura-2-loaded cells. B, dose-response curve for activation of hTRPA1 by isovelleral in HEK293T cells, as measured by fluorescent Ca2+ imaging. Cells were activated with the indicated concentrations of isovelleral and then with a saturating dose of mustard oil (100 μm) (n = 45 ± 8 cells/dose). Error bars, S.E. C, representative whole cell currents recorded from a hTRPA1-transfected CHO cell. The current was measured in response to a 100-ms voltage ramp from -100 to +100 mV. Blue trace, basal current before isovelleral application; green trace, fully isovelleral (10 μm)-activated current, recorded 10 s following application of isovelleral to the bath solution; red trace, block of isovelleral (10 μm)-activated current by concomitant application of ruthenium red (10 μm). D, single channel currents recorded from a hTRPA1-transfected CHO cell in cell-attached configuration in response to 10 μm isovelleral. Currents were recorded from -60 to +60 mV in 20-mV steps. Average single channel conductances were 75 ± 1 picosiemens at +60 mV and 45 ± 1 picosiemens at -60 mV. E, open channel current-voltage relationship of isovelleral (10 μm)-activated hTRPA1 channels, recorded in cell-attached configuration as in D. Open channels show outward rectification. F, TRPA1 activation by isovelleral in the inside-out patch clamp configuration in Ca2+-free conditions. An inside-out patch, held at a depolarizing voltage of +40 mV, was pulled (arrow) from a CHO cell transiently transfected with hTRPA1 and perfused with 10 μm isovelleral (green bar). Bath and pipette solution contained 0 mm Ca2+ and 10 mm EGTA. TRPA1 single channels were activated by isovelleral in the absence of Ca2+. Recordings from three additional inside out patches showed similar effects (not shown).

Cellular and Behavioral Insensitivity of TRPA1-/- Mice to Isovelleral—To examine the role of TRPA1 in the sensory neuronal response to isovelleral, we analyzed the effects of isovelleral on neurons dissociated from TRPA1-/- mice (Fig. 4, A and B). Strikingly, we observed that responses to isovelleral were dramatically reduced in TRPA1-deficient neurons. At concentrations of isovelleral of ≤150 μm, no neuronal cellular influx of Ca2+ was observed. Only at high concentrations of isovelleral (200 μm) did we observe a residual population of isovelleral-sensitive cells (7.3 ± 1.5% of neurons, n = 363 total cells in five fields) (supplemental Fig. 2A). These cells were only activated after significant delays, and steady state [Ca2+]i remained at a much lower level than in wild-type neurons (supplemental Fig. 2, B and C). These residual responses were only blocked by substantially high concentrations of ruthenium red (40 μm) and were insensitive to capsazepine (10 μm) (supplemental Fig. 2D). Thus, TRPA1 appeared to be required for the majority of the sensory neuronal responses to isovelleral in culture.

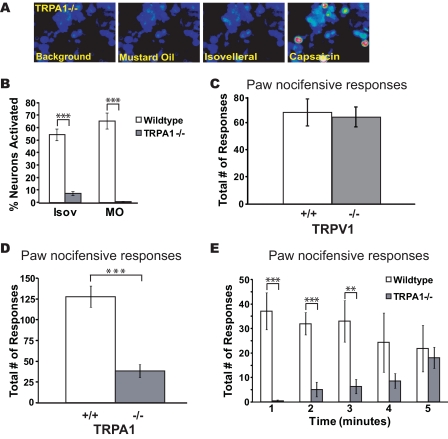

FIGURE 4.

Cellular and behavioral insensitivity to isovelleral in TRPA1-/- mice. A, responses of cultured DRG neurons from TRPA1-/- mice to 100 μm mustard oil (after 50 s; second panel), 200 μm isovelleral (after 150 s; third panel), and 1 μm capsaicin (after 50 s; fourth panel) as measured by Fura-2 imaging. TRPA1-deficient neurons failed to respond to mustard oil and isovelleral. B, percentages of cultured wild-type and TRPA1-/- DRG neurons activated by 200 μm isovelleral, 100 μm mustard oil, and 1 μm capsaicin. A neuron was considered to be activated when [Ca2+]i exceeded 500 nm. Residual isovelleral responses showed small changes in [Ca2+]i and had a delayed onset when compared with isovelleral-responsive wild-type neurons. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01. C, nocifensive responses of wild-type (+/+) and TRPV1-deficient (-/-) mice to paw injections of isovelleral. Responses (licking and lifting) were measured after intraplantar injection of 25 μl of 1 mm isovelleral solution into the hind paw. Responses were measured over a period of 5 min (n = 3 mice/genotype). Responses in wild-type and TRPV1-/- mice were indistinguishable. D, diminished nocifensive responses in TRPA1-deficient mice after paw injection with isovelleral. Nocifensive responses (licking, flicking, and lifting) were measured after intraplantar injection of 25 μl of 1 mm isovelleral solution into the right hind paw of mice over a period of 5 min. ***, p < 0.001 (analysis of variance), n = 10 mice/genotype. E, mouse nocifensive responses (licking, flicking, and lifting) after injection of isovelleral, plotted for each minute of the 5-min trial period. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; n = 10 mice/genotype. Error bars, S.E.

Our results implicate TRPA1 as the major mediator of pungency and deterrence by isovelleral. However, neuronal activation in the intact animal could occur through other pathways. To examine the roles of TRPA1 and TRPV1 in isovelleral deterrence in vivo, we compared the nocifensive response of wild-type, TRPV1-/-, and TRPA1-/- mice after injection of isovelleral into the hind paw. The activity of isovelleral in this assay had not been reported before, requiring the establishment of a dose that would induce reproducible numbers of nocifensive responses. Wild-type mice displayed immediate nocifensive behavior (paw lifts, flicks, and licks) after injection of 25 nmol of isovelleral (25 μl of 1 mm). This amount was similar to the reported amount of isovelleral required to induce nocifensive eye wiping responses in rats (17). Injection of the same volume of vehicle did not cause any nocifensive responses (not shown). Although nocifensive responses in wild-type and TRPV1-/- mice were indistinguishable, TRPA1-/- mice showed a dramatically reduced number of responses after injection (Fig. 4, C and D). Differences in pain responses in TRPA1-/- mice were particularly pronounced immediately following the injection. Although wild-type mice responded immediately and continued with a constant response frequency over the entire test period, TRPA1-/- mice showed no responses within the first minute, with occasional pain responses in the later minutes of the experiment (Fig. 4E). Thus, we show that TRPA1 is the principal mediator of isovelleral-induced pain and deterrence in vivo.

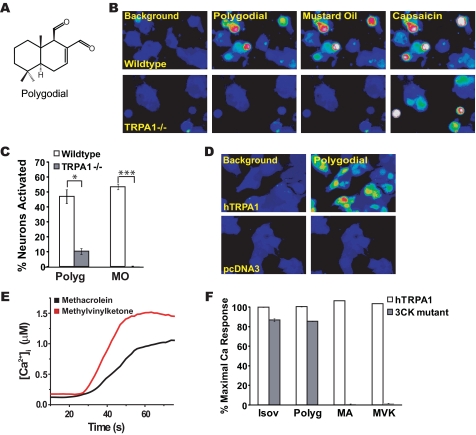

Activation of TRPA1 by Polygodial, a Drimane Sesquiterpene, and by Reactive Terpene Products—Does TRPA1 play a more general role in sesquiterpene-induced irritance, or is the interaction with sesquiterpenes limited to isovelleral only? To answer this question, we tested whether TRPA1 would be activated by the pungent sesquiterpene, polygodial (Fig. 5A). Polygodial (200 μm) robustly activated Ca2+ influx into cultured sensory neurons of wild-type mice (Fig. 5B). Again, TRPA1 appeared to be essential for this response, since the percentage of neuronal cells responding to polygodial was significantly reduced in neurons dissociated from TRPA1-/- mice. (Fig. 5, B and C). Polygodial strongly activated hTRPA1 channels expressed in HEK-293T cells, with EC50 = 400 ± 70 nm (n = 60 ± 7 cells/concentration, tested at 10 different concentrations within the range of 0-10 μm) (Fig. 5D). Again, other TRP channels with sensory roles, including TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3, TRPV4, and TRPM8, were unresponsive (not shown). Thus, TRPA1 is a receptor for both isovelleral and polygodial and, potentially, other pungent sesquiterpenes.

FIGURE 5.

TRPA1 is a receptor for polygodial and noxious terpene oxidation products. A, structure of the pungent terpene polygodial, a drimane sesquiterpene found in water pepper and other pungent plants as well as in mollusks. B, responses of DRG neurons dissociated from wild-type mice (top row) and TRPA1-/- littermates (bottom row) to 200 μm polygodial, 100 μm mustard oil, and 1 μm capsaicin, as measured by Fura-2 imaging. TRPA1-/- neurons fail to show similar increases in [Ca2+]i after exposure to polygodial but are activated by capsaicin. C, percentages of cultured wild-type and TRPA1-/- DRG neurons activated by 200 μm polygodial (Polyg), 100 μm mustard oil, and 1 μm capsaicin. A neuron was considered to be activated when [Ca2+]i exceeded 500 nm.*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. D, polygodial (10 μm) evokes calcium influx into hTRPA1-transfected cells. Cells transfected with vector alone are insensitive to 30 μm polygodial. Pseudocolor images of Fura-2-loaded cells are shown. E, trace showing calcium responses in hTRPA1-transfected cells to 100 μm methylvinylketone (red) and 100 μm methacrolein (black) as a function of time. F, requirement of covalent agonist acceptor sites in TRPA1 for activation by 30 μm isovelleral (Isov), 30 μm polygodial (Polyg), 330 μm methacrolein (MA), and 330 μm methylvinylketone (MVK). In the 3CK mutant, the amino acid residues Cys619, Cys639, Cys663, and Lys708 have been substituted with serine residues. Mutant-expressing cells were superfused with saturating doses of the compounds for 80 s, followed by saturating doses of the TRPA1 agonists carvacrol (250 μm) or 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (250 μm). TRPA1 activity was measured by Fura-2 imaging. White bars, hTRPA1-transfected cells; gray bars, cells transfected with the 3CK mutant.

How do pungent sesquiterpenes activate TRPA1? Recent studies indicated that TRPA1 is a receptor for a wide range of noxious electrophilic agents, activating the channel through covalent modification of cysteine and lysine residues in the TRPA1 protein (35, 36). Intriguingly, both isovelleral and polygodial contain α,β-unsaturated dialdehyde moieties potentially capable of forming Michael adducts or Schiff bases with reactive amino acid residues (37). These moieties are similar to α,β-unsaturated aldehyde moieties found in TRPA1 agonists, such as acrolein, cinnamic aldehyde, and 4-hydroxynonenal (23, 33, 38, 39). TRPA1 is rendered insensitive to these agonists when specific covalent acceptor sites are substituted with nonreactive residues (35, 36). We tested agonist activity of isovelleral and polygodial on a TRPA1 mutant with substitutions of four potential acceptor sites (Cys619, Cys639, Cys663, and Lys708). This mutant is insensitive to mustard oil, acrolein, and 4-hydroxynonenal (35, 38) (Fig. 5, E and F). As a positive control, we used the nonreactive TRPA1 agonist, carvacrol (40). Strikingly, we found that both isovelleral and polygodial were nearly as potent as carvacrol in activating the combined mutant. In contrast, activity of other α,β-unsaturated aldehydes was clearly abolished. Both methyl-vinylketone and methacrolein, two potent activators of TRPA1, did not activate the mutant (Fig. 5, E and F). These two chemicals, structurally similar to acrolein, are highly noxious environmental toxicants produced by ozone oxidation of biogenic isoprene in photochemical smog and are also enriched in tobacco smoke (41) (supplemental Fig. 2E). These data suggest that dialdehyde sesquiterpenes activate TRPA1 through a mechanism different from small reactive unsaturated aldehydes.

DISCUSSION

With polygodial, produced by marine mollusks and plants, and isovelleral, a fungal natural product, we identified the first pain-inducing small molecule TRP channel agonists of animal and fungal origin. The experiments described above demonstrate that TRPA1 is the major sensory neuronal target for these, and potentially other, pungent sesquiterpene deterrents. This discovery has great significance for the understanding of the chemical interactions of fungi, plants, and marine life with their biological adversaries. Both polygodial and isovelleral robustly activate Ca2+ influx and cationic currents through TRPA1 channels expressed in primary sensory neurons and heterologous cells. In behavioral experiments, we show that TRPA1 is essential for isovelleral-induced pain responses in vivo.

TRPA1 was initially identified as a sensor for cold temperature in peripheral sensory neurons, a role that is currently debated (42-44). Subsequent studies found that TRPA1 is a receptor for plant-derived noxious deterrents, including isothiocyanates, the pungent ingredients in mustard, wasabi, and horseradish, and thiosulfinates in garlic and onions (24, 33, 45, 46). TRPA1 is expressed in a subset of sensory neurons, giving rise to peripheral chemosensory C-fibers (24, 34, 42), a neuronal population known to respond to pungent sesquiterpenes (17, 18).

Intriguingly, both isovelleral and polygodial contain unsaturated dialdehyde moieties that proved to be essential for their pungency and animal-deterrent activity in earlier studies (47-49). Unsaturated aldehydes can react with cysteine, histidine, and lysine residues in proteins by forming Michael adducts or Schiff bases (37). Recent mutagenesis studies identified candidate residues in TRPA1 serving as potential reactive irritant acceptor sites to activate the channel (35, 36). Although mutations at these sites abolished sensitivity of TRPA1 to acrolein (35) and to methacrolein and methyl vinylketone, three simple and highly reactive unsaturated aldehydes, we found that the activity of isovelleral and polygodial was preserved. These results indicate that structural or reactive constraints in unsaturated dialdehyde group-containing sesquiterpenes may direct the agonist to sites different from those targeted by reactive small agonists, such as mustard oil or acrolein. Our inside-out patch clamp experiments suggest that isovelleral activates TRPA1 in a membrane-delimited fashion. Moreover, isovelleral activation of TRPA1 was independent of extracellular and intracellular Ca2+, suggesting a direct action on the channel.

TRPA1 agonist potencies may also depend on the cellular context. Although membrane composition and differential expression of transport systems may affect membrane permeability of terpenes, cellular redox systems may buffer reactive TRPA1 ligands to various degrees. In addition, cell type-specific protein interaction partners and signaling mechanisms may affect agonist access, the structure of interaction sites, and the gating mechanism of TRPA1. Effects such as these may explain the variations in potencies of sesquiterpenes in primary neurons and heterologous cells. Similar differences have been described for other TRPA1 agonists (45).

Our data also demonstrate that the vanilloid receptor, TRPV1, previously implicated in pain-inducing sesquiterpene actions, is not required to establish neuronal sensitivity to these agents. Sensory neurons from mice genetically engineered to be deficient in TRPV1 retained sensitivity to isovelleral, both in cellular and behavioral tests. Moreover, three different TRPV1 antagonists, BCTC, capsazepine, and AMG-9810, failed to inhibit neuronal activation by isovelleral. Our data confirm earlier observations of TRPV1 antagonist activity of isovelleral (20, 22). Thus, isovelleral may be a TRPV1 ligand, albeit with inhibitory actions, but capable of replacing radiolabeled resiniferatoxin, a high affinity TRPV1 ligand, from sensory neuronal membrane preparations (17). Our data do not sufficiently explain the partial inhibitory action of capsazepine on isovelleral- or polygodial-induced physiological responses observed in previous studies. In our hands, capsazepine failed to inhibit isovelleral- and polygodial-induced activation of cultured neurons and cloned TRPA1 channels. Recent studies have shown that capsazepine is less specific and less potent than the high affinity TRPV1 antagonists BCTC and AMG-9810. Capsazepine may inhibit other neuronal targets in addition to TRPV1, including nicotinic receptors and potassium channels, thereby blocking neuronal activity (50).

Although TRPA1 is likely to mediate most of the specific effects of unsaturated dialdehyde terpenes in sensory neurons, unsaturated aldehydes have known cytotoxic effects, disrupting cellular integrity, signaling, and metabolism. These effects may explain the residual sensitivity of TRPA1-/- mice to isovelleral in the paw injection assay and the presence of a small number of TRPA1-/- neurons responding to exceedingly high concentrations of isovelleral and polygodial in our imaging assays. Alternatively, sensory neurons may express additional low affinity sesquiterpene receptors. Residual responses to isovelleral in TRPA1-deficient neurons were delayed and less robust than responses elicited in wild-type neurons. Since other known sensory TRP channels were unresponsive to isovelleral, these responses are unlikely to be mediated by this class of receptors. Residual responses could be blocked by extremely high concentrations of ruthenium red (40 μm). At these concentrations, traces of ruthenium red may cross the cellular membrane and block release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores triggered through specific or nonspecific cytotoxic effects of isovelleral.

Because fungi produce a large variety of pungent isovelleral-related sesquiterpenes, it can be expected that additional fungal TRPA1 agonists will be identified in the future (supplemental Fig. 3, A-C) (17). Plants and animals synthesize a large variety of additional polygodial-related pungent sesquiterpenes that may also serve as TRPA1 agonist. These compounds share the basic architecture of the terpene drimane, initially detected in winter's bark (D. winteri) (51) (supplemental Fig. 3D). Pungent drimane sesquiterpenes include drimanial, warburganal, ugandensidial, and muzigadial, found in the bark of East African Warburgia trees, used for medicinal purposes and as a spice (supplemental Fig. 3, E-I), and sacculatal, produced by ferns and liverworts (supplemental Fig. 3J) (48). TRPA1 agonist activity may not be restricted to isovelleral-related and drimane sesquiterpenes. Currently, more than 80 different terpenes carrying α,β-unsaturated dialdehyde moieties are known, and many more remain to be identified (52). Examples include miogadial, the pungent ingredient in the flower buds of myoga, a Japanese spice (53), and ancistrodial, a terpene isolated from the defensive secretion of soldiers of the West African termite species Ancistrotermes cavithorax (54) (supplemental Fig. 3, K and L). Plant- and insect-derived defensive dialdehyde terpenes may target insect TRPA channels or TRP channels such as the painless gene product in Drosophila melanogaster, an established target of plant defensive agents (55). The synthesis of specific subsets of dialdehyde terpenes may allow terpene-producing species to target TRP channels in predatory animal species but avoid the deterrence of beneficial species, thereby establishing the mechanism of directed deterrence documented for other biological deterrents, such as capsaicin (56).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to David Julius for TRPA1-/- mice and to Jaime Garcia-Anoveros for mouse TRPA1 cDNA.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIEHS, Outstanding New Environmental Scientists (ONES) program Grant ES015056 (to S. E. J.) and NIEHS Predoctoral Fellowship 1F31ES015932 (to J. E.). This work was also supported by Connecticut Department of Public Health Grant 2007-0161 BIOMED (to S. E.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1-3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TRP, transient receptor potential; BCTC, N-(4-tertiarybutylphenyl)-4-(3-chloropyridin-2-yl)tetrahydropyrazine-1(2H)-carboxamide; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary.

References

- 1.Gershenzon, J., and Dudareva, N. (2007) Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 408-414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langenheim, J. H. (1994) J. Chem. Ecol. 20 1223-1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.List, P. H., and Hackenberg, H. (1969) Arch. Pharm. 302 125-143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magnusson, G., Thoren, S., and Wickberg, B. (1972) Tetrahedron Lett. 13 1105-1108 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camazine, S. M., Resch, J. F., Eisner, T., and Meinwald, J. (1983) J. Chem. Ecol. 9 1439-1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camazine, S., and Lupo, A. T., Jr. (1984) Mycologia 76 355-358 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponhold, J. (1942) Arch. Dermatol. Res. 182 732-739 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponhold, J. (1944) Arch. Toxicol. 13 33-36 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes, C. S., and Loder, J. W. (1962) Aust. J. Chem. 15 322-327 [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCallion, R. F., Cole, A. L., Walker, J. R., Blunt, J. W., and Munro, M. H. (1982) Planta Med. 44 134-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cechinel Filho, V., Schlemper, V., Santos, A. R., Pinheiro, T. R., Yunes, R. A., Mendes, G. L., Calixto, J. B., and Delle Monache, F. (1998) J. Ethnopharmacol. 62 223-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andre, E., Ferreira, J., Malheiros, A., Yunes, R. A., and Calixto, J. B. (2004) Neuropharmacology 46 590-597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asakawa, Y., Toyota, M., Oiso, Y., and Braggins, J. E. (2001) Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 49 1380-1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Socolsky, C., Muruaga, N., and Bardón, A. (2005) Chem. Biodiversity 2 1105-1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cimino, G., De Rosa, S., De Stefano, S., Sodano, G., and Villani, G. (1983) Science 219 1237-1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long, J. D., and Hay, M. E. (2006) Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 307 199-208 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szallasi, A., Jonassohn, M., Acs, G., Biro, T., Acs, P., Blumberg, P. M., and Sterner, O. (1996) Br. J. Pharmacol. 119 283-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andre, E., Campi, B., Trevisani, M., Ferreira, J., Malheiros, A., Yunes, R. A., Calixto, J. B., and Geppetti, P. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 1248-1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralevic, V., Jerman, J. C., Brough, S. J., Davis, J. B., Egerton, J., and Smart, D. (2003) Biochem. Pharmacol. 65 143-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jerman, J. C., Brough, S. J., Prinjha, R., Harries, M. H., Davis, J. B., and Smart, D. (2000) Br. J. Pharmacol. 130 916-922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohta, T., Komatsu, R., Imagawa, T., Otsuguro, K., and Ito, S. (2005) Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 173-187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smart, D., Jerman, J. C., Gunthorpe, M. J., Brough, S. J., Ranson, J., Cairns, W., Hayes, P. D., Randall, A. D., and Davis, J. B. (2001) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 417 51-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bautista, D. M., Jordt, S. E., Nikai, T., Tsuruda, P. R., Read, A. J., Poblete, J., Yamoah, E. N., Basbaum, A. I., and Julius, D. (2006) Cell 124 1269-1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordt, S. E., Bautista, D. M., Chuang, H. H., McKemy, D. D., Zygmunt, P. M., Hogestatt, E. D., Meng, I. D., and Julius, D. (2004) Nature 427 260-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grynkiewicz, G., Poenie, M., and Tsien, R. Y. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260 3440-3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao, J. P. (1994) Methods Cell Biol. 40 155-181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou, Z., and Neher, E. (1993) J. Physiol. 469 245-273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrendt, H. J., Germann, T., Gillen, C., Hatt, H., and Jostock, R. (2004) Br. J. Pharmacol. 141 737-745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pomonis, J. D., Harrison, J. E., Mark, L., Bristol, D. R., Valenzano, K. J., and Walker, K. (2003) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306 387-393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenzano, K. J., Grant, E. R., Wu, G., Hachicha, M., Schmid, L., Tafesse, L., Sun, Q., Rotshteyn, Y., Francis, J., Limberis, J., Malik, S., Whittemore, E. R., and Hodges, D. (2003) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306 377-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bevan, S., Hothi, S., Hughes, G., James, I. F., Rang, H. P., Shah, K., Walpole, C. S., and Yeats, J. C. (1992) Br. J. Pharmacol. 107 544-552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gavva, N. R., Tamir, R., Qu, Y., Klionsky, L., Zhang, T. J., Immke, D., Wang, J., Zhu, D., Vanderah, T. W., Porreca, F., Doherty, E. M., Norman, M. H., Wild, K. D., Bannon, A. W., Louis, J. C., and Treanor, J. J. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313 474-484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandell, M., Story, G. M., Hwang, S. W., Viswanath, V., Eid, S. R., Petrus, M. J., Earley, T. J., and Patapoutian, A. (2004) Neuron 41 849-857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagata, K., Duggan, A., Kumar, G., and Garcia-Anoveros, J. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25 4052-4061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinman, A., Chuang, H. H., Bautista, D. M., and Julius, D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 19564-19568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macpherson, L. J., Dubin, A. E., Evans, M. J., Marr, F., Schultz, P. G., Cravatt, B. F., and Patapoutian, A. (2007) Nature 445 541-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishii, T., Yamada, T., Mori, T., Kumazawa, S., Uchida, K., and Nakayama, T. (2007) Free. Radic. Res. 41 1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trevisani, M., Siemens, J., Materazzi, S., Bautista, D. M., Nassini, R., Campi, B., Imamachi, N., Andre, E., Patacchini, R., Cottrell, G. S., Gatti, R., Basbaum, A. I., Bunnett, N. W., Julius, D., and Geppetti, P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 13519-13524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macpherson, L. J., Xiao, B., Kwan, K. Y., Petrus, M. J., Dubin, A. E., Hwang, S., Cravatt, B., Corey, D. P., and Patapoutian, A. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27 11412-11415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu, H., Delling, M., Jun, J. C., and Clapham, D. E. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 9 628-635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkins, C. K., Clausen, P. A., Wolkoff, P., Larsen, S. T., Hammer, M., Larsen, K., Hansen, V., and Nielsen, G. D. (2001) Environ. Health Perspect. 109 937-941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Story, G. M., Peier, A. M., Reeve, A. J., Eid, S. R., Mosbacher, J., Hricik, T. R., Earley, T. J., Hergarden, A. C., Andersson, D. A., Hwang, S. W., McIntyre, P., Jegla, T., Bevan, S., and Patapoutian, A. (2003) Cell 112 819-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKemy, D. D., Neuhausser, W. M., and Julius, D. (2002) Nature 416 52-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Story, G. M., and Gereau, R. W. t. (2006) Neuron 50 177-180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bautista, D. M., Movahed, P., Hinman, A., Axelsson, H. E., Sterner, O., Hogestatt, E. D., Julius, D., Jordt, S. E., and Zygmunt, P. M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 12248-12252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macpherson, L. J., Geierstanger, B. H., Viswanath, V., Bandell, M., Eid, S. R., Hwang, S., and Patapoutian, A. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15 929-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubo, I., and Ganjian, I. (1981) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 37 1063-1064 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kubo, I., Lee, Y., Pettei, M., Pilkiewicz, F., and Nakanishi, K. (1976) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1013-1014

- 49.Szallasi, A., Biro, T., Modarres, S., Garlaschelli, L., Petersen, M., Klusch, A., Vidari, G., Jonassohn, M., De Rosa, S., Sterner, O., Blumberg, P. M., and Krause, J. E. (1998) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 356 81-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu, L., and Simon, S. A. (1997) Neurosci. Lett. 228 29-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansen, B. J. M., and de Groot, A. (2004) Nat. Prod. Rep. 21 449-477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jonassohn, M. (1996) Sesquiterpenoid Unsaturated Aldehydes, Ph.D. thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

- 53.Abe, M., Ozawa, Y., Uda, Y., Yamada, Y., Morimitsu, Y., Nakamura, Y., and Osawa, T. (2002) Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66 2698-2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker, R., Briner, P. H., and Evans, D. A. (1978) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 410-411

- 55.Al-Anzi, B., Tracey, W. D., Jr., and Benzer, S. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16 1034-1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jordt, S. E., and Julius, D. (2002) Cell 108 421-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.