Abstract

The purpose of this study was to report the operative findings in patients who underwent a secondary operation for cubital tunnel syndrome. A chart review was performed of 100 patients who had undergone a secondary operation for cubital tunnel syndrome by one surgeon. The mean age was 48 years (standard deviation 13.5 years). The most common complaint after primary surgery was increased symptoms in the ulnar nerve distribution (n = 55) and pain in the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve distribution (n = 55). The most common operative findings included a medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve neuroma (n = 73) and a distal kink of the ulnar nerve (n = 57). This kink was noted as the nerve moved from its transposed position anterior to the medical epicondyle to its native position within the flexor carpi ulnaris. This study suggests that during primary surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome care should be given to avoid injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, distal kinking of the ulnar nerve with transposition and pressure on the transposed nerve by the fascial flaps or tendinous bands.

Keywords: Cubital tunnel syndrome, Surgery, Reoperation

Introduction

Compression of the ulnar nerve at the region of the cubital tunnel can result in motor and sensory dysfunction of the hand. With failure of conservative management, surgical intervention is usually the treatment recommended. A number of surgical procedures have been described for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome ranging from simple decompression, medial epicondylectomy to anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve with placement of the nerve in a subcutaneous, submuscular or transmuscular position [1, 2, 4, 9–13, 15, 19–25, 28, 29, 31]. Varying patient outcomes have been reported using different surgical procedures. In some cases, regardless of the surgical procedure performed, operative intervention may fail to resolve patient symptoms or may cause new symptoms including pain, paraesthesia, and numbness in the posterior elbow incision region and/or in the ulnar nerve distribution in the hand. Reoperation is often recommended for patients with persistent postoperative symptoms [3, 8].

This study reports the operative findings of patients who underwent secondary surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome.

Material and Methods

Patient Selection and Procedure

After approval by the institutional Human Studies Committee, a chart review was performed of 100 patients who had undergone secondary surgical treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome. All patients were referred for evaluation and treatment after primary surgery of the ulnar nerve. All secondary surgeries (an anterior transmuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve with myofascial lengthening of the flexor/pronator muscle mass [15]) were performed between 1995 and 2001 by one surgeon (S.E.M.) who had not performed any of the primary surgeries on these patients. Data collected from the chart included preoperative complaints, operative notes, and patient demographics.

Results

There were 100 patients, 41 women and 59 men, with a mean age of 48 years (SD 13.5 years).

The primary surgery performed in 33 cases was a subcutaneous transposition of the ulnar nerve, in 28 an ulnar nerve decompression, in 27 a submuscular transposition, in six a medial epicondylectomy, and in four cases an intramuscular transposition. In two cases, the primary operative procedure was not recorded.

After the primary surgery, reported patient symptoms included increased ulnar nerve symptoms after surgery (n = 55), pain in the distribution of the medial antebrachial cutaneous (MABC) nerve (n = 55), pain in the ulnar nerve distribution (n = 48), persistent symptoms in the ulnar nerve distribution (n = 28), and recurrent symptoms in the ulnar nerve distribution (n = 17).

Operative Findings

In the patients who had an ulnar nerve decompression primarily, the nerve was found behind the medial epicondyle in 11 cases and directly on the medial epicondyle in five cases. With subcutaneous transposition, the ulnar nerve was most frequently found directly on the medial epicondyle. In the submuscular transposition, the nerve was found just anterior to the medial epicondyle (Table 1). In 15 cases, the location of the ulnar nerve after the primary surgery was not described in the operative note.

Table 1.

Location of the ulnar nerve after primary surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome.

| Primary Surgery (Number of Patients) | Location of Ulnar Nerve (Number of Patients) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior to the Medial Epicondyle | On the Medial Epicondyle | Behind the Medial Epicondyle | |

| Medial epicondylectomy (6) | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Decompression (28) | 0 | 5 | 11 |

| Submuscular transposition (27) | 19 | 9 | 0 |

| Subcutaneous transposition (33) | 2 | 29 | 1 |

| Intramuscular transposition (4) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

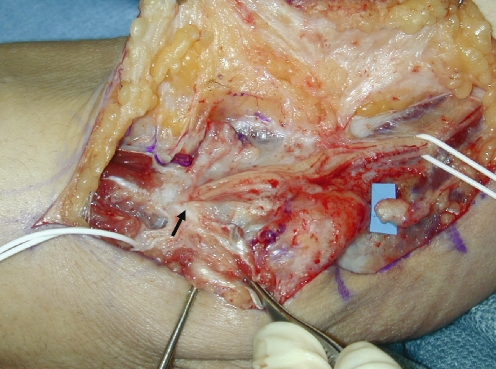

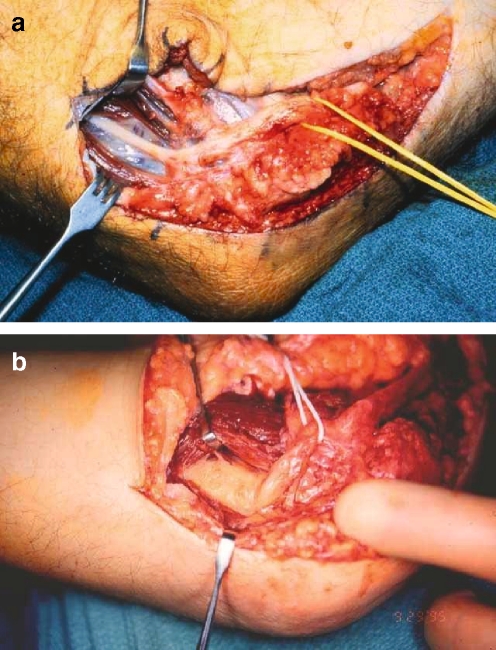

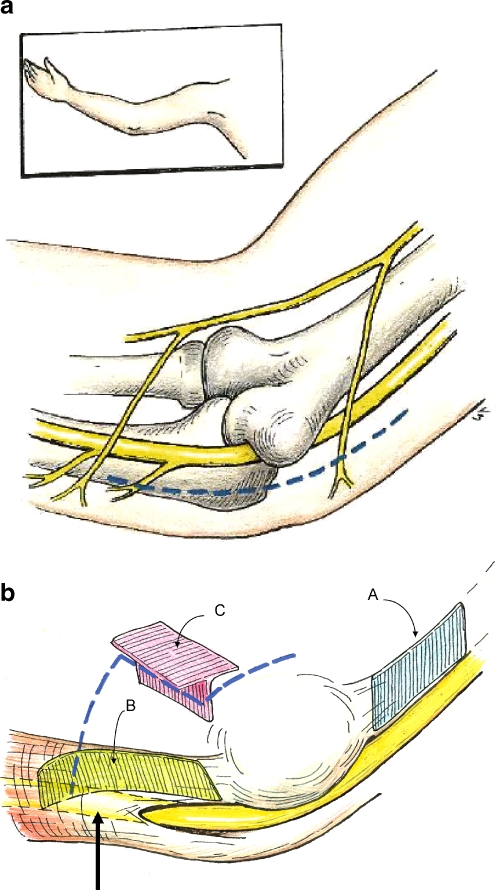

A MABC neuroma was identified in 73 cases and a direct injury to the ulnar nerve was seen in one case (Fig. 1). Compression on the ulnar nerve was seen with a proximal kink on the ulnar nerve in 28 cases and with a distal kink in 57 cases (Fig. 2). The medial intermuscular septum was identified in 39 cases. Tendinous bands within the flexor/pronator muscle origin that were sharply compressing the nerves were seen in 30 cases and a fascial flap, which was kinking and compressing the ulnar nerve, was noted in five cases (Table 2).

Figure 1.

This patient has a neuroma of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (visibility background). The previous Learmonth submuscular procedure had compressed the nerve along its length and the distal entrapment point is obvious (arrow).

Figure 2.

(a) This patient had previously had a subcutaneous transposition and the distal kinking on the nerve is apparent. (b) The thin fascia that overlies the ulnar nerve as it courses distally between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris is compressing this ulnar nerve and causing a distal kink.

Table 2.

Potential reasons for development of cubital tunnel syndrome.

| Reasons | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Compression by the tendinous leading edge of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle (Osborne’s band) |

| 2 | Superficial location of the nerve in cubital tunnel |

| 3 | Increased tension on the nerve with elbow flexion |

| 4 | Subluxation of the ulnar nerve and/or triceps muscle |

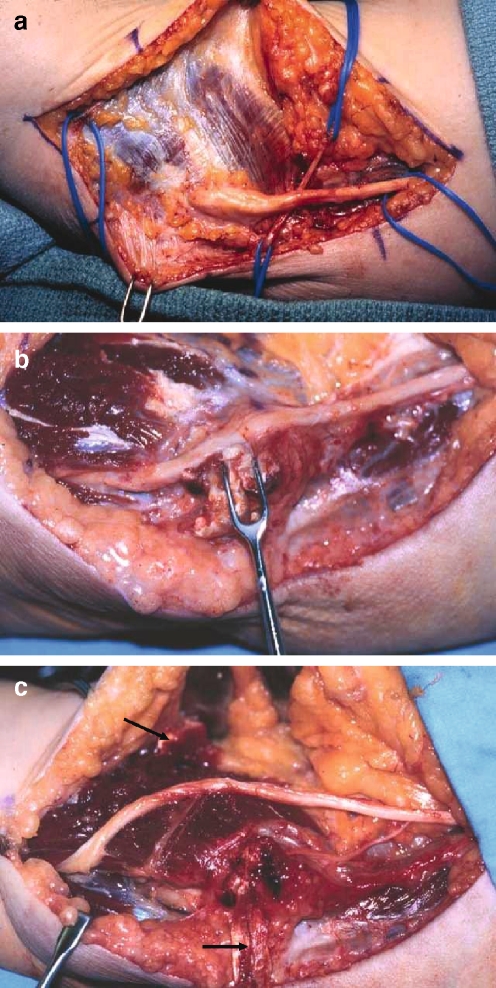

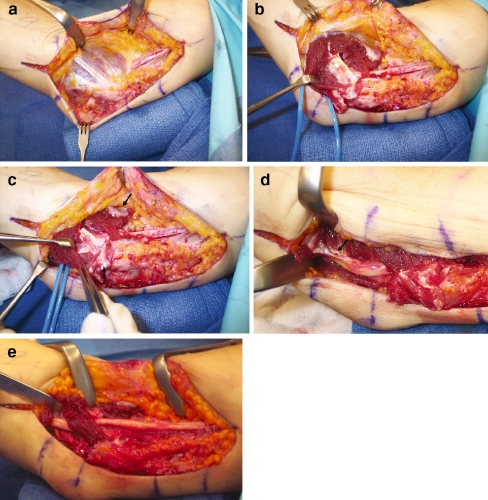

The surgical management of the ulnar nerve involved first identifying the ulnar nerve proximally (Fig. 3). The original incision was extended, and any remnant of the medial intermuscular septum was palpated. This allowed for easy identification of the ulnar nerve located just below the septum. The ulnar nerve was then followed into the area of the previous surgery. The nerve was often encased in dense scar tissue in the region of the previous surgery and in these cases the ulnar nerve was then identified distal to the area of the previous surgery between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and then followed proximally. The surgical dissection then proceeded from proximal to distal and distal to proximal, slowly going through the area of previous surgery to decompress the ulnar nerve. Because significant scarring was found around the nerve in most cases, care was taken to follow the course of the ulnar nerve and not to become “distracted” by the MABC nerve and potentially injure the ulnar nerve. Only a minimal neurolysis of the ulnar nerve was performed because of concern that the normal, robust, intrinsic blood flow to the ulnar nerve in these secondary surgical cases may be compromised and may have shifted more toward a dependency on the extrinsic blood flow [17]. All points that kinked the nerve proximally and distally and all compression points above the nerve were removed. If the patient had previously had a procedure other than a Learmonth procedure, then fascial flaps were created similar to our primary transposition procedure [15] so that they could be closed very loosely without tension over the ulnar nerve [16]. However, if the patient had previously had a traditional Learmonth submuscular transposition, then the soft muscle above the nerve could frequently be left intact, but all the intramuscular tendinous bands around the nerve were removed (Fig. 4). The treatment of MABC neuromas involved identifying the two branches of the MABC nerve on either side of the basilic vein proximal to the previous surgical site and after these nerves distally. If a neuroma was identified, it was excised and the proximal end of the MABC nerve cauterized with microbipolar cautery. This cauterization technique “caps” the end of the nerve to assist in the prevention of nerve regeneration. The nerve was then transposed proximally, well away from the overlying skin and scar, into the region of the triceps muscle and under no tension.

Figure 3.

(a) This patient had previously had a submuscular transposition; the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve can be seen to be going “under” the ulnar nerve, suggesting that it has been previously injured. (b) Distally, the skin hook retractor reflects the tendinous bands that markedly compressed the ulnar nerve. (c) All the tendinous bands within the flexor pronator muscle origin that would compress the ulnar nerve have been excised. Care has been taken to make sure there is no new compression point anywhere proximally or distally along the nerve and the nerve lies in a soft muscle bed. Fascial flaps (arrows) will be closed very loosely over the ulnar nerve and early range of movement will be initiated.

Figure 4.

(A) This patient has had a previous right Learmonth submuscular transposition. The ulnar nerve is seen proximally coursing under the pronotor flexor mass and anterior to the medial epicondyle in its transposed location. (B) The surgeon has retracted the soft flexor pronator muscle to identify the tendinous fascia (corresponding to “C” in Fig. 5B), which remains after the primary surgery. This intramuscular tendinous fascia is compressing the ulnar nerve. (C) The fascial flaps have been designed to be closed loosely over the ulnar nerve (arrows); however, they will not be needed as some muscle has been maintained above the ulnar nerve to serve as a method of not allowing the nerve to sublux back into the ulnar groove. The tendinous bands overlying the nerve will be removed and a limited neurolysis will be performed. (D) The tendinous fascia between the ulnar innervated flexor carpi ulnaris and the median innervated muscles is markedly kinking the nerve distally (arrow) and will be removed. This tendinous fascia would correspond to “B” in Fig. 5B. (E) At the conclusion of the procedure, the nerve lies in a straight location with no compression and no kinking of the nerve either proximally or distally.

At 2 days after surgery, the bulky dressing, Jackson–Pratt drain and Bupivacaine infusion pump was removed. A standard sling was used at night to limit elbow extension, which provided comfort while sleeping. The patient was instructed in range of motion exercises for the fingers, wrist forearm, elbow, and shoulder. The most difficult movement to regain was full forearm supination with full elbow extension. Therefore, initially patients were instructed in elbow extension with the forearm in pronation and when the patient was able to achieve full forearm supination with the elbow flexed at 90°, then the elbow was extended to regain a full range of motion at the forearm and elbow. The patient was restricted from heavy lifting for 1 month after surgery. Patients who did not regain full active range of motion within the first 3 weeks after surgery were referred for more formal therapy. With the return of full range of motion, strengthening exercises were instituted 4 weeks after surgery. Patients were allowed full activity and return to work without restrictions 8 weeks after surgery (Table 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative management after surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome.

| Postoperative Time | Management |

|---|---|

| Days 2–3 | Bulky dressing, Jackson–Pratt drain and bupivacaine pump removed. Instructed in range of motion exercises for finger, wrist, forearm, elbow and shoulder. Caution against heavy lifting and full forearm supination with elbow extension. Wear sling at night and if necessary, periodically during day for comfort. |

| 1 week | Continue with range of motion exercises. Expect full hand, wrist and shoulder range of motion but may have restriction of full forearm supination with full elbow extension. Continue with sling at night until patient achieves full range of motion. Massage and desensitization of incision. |

| 3 weeks | Expect full range of motion by 3 to 4 weeks and emphasis to continue stretching into full forearm supination with full elbow extension. Patients who do not achieve full range of motion are referred for therapy. |

| 4 weeks | With full range of motion, begin strengthening exercises and increase activity as tolerated. |

| 8 weeks | Return to full activity with no restrictions. |

Discussion

In patients with unresolved symptoms after primary surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome, the results of this study suggest that injury to the MABC nerve and increased ulnar nerve symptoms are common problems.

Even with excellent surgical treatment and decompression of the ulnar nerve, injury to the MABC nerve can compromise patient outcome after cubital tunnel surgery [6, 27]. The MABC nerve provides sensory innervation to the medial aspect of the arm and this may result in a range of symptoms from complete numbness to painful hyperalgesia. The MABC nerve is a branch of the medial cord or lower trunk of the brachial plexus [18, 26]. In the cadaveric study by Masear et al. [18], the nerve was found to branch off of the medial cord in 78% of cases and the lower trunk in 22% of cases. The MABC nerve then proceeds distally with the basilic vein and then in the distal arm, it divides into the anterior and posterior branches. Masear et al. [18] reported that in 92% of cases the branching occurred between 7 and 22 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus. The anterior branch crosses the elbow about 2 to 3 cm anterolateral to the epicondyle [18]. The majority of the posterior branches cross proximal to the epicondyle, although these branches were found between 6 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle to 4 cm distal to the epicondyle. Lowe and Mackinnon [14] noted that the MABC nerve consistently crossed the incision 3.5 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. The proximal branch usually ran with the septum and crossed the incision 1.5 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve generally will cross the incision 3.5 cm distal to the medial epicondyle and 1.5 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle. The distal crossing point is extraordinarily consistent. Proximally, the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve can travel with the medial intermuscular septum. (B) Surgeons should envision not just the proximal medial intermuscular septum (A) as a potential point of compression with an anterior transposition, but also a very similar fascial septum between the ulnar-innervated flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and the median-innervated flexor pronator muscle origin (B). It is this distal fascia that becomes the significant compression issue with transposition of the ulnar nerve. Also, there is very thin fascia overlying the ulnar nerve itself in its location distally between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle that can also kink and compress the nerve with a very sharp edge as the nerve is moved into its transposition location (arrow). Surgeons doing trans- or intermuscular transposition should also remove the fascial plate that is T-shaped in origin and located within the flexor/pronator muscle origin.

Sarris et al. [27] evaluated 20 patients with persistent medial elbow pain after surgery for cubital tunnel surgery and found that 65% had abnormalities of the medial cutaneous nerve with 40% presenting with a neuroma. In our present study, we found that 73% of the patients had an MABC neuroma.

Sensory and/or motor dysfunction in the distribution of the ulnar nerve can result from incomplete release of the ulnar nerve or kinking of the nerve with anterior transposition. Because of residual compression on the ulnar nerve or the creation of a new compression point with the transposition, patients may complain of continued postoperative symptoms or recurrent symptoms in the sensory distribution of the ulnar nerve. Filippi et al. [7] reported on 22 patients after reoperation for ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow and found that the cause of continued or recurrent symptoms was perineurial fibrosis, adhesion of the ulnar nerve to the medial epicondyle and incomplete excision of the medial intermuscular septum. Similarly, we found that the intermuscular septum was not excised and present in 39 cases. Gabel and Amadio [8] reported that the ulnar nerve was reportedly compressed at several levels at the primary surgery and recommended all compressive sites must be released for successful patient outcome.

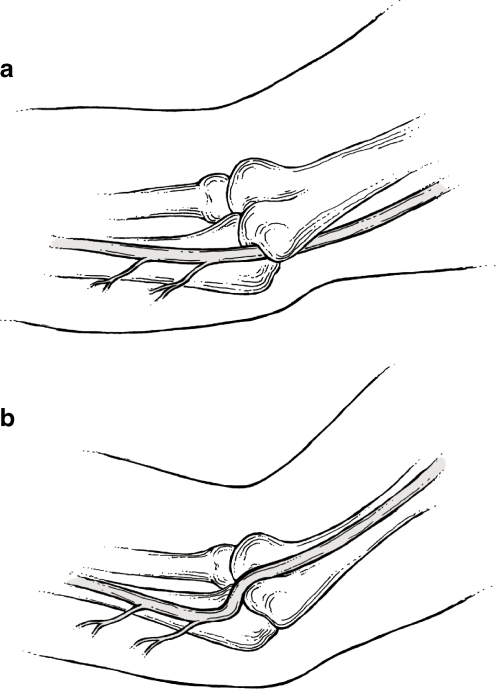

Anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve can create new compressive sites proximally and especially distally if the nerve is not fully released before transposition (Fig. 6). Therefore, care should be taken during primary surgery to ensure that the proximal intermuscular septum and the distal septum located between the flexor/pronator and the flexor carpi ulnaris muscles are fully excised to permit the nerve to be transposed into the anterior position with no compression or kinking of the nerve. The entrapment or kinking point on the ulnar nerve at the proximal intermuscular septum with anterior transposition is well-known and by contrast the fascial anatomy at the distal transposition site is less understood. There is a distinct fascial septum between the ulnar-innervated flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and the median-innervated flexor/pronator muscle mass [16] (Fig. 5b(B)) This distal fascia septum between these two muscle groups may potentially produce a “new” kinking or compression point on the ulnar nerve at the distal transposition site. As the nerve is released and moved more anteriorly, the potential point for new entrapment moves farther distally. To prevent the distal “kink,” it is important to remove this fascia between the two muscle masses and then follow the nerve distally to ensure that there is no residual fascia or aponeurosis compressing the ulnar nerve at the most distal point of the transposition site. In this series of patients, the finding of a distal kink on the nerve was twice as common as compression proximally at the site of the medial intermuscular septum. In addition to this fascia between the two muscle masses, there is also a very thin, strong fascia overlying the ulnar nerve between the two heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle. This very thin fascia can also act as a tight, sharp compression point distally as the nerve is transposed. A greater awareness of the potential for these distal new entrapment sites would likely significantly improve outcome after any transposition surgery. We recommend that at the completion of the surgical procedure the surgeon run her/his finger along the ulnar nerve both proximally and distally to ensure that there is no residual entrapment point on the nerve. Wehrli and Oberlin noted that 73% of the time an internal brachial ligament (IBL) was present running from the septum, medially and anterior to the ulnar nerve and then back to the septum [32]. The proximal portion of the IBL was on average 11.5 cm above the medial epicondyle and the distal point 8.2 cm above the medial epicondyle. This ligament could be a proximal entrapment point with transposition procedures. These authors and others rightly pointed out that the concept of an Arcade of Struthers is erroneous [5, 30].

Figure 6.

(A) Drawing of the ulnar nerve in situ. (B) With a transposition, it appears to be much easier to ensure a nice proximal transposition without kinking by removing the medial inter muscular septum than to ensure the same smooth, easy transposition distally.

Experience with this large series of patients undergoing recurrent cubital tunnel surgery has allowed us to formulate a theory as to the best practice for management of patients with cubital tunnel syndrome. For decades there has been heated debate as to the “best surgical procedure” to manage cubital tunnel syndrome. Proponents of various procedures enthusiastically support their particular operation, each claiming excellent results. It is our conclusion that it is not necessarily the specifics of a particular operation that yields good or poor results, but rather an understanding of the etiological factors inherent in the development of cubital tunnel syndrome and an understanding of the potential for surgery to create new problems. Therefore, any operative technique described for the management of cubital tunnel syndrome can result in excellent patient outcome if the above principles are followed. By contrast, without adherence to the above principles, a poor result can occur with any of the standard ulnar nerve procedures. An understanding of the causes of cubital tunnel syndrome is necessary to correct the problem (Table 2), and most importantly, it is necessary to ensure that no new areas of compression on the nerve are created with surgery.

Cubital tunnel surgery that fails to relieve symptoms or creates new symptoms will result in postoperative morbidity and patient dissatisfaction. To reduce the possibility of nerve injury or secondary compression on the ulnar nerve with primary cubital tunnel surgery, meticulous surgical technique and early postoperative movement is essential. This study suggests that during primary surgery for cubital tunnel syndrome care should be given to avoid injury to the MABC nerve and the creation of a new point of kinking of the ulnar nerve with the transposition or direct compression with fascial or tendinous bands.

References

- 1.Adelaar RS, Foster WC, McDowell C. Treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg 1984;9A:90–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Bartels RHMA, Menovsky T, Van Overbeeke JJ, Verhagen WIM. Surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow: an analysis of the literature. J Neurosurg 1998;89:722–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Caputo AE, Watson HK. Subcutaneous anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve for failed decompression of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg 2000;25A:544–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Chan RC, Paine KW, Varughese G. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow: comparison of simple decompression and anterior transposition. Neurosurgery 1980;7:545–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dellon AL. Musculotendinous variations about the medial humeral epicondyle. J Hand Surg 1986;11B:175–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve during cubital tunnel surgery. J Hand Surg 1985;10B:33–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Filippi R, Charalampaki P, Reisch R, Koch D, Grunert P. Recurrent cubital tunnel syndrome. Etiology and treatment. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2001;44:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gabel GT, Amadio PC. Reoperation for failed decompression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the elbow. J Bone Jt Surg 1990;72A:213–9. [PubMed]

- 9.Geutjens GG, Langstaff RJ, Smith NJ, Jefferson D, Howell CJ, Barton NJ. Medial epicondylectomy or ulnar nerve transposition for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Bone Jt Surg 1996;78B:777–9. [PubMed]

- 10.Greenwald D, Moffitt M, Cooper B. Effective surgical treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome based on provocative clinical testing without electrodiagnostics. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:215–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kaempffe FA, Farbach J. A modified surgical procedure for cubital tunnel syndrome: partial medial epicondylectomy. J Hand Surg 1998;23A:492–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Kleinman WB, Bishop AT. Anterior intramuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg 1989;14A:972–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lascar T, Laulan J. Cubital tunnel syndrome: a retrospective review of 53 anterior subcutaneous transpositions. J Hand Surg 2000;25B:453–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Lowe JB, Maggi S, Mackinnon SE. The position of crossing branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve during cubital tunnel surgery in humans. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114:692–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Mackinnon SE. Submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. In: Rengachary SS, Wilkins RH, editors. Neurosurgical Operative Atlas. Park Ridge, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995. p. 225–33.

- 16.Mackinnon SE, Novak CB. Compressive Neuropathies. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, Wolfe SW, editors. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 999–1046.

- 17.Maki Y, Firrell JC, Breidenbach WC. Blood flow in mobilized nerves: results in a rabbit sciatic nerve model. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;100:627–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Masear VR, Meyer RD, Pichora DR. Surgical anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves. J Hand Surg 1989;14A:267–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mowlavi A, Andrews K, Lille S, Verhulst S, Zook E, Milner S. The management of cubital tunnel syndrome: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;106:327–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Nathan PA, Myers LD, Keniston RC, Meadows KD. Simple decompression of the ulnar nerve: an alternative to anterior transposition. J Hand Surg 1992;17B:251–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Nathan PA, Keniston RC, Meadows KD. Outcome study of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow treated with simple decompression and an early programme of physical therapy. J Hand Surg 1995;20B:628–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Nouhan R, Kleinert JM. Ulnar nerve decompression by transposing the nerve and Z-lengthening the flexor pronator mass: Clinical outcome. J Hand Surg 1997;22A:127–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Novak CB, Mackinnon SE, Stuebe AM. Patient self-reported outcome after ulnar nerve transposition. Ann Plast Surg 2002;48:274–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Pasque CB, Rayan GM. Anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg 1995;20B:447–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Pribyl CR, Robinson B. Use of the medial intermuscular septum as a fascial sling during anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg 1998;23A:500–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Race CM, Saldana MJ. Anatomic course of the medial cutaneous nerves of the arm. J Hand Surg 1991;16A:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sarris I, Gobel F, Gainer M, Vardakas DG, Vogt MT, Sotereanos DG. Medial brachial and antebrachial cutaneous nerve injuries: effect on outcome in revision cubital tunnel surgery. J Reconstr Microsurg 2002;18:665–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Seradge H, Owen W. Cubital tunnel release with medial epicondylectomy factors influencing the outcome. J Hand Surg 1998;23A:483–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Steiner HH, von Haken MS, Steiner-Milz HG. Entrapment neuropathy at the cubital tunnel: simple decompression is the method of choice. Acta Neurochir 1996;138:308–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Struthers J. On some points in the abnormal anatomy of the arm. Br Foreign Med Chir Rev 1854;14:224. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Stuffer M, Jungwirth W, Hussl H, Schmutzhardt E. Subcutaneous or submuscular anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Hand Surg 1991;17B:248–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Wehrli L, Oberlin C. The internal brachial ligament versus the Arcade of Struthers: an anatomical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed]