Abstract

Intimate partner violence is one health-related outcome that has received growing attention from those interested in the role of neighborhood context. A limitation of existing contextual health research is its' failure to look beyond urban settings. Because suburban and rural areas have received so little attention, it is not clear whether data generated from urban samples can be generalized to non-urban geographic settings. We began to explore this issue using concept mapping, a participatory, mixed method approach. Data from 37 urban and 24 suburban women are used to explore and compare perceptions of neighborhood characteristics related to intimate partner violence. While several similarities exist between the perceptions of participants residing in urban and suburban areas, some differences were uncovered. These results provide valuable information regarding the perceived relationship between neighborhood context and intimate partner violence and suggest future avenues for research interested in examining the role of geographic setting.

Keywords: Geographic setting, Intimate partner violence, Neighborhood

Introduction

Intimate partner violence is a significant, ubiquitous public health problem affecting women living in all types of neighborhood settings. Kramer et al's1 recent study of intimate partner violence among women using emergency departments and primary care clinics found high lifetime prevalence rates of physical abuse among urban (56.9%), suburban (39.8%) and rural (45.8%) women. While much research has highlighted the profound physical and mental health consequences and individual level risk factors associated with intimate partner violence,2–4 less attention has been given to more macro-level neighborhood contextual influences associated with such experiences.

In the mid 1990's O'Campo et al.5 conducted the first study to explore the relationship between neighborhood context and intimate partner violence. They found that indicators of neighborhood socioeconomic position (e.g., low per capita income and high unemployment rates) were significantly associated with the risk of intimate partner violence during the childbearing year. Cundrai et al.6 also found that couples who lived in impoverished neighborhoods were at an increased of intimate partner violence compared to couples who did not reside in such neighborhoods. More recent work by Browning7 extended this line of research to report that high levels of neighborhood collective efficacy (e.g., willingness of neighbors to help other neighbors) serve as a protective factor against partner violence. To date, there has been inconsistent selection and operationalization of neighborhood variables present in existing multi-level contextual studies8,9 and in the studies on violence. Recent research, employing concept mapping, found that dozens of neighborhood characteristics, almost all of which are not included in these contextual quantitative studies, were thought to influence patterns of intimate partner violence.10 An additional limitation of existing contextual health research is its failure to look beyond urban settings to suburban and rural areas. Despite research that suggests differential experiences in select health outcomes and behaviors between those living in suburban verses urban or rural areas,11 most work exploring neighborhood context and health has focused almost exclusively on urban residential neighborhood environments. Less has been done to explore how macro-level neighborhood characteristics are related to health among those living in settings outside of cities. This trend can also be seen in most neighborhood contextual studies of intimate partner violence, which have focused on city settings7,12,14 or have not explicitly explored the role of urbanization.5,6,13,14 Because suburban and rural areas have received so little attention, it is not clear whether data generated from urban samples can be generalized to non-urban geographic settings.

The primary goal of the research presented here was to explore the views of women residing in urban and suburban areas. We specifically examined their perceptions of 1) the range of neighborhood characteristics related to intimate partner violence and 2) the relative importance of those neighborhood characteristics to intimate partner violence perpetration verses cessation. Specific attention was paid to the identification of similarities and differences between the urban and suburban samples of women.

Materials and methods

This research used concept mapping, a participatory research method that incorporates qualitative data collection methods (e.g., brainstorming and pile sorting) and quantitative analytical tools (e.g., multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis). A unique feature of the method is the emphasis given to participant processing of the results. A detailed description of concept mapping methods and its usefulness in public health research, including a description of the methods employed for the urban sample of this study, has been published previously.15

Participants The selection of study participants was guided by Trochim's16 recommendation that the identification of appropriate concept mapping participants be based on our research goals. To that end, two separate samples were purposively sampled based on our interest in comparing and contrasting urban and suburban women's perceptions of neighborhood context. The urban sample (n = 37) included residents of Baltimore City and the suburban sample (n = 24) were residents of Anne Arundel, Baltimore and Howard Counties (all suburbs of Baltimore City). Because the primary focus of these activities was on participants' perceptions of how neighborhood context might be associated with intimate partner violence, we did not ask participants to talk about their specific experiences of abuse nor did we collect data regarding the number of participants experiencing current or past intimate partner violence. Informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to the start of the data collection and processing activities, and the participants received a monetary reimbursement for their time and thoughts.

Concept Mapping Process The data collection and analysis processes were conducted separately with the two samples (urban women and suburban women). The general concept mapping process is described elsewhere in detail.15 In summary, participants first generated a list of responses to the focal question “what are some characteristics of neighborhoods that could relate in any way, good or bad, to a woman's experience of intimate partner violence?” Results from the brainstorming activities were then sorted by the participants to create clusters of neighborhood items perceived to be closely related to one another. The participants were also asked to rate on a scale of one (no relationship at all) to five (extremely strong relationship) the nature of relationship between the items and intimate partner violence perpetration and cessation. The sorting and rating data were entered in the Concept Systems computer software program that facilitated the production of final cluster maps and pattern matching results. Working with each sample, the researchers and participants collectively explored the item and clustering results to determine a final cluster solution.

Comparisons of Urban and Suburban Samples In order to draw comparisons between the urban and suburban samples, item comparisons were first conducted on the master item lists from each sample.17 Working together, all three members of the research team examined each item generated from the urban sample and looked to the suburban sample list for a comparable item. In some cases exact matches were found (e.g., hotlines) while in others close matches were identified. For example, suburban item #30 “neighborhood watch” was matched with urban item #44 “alertness/vigilance of people.” Next, we compared the final cluster solutions for the urban and suburban samples and explored the overall theme of the clusters and degree of matched items within each cluster. This approach allowed us to determine comparability of both individual elements and culturally perceived concepts (represented by items and clusters) generated by the urban and suburban samples.

Results

Characteristics of the Two Samples A majority of urban sample participants were African American (97%), had completed high school or the equivalent (92%), and were over the age of 30 years (89%). The suburban sample participants were close to evenly split by race; 54% were African American and the rest White. Most had completed high school or the equivalent and were over the age of 30 years (71%).

Neighborhood Characteristics A wide range of neighborhood characteristics items were generated by the participants. Women from the two samples separately identified 51 (urban sample) and 94 (suburban sample) neighborhood items. The complete list of items (and associated item numbers) is presented in Table 1 for the urban sample and Table 2 for the suburban sample. Additional discussion of these items can be found below.

Table 1.

Clusters and items generated by the urban sample and the clusters and matching or similar items among the suburban sample

| Clusters | Items | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster number and name generated by the urban sample | Related cluster number(s) ) generated by the suburban sample | Item name (item number) generated by the urban sample | Related item number generated by the suburban sample |

| Cluster 1: deterioration contributors | Cluster 7 | Poverty (40)** | 73 |

| Evictions (38) | Unmatched | ||

| Isolated locations (41) | 27, 33, 58, 59, 66 | ||

| Lots of people moving in and out (51)** | 6 | ||

| Abandoned houses (27) | 45, 50 | ||

| Lots of trash (6) | 36, 45 | ||

| Cluster 2: Negative social attributes | Cluster 8 | People who are hanging out (1) | 52, 55 |

| Cluster 9 | Violence (42) | 75 | |

| Access to drugs(5) | 34 | ||

| Unemployment (16) | 16, 72 | ||

| People who do not care (7) | Unmatched | ||

| Children exposed to drugs on the street (9) | 34 | ||

| Police that do not care (32) | Unmatched | ||

| Public drunkenness (2) | 20 | ||

| Racial/ethnic segregation (21) | 91 | ||

| Cluster 3: violence attitudes and behaviors | Cluster 1 | Macho attitudes about control (12) | 88 |

| Cluster 8 | Ignorance about intimate partner violence (3) | 32 | |

| People who should know better (4) | Unmatched | ||

| Child abuse (36) | Unmatched | ||

| Lay-offs (39) | Unmatched | ||

| Mental illness (11) | Unmatched | ||

| Absence of adults (10) | Unmatched | ||

| Youth homicide/child homicide (37) | 38 | ||

| Gossip (45) | Unmatched | ||

| Single mothers (8) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 4: stabilization factors | Unmatched | People who intervene themselves (31) | Unmatched |

| Families with young children (49) ** | 5 | ||

| Income/wealth (47) ** | 3, 23 | ||

| Cultural norms (46) | 2, 4, 56, 69, 81 | ||

| People with professional jobs (48) ** | 92 | ||

| Cluster 5: neighborhood monitoring | Cluster 1 | People who call 911, the police, authority (30) | Unmatched |

| Job availability (15) | 43 | ||

| People who take a stand (29) | 26 | ||

| Alertness/vigilance of people (44) | 30, 35, 37 | ||

| Curfew (13) | Unmatched | ||

| Homeownership (28) | 11, 12 | ||

| Cluster 6: communication networks | Cluster 1 | Police presence (23) | 25, 29 |

| Cluster 2 | Churches (24) | 1, 25, 40 | |

| People who are aware of resources (33) | Unmatched | ||

| Communication between neighbors (20) | 77, 78, 82, 89 | ||

| Community networks (22) | 82 | ||

| Neighborhood meetings (43) | 31 | ||

| Playgrounds (17) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 7: community enrichment resources | Cluster 2 | IPV shelters (50) ** | 9, 39 |

| Women's groups (34) | 25 | ||

| Hotlines (25) | 10, 25 | ||

| Outreach centers (35) | 25 | ||

| Emergency assistance programs (26) | Unmatched | ||

| Access to public health facilities (14) | 25, 41 | ||

| Community centers (19) | 46 | ||

| Recreation centers for children (18) | Unmatched | ||

** These five items were added by the researchers to the original list generated by the participants. These items reflected neighborhood characteristics that appear in the literature but not explicitly mentioned by the participants.

Table 2.

Clusters and items generated by the suburban sample and the clusters and matching or similar items among the urban sample

| Clusters | Items | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster number and name generated by the suburban sample | Related cluster number(s) and name(s) generated by the urban sample | Item name (item number) generated by suburban sample | Related item number generated by urban sample |

| Cluster 1: involvement around intimate partner violence | Cluster 3 | Church involvement (1) | 24 |

| Cluster 5 | Neighbors that are not enabling (26) | 29 | |

| Cluster 6 | Neighborhood watch (30) | 44 | |

| Neighborhood meetings (31) | 43 | ||

| Neighbors' awareness of IPV (32) | 3 | ||

| Neighbors awareness of surroundings (35) | 44 | ||

| Nosey neighbors (37) | 44 | ||

| Up and coming neighborhood (44) | Unmatched | ||

| Pre-arranged signs between neighbors to let them know help is needed (77) | 20 | ||

| Knowing neighbor contact information (78) | 20 | ||

| Good neighbor communication about IPV (89) | 20 | ||

| Cohesiveness among neighbors (90) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 2: positive intimate partner violence support systems | Cluster 6 | School system awareness of IPV (7) | Unmatched |

| Cluster 7 | IPV shelters (9) | 50 | |

| Hotlines (10) | 25 | ||

| Resources (25) | 23 | ||

| Responsive police (29) | 23 | ||

| Community center (46) | 19 | ||

| Community newspaper (82) | 20, 22 | ||

| School systems IPV activities (84) | Unmatched | ||

| Neighborhood with IPV prevention focus (85) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 3: resource deficient | Unmatched | Homeless shelters nearby (18) | Unmatched |

| Wooded areas (27) | 41 | ||

| No shelters (39) | 50 | ||

| No churches (40) | 24 | ||

| No medical center (41) | 14 | ||

| Far from resources (59) | 41 | ||

| No community associations (65) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 4: types of isolation | Unmatched | Neighborhood with entertainment outlets (19) | Unmatched |

| Lighting of neighborhood (28) | Unmatched | ||

| Isolation (33) | 41 | ||

| Fences (48) | Unmatched | ||

| Rural areas (58) | 41 | ||

| No/low social support (64) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 5: social isolation | Unmatched | Upkeep of neighborhood (36) | 1 |

| Gated communities (49) | Unmatched | ||

| Code of silence for friends of police and fellow officers (61) | Unmatched | ||

| Distance between houses (66) | 41 | ||

| Cluster 6: stress and violence | Unmatched | Lots of occupational stress in the neighborhood (17) | Unmatched |

| High neighborhood stress (24) | Unmatched | ||

| Lack of supervision of young dating couples (63) | Unmatched | ||

| Poor crime reporting (68) | Unmatched | ||

| Glorifying violence (75) | 75 | ||

| Cluster 7: negative night life | Cluster 1 | Near colleges (14) | Unmatched |

| Neighborhood bars/large number of bars (20) | 2 | ||

| Deteriorating neighborhood (45) | 6, 27 | ||

| Vacant/abandoned houses (50) | 27 | ||

| Playing loud music (53) | Unmatched | ||

| Stores open late (54) | Unmatched | ||

| Red light districts (87) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 8: crime hot spots | Cluster 2 | Presence of illicit drugs/drug activity (34) | 5, 9 |

| Cluster 3 | High crime (38) | 37 | |

| Prostitution (51) | Unmatched | ||

| Hanging out in neighborhood (52) | 1 | ||

| Hanging out in stores (55) | 1 | ||

| Delinquent youths (60) | Unmatched | ||

| Lots of alcohol consumption (62) | Unmatched | ||

| Gang activity (86) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 9: negative economic influences | Cluster 2 | Transience (6) | 51 |

| Repeat IPV offenders (15) | Unmatched | ||

| Unemployment (16) | 16 | ||

| Low income (23) | 47 | ||

| Lack of education (67) | Unmatched | ||

| High unemployment (72) | 16 | ||

| Impoverishment (73) | 40 | ||

| Low job skills (74) | Unmatched | ||

| Low value of education (76) | Unmatched | ||

| Macho cultural attitudes (88) | 12 | ||

| Cluster 10: financial instability | Unmatched | Norms of anger management (4) | 46 |

| Percentage of people renting homes (12) | 28 | ||

| Percent of households with financial instability (42) | Unmatched | ||

| Immigrants (57) | Unmatched | ||

| Economic dependence (71) | Unmatched | ||

| Racial segregation (91)** | 21 | ||

| Cluster 11: demographics and positive economic influences | Unmatched | High income (3) | 47 |

| Percentage of retired people (8) | Unmatched | ||

| Percentage of people owning homes (11) | 28 | ||

| Percentage of single persons (21) | Unmatched | ||

| Percentage of married people (22) | Unmatched | ||

| Jobs available in the area (43) | 15 | ||

| Norms about IPV (56) | 46 | ||

| High society (70) | Unmatched | ||

| Percentage professional people (92) | 48 | ||

| Percentage of men in labor force (93) | Unmatched | ||

| Percentage of women in labor force (94) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 12: family and community dynamics | Unmatched | Children growing up together (5) | 49 |

| Family size (13) | Unmatched | ||

| Extended/large families living in neighborhood (47) | Unmatched | ||

| Strong mother–daughter family connections (79) | Unmatched | ||

| Close generations (80) | Unmatched | ||

| Cluster 13: personal beliefs | Unmatched | Religious norms (2) | 46 |

| Women's beliefs about IPV (69) | 46 | ||

| Cultural norm to suppress IPV talk (81) | 46 | ||

| Parenting practices about IPV (83) | Unmatched | ||

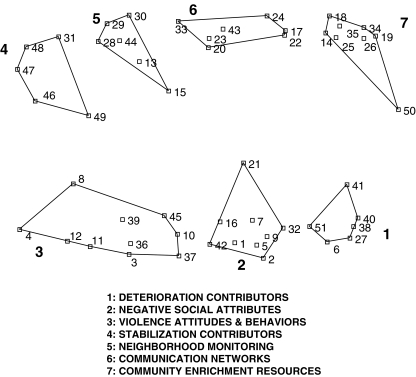

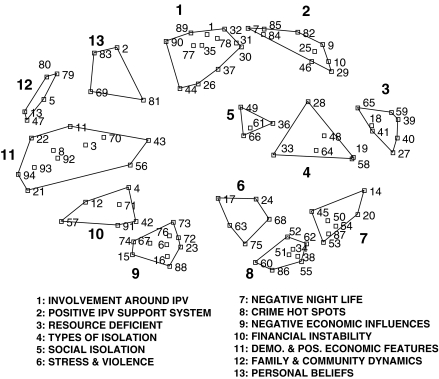

Figures 1 and 2 present the final cluster solution maps depicting the relationships between the items and the clusters for the urban and suburban sample, respectively. The points represent individual neighborhood items, and an item number is associated with each (for corresponding item numbers see Table 1 for the urban sample and Table 2 for the suburban sample). The distance between items, not the exact location of the items on the map, illustrates the degree of similarity between items. Items that were sorted together by more people appear closer to each other on the map. For example, a majority of the participants in the urban sample felt that “evictions” (item #38) and “poverty” (item #40) were quite similar.

Figure 1.

Final cluster map generated by the urban sample. These seven clusters are comprised of the 51 items. The points represent individual items and the associated numbers correspond to the item numbers listed in Tables 1 and 2. The bolded larger numbers each represent a cluster and correspond to the cluster names listed above and in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

Final cluster map generated by the suburban sample. These twelve clusters are comprised of the 94 items. The points represent individual items and the associated numbers correspond to the item numbers listed in Tables 1 and 2. The bolded larger numbers each represent a cluster and correspond to the cluster names listed above and in Tables 1 and 2.

The urban sample produced a final map solution that organized their 51 items into seven clusters. The suburban sample organized their 94 items into a final 13-culster-solution map.

An examination across the clusters generated by the urban and suburban samples revealed that, generally, many of the neighborhood characteristics identified by the urban sample were also identified by the suburban sample (see Tables 1 and 2). For example, the neighborhood characteristics addressing negative economic and social characteristics are represented in the Negative Social Attributes cluster generated by the urban sample and the Negative Economic Influences and Crime Hot Spots clusters generated by the suburban sample. Specifically, neighborhood unemployment is included in the Negative Social Attributes cluster and is represented in the Negative Economic Influences cluster. While many similar neighborhood characteristics were identified by both the urban and suburban samples, select differences were noted. For example, the cluster labeled Stabilization Contributors by the urban sample was not matched by any cluster generated by the women residing in suburban neighborhoods (see Urban Cluster 4, Table 1). However, four of the five items in the cluster Stabilization Contributors generated by the urban sample were matched or related to items generated by the suburban women. Thus, the suburban women identified several of those same items but included them in clusters that are not similar to the Stabilization Contributors cluster. In addition, eight clusters generated by the suburban sample contain content that was not represented in the urban sample. These clusters identify characteristics related to resource deficiency, physical and social isolation, stress, positive economic factors and personal beliefs.

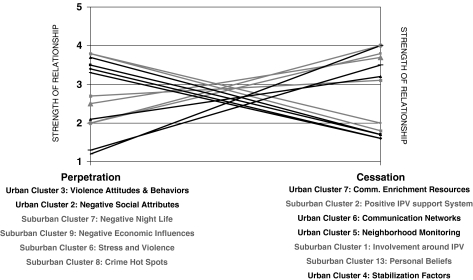

In general, characteristics rated as having a strong relationship with perpetration were rated as having a weak relationship with cessation and vise versa. The clusters considered strongly related to the perpetration outcome were not considered as strongly related to the cessation outcome (Fig. 3). Both samples identified clusters addressing community resources and support systems as having the strongest relationship with cessation of intimate partner violence. These same clusters were not considered to be as important for perpetration of intimate partner violence. Instead, both samples identified clusters addressing violence attitudes and behaviors as being the most strongly related to perpetration of violence. The unmatched Stress & Violence cluster generated by the suburban sample fell within those clusters considered to be strongly related to perpetration. In addition, the unmatched Personal Beliefs cluster identified by the suburban sample and the unmatched Stabilization Contributors cluster described by the urban sample were found to have a strong relationship with cessation.

Figure 3.

Rating results for strength of cluster relationship (1=no relationship; 5=extremely strong relationship) to perpetration and cessation of intimate partner violence. The clusters generated by the urban sample are represented in black. The clusters generated by the suburban sample are represented in grey.

Discussion

Our research findings provide an essential starting point for understanding how neighborhood characteristics are related to intimate partner violence in urban and suburban settings. The participants in both the urban and suburban samples were able to identify many neighborhood characteristics they felt to be important influences on intimate partner violence. In addition to naming previously studied characteristics, several of the listed factors go well beyond those that have been examined in existing literature.5–7 For example, much attention was given by both samples to neighborhood social characteristics that reflect the relationship or connectedness between residents, such as the alertness and vigilance of neighbors and communication between neighbors. The implicit intimate and relational nature of the problem of intimate partner violence may make it a unique outcome in the field of neighborhood effects studies and necessitate the collection of neighborhood data specific to intimate partner violence. In addition, both samples raised the importance of positive community enrichment resources such as community centers.

Several similarities exist between the perceptions of urban and suburban participants; however, select differences were uncovered. Specifically, the suburban concept mapping results included characteristics related to resource deficiency, physical and social isolation, stress, and positive economic factors and personal beliefs. However, these may be due to the nature of the different environments and have less to do with the relationship between neighborhood context and intimate partner violence. This point is made clear by the fact that both samples shared similar perceptions regarding the cluster they felt to be most strongly related to perpetration and cessation of intimate partner violence. Neighborhood characteristics related to violence attitudes and behaviors were felt to be most strongly related to perpetration of violence and community resources and support systems most strongly related to cessation of violence.

The use of the concept mapping method for this type of exploration is innovative and its application has several strengths worth highlighting. The high level of participant inclusion in the data collection and analysis process generates findings that are reflective of the individuals' and groups' perceptions.15 The approach draws from the lived experiences of individuals and provides an increased understanding of the relationship between neighborhood context and intimate partner violence. Through a process of uncovering novel neighborhood characteristics, the results of this study provide a first step towards the development of health-specific contextual theory. Additional work examining participant perceptions regarding the relationship between such characteristics and additional health outcomes will further contribute to our understanding of the pathways and mechanisms by which contextual factors influence health.

While this study does provide valuable insights regarding the role of neighborhood context in both urban and suburban settings, it does suffer select limitations worth noting. The purposive sampling technique with a relatively small number of participants is a potential study limitation. The sample was limited to women as we thought that women may differ from men in their perspectives on and experiences with intimate partner violence. Obtaining and exploring the male perspective of the relationship between neighborhood context and intimate partner violence is an important next step in this line of research. In addition, the eligibility criteria was not limited to a single neighborhood geographic context. For example, the participants from the urban sample resided in areas throughout the eastern portion of Baltimore City. Future studies might consider recruiting from smaller geographically defined areas. The results of this study will be strengthened by additional qualitative and quantitative explorations of the differing geographic settings (i.e., urban, suburban and rural) that can be used to produce more generalizable findings.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that while many neighborhood characteristics are thought to play a common role across urban and suburban settings, additional geographic-specific influences do exist. These distinctive factors need to be considered by those interested in the development of health-specific contextual theories and examined by researchers conducting future quantitative neighborhood contextual health research. The intervention implications of such differences warrant further consideration.

References

- 1.Kramer A, Lorenzon D, Mueller G. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and health implications for women using emergency departments and primary care clinics.Women Health Issues. 2004;14(1):19–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Campbell J. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002 Apr 13;359(9314):1331–1336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. ArchIntern Med. 2002 May 27;162(10):1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Plichta SB, Falik M. Prevalence of violence and its implications for women's health. Women Health Issues. 2001 May–Jun;11(3):244–258. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.O'Campo P, Gielen AC, Faden RR, Xue X, Kass N, Wang MC. Violence by male partners against women during the childbearing year: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 1995 Aug;85(8 Pt 1):1092–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark C, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Jul;10(5):297–308. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Browning CR. The span of collective efficacy: extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. J Marriage Family. 2002;64(4):883–850. [DOI]

- 8.O'Campo P. Invited commentary: advancing theory and methods for multilevel models of residential neighborhoods and health. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Jan 1;157(1):9–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Rajaratman J, Burke JG, O'Campo P. (Accepted, Pending Revision). Maternal & child health and neighborhood residence: a review of the selection and construction of area-level variables.

- 10.O'Campo P, Burke J, Peak GL, McDonnell KA, Gielen AC. Uncovering neighbourhood influences on intimate partner violence using concept mapping. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005 Jul;59(7):603–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER. The importance of place of residence: examining health in rural and nonrural areas. Am J Public Health. 2004 Oct;94(10):1682–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Block C. Does neighborhood collective efficacy make a difference behind closed doors? Presented at the American Sociological Association conference, August 2002.

- 13.Miles-Doan R. Violence between spouses and intimates: does neighborhood context matter? Soc Forces. 1998;77(2):623–645. [DOI]

- 14.Pearlman DN, Zierler S, Gjelsvik A, Verhoek-Oftedahl W. Neighborhood environment, racial position, and risk of police-reported domestic violence: a contextual analysis. Public Health Rep. 2003 Jan–Feb;118(1):44–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Burke JG, O'Campo P, Peak G, Gielen A, McDonnell K, Trochim W. An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research methodology. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1392–1410. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Trochim W. Concept mapping: soft science or hard art? Eval Program Planning. 1989;12:87–110. [DOI]

- 17.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira; 1995.