Abstract

Research on drug treatment facility locations has focused narrowly on the issue of geographic proximity to clients. We argue that neighborhood conditions should also enter into the facility location decision and illustrate a formal assessment of neighborhood conditions at facilities in a large, metropolitan area, taking into account conditions clients already face at home. We discuss choice and construction of small-area measures relevant to the drug treatment context, including drug activity, disadvantage, and violence as well as statistical comparisons of clients’ home and treatment locations with respect to these measures. Analysis of 22,707 clients discharged from 494 community-based outpatient and residential treatment facilities that received public funds during 1998–2000 in Los Angeles County revealed no significant mean differences between home and treatment neighborhoods. However, up to 20% of clients are exposed to markedly higher levels of disadvantage, violence, or drug activity where they attend treatment than where they live, suggesting that it is not uncommon for treatment locations to increase clients’ exposure to potential environmental triggers for relapse. Whereas on average both home and treatment locations exhibit higher levels of these measures than the household locations of the general population, substantial variability in public treatment clients’ home neighborhoods calls into question the notion that they hail exclusively from poor, high drug activity areas. Shortcomings of measures available for neighborhood assessment of treatment locations and implications of the findings for other areas of treatment research are also discussed.

Keywords: Facility location, Neighborhoods, Spatial analysis, Substance abuse treatment

Introduction

Recent evidence suggests that differences in the propensity to use illicit drugs among individuals may be related to differences in neighborhood environments, with individuals residing in lower income and disorganized (i.e., disadvantaged) communities having higher rates of drug use after adjusting for individual-level differences in age, race, employment, and income.1–3 The theoretical underpinnings for these studies derive from social ecology theory4–6 and strain and social disorganization theories,7–9 which postulate that illicit drug use can be explained in part as a response to neighborhood environments that cause undue stress or strain, lack the community-level organization or collective efficacy to sanction illegal-drug-using behavior, and present the individual with frequent opportunities to purchase and use illegal drugs. In fact, both drug-using and abstaining residents of more disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to be approached by someone offering illicit drugs than residents of more advantaged neighborhoods.10

The relationship between illicit drug use and neighborhood context may have implications for individuals recovering from substance abuse. Encouraging patients to move away from a “bad neighborhood” to reduce stressful circumstances, visual and auditory cues for use, and social ties that facilitate use is already a goal of many treatment counselors.11,12 A recent review attempting to identify potential neighborhood influences on relapse and retention in treatment suggests that conditions around the treatment site may also influence treatment outcomes, particularly social and economic stressors such as disadvantage and violence, visible drug activity, and drug availability.13 This suggests that decisions regarding the location of drug treatment facilities should consider neighborhood context in addition to proximity to potential clients. To date, however, no study has forwarded measures or methods relevant to assessing the appropriateness of neighborhood conditions at treatment locations in a large urban area.

In this paper, we present such an assessment for the public treatment system in Los Angeles County (LAC). Two considerations motivate our focus on the public treatment system. First, public agencies are typically responsible for meeting treatment needs within a set geographic area and must strategically select treatment locations to meet those needs. Second, the public system is more readily influenced by public policy. For example, contractual agreements with providers that receive public funds to provide treatment can be made contingent upon conditions at the treatment location. Whereas an objective assessment of neighborhood conditions at treatment locations relative to where clients live can help guide facility location decisions, we recognize that it is no substitute for fair siting processes and will not necessarily satisfy concerned residents' opposition to a planned site or expansion.17–19 The aims of this assessment are threefold:

Summarize the level and variability of potential environmental triggers for relapse at patients' residential and treatment locations;

Test for systematic differences between residential and treatment locations;

Estimate the extent to which patients are exposed to higher levels of potential environmental triggers for relapse at treatment compared to where they live.

Our study area, LAC, contained 494 community-based outpatient and residential programs that received public funds and provided services to a sizable patient population at 199 physical locations during fiscal years 1998–2000. During this period, 22,707 patients who did not meet criteria for homelessness (i.e., unable to provide for his/her own adequate shelter, including individuals who reside, for example, in shelters or temporary voucher hotels) and were able to report a zip code of residence were admitted to these programs for illicit drug-use problems.

Methods

Treatment Episode Sample

Our patient-level data come from treatment entry and discharge records collected on all patients discharged during fiscal years 1998–2000 from programs that contract with the county Alcohol and Drug Program Administration. These records are collected as part of the Los Angeles County Participation Reporting System (LACPRS). All data are by self-report and include zip-code identifiers for the patient's place of residence and the treatment facility.

We restrict the sample to patients treated at community-based outpatient or residential recovery programs (i.e., not incarcerated or in a detoxification program) who reported a primary problem at admission with an illicit drug [heroin, cocaine, crack, marijuana, phencyclidine (PCP), methamphetamines, ecstasy, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), or nonprescription methadone] and who both lived and attended treatment in LAC. Primary alcohol clients are omitted because of likely differences in neighborhood conditions leading to relapse and retention. The analysis also excludes homeless patients, whose residential location is not reported. We limit our sample further to patients' first discharge during the study period to permit generalization of findings to the population of patients rather than treatment episodes. Of these patients, 91 (0.4%) were dropped because they did not report a valid residential zip code.

We also restrict the set of zip codes to avoid outliers resulting from low precision of the contextual measures, some of which are rates of rare events per capita, household, or family. Specifically, we drop zip codes with fewer than 5000 residents.1 One zip code (91310, Castaic, CA) is missing from the shapefile required to construct the zip-code level measures; another (90704, Catalina Island) is dropped because it is an island far from the rest of the county. These restrictions reduce the sample of zip codes from 287 to 259 (representing 99.6% of the total LAC Census 2000 population) and the sample of patients by 0.9% from 21,533 to 21,335. Finally, the treatment location of an additional 4% of remaining patients could not be uniquely identified because of inconsistencies in the facility-episode link file. These deletions leave 21,420 cases for analysis of home neighborhood and 21,581 for analysis of treatment neighborhood, representing 99.1 and 99.8%, respectively, of all nonhomeless patients living and receiving community-based outpatient or residential treatment for an illicit substance abuse problem in the county.

Contextual Measures

The contextual measures were drawn from a recent review13 that attempted to enumerate all contextual influences that might impede treatment retention. Based on this review, three factors seem most relevant for our analysis: neighborhood-level disadvantage, violence and victimization, and drug activity.2

The measures used to approximate these constructs are drawn from data sources at different geographic resolutions. We align measures by aggregating to zip codes, the finest resolution in LACPRS. To mitigate the problem of variation in population size among zip codes, most measures are computed as per capita rates. To correct misalignment, counts from census areas and administrative reporting areas are apportioned to zip codes proportional to the share of their area that falls in each zip code. Our estimate of the zip-code population, required as the denominator for per capita contextual measures, is computed by aggregating from census blocks, again apportioned according to the share of their area in each zip code.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

We adopt a common version of the disadvantage measure shown by previous research to have high reliability (α = 0.91 in this sample),1,14 which consists of four components derived from 2000 Census data, standardized and then summed within each zip code: (1) percent of individuals living below the poverty line; (2) male unemployment rate; (3) percent of female-headed households; and (4) percent of families receiving public assistance.

Violence and Victimization

Average, annual, zip code rates of homicide and calls for service to police per capita during 1996–2000 are our proxies for violence victimization and were estimated from counts from California Department of Health and Human Services (CHHS) and the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). We limited calls to those implying violence or victimization: assault with a deadly weapon, arson, attack, battery, bomb, burglary, child abuse, dispute, explosion, kidnapping, murder, prowler or a neighbor reporting an open window or door,3 robbery, screaming, shots fired, theft, and vandalism. Although such events are likely to be underreported in communities distrustful of police, we suspect that, overall, neighborhoods with more violence probably log more calls than others. The homicides measure relies on reporting by health facilities rather than law enforcement.

Drug Activity

Drug-related deaths, arrests, and local involvement in treatment proxy drug activity. Drug-related deaths were defined as those with a primary cause of drug dependence, nondependent abuse of drugs, drug poisoning, or drug psychoses. Counts were obtained from CHHS for 1996–2000 and divided by the zip-code population to obtain a mean annual per capita rate. Drug-related deaths have been used by others to measure local rates of use,15 but a weakness of the measure is that the likelihood of death given use also depends on drug-use choice, health, and access to health care. For example, overdoses are more closely associated with poly and alcohol drug use and recent episodes of abstinence following incarceration or treatment.16

LAPD arrests during 1998–2000 for drug offenses involving possession, use, presence during use, paraphernalia, fraudulent prescriptions—“use” offenses—and sale, transport, or furnishing of illicit drugs or fraudulent prescriptions—“trafficking” offenses—were obtained for LAPD reporting districts (RDs) and aggregated to zip codes. Failure-to-register arrests (i.e., drug felons who fail to register with authorities in a new locality), which do not necessarily indicate current drug activity, are excluded. “Use” and “trafficking” offenses are highly correlated (≥0.9) among zip codes within and between years, so we sum them for a single measure. Although arrests depend on policing effort, recent evidence suggests that they are a good relative measure of visible drug activity,17 which is relevant to our theories regarding neighborhood triggers for relapse.

Local involvement in drug treatment is measured as the per capita rate of discharges from inpatient chemical dependency care, from the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development Patient Public Discharge Data for calendar years 1999–2000, and nonhospital discharges from publicly funded programs in 1998–1999, from LACPRS data. Although the use of an aggregate measure of drug treatment episodes to measure the neighborhood context of drug treatment may appear circular, note that many patients live in areas where many of their neighbors have also sought treatment for substance abuse problems, whereas others live in areas with relatively few other patients nearby. In this sample, the annual rate of treatment per zip code ranged from 4 to 304 per 10,000 residents (mean = 40, SD = 30). Thus, the measure captures important variation with respect to one indicator of drug activity.

Arrest and calls for service data are available only for LAPD’s jurisdiction, a subsection of LAC. We refer to the “LAPD study area” as the 80 LAC zip codes with at least 75% of their area in LAPD RDs. This subarea contains about a third of all LAC discharges and facilities.

Statistical Analysis

To provide visual perspective, we constructed maps showing facility locations, quintiles of the distribution of patient density per unit area, and quintiles of contextual measures by zip code. For brevity, of the contextual measures, only the map for disadvantage is provided here.

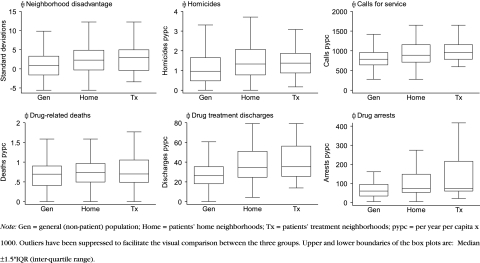

To examine the issue of whether neighborhood conditions around treatment facilities differ from conditions where patients live, we generate box-and-whisker plots for each contextual measure within patients’ (1) home zip codes and (2) treatment zip codes, where the unit of analysis is the patient, which naturally accounts for differences in the volume of treatment episodes across facilities. To allow comparison of patient and treatment locations to the general, nonclient population, the distribution of contextual measures among census households is also shown. Extreme outliers [i.e., less than (25th percentile − 1.5IQR) or greater than (75th percentile + 1.5IQR)] are suppressed to allow adequate space for comparing medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The count of the general population is the 2000 Census count less the number of patients residing in the zip code. Paired t tests and nonparametric Wilcoxon matched-pairs, signed-rank tests are employed to test the hypothesis that patients’ treatment locations are systematically higher in each measure than their home neighborhoods.

To assess the statistical significance of differences between patients’ home and treatment locations compared with the locations of the general population, we estimate ratios of means: the mean of the contextual measure at patients’ home (or treatment) neighborhoods relative to the mean for the general population. A one-sample test is used because the general population count is a known population parameter rather than a sample estimate. These ratios and other analyses are computed separately by treatment modality because one might expect outpatient drug-free, outpatient methadone maintenance, and residential facilities to exhibit systematically different spatial patterns. Spatial autocorrelation is potentially a problem for the t and Wilcoxon tests described above because correlation among zip-code measures of disadvantage (and other contextual measures) may vary with the distance between zip codes, violating the independence assumption of these tests. Lagged versions of the contextual measures to correct for autocorrelation produced findings and conclusions equivalent to those reported in this paper.184

A separate concern is the degree to which facility locations expose patients to higher levels of the contextual measures than their home neighborhoods. We estimate the percent of patients for whom a given contextual measure at the treatment site is at least a standard deviation greater than at the same patient’s home location and the corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Results

Visual maps show the distribution of neighborhood conditions throughout the study area and provide suggestive evidence of differences between home and treatment locations to guide more formal comparisons. The maps in Fig. 1 suggest that facilities tend to be located in areas with the greatest concentration of clients, and patients and facilities tend to be located in areas with relatively high disadvantage. The box plots in Fig. 2 provide a more formal visual comparison. They demonstrate that the range of neighborhood conditions where patients live is similar to the range for the general population, with the exception of involvement in drug treatment. Thus, patients are found over nearly the full range of levels of disadvantage, violence, drug deaths, and drug arrests, although there are some zip codes with no treatment patients. The distributions for treatment locations are less variable and indicate that there are no facilities in areas lowest in disadvantage, violence, treatment involvement, and drug arrests.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of patients, treatment centers, and disadvantage by zip code in Los Angeles County. Zip codes excluded from the analysis in white.

Figure 2.

Distribution of contextual measures in the residential neighborhoods of the general population and patients' home and treatment neighborhoods.

By comparing the medians and lower quartiles of the box plots, a consistent pattern is seen: Facility locations have the highest levels of disadvantage, violence, and drug activity, followed by home locations of patients and of the nonclient population.

Tests for differences between patients’ home and treatment locations at the mean and median (not shown) were nonsignificant at the 5% level. However, home and treatment locations are significantly different, on average, from the general population for all measures as shown by the ratios in Table 1. For example, the average outpatient lives in a neighborhood 2.7 times as disadvantaged as the average nonpatient and attends treatment in a neighborhood with 2.6 times the disadvantage. The ratios are all significantly greater than 1 at the 5% level, so that, on average, patients are more exposed to all of the contextual measures than the general population.

Table 1.

Ratio of mean contextual measure at home (or treatment) neighborhood to mean for general household population

| Modality | Contextual measure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA county | LA city | |||||||

| N | Disadvantage | Homicides | Drug deaths | Treatment episodes | N | Calls for service | Drug arrests | |

| Home neighborhood | ||||||||

| Outpatient | 13,922 | 2.7(0.03) | 1.4(0.01) | 1.2(0.01) | 1.3(0.01) | 4347 | 1.2(0.01) | 1.7(0.05) |

| Meth. maint. | 1851 | 2.8(0.08) | 1.4(0.02) | 1.2(0.02) | 1.4(0.02) | 663 | 1.3(0.03) | 2.0(0.15) |

| Residential | 5647 | 2.5(0.05) | 1.3(0.01) | 1.3(0.01) | 1.4(0.02) | 1830 | 1.3(0.02) | 2.2(0.11) |

| Patients in all modalities | 21,420 | 2.6(0.03) | 1.4(0.01) | 1.2(0.01) | 1.4(0.01) | 6840 | 1.3(0.01) | 1.9(0.05) |

| Treatment neighborhood | ||||||||

| Outpatient | 14,445 | 2.6(0.03) | 1.4(0.01) | 1.2(0.01) | 1.4(0.01) | 4225 | 1.4(0.01) | 2.3(0.05) |

| Meth. maint. | 1988 | 3.0(0.06) | 1.4(0.02) | 1.2(0.01) | 1.3(0.01) | 935 | 1.2(0.01) | 1.9(0.05) |

| Residential | 5148 | 2.0(0.06) | 1.3(0.01) | 1.2(0.01) | 1.4(0.02) | 1626 | 1.3(0.02) | 1.9(0.10) |

| Patients in all modalities | 21,581 | 2.5(0.02) | 1.3(0.01) | 1.2(0.01) | 1.4(0.01) | 6786 | 1.3(0.01) | 2.1(0.04) |

The difference in means is significant at the 5% level for all cells based on two-tailed t tests. Standard error of the difference in means in parentheses. N is the number of patients. “Meth. Maint.” is methadone maintenance in outpatient settings; “Outpatient” is all other outpatient care. The LA City study area is defined as the 80 zip codes in LA County with at least 75% of their area in Los Angeles Police Department reporting districts.

Table 2 reports the percent of patients who attend treatment in a zip code at least 1 standard deviation (SD) greater than their home neighborhood for each measure. Values range from 0 to 21% and are typically from 10 to 15%. Treatment–home differences of 1 SD or more are most frequent in the LAPD study area in outpatient settings with respect to drug arrests (21 and 18%), drug-free outpatient settings with respect to calls for service (19%), and residential settings in the larger LAC area with respect to disadvantage (17%).

Table 2.

Percent of patients whose treatment neighborhood is at least 1 SD “worse” than their home neighborhood

| Contextual measure | Outpatient | Meth. maint. | Residential | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% CI | Percent | 95% CI | Percent | 95% CI | |

| LA County (N = 20410) | ||||||

| Disadvantage | 12 | 11–12 | 10 | 8–11 | 17 | 16–18 |

| Homicides | 9 | 8–9 | 9 | 8–11 | 13 | 12–14 |

| Drug deaths | 14 | 13–14 | 12 | 10–13 | 7 | 6–8 |

| Treatment episodes | 14 | 14–15 | 11 | 10–13 | 16 | 15–17 |

| LA City (N = 4587) | ||||||

| Calls for service | 19 | 17–20 | 10 | 7–12 | 5 | 4–6 |

| Drug arrests | 21 | 19–22 | 18 | 15–21 | 0 | 0–1 |

“Meth. maint.” is methadone maintenance in outpatient settings; “Outpatient” is all other outpatient care. The LA City study area is defined as the 80 zip codes in LA County with at least 75% of their area in Los Angeles Police Department reporting districts.

Discussion

Recent studies have called attention to the importance of proximity to treatment clients in decisions regarding the location of substance abuse treatment facilities.19–22 Associations between illicit drug use and neighborhood context1,3 suggest that certain aspects of the neighborhood environment around the treatment site may also affect recovery.12,13 We illustrated an assessment of neighborhood conditions at publicly financed treatment facilities in a large, metropolitan area and compared them to conditions where patients they serve live.

Contrary to the common notion that public system patients are concentrated in disadvantaged areas, we find variability in patients’ residential locations covering nearly the full range of neighborhoods in the county in terms of disadvantage, violence, and drug activity. The extent of variation in home locations is such that, excluding extreme outliers, the distributional range of each measure among patients is indistinguishable from the range for the nonpatient household population. These findings support Saxe et al.’s2 contention that drug abuse is a problem that “belongs” in a sense to all communities. Nonetheless, on average, patients in Los Angeles are located in areas with significantly higher levels of social stressors and drug activity than other county residents.

We find no evidence of systematic differences in neighborhood conditions between treatment locations and where patients live in residential, methadone maintenance outpatient, and drug-free outpatient settings. However, a consequence of the variability in patient locations relative to treatment locations is that many patients attend treatment in neighborhoods with higher levels of disadvantage, violence, and drug activity than the neighborhoods where they live. These differences merit attention because they indicate increases in exposure to potential environmental triggers for relapse as a result of treatment. Taking one standard deviation as a “large” difference, for example, 21% of outpatients in Los Angeles had a large treatment–home difference in drug arrests, and 19% had a large treatment–home difference in victimization-related calls for service. The percent of patients experiencing differences of this magnitude or greater for other measures and modalities is smaller, on the order of 10–15. Our assessment does not take into account that some patients may already be exposed to similar environments in other aspects of their daily lives, e.g., at the workplace.

Interpretation of these findings is subject to the limitations of the data available for the assessment. Our findings are representative only of LAC. Only additional research or assessments can establish whether these relationships hold in other areas. As a neighborhood proxy, zip codes suffer several shortcomings, although they often appear in neighborhood analyses.23,24 An important, additional limitation is the exclusion of homeless patients from the sample because of the unavailability of information on where they typically reside. Because treatment demand by homeless patients is likely to concentrate in disadvantaged areas, our estimates of treatment–home neighborhood differences do not necessarily imply an excess of treatment capacity in these areas. Instead, they point to a potential risk factor for a substantial share of public system patients. Finally, data with adequate geographic coverage were not available to measure treatment at nonhospital facilities that do not receive public funds. Furthermore, some have speculated that potential data sources for measuring private care, such as insurance claims, often misclassify or do not capture drug treatment.25 A major challenge for future assessments will be to improve the small-area neighborhood measures forwarded here given these and other shortcomings we discussed.

Acknowledgment

This analysis was supported by NIAAA grant R21AA013818, NIDA grant T32DA007272, and CH05-DREW-616. The author wishes to thank Ricky N. Bluthenthal, Douglas Longshore, Jonathan P. Caulkins, Martin Y. Iguchi, and two anonymous referees for comments on drafts of the manuscript, and John Bacon and Tom Tran of the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, Alcohol and Drug Programs Administration for assistance with data preparation. All errors are the author’s own.

Footnotes

A Poisson probability model was developed to guide selection of these thresholds and the choice of how many prior years of data on these rare events to include in the final average per capita rates that serve as our measures. Whereas a longer history increases precision, the cost is including “old” data that may not reflect current circumstance. Based on the model, we include 5 years of homicide rates (1996–2000) and 2 years (fiscal 1998–2000 and calendar 1999–2000) for other measures. In the smallest zip codes (5000 residents), this yields an estimated statistical power of 75% to detect fourfold differences relative to the mean zip code, and 25% power to detect twofold differences. Most patients (75%) live in and attend treatment in zip codes with 25,000 residents or more and better precision. The estimates and Poisson model are available from the author.

It is important to emphasize that we examine drug activity rather than drug availability because of the difficulty of accurately measuring the latter in an illicit market.

These incidents are relevant for inclusion in the violence and victimization measure because, according to a personal communication with LAPD’s Crime Analysis Unit, they often result in apprehension of a suspect for breaking and entering or burglary.

One way to eliminate spatial autocorrelation is to use “lagged” measures, which are residuals from a regression of the measure on the average of that measure in neighboring zip codes. For our contextual measures, Geary's C, a global measure of spatial association, found statistically significant spatial autocorrelation at the 5% level in the unadjusted, but not the lagged, measures. We defined neighbor relationships by first-order contiguity.

Ph.D. Policy Analysis, Pardee RAND Graduate School, 2004. M.Phil. Policy Analysis, Pardee RAND Graduate School, 2000. B.S. Industrial Engineeering and Operations Research, UC Berkeley 1998.

References

- 1.Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42:151–165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Saxe L, Kadushin C, Beveridge A, et al. The visibility of illicit drugs: implications for community-based drug control strategies. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1987–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Lillie-Blanton M, Anthony JC, Schuster CR. Probing the meaning of racial/ethnic group comparisons in crack cocaine smoking. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;269(8):993–997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996.

- 5.Moos RH. Conceptualization of human environments. Am Psychol. 1973;28:652–665. [DOI]

- 6.Kelly JG. Ecological constraints on mental health services. Am Psychol. 1966;21:535–539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Merton RK. Social structure and anomie. Am Sociol Rev. 1938;3:672–682. [DOI]

- 8.Agnew R. A revised strain theory of delinquency. Soc Forces. 1985;64:151–167. [DOI]

- 9.Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–88. [DOI]

- 10.Storr CL, Chen CY, Anthony JC. Unequal opportunity: neighborhood disadvantage and the chance to buy illegal drugs. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(3):231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Suedfeld P. The medical relevance of the hospital environment. In: Oborne DJ, Gruneberg MM, Eisner JR, eds. Research in Psychology and Medicine. London: Academic Press; 1979.

- 12.Gifford R, Hine DW. Substance misuse and the physical environment: the early action of a newly completed field. Int J Addict. 1991;25(7A and 8A):827–853. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Jacobson JO. Place and attrition from substance abuse treatment. J Drug Issues. 2004;34(Winter):23–50.

- 14.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush S, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Corman H, Mocan HN. A time-series analysis of crime, deterrence, and drug abuse in New York city. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90(3):584–604.

- 16.Dark S, Hall W. Heroin overdose: research and evidence-based intervention. J Urban Health. 2003;80(2):189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Warner BD, Coomer BW. Neighborhood drug arrest rates: are they a meaningful indicator of drug activity? A research note. J Res Crime Delinq. 2003;40(2):123–138. [DOI]

- 18.Haining R. Spatial Data Analysis in the Social and Environmental Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- 19.Beardsley K, Wish ED, Fitzelle DB, O'Grady K, Arria AM. Distance traveled to outpatient drug treatment and client retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25:279–285. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Umbricht-Schneiter A, Ginn DH, Pabst KM, Bigelow GE. Providing medical care to methadone clinic patients: referral vs. on-site care. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(2):207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Friedmann PD, D'Aunno TA, Jin L, Alexander JA. Medical and psychosocial services in drug abuse treatment: do stronger linkages promote client utilization? Health Serv Res. 2000;35(2):443–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Friedmann PD, Lemon SC, Stein MD, Etheridge RM, D'Aunno TA. Linkage to medical services in the drug abuse treatment outcome study. Med Care. 2001;39(3):284–295. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Acevedo-Garcia D. Zip code-level risk factors for tuberculosis: neighborhood environment and residential segregation in New Jersey, 1985–1992. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(5):734–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bingham RD, Zhang Z. Poverty and economic morphology of Ohio central-city neighborhoods. Urban Aff Rev. 1997;32(6):766–796. [DOI]

- 25.Stein BD, Zhang W. Drug and alcohol treatment among privately insured patients: rate of specialty substance abuse treatment and association with cost-sharing. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(2):109–218. [DOI] [PubMed]