Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in prisoners represents an important public health problem. However, there is very little information about HCV-related health-related quality of life (HRQOL). We examined the effect of HCV antibody positivity, HCV viremia, and being a prisoner on prisoners'' HRQOL. Population-based health surveys incorporating HCV screening were conducted among prisoners at New South Wales (NSW), Australia, correctional centers in 1996 and 2001. HCV antibody and HCV RNA status were determined from venous blood sampling. HRQOL and mood status were assessed using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) Health Survey and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Comparison of HRQOL scores between HCV antibody negative, HCV antibody positive/non-viremic, and HCV antibody positive/viremic and assessment of temporal change in HRQOL between 1996 and 2001 within groups were made using ANCOVA adjusting for confounders. Factors associated with HRQOL were determined in linear regression models. Analyses between HCV antibody negative (n = 423), HCV positive/non-viremic (n = 89), and HCV positive/viremic (n = 178) prisoners found no measurable effect of HCV on HRQOL, including that attributable to HCV viremia. Compared to uninfected Australian population norms, prisoners had lower HRQOL irrespective of HCV status. The prevalence of ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’ depressive symptoms was greater in the HCV antibody positive/viremic group than the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic group or the HCV antibody negative group. Selected demographic factors (age), co-morbidity, severity of depressive symptoms and medical care utilization influenced HRQOL. There was evidence to support the effect of knowledge of HCV status on HRQOL. In conclusion, our findings contrast with previous studies in non-prisoner groups in which HCV infection appears to decrease overall HRQOL. Non-HCV factors may override HCV-specific HRQOL impairment in this population. Targeted management strategies are required to improve HRQOL of prisoners.

Keywords: Australia, HCV, Prisoner, Quality of life, SF-36

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection appears to impair health-related quality of life (HRQOL) even in the absence of severe liver pathology.1–3 This suggests that factors other than hepatic inflammation and fibrosis are responsible for impairment in HRQOL. Reduction in HRQOL in HCV infected individuals may be related to the direct effect of HCV infection or other factors such as drug dependency,3 psychosocial factors,4 co-morbid illness,5,6 and knowledge of having an HCV infection.7,8

HRQOL in chronic HCV infection has been primarily assessed in tertiary level treatment settings.1,2,9 Findings from these studies may not reflect morbidity among the broader population of HCV-infected individuals or other sub-populations such as HCV-infected prisoners. The trend towards increased incarceration of individuals represents an important public health problem, partly related to the high prevalence of HCV found in prisoner populations and the high level of related co-morbid physical and mental health conditions.10,11 In New South Wales (NSW), 37% of prisoners are HCV positive. Among those who reported injection drug use, 66% are HCV positive.12,13 However, there is limited information on HRQOL among prisoners. Very little is known about potential HRQOL impairment related to HCV.

In 1996 and 2001, Justice Health (NSW) conducted a wide ranging health survey of the prisoner population, which included screening for a number of infectious diseases and behavioural characteristics. This enabled us to examine HRQOL among this population. The aims of this study were to examine the effect of HCV on prisoners' HRQOL, including that attributable to HCV viremia and to determine the HRQOL effect attributable to being a prisoner, whether HCV positive or negative.

Methods

A cross-sectional health survey among prisoners was conducted by Justice Health (NSW, Australia) in 1996. Prisoners were recruited from 27 male and 2 female correctional centers in NSW. The detailed methods of the survey have been published elsewhere.12 A random sample of prisoners stratified on the basis of age, sex, and indigenous origin was selected from a list of all residents at each correctional center. The overall response rate was 90%. Reasons for non-participation included disillusionment with ‘the system,’ dislike of needles (necessary for blood collection), and imminent release. Each prisoner was called up to three times to attend the health survey. A replacement was selected if they still failed to attend. Court appearances, transfers to other gaols, considered by custodial staff as ‘too dangerous,’ suspected survey was testing for drugs, at work, deported, and all day family visit were some of the reasons for non-attendance. Participants were enrolled in the survey if they provided written informed consent. As many of the prisons are working gaols, participants received $10 compensation to cover possible loss of income. The survey was approved by the Justice Health (NSW) Human Research and Ethics Committee and the NSW Department of Corrective Services Ethics Committee.

Participants underwent an extensive face-to-face structured interview including physical and mental health questionnaires administered by experienced prison health nurses. Information obtained included socio-demographic characteristics, history of illicit drug use, a diagnosis of any medical condition, history of disabling health conditions lasting for 6 months or more, history of symptoms in the 4 weeks prior to the interview, and medical care utilization such as admissions to hospital in the previous 12 months. Levels of co-morbidity were estimated from the self-reported medical conditions (excluding hepatitis virus infection) using the Charlson index.14 A higher Charlson Index score indicates more severe co-morbidity. A 54-item symptom check list, designed to examine the health of opioid users, was used to ascertain symptoms/health complaints in the past 4 weeks.15 The total score for the scale represents the total number of symptoms reported by an individual in the past 4 weeks.

Participants' HRQOL was assessed using the Short-Form (SF-36) Health Survey.16 The 36-item SF-36 measures 8 health domains: physical functioning; role physical; bodily pain; general health; vitality; social functioning; role emotional; and mental health. SF-36 scales were coded using the scoring system that transformed Likert-type scale17 responses for all items to a score on a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better health. Individual scores on each of the SF-36 scales were aggregated using standard algorithms to produce two summary measures, the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS).18 Physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, and general health scales contribute most to PCS measure, while vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health scales contribute most to MCS measure.

Participants' mental health was also assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),19 a 21-item instrument designed to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in the past week. The total BDI score is the sum of the scores on the individual items. A BDI score of 0 to 9 is considered ‘minimal’ or ‘nil’ depression, 10 to 16 ‘mild’ depression, and 17 to 63 ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’ depression.

HCV antibody was detected using the Innotest HCV antibody assay (Innogenetics, Belgium). Reactive samples were tested in duplicate using Murex anti-HCV (Murex, UK). Specimens positive on both assays were classified as positive. Confirmed HCV antibody positive sera were tested for the presence of HCV RNA using Roche Amplicor Assay (Roche Diagnostics, Sydney, Australia).

A sub-group of prisoners underwent repeat HCV antibody testing and physical and mental health survey in 2001. A seroconverter was defined as an individual who tested negative for HCV antibody in 1996 but tested positive in 2001. The measures of health status and HRQOL employed in the 1996 survey20 were also used in the 2001 survey.

Statistical Analysis

Of the 789 prisoners recruited, 690 prisoners were included for statistical analysis. Ninety-nine participants were excluded from the analysis: 41 without HCV antibody testing; nine with discrepant HCV antibody results classified as equivocal; one who tested positive for HCV antibody but was not tested for HCV RNA; and 48 who did not complete the physical and mental health survey. Eligible participants were grouped into three categories for comparison purposes: (1) HCV antibody negative; (2) HCV antibody positive/non-viremic; and (3) HCV antibody positive/viremic. Comparison of socio-demographic characteristics, illicit drug use, health status, and medical care utilization between these groups were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables or Fisher’s exact test if any of the expected frequencies is less than five and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for linear variables or Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA for non-linear variables.

The internal consistency of BDI and SF-36 scores were assessed using Cronbach's alpha.21 There were few (less than 2%) missing values for SF-36 scores or BDI scores, so we did not feel it was important to replace them. Group comparisons of the mean SF-36 scores were made using ANOVA with post-hoc pairwise comparisons applying Bonferroni adjustments that compensate for multiple testing.22 BDI scores and the severity of depressive symptoms were compared between groups using Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA and chi-squared test. Factors significantly associated with PCS and MCS in the univariate analyses (with an inclusion criteria of P ≤ 0.2) and factors that were considered a priori to be mediators or modulators of HRQOL were then entered into multivariate linear regression models using the forward selection method. Group differences in HRQOL were also assessed using ANCOVA adjusting for significant confounding factors including age, sex, injecting drug use, co-morbidity, presence of a chronic disabling condition, symptoms, previous hospital admission, and severity of depressive symptoms. Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean SF-36 scores between the groups and the age-standardized Australian population norms.23

Differences in the mean SF-36 scores between 1996 and 2001 for each group of prisoners (i.e., HCV antibody negative, HCV antibody positive/non-viremic, HCV antibody positive/viremic, and HCV seroconverters) were assessed using ANCOVA adjusting for the pattern of imprisonment (i.e., continuous or recidivist). Measures of effect size (Cohen’s d)24,25 were calculated between 1996 and 2001 to determine the magnitude of differences in mean SF-36 scores. We used Cohen's classification of effect size (small = .20, medium = .50, large = .80).25 A two-tailed P value less than .01 was considered significant for all comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 8.2 (Stata Corporation 1984–2003).

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics of the HCV antibody negative (n = 423), HCV antibody positive/non-viremic (n = 89), and HCV antibody positive/viremic (n = 178) groups are shown in Table 1. The socio-demographic characteristics and reporting of injecting drug use of the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic and viremic groups were similar. HCV antibody positive groups were younger (mean age 30–31 vs. 36 years), more often female (25–26 vs. 8%), more likely to be unemployed prior to incarceration (67–73 vs. 50%), more likely to report longer duration of drug injection (11 vs. 5 years), and more likely to report drug injection in prison (49–55 vs. 8%) than the HCV antibody negative group.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, history of injecting drug use, self-reported health status and medical care utilization of prisoners (percentages) by HCV status

| Characteristics | HCV Ab− | HCV Ab+/non-viremic | HCV Ab+/viremic | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 423 | N = 89 | N = 178 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 92.2 | 74.2 | 74.7 | <.001 |

| Age (mean±SD) years | 35.5 (13.7) | 31.0 (8.2) | 30.2 (7.6) | <.001 |

| Indigenous origin | 31.9 | 31.5 | 24.2 | .2 |

| Education level* | ||||

| Nil to education with no qualification | 47.0 | 59.6 | 59.0 | |

| With qualification | 51.8 | 39.3 | 39.9 | .05 |

| Employment 6 months before imprisonment* | ||||

| No | 49.6 | 73.0 | 67.4 | |

| Yes | 49.9 | 25.8 | 32.0 | <.001 |

| Duration in prison | ||||

| Less than 1 year | 52.3 | 51.7 | 61.2 | |

| One or more years | 47.7 | 48.3 | 38.8 | .1 |

| History of ever injecting drug use* | ||||

| No | 65.5 | 9.0 | 6.7 | |

| Yes | 21.0 | 84.3 | 90.5 | <.001 |

| Duration of drug injection (median, IQR) | 5 (3–9) | 11 (7–16) | 11 (6–16) | <.001 |

| Drug injection in prison* | ||||

| No | 87.9 | 41.6 | 40.4 | |

| Yes | 7.8 | 49.4 | 55.1 | <.001 |

| Frequency of drug injection last month | N = 11 | N = 11 | N = 26 | |

| Daily or more | 90.9 | 100 | 92.3 | |

| Less than daily | 9.1 | .0 | 7.7 | 1.0 |

| Ever told by a doctor of having hepatitis C* | ||||

| No | 96.9 | 31.5 | 25.8 | |

| Yes | 1.2 | 66.3 | 71.4 | <.001 |

| Medical conditions* | ||||

| Arthritis | 18.9 | 13.5 | 11.2 | .1 |

| Respiratory disease (e.g., asthma) | 17.7 | 32.6 | 20.2 | .01 |

| Cancer | 4.3 | 4.5 | 5.6 | .9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.3 | .0 | 2.8 | .2 |

| Cardiac disease | 25.8 | 20.2 | 18.5 | .2 |

| High blood pressure | 15.6 | 7.9 | 7.3 | .02 |

| Peptic ulcer | 9.9 | 11.2 | 7.3 | .8 |

| HIV positive | .3 | 1.2 | 2.4 | .01 |

| Charlson co-morbidity index score† | ||||

| 0–1 | 69.7 | 77.5 | 78.7 | |

| >1 | 30.3 | 22.5 | 21.3 | .05 |

| Disabling condition lasting ≥6 months | 32.4 | 37.1 | 34.8 | .6 |

| Symptoms past 4 weeks* | ||||

| None | 13.7 | 12.4 | 11.8 | |

| 1–2 | 22.9 | 19.1 | 21.9 | |

| 3 or more | 63.1 | 68.5 | 66.3 | .9 |

| Hospital admission past 12 months | ||||

| No | 82.7 | 75.3 | 76.4 | |

| Yes | 17.3 | 24.7 | 23.6 | .1 |

| Depression severity‡(%) | ||||

| Minimal/nil (0–9) | 59.8 | 53.9 | 59.6 | |

| Mild (10–16) | 23.9 | 25.8 | 15.7 | |

| Moderate to severe (17–63) | 14.4 | 16.9 | 23.6 | .04 |

HCV Ab− HCV antibody negative prisoners, HCV Ab+/non-viremic HCV antibody positive/non-viremic prisoners; HCV Ab+/non-viremic HCV antibody positive/viremic prisoners.

*Percentages include participants who did not report.

†A measurement of co-morbidity where a higher score reflects more severe co-morbidity.14

‡Based on Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score.

Self-Reported Health and Mood Status

The majority of HCV antibody positive/non-viremic (66%) and viremic (71%) individuals reported that they had been told of their HCV status (Table 1). There was a trend towards a lower level of co-morbidity among HCV antibody positive groups compared with HCV antibody negative prisoners (Charlson co-morbidity index score >1:21–23 vs. 30%, P = 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in reported health status and medical care utilization between HCV antibody positive/non-viremic and viremic groups.

The internal consistency reliability of BDI scores ranged between .85–.87. Median depression scores were similar between the groups (HCV antibody negative: 7; HCV antibody positive/non-viremic: 8; HCV antibody positive/viremic: 8, P = 0.3). However, the proportion of prisoners reporting ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’ depressive symptoms was greater in the HCV antibody positive/viremic group than the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic group (24 vs. 17%, P = 0.2) or the HCV antibody negative group (24 vs. 14%, P = 0.02) (Table 1).

Health-Related Quality of Life

Mean SF-36 score differences were found between groups in the MCS (P = 0.009) and its sub-scale, role emotional (P = 0.002, Table 2). Pairwise comparisons showed a trend towards significant difference between the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic group and the HCV antibody negative group in the MCS score (43.8 vs. 47.8, P = 0.016) and a significantly lower MCS sub-scale score, limitations due to role emotional (65.2 vs. 80.1, P = 0.002). However, no significant differences were found in the mean SF-36 scores between the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic and viremic groups.

Table 2.

HRQOL scores of prisoners by HCV status and uninfected Australian population

| SF-36 scores (mean+SD) | Australian norms23 | Prisoners | P value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV Ab− | HCV Ab+/non-viremic | HCV Ab+/viremic | |||

| N = 18,468 | N = 423 | N = 89 | N = 178 | ||

| Physical functioning | 82.5 (23.9) | 88.3 (20.6) | 88.3 (19.7) | 91.5 (15.6) | .2 |

| Role physical | 79.8 (35.1) | 80.4 (34.2) | 77.2 (38.9) | 74.8 (39.8) | .2 |

| Bodily pain | 76.8 (25.0) | 76.8 (26.4) | 72.7 (30.4) | 73.9 (26.3) | .3 |

| General health | 71.6 (20.3) | 69.7 (22.3) | 66.6 (22.5) | 67.5 (21.9) | .3 |

| Vitality | 64.5 (19.8) | 64.4 (23.7) | 62.7 (22.6) | 61.3 (23.4) | .3 |

| Social functioning† | 84.9 (22.5) | 80.4 (26.0) | 74.6 (28.2) | 76.2 (25.8) | .07 |

| Role emotional | 82.8 (32.3) | 80.1 (35.9) | 65.2 (43.5) | 73.8 (39.8) | .002 |

| Mental health | 75.9 (17.0) | 69.9 (22.2) | 65.2 (20.9) | 68.4 (21.2) | .2 |

| Physical component summary† | 49.7 (10.2) | 53.0 (9.3) | 53.3 (9.7) | 52.8 (8.6) | .9 |

| Mental component summary† | 50.1 (10.0) | 47.8 (12.3) | 43.8 (12.6) | 45.7 (12.0) | .009 |

Age-standardized Australian norms;23 Unadjusted mean SF-36 scores: higher scores indicate better health

HRQOL health-related quality of life, SD standard deviation

*P value for ANOVA between groups; post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments between HCV antibody positive/non-viremic and HCV antibody negative: role emotional (P = .002); mental component summary (P = .016)

†HCV antibody negative (N = 419); HCV antibody positive/non-viremic (N = 89); HCV antibody positive/viremic (N = 176)

Univariate analyses showed that poor HRQOL was associated with presence of HCV infection, older age, female sex, history of drug injection in prison, co-morbidity, chronic disabling conditions or systemic symptoms (Tables 3 and 4). In addition, recent history of admission to hospital and severity of depressive symptoms were also associated with poorer HRQOL.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses of factors associated with PCS score in prisoners

| Variables | N | Physical component summary score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | ||

| HCV status | |||||||

| HCV antibody negative | 419 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| HCV antibody positive/non-viremic | 89 | .01 | 1.07 | .8 | .04 | 1.16 | .4 |

| HCV antibody positive/viremic | 176 | −0.01 | .83 | .9 | .01 | 1.05 | .8 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 584 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Female | 100 | −.14 | .99 | <.001 | −.05 | .91 | .2 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <25 | 229 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 25–40 | 262 | −.08 | .80 | .05 | −.05 | .73 | .2 |

| >40 | 193 | −.31 | .86 | <.001 | −.20 | .82 | <.001 |

| Education | |||||||

| Without qualification | 353 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| With qualification | 323 | −.01 | .71 | .7 | .05 | .61 | .1 |

| Not reported | 8 | .04 | 3.29 | .3 | .02 | 2.77 | .5 |

| Drug injection in prison | |||||||

| No | 476 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 174 | −.02 | .81 | .6 | −.02 | .84 | .6 |

| Not reported | 34 | .06 | 1.63 | .1 | .08 | 1.45 | .02 |

| Knowledge about having hepatitis C | |||||||

| No | 479 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 190 | −.05 | .79 | .2 | −.05 | 1.04 | .4 |

| Not reported | 15 | −.04 | 2.41 | .3 | −.02 | 2.07 | .5 |

| Co-morbidity | |||||||

| Charlson 0–1 | 499 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Charlson >1 | 185 | −.35 | .74 | <.001 | −.15 | .76 | <.001 |

| Chronic disabling condition | |||||||

| No | 455 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 229 | −.42 | .68 | <.001 | −.28 | .69 | <.001 |

| Symptoms past 4 weeks | |||||||

| None | 90 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1–2 | 151 | −.10 | 1.16 | .06 | −.04 | 1.04 | .4 |

| 3 or more | 442 | −.38 | 1.01 | <.001 | −.21 | .94 | <.001 |

| Not reported | 1 | −.06 | 8.79 | .1 | −.04 | 7.80 | .3 |

| Hospital admission past 12 months | |||||||

| No | 547 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 137 | −.22 | .86 | <.001 | −.13 | .78 | <.001 |

| Depression severity | |||||||

| Minimal/nil | 404 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mild | 150 | −.10 | .87 | .009 | −.01 | .77 | .7 |

| Moderate to severe | 117 | −.12 | .96 | .002 | .03 | .86 | .5 |

| Not reported | 13 | .01 | 2.57 | .7 | −.00 | 2.26 | .9 |

The analysis included 684 prisoners.

PCS Physical component summary; β standardized regression coefficient; SE standard error.

Adjusted r2 = .30

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses of factors associated with MCS score in prisoners

| Variables | N | Mental component summary score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | ||

| HCV status | |||||||

| HCV antibody negative | 419 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| HCV antibody positive/non-viremic | 89 | −.11 | 1.43 | .005 | −.03 | 1.46 | .5 |

| HCV antibody positive/viremic | 176 | −.07 | 1.10 | .06 | .05 | 1.33 | .3 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 584 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Female | 100 | −.18 | 1.31 | <.001 | −.08 | 1.14 | .02 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <25 | 229 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 25–40 | 262 | −.02 | 1.11 | .7 | .02 | .91 | .5 |

| >40 | 193 | .12 | 1.20 | .007 | .11 | 1.03 | .004 |

| Education | |||||||

| Without qualification | 353 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| With qualification | 323 | .02 | .95 | .7 | .00 | .77 | .9 |

| Not reported | 8 | −.00 | 4.41 | .9 | −.03 | 3.49 | .3 |

| Drug injection in prison | |||||||

| No | 476 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 174 | −.17 | 1.08 | <.001 | −.07 | 1.05 | .08 |

| Not reported | 34 | −.07 | 2.16 | .06 | −.03 | 1.82 | .4 |

| Knowledge about having hepatitis C | |||||||

| No | 479 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 190 | −.13 | 1.05 | <.001 | −.02 | 1.31 | .7 |

| Not reported | 15 | −.02 | 3.20 | .7 | .04 | 2.61 | .2 |

| Co-morbidity | |||||||

| Charlson 0–1 | 499 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Charlson >1 | 185 | −.12 | 1.05 | .002 | .02 | .96 | .5 |

| Chronic disabling condition | |||||||

| No | 455 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 229 | −.12 | .99 | .002 | −.01 | .87 | .7 |

| Symptoms past 4 weeks | |||||||

| None | 90 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1–2 | 151 | −.06 | 1.58 | .3 | −.05 | 1.31 | .3 |

| 3 or more | 442 | −.32 | 1.37 | <.001 | −.16 | 1.19 | <.001 |

| Not reported | 1 | −.04 | 11.91 | .2 | −.06 | 9.82 | .05 |

| Hospital admission past 12 months | |||||||

| No | 547 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 137 | −.19 | 1.16 | <.001 | −.07 | .98 | .04 |

| Depression severity | |||||||

| Minimal/nil | 404 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mild | 150 | −.26 | .96 | <.001 | −.23 | .96 | <.001 |

| Moderate to severe | 117 | −.59 | 1.05 | <.001 | −.54 | 1.08 | <.001 |

| Not reported | 13 | −.04 | 2.83 | .2 | −.04 | 2.85 | .3 |

The analysis included 684 prisoners.

MCS Mental component summary, β standardized regression coefficient, SE standard error

Adjusted r2 = .38

In the multivariate linear regression analyses, age, co-morbidity, chronic disabling condition, recent history of systemic symptoms and admission to hospital remained as independent predictors of impaired physical health summary measure (Table 3), whereas recent history of systemic symptoms and severity of depressive symptoms were independent predictors of impaired mental health summary measure (Table 4). Borderline significant associations were found between mental health summary measure and female sex and recent history of admission to hospital. There were no HRQOL differences attributable to HCV infection apparent in the multivariate analyses, which controlled for confounders.

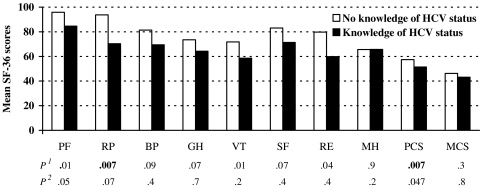

Although univariate analyses revealed significant differences in SF-36 scores between HCV infected and uninfected groups, there were no significant differences when adjusted for confounders. The effect of knowledge of HCV status was assessed in the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic group (Fig. 1). Prisoners who believed they had HCV infection had significantly lower PCS score and lower PCS sub-scale score, limitations due to role physical, than those who believed they did not have HCV infection. However, none of these scale scores remained significantly different after adjustment for sex, age, and co-morbidity.

Figure 1.

HRQOL among HCV antibody positive/non-viremic prisoners by knowledge of HCV status. Unadjusted mean SF-36 scores. Higher scores indicate better health. No knowledge of HCV status (n = 28); knowledge of HCV status (n = 59). PF Physical functioning, RF role physical, BP bodily pain, GH general health, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE role emotional, MH mental health, PCS physical component summary, MCS mental component summary, P1 unadjusted, P2 adjusted for age, sex, and self-reported co-morbidity

Compared to age-standardized Australian population norms,23 the HCV antibody negative prisoners had significantly lower scores in MCS (50.1 vs. 47.8, P < 0.001) and two of eight SF-36 domains (i.e., social functioning and mental health), whereas the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic (50.1 vs. 43.8, P < 0.001) and viremic (50.1 vs. 45.7, P < 0.001) groups had significantly lower scores in MCS and four of eight SF-36 domains (i.e., general health, social functioning, role emotional and mental health).

Temporal Change in HRQOL

Eighty-seven HCV antibody negative, 23 HCV antibody positive/non-viremic, 40 HCV antibody positive/viremic, and 13 HCV seroconverters (HCV antibody negative 1996, antibody positive 2001) completed a second SF-36 Health Survey in 2001. There were no significant differences in the adjusted mean PCS scores between 1996 and 2001 in all groups: HCV antibody negative, 54.5 vs. 53.7, P = 0.5; HCV antibody positive/non-viremic, 53.4 vs. 50.8, P = 0.4,; HCV antibody positive/viremic, 50.6 vs. 51.5, P = 0.7; seroconverters 57.1 vs. 53.7, P = 0.2. Notably, the seroconverter group had a lower mean general health score in 2001 compared to 1996, with a medium effect size (73.7 vs. 86.1, P = 0.08, d = −0.72). There were also no significant differences in the mean MCS scores between the two time points in all groups (HCV antibody negative: 47.5 vs. 51.5, P = 0.02; HCV antibody positive/non-viremic: 47.6 vs. 51.7, P = 0.2; HCV antibody positive/viremic: 45.5 vs. 42.4, P = 0.2; seroconverters: 48.0 vs. 50.7, P = 0.6).

Discussion

In this population-based study among prisoners, we were unable to demonstrate a measurable impact of HCV infection on HRQOL, with no greater impairment in HRQOL in HCV antibody positive prisoners compared to those without HCV antibody. Furthermore, there was no evidence of greater impairment in HRQOL in the HCV viremic compared to HCV non-viremic individuals. However, the prevalence of ‘moderate’ to ‘severe’ depressive symptoms was greater in the HCV antibody positive/viremic group than the HCV antibody positive/non-viremic group or the HCV antibody negative group. Compared to uninfected Australian population norms,23 all prisoner groups had lower SF-36 scores. Several non-HCV related factors, such as age, co-morbidity, severity of depressive symptoms and medical care utilization, independently predicted impaired physical and mental health.

Our study has several limitations. First, the largely cross-sectional study design, with no HCV-specific aspects examining HRQOL incorporated within the instruments, may have limited examination of HCV-related HRQOL among prisoners. Second, the sample size of the group with repeat assessments in 2001 may have been too small to detect significant HRQOL differences. Third, physical health of prisoners may not have been adequately assessed using the SF-36 health measure as the prison environment may not encompass some aspects of the SF-36, such as climbing several flights of stairs, walking several blocks or walking more than a mile. However, the internal consistency reliability of SF-36 scores (>0.70) was good to detect HRQOL differences.26 Fourth, the possibility of interviewer bias could not be determined. Although the direction of the bias is not known, the standardized health measures27 used should minimise such bias.

The history of HCV treatment was also not sought in this study, but due to strict eligibility criteria in Australia prior to May 2001, including exclusion of individuals with a history of injecting drug use in the previous 12 months, it is unlikely that many prisoners would have accessed such treatment in 1996.28 Finally, although prisoners were sampled from all correctional centers in NSW, the state with the largest prisoner population in Australia, the findings may not be generalizable to other jurisdictions, particularly those outside Australia.

Considerable evidence exists to support the presence of HCV-related HRQOL impairment,1,3,29 including HRQOL improvements with sustained virological response following HCV treatment.2,9,29 Potential explanations for HRQOL impairment among people with HCV include direct viral effects, inability to disentangle the effects of HCV infection from concomitant co-morbidities, including the effects of injecting drug use, and the psychological impact of HCV diagnosis. Proposed mechanisms of direct viral effects on HRQOL include neurotropic effects (“brain fog”) of HCV30,31 through peripheral or central cytokine release32 or possibly from primary central nervous system infection.33,34

Although univariate analyses revealed differences in HRQOL scores between infected and uninfected groups, multivariate adjustments for the many differences in confounding variables between groups yielded scores for infected and uninfected groups that were quite similar. The lack of an HCV effect on HRQOL in our study in contrast to those found in treatment settings1,2,9 may relate to the more stringent controlling of confounders. Furthermore, current injecting drug users, individuals on drug dependency, and individuals with psychiatric co-morbidity, in particular major depression, are usually excluded from participation in clinical trials. It is possible that the impact of HCV depends on the extent of co-morbidities. For example, the impact of HCV may be evident among individuals with absence of co-morbidities but overridden among individuals with significant co-morbidities.35 Furthermore, in treatment settings, HRQOL improvement in individuals due to knowledge of treatment-induced sustained virological response cannot be discounted. Our findings are consistent with a recent study from Egypt,36 in which the authors reported that several demographic and health care-related factors significantly influenced HRQOL, confounding the association between HCV infection and HRQOL. In both studies, impaired HRQOL was associated with recent history of admission to hospital, self-declared non-HCV chronic disease, female sex, and older age. Additionally, in our study, recent history of systemic symptoms and severity of depressive symptoms independently predicted impaired mental health.

Few HRQOL studies have compared HCV viremic and non-viremic individuals blinded to their HCV RNA status.7 Most studies compare the HRQOL of individuals with established chronic HCV infection and population-based controls.1–3,5,6,9 In agreement with a recent study among active injecting drug users,7 we found no greater HRQOL effect attributed to HCV viremia. Our study and these other two studies are similar in terms of the HRQOL instrument employed (SF-36 or SF-12) and the sampling of populations with considerable co-morbidity and finding no evidence of a direct HCV impact on HRQOL.7,36 Potential explanations for the lack of an HCV effect on HRQOL across these studies are relatively larger effects of co-morbid conditions, lack of HCV sensitivity in the SF-36 and SF-12 surveys, and adequate controlling for potential confounding factors.

Approximately one-third of HCV infected prisoners in our study were unaware of their HCV status. A marginal effect of knowledge of HCV status on HRQOL was seen among the HCV positive/non-viremic group, in whom physical functioning and PCS scores were lower among individuals aware of their HCV positive status than those not. This is consistent with those found in cohort studies,8 active injecting drug users attending a needle exchange program,7 and blood donors undergoing medical process.37

In our study, irrespective of HCV status, prisoners had lower HRQOL in most health domains of the SF-36 and the mental health summary measures than the age-standardized Australian population norms or those with a single serious physical condition.23 Although prisoners had greater HRQOL impairment than the general population, predictive factors for impairment appear similar. Age and co-morbidity were associated with PCS score, while age and depression severity were associated with MCS score. These associations have been reported in studies of HRQOL among general population groups.38 The greater impairment in HRQOL among prisoners may therefore relate to a higher prevalence of co-morbidity and depression.

In summary, although we found no direct impact of HCV on HRQOL, our findings highlight the poor health status of prisoners in NSW. This may reflect the incarceration of individuals with established HRQOL impairment and/or a specific impact of incarceration on HRQOL. Previous studies have documented high levels of drug dependency and co-morbid physical and mental health conditions among prisoner populations.10,11,39 However, our study was unable to assess the specific impact of incarceration on HRQOL. The association between depression and HRQOL and the relatively high prevalence of moderate to severe depression among our study population demonstrate the importance of developing management strategies for improving both physical and mental health among prisoners.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, The University of New South Wales. Justice Health (NSW) provided the data used in the analysis.

Footnotes

Thein, Kaldor, and Dore are with the National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Butler and Levy are with the Centre for Health Research in Criminal Justice, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Butler is with the School of Public Health and Community Medicine, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Krahn is with the Departments of Medicine and Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Rawlinson is with the Virology Division SEALS Prince of Wales Hospital, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Presented in part: 2nd Prisoners Health Research Symposium, February 2005, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. 4th Australian Hepatitis C Conference, August 2004, Canberra, Australia.

References

- 1.Bonkovsky HL, Woolley JM. Reduction of health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C and improvement with interferon therapy. The Consensus Interferon Study Group. Hepatology. 1999;29:264–270. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, Mannocchia M, Davis GL. Health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C: impact of disease and treatment response. The Interventional Therapy Group. Hepatology. 1999;30:550–555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Foster GR, Goldin RD, Thomas HC. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection causes a significant reduction in quality of life in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:209–212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Fontana RJ, Hussain KB, Schwartz SM, Moyer CA, Su GL, Lok AS. Emotional distress in chronic hepatitis C patients not receiving antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2002;36:401–407. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Fontana RJ, Moyer CA, Sonnad S, et al. Comorbidities and quality of life in patients with interferon-refractory chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:170–178. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hussain KB, Fontana RJ, Moyer CA, Su GL, Sneed-Pee N, Lok AS. Comorbid illness is an important determinant of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2737–2744. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Dalgard O, Egeland A, Skaug K, Vilimas K, Steen T. Health-related quality of life in active injecting drug users with and without chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2004;39:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Rodger AJ, Jolley D, Thompson SC, Lanigan A, Crofts N. The impact of diagnosis of hepatitis C virus on quality of life. Hepatology. 1999;30:1299–1301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.McHutchison JG, Ware JE Jr, Bayliss MS, Pianko S, Albrecht JK, Cort S, Yang I, et al. The effects of interferon alpha-2b in combination with ribavirin on health related quality of life and work productivity. J Hepatol. 2001;34:140–147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Butler T, Allnutt S, Cain D, Owens D, Muller C. Mental disorder in the New South Wales prisoner population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:407–413. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Butler T, Milner L. The 2001 Inmate Health Survey. 2003. Sydney: NSW Corrections Health Service. ISBN: 0 7347 3560 X.

- 12.Butler T, Spencer J, Cui J, Vickery K, Zou J, Kaldor J. Seroprevalence of markers for hepatitis B, C and G in male and female prisoners—NSW, 1996. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1999;23:377–384. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Butler TG, Dolan KA, Ferson MJ, McGuinness LM, Brown PR, Robertson PW. Hepatitis B and C in New South Wales prisons: prevalence and risk factors. Med J Aust. 1997;166:127–130. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie RC. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Darke S, Ward J, Zador D, Swift G. A scale for estimating the health status of opioid users. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1317–1322. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psych. 1932;140:5–55.

- 18.Ware JE, Konsinski M. SF-36®Physical & Mental Health Summary Scales: a Manual for Users of Version 1. 2nd ed. Lincoln, Rhode Island: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2001.

- 19.Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, New York: Guildford; 1979.

- 20.Butler T, Kariminia A, Levy M, Kaldor J. Prisons are a risk for hepatitis C transmission. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Cronbach LJ, Warrington WG. Time-limit tests: estimating their reliability and degree of speeding. Psychometrika. 1951;16:167–188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. 1st ed. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991.

- 23.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). National Health Survey: SF-36 population norms. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service; 1997.

- 24.Howell DC. Statistical Methods for Psychology. 5th ed. California: Thomson Learning; 2002.

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Academic; 1988.

- 26.Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

- 27.Ware JE Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, Massachusetts: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993.

- 28.Matthews G, Kronborg IJ, Dore GJ. Treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among current injection drug users in Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(Suppl 5):S325–S329. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Spiegel BM, Younossi ZM, Hays RD, Revicki D, Robbins S, Kanwal F. Impact of hepatitis C on health related quality of life: a systematic review and quantitative assessment. Hepatology. 2005;41:790–800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Forton DM, Thomas HC, Murphy CA, Allsop JM, Foster GR, Main J, Wesnes KA, et al. Hepatitis C and cognitive impairment in a cohort of patients with mild liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Forton DM, Allsop JM, Main J, Foster GR, Thomas HC, Taylor-Robinson SD. Evidence for a cerebral effect of the hepatitis C virus. Lancet. 2001;358:38–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Fiala M, Looney DJ, Stins M, et al. TNF-alpha opens a paracellular route for HIV-1 invasion across the blood–brain barrier. Mol Med. 1997;3:553–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Forton D, Taylor-Robinson S, Karayiamnis P, Thomas H. Identification of brain-specific quasispecies variants of hepatitis C virus (HCV) consistent with viral replication in the central nervous system. Hepatology. 2000;32(Suppl):269A. [DOI]

- 34.Thomas HC, Torok ME, Forton DM, Taylor-Robinson SD. Possible mechanisms of action and reasons for failure of antiviral therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1999;31(Suppl 1):152–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, van den Bos GA. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:661–674. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Schwarzinger M, Dewedar S, Rekacewicz C, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection: does it really impact health-related quality of life? A study in rural Egypt. Hepatology. 2004;40:1434–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cordoba J, Reyes J, Esteban JI, Hernandez JM. Labeling may be an important cause of reduced quality of life in chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:226–227. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Michelson H, Bolund C, Brandberg Y. Multiple chronic health problems are negatively associated with health related quality of life (HRQoL) irrespective of age. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Mooney M, Hannon F, Barry M, Friel S, Kelleher C. Perceived quality of life and mental health status of Irish female prisoners. Ir Med J. 2002;95:241–243. [PubMed]