Abstract

Despite the considerable resources that have been dedicated to HIV prevention interventions and services over the past decade, HIV incidence among young people in the United States remains alarmingly high. One reason is that the majority of prevention efforts continue to focus solely on modifying individual behavior, even though public health research strongly suggests that changes to a community's structural elements, such as their programs, practices, and laws or policies, may result in more effective and sustainable outcomes. Connect to Protect is a multi-city community mobilization intervention that focuses on altering or creating community structural elements in ways that will ultimately reduce youth HIV incidence and prevalence. The project, which spans 6 years, is sponsored by the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions at multiple urban clinical research sites. This paper provides an overview of the study's three phases and describes key factors in setting a firm foundation for the initiation and execution of this type of undertaking. Connect to Protect's community mobilization approach to achieving structural change represents a relatively new and broad direction in HIV prevention research. To optimize opportunities for its success, time and resources must be initially placed into laying the groundwork. This includes activities such as building a strong overarching study infrastructure to ensure protocol tasks can be met across sites; tapping into local site and community expertise and knowledge; forming collaborative relationships between sites and community organizations and members; and fostering community input on and support for changes at a structural level. Failing to take steps such as these may lead to insurmountable implementation problems for an intervention of this kind.

Keywords: Community mobilization, HIV, Structural change, Youth

Introduction

It is estimated that at least half of all new HIV infections in the United States and worldwide are among people under 25 years of age; the vast majority of these infections occur through sexual activity.1,2 In the United States, between 2001 and 2004, the estimated number of individuals living with HIV and AIDS increased for those between the ages of 15 and 24, while HIV/AIDS cases remained the same or decreased for other age groups (25–29 and 30–49 years).3 Calculations show that the proportion of young people diagnosed with AIDS has increased from 3.9% in 1999 to 5.1% in 2004.3,4

As HIV/AIDS continues to proliferate in the adolescent and young adult populations in the United States, its spread continues to be predominant among heterosexual young women of color and young men who have sex with men (YMSM).3 These are populations that often lack social power and face oppression in the form of sexism, racism, and heterosexism.5–9 In 2003, only 15% of the adolescent population in the United States was estimated to be African American and 16% Latino/a; yet, approximately two-thirds of 13 to 19 years olds living with AIDS were African American and 21% Latino/a.4 In a cross-sectional study of YMSM between the ages of 15 and 22 in seven metropolitan communities, overall HIV seroprevalence was 7.2% with a range across the communities from 2.2 to 12.2%.10,11 These rates were higher among African American (OR=6.3) and Latino (OR=2.3) youth, as compared to White youth (referent group), demonstrating seroprevalence rates of 14% for African Americans and 7% for Latinos. Other recent studies of urban youth have corroborated findings of higher HIV seroprevalence rates among YMSM of color, with rates for African Americans ranging from nine to 12 times those for Whites.12,13

A review of published, well-controlled intervention studies aimed at decreasing the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among adolescents suggests that programs focused on individual behavior (e.g., condom use) can reduce HIV/STI risk-associated behavior and theory-based determinants of such behavior.14–18 It remains unclear, however, whether the effects are sustainable for the long term. Most studies would suggest that they are not. To enhance opportunities for long-term sustainability, intervention activities cannot be aimed solely at changing individual behavior; they must also work to change the structural features of a community—such as its programs, practices, and laws or policies—that place certain groups of people at increased risk of becoming infected.19–23

Despite a call for HIV prevention interventions at the structural level, this method is clearly underutilized in the United States as a way of thwarting the spread of infection among adolescents.23 This may be partially due to the increased time, cost, and complexity associated with developing and implementing such interventions. A structural approach requires not only a shift in the current practice and funding of HIV prevention research, but also the use of alternative research designs and implementation of social change strategies borrowed from other disciplines.23,24 In addition, the process of building and maintaining successful relationships between researchers and community members and agencies, which is critical to achieving and sustaining structural change, is often complicated and requires a variety of resources.24,25

The project described in this paper, Connect to Protect (C2P): Partnerships for Youth Prevention Interventions, reflects this new generation of research. C2P employs scientific principles related to community mobilization, community capacity building, and community involvement to attempt structural changes that are expected to ultimately lead to decreased rates of HIV. The study is supported by the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Intervention (ATN) at research sites in multiple urban areas. The ATN, a network of adolescent medicine health specialists funded under a cooperative agreement with the National Institutes of Health, conducts research on youth who are at risk for, or are living with, HIV infection. Sites that have taken part in C2P activities thus far include those located in Baltimore, Boston, Bronx (New York), Chicago, Ft. Lauderdale, Manhattan (New York), Los Angeles, Miami, New Orleans, Philadelphia, San Diego, San Francisco, San Juan (Puerto Rico), Tampa, and Washington, DC. Metropolitan areas are the focus of this study because they are the geographic regions with the highest rates of HIV infection among youth. The specific communities that are part of this study reflect a diverse array of urban populations and include those youth subpopulations at highest risk for the infection, such as African American and Latina heterosexual females and YMSM.

To ensure fidelity to the research protocol and facilitate project implementation across all sites, C2P built a unique study infrastructure that involves a central administrative entity. This administrative infrastructure, along with local site and community expertise and collaboration, provides the necessary foundation to successfully initiate and guide a study of this scale and complexity within many distinct and dynamic cities.

Theoretical Foundations: Structural Change and Community Mobilization

Structural Change Related to HIV Acquisition and Transmission

Structural level determinants are features of the environment that typically exist outside of individual participation or control. They are essentially built into the surroundings, thus creating the structure of the environment within which people operate.26–29 Individuals may not even be aware of the influence these factors have on their interactions, behaviors or exposure to HIV. “Macro-structural determinants” drive the epidemic. They are socio-economic conditions such as poverty, gender inequality, racial oppression, and mobility.21,22,28–33 While exact mechanisms linking such determinants to HIV transmission are difficult to identify, clearly the impact of these broad social forces produces a disproportionate spread of disease.20,28,33 Rooted in these conditions are “intermediate-structural determinants.” They encompass the availability of resources, physical structures in the environment, organizational structures, and laws and policies.27,29,33,34 While addressing macro-level determinants may ultimately be necessary, intermediate-level ones are, in general, more tangible and feasible to alter.29 Thus, they make excellent targets for change.

C2P's intervention focuses on intermediate-structural elements such as programs, practices, and laws and policies that are believed to be associated with HIV risk among youth. While the discourse surrounding structural change is constantly evolving, one proposition is that structural change can impact health via availability, accessibility and acceptability.27 Structural changes to programs generally improve the availability, accessibility, or acceptability of resources. As applied to HIV prevention, they may come in different forms ranging from health and social services to the provision of condoms and clean needles.34Practices are generally defined as a particular way of doing things, such as how a school system operates or the ways in which coverage is offered by a health insurance company.35 New or modified practices can improve the effectiveness of an organizational structure to better address the determinants of HIV acquisition and transmission. Laws and policies are defined as written or unwritten guidelines that regulate the environment and individuals within that environment.35 Existing laws and policies can themselves be structural determinants that influence the transmission of HIV, like prohibiting the sale and distribution of sterile injection equipment, which in turn may increase the likelihood of needle sharing.36

Community Mobilization and HIV Prevention

One methodological approach to facilitating structural change is through community mobilization. In this context, community mobilization typically refers to the organization of communities for the purpose of developing and implementing programs that address a specific prevention effort.37 It involves various segments or sectors of the community coming together to identify common problems, set goals, pool resources, and take action on shared concerns.38 One essential component of community mobilization that has been highlighted by several authors is the empowerment of and collaboration among grassroots organizations and community members who have a common interest in the targeted issue.39,40

Community mobilization efforts for adolescent health issues have predominately focused on decreasing or eliminating the use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Such interventions have been implemented in the United States as well as in Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Brazil, and Bolivia.41–45 A number of these studies have used models that focus on recruiting key opinion leaders and other community leaders to work together. Others also emphasize the importance of involving existing community agencies and building capacity in organizations so improvements have a better chance of being sustained.46

These interventions have been somewhat limited in that most have implemented standardized programs and/or brought about structural changes related to access to substances, and few have been rigorously evaluated.47–50 In one of the few studies that reported outcome data, a substance use prevention intervention that included church community mobilization involving parent and youth training, early intervention services, and case management was implemented in five communities over 5 years.42 Repeated measures gathered over a one-year period in each community revealed that the program moderated effects of the onset and frequency of alcohol and other drug use among high-risk youth between the ages of 12 and 14.42

Such community mobilization interventions have not been widely used to try to lower youth HIV infection rates. Focusing on adolescent sexual activity involves a set of challenges that are different from those for substance use, perhaps particularly when attempting to achieve structural change. As aforementioned, many interventions targeting substance use rely on making changes to regulations of access; since sexual activity is not regulated in the same way, a unique range of community structural elements that may have an impact on youth HIV risks and rates needs to be identified and addressed.

Connect to Protect's Approach

C2P's approach draws upon both structural change and community mobilization theories to attempt to reduce HIV incidence and prevalence among urban youth at high risk for the disease. The project is comprised of three distinct phases, described in detail below. Phases I and II (the former completed and the latter nearing completion at the time this paper was written) were designed to allow sites to gather data needed for informed decision-making and to build collaborative partnerships with community agencies and members. The completion of Phases I and II prepare sites for Phase III, the community mobilization intervention. The intervention addresses gaps in the research literature with its “bottom-up” approach, whereby the community takes part in both identifying and trying to achieve intermediate-level structural changes that may reduce HIV acquisition and transmission among youth.

Phase I: Mapping and Community Outreach

The objectives of Phase I included each site: (1) generating a youth HIV/AIDS epidemiological profile for the urban area in which the site is located; (2) using the profiles to select within the city (a) geographic areas of high risk that are appropriate for C2P efforts and (b) a population on which to focus, such as YMSM, young women who have sex with older men, or youth IV drug users; and (3) creating partnerships with community-based organizations and agencies that can or may be able to reach the population of focus and are located within or serve the identified high-risk areas.

The first and second objectives were achieved by having each site gather existing morbidity (e.g., STI/HIV), behavioral (e.g., crime, delinquency), and demographic (e.g., income) data for 12 to 24 year olds, or as close to this age range as possible, by age, gender and race/ethnicity. The data were then sorted and “mapped” onto city and/or county maps using a geographic information systems (GIS) software program. Each site created approximately 25 maps that collectively provided a detailed snapshot of their city's area(s) and youth population(s) of highest HIV risk. For the third objective, sites invested a significant amount of time meeting with community representatives, hosting and attending events to create awareness of C2P, finding ways to incorporate youth input into the project in meaningful ways (e.g., involving them in informational materials development), and identifying organizations and agencies that were appropriate to formally invite as partners.

The core of C2P's success is likely to be in each site's ability to connect with community representatives from key local entities in ways that result in effective collaborative relationships. To facilitate this, sites used C2P-specific interview instruments to engage a potential partner in one-on-one discussions about his or her organization's mission, activities, ability to reach high risk population(s) and geographic area(s), and general interest in C2P. Potential partners included those who had historical relationships with the site, as well as new individuals and agency representatives. Using methods outlined in the research protocol, sites synthesized data from the maps, interview responses, and other sources (e.g., site staff knowledge of their city's political and social climate) to identify and invite approximately 20 community partners to join C2P activities. The data were also used to determine a partner's anticipated level of involvement, that is, a “main,” “supporting,” or “advisory” role based on interest, expertise, and resources available, such as time to devote to C2P activities. A formal meeting hosted by the site and attended by community partners marked the conclusion of Phase I. The goals of the meeting were to initiate the collaborative process, share knowledge of the population and geographic areas of focus, and begin preparing for Phase II activities.

Phase II: Interviews with Youth, Venue Identification, and Partnership Activation and Assessment

Phase II advances the project at each site by: (1) defining in more detail the specific locations or venues (e.g., clubs, community centers, parks) within the city where the population of focus spends time; (2) describing HIV risk behaviors, social networks and HIV seroprevalence of youth recruited from the identified venues; (3) “activating” the partnerships established in Phase I; and (4) assessing the characteristics, quality, and outcomes of the partnerships.

A range of research methodologies is utilized to meet the first two objectives. First, HIV-infected youth from clinics in each urban area are interviewed to reveal possible venues where adolescents and young adults at high risk for acquiring the disease spend time and/or congregate (henceforth referred to as “congregation venues”). Second, additional data are gathered at the identified congregation venues via a street-based interview to determine whether members of the site's population of focus can be reached there. The street-based interview, in combination with an ecological assessment of the location's physical environment (i.e., observed businesses, professional services, shared community resources, and underground economies), point to limitations and/or facilitating factors in reaching the population of focus. These data are triangulated with community partner input to make the most informed decisions about final venue selection for further data collection. Once the venues have been selected, HIV serosurveys are administered there to individuals from the population of focus whose HIV status is unknown to site staff. The HIV serosurvey has two components: an anonymous structured interview using the Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Administered Interview (ACASI) technique and an anonymous HIV antibody assay. The interview is designed to assess the population's HIV risk behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex; alcohol and drug use) and social networking patterns (e.g., where and how individuals meet and socialize with their friends and sex partners). The purpose of the assay, the results of which are not yet available, is to estimate HIV seroprevalence across all sites.1

The partnerships established during Phase I are being activated in Phase II with a series of working meetings held approximately every two months. During these meetings, site staff and their community partners share information on congregation venues, how to reach the population of focus, and HIV prevention strategies. In order to assess the characteristics, quality, and outcomes of these relationships, another set of research and evaluation methodologies is being used. This involves C2P's central administrative entity, referred to as the “National Coordinating Center” (described in detail later), periodically administering questionnaires and in-depth interviews to site staff and community partners and then providing feedback to sites based on the collected data. The feedback is aimed at building the strength of the partnerships, improving organizational structure and functioning, and summarizing the stated benefits and challenges of working together.

Phase III: Community Mobilization Intervention

The final phase of the project is the community mobilization intervention. To effectively meet Phase III goals and to gain wider acceptance of the project, a vital step is for the sites and their community partners to actively recruit and involve members of the broader community to take part in C2P activities. Representatives of various community sectors such as family, youth, government, schools, business, media, legal justice system, and more will be invited to participate, as deemed locally appropriate. It is expected that over time the diversity of sectors represented and the number of representatives sitting at the table will grow. Together, site staff, their community partners established during early phases, and newly invited community sector representatives will comprise a “C2P coalition” that will drive Phase III activities.

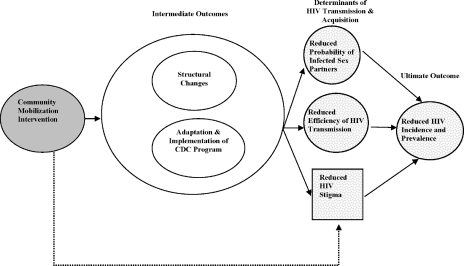

Figure 1 illustrates Phase III's framework. Adapted from several sources, it has as its underpinning the Anderson and May51–53 model for transmission dynamics of HIV infection. According to their model, an epidemic will persist if the reproductive number R0, defined as the average number of secondary infections generated by one infection, is greater than 1. R0 is, in part, a function of the probability that a susceptible person has sex with an infected person and the efficiency of transmission of HIV from an infected to an uninfected person during sex.54

Figure 1.

Phase III community mobilization intervention for reduced HIV incidence and prevalence.

On the left side of the model is the community mobilization intervention. For C2P, this is defined as the strategic planning process “VMOSA” that includes the coalition developing a vision, mission, objectives, strategies and, ultimately, an action plan.51,55–57 Before finalizing decisions on which structural changes to pursue, the coalition will gather input on the feasibility and importance of the proposed objectives from “outside” local health experts, that is, individuals not involved in C2P activities that are thought to have knowledge and insight of their city's youth and HIV situation.

The action plan will detail the selected structural change objectives, the proposed steps for achieving them, and anticipated barriers or facilitators. The execution of the action plan will be a dynamic process throughout Phase III and will involve ongoing review and revision as objectives are met and new ones are added. This ongoing process will allow the coalition to make critical decisions about structural change objectives that can strengthen local authority and incorporate local norms, standards, and priorities. Community involvement of this type is expected to promote greater acceptance of the structural change objectives, thus creating an environment for sustainability should they be achieved.

In the middle of the diagram are the intermediate outcomes. One is structural change. For C2P purposes, this is defined as new or modified programs, policies, or practices that are logically linkable to HIV acquisition and transmission and can be sustained over time, even when key persons responsible for making the change are no longer involved. Structures are the targets for change, whereas individuals may be directly or indirectly impacted. When setting structural change objectives, the discussion must include whether the effect of the change is likely to persist (i.e., risk is reduced) and if there is a supporting infrastructure in place—independent of the coalition or C2P-related resources—that increases the likelihood that the change will be maintained. Structural change achieved by the coalitions may include things such as: improved quality and availability of mental health and drug abuse treatment services; improved detection of HIV/STIs and referrals for services; improved (and new) social venues that support healthy lifestyles; new and expanded youth development programs; expanded VCT (voluntary counseling & testing); prevention case management; and youth-friendly HIV primary care programs. Given Phase III's bottom-up orientation, each urban community may have a distinct array of structural changes.

The second intermediate outcome is the adaptation and implementation of a relevant community-level program from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Compendium of HIV Prevention Interventions.58 These programs are aimed at changing the risk profiles of youth. The goal is to maintain fidelity to the selected program's core elements while adapting and delivering it to the community. The CDC program is included in the Phase III framework to facilitate community mobilization. Structural changes can take a significant amount of time to achieve, and community mobilization efforts can wane in the absence of short-term successes. The program activities address this by allowing for more immediate results, such as those related to condom usage, while working toward broader changes to the community's structural elements.

On the right side of the proposed model is the ultimate outcome, reduced HIV incidence and prevalence, as well as the determinants of HIV transmission and acquisition suggested by the Anderson and May model—reduced probability of infected sex partners and reduced efficiency of HIV transmission. A third, more “macro-level” determinant identified in the model is stigma. HIV/AIDS-related stigma is widely acknowledged as a barrier to public health efforts related to: HIV test-seeking and other preventive behaviors; care-seeking behavior upon diagnosis; quality of care provided to HIV-positive patients; disclosure of diagnoses to others; and the perceptions and treatment of persons living with HIV/AIDS by communities, families and partners.59–61

Data Analysis

Each C2P phase has a unique data analysis plan consistent with that phase's objectives. Information regarding Phases I and II will be only briefly described here and will be presented more fully in other papers, along with detailed results. This section's emphasis will be on plans for testing Phase III hypotheses.

For Phases I and II there are no formal hypotheses. In Phase I, data analysis chiefly involved interpreting the maps, HIV-positive youth interview data, and community partner input to make decisions such as which congregation venues to select for HIV serosurvey data collection. Thus, the overall analysis was qualitative in nature. For the Phase II, the calculations focus on the precision of estimation of the proportion of subjects, by gender and city, who are HIV-positive. Estimates of HIV prevalence will also be provided for all cities pooled, although that summary may refer to heterogeneous proportions that have no common value.

Given the features of Phase III, a quasi-experimental study design will be employed where it is expected that there will be naturally occurring variations in the “dose” of the intervention (i.e., the level of community mobilization across communities). The focus of the intervention is the community and the outcome of interest is change in the community over time. The principles of a clinical trial design are difficult to apply to a study of this nature because we are observing ecological factors across dynamic units of measurement (e.g., communities or cities) that cannot be rigorously controlled or randomized.

As part of Phase III, sites are re-collecting and re-examining the same type of surveillance data that were mapped during Phase I to look for changes in disease patterns in the geographic area of focus versus a comparison community. Site staff will also be documenting community mobilization activities such as steps taken toward structural change objectives and the number of objectives achieved over time. In addition, throughout Phase III some sites will continue to collect risk behavior data, such as that collected in Phase II, during the ACASI portion of the HIV serosurvey. In the final year of the study, these sites will also include the anonymous HIV antibody assay. This information, along with the analytic process used to test the study hypotheses (described below), will support the overall Phase III data analysis plan.

The theoretical framework (see Fig. 1) will guide the overall evaluation of the study. The hypotheses (H1–H3) refer to the relation of numbers of community actions and levels of community mobilization, both venue-level covariates, to venue- and community-level outcomes. Hierarchical models appropriate to such data are discussed by Skrondal and Rabe-Hesketh and Sullivan, Dukes, and Losina.62,63 The hypotheses will be assessed as follows: (1) the extent of community mobilization and broader community changes (H1); (2) the success of the adaptation and implementation of the selected CDC program (H2); and (3) the changes in public health surveillance indicators of HIV risk (H3). Specifically, the hypotheses state:

-

Increasing levels of community mobilization will be associated with increasing levels of structural change over 4 years, as measured by new or modified programs, policies, and practices, within and across intervention communities.

This hypothesis asserts that there is a relation between two ecological variables, each defined only at the level of a community. With 4 years of data, each community defines a time-series, with five observations (baseline plus later values). We will fit a simple regression model to the entire data set with a random effect for community.

-

Higher levels of community mobilization will be associated with successful adaptation and implementation of the selected CDC program over 4 years, as measured by high fidelity to the core elements of the program and delivery of the adapted intervention to the target community, respectively, across intervention communities.

This hypothesis is a paired time series, and the analysis for H1 is applicable.

Intervention communities will have a greater reduction in public health surveillance indicators of HIV risk, including number of new cases of HIV and other STIs, compared to non-intervention demographically similar communities within ATN cities at the end of the study.

This hypothesis refers to change over 4 years and is based on a test of the null hypothesis of no within-community change (using paired data). This is also an assertion that, holding one community-level covariate fixed (time over 4 years), there is no effect of another community-level covariate, intervention or not. This community-level analysis is informed by individual- and venue-level covariates.

It should also be noted that the project is not specifically designed to examine independent effects of structural change and the CDC program on HIV. This would require a classic 2-by-2 study design in which some communities had structural changes with the CDC program, some had the structural changes without the CDC program, some had the CDC program without structural changes, and some had neither. This is not feasible for reasons outlined above. However, communities might sort themselves into these four groups during the study and the measures of the level of structural change and of successful adaptation and implementation of the CDC program could be used to assess their independent effects post hoc.

Connect to Protect Study Infrastructure

A cornerstone to successfully initiating a multi-phase, multi-site community mobilization intervention such as C2P is the creation of strong study administrative infrastructures at both local and central levels.

Local Site Administrative Infrastructure

Sites are based at universities, hospitals, and medical centers and are both clinical providers and research units. While guided by a central administrative entity, described below, each site operates independently with its own staff. Although the staffing structure at each site is organized somewhat differently, all have a resident principal investigator to provide oversight and research direction, site coordinators to direct day-to-day operations, and outreach workers to facilitate and implement community-based research activities. The educational backgrounds, experiences, and areas of expertise of the site coordinators and outreach staff vary considerably across sites. This is seen as a source of strength; across sites, staff share ideas for and knowledge of C2P-related topics and experiences.

Central Administrative Infrastructure

A central administrative entity, the National Coordinating Center (NCC), has been established as a type of headquarters or “nerve center” that works closely with the sites and a data and operations center (Westat in Rockville, MD). Most NCC staff members are based at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD (the protocol chair's institutional home), or DePaul University in Chicago, IL (a co-investigator's institutional home). The NCC keeps track of protocol-related activities at each of the sites, provides direction and technical assistance, and fosters cross-site communication and collaboration. This is achieved by having ongoing communication with site staff via conference calls, an online message board, e-mail, training sessions, and ATN-sponsored semi-annual meetings. The dynamic and unpredictable nature of a community-based study and the distance between each site and the protocol chair/co-investigators are two aspects of this study that the NCC helps to mitigate.

The NCC's primary responsibility is to ensure that steps of the research protocol are consistently implemented across all sites. This means that the NCC facilitates the decision making process but does not make final decisions about local issues. For example, sites were tasked with making specific decisions throughout Phases I and II related to geographic areas of focus, populations of focus and venues to conduct research. While these types of decisions were ultimately made at the local level, each site discussed their data findings and decision-making steps with the NCC to ensure that (1) a uniform and analytical process was used by each site to arrive at decisions within a timeframe consistent with the protocol, and (2) the local decision reflected the intent of the protocol. Specifically, some sites found it difficult to narrow to one subpopulation of youth during Phase I and were inclined to identify several subpopulations of “high risk” youth. In these cases, the NCC talked them through the expectations of the protocol, reviewed local data and contextual factors with site staff, and helped them reach a decision that was appropriate for the local community and within the parameters of the protocol. The ultimate decision of which subpopulation to select was made locally, but the NCC guided sites in selecting only one subpopulation, as was consistent with protocol expectations.

In Phase III, the role of the NCC will shift from serving as a monitor of protocol expectations to serving as a reflective body that provides feedback about intervention activities. As a sounding board for the sites, the NCC will continue to refrain from local decision making but will provide recommendations to sites and their coalitions so that they are better equipped to make progress toward their goals.

Ongoing and Accessible Technical Assistance: Training and Materials

The NCC coordinates and delivers trainings (e.g., using GIS software, strategic planning, cultural competency) to sites throughout the various phases of the protocol. This ensures that all sites have the basic knowledge and skills necessary to carry out a protocol task, in addition to contributing to the consistency by which protocol steps are implemented across sites. The trainings are developed by NCC staff members alone or in conjunction with individuals such as outside consultants and site staff who have particular areas of expertise.

The NCC also provides sites with ready-made materials, such as C2P informational brochures and slide presentations. This increases the likelihood that uniform messages about the study are being shared with the community. While consistency is important, it is also recognized that there is much value to encouraging sites to tailor NCC-created pieces to best meet and speak to their particular community needs. As such, sites localize parts of the materials—such as inserting local maps and data into prepared presentations—while maintaining the core message of the study as described by the NCC. Sites also have the option to develop their own community materials, such as fact sheets or flyers, to complement or enhance those provided by the NCC.

“Real Time” Feedback Mechanisms

A crucial aspect of NCC feedback to sites focuses on the collaborative relationships. The NCC has several mechanisms in place to inform sites of their progress in this area and to allow them to make adjustments as necessary. One mechanism includes process evaluation measures administered to site staff and other coalition members that assess the quality and functioning of the relationships (e.g., how well members communicate) at various points. After each round of data collection, the NCC summarizes findings and shares them with the sites. Areas of strength and opportunities for improvement are highlighted, so that a coalition can celebrate their successes as well as work on challenging areas.

A second mechanism is the ongoing, systematic input sites receive from the NCC on the strategic planning process, action plan execution, and CDC program adaptation and delivery. Sites share this information with their coalitions throughout Phase III so that they can work together to further their mobilization efforts and/or receive additional technical assistance and training as needed.

Evaluation of the Administrative Infrastructures

Independent of the NCC and sites, a Quality Assurance Team (QAT) has been established to conduct an ongoing process evaluation of the organizational structure and functioning of the overall C2P project. The internal process evaluation system created by the QAT members includes collecting information from all members of the C2P project-site staff, community participants, and NCC staff—via multiple methods (e.g., surveys, interviews)—and then providing feedback to both sites and the NCC. Because this evaluation involves ongoing monitoring and is focused on improving the internal structure and functioning of the overall C2P project, the QAT provides findings to the NCC and protocol chair on a continual basis so that potential problems can be addressed more immediately. This feedback loop has helped to keep the C2P structure responsive to the evolution and growth of the project. This ongoing evaluation not only enhances the work carried out by the NCC and site staff, but can also be used to inform other researchers and community members interested in carrying out similar projects.

Discussion and Conclusion

The research literature increasingly reflects the understanding that for health-related interventions to be successful, a paradigm shift must occur to include structural level change instead of merely attempting to change the individual.64 C2P is attempting to achieve structural change in multiple urban areas through community mobilization activities. Initiating a project of this magnitude not only requires a framework with strong theoretical grounding in community mobilization and related concepts, but also entails: (1) building a central administrative infrastructure that facilitates the process across sites and (2) supporting and encouraging local site and community expertise and collaboration.

Central Administrative Infrastructure

The central administrative infrastructure promotes consistency across sites by aiding them in adhering to the research protocol and avoiding usual implementation pitfalls. NCC trainings and feedback help to build the capacity of and “level the playing field” across sites, especially given the varied experiences and skills of site staff and city-specific challenges encountered. The NCC also facilitates cross-fertilization among sites so that staff can share ideas and successful strategies with one another.

A noteworthy and somewhat unexpected lesson learned by the NCC is that in the same way sites are encouraged to promote trust, buy-in, and ownership of the project in their communities and with their coalition members, the NCC staff has to encourage these elements among its “community” of staff from the sites. The NCC does this on recommendation of the QAT by spending a significant amount of time building and maintaining trusting relationships with site staff and by providing support and technical assistance as promised. This is essential in order for the NCC to guide sites through difficult decision-making processes and to offer recommendations that are openly received and considered.

Local Site and Community Expertise

Local site and community expertise is the essence of C2P. The project's three phases allows for sites and members of the community to incrementally get to know each other's strengths, to integrate C2P into any pre-existing collaborations as appropriate, and to best understand community risks, needs, and priorities. While each phase engages the community to some degree, the most active involvement will occur during Phase III. Throughout the project, sites also attempt to “give back” to the community in meaningful ways (e.g., providing community partners with data that might lead to funding opportunities for their organizations). By directly involving the community in critical decision-making and giving back, common concerns about research—such as researchers “getting what they want” from communities and then leaving—are being alleviated.

While local site and community expertise is a tremendous strength of this project, it is also associated with some of the main challenges of this study. It is important to have continuity throughout the three phases, yet because the study spans 6 years, it is expected that there will be site staff turnover and changes in partnerships over the course of the project. A second challenge is that, given the varied experience and skill set of site staff and community partners, different levels of technical assistance have been and will continue to be needed to ensure comparable functioning across sites.

In conclusion, a community mobilization intervention that focuses on achieving structural change has the potential to curb, for the long term, the spread of HIV even among the most vulnerable youth populations in urban high-risk areas. Compared to other approaches that have been used over the last two decades, this type of project is in its infancy. To optimize C2P's opportunity for success, time and resources are first being put into laying a strong foundation at both the local and central levels. It is through this process that a prevention infrastructure can be built—one that yields the levels of community involvement, ownership, capacity, and trust that are needed to carry out often time-intensive, sometimes complex attempts to change the very structures that can hinder or facilitate HIV prevention among youth.

Acknowledgements

The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) and Connect to Protect are funded by grant No. U01 HD40506-01 from the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Audrey Smith Rogers, PhD; MPH; Robert Nugent, PhD; Leslie Serchuck, MD), with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (Nicolette Borek, PhD), Mental Health (Andrew Forsyth, PhD; Pim Brouwers, PhD), and Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Kendall Bryant, PhD). Connect to Protect has been scientifically reviewed by the ATN's Behavioral and Community Prevention Leadership Groups. The authors would like to acknowledge Connect to Protect's National Coordinating Center staff members and consultants: Audrey Bangi, PhD; Matthew Bowdy, MA; Shayna Cunningham, MHS; Mimi Doll, PhD; Jason Johnson, BA; Rachel Lynch, MPH; Suzanne Maman, PhD; Danish Meherally, BS; Grisel Robles-Schrader, BA; Marizaida Sánchez-Cesáreo, PhD; Nancy Willard, BA; and Stephanie Witt, MPH. The authors also acknowledge support of: DePaul University's Quality Assurance Team member Leah Neubauer, BA; individuals from the ATN Data and Operations Center (Westat, Inc.) including Jim Korelitz, PhD; Barbara Driver, RN, MS; Lori Perez, PhD; Rick Mitchell, MS; Stephanie Sierkierka, BA; and Dina Monte, BSN; and individuals from the ATN Coordinating Center at the University of Alabama including Craig Wilson, MD; Cindy Partlow, MEd; Marcia Berck, BA; and Pam Gore. The following ATN sites have participated in the study: University of South Florida: Patricia Emmanuel, MD; Diane Straub, MD; Shannon Cho, BS; Georgette King, MPA; Mellita Mills Kendrick, BS; and Chodaesessie Morgan, MPH. Childrens Hospital of Los Angeles: Marvin Belzer, MD; Miguel Martinez, MSW/MPH; Veronica Montenegro, Ana Quiran, Angele Santiago, Gabriela Segura, BA; and George Weiss, BA. Children's Hospital National Medical Center: Lawrence D'Angelo, MD; William Barnes, PhD; Bendu Cooper, MPH; and Cassandra McFerson, BA. The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: Brett Rudy, MD; Antonio Cardoso, ABD; and Marne Castillo, MEd. John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital and the CORE Center: Lisa Henry-Reid, MD; Jaime Martinez, MD; Zephyr Beason, MSW; and Draco Forte, MEd. University of Puerto Rico: Irma Febo, MD; Ileana Blasini, MD; Ibrahim Ramos-Pomales, MPHE; and Carmen Rivera-Torres, MPH. Montefiore Medical Center: Donna Futterman, MD; Sharon S. Kim, MPH; Lissette Marrero, Stephen Stafford, and Carol Tobkes, MPH. Mount Sinai Medical Center: Linda Levin, MD; Meg Jones, MPH; Christopher Moore, MPH and Kelly Sykes, PhD University of California at San Francisco: Barbara Moscicki, MD; Coco Auerswald, MD; Catherine Geanuracos, MSW; Kevin Sniecinski, BS. Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Sue Ellen Abdalian, MD; Lisa Doyle, Trimika Fernandez, MS; and Sybil Schroeder, PhD University of Maryland: Ligia Peralta, MD; Bethany Griffin Deeds, PhD; Sandra Hipszer, MPH; Maria Metcalf, MPH; and Kalima Young, BA. University of Miami School of Medicine: Lawrence Friedman, MD; Angie Lee; Kenia Sanchez, MSW; Benjamin Quiles, BSW; and Shirleta Reid. Children's Diagnostic and Treatment Center: Ana Puga, MD; Dianne Batchelder, RN; Jamie Blood, MSW; Pam Ford, MS;and Jessica Roy, MSW. Children's Hospital Boston: Cathryn Samples, MD; Wanda Allen, BA; Khari Farrell, PhD; Lisa Heughan, BA; Meqdes Mesfin, MPH; and Judith Palmer-Castor, PhD University of California at San Diego: Stephen Spector, MD; Rolando Viani, MD; Stephanie Lehman, PhD; and Mauricio Perez. We would also like to acknowledge staff members who provided data from local public health departments, police departments, state agencies, and other institutions. Finally, we recognize the thoughtful input given by participants of our national and local Youth Community Advisory Boards.

Footnotes

Given the public health urgency of knowing one's HIV status, all sites have also made arrangements with local entities to offer serosurvey participants confidential HIV testing and counseling.

Ziff, Chutuape, and Ellen are with the Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; Harper is with the Department of Psychology, DePaul University, Chicago, IL, USA; Deeds is with the Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland Medical School, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; Futterman is with the Albert Einsten College of Medicine and Children's Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY, USA; Francisco is with the Department of Public Health Education, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, USA; Muenz is with the Westat, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA.

References

- 1.Rosenberg PS, Goedert JJ, Biggar RJ. Effect of age at seroconversion on the natural AIDS incubation distribution. Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study and the International Registry of Seroconverters. AIDS. 1994;8(6):803–810. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.UNAIDS. 2004 report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic: 4th global report. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/bangkok2004/GAR2004_html/GAR2004_00_en.htm. Accessed January 10, 2006.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2005;16:1–46.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2003. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2004;15:1–40.

- 5.Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E. Sexual risk as an outcome of social oppression: data from a probability sample of Latino gay men in three U.S. cities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. Aug 2004;10(3):255–267. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Garofalo R, Harper GW. Not all adolescents are the same: addressing the unique needs of gay and bisexual male youth. Adolesc Med: State of the Art Reviews. 2003;14(3):595–611. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gomez CA, Marin BV. Gender, culture, and power: barriers to HIV-prevention strategies for women. J Sex Res. 1996;33(4):355–362.

- 8.Harper GW. Contextual factors that perpetuate statutory rape: the influence of gender roles, sexual socialization, and sociocultural factors. DePaul Law Rev. 1996;50(3):897–918.

- 9.Harper GW, Schneider M. Oppression and discrimination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people and communities: a challenge for community psychology. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;31(3–4):243–252. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV incidence among young men who have sex with men—seven U.S. cities, 1994–2000. MMWR. 2001;50:440–444. [PubMed]

- 11.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;284(2):198–204. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Harawa NT, Greenland S, Bingham TA, Johnson DF, Cochran SD, Cunningham WE, Celentano DD, Koblin BA, LaLota M, et al. Associations of race/ethnicity with HIV prevalence and HIV-related behaviors among young men who have sex with men in 7 urban centers in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):526–536. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Celentano DD, Sifakis F, Hylton J, Torian LV, Guillin V, Koblin BA. Race/ethnic differences in HIV prevalence and risks among adolescent and young adult men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82(4):610–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kim N, Stanton B, Li X, Dickersin K, Galbraith J. Effectiveness of the 40 adolescent AIDS-risk reduction interventions: a quantitative review. J Adolesc Health. 1997; 20(3):204–215. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jemmott JB III, Jemmott LS. HIV behavioral interventions for adolescents in community settings. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente RJ, eds. Handbook of HIV Prevention. AIDS Prevention and Mental Health. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer; 2000:103–127.

- 16.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(4):381–388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(1):94–105. [PubMed]

- 18.Robin L, Dittus P, Whitaker D, et al. Behavioral interventions to reduce incidence of HIV, STD, and pregnancy among adolescents: a decade in review. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(1):3–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Altman D. Power and community: organizational and cultural responses to AIDS. In Book Series, Social Aspects of AIDS. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Taylor & Francis; 1994.

- 20.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S112–S115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Parker RG. Empowerment, community mobilization and social change in the face of HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 1996;10:S27–S31. [PubMed]

- 22.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, Kalichman SC. Psychological interventions to prevent HIV infection are urgently needed: new priorities for behavioral research in the second decade of AIDS. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Rotheram-Borus, MJ. Expanding the range of interventions to reduce HIV among adolescents. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S33–S40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sumartojo E, Doll L, Holtgrave D, Gayle H, Herson M. Enriching the mix: incorporating structural factors into HIV prevention. AIDS. 2000;14(suppl 1):S1–S2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Harper G, Contreras R, Bangi A, Pedraza A. Collaborative process evaluation: enhancing community relevance and cultural appropriateness in HIV prevention. J Prev Interv Community. 2003;26(2):53–71. [DOI]

- 26.O'Reilly KR, Piot P. International perspectives on individual and community approaches to the prevention of sexually transmitted disease and human immunodefiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(suppl 2):S214–S222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Blankenship KM, Bray SJ, Merson MH. Structural interventions in public health. AIDS. 2000;14(1):S11–S21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S22–S32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S3–S10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Deaton A. Policy implications of the gradient of health and wealth. An economist asks, would redistributing income improve population health? Health Aff. 2002;21(2):13–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Lurie N. What the federal government can do about the nonmedical determinants of health. Health Aff. 2002;21(2):94–106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Wallace R. Urban desertification, public health and public order: ‘planned shrinkage,’ violent death, substance abuse and AIDS in the Bronx. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(7):801–813. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Sweat MD, Denison JA. Reducing HIV incidence in developing countries with structural and environmental interventions. AIDS. 1995;9(suppl A):S251–S257. [PubMed]

- 34.Cohen DA, Scribner R. An STD/HIV prevention intervention framework. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2000;14(1):37–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Community Tool Box. Criteria for Choosing Promising Practices and Community Iinterventions. Available at: http://ctb.ku.edu/tools/en/sub_section_main_1152.htm. Accessed June 14, 2005.

- 36.Burris S, Blankenship KM, Donoghoe M, et al. Addressing the “risk environment” for injection drug users: the mysterious case of the missing cop. Milbank Q. 2004;82(1):125–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Treno AJ, Holder HD. Community mobilization, organization, and media advocacy: a discussion of methodological issues. Eval Rev. 1997;21(2):166–190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Minkler M. Improving health through community organization. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass; 1990:257–287.

- 39.Babalola S, Sakolsky N, Vondrasek C, Mounlom, D, Brown, J, Tchupo J. The impact of a community mobilization project on health-related knowledge and practices in Cameroon. J Commun Health. 2001;26(6):459–477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Cheadle A, Wagner E, Anderman C, et al. Measuring community mobilization in the Seattle minority youth health project. Eval Rev. 1998;22(6):699–716. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Harachi TW, Ayers CD, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Empowering communities to prevent adolescent substance abuse: process evaluation results from a risk- and protection-focused community mobilization effort. J Prim Prev. 1996;16(3):233–254. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Johnson K, Bryant D, Strader T, Bucholtz G. Reducing alcohol and other drug use by strengthening community, family, and youth resiliency: an evaluation of the creating lasting connections program. J Adolesc Res. 1996;11(1):36–67. [DOI]

- 43.Kirsch HW. Taking the message to the streets: Graffiti campaigns and community mobilization. In: Kirsch HW, ed. Drug Lessons & Education Programs in Developing Countries. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction; 1995:263–270.

- 44.Kirsch HW, Andrade SJ, Osterling J, Sherwood-Fabre L. Empowerment, participation, and prevention: use of the community promoter model in Northern Mexico. In: Kirsch HW, ed. Drug Lessons & Education Programs in Developing Countries. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction; 1995:179–194.

- 45.Manger TH, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Mobilizing communities to reduce risks for drug abuse: lessons on using research to guide prevention practice. J Prim Prev. 1992;13(1):3–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Strader TN, Collins DA, Noe TD. Building Healthy Individuals, Families, and Communities: Creating Lasting Connections. Council on Prevention & Education: Substances, Inc. Louisville, Kentucky; 2000.

- 47.Rogers T, Feighery EC, Tencati EM, Butler JL, Weiner L. Community mobilization to reduce point-of-purchase advertising of tobacco products. Health Educ Q. 1995; 22(4):427–442. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Snell-Johns J, Imm P, Wandersman A, Claypoole J. Roles assumed by a community coalition when creating environmental and policy-level changes. J Commun Psychol. 2003;31(6):661–670. [DOI]

- 49.Ellis GA, Reed DF, Scheider H. Mobilizing a low-income African American community tobacco control: a force field analysis. Health Educ Q. 1995;22(4):443–457. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Holder HD. Community prevention of alcohol problems. Addict Behav. 2000; 25(6):843–859. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Hyra D, et al. Building healthy communities. In: Tarlov A, St. Peter R, eds. The Society and Population Health Reader: A State and Community Perspective. New York: New Press; 2000:75–93.

- 52.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington, District of Columbia: National Academies; 2003.

- 54.Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. England: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1991.

- 55.Community Tool Box. An Overview of Strategic Planning or “VMOSA” (Vision, Mission, Objectives, Strategies, and Action Plans). Part D, Chapter 8, Section 1: Available at: http://ctb.ku.edu/. Accessed June 14, 2005.

- 56.Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Paine-Andrews A, Schultz JA. Working together for healthier communities: a research-based memorandum of collaboration. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Francisco VT, Fawcett SB, Schultz, JS, Paine-Andrews A. A model of health promotion and community development. In: Balcazar FB, Montero M, Newbrough JR, eds. Health Promotion in the Americas: Theory and Practice. Washington, District of Columbia: Pan American Health Organization; 2000:17–34.

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project. Compendium of HIV Prevention Interventions with Evidence of Effectiveness. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; November 1999 [revised].

- 59.Brown L, Macintyre K, Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:49–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Klein SJ, Karchner WD, O'Connell DA. Interventions to prevent HIV-related stigma and discrimination: findings and recommendations for public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2002;8:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S. Generalized Latent Variable Modelings: Multilevel, Longitudinal, and Structural Equation Models. Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004.

- 63.Sullivan LM, Dukes KA, Losina E. Tutorial in biostatistics. An introduction to hierarchical linear modeling. Stat Med. Apr 15 1999;18(7):855–888. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Leviton LC, Snell E, McGinnis M. Urban issues in health promotion strategies. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):863–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]